Abstract

Background and Objectives

Staphylococcus aureus is a versatile organism causing mild to life threatening infections. The major threat of this organism is its multidrug resistance. The present study was carried out to investigate in - vitro activity of conventional antibiotics routinely prescribed for methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and methicillin sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) infections in the Northwest of Iran and other alternating therapeutic agents which are recommended for Gram positive organisms.

Materials and Methods

Clinical isolates of S. aureus were subjected to multiplex PCR for simultaneous speciation and detection of methicillin resistance. Antibacterial susceptibility pattern was determined using disk diffusion. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) were determined using E-test strips.

Results

The results revealed presence of nuc gene in all S. aureus isolates detected phenotypically earlier whereas, mecA gene was observed in 54% of strains. On disk diffusion and MIC determination assay, all MRSA and MSSA strains were susceptible to mupirocin (except one MRSA strain), linezolid and teicoplanin. Six vancomycin intermediate S. aureus strains were detected (VISA) with MIC= 4µg/mL, 5 of them being MRSA. In disk diffusion assay, 17.3% and 3.7% of isolates showed resistance to rifampin and fusidic acid, respectively. However, MIC50 and MIC90 tests shows promising in – vitro impact.

Conclusion

In – vitro mupirocin was found as an effective prophylactic ointment for nasal S. aureus eradication. Our data emphasize the performance of surveillance exercises to outline the existing antibiotics prescription policies and to slow down the emergence of multidrug resistant strains.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, increased antibiotic resistance, MIC

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is the foremost nosocomial pathogen facing humans today. Since the first isolation of methicillin resistance in S. aureus in 1961, the realm of concern is about its expanded prevalence, along with its efficiency at developing resistance to other antimicrobial agents. Until recently, vancomycin was considered the antibiotic of choice either solely or in combination, however, emergence of vancomycin intermediate-resistant S. aureus in Japan was followed by awareness of similar strains worldwide (1).

In the last few years, published reports have introduced antibacterial agents such as linezolid, fusidic acid, rifampin, and teicoplanin to treat various infections caused by MRSA (2). Nevertheless, for an effective approach, it is mandatory that antimicrobial agents must have activity against antibiotic-resistant S. aureus, along with low potential for resistance development.

Though vancomycin is a drug of choice for MRSA infections in hospitalized patients, its reduced susceptibility and poor tissue penetration make its therapeutic efficacy a concern. Linezolid has been compared with vancomycin and has been found equivalent in terms of tolerance and superior to vancomycin in treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections due to suspected or confirmed MRSA (3, 4). Linezolid resistance is uncommon.The year 2010 witnessed its first clinical outbreak with Linezolid Resistant S. aureus (LRSA). Nosocomial transmission and extensive linezolid usage were the factors associated with the outbreak. Usage and infection control measures were the suggestions to overcome such situation (5).

Fusidic acid has been found to possess equal or greater potency against staphylococci compared with vancomycin or daptomycin (6). The drug has been potentially useful as a topical agent for skin infections and proven effective for difficult – to – treat MRSA infections. Fusidic acid-resistant S. aureus has been reported in many countries, with the prevalence ranging from 0.3 to 52.5%, however, in Iran, MRSA and MSSA strains have been reported to be susceptible (7).

Rifampin, has also been an attractive broad spectrum antimicrobial choice for treating S. aureus infections, however, the drug is always proposed adjunctively (8). Its usage as oral therapy has been suggested for eradication of S. aureus carriage. Rifampin resistant S. aureus has been reported in Iran, with the prevalence ranging from 8-17% (9).

Vancomycin and mupirocin have been employed against Staphylococcus aureus in our region, however, other antibacterial agents have not been in conventional usage.

The aim of the present study was to determine comparative activities of oxacillin, vancomycin, mupirocin, rifampin, fusidic acid, linezolid and teicoplanin against clinical isolates of methicillin resistant and susceptible Staphylococcus aureus strains by disk diffusion and E-test in our region.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Isolation and Identification of S. aureus

In an analytic–descriptive cross sectional study carried out at University Teaching Hospital, serving as the referral center for patients from North West region of Iran, a total of 1,945 clinical specimens, including blood, urine, postoperative wound, synovial fluid, sputum and anterior nares were processed for the isolation and identification of Staphylococcus aureus according to phenotypic methods such as Gram's staining, yellow or white colonies on blood agar (yellow colonies on mannitol salt agar for nasal swabs), catalase, slide and tube coagulase and DNase tests (10). Duplicate isolates from the same patient were not included. All isolates were immediately stored at -70°C until required.

