Abstract

Background:

Health literacy is a measure of an individual's ability to read, comprehend, and act on medical instructions. Limited health literacy can reduce the adults’ ability to comprehend and use basic health-related materials, such as prescription, food labels, health education pamphlets, articles, appointment slips, and health insurance plans, which can affect their ability to take appropriate and timely health care action. Nowadays, low health literacy is considered a worldwide health threat. So, the purpose of this study was to assess health literacy level in older adults and to investigate the relationships between health literacy and health status, health care utilization, and health preventive behaviors.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional survey of 354 older adults was conducted in Isfahan. The method of sampling was clustering. Health literacy was measured using the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA). Data were collected using home interviewing. Health status was measured based on self-rated general health. Health care utilization was measured based on self-reported outpatient clinic visits, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations, and health preventive behaviors were measured based on self-reported preventive health services use.

Results:

Approximately 79.6% of adults were found to have inadequate health literacy. They tended to be older, had fewer years of schooling, lower household income, and were females. Inadequate health literacy was associated with poorer general health (P < 0.001). Health literacy level was negatively associated with outpatient visits (P = 0.003) and hospitalization (P = 0.01). No significant association was found between health literacy level and emergency room utilization. Self-reported lack of PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) test (P < 0.001) and fecal occult blood test (FOBT; P = 0.003) was higher among individuals with inadequate health literacy than those with adequate health literacy. No significant association was found between health literacy level and mammogram in the last 2 years.

Conclusion:

Low health literacy is more prevalent in older adults. It indicates the importance of health literacy issue in health promotion. So, with simple educational materials and effective interventions for low health literacy group, we can improve health promotion in the society and mitigate the adverse health effects of low health literacy.

Keywords: Health care utilization, health literacy, health preventive behaviors, health status, older adults

INTRODUCTION

Health literacy is defined as an individual's capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make the appropriate health decisions.[1] The health literacy is a set of reading, listening, analyzing, decision-making skills, and ability to use of these skills in different health situations, and it does not necessarily depend on years of education or general reading ability.[2] Health literacy has been suggested as a worldwide problem and a global challenge for the 21st century.[3] In its recent report, the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) has declared health literacy as a major determinant for health and advises countries to create a multi-stakeholder Council on Health Literacy to monitor and coordinate strategic activities to enhance health literacy on this basis.[4]

Furthermore, WHO, in the Fifth World Conference on Health Promotion in Mexico, defined the health literacy as a cognitive and social skill which determines the incentive and ability of individuals to obtain, process, and use information to protect and improve their health. At this conference, it was stated that health literacy must be considered not only as an individual feature, but also as a health determinant and hygiene key in the population.[5]

Although it is still not clear how health literacy has an impact on health outcomes, many reasons suggest that inadequate health literacy will result in undesirable health outcomes.[6] According to American Center for Health Care Strategies, people with low health literacy are less likely to understand written and oral information provided by health professionals. These individuals have lower health status,[7] more outpatient visits and hospitalization,[8,9] lower self-care skills,[10] and problems with the use of preventive services,[11] and thus incur more medical costs.[12] A national widespread study conducted in America in 2003 estimated the prevalence of inadequate health literacy to be 48%, while just 11% of adults had high health literacy levels.[13] The only study conducted in Iran estimated the prevalence of inadequate health literacy to be 56.6% and only 28.1% of people had high health literacy.[14]

Limited health literacy is more prevalent among older adults, immigrants, illiterates, people with low incomes, low mental health, and people suffering from chronic diseases such as type II diabetes and hypertension. As a result, these groups are at risk for undesirable effects of low health literacy.[1,10,15–17] Several studies have also shown that low health literacy in older adults is associated with higher rates of mortality[18] and lack of preventive behaviors such as screening tests;[19] they take some health-risk behaviors[20] and low health literacy generally relates to unpleasant physical and mental health in this group.[21] According to official reports, approximately 6% of Iran's population aged above 60 years, which is equivalent to 4 million and 562 thousand people predicted that will increase to 26% of the total population.[22]

Since nowadays most education and health information has written formats and are more complex for ordinary people to understand,[23–26] to learn and understand health information requires a high reading, calculating, and decision-making skill, whereas studies have proven that most elders do not have sufficient expertise in these subjects. Furthermore, sensational and cognitive changes that occur with aging in the elderly affect their ability to read and understand the health information, which indicates a need for more attention to this problem.[27]

