Abstract

Paenibacillus senegalensis strain JC66T, is the type strain of Paenibacillus senegalensis sp. nov., a new species within the genus Paenibacillus. This strain, whose genome is described here, was isolated from the fecal flora of a healthy patient. P. senegalensis strain JC66T is a facultative Gram-negative anaerobic rod-shaped bacterium. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence and annotation. The 5,581,254 bp long genome (1 chromosome but no plasmid) exhibits a G+C content of 48.2% and contains 5,008 protein-coding and 51 RNA genes, including 9 rRNA genes.

Keywords: Paenibacillus senegalensis, genome

Introduction

Paenibacillus senegalensis strain JC66T (= CSUR P157 = DSM 25958) is the type strain of P. senegalensis sp. nov. This bacterium was isolated from the stool of a healthy Senegalese patient as part of a “culturomics” study aiming at cultivating all species within human feces, individually. It is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, indole-negative rod.

We recently proposed to include genomic data among other criteria to describe new bacterial species, rather than relying on the poorly reproducible DNA-DNA hybridization and G+C content determination [1]. This strategy creates a polyphasic approach by combining [2] the use of 16S rRNA sequence cutoff values [3] with the plethora of new information provided by high throughput genome sequencing and mass spectrometric analyses of bacteria [4].

Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for P. senegalensis sp. nov. strain JC66T together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation. These characteristics support the creation of the P. senegalensis species.

To date, the genus Paenibacillus (Ash et al. 1994) includes Gram-variable, facultative anaerobic, endospore-forming bacteria, originally classified within the genus Bacillus and then reclassified as a separate genus in 1993 [5]. The genus consists of 134 described species and 4 subspecies that have been isolated from a variety of environments including soil, water, rhizosphere, vegetable matter, forage and insect larvae, as well as human specimens [6-9]. The bacteria belonging to this genus produce various extracellular enzymes such as polysaccharide-degrading enzymes and proteases, and have gained importance in agriculture, horticulture, industrial and medical applications [10]. Various Paenibacillus spp. also produce antimicrobial substances that are active on a wide spectrum of microorganisms such as fungi, soil bacteria, plant pathogenic bacteria and even important anaerobic pathogens such as Clostridium botulinum [11]. In addition, several Paenibacillus bacteria can form complex patterns on semi-solid surfaces that require self-organization and cooperative behavior of individual cells by employing sophisticated chemical communication [12]. Pattern formation and self-organization of bacteria within this genus reflect their social behavior and might provide insights into the evolutionary development of the collective action of cells in higher organisms [13]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of isolation of Paenibacillus sp. from the normal fecal flora.

Classification and features

A stool sample was collected from a healthy 16-year-old male Senegalese volunteer patient living in Dielmo (a rural village in the Guinean-Sudanian zone in Senegal), who was included in a research protocol. Written assent was obtained from this individual; no written consent was needed from his guardians for this study because he was older than 15 years old (in accordance with the previous project approved by the Ministry of Health of Senegal and the assembled village population and as published elsewhere [14]. Both this study and the assent procedure were approved by the National Ethics Committee of Senegal (CNERS) and the Ethics Committee of the Institut Fédératif de Recherche IFR48, Faculty of Medicine, Marseille, France (agreement numbers 09-022 and 11-017). The fecal specimen was preserved at -80°C after collection and sent to Marseille. Strain JC66T (Table 1) was isolated in February 2011 after inoculation in Schaedler medium added with kanamycin and vancomycin (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), and incubation at 37°C in aerobic atmosphere.

Table 1. Classification and general features of Paenibacillus senegalensis strain JC66T.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [15] | |

| Phylum Firmicutes | TAS [16] | ||

| Class Bacilli | TAS [17] | ||

| Order Bacillales | TAS [18] | ||

| Family Paenibacillaceae | TAS [17] | ||

| Genus Paenibacillus | TAS [5] | ||

| Species Paenibacillus senegalensis | IDA | ||

| Type strain JC66T | IDA | ||

| Gram stain | negative | IDA | |

| Cell shape | rod-shaped | IDA | |

| Motility | motile | IDA | |

| Sporulation | sporulating | IDA | |

| Temperature range | mesophile | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | 37°C | IDA | |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | growth in BHI medium + 5% NaCl | IDA |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | facultative anaerobic | IDA |

| Carbon source | unknown | ||

| Energy source | unknown | ||

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | human gut | IDA |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | IDA |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | unknown | |

| Biosafety level | 2 | ||

| Isolation | human feces | ||

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Senegal | IDA |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | September 2010 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 13.7167 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Longitude | - 16.4167 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | 51 m above sea level | IDA |

aEvidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [19]. If the evidence is IDA, then the property was directly observed for a live isolate by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