PCR for speciation and methicillin resistance

All isolates were confirmed as S. aureus by screening for the nuclease – encoding gene (nuc) and for methicillin resistant by mecA by using a multiplex PCR (11, 12). Primers were synthesized by Eurofin, Germany. Strains were considered as MRSA or MSSA based on the presence or absence of mecA gene respectively.

Briefly, DNA was extracted using SDS-Proteinase K with CTAB method as prescribed by Sambrook and Russell (13). Multiplex PCR (mPCR) was performed in 25 µl PCR reaction mixture containing; 1X PCR buffer, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 deoxynucleoside triphosphates sets, 0.5 mM each oligonucleotide primer and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase. The PCR reaction was as follows: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, with 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30s, annealing at 58°C for 30s, extension at 72°C for 45s and final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The mecA specific PCR product was 154 bp long and the presence of nuc gene was observed with an expected size of 270 bp. S. aureus ATCC 29213 was used as control strain.

Antimicrobial testing Qualitative evaluation

Susceptibility testing for MRSA and MSSA was conducted on Mueller-Hinton agar by disk diffusion technique according to the guidelines of Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (14) with a panel of following antibiotics: oxacillin (1 µg), vancomycin (30µg), teicoplanin (30 µg), linezolid (30 µg), rifampin (30 µg), mupirocin (5 µg) and fusidic acid (10 µg), all purchased from MAST (UK). As there are no available CLSI interpretive criteria for fusidic acid and mupirocin for S. aureus, susceptible phenotype defined as a zone diameter of 22 mm (15) and ≥14 mm (16) was used respectively. S. aureus ATCC 25923 and ATCC 43300 strains were used as controls for the antibiotic susceptibility determination.

Quantitative evaluation

The MICs were determined on Mueller-Hinton agar plates for oxacillin, vancomycin, teicoplanin, linezolid, rifampin, mupirocin and fusidic acid by standard E-test method according to the manufacturer's recommendations (bio Mérieux, Inc). The breakpoints for resistance were those defined by the CLSI (14), except for mupirocin and fusidic acid for which breakpoints from the study of Finlay et al. (15) (MIC ≤4µg/ ml as susceptible) and European Society of Microbiology (16) which suggests MIC ≤ 1 as susceptible and MIC > 1 as resistant,were used.

RESULTS

Among the total 1,945 clinical specimens processed, 150 S. aureus were isolated after identification on the basis of phenotypic tests, all strains scored positive for the nuc gene, while mecA gene was revealed in 81 (54%) isolates (considered as MRSA), and the remaining 69 (46%) isolates were identified methicillin sensitive (MSSA). The source of these isolates was as follows: surgical and internal wards (n = 51), burn patients (n = 36), infectious ward (n = 25), skin and hemodialysis (n = 7 each) and the remaining isolates (n = 24; 14.6%) were obtained from various ICU's. Concerning the origin of MRSA isolates, majority of strains [n = 46 (56.7%)] were isolated from wounds, followed by bloodstream [17 (20.9%)], endotracheal tube [8 (9.8%)], nasopharynx (n = 4;9%), synovial fluid (n = 3; 7%), and the remaining were obtained from specimens like intravenous catheter, and other body fluids.

Similarly, MSSA isolates were obtained from postoperative wound [n = 29; (42%)], bloodstream [n = 21; (30.4%)], endotracheal tube (n = 9; 13.04%), body fluids (n = 3; 4.34%) and remaining from other clinical specimens like nasopharynx, synovial fluid, urine and intravenous catheter.

On disk diffusion assay, mecA-positive MRSA strains revealed 88.8%, 17.3% and 3.7% as being resistant to oxacillin, rifampin and fusidic acid, respectively. Only one isolate (1.23%) was observed resistant to mupirocin. All MRSA strains were found sensitive to teicoplanin. Among MSSA strains, all isolates were uniformly found sensitive to fusidic acid and mupirocin, while few of them showed non susceptibilty to rifampin (2.9%). Surprisingly, 8.7% MSSA (mecA gene not detected) were found resistant to oxacillin on disk diffusion. All isolates of S. aureus including MRSA and MSSA, were found sensitive to linezolid by disk diffusion (Table 1).

Table 1.