However, unfortunately, despite the greater importance of health literacy in quality of life and health promotion of older adults, this subject has been neglected in Iran and there are no statistics and evidence available on this subject. Therefore, based on the above-mentioned reasons, this study was conducted with three aims: to determine health literacy status, to determine the relation between health literacy and healthy behaviors, such as health care utilization, and preventive health care use in older adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In 2011, a cross-sectional survey was conducted among older adults aged 60–91 years in Isfahan city in Iran. Data and information were collected by home interviewing method. Cluster sampling was done in proportion to the size. In this study, health centers were considered as the clusters. Fourteen health centers (clusters) were randomly selected and 28 elderly people of every cluster were studied. Before the interview, the interviewer first explained the purpose of the survey, the study participants’ rights, and the risks and the benefits of participation. Further, a signed informed consent was obtained prior to the interview. Previous research suggests that illiterate subjects may feel embarrassed about not being able to read and may be uncomfortable taking the self-administered health literacy test, which requires the respondent to read and answer a variety of health-related questions.[28,29] So, we asked the respondents to read aloud a brief text as a way to identify those who were unable to read. Respondents who could not read at all were not asked to complete the self-administered health literacy test and received a zero score. To increase questioning coverage, some questionnaires were completed in two phases. Individuals were excluded from the study if it was determined that they were blind or had a severe vision problem not correctable with glasses, or had a cognitive impairment.

The Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) was used as a measure of health literacy for this study. The TOFHLA includes (1) a numeracy section with items assessing the participant's ability to understand and act on numerical directions of the sort that might be given by a health care provider or a pharmacist. The section contains 10 scenarios based on real-life situations and was presented through a series of prompt cards. The tasks involved included reading information on appointment slips, following directions to take medication, using information on time intervals to plan when to take medicines, and calculating eligibility for financial aid. This part had a total of 17 questions. Weighted scores ranged from 0 to 50, representing the number of correct answers. (2) A reading comprehension section that comprised a 50-item test used to measure the ability to read and understand three prose passages. These passages were selected from instructions prepared for upper gastrointestinal examination, patients’ rights and responsibilities in Medicaid, and a standard hospital informed consent. Participants obtained a score of 0–50 according to the number of correct answers. The sum of the two sections yields the TOFHLA score, which ranges from 0 to 100.

Scores are classified and interpreted as follows: 0–59, inadequate functional health literacy; 60–74, marginal health literacy; 75–100, adequate functional health literacy. Furthermore, it had high internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha = 0.95). In the current study sample, the internal reliability of the scale was 0.79 for numeracy section and 0.88 for reading comprehension section. All participants answered a series of questions on demographic characteristics (age, gender, marriage status, educational attainment, household income). They were asked to rate their general health on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good). Health care utilization was measured by asking the respondents to answer yes or no to (1) whether they had at least an outpatient visit in the previous 3 months, and if yes, what was the reason; (2) whether they ever visited an emergency room (ER) in the last year; and (3) whether they were ever hospitalized in the previous year. Preventive health care use was measured by asking the respondents to answer yes or no to (1) whether they had fecal occult blood test (FOBT) test in the last year, (2) whether female respondents ever had a mammogram in the last 2 years, and (3) whether male respondents had PSA test in the last year.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS v. 18 for data analysis. Descriptive statistics (mean, SD, and percentage) were performed to examine the level of health literacy in the sample as a whole and socio-demographic attributes were evaluated. For descriptive analysis, age was classified into 60–65 years, 66–70 years, 71–75 years, 76–80 years, 81–85 years, and more than 85 years old. Significant differences in health literacy across some socio-demographic groups (age, educational attainment, household income) were evaluated using the Spearman's correlation and some other socio-demographic groups (gender, marriage status) using Mann–Whitney test. The associations of health literacy with health status, healthcare utilization, and preventive health care uses were assessed using the Spearman's correlation, Kruskal–Wallis, and Mann–Whitney test.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample

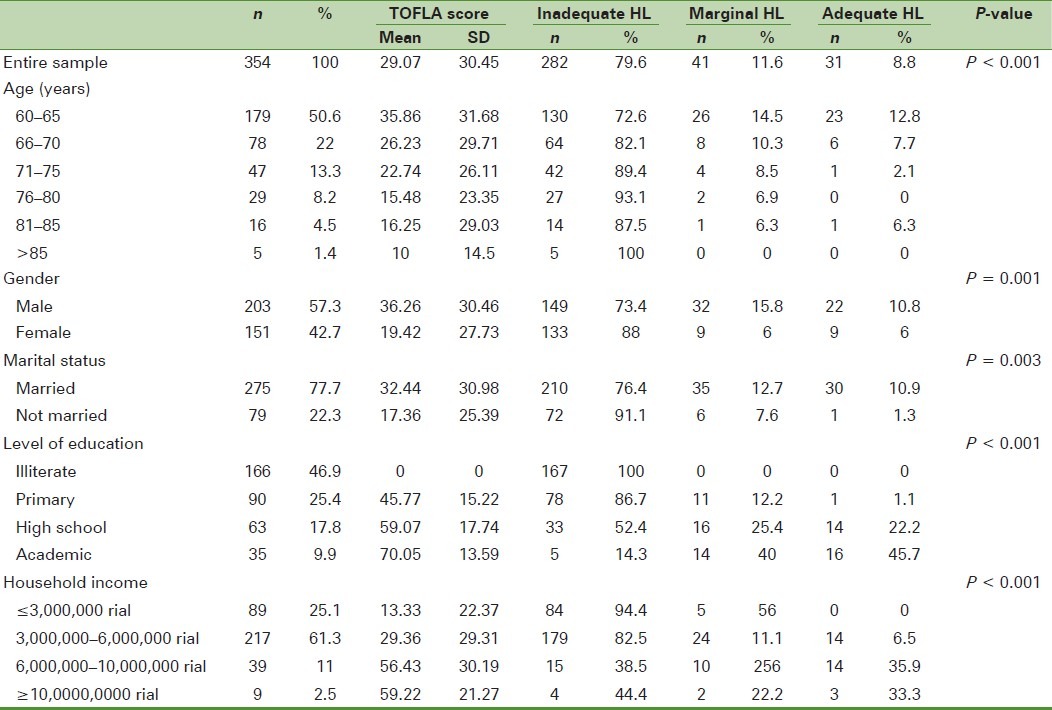

Respondents ranged in age from 60 to 91 years, with a mean age of 67 ± 6.97 years. The sample contained more men (57.3%). The largest group of respondents was of 60–65 years (50.6%). Most of the respondents were married (77.7%), illiterates (46.9%), and had average ($300–600) household income [Table 1].

Table 1.

Socio-demographic attributes and health literacy level of older adults in Isfahan, Iran, 2011

The mean health literacy score of the sample was 29/07 ± 30/45 of 100. Of the 354 participants, 79.6% were classified as having inadequate health literacy, 11.6% as having marginal health literacy, and only 8/8% had adequate health literacy. In this study, Spearman's correlation test indicated significant variation in health literacy by age, educational attainment, and household income; also, Mann–Whitney test statistically showed significant variation in health literacy by gender and marital status. So, inadequate health literacy was more common in older aged, less educated, lower household income people, absolute individuals, those whose spouses were dead, and women [Table 1].