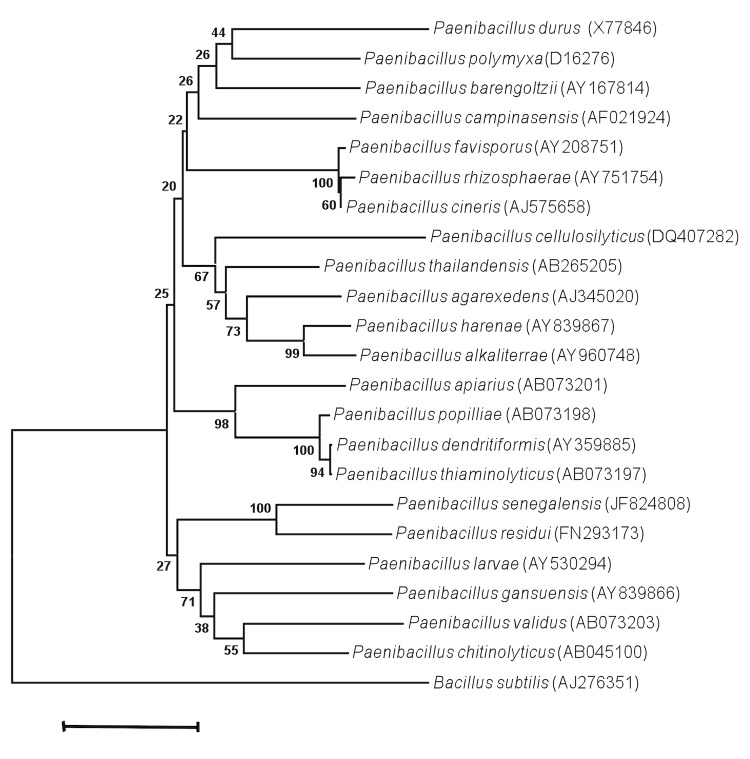

Strain JC66T exhibited a 95.54% nucleotide sequence similarity with P. residui [20], the phylogenetically-closest validated Paenibacillus species (Figure 1). Although sequence similarity of the 16S operon is not uniform across taxa, this value was lower than the 98.7% 16S rRNA gene sequence threshold recommended by Stackebrandt and Ebers to delineate a new species without carrying out DNA-DNA hybridization [3].

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of Paenibacillus senegalensis strain JC66T relative to other type strains within the Paenibacillus genus. GenBank accession numbers are indicated in parentheses. Sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW, and phylogenetic inferences obtained using the maximum-likelihood method within the MEGA software. Numbers at the nodes are bootstrap values obtained by repeating 500 times the analysis to generate a majority consensus tree. Paenibacillus subtilis was used as outgroup. The scale bar represents a 2% nucleotide sequence divergence.

