Abstract

Purpose

Hemophilia A (HA) is the most common X-linked inherited bleeding disorder. In some patients with HA, particularly those with severe HA, replacement therapy results in the production of high-responding clotting factor VIII inhibitors. The economic burden of this complication is the highest reported for a chronic disease. Our aim was to investigate the direct medical expenditure burden of high-responding inhibitors in patients with HA.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study was conducted using the National Health Insurance Research Database, utilizing data covering the period of 2004-2007.

Results

In total, 638 males with HA, including 37 patients with high-responding inhibitors were evaluated. Over 99% of the annual median medical expenditure was attributable to the cost of clotting factor concentrates (CFCs) in patients with high-responding inhibitors. The annual median expenditure related to CFCs of the total medical care and outpatient care were US$170611 and US$141982, respectively, and were 4.6- and 4.3-fold higher in these patients during the study period, respectively. In patients with high-responding inhibitors, the median hospitalization expenditure and daily hospitalization cost with or without surgical procedures were 3.0- and 2.4-fold higher, respectively, and 4.3 and 5.6-fold higher, respectively.

Conclusion

Our data reveal higher medical expenditures burden for patients with HA and high-responding inhibitors in Taiwan. Future research is encouraged to evaluate the impact of this burden on patient quality of life.

Keywords: Hemophilia, high-responding inhibitor, clotting factor concentrate, cost, Taiwan

INTRODUCTION

Hemophilia A (HA) is an X-linked inherited bleeding disorder caused by the functional absence or reduced levels of clotting factor VIII (FVIII). The disease is classified as mild, moderate, or severe, based on the degree of deficiency of the coagulation factor.1 The introduction of replacement therapy due to the availability of exogenous FVIII concentrates has substantially reduced bleeding episodes, prevented musculoskeletal damage, and improved orthopedic outcomes and quality of life in patients with hemophilia.2 Following the recommended prophylactic treatment, home therapy, and comprehensive care enables patients with HA to enjoy a better general state of health and engage in daily activities, social events, work, and education.3-5 However, in some patients with HA, therapeutically administered exogenous FVIII concentrates are recognized as foreign particulates, resulting in the production of antibodies (inhibitors) that neutralize the activity of FVIII and reduce or eliminate the efficacy of factor replacement therapy. Inhibitors are produced in 20-30% of patients with severe HA, but they may also arise in patients with mild/moderate HA and at any time in the patient's life.6,7 Patients with high-titer inhibitory antibodies can develop serious bleeding complications, resulting in greater rates of disability and risks of complications, and in these patients, so-called bypassing agents, such as recombinant FVIIa (rFVIIa) and activated prothrombin complex concentrates (aPCCs), are needed to achieve hemostasis.8 The economic consequences of treating hemophilia are mainly related to the direct medical costs of replacement clotting factor concentrates (CFCs), and economic burden of inhibitor complication in patients with hemophilia is one of the highest reported for a chronic disease.9-12

In March 1995, Taiwan launched a mandatory National Health Insurance (NHI) program that integrated three existing health insurance programs: labor, government employee, and farmer's insurance. By the end of 2004, approximately 99% of the population was covered, and nearly 23 million beneficiaries are currently enrolled in the NHI.13 The NHI is a single-payer compulsory social health insurance program organized by the government and operated by the Bureau of National Health Insurance (BNHI). The system is primarily funded by premiums paid collectively by the insured, employers, and central and local governments. The NHI program allows patients the freedom of choice when seeking medical care and uses cost-sharing strategies to reduce the potential demand for unnecessary services. In the initial stage, fee-for-service was widespread for both public and private providers. Facing spiraling growth of medical costs and demands to keep healthcare costs under control without a decline in the quality of care, the payment system for the NHI changed from fee-for-service to a global budget in 2002. To better manage the medical expenditures and enhance the professional autonomy of medical providers, other payment methods have been introduced in recent years, such as pay-for-performance, diagnosis-related groups, and a resource-based relative value scale system.14

