Abstract

Aneuploidy is common in human tumours and is often indicative of aggressive disease. Aneuploidy can result from cytokinesis failure, which produces binucleate cells that generate aneuploid offspring with subsequent divisions. In cancers, disruption of cytokinesis is known to result from genetic perturbations to mitotic pathways or checkpoints. Here we describe a non-genetic mechanism of cytokinesis failure that occurs as a direct result of cell-in-cell formation by entosis. Live cells internalized by entosis, which can persist through the cell cycle of host cells, disrupt formation of the contractile ring during host cell division. As a result, cytokinesis frequently fails, generating binucleate cells that produce aneuploid cell lineages. In human breast tumours, multinucleation is associated with cell-in-cell structures. These data define a novel mechanism of cytokinesis failure and aneuploid cell formation that operates in human cancers.

Genetic instability is a hallmark of human cancer. Human tumours exhibit a variety of genetic alterations, including point mutations, translocations, gene amplifications and deletions, and also aneuploid chromosome numbers 1. For carcinomas, aneuploidy is associated with poor patient outcome for a variety of tumour types including breast 2, colon 3, endometrial 4,5, and renal cell carcinoma 6.

One condition that can lead to aneuploidy is the presence of excess centrosomes, which generate aneuploid cells by producing multipolar spindles, as proposed by Boveri nearly a century ago 7–9. Because many carcinomas are hyperdiploid, it is thought that a tetraploidy generating event, such as cytokinesis failure, is one common mechanism to amplify centrosome number in tumour cells. Indeed, the tetraploid state has been shown to promote chromosome missegregation and rearrangements, and to contribute to tumourigenesis in a breast tumour model 10. In this study, p53-null mouse mammary epithelial cells rendered tetraploid by treatment with cytochalasin B, which disrupts cytokinesis, formed tumours in mice whereas their diploid counterparts could not, clearly demonstrating the tumour-promoting capacity of the tetraploid state 10.

Cytokinesis failure can be provoked by the misregulation or mutation of genes whose products mediate mitotic progression. For example, overexpression of the mitotic kinase Aurora-A, which correlates with high grade and poor outcome in human breast carcinomas 11, induces centrosome amplification and the formation of tetraploid cells in a mouse mammary tumour model 12. However, it remains unclear whether the large extent of polyploidy that occurs across a broad spectrum of human tumours is the result of disruption of mitotic pathways. Polyploid cells can also be generated by mechanisms other than cytokinesis failure, such as endoreduplication or mitotic slippage (induced by spindle poisons) 13–16, and by mechanisms not involving primary mitotic defects, such as cell fusion 17,18. In cancers, direct evidence of cell fusion is rare, although cell fusion induced by viral infection can promote tumourigenesis 19.

Recently we described a process termed entosis, whereby viable cells are internalized into neighboring cells, forming cell-in-cell structures 20. Cell-in-cell structures are found in a variety of human tumours, and have been reported for decades, but their role in tumourigenesis remains unknown 21. Entosis is provoked by loss of cell adhesion to matrix, and is prevalent in cells cultured in suspension or in anchorage-independent growth assays in soft agar. The majority of cells internalized by this mechanism eventually die, suggesting that cell-in-cell formation could function to eliminate cells detached from proper matrix adhesion. We reported the detection of cell-in-cell structures in regions of solid primary human breast tumours where no detectable collagen, laminin 3-3-2, or fibronectin were observed 20, suggesting that entosis could eliminate cells during tumour formation when cells detach from the basement membrane.

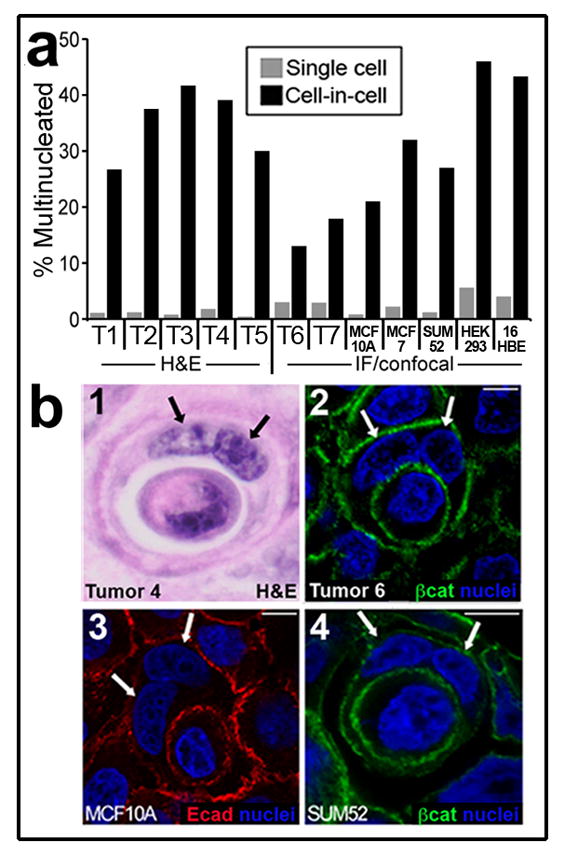

While examining cell-in-cell structures in human breast tumours, we noted that many of the outer, host cells were bi- or multinucleated (Fig. 1). To quantify this observation, tumours exhibiting cell-in-cell structures were examined by hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E), or by immunofluorescence (IF) and confocal microscopy, and the number of nuclei per cell was counted. In seven tumours examined, host cells showed a high degree of multinucleation (~15–40 percent of cells), while the adjacent tumour cells in the same microscopic fields were rarely multinucleated (Fig. 1). Similarly, we found that host cells of cell-in-cell structures were multinucleated in cultured cell lines at an approximate 10-fold higher frequency than adjacent single cells (Fig. 1). Because cell-in-cell structures are often reported in tumour cell populations harvested from human fluid accumulations 21, we also examined metastatic exudates in pleural fluids from breast cancer patients, and found that host cells were more frequently multinucleated than adjacent tumour cells in five of eight samples (Supplementary Information Fig. S1). Multinucleation frequencies were high (~60%) in all cells in the other three samples.

Figure 1. Cell-in-cell structures are multinucleated.

