Abstract

Background

Tissue injury leads to release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that may drive a sterile inflammatory response; however, the role of extracellular histones after traumatic injury remains unexplored. We hypothesized that extracellular histones would be increased and associated with poor outcomes after traumatic injury.

Methods

In this prognostic study, plasma was prospectively collected from 132 critically injured trauma patients on arrival and 6h after admission to an urban level I trauma ICU. Circulating extracellular histone levels and plasma clotting factors were assayed, and linked to resuscitation and outcomes data.

Results

Of 132 patients, histone levels were elevated to a median of 14.0 absorbance units (AU) on arrival, declining to 6.4 AU by 6h. Patients with elevated admission histone levels had higher injury severity score, lower admission GCS, more days of mechanical ventilation, and higher incidences of multiorgan failure, acute lung injury, and mortality (all p ≤0.05). Histone levels correlated with prolonged INR and PTT, fibrinolytic markers D-dimer and tissue-type plasminogen activator, and anticoagulants tissue factor pathway inhibitor and activated Protein C (aPC; all p < 0.03). Increasing histone level from admission to 6h was a multivariate predictor of mortality (hazard ratio 1.005, p=0.013). When aPC level trends were included, the impact of histone level increase on mortality was abrogated (p=0.206) by a protective effect of increasing aPC levels (hazard ratio 0.900, p=0.020).

Conclusions

Extracellular histones are elevated in response to traumatic injury, and correlate with fibrinolysis and activation of anticoagulants. An increase in histone levels from admission to 6h is predictive of mortality, representing evidence of ongoing release of intracellular antigens similar to that seen in sepsis. Concomitant elevation of aPC abrogates this effect, suggesting a possible role for aPC in mitigating the sterile inflammatory response after trauma through the proteolysis of circulating histones.

Keywords: Trauma, DAMPs, histones, Protein C

Background

Intuitive parallels exist between the systemic inflammatory responses seen in sepsis, ischemia-reperfusion, and trauma, and there is growing recognition of an underlying crosstalk between systemic inflammation and the coagulation system that unites all of these phenomena.1 As a canonical example, the tissue injury and end-organ damage seen in sepsis is initiated by a pathogenic stimulus, but largely mediated by cytokine and leukocyte signaling. Recent work in models of sepsis has identified circulating extracellular histones, either derived from apoptotic cells2 or secreted and incorporated into neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs),3 as major mediators of endothelial apoptosis, organ failure, and death during sepsis.4 Furthermore, direct intravascular injection of histones leads to macro- and microvascular thrombosis,4 and histone-containing NETs have been shown to promote platelet aggregation and thrombus formation5, 6. Both the proinflammatory and procoagulant effects of extracellular histones have recently been linked to signaling via TLR2 and TLR4.6, 7

A countervailing role in the crosstalk between inflammation and coagulation is held by the protein C system.8 Activated protein C (aPC) mediates direct endothelial cytoprotection during ischemia,9 and reduces cytokine elaboration in sepsis.10 Furthermore, aPC leads to anticoagulation via cleavage of activated Factors Va and VIIIa, and to derepression of fibrinolysis via consumption of plasminogen activator-inhibitor-1.11 Interestingly, aPC has also been shown to proteolytically cleave extracellular histones, mitigating the lethality of histone-induced systemic inflammatory response in animal models.4

Early theories that bacterial translocation from ischemic gut caused a sepsis-like state after traumatic injury have been challenged by the discovery that circulating mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) mediate a sterile inflammatory response to trauma as a direct result of tissue injury by a pathogen.12 Extracellular histone release may work through a similar mechanism in the inflammatory and prothrombotic milieu after trauma as has been previously described in sepsis. Our group and others have previously characterized the anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects of activation of the Protein C system in response to tissue injury and shock.13, 14 In order to investigate the inflammatory and coagulation crosstalk mediated by extracellular histones and the Protein C system in traumatic injury, we investigated levels of circulating extracellular histones in critically-injured trauma patients, hypothesizing that elevated histone levels would be associated with end-organ damage and mortality, and that these effects would be mitigated by activation of the Protein C system.