Prior to implementation of the NHI program, individuals with hemophilia received only fewer amount clotting factors to relieve disease progression. Hemophilia has been classified as a catastrophic illness by the NHI since the program was implemented, exempting patients from a co-payment and assuring that patients are able to obtain sufficient CFCs for suitable replacement therapy. Thereafter, the BNHI implemented a global budget, and an independent budget (including hemophilia) has been allocated for rare diseases since 2004. However, no studies have been published regarding the economic burden of patients with high-responding inhibitors in Taiwan.

The aim of this research was to investigate the direct medical expenditure for patients with HA patients and high-responding inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Since implementing the NHI, the BNHI has cooperated with the National Health Research Institute, a non-profit research organization founded and sponsored by the Department of Health, to establish National Health Insurance Research Databases (NHIRDs). The present retrospective study was conducted by using the NHIRDs between January 2004 and December 2007. The databases include registry for catastrophic illness patient files, registry for drug prescriptions and claim data, ambulatory care expenditure data by visit, inpatient expenditure data by admission, and details of ambulatory care and inpatient orders.

Subjects' inclusion

The patients included in this study were identified from the 2004-2007 registry for catastrophic illness patient files in the NHIRDs. Subjects treated only with clotting factors, aPCC (FEIBA®, Baxter AG, Vienna, Austria), or activated rFVII (NovoSeven®, Novo Nordisk A/S, DK-2820 Gentofte, Denmark) were included.

The amount of a specific inhibitor to FVIII in each patient's blood was measured in Bethesda Units (BU) and referred to as "high titer" (more than 5 BU) or "low titer" (less than 5 BU). In patients with transient or low-responding inhibitors or low actual inhibitor titers (<5 BU mL-1) and who have weaker inhibitor responses to factor concentrates, bleeding episodes are commonly managed by increasing the dosages of FVIII concentrates. Patients with high-responding inhibitors were defined as those with an inhibitor level exceeding 5 BU at least once, in whom repeated exposure to factor concentrate will quickly trigger the formation of new inhibitors based on memory from a previous anamnestic response,8 and who underwent an inhibitor assay and used bypassing agents for a therapeutic interval exceeding 6 months in the relevant year.

Medical utilization and expenditure

Claims data were utilized to determine the expenditures for the following services: utilization of CFCs (including bypassing agents), other medications, laboratory services, radiological testing, rehabilitation services, hospitalizations, procedure, and outpatient care and inpatient care services.

Disease-related admission identification and inclusion utilized primary the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes, which primarily included factor VIII disorders, hemarthrosis, cerebral or gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hematuria, osteoarthritis, arthropathy, synovitis, fracture, infection or complication of orthopedic devices, and human immunodeficiency virus infection. The disease-related hospitalization complication analyses were classified as with or without surgical procedures. The complications with surgical procedures primarily included joint replacement, synovectomy, insertion of a totally implantable vascular access device, incision with the removal of a foreign body from the skin and subcutaneous tissue, tooth extraction, and other procedures. The costs were calculated using a 3% discount rate and adjusted by using the Taiwan Consumer Price Index of medicines and medical care category and expressed in 2007 US dollars.15,16

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test was used to compare categorical data. To exclude the outliers, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to identify significant median differences among groups. p-values <0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA® software version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, Lakeway, TX, USA).17