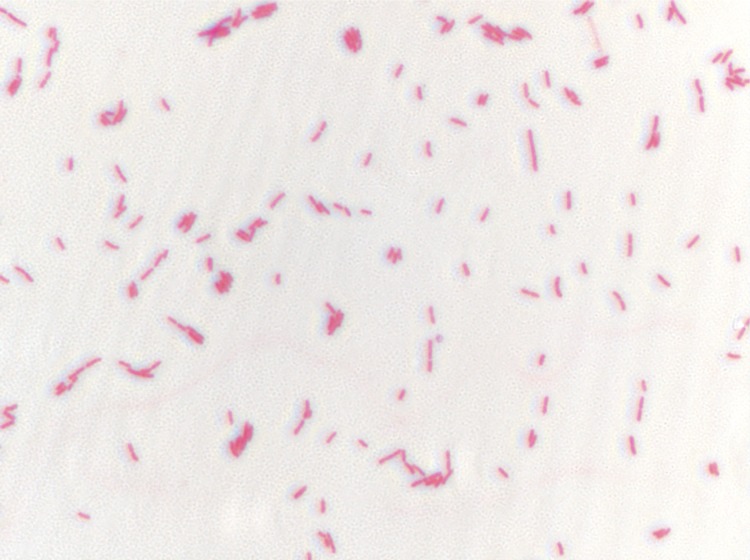

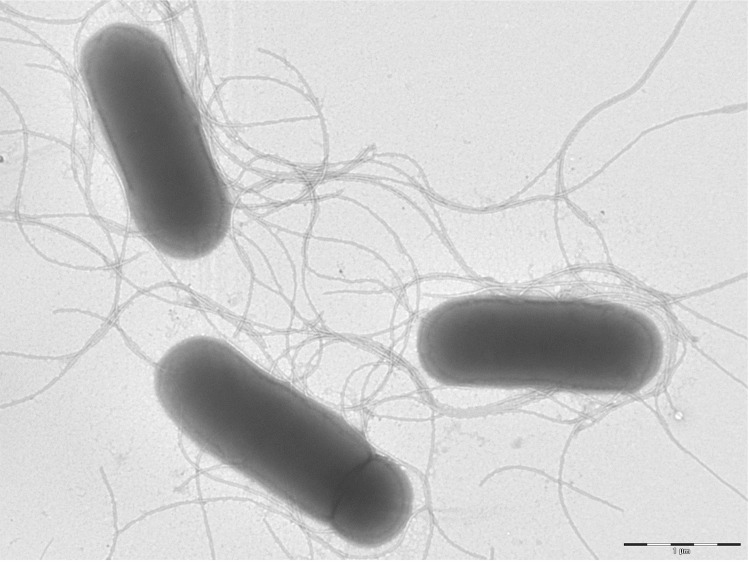

Growth at different temperatures (25, 30, 37, 45°C) was tested; no growth occurred at 25°C, growth occurred at 30° and 45°C, and optimal growth was observed at 37°C. Translucent and flat colonies were 2 mm in diameter on blood-enriched Columbia agar. Growth of the strain was tested under anaerobic and microaerophilic conditions using GENbag anaer and GENbag microaer systems, respectively (BioMérieux), and in the presence of air, with or without 5% CO2. Growth was achieved in aerobic condition with or without CO2, and weak growth was observed in microaerophilic and anaerobic conditions. Gram-staining showed a rod-shaped Gram-negative bacterium (Figure 2). The motility test was positive. Cells showed a mean diameter of 0.66 µm using electron microscopy and exhibited peritrichous flagellae (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Gram-staining of P. senegalensis strain JC66T

Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscopy of P. senegalensis strain JC66T, using a Morgani 268D (Philips) at an operating voltage of 60kV. The scale bar represents 1 µm.

Strain JC66T exhibited catalase activity but was negative for indole production. Using API 50CH, positive reactions were observed for D-galactose, D-glucose, D-fructose, D-mannose, and D-sorbitol fermentation. Positive reactions were also observed for N-acteylglucosamine arbutine, esculine, salicine, D-maltose, D-lactose, D-saccharose, D-trehalose, inuline and D-tagatose. Using API ZYM, positive reactions were observed for leucine arylamidase and weak reactions were observed for alkaline phosphatase, esterase lipase, acid phosphatase and naphtol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase. Using API Coryne, positive reactions were observed for β-glucuronidase, phosphatase alkaline, α-glucosidase, α-galactosidase, and N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activities. P. senegalensis is susceptible to amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, imipenem, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, rifampin and vancomycin, but resistant to metronidazole.

