Abstract

The effectiveness of a novel 7-month psychosocial treatment designed to prevent the second episode of psychosis was evaluated in a randomized controlled trial at 2 specialist first-episode psychosis (FEP) programs. An individual and family cognitive behavior therapy for relapse prevention was compared with specialist FEP care. Forty-one FEP patients were randomized to the relapse prevention therapy (RPT) and 40 to specialist FEP care. Participants were assessed on an array of measures at baseline, 7- (end of therapy), 12-, 18-, 24-, and 30-month follow-up. At 12-month follow-up, the relapse rate was significantly lower in the therapy condition compared with specialized treatment alone (P = .039), and time to relapse was significantly delayed for those in the relapse therapy condition (P = .038); however, such differences were not maintained. Unexpectedly, psychosocial functioning deteriorated over time in the experimental but not in the control group; these differences were no longer statistically significant when between-group differences in medication adherence were included in the model. Further research is required to ascertain if the initial treatment effect of the RPT can be sustained. Further research is needed to investigate if medication adherence contributes to negative outcomes in functioning in FEP patients who have reached remission, or, alternatively, if a component of RPT is detrimental.

Keywords: first-episode psychosis, early psychosis, relapse prevention, randomized controlled trials

Introduction

The aims of specialized first-episode psychosis (FEP) treatment programs have included early recognition of psychosis and timely engagement of patients in treatments tailored to specific stages of the disorder, with the ultimate goal of recovery.1 FEP programs reduce hospital readmissions and the need for supported accommodation compared with standard community care.2

However, some important gaps remain between the stated aims of FEP programs and the clinical and psychosocial outcomes that patients achieve—especially over the longer term.2 This includes the common problem of psychotic relapse.

Approximately 35%–70% of FEP patients will be adversely affected by relapse.3 The clinical imperative to reduce relapse rates in FEP stems from the patients’ distress, carers’ burden, the potential for relapse to derail hard-won progress in psychosocial recovery, the risk of persistent psychosis after each new episode, and the added economic burden of treating relapse.4

There is a paucity of rigorously designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for the prevention of relapse following FEP. Our recent meta-analysis showed that there was a total of only 9 published pharmacological and nonpharmacological RCTs of an appropriate standard.5The interpretation and comparison of these findings are somewhat compromised by lack of consensus regarding the definition and measurement of relapse.6 Despite this, it does appear that specialist FEP programs have led to improved relapse rates compared with standard treatments. The reported relapse rate in specialist FEP care of approximately 35% over 2-year follow-up is favorable when compared with previously published relapse rates of 55%–70%.3 Furthermore, first-generation antipsychotic medications have produced improvements in relapse rates compared with placebo and second-generation antipsychotics may reduce relapse rates compared with first-generation antipsychotic medications. Obviously, the potential direct preventive benefits of medication are unrealized among the estimated 20%–56% of young FEP patients who do not adhere with medication.7 Side effects, such as the risks of weight gain and metabolic syndrome in FEP, are also significant issues for clinicians when considering maintenance antipsychotic treatment.8

The limitations of pharmacological treatments highlight the importance of evaluating novel psychosocial interventions in order to achieve incremental improvement in relapse rates in FEP. In evaluating such treatments, it is important that comparison control treatments should be based upon treatment guidelines for FEP. Recently, an advantage of FEP programs in the prevention of relapse compared with standard psychiatric care has been noted.

We have conducted an RCT of a 7-month multimodal relapse prevention therapy (RPT) designed for young FEP patients who had reached remission on positive psychotic symptoms. We compared our manualized and combined individual and family cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)-based RPT intervention, plus specialist treatment within an FEP program, with specialist treatment alone. Participants were assessed over 30 months on an array of clinical, functioning, and quality of life (QoL) measures. At the end of treatment (7 months), the RPT group had a significantly reduced relapse rate and longer time to relapse than the treatment as usual (TAU) group.9 We subsequently reported that at 30 months after baseline, carers who received RPT reported a significantly improved experience of caregiving compared with carers randomized to specialist FEP care alone.10

Preventative interventions need to be evaluated at appropriate intervals extending beyond the treatment phase. Hence, we report on the final follow-up outcomes for patient participants in our trial, including results at 30 months after baseline.

Our primary hypothesis was that the rate of, and time to, relapse would be significantly lower for FEP participants randomized to RPT compared with TAU within a specialized FEP service as assessed at 6 intervals over a 30-month follow-up period. Secondary hypotheses were that awareness of illness, secondary morbidity, QoL, medication adherence, and substance abuse would be significantly improved in the RPT compared with TAU as assessed at 6-monthly intervals over a 30-month follow-up period.

Methods

Our method was previously reported,9 and we describe only the major features here.

Design

The Episode II RCT compared a combined family and individual RPT plus TAU within 2 specialist FEP services. There were 6 assessment time points: baseline, 7, 12, 18, 24, and 30 months.

Participants

Patients from the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (EPPIC) in Melbourne and from JIGSAW, Barwon Health in Geelong, Victoria, Australia, were recruited between November 2003 and May 2005. The study inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of a first episode of a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)11 psychotic disorder, less than 6 months of prior treatment with antipsychotic medications, age 15–25 years inclusive, and remission on positive symptoms of psychosis. Remission was defined as 4 weeks or more of scores of 3 (mild) or below on the subscale items hallucinations, unusual thought disorder, conceptual disorganization, and suspiciousness on the expanded version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).12 Exclusion criteria were ongoing active positive psychotic symptoms, severe intellectual disability, inability to converse in or read English, and participation in previous CBT trials. All patient participants provided written informed consent to participate and provided additional consent for their family to be approached to be involved. Family members also provided informed consent.

Treatments

Relapse Prevention Therapy.

The RPT individual research therapist also adopted the role of outpatient case manager for the duration of their treatment and remained involved, at the EPPIC site as the case manager after the period of treatment had concluded. Research therapists functioned as members of the treatment team allowing the effectiveness of RPT to be evaluated within existing “real-world” clinical roles. Patients had continued routine treatment with their outpatient psychiatrist and had access to home-based treatment and group interventions.

The individual therapy intervention comprised 5 phases of therapy underpinned by a CBT framework. The aims of the first phase included engagement and assessment of recovery and risk for relapse. In the second phase, the formulation and therapy agenda were agreed upon with the patient, with a focus upon risk factors for relapse. The third phase focused upon reducing the risks for setbacks, and in the fourth, the potential early warning signs of relapse were identified and a relapse plan formulated. The fifth phase included optional modules addressing client-specific relapse factors. The final phase included a review and termination session. In addition to psychoeducation specific to each module, the therapists utilized supportive interventions and CBT techniques including motivational interviewing, behavioral experimentation, and socratic questioning.13 Modules were provided within a 7-month therapy window, approximately fortnightly matching the recommended frequency of TAU sessions.14

The family intervention was provided by a trained family therapist. It was informed by cognitive behavioural family therapy for schizophrenia15 and family interventions for FEP.16 The phases of family therapy were (1) assessment and engagement, (2) assessment of family communication, (3) burden and coping, (4) psychoeducation regarding relapse risk, and (5) a review of early warning signs and documentation of a relapse prevention plan. Treatment manuals are available by request.

