Abstract

This paper compares native residents’ opinions and perceptions regarding immigration using a representative survey from a pair of matched North Carolina counties—one that experienced recent growth of its foreign-born population and one that did not. Drawing from several theoretical perspectives, including group threat, contact theory, and symbolic politics, we formulate and empirically evaluate several hypotheses. Results provide limited evidence that competition and threat influence formation of opinions about immigration, with modest support for claims that parents with school-aged children harbor more negative views of immigration than their childless counterparts. Except for residents in precarious economic situations, these negative opinions appear unrelated to the immigrant composition of the community. Claims that the media promotes negative views of immigration receive limited support, but this relationship is unrelated to the volume of local immigration. Finally, sustained contacts with foreign-born residents outside work environments are associated with positive views of immigration, but superficial contacts appear to be conducive to anti-immigration sentiments. Political orientation, educational attainment and indicators of respondents’ tolerance for diversity explain most of the difference between the two counties in overall support for immigration.

I. The Problem

Through most of the past century, immigration was largely an abstraction for the majority of native-born Americans except residents of a few large cities in five immigrant gateway states: New York, California, Florida, Texas, and Illinois. Even after mass immigration resumed during the 1970s, most newcomers settled in one of the traditional urban destinations, such as New York City, Miami, Chicago and Los Angeles. In the 1980 Census, 64 percent of immigrants and 88 percent of Mexican immigrants who arrived between 1975 and 1980 lived in one of the “big five” traditional immigrant destination states listed above (Massey and Capoferro 2008:35). Outside of the coastal gateways and the Southwestern states, immigration existed comfortably in the past. During the 1980s, however, not only did the volume of immigration rise, particularly from Mexico, but residence patterns began to change. Lured by plentiful unskilled jobs and affordable housing, immigrant workers settled in communities where immigrants had a minimal presence. Thus, by 2005, only about half of all immigrants and half of Mexican immigrants who had arrived in the previous five years resided on one of the “big five” states (Massey and Capoferro 2008:38).

Although immigrant settlement remained concentrated, increased inflows combined with geographical dispersal of the foreign-born population transformed many places throughout the United States. For the first time in a century, immigrants began to populate small and midsize communities across the nation, most notably in the South and Midwest. In North Carolina, the site of our study, the foreign-born population surged from 115 thousand persons in 1990 to 630 thousand by 2007. In that year 115 thousand children in North Carolina resided with at least one foreign-born parent. Thus, in less than 20 years the share of North Carolina’s school-age youth living in immigrant households rose from 3.4 percent to 14.2 percent (Migration Policy Institute 2009).

For native residents, the geographic dispersal of immigrants rekindled a familiar love-hate relationship. As the widely publicized controversies in Farmingville NY, Hazelton PA, Danbury CT and elsewhere attest, employers and homemakers delight at immigrants’ willingness to work long, often irregular hours for low wages, but community residents often resent their presence in schools, neighborhoods, and public spaces. In many places where social divisions were sharply drawn in black and white, the arrival of Latin American immigrants spawned new racial tensions (Marrow 2008, 2009; Murphy, Blanchard, and Hill 2001). Viglucci’s (2000) interviews with employers, community leaders and parents in Chatham County, North Carolina, one of our study sites, give voice to these tensions:

“I hate to think what would happen if the immigrants left tomorrow. Our industry would disappear.”-Siler City Town Manager Joe Brower

“I heard from other parents, ‘My child is the only white child in the classroom.’ ” -T.C. Yarborough, President of the Siler City Elementary School Parent-Teacher Association

“We (African Americans) were already down, and now we’re even further behind. Latinos have rented and are steadily buying a lot of property. They have cash money, they have good credit, they’re a good liability. People cater to them. But it has made housing skyrocket.” -Rev. Barry Gray, pastor of the First Missionary Baptist Church of Siler City.

These anecdotes not only invite a re-consideration of the integration prospects of recent immigrants settled in nontraditional destinations, but also provide hints about how the geographic dispersal of the foreign-born population shapes attitudes toward immigration. First, geographic dispersal changes the context for interactions between natives and immigrants. In the new immigrant destinations, immigration is neither a relatively familiar process (as it is in the traditional destinations) nor a distant abstraction (as it remains in much of the country), but a dynamic and challenging part of everyday life. Second, public and private institutions in these places are now compelled to serve an ethnically distinct and rapidly growing population segment. This may also disrupt established racial and social hierarchies, particularly if established residents perceive greater competition for coveted resources (jobs, seats in local schools, housing) and a drain on public coffers. Third, the newcomers face thinner social networks and few co-ethnic organizations compared with the traditional destinations, and this has direct implications for their acceptance. Finally, the geographic dispersal is occurring in the context of vitriolic national debates about illegal immigration, which also may influence local attitudes toward immigrants and immigration.

The opinions of natives in the new settlement communities regarding immigration are of interest to social scientists in their own right and because they partly define the contexts of reception for new immigrants. Aspects of these contexts include interpersonal relationships between immigrants and natives, the capacity and willingness of local institutions to serve the needs of newcomers, the character of the local labor market, and the constellation of state and local policies that govern access to social goods—all of which are influenced by the opinions natives hold about immigrants and immigration. (Rumbaut and Portes 2000; Portes and Rumbaut 2006).

The growing residential dispersal of foreign-born populations has not gone unnoticed, but the literature about native residents’ acceptance of immigrants has yet to fully explore the implications of this geographic shift. Researchers have documented the timing, scale and residential contours of the new settlement patterns, establishing the dominance of Mexican and Central American immigrants in the dispersal (Massey and Capoferro 2008). Other studies observe the great diversity of impacted communities, which range from resurgent urban cores to booming suburbs and small towns across the country (Singer, Hardwick, and Brettell 2008). Passel, Capps and Fix (2004) estimate that the unauthorized share of the foreign-born population is substantially higher in most of the new immigrant destinations compared with the traditional hubs. Each of these factors implies that the geographic dispersal may provoke different reactions among natives in the new immigrant destinations.

This paper examines the reactions of the native population to the influx of immigrants in nontraditional destinations. Using a representative survey from a pair of matched counties in North Carolina—one that experienced rapid growth in its immigrant population and one that did not—we identify local responses to growth of the foreign-born population. Building on insights from existing case studies of immigrant-native relations in new immigrant destinations and the rich theoretical literature about immigrant integration in traditional hubs, we develop and test several hypotheses about how natives’ characteristics and experiences shape perceptions of and opinions toward immigration, depending on whether native populations are directly exposed to the foreign-born. That the two counties are located in the same metropolitan area, have overlapping media markets, and have similar industry structures provides a contrast between opinions about immigration by native residents who witnessed growth in the foreign-born population at close range and those who observed the phenomenon from a distance.

To motivate and provide context for the empirical analysis, the next section presents the available evidence on recent changes in public opinion in the new immigrant destinations and nationwide. The third section provides a framework for theorizing individual natives’ responses to immigrants and formulates several testable propositions. Following a description of the sites, the data, and statistical methods, we present empirical results—both descriptive comparisons between the two target counties and multivariate analyses designed to test specific claims. The concluding section draws both research and policy implications in light of evidence that the dispersal is unlikely to reverse, even if its pace abates in the near term.

II. Evidence on Native Reactions in the New Immigrant Destinations

Available evidence is ambiguous about whether and how the geographic dispersal of the foreign-born population is associated with variation in opinions about immigrants and immigration. Televised and printed media target high profile cases that showcase anti-immigration legal actions, protests or violence in new immigrant destinations like Hazelton, PA and Farmingville, NY (Barry 2006; Lambert 2005; Kaplan 2008). Such incidents leave the impression that immigrants foster conflict in new settlement areas. Precisely because they are extreme, however, such anecdotes about place and time-specific incidents are not helpful for gauging the prevalence, intensity, or correlates of anti-immigration sentiment.

Beyond individual incidents, nonprofit and advocacy organizations have reported a rise in anti-immigration extremist groups, discrimination, and violence have become more common since geographical dispersal of the foreign-born began. For example, the Leadership Council on Civil Rights (2009) reports a 40 percent increase in the annual number of hate crimes committed against Hispanics between 2003 and 2007. Some advocates link increases in abuse and discrimination against immigrants directly to geographic dispersal (Bauer and Reynolds 2009).

