Abstract

Background

Numerous publications demonstrate the importance of community-based participatory research (CBPR) in community health research, but few target the Deaf community. The Deaf community is understudied and underrepresented in health research despite suspected health disparities and communication barriers.

Objectives

The goal of this paper is to share the lessons learned from the implementation of CBPR in an understudied community of Deaf American Sign Language (ASL) users in the greater Rochester, New York, area.

Methods

We review the process of CBPR in a Deaf ASL community and identify the lessons learned.

Results

Key CBPR lessons include the importance of engaging and educating the community about research, ensuring that research benefits the community, using peer-based recruitment strategies, and sustaining community partnerships. These lessons informed subsequent research activities.

Conclusions

This report focuses on the use of CBPR principles in a Deaf ASL population; lessons learned can be applied to research with other challenging-to-reach populations.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, health disparities, vulnerable populations, academic medical centers, health care facilities manpower and services, Deaf American Sign Language users

CBPR integrates educational and social action in research through the active and equitable involvement of community members and researchers. CBPR generates both opportunities and challenges for researchers in addressing health disparities in targeted communities.1–3 Benefits of CBPR include the empowerment of the community’s ability to vocalize and address its health needs, the use of community’s strengths and resources to initiate and conduct research, and the recognition of the community as a partner in research and public health.2 Challenges include adequate time and resources required for the development of relationships between an institution and community and meeting varied cross-cultural expectations and demands emanating from research institutions, Human Subjects Protection Boards, community members, and partnering organizations.3–7

CBPR efforts are recognized as critical in addressing health issues in understudied minority populations. 7–10 The Deaf ASL community refers to Deaf individuals who use ASL as their primary language, and constitute a group of individuals who identify themselves as a minority entity, with their own unique language and culture.11,12 ASL is commonly misunderstood to be a gestural language or a visual “English” language representing spoken English. ASL contains its own syntax and language structure, which is distinct from English. Deaf ASL users share a set of values, customs, attitudes, and experiences that contrast with the hearing world.13 Approximately 500,000 Deaf ASL users are believed to exist in the United States.14,15

A lack of understanding of cultural and linguistic differences create barriers for many health researchers and research teams who work with Deaf signers. The Deaf community historically has been marginalized and excluded from health surveys and surveillance systems owing to literacy barriers and inability to understand spoken English (e.g., phone surveys).16,17 Communication and language barriers have historically isolated the Deaf community from health education and outreach programs and mass media healthcare messages, which affects health outcomes and health care access.18–23 Research on Deaf ASL is lacking, but in one study using national data, individuals with significant hearing loss were more likely than hearing individuals to be publicly insured, unemployed, less educated, and have lower incomes.24 Studies involving local Deaf communities show similar findings of low income20,25 and educational achievement.20

The University of Rochester Prevention Research Center identified the Rochester Deaf Community in New York as an underserved community to target for further research collaboration. After funding was obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2004, the National Center for Deaf Health Research (NCDHR) was formed to address health inequities and gaps in health surveillance data within the Deaf community.20,26–31 The aim of this paper is to share the lessons learned from a CBPR approach to engage the Rochester Deaf community in an effort to overcome some of these health barriers.

