Abstract

Cisplatin is commonly used against several solid tumors, and oxaliplatin is an effective cytotoxic drug used in colorectal cancer. A major clinical issue affecting 10–40 % of patients treated with cisplatin or oxaliplatin is severe peripheral neuropathy causing sensory, motor, and autonomic dysfunction, with symptoms including cold sensitivity and neuropathic pain. The biochemical basis of the neurotoxicity is uncertain, but is associated with oxidative stress. Curcumin (a natural phenolic yellow pigment) has strong antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory actions. Here we report the possible protective effect of curcumin on some cisplatin- and oxaliplatin-induced behavioral, biochemical, and histopathological alterations in rats. Twenty-four hours after the end of treatments some motor and behavioral tests (motor activity, thermal and mechanical nociception, and neuromuscular coordination) were conducted, followed by measuring plasma neurotensin platinum concentration in the sciatic nerve, and studying the histopathology of the sciatic nerve. Oxaliplatin (4 mg/kg) and cisplatin (2 mg/kg) [each given twice weekly, in a total of nine intraperitoneal injections over 4.5 weeks] significantly increased plasma neurotensin concentration, caused specific damage in the histology of the sciatic nerve and produced variable effects in the motor and behavioral tests. Oral curcumin (10 mg/kg, 4 days before the platinum drug, and thereafter, concomitantly with it for 4.5 weeks) reversed the alterations in the plasma neurotensin and sciatic nerve platinum concentrations, and markedly improved sciatic nerve histology in the platinum-treated rats. Larger experiments using a wider dose range of oxaliplatin, cisplatin, and curcumin are required to fully elucidate the possible protective role of curcumin in platinum-induced neurotoxicity.

Keywords: Cisplatin, Oxaliplatin, Curcumin, Rats, Neurotoxicity

Introduction

Cisplatin is a platinum-based chemotherapeutic agent that is commonly used against various solid tumors in the ovary, testis, and colon. Oxaliplatin is a diaminocyclohexane carrier-ligand platinum compound introduced during the 1990s. It is a third-generation organoplatinum compound with significant activity against solid tumors, and especially metastatic colorectal cancer (the second in cancer-related deaths in the USA) [1, 2]. Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy protocols, particularly oxaliplatin in combination with infusional 5 fluorouracil/leucovorin (FOLFOX or FUFOX), have emerged as the standard of care in first- and second-line therapy of advanced-stage colorectal cancer [3].

Although oxaliplatin has a better safety profile than cisplatin, the use of both drugs is associated with neurotoxicity, targeting dorsal root ganglia (DRG) [4–7]. In a recent review and meta-analysis, it has been confirmed that oxaliplatin has a small but significant survival benefit over cisplatin in patients with gastric cancer, and causes lesser toxicity [8]. Thirty percent of patients treated with cisplatin develop a peripheral neuropathy, and 20 % of them are forced to stop treatment [9]. The profile of oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity differs from those of other platinum compounds in having an acute peripheral sensory and motor toxicity with initial symptoms of either paraesthesia or cold-related dysesthesia. Oxaliplatin is the major active platinum complex detected in plasma ultrafiltrate of treated patients, and the plasma biotransformation products of oxaliplatin are unlikely to contribute to its efficacy or toxicity [10]. The mechanism(s) of platinum compounds neurotoxicity is not fully understood [5]. Among the several hypothesis proposed to explain the neurotoxicity, DRG oxidative stress can be an important mechanism and, possibly, a therapeutic target to limit the severity of platinum-induced peripheral neurotoxicity but preserving the anticancer effectiveness [11, 12].

Several agents have been used in an attempt to either ameliorate or prevent oxaliplatin neurotoxicity [13–15]. The polyphenolic non-flavon compound curcumin (diferuloylmethane, isolated from the turmeric plant, Curcuma longa) is a well-known and commonly used oriental spice utilized for food color and flavor; it is also used in Asian and African traditional medicine to treat several mild or moderate human diseases such as affections of the skin, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal systems; aches; wounds; sprains; and liver disorders [16, 17]. In recent years, a growing body of evidence has unraveled the strong antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and other activities of curcumin based on the ability of this compound to regulate a number of cellular signal transduction pathways [18–20].

As far as we are aware, the effect of curcumin against the neurotoxicity of the anticancer platinum compounds has not been reported, although the neuroprotective action of curcumin has been shown in other conditions, such as stroke [21] and homocysteine-induced cognitive impairment [22]. In the present work, we have looked at the possible neuroprotective action of curcumin against oxaliplatin and cisplatin neurotoxicity in rats using some behavioral, biochemical, and histopathological methods. In this work, we measured neurotensin in plasma, although it has not been specifically shown before as a direct consequence of platinum toxicity, although it is known to be elevated in other neuropathic conditions [23].

