Abstract

Regulation of forebrain cellular structure and function by small GTPase pathways is crucial for normal and pathological brain development and function. Kalirin is a brain-specific activator of Rho-like small GTPases implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders. We have recently demonstrated key roles for kalirin in cortical synaptic transmission, dendrite branching, spine density, and working memory. However, little is known about the impact of the complete absence of kalirin on the hippocampus in mice. We thus investigated hippocampal function, structure, and associated behavioral phenotypes in KALRN knockout (KO) mice we have recently generated. Here we show that KALRN KO mice had modest impairments in hippocampal LTP, but normal hippocampal synaptic transmission. In these mice, both context and cue-dependent fear conditioning were impaired. Spine density and dendrite morphology in hippocampal pyramidal neurons was not significantly affected in the KALRN KO mice, but small alterations in the gross morphology of the hippocampus were detected. These data suggest that hippocampal structure and function are more resilient to the complete loss of kalirin, and reveal impairments in fear learning. These studies allow the comparison of the phenotypes of different kalirin mutant mice and shed light on the brain region-specific functions of small GTPase signaling.

Keywords: GEF, synaptic plasticity, dendrite, dendritic spine, Rac1, knockout, fear conditioning

Introduction

Kalirin is a brain-specific guanine-nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for the Rho family of small GTPases (Johnson et al., 2000; Penzes et al., 2000; Penzes and Jones, 2008). Members of the Rho subfamily of Ras-like small GTPases are central regulators of actin cytoskeletal dynamics in neurons, regulating the development and morphology of dendrites and spines (Nakayama et al., 2000; Nakayama and Luo, 2000; Tashiro et al., 2000; Threadgill et al., 1997; Wong et al., 2000). Their essential role in regulating spine morphology and human cognition, including learning and memory, is supported by the fact that many types of mental retardation (MR) are associated with altered spine morphogenesis. Mutations in genes encoding proteins in the Rho GTPases signaling pathways have also been associated with MR (Dierssen and Ramakers, 2006).

In adult mice, kalirin expression is mainly restricted to the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Ma et al., 2001) and is not detectable outside of the brain. Several alternatively spliced forms are generated from a single KALRN gene. Kalirin-7 is the most abundant isoform in the adult brain, and is enriched in postsynaptic densities (PSD) of dendritic spines where it controls their morphology (Penzes et al., 2000; Penzes et al., 2001b). The less abundant kalirin isoforms, kalirin-9 and kalirin-12, are localized in the soma and in the processes of young neurons (Penzes et al., 2001a). The Rac1 activating GEF1 domain of kalirin is present in all isoforms, while the RhoA-activating GEF2 domain is present only in kalirin-9 and kalirin-12 (Penzes et al., 2001a). While kalirin-9 and -12 are expressed early in postnatal development, kalirin-7 expression is not detectable at birth, and increases after P7-10 (Ma et al., 2003; Xie et al., 2007).

We have shown that in cultured cortical neurons kalirin plays an important role in activity-dependent spine plasticity, synaptic expression and maintenance of AMPA receptors (AMPAR), and AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission (Xie et al., 2007). Kalirin-7 is also required in cortical pyramidal neurons for spine morphogenesis downstream of the trans-synaptic adhesion molecules ephrinB-EphB (Penzes et al., 2003) and N-cadherin (Xie et al., 2008) and 5-HT2A serotonin receptors (Jones et al., 2009). We have recently reported the generation of a KALRN knockout (KALRN KO) mouse, which exhibited impairment in both spine and dendrite morphogenesis in vivo, associated with a working memory deficit (Cahill et al., 2009).

Another recent study examined mice with a deletion of the exon encoding the short C-terminal domain targeting kalirin-7 to spines (Δkalirin-7 mice) (Ma et al., 2008). Interestingly, KALRN KO mice and Δkalirin-7 mutant mice show several phenotypic differences. Notably, Δkalirin-7 mice exhibit a slight reduction in hippocampal spine density, which contrasts with our previous finding that full KALRN knockout affected neither hippocampal Rac1-GTP levels nor hippocampal spine density. KALRN KO mice show a reduction in active Rac1 levels in the cortex, while active Rac1 levels were unaltered in the Δkalirin-7 cortex. Similar to KALRN KO mice, cortical cultures from Δkalirin-7 mice showed a reduced spine density. However, while cortical spine density was reduced in vivo in KALRN KO mice, cortical spine density in vivo in Δkalirin-7 has not been reported. Δkalirin-7 and KALRN KO mice also showed differing behavioral phenotypes. KALRN KO mice showed locomotor hyperactivity and deficits in spatial working memory, both of which were unimpaired in Δkalirin-7 mutants. Contextual fear conditioning was impaired in Δkalirin-7 mice, but has not been analyzed in KALRN KO mice. These findings indicate that the complete absence of kalirin versus the targeted deletion of kalirin-7 produce some non-overlapping deficits. While our previous studies on the KALRN KO mice focused on the cerebral cortex and cortex-associated behavior, hippocampal structure and function has not been analyzed in detail in these mice. On the other hand, the studies on Δkalirin-7 mice focused mainly on the hippocampus. It is thus necessary to further investigate KALRN KO mice to understand these differences.

We therefore set out to investigate in more detail hippocampal function, structure, and associated behavioral phenotypes in KALRN KO mice. These studies will allow a more complete comparison of the phenotypes of KALRN KO and Δ-kalirin-7, and would shed light on the brain region-specific functions of Rho GTPase signaling. Surprisingly, we found that contrary to the Δkalirin-7 mice, KALRN KO mice had only modest impairments in hippocampal LTP, along with normal hippocampal synaptic transmission. However, in these mice, both context and cue-dependent fear conditioning were impaired. Spine density and dendrite morphology in hippocampal pyramidal neurons were not significantly affected in the KALRN KO mice, but small alterations in the gross morphology of the hippocampus were detected. These data reveal important and unexpected differences between different kalirin mutant mice, and suggest that basal hippocampal structure and function are more resilient to the full loss of kalirin.

Materials and methods

Generation of the KALRN KO mice

Design and generation of the KALRN null mice has been described in detail previously (Cahill et al., 2009). Briefly, a targeting construct was designed in which exons 27-28 was replaced by the neo cassette under an independent PGK promoter. The PGK-neo cassette was inserted in reverse orientation and contained a loxP sites at each end to allow for excision. KALRN null mice were generated from ES cells by inGenious Targeting Laboratory (Stony Brook, NY) using standard methods. PCR analysis using WT and KO-specific primers indicated that the KALRN gene was disrupted. No kalirin proteins were detected by Western blotting of brain homogenates.

Fear Conditioning

Training was performed in a cage with a steel grated floor, scented with 70% ethanol, illuminated with a 12V halogen light, and subjected to a constant 68 dB background white noise. 14∼16-week old C57BL/6J KALRN KO and WT littermate mice, 10 each group, were used for behavioral analysis. Mice were individually placed in the cage and allowed to explore for 3 min, then a 30-sec 10 kHz tone was presented, followed by a 2 sec 0.7mA footshock. Animals were then removed from the training context and returned to their home cages until testing. Context and cue-dependent testing were performed 45 min, 24 hrs, and 48 hrs after training. Context conditioning: Animals were exposed to the identical chamber used during training, under the same light, noise, and odor conditions. Animals were allowed free exploration for 3 min while no tone or footshock was administered. Cue conditioning: Five minutes after testing in the context chamber, mice were exposed to a novel context and allowed free exploration for 1 min, followed by 3 min of exploration in conjunction with the presentation of a 10 kHz tone identical to that presented during training (cue); no footshock was administered. Behavioral analysis consisted of measurements of mouse locomotor activity (number of infrared beam breaks) and freezing responses. Freezing was defined as immobility for at least 3 seconds. Data were acquired by TSE Fear Conditioning System (Chesterfield, MO). The same animals were used for both the context conditioning and for the cue conditioning. Statistics were performed using a 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA. Differences between genotypes at different testing points were determined using a Bonferroni post hoc test.

