Background: Members of the p53 protein family bind to full-site response elements (REs) to trigger specific cellular pathways.

Results: We solved two crystal structures of the p73 DNA-binding domain in complex with full-site REs.

Conclusion: Lys-138 in loop L1 distinguishes between consensus REs.

Significance: Conformational changes in Lys-138 might explain specificity between cell arrest and apoptosis target genes.

Keywords: p53, p63, p73, Transcription Factors, X-ray Crystallography, Response Element, Transactivation

Abstract

How cells choose between developmental pathways remains a fundamental biological question. In the case of the p53 protein family, its three transcription factors (p73, p63, and p53) each trigger a gene expression pattern that leads to specific cellular pathways. At the same time, these transcription factors recognize the same response element (RE) consensus sequences, and their transactivation of target genes overlaps. We aimed to understand target gene selectivity at the molecular level by determining the crystal structures of the p73 DNA-binding domain (DBD) in complex with full-site REs that vary in sequence. We report two structures of the p73 DBD bound as a tetramer to 20-bp full-site REs based on two distinct quarter-sites: GAACA and GAACC. Our study confirms that the DNA-binding residues are conserved within the p53 family, whereas the dimerization and tetramerization interfaces diverge. Moreover, a conserved lysine residue in loop L1 of the DBD senses the presence of guanines in positions 2 and 3 of the quarter-site RE, whereas a conserved arginine in loop 3 adapts to changes in position 5. Sequence variations in the RE elicit a p73 conformational response that might explain target gene specificity.

Introduction

Differential gene expression is a fundamental biological mechanism that underlies cell differentiation and pathological mechanisms such as cancer. The p53 family of transcription factors, formed by p73, p63, and p53, can activate >100 genes (1, 2). Each member of the family triggers a unique pattern of gene expression. For example, p73 was initially recognized to be involved in brain development and immune system maturation (3, 4), p63 in limb and epithelial growth (5, 6), and p53 in cell arrest (7, 8) and apoptosis (9, 10). After the initial discovery of p73 and p63, transcription activation by the p53 family members has been recognized as a complex network where any combination of the three transcription factors could trigger the expression of some target genes (11, 12). For instance, p73 and p63 have been found to also have a role in tumor suppression by activating DNA repair and apoptosis pathways (13, 14). However, the factors that induce the p53 family members to trigger unique or overlapping transcription patterns are not understood.

The p53 family members share a basic gene structure: an N-terminal transactivation domain, a central DNA-binding domain (DBD),2 and a C-terminal tetramerization domain (15). The longer C terminus in both p73 and p63 includes a SAM (sterile alpha motif) domain, which is absent in the shorter positively charged p53 C terminus. The DBD is a 200-amino acid immunoglobulin-like domain with two β-sheets packed as a β-sandwich (16). Several structures of the members of the p53 transcription factor family in complex with DNA have been solved (17–27). The DBD binds as a tetramer to response elements (REs), with each monomer recognizing a 5-bp quarter-site of the 20-bp full-site RE. A full-site RE has two half-site REs, where each half-site follows the 5′-PuPuPuC(A/T)(A/T)GPyPyPy-3′ consensus sequence, and in some cases, both half-sites can be separated by 1–3 nucleotides (1). The DBDs of the p53 family members have an amino acid sequence identity of >50% (28). Once the DBD binds to DNA, the N terminus promotes the recruitment of other factors that eventually lead to the transcription of downstream target genes.

This work builds upon our previous structural research on RE spacers that highlights, using oligonucleotides with half-site REs, how the p73 DBD recognizes REs with spacers of 0, 1, 2, and 4 nucleotides between two half-sites (27). In this study, we analyze the oligomerization state and DNA affinity of the p73 DBD upon binding to full-site REs and present two crystal structures of the p73 DBD tetramer bound to continuous 20-bp full-site REs. We compare all of the solved structures of p73 DBD tetramers in complex with different DNA sequences and correlate changes in the RE sequence with changes in the conformation of the protein that could explain p73 target gene selectivity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression, Purification, and Crystallization

The human p73 DBD (residues 115–312) was purified as described previously (27). Commercially purchased 20-bp oligonucleotides were used in crystallization (5′-GAACATGTTCGAACATGTTC-3′ for the GAACA crystals and 5′-GAACCGGTTCGAACCGGTTC-3′ for the GAACC crystals). Prior to crystallization, the p73 DBD (20 mg/ml) was mixed with DNA (6 mg/ml) at a 1:1 molar ratio and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Both protein-DNA complexes were crystallized using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at room temperature. The GAACA crystals grew in 100 mm trihydrated sodium acetate, 100 mm Tris base (pH 9.0), and 18–20% PEG 3350. The GAACC crystals grew in 100 mm trihydrated sodium acetate, 100 mm Bistris propane (pH 7.5), and 12–15% PEG 3350.