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing initially about 175 g were housed (three rats per cage and six rats per treatment) in standard laboratory conditions (20–23°C, relative humidity of about 60 %, and with a light–dark cycle of 12:12 h; lights on at 0600 hours) with ad libitum access to food (Oman Flour Mills, Muscat, Oman) and tap water for at least 1 week before the experiments. The behavioral and histopathological studies were conducted in a blind fashion with respect to the treatment given.

This project was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Committee of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences (SQU), and experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by our Institutional Animal Research Ethics Committee, and the international laws and policies (EEC Council directives 86/609, OJL 358, 12 December, 1987; and NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, NIH Publications No. 85-23, 1985).

Treatments

Rats were randomly divided into five groups (six rats in each group) and treated as follows:

Injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with glucose solution (5 %, w/v) at a dose of 1 ml/kg twice weekly (a total of nine injections in 4.5 weeks), together with distilled water, given by gavage (inserting a small-diameter tube into the esophagus, and delivering the solution directly into the stomach by means of a syringe), at a daily dose of 1 ml/kg, given 4 days prior to the glucose, and thereafter, concomitantly with the drug for 4.5 weeks.

Injected i.p. with oxaliplatin (4 mg/kg) twice weekly (a total of nine injections in 4.5 weeks), together with orally administered distilled water, as in group 1.

Injected with oxaliplatin as in group 2, but replacing water with curcumin, suspended in distilled water, given orally (as in group 1) at a dose of 10 mg/kg, 4 days prior to the platinum drug, and, thereafter, concomitantly with the drug for 4.5 weeks.

Injected i.p. with cisplatin (2 mg/kg) twice weekly (a total of nine injections in 4.5 weeks), together with orally administered distilled water, as in group 1.

Injected with cisplatin as in group 4, but replacing water with curcumin (10 mg/kg), as in group 3.

Injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with glucose solution (5 %, w/v) at a dose of 1 ml/kg twice weekly (a total of nine injections in 4.5 weeks) with curcumin, as in group 3.

The cumulative dose of oxaliplatin was 36 mg/kg in groups 2 and 3, while that of cisplatin it was 48 mg/kg in groups 4 and 5. The choice of doses was based on previously published works [24, 6].

Immediately after the end of the last behavioral test, rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (75 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg), and blood (3 mL) collected from the anterior vena cava was placed into heparinized tubes. The blood was centrifuged at 900×g at 4°C for 15 min. The plasma obtained was stored frozen at −80°C pending analysis. The rats were then euthanized with an overdose of ketamine.

Motor and Behavioral Methods

The motor and behavioral experiments used were carried out by the same worker (A.A.) to minimize variation, and the methods used included the following:

Motor activity: Locomotor (ambulatory) and behavioral (total) activity was measured using a computerized animal activity meter (Ugo Basil, Milan, Italy), as described recently [25].

Locomotor coordination: Impairment of neuromuscular coordination was measured in control and treated rats as the time that they stayed on a rotarod treadmill (Ugo Basil, Milan, Italy), as described before [25]. The interval between the animal mounting the rod and falling off was recorded by means of a built-in timer; this was considered as the performance time.

Cold water tail flick test: The latency to flick the tail in cold water was used as an antinociceptive index, according to a standard procedure described by Pizziketti et al [26].

Paw pressure test: Mechanical (static) nociceptive threshold as an index of mechano-hyperalgesia was assessed by a pressure stimulation method using an analgesy-meter (Ugo Basil, Milan, Italy). Mechanical pressure was applied to the rat's paw, which was placed on a small plinth under a cone-shaped pusher with a rounded tip, and when the rat struggled, the operator released the pedal and read from the scale the force at which the animal felt pain.

Tail flick: Thermal nociceptive threshold was measured in rats using the tail flick test and equipment from Ugo Basil (Milan, Italy). The tail flick test measures automatically the nociceptive threshold to infrared heat stimulus on the rat tail. The operator starts the stimulus and when the animal feels pain and flicks its tail, a sensor detects it, stops the timer and switches off the bulb.

Biochemical Measurements

The concentration of neurotensin in the plasma was measured (by a biomedical scientist unaware of the treatments) by an ELISA kit (Phoenix Pharmaceutical, Inc, Burlingame, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The left sciatic nerve was dissected out from each rat sacrificed, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C pending analysis. The platinum concentration was measured in the sciatic nerve by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, as previously described for the kidneys of rats treated with cisplatin [27].

Histological Methods

As described before by Cavaletti et al, [28], the right sciatic nerve was excised, washed with ice-cold saline, blotted with filter paper, and weighed. Each nerve was then casseted and fixed directly in 10 % neutral formalin for 24 h. This was followed by dehydration in increasing concentrations of ethanol, clearing with xylene, and embedding into paraffin. Four-micrometer sections were prepared from paraffin blocks and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Sections were incubated at 60°C overnight with a 0.1 % solution of luxol fast blue (LFB) dissolved in 95 % ethanol. Sections were differentiated by 0.05 % lithium carbonate solution. The sections were counter stained with 0.1 % cresyl violet solution for 30 s before they were finally dehydrated and mounted. The stained sections were evaluated in a blinded fashion by a histopathologist (S.S.), using light microscopy.

