Background: Roots can alter the rhizosphere microbial composition presumably by the secretion of root exudates.

Results: Natural blends of phytochemicals present in the root exudates can modulate the soil microbiome in the absence of the plant.

Conclusion: Different groups of compounds impact soil microbe composition at various levels.

Significance: Identifying natural mixes of compounds that could positively influence plant-microbiome interactions can increase crop yield and sustainability.

Keywords: Amino Acid, Plant Biochemistry, Plant Defense, Plant Physiology, Signaling, Sugar Transport, Arabidopsis, Phytochemicals, Soil Microbiome

Abstract

The roots of plants have the ability to influence its surrounding microbiology, the so-called rhizosphere microbiome, through the creation of specific chemical niches in the soil mediated by the release of phytochemicals. Here we report how these phytochemicals could modulate the microbial composition of a soil in the absence of the plant. For this purpose, root exudates of Arabidopsis were collected and fractionated to obtain natural blends of phytochemicals at various relative concentrations that were characterized by GC-MS and applied repeatedly to a soil. Soil bacterial changes were monitored by amplifying and pyrosequencing the 16 S ribosomal small subunit region. Our analyses reveal that one phytochemical can culture different operational taxonomic units (OTUs), mixtures of phytochemicals synergistically culture groups of OTUs, and the same phytochemical can act as a stimulator or deterrent to different groups of OTUs. Furthermore, phenolic-related compounds showed positive correlation with a higher number of unique OTUs compared with other groups of compounds (i.e. sugars, sugar alcohols, and amino acids). For instance, salicylic acid showed positive correlations with species of Corynebacterineae, Pseudonocardineae and Streptomycineae, and GABA correlated with species of Sphingomonas, Methylobacterium, Frankineae, Variovorax, Micromonosporineae, and Skermanella. These results imply that phenolic compounds act as specific substrates or signaling molecules for a large group of microbial species in the soil.

Introduction

It is assumed that the roots of plants create physical and chemical niches that allow the colonization of microbes in the rhizosphere, the soil immediately surrounding the roots of a plant. Increasing evidences demonstrate that plants predominantly drive and shape the selection of microbes (1–5) by the active secretion of compounds that specifically stimulates or represses distinct microbial members of the soil community (6–9) in order to shape the rhizosphere microbiome (5, 10). For example, legumes exude specific flavonoids that act as signaling molecules to attract nitrogen-fixing bacteria (11). Yet when soil nitrogen is not limiting to the plant, this symbiosis does not occur (12). On the other hand, certain legumes release canavanine, an antimicrobial that acts against a broad range of microbes without affecting Rhizobia, which further cultures this beneficial microbe in the rhizosphere of legumes (13). Other plant roots release strigolactones (sesquiterpenes) to attract mycorrhizae, and parasitic plants have benefited from these chemical cues to recognize their host plants (14, 15). Plants can also culture beneficial microbes such as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria by the release of organic acids. For example, citric and fumaric acids released from tomato roots have been shown to attract Pseudomonas fluorescens strains (16, 17). Besides these specific signaling molecules, sugars serve as sources of energy for a broad range of microbes (18), and secondary metabolites such as phenolics may function as general antimicrobials (16, 19–21).

Two recent studies have characterized the core rhizosphere microbiome of Arabidopsis, which is mainly comprised of the groups Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes, which are common inhabitants of diverse soils (22–27). Furthermore, the root exudates of a loss-of-function Arabidopsis mutant in an ABC transporter was found to have an increase in phenolic compounds and a decline in sugars compared with the wild type (28). When this mutant was grown in soil, it elicited dramatic quantitative and qualitative changes in the Arabidopsis native soil microbial community; it cultivated a microbial community with a relatively greater abundance of beneficial bacteria (i.e. plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and nitrogen fixers). These studies suggest a correlation between components in the root exudates and the soil microbiome as a whole.

The goal of this study was to get a finer and initial understanding of how the chemical diversity present in the root exudates of plants can promote or inhibit the growth of specific groups within a natural soil microbiome in the absence of the plant. For this purpose we collected, fractionated, and chemically characterized root exudates of in vitro grown Arabidopsis thaliana plants and repeatedly supplemented those fractions to Arabidopsis co-adapted soil (defined as a natural soil that has supported growth of Arabidopsis for a long period of time) without the presence of Arabidopsis. The soil microbial communities related to each fraction were characterized by 454 sequencing, and correlation analysis between microbial groups and phytochemicals was conducted.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant Growth Conditions and Collection of Root Exudates

A. thaliana wild type (Col-0) seeds were surface-sterilized with Clorox® (laundry bleach) for 1 min followed by four rinses in sterile distilled water and plated on full-strength Murashige and Skoog agar media supplemented with 3% sucrose. Plates were incubated in a growth chamber (Percival Scientific) at 25 °C, with a photoperiod of 16h of light/8 h of dark for germination. We followed the methodology for collecting root exudates described by Badri et al. (28–31). Briefly, 7-day-old seedlings were transferred to 6-well culture plates, each well containing 5 ml of liquid Murashige and Skoog (full strength Murashige and Skoog salts supplemented with 1% sucrose); these were incubated on an orbital shaker at 90 rpm and illuminated under cool white fluorescent light (45 μmol m−2 s−1) with a photoperiod of 16-h light/8-h dark at 25 ± 2 °C. When plants were 18 days old they were gently washed with sterile distilled water to remove the surface-adhering exudates and transferred to new 6-well plates containing 5 ml of sterile distilled water and incubated for 3 days on an orbital shaker under the same conditions described above. We used sterile distilled water to prevent the interference of exogenously supplemented salts and sucrose present in the Murashige and Skoog liquid media in subsequent GC-MS analyses of the root exudates. The 3-day period of incubation did not create any visible toxicity symptoms on the plants (supplemental Fig. S1) as has been previously reported (18–21). The particular window frame of collection of exudates (18–21 days) was selected because during this period Arabidopsis roots were reported to secrete a high diversity of phytochemicals (18–21). The exudates contained in the media were collected and filtered using nylon filters of pore size 0.45 μm (Millipore) to remove root sheathing and root border-like cells. By following this method, we collected a total of three liters of root exudates by growing 600 individual Arabidopsis plants in 6-well plates. We pooled all the root exudates collected from 600 individual Arabidopsis plants for further fractionation analyses. In other words we considered that these 3 liters of pooled root exudates represented 600 individual biological replicates. It should be noted that the profiles of root exudates of Arabidopsis 18–21-day-old plants have been previously reported and found to be consistent and reproducible (28–31).

Fractionation of Root Exudates

Filtered root exudate were freeze-dried and dissolved in 25 ml of sterile distilled water, and the pH was adjusted to 2 with 1 n HCl and partitioned with 25 ml of ethyl acetate; the organic phase (ethyl acetate) was separated and dried under nitrogen gas. The aqueous phase was subsequently fractionated with 25 ml of chloroform to separate the organic (chloroform) and water phases. For each solvent type, we performed the extraction two times and then pooled the extractions together. Both fractions were collected independently and dried under nitrogen gas. At the end we had three types of fractions: an ethyl acetate (EtoAc) fraction, a chloroform (CHCl3) fraction, and a water fraction. Exudates collected from the plants without fractionation served as whole exudates.

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analyses of Exudate Fractions and Data Analyses

The fractions and whole exudates were subjected to GC-MS analyses at the Genome Center Core Services, University of California Davis to identify the compounds present in each fraction. Briefly, the whole exudates and fractions were dried under nitrogen gas followed by methoximation and trimethylsilylation derivatization as described by Sana et al. (32). An Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph (Santa Clara, CA) containing a 30-m-long, 0.25-mm inner diameter rtx5Sil-MS column with an additional 10 m integrated guard column was used to run the samples controlled by Leco ChromaTOF software Version 2.32 (St. Joseph, MI). The resulting text files were exported to the data server with absolute spectra intensities and further processed by a filtering algorithm implemented in the metabolomics BinBase database (33). Quantification was reported as peak height using the unique ion as default. Metabolites were unambiguously assigned by the BinBase identifier numbers using retention index and mass spectrum as the two most important identification criteria. Additional confidence criteria were used by giving mass spectral metadata using the combination of unique ions, apex ions, peak purity, and signal/noise ratios. All entries in BinBase were matched against the Fiehn mass spectral library. Data normalization was performed as described in Fiehn et al. (34) by using “total metabolite content.” Furthermore, we determined the concentration of four target analytes (d-(+) glucose, serine, valine, and salicylic acid) based on the average of two six-point calibration curves for each analyte. The response for the analytes (glucose, serine, and valine) producing multiple derivatization products were summed before calculating the linear calibration curves. Final analyte masses were adjusted to sample preparation volume and were reported in nanomoles.