Methods

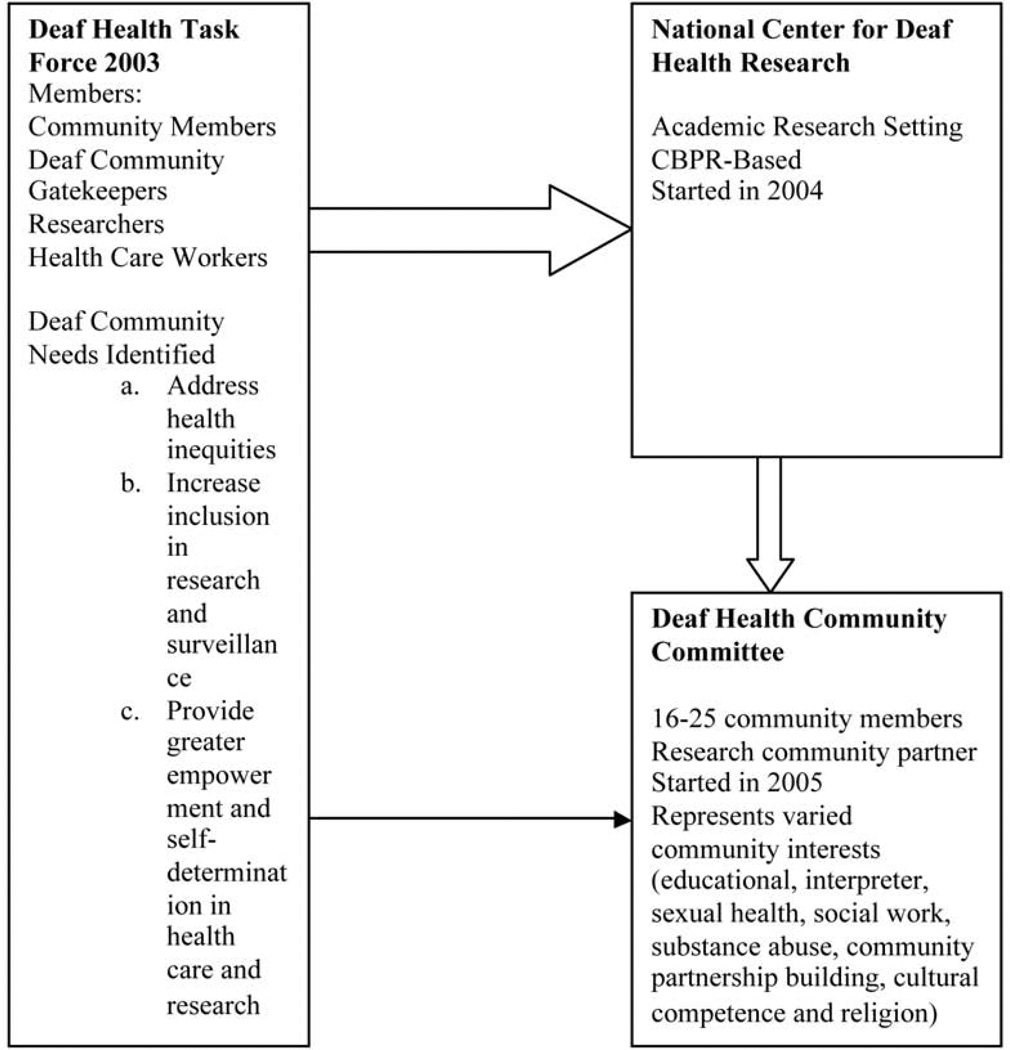

The establishment of the CBPR-based research center to address Deaf health inequities involved multiple steps and the efforts of both Deaf community partners and research faculty. In 2003, the Deaf Health Task Force was formed to discuss barriers to health care within the Rochester Deaf Community.32 This group identified key factors that raised the need to establish NCDHR in the Rochester area (Figure 1). The NCDHR partnered with health, educational, community service organizations to develop a research center to address the needs of the community.

Figure 1.

Establishment of a CBPR-Based Deaf Health Research Center

To facilitate engagement between the Deaf community and the research center, a number of methods were implemented (Table 1). An important step was the transition of the Task Force into the Deaf Health Community Committee (DHCC; Figure 1) to function as a community partner of NCDHR. Many of the DHCC members also served on Deaf educational institutions (e.g., National Technical Institute for the Deaf), service organizations (e.g., Vocational and Educational Services for Individuals with Disabilities), community organizations (e.g., Advocacy Services for Abused Deaf Victims), recreational clubs (e.g., Rochester Recreation Club for the Deaf and Deaf Women of Rochester), and religious groups (e.g., Deaf churches). The DHCC members represented varied community interests (Figure 1) that proved invaluable as research partners.

Table 1.