The strongest evidence about the reactions of native residents to new immigrant neighbors comes from a body of richly textured case studies that describe the complex dynamics at work in specific places, for national origin groups, or in particular industries (see studies collected in Anderson 2000; Stull, Broadway, and Griffith 1995; Massey 2008; Singer, Hardwick, and Brettell 2008; Zuniga and Hernández-León 2005; Gozdziak and Martin 2005). A few of these studies have systematically studied opinions of different groups of natives. For example, Fennelly (2008) finds that residents from lower socioeconomic classes harbor more negative opinions about immigrants than higher status groups, although respondents of all classes expressed concerns about safety and nostalgia for the days before immigration. Community leaders reported benefits to diversity and the local economy, but middle- and working-class respondents expressed concerns about impacts on jobs and schools and use of public benefits by immigrants. Based on interviews with residents in two rural North Carolina communities, Marrow (2008) finds that blacks feel economically, but not politically, threatened by new immigrants, although perceived threat is less intense in the area where blacks comprise the majority of the population.

With no counterfactual to compare findings, case studies cannot answer whether natives’ opinions depend on the level of local immigration. Additionally, qualitative descriptions of place-specific institutional and social dynamics do not permit adjudication of competing explanations about native responses to immigrants. Only a few studies use either indirect measures of opinion change, such as political actions, or survey data to systematically evaluate opinion about immigration in new destinations.

Legislative and administrative actions by municipalities and states to limit immigrants’ access to public resources are an indirect indicator of natives’ opinions about immigration, and a potentially important aspect of the local context of reception. Because regulation of immigration is legally the dominion of the federal government, immigrant-specific ordinances indicate that local communities are struggling to deal with immigration. In 2007, state legislatures considered 1,059 immigration-related bills and passed 167 of those (Migration Policy Institute 2008). From 2005 to 2007, localities proposed over 176 immigration-related ordinances, of which nearly three-fourths passed (Ramakrishnan and Tom Wong 2008). The least welcoming communities require landlords to check the legal status of tenants, allow police to assist federal officials in apprehension and deportation activities, or send powerful symbolic messages by declaring English the official language (Rodriguez, Chisti, and Nortman 2007). The most welcoming localities direct local service agencies and police to ignore legal status, issue local identification cards for all residents, and/or aggressively promote English and citizenship education.

It is not yet clear whether negative (and/or positive) legislative measures are direct responses to growth of the foreign-born population. In 2007, legislatures in the ten states with the fastest-growing immigrant populations considered over twice the number of bills regulating the employment of immigrants and also passed more bills that reduce the rights of immigrants than the six top traditional immigrant destination states (Lagalaron et al. 2008). Municipalities that considered anti-immigration ordinances were more likely to have experienced significant growth in their immigrant population than a set of matched controls that did not consider such action (Hopkins, 2007). However, Ramakrishnan and Wong (2008) find that the rate of growth of the local Hispanic population does not predict whether municipalities propose or pass an anti-immigration ordinance.

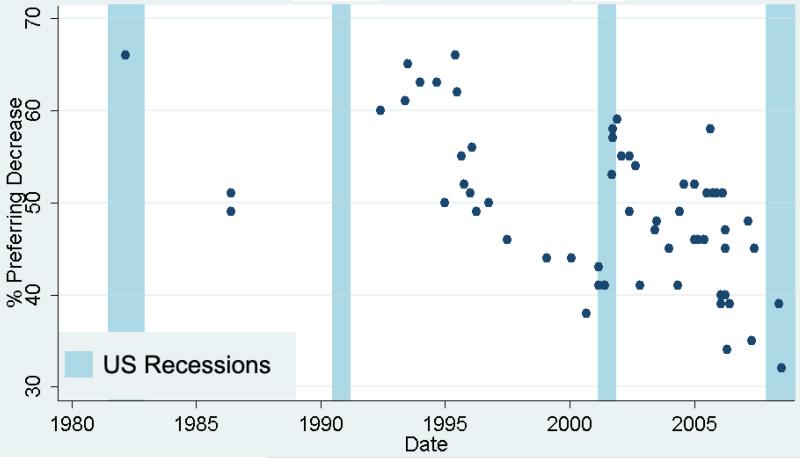

Representative telephone surveys provide another perspective on variation in opinions about immigration. If the geographic spread of the foreign-born population provoked a negative change in public opinion during the 1990s and 2000s, it was overwhelmed by other shifts in national opinion. Opinions about immigration among the general American public are conveniently measured based on responses to variants of the question, “Should (legal) immigration be kept at its present level, increased or decreased?” Using this metric, national polls indicate that restrictionist sentiment peaked following the 1992 recession and the controversy over Proposition 187, a 1994 California ballot initiative intended to prevent unauthorized immigrants from accessing social services, health care, and public education. Anti-immigration opinions ebbed during the economic boom of the late 1990s, rose briefly following the terrorist attacks and 2001 recession, then fell somewhat through 2008 (Figure 1). This pattern accords with claims that support for restriction of immigration rises as macroeconomic conditions deteriorate (Citrin et al. 1995). In July of 2008, 39 percent of US residents favored less immigration, 39 percent preferred current levels and 18 percent preferred increases in legal immigration (CBS News/NY Times 2008). By historical standards, these results show a relatively favorable national disposition toward immigration, which is remarkable given the changes in volume, composition, and settlement patterns of recent immigrants (for histories of opinion polling on immigration, see Simon 1985; Simon and Alexander 1993).

Figure 1. US Residents Preferring Decrease in Immigration.

Polls with Nationally Representative Adult Samples, 1982-2008

Source: Selected polls retrieved May 28, 2009 from the iPOLL Databank, Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut.

Evidence from public opinion polls that specifically gauge native attitudes toward immigration in new destinations, is limited, however. Hopkins (2007) claims that the opinions toward immigration of native residents in new immigrant destinations became more negative, relative to their peers elsewhere, but that this occurs when immigration is a politically salient issue nationwide.

In sum, the available evidence does not answer whether increases in the foreign-born population foster negative opinions about immigration in the new destinations, and has even less to say about variation in opinion is moderated by individual characteristics and group membership. Although national opinion polls show no growth in the proportion of residents favoring restriction of immigration, specific groups or residents of particular places may have grown more extreme in their opinions. If so, this might explain the rise in anti-immigration sentiment documented through other methods.

Our study measures individuals’ opinions regarding immigration using responses from a representative telephone survey to a variety of questions. By collecting information about respondents’ experiences and personal characteristics, we are able to model statistically the differences in opinion associated with theoretically relevant covariates. We then compare the pattern of associations in two matched counties, one that is a new immigrant destination and another that hosts relatively few immigrants. By doing so, we contribute information about how opinions about immigration may differ in places that have received immigration relative to those that have not, and provide a test of the mechanisms theorized to shape the opinions of natives citizens about immigration in the New Immigrant Destinations.

III. Opinions about Immigration: Theory and Evidence

Our study builds its theoretical framework from an extensive social science literature about how individual and group characteristics, as well as the broader context created by media, politics and the economy, influence perceptions of and attitudes toward minority groups, and recent immigrants in particular. Specifically, we first discuss the implications of prevailing theoretical perspectives for understanding native responses to new immigrants. Given the prominence and politicization of immigration in the national and local media in recent years, we also consider how publicity and politics influence public opinion about immigration.

Responses to Mass Immigration: Competition or Cooperation?

Numerous studies indicate that the size and growth of the foreign-born population is the lynchpin that shapes public attitudes toward immigration and perceptions of the new neighbors, but there is no clear consensus about the underlying mechanisms (for reviews see Espenshade and Hempstead 1996; and Hopkins, 2007). In fact, the dominant theoretical perspectives, dubbed the contact and threat perspectives, make opposite—but not incompatible—predictions about how the size and growth of a minority population influence opinions of the majority, or of more established minorities.

