Abstract

The intimate anatomic and functional relationship between epithelial cells and endothelial cells within the alveolus suggests the likelihood of a coordinated response during post-pneumonectomy lung growth. To define the population dynamics and potential contribution of alveolar epithelial cells to alveolar angiogenesis, we studied alveolar Type II and Type I cells during the 21 days after pneumonectomy. Alveolar Type II cells were defined and isolated by flow cytometry using a CD45−, MHC class II+, phosphine+ phenotype. These phenotypically defined alveolar Type II cells demonstrated an increase in cell number after pneumonectomy; the increase in cell number preceded the increase in Type I (T1α+) cells. Using a parabiotic wild type/GFP pneumonectomy model, less than 3% of the Type II cells and 1% of the Type I cells were positive for GFP—a finding consistent with the absence of a blood-borne contribution to alveolar epithelial cells. The CD45−, MHC class II+, phosphine+ Type II cells demonstrated the active transcription of angiogenesis-related genes both before and after pneumonectomy. When the Type II cells on day 7 after pneumonectomy were compared to non-surgical controls, 10 genes demonstrated significantly increased expression (p<.05). In contrast to the normal adult Type II cells, there was notable expression of inflammation-associated genes (Ccl2, Cxcl2, Ifng) as well as genes associated with epithelial growth (Ereg, Lep). Together, the data suggest an active contribution of local alveolar Type II cells to alveolar growth.

Introduction

Post-pneumonectomy lung growth is a remarkable example of tissue morphogenesis. In most mammals studied, the removal of one lung results in the compensatory growth of the remaining lung (Hsia et al., 2004). The compensatory lung growth is associated with not only significant cell proliferation, but dramatic capillary angiogenesis as well. Design-based stereology (Muhlfeld et al., 2010) and corrosion cast studies (Konerding et al., 2012) indicate that post-pneumonectomy lung growth is associated with significant post-pneumonectomy angiogenesis; perhaps, between 1 and 3 kilometers of new blood vessels within 14 to 21 days of surgery (Chamoto et al., 2012b). The intimate anatomic and functional relationship between epithelial cells and endothelial cells within the alveolus suggests the likelihood of a coordinated growth response to pneumonectomy.

Previous attempts to characterize the epithelial cell dynamics in the post-pneumonectomy lung have demonstrated significant changes in both the Type I and Type II cell populations. In the normal lung, the cell turnover of both types of alveolar epithelial cells is low; the cell turnover time has been estimated at 4–10 weeks (Blenkinsopp, 1967; Bowden et al., 1968). Most studies using histologic and autoradiographic techniques have shown a dramatic increase in epithelial turnover with lung injury from oxygen (Bowden et al., 1968; Adamson et al., 1970), nitric dioxide (Evans et al., 1973), cadmium (Strauss et al., 1976), bleomycin (Aso et al., 1976), and bacterial pneumonia (Pine et al., 1973); however, similar observations have been made after pneumonectomy (Brody et al., 1978). Post-pneumonectomy compensatory growth has been associated with an increase in Type II cell size (Uhal et al., 1989b; Uhal and Etter, 1993), proliferation (Cagle et al., 1990; Uhal and Etter, 1993; Kaza et al., 2002; Li et al., 2005) and volume density (Hsia et al., 1994; Takeda et al., 1999); post-pneumonectomy Type II cells have also demonstrated an increase in metabolic activity (Uhal et al., 1989a) and gene expression (Li et al., 2005).

Recent studies of post-pneumonectomy angiogenesis have demonstrated a similar transition; that is, pneumonectomy triggers a coincidental change in endothelial cells from a quiescent to rapidly proliferating cell population (Lin et al., 2011). Morphologic evidence indicates that this cell proliferation occurs in discrete regions in the growing lung (Konerding et al., 2012)—a finding suggesting local control. In addition to local proliferation, a blood-derived population of endothelial progenitor cells have been identified (Chamoto et al., 2012b). These blood-derived endothelial cells appear to be rapidly incorporated into the vessel lining (Chamoto et al., 2012b). The similar proliferative time course, as well as their complementary function in gas exchange, suggests that epithelial and endothelial cell dynamics are linked; however, the potential regulatory contribution of Type II cells to alveolar neoangiogenesis is unknown.

In this report, we investigated the hypothesis that alveolar Type II cells regulate post-pneumonectomy angiogenesis. Our objectives were to 1) define the population dynamics of alveolar Type II cells after pneumonectomy—including the potential contribution of blood-derived Type II cells—and 2) define the alveolar Type II transcriptional profile relevant to capillary angiogenesis.

Methods

Mice

Male mice, eight to ten week old wild type C57BL/6 (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), were used for all non-parabiotic experiments. Wild-type (WT) and green fluorescence protein (GFP)+ C57BL/6-Tg (under the direction of the ubiqutin C promoter, UBC) 30Scha/J mice (Jackson Laboratory) with similar age and weights were selected for parabiosis. The care of the animals was consistent with guidelines of the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (Bethesda, MD) and approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Pneumonectomy

After the induction of general anesthesia (Gibney et al., 2011b), the animal was ventilated on a Flexivent (SciReq, Montreal, QC Canada) at ventilator settings of 200/min, 10mL/kg, and PEEP of 2 cmH2O with a pressure limited constant flow profile. A thoracotomy was created in the left fifth intercostal space and a left pneumonectomy was performed by hilar ligation (Gibney et al., 2011a). At the completion of the procedure, the animal was removed from the ventilator and observed for spontaneous respirations. Once spontaneous muscle activity was noted, the animal was extubated and observed in a warming cage. Sham thoracotomy involved an identical incision and thoracotomy. The pleural cavity was entered, but there was no surgical manipulation of the left lung. The thoracotomy closure was identical to the pneumonectomy condition.