Communication Methods Between Researchers and the Deaf Community

| Communication Mode | Specific Types |

|---|---|

| Face-to-face | Town hall meetings |

| communication | One-on-one meetings |

| DHCC and NCDHR meetings | |

| Health outreaches | |

| Research presentations | |

| Community events and booths | |

| Sign language interpreters | |

| Sign language fluent staff | |

| Social media | Twitter34 |

| Facebook35 | |

| Technology | NCDHR website |

| Video blogs (“vlogs”) | |

| Videophones | |

| Short films in sign language | |

| Mail-based information | Newsletters |

| Listserves | |

| Mailings | |

Starting in 2004, NCDHR research activities focused on developing surveillance instruments accessible in ASL and Signed English (reflects the grammar structure and wording of English rather than ASL) for Deaf persons. A translation work group utilized community members’ expertise to adapt survey instruments, including the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) into an ASL format using a touch-screen kiosk with video, to make them linguistically and culturally appropriate.33 The Deaf Health Survey (DHS), an adapted and translated BRFSS, was disseminated to the greater Rochester community in 2008. DHS findings were shared with the Deaf community in 2008 and 2009 to identify health priorities for the next grant cycle, marking the first time the Deaf community used its own data to identify community priorities.25

The DHS findings were qualitatively compared with the Monroe County BRFSS results to demonstrate areas of concern. The Deaf community and the research team agreed to focus on three pressing health concerns: Obesity (34.2% of Deaf participants versus 26.6% among hearing participants); interpersonal violence, including physical abuse in their lifetime (21.0% vs. 13.9%); and attempted suicide in the past year (2.2% vs. 0.4%).25 Intervention studies addressing all three health priorities are currently underway. All NCDHR research activities are approved by the Research Subjects Review Board.

Lessons Learned From the Implementation of CBPR at the NCDHR

Engage and Educate the Community about Research

Many research studies have failed to fully engage the Deaf community, leading to confusion, mistrust, and refusal to participate in the research process22 and a cross-cultural conflict between the Deaf and research communities (Figure 2). Many Deaf individuals lack understanding of the risks and benefits of research participation and how their participation can help reduce disparities in their communities.

Figure 2.

Challenges with Deaf Community Health Research

The NCDHR partnered with the DHCC to raise research knowledge and interest among Deaf community members. DHCC members were encouraged to pass an Ethical Principles in Research Program examination before they could become involved with the research process. The high level of written English proficiency required by the examination posed a barrier for many Deaf members. The DHCC, with NCDHR’s support, created a research ethics training class in ASL that reviewed the contents of the Ethical Principles in Research Program for all DHCC members.34 The process of delivering accessible research materials not only allowed community members to become active collaborators with the researchers, it also increased their understanding of the academic research environment.

To minimize mistrust, the NCDHR met monthly with the DHCC and provided a series of ASL-accessible town hall meetings and video-based blogs (vlogs; Table 2). Deaf individuals, regardless of age or background, are frequently savvy with new technology, including the use of “smartphones,” social media, and videophones (i.e., video-based phones that use a TV and Internet connection). These tools help to remove communication barriers and provide a way to disseminate information quickly and effectively. Social media tools, primarily Twitter and Facebook, helped to inform and recruit participants for existing research projects based on findings from the DHS. For example, a staff member used Facebook and Twitter to share information and send weekly “tweets” educating Deaf individuals on a variety of health topics, including obesity awareness and healthy eating.35,36 The “shared” information and “tweets” engaged Deaf individuals to learn more about their health and ability to join in a randomized weight loss study designed for Deaf individuals.

Table 2.

Strategies Used to Address Challenges With Deaf Health Research

| Challenges | Strategy Used by NCDHR and DHCC |

|---|---|

| Use of auditory-based recruitment Methods and non-American sign Language fluent researchers | Use of ASL video-based blogs (“vlogs”) |

| Use of sign language (ASL) fluent researcher and staff | |

| Use of ASL during presentations and recruitment events | |

| Engagement of Deaf gatekeepers and organizations | |

| Communication and language barriers and social marginalization | Hiring and inclusion of Deaf and ASL fluent researchers and staff |

| Provision of ASL classes for non-ASL fluent staff and researchers | |

| Use of ASL-based instrument and tools | |

| Availability of staff interpreter to facilitate communication between Deaf and non-signing hearing individuals | |

| Diversity within the Deaf community | Use of varied signing models (racial, gender, and types of sign language options) included with instruments and tools |

| Outreach to varied Deaf organizations and individuals, including Deaf minority group based organizations (racial, ethnic, and sexual orientation) | |

| Negative views and mistrust with health care and research workers | Hiring of Deaf community members for TWG, chair position for DHCC |

| Provision of Deaf health talks by sign language fluent health providers (free monthly health educational program in sign language) | |