Data Collection and Structure Determination

Crystals were frozen in liquid nitrogen using 30% PEG 3350 as a cryoprotectant. Initial crystals that allowed optimization were diffracted at beamline BL7-1 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, allowing optimization. The final data sets were collected at beamline 8.2.2 of the Advanced Light Source at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Crystal data and intensity statistics are given in Table 1. Diffraction data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using HKL2000 (29). In both complexes, the asymmetric unit consists of two p73 DBD molecules (198 amino acids in each molecule) and half of the palindromic 20-bp oligonucleotide used in crystallization (10-bp dsDNA). The calculated VM values are 2.77 Å3/Da for the GAACA crystal and 2.14 Å3/Da for the GAACC crystal, which correspond to solvent contents of 55.6% and 42.3%, respectively. The structures were solved by molecular replacement using Phaser (30). First, we solved the GAACA structure using a p73 DBD dimer with chains A and B from Protein Data Bank 3VD0 Model 1 bound to a modeled 10-bp dsDNA molecule with the sequence 5′-GAACATGTTC-3′ as a search model (27). A unique molecular replacement solution was obtained. The initial solution was refined using rigid body, simulated annealing, and positional refinement in CNS 1.3 (31). Initial refinement yielded a clear electron density for the DNA molecule, and the 10-bp half-site was built 1 bp at a time. Considering the adjacent symmetry-related molecule, a continuous 20-bp DNA is present in the model. Extra steps of positional and individual B-factor refinement were calculated with CNS 1.3 (31). Cycles of manual and then real-space refinement were carried out for the protein, DNA, and waters with the program Coot 0.6.1 (32). The model was verified using composite omit maps as implemented in CNS 1.3 (31). For the GAACC structure, the GAACA dimer with DNA was used as a search model to find a molecular replacement solution. As the crystal diffracted only to 4.0 Å, the structure was refined imposing tight non-crystallographic symmetry constraints between monomers A and B to reduce the number of refined parameters. Initial refinement was carried out using CNS 1.3 (31), followed by TLS refinement with tight non-crystallographic symmetry constraints between the two protein chains using REFMAC 5.0 (33) as implemented in CCP4 (34). The final Rfactor/Rfree statistics are 25.0/27.4 for the GAACA structure and 24.4/30.7 for the GAACC structure. All residues were either in the most favored or additionally allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot as evaluated by the program PROCHECK (35). Refinement and stereochemical quality statistics of the final model are shown in Table 1. The analysis of DNA structural parameters was carried out using the program 3DNA (36). Chimera was used to calculate structural alignments and root mean square deviations (r.m.s.d.) and to generate figures (37).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell. The geometry of the final model was evaluated with PROCHECK (35). PDB, Protein Data Bank; NCS, non-crystallographic symmetry.

| Crystals |

||

|---|---|---|

| GAACA structure (p73 DBD/20-mer) | GAACC structure (p73 DBD/20-mer) | |

| PDB code | 4G82 | 4G83 |

| DNA sequence | 5′-GAACATGTTCGAACATGTTC-3′ | 5′-GAACCGGTTCGAACCGGTTC-3′ |

| Data collection | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Space group | P61 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 175.47, 175.47, 34.31 | 141.71, 96.35, 34.34 |

| α, β, γ | 90°, 90°, 120° | 90°, 90°, 90° |

| Resolution (Å) | 100.0-3.1 (3.21-3.1) | 50.0-4.0 (4.09-4.0) |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 7.0 (33.0) | 13.0 (45.3) |

| I/σI | 16.8 (1.9) | 8.8 (2.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (98.1) | 99.8 (99.0) |

| Redundancy | 8.9 (4.5) | 7.6 (8.0) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 20.0–3.1 | 79.0–4.0 |

| No. of reflections | 11,371 | 4349 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 25.0/27.4 | 24.4/30.7 |

| Molecules in asymmetric unit | ||

| Protein/dsDNA (10 bp) | 2/1 | 2 (NCS)/1 |

| No. of atoms | 3599 | 3507 |

| Protein | 3148 | 3093 (NCS) |

| DNA/Zn2+ ion | 412/2 | 412/2 |

| Water | 37 | 0 |

| B-factors | 77.2 | 109.0 |

| Protein | 78.8 | 112.2 |

| DNA/Zn2+ ion | 65.8/71.0 | 91.9/104.0 |

| Water | 73.2 | |

| r.m.s.d. | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 | 0.03 |

| Bond angles | 1.8° | 3.0° |

| Dihedral angles | 27.3° | 20.9° |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Residues in most favored region | 87.8 | 97.5 |

| Residues in additionally allowed region | 12.2 | 1.5 |

| Residues in generously allowed region | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Residues in disallowed region | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation velocity experiments were performed and analyzed as described previously (27). A fluorescein-labeled dsDNA (5′-6-FAM-GAACATGTTCGAACATGTTC-3′, where 6-FAM is fluorescein amidite) was used. The data collected were analyzed using SEDFIT software to calculate sedimentation coefficient distributions (38).

Fluorescence Anisotropy

For the binding studies, 15 samples were prepared in a total volume of 500 μl containing pure p73 DBD at 1 nm to 8 μm in buffer containing 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm sodium citrate (pH 6.1), 5 mm DTT, and 5 μm ZnCl2 in addition to a constant 10 nm final concentration of 5′-fluorescein-labeled 20-bp oligonucleotide (5′-FAM-GAACATGTTCGAACATGTTC-3′ or 5′-FAM-GAACCGGTTCGAACCGGTTC-3′). Measurements and analysis were carried out as described previously (27).

RESULTS

Crystal Structures of the p73 DBD Tetramer Bound to 20-bp Full-site REs

We solved the structures of the p73 DBD bound as a tetramer to two REs (Fig. 1A). The structure of a p73 DBD tetramer in complex with a 20-bp full-site RE with a 5′-GAACA-3′ quarter-site sequence, hereafter termed the GAACA structure (Protein Data Bank code 4G82), crystallizes in space group P61, and it was solved to a resolution of 3.1 Å (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. 1A). The p73 DBD tetramer structure bound to a 20-bp full-site RE with a 5′-GAACC-3′ quarter-site sequence, hereafter termed the GAACC structure (Protein Data Bank code 4G83), crystallizes in space group P212121, and it was solved to a resolution of 4.0 Å (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S1B). The final maps show electron density for all of the p73 DBD residues and DNA base pairs (supplemental Figs. S2 and S3, A and B). Although both crystals belong to different space groups, they contain a protein dimer and a half-site RE in the asymmetric unit. The adjacent molecule in the crystal, related by translation, completes the p73 DBD tetramer bound to the continuous 20-bp DNA molecule used during crystallization (supplemental Figs. S1 and S3, A and B).

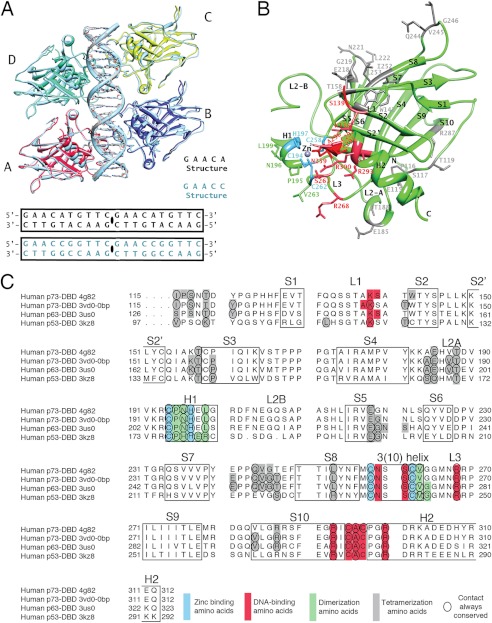

FIGURE 1.

