Abstract

Objective

To determine which factors parents consider to be most important when pursuing elective circumcision procedures in newborn male children.

Design

Prospective survey.

Setting

Saskatoon, Sask.

Participants

A total of 230 participants attending prenatal classes in the Saskatoon Health Region over a 3-month period.

Main outcome measures

Parents' plans to pursue circumcision, personal and family circumcision status, and factors influencing parents' decision making on the subject of elective circumcision.

Results

The reasons that parents most often gave for supporting male circumcision were hygiene (61.9%), prevention of infection or cancer (44.8%), and the father being circumcised (40.9%). The reasons most commonly reported by parents for not supporting circumcision were it not being medically necessary (32.0%), the father being uncircumcised (18.8%), and concerns about bleeding or infection (15.5%). Of all parents responding who were expecting children, 56.4% indicated they would consider pursuing elective circumcision if they had a son; 24.3% said they would not. In instances in which the father of the expected baby was circumcised, 81.9% of respondents were in favour of pursuing elective circumcision. When the father of the expected child was not circumcised, 14.9% were in favour of pursuing elective circumcision. Regression analysis showed that the relationship between the circumcision status of the father and support of elective circumcision was statistically significant (P < .001). Among couples in which the father was circumcised, 82.2% stated that circumcision by an experienced medical practitioner was a safe procedure for all boys, in contrast to 64.1% of couples in which the father of the expected child was not circumcised. When the expecting father was circumcised, no one responded that circumcision was an unsafe procedure, compared with 7.8% when the expecting father was not circumcised (P = .003).

Conclusion

Despite new medical information and updated stances from various medical associations, newborn male circumcision rates continue to be heavily influenced by the circumcision status of the child's father.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer les facteurs qui, selon les parents, sont les plus importants pour demander une circoncision élective pour leur nouveau-né mâle.

Type d'étude

Enquête prospective.

Contexte

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

Participants

Un total de 230 personnes suivant des cours prénataux dans la région sanitaire de Saskatoon, sur une période de 3 mois.

Principaux paramètres à l'étude

Intention des parents de demander une circoncision, présence de circoncision chez le père et dans la famille, et facteurs influençant la décision des parents concernant la circoncision élective.

Résultats

Les raisons les plus fréquemment invoquées par les parents pour souhaiter la circoncision mâle étaient l'hygiène (61,9 %), la prévention des infections ou du cancer (44,8 %) et le fait que le père était circoncis (40,9 %). Les raisons le plus souvent invoquées pour refuser la circoncision étaient que ce n'était pas médicalement requis (32,0 %), que le père n'était pas circoncis (18,8 %) et qu'on craignait des saignements ou infections (15,5 %). Parmi tous les parents qui attendaient des enfants, 56,4 % indiquaient qu'ils penseraient à demander une circoncision s'ils avaient un fils alors que 24,3 % disaient qu'ils ne le feraient pas. Lorsque le père du bébé à venir était circoncis, 81,9 % des répondants étaient en faveur de recourir à une circoncision optionnelle, mais si le père ne l'était pas, 14,9 % étaient favorables à en demander une. L'analyse de régression a révélé une relation statistiquement significative entre la présence de circoncision chez le père et le fait d'être favorable à une circoncision optionnelle (P < ,001). Parmi les couples dont le mari était circoncis, 82,2 % déclaraient qu'une circoncision effectuée par un médecin expérimenté était une intervention sécuritaire pour tous les garçons, par rapport à 64,1 % des couples dont le père n'était pas circoncis. Aucun des pères circoncis en attente d'un bébé n'a répondu que la circoncision n'était pas sécuritaire, contre 7,8 % de ceux qui n'étaient pas circoncis (P < ,003).

