Abstract

We explored whether changes in the expression profile of peripheral blood plasma proteins may provide a clinical, readily accessible “window” into the brain, reflecting molecular alterations following traumatic brain injury (TBI) that might contribute to TBI complications. We recruited fourteen TBI and ten control civilian participants for the study, and also analyzed banked plasma specimens from 20 veterans with TBI and 20 control cases. Using antibody arrays and ELISA assays, we explored differentially-regulated protein species in the plasma of TBI compared to healthy controls from the two independent cohorts. We found three protein biomarker species, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3, and epidermal growth factor receptor, that are differentially regulated in plasma specimens of the TBI cases. A three-biomarker panel using all three proteins provides the best potential criterion for separating TBI and control cases. Plasma MCP-1 contents are correlated with the severity of TBI and the index of compromised axonal fiber integrity in the frontal cortex. Based on these findings, we evaluated postmortem brain specimens from 7 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and 7 neurologically normal cases. We found elevated MCP-1 expression in the frontal cortex of MCI cases that are at high risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. Our findings suggest that additional application of the three-biomarker panel to current diagnostic criteria may lead to improved TBI detection and more sensitive outcome measures for clinical trials. Induction of MCP-1 in response to TBI might be a potential predisposing factor that may increase the risk for development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, biomarker, long-term clinical TBI phenotypes, mild cognitive impairment, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, plasma, traumatic brain injury

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of death and disability in the United States [1]. Somatic and neuropsychiatric complaints, including headache, dizziness, sleep disturbances, hyperarousal, mood disturbances, tinnitus, photosensitivity, oculomotor dysfunction, and pain, are common following TBI. Neurocognitive impairment including impaired memory, attention, concentration, and executive function are observed in individuals with TBI at all levels of severity [2, 3]. While the primary mechanisms of injury are bleeding and diffuse axonal injury [4-6], the pathophysiology of TBI is complex and not well understood.

TBI in the civilian population is typically associated with direct, closed impact mechanical trauma to the brain due to falls, motor vehicle accidents, assault, and sports-related injuries [7]. Among military personnel, particularly among veterans returning from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, TBI commonly results from exposure to blast pressure waves stemming from explosive devices, leading to symptom profiles similar to those seen in civilians [7-9]. In both military and civilian populations, these symptoms can have a minimal to profound impact on their daily functioning.

Several studies suggest that exposure to moderate-severe TBI is a risk factor for subsequent development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [10-13], although the association between mild TBI and risk for AD is not yet well established. Neuropathological mechanisms that underlie AD may also be present after TBI, and these mechanisms may contribute to lasting and/or worsening neurological dysfunction. Evidence from human [14-16] and animal models [17] reveals abnormal accumulation of AD pathological hallmarks (e.g., amyloid-β peptides and tau proteins) in the brain and in cerebrospinal fluid following TBI. Moreover, elevation of plasma tau levels has been associated with worse TBI outcomes [18]. Thus, neurological dysfunction in TBI and in AD may share common neuropathological/neurodegenerative mechanisms.

Accumulating evidence has highlighted the association of TBI with defects in neural circuits and synapses, and the plasticity processes controlling these functions [19-24]. While genes relevant to these processes are expressed in the brain, some of these genes are also expressed in peripheral blood [25-28]. Thus, peripheral blood biomarkers may provide insights into the pathogenesis of neurological disorders and be used to monitor disease diagnosis and progression [29-31]. The brain controls many body functions via the release of signaling proteins, and both central and peripheral immune and inflammatory mechanisms are implicated in post TBI impairments [32-36]. Using high throughput antibody arrays and quantitative ELISA assays in the analysis of a civilian and a veteran TBI study cohort, we explored the feasibility of characterizing surrogate biological indices (biomarkers) from circulating blood plasma that are associated with specific impairments secondary to TBI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject recruitment and assessments

Civilian TBI and control subjects

Fourteen TBI and ten age-, gender-, and education-matched healthy control civilian participants were recruited from the Brain Injury Research Center at Mount Sinai (BIRC-MS). TBI participants sustained a blow to the head followed by loss of consciousness or a period of being dazed and confused. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the Institutional Review Board policies and procedures of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine (MSSM). Demographic information about the TBI and control participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the civilian TBI study cohort. All TBI participants sustained a blow to the head followed by loss of consciousness or a period of being dazed and confused. Age-, gender-, and educationmatched healthy civilians served as controls. Time post injury is the time frame between the occurrence of brain injury and volunteer’s participation in this biomarker study. TBI group was characterized by a mean post injury interval of 13.2±12.6 years. There were no significant differences between TBI and control group in terms of age (p = 0.894), years of education (p = 0.831), or gender distribution (p = 1.0). Ethnicity compositions of TBI and control groups were comparable

| Control | TBI | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 10* | 14* |

| Gender | 50% F | 50% F |

| TBI severity | ||

| Mean±SD | 1±0 | 4.7±1.9 |

| Range | 1 | 2 – 7 |

| Age (mean yrs±SD) at study participation |

40.1±11.5 | 40.8±12.8 |

| Post injury interval (mean yrs±SD) |

– | 13.2±12.6 |

| Education (mean yrs±SD) | 15.6±1.6 | 15.9±3.4 |

| Ethnicity composition | ||

| White-Caucasian | 60% | 64% |

| Black-African American | 10% | 22% |

| Hispanic | 20% | 14% |

| Asian | 10% | – |

The first 8 control and 12 TBI cases recruited were used in initial antibody array studies. Follow-up ELISA assessments of MCP-1 contents were conducted using all 10 Control and 14 TBI cases.

Abbreviations: TBI, traumatic brain injury; yrs, years; F, female.

All participants completed the Brain Injury Screening Questionnaire (BISQ) [37, 38] to comprehensively assess TBI history, i.e., the number and severity of impacts to the head sustained throughout their lifespan. Injury severity of the civilian TBI participants ranged from mild to severe, as classified using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (no loss of consciousness, no confusion; i.e., no TBI) to 7 (loss of consciousness greater than 4 weeks in duration) [39]. The BISQ also solicits participants’ self-report of functional difficulties and symptoms associated with brain injury. In addition, blood plasma was collected and banked for subsequent biomarker studies.