Histology

Brains of 3-month-old male littermate KO and WT mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sagittally sectioned into 4 μm sections. Each littermate pair of KO and WT mice brains was embedded in the same paraffin block, sectioned and processed in parallel. Three pairs of male littermate KO and WT mice brains were analyzed. Staining procedures were carried out according to standard protocols. Nissl staining: sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated, stained in 0.1% cresyl violet for 5 min, quickly rinsed in distilled water and differentiated in ethanol, dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and mounted with Permount. For hippocampal area measurement, four laterally equal spaced Nissl sections 0.6 mm apart from each brain were analyzed: the hippocampal borders were outlined and the areas within the borders were quantified with NIH ImageJ. All measurements and comparisons were made on brain sections of the same sagittal coordination based on the Allen Mouse Brain Reference Atlas.

Golgi staining and neuronal tracing

Golgi staining was performed using modified Golgi-Cox impregnation method. Brains of 3-month-old male littermate KO and WT mice were processed in parallel and stained with a FD Rapid GolgiStain kit (FD NeuroTechnologies, Ellicott City, MD) following the manufacturer's protocol. Images were taken with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope. To analyze dendritic morphology, Golgi-stained pyramidal neurons were manually traced with Neurolucida (MicroBrightField, Williston, VT); total dendritic length and number of dendritic tips (a measure of branching) were measured and quantified using Neurolucida Explorer. Sholl analysis was also performed with Neurolucida Explorer to demonstrate the branching patterns of the neuronal dendritic trees. Briefly, concentric circles with gradually increasing radius centered at the centroid of the cell body were drawn, and the numbers the neuron intersects with the circumferences of these circles were counted and plotted. Three pairs of male WT and KO littermate brains were analyzed. For each brain, two to three CA1 pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus were traced.

Dissociated cultures of hippocampal primary neurons

Primary neuronal cultures were generated from the hippocampus of P1 KALRN KO or WT pups. Hippocampal neurons were cultured in vitro for up to 4 weeks in Neurobasal media supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen), as described previously (Penzes et al., 2003; Xie et al., 2007). To examine dendrite and spine morphologies, at DIV 26, neurons were transfected with a GFP-expressing construct and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instruction. Two days later, cultures were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS containing 10% sucrose for 20 min at room temperature, and immunostained with a GFP monoclonal antibody (Chemicon; 1:1000 dilution).

Immunofluorescence image acquisition and analysis

Visualization and quantification of dendrite and spine morphologies were performed as described in (Xie et al, 2007). Briefly, neurons with healthy, typical pyramidal morphologies were imaged with a Zeiss LSM5 Pascal confocal microscope. Detector gain and offset were adjusted to include all spines, and Z-stacks of images were taken with a 63× objective. The background corresponding to areas without cells were subtracted to generate a “background-subtracted” image. Experiments were done blind to conditions. Cultures that were directly compared were imaged with the same acquisition parameters. An anti-GFP antibody was used to circumvent potential unevenness of GFP diffusion in spines. Neurons with comparable, medium GFP fluorescence intensity were imaged. Individual spines were outlined on reconstructed 2D images and morphological parameters (linear density: number of spines per 10 μm of dendrite) were measured using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). Dendritic morphological parameters (dendritic lengths, number of dendritic tips) were quantified with NIH ImageJ. Nine to twelve cells each group from at least two separate experiments were analyzed.

Hippocampus slice preparation

Animals were sacrificed using a rodent guillotine. The brain was immersed in ice-cold cutting saline (CS; in μM: 110 sucrose, 60 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 28 NaHCO3, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 5 glucose, 0.6 ascorbate) prior to isolation of the caudal portion containing the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Transverse slices (400 μm) were prepared with a Vibratome (The Vibratome Company, St. Louis, MO). During isolation, slices were stored in ice-cold CS. After isolation, cortical tissue was removed and hippocampal slices were equilibrated in a mixture of 50% CS and 50% artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; in μM: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 glucose) at room temperature. Slices were further equilibrated in 100% ACSF for 45 min at room temperature, followed by a final incubation in 100% ACSF at 32 °C for 1 h. All solutions were saturated with 95%/5% O2/CO2.

Slice electrophysiology

Electrophysiology was performed in an interface chamber (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) as described in (Levenson et al., 2004). Oxygenated ACSF (95%/5% O2/CO2) was warmed (30° C, TC-324B temperature controller, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) and perfused into the recording chamber at a rate of 1 mL/min. Electrophysiological traces were amplified (Model 1800 amplifier, A-M Systems, Sequim, WA), digitized and stored (Digidata models 1322A with Clampex software, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Extracellular stimuli were administered (Model 2200 stimulus isolator, A-M Systems) on the border of Area CA3 and CA1 along the Schaffer-collaterals using enameled, bipolar platinum-tungsten (92%:8%) electrodes. fEPSPs were recorded in stratum radiatum with an ACSF-filled glass recording electrode (1-3 MΩ). The relationship between fiber volley and fEPSP slopes over various stimulus intensities (1 mV – 30 mV) was used to assess baseline synaptic transmission. All subsequent experimental stimuli were set to an intensity that evoked a fEPSP that had a slope of 50% of the maximum fEPSP slope. Paired-pulse facilitation was measured at various interstimulus intervals (10, 25, 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300 msec). High-frequency stimulus-induced LTP was induced by administering two 100 Hz tetani (1 sec duration) at an interval of 20 sec. Synaptic efficacy was monitored 20 min prior to and 3 h following induction of LTP by recording fEPSPs every 20 sec (traces were averaged for every 2-min interval). The experimenter performing the electrophysiology was blind to genotype or treatment. Input/output curves were fit using a single exponential equation (Y = TOP × [1 − e−K × X]); TOP and K were compared between treatment groups using an F test. Experiments measuring paired pulse facilitation and LTP were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and t-test for individual time-points.