Conclusion

En dépit des nouvelles données médicales et des déclarations récentes de diverses associations médicales, les taux de circoncision des nouveau-nés mâles continuent d'être fortement influencés par le fait que le

Elective newborn circumcision has long been a topic of debate and continues to remain so today.1,2 Recent research conducted in Africa has suggested that risk of HIV transmission could be lowered by male circumcision.3 Some studies on sexual health have shown negligible benefits in circumcised males in regard to sexual health and transmission of sexually transmitted infections (excluding HIV),4 while others report statistically significant (P < .05) higher rates of sexually transmitted infections in uncircumcised men.5 Despite the changing evidence regarding the risks and benefits of circumcision, rates of circumcision continue to fluctuate in different parts of the world. In Australia rates have declined dramatically, to only 32% among Australian men younger than 20 years of age.6 In the United States, data have shown that rates are actually increasing, to 61% of men.7 In Canada, the most recent data show our current circumcision rate to be 31.9% nationwide.8 In Saskatchewan the rate is slightly higher, at 35.6%.8

Just as the prevalence of male circumcision varies around the world, the reasons for circumcision are equally diverse.9,10 Even physicians are guided by personal influences when determining a stance on circumcision. One study showed that circumcised physicians were more likely to support circumcision, and uncircumcised physicians were more likely to be against circumcision.11 Parents might be guided by their physicians' opinions, their own religious views, the father's circumcision status, and, more recently, by financial considerations. In 1996, the Ministry of Health in Saskatchewan made elective circumcision an uninsured procedure, meaning that parents must pay to have the procedure done.

A recent study of parents in the United States showed that 86% of respondents supported elective circumcision of newborns, and this support did not vary after parents were given literature on the subject of HIV and human papillomavirus transmission.10 The Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) continues to recommend against routine newborn circumcisions, although an updated position statement has not been released since 1996. In June 2006, the British Medical Association updated its stance on the issue, taking a neutral position, acknowledging the “spectrum of views within the [British Medical Association's] membership about whether non-therapeutic male circumcision is a beneficial, neutral or harmful procedure or whether it is superfluous.”12 The question remains: What is the main determining factor for parents supporting circumcision? Are parents making decisions based on personal research or rumours about circumcision's benefits and risks? Are the determining factors dependent more on personal factors or the male parent's circumcision status?

Survey design and participants

In 2011, 230 participants were identified using registration in Saskatoon Health Region prenatal classes in Saskatchewan. There was no pre-existing questionnaire available, so a new unvalidated questionnaire was specifically designed for this study and handed out to participants at evening prenatal classes. Although it was not pilot-tested, this questionnaire was designed based on a similar questionnaire used to survey physician support of circumcision11 and an Australian study evaluating the factors affecting circumcision.13 Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Saskatchewan and the Saskatoon Health Region before study administration. The study participants were asked to complete the survey and return it to a sealed dropbox. Participants were instructed that if they did not wish to participate they should return the blank questionnaire to the dropbox. The study took place from June 13 to August 2, 2011, and spanned a total of 9 prenatal classes. The participants in the survey were limited to parents attending prenatal classes. The parents completed the surveys on the first day of the prenatal classes, before subsequent class teaching that included information about circumcision. The survey was purposefully administered before prenatal teaching, as there were many different prenatal classes offered throughout the city and this avoided any bias that these particular prenatal classes might have had on parents' decisions. All parents who registered for and attended the prenatal classes were invited to participate in the survey. Class participants who were not to be the parent or primary caregiver of the expected child were excluded from the survey.

The questionnaire was designed by the principle author (C.R.). It contained participant demographic questions (sex, age), information about the parents' upcoming pregnancy (sex of baby expected, plans for circumcision), circumcision status (own, partner's, and sons'), opinions regarding circumcision, and personal factors that could influence a parent's position on elective circumcision.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS 18 to enter and analyze the data. Categorical data were summarized into frequencies and percentages. Continuous data were analyzed using measures of central location. Hypothesis testing was investigated using the Pearson χ2 statistic for independence of association between 2 independent samples. The null hypothesis was that there was no association between circumcision status, demographic characteristics, or the expected sex of the baby and whether parents supported elective circumcisions (ie, these are independent). The alternative hypothesis was that these factors are not independent. Two-sided probability values (P values) were compared against an α = .01 level of significance as the hypothesis rejection criterion. The degrees of freedom and the Pearson χ2 statistic were determined for each multiple 2-sample test.

RESULTS

The response rate was 78.7% (181 of 230). The average age of respondents was 30.3 years (range 16 to 69, median 29.5) and 58.6% (106 of 181) of respondents were female. The sex of the baby expected by parents was not known by most respondents (62.4%, 111 of 178).