In its benevolent rendition, the contact perspective of inter-group relations implies that a growing foreign-born population is conducive to favorable opinions about immigrants and immigration because more direct exposure to immigrants in multiple social venues fosters acceptance and mutual understanding while also dispelling myths and unfounded fears about the newcomers. An important proviso is that contacts should be cooperative and that the newcomers do not compete with established native residents for power and resources (Lieberson 1961; Allport 1979). Thus, while the contact perspective implies that opinions about immigration should be more favorable as the foreign-born share of the population rises, this presumes that native residents do not perceive immigrants as a threat.

Perceptions are powerful predictors of human behavior. Therefore, if native residents perceive that immigrants are competing for jobs, housing, and social goods, inter-group contact may instead engender hostility. Originally developed to explain black-white relations (Blalock, 1967), the threat version of the contact hypothesis predicts that growth in the relative size of the foreign-born population in a local area fosters hostility among native residents due to perceived competition for power and resources (Blalock 1967; Bobo and Hutchings 1996). The threat perspective implies that natives living in communities that witnessed an increase in their foreign-born population will harbor more negative attitudes toward immigrants, compared with residents not directly impacted by the immigrant dispersal.

Although the inter-group contact and threat perspectives together have ambiguous predictions about native responses to foreign-born residents, mediating circumstances permit more nuanced predictions. Tolbert and Hero (2001), for example, find that support among whites for California’s anti-illegal immigration Proposition 187 was highest in counties with either very small or very large Hispanic populations, and lowest in counties with average size Hispanic populations. One interpretation of these findings is that moderate size minority populations permitted positive interactions between groups, but large minority populations resulted in threat.

The threat and contact perspectives also suggest hypotheses about how specific groups and individual natives will react to arrival of immigrants in their communities. In particular, the threat perspective raises the possibility that established minorities may perceive that immigrants undermine their precarious economic and political power; the contact perspective holds out the possibility that shared experiences of economic and political marginality can foster solidarity. In North Carolina, a prominent new destination state, the foreign-born and their children may not yet impact electoral politics, but competition likely occurs in other spheres (Marrow 2008, 2009). In many localities, immigrant workers visibly sustain and dominate employment in non-durable manufacturing and personal services industries (Fischer and Tienda 2006), creating potential for competition and conflict with less-skilled native workers and African Americans, even as they contribute to the overall welfare of their new communities. Housing and schools are other potential arenas for conflict, particularly in resource-strapped districts facing new fiscal outlays for special instructional needs, such as bilingual programs.

By focusing on how the costs and benefits of immigration are distributed, the political economy literature contributes a more specific version of the threat hypothesis. For example, native workers whose skills place them in direct economic competition with immigrants are more likely to harbor anti-immigration sentiments compared with potential beneficiaries, such as the affluent, owners of capital, and managers (Scheve and Slaughter 2001). Similarly, native residents who perceive their own economic situation or that of their community to be precarious or deteriorating will likely be less tolerant of immigration in the presence of a substantial foreign-born population.

There is mixed support for the threat perspective in the recent US immigration literature. Studying California’s Proposition 187, Alvarez and Butterfield (2000) find that natives who were pessimistic about the economy or felt threatened economically by immigration were more likely to support the ballot initiative. From national data, Espenshade and Hempstead (1993) and Pantoja (2006) find that the less-educated, as well as respondents who are most pessimistic about the economy and their own economic circumstances, are less supportive of immigration. By contrast, Citrin, et al. (1997) claim that personal economic circumstances have little influence on opinions about immigration, but anxiety over the national economy and taxes is associated with a more skeptical view of immigration.

Empirical consensus also is lacking regarding how exposure to immigrants influences attitudes toward immigration. For example, Dixon and Rosenbaum (2004; Dixon 2006) maintain that whites who directly interact with Hispanics in schools or their community have more positive views of them and that contacts with Hispanics dispel stereotypes, but contacts with blacks do not. Hood and Morris (2000) find that residence in densely-populated counties with substantial Hispanic and Asian populations is associated with lower support for the anti-immigration Proposition 187. Although suggestive, these findings are highly tentative because they are based on national data with little contextual information (Dixon and Rosenbaum); because they use indirect measures of contact, namely residence in counties with large minority populations (Hood and Morris); and because they draw inferences about attitudes toward immigration using ethnicity as a proxy.

Other studies indicate the importance of the nature of inter-group contact in moderating opinions, further demonstrating the importance of nuance in predicting whether contact triggers understanding or hostility. Stein, Post, and Rinden (2000) claim that attitudes toward minority groups depend on level of direct interaction. Specifically, they show that residence in a county with a high proportion Hispanic is associated with a more negative view of Hispanics among respondents who reported infrequent interactions with Hispanics, but a more positive view among those who reported frequent interactions. As expected, cooperative contact is conducive to positive views of the out group, while superficial or adversarial contacts usually foster negative attitudes.

The cooperative and competitive versions of the contact hypothesis have straightforward implications for native residents’ opinions about immigration in new destinations. Specifically, natives whose personal characteristics place them in competition with immigrants, or whose personal economic circumstances are precarious, will harbor more negative views of immigration in the county that has received immigrants compared with similar residents not directly impacted by a surge in the foreign-born population. A further implication is that sustained contact with immigrants will be associated with more positive views of immigration; however, superficial or sporadic interactions with immigrantswill be associated with negative views of immigration.

Indirect Contact: Media Exposure

That immigration is a high-profile national issue magnifies public responses, which are shaped by media images and narratives, according to Hopkins (2007). Simply stated, problems and controversies associated with immigration are more newsworthy than proposals for gradual integration of immigrants. The prominence of immigration as a national policy issue means that even residents whose first-hand experience with foreign-born residents form opinions based on what they hear or read. An especially promising theoretical insight concerns how media and political events influence local responses to immigration. Hopkins (2007) theorizes that both rapid growth of foreign-born population and prominent media coverage of immigration are necessary to trigger perceptions of threat among native residents. His “politicized change” perspective differs from conventional contact theory by emphasizing two new features—the pace of change in the foreign-born population (that is the intensity of the influx), rather than the size of the foreign-born population per se, combined with national media coverage of immigration as a social problem. For Hopkins, both conditions must be present to foster anti-immigration sentiment, which is a testable proposition if near-by localities that did and did not attract foreign-born residents can be compared.

Political Orientation

Political beliefs also may influence attitudes toward immigration by defining group membership, social values, and policy preferences. Advocates of limited government, for example, may view immigrants as a drain on public budgets, which acquires larger compass in light of immigrants’ geographic dispersal. The new settlement patterns re-distributed the fiscal impacts, previously concentrated among costal “blue” states, toward southern and midwestern states, and within states away from large metropolitan centers toward smaller urban and suburban places. Furthermore, if immigration activates values about national identity and foments divisions between in- and out-groups (Huntington 2004), reactions to immigration may be independent of actual exposure. This “symbolic politics” thesis, which helps explain why strong reactions to illegal immigration occur in places where few immigrants reside, finds support in recent political responses to immigration. Despite pervasive evidence that immigration poses no threat to the nation’s common language, many states and localities have passed “English-only” ordinances (Rodriguez et al. 2007; Citrin et al. 1990). By showing that humanitarian and egalitarian values predict support for immigrant admissions, Pantoja (2006) finds support for the symbolic politics thesis from the opposite direction.

Some studies reveal that beliefs and values are more powerful predictors of attitudes toward immigration than variables associated with direct contact or threat. For example, Ramakrishnan and Wong (2008) find that political party composition predicts the likelihood that local governments will initiate and pass immigration-related legislation. Studies about identity, political orientation and receptiveness to cultural change influence attitudes toward immigration, but the size and growth of the local immigrant population figures is of secondary importance. This research suggests that higher levels of political and social conservatism will be associated with less positive views of immigration, and that the magnitude of the association will not depend on the size of the foreign-born population.