Light and transmission electron microscopy

Lungs designated for microscopy were harvested after cannulation of the trachea. The tissue was fixed by instillation of 2.5 % buffered glutaraldehyde into the bronchial system followed by the instillation of 50% OCT Tissue Tec in saline. After post-fixation samples of the cardiac lobe were cut out and processed according to standard protocols and embedded in Epon (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). Semithin section (0.5 um) were stained with tolouidine blue and analysed with a Zeiss Axiophot microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). 700 Å ultrathin sections were analysed using a Leo 906 digital transmission electron microscope (Leo, Oberkochen, Germany).

Parabiotic surgery

The animals were paired using a modification of the technique described by Bunster (Bunster and Meyer, 1933). The animals were anesthetized with a intraperitoneal injection of ketamine 100mg/kg (Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) and xylazine 10mg/kg (Phoenix Scientific, St. Joseph, MO). The right side of the wild type mouse and the left side of the GFP+ mouse were surgically joined as previously described (Gibney et al., 2012). Postoperatively, each parabiont was given a subcutaneous 1 ml bolus of warmed 0.9% sodium chloride (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) twice daily for 48 hours. Analgesia (Buprenorphine, 0.05 mg/kg, Webster Generics, Sterling, MA) was given twice daily for 48 hours and supplemented as clinically indicated. 1% Sulfatrim water (Webster Generics, Sterling, MA) was provided in the cage for 28 days. Left pneumonectomy was performed 28 days after parabiosis.

Cell counting

BAL cells were counted using a Neubauer hemacytometer (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA). Dead cells were excluded by trypan blue (Sigma, St Louis, MO). The numbers of CD11b+ cells were calculated by using flow cytometric analysis: (CD11b+ number) = (total BAL cell number) × (% of CD11b+ cells among total cells)/100.

Monoclonal antibodies

For flow cytometric lung cell analyses, fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), allophycocyanin (APC), PE-Cy7-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were used: anti-CD45 mAb (FITC, rat IgG2b, clone 30-F11, eBioScience), anti-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II mAb (PE-Cy7, Rat IgG2b, clone M5/114.15.2, ebioscience), anti-pan cytokeratin mAb (PE, mouse IgG1, clone C-11, abcam), anti-T1α mAb (PE, hamster IgG, clone eBio8.1.1, eBioscience), anti-CD11b mAb (PE-Cy7, rat IgG2b, clone M1/70, BD Bioscience), anti-CD31 mAb (APC, IgG2a, clone 390, eBioScience), isotype control rat IgG2a (PE, clone eBR2a, eBioScience), isotype control rat IgG2b (PE-Cy7, clone RTK4530, Biolegend), isotype control hamster IgG (PE, clone HTK888, Biolegend) and isotype control mouse IgG1 (PE, clone P3.6.2.8.1, eBioscience).

Phosphine

Phosphine, a lamellar body-staining fluorescent dye, was used to identify Type II epithelial cells (Pfaltz & Bauer, Inc, Waterbury, CT). For optimizing the working concentration of phosphine, digested lung cells (5×105) were stained at the final concentration of 1 ug/ml, 0.1 ug/ml or 0.025 ug/ml for 10 min at 4°C. Phosphine staining was performed concurrently with cell surface staining (CD45, MHC class II). We decided the appropriate concentration at 0.1ug/ml for FACS analysis and Type II epithelial sorting by Aria (BD, Franklin Lakes NJ).

Flow cytometry

For standard phenotyping, the cells were incubated with a 5-fold excess of anti-mouse antibodies directly conjugated with FITC, PE, APC, PE-Cy7 or biotin. The cells stained with biotinylated antibodies were washed by FACS buffer (BD Biosciences) and subsequently stained with streptavidin-RPE (Sigma, St Louis, MO). The cells were analyzed using a FACSCanto II (BD, Franklin Lakes NJ) with tri excitation laser (407nm, 488nm and 633nm ex). The data were analyzed by FCS Express 4 software (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA). In all analyses, debris were eliminated by gating the alive cell population of Side Scatter (SSC) and Forward Scatter (FSC), and further by gating the 7AAD (BD Biosciences)-negative population. For Type II cell isolation, CD45− MHC class II+ phosphine+ population was gated and sorted by FACSAria (BD, Franklin Lakes NJ). Statistical criteria were used for gating the CD45- population, effectively excluding any detectable leukocyte contamination.

PCR arrays

The commercially available Angiogenesis Array (catalog PAMM-024) obtained from SABiosciences (Frederick, MD) was used for all polymerase chain reaction (PCR) array experiments. Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR green qPCR master mixes that include a chemically-modified hot start Taq DNA polymerase (SABiosciences). PCR was performed on ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). For all reactions, the thermal cycling conditions were 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec and simultaneous annealing and extension at 60°C for 1 min. The two sets of triplicate control wells were also examined for inter-well and intra-plate consistency; standard deviations of the triplicate wells were uniformly less than 1 Ct. To reduce variance and improve inferences per array (Kendziorski et al., 2005), we used a design strategy that used 3–4 samples/group (typically 3 mice/sample). Previous comparison of the Angiogenesis Array in non-surgical controls and sham thoracotomy controls demonstrated no difference (Lin et al., 2011).

RNA quality

RNA was extracted using Pico Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems Arcturus Products, Carlsbad CA) according to the instruction. For the rapid analysis of RNA quantity and quality, all samples were analyzed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA), microfluidics-based nucleic acid separation system. In most samples, the RNA Pico 6000 LabChip kit (Agilent Technologies) was used. RNA integrity numbers (RIN) of the RNA samples were uniformly greater than 7.0 (Schroeder et al., 2006).

