INTRODUCTION

For students enrolled in medical microbiology-related courses, learning pathogenesis may lead to information overload and a ‘memorize–repeat’ learning style. In addition, to teach complex topics such as microbial pathogenesis, instructors may need to incorporate approaches that require more active student involvement on how the course material is learned and presented. Creative writing and role-playing may help students retain course information and expand their knowledge on how topics addressed in pathogenesis are related to each other. In the ”General Hospital” assignment, students form groups to write and present a skit based on the pathogenesis of an infectious disease — leading the audience through an educational, albeit entertaining, piece related to many topics in microbiology. This four-to-six week assignment (from introduction to presentation of skits) provides students with an outlet to (1) write an entertaining scenario about topics in pathogenesis, and (2) present the information to the audience in a very natural yet accurate way.

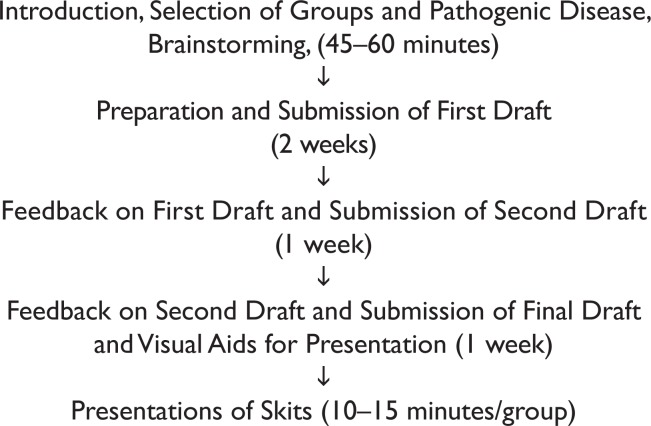

Overview of assignment and approximate time for each step:

PROCEDURE

I. Introducing the assignment

A. Reducing student apprehension about creative writing and role-playing

The goal of the ‘General Hospital’ assignment is for students to write and perform a skit based on a pathogenic disease and share their knowledge with classmates in a creative format. When an instructor introduces an assignment that requires the use of creative writing and role-playing to undergraduates, he or she may encounter resistance from students who prefer to be evaluated via traditional methods of testing (e.g., multiple-choice or short answer questions directly from lecture material). The instructor may also receive comments about role-playing and skits being considered too elementary for college-level students, or a ‘dumbing down’ of course information.

Before introducing assignment details, the instructor is encouraged to engage students in a discussion about how information related to topics in pathogenesis is presented in their everyday lives. The dialog will stimulate students to reflect on how they acquire information about various pathogens and their associated diseases outside of the classroom. Prompts for discussion can include asking students to reflect on illnesses that are of personal interest. For example: (1) a student may have a grandparent who was diagnosed with shingles and be curious to learn more about the disease and its treatment, or (2) media reports about outbreaks of cholera in Haiti inspire a student to search for more information about the disease. A light-hearted way of introducing the project is to show a clip from the television show Seinfeld, called “The Burning,” where the character Kramer has his first acting gig – playing a man who contracts gonorrhea – for an audience of medical residents at a teaching hospital. This clip demonstrates how medical residents participate in mock sessions with ‘patients’ during their training, and is a light-hearted portrayal of circumstances and symptoms that help them diagnose the patient.

B. Structure of ’General Hospital’ skit

Presentation Time Limit: 10–15 minutes

Characters: The students write and present the information about the infectious disease through different roles — in any given presentation group, there are students who play the medical staff to diagnose the patient and provide treatment. However, there are also the patient(s), their family and/or friends.

Scenes: There must be a connection between the series of events leading to the patient(s) visiting medical staff at ‘General Hospital’.

Students must include information about the following questions in the skit, which are presented in a natural and logical fashion. Therefore, the questions aren’t necessarily presented in the order listed below.

Questions to address in ‘General Hospital’ skit:

How did the patient contract the illness?