(a) Cells in primary human tumours and in culture quantified for multinucleation. ‘Single cell’ = single cells from tumours or cell lines in the same fields as cell-in-cell structures (gray bars); ‘cell-in-cell’ = host cells of cell-in-cell structures (black bars). Left side of graph, % cell-in-cell with multinucleation for human breast tumours (labeled T1-T5), quantified in 10 high power fields (H&E). For single cells, T1-T5, n=3015, 2743, 1984, 2851, 1605; for cell-in-cell, T1-T5, n=15, 24, 12, 23, 10. For T1-T5 p<.001 (Fisher Exact test). Note T1-T5 are high-grade tumours from the set shown in Supplementary Information Figure-S5. Right side of graph, % multinucleation quantified by immunofluorescence (IF) and confocal microscopy, for two primary human breast tumours (T6, T7) and cell lines MCF10A, MCF7, SUM52, HEK293, 16HBE. T6 p<.001 (n=4202 for single cells, n=193 for cell-in-cell); T7 p<.001 (n=1356 for single cells, n=67 for cell-in-cell); MCF10A p<.001 (n=1521 for single cells, n=114 for cell-in-cell); MCF7 p<.001 (n=1575 for single cells, n=87 for cell-in-cell); SUM52 p<.001 (n=1026 for single cells, n=109 for cell-in-cell); HEK-293 p<.001 (n=485 for single cells, n=50 for cell-in-cell); 16HBE-H2B-mCherry p<.001 (n=1306 for single cells, n=90 for cell-in-cell). T6 and T7 were published previously20 in Fig. 6E as human tumours 2 and 1, respectively. (b) Image 1: H&E stained breast carcinoma (T4); images 2–4: IF of breast carcinoma (2, T6) or cell lines (3,4) stained for β-catenin (green) or E-cadherin (red) and nuclei (blue). Arrows: nuclei of binucleated host cells. Bars = 10μm.

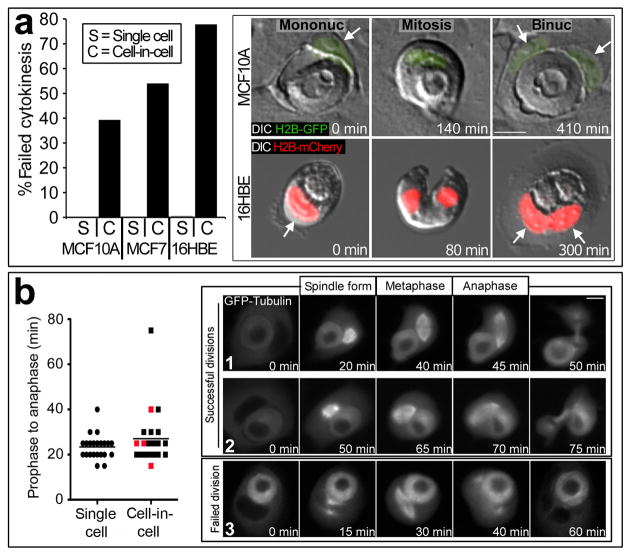

The multinucleation of host cells could reflect either an increased propensity of multinucleated cells to serve as hosts in cell-in-cell structures, or rather that the cell-in-cell condition itself induces multinucleation after structures are formed. To investigate if cell-in-cell structures provoke multinucleation, we examined mitotic events involving cell-in-cell structures by time-lapse microscopy. Strikingly, host cells failed division at high frequency (from ~40 to 80 percent of divisions in three different cell lines) compared to adjacent single cells (~0.3 to 0.6%) (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Information Movie S1, S2). In further analyses of cells expressing GFP-labeled α-tubulin (GFP-tubulin), which marks mitotic spindles, we observed no significant effects on spindle morphology, or the duration of prophase to anaphase, when comparing cell-in-cell divisions with divisions of adjacent single cells (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Information Movies S3–S5). Cells that failed cytokinesis also did not show any noticeable differences in spindle morphology or prophase to anaphase timing compared to cells that divided normally (Fig. 2b). In these experiments, we did not observe any effects on the midbody or division failures that were associated with a disruption of abscission. The disruptive effects of internalized cells on host cell divisions therefore appeared to be restricted to telophase or early cytokinesis.

Figure 2. Host cells fail cytokinesis.

(a) Graph: % failed mitoses (time-lapse analysis) of MCF10A-H2B-GFP cells (single cells n=1893; cell-in-cell, n=178; p<.001 (Fisher Exact test)), MCF7 cells (single cells n=298, cell-in-cell n=35; p<.001), and 16HBE cells (single cells n=1277, cell-in-cell n=36; p<.001). Images show failed divisions of MCF10A (top row) and 16HBE (bottom row). Left images: mononucleate (arrow) cell-in-cell structures; Middle: mitosis initiated by host cells; Right: binucleate (arrows) host cells after cytokinesis failure. See Movies S1 and S2. (b) Internalized cells do not disrupt spindle formation. Graph: prophase to anaphase timing for single cells (left, n=22) or host cells (right, n=22), determined by time-lapse of GFP-Tubulin-expressing MCF10A cells; p=0.41 (Mann-Whitney). Data points show individual mitoses timed from spindle formation to anaphase, bar represents mean. Red data points are failed divisions. Representative images from successful (1,2) and failed (3) host cell divisions are shown. See Movies S3–S5. Bars = 10μm.