| Increased diversity of health researchers and staff for NCDHR | |

| Partnerships with Deaf-friendly health care providers in the community | |

| Length of time to develop community relationships and networks | Gatekeepers were enlisted early and regularly |

| Assigning staff and research time for meetings and events | |

| Use of VP calls | |

| Low socioeconomic status | Use of easy to visualize and read recruitment and dissemination materials |

| Poor educational achievement | Use of ASL based “vlogs” and community presentations |

| Poverty Transportation issues | Financial reimbursements for community members' efforts on research related work- cognitive interviews, TWG, DHCC Chair |

| Financial incentives for participation with select research projects | |

| Data collection and survey administration at Deaf events and organizations | |

| Provision of parking vouchers at research center | |

Engaging Deaf individuals in research was also critical for NCDHR to ensure effective survey adaptation and translation. The English-based BRFSS, designed for telephone use, required extensive translation and adaptation through the Translational Work Group (TWG) to develop the DHS. Deaf ASL users, familiar with translation work, formed a core group of the TWG. A common translation challenge was trying to seek meaning equivalence with the English survey question material, not “word-for-word parallelism.”33 One of the BRFSS questions asked the participant if they undergone either a “colonoscopy” or a “sigmoidoscopy.” Because ASL lacks specific signs that mean “colonoscopy” or “sigmoidoscopy,” the TWG focused on the concept involving insertion of a scope into the rectum, but did not differentiate in their sign selection.33 This avoided finger spelling the procedure’s name, which could jeopardize the cognitive recognition of the medical terminology.

Health Research Should Benefit the Community, Not Threaten It

Medical researchers involved with deafness-related research frequently focus on eliminating deafness through the use of medical technologies and genetic engineering, despite the increasing recognition of the importance of cultural and genetic diversity12 and the apprehension of Deaf individuals who fear genetic engineering and cochlear implantation techniques will diminish deafness.37,38

The cultural and community threat is not a new experience. Deaf individuals have historically experienced negative effects from the medical community’s efforts to correct deafness, particularly the practice of eugenics and sterilization of Deaf individuals in the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth centuries (e.g., Nazi Germany). Even today, there are government bills in Europe and Australia that interpret deafness as a defective condition, amenable to genetic screening, elimination, or correction.37

To address this distrust, the NCDHR worked closely with the DHCC to reassure and demonstrate to the Deaf community that the research focus was on the acquisition of scientific knowledge to improve Deaf people’s health, not on the elimination of deafness. The hiring of Deaf researchers and staff, and cross-cultural education of the hearing research team also helped to alleviate some of the mistrust. The close-knit Deaf community relies on a strong network of peer information exchange to learn about a variety of topics. One Deaf individual obtaining inaccurate information about a research project can negatively affect the community’s perspective on the project.39 The use of Facebook, Twitter, ASL films on research processes,40–43 and persistent community involvement by NCDHR helped to establish a sense of “connectedness” with the Deaf community and helped to increase trust and transparency with NCDHR.

CBPR allows the Deaf community to voice their desires and concerns in a nonthreatening research environment, while selecting the research agenda. To provide a safe and accessible research environment, Deaf community members were hired to teach ASL to the non-fluent hearing researchers and staff members. Each week, these hearing individuals met one-on-one with a Deaf ASL teacher to learn ASL and about the Deaf culture. The use of ASL interpreters also provided greater communication access between signers and non-signers.

Enlist Community Gatekeepers and Peer-Based Recruitment Strategies

Recruitment with challenging-to-reach populations, including the Deaf community, requires substantial effort and resources. Deaf individuals often are socially marginalized owing to language and communication barriers, poverty, and low educational achievement.24,44 Traditional recruitment efforts often fail to engage the Deaf community, partly owing to many researchers’ reliance on non-culturally or -linguistically appropriate recruitment strategies (e.g., random digit dialing or radio advertisements).

To overcome recruitment barriers, the NCDHR research team worked diligently to develop strong relationships with a variety of Deaf community and service organizations. Gatekeepers were recognized as key recruiters because they generate an element of trust for many community members and provide valuable insight on the feasibility and relevancy of a research project.

Recruitment with challenging-to-reach populations can be a trial and error process. In the early phases of the DHS recruitment, strategies focused on providing information on the DHS to the partnering organizations, open house presentations at the research center, and the use of web, email, and video blog-based flyers. Community members who were enthusiastic advocates of the mission and goals of the research project became the most effective recruiters in the community.