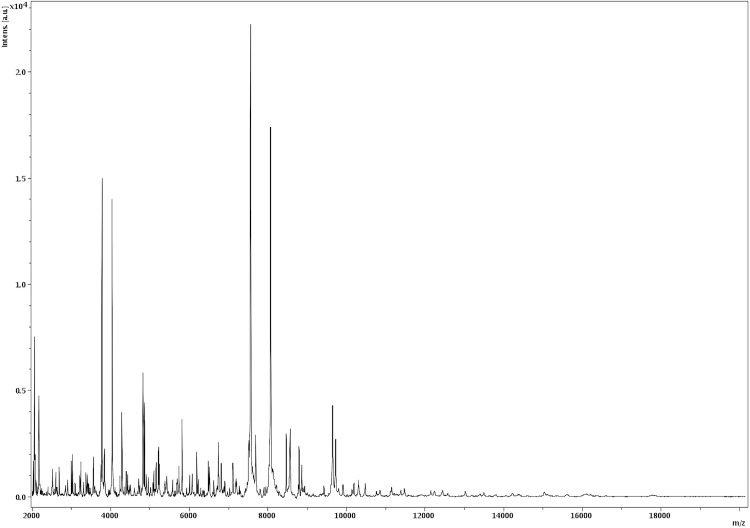

Matrix-assisted laser-desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) MS protein analysis was carried out as previously described [21]. Briefly, a pipette tip was used to pick one isolated bacterial colony from a culture agar plate, and to spread it as a thin film on a MTP 384 MALDI-TOF target plate (Bruker Daltonics, Germany). Twelve distinct deposits were done for strain JC66T from twelve isolated colonies. Each smear was overlaid with 2µL of matrix solution (saturated solution of alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) in 50% acetonitrile, 2.5% tri-fluoracetic acid, and allowed to dry for five minutes. Measurements were performed with a Microflex spectrometer (Bruker). Spectra were recorded in the positive linear mode for the mass range of 2,000 to 20,000 Da (parameter settings: ion source 1 (ISI), 20kV; IS2, 18.5 kV; lens, 7 kV). A spectrum was obtained after 675 shots at a variable laser power. The time of acquisition was between 30 seconds and 1 minute per spot. The twelve JC66T spectra were imported into the MALDI Bio Typer software (version 2.0, Bruker) and analyzed by standard pattern matching (with default parameter settings) against the main spectra of 3,769 bacteria, including spectra from 121 validated Paenibacillus species used as reference data, in the Bio Typer database. The method of identification includes the m/z from 3,000 to 15,000 Da. For every spectrum, 100 peaks at most were taken into account and compared with the spectra in database. A score enabled the identification, or not, from the tested species: a score ≥ 2 with a validated species enabled the identification at the species level; a score ≥ 1.7 but < 2 enabled the identification at the genus level; and a score < 1.7 did not enable any identification. For strain JC66T, the obtained score was 1.236, thus suggesting that our isolate was not a member of a known species. We incremented our database with the spectrum from strain JC66T (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Reference mass spectrum from P. senegalensis strain JC66T. Spectra from 12 individual colonies were compared and a reference spectrum was generated.

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

The organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position and 16S rRNA similarity to other members of the genus Paenibacillus, and is part of a “culturomics” study of the human digestive flora aiming at isolating all bacterial species occurring in human feces. It is the 14th genome of a Paenibacillus species and the first genome of Paenibacillus senegalensis sp. nov. The Genbank accession number is CAES00000000. Table 2 shows the project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance.

Table 2. Project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | High-quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | One 454 paired end 3-kb library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | 454 GS FLX Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 21× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.5.3 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| INSDC ID | PRJEB69 | |

| Genbank ID | CAES00000000 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | January 3, 2012 | |

| Gold ID | Gi13532 | |

| MIGS-13 | Project relevance | Study of the human gut microbiome |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

P. senegalensis sp. nov. strain JC66T, (= CSUR P157 = DSM 25958), was grown on blood agar medium at 37°C. Ten petri dishes were spread and resuspended in 5x100µl of G2 buffer (EZ1 DNA Tissue kit, Qiagen). A first mechanical lysis was performed by glass powder on the Fastprep-24 device (Sample Preparation system) from MP Biomedicals, USA for 40 seconds. DNA was then incubated for a lysozyme treatment (30 minutes at 37°C) and extracted using the BioRobot EZ 1 Advanced XL (Qiagen). The DNA was then concentrated and purified on a Qiamp kit (Qiagen). The yield and the concentration was measured by the Quant-it Picogreen kit (Invitrogen) on the Genios_Tecan fluorometer at 40.2 ng/µl.