Supplementing Exudate Fractions to Arabidopsis Co-adapted Soil

Top soil (0–10 cm) was collected in July, 2011 from long standing fallow soil where Arabidopsis genotypes grow naturally. This field has been fallow for approximately more than eight years and is located at the Michigan Extension Station, Benton Harbor, MI (N42° 05′ 34″, W86° 21′ 19″ W, elevation 630 feet). Recently, it was reported that the Arabidopsis genotype Pna-10 that harbors a sng1 mutation grows naturally on this site (35) along with some natural grasses. Soil was collected from three spots at this location, transported to the laboratory in air tight coolers, and stored in a cold room (4 °C) until use. Before the start of the experiment, all soils collected from the three spots were dried under room temperature, pooled, and thoroughly homogenized by hand. Cubical pots (length 2.0 × width 1.0 × diameter 2.0 inches) were lined with Whatman No. 3MM filter paper to prevent soil loss. The pots were then filled with soil and incubated in a growth chamber under the photoperiod of 16 h of light/8 h of dark at 25 ± 2 °C for 2 weeks and sufficiently watered before supplementing them with the exudate fractions. During this 2-week period, the Arabidopsis seedlings (that were present in the natural soil) were continuously removed from the existing seed bank present in the soil. After complete removal of the existing seed bank seedlings, the exudate fractions were independently supplemented to each of the pots, of which none contained a plant. In total, there were eight treatments including controls: pots supplemented with whole exudates, EtoAc fraction, CHCl3 fraction, water fraction, and four controls (only the solvents methanol (2%), chloroform (2%), and sterile water; the negative control pots received no solvents). For each treatment nine pots (considered as nine biological replicates) were maintained, and each pot received 2 ml of solution, which is equivalent to the root exudates of two plants. Additionally, we determined the absolute concentrations of four marker analytes present in each fraction and whole exudates that were supplemented to the soil (supplemental Table S1 and S2). These fractions were added twice a week with an interval of 3 days between fractions for 4 weeks. None of the pots received additional supplementation of water during the experimental period. The soil samples were collected at the end of the 4-week period. The collected soils were stored at −80 °C before pyrosequencing. Furthermore, we made three soil replicates by pooling three sub replicates into one for subsequent pyrosequencing analysis to improve the coverage of the microbiome and to reduce the variability between the replicates within a given treatment (supplemental Fig. S2).

Soil DNA Extraction and Pyrosequencing

To characterize the soil microbial community, total DNA was extracted from soil by using a MoBio ultraclean soil DNA kit (Mo Bio, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA was quantified using a Nanodrop (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) spectrophotometer, and all DNA had an absorbance ratio (A260/A280) between 1.7 and 1.9. PCR amplification was performed by using the primer pairs 27F (AGAGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG) and 533R (TTACCGCGGCTGCTGGC) with 454 adaptor (454 Life Sciences, Branford, CT) and 10-base-long barcode sequences, which are not shown here, to amplify the variable regions (V1-V3) of 16 S ribosomal small subunit region with the following PCR conditions: the reaction mix (50 μl) contained 0.4 μmol of each primer, 200 μmol of dNTPs, 1× reaction buffer, and 1 unit of TaqDNA polymerase (Takara). PCR included 39 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min in an Applied Biosystems thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR system 2700). For each exudate fraction applied to the soil, nine biological replicates were subjected to PCR amplification. At the end of the PCR procedure, three biological replicates were derived from the nine biological replicates by pooling three samples together. After pooling, the PCR products were purified using AMPure XP beads (Agencourt) before running the agarose gel electrophoresis. The specific amplicon product (∼600 bp) was excised from the gel using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified amplicon products were subjected to unidirectional pyrosequencing by using a 454 GS FLX Titanium sequencing platform. Pyrosequencing was performed under contract with Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Sequencing Analysis

Sequence reads were processed using Mothur v. 1.25.1 (36) following the Schloss SOP. Reads having a minimum flow length of 360 flows were de-noised. This was done by processing through the default parameters of the Mothur-based re-implementation of the PyroNoise algorithm (37). De-noised reads were screened by the following quality criteria: no more than 2 mismatches to the forward primer sequence, no more than 1 mismatch in the barcode sequence (for sample multiplexing), no homopolymeric runs of more than 8 nucleotides, and read length of greater than 200 bases. Reads passing these quality criteria were aligned to the Silva bacterial reference database (38). Aligned reads were screened to begin at the same position. Reads were removed if they did not reach the position at which 95% of reads ended. Chimeras were detected using the UChime method (39) and excluded from further analysis. Sampling effort was equalized to the depth of the smallest sample (2185 reads) and operational taxonomic units (OTUs)6 were defined at 3% sequence dissimilarity, with the average neighbor algorithm. Reads were classified using the naïve Baysian classifier embedded in Mothur (40). Final taxonomic assignment was based on the consensus identification for each OTU. A multivariate data analysis was performed by using METAGENassist a web server tool (41) that assigns probable microbial functions based on taxonomy (16 S ribosomal subunit). Data-filtering was performed by the interquantile range method followed by quantile normalization within replicates after log transformation. Principal component analyses and identification of significant features were performed for all treatments together. Cluster analysis was performed using the Ward method.

Statistical Analysis

We computed the Pearson correlation of the OTU abundances to the exudate fractions using SAS Version (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For the data to follow a normal distribution, it was transformed. For the GC-MS data of the root exudate fractions, the peak area of each identified compound underwent a log transformation. On the other hand, the abundance of each OTU in each sample were normalized using a log2 transformation procedure and subsequently standardized to a mean of 0 and S.D. of 1 as is usually implemented for microarray data (42). The average of the transformed OTU abundances for each treatment was correlated to the transformed GC-MS-identified compounds found in each treatment. A p value of <0.05 indicated a significant correlation.

RESULTS

Composition of Compounds in Each Fraction by GC-MS Analyses

In total, we detected 415 compounds in the fractions and whole exudates. We observed that all identified compounds were present in all the fractions, but the abundance of a particular compound in each fraction varied. Furthermore, we identified 130 compounds by broadly categorizing them based on its chemical nature (i.e. sugars, sugar alcohols, amino acids, and phenolics). The phenolics category includes organic acids, fatty acids, and aliphatic and aromatic amino acids. In total we identified 12 sugars, 11 sugar alcohols, 29 amino acids, and 59 phenolic compounds (supplemental Table S3). The fractionation of exudates modified the composition of the major types of compounds present in a particular fraction compared with the whole exudates (Table 1). For instance, the water fraction had a higher abundance of amino acids (29.55 versus 9.85%) and phenolics (32.01 versus 18.55%) compared with the whole exudates. Similarly, the CHCl3 fraction had a higher concentration of sugars (27.25 versus 3.10%) compared with the whole exudates. The EtoAc fraction showed an increase in amino acids (21.47 versus 9.85%) and phenolics (30.24 versus 18.55%) compared with the whole exudates. It should be noted that in all fractions as well as in the whole exudates the unknowns accounted for the highest percentage of compounds.

TABLE 1.

