Abstract

We aimed to discover whether metabolic complications of schizophrenia (SZ) are present in first episode (FE) and unmedicated (UM) patients, in comparison with patients established on antipsychotic medication (AP).

Method:

A systematic search, critical appraisal, and meta-analysis were conducted of studies to December 2011 using Medline, PsycINFO, Embase and experts. Twenty-six studies examined FE SZ patients (n = 2548) and 19 included UM SZ patients (n = 1325). For comparison we identified 78 publications involving 24 892 medicated patients who had chronic SZ already established on AP.

Results:

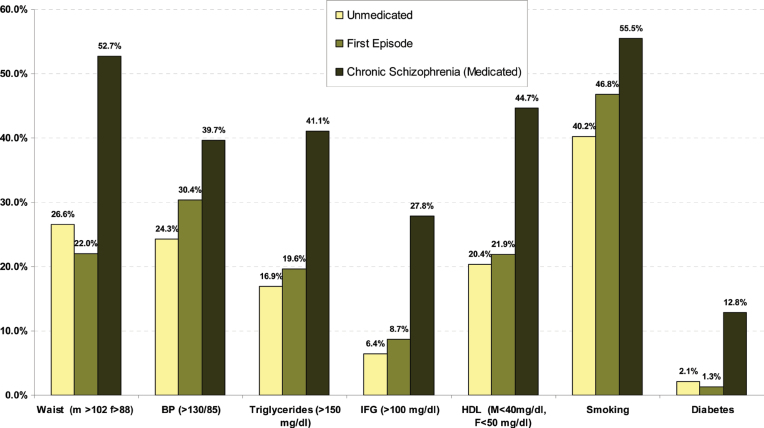

In UM, the overall rate of metabolic syndrome (MetS) was 9.8% using any standardized criteria. Diabetes was found in only 2.1% and hyperglycaemia (>100mg/dl) in 6.4%. In FE, the overall MetS rate was 9.9%, diabetes was found in only 1.2%, and hyperglycaemia in 8.7%. In UM and FE, the rates of overweight were 26.6%, 22%; hypertriglyceridemia 16.9%, 19.6%; low HDL 20.4%, 21.9%; high blood pressure 24.3%, 30.4%; smoking 40.2%, 46.8%, respectively. In both groups all metabolic components and risk factors were significantly less common in early SZ than in those already established on AP. Waist size, blood pressure and smoking were significantly lower in UM compared with FE.

Conclusion:

There is a significantly lower cardiovascular risk in early SZ than in chronic SZ. Both diabetes and pre-diabetes appear uncommon in the early stages, especially in UM. However, smoking does appear to be elevated early after diagnosis. Clinicians should focus on preventing initial cardiometabolic risk because subsequent reduction in this risk is more difficult to achieve, either through behavioral or pharmacologic interventions.

Key words: cardiovascular risk, diabetes, lipids, glucose, waist, obesity

Introduction

Different reviews and studies have shown that patients with schizophrenia have an excess mortality, being 2 or 3 times as high as that in the general population. 1–7 This mortality gap, which translates to a 13–30-year shortened life expectancy, has widened in recent decades. 8–10 Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) have an increased prevalence among patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and account for much of the increased mortality rate in this group. 8–10 Screening and monitoring cardiovascular risk factors are therefore important and in order to help clinicians focus on these CVD risks in patients with schizophrenia/severe mental illness (SMI) the concept of metabolic syndrome (MetS) may be useful. The MetS brings together a collection of abnormal clinical and metabolic findings that are predictive for CVD. 11 These abnormal findings include visceral adiposity (measured by waist size), high fasting glucose, increased blood pressure, elevated triglyceride levels, and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. The most common definitions for the MetS are the working criteria of the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Task Force, 12 the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program, 13 and the adapted Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III-A) proposed by the American Heart Association 14 (table 1).

Table 1.

Working Criteria for the Metabolic Syndrome

| ATP-III (3/5 criteria required) | ATP-III-A (3/5 criteria required) | IDF (waist + 2 criteria) | |

| Waist (cm) | M >102, F>88 | M >102, F > 88 | M ≥ 94, F ≥ 80 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ≥130/85* | ≥130/85* | ≥130/85* |

| HDL (mg/dl) | M <40, F<50 | M < 40, F< 50 | M < 40, F < 50 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | ≥150 | ≥150 | ≥150 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | ≥110** | ≥100** | ≥100** |

Abbreviations: ATP, Adult Treatment Panel36; ATP-A, Adult Treatment Protocol-Adapted37; IDF, International Diabetes Federation38; M, males; F, females; HDL, high density lipoproteins;*or treated with antihypertensive medication;**or treated with insulin or hypoglycaemic medication.

In a recent meta-analysis we demonstrated that almost 1 in 3 of unselected patients with schizophrenia meet criteria for MetS,1 in 2 patients are overweight, 1 in 5 appear to have significant hyperglycaemia and at least 2 in 5 have lipid abnormalities. 15 Metabolic complications particular weight gain can be distressing. 16 – 17 Cardio-metabolic abnormalities have also become a major concern in the early treatment of psychosis because it is often associated with a lower functional outcome, 18 poorer quality of life, 19 , 20 and noncompliance to antipsychotic medication. 21 The reasons that underlie the high prevalence of metabolic abnormalities are much debated, especially when considering the possible role of antipsychotic medication in the occurrence of these abnormalities. Several reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated a role of certain second-generation antipsychotics (SGA). 15 , 22 – 26 There is, however, also preliminary evidence for an increased prevalence of central obesity and glucose abnormalities such as impaired fasting glucose and insulin resistance in drug-naive first-episode patients, suggesting that metabolic disturbances may begin early prior to starting medication. 27 In support of this there are indications of an increased risk for diabetes in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia. 28 A recent systematic review however found that in general, there was no difference in cardiovascular risk assessed by weight or metabolic indices between individuals with an untreated first episode of psychosis and healthy controls. 29 More research is needed to understand the magnitude and nature of CVD risk factors associated with schizophrenia and related psychoses in the early phase of illness.