Treatment fidelity was ensured via the following procedures: (1) the manualization of the intervention techniques, (2) clinical supervisors (J.F.M.G. and D.W.) provided feedback to research therapists in weekly clinical supervision sessions, and (3) the review of audiotapes of individual therapy sessions. A representative sample of sessions (n = 46) stratified by therapy phase was rated on a specifically designed fidelity measure (Relapse Prevention Therapy-Fidelity Scale [RPT-FS]) designed to assess both treatment adherence and therapist competence as defined in the intervention manual.13 The scale included 45 items arranged into 7 subscales, which corresponded to 6 of the therapy modules and a general therapeutic factors scale. Items on each subscale corresponded to therapist’s behavior and raters identified whether the behavior was present or absent.13 Fidelity to the adherence modules was determined in 43 of the 46 sessions rated.13

Treatment as Usual.

Patients randomized to TAU continued with their routine treatment, which was coordinated via an outpatient case manager and outpatient consultant psychiatrist.17 All case managers were orientated to early psychosis treatment guidelines.18 Fidelity was managed via approximately fortnightly one-to-one supervision for all case managers with a senior clinician and via weekly compulsory multidisciplinary case review. TAU case managers were expected to provide family work including psychoeducation and support where indicated. Separate family therapy was available for more complex family cases.

Key differences between TAU and RPT included: (1) the shared written individualized formulation regarding relapse risk, (2) the systematic approach to relapse prevention via a range of cognitive behavioral interventions, (3) the parallel individual and family sessions focused upon relapse prevention, and (4) supervision specifically focused upon relapse prevention.

Assessment Procedures

Research assistants (B.N. and D.S.) who were blind to treatment allocation administered all assessment measures. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, including the modules for psychoses, mood disorders and substance use disorders,19 and personality disorders,20 was completed at baseline. All diagnostic interviews and available clinical material were reviewed in regular diagnosis consensus meetings attended by 3 of the researchers (J.F.M.G., D.W., and B.N.). Symptom measures included the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale,21 BPRS, Schedule for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS),22 and the Scale for the Unawareness of Mental Disorder.23 Medication was not controlled for but was treated as a background factor. Medication adherence was measured via the Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS),24 which is a self-report questionnaire including items regarding adherence behavior and attitudes to medication. Medication side effects were measured using the Liverpool University Neuroleptic Side-effects Rating Scale (LUNSERS).25 Pre-morbid intelligence quotient was estimated via the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading.26 A range of psychosocial functioning measures included the Premorbid Adjustment Scale,27 the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS),28 and the Australian version of the WHO Quality of Life instrument.29 Measures of substance abuse included the WHO Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test30 and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Severity of substance dependence was assessed using the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS).31 Face-to-face interviews were completed at 6 time points, including baseline, 7-, 12-, 18-, 24-, and 30-month follow-up. At the follow-up time points, all efforts were made to recontact study participants by the study research assistants (RAs); however, because of the well-known clinical challenges in following up this complex population, there was an allowance made for a maximum of a 3-month window in which assessments were undertaken. Additional interim telephone calls were also undertaken at 6-weekly intervals in order to complete ratings on the psychotic items of the BPRS to enable prospective assessment of psychotic relapses and psychotic exacerbations.

Relapse definitions were based upon criteria utilized in a series of studies at University of California, Los Angeles.32 Criteria for relapse include increases from 3 (mild) or below to ratings of 6 or 7 (severe and very severe) on any one of the following 3 BPRS items: (1) unusual thought content, (2) hallucinations, and (3) conceptual disorganization, with a duration criterion of 1 week. Significant psychotic exacerbations following remission were defined by an increase from 3 or below (for at least 1 month) on all the 3 scales followed by a score of 5 (moderate) on any of the 3 items plus a 2-point increase on one of the other scales (again with the addition of a duration criterion of 1 week) or a rating of 5 on any one of the 3 scales for at least 1 month. Significant psychotic exacerbation following persisting psychotic symptoms (or following a partial remission) was defined as either an increase in 1 scale of at least 2 points to a rating of 6 or 7 or a 1-point rise to a rating of 6 or 7 with an accompanying 2-point rise on one of the other 2 relapse scales, for a period of at least 1 week. Consistent with previous studies of relapse, exacerbations were combined with relapses in the final categorization of patient outcome.32

Twenty cases were selected at baseline for the purpose of checking inter-rater reliability on the total score of the BPRS, with an independent RA making simultaneous ratings. Intra-class correlation coefficient for the BPRS total score was 0.93, indicating good inter-rater reliability. In addition to inter-rater checks, reliability was managed by ongoing weekly supervision of the study RA by senior members of the research team, which included direct observation of ratings at approximately 2-monthly intervals.

Data Analyses

Data were screened for outliers, nonnormality, heterogeneity of variance, and heteroscedasticity. In the instance of deviation from the normal Gaussian curve, logarithmic (plus a constant where 0 was a valid data value) transformations were used. Descriptive statistics are reported for untransformed data.

Differences between consenter/nonconsenters and study completers/noncompleters on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were examined using independent sample t tests and chi-squared analyses (χ2).

All primary and secondary analyses were based on the intent-to-treat paradigm. The primary outcome measures were the number of relapses and time to relapse (based on the time to first relapse). Group differences in the proportion of relapses at 30 months were examined using the χ2. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate survival (ie, no relapse) in the RPT and TAU groups. The Cox-Mantel log-rank test was employed to test for differences in the survival curves of these 2 groups.

To determine group differences on the secondary outcome measures, a series of mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) analyses were employed. The within-groups factor was time (baseline, 7, 12, 18, 24, 30 months) and group served as the between-subjects factor. From the model, the main effects for group (ie, overall are the RPT and TAU groups different?) and time (ie, how do ratings change over time?) can be examined along with the interaction between these variables. A Toeplitz covariance structure was used to model the relationship between observations. Significant interactions were followed by simple main effects analyses (ie, time within group and group within time). With the MMRM, a series of planned comparisons (endpoint analyses) were conducted to determine whether there were any between group differences in the overall rate of change from baseline to 30 months. MMRM is the preferred method of examining the outcomes of clinical trials.33

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of 399 patients assessed for eligibility, 213 were initially deemed eligible and 86 of these patients consented to participate in the study. Four of these patients did not meet entry criteria as determined by presence of positive psychotic symptoms at the baseline assessments. The refusal rate in relation to the number of eligible participants was 59.6% (n = 127) (refer to figure 1). The main reasons recorded for their refusal included: not interested in the study (n = 80), did not want to change case manager (n = 41), already a participant in another research project (n = 3), and other (n = 3). Data were not available for 9 families in the RPT group due to patients refusing to consent to their family being involved (n = 6) or families not consenting (n = 3). Similarly, data were not available for 9 families from the TAU group (patients refused family involvement, n = 5; families refused involvement, n = 4).