Evaluation of Demyelination Areas

The lesion areas (demyelination area) were calculated by dividing the mean surface area of demyelination areas, defined by absence of luxol fast blue staining of myelin, to the mean total surface area of the nerve fibers, expressed as a percentage. Surface areas were measured using ImageJ software (INH, USA).

Drugs and Chemicals

Oxaliplatin was gifted by Sanofi-Aventis (France). Cisplatin was bought from Ebewe (Pharma, Unterach, Austria). All other chemicals used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Values reported are expressed as mean + SEM and were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests (Graphpad Prism version 4.03, San Diego, CA, USA). A probability level of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

General Toxicity

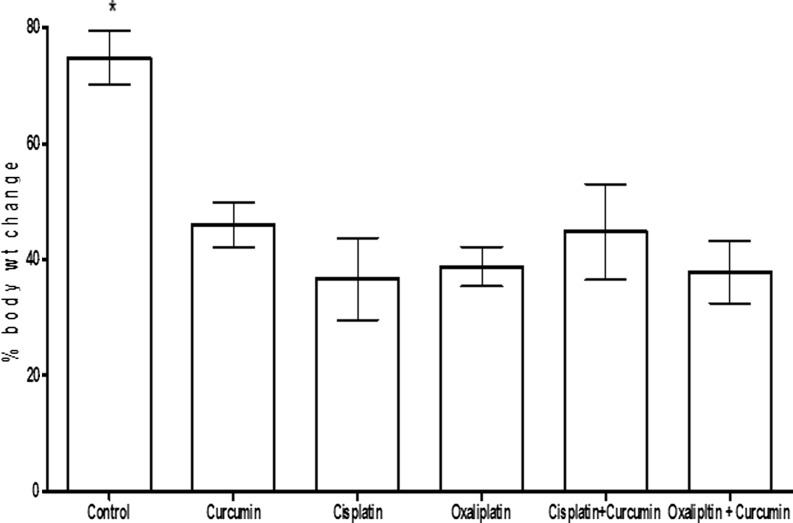

General toxicity of all rats was monitored (by the same worker to avoid possible variation) by daily observation, and body weight changes were measured once weekly. The treatment-induced changes in body weight are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The percentage body increase over the period of study (4.5 weeks) in rats treated with glucose (1 ml/kg, twice weekly; a total of nine injections in 4.5 weeks), curcumin (10 mg/kg, given orally 4 days prior to the platinum drug, and thereafter, concomitantly with the drug for 4.5 weeks), cisplatin (2 mg/kg, twice weekly; a total of nine injections in 4.5 weeks), oxaliplatin (4 mg/kg, twice weekly; a total of nine injections in 4.5 weeks), and cisplatin + curcumin and oxaliplatin + curcumin, at the above doses. Each column and vertical bar depict mean ± SEM (n = 6 rats). Growth in the control group was significantly higher than in the rest of the groups (among which there was no significant difference in body weight increase)

Effect of Platinum Compounds (With or Without Curcumin) on Some Motor and Behavioral Tests

The motor and behavioral tests conducted revealed that the treatments administered resulted in variable effects that were not statistically significant (results not shown). Although cisplatin- or oxaplatin-treated animals appeared weaker and less active than control animals, there was no measurable effect on mortality or behavioral outcomes.

Effect of Platinum Compounds (With or Without Curcumin) on Neurotensin

Both cisplatin and oxaliplatin treatments significantly increased the plasma concentration of neurotensin by about 59–64 %, compared with the glucose-treated controls. Curcumin alone did not significantly change the neurotensin concentration. Coadministration of curcumin with either of the two platinum drugs significantly blunted the rise in the neurotensin concentration (Table 1).

Table 1.

Neurotensin concentration in the plasma of rats treated with glucose, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin, with or without curcumin

| Treatments | Neurotensin (ng/ml) |

|---|---|

| Glucose (control) | 1.04 ± 0.09 |

| Oxaliplatin | 1.65 ± 0.17* |

| Oxaliplatin + curcumin | 1.25 ± 0.18** |

| Cisplatin | 1.71 ± 0.19* |

| Cisplatin + curcumin | 1.21 ± 0.16** |

| Curcumin | 1.17 ± 0.11 |

Data in the table are means ± SEM (n = 6)

*P < 0.05 (when comparing oxaliplatin or cisplatin groups to control group)

**P < 0.05 (when comparing oxaliplatin or cisplatin groups to curcumin group) are statistically different from each other)

Effect of Oxaliplatin and Cisplatin (With or Without Curcumin) on Platinum Concentration in Sciatic Nerve

Platinum was not detectable in specimens from the control and curcumin-treated rats (Table 2). Treatment with oxaliplatin and cisplatin together with curcumin insignificantly decreased the platinum concentration by about 9 % (oxaliplatin) and 8 % (cisplatin).

Table 2.