RESULTS

Study subjects

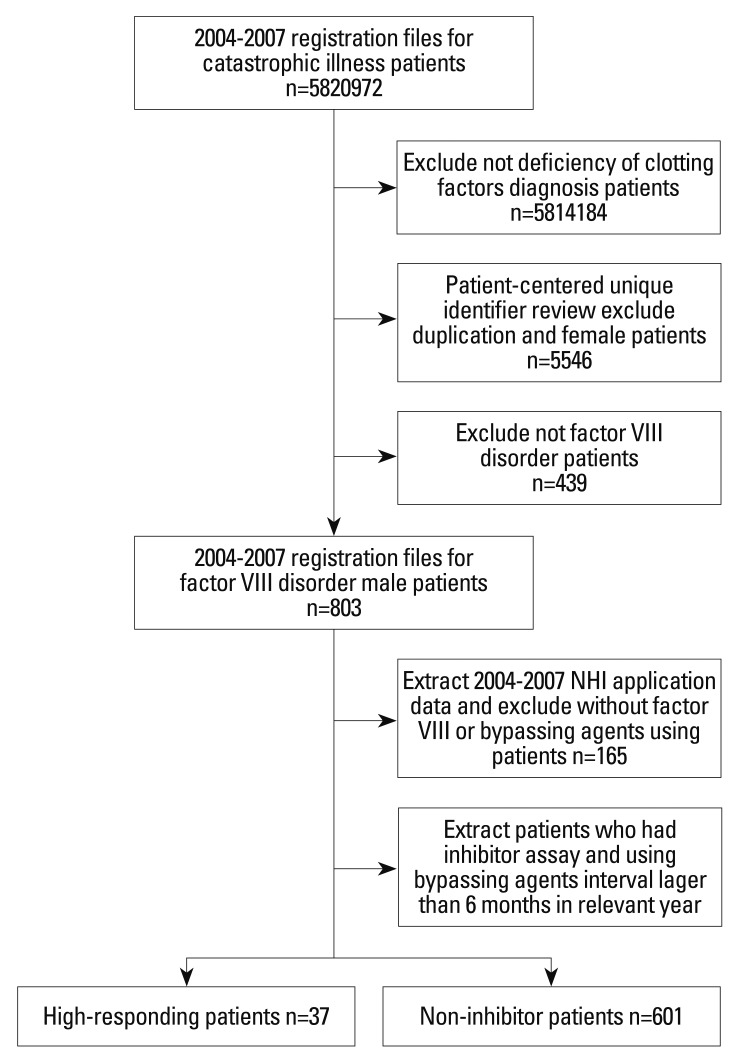

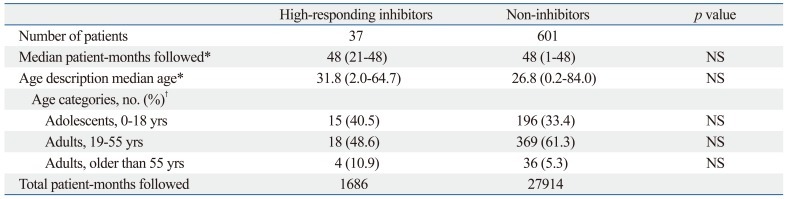

Fig. 1 presents the flow chart for enrolling the subjects. In total, 638 males with HA, including 37 patients with high-responding inhibitors, were enrolled in the study. The median ages of patients with and without high-responding inhibitors were 31.8 and 26.7 years, respectively, and the median patient-months followed for the same groups were 48 and 48 years, respectively (Table 1). The differences in median age and other age categories were not statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for subject inclusion. NHI, National Health Insurance.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics According to Inhibitor Status

NS, not significant.

*Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

†Chi-square test.