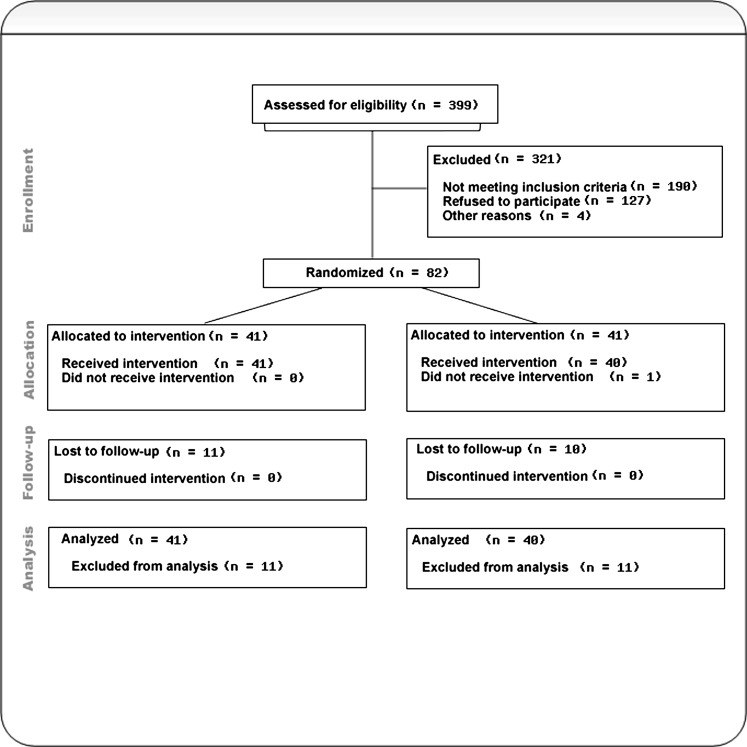

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flowchart depicting participation through various stages of the study. This applies to the primary outcome measure of relapse within the 30-month period.

Randomization and Attrition

At baseline, 1 participant dropped out after randomization to the TAU group, and no data were available for this patient (thus, n = 41 in RPT and n = 40 in TAU). Of the 81 patients for whom baseline data were available, 77 were recruited from EPPIC and 4 were recruited from Barwon Health. At 30 months, 74.1% (n = 60) of patients were assessed and 25.9% (n = 21) cases lost to follow-up (16 cases dropped out and 5 missed assessment). There are no significant differences between the 2 groups with respect to percentages of cases that were lost to follow-up (RPT, n = 11; TAU, n = 10; χ2 (1) = 0.035, P = .851).

Baseline Characteristics

Patients had been in the service on average 29.96 weeks (SD = 13.32 weeks) prior to being recruited into the study. There were no between-group differences on demographic, diagnostic, baseline symptom measures, rates of medication use, or days of hospitalization prior to entering the study (see tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Premorbid and Baseline Demographic and Diagnostic Characteristics of the Relapse Prevention Therapy (RPT) and Treatment as Usual (TAU) Groups

| Variables | Descriptive Statistic | Total Cohort (n = 81) | RPT (n = 41) | TAUl (n = 40) | Test Statistic | P-Value |

| Demographic | ||||||

| Age | M (SD) | 20.1 (3.1) | 20.1 (2.9) | 20.1 (3.2) | t test | .968 |

| Gender, % male | % (n) | 63.0 (51) | 65.9 (27) | 60.0 (24) | χ2 | .585 |

| Marital status, % never married | % (n) | 95.1 (77) | 92.7 (38) | 97.5 (39) | χ2 | .317 |

| Still attending school?, % yes | % (n) | 29.6 (24) | 26.8 (11) | 32.5 (13) | χ2 | .576 |

| Total number of years of education completed | ||||||

| Still at school | M (SD) | 12.0 (2.0) | 11.8 (1.6) | 12.2 (2.3) | t test | .413 |

| Not at school | M (SD) | 12.0 (1.7) | 12.0 (1.7) | 12.2 (1.7) | t test | .746 |

| Employmenta | ||||||

| Unemployed | % (n) | 43.2 (35) | 51.2 (21) | 35.0 (14) | χ2 | .141 |

| Full-time paid work | % (n) | 12.3 (10) | 12.2 (5) | 12.5 (5) | χ2 | .967 |

| Part-time paid work | % (n) | 4.9 (4) | 2.4 (1) | 7.5 (3) | χ2 | .293 |

| Casual paid work | % (n) | 14.8 (12) | 12.2 (5) | 17.5 (7) | χ2 | .502 |

| Lives with family, % yes | % (n) | 76.5 (62) | 73.2 (30) | 80.0 (32) | χ2 | .468 |

| Premorbid | ||||||

| DUPb | M (SD) | 384.8 (567.9) | 401.1 (529.1) | 368.6 (611.9) | t testc | .904 |

| FSIQd | M (SD) | 91.3 (27.8) | 90.8 (24.6) | 91.8 (30.9) | t test | .875 |

| Premorbid Adjustment Scalee | ||||||

| Childhood | M (SD) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.2) | t test | .299 |

| Early adolescence | M (SD) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.2) | t test | .594 |

| Late adolescence | M (SD) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | t test | .527 |

| General | M (SD) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1) | t test | .785 |

| Average | M (SD) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.2) | t test | .658 |

| Psychotic diagnoses | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | % (n) | 33.3 (27) | 34.1 (14) | 32.5 (13) | χ2 | .875 |

| Schizophreniform | % (n) | 11.1 (9) | 7.3 (3) | 15.0 (6) | χ2 | .271 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | % (n) | 4.9 (4) | 7.3 (3) | 2.5 (1) | χ2 | .317 |

| MDE with psychotic features | % (n) | 6.2 (5) | 2.4 (1) | 10.0 (4) | χ2 | .157 |

| Bipolar disorder | % (n) | 4.9 (4) | 7.3 (3) | 2.5 (1) | χ2 | .317 |

| Delusional disorder | % (n) | 1.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 2.4 (1) | χ2 | .308 |