Statistical analysis

Our quantitative PCR assumed that DNA template and/or sampling errors were the same for all amplifications; our internal control replicates indicated that our sample size was sufficiently large that sampling errors were statistically negligible (Stolovitzky and Cecchi, 1996). The exponential phase of the reaction was determined by a statistical threshold (10 standard deviations). Flow cytometry statistical analysis was based on measurements in at least three different mice. The unpaired Student’s t-test for samples of unequal variances was used to calculate statistical significance. The data was expressed as mean ± one standard deviation. The significance level for the sample distribution was defined as p<.05.

Results

Epithelial cell anatomy

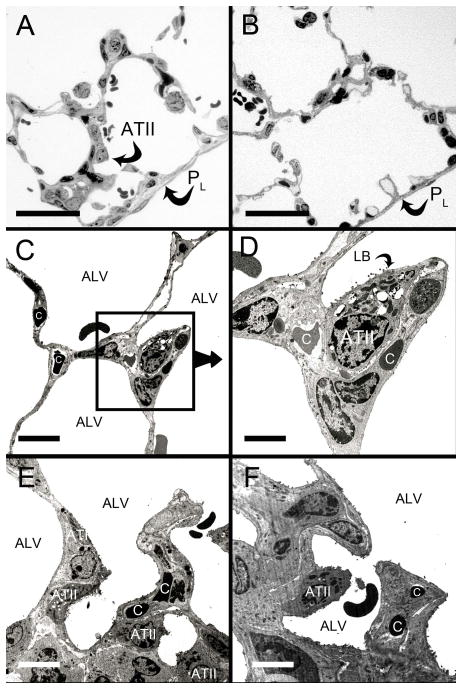

In the evaluation of the alveolar epithelium 9 days after murine pneumonectomy, light microscopy of the cardiac lobe demonstrated thickened subpleural alveolar septae and an apparent increase in alveolar Type II cells compared to non-surgical controls (Figure 1A–1B). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the peripheral cardiac lobe at 3 days (Figure 1C,D) and 9 days (Figure 1E,F) after pneumonectomy demonstrated alveolar Type II cells intimately associated with septal blood vessels. In serial TEM sections, regions were commonly observed with no basal lamina visibly separating the pneumocytes from endothelial cells (not shown).

Figure 1.

Subpleural changes in the cardiac lobe after pneumonectomy. Light microscopic images of semithin sections 9 days after pneumonectomy (A) and control (B). The pleural surface (PL) was lined by mesothelial cells (arrows). The alveolar septa (arrowheads) appeared narrower in the controls. The light microscopic impression of increased numbers of Type II pneumocytes (ATII) was studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). TEM 3 days (C, D) and 9 days (E, F) revealed close spatial correlation between Type II cells, septa and capillaries (C) in the alveoli (ALV). Bars in A and B = 50 μm, in C, E = 30 μm, D= 15 μm, F= 20μm.

Epithelial population dynamics

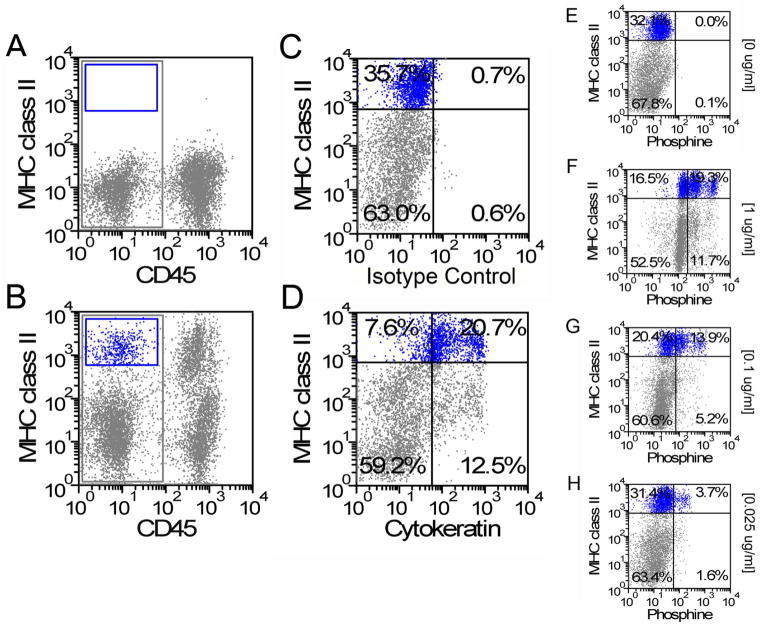

To provide a quantitative assessment of epithelial population dynamics after pneumonectomy, alveolar epithelial cells were studied by flow cytometry. To define alveolar Type II cells, enzymatically digested control (no surgery) lungs were studied by flow cytometry. Based on isotype controls (Figure 2A), 4.7% of the isolated CD45− lung cells were MHC class II+ (Figure 2B). After gating on the CD45− population to exclude leukocyte contamination, 82% of the class II+ population was also cytokeratin+ (Figure 2D). To confirm that the CD45−, class II+, cytokeratin+ cells were predominantly Type II cells, the CD45− cells were exposed to varying concentrations of the lamellar body-staining fluorescent dye phosphine. Based on flow cytometry dose-response studies, alveolar Type II cells were defined as CD45−, class II+, phosphine+ when staining was performed at a phosphine concentration of 0.1 ug/ml.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic definition of alveolar Type II cells. Isotype controls (A) were used to define CD45−, MHC class II+ cells (B). Gating on the CD45−, MHC class II+ cells, the cytokeratin isotype controls (C) permitted a definition of the CD45−, MHC class II+, cytokeratin+ Type II cells (D). Similarly, gating on the CD45−, MHC class II+ cells, a titration of phosphine (E=0ug/ml, F=1ug/ml, G=0.1ug/ml and H=0.025 ug/ml) demonstrated an optimal concentration of 0.1 ug/ml (G).