Distinguishing pre-existing risk from treatment effects is important for understanding the source of metabolic abnormalities associated with antipsychotic treatment and to inform decisions regarding medication review and other interventions. Previous reviews and meta-analyses indicated that cardiovascular risk increases after first exposure to any antipsychotic drug in children and adolescents 30 , 31 and in first-episode patients. 29 , 32 These reviews and meta-analyses have not been able to quantify the extent of metabolic problems with the possible exception of weight gain. Tarricone et al. 33 estimated weight gain to average 3.8kg from just three studies of drug-naive patients reviewed 3 months after starting antipsychotic treatment using last observation carried forward analysis. Only limited data on differences in MetS rates between patients taking different antipsychotics are available. 25 Further, these are short-term studies without any consideration for previously prescribed medication. A distinction between cardio- metabolic side effects of antipsychotic medication and underlying disease can only be made at the very beginning of treatment in patients with a first episode who have not and/or with patients who are never or only very limited been exposed to antipsychotic drugs.

Given all these uncertainties, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis with an objective to clarify prevalence rate of MetS in unmedicated (UM) and first-episode (FE) patients with schizophrenia. Our secondary aim was to clarify the prevalence rates of every individual MetS risk factor.

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA standard (a protocol used to evaluate systematic reviews). 34 Our focus was on UM and on FE patients with defined schizophrenia (or related psychosis). In order to be included as FE patients, studies had to explicitly define whether their participants experienced a FE of psychosis or were in the early phase of psychosis. We expected to find varying definitions of first-episode and early psychosis, and therefore we accepted any definitions used. FE patients could be medicated or antipsychotic naive. The unmedicated group included those antipsychotic naive patients at any stage of illness, including their first episode. Thus, there was some overlap between unmedicated and first-episode results. Studies were included that systematically examined metabolic abnormalities in general and the MetS using ATP III 13 , ATP III-A, 14 or IDF 12 criteria in particular. We excluded studies with inadequate data for extraction. We also excluded studies on children and adolescents as specific variations in MetS-criteria in these patients warrants a separate analysis. 35 For comparison purposes we also report data from our previous meta-analysis 15 concerning those patients not in their first episode of psychosis and currently medicated with antipsychotic medication.

Search Criteria and Critical Appraisal

A systematic literature search, critical appraisal of the collected studies, and meta-analysis were conducted. The following abstract databases were searched from inception to December 2011: Medline, PsycINFO, Embase. Four full text collections namely Science Direct, Ingenta Select, Ovid Full text, and Blackwell/Wiley Interscience were searched. The abstract database Web of Knowledge (4.0, ISI) was searched, using the above terms as a text word search, and using key papers in a reverse citation search. The following search terms were used: “metabolic or metabolic syndrome or diabetes or cardiovascular or blood pressure or glucose or lipid” and “psychosis or psychotic or schizophrenia or schizoaffective.” We also contacted several experts in the field for papers in preparation and additional data and received data from three groups (see acknowledgments). Methodological appraisal of each study was conducted according to PRISMA standard including evaluation of bias (confounding, overlapping data, and publication bias).

Statistical Analysis

We pooled individual study data using DerSimonian-Laird 36 proportion meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was invariably moderate to high therefore a random effects meta-analysis was performed using StatsDirect 2.7.7.

For comparative analyses we required a minimum of three independent studies to justify analysis according to convention. In order to elucidate subgroup effects we stratified data where appropriate and used chi square statistic to compare proportions.

Results

Search Results

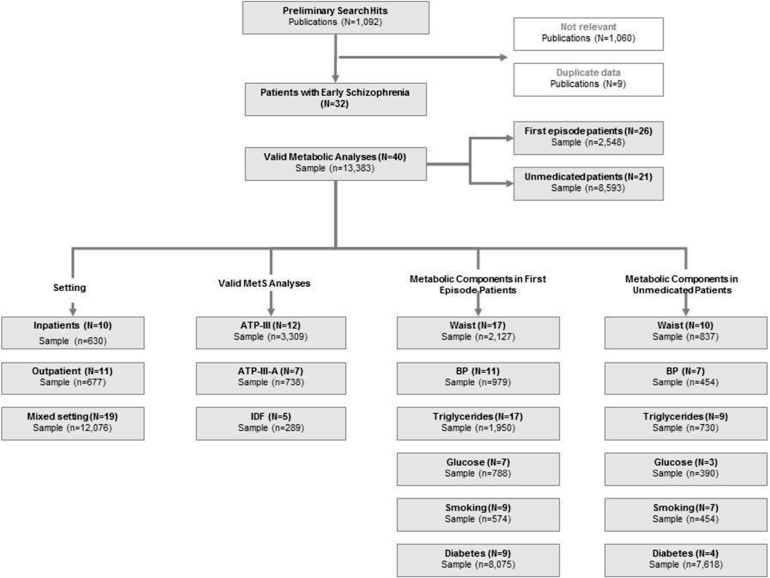

From 93 candidate publications following exclusions, our search generated 32 publications containing 40 main analyses (see figure 1). We excluded 9 publications with data that were duplicates from the same group. The dataset comprised 13 383 unique patients from 24 countries or regions. Twenty-six of 40 main analyses (65%) used DSM criteria to define schizophrenia and related psychosis, 6 (15%) used ICD10 criteria, and 8 (20%) used clinical expert judgment or miscellaneous criteria.