Tolerance for Diversity

Evaluating contact hypotheses also requires that we consider how natives’ reactions are mediated by their individual characteristics and prior exposure to information about other groups (Alba, Rumbaut, and Marotz 2005). Building from evidence that education and exposure to other cultures raise tolerance for diversity and change, we expect a positive association between levels of education and positive attitudes toward immigrants (Espenshade and Hempstead 2006, Pantoja, 2006). A shared cultural heritage or recent immigrant ancestry also are associated with support for immigration (Espenshade and Hempstead 1993, Espenshade and Calhoun 1993). Haubert and Fussell (2006) find that a college education, a white collar occupation, experience living abroad, and rejection of ethnocentrism—all part of what they term a “cosmopolitan worldview”—are associated with more favorable opinions toward immigration. These findings suggest the testable proposition that more highly educated residents, those with an immigrant heritage, and those with more cosmopolitan experiences will harbor more positive views of immigration compared with their less educated counterparts, those with no immigrant heritage and limited exposure to communities beyond their own.

Our Contribution

Building on these myriad insights, we empirically evaluate which mechanisms, direct (contact and competition) vs. indirect (media) exposure to new immigrants explain native reactions to the growth of foreign-born residents in a specific, but highly relevant case. We test several hypotheses in a community that witnessed a growth in its foreign-born residents and a nearby, loosely matched county that attracted few immigrants. As such, our analysis is among the first to investigate the formation of opinions about immigration in one of the “new immigrant destinations.” The focused nature of the survey analyzed allows us to examine several aspects of inter-group relations between natives and immigrants in ways that general surveys about political and social attitudes cannot. Finally, we explore an aspect of opinion formation that has received limited analysis, namely whether the influence on opinions of selected respondent characteristics depends on residence in a community that has actually witnessed rapid demographic change.

IV. Study Sites

We analyze a unique randomized phone survey of US-born adults living either in Chatham County or Person County, North Carolina during summer, 2008. A total of 1,080 US-born adults (574 from Chatham County and 506 from Person County) participated in the phone survey. Response rates of 19.1 percent in Person County and 20.9 percent in Chatham County were not significantly different between the two counties (p = 10.1%).1 The survey was conducted during the US Presidential election campaign and about a year after a major immigration reform bill failed in the US Congress amid high-profile protests for and against. Stock market indices were well off the highs posted the previous summer and the 2008-09 recession was already underway (although not officially acknowledged). Data collection was complete well before widespread acknowledgement of the extent of the financial crisis and the resulting market crash in late September, 2008.

After eliminating cases with incomplete information, the analysis sample includes 998 observations. The survey obtained respondents’ race, occupation, social contact with immigrants, perception of the size of the local immigrant population, awareness of media coverage of immigration, and opinions about various national and local level immigration issues. Respondents who answered “Don’t Know” or refused to answer a question were assigned neutral answers as appropriate.

The two target counties were selected through a process designed to identify appropriate matched pairs of high and low immigration counties nationwide. The foreign-born made up less than 1 percent of the population of each county in 1980. A simple model based on county characteristics in 1980 and 1990 predicted that both Chatham County and Person County would experience high rates of growth in their foreign-born population over the next decade (Hanson 2007)2. By 2000, the foreign-born population of Chatham County rose to nearly nine percent of the population, primarily due to immigration from Mexico and Central America, while Person County’s foreign-born population share remained unchanged.

Person County and Chatham County share many key attributes that are relevant for immigration. Manufacturing employment in both counties is well above the national average—22 percent in Chatham versus 26 percent in Person—which is important because of the growing representation of foreign workers in manufacturing industries. Nonetheless, both counties witnessed declines in manufacturing employment between 20000 and 2007: 17 percent in Chatham County and 22 percent in Person County. Both counties border Durham County and are part of the Durham Metropolitan Statistical Area; both are served by the Durham Herald-Sun and several other regional newspapers and broadcast television and radio stations based in Raleigh-Durham or Greensboro. Each county also has several small local periodicals and at least one local radio station.

Despite these similarities, Chatham County and Person County differ in important ways. Table 1 shows select demographic information for the research sites based on the American Community Survey (ACS), and Table 2 presents key sample characteristics. Chatham County residents are, compared to Person county natives, better educated and average higher family incomes (Table 1). The proportion of residents who are black in Person County is about twice that of Chatham County, although this difference is smaller when only the native population is considered. In these two counties, the Hispanic population largely corresponds to members of households headed by immigrants, which accounts for Chatham County’s larger Hispanic population based on ACS data compared with our sample of US-born residents. Age structures of both counties are similar, however. The county samples capture these differences, although blacks are somewhat underrepresented in the Person County sample.

Table 1.

Key demographic characteristics of Person County and Chatham County, North Carolina, 2005-2007.

| Person County |

Standard Error, Person |

Chatham County |

Standard Error, Chatham |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population and income | ||||

| Total Population | 37,356 | * | 59,811 | * |

| Population growth, 2000-07 | 4.9% | * | 24.6% | * |

| Median family income | $48,877 | $4,070 | $63,410 | $5,624 |

| Selected Industries of Occupation | ||||

| Agriculture and mining | 3.5% | 0.9% | 1.9% | 0.7% |

| Construction | 11.0% | 2.6 | 9.9% | 1.9% |

| Manufacturing | 18.8% | 3.3% | 14.7% | 2.2% |

| Education and healthcare | 20.4% | 3.1% | 25.0% | 2.6% |

| Profession, scientific, and management services |

5.9% | 1.7% | 11.3% | 2.1% |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||||

| Black (Non-Hispanic) | 27.8% | 0.8 | 14.6% | 0.2% |

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 67.4% | 0.2 | 70.6% | 0.2% |

| Hispanic (Any Race) | 2.8% | * | 12.3% | * |

| Other (Non-Hispanic) | 2.0% | 0.3% | 3.7% | 0.2% |

| Education (age 25 and over) | ||||

| No HS degree or GED | 21.4% | 1.6% | 17.1 % | 1.2% |

| HS degree, GED, or some college |

65.8% | 2.2% | 49.5% | 1.8% |

| Bachelor’s or higher | 12.8% | 0.9% | 32.4% | 1.8% |

| Place of Birth | ||||

| Foreign-born | 2.6% | 2.6% | 10.7% | 0.8% |

| Born in North Carolina | 74.0% | 2.6% | 58.1% | 2.2% |

| Born in other US state | 23.3% | 0.5% | 30.3% | 2.1% |

Source: US Census Bureau estimates from the American Community Survey 2005-2007 and Census 2000.

= no sampling error information provided.

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics: Key Predictor and Control Variables, Person and Chatham Counties, North Carolina with T-tests for differences between counties.

| Variable | Person County N=506 |

Chatham County N=574 |

P-value, two-sided T-test |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 38.1% | 42.7% | 0.136 |

| Race and Ethnicity | Black (Non-Hispanic) | 17.3% | 11.0% | 0.003 |

| White (Non Hispanic) | 75.8% | 83.5% | 0.002 | |

| Hispanic | 2.3% | 1.4% | 0.316 | |

| Other race/ethnicity | 4.5% | 4.1% | 0.742 | |

| Education | No High School Degree | 9.1% | 6.0% | 0.053 |

| High School Degree, some college | 67.3% | 50.4% | 0.000 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 23.6% | 43.6% | 0.000 | |

| Age | Age 18 to < 35 | 11.4% | 8.5% | 0.114 |

| Age 35 to < 50 | 19.3% | 21.9% | 0.298 | |

| Age 50 to < 65 | 37.8% | 33.7% | 0.169 | |

| Age 65 and above | 29.3% | 32.2% | 0.311 | |

| Employment | Employed | 55.3% | 54.2% | 0.734 |

| Non managerial | 34.3% | 36.7% | 0.417 | |

| Managerial | 19.8% | 15.5% | 0.066 | |

| Unemployed | 2.6% | 2.8% | 0.855 | |

| Retired | 29.1% | 34.6% | 0.053 | |

| Not in Labor Market | 11.6% | 6.4% | 0.003 | |

| Competition Indicators | Parent of public school student | 19.6% | 13.2% | 0.005 |

| Finances are poor | 11.7% | 11.0% | 0.723 | |

| Direct Contact | Socialized with an immigrant | 28.5% | 38.9% | 0.000 |

| Worked with an immigrant | 31.6% | 36.8% | 0.076 | |

| Hears foreign language very often |

38.1% | 46.2% | 0.008 | |

| Hears foreign language at work very often |

20.2% | 21.3% | 0.658 | |

| Media Contact | Reads Newspaper Frequently | 38.7% | 45.8% | 0.019 |

| Watches “Lou Dobbs Tonight” | 27.3% | 28.0% | 0.776 | |

| Sees or hears Immigration in media several times a week |

49.2% | 55.2% | 0.048 | |

| Tolerance for diversity | Born outside North Carolina | 68.7% | 50.6% | 0.000 |

| Speaks a foreign language | 8.3% | 11.8% | 0.055 | |

| Has a foreign-born grandparent | 12.6% | 23.3% | 0.000 | |

| Political Orientation | Liberal | 7.1% | 17.9% | 0.000 |

| Moderate or apolitical | 61.5% | 52.1% | 0.002 | |

| Conservative | 31.4% | 30.0% | 0.604 |

Source: New Immigrant Destinations Project survey, August 2008.