Health literacy, health status, and use of health services

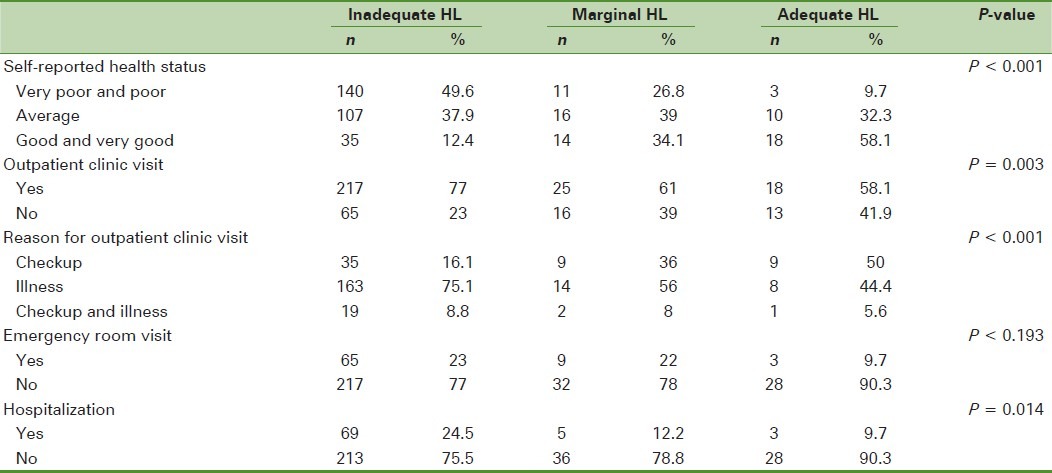

Around 37/6% of subjects perceived their general health in moderate. Table 2 shows that 12% of individuals in the “inadequate” compared with 58% of those in the “adequate” health literacy category reported being in good health. About 73% of them reported at least one outpatient visit in the past 3 months and the reason for 71% of the referral was illness and health problems. Only 20% of the participants’ referral had been just for the checkup or screening tests. 21% had visited an ER, and 6.9% had been hospitalized in the previous year [Table 2]. The Spearman's correlation showed that health literacy level was positively associated with self-rated health status, and Mann–Whitney test indicated that health literacy level was negatively associated with outpatient visits and hospitalization. Kruskal–Wallis test showed a statistically significant relationship between the health literacy levels and the reason for an outpatient visit. It means that individuals with a higher health literacy level had referred more for checkup and screening tests, while older adults with lower health literacy had referred more because of their illness and health problems. No significant association was found between health literacy and ER utilization.

Table 2.

Health status, health care utilization, and health literacy in older adults in Isfahan, Iran, 2011

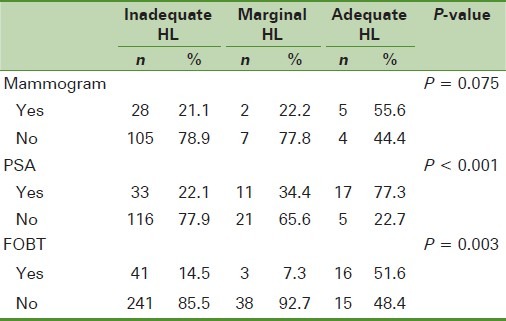

Health literacy and preventive health behaviors

According to the participants’ reports, only 23/2% of elder women had done mammogram in the last 2 years, and only 30% of men had done PSA test for prostate cancer screening in the last year and only 19% of subjects had done the FOBT for colorectal cancer screening in the last year. The Mann–Whitney test showed that health literacy level was positively associated with the use of preventive health services. It meant that self-reported lack of screening tests was higher among individuals with inadequate health literacy than those with adequate health literacy. This study was found no statistically significant association between health literacy and mammogram [Table 3].

Table 3.

Preventive health behaviors and health literacy in older adults, Isfahan, Iran, 2011

DISCUSSION

Research results showed that the level of health literacy among older adults was very low. In this study, around 79% of this people had inadequate health literacy. Due to the higher incidence of the chronic diseases and the subsequent requirements for the ability to self-care skills, and also special requirements to the necessity of screening tests in the elderly, health literacy in this group is one of the most important issues. According to many studies, health literacy has a direct impact on the above-mentioned factors. Therefore, this range of inadequate health literacy in the elderly is a warning to the authorities, policy makers, and custodians of the health sector.

Results of various studies in other countries also show a range of inadequate health literacy. By comparison, only 3% of American adults surveyed in the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) had a high level of health literacy.[13] Furthermore, in Wagner and colleagues’ study, 30% of the elderly people had inadequate health literacy.[30] In the Baker and colleagues’ study, inadequate health literacy had been reported as 24/5% for older adults.[18] Wolf and colleagues estimated health literacy to be 22/2% in the elderly.[20] Orlu and colleagues in a systematic study on 85 papers reported that 26% of individuals had inadequate and 20% of them had marginal health literacy.[31] In Tehrani and colleagues’ study, inadequate health literacy had been reported to be about 56/6%.[14]

Similar to the findings of previous health literacy studies,[1,13,30,32,33] older age, poorer educational attainment, and lower income were found to be associated with lower levels of health literacy in older adults. Also, adequate health literacy was more common among married people than the other group of them.

In this study, the prevalence of inadequate health literacy was higher in women than in men. The lower level of health literacy among women in this study is probably due to their low educational level. Similar to our study, Lee and colleagues reported in their study that the means of health literacy scores of men were more than those of women.[34] However, unlike the present study, in Wagner and colleagues’ research, men had more health literacy levels than women.[30] In other studies, there was no association between health literacy and gender.[14,18]

Our findings indicate that health literacy was associated with good self-rated health status. The magnitudes of these associations were large and clinically important, and this result may be because of prevalence of chronic disease among subjects with inadequate health literacy. Similar to other studies[9,21,33,35,36] of highly selected patient populations, because our study was population based, it should be less subject to selection bias than previous studies that enrolled people at the time they were seeking medical care.