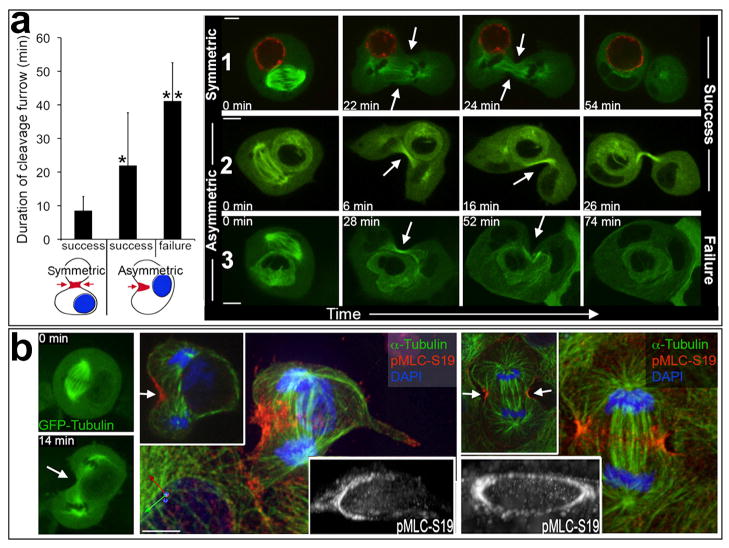

We hypothesized that internalized cells disrupt cytokinesis by physically blocking the cleavage furrow. If this were the case, then cytokinesis events involving internalized cells oriented within the cleavage plane would fail, while divisions with internalized cells positioned away from the cleavage plane would be completed successfully. To examine this hypothesis, the positioning of internalized cells with respect to the cleavage furrow was tracked in 3-dimensions (3D) by time-lapse imaging using a spinning-disc confocal microscope. As the majority of failed divisions appeared to be blocked in early stages of cytokinesis, 3D analyses were restricted to imaging from metaphase to the onset of abscission, marked by the appearance of a midbody. Thirty divisions of host cells harboring internalized cells were imaged in 3D. Similar to the results with widefield microscopy, we did not observe morphological changes or disruptions of mitotic spindles due to internalized cells. In 11 of the 30 total divisions, internalized cells were positioned away from the cleavage furrow, and each of these divisions was completed successfully (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Information Movie S6). In the remaining 19 divisions, internalized cells were positioned within the plane of attempted cleavage, and 6 of these divisions failed to complete cytokinesis, forming binucleate host cells (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Information Movies S7–8). Interestingly, in each of the 11 divisions with internalized cells positioned away from the furrow, ingression of the contractile ring occurred symmetrically around the circumference of the furrow (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Information Movie S6). By contrast, host cells dividing with internalized cells positioned within the furrow contracted asymmetrically while attempting cytokinesis (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Information Movies S7,8). Similar effects of internalized cells on the symmetry of the cleavage furrow were observed with a second cell line, HEK-293 (Supplementary Information Fig. S2, Movie S9). For asymmetric cleavages, the length of time of contraction was longest for divisions that ultimately failed (Fig. 3a), suggesting that cells which fail cytokinesis are unable to complete ingression before the furrow ceases contracting.

Figure 3. Internalized cells disrupt cleavage furrow formation.

(a) Graph: duration of cleavage furrow determined by 3D imaging (mean +/− S.D.). Left bar, internalized cells away from cleavage plane, host cells with symmetric furrow (n=11; all divisions successful). Middle and right bars: internalized cells within cleavage plane, host cells with asymmetric furrows (n=19; 13 successful and 6 failed). Successful asymmetric divisions had longer furrow duration than symmetric divisions (*p<.001, Mann-Whitney), and failed asymmetric divisions had longer furrow duration than successful ones (**p=.018, Mann-Whitney). Blue circles in cartoons (below graph) represent internalized cells, and red regions (arrows) represent cleavage furrows. Time-lapse images are shown for symmetric (1) and asymmetric (2,3), and successful (1,2) and failed (3) divisions. Arrows indicate cleavage furrows (See also Movies S6–8). (b) Internalized cells block cleavage furrow formation. Left images: time-lapse of MCF10A-GFP-Tubulin cells from metaphase (top image) to telophase with asymmetric furrow (bottom image) (See Movie S10). Middle image panel: same cell from time-lapse, stained for phosphorylated myosin light chain serine 19 (pMLC-S19) (red), α-Tubulin (green), and nuclei (blue). Note contractile ring (pMLC) only half-formed (white arrow). Main image is 3D reconstruction (axes labeled at bottom left x (green), y (red), z (blue)). Left inset is single x-y plane. Right inset, 3D reconstruction of pMLC-S19 staining shown as grayscale and angled to visualize contractile ring. Right image panel shows normal cell division; main image is 3D reconstruction, left inset is single x-y plane, right inset shows 3D reconstructon of pMLC-S19 staining (grayscale), angled to visualize contractile ring. All bars = 10μm.

Because cell-in-cell formation by entosis is provoked by matrix detachment 20, we examined divisions involving cell-in-cell structures that formed during colony growth assays in soft agar. These conditions force cells to grow without anchorage to substrate, mimicking the conditions in some solid tumours where cells are displaced from the basement membrane 20, or lose expression of matrix receptors22. Cells expressing a GFP-tagged E-cadherin protein (Ecad-GFP), to mark adherens junctions, which are required for entosis 20, and the red fluorescent nuclear marker H2B-mCherry, were imaged in soft agar in 3-dimensions. In total, 40 divisions involving complete or partial cell-in-cell structures were imaged. Seven divisions occurred after cell-in-cell structure formation was completed, as determined by the full enclosure of internalized cells within the host cell. Thirty-three divisions involved partial cell-in-cell structures where host cells divided before internalized cells were fully enclosed. Under these nonadherent conditions, host cells were even more prone to cytokinesis failure than under adherent conditions - each of the seven divisions (100%) occurring with completed cell-in-cell structures failed cytokinesis, forming binucleate hosts (Supplementary Information Fig. S3, Movie S11). Surprisingly, 6 of the 33 (18%) host cells that were only partially enclosing internalized cells also exhibited cytokinesis failure, demonstrating that even partial enwrapping of one cell by another can block division (Supplementary Information Fig. S3, Movie S12). Similar to adherent conditions, failure of host cells to complete cytokinesis in partial or completed structures was associated with asymmetric furrowing (See Movies S11, S12).

To disrupt furrowing, it is conceivable that internalized cells could either block the formation of contractile rings, or block the ingression of contractile rings that are completely formed. To examine contractile rings in cell-in-cell mitoses, structures expressing GFP-Tubulin were analyzed by 3D time-lapse, and divisions with asymmetric cleavages were fixed at the onset of furrowing and stained by IF for phosphorylated myosin light chain 2 (pMLC–Serine 19), which marks active myosin contraction. By IF, cell-in-cell structures with asymmetric furrowing displayed asymmetric distribution of pMLC, which appeared as a contractile ring that was only half-formed (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Information Movie S9). In total, 13 asymmetric divisions were analyzed, and each lacked pMLC at the cortex proximal to internalized cells (Supplementary Information Fig. S4-a). Interestingly, about half (6/13) of asymmetric divisions displayed pMLC staining at the vacuolar membrane that surrounds internalized cells (Supplementary Information Fig. S4-b), demonstrating that microtubules can signal to this membrane in the absence of access to the cortex proximal to internalized cells. Such contractions could conceivably complete cytokinesis between the plasma membrane and the vacuole, which would create binucleate hosts and release internalized cells. But, division failures coincident with internalized cell release were rare from time-lapse analyses (6% of failed divisions (n=50)), suggesting that the majority of potential cytokinesis events between these membranes are not completed. Two symmetric divisions were also stained for pMLC and these displayed completed contractile rings (Supplementary Information Fig. S4-c). Taken together, these data demonstrate that internalized cells disrupt cytokinesis by blocking contractile ring formation, leading to asymmetric furrowing.