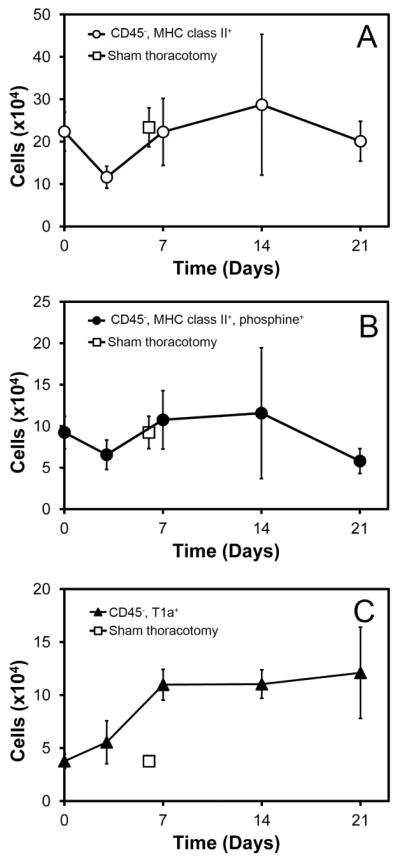

Using this empiric definition of alveolar Type II cells, the post-pneumonectomy right lungs were enzymatically digested and studied by flow cytometry at various times after surgery. The number of non-leukocyte (CD45−) MHC class II+ cells a—phenotype broadly including alveolar Type II cells—demonstrated a relative decrease in cell number on day 3 (Figure 3A). The number of CD45−, MHC class II+ cells increased on day 7 and 14, then decreased on day 21. These results were confirmed by similar studies using phosphine (Figure 3B). In contrast to the decreased number of Type II cells on day 21, cells expressing the alveolar Type I cell marker T1α increased until day 14 (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Population dynamics of alveolar epithelial cells after left pneumonectomy (day 0). A) Number of Type II cells (defined CD45−, MHC class II+) on days 3, 7, 14 and 21 days after pneumonectomy. B) Alveolar Type II cells (defined CD45−, MHC class II+, phosphine+) at the same time points after pneumonectomy. C) Number of alveolar Type I cells (defined as CD45−, T1α+) after pneumonectomy. The cell number on days 7, 14 and 21 was significantly increased relative to both sham and day 0 controls (p<.05). A–C) The sham thoracotomy controls are shown on day 7 (open square). N=4 each time point; error bars reflect ± 1 SD.

Extra-pulmonary contribution

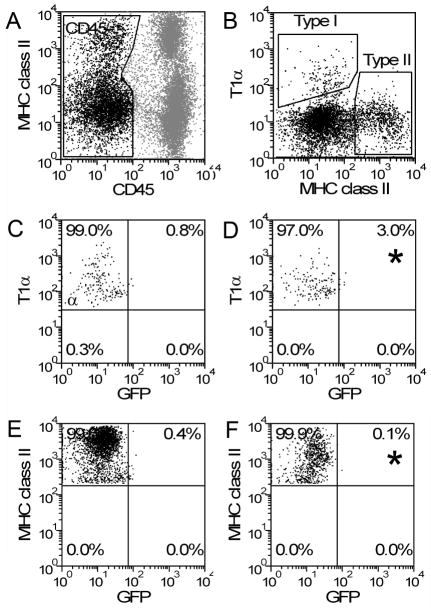

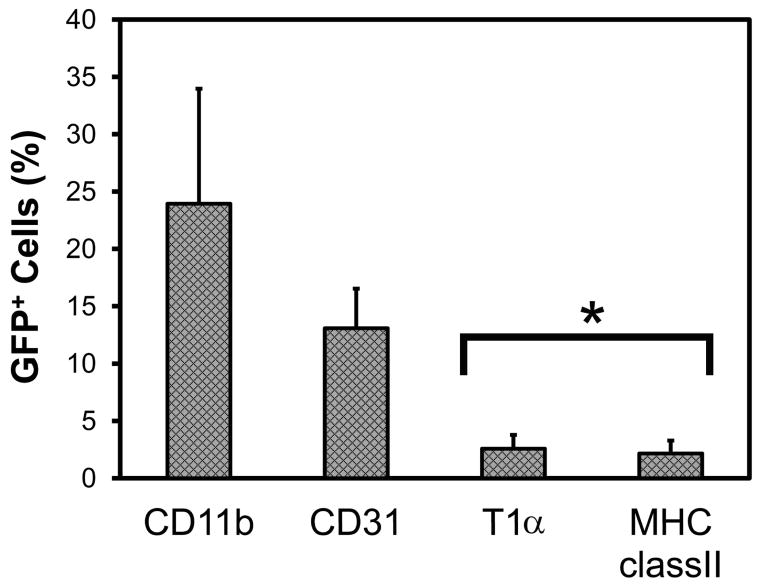

To test the possibility that the post-pneumonectomy increase in alveolar Type II cells reflected a contribution of blood-borne progenitor cells, a parabiotic post-pneumonectomy model was studied. After establishing a complete cross-circulation between WT and GFP parabionts (28 days after parabiotic surgery) (Gibney et al., 2012), a left pneumonectomy was performed. The remaining lung was harvested 14 days after pneumonectomy and the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. After gating on CD45− cells, the cell populations positive for the T1α (Type I cells) and MHC class II (Type II cells) were studied (Figure 4). Less than 3% of the Type II cells were positive for GFP—a finding consistent with the absence of a blood-borne contribution to alveolar epithelial cells. Compared to other cell types—reflecting previously published data (Chamoto et al., 2012a; Chamoto et al., 2012b)—alveolar epithelial cells demonstrated significantly less evidence for blood-derived migration than leukocytes or endothelial cells(p<.001) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Blood-derived Type I and Type II cells on day 14 after pneumonectomy. Pneumonectomies were performed in WT/GFP parabionts with established cross-circulation. The remaining lung was studied on day 14 after pneumonectomy. Gating on CD45− cells (A), the cells defined as Type I (T1α+) and Type II (MHC class II+) were analyzed for GFP expression. Defining regions based on WT Type I (C) and Type II (E) cells, GFP expression was identified in Type I (D) and Type II (F) cells (asterisk).