Person County witnessed less population growth than Chatham County (Table 1). This is reflected in the survey data by the higher share of Chatham County natives who reported having been born outside North Carolina (Table 2). Voters in each county are about equally likely to register or identify as Democrats or Republicans, but at every education and income level Chatham County respondents were far more likely than Person County residents to describe themselves as “liberal” (Table 2). This corresponds with voting data from the 2004 Presidential Elections: John Kerry won 50 percent of votes in Chatham County, but only 41 percent in Person County.

Chatham County immigrants are concentrated around Siler City, attracted by job opportunities in its poultry processing plants, but the foreign-born are also dispersed in other areas of the county, where they find employment in construction, agriculture and service industries that hire unskilled workers. The educational profile of Chatham County’s Hispanics was very low in the 2000 Census: only 3.7 percent had a bachelor’s degree or more, and 70.5 percent had not graduated from high school.

In 2000, 85.6 percent of Chatham County’s foreign-born population was from Latin America, with 67.3 percent from Mexico and 14.2 percent from Central America. Only 49.6 percent of Person County’s immigrants were from Latin America. Asian-origin immigrants accounted for only 5.2 percent of Chatham County’s foreign-born, but 32.1 percent of the foreign-born in Person County, where 19.6 percent of the foreign-born population was from Vietnam. In 2000, 14.7 percent of Chatham County’s and 28.3 percent of Person County’s foreign-born population were naturalized citizens.

Immigration has been an active political issue in Chatham County since before 1999. In 2000, then Chair of the County Board of Commissioners Rick Givens provoked protests from state Hispanic advocacy organizations and a rebuke from the North Carolina Governor’s office for a letter requesting assistance in removing illegal immigrants, although he later adopted a more conciliatory approach to immigration (Viglucci 2000). In January 2008 Chatham County’s Board of Commissioners voted against participating in the federal 287(g) program, which trains local law enforcement officers to enforce federal immigration laws. As of August 2008, eight North Carolina jurisdictions, none of them in the study counties, participated in the program.

V. Analytic Strategy

Our primary goal is to evaluate variants of the contact hypothesis by investigating whether perceived threats, actual contact, or indirect exposure to foreign-born populations are associated with anti-immigration sentiments. Additionally, we evaluate the influence of personal characteristics, such as political alignment and tolerance for diversity, on attitudes toward immigration in the presence and absence of a local foreign-born population. After defining key theoretical constructs in operational terms, we compare mean values for the core theoretical constructs in each county. Using multivariate regression techniques, we show how the key constructs are associated with anti-immigration opinions in both counties. Finally, to evaluate which theoretical mechanisms are activated or aggravated by growth of the local immigrant population and/or direct contact with immigrants, we model interactions between Chatham County residence and key variables to test for differences in the association between these covariates and attitudes toward immigration, contingent on recent growth in the foreign-born population.

Our empirical strategy models differences in opinions about immigration among individuals, but cannot explain how variation in opinions about immigration arises at the county level. This is especially important given the differences in the composition of native populations of the two counties and direct exposure to immigrants by Chatham County residents. Therefore, we investigate how the estimated association between opinions about immigration and residence in Chatham County changes as theoretically important controls are introduced.

Dependent Variable: Immigration Problems Index

In order to capture natives’ general opinions about immigration, we created an index from responses to eight questions, listed below and summarized in Table 3. A numerical score was assigned to the ordinal responses (1 to 5, 1 to 3, or 1 to 10, depending on the number of implicit categories), with higher scores indicating that immigration was a more salient or more problematic issue, or a preference for fewer immigrant admissions. The “Immigration Problems Index” is an unweighted sum of the standardized scores for each question. Crohnbach’s alpha coefficient for the index is 0.79 and the mean inter-item covariance is 0.32. Alternative formulations of the index using different weightings of the scores derived from factor analysis and subsets of the eight variables were used to check the robustness of the multivariate estimates. Substantive results were unchanged.3 Responses to the following questions were used to develop the index:

Do you think the number of immigrants from foreign countries who are permitted to come to the United States to live should be decreased a lot, decreased a little, left the same as it is now, increased a little or increased a lot?

Now consider illegal or undocumented immigration as a national issue. On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is equal to unimportant and 10 is equal to very important, how would you rank the issue of illegal immigration?

And using the same scale, how would you rank the issue of illegal or undocumented immigration as a local issue? 1 being unimportant; 10 being very important.

Considering legal immigrants, do you think that today’s legal immigrants pay their fair share of taxes, or not? (No, Don’t know, or Yes)

What about undocumented immigrants -- do you think that they pay their fair share of taxes? (No, Don’t Know, or Yes)

Consider the statement that more good jobs for immigrants means fewer good jobs for American citizens. Would you say you agree strongly, agree somewhat, neither agree nor disagree, disagree somewhat, or disagree strongly?

Consider the statement that having more students from immigrant backgrounds makes it more difficult for schools to teach all children. Would you say you agree strongly, agree somewhat, neither agree nor disagree, disagree somewhat, or disagree strongly?

On balance, do you think immigration into the United States is good, bad, or doesn’t make much difference?

Table 3.

Perceptions of immigration in Person County and Chatham County: Immigration Problems Index and its components

| Item | Person County mean value (S.D) |

Chatham County mean value (S.D.) |

P-value, two- sided T- test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immigration Problems Index (1 = least problematic, 10 = most problematic) |

7.21 (1.98) |

6.43 (2.30) |

0.000 |

| Preferred number of immigrant admissions (1 =Increased Greatly, 5= Decreased Greatly) |

3.71 (1.08) |

3.40 (1.23) |

0.000 |

| Good jobs for immigrants means less good jobs for Americans ( 1= disagree strongly, 5 = agree strongly) |

3.46 (1.49) |

3.14 (1.52) |

0.001 |

| More immigrant students make it more difficult for teachers to educate all students ( 1= disagree strongly, 5 = agree strongly) |

3.94 (1.35) |

2.82 (1.42) |

0.123 |

| Importance of illegal immigration as national issue (1 = Not important, 10 = Most important) |

8.60 (2.28) |

8.13 (2.43) |

0.001 |

| Importance of illegal immigration as local issue (1 = Not Important, 10 = Most important) |

7.73 (2.76) |

7.89 (2.56) |

0.326 |

| Legal immigrants pay fair share of taxes (1 = Yes, 2= Don’t Know, 3 = No) |

2.13 (0.89) |

1.76 (0.87) |

0.000 |

| Unauthorized immigrants pay fair share of taxes (1 = Yes, 2= Don’t Know, 3 = No) |

2.78 (0.55) |

2.59 (0.71) |

0.000 |

| Immigration is good (1) bad (3), or neutral (2). | 2.17 (0.81) |

1.88 (0.87) |

0.000 |

Source: New Immigrant Destinations Project survey, August 2008.