Fig. 1.

Quorom figure of metabolic studies in early schizophrenia.

Of 40 main analyses, 10 involved inpatients (n = 630), 11 were conducted in outpatient settings (n = 677), and 19 were conducted in mixed samples (n = 12 076). Twenty-six studies examined individuals who were in their first episode (n = 2548), 21 included UM patients with schizophrenia (n = 8593). Only in 5 of the 26 FE studies (n = 887), patients were medicated. In 3 of the 5 studies exposure was limited from less than 2 weeks to less than 3 months, while in 2 studies also data after an average of 3 years of exposure were available. Six analyses reported data on males and females separately. The mean age of UM and FE patients was 27.9±5.8 years and 28.4±8.9 years, respectively. This is compared with 41.8±8.2 years in the chronic schizophrenia comparison sample. While in the FE group, 46.8% (N = 9; n = 574; 95% CI = 28.5%–65.5%) of the patients smoked, smoking rates were 40.2% (N = 7; n = 454; 95% CI = 21.6%–60.3%) in UM patients and 55.5% (N = 37; n = 8630; 95% CI = 52.3%–58.7%) in medicated chronic patients.

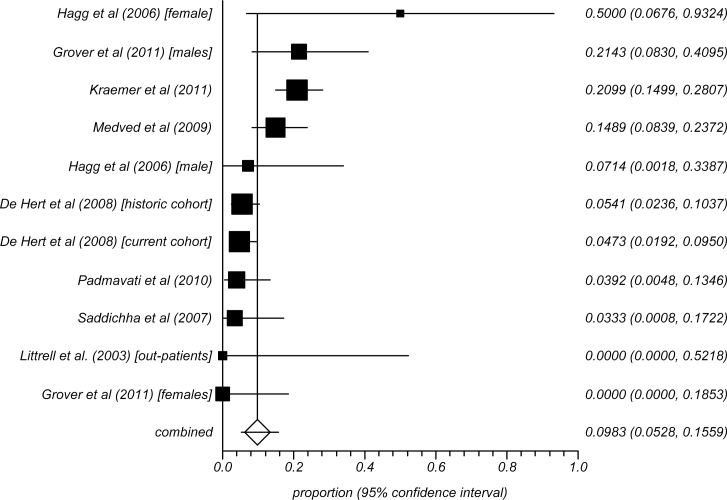

Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Unmedicated Patients With Schizophrenia

Across 11 analyses involving 702 UM patients with schizophrenia, the overall rate of MetS was 9.8% (95% CI = 5.3%–15.6%) using any standardized MetS criteria. The rates using the ATP-III, adapted ATPIII, or IDF definitions were 10.5% (95% CI = 5.9%–16.1%) (N = 12; n = 3309), 12.9% (95% CI = 7.0%–20.3%) (N = 7; n = 738), and 12.16% (95% CI = 6.0%–20.1% (N = 5; n = 289), respectively. The summary rates of the UM patients with schizophrenia are presented in figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of MetS in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia.

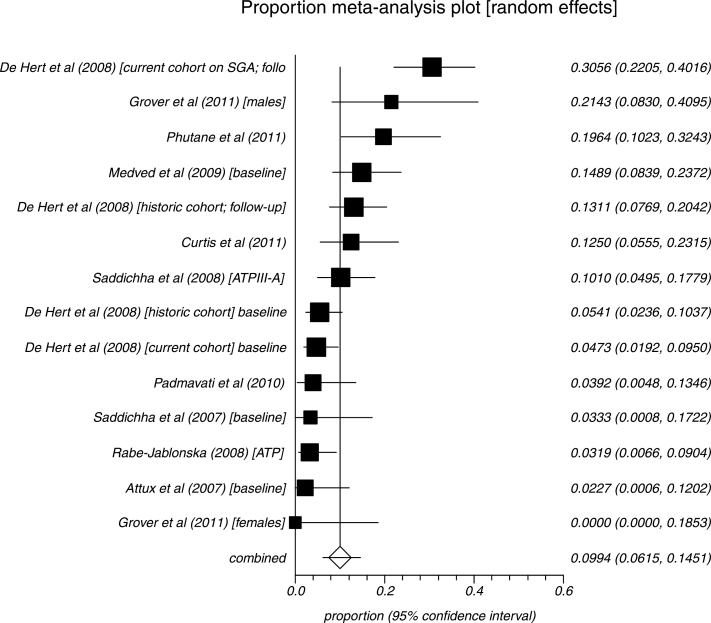

Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in First-Episode Patients

We identified 14 analyses of FE patients (n = 1106). The overall rate of MetS was 9.9% (95% CI = 6.1%–14.5%) using any standardized MetS criteria. The rates using the ATP-III, adapted ATP III, or IDF definitions were 8.3% (N = 5; n = 240; 95% CI = 2.1%–18.1%), 11.8% (N = 5; n = 625; 95% CI = 95% CI = 5.0%–21.0%), and 9.7% (N = 4; n = 239; 95% CI = 4.8%–16.0), respectively. Summary rates are given in figure 3.