Statistics

All data represent means ± SEM. Statistical analyses for two group comparison were done with Student's t test; paired t test was used when results from WT and KO littermates were compared. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's multiple-comparison test was used to determine the statistical significance of the differences among multiple groups (GraphPad Prism). Differences were deemed statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Normal basal synaptic transmission along with modest impairment of hippocampal plasticity in KALRN KO mice

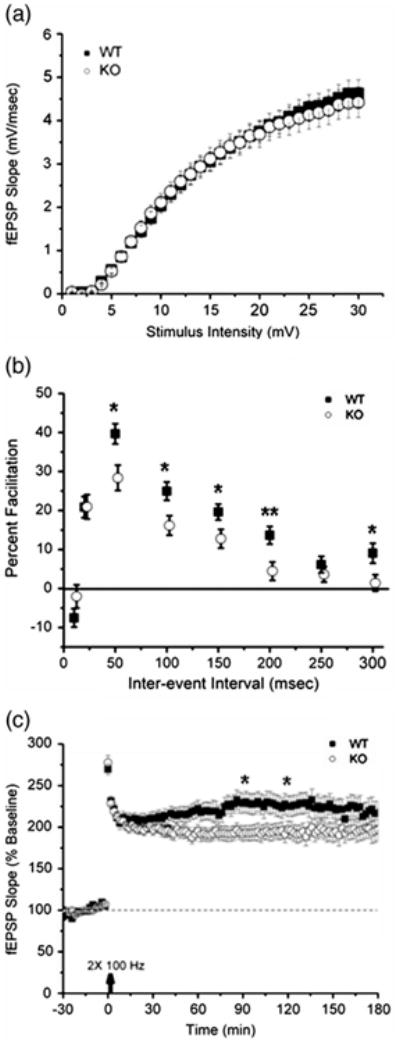

We have previously shown that loss of kalirin results in reduced glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the cortex (Cahill et al., 2009). However, hippocampal function has not been investigated in KALRN KO mice. In addition, Ma et al. have reported impaired hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) in Δ-kalirin-7 mutant mice (Ma et al., 2008). To determine whether homozygous deletion of KALRN had a functional effect on hippocampal synaptic transmission or plasticity thereof, a series of electrophysiological studies were performed on hippocampal Schaffer-collateral synapses. Basal synaptic transmission was determined by plotting the relationship between fEPSP slope, a measure of postsynaptic depolarization, versus fiber volley slope, a measure of presynaptic depolarization, over a range of stimulus intensities (1 – 30 mV, 50 nA – 3.0 uA). KALRN KO animals exhibited no change in basal synaptic transmission relative to WT littermates (Fig. 1a, p>0.05). Tests of paired pulse facilitation indicated that this form of short-term plasticity of neurotransmitter release was diminished in hippocampal slices derived from KALRN KO animals (Fig. 1b, p < 0.05 at the 50, 100, 150, 200, and 300 msec interval time-points), suggesting that insufficiency of kalirin results in normal baseline synaptic transmission and basal excitatory glutamate receptor function, but that presynaptically based short-term plasticity is deficient in the absence of kalirin.

Fig. 1.

Knockout of KALRN is associated with reduced paired-pulse facilitation and modest deficit in the late phase of long-term potentiation. Assays of Schaffer-collateral synaptic function were performed on acute hippocampal slices. (a) Basal synaptic transmission was normal in KALRN KO mice (KO) relative to wild-type (WT) littermates. (b) Paired pulse facilitation was significantly attenuated by absence of kalirin, indicating that short-term plasticity of neurotransmitter release was diminished in KO animals. (c) Induction of LTP using high frequency stimulation revealed a small reduction at some later time points in KALRN KO-derived slices. Arrow indicates time of LTP induction. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

Long-term synaptic plasticity is a fundamental property of many chemical synapses and is the leading candidate cellular mechanism for information storage in the nervous system. Long-term potentiation (LTP) is a form of synaptic plasticity whereby persistent increases in synaptic efficacy result from brief, high frequency synaptic activity. Induction of LTP using two 100Hz tetani (1sec duration, 20sec apart) triggered synaptic potentiation in both kalirin-deficient animals and in wild-type control animals. KALRN KO animals exhibited a modest deficit in LTP at some time points after 1 h (Fig. 1c, p < 0.05 at both the 90-minute and 120-minute time-points). Collectively, these data suggest that insufficiency of kalirin does not affect the processes involved in induction of LTP, but may have an impact on the maintenance of LTP at some later part of the time-course.

Impaired contextual fear conditioning in KALRN KO mice

Since the hippocampus plays an important role in spatial learning, we tested the learning performance of KO and WT mice in a fear conditioning paradigm. Fear conditioning is a form of learning in which a robust and long lasting association between a stimulus and a noxious consequence is rapidly acquired by animals after only one trial (Fanselow, 1990a; Fanselow, 1990b; LeDoux, 2000). This method has been extensively used to study the role of specific genes in learning, and could also be used to examine experience-dependent plasticity (LeDoux, 2000).

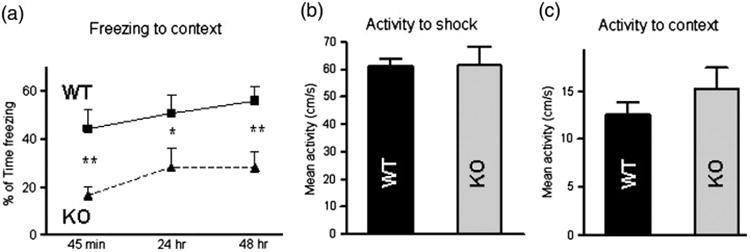

In the contextual fear conditioning paradigm, which depends on both the hippocampus and amygdala, among other brain regions, a context serves as the conditioning stimulus, which is combined with a noxious unconditioned stimulus. Learning the association of the footshock with the context is contextual fear conditioning. Mice were trained to associate a context (cage) with a noxious stimulus (footshock). Fear responses to the context, expressed as freezing, were measured at different time points, including 45 min (memory acquisition), and 24 hrs and 48 hrs (memory consolidation) later. Analyses revealed a significant effect of genotype on freezing behavior (F=23.34) suggestive of an impaired ability of kalirin KO animals to acquire and consolidate new contextual fear memories, compared to WT controls (Fig. 2a). The differences between the WT and KO animals in these tasks were not due to differences in mobility, pain perception or hearing, since WT and KO animals exhibited no difference of locomotor activity in response to footshock presentation (Fig. 2b) and activity in the context chamber during training (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

KALRN KO mice show impaired contextual fear conditioning. (a) Fear response, measured as percentage of time freezing 45 min, 24 hr and 48 hr after foot shock, show the inability of KALRN KO mice to acquire and consolidate new contextual fear memory. There were no differences between WT and KALRN KO mice in animal activity in response to electric shock (b) or the context environment (c). *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

Impaired cued fear conditioning in KALRN KO mice

To further dissect the potential involvement of the hippocampus, we tested mice in the cued fear conditioning paradigm. In this paradigm, a cue (sound) serves as the conditioning stimulus, which is combined with a noxious unconditioned stimulus (footshock). Learning of the association of the sound with the shock is cued fear conditioning. Fear responses to the cue, expressed as freezing, were measured at different time points, including 45 min (memory acquisition), and 24 hrs and 48 hrs (memory consolidation) later. Prior to the cue presentation, animals were allowed free exploration for 1-minute in the absence of any cue (the pre-tone period). Analyses indicated a reduction in freezing to the cue in KO mice relative to WT mice (F=14.49) suggestive of an impaired ability of KALRN KO mice to acquire new cued fear memories as compared to WT controls (Fig. 3a). The ability of KALRN KO mice to consolidate cued fear memories was impaired at 24 hrs but not at 48 hrs, suggesting a latent onset of cued fear memory consolidation in KALRN KO mice. Importantly KO and WT animals exhibited similar activity in response to the tone during training (Fig. 3b). Moreover, both KO and WT mice showed more freezing during exposure to the tone than during the 1-minute pre-tone period indicating that the freezing responses were elicited by the tone and were not due to generalized fear responses triggered by the novel context (Fig. S1A, B).

Fig. 3.