Genome sequencing and assembly

This project was loaded twice on a ¼ region of PTP Picotiterplates for the paired-end sequencing, and once on a 1/8 region for the shotgun sequencing. The shotgun library was constructed with 500 ng of DNA with the GS Rapid library Prep kit (Roche). 5 µg of DNA was mechanically fragmented on the Hydroshear device (Digilab, Holliston, MA, USA) with an enrichment size at 3-4kb. The DNA fragmentation was visualized through the Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer on a DNA labchip 7500 with an optimal size of 3.7 kb. The library was constructed according to the 454 Titanium paired-end protocol and manufacturer. Circularization and nebulization were performed and generated a pattern with an optimum at 422 bp. After PCR amplification through 15 cycles followed by double size selection, the single stranded paired end library was then quantified on the Quant-it Ribogreen kit (Invitrogen) on the Genios Tecan fluorometer at 180 pg/µL. The library concentration equivalence was calculated as 7.82E+08 molecules/µL. The library was stored at -20°C until further use.

The shotgun library was clonally amplified with 3cpb in 3 emPCR reactions and the paired end library was amplified with lower cpb (1cpb) in 3 emPCR reactions with the GS Titanium SV emPCR Kit (L6ib-L) v2. The yield of the emPCR was 3.52% for the shotgun and 8.01% for the paired-end according to the quality expected by the range of 5 to 20% from the Roche procedure.

Approximately 340,000 beads for the 1/8 region for the shotgun and 790,000 beads on the 1/4 region for the paired-end were loaded on the GS Titanium PicoTiterPlates PTP kit 70×75 and sequenced with the GS Titanium Sequencing Kit XLR70 (Roche). The runs were performed overnight and then analyzed on the cluster through the gsRunBrowser and Newbler assembler (Roche). A total of 370,625 passed filter wells were obtained and generated 115.35Mb with an average length of 312 bp. These sequences were assembled using Newbler with 90% identity and 40bp as overlap. The final assembly identified 197 large contigs (>1500bp) arranged into 18 scaffolds, for a genome size of 5.58Mb, which corresponds to a 21.01 × coverage.

Genome annotation

Open Reading Frames (ORFs) were predicted using Prodigal [22] with default parameters but the predicted ORFs were excluded if they were spanning a sequencing GAP region. The predicted bacterial protein sequences were searched against the GenBank database [23] and the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) databases using BLASTP. The tRNAScanSE tool [24] was used to find tRNA genes, whereas ribosomal RNAs were found by using RNAmmer [25] and BLASTn against the NR database. Lipoprotein signal peptides and transmembrane helices were predicted using SignalP [26] and TMHMM [27], respectively. ORFans were identified if their BLASTP E-value was lower than 1e-03 for alignment length greater than 80 amino acids. If alignment lengths were smaller than 80 amino acids, we used an E-value of 1e-05. Such parameter thresholds have already been used in previous works to define ORFans. To estimate the mean level of nucleotide sequence similarity at the genome level between Paenibacillus species, we compared the ORFs only using BLASTN and the following parameters: a query coverage of ≥ 70% and a minimum nucleotide length of 100 bp. Artemis [28] was used for data management and DNA Plotter [29] was used for visualization of genomic features. Mauve alignment tool was used for multiple genomic sequence alignment [30].