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of MetS in first-episode schizophrenia.

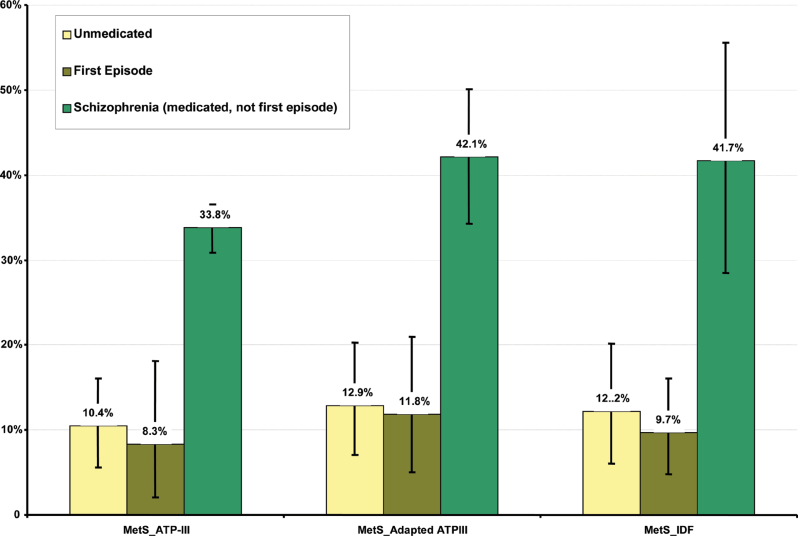

Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Medicated Patients Not in Their First Episode

From our previous meta-analysis 15 of MetS in patients with schizophrenia, we found 78 publications involving 112 analyses and 24 892 medicated patients (41.8±8.2 years) who were not in their first episode. The overall rate of MetS in this group was 35.3% (95% CI = 32.8%–37.8%) using any standardized MetS criteria. The rates using the ATP-III, adapted ATPIII, or IDF definitions were 33.8% (95% CI = 30.9%–36.6%) (N = 75; n = 16 715), 42.1% (95% CI = 34.3%–50.1%) (N = 10; n = 7,775), and 41.7% (95% CI = 28.5%–55.6%) (N = 13; n = 1218). MetS was significantly higher in patients established on antipsychotics than UM (P < 0.001) or FE (P < 0.001) patients (see table 2 and figure 4). MetS was no different between UM and FE patients.

Table 2.

Comparison of Metabolic Risk Factors in Subtypes of Schizophrenia

| MetS by any definition | Waist Size (m > 102, f > 88) | Blood Pressure >130/85 | Triglycerides ( >150mg/dl) | HDL (M < 40mg/dl, F < 50mg/dl) | Hyperglycaemia (>110mg/dl) | Hyperglycaemia (>100mg/dl) | Diabetes | |

| First-episode patients | ||||||||

| Number of studies (N) | 14 | 17 | 11 | 17 | 16 | 5 | 7 | 9 |

| Sample size (n) | 1104 | 2127 | 979 | 1950 | 1950 | 240 | 788 | 8075 |

| Pooled proportion (%) | 9.9 | 22.0 | 30.4 | 19.6 | 21.9 | 6.9 | 8.7 | 1.3 |

| 95% CI | 6.1%–14.5% | 15.6%–29.1% | 21.3%–40.3% | 13.1%–27.0% | 15.6%–28.9% | 5.0%–19.9% | 5,2%–12,9% | 0.4%–2.4% |

| Unmedicated patients | ||||||||

| Number of studies (N) | 11 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 9 | ID | 3 | 4 |

| Sample size (n) | 702 | 837 | 454 | 730 | 730 | ID | 390 | 7618 |

| Pooled proportion (%) | 9.8 | 26.6 | 24.3 | 16.9 | 20.4 | ID | 6.4 | 2.1 |

| 95% CI | 5.2%–15.6% | 15.9%–38.9% | 11.2%–40.5% | 7.6%–29.0% | 9.8%–33.7% | ID | 2.2%–12.7% | 0.5%–4.8% |

| Medicated chronic schizophrenia | ||||||||

| Number of studies (N) | 78 | 58 | 64 | 69 | 68 | 41 | 26 | 12 |

| Sample size (n) | 24,892 | 17,474 | 18,202 | 19.388 | 18.837 | 13214 | 6798 | 2098 |

| Pooled proportion (%) | 35.3 | 52.7 | 39.7 | 41.1 | 44.7 | 18.1 | 27.8 | 12.8 |

| 95% CI | 32.8%–37.8% | 48.9%–56.5% | 36.4%–43.1% | 36.5%–45.7% | 41.2%–48.2% | 15.5%–20.7% | 23.0%–32.9% | 8.44%–17.9% |

| Statistical comparison | ||||||||

| Medicated vs unmedicated (chi squared) | 195.7 (P < 0.0001) | 217.1 (P < 0.0001) | 44.4 (P < 0.0001) | 172.0 (P < 0.0001) | 168.4 (P < 0.0001) | ID | 133.7 (P < 0.0001) | 38.3 (P < 0.0001) |

| Medicated vs first episode (chi squared) | 303.6 (P < 0.0001) | 714.9 (P < 0.0001) | 33.4 (P < 0.0001) | 344.1 (P < 0.0001) | 375.8 (P < 0.0001) | 156.2 (P < 0.0001) | 86.4 (P < 0.0001) | 92.9 (P < 0.0001) |

| Unmedicated vs first episode (chi squared) | 0.000 (P = 0.9755) | 7.2 (P = 0.0072) | 5.9 (P = 0.0154) | 2.6 (P = 0.1063) | 0.7 (P = 0.4043) | ID | 1.9 (P = 0.162) | 1.0 (P = 0.31) |

Note: ID, insufficient data.