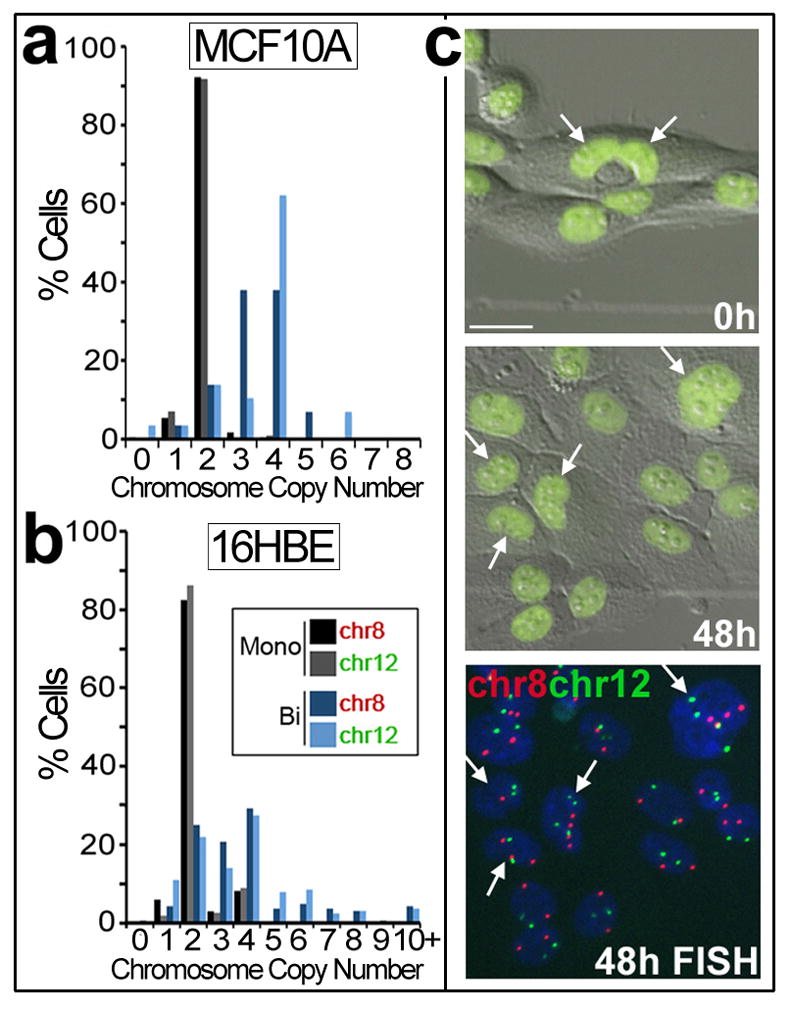

The data presented here support a model whereby cells internalized by entosis disrupt cytokinesis if by chance they are caught within the plane of cell division. By this mechanism, cell-in-cell structures can induce binucleation in human tumours. Binucleate cells are predicted to contribute to aneuploidy and genomic instability after further cell divisions, particularly those involving multipolar spindles, or transient multipolar spindles, randomly distribute chromosomes and promote chromosome breakage7,23. To examine the potential of binucleate host cells generated by this mechanism to divide and produce aneuploid cell lineages, cells expressing H2B-GFP were imaged by time-lapse microscopy (Supplementary Information Movie S13), and then fixed and stained by two colour FISH to quantify the number of chromosomes per cell. Interestingly, similar to most mammalian cells 24,25, MCF10A cells do not exhibit a strong tetraploidy checkpoint, as binucleate host cells underwent division, although at a reduced rate compared to neighboring cells. Over a 20-hour period, 49% of binucleate host cells divided (n=78) compared to 78% of adjacent single cells (n=353). Binucleate cells (n=74) exhibited bipolar (66%) and tripolar (23%) divisions, and some hosts failed cytokinesis (a second time) (11%) due to the continued presence of internalized cells. FISH analysis of chromosomes 8 and 12 revealed that cells arising from binucleate cell-in-cell structures were polyploid (mode = 4n), and 62% (chr8), or 38% (chr12) of the population deviated from the mode compared to only 8% of control cells (Fig. 4), demonstrating a high level of aneuploidy in cell lineages arising from binucleate hosts. Similarly, cells arising from binucleate 16-HBE cells, which also form cell-in-cell structures that disrupt cytokinesis (Fig. 1), exhibited significant deviation from the mode (70% for chromosome 8 and 72% for chromosome 12), compared to the mononucleate lineage (18% for chromosome 8 and 14% for chromosome 12) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Binucleated cell-in-cell structures generate aneuploid lineages.

(a) MCF10A-H2B-GFP cells were time-lapsed for 48 hours, and progeny cells arising from mononucleate single cells (black, gray bars; n=243) or binucleate cell-in-cell structures (dark, light blue bars; n=29) were examined by FISH (See Movie S13). Bars represent % progeny cells with 0–8 copies of chromosome 8 or 12. (b) Similar analyses as in (a) for 16HBE cells expressing H2B-mCherry (red). Graph shows % progeny cells arising from mononucleate single cells (black, gray bars; n=268) or binucleate cells (dark, light blue bars; n=164) with 0 to 10+ copies of chromosome 8 or 12. (c) Images from MCF10A time-lapse, for graph in (a). Arrows indicate binucleated cell-in-cell structure (left image –note internalized cell is degrading and lacks H2B-GFP fluorescence) and progeny cells (middle image) examined by FISH (right image). Bar = 20μm. See Movie S13.

Together these data demonstrate that cell-in-cell formation by entosis can lead to aneuploidy, a hallmark of human carcinomas. By contrast to established models of genomic or chromosomal instability involving mutational disruption of mitotic checkpoints or pathways, cell-in-cell formation represents a non-genetic route to disrupting the genome. Tumour cells acquiring aneuploidy and chromosomal instability by this route could initially maintain properly functioning mitotic pathways and checkpoints; although, the propagation of such cells would also likely require cooperating hits to tumor suppressors such as p53 to enhance cell viability10. Rates of aneuploidy are high in such cell lineages because division failure not only doubles cell ploidy, but also doubles centrosome number. Extra centrosomes can generate extensive aneuploidy by promoting multipolar cell divisions, and can also promote single chromosome gains and losses due to merotelic spindle attachments that are induced by transient multipolar spindle intermediates7,26. It is the latter which may be more strongly tumor-promoting as massive aneuploidy can compromise cell viability whereas single chromosome events are better tolerated7.

By analogy, the effects of cell-in-cell structures in breast carcinoma are similar to the effects of asbestos fibers in mesothelioma, which can act as a physical barrier to cell division by lodging in the cleavage furrow or midbody to prevent cytokinesis27. Cell-in-cell structures are also reminiscent of a classic model used by Rappaport to examine the relationship between spindle positioning and the cleavage furrow, involving sand dollar eggs with inserted glass beads28. Like internalized cells, large glass beads disrupted furrow formation at the cortex distal to the spindle, providing evidence for an active role of the spindle in furrow induction28. Interestingly, whereas sand dollar eggs could complete cytokinesis-like events between the cell membrane and the membrane proximal to glass beads, leading to the formation of binucleate, open horseshoe-shaped cells, cell-in-cell structures do not frequently complete such pseudo-cell divisions, even though many host cells do assemble contractile machinery near the vacuole (see Supplementary Information Fig. S4b).