Methods

From 6/2006 – 1/2010, all patients who were activated at the highest tier of a three-tiered trauma activation system in use at San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center were eligible for study enrollment under a waiver of consent, with subsequent sample and data collection only completed in those patients who directly or via surrogate provided informed consent. Patients that were younger than 18 years old, pregnant, transferred from another hospital, or incarcerated were excluded. The study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research. Patient enrollment for this study is described in detail elsewhere.15

Blood samples were prospectively collected via initial placement of a 16g or larger peripheral IV into citrated tubes containing 10mM of the protease inhibitor benzamidine within 10 minutes of emergency department arrival and again 6h after admission to the intensive care unit. Samples were centrifuged, and extracted plasma was stored at -80°C. Extracellular histone levels were measured using a commercially-available sandwich ELISA assay (Cell Death Detection ELISAplus kit: Roche Diagnostics; Indianapolis, IN). Briefly, 20uL of citrated patient plasma were diluted 1:4 in 1% BSA, 0.5% Tween, 1mM EDTA in PBS, and added to streptavidin-coated microtiter plates containing biotinylated mouse-anti-histone antibody and peroxidase-conjugated anti-DNA antibodies. After standard washing steps, peroxidase activity of the retained immunocomplexes was developed by incubation with ABTS (2,2′-azino-di[3-ethylbenzthiazoline-sulfonate]) and read in a spectrophotometer at 405nm; results are reported as absorbance units (AU). The mouse-anti-histone antibody (clone H11-4) reacts with histones H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Coagulation factors were analyzed on an STA Compact coagulation analyzer (Diagnostica Stago, Inc.; Parsippany, NJ). Activated protein C was assayed using an established ELISA method reported elsewhere.14

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (inter-quartile range [IQR]), or percentage. Unpaired univariate comparisons were made using Student's t-test assuming unequal variance for normally distributed data, Wilcoxon rank-sum testing for skewed data, and Fisher's exact test for proportions; paired data were compared using sign-rank tests. Injury was assessed by injury severity score (ISS).16 Acute lung injury was identified based on the American-European consensus conference definition.17 The diagnosis of MOF was defined as a multiple organ dysfunction score of≥3 using established Denver criteria.18 Standard logistic regression was performed to identify predictors of histone elevation. Cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to identify adjusted predictors of mortality. An alpha of 0.05 was considered significant. All data analysis was performed by the authors using Stata version 12 (StataCorp; College Station, TX).