Fig. 4.

Comparing MetS rates between first-episode patients, unmedicated patients and medicated patients not in their first episode.

Individual Metabolic Abnormalities in Unmedicated Patients With Schizophrenia

As shown in table 2, 10 studies reported on the rate of obesity defined as a waist (cm) more than 102cm in males and 88cm in females (ATP). The proportion overweight was 26.6% (N = 10; n = 837; 95% CI = 15.9%–38.9%) The rate of hypertriglyceridemia was 16.9% (N = 9; n = 730; 95% CI = 7.6%–29.0%) and the proportion of those with low HDL was 20.4% (N = 9; n = 730; 95% CI = 9.8%–33.7%). About 24.3% (N = 7; n = 454; 95% CI = 11.2%–40.5%) of UM patients with schizophrenia had high blood pressure and 40.2% (N = 7; n = 454; 95% CI = 21.6%–60.3%) were smokers. Nearly 2.1% (N = 4; n = 7618; 95% CI = 0.05%–4.8%) met criteria for diabetes and 6.4% (N = 3; n = 390; 95% CI = 2.2% to 12.7%) met criteria for hyperglycaemia (>100mg/dl).

Individual Metabolic Abnormalities in First-Episode Patients

Table 2 demonstrates that 17 studies reported on the rate of obesity defined as a waist (cm) more than 102cm in males and 88cm in females (ATP). The proportion overweight was 22.0% (N = 17; n = 2127; 95% CI = 15.6%–29.1%). The rate of hypertriglyceridemia was 19.6% (N = 17; n = 1950; 95% CI = 13.1%–27.0%) and the proportion of those with low HDL was 21.9% (N = 16; n = 1950; 95% CI = 15.6%–28.9%). Additionally, 30.4% (N = 11; n = 979; 95% CI = 21.3%–40.3%) of FE patients had high blood pressure and 46.8% (N = 9; n = 574; 95% CI =28.4%–65.5%) were smokers. About 8.7% (N = 7; n = 788; 95% CI = 5.2%–12.9%) met criteria for hyperglycaemia (>100mg/dl) and 1.3% (N = 9; n = 8075; 95% CI = 0.5%–2.4%) met criteria for diabetes. Comparing FE with UM patients showed that the rates of waist size, high blood pressure, and smoking were significantly lower in UM patients compared with FE patients.

Individual Metabolic Abnormalities in Medicated Patients Not in Their First Episode

Table 2 shows also the data updated from our previous meta-analysis 15 in medicated patients not in their first episode. About 58 studies (n = 17 474) reported on rate of obesity defined as a waist (cm) more than 102cm in males and 88cm in females (ATP criteria). The proportion overweight was 52.7% (95% CI = 48.9%–56.5%). The rate of hypertriglyceridemia was 41.1% (N = 69; n = 19 388; 95% CI = 36.5%–45.7%) and the proportion of those with low HDL was 44.7% (N = 68; n = 18 837; 95% CI = 41.2%–48.2%). About 39.7% (N = 64; n = 18 202; 95% CI = 36.4%–43.1%) of medicated patients with schizophrenia had high blood pressure and 55.5% (N = 37; n = 8630; 95% CI = 52.3%–58.7%) were smokers. About 27.8% (N = 26; n = 6798; 95% CI = 23.0%–32.9%) met criteria for hyperglycemia >100mg/dl and 12.8% had diabetes (N = 12; n = 2098; 95% CI = 8.44%–17.9%). All metabolic components were significantly lower in FE and UM patients than in medicated patients (see table 2).

Figure 5 gives an overview of the rates of the individual MetS risk factors in UM patients and in FE patients compared with the rates found in medicated patients not in their first episode.

Fig. 5.

Summary of individual MetS risk factors between first-episode patients, unmedicated patients and medicated patients not in their first episode.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, the present meta-analysis is the first to systematically assess metabolic abnormalities in early schizophrenia specifically in UM and FE patients. Several groups have proposed a liability for people with schizophrenia to develop metabolic abnormalities in the absence of antipsychotic medication. 27 , 37 In both UM and FE patients, the overall rate of MetS was approximately 10% using standardized MetS criteria. The finding that compared with UM patients the metabolic risk in FE was not significantly increased for all metabolic risk factors can be explained by the fact that only a limited number of included FE patients were exposed to antipsychotic medication. Only in the study of De Hert et al. 38 antipsychotic exposure was longer than 3 months. The data of De Hert et al. 38 demonstrated that rates of MetS increased significantly over time in FE patients. Patients started on SGAs did have a 3 times higher incidence rate of MetS (Odds Ratio = 3.6; 95% CI=1.7–7.5) than those on FGA when baseline data were compared with rates after on average 3 years of treatment exposure.