Medical utilization and expenditure

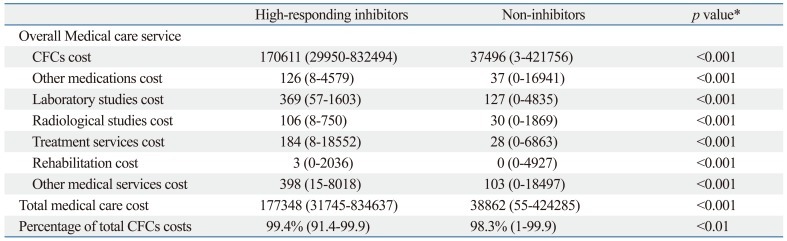

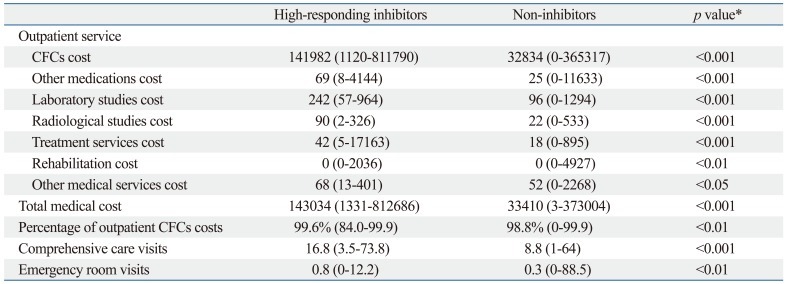

The annual median medical resource utilization is presented in Table 2. The overall annual median expenditure of total medical care and CFCs cost in patients with high-responding inhibitors were US$177348 and US$170611, respectively. Table 3 shows the annual median outpatient medical resource utilization, and expenditure of the total medical care and CFCs cost in patients with high-responding inhibitors were US$143034 and US$141982, respectively. Costs related to CFCs accounted for over 98% of the median total and outpatient medical expenditures, especially among patients with high-responding inhibitors. The annual median total CFCs cost and outpatient CFCs cost were 4.6- (US$170611 vs. US$37496, p<0.001) and 4.3-fold (US$141982 vs. US$32834, p<0.001) higher for patients with high-responding inhibitors, respectively. Besides, the annual median comprehensive care visits and emergency room visits were 1.9- and 2.7-fold higher among patients with high-responding inhibitors.

Table 2.

Annual Median Medical Resource Utilization According to Inhibitor Status during the Study Period (2007 US Dollars)†

CFCs, clotting factor concentrates.

*Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

†The US$ : NT$ exchange rate was 1 : 32.84.

Table 3.

Annual Median Outpatient Medical Resource Utilization According to Inhibitor Status during the Study Period (2007 US Dollars)†

CFCs, clotting factor concentrates.

*Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

†The US$ : NT$ exchange rate was 1 : 32.84.

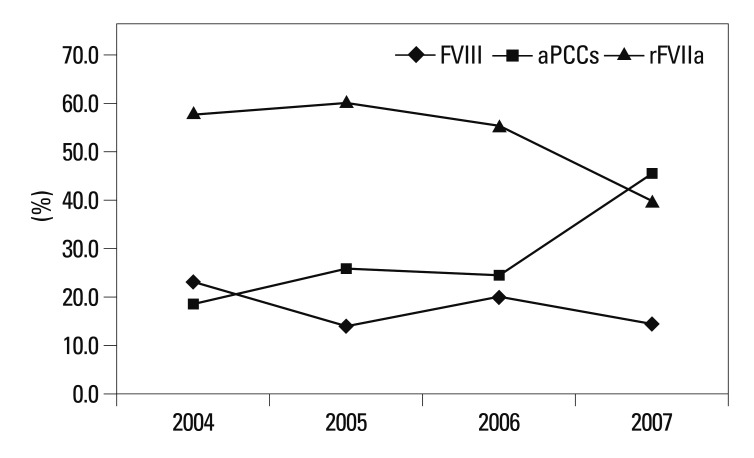

The all patients with high-responding inhibitors (n=37) accounted for NHI's annual CFCs expenditure were 20.2%, 16.5%, and 3.7% of the overall care, outpatient care, and inpatient care, respectively. Fig. 2 shows the annual proportion of CFCs costs in all patients with high-responding inhibitors. The bypassing agents increased over time from 76.6% in 2004 to 85.2% in 2007, and year-to-year variation was evident. Moreover, the proportion of expenditures related to rFVII tended to decrease, whereas those related to aPCCs tended to increase.

Fig. 2.