Abundance (%) of different categories of compounds present in the whole exudates and fractions of exudates analyzed by GC-MS

The percentage of the compounds in each category was calculated by dividing the sum of compounds in each category with the sum of compounds in all categories.

| Categories | Water fraction | CHCl3 fraction | EtoAc fraction | Whole exudates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugars | 2.20 | 27.25 | 1.74 | 3.10 |

| Amino acids | 29.55 | 10.87 | 21.47 | 9.85 |

| Sugar alcohols | 2.08 | 1.12 | 2.69 | 3.80 |

| Phenolics | 32.01 | 18.56 | 30.24 | 18.55 |

| Unknown | 34.13 | 42.18 | 43.85 | 64.68 |

Influence of Whole Exudates and Fractions on Soil Microbial Composition

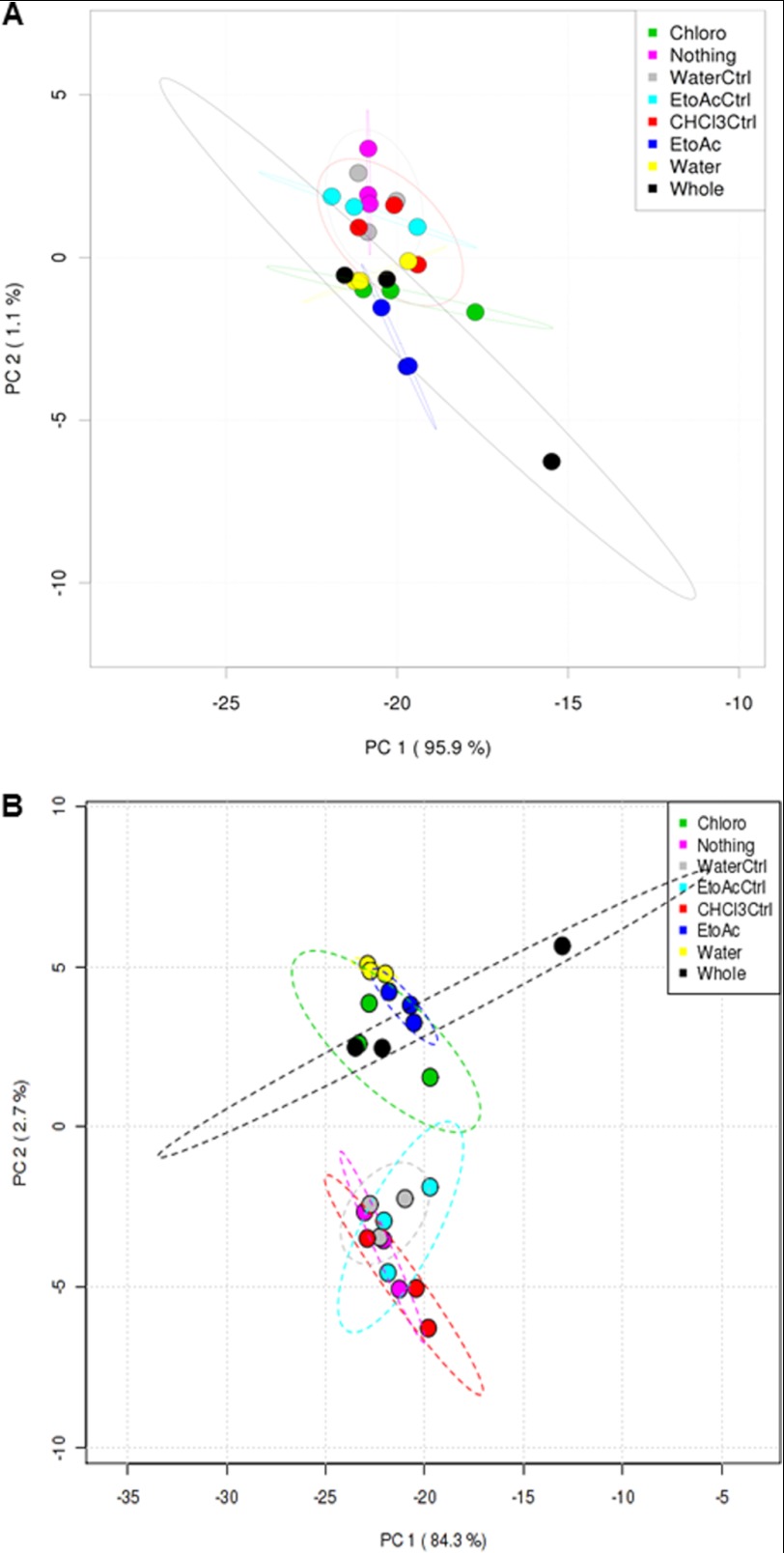

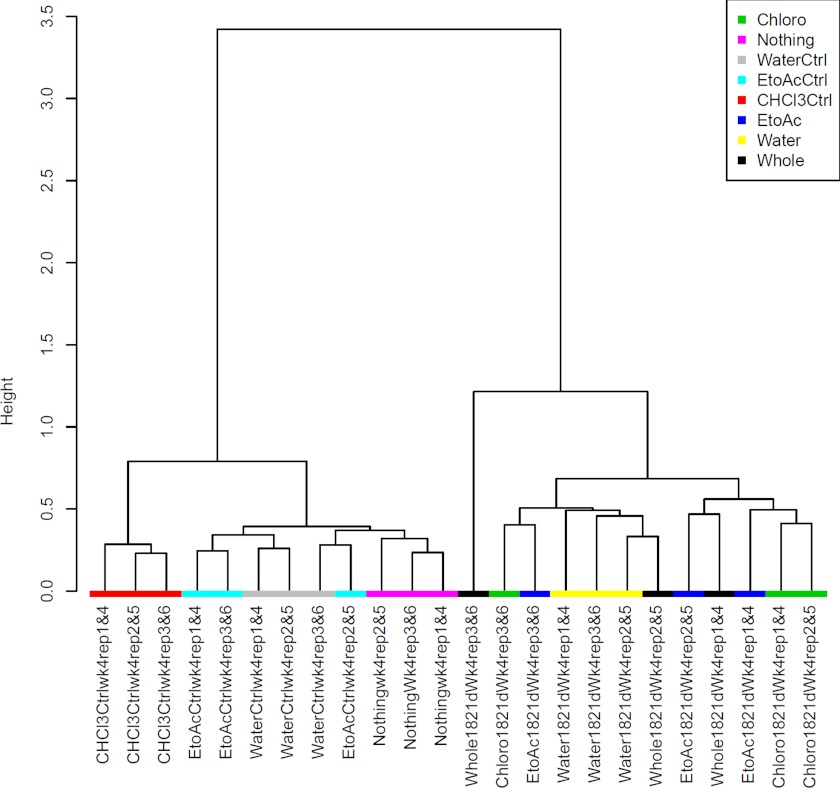

We analyzed the influence of the water/solvent-extracted fractions, whole exudates, and their respective controls on the soil microbial community structure by 454 pyrosequencing analyses. We used principal component analyses on pair-wise and normalized OTUs between all treatments to identify the main factors driving community composition differences. Based on our principal components analysis analyses, we did not observe significant differences between the treatments and controls at phylum level (Fig. 1A). However, we observed that the controls (nothing added, water, CHCl3, and EtoAc) and treatments (water, CHCl3, EtoAc fractions, and whole exudates) formed two different clusters at the genus level (Fig. 1B). The second principal component (2.7%) revealed that the controls separated from their respective treatments. This pattern was recapitulated by hierarchical clustering using Ward method where controls clustered separately from the treatments (Fig. 2). These data clearly indicate that the compounds present in the whole root exudates and extracted fractions have a significant impact on the soil microbial composition.

FIGURE 1.

Soil microbiome sequencing data of treatments and controls analyzed by principal component analyses at phyla levels (A) and genus levels (B). Whole, whole exudates; Chloro, CHCl3 fraction; EtoAc, ethyl acetate fraction; Water, water fraction; Nothing, nothing added in the soil; Water ctrl, water control; EtoAc ctrl, ethyl acetate control; CHCl3 Ctrl, chloroform control.

FIGURE 2.

Cluster analysis of the soil microbiome sequencing data of controls and treatments by Ward method. Whole, whole exudates; Chloro, CHCl3 fraction; EtoAc, ethyl acetate fraction; Water, water fraction; Nothing, nothing added in the soil; Water ctrl, water control; EtoAc ctrl, ethyl acetate control; CHCl3 Ctrl, chloroform control.