Our findings are also consistent with previous studies showing that health literacy is an independent predictor of physician visits and hospitalization.[8,9] Current evidence on health literacy as a predictor for health care utilization is different. Baker and colleagues found that patients in outpatient clinics who had inadequate health literacy were more likely to have physician visits and be hospitalized,[8,9] while other studies did not find health literacy to be associated with health care utilization.[32,37] According to these results, it can be concluded that low health literacy mainly causes repeated and unnecessary referral to the doctor and more length of stay in the hospital. This in turn leads to increased costs and thereby losses on part of the health sector budget. In this study, a significant relationship between health literacy and use of ER was not found, which is consistent with the results of a previous study.[34]

The results show that the reasons for individuals’ outpatient visits are thoroughly different. This means that participants with inadequate health literacy had more outpatient visits because of their illnesses and health problems, but individuals with adequate health literacy had more outpatient visits for checkups and screening tests. Perhaps the reason is that people with a high health literacy level have more knowledge about screening tests and the importance of them. So, these factors rather than the diseases caused these subjects go to a physician for checkups, as the other findings of the research confirmed these results showing that individuals with a high health literacy level were more willing to do the screening tests such as PSA and FOBT. In this study, although the mean scores of health literacy in subjects who had had a mammogram were more than the others, this difference had no meaning statistically.

Scott and colleagues found that older adults with a higher health literacy level had done more screening tests compared to individuals with low health literacy.[11] Contrary to our findings, in their research, there was a significant association between health literacy and mammography, So, older women with adequate health literacy had done mammogram more than the others. This difference is probably due to the lack of awareness in women about the necessity to perform this test, even in old age. Whereas according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of America, mammography in the age group 40–74 years and especially older than 50 years can play an effective role in reducing the mortality from breast cancer.[38]

Considering these findings, educational interventions in people with inadequate health literacy appear to be essential to increase the participation of the elderly for screening tests in this age group because often critical and timely diagnosis will present more opportunities to the physicians and patients for treatment.

It should be noted that in this study, unlike a majority of surveys, we used the full rather than the short TOFHLA (S-TOFHLA) and conducted testing face-to-face rather than in a group setting. Furthermore, considering that our study was a population based one, it should be less subject to selection bias than previous studies conducted on people at the time they were seeking medical care. The various limitations to our study should be noted. Since the study has been done among older adults (individuals 60 years and older), the results cannot be generalized to the other age groups. Therefore, further studies are needed to assess the effects of health literacy on various aspects of health in the subject population. Only self-rated measures of health status, health care utilization, and health preventive behaviors were examined in the study. Although the results of different studies[39,40] showed most of the information provided by the persons to be consistent with the actual data and evidence of real recorded information, it may be subject to recall bias or memory failure.

In addition, given that in this research, willingness to participate in the study was considered as an entry criterion, it is likely that older adults who wish to participate in the study had higher levels of health literacy, and it can be considered as a limitation of this study. Overall, the findings of this study as the first study in Iran which assessed the relationship between health literacy levels and different aspects of health can be used in micro and macro levels and will have eventually a significant impact on improving health and in health promotion. This study indicated the high prevalence of inadequate health literacy among older adults, and it shows the necessity of giving more attention to this subject in health promotion programs. To achieve this goal, different sectors such as media, which is one of the most important sources for reception of health information, and health system that has a direct impact on quality of health care need to collaborate and provide appropriate information for clients. To develop proper and responsive interventions, future studies should discern how adults with lower health literacy recognize health issues to make a comprehensive and simple educational material for them, and also they should identify barriers to seeking out appropriate health care services. In addition, interventions are needed that can help physicians and other health care professionals recognize the special needs of clients with limited health literacy to make effective communication between health professionals and patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank the board of research in health education and health promotion department of University of Isfahan for their support and assistance.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA. Health Literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, D.C: Institute of Medicine of The National Academies; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sihota S, Lennard L. London: National Consumer Council; 2004. [Last accessed on 2012 Jan 24]. Health literacy: Being able to make the most of health; p. 11. Available from: http://www.ncc.org.uk/nccpdf/poldocs/NCC064_health_literacy.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nutbeam D, Kickbusch I. Advancing health literacy: A global challenge for the 21st century. Health Promotion Int. 2000;15:183–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. CSDH: Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kichbush I. Sarmast H, Moosavian poor M, translators. Health literacy and discussion on health and education. Publication of Health Promotion and Healthy Lifestyle Association. 2006;2:4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams MV, Parker RM, Baker DW, Coates W, Nurss J. The impact of inadequate functional health literacy on patients’ understanding of diagnosis, prescribed medications, and compliance. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:386. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Health Education Standards: Achieving Health Literacy. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 1995. Joint Committee on National Health Education Standards. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Scott T, Parker RM, Green D, et al. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1278–83. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS, Nurss J. The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1027–30. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, Wang F, Osmond D, Daher C, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002;288:475–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care. 2002;40:395–404. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard DH, Sentell T, Gazmararian JA. Impact of health literacy on socioeconomic and racial differences in health in an elderly population. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:857–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Yin J, Paulsen C, White S. The health literacy of America's adults: Results from the 2003 national assessment of adult literacy. Washington, DC: US Department of Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tehrani Banihashemi SA, Haghdooost A, Alavian M, Asgharifard H, Baradaran H, Barghamdi M, et al. Health literacy in five province and relative effective factors. Strides In Development of Medical Education. Journal of Medical Education Development Center of Kerman University of Medical Sciences. 2007;1(4):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, Nurss JR. Relationship of functional health literacy to pationts knowledge of their chronic disease: A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:166–72. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalichman SC, Rompa D. Functional health literacy is associated with health status and health related knowledge in people living with HIV-AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25:337–44. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200012010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalichman SC, Benotsch E, Suarez T, Catz S, Miller J, Rompa D. Health literacy and health- related knowledge among persons living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:325–31. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA, Gazmararian JA, Huang J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly person. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1503–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White SH, Chen J, Atchison R. Relationship of preventive health practices, and health literacy. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32:227–42. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and health risk behaviors among older adults. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1946–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Islamic Republic News Agency. 2007. [Last accessed on 2007 Jun 03]. Social; Elderly. [On-line]. Available from: http://www. irna.com/en/news/line-8.html .