Annual proportion of clotting factor concentrates costs in all patients with high-responding inhibitors during the study period. FVIII, factor VIII; rFVIIa, recombinant FVIIa; aPCCs, activated prothrombin complex concentrates.

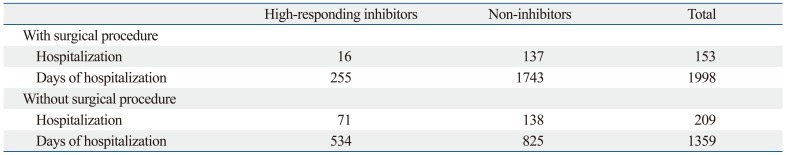

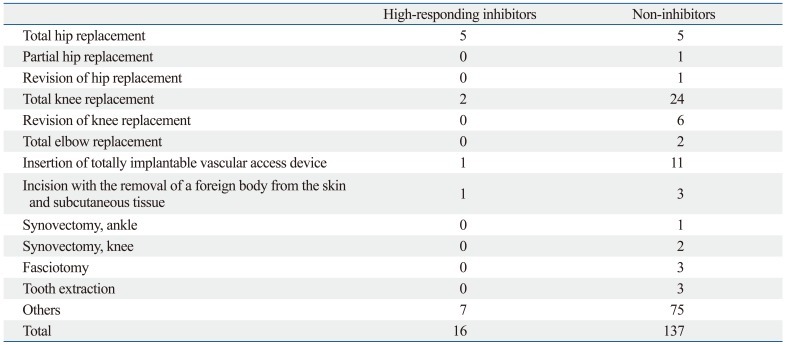

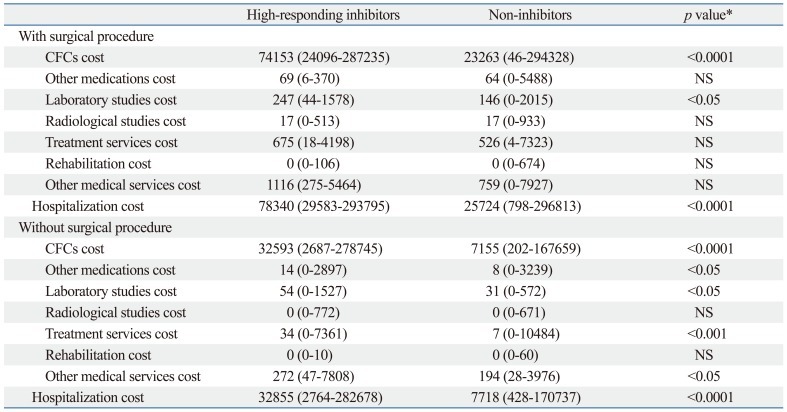

Table 4 shows the disease-related complications of hospitalization. Approximately 49.8% of hospitalizations were related to surgical procedures in patients without high-responding inhibitors. Conversely, only 18.4% of hospitalizations were related to surgical procedures in patients with high-responding inhibitors. The incidences of orthopedic replacement and revision were 4.2 and 1.4 per 1000 person-months, respectively (Table 5).

Table 4.

Hospitalization with Disease-Related Complications According to Inhibitor Status during the Study Period

Table 5.

Hospitalization with Surgical Procedures According to Inhibitor Status during the Study Period