Veteran TBI and control subjects

Banked plasma specimens from 20 male Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with TBI and 20 male control cases were generously provided by the VA Northwest Network Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) at Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) and the University of Washington Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (UWADRC) in Seattle, WA. All Veteran participants recruited from the VAPSHCS had documented hazardous duty experience in Iraq and/or Afghanistan during Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom, and all had reported experiencing at least one blast exposure in the war zone that resulted in mild TBI, as defined by American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine criteria [39]. Control specimens were banked from age- and gender-matched cognitively-normal cases: nine cognitively-normal Iraq-deployed veterans plus eleven community volunteers recruited from the UWADRC, all of whom were medically healthy and had Mini-Mental State Examination scores of 29.4 ± 1.0 (mean ± standard deviation [range 27-30]), Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [40] scores of zero, no evidence or history of cognitive or functional decline (assessed with the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set), and no history of blast exposure or impact head injury. Demographic information about the veteran TBI and control participants is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the veteran TBI study cohort. TBI cases were comprised of male veterans with documented hazardous duty experience in Iraq and/or Afghanistan during Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom, and all had reported experiencing at least one blast exposure in thewar zone that resulted in mild TBI, as defined by American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine criteria [39]. Age- and gender-matched healthy, cognitively normal male control cases were comprised of Iraq-deployedVeterans (n=9) and community volunteers from the UWADRC (n = 11). The TBI group was characterized by a mean post injury interval of 3.9±1.4 years. There were no significant differences between TBI and control group in terms of age (p = 0.959). As a group, the control subjects spent more time in education (p = 0.003). Ethnicity compositions of TBI and control groups were comparable

| Control | TBI | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 20 | 20 |

| gender | 100% M | 100% M |

| Age (mean yrs±SD) at study participation |

29.7±6.3 | 29.8±5.9 |

| Post injury interval (mean yrs±SD) |

– | 3.9±1.4 |

| Education (mean yrs±SD) | 16.4±3.3 | 13.8±1.5 |

| Ethnicity composition | ||

| White | 80% | 70% |

| Black | 5% | 5% |

| White-Hispanic | 5% | 10% |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander |

– | 5% |

| Other or NA | 10% | 10% |

Abbreviations: TBI, traumatic brain injury; M, male.

Plasma collection and antibody array

Freshly collected and banked plasma specimens were stored at −80°C. Antibody array studies were conducted using plasma specimens from the 20 cases (8 Control and 12 TBI cases) we recruited. We subsequently recruited an additional 2 control and 2 TBI cases for a total for a total of 24 (10 control and 14 TBI cases). All 24 cases were used in follow-up ELISA assessments of plasma MCP-1 contents.

Antibody array studies using the RayBio Cytokine Antibody Array 200 (Raybiotech Inc.) were conducted to measure relative levels of 120 known signaling proteins in plasma specimens [41]. Specific proteins assessed are presented in Table 3. Antibody array studies were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions [42]. For each plasma sample, nitrocellulose membranes containing antibodies for each of the 120 proteins in duplicate spots were blocked, incubated with plasma, washed, and then incubated with a cocktail of biotin-conjugated antibodies specific for the different proteins. Membranes were developed with streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase and ECL chemiluminescense reagents and exposed to autoradiographic film (BioMax Lite, Kodak). Autoradiographic films were scanned and digitized spots were quantified with Imagene 6.0 data extraction software (BioDiscovery Inc.). Local background intensities were subtracted from each spot, and the average of the duplicate spots for each protein was normalized to the average of six positive controls on each membrane. Expression data from the two filters per sample were normalized to the median expression of all 120 proteins followed by Z score transformation. Adjusted student t tests were used to test the significance of the protein expression differences between TBI and control cases using SPSS software. p < 0.05 was the cut off to choose proteins for further studies.

Table 3.

A listing of the 120 proteins assessed using the antibody array. The proteins are listed by alphabetic order based on protein name