Genome properties

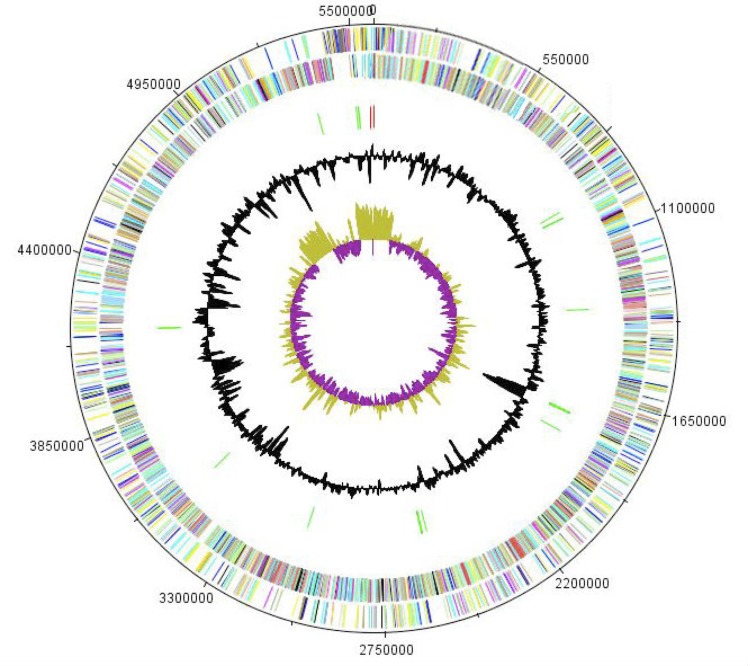

The genome of P. senegalensis sp. nov. strain JC66T is 5,581,254 bp long (1 chromosome but no plasmid) with a 48.2% G + C content of (Figure 5 and Table 3). Of the 5,059 predicted genes, 5,008 were protein-coding genes, and 51 were RNAs. Nine rRNA genes (three 16S rRNA, three 23S rRNA and three 5S rRNA) and 42 predicted tRNA genes were identified in the genome. A total of 3,588 genes (71.00%) were assigned a putative function. Five hundred and four genes were identified as ORFans (10%). The remaining genes were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The properties and statistics of the genome are summarized in Table 3. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Figure 5.

Graphical circular map of the chromosome. From the outside in, the outer two circles shows open reading frames oriented in the forward (colored by COG categories) and reverse (colored by COG categories) direction, respectively. The third circle marks the rRNA gene operon (red) and tRNA genes (green). The fourth circle shows the G+C% content plot. The inner-most circle shows GC skew, purple indicating negative values whereas olive for positive values.

Table 3. Nucleotide content and gene count levels of the genome.

| Attribute | Value | % of Totala |

|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | 5,581,254 | |

| G+C content (bp) | 2,690,164 | 48.2 |

| Coding region (bp) | 4,693,047 | 84.08 |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 5,059 | 100 |

| RNA genes | 51 | 0.89 |

| rRNA operons | 3 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 5,008 | 99.10 |

| Genes with function prediction | 3,805 | 75.30 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3,588 | 71.00 |

| Genes with peptide signals | 366 | 7.30 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,407 | 27.84 |

a The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 181 | 3.61 | Translation |

| A | 0 | 0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 458 | 9.14 | Transcription |

| L | 180 | 3.59 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.02 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 36 | 0.72 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 122 | 2.44 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 231 | 4.61 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 220 | 4.39 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 53 | 1.06 | Cell motility |

| Z | 2 | 0.04 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 49 | 0.98 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 102 | 2.03 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 154 | 3.07 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 507 | 10.12 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 318 | 6.35 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 81 | 1.61 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 133 | 2.65 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 84 | 1.68 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 239 | 4.78 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 81 | 1.62 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 573 | 11.44 | General function prediction only |