In- vitro activities of tested antimicrobial agents against 81 mecA-positive MRSA and 69 mec- negative MSSA strains.

| Antibiotics | Disk Diffusiona | E- testa | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| MRSA (n= 81) | MSSA(n= 69) | MRSA(n= 81) | MSSA(n= 69) | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| R | I | S | R | I | S | R | I | S | R | I | S | |

| Oxacillin | 88.8 | 4.9 | 6.2 | 8.7 | 0 | 91.3 | 96.2 | 0 | 3.7 | b 4.3 | 0 | 95.6 |

| Vancomycin | 0 | 55.5 | 44.4 | 0 | 4.3 | 95.6 | 0 | 35.8 | 64.2 | 0 | 27.5 | 72.5 |

| Rifampin | 17.3 | 4.9 | 77.7 | 2.9 | 0 | 97.1 | 17.3 | 3.7 | 79.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 95.2 |

| Fusidic acid | 3.7 | 0 | 96.2 | 1.2 | 0 | 98.5 | 4.93 | 0 | 95.0 | 4.34 | 0 | 95.6 |

| Mupirocin | 1.23 | 0 | 98.7 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 1.23 | 0 | 98.7 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Teicoplanin | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 1.4 | 98.5 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Linezolid | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

R: resistant; I: intermediate; S: sensitive

All oxacillin resistant isolates had MICs≥ 256 mg/l.