Platinum concentration in the sciatic nerve of rats treated with glucose, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin, with or without curcumin

| Treatments | Platinum μg/g of tissue |

|---|---|

| Glucose (control) | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Oxaliplatin | 1.32 ± 0.11* |

| Oxaliplatin + curcumin | 1.20 ± 0.18** |

| Cisplatin | 1.44 ± 0.14* |

| Cisplatin + curcumin | 1.21 ± 0.16** |

| Curcumin | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

Data in the table are means ± SEM (n = 6)

*P < 0.05 (when comparing oxaliplatin or cisplatin groups to control group)

**P < 0.05 (when comparing oxaliplatin or cisplatin groups to curcumin group) are statistically different from each other)

Effect of Platinum Compounds (With or Without Curcumin) on Sciatic Nerve Histology

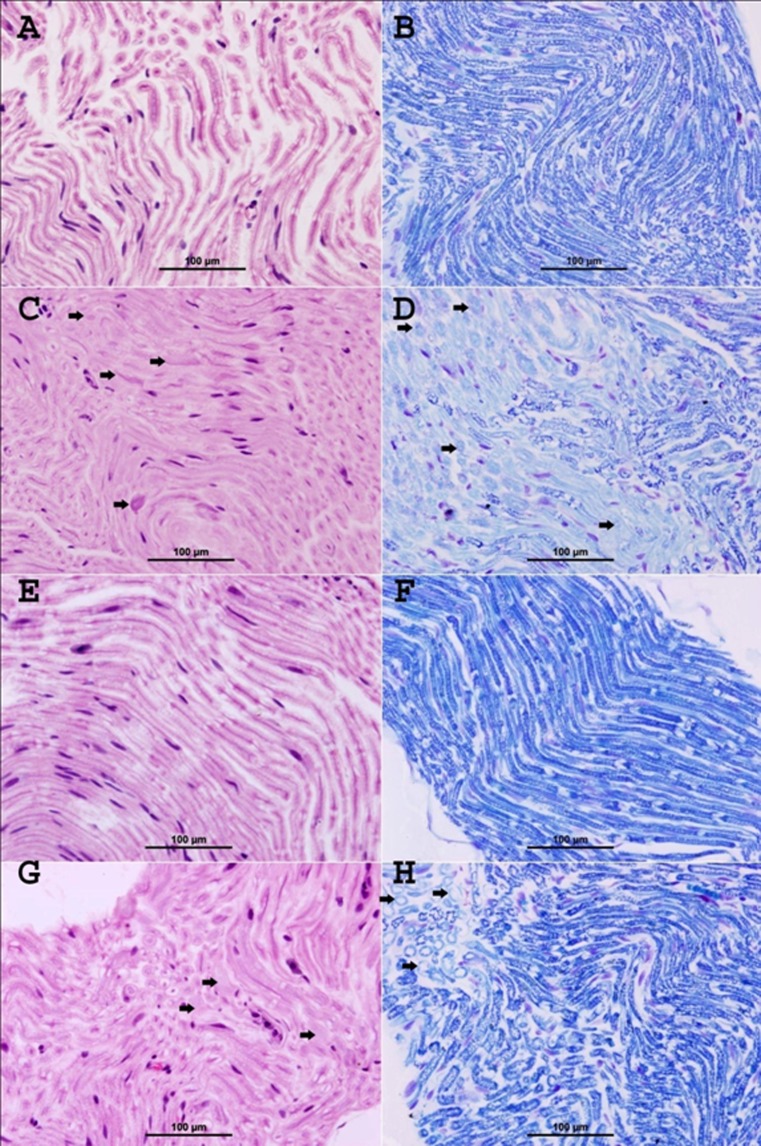

Cisplatin experiment

The control glucose-treated group showed normal myelinated fibers and no evidence of demyelination (Fig. 2A, Table 3). LFB stain showed normal deep blue staining of the myelin sheath with normal round contours of the myelinated fibers and no evidence of demyelination (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Representative photographs of sections of the sciatic nerve of rats treated with glucose (A and B), cisplatin (C and D), curcumin (E and F), and cisplatin + curcumin (G and H), as follows: A control glucose-treated group shows normal myelinated nerve fibers,(H&E stain). B Control glucose-treated group shows deep blue staining of normal myelin sheath (LFB stain). C Cisplatin-treated group shows focal areas of demyelination and degeneration of the nerve fibers (thick arrows). Areas of infiltration with mononuclear inflammatory cells were also noticed (thin arrows) (H&E stain). D Cisplatin-treated group demonstrates areas of demyelination (thick arrows), which have light blue staining compared with the normal deep blue staining in normal fibers, and decrease in the caliber of nerve fibers. Foci of axonal degeneration were also seen (thin arrows) (LFB stain). E Curcumin-treated group shows normal appearance of myelinated nerve fibers (H&E stain). F Curcumin-treated group shows normal deep blue staining of the myelin sheath (LFB stain). G Cisplatin + curcumin-treated group shows marked decrease in the demyelination (arrows) (H&E stain). H Cisplatin + curcumin-treated group demonstrates a marked decrease of demyelination (arrows), which have light blue staining compared with the normal deep blue staining in normal fibers (LFB stain)

Table 3.