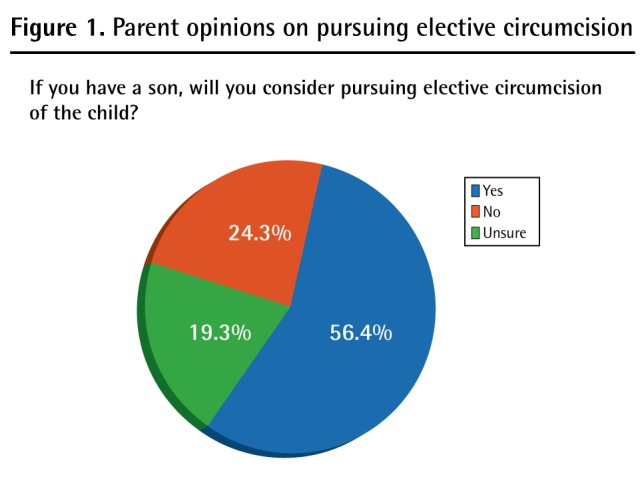

Of those who answered the question on their opinions of male circumcision performed by an experienced medical practitioner, 90.8% (158 of 174) reported that they believed circumcision to be a safe procedure for either all (74.7%, 130 of 174) or some (16.1%, 28 of 174) boys. Only 2.9% (5 of 174) reported male circumcision to be an unsafe procedure. Of the parents who responded, 56.4% (102 of 181) would consider pursuing elective circumcision, 24.3% (44 of 181) would not, and 19.3% (35 of 181) indicated that they were unsure (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Parent opinions on pursuing elective circumcision.

Of the reasons that parents gave for supporting circumcision of their children, hygiene (61.9%, 112 of 181), prevention of infection or cancer (44.8%, 81 of 181), and the father being circumcised (40.9%, 74 of 181) were the most often cited reasons (Table 1). When asked what was the single most important factor in supporting male circumcision, hygiene was most commonly (51.0%, 73 of 143) reported (Table 2).

Table 1. Three most important factors parents considered when deciding whether to circumcise their sons.

| FACTORS | PROPORTION OF PARENTS |

|---|---|

| Supporting circumcision | |

|

61.9 |

|

44.8 |

|

40.9 |

| Not supporting circumcision | |

|

32.0 |

|

18.8 |

|

15.5 |

Table 2.

Single most important factor in supporting circumcision, as indicated by parents: N = 143.

| FACTORS | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Hygiene | 73 (51.0) |

| Prevention of infection or cancer | 22 (15.4) |

| Father circumcised | 12 (8.4) |

| Personal preference | 11 (7.7) |

| Religion | 9 (6.3) |

| Doctor advises it | 5 (3.5) |

| Looks better | 3 (2.1) |

| It just seems right | 3 (2.1) |

| To look like other boys | 2 (1.4) |

| Other sons are circumcised | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 3 (2.1) |

When respondents were asked what factors were important in their not supporting the circumcision of their children, it not being medically necessary (32.0%, 58 of 181), the father being uncircumcised (18.8%, 34 of 181), and concerns about bleeding or infection (15.5%, 28 of 181) were the most common answers (Table 1). When asked about the single most important factor in their not supporting male circumcision, it not being medically necessary was most commonly (54.3%, 50 of 92) reported (Table 3).

Table 3.

Single most important factor in not supporting circumcision, as indicated by parents: N = 92.

| FACTORS | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Not medically necessary | 50 (54.3) |

| Concerned with infection or bleeding | 13 (14.1) |

| Father is not circumcised | 9 (9.8) |

| Hurts too much | 9 (9.8) |

| Baby has no input in decision | 6 (6.5) |

| Looks better | 5 (5.4) |

| Other sons are not circumcised | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) |

