Abstract

Background: Cannabis use has been identified as a potent predictor of the earlier onset of psychosis, but meta-analysis has not indicated that it has a clear effect in established psychosis. Aim: To assess the association between cannabis and outcomes, including whether change in cannabis use affects symptoms and functioning, in a large sample of people with established nonaffective psychosis and comorbid substance misuse. Methods: One hundred and sixty participants whose substance use included cannabis were compared with other substance users (n = 167) on baseline demographic, clinical, and substance use variables. The cannabis using subgroup was examined prospectively with repeated measures of substance use and psychopathology at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. We used generalized estimating equation models to estimate the effects of cannabis dose on subsequent clinical outcomes and whether change in cannabis use was associated with change in outcomes. Results: Cannabis users showed cross-sectional differences from other substances users but not in terms of positive symptoms. Second, cannabis dose was not associated with subsequent severity of positive symptoms and change in cannabis dose did not predict change in positive symptom severity, even when patients became abstinent. However, greater cannabis exposure was associated with worse functioning, albeit with a small effect size. Conclusions: We did not find evidence of an association between cannabis dose and psychotic symptoms, although greater cannabis dose was associated with worse psychosocial functioning, albeit with small effect size. It would seem that within this population, not everyone will demonstrate durable symptomatic improvements from reducing cannabis.

Keywords: psychosis, schizophrenia, cannabis, substance use, dual diagnosis, positive symptoms

Introduction

Cannabis is the most commonly used illegal substance in many countries. Over the last 15 years, reports indicate that people with a schizophrenia diagnosis have higher rates of use than the general population: a recent meta-analysis1 of 35 studies from 16 countries estimated the median lifetime rate of cannabis use disorders was 27.1% for this patient group compared with consistent general population lifetime prevalence estimates of 8%. This high rate of use is a cause for concern, not least because cannabis is purported to have an etiological role in psychosis: Cannabis is identified in prospective cohort studies as an independent risk factor for the development of psychosis2 and in retrospective studies3,4 as a risk factor for earlier onset.

It is hypothesized that neurobiological changes induced by Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) are implicated in the development of psychotic symptoms in individuals with genetic vulnerability.5 Whether exposure to the drug continues to have a negative impact on clinical outcomes for those with existing psychosis is the key question this article aims to address. A recent systematic review examining this issue6 included only studies with longitudinal designs (eliminating cross-sectional studies where the direction of causation cannot be determined), where cannabis was measured at a time prior to the outcomes and there was a comparison group with non-cannabis using controls. The authors concluded from 13 studies that while cannabis use was consistently associated with increased rates of hospitalization7,8 and relapse,8–11 evidence for links with psychotic or other specific symptoms was less consistent. Three studies from the review9,12,13 and a further recent study14 found changes in cannabis status/use over time associated with severity of some positive psychotic symptoms, while 2 studies8,15 found no such associations.

These inconsistencies may be attributable to methodological issues, including the failure to adjust for potential confounds which include factors known to be associated both with poor outcome and with cannabis use, such as gender, sociodemographics, poor service engagement, and medication adherence.6 Alcohol and other drugs in addition to cannabis are associated with detrimental mental health outcomes, and because polysubstance use is common in this client group,16 if this is not controlled in the analysis, it may result in an overestimation of cannabis effects. Additionally, most studies also do not control for baseline illness symptom severity; hence, associations between cannabis and outcomes due to symptoms causing cannabis use cannot be excluded.

This study examines the association between cannabis use and symptom, functioning, relapse, and hospital admission outcomes in people with established psychosis. It overcomes the major limitations of previous studies by employing a longitudinal design, with repeated and time-lagged measures of psychopathology, use of cannabis, alcohol, and other substances, and adjusting for a wide range of potential confounds.

We tested a number of hypotheses in relation to the association between cannabis dose and positive symptoms and other secondary outcomes. First, we predicted that people whose substance use includes cannabis will have more positive psychotic symptoms than people who only use other illicit drugs or alcohol. Second, that within the subgroup of cannabis users, greater cannabis dose is associated with higher positive psychotic symptoms. Third, change in cannabis dose will be associated with change in positive symptoms, after adjusting for potential confounds and antecedent symptom severity.

Methods

Participants and Design

Three hundred and twenty-seven patients with a clinical diagnosis of nonaffective psychotic disorder (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision [ICD-10] and/or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [DSM-IV]) and a DSM-IV diagnosis of drug and/or alcohol dependence or abuse were recruited during a randomized, controlled single blind trial of a psychological intervention17 where participants received either treatment as usual (TAU; n = 164) or motivational interviewing and cognitive behavior therapy (MI–CBT; n = 163). Inclusion criteria were age over 16 years, in current contact with mental health services, meeting minimum levels of substance misuse on at least 6 of the last 12 weeks (alcohol: exceeding 28 units for men and 21 units for women; illicit drug use: use on at least 2 days/week), no significant history of organic factors implicated in the etiology of psychotic symptoms, English speaking, and having a fixed abode (including B&B or hostel).