KALRN KO mice show impaired cued fear conditioning. (a) Fear response, measured as percentage of time freezing 45 min, 24 hr and 48 hr after foot shock, show the inability of KALRN KO mice to acquire cued fear memory and latent onset in the ability to consolidate new cued fear memory. (b) There were no differences between WT and KALRN KO mice in animal activity in response to tone stimulus. *, p<0.05

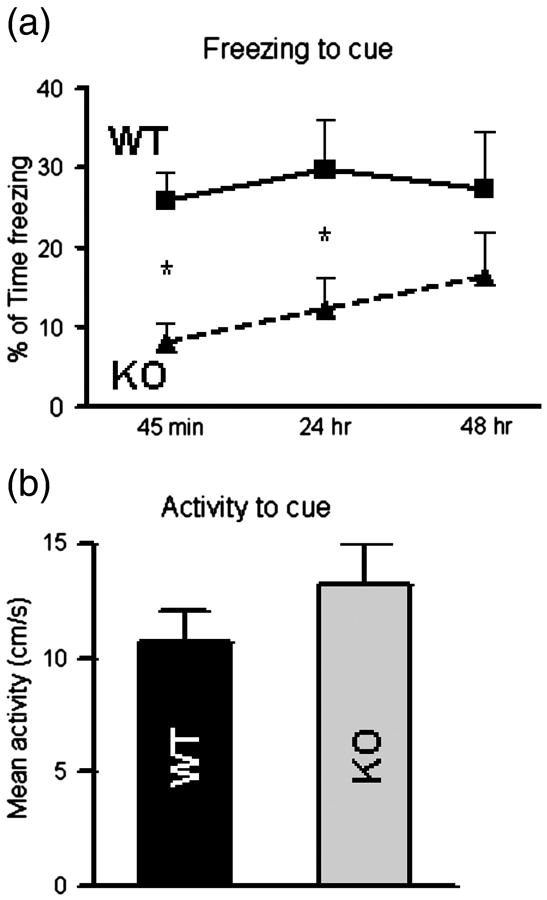

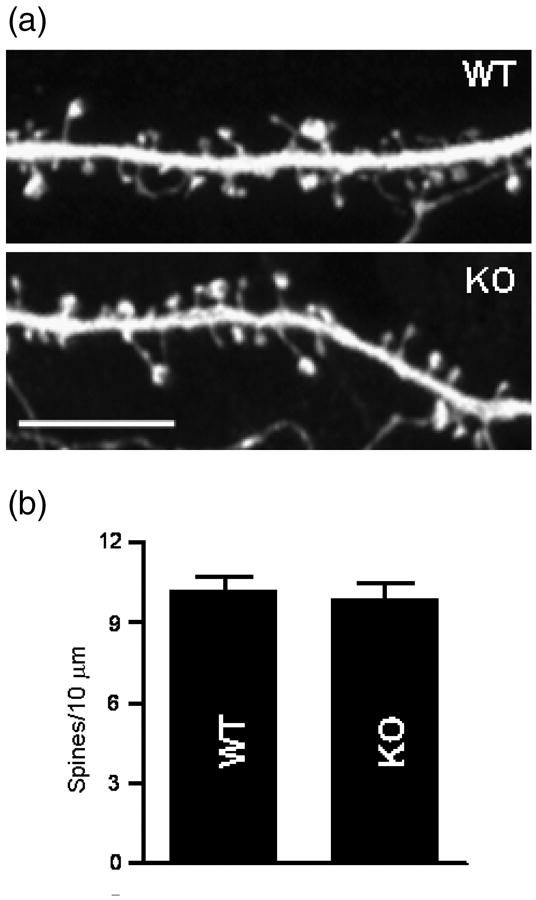

Dendritic spine morphology in cultured hippocampal neurons from KALRN KO mice

Alterations in spine morphology are known to play a role in cognitive functions, including learning and memory (Alvarez and Sabatini, 2007). Dendritic spine growth and maintenance is shaped by Rho family GTPases (Konur and Ghosh, 2005) and their GEFs (Penzes et al., 2001b). We have recently shown using Golgi staining that in KALRN KO mice, cortical spine density was robustly reduced (by 40%), while hippocampal spine density was not altered. On the contrary, Ma et al, 2008 have found a slight but significant reduction in hippocampal spine density (about 15%) in Δkalirin-7 mice. We thus examined dendritic spine density in individual hippocampal neurons from KALRN KO mice. Because analysis of dissociated cultured neurons allows for high-resolution imaging of spines and reveals whether specific phenotypes are cell autonomous, we evaluated spine density in cultures of hippocampal neurons originated from neonatal KO and WT mice and grown for 4 weeks (Penzes et al., 2003). Neurons were transfected with GFP, which allowed high-resolution imaging of spine structures using confocal microscopy. Consistent with our previous Golgi studies, no significant differences in dendritic spine density were detected between the WT and KO hippocampal neurons (Fig. 4a-b; WT 10.20±0.52, KO 9.92± 0.59 spines/10μm, p=0.726).

Fig. 4.

Normal morphology of dendritic spines in cultured hippocampal neurons from KALRN KO mice. (a) Visualization of dendritic spine morphology of cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons (DIV 28) from WT and KALRN KO mice by the expression of GFP. (b) Quantification of dendritic spine linear density. Scale bar: 10 μm.

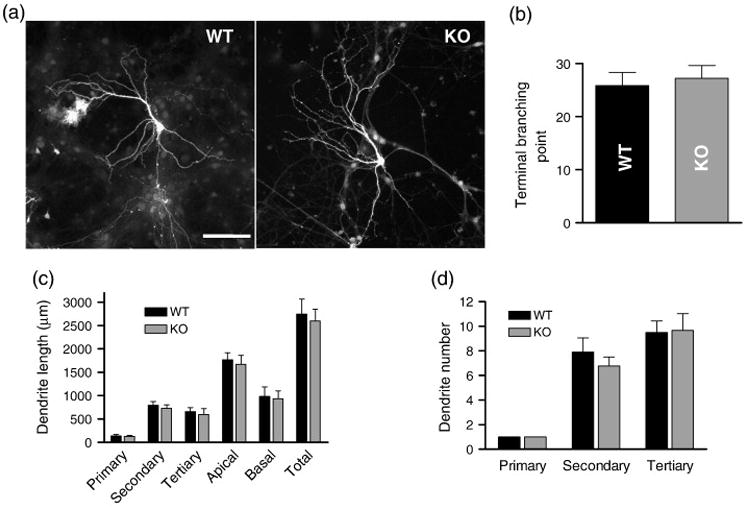

Morphology of dendritic tree in cultured hippocampal neurons and in native hippocampal tissue from KALRN KO mice

Dendritic growth and branching are shaped by Rho family GTPases (Konur and Ghosh, 2005) and their GEFs (Penzes et al., 2001b), and KALRN knockout affects cortical dendrite morphology (Xie et al., 2010). We therefore analyzed dendritic complexity in cultured hippocampal neurons generated from neonatal KO and WT mice and grown for 4 weeks (Fig. 5a) (Penzes et al., 2003). No significant differences in dendritic branching, as reflected by total number of terminal branching points (Fig. 5b; WT 25.8±2.5, KO 27.2±2.4; p=0.609), total dendritic length (Fig. 5c; WT 2748±316 μm, KO 2602±251 μm; p=0.736), as well as numbers of secondary (WT 7.9±1.2, KO 6.8±0.7; p=0.448) and tertiary dendrites (WT 9.5±0.9, KO 9.7±1.4; p=0.918), were detected between the WT and KO mice (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

Dendritic morphology of KALRN KO and WT hippocampal pyramidal neurons in culture (DIV 28). (a) Morphology of cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons from WT and KO mice was visualized by the expression of GFP. (b) Quantification of terminal branching points. (c) Dendrites were traced and the lengths of primary, secondary, and tertiary dendrites, and that of the apical dendritic tree, basal dendritic trees, and all dendrites (total) were measured. (d) Number of the primary, secondary, and tertiary dendrites were counted and plotted. Scale bar: 100 μm.