| 1 | Adiponectin | 31 | CCL26/Eotaxin-3 | 61 | ICAM-3 | 91 | Leptin |

| 2 | AGRP | 32 | CCL27/CTACK | 62 | IFN-_ | 92 | LIGHT |

| 3 | Amphiregulin | 33 | CNTF | 63 | IGF1-R | 93 | M-CSF |

| 4 | ANG-2 | 34 | CX3CL1/Fractalkine | 64 | IGFBP-1 | 94 | MIF |

| 5 | Angiogenin | 35 | CXCL1,2,3/GRO-_ | 65 | IGFBP-2 | 95 | MSP_-chain |

| 6 | AXL | 36 | CXCL1,2,3/GRO-_ | 66 | IGFBP-3 | 96 | NGF-_ |

| 7 | basic FGF | 37 | CXCL1,2,3/GRO-_ | 67 | IGFBP-4 | 97 | NT-3 |

| 8 | BDNF | 38 | CXCL5/ENA-78 | 68 | IGFBP-6 | 98 | NT-4/5 |

| 9 | BMP-4 | 39 | CXCL6/GCP-2 | 69 | IGF-I | 99 | Oncostatin M |

| 10 | BMP-6 | 40 | CXCL7/NAP-2 | 70 | IL-1 R-like 1 | 100 | Osteoprotegerin |

| 11 | BTC | 41 | CXCL8/IL-8 | 71 | IL-1 sRI | 101 | PDGF-BB |

| 12 | CCL1/I-309 | 42 | CXCL9/MIG | 72 | IL-1ra | 102 | PLGF |

| 13 | CCL2/MCP-1 | 43 | CXCL11/I-TAC | 73 | IL-1_ | 103 | SCF |

| 14 | CCL3/MIP-1_ | 44 | CXCL12/SDF-1 | 74 | IL-1_ | 104 | Sgp130 |

| 15 | CCL4/MIP-1_ | 45 | CXCL13 | 75 | IL-2 | 105 | TGF-J |

| 16 | CCL5/RANTES | 46 | EGF | 76 | IL-2 sRa | 106 | TGF-_3 |

| 17 | CCL7/MCP-3 | 47 | EGFR | 77 | IL-3 | 107 | TIMP-1 |

| 18 | CCL8/MCP-2 | 48 | Fas | 78 | IL-4 | 108 | TIMP-2 |

| 19 | CCL11/Eotaxin | 49 | FGF-4 | 79 | IL-5 | 109 | TNFR-1 |

| 20 | CCL13/MCP-4 | 50 | FGF-6 | 80 | IL-6 | 110 | TNFR-2 |

| 21 | CCL15/MIP-1d | 51 | FGF-7 | 81 | IL-6 sR | 111 | TNF-_ |

| 22 | CCL16/HCC-4 | 52 | FGF-9 | 82 | IL-7 | 112 | TNF-_ |

| 23 | CCL17/TARC | 53 | Fit-3L | 83 | IL-10 | 113 | TPO |

| 24 | CCL18 | 54 | G-CSF | 84 | IL-11 | 114 | TRAIL R3 |

| 25 | CCL19/MIP-3_ | 55 | GDNF | 85 | IL-12p40 | 115 | TRAIL R4 |

| 26 | CCL20/MIP-3_ | 56 | GITR | 86 | IL-12p70 | 116 | TYRO3 |

| 27 | CCL22/MDC | 57 | GITR-L | 87 | IL-13 | 117 | uPAR |

| 28 | CCL23/CKb8-1 | 58 | GM-CSF | 88 | IL-15 | 118 | VEGF-B |

| 29 | CCL24/Eotaxin-2 | 59 | HGF | 89 | IL-16 | 119 | VEGF-D |

| 30 | CCL25/TECK | 60 | ICAM-1 | 90 | IL-17 | 120 | XCL1/Lymphotactin |

ELISA assay

Plasma MCP-1 levels were measured using the Quantikine human CCL2/MCP-1 ELISA Kit (R&D Systems) following the manufacturer’s instructions. T-tests were used to determine group differences and correlations between MCP-1 contents and neuropsychological measures or brain imaging data (see below).

Brain imaging studies

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) was performed on the civilian study cohort only. Images were acquired on a Philips 3.0 T Achieva (Best, The Netherlands) scanner using a diffusion-weighted spin echo sequence (TR = 5682 ms, TE = 70, FOV = 21.0 cm, FA = 90°, 54 axial slices, thickness = 2.5, no skip, matrix size = 104 × 106, b-factor = 1200 s/mm2, 32 gradient directions plus b0, 2 averages). A high-resolution 3D T1-weighted structural image with good grey/white matter differentiation was acquired using a fast-field echo sequence for co-registration and normalization purposes (TR = 7.5 ms, TE = 3.4 ms, FOV = 22.0 cm, FA = 8°, 172 sagittal slices, thickness = 1 mm, no skip, Matrix size = 220 × 204 × 172).

Diffusion tensor images were eddy-current-corrected. Fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity maps were calculated using the FSL comprehensive library of analysis tools for brain imaging data (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). Whole brain group comparisons of the diffusion parameters were performed. First, FA images were spatially normalized to the International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) brain template using tract based spatial statistics [43]. The parameters used to warp the FA images to ICBM template and the white matter skeleton were applied to the diffusivity map images, followed by statistical comparisons using the FSL Randomize rou-ine to test for group differences in FA and diffusivity maps (separately). Clusters were identified using Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement [44]. FA values of the whole brain and several individual tracts were extracted for further statistical analysis using Statistica V9 (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, OK). Correlations between FA and plasma MCP-1 contents were computed.

Brain specimens

Banked postmortem frontal cortex (BM9) brain specimens from 7 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) cases (characterized by CDR 0.5) and 7 neurologically-normal cases (characterized by CDR 0) were obtained from the MSSM Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Bank. CDR assignment was based on cognitive and functional assessments collected during the last 6 months of life [40, 45].

There were no significant differences between MCI and neurologically-normal control cases with respect to the age of death (mean age of death for the MCI and the control groups was 85.4 ± 2.1 years and 85.9 ± 2.1 years, respectively; p = 0.648) or the postmortem interval (mean age of death for the MCI and the control groups was 7.5 ± 5.1 h and 4.5 ± 1.2 h, respectively; p = 0.156). A slightly higher proportion (86%) of the MCI cases was female compared to control cases (57% females), but the difference is not significant (p = 1.0).

Assessment of MCP-1 mRNA in postmortem brain specimens

Total RNA was isolated from approximately 50 mg of postmortem brain specimens using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. First strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using Superscript III Supermix for qRT-PCR (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using Maxima SYBR Green master mix (Fermentas) in ABI Prism 7900HT in 4 replicates. Human TATA-binding protein (TBP) expression level was used as an internal control. Data were normalized using the 2−ΔΔCt method [46]. T-tests were used to determine group differences.

RESULTS

Identification of plasma TBI biomarkers in a civilian TBI study cohort

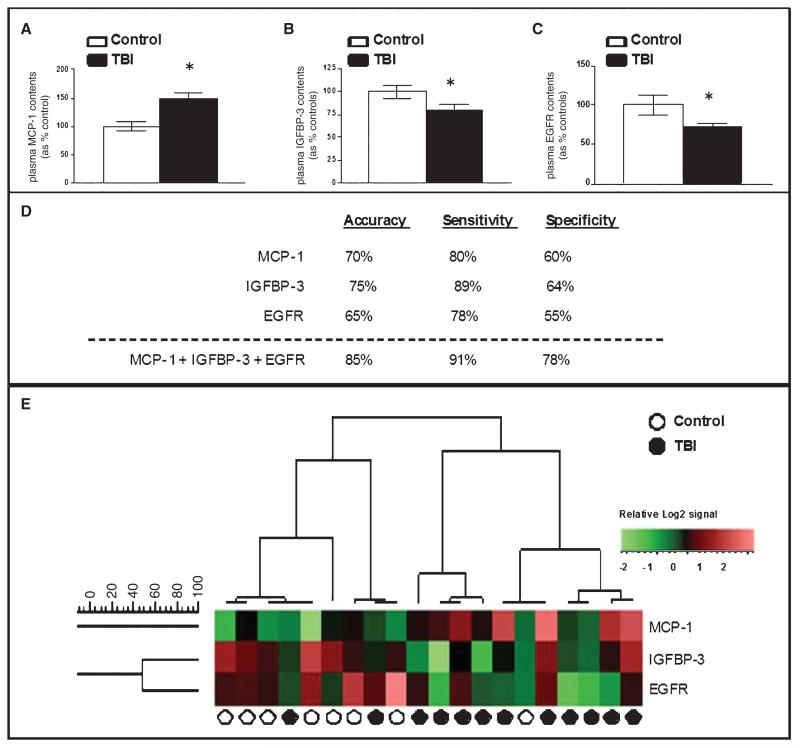

Plasma protein expression profile analysis, performed using the RayBio Cytokine antibody array platform in a subset of twelve TBI and eight healthy control participants from the civilian study cohort (Table 1), led to the identification of three candidate TBI biomarkers. In particular, TBI cases in the civilian study cohort were characterized by elevated plasma MCP-1 contents (Fig. 1A) and reduced plasma insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) (Fig. 1B) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Fig. 1C) contents, relative to controls.