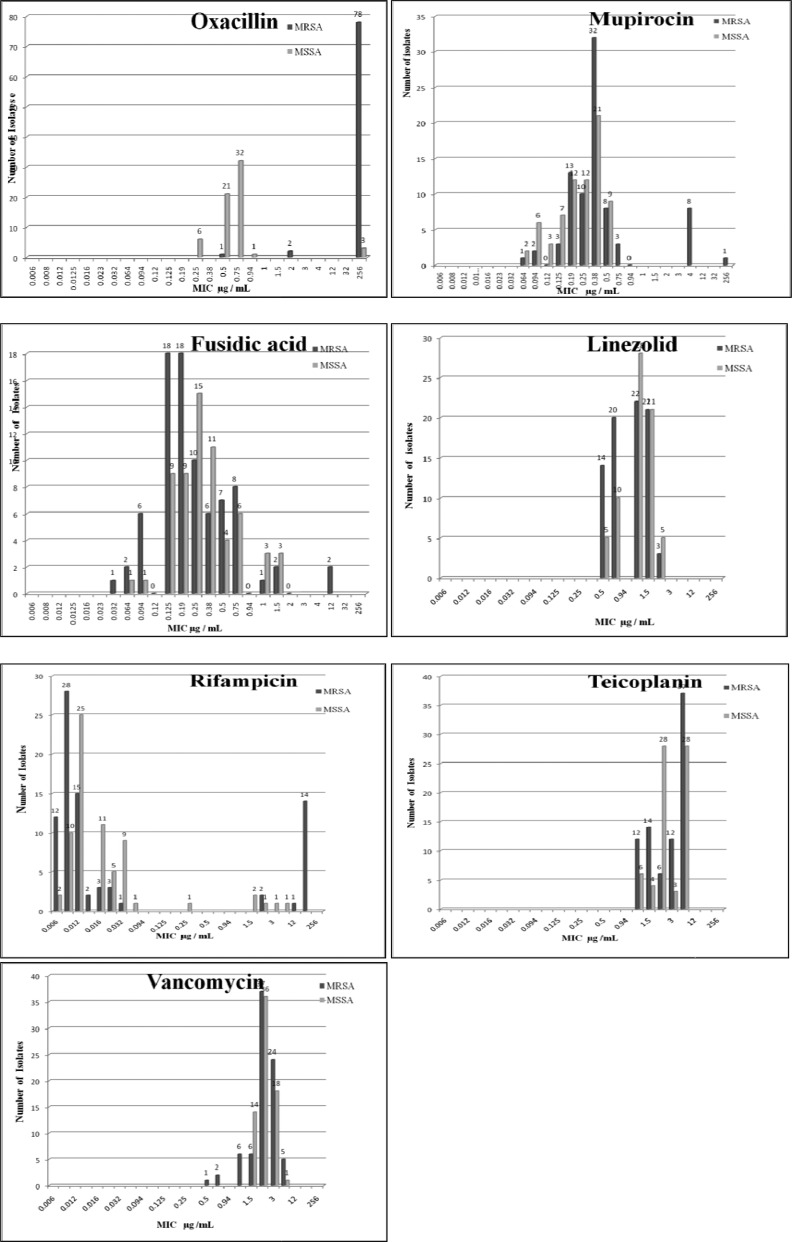

Interestingly, 55.5% MRSA and 4.3% MSSA strains produced a zone diameter equal to 14mm for vancomycin on disk diffusion assay, which should be reported as intermediate, however, when MIC assay was performed by E-test, MIC ranged from 0.5- 4 µg/mL and taking into consideration the interpretive criteria of vancomycin which has changed since 2006 when MIC breakpoints for each category reduced one-fold, 48 (32%) strains were observed as VISA. Of these, 6 isolates had MIC = 4 µg/mL (8.3%) (all of them being MRSA), while 42 isolates (24 of them being MRSA and 18 MSSA) were observed revealing MIC = 3µg/mL, which is one log higher than the susceptible level (MIC ≤ 2µg/mL) Though our study did not find a very high level vancomycin resistance (MIC50 =1; MIC90=1.8), however, this upward MIC shift from level of susceptible towards intermediate level is in vitro concern. Presence of six VISA strains or a slightly upward shift in MIC level has not yet impacted significantly in vivo but shows the occurrence of VISA in vitro in our environment. Among the strains which showed MIC = 2 µg/mL (n = 73), 36 of them were MRSA. The MICs of different antimicrobial agents for MRSA and MSSA strains are presented in Tables 1 and 2 respectively and Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of MIC values of MRSA and MSSA isolates for various antibiotics.

Among MRSA strains, all were found highly resistant (MIC ≥256 mg/L) to oxacillin (MIC50=128 µg/mL; MIC90=256 µg/mL). Mupirocin resistance was not seen in any of the MRSA isolates except one isolate showing MIC = 128 mg/L. This mupirocin resistant strain was highly resistant to oxacillin (≥256 mg/L), rifampicin and fusidic acid (each with MIC = 12 mg/L). In comparison, MSSA isolates had MIC50=0.5 µg/mL and MIC90=0.9 µg/mL)

MICs for fusidic acid for 7 isolates was over 1 mg/L (two MRSA isolates with MIC= 12 mg/L, two MRSA and 3 MSSA isolates with MIC = 1.5 mg/L) (Fig. 1) thus, though were considered as resistant, however, MIC50 and MIC90 did not reveal concern (MIC50= 0.9 mg/L; MIC90=0.5 mg/L). The characterization of fusidic acid-resistant detected by the E-test is presented in 3.

Twenty one (14%) isolates (17 being MRSA while, 4 MSSA) were observed to have MIC >1 for rifampin (Fig. 1), thus were considered resistant, however, overall the antibiotic was shown a potential impact with MIC50 and MIC90 of MRSA isolates being 0.006 mg/Land MIC90=0.02 mg/Lrespectively. Teicoplanin and linezolid provided promising activity for all MRSA and MSSA isolates (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

Staphylococcus aureus is particularly efficient at developing resistance to antimicrobial agents and introduction of new class of antimicrobial agents has been followed by the emergence of resistant forms of this pathogen (1). In view of expanded use of antibiotics, there is always a need to survey antibiotic pattern to comprehend emerging trends.Microbiological laboratories play an important role in characterization of the pathogens, detection and confirmation of any emergence of antibiotic resistance.

In the present study, prevalence of methicillin resistant S. aureus was 54% (with mec A gene detected), which is in concordance with the studies conducted by Yadegar et al. (17) in Tehran, Iran and Stenstorm et al. (18) in Canada, but was higher compared to Shittu et al. (19) survey from South Africa. Since the specimens collected in our study were isolated from patients admitted to high risk wards of a University affiliated referral hospital serving for North West region of Iran, such a high prevalence requires attention and should not be ignored. MRSA does not appear to be more virulent, however it possess more risk in terms of resistance to other antibiotics.

MIC determinations of oxacillin in current study showed 98.3% of MRSA isolates were highly resistant to oxacillin (MICs ≥256 mg/l) while all harbored mecA gene. Surprisingly, three (4.3%) MSSA strains (mecA negative) were observed highly resistant to oxacillin with MIC ≥256 mg/l. The absence of mecA gene in these strains indicates an alternative mechanism of oxacillin resistance such as the β- lactamase hyperproduction (20) or production of normal PBP with altered binding capacity (21). On the other hand, one MSSA isolate which had MIC value equal to 0.75 mg/l, later was found to possess mecA gene. The occurrence of this variant could be explained by the presence of complete regulator genes (mecI and/or mecRI), as described previously (22). The emergence of vancomycin intermediate-resistant S. aureus is a great concern and has been proposed to pose a serious challenge to the clinicians in finding an alternative treatment. Vancomycin resistance in S. aureus has been previously reported in Tehran (Iran) by Emaneini et al. (23) whereas, published studies from other Iranian hospitals found vancomycin resistance as an extremely rare phenomenon (24, 25). Since no data is available on clinical usage of vancomycin and its efficacy, we cannot predict vancomycin resistance in vivo. Based on disk diffusion results, 55.5% of MRSA and 4.3% of MSSA strains were found intermediate resistant to vancomycin in our study. However, of these MRSA strains, five (6.2%) had MIC = 4 mg/L and the rest (29.6%) had MIC = 3 mg/L; thereby described as vancomycin-intermediate resistant S. aureus strains (VISA). Similarly 19 (23.4%) MSSA isolates were also observed to be VISA. Reduced susceptibility to vancomycin in S. aureus strains in our region is an alarm that may potentially drive the future development of vancomycin resistant strains.