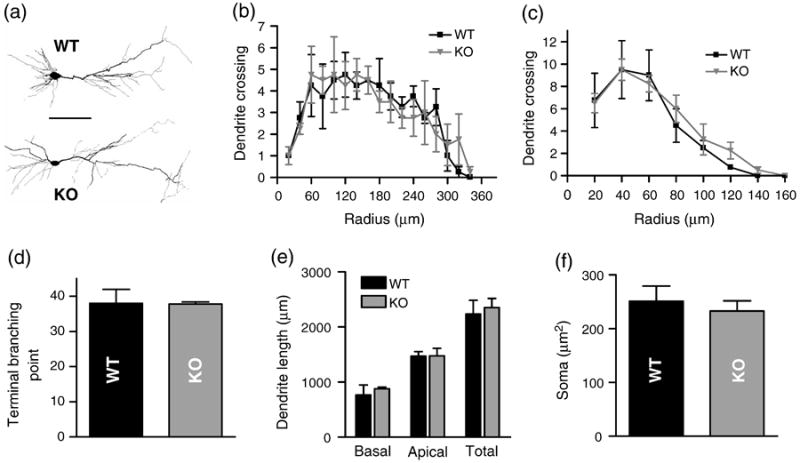

To determine if dendritic morphology in native hippocampal tissue was affected by the knockout of KALRN, we analyzed dendrite morphology in the CA1 region of the hippocampus by Golgi staining (Fig. 6a) (Elia et al., 2006). To quantitatively analyze changes in dendritic structures, CA1 pyramidal neurons were traced with Neurolucida and analyzed using Neurolucida Explorer. Representative 2D projections of the tracings are shown in Fig. 6b. As in cultured neurons, no significant differences in dendritic length and complexity were detected between the WT and KO mice, as reflected by Sholl analysis (Fig. 6c-d), quantification of the total number of terminal branching points (Fig. 6e; WT 38.0±3.9, KO 37.8±0.6; p=0.952), as well as of total apical dendritic length (Fig. 6f; WT 1468±82 μm, KO 1476±139 μm; p=0.966). Moreover, no differences in the size of neuronal somata were detected (Fig. 6g; WT 251±28 μm2, KO 233±19 μm2; p=0.606).

Fig. 6.

Dendritic morphology of hippocampal pyramidal neurons in KALRN KO and WT mice. (a) Representative images of Golgi-stained CA1 pyramidal neurons from the hippocampus of WT and KO mice. (b) Representative 2-D projections of Neurolucida tracing of CA1 pyramidal neurons from the hippocampus of WT and KO mice. Neurolucida tracings were used for Sholl analysis of the apical (c) and basal dendrites (d); and to quantify terminal branching points (e), dendritic lengths (f) and the cross-sectional areas of neuronal somata (g). Scale bars: 100 μm.

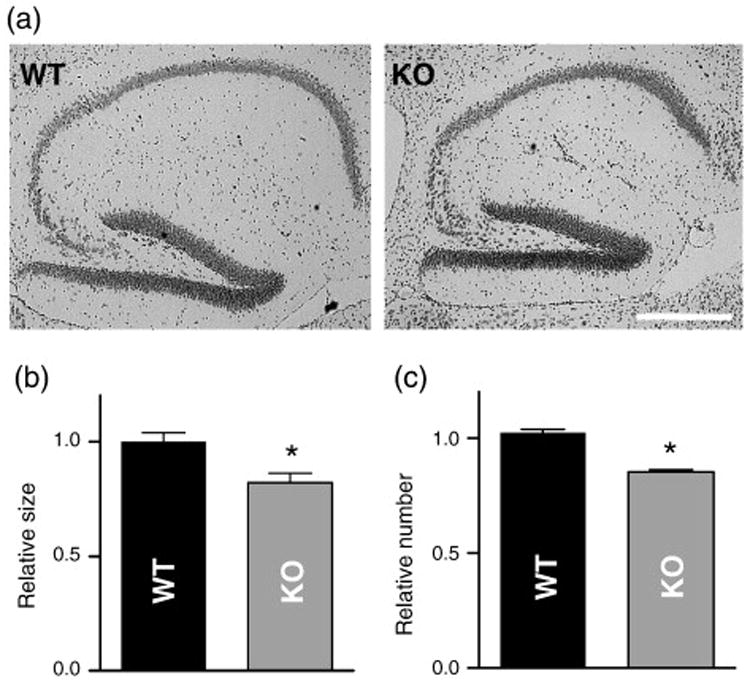

Hippocampal morphology in KALRN KO mice

To determine if knocking out KALRN resulted in anatomical modifications in the hippocampus, we compared the gross morphology of the hippocampus in WT and KO mice (Fig. 7). We used histochemical staining with Nissl and eosin/hematoxylin reagents on sagittal brain sections of 12-week old WT and KO littermate mice, and analyzed them by wide-field microscopy. Analysis indicated that the total hippocampal cross-sectional area was reduced in KO versus WT mice (Fig. 7b) KO was 82.2±3.9% of WT littermates, p<0.05). In contrast, the size of the cerebellum was not altered (Xie et al., 2009). As dendrite branching was not affected, to determine the cellular alterations that may underlie this reduction in hippocampal size, we determined the number of neurons in the hippocampal CA1∼CA4 region. We found that cell number was slightly but significantly reduced (Fig. 7c, number of neurons in KO was 85.3±0.8% of that of WT littermates, p<0.05), suggesting that reduced cell numbers in the hippocampus may account for the reduced hippocampal size.

Fig. 7.

Morphological changes in the hippocampus of KALRN KO mice. (a) Nissl stained sagittal sections of WT and KO brains showing the hippocampus region. (b) Reduction of the hippocampal cross-sectional area of KALRN KO mice compared with WT littermates. (c) Neuronal numbers in the CA1∼CA4 region was reduced in the KALRN KO mice compared with WT littermates. *, p<0.05. Scale bar: 500 μm.

Discussion

In this study we report that complete absence of kalirin resulted in modestly impaired hippocampal plasticity without an impairment in synaptic transmission, an impairment in both context and cue-dependent fear conditioning, but no significant effects on spine density or dendrite morphology. In addition, we detected a reduction in overall hippocampal size, associated with reduced cell numbers. Taken together, these data suggest that kalirin is important for hippocampal plasticity, but that in its absence basal hippocampal synaptic function and structure are not affected. In addition, these findings suggest potentially important roles for kalirin in other neocortical structures, such as the amygdala.

