Abstract

Background:

Colorectal cancer is one of the most important and most common cancers and the second leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide. Every year, nearly 1 million new cases of colorectal cancer are recognized around the world and nearly half of them lose their lives due to the disease. The statistics reveal shocking incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer, therefore secondary prevention of this cancer is important and research has shown that by early diagnosis 90% of patients can be treated. Among the colorectal cancer screening tests, fecal occult blood test (FOBT) takes the priority because of its convenience and also low cost. But due to various reasons, the participation of people in this screening test is low. The goal of this study is to assess the factors that affect participation of population at average risk in colorectal cancer screening programs, based on health belief model structures.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional survey of 196 individuals, more than 50 years old, was conducted in Isfahan. Ninety-eight people of the target group were selected from laboratories while they came there for doing FOBT test; the method of sampling in this group was random sampling. The method of data collection in the other 98 individuals was by home interview and they were selected by cluster sampling. The questionnaire used was based on health belief model to assess the factors associated with performing FOBT. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistical methods.

Results:

The mean score of knowledge in the first group was 48/5 ± 11/7 and in the second group was 36/5 ± 19/3. Individuals in the first group were more likely to be married, had more years of schooling, and better financial status. There were significant relationships between knowledge (P<0.001), perceived susceptibility (P<0.001), perceived severity (P<0.001), perceived barriers (P<0.001), and self-efficacy (P<0.001) in the two groups. There was no significant association between the perceived benefits in the two groups. Those people who have had FOBT test in last year in each group reported better score of Health Belief Model model structures.

Conclusion:

According to this study, it seems that there is an urgent need to pay more attention to this disease and its prevention through screening. With a better understanding of factors affecting the test, it can be a useful step to reduce the rate of death and costs, and improve the community health outcomes.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, fecal occult blood testing, HBM model

INTRODUCTION

The burden of cancer is the second-leading cause of death. More than 20 million people are living with cancer and 7 -million people die annually.[1] In some countries where people follow the western lifestyle, approximately half and 25% of all deaths occur due to cardiovascular diseases and cancer, respectively. As a direct result of that, cancer is accounted as an important problem of public health and influences governments.[2]

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most important and prevalent cancers, which is considered as a second cause of death of humans worldwide due to cancer[3,4] as around 1 million new cases of this cancer are recognized annually and approximately half of them lose their lives due to this disease.[5] This disease, after lung cancer, is also recognized as the second most common cancer across the United States of America,[6] and according to statistics in 2001, roughly 11% of deaths due to cancers was caused by it.[7] This cancer is the third cause of death[8] in Iran, and digestive cancers are more prevalent cancers among men and the second most common cancers among Iranian women, after breast cancer.[9]

According to reports, the incidence of CRC in Iran has undergone a rising trend during the last 25 years, but the available information shows that this disease affects the younger population of Iran, compared with western countries.[10] The shocking statistics of prevalence and deaths due to CRC show how important it is to prevent this cancer.[11] For those diseases where primary prevention is impossible, secondary prevention is preferred.[12] For CRC, there is no way for primary prevention. Early detection can inhibit the spread of cancer and make the treatment easier.[11] Since this cancer has a slow progression trend, 90% of patients would be cured if detected in early stages.

Regular screening is one of the most valuable and important methods for secondary prevention of this disease.[13,14] Among the screening methods for this cancer, fecal occult blood test (FOBT) is preferred to other methods because of the ease with which it is done and its low cost.[15] Based on the CRC screening program in USA, firstly, people who are at moderate or high risks of cancer are taken for FOBT; if the result is positive, more accurate tests would be taken, including colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy.[16,17] Unfortunately, in spite of the screening program's effect on early detection and treatment of cancer, large number of people at risk do not participate in the screening program.[18] According to studies, Due to the ability to treat more than 90% of patients with colorectal cancer in early stages, only 40% of them at this stage of the disease diagnosed and treated.[19]

Unfortunately, the participation of people in screening programs of CRC is low in Iran and there is not any accurate statistics of this participation. Due to the growing prevalence of this disease during the past few decades and, in addition, lack of research on the factors related to non-participation of people at risk in the screening tests, the necessity of this research is sensed.