Results

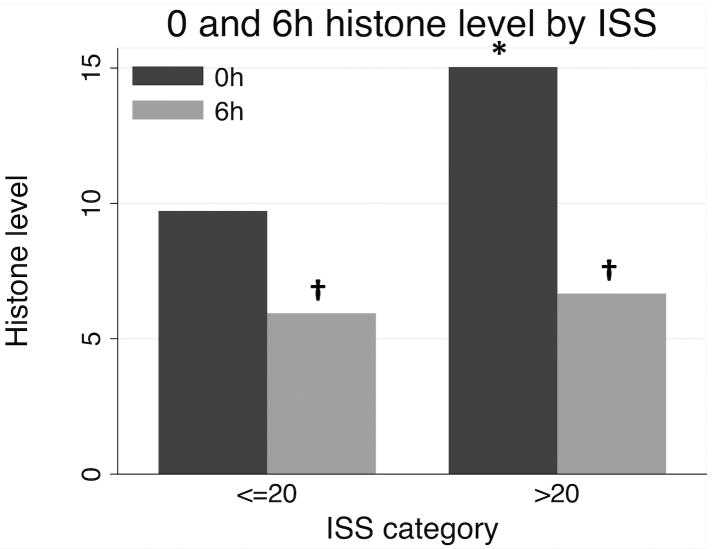

Overall characteristics for the 132 patients are presented in Table 1. Using an ELISA assay, extracellular histones were detectable at a median of 14.0 absorbance units (AU) on arrival, and declined to 6.4 AU by 6h. As no agreed-upon reference range for circulating histone levels exists clinically, in order to identify characteristics of patients with elevated histones on admission we dichotomized the study population into those in the highest quartile of histone levels on admission (≥50 AU, N=24) compared to the lower three quartiles (<50 AU, N=108). Patients with elevated (median 164 AU, IQR 102-364 AU) histones had significantly higher injury severity score (ISS) and significantly lower Glasgow coma score (GCS) than those with lower histone levels (median 10, IQR 4-19; Table 2). Histone elevation was also significantly associated with higher mechanical ventilation requirements, a 1.8-fold higher incidence of acute lung injury, 3.2-fold higher incidence of multiorgan failure, and 2.1-fold greater mortality (all p <0.05; Table 2). Although admission histone levels were higher in patients with severe injury (ISS>20; p=0.040), median histone levels fell by 6h in both severely and moderately-injured (ISS<=20) patients (p<0.05; Figure 1). We further investigated trends in histone levels from admission to 6h in 85 patients with histone data at both time points, identifying 31 (36.5%) patients with an increased or unchanged histone level at 6h, compared to 54 (63.5%) patients with decreasing histone levels. Despite no identifiable statistical differences in patient demographics or injury characteristics between these populations (data not shown), those with increasing histone levels had 2.5-fold higher mortality (32.3% vs. 13.0%, p=0.048).

Table 1.

Overall patient characteristics.

| (N = 132) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 40.9±18.7 |

| BMI | 27.7±5.2 |

| Penetrating | 40.0% |

| ISS | 24.2±13.4 |

| GCS | 9 (4-15) |

| Base deficit | -6.7±5.8 |

| Temperature | 35.5±0.9 |

| Prehospital IVF | 50 (0-500) |

| Hospital days | 10 (5-23) |

| ICU days | 4.5 (2-10.5) |

| Vent-free days/28d | 23 (1-26) |

| Multiorgan failure | 20.2% |

| Acute lung injury | 36.9% |

| Mortality | 21.2% |

Data are presented at mean ± standard deviation or median (inter-quartile range). BMI: body mass index, ISS: injury severity score, GCS: Glasgow coma score, IVF: intravenous fluids, ICU: intensive care unit.

Table 2.

Population characteristics by admission histone level.

| Extracellular histone level | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥50 AU (N=24) |

<50 AU (N=108) |

P-value | |

| Histone level | 164 (102-364) | 10 (4-19) | - |

| Age | 39.9±16.9 | 41.1±19.2 | 0.760 |

| BMI | 28.6±4.7 | 27.5±5.4 | 0.342 |

| Penetrating injury | 25.0% | 43.5% | 0.111 |

| ISS | 30.5±13.0 | 22.8±13.1 | 0.013 |

| GCS | 5 (3-12.5) | 10 (5-15) | 0.034 |

| Base deficit | -7.2±4.6 | -6.6±6.1 | 0.620 |

| Temperature | 35.5±1.2 | 35.5±0.8 | 0.890 |

| Prehospital IVF | 0 (0-500) | 75 (0-500) | 0.949 |

| 24h RBC | 4 (0-9) | 2 (0-6) | 0.124 |

| 24h FFP | 2 (0-4) | 0 (0-4) | 0.660 |

| 24h Plts | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-0) | 0.396 |

| Hospital days | 11.5 (3.5-28.5) | 8.5 (5-22.5) | 0.843 |

| ICU days | 6.5 (2.5-11.5) | 4 (2-9.5) | 0.303 |

| Vent-free days/28d | 7 (0-23) | 25 (7.5-26) | 0.007 |

| Acute lung injury | 58.3% | 32.1% | 0.020 |

| Multiorgan failure | 45.8% | 14.3% | 0.001 |

| Mortality | 37.5% | 17.6% | 0.050 |

Data are presented at mean ± standard deviation or median (inter-quartile range). BMI: body mass index, ISS: injury severity score, GCS: Glasgow coma score, IVF: intravenous fluids, RBC: red blood cell units, FFP: fresh frozen plasma units, Plts: platelet units, ICU: intensive care unit, VAP; ventilator-associated pneumonia.

p<0.05 by Student's t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test, or Fisher's exact test.

Figure 1.

Median 0 and 6h histone levels by injury severity. *p<0.05 between categories by Mann Whitney test; †p<0.05 between time points by paired sign-rank test.