Fig. 1.

Candidate plasma biomarker contents provide a sensitive and specific criterion for distinguishing TBI from control cases. Relative expression of 120 known signaling proteins in plasma specimens from a subset of 12 TBI and 8 control cases from the civilian study cohort (Table 1) were assessed by antibody array platforms (RayBio Cytokine Antibody Array 2000; Raybiotech Inc.). The student t-test was used to test the significance of the protein expression differences between TBI and control cases. (A–C) Outcomes of the antibody array study led to the identification of three candidate TBI biomarkers: MCP-1, IGFBP-3, and EGFR. Bar graphs represent mean ± SD of plasma biomarker contents for MCP-1 (A), IGFBP-3 (B), and EGFR (C) among TBI and control cases. *2-tailed student t-test, p < 0.05, TBI compared to the control group. (D, E) Relative plasma biomarker contents assessed by antibody arrays were tested by unsupervised clustering analysis using the UPGMA algorithm with cosine correlation as the similarity metric. (D) Summary table of analysis results using individual MCP-1, IGFBP-3, and EGFR or using a combination of all three-protein species (the “three-protein” model). Accuracy represents the percentage of all 20 TBI and normal healthy controls in the antibody array profile analysis study that were correctly diagnosed by the test, calculated as the number of correctly identified TBI and normal healthy controls divided by the total number of patients in this study. Sensitivity (true positive [TP]/[TP + false negative (FN)]) is the probability that a patient who was predicted to have TBI actually has it, whereas the specificity (true negative [TN]/[false positive (FP) + TN]) measures the probability that a patient predicted not to have TBI will, in fact, not have it. (E) A heat map graphically depicting the efficacy of using a three biomarker panel to distinguish TBI and control cases by unsupervised clustering analysis.

We explored the sensitivity and specificity of individual biomarkers or a combination of the three candidate biomarkers in distinguishing TBI from healthy control cases. Using unsupervised clustering analyses in the assessment of plasma biomarker content data from the antibody array studies, we found that a three-biomarker panel including all three candidate biomarker proteins best segregates TBI and control cases with 85% accuracy, 91% sensitivity, and 78% specificity (Fig. 1D, E).

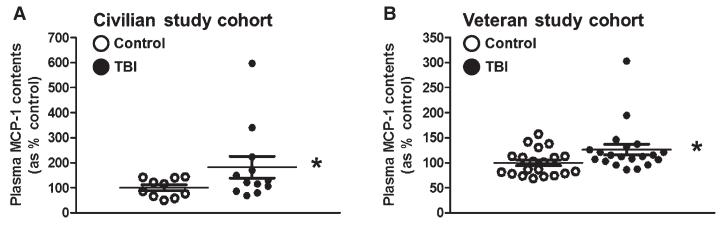

Validation of MCP-1 as a plasma TBI biomarker

Elevated expression of MCP-1 in the brain has been observed following TBI [47, 48]. It is possible that MCP-1 may have a role in the development of chronic post-TBI clinical complications. We therefore continued to explore the differential regulation of MCP-1 in plasma specimens from TBI cases. Using an independent ELISA we confirmed significantly elevated contents of MCP-1 in plasma of TBI compared to control cases from the civilian study cohort (p = 0.046) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Validation of plasma MCP-1 content as a clinically accessible TBI biomarker in two demographically distinct TBI study cohorts. An independent, quantitative ELISA assay was used to assess plasma MCP-1 contents in TBI and control cases from a civilian and a military veteran study cohort. (A) Plasma MCP-1 contents in TBI (n = 14) and control (n = 10) cases from the civilian study cohort (Table 1). (B) Plasma MCP-1 contents among veteran TBI (n = 20) and control (n = 20) cases (Table 2). Scatter graphs represent values for individual cases and group mean values ± SEM of plasma biomarker contents, expressed as % of controls. *p < 0.05 by student t-test, TBI compared to the control group.

Consistent with observations that mechanical- and blast-related TBI may share important pathophysiological features [7-9], our ELISA studies also demonstrated that blast-induced mild TBI cases in a Veteran population are also characterized by significantly higher plasma concentrations of MCP-1 (p = 0.041) (Fig. 2B).

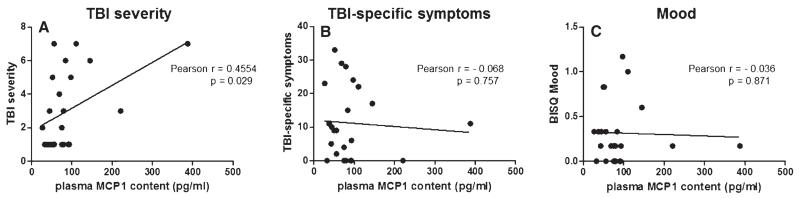

Association of plasma MCP-1 contents with TBI clinical symptoms

Based on the availability of self-reported clinical information for the civilian study cohort, we continued to explore potential associations between plasma MCP-1 contents and measures of TBI symptoms. We found that elevated plasma MCP-1 contents correlated significantly with severity of head injury (p = 0.029) (Fig. 3A). In contrast, we found no correlation between plasma MCP-1 contents and self-reported clinical symptoms as measured by the BISQ, including a subset of 25 cognitive symptoms that are sensitive and specific to TBI [38] (p = 0.757) (Fig. 3B) or mood (p = 0.871) (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Correlations of plasma MCP-1 content with self-reported indices of TBI complications. Correlation analyses were conducted using self-reported indices of TBI (assessed by BISQ [37, 38]) that were available for the civilian study cohort of 14 TBI and 10 control cases (Table 1). Correlations of plasma MCP-1 contents (pg/ml) with (A) TBI severity (p = 0.029), (B) a summation of 25 cognitive symptoms that are sensitive and specific to TBI [38] (p = 0.757), and (C) self-assessments of mood (p = 0.871).