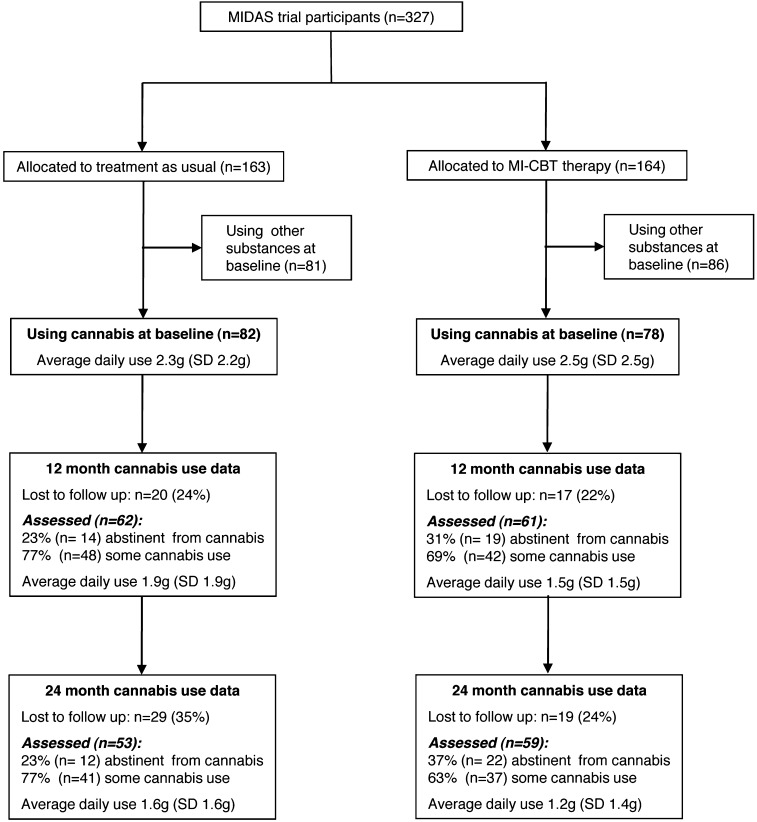

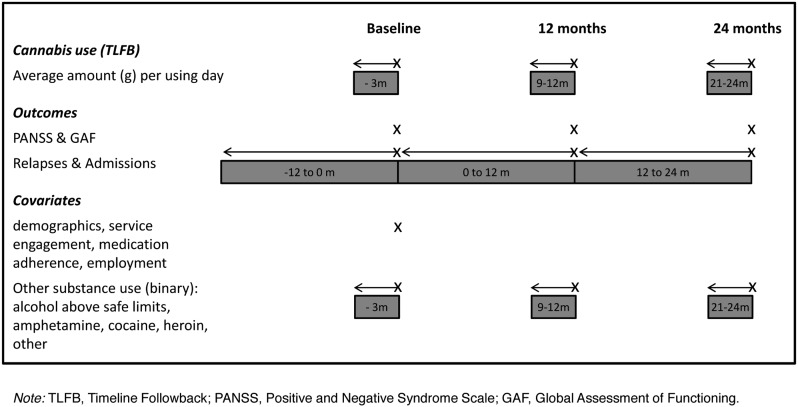

After receiving a complete description of the study, participants provided written informed consent. The study obtained ethics approval (reference 03/5/045) from the Cambridgeshire 4 Research Ethics Committee, UK. Of the 327 participants, 160 (49%) reported using cannabis in the 90 days prior to baseline, 78 (49%) of whom were allocated to the psychological therapy and 82 (51%) to usual treatment. Figures 1 and 2 show the design and measurement intervals of the study.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing attrition, abstinence from cannabis, and average daily cannabis use for the subgroup of baseline cannabis users.

Fig. 2.

Repeated assessment of cannabis use, outcomes, and covariates.

Measures

Covariates.

In addition to treatment allocation (MI–CBT vs TAU), the following baseline measures (see table 1) were included as covariates in all adjusted analyses: self-reported demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, employment, college or university higher education, and whether living with partner or family), Service Engagement Scale total score (SES, assessing client availability, collaboration, help-seeking, and treatment adherence),18 and compliance with prescribed antipsychotic medication (Drug Attitude Inventory; DAI).19 Additionally, 5 binary variables were entered as time-dependent covariates (baseline, 12 months, and 24 months) to adjust for use of substances other than cannabis, grouped as follows: amphetamines, cocaine, heroin, other illicit drugs, alcohol use above safe limits (exceeding 4 units on average per drinking day for men, 3 for women). Binary variables were used for substance use covariates to ensure linearity with the clinical outcomes.

Table 1.