Figure 5.

Blood-derived cells in the lung on day 14 after pneumonectomy in WT/GFP parabionts. Defined by GFP+ expression, analysis of alveolar Type I (CD45−, T1α+) and Type II (CD45−, MHC class II+) cells demonstrated few GFP+ cells relative to blood-derived leukocytes (CD11b+) and endothelial cells (CD45−, CD31+). N=6–7 mice; p<.001 (asterisk).

Transcriptional profile of Type II cells

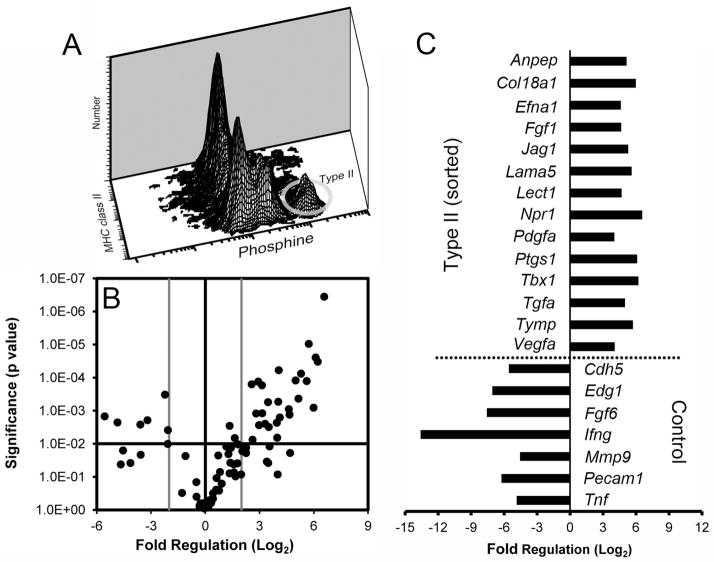

To better characterize the potential regulation of capillary growth by mature alveolar Type II cells, non-surgical control CD45−, MHC class II+, phosphine+ cells were isolated by cell sorting. The angiogenic transcriptional profile of these normal adult mouse alveolar Type II cells was studied by angiogenesis PCR arrays. When compared to a larger group of epithelial and smooth muscle cells (CD11b−, CD31−), the Type II cells demonstrated significantly enhanced expression of 14 angiogenesis-associated genes (p<.01; Figure 6B,C). The gene expression profile included the enhanced expression of the extracellular matrix genes laminin alpha 5 (Lama5) and collagen type XVIIIα1 (Col18a1). Also enhanced was the expression of cell cycle genes controlling of epithelial (Efna1, Jag1 and Tgfa) and mesenchymal (Pdgfa and Vegfa) cells.

Figure 6.

The transcriptional profile of flow cytometry-derived alveolar Type II cells. A) The Type II cells, defined as CD45−, MHC class II+, phosphine+, were identified as a discrete population by multidimensional flow cytometry (ellipse). B) Type II cell angiogenesis gene expression was compared to the larger population of CD45−, CD31− (“Control”) cells using PCR arrays. The log2 fold-change in gene expression was plotted against the p-value (t-test) to produce a “volcano plot.” The vertical threshold reflected the relative statistical significance (black horizontal line, -log10, p < 0.01); the horizontal threshold reflected the relative fold-change in gene expression (gray vertical line, 4-fold). The specific genes with significantly altered expression (gray) are summarized (C). Each plate was replicated 4 times; 2–4 mice were pooled per plate.

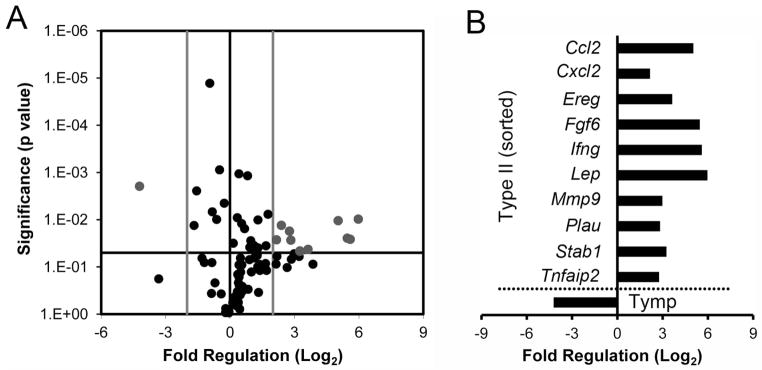

To determine the potential contribution of the flow cytometry-defined Type II cells to compensatory lung growth, the transcriptional activity of the alveolar Type II cells was studied when endothelial gene transcription and cell cycle activity was greatest (Lin et al., 2011); that is, 7 days after pneumonectomy (Figure 7). When the Type II cells on day 7 after pneumonectomy were compared to non-surgical controls, 10 genes demonstrated significantly increased expression (p<.05; Figure 7). In contrast to the normal adult Type II cells, there was notable expression of inflammation-associated genes (Ccl2, Cxcl2, Ifng) as well as genes associated with epithelial growth (Ereg, Lep). Additionally, the enhanced transcription of Mmp9 and Fgf6 indicated an active contribution to structural remodeling and capillary growth.

Figure 7.

Gene transcription of alveolar Type II cells after pneumonectomy. Gene transcription in the remaining lung on day 7 after pneumonectomy was compared to age-matched non-surgical controls. A) The log2 fold-change in gene expression was plotted against the p-value (t-test) to produce a “volcano plot.” The vertical threshold reflected the relative statistical significance (black horizontal line, -log10, p < 0.05); the horizontal threshold reflected the relative fold-change in gene expression (gray vertical line, 4-fold). The specific genes with significantly altered expression (gray) are summarized (B). Enhanced gene transcription in the post-pneumonectomy was demonstrated in 10 genes; one gene (Tymp) was higher in the non-surgical control lungs. PCR arrays were replicated 4 times; 2–4 pooled mice per plate.