Structures of the p73 DBD tetramer in complex with a full-site RE. A, GAACA and GAACC tetramer structures. Monomers A and B in complex with half of the 20-bp DNAs used for crystallization form the asymmetric unit. Monomers C and D and the other half of the 20-bp DNA are related by translation and are identical to the content of the asymmetric unit. B, p73 DBD monomer. The secondary structure elements are labeled following the established nomenclature for the p53 DBD (17). There are 10 β-strands (S1–S10), two helices (H1 and H2), and three long loops (L1, L2A/L2B, and L3). Residues involved in dimerization (green), tetramerization (gray), zinc binding (blue), and DNA binding (red) are labeled. C, sequence alignment of the DBDs of the three members of the p53 protein family. Amino acids forming the secondary structure elements are boxed. Colored boxes indicate the residues involved in dimerization (green), tetramerization (gray), zinc binding (blue), and DNA binding (red) for four structures that have a similar tetrameric arrangement (4G82 described in this study and 3VD0 Model 1 for the p73 DBD-DNA complex (27), 3US0 for the p63-DNA complex (26), and 3KZ8 for the p53-DNA complex (21)). Residues where the same contact is conserved for all of the monomers of the tetramer are circled.

Structure of the p73 DBD Monomer

The p73 DBD shows the characteristic immunoglobulin-like β-sandwich also present in the DBDs of the other two members of the p53 transcription factor family (p63 and p53). The DBD has a β-sandwich fold with two highly twisted β-sheets, one formed by four strands (S1, S3, S8, and S5) and the other by five strands (S6, S7, S4, S9, and S10) (Fig. 1B). At one end of the β-sandwich, the short loops are compacted, whereas at the other end, two large loops and a large loop-sheet-helix motif are responsible for dimerization and DNA recognition. The two large loops, L2 and L3, contain helices H1 and 310, which form the dimerization interface. The conformation of both loops is maintained by a zinc ion coordinated by Cys-194 and His-197 from helix H1 in loop L2 and Cys-258 and Cys-262 in the 310 helix of loop L3. The larger motif at that end of the β-sandwich is a loop-sheet-helix motif that positions helix H2 to recognize DNA, together with residues in loop L3. The p73 DBD shares 85% and 58% sequence identity and all of the secondary structure elements with the p63 and p53 DBDs, respectively (Fig. 1C).

Due to crystallographic symmetry, there are four unique p73 DBD monomers in the GAACA and GAACC crystals, two in each crystal form. All of the unique monomer structures are still very similar among them, with an r.m.s.d. of 1 or less. For example, only three regions differ significantly between monomers A and B of the GAACA structure. The N terminus, the loop between strands S3 and S4, and the loop between strands S7 and S8 all have significantly higher r.m.s.d. values (1.79, 2.84, and 2.12, respectively) than the rest of the structure. Due to the lower resolution of the GAACC crystal, non-crystallographic symmetry constraints were applied to restrain the monomer structures to each other and decrease the number of parameters to be refined. In summary, the monomer structure is conserved, and its flexibility is limited to individual side chains or few secondary structure elements.

Structure of the p73 DBD Dimer

The ensuing structural description of the p73 DBD dimers and tetramers is simplified because, due to the symmetry present in both crystal forms, monomers A and B are identical to monomers D and C, respectively (Fig. 2A). As a consequence, the dimerization interface between monomers A and B is identical to the one between monomers D and C. Thus, the p73 DBD tetramer bound to a 20-bp full-site RE in both crystals is formed by two identical dimers bound to two identical half-sites.

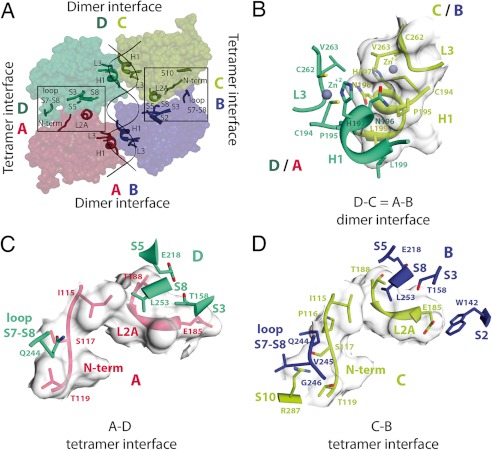

FIGURE 2.

Dimerization and tetramerization interfaces of the p73 DBD tetramer bound to a full-site RE. A, surface area model of the protein tetramer showing the two dimerization interfaces (AB and DC) and the two tetramerization interfaces (AD and CB). B, the DC (green/yellow) and AB (red/blue) dimerization interfaces are identical due to crystal symmetry. The same two secondary structure elements, helix H2 and loop L3, are involved in the DC and AB dimerization interfaces. Three of the four residues that coordinate the zinc ion are displayed (Cys-194, His-197, and Cys-262), together with the four residues involved in the dimerization (Pro-195, Asn-196, Leu-199, and Val-263). C, atomic details of the AD tetramerization interface. Residues in the N terminus and loop L2A of monomer A (red) contact residues in the S7–S8 loop and strands S3, S5, and S8 of monomer D (green). D, atomic details of the CB tetramerization interface. Residues in the N terminus and loop L2A of monomer C (yellow) contact residues in the S7–S8 loop and strands S2, S3, S5, and S8 of monomer B (blue).

