Abstract

Massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding is a significant and expensive problem that requires methodical evaluation, management, and treatment. After initial resuscitation, care should be taken to localize the site of bleeding. Once localized, lesions can then be treated with endoscopic or angiographic interventions, reserving surgery for ongoing or recurrent bleeding.

Keywords: lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage, angiography, colonoscopy, gastrointestinal hemorrhage: surgery, radionuclide scintigraphy

Objectives: Upon completion of this article, the reader should have a clear understanding of the evaluation and management of patients with lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The reader should understand the radiologic, endoscopic, and surgical options for the treatment of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) is defined as bleeding originating distal to the ligament of Treitz. Although rare, massive bleeding typically is thought to require more than 3 to 5 units of blood transfused in 24 hours. The annual incidence of LGIB is estimated at 20 to 30 cases per 100,000 in Westernized countries.1 The mean cost per admission ranges from $9,700 to $11,800.2,3 Comfort with managing the presentation of LGIB is important as the number of hospitalizations with this initial presentation is on the rise, increasing nationally by 8% between 1998 and 2006.4

Although there is no standardized path for the investigation and treatment of LGIB, for many years the diagnostic armamentarium largely involved endoscopy, radionuclide scintigraphy, and mesenteric angiography. In the past decade, there has been increased use of capsule endoscopy, double-balloon enteroscopy, and computed tomography angiography (CTA) to localize the site of bleeding. Therapeutic options have remained largely unchanged and include endoscopic techniques, endovascular embolization, and surgical resection. Fortunately, 75 to 85% of LGIB will resolve with supportive care only.5,6,7

Although lower GI hemorrhage can occur at any age, specific disease processes are distinctive for different age groups and familiarity with this can help tailor the diagnostic workup (Table 1).

Table 1. Common Causes of Hematochezia122.

| Age Group | Source of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding |

|---|---|

| Adolescents and young adults | Meckel's diverticulum Inflammatory bowel disease Polyps |

| Adults to 60 years of age | Diverticula Inflammatory bowel disease Neoplasms |

| Adults older than 60 years | Arteriovenous malformations Diverticula Neoplasms |

Children and adolescents present most commonly with bleeding from a Meckel's diverticulum, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and polyps (usually juvenile polyps).8 The incidence of Meckel's diverticula in the general population is in the range of 1 to 3%.9,10,11 Approximately 20% of patients with Meckel's diverticula are symptomatic, most commonly presenting with obstruction or bleeding.10,11 Meckel's diverticula can harbor gastric mucosa that produces acid. The surrounding normal ileal mucosa, bathed in this ectopic, high-acid environment, ulcerates and then bleeds.12 Bleeding episodes are usually self-limited, but may be recurrent as the mucosa heals and then ulcerates again.

Juvenile polyps are benign hamartomas that can grow to a large size and bleed spontaneously. The polyps are usually solitary and self-limiting, auto-amputating when they outgrow their blood supply. Bleeding is the most common presenting symptom of the syndrome, present in essentially all patients.13

Inflammatory bowel disease has a bimodal distribution, with most diagnoses occurring either in young adulthood or later in approximately the sixth decade of life. Bleeding is usually the initial symptom, with massive hemorrhage occurring in only ∼1% of patients.14,15 Distinguishing Crohn's colitis from ulcerative colitis is important for guiding subsequent surgical intervention; however, massive hemorrhage may require an emergent colectomy before a definitive diagnosis can be obtained.

Adults most commonly present with diverticular bleeding, which occurs in up to 3 to 5% of patients with diverticulosis.16,17,18 Diverticula can be located throughout the colon, and in patients determined to have diverticular bleeds, the bleeding diverticulum has been found to be in the right colon nearly 50% of the time.19,20,21 The etiology of diverticular bleeding is not clearly understood; however, various theories have evolved over time. Chronic injury to the penetrating vasa recta through muscular contraction is one favored explanation.22 Nearly 70 to 80% of diverticular bleeds will resolve spontaneously, with rebleeding in up to 38% of patients.16,18,20

With advancing age, neoplasm increases in likelihood. A personal or family history of polyps or cancer increases one's risk. Bleeding, in this situation, is typically slow and insidious and most will present with chronic anemia.