Semiquantitative analysis of histology of sciatic nerve in rats treated with saline, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin, with or without curcumin

| Treatments | Demyelination (%, mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|

| Glucose (control) | 0 ± 0 |

| Oxaliplatin | 33.2 ± 3.4* |

| Oxaliplatin + curcumin | 4.8 ± 0.3** |

| Cisplatin | 29.4 ± 2.1* |

| Cisplatin + curcumin | 5.5 ± 0.6** |

| Curcumin | 0 ± 0.0 |

Data in the table are means ± SEM (n = 6)

*P < 0.05 (when comparing oxaliplatin or cisplatin groups to control group)

**P < 0.05 (when comparing oxaliplatin or cisplatin groups to curcumin group) are statistically different from each other)

The cisplatin-treated group showed focal areas of demyelination and degeneration of the nerve fibers (arrows) (Fig. 2C). LFB stain clearly demonstrated areas of demyelination (arrows) having light blue staining and reduction in the nerve fiber caliber compared with the normal deep blue staining in normal fibers (Fig. 2D). In addition, LFB demonstrated degenerated nerve fibers (Fig. 2D).

The curcumin-treated group showed normal appearance of myelinated nerve fibers (Fig. 2E) and no evidence of demyelination (Table 3). LFB stain showed deep blue staining of the myelin sheath (Fig. 1f) and no evidence of demyelination.

The cisplatin + curcumin-treated group showed a marked decrease in demyelination (arrows, Fig. 2G, Table 1). LFB stain clearly demonstrated a marked decrease of demyelination (arrows) having light blue staining compared with the normal deep blue staining in normal fibers (Fig. 2H).

-

2.