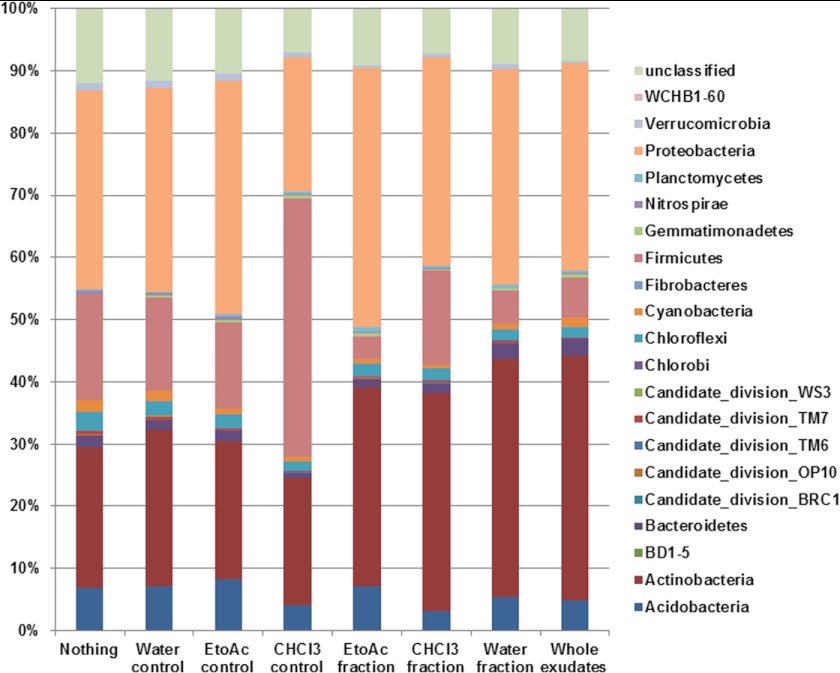

We also determined the total estimated species richness, evenness, and diversity of the sequencing data of all controls and treatments, and only the CHCl3 control showed significant differences in the evenness compared with other control and treatments (Table 2). Furthermore, we performed the analysis of variance and Tukey post-hoc significance test to determine significant differences at the phylum level in pair-wise combinations of all controls and treatments. Overall, we classified all the OTUs into 21 phyla; among those Proteobacteria showed a higher abundance in all the controls and treatments followed by Actinobacteria (Fig. 3). However, the EtoAc fraction showed a significantly higher abundance of Proteobacteria, and the water fraction showed a significantly higher abundance of Actinobacteria compared with the other controls and treatments. Interestingly, the CHCl3 control treatment showed an increased abundance of Firmicutes than the other treatments and controls.

TABLE 2.

Total observed (Sobs) and estimated (Chao and ACE) species richness, evenness, and diversity (Shannon) of the soil samples supplemented with whole exudates and their fractions with respective controls

“Nothing represents “negative control,” which means none added in those soils.

| Treatments | Richness |

Shannon |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sobs | Chao | ACE | Evenness | Diversity | |

| Nothing | 1227.67 | 3790.93 | 7419.23 | 0.92 | 6.57 |

| Water control | 1140.00 | 3415.79 | 6643.4 | 0.93 | 6.53 |

| CHCl3 control | 987.67 | 3276.23 | 6216.58 | 0.83a | 5.70 |

| EtoAc control | 1033.33 | 3082.48 | 5997.75 | 0.92 | 6.39 |

| Water fraction | 1288.00 | 3411.12 | 4993.73 | 0.96 | 6.84 |

| CHCl3 fraction | 957.67 | 2687.32 | 4466.56 | 0.92 | 6.29 |

| EtoAc fraction | 849.67 | 1849.17 | 2623.46 | 0.92 | 6.17 |

| Whole exudates | 1009.67 | 2998.14 | 5259.03 | 0.95 | 6.44 |

a Significantly different at p value 0.05.

FIGURE 3.

Relative abundance (%) of the major bacterial phyla present in the treatments and controls revealed by pyrosequencing.

OTUs Present Uniquely for a Given Treatment

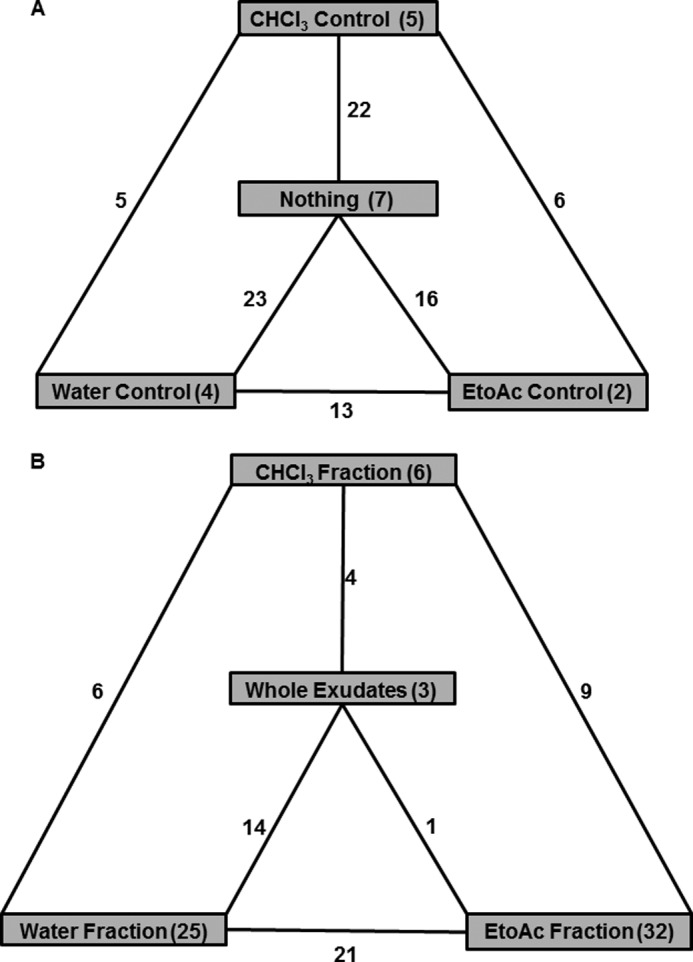

We performed qualitative analyses to identify the OTUs shared by all treatments and controls and also uniquely present in a given treatment or control (Fig. 4). We identified 138 OTUs shared by all four controls (nothing added, CHCl3, EtoAc, and water). Similarly, only 11 OTUs were shared by all four treatments (whole exudates, water, EtoAc, and CHCl3 fractions). We also identified OTUs that were specific to a given treatment or control. The controls (nothing added, CHCl3, water, and EtoAc) cultured seven, five, four, and two unique OTUs (Fig. 4A). Similarly, the treatments revealed that 3, 6, 25, and 32 OTUs are unique to whole exudates, CHCl3, water, and EtoAc fractions, respectively (Fig. 4B). Among the four treatments, the EtoAc fraction cultured a higher number (32) of specific OTUs including Methylobacterium, Sphingomonas, Pseudocardineae, and Bradyrhizobium. The water fraction cultured the second highest number of OTUs (25) including Micromonosporineae, Skermanella, Burkholderia, Varivorax, and Frankineae (supplemental Table S4). Similarly, the CHCl3 fraction cultured only six OTUs including species of Propionibacterineae, Bacillus, Streptomycineae, Duganella, and unclassified.

FIGURE 4.

Flow diagram indicating the shared and unique OTUs present in controls and treatments. Controls (A) and treatments (B) are shown. Overall, 138 OTUs were shared by controls, and 11 OTUs were shared by treatments. The number of OTUs unique to a particular control or treatment is represented inside the shaded box, and the number of OTUs shared between the controls and treatments is represented in the intersections.