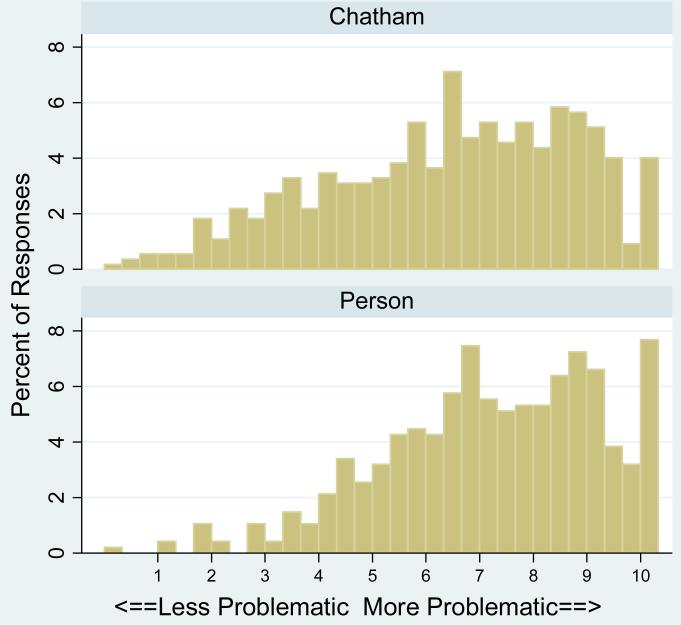

On six of the eight items, respondents from Chatham and Person Counties provided significantly different answers (Table 3). Respondents from both counties agree that the presence of larger numbers of immigrants increase instructional challenges for teachers. Further, residents of both counties report that illegal immigration is an equally important local issue, despite the fact that Person County was not impacted by immigration. The composite Immigration Problems Index shows that residents of Person County harbor more negative perceptions of immigration compared with Chatham County respondents (Figure 2, Table 3). At face value, this raw difference lends support to claims that direct exposure dispels myths about immigrants and potentially fosters understanding of immigration, but differences between counties in average education and political orientation indicate that other mechanisms might be responsible for average differences in perceptions. The final stage of the analysis considers this possibility.

Fig. 2.

Immigration Problems Scale by County

Predictor Variables

The theoretical discussion identified several factors that predict opinions about immigrants. These include threat of competition, the nature of inter-group contact, media exposure, tolerance for diversity and political orientation. Several hypotheses implicate more than one of these social influences, however. Table 2 summarizes the key predictor variables, which we describe below.

Threat

Because most direct competition takes place in the labor market via displacement or wages, we use several measures of labor market status to capture perceived threat. As the quotes in the introduction indicate, rapid growth of foreign-born populations may also activate competition in schools (for teacher’s time and other resources), which we represent with an indicator for parents of school-aged children. Self reports of precarious financial circumstances gauge respondents’ vulnerability to competition from foreigners and perceptions of threat. Unadjusted mean differences show considerable similarity between respondents from Chatham and Person County, with several notable exceptions (Table 2). There were twice as many respondents out of the labor force but not retired in Person compared with Chatham County. A larger share of Person County respondents holds managerial positions and Chatham County respondents are more likely to be retired. Finally, Person County residents are also significantly more likely than their Chatham County counterparts to report having children enrolled in the public schools.

Education also influences perceived economic competition and threat as well as tolerance for diversity. A political economy perspective predicts that job and resource competition will be greatest among native residents with educational profiles most similar to the foreign-born. Lack of a high school degree or GED is thus a key competition indicator.

Inter-Group Contact

To assess whether intergroup contact is associated with positive perceptions of immigration, we use several measures of actual contact and exposure to immigrants. These include whether respondents socialized with an immigrant outside of the workplace; had contact with an immigrant on the job; and reported hearing non-English languages spoken frequently in their community or at work. Chatham County’s immigrant influx is reflected in the significantly higher shares of residents who report socializing with an immigrant outside of work, as well as more frequent exposure to non-English language in the community (but not in the workplace).

Indirect Exposure: Media

We measure respondents’ indirect exposure to immigrants and immigration issues using indicators of media consumption habits and frequency with which immigration appears in the news. Respondents from our comparison counties differ both in their frequency of newspaper reading and their awareness of immigration themes in media. Just over one-quarter of respondents from both counties reported watching “Lou Dobbs Tonight” (a news commentary show on CNN that frequently covered immigration and consistently framed it as a problem). 4

Tolerance for Diversity

To capture variation in tolerance for diversity, we use three indicators of a respondent’s breadth of experience: whether the respondent was born outside of North Carolina; speaks a foreign language; and has a foreign-born grandparent. Education also influences understanding of diversity. Better educated respondents presumably are more adaptable to social change, including ethnic transformation of their communities. In particular, college-educated residents are likely to be more accepting of immigrants than their less educated counterparts.

Political Orientation

Political orientation is measured using a self-characterization as politically liberal, conservative, or moderate or apolitical. Exploratory analysis revealed this measure to better predict immigration attitudes than party preference. About one-third of respondents from each county self-identified as conservative, but Chatham County respondents are over twice as likely as Person County residents to identify as liberal (18 versus 7 percent). Person County respondents are thus significantly more likely to identify as politically moderate or apolitical than Chatham County residents.

VI. Results

Table 4 reports multivariate regression estimates predicting opinions toward immigration, as measured by an index that characterizes immigration as a social problem. High values indicate more problematic opinions about immigration. As expected, a liberal political orientation and measures of tolerance for diversity are associated with more favorable views of immigration. Coefficients associated with having a college degree, being born outside of North Carolina, speaking a foreign language, and identifying as politically liberal are all negative and statistically significant. Results also support claims that intergroup personal contact fosters acceptance of immigrants. Both socializing and working with an immigrant are associated with more benign views of immigration. Not all inter-group contacts are positive, however. Reporting frequent foreign language use in the community is associated with a more problematic view of immigration (Table 4).

Table 4.

Regression of Immigration Problems Index (1 = least problematic, 10 = most problematic) on key predictors, with robust standard errors.A

| Variable | OLS Coef. | S.E. | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

County of

Residence |

Person | -- | -- |

| Chatham | −0.202 | −0.128 | |

| Gender | Female | -- | -- |

| Male | −0.307* | −0.125 | |

|

Race and

Ethnicity |

White (non-Hispanic) | -- | -- |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | −0.093 | −0.177 | |

| Hispanic and other | −0.754^ | −0.406 | |

| Education | No High School Degree | 0.173 | −0.248 |

| High School, GED, some college | -- | -- | |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | −0.887** | −0.147 | |

| Employment | Non-managerial worker | -- | -- |

| Managerial worker | 0.218 | −0.172 | |

| Unemployed | 0.288 | −0.333 | |

| Retired | −0.301 | −0.208 | |

| Not in Labor Market | −0.175 | −0.248 | |

|

Competition

Indicators |

Parent of public school student | 0.466* | −0.19 |

| Own Finances are bad | 0.126 | −0.204 | |

|

Direct

Contact with Immigrants |

Socialized with an immigrant | −0.754** | −0.134 |

| Worked with an immigrant | −0.498* | −0.217 | |

| Hears foreign language very often | 0.504** | −0.128 | |

| Hears foreign lang. at work very | 0.358 | −0.221 | |

| Media | Reads Newspaper Frequently | −0.328* | −0.132 |

| Watches “Lou Dobbs Tonight” | 0.326* | −0.132 | |

| Immig. in media several times | 0.106 | −0.125 | |

|

Tolerance for

Diversity |

Born outside North Carolina | −0.472** | −0.144 |

| Speaks a foreign language | −0.572* | −0.231 | |

| Has a foreign-born grandparent | −0.094 | −0.176 | |

|

Political

Orientation |

Liberal | −1.395** | −0.215 |

| Moderate | -- | -- | |

| Conservative | 0.396** | −0.134 | |

| N | 998 | ||

| r2 | 0.30 |

Model includes dummy variables for age, coefficients not shown

p <.01

p<.05

p<.10

Source: New Immigrant Destinations Project survey, August 2008.

Media consumption also predicts opinions about immigration. Viewing “Lou Dobbs Tonight” is associated with a more problematic view of immigration, while frequently reading a newspaper (perhaps a more nuanced source of information about immigration) is associated with a more benign view. It is unclear, however, whether respondents with less favorable opinions are more likely to watch Lou Dobbs, or vice-versa.

The “threat” hypothesis finds very limited support. Parents of a school-age child are more likely to harbor negative views of immigration than residents whose families are not directly involved in schools. Other predictor variables implicated in intergroup competition, most notably being black, unemployed or having no high-school degree, show no significant association with views of immigration.