Elderly patients beyond the sixth decade of life have risks of diverticular hemorrhage and neoplasm; however, with advancing age, bleeding from arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) becomes increasingly prevalent. These lesions can be found throughout the GI tract, but are usually found in the right colon and are thought to develop from a lifetime of peristaltic contraction of the muscular wall, which results in chronic venous congestion, capillary dilation, and ultimately ectatic vessels.23 An association of colonic AVMs and aortic stenosis has been reported in several series; however, the pathophysiology has not been elucidated beyond simply increasing prevalence of both diagnoses with advanced age.24,25,26,27 Up to 90% of bleeding AVMs will stop spontaneously; however, rebleeding can occur in up to 25% of patients. Most patients will have multiple episodes before a definitive diagnosis is made because these lesions are difficult to detect when not bleeding.28

Less common causes of massive lower GI bleeding include ischemic colitis, postpolypectomy bleeding, hemorrhoids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) ulcers, diversion colitis, radiation colitis, infectious colitis, solitary rectal ulcer, stercoral ulcers, and small bowel tumors. Coagulopathies from supertherapeutic levels of Warfarin or from genetic bleeding diatheses are also important to recognize. These etiologies at times are overlooked as causes of massive lower GI hemorrhage, but should be kept in mind when dealing with the patient with obscure bleeding.29,30

Initial Workup and Diagnosis

Prior to any workup, a patient with a suspected massive bleed and hemodynamic instability should be resuscitated with crystalloid and blood products as necessary. (A type and crossmatch should be a part of the initial laboratories drawn.) Depending on the patient's age and severity of the bleeding, an intensive care unit (ICU) admission may be required. Once stabilized, a thorough history should be taken with particular attention paid to the patient's medications (NSAIDs, anticoagulants) and past medical history (diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease, prior episodes of bleeding, etc.).

Once the resuscitation has begun, attention should be focused on localizing the source of the bleeding. A carefully placed nasogastric tube (NGT) with irrigation and aspiration of bile is necessary to ensure sampling of duodenal contents. Should there be bloody NGT aspirate then an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is warranted. It should be understood that 11 to 15% of patients will have an upper GI bleeding site despite “negative” NGT aspirates, leading some to recommend EGD in all patients with hematochezia.31,32

Additionally, a digital rectal examination (to check for palpable causes of bleeding, such as a tumor) should be performed, followed by anoscopy and rigid sigmoidoscopy. As visibility can be limited, asking the patient to evacuate (or administering an enema) just prior to examination may improve the yield. Although a rare cause of significant hematochezia, hemorrhoidal bleeding, especially in the anticoagulated patient, can be the source and may require ligation or formal hemorrhoidectomy.33

Localizing the Continuing Massive Hemorrhage

Should the initial tests indicate a lower GI source outside of the anorectum, the common diagnostic tests for localizing the bleeding include colonoscopy, nuclear scintigraphy, and angiography. The use of other, newer techniques such as CTA, double-balloon enteroscopy, and wireless capsule endoscopy are especially useful in the setting of obscure bleeding and will be discussed at the end of this section. The advantages and disadvantages of these modalities will be discussed further.

Diagnostic Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy has been used for localization of hematochezia since the 1970s and remains one of the mainstays of both diagnostic and therapeutic management.34 The ease with which one can locate the site of bleeding will vary, with the reported diagnostic yields in the range of 42 to 76%.32,35,36,37

The use of a mechanical bowel prep can improve visualization of the mucosa. However, if the bleeding has stopped, it is difficult to know which, if any, of the identified abnormalities were responsible for the bleed as the vast majority of patients will have multiple nonbleeding lesions (such as diverticula or AVMs).

In the setting of upper GI bleeding, urgent endoscopy has been shown to be beneficial. However, the timing of colonoscopy for lower GI bleeding has remained controversial. Some studies suggest that performing urgent colonoscopy within 12 to 24 hours of presentation can improve the diagnostic yield and therapeutic outcome.38,39,40,41,42 Recently, the results of a prospective, randomized trial were published that sought to compare urgent colonoscopy (within 12 hours of presentation) to elective colonoscopy (36 to 60 hours after presentation). Although the trial had to be closed prematurely due to failure to recruit enough patients to be sufficiently statistically powered, the urgent colonoscopy group did not have decreased subsequent diagnostic or therapeutic interventions, amount of blood transfused, hospital length of stay, or hospital charges.43 Only 15 to 18% of hospitalized patients will have continued bleeding, so urgent colonoscopy may not be justified, as the majority of patients will have stopped bleeding whether colonoscopy is performed urgently or electively.43,44