Taxonomic to Phenotype Mapping

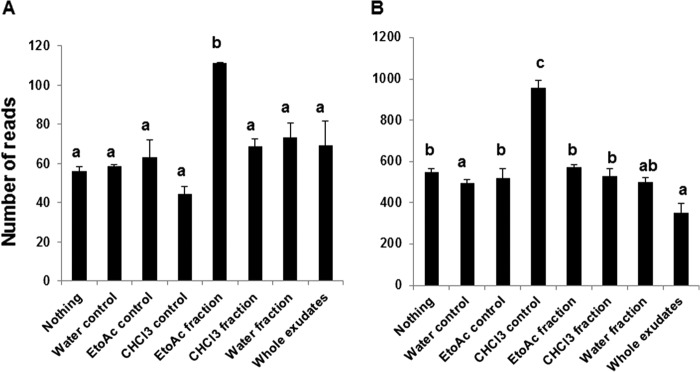

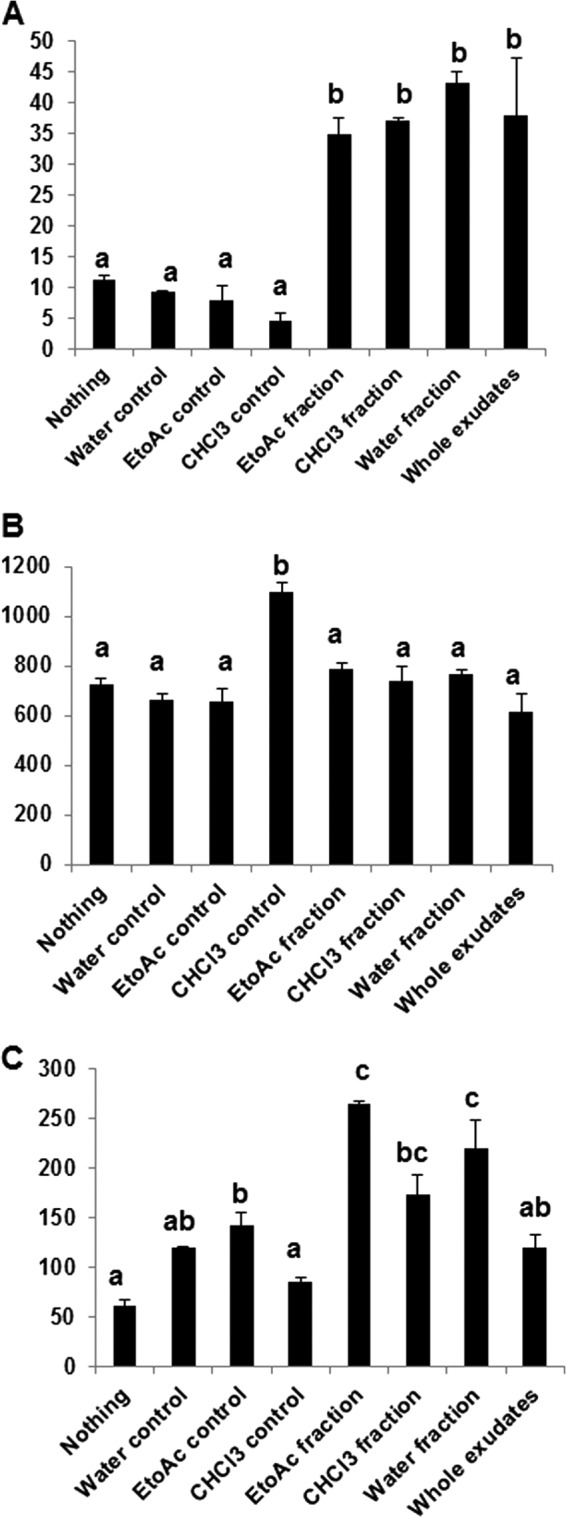

We assigned the OTUs from taxonomic to phenotype mapping by employing METAGENassist webserver tool (41) for nearly 20 phenotype categories classified based on oxygen requirement, metabolism, energy source, habitat, etc. Based on our analyses we observed that only two categories, habitat and metabolism, showed significant differences in the abundance of sequence reads among the 20 phenotype categories analyzed in this study. For instance, the EtoAc fraction significantly enriched the number of sequence reads assigned to symbiotic bacteria (Fig. 5A), whereas the CHCl3 control enriched the number of sequence reads assigned to free-living bacteria (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, whole exudates showed the least number of free-living bacteria compared with other controls and treatments. In the metabolism category all the controls significantly reduced the number of sequence reads assigned to carbon fixation compared with the treatments (Fig. 6A). The CHCl3 control significantly enriched the number of sequence reads assigned to nitrite-reducing bacteria compared with the controls and treatments (Fig. 6B). On the contrary, CHCl3 control with nothing added significantly reduced the number of sequence reads assigned to atrazine metabolism, whereas EtoAc and water fractions significantly increased the number of sequence reads compared with other controls and treatments (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 5.

Taxonomic to phenotypic mapping based on the biotic habitat. Graph illustrates the number of sequence reads present in the controls and treatments. Symbiotic bacteria (A) and free-living bacteria (B) are shown. The bars with different letters are significantly different (p value < 0.05) from one another.

FIGURE 6.

Taxonomic to phenotypic mapping based on the metabolism of specific microbial groups. The graph illustrates the number of sequence reads present in the controls and treatments. Carbon fixation (A), nitrite reducing (B), and atrazine degradation (C) are shown. The bars with different letters are significantly different (p value < 0.05) from one another.

Correlation Analyses between Compounds and Soil Microbes

We performed correlation analyses to determine the relationship between the abundances of sequences at phyla and OTU levels with each category of compounds detected in the root exudate fractions. Initially, the correlation analyses of these broad groups of compounds (sugars, sugar alcohols, amino acids, and phenolics) at the phyla level revealed that the majority of phenolics and related compounds showed positive correlation with the phyla Cyanobacteria and were negatively correlated with the phyla Actinobacteria, Chlorobi, Fibrobacteres, and Candidate division TM6 (Table 3; supplemental Table S5). Other groups of compounds (sugars, sugar alcohols, and amino acids) showed correlation with all 21 phyla at various levels. Interestingly, the majority of compounds related to phenolics, sugars, sugar alcohols, and amino acids did not show correlation with the phyla Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes. The majority of compounds related to amino acids and phenolics showed negative correlation with the phyla Actinobacteria.

TABLE 3.

Pearson correlation analyses of the groups of compounds identified by GC-MS with the pyrosequencing data classified at phyla level

The numbers represented are significant at p value 0.05. + indicates positive correlation. − indicates negative correlation.

| Sugars |

Amino acids |

Sugar alcohols |

Phenolics |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | |

| Actinobacteria | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| Bacteriodetes | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Proteobacteria | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Acidobacteria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| BD1–5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Candidate division BRC1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Candidate division OP10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Candidate division TM6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 10 |

| Candidate division TM7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Candidate division WSB | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chlorobi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 10 |

| Chloroflexi | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cyanobacteria | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Fibrobacteres | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| Firmicutes | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gemmatimonadetes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nitrospirae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| planctomycetes | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Verrucomicrobia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| WCHB1-60 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unclassified | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

We also determined the number of OTUs that were significantly (positively and negatively) correlated with each group of compounds. We found that phenolics showed the highest number of OTUs (966) followed by amino acids (389), sugars (206), and sugar alcohols (205) (Table 4). Furthermore, we calculated the number of OTUs positively correlated with each group of compounds and found that phenolics (742) showed the highest number of OTUs positively correlated followed by amino acids (319), sugar alcohols (166), and sugars (161). In addition, we determined the number of OTUs that did not significantly correlate with any group of compounds and the OTUs that uniquely showed significant positive correlation with each group of compounds. For instance, 20 OTUs significantly positively correlated with phenolics followed by nine OTUs with amino acids, two OTUs with sugars, and one OTU with sugar alcohols. On the other hand, there are 20 OTUs that are not correlated with any group of compounds analyzed in this study.

TABLE 4.