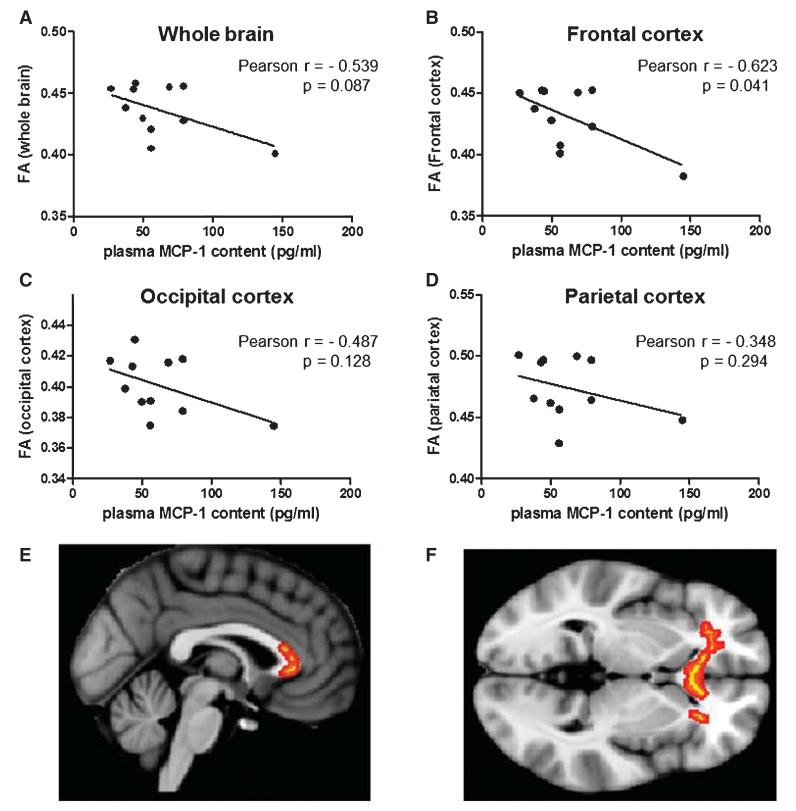

Association of plasma MCP-1 contents with index of compromised axonal fiber integrity

Evidence suggests that increased brain contents of MCP-1 might promote degradation of the basic myelin protein, which is a major constituent of the axonal myelin sheath in the nervous system [47, 48]. Thus, we explored whether elevated plasma MCP-1 contents following TBI might reflect changes in axonal integrity of the brain.

DTI is an ideal technique to study white matter integrity using the FA index, a measure of axonal integrity and coherence. Based on the availability of DTI information for female TBI and control cases from the civilian study cohort (Table 1), we examined the correlation between plasma MCP-1 contents and FA measurements in the brain. Among the subset of female civilian cases examined, we found a non-significant trend (p = 0.087) associating increased plasma MCP-1 concentration with reduced whole brain FA values (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Plasma MCP-1 contents are inversely correlated with brain FA measures. Correlational analyses were conducted using DTI information that was available for female (7 TBI and 5 control) cases from the civilian study cohort (Table 1). FA, a measure of white matter integrity [72], was calculated using the FSL comprehensive library of analysis tools for brain imaging data (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). Correlation of plasma MCP-1 contents (pg/ml) with whole brain FA (A), frontal cortex FA (B), occipital cortex FA (C), and parietal cortex FA (D). Representative sagittal (E) and transverse (F) sections of the brain illustrating significant correlations of FA with plasma MCP-1 contents (indicated by red-yellow) in frontal white matter and the genu of the corpus callosum.

Further analyses evaluated axonal integrity in individual brain regions. We found a significant inverse correlation (p = 0.021) between plasma MCP-1 concentration and frontal cortex FA values (p = 0.041) (Fig. 4B): higher concentrations of plasma MCP-1 are associated with decreased FA, indicating white matter damage in the frontal cortex. The inverse relationship between plasma MCP-1 and FA is primarily localized in frontal white matter and the genu of the corpus callosum (Fig. 4E, F). Outside of the frontal cortex, we observed no significant correlation between plasma MCP-1 concentrations and FA values in the occipital cortex (p = 0.128) (Fig. 4C) or parietal cortex (p = 0.294) (4D).

Elevated MCP-1 gene expression in the frontal cortex of cases characterized by MCI

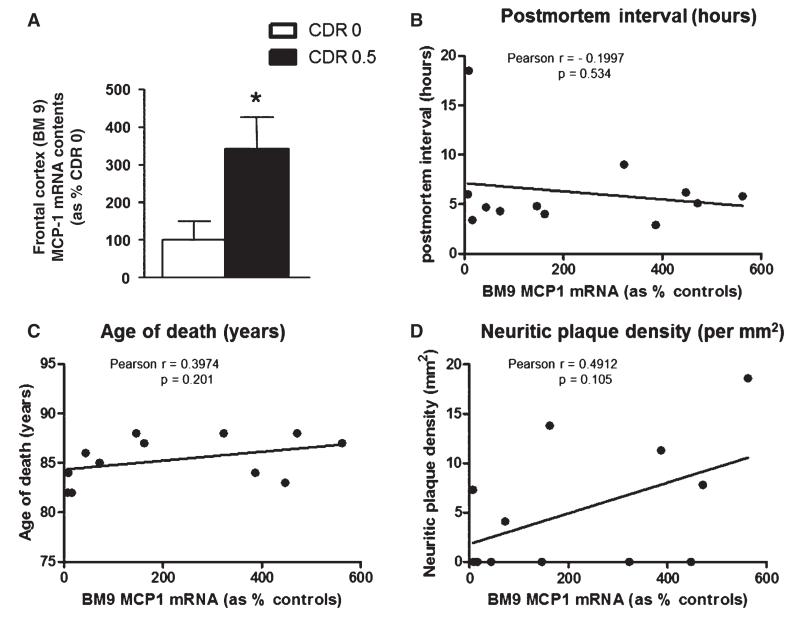

TBI may be a risk factor for AD, and elevated levels of MCP-1 have been observed in brains of AD patients [49, 50] and AD transgenic mice [12, 51]. Based on this and the role of MCP-1 in promoting inflammatory responses and myelin degradation, it is possible that overexpression of MCP-1 in the brain may contribute to the initiation and/or progression of AD. We explored the regulation of MCP-1 in the brain of MCI cases who, similar to TBI cases, may be at higher risk for AD dementia. We found significantly higher contents of MCP-1 mRNA in postmortem frontal cortex (BM9) specimens of MCI compared to control cases (Fig. 5A). In control cases, we found no correlation between MCP-1 mRNA content in frontal cortex tissues and postmortem interval (Fig. 5B), age at death (Fig. 5C) or neuritic plaque density (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Elevated MCP-1 mRNA in frontal cortex (BM9) brain specimens of cases characterized by mild cognitive impairment. (A) Contents of MCP-1 mRNA were assessed by qPCR and normalized to brain contents of human TATA-binding protein mRNA, used as an internal control. Bar graphs represent mean (± SEM) normalized MCP-1 mRNA contents in BM9 of CDR 0 cases (n = 6), expressed as % of MCP-1 mRNA contents in control cases (n = 6). *Student t-test, p < 0.05. B–D) Correlation analysis of BM9 MCP-1 mRNA contents with (B) postmortem interval, (C) age of death, and (D) neuritic plaque density (per mm2). There was no significant correlation between brain MCP-1 mRNA contents and postmortem interval (p = 0.534), age of death (p = 0.201), or neuritic plaque density (p = 0.105).