Role of kalirin in hippocampal LTP and behavior

We found that in the hippocampus, loss of kalirin does not impair basal synaptic transmission, but it affects activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. On the other hand, we have previously shown that in the cortex, kalirin loss affects basal AMPA receptor mediated synaptic transmission (Cahill et al., 2009). This suggests that the hippocampal phenotype is milder than the cortical phenotype, and it is only evident under specific environmental conditions, such as plasticity-inducing stimuli. This could be explained either by a compensatory mechanism that acts in the hippocampus but not in the cortex, or by an intrinsic robustness of the hippocampal circuits as compared to the cortical circuit in face of loss of kalirin. Interestingly, KALRN KO mice did not show impaired spatial reference memory (Cahill et al., 2009), which is a hippocampus-dependent task, indicating that at least some hippocampal functions have been preserved in these mice.

Interestingly, this study found reduced synaptic facilitation in the KALRN KO mice. This finding is suggestive of presynaptic increase in baseline probability of neurotransmitter release, as facilitation occurs at the presynaptic side. This may be caused either by a potential presynaptic role of the kalirin-9 and kalirin-12 isoforms, which have been detected presynaptically (Penzes et al., 2001a), or by a retrograde effect caused by absence of postsynaptic kalirin-7, though trans-synaptic adhesion molecules, such as N-cadherin and ephrinB/EphB, which interact with kalirin-7 (Penzes et al., 2003; Xie et al., 2008). However, changes in postsynaptic response can not be excluded, because it is possible that the apparent increase in probability of release might be compensatory to allow normalization of the weaker postsynaptic baseline response.

Fear conditioning is commonly used to analyze cognitive functions in mutant mice, and Δkalirin-7 mice have context-dependent fear conditioning impairments (Ma et al., 2008). We analyzed fear learning in KALRN KO mice, and found that both context and cue-dependent fear conditioning were impaired in KALRN KO mice. Previous studies have suggested a disassociated role for the hippocampus in fear learning such that the hippocampus is necessary for context-dependent fear conditioning, but is not crucial for cue-dependent fear learning. These studies further indicate that the amygdala is necessary for both context and cue-dependent fear learning (Phillips and LeDoux, 1992).

However, very recent studies have revealed a more complicated, yet precise, role for the hippocampus in fear conditioning, and have shown that the conditioning strength, determine partially by footshock intensity, determines the extent of the hippocampal contribution (Maren, 2008; Quinn et al., 2008). Specifically hippocampal dysfunction does impair cue-dependent freezing resulting from weak footshock-tone pairings (e.g., footshock intensity of less than 0.4ma), without affecting cue-dependent freezing resulting from stronger footshock-tone pairings (Quinn et al., 2008). Because we used a fairly strong footshock-tone pairing, that KALRN KO mice have impairments in both context and cue-dependent learning would not necessarily preclude a role for hippocampal dysfunction in contributing to the fear learning impairment. Indeed, in a previous study we found that although KALRN KO mice were able to learn a hippocampal-dependent spatial reference memory task, they were impaired in the initial acquisition of this task (Cahill et al., 2009), indicating that the hippocampal contribution to behavior is not completely unimpaired in the KO mice.

The pronounced cue-dependent fear learning in the KALRN KO mice is suggestive of a contribution of amygdala dysfunction to fear learning. Indeed kalirin is enriched in the amygdala (Ma et al., 2001), and future studies that assess the structure and function of the amygdala in KALRN KO mice would greatly increase the understanding of kalirin's role in the brain.

Role of kalirin in basal dendrite and spine morphology

Kalirin has been previously investigated as a regulator of spine and dendrite morphogenesis. In the present study we found that loss of kalirin had minimal effects on spine density and the morphology of the dendritic tree in cultured hippocampal neurons and in the native CA1 hippocampal tissue. On the contrary, cortical pyramidal neurons in KALRN KO mice showed substantial spine loss and reduced dendritic branching and complexity (Cahill et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2010). Due to the presence of other Rac-GEFs (Tiam1 and βPIX) in mature hippocampal but not cortical spines (Ehler et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2000; Penzes et al., 2008), kalirin may be required to different extents in the hippocampus and cortex. Data from this study, in combination with our recent studies (Cahill et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2010), indicate that kalirin is uniquely important for excitatory transmission in the cortex, as Tiam1 and βPIX are not abundant in mature cortical neurons. Conversely, all three GEFs seem to be involved in synaptic transmission in the hippocampus (Saneyoshi et al., 2008; Tolias et al., 2005), where greater functional redundancy exists. Understanding kalirin's differential roles in different brain regions will thus be necessary to provide a more complete mechanism for the regulation of plasticity by actin cytoskeletal rearrangements.

Comparison between KALRN KO and Δ-kalirin-7 mice

The KALRN gene produces several kalirin isoforms generated by alternative splicing. A recent study examined mice with a deletion of the exon encoding a short peptide targeting kalirin-7 to spines (Ma et al., 2008). Table 1 summarizes the biochemical, morphological, electrophysiological, and behavioral phenotypes of KALRN KO and Δkalirin-7 mice. The removal of the exon encoding the C-terminus of kalirin-7 resulted in compensatory upregulation of the non-synaptic kalirin-8, -9 and -12 isoforms, and an approximate 25% reduction in total forebrain kalirin protein in the Δkalirin-7 mice, even though kalirin-7 accounts for about 75% of total kalirin in the adult WT forebrain. In contrast, KALRN KO mice were designed to be deficient in all kalirin forms, preventing possible compensatory effects (Cahill et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Comparison of the phenotypes of KALRN KO and Δkalirin-7 mutant mice.