In the present study, none of the MRSA isolates were found resistant to linezolid and teicoplanin, and all MSSA were susceptible to mupirocin, linezolid and teicoplanin. The complete susceptibility of MRSA and MSSA to linezolid and teicoplanin observed in this study is compatible with other published reports (26–28).

Three (4.34%) MSSA strain and four (4.93%) MRSA strains were found resistant to fusidic acid which is in accordance with studies reported from South Africa (19). It is well recognized that use of fusidic acid alone is associated with increased resistance as compared when added in combination with other drugs. Nathwani et al. (29) used fusidic acid in combination with rifampin and found more beneficial in treatment of serious MRSA infections. We observed rifampin resistance in 20.9% MRSA (14 strains with MIC = 32mg/L) and 5.79% MSSA isolates. This resistance rate was higher than that found in the studies reported by Askarian et al. (2). The higher rate of resistance to rifampin in our strains is probably due to the increasing usage of this antibiotic in our clinics for prophylactic and treatment purposes, especially for mycobacterial infections.

Mupirocin, an inhibitor of bacterial isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase, has potent activity against S. aureus strains including methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and glycopeptide intermediate S. aureus (GISA). It has been used to treat staphylococcal skin infections as well as to eliminate nasal carriage of MRSA. However, indiscriminate use of mupirocin has been reported to encourage the emergence of mupirocin-resistant S. aureus (30). Though mupirocin is used for a long time in our clinical set up, only one strain showed non susceptibility. The rate of mupirocin resistance in our study population corresponds more closely to a clinical report from a tertiary hospital in Pakistan (31). In spite of mupirocin resistance is not currently ascertained, still it is suggested that S. aureus isolates should be routinely tested in clinical microbiology laboratories in this region, so that mupirocin resistant isolates could be detected early, and to facilitate the prompt loss of the beneficial use of this antimicrobial agent against MRSA.