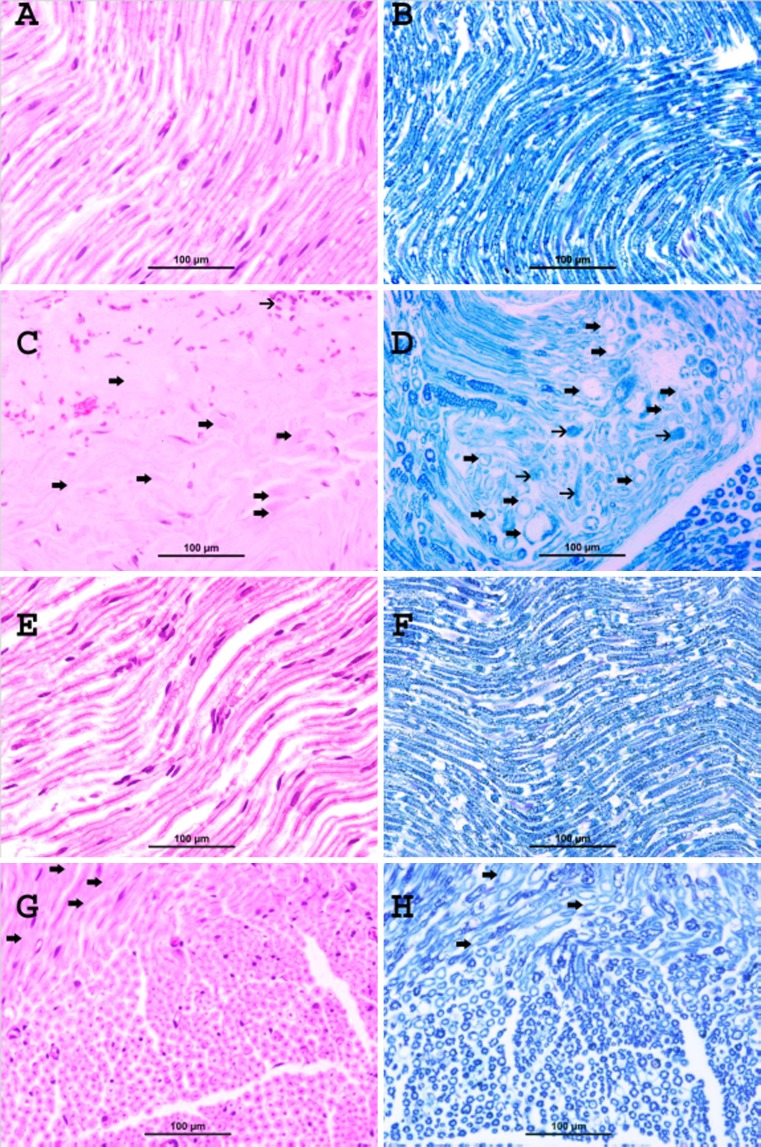

Oxaliplatin experiment

The control glucose-treated group showed normal myelinated fibers and no evidence of demyelination (Fig. 3A, Table 1). LFB stain showed normal deep blue staining of the myelin sheath with normal round contours of the myelinated fibers and no evidence of demyelination (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Representative photographs of sections of the sciatic nerve of rats treated with glucose (A and B), oxaliplatin (C and D), curcumin (E and F), and oxaliplatin + curcumin (G and H) as follows: A control glucose-treated group shows normal myelinated nerve fibers (H&E stain). B Control glucose-treated group shows deep blue staining of normal myelin sheath (LFB stain). C Oxaliplatin-treated group shows focal areas of demyelination and degeneration of the nerve fibers (thick arrows). Areas of infiltration with mononuclear inflammatory cells were also noticed (thin arrows) (H&E stain). D Oxaliplatin-treated group demonstrates areas of demyelination (thick arrows), which have light blue staining compared with the normal deep blue staining in normal fibers, and decrease in the caliber of nerve fibers. Foci of axonal degeneration were also seen (thin arrows) (LFB stain). E Curcumin-treated group shows normal appearance of myelinated nerve fibers (H&E stain). F Curcumin-treated group shows normal deep blue staining of the myelin sheath (LFB stain). G Oxaliplatin + curcumin-treated group shows marked decrease in the demyelination (arrows) (H&E stain). H Oxaliplatin + curcumin-treated group demonstrates a marked decrease of demyelination (arrows), which have light blue staining compared with the normal deep blue staining in normal fibers (LFB stain)

The oxaliplatin-treated group showed focal areas of demyelination and degeneration of the nerve fibers (thick arrows, Fig. 3C, Table 3). Areas of mononuclear inflammatory cells infiltration are noticed (thin arrow). LFB stain clearly demonstrated the areas of demyelination (thick arrows) which have light blue staining compared with the normal deep blue staining in normal fibers (Fig. 3D). In addition, LFB demonstrated degenerated nerve fibers (thin arrows; Fig. 3D).

The curcumin-treated group showed normal appearance of myelinated nerve fibers (Fig. 3E) and no evidence of demyelination (Table 3). LFB stain showed deep blue staining of the myelin sheath (Fig. 3F) and no evidence of demyelination.

The oxaliplatin + curcumin-treated group showed marked decrease in demyelination (arrows; Fig. 3G). LFB stain clearly demonstrated a marked decrease of demyelination (arrows) having light blue staining compared with the normal deep blue staining in normal fibers (Fig. 3H).

Table 3 describes a semi-quantitative analysis of sciatic nerve histology in the different groups.

Discussion

Cisplatin or oxaliplatin treatment did not result in any mortality. Others (e.g., [24]) have reported a significant drop in body weight and bloating in oxaliplatin-treated rats. Only males were used here, because of the reported sex difference in the susceptibility of rats to cisplatin-induced neurotoxicity, with male rats showing more weight loss, prolonged heat latency, and slower motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV), and females showing more sensitivity to some specific histological changes [29].

In this work, we attempted to test the possible protective effect of curcumin on some neurotoxic actions of oxaliplatin and cisplatin in rats. As far as we are aware, such an attempt has not been made before. However, it has recently been shown that curcumin can enhance oxaliplatin antiproliferative effect in models of oxaliplatin resistance in vitro, and significantly improve the drug’s in vivo efficacy, without affecting its mode of action [30]. As the mechanism of platinum analog-induced neurotoxicity involves oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction as the trigger of neuronal apoptosis [31], and curcumin has anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, and antioxidant properties in vivo and in vitro [32, 33, 17, 34], it was thought of interest to see if coadministration of curcumin with platinum compounds would either mitigate or prevent some of their neurotoxic actions. The present studies indicated that cisplatin and oxaliplatin induced a more or less similar degree of neurotoxicity in rats, and that the improvement in the histopathology of the sciatic nerve (involving staining with H&E and LFB) were the clearest evidence of an ameliorative effect of curcumin in animals treated with either platinum drug. The pathological damage induced by cisplatin and oxaliplatin were overall not very extensive, and this has been reported before [35], and concomitant treatment with curcumin reduced the severity of these changes.

It is known that the primary mechanism of neurotoxicity with cisplatin and oxaliplatin is similar [31], although cisplatin (2 mg/kg) has been shown to be more neurotoxic than oxaliplatin (4 mg/kg) due to higher retention of platinum by the DRG [6]. The results of the behavioral and biochemical parameters of the effect of curcumin on platinum compound neurotoxicities were less clear. In particular, the motor behavioral experiments conducted in this work did not reveal a clear effect for curcumin on the measured parameters. The reasons for this are not known, but may be related to the limited number of rats available in each group (n = 6), the inadequacy of the curcumin dose used (10 mg/kg, orally), or to other unknown factors. In a recent work, Ataie et al. [22] reported that curcumin (5 or 50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) did not significantly affect motor activity, but improves behavioral tests of memory in rats. On the other hand, Kumar et al. [36] reported that daily oral administration of curcumin (10, 20, and 50 mg/kg) for 8 days dose-dependently improved 3-NP-induced motor and cognitive impairment (Fig. 3).