Present data show that rates in UM and FE patients are considerably lower than the 35.3% rate of MetS seen in patients established on antipsychotic medication. 15 Looking at individual MetS risk factors, at least one in five UM and FE patients are overweight (by waist size), have high blood pressure, or have lipid abnormalities. About 46.8% of FE patients and 40.2% of UM patients are current smokers, rates considerably higher than seen in the general populations. However, all of these findings are significantly less than found in patients with chronic schizophrenia established on medication. The rates of diabetes and hyperglycaemia in UM and FE patients appear comparable with population samples. 39 However, we recommended that studies with adequate control matching are examined to more precisely determine if these abnormalities differ with the corresponding general population. We could identify only 8 such studies 40–46 that compared metabolic components in patients and matched healthy controls and most are underpowered. Five of these studies 42–46 found no differences in UM patients drug-naive patients compared with healthy controls. Also a recent systematic review found no difference in cardiovascular risk assessed by weight or metabolic indices between individuals with an untreated FE of psychosis and healthy controls. 29 Three studies showed subtle differences in glucose levels or insulin concentration. For example, Ryan et al. 47 found impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and higher insulin levels in 26 drugs-naive FE inpatients compared with 26 controls matched for age, sex, exercise, diet and smoking habits, and alcohol intake. Spelman et al. 40 studied UM never treated inpatients from Ireland compared with 38 healthy controls. IGT was present in 10.5% of the patients, 18.2% in unaffected relatives, and 0.0% in healthy control subjects. Verma et al. 41 studied 160 patients compared with 200 healthy controls. Patients had higher diabetes rates than in controls (8/160 vs 1/200).

Underlying Reasons for a Pre-existing Cardiovascular Risk in First Episode and Unmedicated Patients

Our findings suggest relatively low rates of MetS and metabolic risk factors in early schizophrenia and in UM patients, with one exception. UM and FE patients appear to have a high rate of smoking. UM and FE patients appear to have a low rate of hyperglycaemia (6.4% and 8.7%, respectively) when compared with 15.9% found in US adults aged 20–39 years. 39 That said several studies have found an increased risk for diabetes in first-degree relatives of patients with schiophrenia. 28 , 48 In a study of 7139 young (mean age 29.4 years) antipsychotic-naive schizophrenia patients, Nielsen et al. 37 found that, in addition to general diabetes risk factors such as age, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, diabetes is promoted in schizophrenia patients by initial and current treatment with olanzapine and mid-potency antipsychotics. A large waist size does not appear to be particularly common in UM and FE patients, but clearly can develop quickly after starting atypical antipsychotic medication. McEvoy et al. 49 demonstrated that 80% of olanzapine-treated patients had gained >7% of their baseline weight after 1 year compared with 50% of quetiapine-treated patients and 58% of risperidone-treated patients. The 1-year, open-label, randomized study (EUFEST [European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial]) of FE patients with schizophrenia or related disorder found that 86% taking olanzapine and 65% taking quetiapine gained >7% of their baseline weight. 50

A further factor not adequately explored here is that patients might have a pre-existing unhealthy lifestyle, unhealthy diet, and/or low physical fitness. 51–53 . A recent study 54 has demonstrated that those individuals who developed psychosis are more likely to be physically inactive (OR = 3.3, CI 95% 1.4–7.9 adjusted for gender, parental socio-economic status, family structure, and parents’ physical activity) and to have poor cardio-respiratory fitness (OR = 2.2, 95% CI 0.6–7.8 adjusted for parental socio-economic status, family structure, and parents’ physical activity) compared with those who did not develop psychosis. The study of Spelman et al. 40 confirms that compared with controls FE drug-naive patients take less exercise and have a diet rich in saturated fats and poor in fibers. Prodromal symptoms, which precede the first psychotic episode, may play a central role in physical inactivity as they may inhibit the tendency to make patients less active in live. 55 Overall, the interplay between genetic predisposition, an unhealthy lifestyle characterized by sedentary lifestyle or physical inactivity, a low cardio respiratory fitness, and bad eating habits and induced by prodromal symptoms are likely to result in a higher susceptibility for metabolic abnormalities and subsequently a higher cardiovascular risk profile.

Clinical Implications

Some metabolic risk factors (such as smoking) may be present soon after diagnosis but most metabolic complications will take time to develop offering an important target for prevention. Weight gain is a key target that accumulates soon after starting antipsychotic medication. Clinicians should focus on preventing initial cardio-metabolic risk because subsequent reduction in this risk is more difficult to achieve, either through behavioral or pharmacologic interventions. 56–59 From a MetS point of view, FE patients should initially receive treatment with antipsychotics possessing a low risk for metabolic side effects or be given effective weight loosing strategies if prescribing higher risk medication. All patients who start with antipsychotic treatment should also undergo routine monitoring of weight and metabolic parameters. 60 , 61 This can be achieved by establishing a risk profile based on consideration of medical factors (eg, obesity, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, hyperglycaemia, and established diabetes), but also behavioral factors (eg, poor diet, smoking, and physical inactivity). This risk profile can then be used as a basis for ongoing monitoring, treatment selection, and management. Psychiatrists should monitor and chart BMI and waist circumference of every patient regularly, regardless of the prescribed antipsychotic drug. 26 , 60–62 Psychiatrists should also encourage patients to monitor and chart their own weight. Due to potential weight-independent metabolic effects, the other MetS criteria of blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, and fasting lipid profile should also be assessed routinely, even if BMI or waist circumference are normal. Additionally, psychiatrists, physicians, nurses, and other members of the multidisciplinary team can help educate and motivate patients who start with antipsychotic treatment to improve their lifestyle through the use of effective behavioral interventions, including smoking cessation, dietary measures, and exercise. 56 , 60–66 Research suggests that behavioral interventions including physical activity and diet counseling are partially effective in attenuating antipsychotic-induced weight gain in a drug-naive FE psychosis cohort, although these gains from behavioral interventions are not always sustained a year after the intervention. 67 If lifestyle interventions do not succeed preferential use of or switching to a lower-risk medication, or addition of a medication known to reduce weight and/or metabolic abnormalities should be considered. 68 , 69