A study conducted by James et al. in 2002, aimed to assess and evaluate the role of perceived barriers and benefits of the screening test of CRC, showed that there is a significant relationship between these screening tests.[7] Bruce et al. conducted a study in the year 2003 with the intention of investigating barriers and obstacles in the way of doing the FOBT, which has been done as a quantitative research, and they showed that lack of awareness, poor communication skills, low self-efficiency, and low perceived sensitivity have a direct relationship with lesser participation of people in this test.[17] Different researchers around the world rely on some or the other model of the health belief model in order to recognize the influencing factors of CRC screening tests.

This research has been done with all HBM model structures for assessing factors that affect participation for FOBT test by people over 50 years in Isfahan. By better identifying this problem, we can step toward improving health services, increasing public participation in cancer screening programs, and decreasing the prevalence and mortality due to this disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a descriptive, analytical type of study, which was conducted on 196 people, over 50 years of age, in Isfahan in order to detect relevant factors for the CRC screening test. Subjects in this study were divided into two groups of 98 persons in each group. The first group included persons who referred the diagnostic laboratories in order to take the FOBT, and the next group consisted of people who, contrary to the other group, did not refer the laboratories and had been surveyed by home interviews. In order to collect the information from the first group, 98 people who referred Navab Safavi, Mahdieh, Dr. Baradaran laboratories, and Al-Zahra Hospital for taking FOBT or for returning the corresponding test kits back were selected randomly.

Subjects of the second group were selected by cluster sampling. People in eight clusters, with 12–13 persons over 50 years in each, were asked to complete a questionnaire. Inclusion criteria for the study were subjects over 50 years of age, not being at high risk of CRC, absence having colorectal cancer in subject and his first degree relatives, with low risk of benign glands of colon, with mental and physical capability to answer the questions, and those willing to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were people who gave incomplete answers for the questions. The information collecting method with questionnaires was based on the health belief model structures.

The questionnaires were tested for content and logical validity. Therefore, after studying resources, books, and papers, questionnaires were prepared and assessed by some gastroenterologists and university members. The test of Alpha Cronbach was used with the validity coefficient of 95% and significance level of 0.05% after completion of 40 questionnaires in order to evaluate their reliability. The evaluated reliability of different parts of the questionnaire was between 0.71 and 0.89.

The corresponding figure for the whole questionnaire was calculated as 0.86. The questionnaire consisted of 53 -questions given as nine sections as follows: 7 questions for evaluating personal profile; 10 questions for evaluating awareness levels about CRC and its screening methods with scores 1 for correct answers and 0 for “false” or “I don’t have any idea” replies; 4 queries for assessing perceived susceptibility; 5 questions to evaluate perceived severity; 5 queries for evaluating perceived benefits; 12 queries for assessing perceived barriers by answers in five choices Likert scale [absolutely agree (score 1), agree (score 2), no idea (score 3), disagree (score 4), and completely disagree (score 5)]; 5 questions for measuring perceived self-efficiency with answers in four options Likert scale [never (score 1), low (score 2), most of the time (score 3), and always (score 4)]; 2 queries to evaluate work guidance which were asked in multiple choice format, such as practitioner's recommendation, health staffs, radio, television, and so on. Furthermore, there were two other questions relating to history of performance of this test in last year and its future intention.

The outcome scores from each structure were evaluated in scales of 0–100. All questionnaires was performed by researcher interviewing method and the results were analyzed by SPSS 18 software, descriptive statistics, Chi-square tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), Mann–Whitney, and Kruskal–Wallis tests.

RESULTS

Among the subjects who referred to the laboratories, 56.9% were females and 43.1% were males, and their average age was 64.3 ± 7.54 years, while the second group consisted of 58.7% females and 41.3% men with an average age of 63.09 ± 7.81 years. There were no significant statistical differences between the two groups with regard to age and gender on performing the independent t-test and Chi-square test, respectively. Although the majority of people in both the groups were married, greater number of widows and divorced people in the non-referred group was shown by Chi-square test (P=0.041). Also, this test revealed that most of the people who referred to laboratories had medium and higher medium economic status (P=0.001), and they were more educated (P=0.047) compared with non-referred people to laboratories.

In the non-referred group, just 13.3% of people took an FOBT during the last year, which was a remarkable significant difference compared with the referred group with 60.8% participation in this test (P<0.001). The most important cited cues to action in the referred group to laboratories were doctor's recommendation (54%) and doing annual checkup (29%). Regarding the sources of information for carrying out FOBT and prevention of CRC in this group, 58%, 41.8% and 27% of people reported radio and television, health staffs, and family, respectively.