Can the patient infect others?

What microbe(s) are responsible for this illness?

What are the symptoms? When did the patient first notice the symptoms? How will the symptoms progress if the patient is not treated in a timely manner?

What body system(s) are compromised in the illness (skin, nervous, cardiovascular, etc)?

What medical treatments are available (antibiotics, antivirals, rest, etc)? How do they work (i.e., treating symptoms or targeting the pathogen(s))? Are there side effects to the treatments?

What tests are needed to properly diagnose the patient?

When will the patient recover? Will the patient fully recover?

What precautions or preventive measures could the patient have taken to avoid becoming infected?

What interesting news or research published within the last 12 months is related to this illness (from an instructor-approved news article)? How is it related to relevant information written in the skit?

While introducing the assignment, the instructor can incorporate a review of previous skits and presentations from students, discussing how they met assignment guidelines (see Supplemental Materials, Appendices 1 and 2).

C. Selection of groups and pathogenic disease for skit/brainstorming

Once the assignment is introduced, students will be placed into groups of three to four students. It is recommended to have a maximum group number of four students. More than four students may lead to issues with group dynamics (e.g., disagreement among group members about character selection, storyline and disease selected, etc.). If needed, smaller groups that require additional characters can recruit students from other groups or outside of the class for the presentation portion of the assignment. To build team spirit among the group and infuse fun into the process, the instructor can ask the groups to create a team name related to their upcoming skit, such as ‘Team Botoxx’ or ‘Trick, No Treat’; for botulism and trichomoniasis, respectively.

Approximately 15–20 minutes will be needed in class for groups to brainstorm which pathogenic disease they will select and consult the instructor for initial ideas on how to develop the skit. After the brainstorming period, students must present the instructor with the disease selected. This assignment was designed to allow groups to select the disease for the skit, which was then accepted by the instructor on a first-come, first-serve basis. If there are multiple groups addressing the same disease, it is advised that the instructor notify groups as to which diseases have been selected. Groups may opt to change their selection. However, the instructor should keep in mind that students will still have different approaches to writing a skit about the same disease.

II. Assessment of student drafts and presentation

A. Providing feedback on student drafts

Writing, receiving comments, and rewriting is an effective way for students to revisit information in their skit and review information learned about their selected pathogenic disease. While writing the first, second, and final drafts, students receive feedback on their progress through the instructor’s comments. By reviewing the content and how it is delivered in the skits, the instructor will be able to gage how well the students can address information related to pathogenesis in a creative, relaxed, yet accurate manner.

One way for the instructor to encourage groups to use lay terms in their skits is to pose the question: “How would you convey this information to your future patients or family members who have a minimal scientific background?” This question challenges the student to relay information in a language that demonstrates an understanding beyond simple memorization. Based on scheduling, it is highly suggested that time be set aside during lecture — at least 30 minutes per week — for students to work on drafts with their group members and ask the instructor questions related to the assignment.

The first draft is submitted approximately two weeks after the introduction and brainstorming session, and is reviewed to ensure that all assignment guidelines have been properly addressed. After students receive comments on how to increase the quality of their first draft, a second draft will be required approximately one week later. The final draft is due one week after students receive comments from their second draft. To reduce the amount of time needed for reviewing drafts, instructors may reduce the number of drafts required. To grade groups on their effort to revise the skit throughout the entire process, the instructors can use a rubric for the ‘General Hospital’ assignment (first draft, second draft, and final submission; see Appendix 1).

B. Student presentations

The assignment was designed to have students limited to a ten-minute presentation during the lecture period. However, the presentation time limit may be adjusted based on the time constraints and number of students in the course. Larger classes may consider having groups film their skits outside of class, and posting their videos online via BlackBoard, Angel, Moodle, or other online resources for sharing with all students.