Demographic, Psychiatric History, and Baseline Substance Use Variables in the Full Sample and 2 Subgroups: Those Using Cannabis (C+) and Those Using Substances Other Than Cannabis (C−) at Baseline

| Full Sample (N = 327) | C+ Group (N = 160) | C− Group (N = 167) | Comparison (C+ vs C−) | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | Χ2 | P | |

| Age in years, mean (SD), t | 37.9 (9.7) | 35.2 (9.5) | 40.4 (9.1) | 5.08 | <0.001a |

| Gender: male | 283 (86.5) | 141 (88.1) | 142 (85.0) | 0.67 | 0.412 |

| Living arrangements | |||||

| Alone/house share/hostel | 229 (70.0) | 116 (72.5) | 113 (67.7) | 0.91 | 0.340 |

| With partner or family | 98 (30.0) | 44 (27.5) | 54 (32.3) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 266 (81.4) | 114 (71.3) | 152 (91.0) | 21.04 | <0.001a |

| Black/Asian/other | 61 (18.7) | 46 (28.8) | 15 (9.0) | ||

| Attended higher education | 101 (30.9) | 43 (26.9) | 58 (34.7) | 2.25 | 0.134 |

| Employment | |||||

| Unemployed/retired | 305 (93.3) | 149 (93.1) | 156 (93.4) | 0.74 | 0.689 |

| Employed/self-employed | 12 (3.7) | 5 (3.1) | 7 (4.2) | ||

| Student | 10 (3.1) | 6 (3.8) | 4 (2.4) | ||

| Years of psychosis, mean (SD), t | 12.2 (9.2) | 10.3 (7.9) | 14.0 (10.1) | 3.62 | 0.003b |

| Primary clinical diagnosis | |||||

| Schizophrenia | 267 (81.7) | 130 (81.3) | 137 (82.0) | 0.68 | 0.878 |

| Schizophreniform | 4 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Schizoaffective disorder | 27 (8.3) | 12 (7.5) | 15 (9.0) | ||

| Psychosis NOS | 29 (8.9) | 16 (10.0) | 13 (7.8) | ||

| SES total score, mean (SD), t | 12.4 (6.9) | 13.0 (6.9) | 12.0 (6.9) | −1.26 | 0.895 |

| AOT or dual diagnosis service | 24 (7.3) | 10 (6.3) | 14 (4.3) | 0.57 | 0.450 |

| Compliant with medication (DAI) | 271 (82.9) | 124 (77.5) | 147 (88.0) | 5.47 | 0.019a |

| Medication dose (chlorpromazine equivalent in milligrams), mean (SD), t | 431.9 (326.8) | 442.4 (347.8) | 422.3 (307.0) | −0.53 | 0.595 |

| Baseline PANSS, mean (SD), t | |||||

| Positive | 16.0 (5.3) | 16.2 (5.9) | 15.9 (4.7) | −0.47 | 0.640 |

| Negative | 14.0 (4.5) | 13.3 (4.1) | 14.7 (4.7) | 2.86 | 0.005a |

| General | 32.4 (7.8) | 31.8 (7.3) | 33.1 (8.3) | 1.54 | 0.124 |

| Baseline GAF total, mean (SD), t | 34.3 (8.9) | 34.4 (10.3) | 34.1 (7.4) | −0.32 | 0.640 |

| Relapsed (in 12months pre-baseline) | 122 (37.3) | 71 (44.4) | 51 (30.5) | 7.00 | 0.008c |

| Admitted (in 12months pre-baseline) | 78 (23.9) | 50 (31.3) | 28 (16.8) | 9.49 | 0.002c |

| Other substances used | |||||

| Alcohol (above safe limits) | 258 (78.9) | 106 (66.3) | 152 (91.0) | 30.11 | <0.001a |

| Amphetamines | 44 (13.5) | 29 (18.1) | 15 (9.0) | 5.87 | 0.015c |

| Heroin | 32 (9.8) | 18 (11.3) | 14 (8.4) | 0.76 | 0.383 |

| Cocaine | 27 (8.3) | 22 (13.8) | 5 (3.0) | 12.48 | <0.001c |

| Ecstasy | 17 (5.2) | 16 (10.0) | 1 (0.6) | 14.65 | <0.001d |

| Benzodiazepines | 17 (5.2) | 7 (4.4) | 10 (6.0) | 0.43 | 0.511 |

Note: Descriptive statistics are N (%), and inferential statistic is Χ2 unless otherwise specified. SES, Service Engagement Scale; AOT, assertive outreach team; DAI, Drug Attitude Inventory; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning.

Included in multivariable model and significant (P < .05), retained in final model after backwards elimination.

Not included in multivariable model, highly correlated with age.

Included in multivariable model but not significant (P > .05), dropped from final model after backwards elimination.

Not offered to multivariable model as only 1 ecstasy user present in C− group.

Substance Use.

Frequency (percentage days used) and average daily weight (grams) of cannabis were assessed for 3 months preceding baseline, 12-, and 24-month clinical measures using the Timeline Followback (TLFB) method.20 At each assessment, participants were asked to report all use per day during the previous 90 days. The TLFB has good reported reliability and validity in dual diagnosis populations,21–23 including the current sample17 where hair analysis (for drug use) and collateral use reports (drug and alcohol) showed good agreement with the self-reports from the TLFB.