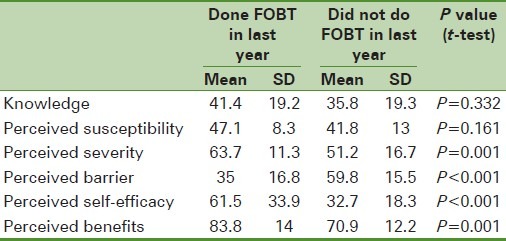

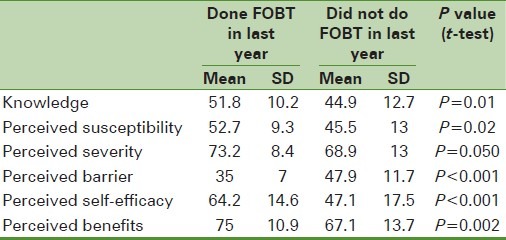

The results illustrated in Table 1 show that people in the referred group to laboratories who had a history of test during last year compared with those who did not have this record gained better scores significantly and also reported lower obstacles about awareness, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived self-efficiency, and perceived benefits. In the non-referred group to laboratories, those who had the FOBTs done during last year compared with those who did not record this test at the same time gained better scores and also had lower perceived barrier and perceived severity, -perceived self-efficiency, and perceived benefits [Table 2].

Table 1.

Comparison of the mean scores of the health belief model constructs about the history of fecal occult blood test in last year in the non-referred with the laboratory referred group

Table 2.

Comparison of the mean scores of the health belief model constructs about the history of fecal occult blood test in last year in the referred with the laboratory groups

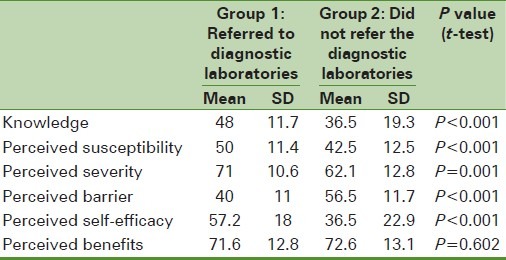

However, there was no significant statistical difference between the awareness levels and perceived susceptibility in both the groups. Table 3 illustrates the scores of different structures of health belief models gained by the studied people in both the groups. The results show that referred group to laboratories compared with the second group gained higher scores of awareness of CRC and its prevention methods, perceived sensitivity, perceived intensity, and perceived self-efficiency. The non-referred group also reported more perceived barriers significantly. There was no significant statistical difference of perceived benefits in both the groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of the mean scores of the health belief model constructs about the history of fecal occult blood test in last year in both laboratory referred and non-referred groups

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

According to recommendation of World Health Organization and the American Cancer Society,[7] all people over 50 years of age are at risk of CRC and should have an FOBT done annually and colonoscopy test done every 5 years.

In this research, two different groups of people over 50 years of age were surveyed in the city of Isfahan. The first and second groups consisted of referred and non-referred people to laboratories, respectively, in order to take FOBT. In our country, Iran, where there is high risk of this cancer and its death rate, the screening program for this disease is not performed.

As the results of this research show, more than half of the people in the first group referred to the laboratories on the advice of their practitioners and not because of taking screening test. The results also illustrate that 13.3% of non-referred people to laboratories took this test during last year, which was lower than the corresponding figure of 23% reported by Aimi and James[20] in USA. The results of this study show a significant statistical difference between FOBT taken during last week and awareness level, perceived sensitivity, perceived intensity, perceived barriers, and perceived self-efficiency in people at risk.

Regarding the role of awareness on the test and also the roles of radio and television, health staffs, and practitioners in informing and guiding people about screening tests, the necessity of educational interventions in the society and retraining programs for health staffs is paramount. Other notable results of this research show the remarkable role of physicians in improving and raising the level of FOBT in people at moderate risk who account for a high percentage of the population.

As shown in Table 1, the referred group compared with non-referred group gained higher scores of awareness, sensitivity, perceived intensity, and self-efficiency. Contrary to the referred group, the second group had higher significant scores of perceived obstacles. This reveals that educational interventions based on health belief models, by raising awareness and reducing perceived obstacles, play a major role in increasing early diagnosis levels of CRC, its successful treatment, and improving health levels of the society.