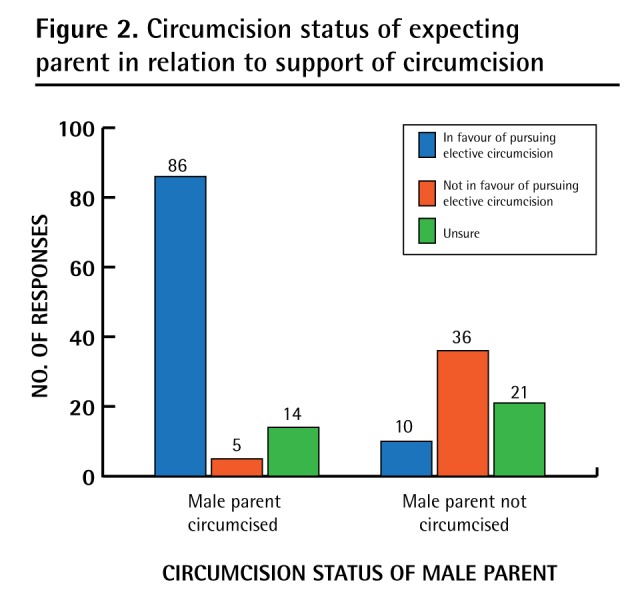

When asked about the circumcision status of the father, most respondents (61.0%, 105 of 172) reported that the father had been circumcised, whether at birth, in childhood, or in adulthood (Table 4). Among respondents (male and female), if the father of the expected baby was circumcised, 81.9% (86 of 105) were in favour of pursuing elective circumcision (Figure 2). When the father of the expected child was not circumcised, 14.9% (10 of 67) were in favour of pursuing elective circumcision. The relationship between circumcision status of the father and support of elective circumcision was statistically significant (P < .001, = 80.54) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Circumcision status of the father of the expected child: N = 181.

| FATHER'S CIRCUMCISION STATUS | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Circumcised at birth | 95 (52.5) |

| Not circumcised | 67 (37.0) |

| Circumcised in childhood | 9 (5.0) |

| Circumcised in adulthood | 1 (0.6) |

| No response | 9 (5.0) |

Figure 2. Circumcision status of expecting parent in relation to support of circumcision.

Table 5. Support of circumcision relative to father's circumcision status:Participants were asked, “If you have a son, will you consider pursuing elective circumcision of the child?”.

| FATHER'S CIRCUMCISION STATUS* | CONSIDER CIRCUMCISION† | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| YES | NO | UNSURE | |

| Uncircumcised father (N = 105) | 86 | 5 | 14 |

| Circumcised father (N = 67) | 10 | 36 | 21 |

A total of 9 of the 181 respondents did not disclose circumcision status.

The relationship between circumcision status of the father and support of elective circumcision was statistically significant (P < .001, = 80.54).

When the father was circumcised, 82.2% (83 of 101) stated that circumcision by an experienced medical practitioner was a safe procedure for all boys. When the father of the expected child was not circumcised, 64.1% (41 of 64) of parents stated that it was a safe procedure for all boys. If the father was circumcised, no one (0 of 101) responded that circumcision was an unsafe procedure. If the father was not circumcised, 7.8% (5 of 64) reported circumcision to be an unsafe procedure. This difference was also statistically significant (P = .003, = 13.84).

DISCUSSION

The results of the survey suggest that the personal circumcision status of the male parent is an extremely important factor in the decision to pursue elective circumcision, regardless of the reasons that parents state. Other influencing factors in supporting circumcision included hygiene and prevention of infection or cancer. Commonly cited factors for parents not supporting circumcision included the procedure being medically unnecessary, and concerns about bleeding and infection. Although circumcision status of the father was often mentioned as a reason, it was not usually listed as the most important factor in coming to a decision about circumcision. Although the survey did not explicitly ask about religious beliefs, religion was listed among the options for reasons to support circumcision and was not chosen very often.

Similarly, circumcision status of the father seemed to affect both parents' opinions about elective circumcision. Families in which the father was circumcised were overwhelmingly more likely to support circumcision as a safe procedure for all boys, while the only respondents to state that circumcision was an unsafe procedure were families in which the father was not circumcised.

Also interesting was the fact that so many parents were in favour of pursuing circumcision. This was well above the national and provincial average of circumcisions performed; further studies might be useful to see what factors (eg, cost, socioeconomic status, prenatal teaching, procedural roadblocks, availability of physicians performing circumcisions) caused such a discrepancy between the number of parents wanting to pursue circumcision and the actual number that goes through with the procedure. Because this survey was administered before the prenatal classes, more research is needed, perhaps in a follow-up format, to determine what parents have chosen and why.