Clinical Measures.

Assessments took place at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months and were conducted by trained assessors who were blinded to the treatment allocation:

Symptoms: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)24 was used to assess positive, negative, and general psychotic symptoms in the previous week. All trained raters assessed 10 ‘gold standard’ PANSS video-recorded interviews prior to study ratings with mean intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) across all assessors in the range 0.85–0.89. Random rating checks on 24 recorded study interviews showed ICCs in the range 0.70–0.76.

Functioning was assessed using the total score of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF),25 with ICC of 0.70.

Case notes were used to assess hospital admissions and relapse in the previous 12 months, relapse being defined as a psychotic symptom exacerbation longer than 2 weeks and requiring patient management change (medication and/or increased clinical team observation including hospitalization). Inter-rater reliability was excellent (mean ICCs: admission [yes/no] 0.98 and relapse [yes/no] 0.87). Case notes were also used to assess antipsychotic medication at baseline (type and dose), and this information was transferred into chlorpromazine equivalence in milligrams.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses used Stata version 11.1.26 First, we split all participants into people whose substance use included cannabis (C+ group) and those who used other substances but not cannabis (C− group) in the 90 days prior to baseline and compared these groups on all assessed baseline demographic, clinical, and substance use variables (all variables in table 1) using t-tests or chi-square tests as appropriate. Any significant variables in the initial univariable analyses (P < .1) were considered for inclusion in a multivariable logistic model with cannabis group (C+ or C−) as outcome, which was formulated using a backwards elimination procedure.

Second, in the subgroup of baseline cannabis users, we used the measurement-lag in the TLFB (figure 2) to estimate the effect of cannabis use (grams/day, average in previous 90 days) on subsequent clinical outcomes for symptoms and functioning. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were used to produce an average estimate of the linear correlation between amount of cannabis per using day and each outcome across all 3 time periods (baseline, 12 months, and 24 months) taking the within-subject correlation into account.27,28 For relapses and hospital admissions (yes/no in previous 12 months), the effect of cannabis use in the 90 days prior to the relevant 12-month period was examined, and GEE analysis was used to combine the effects observed at 12 and 24 months. All analyses were performed first without adjusting for covariates and then with adjustment for the baseline and time-varying covariates listed previously. Following the adjusted analysis, a sensitivity analysis for possible colinearity was performed by examining variance inflation factors and repeating the adjusted analysis after removal of covariates with VIF greater than 5.

Third, to examine whether change in cannabis use was associated with change in the mean of the clinical outcomes, we used the GEE models as described above but with the inclusion of the clinical outcome from previous assessment and cannabis use from the 12 months previously both entered as additional covariates (ie, a lagged response and lagged covariate model). An equivalent approach using change scores (change from assessment 12 months ago) was also performed and gave similar results (not shown).

GEE models were appropriate because cannabis use and the clinical outcomes were time-dependent variables and exhibit serial autocorrelation between assessment points. The regression coefficients from these models can be interpreted as in a standard linear or logistic regression, where having a 1g increase in the amount of cannabis per using day (equivalent to 2 joints) is associated on average with having higher or lower outcomes corresponding to the coefficients reported in tables 2 and 3. We used an exchangeable correlation matrix to model the serial autocorrelation over time and estimated robust standard errors to allow for potential misspecification of the working correlation matrix. The GEE approach uses all available data, which allows for nonmonotonic missingness as found in our study. The total number of observations in the model becomes the total number of observed outcomes and predictors on all participants in the subgroup at each study assessment point and so varies according to outcome being analyzed. In addition, the adjusted analysis has fewer observations when there is also additional missingness in the independent variables. The number of participants and observations included in the unadjusted and adjusted models are shown with the results in tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes in the Cannabis Using Subsample and Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) Estimates of Association With Average Daily Weight (Grams) of Cannabis Used in Previous 90 Days

| Dependent Variable | Baseline | 12 Months | 24 Months | Coefficient Estimated Using GEE Model | |||||||

| Total N | Mean | SD | Total N | Mean | SD | Total N | Mean | SD | Unadjusted (95% CI) | Adjusted (95% CI) | |

| PANSS positive | 160 | 16.2 | 5.9 | 132 | 14.7 | 5.4 | 120 | 14.0 | 5.4 | 0.12 (−0.09 to 0.34) | 0.07 (−0.21 to 0.34) |

| PANSS negative | 160 | 13.3 | 4.1 | 132 | 12.8 | 3.9 | 120 | 12.2 | 3.9 | 0.01 (−0.13 to 0.15) | 0.12 (−0.05 to 0.29) |

| PANSS general | 160 | 31.8 | 7.3 | 132 | 28.4 | 7.1 | 119 | 26.1 | 7.0 | 0.24 (−0.05 to 0.53) | 0.28 (−0.01 to 0.57) |