Pearson correlation analyses of the groups of compounds with OTUs at genus level

The numbers represented are significant at p value 0.05.

| Compounds group | Total number of OTUs correlated | Number of OTUs positively correlated | Number of OTUs negatively correlated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sugars | 206 | 161 | 45 |

| Amino acids | 389 | 319 | 70 |

| Sugar alcohols | 205 | 166 | 39 |

| Phenolics | 966 | 742 | 224 |

Furthermore, we analyzed the correlations at the individual compound level and observed that four compounds (cellobiotol, urea, citramalic acid, and 4-hydroxybenzoate) significantly correlated with a higher number of OTUs (50) including species of Burkholderia, Variovorax, Pseudomonas, Pseudocardineae, Frankineae, Skermanella, and some unclassified. Similarly, two sugars (glucose and fructose) were significantly positively correlated with 28 OTUs including species of Bacillus, Methylobacterium, Sphingomonas, Propionibacterineae, Variovorax, Nitrobacter, Pseudomonas, and some unclassified (supplemental Table S6). Based on these analyses, it is clear that one compound can culture many different OTUs and that a mixture of compounds can synergistically culture groups of OTUs. Besides these two scenarios, we also observed that a single compound showed both positive and negative correlation with some OTUs. For example, isoleucine shows a significant positive correlation with one OTU (Propionibacterineae) and significantly negatively correlates with a different OTU (unclassified). Similarly, azelaic acid shows a significant positive correlation with one OTU (unclassified), whereas it significantly negatively correlates with a different OTU (Kineosporiineae). On the other hand, some compounds such as salicylic acid, ferulic acid, and GABA showed significant positive and negative correlation with many OTUs. For instance, salicylic acid positively correlated with three OTUs (Corynebacterineae, Streptomycineae, and Pseudonocardineae) and negatively correlated with four OTUs (Nitrobacter and three unclassified). Similarly, GABA showed significant positive correlation with 18 OTUs (species of Propionibacterineae, Micromonosporineae, Methylobacterium, Sphingomonas, Frankineae, Variovorax, and unclassified) and negatively correlated with three OTUs (species of Bacillus, Streptomycineae, and unclassified). This suggests that the same compound could act as a positive regulator for some OTUs while also acting as a negative regulator for other OTUs.

DISCUSSION

Plant root-secreted phytochemicals mediate a number of rhizospheric interactions, and these can vary from neutral to beneficial to deleterious interactions (7, 43–47). The majority of these findings were demonstrated under highly controlled conditions in such a way that a specific compound could attract or deter a specific microbe. However, in nature, plants tend to release an array of compounds that interact with a community of rhizospheric microbes. It has been proposed that root exudates among other factors such as the creation of microenvironments by roots (i.e. by soil fertility or modification of soil structure and chemistry) and plant genotype characteristics allow the culturing of rhizosphere-specific microbiomes (48–51). Therefore, in this study we removed all plant/root-associated characteristics to study the effect of different components of root exudates on the soil microbial composition.

We collected root exudates from plants that were 18–21 days old because it has been previously shown that at this time point (that corresponds to bolting) Arabidopsis plants secrete the largest number of phytochemicals (18–21). Furthermore, our previous studies clearly demonstrated that the root exudate profiles collected from individual grown plants at this time point were very consistent and reproducible (28–31). Based on that information, in the present study we pooled the root exudates collected from 600 individual plants for further extraction studies. It is also worth mentioning that Arabidopsis secretes different blends of phytochemicals at distinct developmental stages (67). Therefore, it is likely that root exudates collected at other time points when applied to the soil might create different microbial scenarios. Keeping in mind this situation, we artificially separated and extracted the root exudates of 18–21-day-old plants and when applied to the soil observed significant differences between the controls and treatments with regard to carbon fixation, where carbon fixation significantly increased in the treatments (Fig. 6A). This observation suggests that the root-secreted phytochemicals impact soil microbial activity (52) by utilizing the compounds present in the treatments. In addition, we also observed specific OTUs uniquely present in each fraction. Overall, we observed that the controls shared more OTUs (138) than the treatments (11), suggesting that the treatments culture more specific microbes upon the quantitative distribution of compounds present in a given fraction (Fig. 4). A higher number of unique OTUs were observed in the EtoAc fraction (32) and water fraction (25) compared with the CHCl3 fraction, whole exudates, and controls. This is probably due to the higher percentage of phenolics present in the EtoAc fraction. EtoAc fraction has higher percentage of phenolic-related compounds than sugars, amino acids, and sugar alcohols. However, when compared with the water fraction, the EtoAc fraction had less percentage of amino acids that act as substrates (carbon and nitrogen source) for the majority of microbes. Conversely, the EtoAc fraction (having more phenolics and less sugars) had a significant increase in symbiotic bacteria than other fractions (Fig. 5A). Symbiotic bacteria usually interact with plants through specific signals such as legume flavonoids that induce nod factors in Rhizobia (21), although we did not identify flavonoids because of the limitation of the GC-MS analyses.

Plant roots attract microbes through the release of cues in which carbohydrates and amino acids predominantly act as chemo-attractants (6). In contrast, secondary metabolites such as flavonoids act as chemo-attractants to draw Rhizobia to the root surface regulating nod gene expression (9), and root-secreted malic acid is involved in recruiting the plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus subtilis to the rhizosphere upon infection with foliar pathogens (19). However, for the most part secondary metabolites are considered antimicrobial compounds (53, 54). We performed correlation analyses to determine the relationship between the compounds added to the soil and the subsequent microbes being influenced by these compounds. The correlation analyses revealed that the phenolic compounds showed significant correlation with most OTUs (966); among those, 742 OTUs were positively correlated, and 224 OTUs were negatively correlated compared with the other groups of compounds (sugars, sugar alcohols, and amino acids). These data clearly suggest that phenolic compounds play a major role in attracting microbes. However, it is unclear if these phenolics accomplish this function by acting as attractants, signaling molecules, or specific substrates.

Furthermore, we analyzed the number of OTUs showing a positive correlation to a particular group of compounds, and this revealed that phenolics significantly correlated with 31 OTUs (species of Rhizobium, Bacillus, Sphingomonas, Streptomycineae, Pseudonocardineae, etc.) followed by amino acids with nine OTUs, sugars with two OTUs, and sugar alcohols with one OTU. These data suggest that sugars, amino acids, and sugar alcohols act as general attractants to a broad range of microbes, but the phenolic compounds act as specific substrates or signaling molecules for a specific microbe(s). Two sugars (glucose and fructose) positively correlated with 28 OTUs, reinforcing the statement that sugars act as general chemo-attractants. It should be noted that the values of glucose supplied to the soil at a given application ranged from 10 to 95 nmol depending on the fraction. These quantities are comparable (or even lower) to previous studies that applied glucose to the soil to measure its effects on soil microbes (55, 56).

Root-secreting compounds could act as stimulators for certain microbes while also acting as deterrents for other microbes. For instance, the compound canavanine secreted from the seed coat or roots of leguminous plants acts as an antimicrobial for many rhizosphere bacteria but not for Rhizobia, suggesting that the host plant secretes this compound for selection of the beneficial Rhizobia (13). In the present study we observed a few compounds such as GABA, ferulic acid, salicylic acid, idonic acid, and isoleucine that show a positive correlation with some OTUs while also being negatively correlated with other OTUs. For example, GABA showed a positive correlation with certain OTUs (species of Sphingomonas, Methylobacterium, Frankineae, Variovorax, Micromonosporineae, Skermanella, and unclassified) but negatively correlated with other OTUs (species of Bacillus and Streptomycineae). Accordingly, GABA has been reported to have multiple functions. For example, it acts as a carbon and nitrogen source for a wide variety of microbes (57), and it specifically reduces Agrobacterium quorum sensing ability (58). Interestingly, we did not observe any OTUs assigned to Agrobacterium in our studies.