Limitations

The survey was conducted at prenatal classes; therefore, the survey captured parents' opinions before the baby was born. The fact that so many respondents were in favour of pursuing elective circumcision might be biased, as some might not be aware of the definite procedures and costs involved in pursuing circumcision. In addition, the circumcision teaching done at the prenatal classes might also influence parents' decisions. Last, parents' feelings might change about circumcision after the baby is delivered.

We took care to survey both male and female participants attending classes and to allow for single, homosexual, or untraditional family structures. In addition, the survey was conducted during the first prenatal class, before an information session by the health region on circumcision, in order to avoid influence from any bias that might have existed in the presentation.

Conclusion

These findings further confirm that circumcision is a controversial subject, with multiple factors affecting parents' decisions about whether or not to circumcise their children. Our results suggest that although multiple considerations play a role in parents choosing or not choosing circumcision, the single most important factor in parents' initial opinions about circumcision seems to be the circumcision status of the father, rather than research or rumour.

EDITOR'S KEY POINTS

Circumcision is a controversial subject, with multiple factors affecting parents' decisions about whether or not to circumcise their sons. This study sought to understand what factors parents considered to be important when making decisions about circumcising their children

The results suggest that, although multiple factors affect parents' decisions to circumcise their children, and although they most commonly list hygiene as the single most important factor in their decision, it seems that the circumcision status of the father is in fact the most important influence.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÈDACTEUR

La circoncision est un sujet controversé et plusieurs facteurs peuvent influencer la décision des parents de faire ou de ne pas faire circoncire leurs garçons. Cette étude voulait connaître les facteurs que les parents jugent importants lorsqu'ils doivent prendre une décision à ce sujet.

Les résultats suggèrent que même si de nombreux facteurs affectent la décision des parents concernant la circoncision de leurs enfants et même si les participants mentionnaient que l'hygiène est le facteur le plus important dans leur décision, en réalité, c'est la présence d'une circoncision chez le père qui a le plus d'influence.

Footnotes

Contributors: Mr Rediger was the principle investigator in this study and the main author of the manuscript. Dr Muller contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests: None declared

This article has been peer reviewed. Can Fam Physician 2013;59:e110-5

References

- 1.Arie S. Circumcision:divided we fall. BMJ 2010;341:c4266 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.c4266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preiser G. Circumcision—the debates goes on [multiple letters]. Pediatrics 2000;105(3 Pt 1):681-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hargreave T. Male circumcision: towards a World Health Organisation normative practice in resource limited settings. Asian J Androl 2010;12(5):628-38 Epub 2010 Jul 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferris JA, Richters J, Pitts MK, Shelley JM, Simpson JM, Ryall R, et al. Circumcision in Australia: further evidence on its effects on sexual health and wellbeing. Aust N Z J Public Health 2010;34(2):160-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Circumcision status and risk of sexually transmitted infection in young adult males: an analysis of a longitudinal birth cohort. Pediatrics 2006;118(5):1971-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris BJ. Circumcision in Australia: prevalence and effects on sexual health. Int J STD AIDS 2007;18(1):69-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson CP, Dunn R, Wan J, Wei JT. The increasing incidence of newborn circumcision: data from the nationwide inpatient sample. J Urol 2005;173(3):978-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Statistics Canada [website] Maternity experiences survey. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2007. Available from: www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5019&lang=en&db=imdb&adm=8&dis=2 Accessed 013 Jan 18 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Provencio-Vasquez E, Rodriguez A. Circumcision revisited. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2009;14(4):295-7 DOI: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang ML, Macklin EA, Tracy E, Nadel H, Catlin EA. Updated parental viewpoints on male neonatal circumcision in the United States. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2010;492:130-6 DOI: 10.1177/0009922809346569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller AJ. To cut or not to cut? Personal factors influence primary care physicians' position on elective newborn circumcision. J Mens Health 2010;7(3):227-32 [Google Scholar]

- 12.British Medical Association The law and ethics of male circumcision—guidance for doctors. J Med Ethics 2004;30(3):259-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu B, Goldman H. Newborn circumcision in Victoria, Australia: reasons and parental attitudes. ANZ J Surg 2008;78(11):1019-22 DOI: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]