Discussion

In this report, we studied the population dynamics and transcriptional activity of flow cytometry-defined alveolar Type II cells after murine pneumonectomy. Our data indicated that 1) alveolar Type II cells, empirically defined as a CD45−, MHC class II+, phosphine+ phenotype, demonstrated an increase in cell number after pneumonectomy; 2) the increase in cell number preceded the increase in Type I (T1α+) cells, and 3) did not appear to involve the contribution of blood-borne Type II (or Type I) cells. 4) The CD45−, MHC class II+, phosphine+ cells demonstrated the active transcription of angiogenesis-related genes both before and after pneumonectomy. Together, the data suggest the local contribution of alveolar Type II cells to alveolar growth.

Our definition of alveolar Type II cells was based on cytologic and morphologic features; that is, cuboidal morphology and ultrastructural lamellar bodies. The cuboidal morphology produced a distinctive “optical phenotype” (Wilson et al., 1986) detected by flow cytometry light scatter analysis. The lamellar bodies, subcellular structures containing the lipid-protein complex of the surfactant system (Ochs, 2010), were detected using the lipid-soluble fluorescent dye phosphine (Uhal and Etter, 1993; Harrison et al., 1995) and flow cytometry. The selectivity of phosphine binding to lamellar bodies has been demonstrated by confocal microscopy (Bakewell et al., 1991). The strength of the phosphine-associated fluorescence signal was attributable to the density of lamellar bodies: Type II cells can contain more than 100 lamellar bodies—collectively comprising nearly 10% of the pneumocyte cell volume (Young et al., 1991).

An intriguing, but poorly understood, phenotypic characteristic of alveolar Type II cells is the high constitutive expression of MHC class II molecules (Cunningham et al., 1997). MHC class II molecules, prominently linked to CD4 T cell antigen presentation, is notably expressed on “professional” antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells, mononuclear phagocytes and B lymphocytes. Although alveolar Type II cells express some of the important processing enzymes linked to the classic MHC class II antigen presentation pathway (Watts, 2004), Type II cells are not potent antigen presenting cells (Cunningham et al., 1997; Corbiere et al., 2011). Although the biological role of the molecule is unclear, the MHC class II molecule was a useful marker for alveolar Type II cell isolation by flow cytometry cell sorting.

Recent interest in the therapeutic potential of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells (Kotton et al., 2001; Theise et al., 2002; MacPherson et al., 2005) has led to more than 40 reports of blood-borne epithelial progenitor cells (Kassmer and Krause, 2010) and several notably negative reports (Wagers et al., 2002; Kotton et al., 2005). The controversy in the field is due, in part, to the difficulty in identifying progenitor cells in the lung by fluorescence microscopy (Kassmer and Krause, 2010). Here, we used a parabiotic cross-circulation (WT/GFP) model to identify potential blood-borne progenitor cells. Compensatory growth after pneumonectomy in the WT parabiont produced an approximate 30% increase lung weight and volume without the infiltration of confounding blood-borne inflammation (Chamoto et al., 2012a; Chamoto et al., 2012b). Because of stable GFP expression, migrating cells provided a “fate map” of blood-borne cells a—marker that was independent of migratory path, differentiation history or surface phenotype. Thus, a blood-derived Type II progenitor cell could be expected to express GFP whether its fate contributed to Type II cells, intermediate epithelial forms, or mature post-mitotic Type I cells. The near-absence of GFP+ Type II or Type I cells in the 21 days after pneumonectomy provided convincing evidence that Type I and II lung epithelial cells are not derived from the peripheral blood, but are locally renewing.

Although our findings seem to conclusively demonstrate the local renewal of Type II epithelial cells, there are several potential limitations. First, it is possible that the putative blood-borne epithelial progenitor cell did not express GFP. Because of the prominent GFP expression of Type II cells in the GFP parabiont, and the uniformly positive fluorescence of peripheral blood cells in the GFP mouse (Gibney et al., 2012), we consider this possibility unlikely. Second, the release of the presumptive progenitor cell from the GFP+ bone marrow might be brief relative to the cross-circulation kinetics; that is, the epithelial progenitor cells in the GFP parabiont might not have sufficient time to equilibrate with the circulation in the WT parabiont. Since we have been able to detect other bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in the WT parabiont after pneumonectomy (Chamoto et al., 2012b), we also consider this possibility unlikely.

Flow cytometry cell sorting provided an opportunity to define the expression of angiogenesis-related genes in normal adult mouse Type II cells. The “constitutive” expression of extracellular genes such as laminin alpha 5 (Lama5) and collagen type XVIIIα1 (Col18a1) is consistent with ongoing maintenance of the lung extracellular matrix. Also notable was the enhanced expression of genes associated with the control of epithelial cell (Efna1, Jag1 and Tgfa) and mesenchymal (Pdgfa and Vegfa) mitogenicity. We interpret this transcriptional activity as reflecting the Type II cells’ control and regulation of the surrounding microenvironment; that is, the adjacent epithelial cells, endothelial cells and extracellular matrix apparent on both light and electron microscopy.

Perhaps more revealing was the change in the Type II cell transcriptional profile after pneumonectomy. Expression of the inflammation-associated chemokine Ccl2 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1; MCP-1) suggests that Type II cells participate in the recruitment of CD11b+ blood-borne cells into the post-pneumonectomy lung. This observation is supported by increased transcription of Cxcl2 (macrophage inflammatory protein 2-alpha; MIP2-alpha), a molecule chemotactic for hematopoietic stem cells (Pelus et al., 2002).