| Substance-induced psychotic disorder | % (n) | 3.7 (3) | 4.9 (2) | 2.5 (1) | χ2 | .571 |

| Psychotic disorder NOS | % (n) | 29.6 (24) | 34.1 (14) | 25.0 (10) | χ2 | .367 |

| Other diagnoses | ||||||

| MDE without psychotic features | % (n) | 23.5 (19) | 17.1 (7) | 30.0 (12) | χ2 | .170 |

| Dysthymic disorder | % (n) | 8.6 (7) | 9.8 (4) | 7.5 (3) | χ2 | .718 |

| Past history of MDE | % (n) | 22.2 (18) | 26.8 (11) | 17.5 (7) | χ2 | .313 |

| Borderline personality disorderf | % (n) | 7.6 (6) | 10.0 (4) | 5.1 (2) | χ2 | .414 |

| Antisocial personality disorderg | % (n) | 10.4 (8) | 10.5 (4) | 10.3 (4) | χ2 | .969 |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | % (n) | 24.7 (20) | 24.4 (10) | 25.0 (10) | χ2 | .590 |

| Cannabis abuse/dependence | % (n) | 51.9 (42) | 61.0 (25) | 42.5 (17) | χ2 | .096 |

| Opioid abuse/dependence | % (n) | 7.4 (6) | 9.8 (4) | 5.0 (2) | χ2 | .414 |

| Cocaine abuse/dependence | % (n) | 3.7 (3) | 2.4 (1) | 5.0 (2) | χ2 | .542 |

| Hallucinogen abuse/dependence | % (n) | 14.8 (12) | 12.2 (5) | 17.5 (7) | χ2 | .502 |

| Amphetamine abuse/dependence | % (n) | 18.5 (15) | 17.1 (7) | 20.0 (8) | χ2 | .735 |

Note: DUP, Duration of Untreated Psychosis; FSIQ, Full Scale IQ; MDE, Major Depressive Episode.

Not mutually exclusive categories.

Estimated on the basis of time between onset of symptoms and entry into the service.

Test statistic based on logarithmic-transformed data due to the extreme skewness of duration of untreated psychosis.

Estimated based on performance on the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading.

Scores range from 0.0 to 1.0 with higher scores indicative of “healthier” levels of adjustment.

For borderline personality disorder, TAU denominator was 39 and for RPT group denominator was 40.

For antisocial personality disorder, TAU denominator was 39 and for RPT group denominator was 38.

Table 2.

Cumulative Proportion Surviving (and SE)a at Each of the Main Study Time Points

| Relapse Prevention Therapy (RPT) | Treatment as Usual (TAU) | |

| 7 months | 0.976 (0.024) | 0.795 (0.065) |

| 12 months | 0.897 (0.049) | 0.713 (0.073) |

| 18 months | 0.832 (0.063) | 0.713 (0.073) |

| 24 months | 0.798 (0.069) | 0.713 (0.073) |

| 30 months | 0.728 (0.079) | 0.631 (0.085) |

Estimated using the Kaplan-Meier statistic.

Completers at 30-month follow-up were contrasted with participants who had dropped out (n = 16) or who had missed their assessment (n = 5) on a range of demographic and baseline clinical variables. The case in the TAU group that did not have a baseline assessment was excluded from these analyses. Noncompleters had significantly higher premorbid functioning during childhood (completers, M = 0.3, SD = 0.2 and noncompleters, M = 0.2, SD = 0.1; t(73) = 2.09, P = .040) and early adolescence (completers, M = 0.3, SD = 0.2 and noncompleters, M = 0.2, SD = 0.1; t(50.7) = 3.18, P = .003). No other differences between these 2 groups were found for demographic, diagnostic (Axis I including substance use disorder and Axis II disorders), and baseline clinical characteristics. Importantly, functioning at entry to the study was comparable between completers and noncompleters.

Treatment Received

Patients who were assigned to RPT completed an average of 8.51 (SD = 4.87) therapy sessions, and 25 (61%) completed a full course of individual RPT, which was defined as the completion of all relevant phases of therapy including the termination phase. Completers of therapy received a mean of 11.84 sessions (SD = 1.55).

Treatment Outcomes

Data on relapses were available for 30 patients in the RPT group and 30 patients in the TAU group. Within the 30-month follow-up period, there were no significant differences between the relapse/exacerbation rates for the 2 groups (RPT, 30.0%, n = 9 and TAU, 43.3%, n = 13, χ2(1) = 1.15, P = .284). Five cases in each group met the relapse criteria. In the RPT, 4 cases had an exacerbation compared with 8 cases in the TAU group. There were 3 cases in the RPT group and 1 in the TAU group who had 2 events. The 3 cases in the RPT group each had an exacerbation followed by a period of recovery and then another exacerbation. The 1 case in the TAU group with multiple events had a relapse followed by a period of recovery and then an exacerbation.

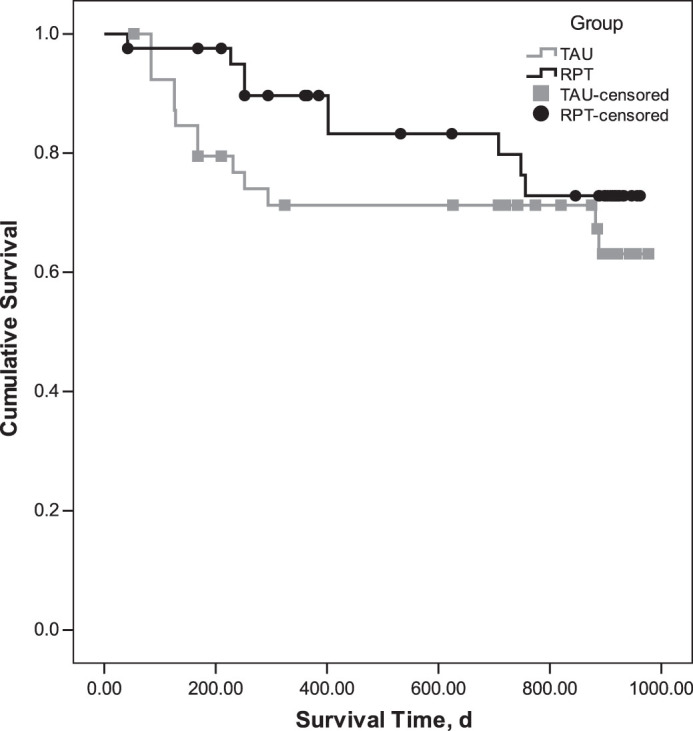

The cumulative proportion surviving at each of the main study time points is detailed in table 2. The mean survival time for the RPT group (M = 823.50, SE = 43.45) was greater than for the TAU group (M = 734.87, SE = 59.47); however, the difference in survival curves was not significant at the 30-month time point, Log rank χ2 (1) = 1.330, P = .246; (see figure 2). On examination of figure 2, it appeared that there may be differences in cumulative survival at earlier assessment time points in the study. Indeed, in our earlier article,9 a difference in survival curves between the 2 groups was noted at 7 months at the end of therapy. To determine the sustainability of treatment effects, a series of secondary survival analyses for each assessment time point were performed. The difference between groups was sustained at the 12-month time point (see figure 3), Log rank χ2(1) = 4.28, P = .038 (see figure 2). The percentage of relapses at 12 months also differed between the 2 groups; the relapse rate in the TAU (28.2%, n = 11) group was nearly 3 times greater than for the RPT group (10.0%, n = 4, χ2(1) = 4.26, P = .039).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the cumulative survival from psychotic relapse of the relapse prevention therapy (RPT) and treatment as usual (TAU) groups over 30 months.