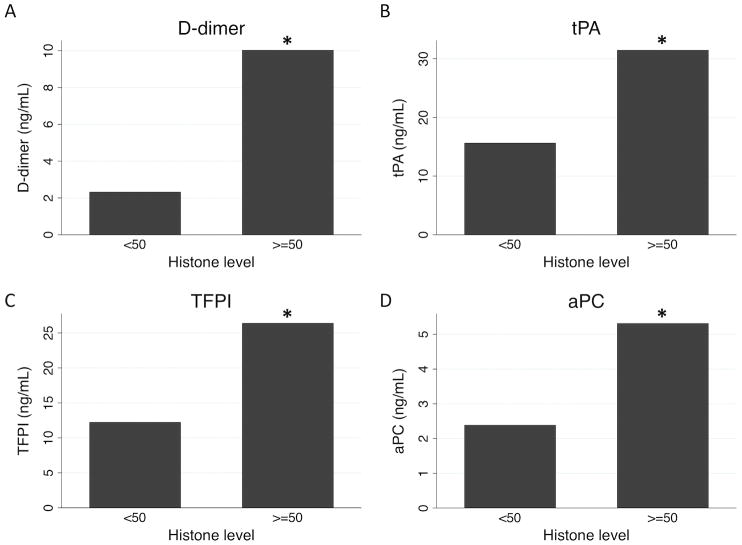

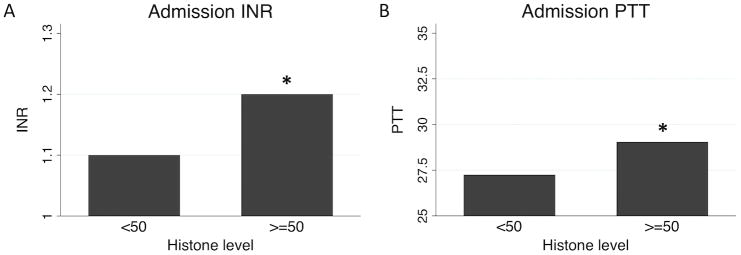

We then investigated correlations between coagulation-relevant measures by admission histone level. Patients with elevated histones had significantly higher median INR and PTT on admission (p=0.006 and p=0.047, respectively; Figure 2). Among clotting cascade proteins, no significant differences existed in procoagulant Factors V, VII, VIII, IX, or X (all p>0.1), in antithrombin III (p=0.860), or in unactivated Protein C (p=0.621). However, patients in the highest quartile of admission histone level had significant higher levels of the fibrinolytic markers D-dimer and tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA), as well as the systemic anticoagulants tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) and activated Protein C (aPC; all p<0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Admission international normalized ratio (INR; A) and partial thromboplastin times (PTT; B) by admission histone level. *p<0.05 by Wilcoxon rank-sum testing.

Figure 3.

Differences by admission histone level in D-dimer (A), tissue plasminogen activator (B), tissue factor pathway inhibitor (C), and activated protein C (D). *p<0.05 by Wilcoxon rank-sum testing.

In order to interrogate the temporal relationship between extracellular histone and aPC levels in terms of outcome, we used Cox proportional hazards regression to examine the multivariate association of changes in histone level with mortality. In unadjusted analysis, each 1 AU rise in histone level from admission to 6h was significantly associated with mortality (hazard ratio 1.006, p=0.009); when adjusted for age, injury severity, base deficit, and admission GCS, increasing histone level remained a robust predictor of later mortality (hazard ratio 1.005, p=0.013). The mean increase in histone level from 0 to 6h in the 31 patients with increased or unchanged levels at 6h was 53.5 AU; this increase is associated with a hazard ratio for mortality of 1.347 (p=0.013) in adjusted analysis. Conversely, the mean decrease in the 54 patients with decreasing histone levels was -71.6 AU, with a protective hazard ratio of 0.676 (p=0.013). However, when adjusted for the simultaneous change in aPC levels, the association between increasing histone level and mortality was abrogated (p=0.206, not significant) by a protective association of increasing aPC levels with reduced mortality (hazard ratio 0.900, p=0.020; final model given in Table 3).

Table 3.

Cox regression for mortality.

| OR | P | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.104 | 0.007 | (1.027 - 1.186) |

| ISS | 1.047 | 0.467 | (0.926 - 1.183) |

| Base deficit | 0.884 | 0.213 | (0.792 - 1.073) |

| Arrival GCS | 0.818 | 0.211 | (0.597 - 1.121) |

| Histone increase, 0 to 6h |

0.993 | 0.206 | (0.982 - 1.004) |

| aPC increase, 0 to 6h |

0.900 | 0.020 | (0.823 - 0.983) |

Cox proportional hazards regression for predictors of mortality. ISS: injury severity score, GCS: Glasgow coma score, aPC: activated Protein C.

p<0.05 by Wald test; Harrell's C = 0.743 for the model.