These data raise interesting questions regarding entosis, since this process can mediate death of tumour cells and therefore could be tumour suppressive 20, but the studies in this report demonstrate that entosis can also drive aneuploidy, a hallmark of aggressive tumours. Previously it was reported that the frequency of cell-in-cell structures correlates with high grade in human breast tumours 29. High-grade breast tumours are more aggressive and more likely to recur than low-grade tumours, and are characterized in part by increases in the size and shape variation of cell nuclei (nuclear pleomorphism). We quantified cell-in-cell structures in a panel of human breast tumours and also found that cell-in-cell frequency correlates with high grade (Supplementary Information Fig. S5). Based on our studies here, it is conceivable that in such tumours, cell-in-cell structures contribute to nuclear pleomorphism and to tumour progression by provoking cytokinesis failure. Hypothetically, the elimination of cells by entosis could slow the formation of primary tumours, but in the process, also contribute to longer-term acquisition of aggressive characteristics downstream of chromosomal instability. As entosis is provoked by a loss of cell adhesion to extracellular matrix 20, which could occur as epithelial cancers are first forming, the act of tumour formation itself could provoke the development of aneuploidy through cell-in-cell structures that form as tumour cells proliferate or migrate away from the normal matrix environment.

It is important to point out that entosis is only one mechanism by which viable cells can internalize into neighbors to form cell-in-cell structures. For example, a variety of human tumour cells have been demonstrated to internalize live leukocytes 21. In metastatic melanoma, the internalization of live lymphocytes followed by their degradation can promote tumour cell survival under conditions of nutrient deprivation 30. It is likely that cell-in-cell structures involving any type of internalized cell can provoke cytokinesis failure. By this general mechanism, aneuploidy could develop in some human tumours when mitotic pathways are, at least initially, functioning properly.

Experimental Methods

Cell culture

MCF10A and MCF7 cells were cultured as described20. SUM52 cells were cultured in Ham’s F12 + hydrocortisone (1μg/ml), insulin (5μg/ml), and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). HEK-293 cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in DMEM + 10% FBS. 16HBE cells were cultured in MEM + 10%FBS. Expression constructs for H2B-GFP20, H2B-mCherry, mCherry-CAAX, and GFP-Tubulin were introduced into cells by retroviral transduction, and stable cell lines were selected as described 20. Immunofluorescent staining was performed as described 20. To quantify multinucleation, cells were examined by confocal microscopy, and cell-in-cell structures were quantified for multinucleation frequencies of outer cells versus adjacent single cells in the same microscopic fields.

Human tumours

Pleural fluid samples were prepared for cytologic examination using a standard clinical cytology preparation method. A 50 ml aliquot (or the entire sample if less than 50 ml) was centrifuged at 1800 rpm for 10 min. The sediment was washed with 15–30 ml CytoLyt solution (Hologic, Marlborough, MA) at 1800 rpm for 10 min. Two to 4 drops of the sediment were pipetted into a vial containing PreservCyt solution (Hologic, Marlborough, MA) and incubated at room temperature for at least 20 min. The suspended cells were transferred onto a glass slide with the ThinPrep 2000 (Hologic, Marlborough, MA), fixed in 95% ethanol, and stained with the Papanicolaou stain. Malignant breast cancer cells were identified and distinguished from mesothelial cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes using standard cytologic criteria 31. Malignant cells exhibiting cell-in-cell arrangements were identified, and the number of mononucleated vs. multinucleated outer cells was recorded using a Laboratory Counter (FisherScientific). Similarly, malignant cells lacking cell-in-cell arrangement were identified, and the number of mononucleated vs. multinucleated outer cells was recorded. Malignant cells in large clusters were not included in the enumerations because of the difficulty in distinguishing multinucleated cells from non-multinucleated cells. Only obviously malignant cells were counted. Primary human breast carcinoma (invasive ductal carcinoma) sections were stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunofluorescence as described 20. To quantify multinucleation in solid tumour H&E stained sections, 10 high power fields (HPF) (200X) were quantified for H&E counts, including tumour cells, multinucleated tumour cells, cell-in-cell structures (verified at 400X when necessary), and multinucleated cell-in-cell structures, or the indicated cells were counted by confocal microscopy (for immunofluorescence) at 600X. Cell-in-cell structures were counted for multinucleation versus single tumour cells in the same microscopic fields.

Time-lapse microscopy

Time-lapse microscopy was performed essentially as described 20. For monolayers, cells were plated onto untreated 35mm or 6-well coverglass bottom dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) overnight, and cell-in-cell structures in the monolayer the next day were imaged by time-lapse microscopy. For mixed cultures, mCherry-CAAX expressing cells were plated with GFP-Tubulin expressing cells at a 1:1 ratio. Fluorescence and differential interference contrast (DIC) or phase contrast images were obtained at the indicated time intervals, using a Nikon TI-E inverted microscope, a CoolSNAP HQ2 CCD camera, and live cell incubation chamber to maintain cells at 37°C and 5%CO2. For confocal microscopy, images were acquired in 0.5 or 1μm z-steps, at 30 second to 2 minute intervals, using the Ultraview spinning disc confocal system (Perkin Elmer), a Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope, and Hamamatsu C9100-13 EMCCD camera, and cells were maintained in an incubation chamber at 37°C and 5%CO2. Images and movies were acquired with Nikon Elements or Volocity software (Perkin Elmer) and processed using Adobe Photoshop and Image J. Quantification of the effects of internalized cells on host cell divisions in Figure 2 was restricted to cell-in-cell structures with live internalized cells.

For time-lapse assays in soft agar, 35mm coverglass dishes were pretreated with polyhema (6mg/ml in 95% ethanol) to prevent cell adherence, as described 20. Cells were trypsinized and plated into suspension cultures on ultra low-attachment culture plates (Corning) for approximately 3 hours to allow cell-cell junctions to form, and then were harvested, triturated, plated on the pre-treated coverslip dishes in growth media with 0.25% low-melting temperature agar at 37°C for 1 hour (to allow cells to settle near the pre-treated glass coverslip), and placed at 4°C for 15 minutes to solidify the agar. Cultures were returned to 37°C before starting time-lapse imaging.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescent staining was performed as described 20, using antibodies against α-Tubulin (clone DM1A) (Sigma), phosphorylated myosin light chain 2(serine 19) (Cell Signaling), β-catenin (BD Biosciences), and E-cadherin (BD Biosciences).

FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to quantify chromosomes 8 and 12 was performed using the Vysis CEP8 kit and CEP12 Alpha (Abbott Molecular). To prepare cell cultures, MCF10A cells expressing H2B-GFP or 16HBE cells expressing H2B-mCherry were plated onto gridded (Photo-etched) coverslips (Electron Mycroscopy Sciences), time-lapsed for 48 hours, and then immediately fixed in 3:1 methanol:acetic acid, and processed for FISH analysis as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells from the time-lapse were identified by grid position. Chromosomes were quantified using the criteria recommended by the manufacturer.