The dimerization interface of the p73 DBD tetramer is found ∼13 Å above the main DNA axis, allowing the dimer to embrace the DNA. The interface is formed by three residues located in helix H1 (Pro-195, Asn-196, and Leu-199) and one residue located in the 310 helix found in loop L3 (Val-263) (Fig. 2B). The dimerization interface has a surface area of 225 Å2, and it is formed by two helices, helix H1 from each monomer. It is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions and two hydrogen bonds. The OD1 of Asn-196 in monomer B interacts with the amide nitrogen of Asn-196 in monomer A, and the ND2 of Asn-196 in monomer B interacts with the carbonyl oxygen of Val-263 in monomer A. There are also numerous van der Waals interactions between the carbon atoms of the four residues that stabilize the dimer interface, most notably between the side chains of both Leu-199 residues and the intertwining between the side chains of Pro-195 and Asn-196 from both monomers. The zinc-binding residues in helix H1 and loop L3 are adjacent to the residues involved in dimerization. Thus, the bound zinc atom is essential to maintain the structure that allows dimerization of p73 DBD.

Structure of the p73 DBD Tetramer

As observed in the previously solved structures of the p73 DBD in complex with DNA, the p73 DBD binds as a tetramer to its REs. In this work, we report two structures of the p73 DBD tetramer bound to two distinct 20-bp full-site REs that are continuous DNA molecules. Previous p73 DBD structures had been solved with half-site REs that were only assembled as a full-site RE in the crystal by the stacking of two adjacent DNA molecules (27). The DNA-bound p73 DBD tetramer is stabilized by dimer-dimer contacts formed between two interfaces. The AD tetramerization interface is stabilized by contacts between monomers A and D, and the CB tetramerization interface is maintained through the interaction of monomers C and B (Fig. 2A). The total buried surface area for the tetramerization interface is 979 Å2 for the GAACA structure and 956 Å2 for the GAACC structure. Because of its higher resolution, we focused on the GAACA structure to describe the tetramer interfaces. The CB interface is slightly larger (502 Å2) than the AD interface (442 Å2). There is also a small 33 Å2 contribution to the tetramer buried surface interface from two residues across dimers B and D that are only 4.1 Å apart: Arg-201 from monomer B and Glu-205 from monomer D. Each of the two tetramerization interfaces, AD (Fig. 2C) and CB (Fig. 2D), is stabilized by two patches of atomic contacts. The first patch is formed by residues in the N terminus of monomer A or C that contact the loop between strands S7 and S8 of monomer D or B. The second patch of contacts is between residues in loop L2A from monomer A or C with residues in strands S2, S3, S5, and S8 from monomer D or B. Although both the AD and CB tetramerization interfaces are very similar, mostly conformed by van der Waals interactions, some of the individual contacts between monomers A and D differ from those between monomers C and B. For example, in monomer D, the loop between strands S7 and S8 has moved away and only keeps Gln-244 interacting with the N terminus of monomer A (Fig. 2C). In contrast, in the CB interface, Gln-244, Val-245, and Gly-246 of monomer B interact with the N terminus and Arg-287 of monomer C (Fig. 2D). Another contact, absent in the AD interface, occurs when loop L2A of monomer C interacts with Trp-142 in strand S3 of monomer B. The number of hydrogen bonds in each tetramerization interface is also different: there is only one hydrogen bond in the AD interface (Ser-117 OG in A with Gln-244 OE1 in D), whereas the CB interface has five (Ile-115 oxygen in C with Gln-244 OE1 in B, Ser-117 nitrogen in C with Gln-244 OE1 in B, Ser-117 OG in C with Gln-244 NE2 in B, Glu-185 OE1 in B with Trp-142 NE1 in C, and Arg-287 NH1 in C with Val-245 oxygen in B). Overall, p73 has flexible tetramerization interfaces that adjust to changes in the RE.

DNA Recognition by the p73 DBD

When binding to DNA, hydrodynamic measurements have shown that the p73 DBD forms a tetramer. Sedimentation velocity experiments using a fluorescein-labeled 20-bp RE, identical to the one used for crystallization, showed that the oligomeric arrangement of the p73 DBD forms a tetramer (Fig. 3A), as was previously observed for other RE sequences (27). The DNA binding affinity for the 20-bp full-site REs with GAACA quarter-sites is 3443 nm, practically identical to the 2387 nm affinity measured for the full-site RE with GGGCA quarter-sites (Fig. 3C) (27). The DNA binding constant for the non-canonical RE with GAACC quarter-sites is 10,939 nm, three times lower than for the canonical RE (Fig. 3C).

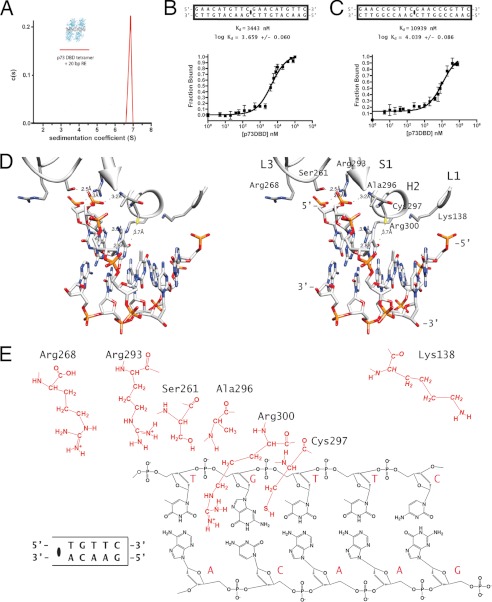

FIGURE 3.

Binding of the p73 DBD to a full-site RE. A, sedimentation coefficient distribution of the p73 DBD bound to a 20-bp DNA containing the same full-site RE used in crystallization experiments obtained in a sedimentation velocity experiment. B, binding affinity constant of the p73 DBD measured by fluorescence anisotropy using fluorescein-labeled DNA for the full-site RE used in crystallization of the GAACA structure. C, binding affinity constant of the p73 DBD measured by fluorescence anisotropy using fluorescein-labeled DNA for the full-site RE used in crystallization of the GAACC structure. D, stereo view of the residues of monomer A from the GAACA crystal structure that have been described as contacting DNA (27). E, schematic diagram of the atomic interactions between the p73 DBD and a quarter-site RE of the GAACA structure.