| S | 304 | 6.07 | Function unknown |

| - | 1,420 | 28.35 | Not in COGs |

a The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

Comparison with the genomes from other Paenibacillus species

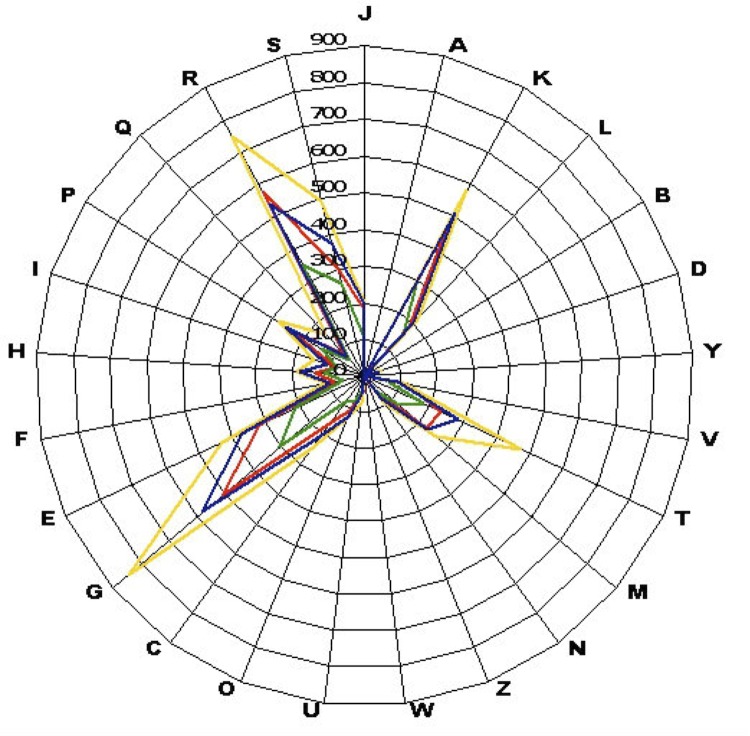

To date, the genomes of three validated Paenibacillus species are available. Here, we compared the genome sequence of P. senegalensis strain JC66T with those of P. terrae strain HPL-003 (GenBank accession number NC_016641.1), P. polymyxa strain M1 (NC_017542.1) and P. mucilaginosus strain 3016 (NC_016935.1). The P. senegalensis genome has a similar size to that of P. polymyxa (5.58 Mb vs 5.73 Mb, respectively) but is smaller than those of P. terrae and P. mucilaginosus (6.08 and 8.74 Mb, respectively). The G+C content of P. senegalensis is higher than those of P. polymyxa and P. terrae (48.2, 44.8 and 46.8%, respectively) but smaller than P. mucilaginosus (58.31%). The gene content of P. senegalensis is larger than those of P. polymyxa (5,059 and 3,602, respectively) but smaller than those of P. terrae and P. mucilaginosus (6,414 and 5,642, respectively). The ratio of genes per Mb of P. senegalensis is larger than those of P. mucilaginosus and P. polymyxa (906, 861 and 578, respectively) but smaller than that of P. terrae (928). The gene distribution into COG categories is very similar in all four compared genomes (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Compared distribution of genes in COGs functional categories in P. senegalensis (colored in red), P. terrae (colored in blue), P. mucilaginosus (colored in yellow) and P. polymyxa (colored in green) chromosomes.

P. senegalensis shares mean degrees of sequence similarity at the genome level of 81.5% (range 70.34-100%), 80.6% (range 70.46-100%) and 81.32% (range 70.34-100%) with P. polymyxa, P. mucilaginosus and P. terrae, respectively.

Conclusion

On the basis of phenotypic, phylogenetic and genomic analyses, we formally propose the creation of Paenibacillus senegalensis sp. nov. that contains the strain JC66T. This bacterium has been found in Senegal.

Description of Paenibacillus senegalensis sp. nov.

Paenibacillus senegalensis (se.ne.gal.e’n.sis. L. gen. masc. n. senegalensis, pertaining to Senegal, the country from which the specimen was obtained).

Colonies are 2 mm in diameter on blood-enriched Columbia agar. Cells are rod-shaped with a mean diameter of 0.66 μm. Optimal growth is achieved in aerobic condition with or without CO2. Weak growth is observed in microaerophilic and anaerobic conditions. Growth occurs between 30 and 45°C, with optimal growth observed at 37°C, on blood-enriched agar. Cells are Gram-negative, endospore-forming, and motile. Cells are catalase positive but negative for indole production. D-galactose, D-glucose, D-fructose, D-mannose, D-sorbitol, N-Acetylglucosamine arbutine, esculine, salicine, D-maltose, D-lactose, D-saccharose, D-trehalose, inuline, D-tagatose, β-glucuronidase, phosphatase alkaline, α-glucosidase, α-galactosidase, and N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase metabolic activities are present. Weak alkaline phosphatase, esterase lipase, acid phosphatase and naphtol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase activities are observed. Cells are susceptible to amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, imipenem, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, rifampin and vancomycin, but resistant to metronidazole. The G+C content of the genome is 48.2%. The 16S rRNA and genome sequences are deposited in Genbank under accession numbers JF824808 and CAES00000000, respectively. The type strain is JC66T (= CSUR P157 = DSM 25958) was isolated from the fecal flora of a healthy patient in Senegal.