Statistical analyses

The indicated statistical tests were conducted on the SISA website http://www.quantitativeskills.com/sisa/, or by using Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Supplementary Material

Timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressing H2B-GFP (green). Time is shown as minutes (min). White arrows indicate host cell nuclei before and after cytokinesis failure.

Confocal timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expessing GFP-Tubulin (green). Images are single x-y plane. Time is shown as minutes (min). Note culture was fixed immediately after timelapse (at 14 min) and processed for immunofluorescence for pMLC-S19 and α-Tubulin.

Confocal timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressig E-cadherin-GFP (green) and H2B-mCherry (red). Time is shown as minutes (min). Images are single x-y plane. Note this host cell expresses a high background of E-cadherin-GFP. After cell-in-cell structure completes formation, host cell attempts division with asymmetric cleavage furrow and fails cytokinesis.

Confocal timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressig E-cadherin-GFP (green) and H2B-mCherry (red). Time is shown as minutes (min). Images are single x-y plane. Note cell-cell junction marked by E-cadherin plaques, and inner cell extending out of host cell during the attempted host cell division. Note host cell has asymmetric cleavage furrow and fails cytokinesis.

Timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expessing H2B-GFP (green). Time is shown as minutes (hours:minutes:seconds). Culture was fixed immediately after timelapse (at 48 hours) and processed for 2-colour FISH analysis to quantify the copy number of chromosomes 8 and 12.

Timelapse analysis of 16HBE cells expressing H2B-mCherry (red). Time is shown as minutes (min).

Timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressing GFP-Tubulin (green). Time is shown as minutes (min). Left frame is phase contrast, right frame is GFP fluorescence.

Timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressing GFP-Tubulin (green). Time is shown as minutes (min). Left frame is phase contrast, right frame is GFP fluorescence.

Timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressing GFP-Tubulin (green). Time is shown as minutes (min). Left frame is DIC, right frame is GFP fluorescence.

Confocal timelapse analysis of mixed MCF10A cell-in-cell structure with GFP-Tubulin (green) and mCherry-CAAX (red) expressing cells. Images are single x-y plane. A GFP-Tubulin-expressing cell undergoes division with an mCherry-CAAX-expressing cell inside. Time is shown as hours:minutes:seconds.milliseconds.

Confocal timelapse analysis of MCF10A cell-in-cell structure between GFP-Tubulin (green) expressing cells. Images are 3D reconstruction. A GFP-Tubulin-expressing cell undergoes division with another GFP-Tubulin -expressing cell inside. Time is shown as hours:minutes:seconds.milliseconds.

Confocal timelapse analysis of MCF10A cell-in-cell structure between GFP-Tubulin (green) expressing cells. Images are single x-y plane. A GFP-Tubulin-expressing cell undergoes division with another GFP-Tubulin -expressing cell inside. Time is shown as hours:minutes:seconds.milliseconds.

Times are shown as minutes (min). White arrow indicates asymmetric cleavage furrow that moves around internalized cell.

Single cells and cell-in-cell structures quantified as in Figure 1. Individual patient effusion samples are labeled E1-E8. Samples with a significant difference in multinucleation between cell-in-cell and single cells are shown with asterisks. p-values (Fisher Exact test): E1 *p=.005 (Single cell, n=40; Cell-in-cell, n=20); E2 **p=.05 (Single cell, n=200; Cell-in-cell, n=200); E3 p=.62 (Single cell, n=100; Cell-in-cell, n=100); E4 ***p=.001 (Single cell, n=100; Cell-in-cell, n=100); E5 ****p=.02 (Single cell, n=43; Cell-in-cell, n=22); E6 p=.3 (Single cell, n=59; Cell-in-cell, n=25); E7 *****p=.02 (Single cell, n=100; Cell-in-cell, n=44); E8 p=.36 (Single cell, n=59; Cell-in-cell, n=42). Images show Papanicolaou stained binucleate (bottom) or mononucleated (top) cell-in-cell structures from patient fluids; arrows indicate nuclei in outer cells.

All images are from timelapse of HEK293 cells expressing GFP-Tubulin. Confocal x-y planes are shown. (a) Host cell of cell-in-cell structure divides with symmetric cleavage furrow (arrows); internalized cell is away from furrow and division is successful. (b) Internalized cell blocks the cleavage plane and the furrow is asymmetric (arrow); division is successful. See Movie S9. (c) Internalized cell blocks the cleavage plane and the furrow is asymmetric (arrow); division fails producing binucleated cell (arrows, right image).

DIC and fluorescence timelapse images of MCF10A cells expressing E-cadherin-GFP (green) and H2B-mCherry (red), cultured under anchorage-independent conditions in soft agar. (a) Failed division of completed cell-in-cell structure. By 380 minutes, cell-in-cell structure completed formation; host cell attempted division and failed cytokinesis, forming a binucleate cell. Note asymmetric cleavage furrow in middle two images. See Movie S11. (b) Partial cell-in-cell structure exhibits cytokinesis failure. Arrows indicate one side of E-cadherin mediated cell-cell junction, that did not completely enwrap internalizing cell prior to host cell attempting division and failing cytokinesis. Note asymmetric cleavage furrow at 140 minutes. See Movie S12. Graph depicts percent failed host cell divisions in soft agar for complete (n=7) or partial (n=33) cell-in-cell structures.

All image panels show immunofluorescence staining of pMLC-S19 on cell divisions tracked by timelapse microscopy. (a) Representative asymmetric furrow. Left images are from timelapse analysis. Times shown as minutes (min); GFP-Tubulin shown in green; arrows indicate asymmetric furrow. Right confocal image shows pMLC staining (IF) in red; arrow indicates asymmetric contractile ring. Note that two cells are internalized inside of the host. Inset is 3D reconstruction of pMLC-S19 staining shown as grayscale and angled to visualize contractile ring. (b) Representative asymmetric furrow with pMLC on the vacuole. Left images are from timelapse analysis. Times shown as minutes (min); GFP-Tubulin shown in green; arrows indicate asymmetric furrow. Right confocal image shows pMLC staining (IF) in red; large arrow indicates asymmetric contractile ring, small arrow indicates pMLC staining on the vacuole. Inset is 3D reconstruction of pMLC-S19 staining shown as grayscale and angled to visualize contractile ring; note that pMLC staining can be seen on both the cell membrane and vacuole membrane. In total, 6/13 (46%) asymmetric divisions displayed pMLC staining proximal to the vacuole in addition to the cell cortex. (c) Representative symmetric furrow. Left images are from timelapse analysis. Times shown as minutes (min); GFP-Tubulin shown in green; arrows indicate symmetric furrow. Right confocal image shows pMLC staining (IF) in red; arrows indicate symmetric contractile ring. Top inset is 3D reconstruction of pMLC-S19 staining shown as grayscale and angled to visualize contractile ring; note that pMLC staining can be seen as a complete ring structure. Bottom inset shows internalized cells in different z-plane; arrows indicate position of cleavage furrow for orientation. All scale bars = 10μM.