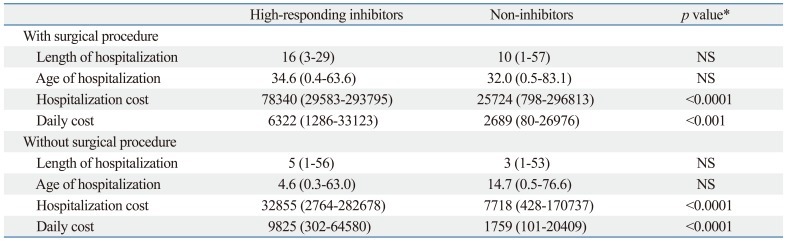

The hospitalization comparison due to disease-related complications is presented in Table 6. The median hospitalization expenditure and daily hospitalization cost among patients who underwent surgical procedures were 3.0- (US$78340 vs. US$25724, p<0.0001) and 2.4-fold (US$6322 vs. US$2689, p<0.0001) higher for patients with high-responding inhibitors, respectively. Similarly, among patients who did not undergo surgical procedures, the median hospitalization expenditure and daily hospitalization cost were 4.3- (US$32855 vs. US$7718, p<0.0001) and 5.6-fold (US$9825 vs. US$1759, p<0.0001) higher for patients with high-responding inhibitors, respectively. Table 7 shows the hospitalization resource utilization. The median percentage of hospitalization expenditure related to CFCs cost among patients who did or did not undergo surgical procedures were 95% vs. 90% and 99% vs. 93%, respectively, and higher for patients with high-responding inhibitors.

Table 6.

Median Hospitalization Comparison in Patients with Disease-Related Complications during the Study Period (2007 US Dollars)†

NS, not significant.

*Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

†The US$ : NT$ exchange rate was 1 : 32.84.

Table 7.

Median Hospitalization Resource Utilization in Patients with Disease-Related Complications during the Study Period (2007 US Dollars)†

CFCs, clotting factor concentrates; NS, not significant.

*Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

†The US$ : NT$ exchange rate was 1 : 32.84.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to assess the financial burden of patients with HA and high-responding inhibitors in Taiwan. The results revealed an apparently higher medical resources burden for the care of these patients.

The annual total median cost related to CFCs was 4.6 times higher in patients with high-responding inhibitors, confirming the findings by Goudemand18 that costs related to factor replacement in patients with high-responding inhibitors were 3-fold higher than in those in patients without inhibitors after the entry of bypassing agents; previous studies reported lower values, but these studies also had relatively small sample sizes and issues regarding outliers (the mean/median issue).19-21 Our results also agreed with those reported by Gringeri, et al.,11 who reported that over 98% of direct healthcare expenditures in patients with high-responding inhibitors were attributable to costs related to CFCs.

Additionally, our results indicated that daily hospitalization costs depend primarily on the inhibitor status of the patient. The median daily hospitalization costs in patients who did or did not undergo surgical procedures were 2.4- and 5.6-fold higher, respectively, in patients with high-responding inhibitors. Gautier, et al.22 reported that the daily cost was 2-5-fold higher in French patients with HA and high-responding inhibitors during hospitalization. Costs related to bypassing agents accounted for more than 90% of the total inpatient costs related to CFCs among patients with high-responding inhibitors. The difference in hospitalization costs may be closely related to the duration of hospitalization and, to a lesser extent, to the possible reason for bypassing agent administration.

The proportion of expenditures (rFVII vs. aPCCs) changed dramatically after 2004, and a slightly higher proportion of expenditures was related to aPCCs (53% vs. 47%) in 2007. The NHI has reimbursement criteria for the clinical management of inhibitory antibodies in patients, although on-demand treatment is most common. However, CFC replacement therapy and drug utilization patterns are critically influenced by multiple variables, such as clinical circumstances, patient profiles, individual responses, dose regimen protocol, reimbursement policy, and healthcare service type. Other cost-contributing concerns include the use of immune tolerance induction (ITI) for inhibitor eradication and/or prophylaxis to decrease the frequency of bleeding episodes. Owing to the wide clinical variability and responsiveness to current therapeutic approaches and the scarcity of studies providing high-level evidence for therapeutic guidelines at the present time,11,23 we believe that current strategies for managing these patients are rather heterogeneous, and in our clinical experience, patients do not respond equally well to the various types of bypassing agents in Taiwan. Further studies are encouraged to clarify this issue.