Discussion

Here we report a prospective analysis of circulating extracellular histone levels in 132 critically injured trauma patients. Patients within the highest quartile of extracellular histone levels on admission had significantly higher injury severity score and lower Glasgow coma score, as well as a 1.8-fold higher incidence of acute lung injury, 3.2-fold higher incidence of multiorgan failure, and 2.1-fold greater mortality. Elevated admission histone levels are significantly associated with coagulopathy, fibrinolysis, and activation of systemic anticoagulants. Using Cox proportional hazards regression, we identify an ongoing rise in histone levels as an independent predictor of mortality when adjusted for age, injury severity, shock, and impaired GCS. We further identify a statistical association between concomitant aPC activation and mitigation of the apparent effect of increasing histone levels. The finding that an ongoing rise in histone levels correlates with poor outcomes after trauma is clinically intuitive, as a reflection of ongoing cellular damage or continued inflammatory cytokine milieu. Previous studies have noted the presence of extracellular DNA possibly in complex with circulating histones,19, 20 and two studies have measured histone-complexed DNA directly as part of a biomarker screen in injured patients,21, 22 but to our knowledge this is the first detailed characterization of the patient and injury characteristics associated with extracellular histone levels after trauma, and the first to demonstrate a correlation with activated Protein C. Taken together, this work serves as an initial exploration of the role of extracellular histones and aPC in inflammatory and immune crosstalk.

This work points to three avenues for potential novel anti-inflammatory therapies in the care of trauma patients. First, Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 and TLR4 were recently identified as principle signaling mediators downstream of extracellular histones.6, 7 In addition to histones, other endogenous TLR2 and TLR4 ligands exist that are also released in response to inflammatory stimuli, including heat shock proteins, 23 tenascin C,24 and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1);25, 26 several of these have been specifically evaluated as prognostic biomarkers in trauma patients.27, 28 Thus the TLR2 and TLR4 receptors and their signaling apparatus are attractive therapeutic targets for pharmacological suppression of the sterile inflammatory response to trauma, although initial trials of novel anti-TLR4-based therapies are preliminary and have not yet demonstrated clinical benefit.29 Second, proteomic analysis of circulating biomarkers in LPS-induced septic shock has revealed citrullination of extracellular histones as an element of the early response of neutrophils to inflammatory stimuli,30 and the subsequent incorporation of citrullinated histones into NETs in response to infection. 31, 32 Ongoing work by Li et al. has demonstrated that treatment with the histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) significantly reduces the circulating levels of both native and citrullinated histone H333 as well as improves survival34, 35 in mouse models of LPS-induced septic shock. Third, recombinant activated Protein C was, until its recent removal from the market, the only drug shown to reduce mortality in adult patients with severe sepsis.36 Importantly, the anti-inflammatory effects of aPC are mediated via interaction with the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) leading to secondary activation of the protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR1),37, 38 while its anticoagulant effects are mediated by receptor-independent proteolysis of activated Factors Va and VIIIa. Kerschen et al. have recently shown that a recombinant form of aPC with preserved receptor binding sites but targeted mutation leading to <10% anticoagulant activity is equivalent to the native recombinant aPC in reducing mortality associated in both LPS-induced and polymicrobial sepsis models in mice.39 However, Xu et al. showed that proteolytic cleavage of histones by aPC was receptor-independent, and was augmented by the presence of membrane phospholipid similarly to the aPC-mediated cleavage of activated Factor Va. 7 Our group has also previously shown that selective inhibition of the anticoagulant function of aPC prevents coagulopathy with no impact on survival, while antibody blockade of both anticoagulant and cytoprotective functioning of aPC caused pulmonary thrombosis, perivascular hemorrhage, and increased mortality in a mouse model of trauma and hemorrhagic shock 13 Further in vitro and animal model work will be required to specifically delineate whether the mechanism of aPC-mediated cleavage of histones is independent of its anticoagulant function. In any case, histone burden as a potential biomarker in trauma and sepsis may revive interest in aPC-based therapies by providing for better patient selection and more goal-directed therapy.