Many recruited individuals were well known by many of the research members, resulting in convenience sampling biases. Recruitment strategies needed to be improvised to achieve a more representative sample, even though DHS recruitment goals were attained. To avoid sampling biases with many challenging-to-reach populations, respondent-driven sampling may be the ideal approach to recruiting a representative sample.45 To achieve representative samples, current research recruitment efforts at NCDHR now plan or use respondent-driven sampling methods.

Sustainability and Long-Term Commitment to the Community

Maintaining and building relationships with partners and community leaders requires significant commitments of time and resources on behalf of the research team. Research staff and faculty members should be enthusiastic participants in community and organizational events. The NCDHR research team maintained high visibility at community events, helping to understand the community’s health needs and members’ perspectives toward research and health care. This facilitated greater trust, visibility, and rapport with other community members to be able to share opinions, ideas, and even concerns with the NCDHR.

Research capacity in underserved and underrepresented community projects can be difficult to sustain without the involvement of community members in project leadership and development roles. Many linguistic minorities and hard-to-reach communities are poorly represented among research teams, especially at the research faculty level.46 Educational pipelines are becoming an important way to increase interested and diverse applicants into health research careers.

Few, if any, such pipelines previously existed for Deaf students in the healthcare or research field. Each summer, several Deaf and hard-of-hearing students are given the opportunity to develop their research skills and gain knowledge in community health through the NCDHR internship program. In addition, an NIH-supported fellowship program at the UR offers opportunities for Deaf post-doctoral candidates to engage in community health research related to cardiovascular disease. Two current Deaf junior faculty members were trained through this pathway. To increase interest on a national level, the NCDHR collaborates with partnering organizations in a Task Force for Health Care Careers for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Community to provide ideas on how to increase diversity in the health care workforce.

Sustainability, in light of funding and budget restraints at the federal and state levels, has been threatened for a number of community health projects. The NCDHR has tried to increase sustainability by diversifying research grants. During the first grant cycle, the NCDHR received funds solely from the CDC. Currently, the NCDHR is a center in which resources are being shared through multiple research projects (Table 3). Diversity in funding helps to not only expand community partnerships, but also better serve the community’s needs and priorities.

Table 3.

NCDHR-Related Research Projects

| Grant Number, Sponsor, PI | Project Title | Years |

|---|---|---|

| 5U48DP001910: Prevention Research Center, CDC, T.A. Pearson | Rochester Prevention Research Center: National Center for Deaf Health Research | 2009–2014 |

| 5U48DP000031: Prevention Research Center, CDC, T.A. Pearson | Rochester Prevention Research Center: National Center for Deaf Health Research | 2004–2009 |

| 5R01CE001871-02: Research Grants for Preventing Violence and Violence-Related Injury (R01), CDC, R. Pollard | Factors Influencing Partner Violence Perpetration Affecting Deaf People | 2010–2013 |

| 5K08HS015700-05, Mentored Clinical Scientist Development Award (K08), AHRQ, S. Barnett | Deaf People and Healthcare | 2006–2011 |

| 5K01HL103140-02: Mentored Career Development Award to Promote Faculty Diversity/Re-Entry in Biomedical Research (K01), NIH, M. McKee | Health Literacy Among Deaf ASL Users and Cardiovascular Health Risk | 2010–2015 |

| 5K01HL10012-02: Mentored Career Development Award to Promote Faculty Diversity/Re-Entry in Biomedical Research (K01), NIH, S. Smith | Assessing Cardiovascular Risks in Deaf Adolescents who use Sign Language | 2010–2015 |

| 5U48DP000031, Prevention Research Centers Program (PRC) Special Interest Project (SIP 9-05), “The Cardiovascular Health Intervention Research and Translation Network,” CDC, T.A. Pearson | Perceptions of CVD Risk and CVD Health Promotion in Deaf Communities | 2008–2009 |

| Minority Health Fellowship from The Association of Schools of Public Health (ASPH) in cooperation with the CDC Prevention Research Centers program, CDC/ASPH, T. David | Comparing the use of a written health surveillance survey among Deaf and hearing college freshmen | 2007–2009 |

Conclusion

CBPR efforts in the Rochester Deaf Community provide many lessons for conducting culturally appropriate research for challenging-to-reach populations. CBPR permits greater collaboration between the research community and the community of interest, providing strategies to engage and recruit more effectively, yielding more representative data and effective interventions. This approach requires significant effort, patience, and resources for both the research team and the community. Fundamental to the successful building of enduring relationships with vulnerable and understudied communities are the recognition and respect of cultural norms and the use the community’s preferred language. Community health researchers must be mindful of the importance of maintaining cultural competency and cultural humility in their work. Research centers and funding agencies are recognizing and should continue to acknowledge the importance of sustainability in CBPR.