| GAF total | 158 | 34.4 | 10.3 | 130 | 35.5 | 10.8 | 115 | 36.4 | 11.3 | −0.44* (−0.87 to −0.02) | −0.38 (−0.83 to 0.07) |

| Total N | N | (%) | Total N | N | (%) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Relapsed (past 12 months) | –– | –– | –– | 157 | 42 | 26.8 | 157 | 36 | 22.9 | 1.00 (0.89–1.13) | 0.95 (0.81–1.12) |

| Admitted (past 12 months) | –– | –– | –– | 159 | 33 | 20.8 | 158 | 28 | 17.7 | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) | 0.91 (0.74–1.11) |

Note: PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; numbers of cannabis users assessed at each time point are shown in figure 1.

*P < .05.

Table 3.

Effect of Change in Average Daily Weight (Grams) of Cannabis on Change in Symptoms

| Dependent Variable | Analysis Adjusting for Previous Cannabis Use and Symptomsa | Analysis Adjusting for Previous Cannabis Use, Symptoms, and Covariatesb | ||

| Coefficient (95% CI); N (obs)c | P Value | Coefficient (95% CI); N (obs)c | P Value | |

| PANSS positive | 0.12 (−0.24 to 0.49); 119 (209) | 0.51 | 0.02 (−0.40 to 0.43); 108 (175) | 0.93 |

| PANSS negative | 0.09 (−0.20 to 0.37); 120 (211) | 0.55 | 0.18 (−0.14 to 0.51); 109 (177) | 0.26 |

| PANSS general | 0.28 (−0.15 to 0.72); 120 (210) | 0.20 | 0.23 (−0.24 to 0.70); 109 (176) | 0.33 |

| GAF total | −0.91 (−1.68to−0.14); 117 (200) | 0.02 | −1.05 (−1.91to−0.18); 106 (169) | 0.02 |

Note: Numbers of cannabis users assessed at each time point are shown in figure 1.

At assessment 12 months previously.

Covariates as listed previously: age, gender, employment, living stable, ethnicity, trial arm, higher education, DAI compliant, service engagement scale, problem alcohol use, amphetamine use, heroin use, cocaine use, and other drug use.

N refers to the number of participants included in the model and obs refers to the number of observations included in the model (repeated within participant).

Results

Baseline Cross-Sectional Comparison: How Do Cannabis Users Differ From Other Substance Users?

Of the 327 participants, 160 (49%) reported using cannabis in the 90 days prior to baseline, the most common other substance being alcohol use above safe limits (n = 258, 79%), followed by amphetamines, heroin, cocaine, ecstasy, and benzodiazepines (table 1). Contrary to our first hypothesis, cannabis users did not differ from other substance users in terms of positive psychotic symptoms. However, there were differences (P < .1) between groups in terms of 11 other baseline variables (table 1). Two factors associated with cannabis use (years of psychosis and ecstasy use) were not included in the multivariable model because the effect of years of psychosis is highly correlated with the participant’s age and due to there being too few ecstasy users in the C− sample. Four of the remaining 9 variables were dropped following a backward elimination procedure (amphetamine use, cocaine use, admission pre-baseline, and relapse pre-baseline). The final significant multivariable model (P < .001) with pseudo R 2 = .206, indicated that cannabis users were younger (P < .001), less likely to use alcohol above safe limits (P < .001), more likely to be of black or Asian ethnicity (P = .001), more likely to be noncompliant with antipsychotic medication (P = .022), and had less negative symptoms (P = .003).

The Cannabis Using Subgroup: Amount and Stability of Use

Of the 160 baseline cannabis users, 101 (31%) met DSM-IV criteria for cannabis dependence (n = 84) or abuse (n = 17). The mean frequency of cannabis use was 59% (SD 36%), equating to using approximately 4 days/week; the average cannabis consumed per using day was 2.4g (SD 2.4g), equating to approximately 5 joints. Reductions in average daily cannabis consumed were found in 60% (72/120) of baseline cannabis users at 12 months and 67% (73/109) at 24 months. Figure 1 shows the patterns of attrition, abstinence, and average daily cannabis use across assessments for the cannabis using subgroup. Moderate correlations were found between baseline and 12-month reports of average daily use (Spearman’s ρ = 0.31, P < .01) and between 12- and 24-month reports (ρ = 0.53, P < .01). Here and elsewhere, analyses were repeated using frequency of use and total weight as cannabis variables, but the pattern of results did not differ and are not presented.

Is Cannabis Dose Related to Clinical Outcomes in the Cannabis Using Subgroup?

Positive Symptoms.

There was no statistically significant association between average daily weight (grams) of cannabis and the PANSS positive subscale in either the unadjusted or the adjusted analysis (table 2). Having a 1g increase in cannabis is associated with only a 0.12 increase on the PANSS positive scale.

Other Symptoms and General Functioning.