DISCUSSION

Evidence suggests that appropriate rehabilitative interventions can reduce functional impairment after TBI [52-54]. In order to demonstrate the efficacy of clinical interventions, research must identify the biological, clinical, and neurological indices that are sensitive to the detection of functional impairments after TBI [55]. We explored the feasibility of identifying plasma protein species that might be useful as clinically accessible surrogate biological indices of TBI. Our antibody array studies identified three candidate TBI protein biomarkers: MCP-1, present at higher levels, as well as IGFBP-3 and EGFR, present at lower levels, in plasma of chronic TBI cases. Moreover, we demonstrated that a three-biomarker panel using all three biomarkers provides a potential criterion for segregating TBI and control cases with 85% accuracy, 91% sensitivity, and 78% specificity. Our evidence tentatively implicates the value of this three-biomarker panel as a biological surrogate for improved TBI detection and more sensitive outcome measures for clinical trials.

Consistent with previous research, our findings suggest that MCP-1 plays a role in post-TBI clinical impairments. Elevated expression of MCP-1 in the brain has been observed following TBI [47, 48] and in response to neurodegenerative disorders [56-63]. Moreover, MCP-1 is known to promote inflammatory responses and processes leading to degradation of the axonal myelin sheath [64-67]. Using an independent ELISA assay, we confirmed elevated plasma MCP-1 concentrations in TBI cases from both civilian and veteran cohorts.

TBI cases in both the civilian and veteran study cohort were characterized by a long interval between injury and participation in the study (mean ± SD interval of 13.2 ± 12.7 years and 3.9 ± 1.4 years for the civilian and the veteran cohorts, respectively) (Tables 1 and 2). Thus, upregulation of plasma MCP-1 contents among TBI cases is not an acute post-injury response, but more likely reflects a long-term consequence of TBI.

Our observation that plasma MCP-1 contents correlated with the severity of head injury but not measures of TBI symptoms suggests that plasma MCP-1 is a marker of injury per se rather than a marker of a specific injury-related impairments. Recent reports from our group [68] and from others [69-71] have demonstrated reduced FA, implicating impaired axonal pathways in the brains of TBI patients. In our present study, we found a significant correlation between elevated plasma MCP-1 contents and increasing white matter damage in the frontal cortex, as assessed by DTI FA. Our evidence suggests that elevated plasma MCP-1 concentration following TBI may provide a “window into the brain” that is associated with changes in axonal integrity in the brain, particularly in the frontal cortex.

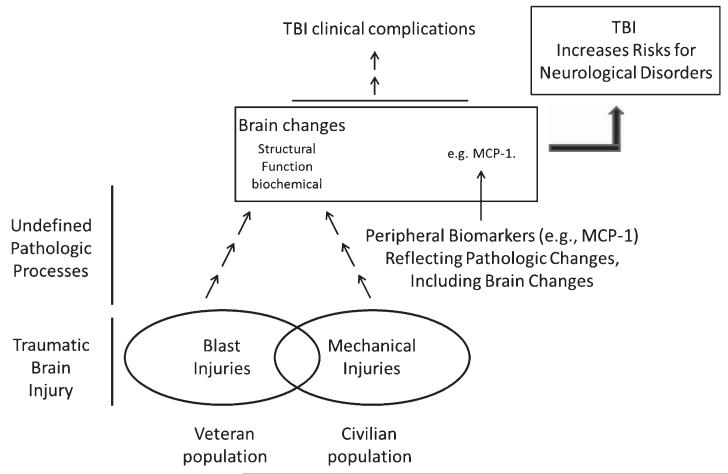

Both TBI and MCI subjects may be at elevated risk for AD dementia. We found significantly elevated MCP-1 expression in the postmortem frontal cortex of MCI cases, suggesting that induction of MCP-1 following TBI might be a potential “predisposition” factor that imposes higher risk for AD or accelerated aging. As we schematically illustrated in Fig. 6, we propose that TBI resulting from either mechanical injuries or blast injuries results in a cascade of biological responses that lead to aberrant biochemical, structural, and/or functional changes in the brain that remain many years post-injury. While mechanisms underlying these pathological modifications are not well defined, it is possible that these changes in the brain may contribute to a chronic clinical course of TBI and/or increased risk for neurodegenerative disorders. Our data presented here suggest that chronic elevation of MCP-1 following TBI may contribute to demyelination processes that, over time, may reduce resilience of the brain to subsequent neurodegenerative insults leading to AD or other neurodegenerative disorders.

Fig. 6.

Proposed mechanisms by which TBI may increase risk for Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders. Schematic represents an overview of a proposed model by which TBI exposure may mechanistically increase subsequent risk for Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders. Accordingly, TBI resulting from either mechanical injuries or blast injuries, which are predominant, respectively, in the civilian or the Veteran population, induces biological responses that lead to aberrant biochemical, structural and/or functional changes in the brain. For example, long-term induction of MCP-1 following TBI may contribute to demyelination processes that, ultimately, may reduce resilience of the brain to subsequent neurodegenerative insults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by UW Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P50AG05136), Pacific Northwest Udall Center (P50NS062684), the ADRC (AG05138 and PPG AG02219), the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development, and the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (UL1RR029887).

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://www.jalz.com/disclosures/view.php?id=1261).