Efforts to develop culturally and linguistically accessible research materials and training programs for underrepresented community researchers and members are much needed. This would permit better community engagement to address its needs, while ensuring the scientific rigors demanded by academic research. Creation of strong partnerships between the community and the research team requires mutual respect, trust, openness, and equality in all phases of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the CDC or the NIH. The authors acknowledge the members of the NCDHR and the Deaf Health Community Committee for their input. The authors also thank the Deaf community for its ongoing research partnership and participation.

The NCDHR was supported by Cooperative Agreements U48 DP000031 and U48 DP001910 from the CDC (Pearson, PI). This publication was made possible by Grant K01 HL103140-01 (McKee, PI) and Grant T32 HL007937 (Pearson, PI) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the NIH.

Key to Commonly Used Abbreviations

- CBPR

Community-based participatory research

- ASL

American Sign Language

- NCDHR

National Center for Deaf Health Research

- DHCC

DeafHealth Community Committee

- DHS

DeafHealth Survey

- BRFSS

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- TWG

Translational Work Group

- UR

University of Rochester

REFERENCES

- 1.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Review of community-based participatory research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israel B, Krieger J, Vlahov D, Ciske S, Foley M, Fortin P, et al. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle urban research centers. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoecker R. Are academics irrelevant? Roles for scholars in participatory research. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42:840–854. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lantz P, Viruell-Fuentes E, Israel B, Softley D, Guzman R. Can communities and academia work together on public health research? Evaluation results from a community-based participatory research partnership in Detroit. J Urban Health. 2001;78:495–507. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minkler M, Blackwell A, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1210–1213. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strickland CJ. Challenges in community-based participatory research implementation: Experiences in cancer prevention with Pacific Northwest American Indian tribes. Cancer Control. 2006;13(3):230–236. doi: 10.1177/107327480601300312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieger J, Allen C, Cheadle A, Ciske S, Schier J, Senturia K, et al. Using community-based participatory research to address social determinants of health: Lessons Learned from Seattle partners for healthy communities. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(3):361–382. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen TT, McPhee S, Bui-Tong N, Luong TN, Ha-Iaconis T, et al. Community-based participatory research increases cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese-Americans. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(Suppl 2):31–54. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ammerman A, Washington C, Jackson B, Weathers B, Campbell M, Davis G, et al. The Praise! Project: A church-based nutrition intervention designed for cultural appropriateness, sustainability, and diffusion. Health Promot Pract. 2002;3:286–301. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preston P. Mother father deaf: the heritage of difference. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(11):1461–1467. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00357-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Padden C, Humphries T. Inside deaf culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauser P, O’ Hearn A, McKee M, Steider A, Thew D. Deaf epistemology: Deafhood and deafness. Am Ann Deaf. 2010;154(5):486–492. doi: 10.1353/aad.0.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrington T, editor. American sign language: Ranking and number of “speakers”. Washington (DC): Gallaudet University Library; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell R, Young T, Bachleda B, Karchmer M. How many people use ASL in the United States? Why estimates needed updating. Sign Language Studies. 2006;6:306–335. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnett S, McKee M, Smith S, Pearson T. Deaf sign language users, health inequities, and public health: Opportunity for social justice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(2) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnett S, Franks P. Telephone ownership and deaf people: implications for telephone surveys. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1754–1756. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.11.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett S. Clinical and cultural issues in caring for deaf people. Fam Med. 1999;31(1):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zazove P, Niemann L, Gorenflo D, Carmack C, Mehr D, Coyne J, et al. Health status and health care utilization of the deaf and hard-of-hearing persons. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2(7):745–752. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.7.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamaskar P, Malia T, Stern C, Gorenflo D, Meador H, Zazove P. Preventive attitudes and beliefs of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(6):518–525. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.6.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKee M, Barnett S, Block R, Pearson T. Impact of communication on preventive services among deaf American sign language users. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(1):75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinberg A, Barnett S, Meador H, Wiggins E, Zazove P. Health care system accessibility. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(3):260–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKee M, Schlehofer D, Cuculick J, Starr M, Smith S, Chin N. Perceptions of cardiovascular health in an underserved community of deaf adults using American Sign Language. Disabil Health J. 2011;4(3):192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanchfield BB, Feldman JJ, Dunbar JL, Gardner EN. The severely to profoundly hearing-impaired population in the United States: Prevalence estimates and demographics. J Am Acad Audiol. 2001;12(4):183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnett S, Klein J, Pollard R, Jr, Samar V, Schlehofer D, Starr M, et al. Community participatory research with deaf Sign language users to identify health inequities. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):2235–2237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Margellos-Anast H, Estarziau M, Kaufman G. Cardiovascular disease knowledge among culturally Deaf patients in Chicago. Prev Med. 2006;42(3):235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wollin J, Elder R. Mammograms and Pap smears for Australian deaf women. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26(5):405–409. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zazove P. Cancer prevention knowledge of people with profound hearing loss. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):320–326. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0895-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodroffe T, Gorenflo DW, Meador HE, Zazove P. Knowledge and attitudes about AIDS among deaf and hard of hearing persons. AIDS Care. 1998;10(3):377–386. doi: 10.1080/09540129850124154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peinkofer JR. HIV education for the deaf, a vulnerable minority. Public Health Rep. 1994;109(3):390–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heuttel KL, Rothstein WG. HIV/AIDS knowledge and information sources among deaf and hearing college students. Am Ann Deaf. 2001;146(3):280–286. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finger Lakes Health Systems Agency. Deaf Health Task Force report. [updated 2004] Available from: http://www.flhsa.org/Deaf.pdf.