There was no significant association between cannabis dose and the PANSS negative and general subscales. Average daily weight of cannabis was significantly associated with GAF total in unadjusted but not in adjusted analyses (table 2).

Hospital Admissions and Relapse.

Rates of hospital admission and relapse during two 12-month periods (baseline to 12 months and 12–24 months) are provided in table 2. Average daily weight (grams) of cannabis was not significantly associated with admission or occurrence of relapse in the subsequent 12-month period.

Treatment Allocation and Sensitivity Analysis.

We examined the coefficient of randomized treatment allocation in all adjusted models but found that it did not significantly predict outcome in any analysis (coefficients not shown). Following inspection of the variance inflation factors, 3 variables were found to have values larger than 5 (age, gender, and higher education). All adjusted analyses were repeated excluding these variables, and the significance of the cannabis dose re-examined. Though the coefficient values vary, there were no changes to statistical significance of the coefficient of cannabis dose for any outcome (results not shown).

Does Change in Cannabis Dose Predict Change in Positive Symptoms or Other Outcomes?

Table 3 shows the results when adjusting for cannabis use and symptoms at the previous time point and demonstrates that change in cannabis dose did not significantly predict change in symptoms on the PANSS positive subscale. Similarly, change in cannabis dose did not significantly predict change in scores on the PANSS negative or general subscales. However, change in cannabis use did significantly predict change in GAF total score (table 3), with an increase in cannabis use associated with worse functioning, albeit with a small effect size. The coefficient in table 3 indicates that increasing average daily weight of cannabis by 1 g was associated with a decrease of just 1.05 in the GAF total score.

We found that the coefficient for random treatment allocation was statistically significant for PANSS general in the adjusted analysis (coefficient = −1.71, 95% CI −3.03 to −0.38) but not for GAF total score, implying that the significant findings of cannabis dose is not because of a direct effect of allocation. As previously, after examining the variation inflation factors, we repeated the adjusted analysis excluding age, gender, and higher education as covariates; there were no changes to statistical significance of the coefficient of cannabis dose for any outcome (results not shown).

Exploratory Post Hoc Analyses

Given the null results found in the majority of planned analyses, we explored the possibility that dose reduction in established psychosis may only be of significant clinical consequence when there is complete abstinence. However, our additional analyses did not support the hypothesis that abstinence from cannabis was associated with change in subsequent clinical outcomes (results not shown).

Discussion

In this study of people with established psychosis, all of whom used a range of substances, we found no evidence of a specific association between cannabis consumption and positive psychotic symptoms. Cannabis users differed from non-cannabis users in terms of younger age, more non-white ethnicity, less medication compliance, less alcohol use above safe limits, and less negative symptoms but not in terms of positive symptoms. In our longitudinal analyses, we did not find an association between dose of cannabis and subsequent severity of positive symptoms nor between change in cannabis dose and change in severity of positive symptoms, even when patients became abstinent. Positive symptoms overall did not show a temporal relationship with cannabis use in these analyses, and consistent with this finding, we found no statistically significant effects of cannabis dose on either relapse of psychotic symptoms or admission to hospital. However, we did find that greater cannabis exposure was associated with worse functioning, albeit with a small effect size.

The social contexts of different substances vary29 and likely underlie the differences in age and ethnicity of the cannabis users relative to other substance users in our sample. These are in accord with previous studies: within people with psychosis using substances, cannabis users tend to be younger,30 and alcohol users are more likely to be white than non-alcohol users,29 explaining the ethnicity bias. A number of previous studies have reported that people with psychosis who use cannabis have less negative symptoms than others,31 but as with our results, most studies indicate that cannabis does not impact on negative symptoms for better or worse.6 While cannabis users were more likely to be noncompliant with antipsychotic medication relative to other substance users in the pre-baseline year, this association was not related to more psychopathology than seen in other substance users. Although baseline cannabis users were more likely to have relapsed or been admitted pre-baseline, these cross-sectional effects did not remain significant in the multivariable model.

Previous studies have had inconsistent findings as regards the links between cannabis use and psychotic symptoms in established psychosis. Four studies using time-lagged designs have concluded that there are associations between cannabis use and positive symptoms in this patient group,9,12–14 but methodological differences may at least partly explain the inconsistent research findings and support the integrity of our findings. First, our sample of participants with exposure to cannabis was much larger than in these 4 prior studies, with the largest sample being 69.13 Second, these previous studies were unable to adequately examine the impact of the dose of cannabis, with amount of use not specified12 or relatively small.13,14 While all 4 studies attempted to adjust for some potentially confounding demographic variables and 3 studies adjusted for baseline severity measures and other substance use,9,13,14 none adjusted for such a comprehensive range of factors as in the current study, including the full range of other substances used at each of the 3 time points.