Several limitations exist that are important for interpretation of this study. Ours remains an initial, single-center experience, and is subject to all attendant biases; further work is needed to confirm and extend these findings in larger series, other centers, and with extended temporal resolution. In particular, the physiological stress and additional tissue injury encountered during operative interventions may produce a ‘second hit’ phenomenon that is not accounted for here; sequential data collection at later time points may identify additional late sequelae of histone elevation. Furthermore, the difficulty in identifying an appropriate control group for trauma patient comparison impairs our ability to identify residual confounding. Taken together, these limitations highlight the fact that these data identify associations between histone release and concomitant activation of Protein C after traumatic injury, but should not be taken to prove causality. Further in vitro, in vivo, and clinical study is required to identify mechanisms of histone elevation and clearance after trauma, and to clearly delineate whether histone release is causative of as opposed to merely associated with poor outcomes after traumatic injury.

Here we identify histone release and clearance as promising areas of investigation in trauma resuscitation, and suggest a biologically plausible interaction with the Protein C system as a potential mechanism for further study. This highlights an intuitive potential explanation for the activation of the Protein C system in the service of the innate immune response to tissue injury, in which uncontrolled systemic activation may be an unintended side effect leading to the systemic coagulopathy seen after trauma.14 This suggests a place for the interaction between histones and aPC at a critical junction in the crosstalk between inflammation and coagulation. This work further highlights the parallels between mechanisms of pathogen-induced sepsis and those underlying the sterile inflammatory response to trauma, suggesting that insights and therapies from the critical care and sepsis literature may be applicable earlier in the hospital course to the care of the acutely injured trauma patient.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by NIH T32 GM-08258-20 (MEK) and NIH GM-085689 (MJC)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

Meetings: 2012 Western Trauma Association meeting in Vail, CO, 2/2012

Author Contributions: MEK and MJC prepared the manuscript, performed all data analysis, and take full responsibility for the data as presented. JX and CTE performed histone measurements and provided critical manuscript review. RFV and CH performed clotting factor and protein C measurements.

Contributor Information

Matthew E Kutcher, Email: matthew.kutcher@ucsfmedctr.org.

Jun Xu, Email: jun-xu@omrf.org.

Ryan F Vilardi, Email: vilardir@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu.

Coral Ho, Email: hoc@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu.

Charles T Esmon, Email: esmonc@omrf.org.