County Differences in Opinion Formation

Our theoretical arguments posit that opinions about immigration will differ between residents whose communities were directly impacted by immigration and those whose exposure is only indirect, because specific mechanisms of opinion formation will be activated when a large immigrant population is present. Lacking before-and-after data on opinions in these two counties or a true counterfactual, we cannot directly assess how opinions have changed as a result of immigration. Instead, we examines differences in the association between opinions and various characteristics and experiences, knowing that the dramatic recent immigration to Chatham County is perhaps the most substantial and relevant, but hardly the only, difference between the two counties. Results reported in Table 5 reveal few significant differences between the two counties in the associations between opinions about immigration and the key predictor variables.

Table 5.

Regression of Immigration Problems Index (1 = least problematic, 10 = most problematic) on key predictors and their interaction with residence in Chatham County, with robust standard errors.A

| Variable | Main Effect | S.E. of Main Effect |

Interaction with Chatham County |

S.E. of Inter- action |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

County of

Residence |

Person | -- | |||

| Chatham | −0.127 | −0.374 | |||

| Gender | Female | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Male | −0.159 | −0.186 | −0.294 | −0.251 | |

|

Race and

Ethnicity |

White (non-Hispanic) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | −0.121 | −0.237 | 0.056 | −0.354 | |

| Hispanic and other | −0.379 | −0.562 | −0.603 | −0.814 | |

| Education | No High School Degree | −0.042 | −0.324 | 0.441 | −0.490 |

| High School, GED, some college | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | −0.664** | −0.221 | −0.238 | −0.302 | |

| Employment | Non-managerial worker | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Managerial worker | 0.406 | −0.251 | −0.382 | −0.343 | |

| Unemployed | 0.091 | −0.551 | 0.231 | −0.688 | |

| Retired | 0.098 | −0.277 | −0.595 | −0.363 | |

| Not in Labor Market | −0.102 | −0.346 | −0.223 | −0.486 | |

|

Competition

Indicators |

Parent of public school student | 0.523* | −0.242 | −0.135 | −0.358 |

| Own Finances are bad | −0.431 | −0.304 | 1.089** | −0.392 | |

|

Direct

Contact with Immigrants |

Socialized with an immigrant | −1.104** | −0.212 | 0.674* | −0.274 |

| Worked with an immigrant | −0.580^ | −0.332 | 0.057 | −0.442 | |

| Hears foreign language very | 0.266 | −0.187 | 0.375 | −0.254 | |

| Hears foreign lang. at work very often |

0.615^ | −0.343 | −0.378 | −0.450 | |

| Media | Reads Newspaper Frequently | −0.368* | −0.185 | 0.068 | −0.261 |

| Watches “Lou Dobbs Tonight” | 0.235 | −0.195 | 0.256 | −0.261 | |

| Immig. in media several times weekly |

0.186 | −0.185 | −0.225 | −0.251 | |

|

Tolerance for

Diversity |

Born outside North Carolina | −0.547* | −0.214 | 0.205 | −0.288 |

| Speaks a foreign language | −0.648 | −0.397 | 0.173 | −0.478 | |

| Has a foreign-born grandparent | 0.14 | −0.307 | −0.371 | −0.376 | |

|

Political

Orientation |

Liberal | −0.429 | −0.421 | −1.382** | −0.487 |

| Moderate | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Conservative | 0.277 | −0.193 | 0.156 | −0.271 | |

| N | 998 | ||||

| r2 | 0.33 |

Model includes dummy variables for age, coefficients not shown

p <.01

p<.05

p<.10

Source: New Immigrant Destinations Project survey, August 2008.

A few noteworthy differences emerge, however. One is the difference in the association between reporting financial insecurity and the Immigration Problems Index. There exists a positive association between financial insecurity and more problematic views of immigration in Chatham County, but not in Person County. Retired respondents express a more benign view of immigration relative to non-managerial workers, but only in Chatham County. Thus, there is some evidence that economically insecure residents feel threatened by local immigration, or partly blame immigrants for their economic plight when immigrants are present locally. Although the opinions of workers and retirees appear to differ in the county impacted by immigration, but not in the comparison, we find no evidence that competition and threat better explain opinions about immigration among Chatham compared with Person County residents.

Chatham County parents of school-aged children do not harbor more problematic views of immigration than their Person County counterparts. Given the overall association between parental status and more problematic immigration attitudes, this is surprising. About one-third of Person County parents reported that over 10 percent of their child’s class consisted of immigrant students. Thus, Person County parents may perceive competition in schools despite the small number of county residents who are immigrants or children of immigrants. Whether accurate or not, perceptions shape attitudes.

The hypothesis that the association between media coverage of immigration and attitudes toward immigration depends on the intensity of immigration is not supported. Associations between media consumption and opinions about immigration are essentially similar in both counties, contrary to Hopkins’s (2007) claim that the intersection of media coverage and demographic change produces negative reactions to immigration.

Analyses also produced a few unexpected results. Liberal respondents harbored less problematic views of immigration, relative to residents with a moderate political orientation or who considered themselves apolitical, but only in Chatham County. Two explanations for this association seem plausible. First, local immigration may polarize opinions about immigration, increasing the difference in opinions between liberals and moderates. Second, liberals in Chatham County may be, on average, “more liberal” than liberals in Person County. Not only are there many more liberals in Chatham compared with Person County, but Chatham County liberals, like residents of Chatham County generally, are more likely to have been born outside of North Carolina. Thus, Chatham County liberals may represent a different set of experiences and political attitudes than Person County’s liberals.

Another unexpected result is the weaker association between socializing with an immigrant and a more benign view of immigration for Chatham County compared with Person County. Again, unobserved heterogeneity may be implicated. Natives socializing with immigrants in a county with relatively few foreign-born residents may be predisposed to extremely positive views of immigration. Alternatively, natives in a high-immigration county may have other opportunities to gather information about immigration, lessening the importance of direct social contacts. These conjectures warrant further scrutiny, however.

Differences in Opinions about Immigration between Chatham and Person County

Residents of Person County view immigration more problematically than residents of Chatham County (Table 3, Figure 2). More Person County residents scored a maximum score of “10” on the Immigration Problems Index and fewer had benign views of immigration (Fig. 2). This county-level difference argues against the blunt hypothesis that broad competition and threat are responsible for highly negative views of immigration in new immigrant settlement areas, which predicts the opposite.

In the absence of extensive differences between counties in associations between the social forces theorized to shape views of immigration, we consider two plausible explanations for why residents of the low immigration county articulate more negative views than residents of the county where the foreign-born population surged. The first is that the compositions of the two counties’ native populations differ systematically in ways that predict divergent views. That larger shares of Chatham County residents have college degrees, were born out-of-state and identify as liberals compared with Person County is particularly important. The second explanation revolves around the contact hypothesis. Natives in Chatham County have much greater opportunity to interact with immigrants and a greater proportion report doing so, compared with Person County. Our analysis indicates that some of these contacts are associated with a more benign view of immigration; hence it is plausible that the larger number of contacts with immigrants in Chatham County partly account for the opinion gap between the two counties.

The estimated association between residence in Chatham County, relative to Person County, and a more benign view of immigration is greatly decreased when controls for political orientation, tolerance for diversity, and education are introduced (In Table 6, Model Two versus Model One). Including controls for contacts with immigrants also attenuates the association between the county of residence and scores on the Immigration Problems Index, (Model Three versus Model One), but to a much smaller degree. Thus, differences in population composition most likely explain the large difference in opinions about immigration in the two counties.

Table 6.

Estimated difference between responses of Person and Chatham County residents on the Immigration Problems Index (1 = least problematic, 10 = most problematic) when controlling for different sets of variables, using OLS regression.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chatham County coefficient | −0.760** | −0.255* | −0.650** | −0.202 |

| S.E. | −0.136 | −0.128 | −0.132 | −0.128 |

|

| ||||

| Sets of Control Vectors (x = included) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Gender and Age | X | X | X | X |

| Race and Ethnicity | X | |||

| Education | X | X | ||

| Employment | X | |||

| Competition | X | |||

| Direct Contact with Immigrants | X | X | ||

| Media | X | |||

| Tolerance for Diversity | X | X | ||

| Political Orientation | X | X | ||

| N | 998 | 998 | 998 | 998 |

| r2 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.3 |

p <.01

p<.05

p<.10

Source: New Immigrant Destinations Project survey, August 2008.