Differences in statistical methodology may also account for the differences in findings. For example, the structural equation modeling approach used by Foti and colleagues14 to assess bidirectional effects used a simple binary classification of participants (users and non users) to predict future symptoms over varying time intervals, whereas in the current study, we were able to take account of the dose of cannabis. Some studies also had very long timeframes (extending to 6 years) and estimates of effects of cannabis use on symptom severity may therefore have been less reliable. Grech and colleagues’ study12 categorized participants into 4 disjoint groups (cannabis use at baseline and follow-up, baseline only, follow-up only, and no use), with the majority not using cannabis at either time point. The cannabis using groups were then compared with the nonusing reference group in terms of a single binary categorization of their “usual severity of positive symptoms”’ for the whole 4-year follow-up period. We would argue that this essentially cross-sectional analysis tells us little about the temporal relationship between cannabis use and positive psychotic symptoms.

We believe our modeling approach, comparable to that of Degenhardt et al13 but focusing on a dose-response relationship between amount of cannabis per using day and symptom severity, provides a more informative and reliable analysis than previous studies. The study used the measurement lag in the continuous cannabis measure to predict symptom severity at each time point, averaging the effects over the 3 equally spaced time periods and including all available observed data in the analysis. Moreover, we were able to use the optimum design to examine temporal relationships: by covarying previous cannabis use and previous symptoms in our analysis, we were able to examine whether change in cannabis use predicts change in psychotic symptoms. Although Hides and colleagues9 assessed the effect of frequency of cannabis use on time to relapse of positive symptoms, they did not include previous cannabis use as a covariate meaning that their analysis did not enable direct examination of the effect of changes in cannabis use on changes in symptoms.

In addition to these methodological and statistical differences, certain characteristics of our sample may contribute to the differences in findings from previous studies. First, with respect to the first analysis, it is worth emphasizing that the non-cannabis using comparison group were also substance users and all met abuse or dependence criteria for at least 1 substance (mainly alcohol). The cannabis using subgroup was not exclusively cannabis users, but many also used other substances, which is why we choose to adjust for other substance use in analyses. It should also be noted that levels of cannabis use in the current study were high relative to previous studies. Our sample was also older in age and consisted mainly of people with long established psychosis in contrast with the young, recent onset groups seen in the majority of previous studies, including the 4 referred to above. It may be the case that cannabis has already had an impact on positive symptoms and that either the consequences are no longer reversible and/or that ceiling effects are now operating such that further increases in consumption are not evident in subsequent repeated measurement of symptoms. Indeed, the absolute changes in cannabis observed in our sample over time were relatively small and may not have been sufficient to have a detectable impact on the positive symptoms measure. It is also possible that there were quantitatively different subgroups with different trajectories that are not distinguished when examining population-level effects. Future studies could investigate this possibility in more depth.

As outlined above, the current study went a long way to address the shortcomings of previous research. These advantages of the study notwithstanding, some limitations need to be considered in interpreting the findings. Although our study had the advantage of analyzing frequency and weight of cannabis consumed, we did not assess the type of cannabis, specifically whether “skunk” or resin was used which have differing THC content.32 Additionally, we only examined relatively long-term and durable consequences of cannabis; transient effects lasting perhaps hours or days were not the focus of this study. Nor did we have comparative data with a non substance using sample. Most importantly, as noted above, the effect sizes of symptom changes may be small. Despite having a substantially larger sample of people with established psychosis using cannabis than previous published longitudinal research, the study may have lacked statistical power to detect significant effects from the drug use, particularly as regards investigating the consequences of cannabis abstinence where numbers were low. Finally, despite adjusting for more covariates than previous studies, no doubt there remain further unmeasured confounds that we did not consider.

Although the sample for this study was derived from a large randomized clinical trial, our aim here was not to investigate the causal effect of randomized treatment allocation on outcome, which has been reported elsewhere.17 Interesting questions remain as to whether baseline subgroups of different substances moderate such an effect, or whether the amount of cannabis use, and amount of substance use overall, act as mediating variables on the causal pathway between random treatment allocation and outcomes; we will investigate these in future studies. Instead, we investigated specifically whether or not the amount of cannabis use was associated with positive and other clinical symptoms as had been highlighted in the extant literature, using the repeated measures of substance use and symptoms collected from the Motivational Interventions for Drug and Alcohol misuse in Schizophrenia (MIDAS) trial.

In conclusion, although we found no association between cannabis use and psychotic symptoms, greater exposure to the drug resulted in the important finding of worse GAF outcomes, albeit that the effect size was small. The GAF is a measure of overall psychosocial functioning. Our finding may indicate that in this group of patients, cannabis does not have specific effects but rather its impacts vary and hence are not detectable on specific symptom measures used in this study. As noted above, there may have been substantial variation in the relationship between cannabis consumption and outcome in subgroups of the cannabis users, and we would suggest that for some people with established psychosis, the continued effects of cannabis are likely to be much more closely related to the course of psychosis than for others. While not everyone will demonstrate durable symptomatic improvements from cutting down or abstaining from cannabis, there are significant negative impacts from cannabis use in terms of physical health33 and risk of other mental health problems34 and associated problems such as medication nonadherence may be easier to address once cannabis use has been reduced. Hence, our results do not challenge the current clinical advice that cannabis reduction is likely to have overall beneficial effects on patient well-being.