CONCLUSION

In this study, linezolid and teicoplanin have shown to be the promising alternatives. Low level fusidic acid resistance was evident in our study. Mupirocin and fusidic acid are the cornerstones of MRSA eradication therapy and resistance to these antibiotics will affect the ability of hospitals to control the spread of MRSA. So their use should be restricted to where clinically indicated and where the infecting bacteria are susceptible. In addition, slight increase in vancomycin MIC towards intermediate level is an alarm which can be checked by repeated laboratory surveys and any elevated resistance should be managed in a best possible way.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant from Research Center of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. Ms. Leila Dehghani, is being thanked for her excellent microbiology laboratory effort.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim HB, Jang HC, Nam HJ, Lee YS, Kim BS, Park WB, et al. In Vitro activities of 28 antimicrobial agents against Staphylococcus aureus isolates from tertiary-care hospitals in Korea: a nationwide survey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1124–1127. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1124-1127.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Askarian M, Zeinalzadeha A, Japoni A, Alborzi A, Memish ZA. Prevalence of nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and its antibiotic susceptibility pattern in healthcare workers at Namazi hospital, Shiraz, Iran. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burkhardt O, Pletz MW, Mertgen CP, Welte T. Linezolid versus vancomycin in treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2260–2266. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2260-2266.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li JZ, Willke RJ, Rittenhouse BE, Rybak MJ. Effect of linezolid versus vancomycin on length of hospital stay in patients with complicated skin and soft tissue infections caused by known or suspected methicillin-resistant staphylococci: results from a randomized clinical trial. Surg Infect. 2003;4:57–70. doi: 10.1089/109629603764655290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miguel SG, María A De la T, Gracia M, Beatriz, María JT, Sara D, Francisco JC, et al. Clinical outbreak of linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an intensive care unit. JAMA. 2010;303:2260–2264. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfaller MA, Castanheira M, Sader HS, Jones RN. Evaluation of the activity of fusidic acid tested against contemporary Gram-positive clinical isolates from the USA and Canada. Int J Antimicrob Agent. 2010;35:282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howden BP, Grayson ML. Dumb and Dumber—The potential waste of a useful antistaphylococcal agent: emerging fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus . Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:394–400. doi: 10.1086/499365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlroth J, Kuo M, Tan J, Bayer AS, Miller LG. Adjunctive use of rifampin for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:805–819. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.8.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathew EF, Ioannis AB, Konstantinos NF. Oral rifampin for eradication of Staphylococcus aureus carriage from healthy and sick populations: A systematic review of the evidence from comparative trials. Clin Infect Dis. 42:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kloss WE, Bannerman TL. Staphylococcus and Micrococcus . In: Murray PR, Baron EJ, Pfaller MA, Tenover FC, Yolken RH, editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. Washington DC: ASM; 1995. pp. 282–284. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brakstad OG, Aasbakk KJ, Maeland JA. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the nuc Gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1656–660. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1654-1660.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murakami K, Minamide W, Wada K, Nakamura E, Teraoka H, Watanabe S. Identification of methicillin-resistant strains of staphylococci by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2240–244. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2240-2244.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambrook J, Russel DW. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 3rd ed. New York: Cold spring Harbor; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility testing. Approved standard M2-A7; Wayne, PA: Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finlay JE, Miller LA, Poupard JA. Interpretive criteria for testing susceptibility of staphylococci to mupirocin. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 1997;41:1137–39. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing EUCAST. Breakpoint tables for interpretations of MICs and zone diameters; 2010. Version 1.1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yadegar A, Sattari M, Mozafari NA, Goudarzi GHR. Prevalence of the genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and methicillin resistance among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus in Tehran, Iran. Microb Drug Resist. 2009;15:109–113. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2009.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stenstom R, Grafstein E, Romney M, Fahimi J, Harris D, Hunte G, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infection in a canadian emergency department. CJEM. 2009;11:430–438. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500011623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shittu A, Nübel U, Udo E, Lin J, Gaogakwe S. Characterization of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from hospitals in KwaZulu-Natal province, Republic of South Africa. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:1219–1226. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.011452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Struelens M, Mertens R, Groupement P. National survey of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in belgian hospital: detection methods, prevalence, trends and infection control measures. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:56–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02026128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araj GF, Talhouk RS, Simaan CJ, Massad MJ. Discrepencies between mecA PCR and conventional tests used for detection of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Inter J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;11:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(98)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chambers HF. Methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Molecular and biochemical basis and clinical implications. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:781–91. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emaneini M, Aligholi M, Hashemi FB, Jabalameli F, Shahsavan S, Dabiri H, et al. Isolation of vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a teaching hospital in Tehran. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66:92–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soltania R, Khalilia H, Rasoolinejadb M, Abdollahi A, Gholami KH. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from hospitalized patients in Tehran, Iran. Iranian J Pharma Sci. 2010;6:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vahdani P, Saifi M, Aslani MM, Asarian AA, Sharafi Antibiotic resistant patterns in MRSA isolates from patients admitted in ICU and infectious Ward. Tanaffos. 2004;3(11):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conceição T, Tavares A, Miragaia M, Hyde K, Aires-de-Sousa M, de Lencastre H. Prevalence and clonality of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the Atlantic Azores islands: predmonanace of SCCmec types IV, V and VI. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:543–550. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0892-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neela V, Sasikumar M, Ghaznavi GR, Zamberi S, Mariana S. In vitro activies of 28 antimicrobial agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from a clinical setting in Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Pub Health. 2008;39:885–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahmood K, Tahir T, Jameel T, Ziauddin A, Aslam HF. Incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) causing nosocomial infection in a tertiary care hospital. Annals. 2010;16:91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nathwani D, Morgan M, Masterton RG, Dryden M, Cookson BD, French G, et al. British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy Working Party on Community-onset MRSA Infections: Guidelines for UK practice for the diagnosis and management of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections presenting in the community. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:976–994. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saderi H, Owlia P, Habibi M. Mupirocin resistance among Iranian isolates of Staphylococcus aureus . Med Sci Monit. 2008;14:210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nizamuddin S, Irfan S, Zafar A. Evaluation of prevalence of low and high level mupirocin resistance in methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates at a tertiary care hospital. J PMA. 2011;61:519–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]