The apparent (and statistically insignificant) decrease in the weight of rats treated with cisplatin and oxaliplatin was insignificantly antagonized by curcumin.

In this study, we measured the concentration of the 13-amino acid peptide neurotensin in the plasma, as a possible marker of peripheral neuropathy. Neurotensin is found in the gastrointestinal tract and also in different parts of the central nervous system, where blockade of some of its specific receptors has been identified as a target for possible drugs for use in the treatment of chronic pain, cancer, and other diseases, such as schizophrenia [37].

We are not aware of any other study in which neurotensin has been measured in rats with platinum drug-induced neurotoxicity. Although the specific association between neurotensin plasma and platinum neurotoxicity is not certain, neurotensin has been shown to be affected in cases of several models of neuropathy, such as in alcoholic rats [38] and several other physiological and pathological conditions [37]. The possible use of neurotensin as a possible biomarker in the neurotoxicity of platinum drugs, as has been shown in this work, should be investigated further.

The platinum concentrations in the sciatic nerve of cisplatin- and oxaliplatin-treated rats were not significantly different from each other, and were only slightly and insignificantly decreased by curcumin treatment. This may suggest that, if curcumin is to be administered as an added anticancer therapy and a neuroprotective agent, concomitant treatment of platinum compounds and curcumin may not decrease the therapeutic effectiveness of these platinum drugs.

Although this study has provided incomplete evidence for a possible neuroprotective action for curcumin in rats, the anticancer effect of the drug, in addition to its protective action against cisplatin nephrotoxicity [39], makes it an attractive agent for further study, and possibly future therapeutic applications in humans.

To obtain more conclusive conclusions on the effect of curcumin on platinum drug neurotoxicity, more extensive work is warranted with larger number of rats and a wider range of drug doses, and using more elaborate and/or non-invasive techniques, such as electron microscopy of the sciatic nerve and DRG, and tail nerve neurophysiological evaluation by measuring the MNCV. Another approach is the replacement of the “traditional” cisplatin formulation with a newer “liposomal” formulation that has been claimed to be less neurotoxic in rats [35].

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by a grant from SQU, Oman (IG/MED/MEDE/09/01). The oxaliplatin used was a kind gift from Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France. Thanks are due to the staff of the SQU Animal House for looking after the rats.