- 23.Hearth-Holmes M, Murphy PW, Davis TC, Nandy I, Elder CG, Broadwell LH, et al. Literacy in patients with a chronic disease: Systemic lupus erythematosus and the reading level of patient education materials. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:2335–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zion AB, Aiman J. Level of reading difficulty in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists patient education pamphlets. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:955–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis TC, Bocchini JA, Jr, Fredrickson D, Arnold C, Mayeaux EJ, Murphy PW, et al. Parent comprehension of polio vaccine information pamphlets. Pediatrics. 1996;97:804–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis TC, Mayeaux EJ, Fredrickson D, Bocchini JA, Jr, Jackson RH, Murphy PW. Reading ability of parents compared with reading level of pediatric patient education materials. Pediatrics. 1994;93:460–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wengryn M, Jackson Hester E. Pragmatic Skills Used by Older Adults in Social Communication and Health Care Contexts: Precursors to Health Literacy. Contemp Issues Commun Sci Disord. 2011;38:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parikh NS, Parker RM, Nurss JR, Baker DW, Williams MV. Shame and health literacy: The unspoken connection. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;27:27–39. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf WS, Williams MV, Parker RM, Parikh NS, Nowlan AW, Baker DW. Patients’ shame and attitudes toward discussing the results of literacy screening. J Health Commun. 2007;12:721–32. doi: 10.1080/10810730701672173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Von Wagner C, Knight K, Steptoe A, Wardle J. Functional health literacy and health-promoting behaviour in a national sample of British adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:1086–90. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of Limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:175–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho YI, Lee SY, Arozullah AM, Crittenden KS. Effects of health literacy on health status and health service utilization amongst the elderly. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1809–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gazmararian JA, Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Scott TL, Green DC, et al. Health literacy among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;281:545–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SY, Tsai TI, Tsai YW, Kuo KN. Health literacy, health status, and healthcare utilization of Taiwanese adults: Results from a national survey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:614. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jovic-Veanes A, Bejgovic-Mikanovic V, Marinkovic J. Functional health literacy among primary health-care patients: Data from the Belgrade pilot study. J Public Health. 2009;31:490–5. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tokuda T, Doba N, Butler JP, Passche-Orlow MK. Health literacy and physical and psychological wellbeing in Japanese adults. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:411–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arozullah AM, Lee S-YD, Khan T, Kurup S, Ryan J, Bonner M, Soltysik R, Yarnold PR. The roles of low literacy and social support in predicting the preventability of hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:140–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. [Last accessed on 2011 Mar 03]. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/screening/breast/HealthProfessional .

- 39.Bush TL, Miller SR, Golden AL, Hale WE. Self-report and medical record report agreement of selected medical conditions in the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1554–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.11.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simpson CF, Boyd CM, Carlson MC, Griswold ME, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Agreement between self-report of disease diagnoses and medical record validation in disabled older women: Factors that modify agreement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:123–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]