Fig. 3.

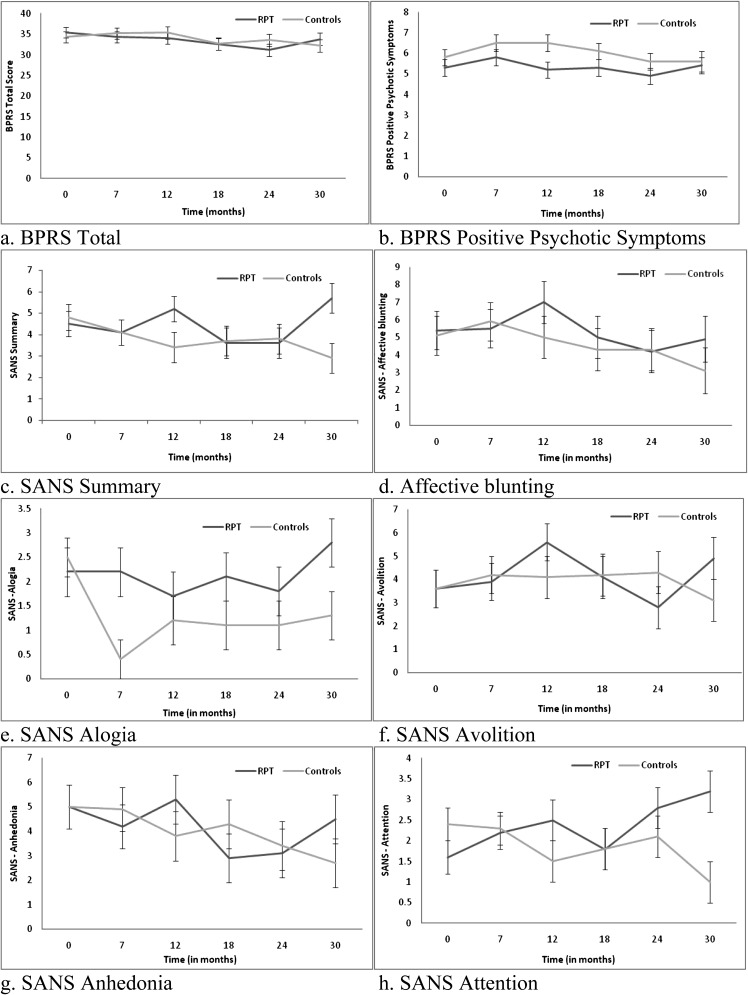

Means (±SE) derived from mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) for symptoms, functioning, and medication adherence.

The results for the MMRMs for the other clinical and functional measures are depicted in tables 3 and 4; figure 3. Over the 30 months, there were no significant between group differences with respect to overall psychopathology, severity of positive psychotic symptoms, insight depressive symptoms, and substance use measures. There were significant interactions between group and time for SANS summary scores, F 5,185.5 = 2.28, P = .049; SANS alogia, F 5,214.1 = 4.15, P = .001; and SANS attention F 5,154.2 = 2.71, P = .023 (see table 4). For the SANS summary score, the RPT group had a significantly higher mean score at 30 months compared with the TAU group (P = .013). Endpoint analyses indicated that the TAU group had significantly greater improvement in the SANS summary score from baseline to 30 months than the RPT group (P = .018) (see Table 4, figure 3c). For SANS alogia (see figure 3e), the RPT group had significantly higher scores than the TAU group at 7 months (P = .002), 18 months (P = .031), and 30 months (P = .041). Endpoint analyses indicated that the TAU demonstrated significantly greater improvement in alogia from baseline to 30 months compared with the RPT group (P = .006). For SANS attention (see figure 3h), the RPT group had a significantly higher mean score than TAU group at 30 months (P = .001). The rate of improvement on SANS Attention from baseline to 30 months was significantly greater in the TAU group (P = .001).

Table 3.

Tests of Fixed Effects in Mixed-Effects Model Repeated Measures ANOVA for Measures of Psychopathology, Substance Use, Functioning, Quality of Life, and Medication Adherence