It should be emphasized that there was no significant statistical relationship between age and taking FOBT during last year. The study performed by Satya et al.[20] showed that people's participation level in this test increases with increase in age. The same results were also obtained in other studies.[21–28] No significant relationship was observed between the family history of cancer and taking screening test for CRC, while a significant relationship was obtained by Satya et al.[20]

Women were found to have better history of taking higher levels of FOBT, which is compatible with the results of Krishnan's study[29] as well as those of other researches.[30,31] However, some documents show greater participation of men than women in screening programs.[32–36] The referred group in this research also showed better education and economic status, which are consistent with the results of Ching-Ti et al.[37] Ching-Ti as well as other researchers reported that poor education and low economical status result in reduced participation in this test as it influences the awareness levels.[20–41]

In this study, the referred people to laboratories, like those who have taken FOBT during last year, compared with the other group and those people who did not record this test before, obtained a better score of awareness level of CRC and its prevention. These results are consistent with other the results of other studies.[23,27,36,38,42,43,44–50]

Physicians in this study were reported as the most important source of guidance for taking FOBT, which is consistent with the results of other studies.[23,39,49–51] Perceived sensitivity in the referred group to laboratories was significantly higher than that of the second group, which is compatible with the results of the same studies.[23,26,27,45,52–54]

Regarding the perceived intensity, the referred people and those who took FOBT during the last year gained higher scores significantly. Zhing et al. also reported the same results.[55] The obtained score of perceived obstacles was higher in the non-referred group and those who did not record this test during last year, which is in consonance with the results of other studies.[36,47,55–57]

From the viewpoint of perceived self-efficiency, the referred group to laboratories and those who recorded FOBT during last year gained higher scores. The study of Van Winger and colleagues showed that higher perceived self-efficiency results in higher participation in screening for CRC. This research shows high health literacy leading to increase in self-efficiency and participation levels.[58] People who took this test during last year obtained better significant scores of perceived benefits than those who did not record this test. Other studies carried out have reported significant relationship between FOBT and perceived benefits.[26,47,55,59]

Since this research was done as a comparison method in both the groups, its confidence coefficient was increased and more valid results were obtained. Review of literature revealed that no studies have used this method. Also, in this study, all structures of health belief model were used and more comprehensive results were obtained. There was no study carried out in this field in Iran and all studies have been carried out in other places of the world, just focusing and concentrating on one or some of the structures of this model. So, this research is the first one in which specific perceived self-efficiency (perceived self-efficiency from the ability of taking FOBT) and health belief model in order to take screening test for CRC were together used.

Regarding the statistics, the age at risk of CRC in Iran is lower than the world average, and since the studied people in this research included those over 50 years, the necessity of other similar studies among people of lower age group is sensed. To sum up, it can be simply concluded that health belief models are good predictors of taking FOBT as a screening method for CRC in people who are at risk for this disease. The necessity of conducting widespread and comprehensive educational programs concentrating on health belief models in this group of people and also retraining practitioners and other health staffs in the society is illustrated in order to increase the people's participation level in taking this test as an easiest, more inexpensive, and the first way in early recognition of CRC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grateful thanks are due to the Board of Research in Health Education and Health Promotion Department of University of Isfahan and the heads of diagnostic laboratories who spared no expense in this research as it is a health problem of the society.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was supported by funding from Isfahan university of medical sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1. [Last accessed on 2005]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2005/pr_wha05/en,

- 2.Boyle P, Langman J S. ABC of colorectal cancer: Epidemiology. BMJ. 2000;321:805–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7264.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Last accessed on 2006]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en,

- 4.Chu KC, Tarone RE, Chow WH. Temporal pattern in colorectal cancer incidence, survival and mortality. JNCI. 1994;86:997. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.13.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone WL, Krishnan K, Campbell SE, Qui M, Whaley SG, Yang H, et al. Tocopherols and the treatment of colon cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1031:223–33. doi: 10.1196/annals.1331.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Favsy AS, Brvnvald S, Kasper DL, Havsr SS. Harrison Principles of Internal Medicine. In: Khalvat S, Montazeri M. S, translators. 15th ed. Tehran: Arjomand Publication; 1380. [Google Scholar]