Submission of final drafts and supporting PowerPoint visuals for presentation should occur at least 24 hours before the presentation of skits. This will give the instructor time to review skits in advance and post visuals in a manner that can be readily accessible during the presentations — decreasing the amount of time needed for groups to transition between presentations.

During their performance, students can use a variety of materials to produce an entertaining skit. Examples include:

PowerPoint slides to show the background of each scene, such as the ‘General Hospital’ waiting room or the patient’s home.

Props, such as bedsheets and pillows over tables in the classroom to create the ‘patient bed’ and scrubs, stethoscopes, surgical masks, and a clipboard for the ‘medical staff’.

Examples of dialog from student skits

Chlamydia

Girlfriend: Nurse, Can I talk to you for a minute? (Leaves to talk to nurse) So, I was wondering what exactly would be affected because the doctor was concerned about me being pregnant.

Nurse: Well he was concerned because the bacteria can spread to the fallopian tubes and to your cervix… this could infect your baby’s eyesight and respiratory system.

Rabies

Woman: Ok, doctor, go ahead and give me the shots. How long is the treatment going to take? Will I infect my daughter?

Doctor: Rabies post-exposure vaccinations consist of a dose of human rabies immunoglobulin and four doses of rabies vaccine given on the day of the exposure, and then again on days 3, 7, and 14 and it’s given via injection in the arm. If you don’t get the vaccine and you are infected with rabies, you can only infect your daughter in the late stages of the disease and only through your saliva. So, Mrs. M., no biting anyone!

Tips

♦ Student may also present a skit where they (1) compare two different types of diseases, or (2) discuss the consequences associated with inadequate vaccination (e.g., bacterial vs. fungal meningitis, consequences from not having the Measles–Mumps–Rubella vaccination).

♦ The instructor can host a peer-review session for students to comment on drafts using an instructor- or student-generated rubric.

♦ It is highly suggested that students start to rehearse their skit during the revision of their second draft.

♦ Video recordings of student performances provide additional review for the instructor to assess student work and collect examples of presentations.

♦ Using an award system — a form of a mock ‘Oscars’ presentation — for ‘Best Skit’ allows for quality student work to be recognized and is a fun way to wrap up the assignment after presentations are complete.

Student feedback

“I never considered myself to be really creative. It was fun to do something different.”

“At first, I thought this was an easy assignment … it was much harder to write about a disease through a story than I expected!”

“The presentation of the assignment made us learn and understand the subject that we had better than other types of presentations because it was not like we were reading from cards. We really had to know what we presenting and rehearsing it so this made us really understand what we were talking about. It was also an easier way to understand the other presentations.”

“I showed the (video) presentation to my family … They couldn’t believe we had so much fun in Micro.”

CONCLUSION

The benefits of writing skits and role-playing allow students to study and strengthen their knowledge about topics related to pathogenesis and other topics in microbiology. This student-guided assignment also allows for instructors to transfer more responsibility and independence to the students regarding how they choose to present the information learned in the course, as well as allowing the instructor to cover pathogenesis in a form that varies with each new group of students. This exercise also provides students with the opportunity to creatively explore (1) their future roles as medical providers, and/or (2) interests related to diseases that they didn’t have an opportunity to research previously. Overall, through facilitation by the instructor, students are challenged to build upon knowledge obtained in lecture and transform information learned into a style accessible to individuals in the course and the general public.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Appendix 1: Rubric for Assignment

Appendix 2: Assignment Example 1

Appendix 3: Assignment Example 2

Acknowledgments

Project supported by the Davis Educational Foundation. Parts of this manuscript have been presented in: (1) The Sci-Fi Microbe Discovered at General Hospital: Creative Writing in Microbiology, ASpect Magazine, December 2009, Salem State University, and (2) The Sci-Fi Microbe Discovered at General Hospital: Using Creative Writing as a Teaching Tool in a Microbiology Course, May 2010, ASM-CUE Poster Presentation.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Rubric for Assignment

Appendix 2: Assignment Example 1

Appendix 3: Assignment Example 2