Limitations

Our cross-sectional data do not allow us to claim that the differences we observe between the two counties are exclusively the result of immigration to Chatham County. The two counties differ in many important ways other than their very different immigration experiences and we do not claim that Person County represents a true counterfactual - a Chatham County sans immigration.

Another significant limitation of our analysis is that several operational measures are based on self-reports and are subject to selection bias, which render the direction of causal pathways ambiguous. Native residents with more problematic views of immigration may chose to watch Lou Dobbs Tonight, rather than the program influencing their opinions. Natives may be more sensitive to use of foreign language in public spaces if they disapprove of immigration. Finally, although we argue that these two North Carolina counties are a good testing ground for theories regarding opinion formation in new immigrant destinations, higher external validity requires replication beyond this new immigration state.

VII. Discussion

We present one of the first analyses of the social factors that influence native residents’ opinions about immigration in a new immigrant destination, making a novel comparison between two geographically proximate and loosely matched counties that did and did not receive immigration. There is no sign that widespread hostility towards immigration followed the growth of the foreign-born population. Indeed, native residents in the county that witnessed an increase in its foreign-born population viewed immigration more benignly compared with residents in the county that did not. Differences in the population characteristics of the two counties largely explain this result. There is suggestive evidence that contacts between natives and immigrants, when they are more sustained than merely passing in the street or grocery store, foster a benign view of immigration. Policies intending to bolster support for immigrants in new destinations would do well to focus on promoting such interactions. As important, the hypothesis that natives would broadly sense competition and threat from immigration is not supported.

Our analysis also reveals points of friction. Native residents in dire economic straits appear especially prone to view their new immigrant neighbors in negative ways. That parents have a more negative view of immigration in both counties compared with nonparents suggests that schools are a site of perceived competition for teacher’s time and for educational resources. These results are worrisome in light of the current recession, which raises the risk for conflict between immigrants and natives as more people feel economically insecure and local resources shrink. Other researchers should take note of our finding that political orientation and the predisposition of natives to tolerate diversity are extremely important in both counties. Finally, our results suggest that opinions about immigration among people of different political orientations may be aggravated by the rapid growth of immigrant population in nontraditional destinations. These results warrant more extensive exploration in light of the extensive political and educational differences between populations in the new and traditional immigrant destinations.

Acknowledgments

The data collection was supported by a grant from the Russell Sage Foundation. We acknowledge institutional support from the Office of Population Research, and NIH (#5 T32 HD007163 and #5 R24 HD047879).

Footnotes

Response rates are calculated according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research’s “RR3”: completed interviews over estimated contacts with eligible units (American Association for Public Opinion Research 2009).

Predictor variables in this model include 1980 to 1990 change in foreign-born, black, and Hispanic population shares, 1990 employment shares in nondurable manufacturing and agriculture, share of the population that owns its own home, 1980 to 1990 change in median home value, and 1980 to 1990 change in country population. The universe of the model was counties in the South located within Metropolitan Statistical Areas and having 2000 populations between 25,000 and 75,000 people. This model can account for about 52 percent of variation in 1990 to 2000 percent change in the share of the county population that is foreign-born. Chatham County and Person County were both in the top 20% of these 152 counties in terms of predicted change in foreign-born share of the population according to this model. Chatham County and Person County were selected from among this top fifth because they were geographically proximate to each other.

The dependent variable and many of its component items show signs of censoring for respondents with the most negative view of immigration, especially in Person County (Figure 2). Tobit models were used in robustness testing, with no substantive difference relative to OLS. For ease of interpretation, we present OLS models with Huber-White standard errors generated using Stata’s “robust” option.

Lou Dobbs resigned his position in fall, 2009, under pressure from Hispanic and immigrant advocate groups.

A version of this paper was presented at the 2009 annual meetings of the Population Association of America, Detroit.

References

- Alba, Richard, Rumbaut Ruben, Marotz Karen. A Distorted Nation: Perceptions of Racial/Ethnic Group Sizes and Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Other Minorities. Social Forces. 2005;84:901–919. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, Gordon W. The Nature of Prejudice. 25th ed. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, Michael R, Butterfield Tara L. The Resurgence of Nativism in California? The Case of Proposition 187 and Illegal Immigration. Social Science Quarterly (University of Texas Press) 2000;81:167–179. [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Public Opinion Research . Standard Definitions:Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 6th edition American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Cynthia D. The Social Consequences of Economic Restructuring in the Textile Industry: Change in a Southern Mill Village. Garland Pub.; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Ellen The Nation; City’s immigration law turns back clock; Latinos leave Hazleton, Pa., in droves in the old coal town’s crackdown. Los Angeles Times. 2006 Nov 9;:A.10. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Mary, Reynolds Sarah. Under Siege: Life for Low-Income Latinos in the South. Southern Poverty Law Center; Mongomery, AL: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- CBS News/NY Times . Survey by CBS News/New York Times, July 7-July 14, 2008. [Accessed June 22, 2009]. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Citrin, Jack, Green Donald P., Muste Christopher, Wong Cara. Public Opinion Toward Immigration Reform: How Much Does the Economy Matter? Center for Latino Policy Research; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Citrin, Jack, Green Donald P., Muste Christopher, Wong Cara. Public Opinion Toward Immigration Reform: The Role of Economic Motivations. The Journal of Politics. 1997;59:858–881. [Google Scholar]

- Citrin, Jack, Reingold Beth, Walters Evelyn, Green Donald P. The ”Official English“ Movement and the Symbolic Politics of Language in the United States. The Western Political Quarterly. 1990;43:535–559. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Jeffrey C. The Ties That Bind and Those That Don’t: Toward Reconciling Group Threat and Contact Theories of Prejudice. Social Forces. 2006;84:2179–2204. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Jeffrey C, Rosenbaum Michael S. Nice to Know You? Testing Contact, Cultural, and Group Threat Theories of Anti-Black and Anti-Hispanic Stereotypes. Social Science Quarterly. 2004;85:257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Espenshade, Thomas J, Calhoun Charles A. An analysis of public opinion toward undocumented immigration. Population Research and Policy Review. 1993;12:189–224. [Google Scholar]

- Fennelly, Katherine . Prejudice Toward Immigrants in the Midwest. In: Massey Douglas S., editor. New Faces in New Places. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Mary, Tienda Marta. Redrawing Spatial Color Lines: Hispanic Metropolitan Dispersal, Segregation, and Economic Opportunity. In: Tienda Marta, Mitchell Faith., editors. Hispanics and the Future of America. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. p. 490. [Google Scholar]

- Gozdziak, Elzbieta M, Martin Susan Forbe, editors. Beyond the Gateway: Immigrants in a Changing America. Lexington Books; Lanham: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Haubert, Jeannie, Fussell Elizabeth. Explaining Pro-Immigrant Sentiment in the U.S.: Social Class, Cosmopolitanism, and Perceptions of Immigrants. International Migration Review. 2006;40:489–507. [Google Scholar]

- Hood III, V. M, Morris Irwin L. Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? Racial/Ethnic Context and the Anglo Vote on Proposition 187. Social Science Quarterly. 2000;81:194–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, Daniel Threatening Changes: Explaining Where and When Immigrants Provoke Local Opposition. 2007 http://people.iq.harvard.edu/~dhopkins/immpapdjh.pdf.

- Huntington, Samuel P. Who Are We?: The Challenges to America’s National Identity. Simon & Schuster; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Thomas Danbury Council Vote on Policing Immigrant Community Draws Thousands to Protest. New York Times. 2008 Feb 7;:B.3. [Google Scholar]

- Lagalaron, Laureen, Rodriguez Cristina, Silver Alexa, Thamasombat Sirithon. Regulating Immigration at the State Level: Highlights from the Database of 2007 State Immigration Legislation and the Methodology. Migration Policy Institute; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]