Quantification of cell-in-cell structures in 86 human invasive breast tumors, distributed by tumor grade. Grade 1, n=20; Grade 2, n=19; Grade 3, n=47. Individual tumors are represented by single data points; bars represent means. Grade 3 tumors exhibit significantly more cell-in-cell structures than grade 1 (p<.001; ANOVA).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (J.S.B.), NIH GM66492 (R.W.K.), and a grant from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center at M.S.K.C.C. (M.O.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions. M.K., N.B.J., Q.S., G.N., N.H., E.Y., M.O. designed and performed experiments, A.L.R. provided human tumours, J.B., E.S.C., R.W.K. S.J.S., M.O. supervised the research, M.O., J.B. prepared the manuscript.

References

- 1.Rajagopalan H, Lengauer C. Aneuploidy and cancer. Nature. 2004;432:338–341. doi: 10.1038/nature03099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinto AE, Andre S, Pereira T, Silva G, Soares J. DNA flow cytometry but not telomerase activity as predictor of disease-free survival in pT1-2/N0/G2 breast cancer. Pathobiology. 2006;73:63–70. doi: 10.1159/000094490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araujo SE, Bernardo WM, Habr-Gama A, Kiss DR, Cecconello I. DNA ploidy status and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of published data. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1800–1810. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suehiro Y, et al. Aneuploidy Predicts Outcome in Patients with Endometrial Carcinoma and Is Related to Lack of CDH13 Hypermethylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3354–3361. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Susini T, et al. Ten-year results of a prospective study on the prognostic role of ploidy in endometrial carcinoma: dNA aneuploidy identifies high-risk cases among the so-called ‘low-risk’ patients with well and moderately differentiated tumors. Cancer. 2007;109:882–890. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinto AE, Monteiro P, Silva G, Ayres JV, Soares J. Prognostic biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma: relevance of DNA ploidy in predicting disease-related survival. Int J Biol Markers. 2005;20:249–256. doi: 10.1177/172460080502000408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganem NJ, Godinho SA, Pellman D. A mechanism linking extra centrosomes to chromosomal instability. Nature. 2009;460:278–282. doi: 10.1038/nature08136. nature08136 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganem NJ, Storchova Z, Pellman D. Tetraploidy, aneuploidy and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boveri T. The Origin of Malignant Tumors. Williams and Wilkins; 1929. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujiwara T, et al. Cytokinesis failure generating tetraploids promotes tumorigenesis in p53-null cells. Nature. 2005;437:1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/nature04217. nature04217 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadler Y, et al. Expression of Aurora A (but not Aurora B) is predictive of survival in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4455–4462. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5268. 14/14/4455 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, et al. Overexpression of aurora kinase A in mouse mammary epithelium induces genetic instability preceding mammary tumor formation. Oncogene. 2006;25:7148–7158. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casenghi M, et al. p53-independent apoptosis and p53-dependent block of DNA rereplication following mitotic spindle inhibition in human cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999;250:339–350. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuiki H, et al. Mechanism of hyperploid cell formation induced by microtubule inhibiting drug in glioma cell lines. Oncogene. 2001;20:420–429. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minn AJ, Boise LH, Thompson CB. Expression of Bcl-xL and loss of p53 can cooperate to overcome a cell cycle checkpoint induced by mitotic spindle damage. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2621–2631. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larkins BA, et al. Investigating the hows and whys of DNA endoreduplication. J Exp Bot. 2001;52:183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerbel RS, Lagarde AE, Dennis JW, Donaghue TP. Spontaneous fusion in vivo between normal host and tumor cells: possible contribution to tumor progression and metastasis studied with a lectin-resistant mutant tumor. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:523–538. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duelli D, Lazebnik Y. Cell fusion: a hidden enemy? Cancer Cell. 2003;3:445–448. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duelli DM, Hearn S, Myers MP, Lazebnik Y. A primate virus generates transformed human cells by fusion. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:493–503. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overholtzer M, et al. A nonapoptotic cell death process, entosis, that occurs by cell-in-cell invasion. Cell. 2007;131:966–979. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.040. S0092-8674(07)01394-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overholtzer M, Brugge JS. The cell biology of cell-in-cell structures. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:796–809. doi: 10.1038/nrm2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazzone M, et al. Dose-dependent induction of distinct phenotypic responses to Notch pathway activation in mammary epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5012–5017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000896107. 1000896107 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerrero AA, et al. Centromere-localized breaks indicate the generation of DNA damage by the mitotic spindle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4159–4164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912143106. 0912143106 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong C, Stearns T. Mammalian cells lack checkpoints for tetraploidy, aberrant centrosome number, and cytokinesis failure. BMC Cell Biol. 2005;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uetake Y, Sluder G. Cell cycle progression after cleavage failure: mammalian somatic cells do not possess a “tetraploidy checkpoint”. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:609–615. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silkworth WT, Nardi IK, Scholl LM, Cimini D. Multipolar spindle pole coalescence is a major source of kinetochore mis-attachment and chromosome mis-segregation in cancer cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen CG, Jensen LC, Rieder CL, Cole RW, Ault JG. Long crocidolite asbestos fibers cause polyploidy by sterically blocking cytokinesis. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2013–2021. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.9.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rappaport R. Experiments concerning the cleavage stimulus in sand dollar eggs. J Exp Zool. 1961;148:81–89. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401480107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abodief WT, Dey P, Al-Hattab O. Cell cannibalism in ductal carcinoma of breast. Cytopathology. 2006;17:304–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2006.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lugini L, et al. Cannibalism of live lymphocytes by human metastatic but not primary melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3629–3638. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cibas E. In: Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. Cibas ES, Ducatman BS, editors. Elsevier; 2003. pp. 119–144. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressing H2B-GFP (green). Time is shown as minutes (min). White arrows indicate host cell nuclei before and after cytokinesis failure.

Confocal timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expessing GFP-Tubulin (green). Images are single x-y plane. Time is shown as minutes (min). Note culture was fixed immediately after timelapse (at 14 min) and processed for immunofluorescence for pMLC-S19 and α-Tubulin.