| phenotype | KALRN KO | Δkalirin-7 |

|---|---|---|

| Biochemistry | ||

| kalirin-5, kalirin-7 protein level | absent | absent |

| kairin-9, kairin-12 protein level | absent | 50% increase |

| net kalirin protein levels | absent | 75% of WT |

| Rac1 activity - cortex | reduced | normal |

| Rac1 activity - hippocampus | normal | ND |

| Cellular morphology | ||

| gross morphology - cortex | smaller in KO | normal |

| gross morphology - hippocampus | smaller in KO | normal |

| spine density - cortex | ∼ 60% of WT | ND |

| spine density - hippocampus | normal | 85% of WT |

| presynaptic marker - cortex | normal | ND |

| presynaptic marker - hippocampus | normal | slight decrease* |

| postsynaptic marker - cortex | normal | ND |

| postsynaptic marker - hippocampus | normal | slight decrease* |

| dendrite complexity - cortex | reduced | ND |

| dendrite complexity - hippocampus | normal | ND |

| spine density in cortical culture | ∼ 60% of WT | reduced |

| spine density in hippocampal culture | normal | ND |

| dendrite complexity - cortex | reduced | ND |

| dendrite complexity - hippocampus | normal | ND |

| spine density in cortical culture | ∼ 60% of WT | reduced |

| spine density in hippocampal culture | normal | ND |

| dendrite complexity - cortex | reduced | ND |

| dendrite complexity - hippocampus | normal | ND |

| dendrite complexity in cortical culture | reduced | ND |

| dendrite complexity in hippocampal culture | normal | ND |

| Electrophysiology | ||

| AMPA mEPSC cortex | reduced | ND |

| basal transmission hippocampus | normal | normal |

| LTP hippocampus | reduced | reduced |

| paired pulse facilitation | reduced | ND |

| Behavior | ||

| contextual fear conditioning | impaired | impaired |

| cued fear conditioning | impaired | ND |

| short-term memory | impaired | normal |

| long-term memory | normal | normal |

| social behavior | impaired | ND |

| pre-pulse inhibition | impaired | ND |

| anxiety-like behavior | ND | reduced |

| locomotor activity | increased | normal (open field) |

data not shown in Ma et al., 2008; ND, not determined

KALRN KO mice exhibit some features similar to the Δkalirin-7 mice, in that they are viable, fertile, have no obvious defects in gross anatomy, and show normal mobility and sensory perception (Cahill et al., 2009). Cortical cultures from both Δkalirin-7 and KALRN KO mice showed reduced spine density. While cortical spine density and dendrite complexity was reduced in vivo in KALRN KO mice (Cahill et al., 2009), spine density in cortical tissue from Δkalirin-7 mice has not been reported. Interestingly, Δkalirin-7 mutant mice and KALRN KO mice show several differences in neuronal ultrastructure. Notably, Δkalirin-7 mice exhibit a slight reduction in hippocampal spine density (about 15%), which contrasts with our previous finding that full KALRN knockout affected neither hippocampal Rac1-GTP levels nor hippocampal spine density. KALRN-/-mice show a reduction in active Rac1 levels in the cortex, while active Rac1 levels were unaltered in the Δkalirin-7 cortex. The upregulation of the kalirin-9 and -12 isoforms in the Δkalirin-7 mouse could contribute to the reduced hippocampal spine density, as kalirin-9 and kalirin-12 are not normally expressed at high levels in the adult forebrain, and they also contain a RhoA domain (Rabiner et al., 2005), which has an established role in spine elimination (Tashiro et al., 2000).

KALRN KO and Δkalirin-7 mice also showed some differing behavioral phenotypes. Most importantly, KALRN KO mice showed a deficit in spatial working memory, which was unimpaired in Δkalirin-7 mice (Ma et al., 2008). These differences could potentially be explained by the presence of residual kalirin activity (in the form of kalirin-9 and -12) in Δkalirin-7 mice. The resulting differences in Rac1 activity levels in the cortex from these animals might contribute to the differing behavioral phenotypes as KALRN KO mice show a reduction in active Rac1 levels in the cortex while active Rac1 levels were unaltered in the Δkalirin-7 cortex. Differences in working memory performance between Δkalirin-7 and KALRN KO mice might also be due to the different cognitive demands of the tasks used. To assess the spatial working memory performance of Δkalirin-7 mice, a radial arm maze task was used in which both extra-maze and intra-maze cues were positioned around or within the maze (Ma et al., 2008). On the contrary, we found a deficit in spatial working memory in two independent tasks when extra-maze cues were prevalent, but intra-maze cues absent. However, when we assessed spontaneous alternation behavior in the Y-maze in the presence of intra-mazecues, the performance of KALRN KO mice was not different from that of WT mice. This suggests that both Δkalirin-7 and KALRN KO mice are able to use intra-maze cues to guide performance. Whether Δkalirin-7 mice show normal spatial working memory in the absence of intra-maze cues has not been reported.

Both KALRN KO and Δkalirin-7 mice showed impairments in context dependent fear conditioning, which lead the authors to conclude that Δkalirin-7 mice have impaired hippocampal function. However, cued fear conditioning has not been assessed in Δkalirin-7 mice. Our findings indicate that these deficits may in fact be caused by impairment in amygdala function.

Implications for disease

Recent studies on human subjects suggest potential roles for kalirin signaling in several neuropsychiatric disorders. Reduced expression of kalirin mRNA has been detected in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia (Hill et al., 2006; Narayan et al., 2008), and these reduced kalirin transcript levels correlated strongly with spine loss in the schizophrenia frontal cortex irrespective of antipsychotic treatment (Hill et al., 2006). Interestingly, kalirin directly interacts with a leading schizophrenia susceptibility gene DISC1 (Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia-1) (Millar et al., 2003). DISC1 is important for the synaptic localization of kalirin-7, regulates its Rac-GEF activity, and thereby modulates morphogenesis through kalirin-7 (Hayashi-Takagi et al., 2010). These studies suggest that a hypofunction of the kalirin signaling pathway may contribute to reduced spine density in schizophrenic patients.

Recent studies have also shown that kalirin plays an important role in serotonergic signaling: the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor modulates spine remodeling through kalirin-7, Rac1 and PAK signaling (Jones et al., 2009). As the 5-HT2A receptor is a target of several hallucinogens, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, and antidepressants, and it has been associated with several psychiatric disorders, such findings further strengthen a role for kalirin in addiction and mental illness.