Regarding the protein-DNA contacts observed in the crystal, the contacts in one half-site RE are identical to those in the second half-site because crystallographic symmetry makes both half-sites identical. In addition, the half-sites are palindromic, making the contacts for each quarter-site in the two crystals almost identical. The p53 protein family uses residues in helix H2 and loops L1 and L3 to recognize DNA (Fig. 3D). Helix H2 and its preceding loop have the majority of p73 DNA-binding residues (Arg-293, Ala-296, Cys-297, and Arg-300). These residues, together with Ser-261 in the 310 helix of loop L3, define the core p73 DNA-binding motif. Ser-261, Arg-293, and Ala-296 contact the DNA backbone, whereas Cys-297 contacts the pyrimidine base in the third position of the quarter-site RE, and Arg-300 contacts the conserved guanine in the fourth position (Fig. 3E). In the GAACA and GAACC structures presented here, as well as in the previously reported p73 DBD structures (27), all of these residues in the core DNA-binding motif conserve the same contacts when bound to DNA.

Besides the constant core DNA-binding motif formed by Ser-261, Arg-293, Ala-296, Cys-297, and Arg-300, the DBD contacts DNA with loops L1 and L3, the conformations of which depend on RE sequence variations. Loop L1 has a conserved lysine (Lys-138) that, when the second and third bases in the quarter-site RE are adenines, moves away from the DNA, as in the GAACA and GAACC structures (Fig. 4, A and B). In this case, Lys-138 does not make any contact with the DNA. Loop L3 also has a conserved residue (Arg-268) that moves away from the minor groove in the GAACC structure and does not contact the backbone phosphate, as in the GAACA structure. Adenine is the most common nucleotide in the fifth position of the quarter-site RE. Notably, when it is replaced by cytosine, there are some differences between the GAACA and GAACC structures. One difference is in loop L3, where the side chain of Arg-268 is farther away from the DNA when cytosine is in the fifth position instead of adenine. Another change is that the GAACC structure has a width of 10.2 Å in the minor groove as measured by the distance between the C1′ carbons of the fifth base pair (supplemental Table S1). Such a distance is closer to the ideal 10.6 Å B-DNA width and is wider than the 9.6 Å width seen in previous p73 DBD-DNA complex structures (27). In both structures, the step twist for the central fifth A-A bases is 24°, instead of the ideal 36° (supplemental Table S2). Nonetheless, the overall DNA conformation in both structures remains close to the ideal B-DNA parameters (supplemental Fig. S3, C and D).

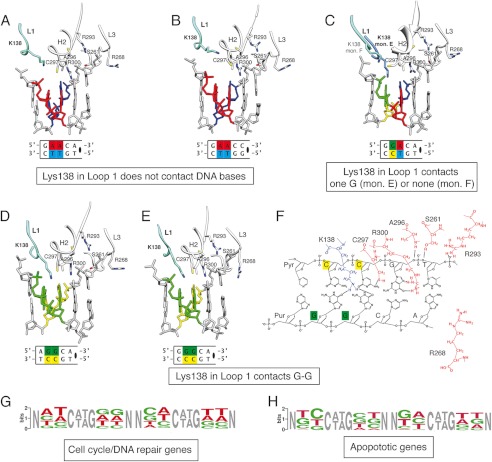

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of the DNA-binding residues of five structures of the p73 DBD in complex with DNA. A and B, residues in the p73 DBD that contact the DNA bases and backbone for the quarter-site REs (5′-GAACA-3′ and 5′-GAACC-3′). Lys-138 in loop L1 is far from the DNA bases and does not contact the DNA. C, residues in the p73 DBD that contact the DNA bases and backbone for the quarter-site RE (5′-GGACA-3′). Lys-138 in loop L1 acquires two conformations. Monomer (mon.) E does not contact the bases; monomer F is far from the DNA bases and does not contact the DNA. D and E, residues in the p73 DBD that contact the DNA bases and backbone for the quarter-site REs (5′-AGGCA-3′ and 5′-GGGCC-3′). In both structures, Lys-138 reaches the DNA bases in the major groove forming two hydrogen bonds with the O2 carbonyl oxygens of the guanines in positions 2 and 3 of the quarter-site RE. F, schematic diagram of the atomic interactions between the p73 DBD and DNA with guanines in positions 2 and 3 of the consensus quarter-site RE. G, WebLogo diagram of positions 2 and 3 of each quarter-site in the 20-bp REs of cell cycle and DNA repair genes found in microarrays to be activated by p73 (39). H, WebLogo diagram of positions 2 and 3 of each quarter-site in the 20-bp REs of apoptotic genes found in microarrays to be activated by p73 (39).

Structural Changes in p73 Residues upon Recognizing Different REs

We compared five crystal structures of the p73 DBD tetramer bound to four consensus sequences (5′-PuPuPuCA-3′) and one non-consensus sequence (5′-GAACC-3′) (Fig. 4). We observed that all of the structures recognize the DNA using the same residues from helix H2 and loop L3 (Ser-261, Arg-268, Arg-293, Cys-295, Ala-296, Cys-297, and Arg-300). These residues constitute the basic DNA-binding motif that explains the micromolar affinity of the p73 DBD for different DNA sequences. Comparatively, residues in loops L1 and L3 have slightly different conformations in the five structures and do not always contact the DNA bases or the phosphate backbone.

Regarding loop L3, due to the 4 Å resolution of the GAACC structure in which the canonical RE sequence changes at the fifth base pair, it is difficult to compare with atomic detail the GAACC structure with the structures bound to canonical RE sequences. Nonetheless, it can be affirmed that the overall arrangement of the tetramer is conserved. The only observed protein change is in loop L3, where Arg-268, which normally approaches the DNA through the minor groove, is farther away (Fig. 4B). Additionally, the DNA in the GAACC structure has a wider minor groove than the DNA in the GAACA structure (supplemental Table S1).