During the 48-month study period, 7 of 37 patients underwent arthroplasty to treat the orthopedic consequences of high-responding inhibitors, corresponding to an incidence rate of 4.2 per 1000 person-months. The incidence rate was 3-fold higher in patients with high-responding inhibitors, which may be attributable to the increasing need for surgery in previous years because of difficulties in performing these interventions. Additionally, aPCCs have been available only since 2004. If this explanation is valid, the estimates from our study are representative of short- and middle-term phenomena, and are likely to decrease in size and importance in the long term.

Furthermore, patients with high-responding inhibitors have more severe degrees of arthropathy and greater difficulties with mobility and daily activities than patients without inhibitors.24,25 Gringeri, et al.11 reported that quality of life and joint scores were significantly improved by the allocation of large amounts of resources to patients with high-responding inhibitors in Italy. In particular, the physical quality of life in these patients was similar to that in patients with severe chronic diseases such as diabetes and dialysis-dependent chronic renal failure, whereas their mental quality of life was comparable to that of the general population. Approximately 4.6% (37/803) of patients with high-responding inhibitors consume approximately 20% of NHI's CFC-related resources annually, suggesting that continued optimization of strategic planning and management with the care network is needed to improve patient quality of care and quality of life. Future studies are encouraged in Taiwan to include the impact on quality of life excluding economic consequences.

The use of the Taiwanese NHI dataset provides the first major evidence of economic burden among an Asian population of patients with high-responding inhibitors. The mandatory NHI program insures >99% of the Taiwanese population, with all geographic regions and populations represented. However, some limitations in the present study should be mentioned. First, we identified patients with high-responding inhibitors via an inhibitor assay and according to the use of rFVIIa and aPCCs in the study. Unfortunately, this methodology may have missed some patients with high-responding inhibitors, particularly children who were treated only with ITI therapy after diagnosis, which usually involves the daily infusion of large doses of FVIII over many months or years. Consequently, the proportion of patients with high-responding inhibitors may have been underestimated. Second, as patients with severe hemophilia patients have been demonstrated to use more CFCs than those with mild and moderate hemophilia, patients with high-responding inhibitors, who generally have severe disease, can potentially account for the increased cost of CFC. Further assessment of the comparing with patients characterized was severe hemophilia in non high-responding inhibitors (412/601, 68.5%). The annual median expenditure related to total medical care and total CFCs costs showed a reduction to 3.0-amd 2.9-fold higher among patients with high-responding inhibitors, respectively. Therefore, it is unlikely that it would materially affect the high economic burden results of our study. Third, CFCs, comprising the most costly component of hemophilia treatment, are administered on the basis of weight. Unfortunately, weight data are not available in NHIRDs. The effect of this limitation on our results is unknown.

In summary, this retrospective study confirmed higher economic burden related to patients with HA and high-responding inhibitors in Taiwan. To best of our knowledge, this is the first major evidence of the economic burden of patients with high-responding inhibitors in Asia, and its findings are consistent with those in Western countries. Moreover, future research is encouraged to include the impact on quality of life excluding economic consequences.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was sponsored by the Hemophilia Care and Research Center in Tri-Service General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, which was also supported by a Baxter Education Fund.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Fischer K, Van Den Berg M. Prophylaxis for severe haemophilia: clinical and economical issues. Haemophilia. 2003;9:376–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannucci PM, Tuddenham EG. The hemophilias--from royal genes to gene therapy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1773–1779. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106073442307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Street A, Hill K, Sussex B, Warner M, Scully MF. Haemophilia and ageing. Haemophilia. 2006;12(Suppl 3):8–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plug I, Peters M, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, de Goede-Bolder A, Heijnen L, Smit C, et al. Social participation of patients with hemophilia in the Netherlands. Blood. 2008;111:1811–1815. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. 2005. [accessed on 2012 October 8]. Available at: http://illinoisaap.org/wp-content/uploads/guidelines-Hemophilia-WHF-2005.pdf.