References

- 1.Lagier JC, Karkouri EK, Nguyen TT, Armougom F, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Anaerococcus senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:116-125 10.4056/sigs.2415480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tindall BJ, Rosselló-Móra R, Busse HJ, Ludwig W, Kämpfer P. Notes on the characterization of prokaryote strains for taxonomic purposes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:249-266 10.1099/ijs.0.016949-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stackebrandt E, Ebers J. Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol Today 2006; 33:152-155 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welker M, Moore ER. Applications of whole-cell matrix-assisted laser-desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry in systematic microbiology. Syst Appl Microbiol 2011; 34:2-11 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ash C, Priest FG, Collins MD. Molecular identification of rRNA group 3 bacilli (Ash, Farrow, Wallbanks and Collins) using a PCR probe test. Proposal for the creation of a new genus Paenibacillus. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 1993; 64:253-260 10.1007/BF00873085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lal S, Tabacchioni S. Ecology and biotechnological potential of Paenibacillus polymyxa: a minireview. Indian J Microbiol 2009; 49:2-10 10.1007/s12088-009-0008-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McSpadden Gardener BB. Ecology of Bacillus and Paenibacillus spp. in Agricultural Systems. Phytopathology 2004; 94:1252-1258 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.11.1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montes MJ, Mercade E, Bozal N, Guinea J. Paenibacillus antarcticus sp. nov., a novel psychrotolerant organism from the Antarctic environment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2004; 54:1521-1526 10.1099/ijs.0.63078-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ouyang J, Pei Z, Lutwick L, Dalal S, Yang L, Cassai N, Sandhu K, Hanna B, Wieczorek RL, Bluth M, Pincus MR. Case report: Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus: a new cause of human infection, inducing bacteremia in a patient on hemodialysis. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2008; 38:393-400 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konishi J, Maruhashi K. 2-(2'-Hydroxyphenyl) benzene sulfinate desulfinase from the thermophilic desulfurizing bacterium Paenibacillus sp. strain A11-2: purification and characterization. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2003; 62:356-361 10.1007/s00253-003-1331-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girardin H, Albagnac C, Dargaignaratz C, Nguyen-The C, Carlin F. Antimicrobial activity of foodborne Paenibacillus and Bacillus spp. against Clostridium botulinum. J Food Prot 2002; 65:806-813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben-Jacob E, Cohen I, Gutnick DL. Cooperative organization of bacterial colonies: from genotype to morphotype. Annu Rev Microbiol 1998; 52:779-806 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. Bacterial Signal Transduction Modules: from Genomics to Biology. ASM News 2005; 71:326-333 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trape JF, Tall A, Diagne N, Ndiath O, Ly AB, Faye J, Dieye-Ba F, Roucher C, Bouganali C, Badiane A, et al. Malaria morbidity and pyrethroid resistance after the introduction of insecticide-treated bednets and artemisinin-based combination therapies: a longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis 2011; 11:925-932 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70194-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archae, Bacteria, and Eukarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skerman VBD, Sneath PHA. Approved list of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bact 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garrity GM, Holt J. Taxonomic outline of the Archae and Bacteria In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Springer-Verlag, New York, 2001, p.155-166. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prevot AR. Dictionnaire des bactéries pathogens. In: Hauduroy P, Ehringer G, Guillot G, Magrou J, Prevot AR, Rosset, Urbain A (eds). Paris, Masson, 1953, p.1-692. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaz-Moreira I, Figueira V, Lopes AR, Pukall R, Spröer C, Schumann P, Nunes OC, Manaia CM. Paenibacillus residui sp. nov., isolated from urban waste compost. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:2415-2419 10.1099/ijs.0.014290-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seng P, Drancourt M, Gouriet F, La Scola B, Fournier PE, Rolain JM, Raoult D. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:543-551 10.1086/600885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prodigal. http://prodigal.ornl.gov

- 23.Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Clark K, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:D48-D53 10.1093/nar/gkr1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. t-RNAscan-SE: a program for imroved detection of transfer RNA gene in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol 2004; 340:783-795 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 2001; 305:567-580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, Rajandream MA, Barrell B. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 2000; 16:944-945 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carver T, Thomson N, Bleasby A, Berriman M, Parkhill J. DNAPlotter: circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:119-120 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res 2004; 14:1394-1403 10.1101/gr.2289704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]