Mitchell Jay Cohen, Email: mcohen@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Esmon CT. The interactions between inflammation and coagulation. Br J Haematol. 2005;131(4):417–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeerleder S, Zwart B, Wuillemin WA, et al. Elevated nucleosome levels in systemic inflammation and sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(7):1947–51. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000074719.40109.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu J, Zhang X, Pelayo R, et al. Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat Med. 2009;15(11):1318–21. doi: 10.1038/nm.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(36):15880–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005743107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semeraro F, Ammollo CT, Morrissey JH, et al. Extracellular histones promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent mechanisms: involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood. 2011;118(7):1952–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Zhang X, Monestier M, et al. Extracellular histones are mediators of death through TLR2 and TLR4 in mouse fatal liver injury. J Immunol. 2011;187(5):2626–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esmon CT. Inflammation and the activated protein C anticoagulant pathway. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32(1):49–60. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng T, Liu D, Griffin JH, et al. Activated protein C blocks p53-mediated apoptosis in ischemic human brain endothelium and is neuroprotective. Nat Med. 2003;9(3):338–42. doi: 10.1038/nm826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuksel M, Okajima K, Uchiba M, et al. Activated protein C inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by inhibiting activation of both nuclear factor-kappa B and activator protein-1 in human monocytes. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88(2):267–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esmon CT. Protein C pathway in sepsis. Ann Med. 2002;34(7-8):598–605. doi: 10.1080/078538902321117823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464(7285):104–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesebro BB, Rahn P, Carles M, et al. Increase in activated protein C mediates acute traumatic coagulopathy in mice. Shock. 2009;32(6):659–65. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181a5a632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen MJ, Call M, Nelson M, et al. Critical Role of Activated Protein C in Early Coagulopathy and Later Organ Failure, Infection and Death in Trauma Patients. Ann Surg. 2011 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318235d9e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, et al. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: initiated by hypoperfusion: modulated through the protein C pathway? Ann Surg. 2007;245(5):812–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000256862.79374.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker SP, O'Neill B, Haddon W, Jr, et al. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14(3):187–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(3 Pt 1):818–24. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sauaia A, Moore EE, Johnson JL, et al. Validation of postinjury multiple organ failure scores. Shock. 2009;31(5):438–47. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31818ba4c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo YM, Rainer TH, Chan LY, et al. Plasma DNA as a prognostic marker in trauma patients. Clin Chem. 2000;46(3):319–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam NY, Rainer TH, Chan LY, et al. Time course of early and late changes in plasma DNA in trauma patients. Clin Chem. 2003;49(8):1286–91. doi: 10.1373/49.8.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson PI, Sorensen AM, Perner A, et al. High sCD40L levels Early After Trauma are Associated with Enhanced Shock, Sympathoadrenal Activation, Tissue and Endothelial Damage, Coagulopathy and Mortality. J Thromb Haemost. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansson PI, Stensballe J, Rasmussen LS, et al. A high admission syndecan-1 level, a marker of endothelial glycocalyx degradation, is associated with inflammation, protein C depletion, fibrinolysis, and increased mortality in trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2011;254(2):194–200. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318226113d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsujimoto H, Ono S, Efron PA, et al. Role of Toll-like receptors in the development of sepsis. Shock. 2008;29(3):315–21. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318157ee55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Midwood K, Sacre S, Piccinini AM, et al. Tenascin-C is an endogenous activator of Toll-like receptor 4 that is essential for maintaining inflammation in arthritic joint disease. Nat Med. 2009;15(7):774–80. doi: 10.1038/nm.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu M, Wang H, Ding A, et al. HMGB1 signals through toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and TLR2. Shock. 2006;26(2):174–9. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000225404.51320.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Xiang M, Yuan Y, et al. Hemorrhagic shock augments lung endothelial cell activation: role of temporal alterations of TLR4 and TLR2. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297(6):R1670–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00445.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen MJ, Brohi K, Calfee CS, et al. Early release of high mobility group box nuclear protein 1 after severe trauma in humans: role of injury severity and tissue hypoperfusion. Crit Care. 2009;13(6):R174. doi: 10.1186/cc8152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peltz ED, Moore EE, Eckels PC, et al. HMGB1 is markedly elevated within 6 hours of mechanical trauma in humans. Shock. 2009;32(1):17–22. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3181997173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barochia A, Solomon S, Cui X, et al. Eritoran tetrasodium (E5564) treatment for sepsis: review of preclinical and clinical studies. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7(4):479–94. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.558190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neeli I, Khan SN, Radic M. Histone deimination as a response to inflammatory stimuli in neutrophils. J Immunol. 2008;180(3):1895–902. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neeli I, Dwivedi N, Khan S, et al. Regulation of extracellular chromatin release from neutrophils. J Innate Immun. 2009;1(3):194–201. doi: 10.1159/000206974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papayannopoulos V, Zychlinsky A. NETs: a new strategy for using old weapons. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(11):513–21. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Liu B, Fukudome EY, et al. Identification of citrullinated histone H3 as a potential serum protein biomarker in a lethal model of lipopolysaccharide-induced shock. Surgery. 2011;150(3):442–51. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Liu B, Fukudome EY, et al. Surviving lethal septic shock without fluid resuscitation in a rodent model. Surgery. 2010;148(2):246–54. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Liu B, Zhao H, et al. Protective effect of suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid against LPS-induced septic shock in rodents. Shock. 2009;32(5):517–23. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181a44c79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(10):699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riewald M, Petrovan RJ, Donner A, et al. Activation of endothelial cell protease activated receptor 1 by the protein C pathway. Science. 2002;296(5574):1880–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1071699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosnier LO, Griffin JH. Inhibition of staurosporine-induced apoptosis of endothelial cells by activated protein C requires protease-activated receptor-1 and endothelial cell protein C receptor. Biochem J. 2003;373(Pt 1):65–70. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerschen EJ, Fernandez JA, Cooley BC, et al. Endotoxemia and sepsis mortality reduction by non-anticoagulant activated protein C. J Exp Med. 2007;204(10):2439–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]