Future Research

Future studies should evaluate interventions that target emerging MetS risk factors in patients who start antipsychotic treatment. Future research should also undertake a comprehensive assessment of MetS risk factors following, at the very least, recommended monitoring guidelines. Long-term follow-up will be required in order to accurately document the emergence of some outcomes, such as diabetes. Thirdly, examining whether cardio-metabolic outcomes are moderated by clinical characteristics and genetic factors should become a clinical research priority.

Limitations

We wish to acknowledge several limitations in the primary data and this meta-analysis. First, there was considerable heterogeneity that can only be partly controlled by stratification for setting. Second, due to limited data on medicated FE patients we were not able to analyze medicated and unmedicated FE patients separately. Third, because we excluded adolescents from our analyses, mean age of our UM and FE patients was relatively high. This older age might be a potential source of bias. Fourth, there were often missing data on duration of illness. Indeed, it is important to note that duration of illness is often a proxy of duration of medication exposure which may influence MetS. Fifth, there were inadequate data on individuals prescribed specific antipsychotic agents, particularly first generation antipsychotic drugs. Sixth, there was inadequate measurement of population rates of MetS in each study, and as such relative risk estimates of MetS could only be extrapolated. Finally, there was marked variation in the quality of studies, particularly sample size.

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Pina, Psychiatry, Gregorio Marañon General University Hospital, Madrid, Spain, Jolanta Rabe-Jablonska and Tomasz Pawelczyk Department of Affective and Psychotic Disorders, Medical University of Lodz, Poland, and David Fraguas, Servicio de Salud Mental, University Hospital of Albacete, Albacete, Spain. De Hert has been a consultant for, received grant/research support and honoraria from, and been on the speakers/advisory boards of Astra Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck JA, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis. The remaining authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1. Brown S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:502–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rössler W, Salize HJ, van Os J, Riecher-Rössler A. Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:399–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, Inskip H. Twenty-five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:116–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osby U, Correia N, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Sparen P. Time trends in schizophrenia mortality in Stockholm county, Sweden: cohort study. BMJ. 2000;321:483–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Newman SC, Bland RC. Mortality in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia: a record linkage study. Can J Psychiatry. 1991;36:239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Casadebaig F, Philippe A. Mortality in schizophrenia patients. 3 years follow-up of a cohort. Encephale 1999;25:329–337 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1123–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Capasso RM, Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM, Decker PA, St Sauver J. Mortality in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: an Olmsted County, Minnesota cohort: 1950 2005. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131:101–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw P. The metabolic syndrome, a new worldwide definition. A consensus statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23:469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Expert Panel on Detection and Evaluation of Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults: Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001;285:2486–2497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005;112:2735–2752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mitchell A, Vancampfort D, Sweers K, van Winkel R, Weiping Yu, De Hert M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print December 29, 2011]. Schizophr Bull. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbr148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fakhoury WKH, Wright D, Wallace M. Prevalence and extent of distress of adverse effects of antipsychotics among callers to a United Kingdom national mental health helpline. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;6:153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Covell NH, Weissman EM, Schell B, et al. Distress with medication side effects among persons with severe mental illness. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34:435–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vancampfort D, Sweers K, Probst M, et al. The association of metabolic syndrome with physical activity performance in patients with schizophrenia. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37:318–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. De Hert M, Peuskens B, van Winkel R, et al. Body weight and self-esteem in patients with schizophrenia evaluated with B-WISE. Schizophr Res. 2006;88:222–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vancampfort D, Probst M, Scheewe T, et al. Lack of physical activity during leisure time contributes to an impaired health related quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;139:122–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weiden PJ, Mackell JA, McDonnell DD. Obesity as a risk factor for antipsychotic noncompliance. Schizophr Res. 2004;66:51–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19 (1):1–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Newcomer JW. Antipsychotic medications: metabolic and cardiovascular risk. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:8–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hasnain M, Fredrickson SK, Vieweg WV, Pandurangi AK. Metabolic syndrome associated with schizophrenia and atypical antipsychotics. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10:209–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;123:225–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Hert M, Detraux J, van Winkel R, Yu W, Correll CU. Antipsychotic medications metabolic, cardiovascular and cardiac risks. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012; 8:114–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen D, De Hert M. Endogenic and iatrogenic diabetes mellitus in drug-naive schizophrenia: the role of olanzapine and its place the psychopharmacological treatment algorithm. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2368–2369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kohen D. Diabetes mellitus and schizophrenia: historical perspective. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;47:64–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Foley DL, Morley KI. Systematic review of early cardiometabolic outcomes of the first treated episode of psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:609–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. De Hert M, Dobbelaere M, Sheridan EM, Cohen D, Correll CU. Metabolic and endocrine adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized, placebo controlled trials and guidelines for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:144–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maayan L, Correll CU. Weight gain and metabolic risks associated with antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21:517–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alvarez-Jiménez M, González-Blanch C, Crespo-Facorro B, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain in chronic and first-episode psychotic disorders: a systematic critical reappraisal. CNS Drugs. 