Potentially contributing to epithelial growth was the increased transcription of epiregulin (Ereg) and leptin (Lep). Epiregulin, an epidermal growth factor receptor ligand (EGFR, erbB1), is also a ligand of most members of the ERBB (v-erb-b2 oncogene homolog) family of tyrosine-kinase receptors. The expression of Ereg in epithelial cells (Type II) that give rise to other epithelial cells (Type I) suggests the possibility of both an autocrine and paracrine regulation of epithelial cell growth. The active stimulation of epithelial growth is consistent with the population dynamics we observed after pneumonectomy.

More unexpected was the enhanced transcription of leptin (Lep). Leptin, also known as the product of the OB gene, is synthesized and secreted mainly by white adipose tissue, but it is also expressed in fetal (Bergen et al., 2002) and injured lung tissue (Malli et al., 2010). In addition, there is growing evidence that leptin stimulates endothelial growth and angiogenesis (Bouloumie et al., 1998; Sierra-Honigmann et al., 1998). Finally, data indicates that vascular endothelium in rodents expresses both the short and long forms of the leptin receptor (Margetic et al., 2002). Based on these findings, it is likely that leptin produced by the Type II cell plays an active regulatory role in post-pneumonectomy angiogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants HL75426, HL94567 and HL007734 as well as the Uehara Memorial Foundation and the JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad

Abbreviations

- APC

allophycocyanin

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocynate

- FSC

forward scatter

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- mAb

monoclonal antibodies

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PE

phycoerythrin

- SSC

side scatter

- UBC

ubiqutin C

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Author contribution: KC was the primary investigator; K.C., B.C.G., G.S.L., M.L. and D.C.S performed the experiments and analyzed the data. K.C., M.A.K., A.T. and S.J.M contributed to data analysis and interpretation as well as manuscript development.

References

- Adamson IYR, Bowden DH, Wyatt JP. Oxygen poisoning in mice - ultrastructural and surfactant studies during exposure and recovery. Arch Pathol. 1970;90:463–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aso Y, Yoneda K, Kikkawa Y. Morphologic and biochemical study of pulmonary changes induced by bleomycin in mice. Lab Investig. 1976;35:558–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakewell WE, Viviano CJ, Dixon D, Smith GJ, Hook GER. Confocal laser scanning immunofluorescence microscopy of lamellar bodies and pulmonary surfactant protein-a in isolated alveolar type-II cells. Lab Investig. 1991;65:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen HT, Cherlet TC, Manuel P, Scott JE. Identification of leptin receptors in lung and isolated fetal type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:71–77. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.27.1.4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blenkinsopp WK. Proliferation of respiratory tract epithelium in rat. Exp Cell Res. 1967;46:144–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(67)90416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouloumie A, Drexler HCA, Lafontan M, Busse R. Leptin, the product of Ob gene, promotes angiogenesis. Circ Res. 1998;83:1059–1066. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.10.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden DH, Davies E, Wyatt JP. Cytodynamics of pulmonary alveolar cells in mouse. Arch Pathol. 1968;86:667–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody JS, Burki R, Kaplan N. Deoxyribonucleic-acid synthesis in lung-cells during compensatory lung growth after pneumonectomy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;117:307–316. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.117.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunster E, Meyer RK. An improved method of parabiosis. Anat Rec. 1933;57:339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Cagle PT, Langston C, Goodman JC, Thurlbeck WM. Autoradiographic assessment of the sequence of cellular proliferation in postpneumonectomy lung growth. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1990;3:153–158. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/3.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamoto K, Gibney BC, Ackermann M, Lee GS, Lin M, Konerding MA, Tsuda A, Mentzer SJ. Alveolar macrophage dynamics in murine lung regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2012a doi: 10.1002/jcp.24009. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamoto K, Gibney BC, Lee GS, Lin M, Simpson DC, Voswinckel R, Konerding MA, Tsuda A, Mentzer SJ. CD34+ progenitor to endothelial cell transition in post-pneumonectomy angiogenesis. Am J Resp Cell Mol Biol. 2012b;46:283–289. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0249OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbiere V, Dirix V, Norrenberg S, Cappello M, Remmelink M, Mascart F. Phenotypic characteristics of human type II alveolar epithelial cells suitable for antigen presentation to T lymphocytes. Respir Res. 2011:12. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AC, Zhang JG, Moy JV, Ali S, Kirby JA. A comparison of the antigen-presenting capabilities of class II MHC-expressing human lung epithelial and endothelial cells. Immunology. 1997;91:458–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.d01-2249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, Cabral LJ, Stephens RJ, Freeman G. Renewal of alveolar epithelium in rat following exposure to NO2. Am J Pathol. 1973;70:175–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibney B, Chamoto K, Lee GS, Simpson DC, Miele L, Tsuda A, Konerding MA, Wagers A, Mentzer SJ. Cross-circulation and cell distribution kinetics in parabiotic mice. J Cell Physiol. 2012:227. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibney B, Houdek J, Lee GS, Ackermann M, Lin M, Simpson DC, Chamoto K, Konerding MA, Tsuda A, Mentzer SJ. Mechanical evidence of microstructural remodeling in post-pneumonectomy lung growth. American Thoracic Society; Denver, CO: 2011a. [Google Scholar]