Lys-138 in loop L1 seems to sense the guanine content of the RE sequence. When the second and third bases of the quarter-site RE are guanines, Lys-138 from loop L1 forms two hydrogen bond contacts, one with the O6 keto oxygen of each guanine (Fig. 4, D–F). When only one of the bases in positions 2 and 3 is guanine and the other is adenine, in half of the monomers, Lys-138 makes contacts with the bases, and the other half, Lys-138 does not contact the DNA (Fig. 4C). In the case in which adenines substitute for both guanines in the second and third positions, loop L1 is displaced from the DNA, and Lys-138 does not make direct contact with the bases (Fig. 4, A and B). Interestingly, microarray analysis showed that REs associated with cell arrest and DNA repair genes are more likely to have adenine and thymine in positions 2 and 3 of the quarter-site (Fig. 4G). In contrast, apoptotic REs are more likely to contain guanine and cytosine in the same positions (Fig. 4H). To test the importance of Lys-138, we characterized the DNA binding ability of the p73 DBD K138Q mutant for full-site REs containing the GGGCA and GAACA quarter-site sequences. We observed a drastic drop of at least 100-fold in DNA binding affinity for both sequences (supplemental Fig. S4). In sum, the p73 DBD has a stable core of DNA-binding residues (Ser-261, Arg-293, Ala-296, Cys-297, and Arg-300), plus Lys-138 in loop L1 and Arg-268 in loop L3, that adjust their interactions with DNA depending on the RE sequence.

DISCUSSION

The p53 family of transcription factors triggers the expression of >100 genes that lead cells to diverse pathways (3). Recent experiments revealed that target gene transcription for the three members often overlaps, and the three factors can act as tumor suppressor genes, triggering cell arrest and apoptosis (13, 14). Microarray analysis of gene expression in mouse embryonic fibroblasts identified 620 genes regulated by a member of the p53 transcription family (39). Of this total, 86 genes were regulated at the same time by p73, p63, and p53; 131 genes were uniquely controlled by p73; 58 genes were regulated by p73 and p63; and 41 genes were activated by both p73 and p53. How the p53 family members distinguish between sequences that match the RE consensus sequence but trigger different cellular pathways remains unexplained.

In this work, we studied how the transcription factor p73 recognizes a full-site RE and how it distinguishes between different RE consensus sequences. We have described the oligomerization state, DNA binding affinities, and crystal structures of the p73 DBD bound to two different full-site REs. The data in this study, in conjunction with previous results, show p73 DBD flexible dimerization and tetramerization interfaces and loops L1 and L3 adjusting their conformation to nucleotide changes in the RE sequence. Such structural adjustments might underlie differences in the transactivation level of p73 target genes.

Flexibility in p73 DBD Quaternary Structure

The solved p73 DBD-DNA complex structures show some variation in their dimerization and tetramerization interfaces (Fig. 2). Among all of the previously reported p73 DBD tetramer structures bound to different spacers, the comparisons between the GAACA and GAACC structures and the 0-bp AGGCA structure (Protein Data Bank 3VD0 Model 1) yield the lowest r.m.s.d. (1.25) (supplemental Fig. S5A and Table S3) (27). The total dimerization surface for the GAACA, GAACC, and 0-bp AGGCA structures is between 210 and 225 Å2. Four residues (Pro-195, Asn-196, Leu-199, and Val-263) form the dimerization interface for the two identical dimerization interfaces of the tetramer bound to the 5′-GAACA-3′ sequence (Fig. 2B). Comparatively, in the 0-bp AGGCA structure, one dimerization interface is formed by the same four residues as in the GAACA structure, whereas the second dimer loses the Pro-195 and Val-263 contacts, resulting in an 8° rotation of helix H1. When Lys-138 in loop L1 and Arg-268 in loop L3 contact the DNA, the angle between the H1 helices is broader, and Pro-195 and Val-263 from monomers B and D do not participate in the dimerization interface. Therefore, we suggest that DNA recognition is paired with the angle kept by the dimerization helices. By comparing the structures of the p73 DBD bound to an RE with different sequences, we can begin to understand how DNA recognition affects dimerization.

Once DNA recognition influences dimerization, the quaternary movements of the dimer also lead to changes in the tetramer. The tetramerization interfaces in the p73 DBD are more variable and extended than the dimerization interfaces. The GAACA structure presents two tetramerization interfaces that are distinct from each other and, at the same time, distinct from the interfaces that are observed in the 0-bp AGGCA structure (Fig. 2). There are seven residues that are conserved in the tetramerization interfaces of both structures: Ile-115, Ser-117, Glu-185, and Thr-188 from monomers A and C and Thr-158, Gln-244, and Leu-253 from monomers B and D. Nonetheless, minor changes in the dimerization interface lead to larger movements of some of the secondary structures involved in tetramerization that consequently rearrange some of the interface contacts. The tetramerization buried surface area is larger for the 0-bp AGGCA structure (a total of 1186 Å2, with 561 Å2 for AD, 608 Å2 for CB, and 17 Å2 for BD) than for the GAACA structure (a total of 977 Å2, with 442 Å2 for AD, 502 Å2 for CB, and 33 Å2 for BD) (supplemental Table S3) (27). The main differences are that, in the GAACA structure, residues in loop L2A (Ala-184 and Val-187) and strand S10 (Val-284) of monomers A and C lose contacts with residues in loop L1 (Thr-141) and the loop between strands S7 and S8 (Thr-247) of monomers B and D.

Comparison with Structures of the p53 Transcription Factor Family

Several structures of members of the p53 transcription factor family in complex with DNA have been solved (supplemental Table S3) (17–27). A common denominator of all of the tetramer structures is the arrangement of the tetramer as a dimer of dimers. A 2-fold rotational symmetry axis running perpendicular to the center of the DNA axis relates one dimer with the other, resulting in a C2 molecular symmetry. The structural alignment of all of the solved structures shows that tetrameric arrangements vary broadly (supplemental Table S3).