- 6.Wight J, Paisley S. The epidemiology of inhibitors in haemophilia A: a systematic review. Haemophilia. 2003;9:418–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berntorp E, Shapiro A, Astermark J, Blanchette VS, Collins PW, Dimichele D, et al. Inhibitor treatment in haemophilias A and B: summary statement for the 2006 international consensus conference. Haemophilia. 2006;12(Suppl 6):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diagnosis and Management of Inhibitors to Factors VIII and IX: An Introductory Discussion for Physicians. [accessed on 2011 November 15]. Available at: http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1178.pdf.

- 9.Globe DR, Curtis RG, Koerper MA HUGS Steering Committee. Utilization of care in haemophilia: a resource-based method for cost analysis from the Haemophilia Utilization Group Study (HUGS) Haemophilia. 2004;10(Suppl 1):63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1355-0691.2004.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teitel J. Inhibitor economics. Semin Hematol. 2006;43(2 Suppl 4):S14–S17. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gringeri A, Mantovani LG, Scalone L, Mannucci PM COCIS Study Group. Cost of care and quality of life for patients with hemophilia complicated by inhibitors: the COCIS Study Group. Blood. 2003;102:2358–2363. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Minno MN, Di Minno G, Di Capua M, Cerbone AM, Coppola A. Cost of care of haemophilia with inhibitors. Haemophilia. 2010;16:e190–e201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherishing health insurance for a healthy Taiwan. [accessed on 2011 November 15]. Available at: http://www.nhi.gov.tw/Resource/webdata/Attach_13792_2_cherishing.pdf.

- 14.National Health Insurance in Taiwan 2011 Annual Report. [accessed on 2012 November 15]. Available at: http://www.nhi.gov.tw/Resource/webdata/13767_1_NHI%20IN%20TAIWAN%202011%20ANNUAL%20REPORT.pdf.

- 15.Monthly Bulletin of Statistics of the Republic of China. [accessed on 2011 November 15]. Available at: http://eng.dgbas.gov.tw/public/data/dgbas03/bs7/bulletin_eng/PDF/eng-month10010.pdf.

- 16.Foreign Exchange Rates. [accessed on 2011 November 15]. Available at: http://www.stat.gov.tw/public/data/dgbas03/bs1/handbook/bs5/p3-15.xls.

- 17.Köhler Ulrich, Kreuter Frauke. Data Analysis Using Stata. Texas: StataCorp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goudemand J. Hemophilia. Treatment of patients with inhibitors: cost issues. Haemophilia. 1999;5:397–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.1999.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang H, Sher GD, Blanchette VS, Teitel JM. The impact of inhibitors on the cost of clotting factor replacement therapy in Haemophilia A in Canada. Haemophilia. 1999;5:247–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.1999.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bohn RL, Aledort LM, Putnam KG, Ewenstein BM, Mogun H, Avorn J. The economic impact of factor VIII inhibitors in patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2004;10:63–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ullman M, Hoots WK. Assessing the costs for clinical care of patients with high-responding factor VIII and IX inhibitors. Haemophilia. 2006;12(Suppl 6):74–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gautier P, D'Alche-Gautier MJ, Coatmelec B, Marques-Verdier A, Bertrand MA, Dieval J, et al. Cost related to replacement therapy during hospitalization in haemophiliacs with or without inhibitors: experience of six French haemophilia centres. Haemophilia. 2002;8:674–679. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2002.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gringeri A, Mannucci PM Italian Association of Haemophilia Centres. Italian guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with haemophilia and inhibitors. Haemophilia. 2005;11:611–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2005.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morfini M, Haya S, Tagariello G, Pollmann H, Quintana M, Siegmund B, et al. European study on orthopaedic status of haemophilia patients with inhibitors. Haemophilia. 2007;13:606–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soucie JM, Cianfrini C, Janco RL, Kulkarni R, Hambleton J, Evatt B, et al. Joint range-of-motion limitations among young males with hemophilia: prevalence and risk factors. Blood. 2004;103:2467–2473. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]