| Effect | F test | df | P | Effect | F test | df | P |

| Symptoms | Substance use | ||||||

| BPRS total scorea | AUDITa | ||||||

| Group | 0.07 | 174.6 | .786 | Group | 0.01 | 183.2 | .918 |

| Time | 2.23 | 5122.6 | .055 | Time | 1.30 | 5130.1 | .272 |

| Group × time | 1.13 | 5122.6 | .347 | Group × time | 0.73 | 5130.1 | .603 |

| BPRS positive symptomsa | SDSa | ||||||

| Group | 2.41 | 180.4 | .124 | Group | 0.42 | 176.6 | .517 |

| Time | 1.55 | 5148.5 | .178 | Time | 1.75 | 5118.3 | .128 |

| Group × time | 0.41 | 5148.5 | .844 | Group × time | 0.60 | 5118.3 | .703 |

| SANSa | ASSIST alcohol | ||||||

| Affect | Group | 0.44 | 180.72 | .509 | |||

| Group | 0.30 | 177.8 | .589 | Time | 0.56 | 5154.1 | .729 |

| Time | 1.45 | 5130.9 | .209 | Group × time | 1.47 | 5154.1 | .204 |

| Group × time | 1.14 | 5130.9 | .342 | ASSIST Cannabis | |||

| Alogia | Group | 0.35 | 179.8 | .558 | |||

| Group | 3.00 | 176.5 | .089 | Time | 0.75 | 5140.9 | .588 |

| Time | 4.06 | 5214.1 | .002 | Group × time | 0.33 | 5140.9 | .896 |

| Group × time | 4.15 | 5214.1 | .001 | Functioning | |||

| Avolition | SOFAS | ||||||

| Group | 0.52 | 180.0 | .475 | Group | 0.80 | 179.1 | .374 |

| Time | 1.59 | 5148.1 | .168 | Time | 2.52 | 5128.4 | .033 |

| Group × time | 1.70 | 5148.1 | .137 | Group × time | 2.30 | 5128.4 | .049 |

| Anhedonia | Quality of life | ||||||

| Group | 0.02 | 178.9 | .879 | Physical | |||

| Time | 2.62 | 5144.8 | .027 | Group | 1.00 | 176.4 | .320 |

| Group × time | 1.50 | 5144.8 | .191 | Time | 0.79 | 5135.9 | .556 |

| Attention | Group × time | 0.63 | 5135.9 | .676 | |||

| Group | 2.20 | 178.1 | .142 | Psychological | |||

| Time | 0.40 | 5154.2 | .849 | Group | 1.41 | 175.9 | .239 |

| Group × time | 2.71 | 5154.2 | .023 | Time | 1.90 | 5124.5 | .100 |

| Summaryb | Group × time | 0.81 | 5124.5 | .545 | |||

| Group | 1.38 | 180.6 | .243 | Social relationships | |||

| Time | 2.11 | 5185.5 | .066 | Group | 0.58 | 176,1 | .450 |

| Group × time | 2.28 | 5185.5 | .049 | Time | 1.05 | 5142.4 | .392 |

| MADRSa | Group × time | 1.16 | 5142.4 | .331 | |||

| Group | 1.02 | 172.5 | .316 | Environment | |||

| Time | 16.63 | 5165.9 | <.001 | Group | 1.21 | 176.1 | .275 |

| Group × time | 1.02 | 5165.9 | .406 | Time | 0.75 | 5138.1 | .591 |

| SUMD | Group × time | 0.56 | 5138.1 | .732 | |||

| Awareness of disorder (past and current) | Medication adherencea | ||||||

| Group | 0.04 | 170.4 | .840 | Group | 0.03 | 165.2 | .866 |

| Time | 1.75 | 5154.9 | .127 | Time | 2.59 | 5109.8 | .030 |

| Group × time | 0.76 | 5154.9 | .583 | Group × time | 2.35 | 5109.8 | .045 |

| Awareness of medication (past and current) | |||||||

| Group | 0.48 | 1, 71.0 | .492 | ||||

| Time | 1.15 | 5, 145.3 | .336 | ||||

| Group × time | 1.29 | 5, 145.3 | .273 | ||||

Note: BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SANS, Schedule for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SUMD, Scale for Unawareness of Mental Disorders; MADRS, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; SDS, Severity of Dependence Scale; ASSIST, Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test; SOFAS, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale. Bold values indicate significant effects ( P < .05).

Analyses based on logarithmic (plus constant)-transformed data due to extreme positive skewness.

Summary score was computed by summing the 5 global items of the SANS.

Table 4.

Secondary Efficacy Endpoints Over 30 Months

| Characteristics | Baseline | 30 Months | t b | df | P | ||

| RPT, M (SE)a | TAU, M (SE) | RPT, M (SE)a | TAU, M (SE) | ||||

| Symptoms | |||||||

| BPRS totalc | 35.4 (1.3) | 34.3 (1.3) | 33.8 (1.5) | 32.2 (1.5) | 0.30 | 46.7 | .767 |

| BPRS positive symptomsc | 5.3 (0.4) | 5.8 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.5) | 5.6 (0.4) | 0.40 | 48.0 | .691 |

| SANSc | |||||||

| Affective | 5.4 (1.1) | 5.1 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.3) | 0.33 | 74.4 | .741 |

| Alogia | 2.2 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.4) | 2.8 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) | 2.80 | 111.2 | .006 |

| Avolition | 3.6 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.8) | 4.9 (0.9) | 3.1 (0.9) | 1.49 | 80.8 | .140 |

| Anhedonia | 5.0 (0.9) | 5.0 (0.9) | 4.5 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.0) | 1.80 | 98.4 | .075 |

| Attention | 1.6 (0.4) | 2.4 (0.4) | 3.2 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.5) | 3.60 | 89.0 | .001 |

| Summary | 4.4 (0.6) | 4.8 (0.6) | 5.6 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.40 | 96.9 | .018 |

| SUMD | |||||||

| Awareness of mental disorder | 2.0 (0.2) | 2.0 (02) | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | −0.97 | 117.3 | .337 |

| Awareness of response to medication | 1.6 (1.7) | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | −1.92 | 102.8 | .057 |

| MADRSc | 9.8 (1.4) | 11.1 (1.5) | 7.6 (1.7) | 7.4 (1.7) | 0.03 | 44.7 | .977 |

| Substance use | |||||||

| AUDITc | 7.8 (1.0) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.2 (1.2) | 7.3 (1.1) | −1.41 | 87.1 | .161 |

| SDSc | 3.3 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.8 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) | 0.18 | 104.3 | .854 |

| ASSIST alcohol | 3.7 (0.5) | 2.7 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.6) | 3.3 (0.6) | −1.32 | 57.6 | .192 |

| ASSIST Cannabis | 3.8 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.8) | −0.98 | 127.3 | .337 |

| Functioning | |||||||

| SOFAS | 61.2 (2.6) | 65.2 (2.7) | 63.2 (3.1) | 72.1 (3.1) | −1.05 | 84.5 | .297 |

| Quality of life | |||||||

| Physical | 69.3 (2.7) | 65.7 (2.7) | 71.0 (3.1) | 70.6 (3.1) | −0.74 | 72.9 | .464 |

| Psychological | 56.4 (3.3) | 54.3 (3.3) | 61.8 (3.8) | 57.1 (3.7) | 0.53 | 82.9 | .598 |

| Social relationships | 63.2 (3.7) | 58.5 (3.8) | 66.0 (4.4) | 57.5 (4.3) | 0.58 | 94.3 | .566 |

| Environment | 63.5 (2.6) | 62.0 (2.7) | 66.2 (3.1) | 61.6 (3.0) | 0.74 | 102.3 | .460 |

| Medication adherence | |||||||

| MARSc | 6.7 (0.4) | 7.0 (0.3) | 8.3 (0.6) | 7.1 (0.45) | 1.95 | 77.6 | .055 |

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the first footnote to table 3. BPRS total score (range 18–126), BPRS positive symptoms (4–28), SANS affective (0–40), SANS alogia (0–25), SANS avolition (0–20), SANS anhedonia (0–25), SANS attention (0–15), SANS summary (0–25), SUMD (1–5), MADRS (0–60), AUDIT (0–40), SDS (0–15), ASSIST (0–20), SOFAS (0–100), WHOQoL-Bref (1–100), MARS (0–100). Bold values indicate significant effects ( P < .05).