- Gibney B, Lee GS, Houdek J, Lin M, Chamoto K, Konerding MA, Tsuda A, Mentzer SJ. Dynamic determination of oxygenation and lung compliance in murine pneumonectomy. Exp Lung Res. 2011b;37:301–309. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2011.561399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JH, Porretta CP, Leming K. Purification of murine pulmonary type-II cells for flow cytometric cell-cycle analysis. Exp Lung Res. 1995;21:407–421. doi: 10.3109/01902149509023716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia CCW, Berberich MA, Driscoll B, Laubach VE, Lillehei CW, Massaro C, Perkett EA, Pierce RA, Rannels DE, Ryan RM, Tepper RS, Townsley MI, Veness-Meehan KA, Wang N, Warburton D. Mechanisms and limits of induced postnatal lung growth. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:319–343. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200209-1062ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia CCW, Herazo LF, Fryderdoffey F, Weibel ER. Compensatory lung growth occurs in adult dogs after right pneumonectomy. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:405–412. doi: 10.1172/JCI117337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassmer SH, Krause DS. Detection of bone marrow-derived lung epithelial cells. Exp Hematol. 2010;38:564–573. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaza AK, Kron IL, Leuwerke SM, Tribble CG, Laubach VE. Keratinocyte growth factor enhances post-pneumonectomy lung growth by alveolar proliferation. Circulation. 2002;106:I120–I124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendziorski C, Irizarry RA, Chen KS, Haag JD, Gould MN. On the utility of pooling biological samples in microarray experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4252–4257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500607102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konerding MA, Gibney BC, Houdek J, Chamoto K, Ackermann M, Lee G, Lin M, Tsuda A, Mentzer SJ. Spatial dependence of alveolar angiogenesis in post-pneumonectomy lung growth. Angiogenesis. 2012;15:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9236-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotton DN, Fabian AJ, Mulligan RC. Failure of bone marrow to reconstitute lung epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:328–334. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0175RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotton DN, Ma BY, Cardoso WV, Sanderson EA, Summer RS, Williams MC, Fine A. Bone marrow-derived cells as progenitors of lung alveolar epithelium. Development. 2001;128:5181–5188. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DC, Fernandez LG, Dodd-o J, Langer J, Wang DM, Laubach VE. Upregulation of hypoxia-induced mitogenic factor in compensatory lung growth after pneumonectomy. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:185–191. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0325OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, Chamoto K, Gibney B, Lee GS, Collings-Simpson D, Houdek J, Konerding MA, Tsuda A, Mentzer SJ. Angiogenesis gene expression in murine endothelial cells during post-pneumonectomy lung growth. Resp Res. 2011;12:98. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson H, Keir P, Webb S, Samuel K, Boyle S, Bickmore W, Forrester L, Dorin J. Bone marrow-derived SP cells can contribute to the respiratory tract of mice in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2441–2450. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malli F, Papaioannou AI, Gourgoulianis KI, Daniil Z. The role of leptin in the respiratory system: an overview. Respir Res. 2010;11:152. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margetic S, Gazzola C, Pegg GG, Hill RA. Leptin: a review of its peripheral actions and interactions. Int J Obes. 2002;26:1407–1433. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlfeld C, Weibel ER, Hahn U, Kummer W, Nyengaard JR, Ochs M. Is length an appropriate estimator to characterize pulmonary alveolar capillaries? A critical evaluation in the human lung. Anat Rec. 2010;293:1270–1275. doi: 10.1002/ar.21158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs M. The Closer we Look the more we See? Quantitative Microscopic Analysis of the Pulmonary Surfactant System. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;25:27–40. doi: 10.1159/000272061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelus LM, Horowitz D, Cooper SC, King AG. Peripheral blood stem cell mobilization - A role for CXC chemokines. Crit Rev Oncol/Hematol. 2002;43:257–275. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine JH, Richter WR, Esterly JR. Experimental lung injury I. bacterial pneumonia - ultrastructural autoradiographic and histochemical observations. Am J Pathol. 1973;73:115–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder A, Mueller O, Stocker S, Salowsky R, Leiber M, Gassmann M, Lightfoot S, Menzel W, Granzow M, Ragg T. The RIN: an RNA integrity number for assigning integrity values to RNA measurements. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Honigmann MR, Nath AK, Murakami C, Garcia-Cardena G, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC, Madge LA, Schechner JS, Schwabb MB, Polverini PJ, Flores-Riveros JR. Biological action of leptin as an angiogenic factor. Science. 1998;281:1683–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolovitzky G, Cecchi G. Efficiency of DNA replication in the polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12947–12952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss RH, Palmer KC, Hayes JA. Acute lung injury induced by cadmium aerosol I. evolution of alveolar cell damage. Am J Pathol. 1976;84:561–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda SI, Hsia CCW, Wagner E, Ramanathan M, Estrera AS, Weibel ER. Compensatory alveolar growth normalizes gas-exchange function in immature dogs after pneumonectomy. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:1301–1310. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.4.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theise ND, Henegariu O, Grove J, Jagirdar J, Kao PN, Crawford JM, Badve S, Saxena R, Krause DS. Radiation pneumonitis in mice: A severe injury model for pneumocyte engraftment from bone marrow. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:1333–1338. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00931-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhal BD, Etter MD. Type II pneumocyte hypertrophy without activation of surfactant biosynthesis after partial pneumonectomy. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:L153–159. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.2.L153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhal BD, Hess GD, Rannels DE. Density-independent isolation of type-II pneumocytes after partial pneumonectomy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1989a;256:C515–C521. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.3.C515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhal BD, Rannels SR, Rannels DE. Flow cytometric identification and isolation of hypertrophic type-II pneumocytes after partial pneumonectomy. Am J Physiol. 1989b;257:C528–C536. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.257.3.C528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagers AJ, Sherwood RI, Christensen JL, Weissman IL. Little evidence for developmental plasticity of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2002;297:2256–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.1074807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C. The exogenous pathway for antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class II and CD1 molecules. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:685–692. doi: 10.1038/ni1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JS, Steinkamp JA, Lehnert BE. Isolation of viable type II alveolar epithelial cells by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1986;7:157–162. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990070206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SL, Fram EK, Spain CL, Larson EW. Development of type-II pneumocytes in rat lung. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:L113–L122. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1991.260.2.L113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]