2008;22:547–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tarricone I, Gozzi BF, Serretti A, Grieco D, Berardi D. Weight gain in antipsychotic-naive patients: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:187–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ford ES, Li C. Defining the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: will the real definition please stand up? J Pediatr. 2008;152:160–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nielsen J, Skadhede S, Correll CU. Antipsychotics associated with the development of type 2 diabetes in antipsychotic-naïve schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1997–2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. De Hert M, Schreurs V, Sweers K, et al. Typical and atypical antipsychotics differentially affect long-term incidence rates of the metabolic syndrome in first-episode patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective chart review. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999 2002. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1263–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spelman LM, Walsh PI, Sharifi N, Collins P, Thakore JH. Impaired glucose tolerance in first-episode drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia. Diabet Med. 2007;24:481–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Verma SK, Subramaniam M, Liew A, Poon LY. Metabolic risk factors in drug-naive patients with first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:997–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Graham KA, Cho H, Brownley KA, Harp JB. Early treatment-related changes in diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk markers in first episode psychosis subjects. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:287–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sengupta S, Parrilla-Escobar MA, Klink R, Fathalli F, et al. Are metabolic indices different between drug-naïve first-episode psychosis patients and healthy controls? Schizophr Res. 2008;102:329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kirkpatrick B, Miller BJ, Garcia-Rizo CG, Fernandez-Egea E, Bernardo M. Is abnormal glucose tolerance in antipsychotic-naïve patients with nonaffective psychosis confounded by poor health habits? Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(2):280–284 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Phutane VH, Tek C, Chwastiak L, et al. Cardiovascular risk in a first-episode psychosis sample: a “critical period” for prevention? Schizophr Res. 2011;127:257–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Arranz B, Rosel P, Ramírez′ N, et al. Insulin resistance and increased leptin concentrations in noncompliant schizophrenia patients but not in antipsychotic-naive first episode schizophreniapatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1335–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ryan MC, Collins P, Thakore JH. Impaired fasting glucose tolerance in first-episode, drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:284–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van Winkel R, Moons T, Peerbooms O, et al. MTHFR genotype and differential evolution of metabolic parameters after initiation of a second generation antipsychotic: an observational study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25:270–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the treatment of early psychosis: a randomized, doubleblind 52-week comparison. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1050–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al. ; EUFESTstudy group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trail. Lancet 2008;371:1085–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vancampfort D, Knapen J, Probst M, et al. Considering a frame of reference for physical activity research related to the cardiometabolic risk profile in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177:271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Strassnig M, Brar JS, Ganguli R. Nutritional assessment of patients with schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:393–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bobes J, Arango C, Garcia-Garcia M, Rejas J. Healthy lifestyle habits and 10-year cardiovascular risk in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: an analysis of the impact of smoking tobacco in the CLAMORS schizophrenia cohort. Schizophr Res. 2010;119:101–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Koivukangas J, Tammelin T, Kaakinen M, et al. Physical activity and fitness in adolescents at risk for psychosis within the Northern Finland 1986 Birth Cohort. Schizophr Res. 2010;116:152–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Juutinen J, Hakko H, Meyer-Rochow VB, Räsänen P, Timonen M;The STUDY-70 Research Group. Body mass index (BMI) of drug-naïve psychotic adolescents based on a population of adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:521–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. De Hert M, Schreurs V, Vancampfort D, van Winkel R. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: a review. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:15–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Correll CU. Balancing efficacy and safety in treatment with antipsychotics. CNS Spectr. 2007;12:12–20–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ryan M, Thakore J. Physical consequence of schizophrenia and its treatment: the metabolic syndrome. Life Sci. 2002;71:239–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1334–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. De Hert M, Vancampfort V, Correll C, et al. A systematic evaluation and comparison of the guidelines for screening and monitoring of cardiometabolic risk in people with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mitchell AJ, Delaffon V, Vancampfort D, Correll CU, De Hert M. Guideline concordant monitoring of metabolic risk in people treated with antipsychotic medication: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening practices. Psychol Med. 2012;42:125–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. De Hert M, Cohen D, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, and recommendations at the system and individual levels. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:138–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Van Gaal LF. Long-term health considerations in schizophrenia: metabolic effects and the role of abdominal adiposity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16:142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. De Hert M, Dekker JM, Wood D, Kahl KG, Holt RI, Möller HJ. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:412–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vancampfort D, Knapen J, De Hert M, et al. Cardiometabolic effects of physical activity interventions for people with schizophrenia. Phys Ther Rev. 2009;14:388–398 [Google Scholar]

- 66. De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:52–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Alvarez-Jimenez M, Gonzalez-Blanch C, Vazquez-Barquero JL, et al. Attenuation of antipsychotic-induced weight gain with early behavioral intervention in drug-naive first-episode psychosis patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1253–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mukundan A, Faulkner G, Cohn T, Remington G. Antipsychotic switching for people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic-induced weight or metabolic problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;12:CD006629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Ring KD, et al. Schizophrenia Trials Network: a randomized trial examining the effectiveness of switching from olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone to aripiprazole to reduce metabolic risk: comparison of antipsychotics for metabolic problems (CAMP). Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:947–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]