REFERENCES

- [1].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Traumatic brain injury in the United States: A report to congress. 1999. http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/tbi_congress/TBI_in_the_US.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- [2].McDowell S, Whyte J, D’Esposito M. Working memory impairments in traumatic brain injury: Evidence from a dual-task paradigm. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35:1341–1353. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schretlen DJ, Shapiro AM. A quantitative review of the effects of traumatic brain injury on cognitive functioning. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2003;15:341–349. doi: 10.1080/09540260310001606728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Huisman TA, Schwamm LH, Schaefer PW, Koroshetz WJ, Shetty-Alva N, Ozsunar Y, Wu O, Sorensen AG. Diffusion tensor imaging as potential biomarker of white matter injury in diffuse axonal injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:370–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kou Z, Wu Z, Tong KA, Holshouser B, Benson RR, Hu J, Haacke EM. The role of advanced MR imaging findings as biomarkers of traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2010;25:267–282. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181e54793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Scheid R, Walther K, Guthke T, Preul C, von Cramon DY. Cognitive sequelae of diffuse axonal injury. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:418–424. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Elder GA, Cristian A. Blast-related mild traumatic brain injury: Mechanisms of injury and impact on clinical care. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:111–118. doi: 10.1002/msj.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vasterling JJ, Proctor SP, Amoroso P, Kane R, Heeren T, White RF. Neuropsychological outcomes of army personnel following deployment to the Iraq war. JAMA. 2006;296:519–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hannay HJ, Howieson DB, Loring DW, Fischer JS, Lezak MD. Neuropathology for neuropsychologists. In: Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW, editors. Neuropsychological Assessment. Oxford University Press; Oxford [Oxfordshire]: 2004. p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- [10].van Duijn CM, Tanja TA, Haaxma R, Schulte W, Saan RJ, Lameris AJ, ntonides-Hendriks G, Hofman A. Head trauma and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:775–782. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Committee on Gulf War and Health Outcomes . Gulf war and health: Volume 7: Long-term consequences of traumatic brain injury. The National Academic Press; Washington, DC: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ruan L, Kang Z, Pei G, Le Y. Amyloid deposition and inflammation in APPswe/PS1dE9 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:531–540. doi: 10.2174/156720509790147070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Iverson GL, Lange RT, Gaetz M, Zasler ND. Mild TBI. In: Zasler N, Katz D, Zafonte R, editors. Brain Injury Medicine: Principles and Practice. Demos Medical Publishing; New York: 2007. pp. 333–371. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ikonomovic MD, Uryu K, Abrahamson EE, Ciallella JR, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Clark RS, Marion DW, Wisniewski SR, DeKosky ST. Alzheimer’s pathology in human temporal cortex surgically excised after severe brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2004;190:192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Marklund N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Ronne-Engstrom E, Enblad P, Hillered L. Monitoring of brain interstitial total tau and beta amyloid proteins by microdialysis in patients with traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:1227–1237. doi: 10.3171/2008.9.JNS08584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Olsson A, Csajbok L, Ost M, Hoglund K, Nylen K, Rosengren L, Nellgard B, Blennow K. Marked increase of beta-amyloid (1-42) and amyloid precursor protein in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurol. 2004;251:870–876. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Szczygielski J, Mautes A, Steudel WI, Falkai P, Bayer TA, Wirths O. Traumatic brain injury: Cause or risk of Alzheimer’s disease? A review of experimental studies. J Neural Transm. 2005;112:1547–1564. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liliang PC, Liang CL, Weng HC, Lu K, Wang KW, Chen HJ, Chuang JH. Tau proteins in serum predict outcome after severe traumatic brain injury. J Surg Res. 2010;160:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gao X, Deng P, Xu ZC, Chen J. Moderate traumatic brain injury causes acute dendritic and synaptic degeneration in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gobbel GT, Bonfield C, Carson-Walter EB, Adelson PD. Diffuse alterations in synaptic protein expression following focal traumatic brain injury in the immature rat. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:1171–1179. doi: 10.1007/s00381-007-0345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Redell JB, Zhao J, Dash PK. Altered expression of miRNA-21 and its targets in the hippocampus after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:212–221. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Reeves TM, Lyeth BG, Povlishock JT. Long-term potentiation deficits and excitability changes following traumatic brain injury. Exp Brain Res. 1995;106:248–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00241120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Witgen BM, Lifshitz J, Smith ML, Schwarzbach E, Liang SL, Grady MS, Cohen AS. Regional hippocampal alteration associated with cognitive deficit following experimental brain injury: A systems, network and cellular evaluation. Neuroscience. 2005;133:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cohen AS, Pfister BJ, Schwarzbach E, Grady MS, Goforth PB, Satin LS. Injury-induced alterations in CNS electrophysiology. Prog Brain Res. 2007;161:143–169. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)61010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Alberini CM. Transcription factors in long-term memory and synaptic plasticity. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:121–145. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gardiner E, Beveridge NJ, Wu JQ, Carr V, Scott RJ, Tooney PA, Cairns MJ. Imprinted DLK1-DIO3 region of 14q32 defines a schizophrenia-associated miRNA signature in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Mol Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.78. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Patanella AK, Zinno M, Quaranta D, Nociti V, Frisullo G, Gainotti G, Tonali PA, Batocchi AP, Marra C. Correlations between peripheral blood mononuclear cell production of BDNF, TNF-alpha, IL-6, IL-10 and cognitive performances in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:1106–1112. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].van Heerden JH, Conesa A, Stein DJ, Montaner D, Russell V, Illing N. Parallel changes in gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and the brain after maternal separation in the mouse. BMC Res Note. 2009;2:195. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kim SM, Song J, Kim S, Han C, Park MH, Koh Y, Jo SA, Kim YY. Identification of peripheral inflammatory markers between normal control and Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lee ST, Chu K, Jung KH, Park HK, Kim DH, Bahn JJ, Kim JH, Oh MJ, Lee SK, Kim M, Roh JK. Reduced circulating angiogenic cells in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;72:1858–1863. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a711f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mayeux R, Reitz C, Brickman AM, Haan MN, Manly JJ, Glymour MM, Weiss CC, Yaffe K, Middleton L, Hendrie HC, Warren LH, Hayden KM, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Breitner JC, Morris JC. Operationalizing diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease and other age-related cognitive impairment-Part 1. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:15–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cederberg D, Siesjo P. What has inflammation to do with traumatic brain injury? Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:221–226. doi: 10.1007/s00381-009-1029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Morganti-Kossmann MC, Satgunaseelan L, Bye N, Kossmann T. Modulation of immune response by head injury. Injury. 2007;38:1392–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ramlackhansingh AF, Brooks DJ, Greenwood RJ, Bose SK, Turkheimer FE, Kinnunen KM, Gentleman S, Heckemann RA, Gunanayagam K, Gelosa G, Sharp DJ. Inflammation after trauma: Microglial activation and traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:374–383. doi: 10.1002/ana.22455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tanriverdi F, Unluhizarci K, Kelestrimur F. Persistent neuroinflammation may be involved in the pathogenesis of traumatic brain injury (TBI)-induced hypopituitarism: Potential genetic and autoimmune factors. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:301–302. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ziebell JM, Morganti-Kossmann MC. Involvement of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cantor JB, Gordon WA, Schwartz ME, Charatz HJ, Ashman TA, Abramowitz S. Child and parent responses to a brain injury screening questionnaire. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:S54–S60. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.08.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gordon WA, Haddad L, Brown M, Hibbard MR, Sliwinski M. The sensitivity and specificity of self-reported symptoms in individuals with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2000;14:21–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kay T, Harrington DE, Adams R. Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabilit. 1993;8:86–87. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ray S, Britschgi M, Herbert C, Takeda-Uchimura Y, Boxer A, Blennow K, Friedman LF, Galasko DR, Jutel M, Karydas A, Kaye JA, Leszek J, Miller BL, Minthon L, Quinn JF, Rabinovici GD, Robinson WH, Sabbagh MN, So YT, Sparks DL, Tabaton M, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage JA, Tibshirani R, Wyss-Coray T. Classification and prediction of clinical Alzheimer’s diagnosis based on plasma signaling proteins. Nat Med. 2007;13:1359–1362. doi: 10.1038/nm1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Huang RP. Cytokine protein arrays. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;264:215–231. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-759-9:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, Watkins KE, Ciccarelli O, Cader MZ, Matthews PM, Behrens TE. Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage. 2009;44:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Haroutunian V, Perl DP, Purohit DP, Marin D, Khan K, Lantz M, Davis KL, Mohs RC. Regional distribution of neuritic plaques in the nondemented elderly and subjects with very mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1185–1191. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.9.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rhodes JK, Sharkey J, Andrews PJ. The temporal expression, cellular localization, and inhibition of the chemokines MIP-2 and MCP-1 after traumatic brain injury in the rat. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:507–525. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Stefini R, Catenacci E, Piva S, Sozzani S, Valerio A, Bergomi R, Cenzato M, Mortini P, Latronico N. Chemokine detection in the cerebral tissue of patients with posttraumatic brain contusions. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:958–962. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/5/0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Grammas P, Ovase R. Inflammatory factors are elevated in brain microvessels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:837–842. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ishizuka K, Kimura T, Igata-yi R, Katsuragi S, Takamatsu J, Miyakawa T. Identification of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in senile plaques and reactive microglia of Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;51:135–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1997.tb02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Janelsins MC, Mastrangelo MA, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Federoff HJ, Bowers WJ. Early correlation of microglial activation with enhanced tumor necrosis factor-alpha and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression specifically within the entorhinal cortex of triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:23. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Archer T, Svensson K, Alricsson M. Physical exercise ameliorates deficits induced by traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012;125:293–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Dams-O’Connor K, Gordon WA. Role and impact of cognitive rehabilitation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:893–904. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Qu C, Mahmood A, Ning R, Xiong Y, Zhang L, Chen J, Jiang H, Chopp M. The treatment of traumatic brain injury with velcade. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1625–1634. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Svetlov SI, Larner SF, Kirk DR, Atkinson J, Hayes RL, Wang KK. Biomarkers of blast-induced neurotrauma: Profiling molecular and cellular mechanisms of blast brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:913–921. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Conductier G, Blondeau N, Guyon A, Nahon JL, Rovere C. The role of monocyte chemoattractant protein MCP1/CCL2 in neuroinflammatory diseases. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;224:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Correa JD, Starling D, Teixeira AL, Caramelli P, Silva TA. Chemokines in CSF of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69:455–459. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2011000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hickman SE, El KJ. Mechanisms of mononuclear phagocyte recruitment in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9:168–173. doi: 10.2174/187152710791011982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Kim JS. Cytokines and adhesion molecules in stroke and related diseases. J Neurol Sci. 1996;137:69–78. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kooij G, Mizee MR, van HJ, Reijerkerk A, Witte ME, Drexhage JA, van der Pol SM, van Het HB, Scheffer G, Scheper R, Dijkstra CD, van der Valk P, de vries HE. Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporters mediate chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 secretion from reactive astrocytes: Relevance to multiple sclerosis pathogenesis. Brain. 2011;134:555–570. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Mahad DJ, Ransohoff RM. The role of MCP-1 (CCL2) and CCR2 in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) Semin Immunol. 2003;15:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s1044-5323(02)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Minami M, Satoh M. Chemokines and their receptors in the brain: Pathophysiological roles in ischemic brain injury. Life Sci. 2003;74:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Xia MQ, Hyman BT. Chemokines/chemokine receptors in the central nervous system and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurovirol. 1999;5:32–41. doi: 10.3109/13550289909029743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Banisor I, Leist TP, Kalman B. Involvement of beta-chemokines in the development of inflammatory demyelination. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Chandler S, Coates R, Gearing A, Lury J, Wells G, Bone E. Matrix metalloproteinases degrade myelin basic protein. Neurosci Lett. 1995;201:223–226. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Cross AK, Woodroofe MN. Chemokine modulation of matrix metalloproteinase and TIMP production in adult rat brain microglia and a human microglial cell line in vitro. Glia. 1999;28:183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Tanuma N, Sakuma H, Sasaki A, Matsumoto Y. Chemokine expression by astrocytes plays a role in microglia/macrophage activation and subsequent neurodegeneration in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:195–204. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Tang CY, Eaves EL, Dams-O’Connor K, Ho L, Leung E, Wong E, Carpenter D, Ng J, Gordon WA, Pasinetti GM. Diffused disconnectivity in mild traumatic brain injury: A resting state fMRI and DTI study. Translational Neuroscience. 2012;3(1):9–14. doi: 10.2478/s13380-012-0003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Maller JJ, Thomson RH, Lewis PM, Rose SE, Pannek K, Fitzgerald PB. Traumatic brain injury, major depression, and diffusion tensor imaging: Making connections. Brain Res Rev. 2010;64:213–240. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Tasker RC, Westland AG, White DK, Williams GB. Corpus callosum and inferior forebrain white matter microstructure are related to functional outcome from raised intracranial pressure in child traumatic brain injury. Dev Neurosci. 2010;32:374–384. doi: 10.1159/000316806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Wilde EA, Chu Z, Bigler ED, Hunter JV, Fearing MA, Hanten G, Newsome MR, Scheibel RS, Li X, Levin HS. Diffusion tensor imaging in the corpus callosum in children after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1412–1426. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Basser PJ, Pajevic S, Pierpaoli C, Duda J, Aldroubi A. In vivo fiber tractography using DT-MRI data. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:625–632. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200010)44:4<625::aid-mrm17>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]