Mean (M) and standard error (SE) estimates derived from the mixed model repeated measures (MMRM).

Endpoint analyses are based on planned comparison t tests derived from mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) model. The focus was on comparing between groups differences in the change from baseline to the 30-month follow-up time point.

Analyses based on logarithmic (plus constant)-transformed data due to extreme positive skewness. Descriptive statistics are based on untransformed data.

There was a significant group by time interaction for SOFAS scores, F 5,128.4 = 2.30, P = .049 (see figure 3l). The RPT group had significantly lower functioning at 30 months compared with the TAU group (P = .043) (see figure 3l). For the TAU group, functioning was significantly higher at 30 months compared with the baseline (P = .039). For the RPT group, the SOFAS was significantly higher at both 18 months (P = .002) and 24 months (P = .003) compared with baseline; however, functioning at 30 months was not significantly different from baseline (P = .547).

There was a significant group by time interaction for the MARS, F 5, 109.8 = 2.35, P = .045 (see figure 3m). Further analysis indicated that the RPT (P = .002) and not the TAU (P = .994) group had significant change over time. For the RPT group, there was significant improvement from baseline to 24 months (P = .004) and baseline to 30 months (P = .015) in terms of medication adherence. Endpoint analysis was not significant (P = .055).

Other Analyses

In order to attempt to explain differences with the SANS, SOFAS, and MARS, further analyses were conducted to determine whether the 2 treatment groups differed with respect to number of case management sessions, number of contacts with group program activities, number of hospitalizations, medication dose (chlorpromazine [CPZ] equivalent units), and medication side-effects (LUNSERS) over the 30 months. The 2 groups had a similar amount of case management sessions (RPT, M = 29.2, SD = 17.4 and TAU, M = 28.8, SD = 18.3; P = .916), contacts with group program activities (RPT, M = 6.5, SD = 11.1 and TAU, M = 8.5, SD = 17.1; P = .536), days of hospitalization (RPT, M = 10.5, SD = 16.3 and TAU, M = 8.4, SD = 13.0; P = .518), and total CPZ equivalents over the 30 months (RPT, M = 952.1, SD = 853.9 and TAU, M = 1111.3, SD = 1175.9; P = .494). There were no significant interactions between group and time for LUNSERS total (males F 5, 70.64 = 1.52, P = .195 and females, F 5,51.24 = 0.72, P = .614) and Red Herring (males F 5, 78.86 = 1.49, P = .204 and females, F 5,46.67 = 0.42, P = .832) scores. We also conducted a series of MMRM analyses to determine whether the unexpected findings on the SANS and SOFAS could be explained by increased medication adherence in the RPT group. A change score was computed (baseline to 30 months) for medication adherence, and this score was added as a covariate in the MMRM. For SANS attention and SOFAS, the interaction between group and time became not significant when change in medication adherence was controlled for (SANS attention, F 5, 56.7 = 0.75, P = .588 and SOFAS F 5, 34.91 = 1.89, P = .120). For SANS alogia and SANS summary, the interactions between group and time remained significant even after medication adherence was controlled for (SANS alogia, F 5, 50.94 = 2.57, P = .038 and SANS summary, F 5, 39.12 = 3.14, P = .018).

Discussion

The overall relapse rates observed in the current study were similar to previously published relapse rates from FEP programs.3 However, relapse rates were lower and the timing of relapses was delayed in the RPT group compared with the TAU group at the end of therapy (7 months) and at 12 months. However, these differences were not sustained at 18, 24, and 30 months.

Thus, RPT in the short-term appears to provide benefit to patients but may not have a sustained effect, perhaps due to the limited duration of the treatment. By way of comparison trials of effective family-based interventions for the prevention of relapse in schizophrenia have entailed 9 months of therapy and longer in some studies.34 A previously published individual CBT therapy for the prevention of relapse in schizophrenia included ongoing monitoring of early warnings signs and opportunistic intervention at the detection of elevated early warning signs35—an approach which may prolong the initial treatment effect of RPT.

We found partial support for our secondary hypotheses—improvements were observed over 30 months in medication adherence in the RPT group. To our knowledge, this is the first outcome study that has shown a sustained treatment effect for improving medication adherence in FEP compared with specialized treatment, and this is a rare outcome even in the broader schizophrenia research literature.

Conversely, there was no significant additional benefit of RPT in relation to awareness of illness, secondary morbidity, or quality of life, consistent with the findings of a previous study comparing CBT with specialist FEP treatment.36 This may indicate a difficulty with achieving significant and sustained improvements in outcome in comparison with specialized FEP care.

There were 2 unexpected findings: group by time interactions with regards to psychosocial functioning, which showed deterioration only in the RPT group over time, and a group by time interaction for negative symptoms with the TAU group improving but not the RPT group. This could not be explained by differences in the amounts of other psychosocial treatment received. Both groups had equal access to psychosocial treatments including vocational and educational activities. Nor were there any significant differences in antipsychotic medication doses prescribed or number of hospitalizations, which may have interrupted recovery in functioning.

It is possible that an unidentified component of our intervention may have a detrimental effects upon functioning and negative symptoms.37 For example, perhaps the intervention increased anxiety, or rational concern, regarding relapse, which mediated increased avoidance of goal attainment, consistent with cognitive models of relapse.38 We would concur with Lilienfeld that replication is required to definitively draw this conclusion.37 Against this interpretation, is that the reduction in functioning in the RPT group was only apparent at the 30-month time point, and there is no previously published evidence to support this conclusion, so we believe this is unlikely.

When differences in medication adherence were controlled for, the group by time interaction was no longer significant. This finding raised the possibility that for FEP patients who reach remission on positive symptoms, adherence to antipsychotic medication may have had an indirect effect (via side-effects), upon psychosocial functioning over time. This interpretation was not consistent with the lack of significant effects on the LUNSERS. However, it is notable that the relative timing of changes in medication adherence and psychosocial functioning in the RPT group as depicted in figure 3 show that increases in adherence (18–24 months) preceded decreases in psychosocial functioning and increases in negative symptoms (24–30 months) in the RPT group. This is consistent with previous research showing an association between better vocational functioning at 2-year follow-up and placebo treatment compared with antipsychotic medication in a first-episode schizophrenia sample.39 Therefore, it remains possible that antipsychotic medication may be impacting functioning in the absence of measureable subjective side effects. Other possible explanations for this finding are that medication adherence scores may reflect other indirect impacts upon functioning, including attitudes to treatment or other clinical factors, such as personality traits. Finally, it is possible that this was a spurious finding.