Similarly, salicylic acid showed a positive correlation with certain OTUs (species of Corynebacterineae, Pseudonocardineae and Streptomycineae). Both salicylic acid and GABA showed positive correlation with OTUs belonging to the group of endophytic Actinobacteria (Pseudonocardineae, Corynebacterineae, Streptomycineae, Frankineae, and Micromonosporineae), which are known to promote plant growth and reduce the disease symptoms caused by plant pathogens through various mechanisms (59–61). Therefore, the ability of salicylic acid and GABA to attract beneficial microbes should be explored in detail. Similarly, the species of Variovorax and Methylobacterium, whose presence was correlated with GABA, are reported to produce ACC deaminase, which helps to alleviate the impact of both biotic and abiotic stresses (62). It should be noted that the amount of salicylic acid applied in the different treatments (15–62 nmol) in the present study is lower than the usual concentrations of salicylic acid used in bioactivity studies (63, 64). This suggests that the soil microbiome might be very sensitive to this signaling molecule.

Here, we demonstrated the effect of different groups of natural compounds derived from plant root exudates on soil microbial composition. Based on our analyses, we formulated three scenarios: 1) one compound can culture different OTUs, 2) mixtures of compounds synergistically culture groups of OTUs, and 3) the same compound can act as a stimulator or deterrent to a group or groups of OTUs. Furthermore, our correlation analyses revealed that the phyla Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes recently determined to be part of the Arabidopsis core microbiome (22, 23) did not show any correlation with the groups of compounds (i.e. sugars, sugar alcohols, amino acids, and phenolics) present in the root exudates. This suggests that the components present in the root exudates are not necessary for culturing these two core microbiome groups. This finding is supported by the fact that these groups of microbes are widely present in a variety of dissimilar soil types, some of them supporting plants while others do not support vegetation (24–27, 65, 66).

We have provided a glimpse of how the natural chemical diversity of compounds present in the root exudates (excluding the plant) could affect the soil microbial composition. Further studies are warranted to include additional natural mixes of compounds present in the root exudates at different stages of development so extensive correlations with OTUs could be accomplished. Additionally, this study provides some level of mechanistic understanding of the microbiome by employing a webserver tool METAGENassist where microbial functions are assigned based on taxonomic (16 S pyrosequencing) data. However, we believe that the only way to provide a functional understanding of the microbiome is by performing metatranscriptomics analysis. Yet, our taxonomic to phenotypic mapping analysis via the use of METAGENassist does provide a starting point and hints at the potential roles of the soil microbiome. In summary, these studies hold the promise to develop natural mixes of compounds that could influence plant-microbiome interactions to increase crop yield and sustainability.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Daniel Manter, United States Department of Agriculture-Agriculture Research Service, Soil Plant Nutrient Research Unit, Fort Collins, CO for providing resources to extract soil DNA and supplying primers for amplifying the 16 S amplicon for pyrosequencing analyses.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0950857 (to J. M. V.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S6 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- OTU

- operational taxonomic unit.