References

- 1.Saif MW, Reardon J. Management of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1:249–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah N, Dizon DS. New-generation platinum agents for solid tumors. Future Oncol. 2009;5:33–42. doi: 10.2217/14796694.5.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grothey A. Clinical management of oxaliplatin-associated neurotoxicity. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2005;5(Suppl 1):S38–46. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2005.s.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broomand A, Jerremalm E, Yachnin J, Ehrsson H, Elinder F. Oxaliplatin neurotoxicity—no general ion channel surface-charge effect. J Negat Results Biomed. 2009;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-5751-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavaletti G, Marmiroli P. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Nature Review Neurology. 2011;6:657–666. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes J, Stanko J, Varchenko M, Ding H, Madden VJ, Bagnell CR, Wyrick SD, Chaney SG. Comparative neurotoxicity of oxaliplatin, cisplatin, and ormaplatin in a Wistar rat model. Toxicol Sci. 1998;46:342–351. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster RG, Brain KL, Wilson RH, Grem JL, Vincent A. Oxaliplatin induces hyperexcitability at motor and autonomic neuromuscular junctions through effects on voltage-gated sodium channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:1027–1039. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montagnani F, Turrisi G, Marinozzi C, Aliberti C, Fiorentini G. Effectiveness and safety of oxaliplatin compared to cisplatin for advanced, unrespectable gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:50–55. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Podratz JL, Knight AM, Ta LE, Staff NP, Gass JM, Genelin K, Schlattau A, Lathroum L, Windebank AJ. Cisplatin induced mitochondrial DNA damage in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41:661–668. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shord SS, Bernard SA, Lindley C, Blodgett A, Mehta V, Churchel MA, Poole M, Pescatore SL, Luo FR, Chaney SG. Oxaliplatin biotransformation and pharmacokinetics: a pilot study to determine the possible relationship to neurotoxicity. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:2301–2309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carozzi VA, Marmiroli P, Cavaletti G. The role of oxidative stress and anti-oxidant treatment in platinum-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10:670–682. doi: 10.2174/156800910793605820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendonça LM, Dos Santos GC, Antonucci GA, Dos Santos AC, Bianchi ML, Antunes LM. Evaluation of the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of curcumin in PC12 cells. Mutat Res. 2009;675:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albers JW, Chaudhry V, Cavaletti G, Donehower RC. Interventions for preventing neuropathy caused by cisplatin and related compounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;16:2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005228.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali BH. Amelioration of oxaliplatin neurotoxicity by drugs in humans and experimental animals: a minireview of recent literature. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;106:272–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durand JP, Deplanque G, Montheil V, Gornet JM, Scotte F, Mir O, Cessot A, Coriat R, Raymond E, Mitry E, Herait P, Yataghene Y, Goldwasser F. Efficacy of venlafaxine for the prevention and relief of oxaliplatin-induced acute neurotoxicity: results of EFFOX, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2011;23:200–205. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali BH, Marrif H, Noureldyem SA, Bakhiet AO, Blunden G. Some biological properties of curcumin. A review. Natural Product Communications. 2006;1:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jurenka JS. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of Curcuma longa: a review of preclinical and clinical research. Altern Med Rev. 2009;14:141–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanmugam MK, Kannaiyan R, Sethi G. Targeting cell signaling and apoptotic pathways by dietary agents: role in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:161–173. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.523502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shehzad A, Ha T, Subhan F, Lee YS. New mechanisms and the anti-inflammatory role of curcumin in obesity and obesity-related metabolic diseases. Eur J Nutr. 2011;50:151–161. doi: 10.1007/s00394-011-0188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weissenberger J, Priester M, Bernreuther C, Rakel S, Glatzel M, Seifert V, Kögel D. Dietary curcumin attenuates glioma growth in a syngeneic mouse model by inhibition of the JAK1,2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5781–5795. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapchak PA. Neuroprotective and neurotrophic curcuminoids to treat stroke: a translational perspective. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20:13–22. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.542410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ataie A, Sabetkasaei M, Haghparast A, Moghaddam AH, Kazeminejad B. Neuroprotective effects of the polyphenolic antioxidant agent, curcumin, against homocysteine-induced cognitive impairment and oxidative stress in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;96:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillemette A, Dansereau MA, Beaudet N, Richelson E, Sarret P. Intrathecal administration of NTS1 agonists reverses nociceptive behaviors in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pain. 2012. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Cavaletti G, Tredici G, Petruccioli MG, Dondè E, Tredici P, Marmiroli P, Minoia C, Ronchi A, Bayssas M, Etienne GG. Effects of different schedules of oxaliplatin treatment on the peripheral nervous system of the rat. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2457–2463. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali BH, Ziada A, Al Husseni I, Beegam S, Nemmar A. Motor and behavioral changes in rats with adenine-induced chronic renal failure: influence of acacia gum treatment. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011;236:107–112. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pizziketti RJ, Pressman NS, Geller EB, Cowan A, Adler MW. Rat cold water tail-flick: a novel analgesic test that distinguishes opioid agonists from mixed agonist-antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985;119:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali BH, Al-Moundhri M, Tageldin M, Al Husseini IS, Mansour MA, Nemmar A, Tanira MO. Ontogenic aspects of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:3355–3359. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavaletti G, Tredici G, Marmiroli P, Petruccioli MG, Barajon I, Fabbrica D. Morphometric study of the sensory neuron and peripheral nerve changes induced by chronic cisplatin (DDP) administration in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 1992;84:364–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00227662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wongtawatchai T, Agthong S, Kaewsema A, Chentanez V. Sex-related differences in cisplatin-induced neuropathy in rats. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92:1485–1491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howells LM, Sale S, Sriramareddy SN, Irving GR, Jones DJ, Ottley CJ, Pearson DG, Mann CD, Manson MM, Berry DP, Gescher A, Steward WP, Brown K. Curcumin ameliorates oxaliplatin-induced chemoresistance in HCT116 colorectal cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:476–486. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavaletti G, Alberti P, Frigeni B, Piatti M, Susani E. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2011;13:180–190. doi: 10.1007/s11940-010-0108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aggarwal BB, Harikumar KB. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:40–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali BH, Al-Wabel N, Mahmoud OM, Mousa HM, Hashad M. Curcumin has a palliative action on gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Fundamental Clin Pharmacol. 2005;19:473–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2005.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waly M, Al-Moundhari M, Ali BH. The effect of curcumin on cisplatin and oxaliplatin-induced oxidative stress in human embryonic kidneys (HEK) 293 cells. Renal Failure. 2011;33:518–523. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.577546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canta A, Chiorazzi A, Carozzi V, Meregalli C, Oggioni N, Sala B, Crippa L, Avezza F, Forestieri D, Rotella G, Zucchetti M, Cavaletti G. In vivo comparative study of the cytotoxicity of a liposomal formulation of cisplatin (lipoplatin™) Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68:1001–1008. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar P, Padi SS, Naidu PS, Kumar A. Possible neuroprotective mechanisms of curcumin in attenuating 3-nitropropionic acid-induced neurotoxicity. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2007;29:19–25. doi: 10.1358/mf.2007.29.1.1063492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mustain WC, Rychahou PG, Evers BM. The role of neurotensin in physiologic and pathologic processes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18:75–82. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283419052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wachi M, Fujimaki M, Nakamura H, Inazuki G. Effects of ethanol administration on brain neurotensin-like immunoreactivity in rats. Acta Neurol Scand. 1996;93:211–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1996.tb00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antunes LM, Darin JD, Bianchi NL. Effects of the antioxidants curcumin or selenium on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and lipid peroxidation in rats. Pharmacol Res. 2001;43:145–150. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]