- 7.James AS, Campbell MK, Hudson MA. Perceived barriers and benefits to colon cancer screening among African Americans in North Carolina: How does perception relate to screening behavior? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:529–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alizade M. The age-adjusted rates of cancer in Fars province cancer registry. Thesis, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, School of Health. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadjadi A, Nouraie M, Mohagheghi MA, Mousavi-Jarrahi A, Malekzadeh R, Parkin DM. Cancer Occurrence in Iran in 2002, an International perspective. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2005;6:359–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.khabazkhoob Mehdi, Mohagheghi Mohammad Ali, Jarrahi Alireza Mosavi, Foroushzadeh Ali Javaher, Far Mohsen Pedram, Moradi Ali, et al. Incidence rate of gastrointestinal tract cancers in Tehran – Iran (1998-2001) Journal of Gorgan University of Medical Sciences. 2010;11(4):44–50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fyps VJ, Sandoz KJ, Mark FJ. Gastroenterologists. In: Namavar H, front L, translators. Nursing-Surgery. 6th ed. Tehran: Chehr publication; 1379. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masner J, Kramer S. Introduction to Epidemiology. In: Janghorbani M, translator. 2nd ed. Kerman: Kerman Farhangi Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures, 2000, American Cancer Society Atlanta. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O’Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternerg SS, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandi P, Brooks D, Calle J, Cokkinides V, et al. Colorectal Cancer Facts and Figures 2008-2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, Ederer F, Geisser MS, Mongin SJ, et al. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1603–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brouse CH, Basch CE, Wolf RL, Shmukler C, Neugut AI, Shea S. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening with fecal occult blood testing in a predominately minority urban population: A qualitive study. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1268–71. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito H, Soma Y, Koeda J, Wada T, Kawaguchi H, Sobue T, et al. Reduction in risk of mortality from colorectal cancer by fecal occult blood screening with immunochemical hemagglutination test. A case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1995;61:465–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shafayan B, Keyhani M. Epidemiological evaluation of colorectal cancer. Acta Med Iran. 2003;41:156–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satia JA, Galanko JA. Demographic, behavioral, psychosocial, and dietary correlates of cancer screening in African Americans. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(4 Suppl):146–64. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meissner HI, Yabroff R, Dodd KW, Leader AE, Ballard-Barbash R, Berrigan D. Are patterns of health behavior associated with cancer screening? Am J Health Promot. 2009;23:168–75. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07082085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheffet AM, Ridlen S, Louria DB. Baseline behavioral assessment for the New Jersey health Wellness Promotion Act. Am J Health Promot. 2006;20:401–10. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.6.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shokar NK, Carlson CA, Weller SC. Factors Associated with racial/ethnic differences in colorectal cancer screening. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21:414–26. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grenier KA, James AS, Born W, Hall S, Engelman KK, Okuyemi KS, et al. Predictors of fecal occult blood test (FOBT) completion among low-income adults. Prev Med. 2005;41:676–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel P, Forjuoh SN, Avots-Avotins A, Patel T. Identifying opportunities for improved colorectal cancer screening in primary care. Prev Med. 2004;39:239–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinberg DS, Turner BJ, Wang H, Myers RE, Miller S. A survey of women regarding factors affecting colorectal cancer screening compliance. Prev Med. 2004;38:669–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C, Basch CE, Yamada T. An evaluation of colonoscopy use: implications for health education. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25:160–5. doi: 10.1007/s13187-009-0024-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffith KA. Biological, psychological and behavioral, and social variables influencing colorectal cancer screening in African Americans. Nurs Res. 2009;58:312–20. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181ac143d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ananthakrishnan AN, Schellhase KG, Sparapani RA, Laud PW, Neuner JM. Disparities in colon cancer screening in the medicare population. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:258–64. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGregor SE, Hilsden RJ, Li FX, Bryant HE, Murray A. Low uptake of colorectal cancer screening 3 yr after release of national recommendations for screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1727–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh SM, Paszat LF, Li C, He J, Vinden C, Rabeneck L. Association of socioeconomic status and receipt of colorectal cancer investigations: A population based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2004;171:461–5. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glenn BA, Chawla N, Surani Z, Bastani R. Rates and sociodemographic correlates of cancer screening among South Asians. J Community Health. 2009;34:113–21. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorin SS, Heck JE. Cancer screening among latino subgroups in the United States. Prev Med. 2005;40:515–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brennenstuhl S, Fuller-Thomson E, Popova S. Prevalence and factors associated with colorectal cancer screening in Canadian women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:775–84. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janz NK, Wren PA, Schottenfeld D, Guire KE. Colorectal cancer screening attitudes and behavior: A population-based study. Prev Med. 2003;37:627–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gwede CK, William CM, Thomas KB, Tarver WL, Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, et al. Exploring disparities and variability in perceptions and self-reported colorectal cancer screening among three ethnic subgroups of U. S. Blacks. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:581–91. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.581-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tseng TS, Holt CL, Shipp M, Eloubeidi M, Britt K, Norena M, et al. Predictors of colorectal cancer knowledge and screening among church-attending African Americans and Whites in the Deep South. J Community Health. 2009;34:90–7. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green PM, Kelly BA. Colorectal cancer knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors in African Americans. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27:206–15. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200405000-00004. quiz 216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS. Factors associated with colon cancer screening: The role of patient factors and physician counseling. Prev Med. 2005;41:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whynes DK, Frew EJ, Manghan CM, Scholefield JH, Hardcastle JD. Colorectal cancer, screening and survival: The influence of socio-economic deprivation. Public Health. 2003;117:389–95. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(03)00146-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.James AS, Hall S, Greiner KA, Buckles D, Born WK, Ahluwalia JS. The impact of socioeconomic status on perceived barriers to colorectal cancer testing. Am J Health Promot. 2008;23:97–100. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07041938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bazargan M, Ani C, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Baker RS, Bastani R. Colorectal cancer screening among underserved minority population: Discrepancy between physicians’ recommended, scheduled, and completed tests. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:240–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Malley AS, Beaton E, Yabroff KR, Abramson R, Mandelblatt J. Patient and provider barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the primary care safety-net. Prev Med. 2004;39:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buki LP, Jamison J, Anderson CJ, Cuadra AM. Differences in predictors of cervical and breast cancer screening by screening need in uninsured Latina Women. Cancer. 2007;110:1578–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Busch S. Elderly African American Women's knowledge and belief about colorectal cancer. ABNF J. 2003;14:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stacy R, Torrence WA, Mitchell CR. Perceptions of knowledge, beliefs, and barriers to colorectal cancer screening. J Cancer Educ. 2008;23:238–40. doi: 10.1080/08858190802189030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Menon U, Champion VL, Larkin GN, Zollinger TW, Gerde PM, Vernon SW. Beliefs associated with fecal occult blood test and colonoscopy use at a worksite colon cancer screening program. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:891–8. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000083038.56116.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawsin C, DuHamel K, Weiss A, Rakowski W, Jandorf L. Colorectal cancer screening among Low-Income African Americans in East Harlem: A theoretical approach to understanding barriers and promoters to screening. J Urban Health. 2007;84:32–44. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruffin MT, 4th, Creswell JW, Jimbo M, Fetters MD. Factors influencing choices for colorectal cancer screening among previously unscreened African and Caucasian Americans: Findings from a triangulation mixed methods investigation. J Community Health. 2009;34:79–89. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9133-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen BH, McPhee SJ, Stewart SL, Doan HT. Colorectal cancer screening in Vietnamese Americans. J Cancer Educ. 2008;23:37–45. doi: 10.1080/08858190701849395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Powe BD, Cooper DL, Harmond L, Ross L, Mercado FE, Faulkenberry R. Comparing knowledge of colorectal and prostate cancer among African American and Hispanic Men. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:412–7. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181aaf10e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dassow P. Setting educational priorities for women's preventive health: Measuring beliefs about screening across disease states. J Women's Health. 2005;14:324–30. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun WY, Basch CE, Wolf RL, Li XJ. Factors associated with colorectal cancer screening among Chinese-Americans. Prev Med. 2004;39:323–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friedemann-Sánchez G, Griffin JM, Partin MR. Gender differences in colorectal cancer screening barriers and information needs. Health Expect. 2007;10:148–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henry KA, Sherman R, Roche LM. Colorectal cancer stage at diagnosis and area socioeconomic characteristics in New Jersey. Health Place. 2009;15:505–13. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Farmer MM, Bastani R, Kwan L, Belman M, Ganz PA. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening from patients enrolled in a managed care health plan. Cancer. 2008;112:1230–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shokar NK, Carlson CA, Shokar GS. Physician and patient influences on the rate of colorectal cancer screening in a primary care clinic. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21:84–8. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2102_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Von Wanger C, Semmler C, Good A, Wardle J. Health Literacy and self-efficacy for participating in colorectal cancer screening: The role of information processing. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:352–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Post DM, Katz ML, Tatum C, Dickinson SL, Lemeshow S, Paskett ED. Determinants of colorectal cancer screening in primary care. J Cancer Educ. 2008;23:241–7. doi: 10.1080/08858190802189089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]