Limitations and Strengths

Our study was the first to test a novel psychosocial intervention for relapse prevention for FEP. The strengths of our study included the randomization of patients, the blinding of research assistants, the manualized treatments, the careful management of fidelity, and the duration of follow-up assessments. Further improvements could have included the audio taping of case management sessions to test the fidelity of specialist FEP treatment and increased sample size to improve the statistical power. In addition, although quantity of specific treatments was measured across all phases of the study, quality of treatment was not measured beyond the period of RPT, which would have enabled us to examine its effects upon outcomes at follow-up. While we believe we took all possible steps to ensure that the sample was representative, it is possible that the severity of cooccurring symptoms varied from the population of remitted FEP patients. In terms of measurement, it is also possible that the MARS confounded the measurement of attitudes toward medication with actual doses consumed. A recent validation study with a relatively large sample of patients with psychosis highlighted concerns regarding the concurrent validity of the MARS.40 In hindsight, a multimethods approach, rather than a single self-report measure, would have been the optimal approach to the measurement of adherence. In relation to the intervention, we also note that the change in case manager may have introduced an uncontrolled element to the experimental condition, which may have reduced the magnitude of treatment effects. Finally, the combination of individual and family CBT does not enable the analysis of the specific contribution of these 2 components to treatment outcomes.

Further Research

Our findings with regards to the primary hypothesis highlight the need to trial extensions of our intervention. We also argue for novel approaches to sustain the relapse prevention components. We believe that this could be achieved via information communication technology, which has been relatively underutilized in this patient group. We also contend that problems of secondary morbidity and psychosocial functioning require longer term interventions. Finally, the impact of antipsychotic medication upon functioning in the subgroup of patients, who maintain remission on positive symptoms should be evaluated in an RCT of intensive psychosocial interventions with and without maintenance medication.

Funding

This Study was funded by an unrestricted grant from Eli Lilly via the Lilly Melbourne Academic Psychiatry Consortium. In addition, the study was supported by the Colonial Foundation and a Program grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (350241). No funding body had any involvement in any aspect of the study or manuscript. A/Prof. S.M.C. is supported by the Ronald Phillip Griffith Fellowship, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry, and Health Science, the University of Melbourne.

Acknowledgments

P.D.M. has received honoraria and research grant support from Janssen Cilag, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Novartis and Astra Zeneca. The other authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study. Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (http://www.anzctr.org.au/) Number: 12605000514606.

References

- 1.McGorry PD, Killackey E, Yung A. Early intervention in psychosis: concepts, evidence and future directions. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:148–156. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, et al. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness: the OPUS trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:762–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Addington D, Addington MDJ, Patten S. Relapse rates in an early psychosis treatment service. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115:126–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu BJ, Faries DE, et al. The cost of relapse and the predictors of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, McGorry PD, Gleeson JF. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:619–630. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gleeson JF, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Cotton SM, Parker AG, Hetrick S. A systematic review of relapse measurement in randomized controlled trials of relapse prevention in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2010;119:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassidy CM, Rabinovitch M, Schmitz N, Joober R, Malla A. A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to antipsychotic medication in first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:64–67. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181ca03df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel J, Buckley P, Woolson S, et al. Metabolic profiles of second-generation antipsychotics in early psychosis: findings from the CAFE study. Schizophr Res. 2009;111:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gleeson JF, Cotton SM, Alvarez-Jimenez M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of relapse prevention therapy for first-episode psychosis patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:477–486. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gleeson JF, Cotton SM, Alvarez-Jimenez M, et al. Family outcomes from a randomized control trial of relapse prevention therapy in first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:475–483. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04672yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lukoff D, Liberman RP, Nuechterlein KH. Symptom monitoring in the rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1986;12:578–593. doi: 10.1093/schbul/12.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Wade D, Cotton S, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in psychotherapy research: novel approach to measure the components of cognitive behavioural therapy for relapse prevention in first-episode psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:1013–1020. doi: 10.1080/00048670802512057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre. Case Management in Early Psychosis: A Handbook. Parkville, Victoria, Australia: EPPIC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falloon I. Handbook of Behavioral Family Therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linszen D, Dingemans P, Van der Does JW, et al. Treatment, expressed emotion and relapse in recent onset schizophrenic disorders. Psychol Med. 1996;26:333–342. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Early Psychosis Guidelines Writing Group. Australian Clinical Guidelines for Early Psychosis. 2 ed. Melbourne, Australia: Orygen Youth Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGorry P, Killackey E, Lambert T, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:1–30. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ventura J, Liberman RP, Green MF, Shaner A, Mintz J. Training and quality assurance with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P) Psychiatry Res. 1998;79:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) User's guide and Interview. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montgomery SM. Depressive symptoms in acute schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. 1979;3:429–433. doi: 10.1016/0364-7722(79)90058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andreasen NC. Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Flaum MM, Endicott J, Gorman JM. Assessment of insight in psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:873–879. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew A. Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2000;42:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambert TJR, Cock N, Alcock SJ, Kelly DL, Conley RR. Measurement of antipsychotic-induced side effects: support for the validity of a self-report (LUNSERS) versus structured interview (UKU) approach to measurement. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:405–411. doi: 10.1002/hup.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginsberg JP. Wechsler test of adult reading. Appl Neuropsychol. 2003;10:182–184. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1982;8:470–484. doi: 10.1093/schbul/8.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising Axis-V for DSM-IV—a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1148–1156. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali R, Awwad E, Babor T, et al. The Alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97:1183–1194. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gossop M, Darke S, Griffiths P, et al. The severity of dependence Scale (SDS): Psychometric properties of the SDS in English and Australian samples of heroin, cocaine and amphetamine users. Addiction. 1995;90:607–614. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9056072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH, Hardesty JP, Gitlin M. Life events and schizophrenic relapse after withdrawal of medication. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:615–620. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gueorguieva R, Krystal J. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:310–331. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol Med. 2002;32:763–782. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gumley A, O'Grady M, McNay L, Reilly J, Power K, Norrie J. Early intervention for relapse in schizophrenia: results of a 12-month randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy. Psychol Med. 2003;33:419–431. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson H, McGorry P, Edwards J, et al. A controlled trial of cognitively oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis (COPE) with four-year follow-up readmission data. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1295–1306. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705004927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lilienfeld S. Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:53–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gumley A, White C, Power K. An interacting cognitive subsystems model of relapse and the course of psychosis. Clin Psychol Psychother. 1999;6:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnstone EC, Macmillan JF, Frith CD, Benn DK, Crow TJ. Further investigation of the predictors of outcome following first schizophrenic episodes. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:182–189. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fialko L, Garety PA, Kuipers E, et al. A large-scale validation study of the medication adherence rating scale (MARS) Schizophr Res. 2008;100:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]