- 33.Graybill P, Aggas J, Dean R, Demers S, Finnigan E, Pollard R. A community-participatory approach to adapting survey items for deaf individuals and American Sign Language. Field Methods. 2010;22(4):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ethical principles in research program review in ASL. Rochester (NY): Deaf Health Community Committee; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Center for Deaf Health Research. Twitter: DeafHealth at NCDHR @DeafHealthNCDHR. [updated 2011; cited 2011 Dec 20] Available from: http://twitter.com/DeafHealthNCDHR.

- 36.National Center for Deaf Health Research. National Center for Deaf Health research on Facebook. [updated 2011; cited 2011 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.facebook.com/pages/National-Center-for-Deaf-Health-Research/204749949096.

- 37.Emery S, Middleton A, Turner G. Whose Deaf genes are they anyway? The Deaf Community’s challenge to legislation on embryo selection. Sign Language Studies. 2010;10(2):155–169. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnos K. Genetics and deafness: Impacts on the Deaf Community. Sign Language Studies. 2002;2(2):150–168. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meador H, Zazove P. Health care interactions with Deaf culture. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(3):218–222. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.NCDHR. Introduction to Research Concepts from NCDHR. [updated 2011; cited 2011 Dec 23]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z4eL9ogxVnk&list=UURzgNzCJbY182we_CH434Pg&index=7&feature=plcp.

- 41.NCDHR. What is informed consent? [updated 2011; cited 2011 Dec 23]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iBjdSLybG9c&feature=related.

- 42.NCDHR. What is a randomized controlled trial? [updated 2011; cited 2011 Dec 23]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z4eL9ogxVnk&list=UURzgNzCJbY182we_CH434Pg&index=7&feature=plcp.

- 43.Barnett S, McKee M, Smith S, Pearson T. Appendix. Examining Deaf population health inequities from a social justice perspective (Video) for the Deaf sign language users, health inequities, and public health: Opportunity for social justice article. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(2) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McEwen E, Anton-Culver H. The medical communication of deaf patients. J Fam Pract. 1988;26(3):289–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heckathorn D. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;2:174–199. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merchant J, Omary M. Underrepresentation of underrepresented minorities in academic medicine: The need to enhance the pipeline and the pipe. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(1):19–26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]