Confocal timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressig E-cadherin-GFP (green) and H2B-mCherry (red). Time is shown as minutes (min). Images are single x-y plane. Note this host cell expresses a high background of E-cadherin-GFP. After cell-in-cell structure completes formation, host cell attempts division with asymmetric cleavage furrow and fails cytokinesis.

Confocal timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressig E-cadherin-GFP (green) and H2B-mCherry (red). Time is shown as minutes (min). Images are single x-y plane. Note cell-cell junction marked by E-cadherin plaques, and inner cell extending out of host cell during the attempted host cell division. Note host cell has asymmetric cleavage furrow and fails cytokinesis.

Timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expessing H2B-GFP (green). Time is shown as minutes (hours:minutes:seconds). Culture was fixed immediately after timelapse (at 48 hours) and processed for 2-colour FISH analysis to quantify the copy number of chromosomes 8 and 12.

Timelapse analysis of 16HBE cells expressing H2B-mCherry (red). Time is shown as minutes (min).

Timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressing GFP-Tubulin (green). Time is shown as minutes (min). Left frame is phase contrast, right frame is GFP fluorescence.

Timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressing GFP-Tubulin (green). Time is shown as minutes (min). Left frame is phase contrast, right frame is GFP fluorescence.

Timelapse analysis of MCF10A cells expressing GFP-Tubulin (green). Time is shown as minutes (min). Left frame is DIC, right frame is GFP fluorescence.

Confocal timelapse analysis of mixed MCF10A cell-in-cell structure with GFP-Tubulin (green) and mCherry-CAAX (red) expressing cells. Images are single x-y plane. A GFP-Tubulin-expressing cell undergoes division with an mCherry-CAAX-expressing cell inside. Time is shown as hours:minutes:seconds.milliseconds.

Confocal timelapse analysis of MCF10A cell-in-cell structure between GFP-Tubulin (green) expressing cells. Images are 3D reconstruction. A GFP-Tubulin-expressing cell undergoes division with another GFP-Tubulin -expressing cell inside. Time is shown as hours:minutes:seconds.milliseconds.

Confocal timelapse analysis of MCF10A cell-in-cell structure between GFP-Tubulin (green) expressing cells. Images are single x-y plane. A GFP-Tubulin-expressing cell undergoes division with another GFP-Tubulin -expressing cell inside. Time is shown as hours:minutes:seconds.milliseconds.

Times are shown as minutes (min). White arrow indicates asymmetric cleavage furrow that moves around internalized cell.

Single cells and cell-in-cell structures quantified as in Figure 1. Individual patient effusion samples are labeled E1-E8. Samples with a significant difference in multinucleation between cell-in-cell and single cells are shown with asterisks. p-values (Fisher Exact test): E1 *p=.005 (Single cell, n=40; Cell-in-cell, n=20); E2 **p=.05 (Single cell, n=200; Cell-in-cell, n=200); E3 p=.62 (Single cell, n=100; Cell-in-cell, n=100); E4 ***p=.001 (Single cell, n=100; Cell-in-cell, n=100); E5 ****p=.02 (Single cell, n=43; Cell-in-cell, n=22); E6 p=.3 (Single cell, n=59; Cell-in-cell, n=25); E7 *****p=.02 (Single cell, n=100; Cell-in-cell, n=44); E8 p=.36 (Single cell, n=59; Cell-in-cell, n=42). Images show Papanicolaou stained binucleate (bottom) or mononucleated (top) cell-in-cell structures from patient fluids; arrows indicate nuclei in outer cells.

All images are from timelapse of HEK293 cells expressing GFP-Tubulin. Confocal x-y planes are shown. (a) Host cell of cell-in-cell structure divides with symmetric cleavage furrow (arrows); internalized cell is away from furrow and division is successful. (b) Internalized cell blocks the cleavage plane and the furrow is asymmetric (arrow); division is successful. See Movie S9. (c) Internalized cell blocks the cleavage plane and the furrow is asymmetric (arrow); division fails producing binucleated cell (arrows, right image).

DIC and fluorescence timelapse images of MCF10A cells expressing E-cadherin-GFP (green) and H2B-mCherry (red), cultured under anchorage-independent conditions in soft agar. (a) Failed division of completed cell-in-cell structure. By 380 minutes, cell-in-cell structure completed formation; host cell attempted division and failed cytokinesis, forming a binucleate cell. Note asymmetric cleavage furrow in middle two images. See Movie S11. (b) Partial cell-in-cell structure exhibits cytokinesis failure. Arrows indicate one side of E-cadherin mediated cell-cell junction, that did not completely enwrap internalizing cell prior to host cell attempting division and failing cytokinesis. Note asymmetric cleavage furrow at 140 minutes. See Movie S12. Graph depicts percent failed host cell divisions in soft agar for complete (n=7) or partial (n=33) cell-in-cell structures.

All image panels show immunofluorescence staining of pMLC-S19 on cell divisions tracked by timelapse microscopy. (a) Representative asymmetric furrow. Left images are from timelapse analysis. Times shown as minutes (min); GFP-Tubulin shown in green; arrows indicate asymmetric furrow. Right confocal image shows pMLC staining (IF) in red; arrow indicates asymmetric contractile ring. Note that two cells are internalized inside of the host. Inset is 3D reconstruction of pMLC-S19 staining shown as grayscale and angled to visualize contractile ring. (b) Representative asymmetric furrow with pMLC on the vacuole. Left images are from timelapse analysis. Times shown as minutes (min); GFP-Tubulin shown in green; arrows indicate asymmetric furrow. Right confocal image shows pMLC staining (IF) in red; large arrow indicates asymmetric contractile ring, small arrow indicates pMLC staining on the vacuole. Inset is 3D reconstruction of pMLC-S19 staining shown as grayscale and angled to visualize contractile ring; note that pMLC staining can be seen on both the cell membrane and vacuole membrane. In total, 6/13 (46%) asymmetric divisions displayed pMLC staining proximal to the vacuole in addition to the cell cortex. (c) Representative symmetric furrow. Left images are from timelapse analysis. Times shown as minutes (min); GFP-Tubulin shown in green; arrows indicate symmetric furrow. Right confocal image shows pMLC staining (IF) in red; arrows indicate symmetric contractile ring. Top inset is 3D reconstruction of pMLC-S19 staining shown as grayscale and angled to visualize contractile ring; note that pMLC staining can be seen as a complete ring structure. Bottom inset shows internalized cells in different z-plane; arrows indicate position of cleavage furrow for orientation. All scale bars = 10μM.

Quantification of cell-in-cell structures in 86 human invasive breast tumors, distributed by tumor grade. Grade 1, n=20; Grade 2, n=19; Grade 3, n=47. Individual tumors are represented by single data points; bars represent means. Grade 3 tumors exhibit significantly more cell-in-cell structures than grade 1 (p<.001; ANOVA).