Funding

United Kingdom Medical Research Council (GO200471); United Kingdom Department of Health MRC Career Development Award in Biostatistics (G0802418 to R.E.).

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants and the staff who facilitated recruitment. We are also grateful to all the collaborating NHS trusts, research assistants, and therapists. Trial registration: Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN14404480. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1.Koskinen J, Lohonen J, Koponen H, Isohanni M, Miettunen J. Rate of cannabis use disorders in clinical samples of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2009;36:1115–1130. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental heath outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Compton MT, Ramsay CE. The impact of pre-onset cannabis use on age at onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms. Prim Psychiatr. 2009;16:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Large M, Sharma S, Compton MT, Slade T, Nielssen O. Cannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: a systematic meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:555–561. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.5. First published on February 7, 2011. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Os J, Bak M, Hanssen M, Bijl R, de Graaf R, Verdoux H. Cannabis use and psychosis: a longitudinal population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:319–327. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zammit S, Moore THM, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Effects of cannabis use on outcomes of psychotic disorders: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:357–363. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caspari D. Cannabis and schizophrenia: results of a follow-up study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;249:45–49. doi: 10.1007/s004060050064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arias Horcajadas F, Sanchez Romero SS, Padin Calo J. Relevance of drug use in clinical manifestations of schizophrenia [Spanish] Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2002;30:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hides L, Dawe S, Kavanaugh DJ, Young RM. Psychotic symptom and cannabis relapse in recent-onset psychosis: prospective study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:137–143. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.014308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wade D, Harrigan S, Edwards J, Burgess PM, Whelan G, McGorry PD. Substance misuse in first-episode psychosis: 15-month prospective follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:229–234. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez-Arevalo MJ, Calcedo-Ordonez A, Varo-Prieto JR. Cannabis consumption as a prognostic factor in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164:679–681. doi: 10.1192/bjp.164.5.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grech A, Van Os J, Jones PB, Lewis SW, Murray RM. Cannabis use and outcome of recent onset psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Degenhardt L, Tennant C, Gilmour S, et al. The temporal dynamics of relationships between cannabis, psychosis and depression among young adults with psychotic disorders: findings from a 10-month prospective study. Psychol Med. 2007;37:927–934. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707009956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foti DJ, Kotov R, Guey LT, Bromet EJ. Cannabis use and the course of schizophrenia: 10-year follow-up after first hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;167:987–993. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09020189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stirling J, Lewis S, Hopkins R, White C. Cannabis use prior to first onset psychosis predicts spared neurocognition at 10-year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2005;75:135–137. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, et al. Substance use and psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia among new enrollees in the NIMH CATIE study. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1110–1116. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrowclough C, Haddock G, Wykes T, et al. Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy for people with psychosis and comorbid substance misuse: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c6325. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tait L, Birchwood M, Trower P. A new scale (SES) to measure engagement with community mental health services. J Ment Health. 2002;11:191–198. doi: 10.1080/09638230020023570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13:177–183. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carey KB. Reliability and validity of the time-line follow-back interview among psychiatric outpatients: a preliminary report. Psychol Addict Behav. 1997;11:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Temporal stability of the timeline followback interview for alcohol and drug use with psychiatric outpatients. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:774–781. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stasiewicz PR, Vincent PC, Bradizza CM, Connors GJ, Maisto SA, Mercer ND. Factors affecting agreement between severely mentally ill alcohol abusers' and collaterals' reports of alcohol and other substance abuse. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:78–87. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), 4th Edition. Washington, DC: : American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.StataCorp. Intercooled Stata Statistical Software: Release 11.1. College Station, TX:: Stata Corporation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data-analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Twisk J. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis for Epidemiology: A Practical Guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles H, Johnson S, Amponsah-Afuwape S, Leese M, Finch E, Thornicroft G. Characteristics of subgroups of individuals with psychotic illness and a comorbid substance use disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:554–561. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kavanagh DJ, Waghorn G, Jenner L, et al. Demographic and clinical correlates of comorbid substance use disorders in psychosis: multivariate analyses from an epidemiological sample. Schizophr Res. 2004;66:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Compton MT, Broussard B, Ramsay CE, Stewart T. Pre-illness cannabis use and the early course of nonaffective psychotic disorders: associations with premorbid functioning, the prodrome, and mode of onset of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2010;126:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potter DJ, Clark P, Brown MB. Potency of Δ-9-THC and other cannabinoids in cannabis in England in 2005: implications for psychoactivity and pharmacology. J Forensic Sci. 2008;53:90–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374:1383–1391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson TH. Cannabis use and mental health: a review of recent epidemiological research. Int J Pharmacol. 2010;6:796–807. [Google Scholar]