REFERENCES

- 1. Berendsen R. L., Pieterse C. M., Bakker P. A. (2012) The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 478–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hartmann A., Schmid M., van Tuinen D., Berg G. (2009) Plant-driven selection of microbes. Plant Soil 321, 235–257 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Broeckling C. D., Broz A. K., Bergelson J., Manter D. K., Vivanco J. M. (2008) Root exudates regulate soil fungal community composition and diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 738–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Badri D. V., Vivanco J. M. (2009) Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 666–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chaparro J., Sheflin A., Manter D., Vivanco J. (2012) Manipulating the soil microbiome to increase soil health and plant fertility. Biol. Fertil. Soil 48, 489–499 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Somers E., Vanderleyden J., Srinivasan M. (2004) Rhizosphere bacterial signalling. A love parade beneath our feet. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 30, 205–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doornbos R. F., van Loon L. C., Bakker P. (2012) Impact of root exudates and plant defense signaling on bacterial communities in the rhizosphere. A review. Agron. Sustain Dev. 32, 227–243 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neal A. L., Ahmad S., Gordon-Weeks R., Ton J. (2012) Benzoxazinoids in root exudates of maize attract Pseudomonas putida to the rhizosphere. PLoS ONE 7, e35498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abdel-Lateif K., Bogusz D., Hocher V. (2012) The role of flavonoids in the establishment of plant roots endosymbioses with arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi, Rhizobia, and Frankia bacteria. Plant Signal Behav. 7, 636–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bakker M. G., Manter D. K., Sheflin A. M., Weir T. L., Vivanco J. M. (2012) Harnessing the rhizosphere microbiome through plant breeding and agricultural management. Plant Soil 360, 1–13 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Broughton W. J., Zhang F., Perret X., Staehelin C. (2003) Signals exchanged between legumes and Rhizobium. Agricultural uses and perspectives. Plant Soil 252, 129–137 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Omrane S., Chiurazzi M. (2009) A variety of regulatory mechanisms are involved in the nitrogen-dependent modulation of the nodule organogenesis program in legume roots. Plant Signal Behav. 4, 1066–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cai T., Cai W., Zhang J., Zheng H., Tsou A. M., Xiao L., Zhong Z., Zhu J. (2009) Host legume-exuded antimetabolites optimize the symbiotic rhizosphere. Mol. Microbiol. 73, 507–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yoneyama K., Xie X., Sekimoto H., Takeuchi Y., Ogasawara S., Akiyama K., Hayashi H., Yoneyama K. (2008) Strigolactones, host recognition signals for root parasitic plants, and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi from Fabaceae plants. New Phytol. 179, 484–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akiyama K., Matsuzaki K., Hayashi H. (2005) Plant sesquiterpenes induce hyphal branching in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Nature 435, 824–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Weert S., Vermeiren H., Mulders I. H., Kuiper I., Hendrickx N., Bloemberg G. V., Vanderleyden J., De Mot R., Lugtenberg B. J. (2002) Flagella-driven chemotaxis towards exudate components is an important trait for tomato root colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 15, 1173–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gupta Sood S. (2003) Chemotactic response of plant-growth-promoting bacteria towards roots of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal tomato plants. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 45, 219–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Behera B., Wagner G. H. (1974) Microbial growth rate in glucose-amended soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 38, 591–594 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rudrappa T., Czymmek K. J., Paré P. W., Bais H. P. (2008) Root-secreted malic acid recruits beneficial soil bacteria. Plant Physiol. 148, 1547–1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steinkellner S., Lendzemo V., Langer I., Schweiger P., Khaosaad T., Toussaint J.-P., Vierheilig H. (2007) Flavonoids and strigolactones in root exudates as signals in symbiotic and pathogenic plant-fungus interactions. Molecules 12, 1290–1306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang J., Subramanian S., Stacey G., Yu O. (2009) Flavones and flavonols play distinct critical roles during nodulation of Medicago truncatula by Sinorhizobium meliloti. Plant J 57, 171–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bulgarelli D., Rott M., Schlaeppi K., Ver Loren van Themaat E., Ahmadinejad N., Assenza F., Rauf P., Huettel B., Reinhardt R., Schmelzer E., Peplies J., Gloeckner F. O., Amann R., Eickhorst T., Schulze-Lefert P. (2012) Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature 488, 91–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lundberg D. S., Lebeis S. L., Paredes S. H., Yourstone S., Gehring J., Malfatti S., Tremblay J., Engelbrektson A., Kunin V., del Rio T. G., Edgar R. C., Eickhorst T., Ley R. E., Hugenholtz P., Tringe S. G., Dangl J. L. (2012) Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome. Nature 488, 86–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Janssen P. H. (2006) Identifying the dominant soil bacterial taxa in libraries of 16 S rRNA and 16 S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1719–1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singh B. K., Munro S., Potts J. M., Millard P. (2007) Influence of grass species and soil type on rhizosphere microbial community structure in grassland soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 36, 147–155 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin Y.-T., Whitman W. B., Coleman D. C., Chiu C.-Y. (2012) Comparison of soil bacterial communities between coastal and inland forests in a subtropical area. Appl. Soil Ecol. 60, 49 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Philippot L., Andersson S. G., Battin T. J., Prosser J. I., Schimel J. P., Whitman W. B., Hallin S. (2010) The ecological coherence of high bacterial taxonomic ranks. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 523–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Badri D. V., Quintana N., El Kassis E. G., Kim H. K., Choi Y. H., Sugiyama A., Verpoorte R., Martinoia E., Manter D. K., Vivanco J. M. (2009) An ABC transporter mutation alters root exudation of phytochemicals that provoke an overhaul of natural soil microbiota. Plant Physiol. 151, 2006–2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Badri D. V., Loyola-Vargas V. M., Broeckling C. D., De-la-Peña C., Jasinski M., Santelia D., Martinoia E., Sumner L. W., Banta L. M., Stermitz F., Vivanco J. M. (2008) Altered profile of secondary metabolites in the root exudates of Arabidopsis ATP-binding cassette transporter mutants. Plant Physiol. 146, 762–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Badri D. V., Chaparro J. M., Manter D. K., Martinoia E., Vivanco J. M. (2012) Influence of ATP binding cassette transporters in root exudation of phytoalexins, signals, and in disease resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 3, 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31. Badri D. V., De-la-Peña C., Lei Z., Manter D. K., Chaparro J. M., Guimarães R. L., Sumner L. W., Vivanco J. M. (2012) Root-secreted metabolites and proteins are involved in the early events of plant-plant recognition prior to competition. PLoS ONE 7, e46640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sana T. R., Fischer S., Wohlgemuth G., Katrekar A., Jung K. H., Ronald P. C., Fiehn O. (2010) Metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis of the rice response to the bacterial blight pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Metabolomics 6, 451–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fiehn O., Wohlgemuth G., Scholz M. (2005) in Data Integration in the Life Sciences, Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Ludascher B., Raschid L. eds), pp. 224–239, Springer-Verlag, Berlin/Heidelberg [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fiehn O., Wohlgemuth G., Scholz M., Kind T., Lee do Y., Lu Y., Moon S., Nikolau B. (2008) Quality control for plant metabolomics. Reporting MSI-compliant studies. Plant J. 53, 691–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li X., Bergelson J., Chapple C. (2010) The Arabidopsis Accession Pna-10 is a naturally occurring sng1 deletion mutant. Mol. Plant 3, 91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schloss P. D., Westcott S. L., Ryabin T., Hall J. R., Hartmann M., Hollister E. B., Lesniewski R. A., Oakley B. B., Parks D. H., Robinson C. J., Sahl J. W., Stres B., Thallinger G. G., Van Horn D. J., Weber C. F. (2009) Introducing mother. Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7537–7541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Quince C., Lanzen A., Davenport R. J., Turnbaugh P. J. (2011) Removing noise from pyrosequenced amplicons. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pruesse E., Quast C., Knittel K., Fuchs B. M., Ludwig W., Peplies J., Glöckner F. O. (2007) SILVA. A comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 7188–7196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Edgar R. C., Haas B. J., Clemente J. C., Quince C., Knight R. (2011) UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang Q., Garrity G. M., Tiedje J. M., Cole J. R. (2007) Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261–5267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arndt D., Xia J., Liu Y., Zhou Y., Guo A. C., Cruz J. A., Sinelnikov I., Budwill K., Nesbø C. L., Wishart D. S. (2012) METAGENassist. A comprehensive web server for comparative metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W88–W95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Speed T. P. (2003) Statistical Analysis of Gene Expression Microarray Data, p. 222, CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 43. Walker T. S., Bais H. P., Grotewold E., Vivanco J. M. (2003) Root exudation and rhizosphere biology. Plant Physiol. 132, 44–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bais H. P., Park S. W., Weir T. L., Callaway R. M., Vivanco J. M. (2004) How plants communicate using the underground information superhighway. Trends Plant Sci. 9, 26–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Badri D. V., Weir T. L., van der Lelie D., Vivanco J. M. (2009) Rhizosphere chemical dialogues. Plant-microbe interactions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 642–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mercado-Blanco J., Bakker P. A. (2007) Interactions between plants and beneficial Pseudomonas spp. Exploiting bacterial traits for crop protection. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 92, 367–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Raaijmakers J. M., Paulitz T. C., Steinberg C., Alabouvette C., Moenne-Loccoz Y. (2009) The rhizosphere. A playground and battlefield for soilborne pathogens and beneficial microorganisms. Plant Soil 321, 341–361 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Micallef S. A., Shiaris M. P., Colón-Carmona A. (2009) Influence of Arabidopsis thaliana accessions on rhizobacterial communities and natural variation in root exudates. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 1729–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Micallef S. A., Channer S., Shiaris M. P., Colón-Carmona A. (2009) Plant age and genotype impact the progression of bacterial community succession in the Arabidopsis rhizosphere. Plant Signal. Behav. 4, 777–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Berg G., Smalla K. (2009) Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dennis P. G., Miller A. J., Hirsch P. R. (2010) Are root exudates more important than other sources of rhizodeposits in structuring rhizosphere bacterial communities? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 72, 313–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen G., Zhu H., Zhang Y. (2003) Soil microbial activities and carbon and nitrogen fixation. Res. Microbiol. 154, 393–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dixon R. A. (2001) Natural products and plant disease resistance. Nature 411, 843–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wallace R. J. (2004) Antimicrobial properties of plant secondary metabolites. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 63, 621–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Baudoin E., Benizri E., Guckert A. (2003) Impact of artificial root exudates on the bacterial community structure in bulk soil and maize rhizosphere. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35, 1183 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Eilers K. G., Lauber C. L., Knight R., Fierer N. (2010) Shifts in bacterial community structure associated with inputs of low molecular weight carbon compounds to soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 896 [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hosie A. H., Allaway D., Galloway C. S., Dunsby H. A., Poole P. S. (2002) Rhizobium leguminosarum has a second general amino acid permease with unusually broad substrate specificity and high similarity to branched chain amino acid transporters (Bra/LIV) of the ABC family. J. Bacteriol. 184, 4071–4080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chevrot R., Rosen R., Haudecoeur E., Cirou A., Shelp B. J., Ron E., Faure D. (2006) GABA controls the level of quorum-sensing signal in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7460–7464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Qin S., Li J., Chen H. H., Zhao G. Z., Zhu W. Y., Jiang C. L., Xu L. H., Li W. J. (2009) Isolation, diversity, and antimicrobial activity of rare Actinobacteria from medicinal plants of tropical rain forests in Xishuangbanna, China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 6176–6186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Conn V. M., Walker A. R., Franco C. M. (2008) Endophytic Actinobacteria induce defense pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21, 208–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Castillo U. F., Browne L., Strobel G., Hess W. M., Ezra S., Pacheco G., Ezra D. (2007) Biologically active endophytic streptomycetes from Nothofagus spp. and other plants in Patagonia. Microb. Ecol. 53, 12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Saleem M., Arshad M., Hussain S., Bhatti A. S. (2007) Perspective of plant growth promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) containing ACC deaminase in stress agriculture. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 34, 635–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Badri D. V., Loyola-Vargas V. M., Du J., Stermitz F. R., Broeckling C. D., Iglesias-Andreu L., Vivanco J. M. (2008) Transcriptome analysis of Arabidopsis roots treated with signaling compounds. A focus on signal transduction, metabolic regulation, and secretion. New Phytol. 179, 209–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Prithiviraj B., Bais H. P., Weir T., Suresh B., Najarro E. H., Dayakar B. V., Schweizer H. P., Vivanco J. M. (2005) Down-regulation of virulence factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by salicylic acid attenuates its virulence on Arabidopsis thaliana and Caenorhabditis elegans. Infect. Immun. 73, 5319–5328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nemergut D. R., Costello E. K., Hamady M., Lozupone C., Jiang L., Schmidt S. K., Fierer N., Townsend A. R., Cleveland C. C., Stanish L., Knight R. (2011) Global patterns in the biogeography of bacterial taxa. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 135–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Barberán A., Bates S. T., Casamayor E. O., Fierer N. (2012) Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J. 6, 343–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chaparro J. M., Badri D. V., Bakker M. G., Sugiyama A., Manter D. K., Vivanco J. M. (2013) Root exudation of phytochemicals in Arabidopsis follows specific patterns that are developmentally programmed and correlate with soil microbial functions. PLoS ONE 10.1371/journal.pone.0055731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]