In comparing the GAACA structure with the structures of its close homolog p63 bound to DNA, we found that the p63 DBD tetramer with a 0-bp spacer (Protein Data Bank code 3US0) has the most similar oligomerization to the GAACA structure. In the 3US0 structure, the asymmetric unit contains a tetramer separated by a 2-bp spacer, but considering a symmetry-related dimer, the p63 DBD forms a 0-bp spacer tetramer that we used for our comparison (supplemental Fig. S5B) (26). The overall r.m.s.d. between the p73 DBD tetramer and the 0-bp spacer p63 DBD tetramer is 2.31 (4G82 versus 3US0 for the 426 atoms within a 5.0 Å distance cutoff), where three of the four monomers superimpose with an r.m.s.d. of 2 or more (supplemental Fig. S5B and Table S3). The 0-bp spacer p63 DBD structure resembles even more the 0-bp p73 DBD structure (3VD0 Model 1), with an overall r.m.s.d. of 0.93 (for the 724 atoms within a 5.0 Å distance cutoff) (27). All of the residues in the oligomerization interfaces are conserved between p73 and p63, except for two residues (Ile-115 and Asn-221) in p73 that become Ser-126 and Ser-232 in the tetramerization interface of p63 (Fig. 1C). In conclusion, the dimerization and tetramerization interfaces of the DBDs of p73 and p63 are almost identical.

Finally, we compared the GAACA tetramer with the p53 DBD tetramer bound to a full-site RE (Protein Data Bank code 3KZ8). This is the p53 DBD tetramer structure with the lowest r.m.s.d. for the two p73 DBD tetramers presented here (supplemental Table S3) (21). Although the p53 DBD tetramer closely superimposes with the GAACA and GAACC structures (supplemental Fig. S5C), p53 has very different dimerization and tetramerization interfaces compared with p73 and p63. The only p73 dimerization residues that are conserved in p53 are Pro-177 and Gly-244. His-178, Arg-181, and Met-243 in p53 replace Asn-196, Leu-199, and Val-263 in p73. Glu-180 in p53 makes a salt bridge contact with Arg-181 of the opposite monomer, but the arginine is absent in p73 and p63. As a result, p53 has a significantly larger dimerization interface (453 Å2/dimer) compared with p73 (210–225 Å2). Regarding the tetramerization interface, the buried surface in p53 is smaller than that in p73 (745 versus 979 Å2). In brief, p53 has conserved the fold and DNA recognition of its homologs p73 and p63, but the dimerization and tetramerization interfaces have diverged.

In summary, the p73, p63, and p53 tetramers discussed here retain a similar quaternary organization (supplemental Fig. S5D) and an identical core DNA recognition motif formed by residues in helix H2 and loop L3 (Ser-261, Arg-268, Arg-293, Cys-295, Ala-296, Cys-297, and Arg-300 in p73 or their conserved equivalent residues in p63 and p53) (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, structural differences could be linked to the ability to form a correct scaffold to bind other transcription factors and influence transactivation activity. For example, in p73, conformational movements of Lys-138 in loop L1 (Lys-149 in p63 or Lys-120 in p53) or Arg-268 in loop L3 (Arg-279 in p63 or Arg-248 in p53) might induce the tetramer to acquire the correct scaffold structure to recruit other factors.

Lys-138 Conformation Switches between Cell Arrest and Apoptotic REs

The most interesting aspect of our work is that the Lys-138 conformation adapts differently to the sequence in positions 2 and 3 of each quarter-site RE (Fig. 4). Moreover, the guanine content in such positions is low for cell arrest and DNA repair genes and high for apoptosis genes, as identified in microarrays assays (Fig. 4, G–H, and supplemental Tables S4 and S5). One can speculate on the role of Lys-138 in determining the target gene specificity of p73. In the case of p53, acetylation of Lys-120 by acetyltransferases of the MYST family has been shown to be important to distinguish between the apoptotic cell response and cell arrest (40, 41). Moreover, biochemically, it has been demonstrated that Lys-120 is important for DNA binding and that its acetylation increases the DNA specificity of p53 (42–44). In the case of p73, Lys-138 (where we observed different conformations depending on the RE sequence) is the conserved equivalent residue of Lys-120 in p53. Considering the importance of Lys-120 acetylation in p53 and the structural differences seen for Lys-138 in p73 DBD-DNA complexes, the existing data suggest that the potential Lys-138 acetylation could influence how p73 distinguishes between REs that trigger different cellular responses. A potential model would require loop L1 to be detached from the DNA to activate transcription, initially favoring transcription of genes with adenines in positions 2 and 3. In the case of apoptotic genes with guanines in positions 2 and 3, which trap loop L1 conformation by binding to Lys-138, lysine acetylation would be required to release loop L1.

Despite extensive research on DNA recognition and target gene specificity of the p53 protein family, fundamental questions about target gene selection remain to be answered. Target gene selectivity is a complex process involving many proteins and steps of regulation. The interaction of transcription factors with REs is only the first step leading to the transcription of a gene. Here, we have provided structural evidence of conformational changes that occur when the p73 DBD distinguishes between closely related REs. Clearly, much work remains to be completed to decipher the structural basis of target gene selectivity.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary crystals were diffracted at beamline BL7-1 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (supported by the United States Department of Energy and National Institutes of Health Grant P41RR001209), and diffraction data were collected at beamline 8.2.2 of the Advanced Light Source at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (supported by Grant DE-AC02-05CH11231 from the Director, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, United States Department of Energy).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5, Tables S1–S5, and additional references.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4G82 and 4G83) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain

- RE

- response element

- Bistris propane

- 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Riley T., Sontag E., Chen P., Levine A. (2008) Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 402–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Menendez D., Inga A., Resnick M. A. (2009) The expanding universe of p53 targets. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 724–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang A., Walker N., Bronson R., Kaghad M., Oosterwegel M., Bonnin J., Vagner C., Bonnet H., Dikkes P., Sharpe A., McKeon F., Caput D. (2000) p73-deficient mice have neurological, pheromonal and inflammatory defects but lack spontaneous tumours. Nature 404, 99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kommagani R., Whitlatch A., Leonard M. K., Kadakia M. P. (2010) p73 is essential for vitamin D-mediated osteoblastic differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 17, 398–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mills A. A., Zheng B., Wang X.-J., Vogel H., Roop D. R., Bradley A. (1999) p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature 398, 708–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang A., Schweitzer R., Sun D., Kaghad M., Walker N., Bronson R. T., Tabin C., Sharpe A., Caput D., Crum C., McKeon F. (1999) p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 398, 714–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scheffner M., Werness B. A., Huibregtse J. M., Levine A. J., Howley P. M. (1990) The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell 63, 1129–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Michalovitz D., Halevy O., Oren M. (1990) Conditional inhibition of transformation and of cell proliferation by a temperature-sensitive mutant of p53. Cell 62, 671–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yonish-Rouach E., Resnitzky D., Lotem J., Sachs L., Kimchi A., Oren M. (1991) Wild-type p53 induces apoptosis of myeloid leukaemic cells that is inhibited by interleukin-6. Nature 352, 345–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shaw P., Bovey R., Tardy S., Sahli R., Sordat B., Costa J. (1992) Induction of apoptosis by wild-type p53 in a human colon tumor-derived cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 4495–4499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levrero M., De Laurenzi V., Costanzo A., Gong J., Wang J. Y., Melino G. (2000) The p53/p63/p73 family of transcription factors: overlapping and distinct functions. J. Cell Sci. 113, 1661–1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang A., Kaghad M., Caput D. (2002) On the shoulders of giants: p63, p73 and the rise of p53. Trends Genet. 18, 90–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flores E. R., Tsai K. Y., Crowley D., Sengupta S., Yang A., McKeon F., Jacks T. (2002) p63 and p73 are required for p53-dependent apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Nature 416, 560–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Flores E. R., Sengupta S., Miller J. B., Newman J. J., Bronson R., Crowley D., Yang A., McKeon F., Jacks T. (2005) Tumor predisposition in mice mutant for p63 and p73: evidence for broader tumor suppressor functions for the p53 family. Cancer Cell 7, 363–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arrowsmith C. H. (1999) Structure and function in the p53 family. Cell Death Differ. 6, 1169–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joerger A. C., Fersht A. R. (2008) Structural biology of the tumor suppressor p53. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 557–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cho Y., Gorina S., Jeffrey P. D., Pavletich N. P. (1994) Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science 265, 346–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitayner M., Rozenberg H., Kessler N., Rabinovich D., Shaulov L., Haran T. E., Shakked Z. (2006) Structural basis of DNA recognition by p53 tetramers. Mol. Cell 22, 741–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ho W. C., Fitzgerald M. X., Marmorstein R. (2006) Structure of the p53 core domain dimer bound to DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 20494–20502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malecka K. A., Ho W. C., Marmorstein R. (2009) Crystal structure of a p53 core tetramer bound to DNA. Oncogene 28, 325–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kitayner M., Rozenberg H., Rohs R., Suad O., Rabinovich D., Honig B., Shakked Z. (2010) Diversity in DNA recognition by p53 revealed by crystal structures with Hoogsteen base pairs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 423–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen Y., Dey R., Chen L. (2010) Crystal structure of the p53 core domain bound to a full consensus site as a self-assembled tetramer. Structure 18, 246–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Petty T. J., Emamzadah S., Costantino L., Petkova I., Stavridi E. S., Saven J. G., Vauthey E., Halazonetis T. D. (2011) An induced fit mechanism regulates p53 DNA binding kinetics to confer sequence specificity. EMBO J. 30, 2167–2176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Emamzadah S., Tropia L., Halazonetis T. D. (2011) Crystal structure of a multidomain human p53 tetramer bound to the natural CDKN1A (p21) p53-response element. Mol. Cancer Res. 9, 1493–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen C., Gorlatova N., Kelman Z., Herzberg O. (2011) Structures of p63 DNA binding domain in complexes with half-site and with spacer-containing full response elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 6456–6461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen C., Gorlatova N., Herzberg O. (2012) Pliable DNA conformation of response elements bound to transcription factor p63. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 7477–7486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ethayathulla A. S., Tse P.-W., Monti P., Nguyen S., Inga A., Fronza G., Viadiu H. (2012) Structure of p73 DNA-binding domain tetramer modulates p73 transactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 6066–6071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Belyi V. A., Ak P., Markert E., Wang H., Hu W., Puzio-Kuter A., Levine A. J. (2010) The origins and evolution of the p53 family of genes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Method Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brunger A. T. (2007) Version 1.2 of the crystallography and NMR system. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2728–2733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Winn M. D., Murshudov G. N., Papiz M. Z. (2003) Macromolecular TLS refinement in REFMAC at moderate resolutions. Methods Enzymol. 374, 300–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., Read R. J., Vagin A., Wilson K. S. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D 67, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lu X.-J., Olson W. K. (2008) 3DNA: a versatile, integrated software system for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic-acid structures. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1213–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schuck P. (2000) Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and Lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 78, 1606–1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lin Y. L., Sengupta S., Gurdziel K., Bell G. W., Jacks T., Flores E. R. (2009) p63 and p73 transcriptionally regulate genes involved in DNA repair. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40. Sykes S. M., Mellert H. S., Holbert M. A., Li K., Marmorstein R., Lane W. S., McMahon S. B. (2006) Acetylation of the p53 DNA-binding domain regulates apoptosis induction. Mol. Cell 24, 841–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tang Y., Luo J., Zhang W., Gu W. (2006) Tip60-dependent acetylation of p53 modulates the decision between cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. Mol. Cell 24, 827–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Luo J., Li M., Tang Y., Laszkowska M., Roeder R. G., Gu W. (2004) Acetylation of p53 augments its site-specific DNA binding both in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 2259–2264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zupnick A., Prives C. (2006) Mutational analysis of the p53 core domain L1 loop. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 20464–20473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arbely E., Natan E., Brandt T., Allen M. D., Veprintsev D. B., Robinson C. V., Chin J. W., Joerger A. C., Fersht A. R. (2011) Acetylation of lysine 120 of p53 endows DNA-binding specificity at effective physiological salt concentration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8251–8256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]