Neuropathological and functional studies also implicate kalirin in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. Analysis of postmortem brain tissue found that in human subjects with Alzheimer's disease kalirin mRNA and protein were consistently underexpressed (Youn et al., 2007a). Kalirin also interacts with Huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1) (Colomer et al., 1997), which is potentially interesting as morphological alterations of dendrites and spines occur in Huntington's disease and in animal models of Huntington's disease (Yasuda et al., 1995; Youn et al., 2007b). In addition, kalirin-7 mediates the regulation of ischemic signal transduction in the hippocampus (Beresewicz et al., 2008). Taken together, these findings implicate kalirin in the pathogenesis of several psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1 Comparison of pre-tone and tone freezing during cue-conditioning. (a) WT mice show more freezing during the tone presentation relative to the 1-minute pre-tone period during the cue-conditioning test. Significant differences were observed at the 45-minute, 24-hour, and 48-hour testing periods. (b) KO mice show more freezing to the tone relative to the pre-tone period at the 24-hour and 48-hour time points. No significant differences were observed at the 45-minute time point. This is likely due to the low freezing response to the tone at the 45-minute period in the KO mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kelly Jones and Igor Rafalovich for editing. This work was supported by grants from NIH-NIMH (R01MH071316), National Alliance for Autism Research (NAAR), National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), and Alzheimer's Association (to P.P.), NIH-NIMH (MH078064) and Dunbar Funds (to J.R.), NIH-NIMH (MH57014) and Evelyn F. McKnight (to J.D.S. and C.A.M.), NIH-NIMH (P01 MH074866) and NIH-NINDS (R37 NS034696) (to D.J.S.) and training grants (NINDS 5T32NS041234) to Z.X. and (NIH 1F31AG031621) to M.E.C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvarez VA, Sabatini BL. Anatomical and physiological plasticity of dendritic spines. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:79–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beresewicz M, Kowalczyk JE, Zablocka B. Kalirin-7, a protein enriched in postsynaptic density, is involved in ischemic signal transduction. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:1789–1794. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9631-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill ME, Xie Z, Day M, Photowala H, Barbolina MV, Miller CA, Weiss C, Radulovic J, Sweatt JD, Disterhoft JF, Surmeier DJ, Penzes P. Kalirin regulates cortical spine morphogenesis and disease-related behavioral phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13058–13063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904636106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer V, Engelender S, Sharp AH, Duan K, Cooper JK, Lanahan A, Lyford G, Worley P, Ross CA. Huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1) binds to a Trio-like polypeptide, with a rac1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor domain. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1519–1525. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.9.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierssen M, Ramakers GJ. Dendritic pathology in mental retardation: from molecular genetics to neurobiology. Genes, brain, and behavior. 2006;5(2):48–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehler E, van Leeuwen F, Collard JG, Salinas PC. Expression of Tiam-1 in the developing brain suggests a role for the Tiam-1-Rac signaling pathway in cell migration and neurite outgrowth. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 1997;9:1–12. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia LP, Yamamoto M, Zang K, Reichardt LF. p120 catenin regulates dendritic spine and synapse development through Rho-family GTPases and cadherins. Neuron. 2006;51:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS. Factors governing one-trial contextual conditioning. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1990a;18:264–270. [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS. Factors governing one-trial contexual conditioning. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1990b;18:264–270. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi-Takagi A, Takaki M, Graziane N, Seshadri S, Murdoch H, Dunlop AJ, Makino Y, Seshadri AJ, Ishizuka K, Srivastava DP, Xie Z, Baraban JM, Houslay MD, Tomoda T, Brandon NJ, Kamiya A, Yan Z, Penzes P, Sawa A. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) regulates spines of the glutamate synapse via Rac1. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nn.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JJ, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Molecular mechanisms contributing to dendritic spine alterations in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:557–566. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Penzes P, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Isoforms of kalirin, a neuronal Dbl family member, generated through use of different 5′- and 3′-ends along with an internal translational initiation site. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19324–19333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KA, Srivastava DP, Allen JA, Strachan RT, Roth BL, Penzes P. Rapid modulation of spine morphology by the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor through kalirin-7 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19575–19580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905884106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kim T, Lee D, Park SH, Kim H, Park D. Molecular cloning of neuronally expressed mouse betaPix isoforms. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2000;272:721–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konur S, Ghosh A. Calcium signaling and the control of dendritic development. Neuron. 2005;46:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual review of neuroscience. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson JM, O'Riordan KJ, Brown KD, Trinh MA, Molfese DL, Sweatt JD. Regulation of histone acetylation during memory formation in the hippocampus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40545–40559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Huang J, Wang Y, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Kalirin, a multifunctional Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor, is necessary for maintenance of hippocampal pyramidal neuron dendrites and dendritic spines. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10593–10603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10593.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Johnson RC, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Expression of kalirin, a neuronal GDP/GTP exchange factor of the trio family, in the central nervous system of the adult rat. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429:388–402. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010115)429:3<388::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Kiraly DD, Gaier ED, Wang Y, Kim EJ, Levine ES, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Kalirin-7 is required for synaptic structure and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12368–12382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4269-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S. Pavlovian fear conditioning as a behavioral assay for hippocampus and amygdala function: cautions and caveats. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:1661–1666. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar JK, Christie S, Porteous DJ. Yeast two-hybrid screens implicate DISC1 in brain development and function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:1019–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama AY, Harms MB, Luo L. Small GTPases Rac and Rho in the maintenance of dendritic spines and branches in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5329–5338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05329.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama AY, Luo L. Intracellular signaling pathways that regulate dendritic spine morphogenesis. Hippocampus. 2000;10:582–586. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:5<582::AID-HIPO8>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan S, Tang B, Head SR, Gilmartin TJ, Sutcliffe JG, Dean B, Thomas EA. Molecular profiles of schizophrenia in the CNS at different stages of illness. Brain Res. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Beeser A, Chernoff J, Schiller MR, Eipper BA, Mains RE, Huganir RL. Rapid induction of dendritic spine morphogenesis by trans-synaptic ephrinB-EphB receptor activation of the Rho-GEF kalirin. Neuron. 2003;37:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Cahill ME, Jones KA, Srivastava DP. Convergent CaMK and RacGEF signals control dendritic structure and function. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Johnson RC, Alam MR, Kambampati V, Mains RE, Eipper BA. An isoform of kalirin, a brain-specific GDP/GTP exchange factor, is enriched in the postsynaptic density fraction. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:6395–6403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Johnson RC, Kambampati V, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Distinct roles for the two Rho GDP/GTP exchange factor domains of kalirin in regulation of neurite growth and neuronal morphology. J Neurosci. 2001a;21:8426–8434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08426.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Johnson RC, Sattler R, Zhang X, Huganir RL, Kambampati V, Mains RE, Eipper BA. The neuronal Rho-GEF Kalirin-7 interacts with PDZ domain-containing proteins and regulates dendritic morphogenesis. Neuron. 2001b;29:229–242. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Jones KA. Dendritic spine dynamics--a key role for kalirin-7. Trends in neurosciences. 2008;31:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JJ, Wied HM, Ma QD, Tinsley MR, Fanselow MS. Dorsal hippocampus involvement in delay fear conditioning depends upon the strength of the tone-footshock association. Hippocampus. 2008;18:640–654. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner CA, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin: a dual Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor that is so much more than the sum of its many parts. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:148–160. doi: 10.1177/1073858404271250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saneyoshi T, Wayman G, Fortin D, Davare M, Hoshi N, Nozaki N, Natsume T, Soderling TR. Activity-dependent synaptogenesis: regulation by a CaM-kinase kinase/CaM-kinase I/betaPIX signaling complex. Neuron. 2008;57:94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Minden A, Yuste R. Regulation of dendritic spine morphology by the rho family of small GTPases: antagonistic roles of Rac and Rho. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:927–938. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threadgill R, Bobb K, Ghosh A. Regulation of dendritic growth and remodeling by Rho, Rac, and Cdc42. Neuron. 1997;19:625–634. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80376-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolias KF, Bikoff JB, Burette A, Paradis S, Harrar D, Tavazoie S, Weinberg RJ, Greenberg ME. The Rac1-GEF Tiam1 couples the NMDA receptor to the activity-dependent development of dendritic arbors and spines. Neuron. 2005;45:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WT, Faulkner-Jones BE, Sanes JR, Wong RO. Rapid dendritic remodeling in the developing retina: dependence on neurotransmission and reciprocal regulation by Rac and Rho. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5024–5036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-05024.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Cahill ME, Penzes P. Kalirin loss results in cortical morphological alterations. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;43:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Photowala H, Cahill ME, Srivastava DP, Woolfrey KM, Shum CY, Huganir RL, Penzes P. Coordination of synaptic adhesion with dendritic spine remodeling by AF-6 and kalirin-7. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6079–6091. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1170-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Srivastava DP, Photowala H, Kai L, Cahill ME, Woolfrey KM, Shum CY, Surmeier DJ, Penzes P. Kalirin-7 controls activity-dependent structural and functional plasticity of dendritic spines. Neuron. 2007;56:640–656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda RP, Ikonomovic MD, Sheffield R, Rubin RT, Wolfe BB, Armstrong DM. Reduction of AMPA-selective glutamate receptor subunits in the entorhinal cortex of patients with Alzheimer's disease pathology: a biochemical study. Brain research. 1995;678:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00178-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn H, Jeoung M, Koo Y, Ji H, Markesbery WR, Ji I, Ji TH. Kalirin is under-expressed in Alzheimer's disease hippocampus. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007a;11:385–397. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn H, Ji I, Ji HP, Markesbery WR, Ji TH. Under-expression of Kalirin-7 Increases iNOS activity in cultured cells and correlates to elevated iNOS activity in Alzheimer's disease hippocampus. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007b;12:271–281. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Comparison of pre-tone and tone freezing during cue-conditioning. (a) WT mice show more freezing during the tone presentation relative to the 1-minute pre-tone period during the cue-conditioning test. Significant differences were observed at the 45-minute, 24-hour, and 48-hour testing periods. (b) KO mice show more freezing to the tone relative to the pre-tone period at the 24-hour and 48-hour time points. No significant differences were observed at the 45-minute time point. This is likely due to the low freezing response to the tone at the 45-minute period in the KO mice.