In some cases, immediate colonoscopy after the episode of hematochezia, using an enema to clear the distal colon and rectum, may be able to rapidly distinguish right- from left-sided bleeds. Though the mucosa of the unprepped right colon may be difficult to visualize, at the time of exam, if blood is found only in the left colon, then further diagnostic and therapeutic efforts can focus there.45

This theoretic advantage of colonoscopy as both a diagnostic and a therapeutic intervention often is belied by the difficulty of the actual examination in the face of unprepped bowel or a massive hemorrhage. Nevertheless, colonoscopy, when deployed in the correct setting, is a very valuable tool.

Radionuclide Scintigraphy

Nuclear scintigraphy has been used for several decades to help localize lower GI hemorrhage. The favored approach is to use technetium-labeled red blood cell (Tc-RBC) scanning. This is performed by ex vivo labeling of an aliquot of the patient's own RBCs, followed by injecting them back into the patient. Localization is based on detection of where the tracer appears to extravasate and pool. This process requires ∼30 minutes prep time (to extract and then tag the RBCs), but benefits from the slow washout of the tracer, which enables better localization for intermittent bleeding as the patient can be rescanned multiple times within 12 to 24 hours.46

The rate at which nuclear scintigraphy can detect bleeding has been experimentally modeled, and detection rates as low as 0.05 cc per minute are possible.47,48 In practice, the accuracy of scintigraphy has been reported to be in the range of 41 to 94%.49,50 The wide range may be due to the lack of detail on nuclear scintigraphy scans and the resulting difficulty in discriminating the colon from overlying small bowel. Because of the variability in the accuracy, guiding surgical intervention based solely on the results of the Tc-RBC scan is not advocated.51 Rather, most authors recommend using Tc-RBC scans as a screen prior to angiography or colonoscopy. In a retrospective review of 271 angiograms, use of a screening Tc-RBC scan improved the diagnostic yield of angiography by over two-fold.52

Overall, Tc-RBC scanning is safe with minimal morbidity. The ability to scan a patient multiple times is especially useful in the setting of intermittent bleeding, and when positive, can help direct angiographic intervention.

Diagnostic Angiography

Diagnostic mesenteric angiography is an invasive test that has also been used for several years for the localization of GI bleeding. The first report of its use in the setting of hematochezia is from 1963.53 One of the advantages of angiography is the opportunity for therapeutic intervention at the time of diagnosis and the ability to perform a provocative test to aid with localization of an intermittent bleed. Patients must be carefully selected, however, as there is a risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.54,55

Angiography requires a higher minimum bleeding rate of 0.5 cc/min when measured using dog models.53 In practice, the detectable bleeding rate may indeed need to be higher, in the range of 1.0 to 1.5 cc/min.56 The reported diagnostic yield is in the range of 40 to 86%.57,58

The use of provocative testing to improve the diagnostic yield of angiography was reported over 25 years ago.59,60 This technique incorporates the use of heparin, thrombolytics, vasodilators, or a combination thereof to “provoke” bleeding and aid with localization of an intermittent bleed. Judicious employment of provocative testing is advised as the potentially improved yield must be balanced with the risk of uncontrolled GI hemorrhage or intracranial hemorrhage. Although the reported complication rate in the literature is nearly zero, these are all small series. The improvement in diagnostic yield ranges from 29 to 100%.59,61,62,63 Currently, there are no high-powered studies to support its routine use.

In the properly selected patient, angiography can elucidate the site of bleeding. The use of a screening Tc-RBC study and/or provocative testing may aid with improving the diagnostic yield, especially with an intermittent bleed.

Computed Tomography Angiography

As CT scanning has become more ubiquitously employed in the timely diagnosis of a variety of medical conditions, so too has its use increased in the management of the patient with hematochezia. Multidetector CT scanners with special angiographic protocols have been used to help localize GI bleeds. These scans are performed without the use of oral contrast, and a positive study is predicated on visualization of intraluminal extravasation of intravenous contrast. There is no way to perform the test without intravenous contrast; as such, there may be limited applicability in the patient with renal insufficiency owing to the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.

The studies that have looked at the use of CTA in the localization of GI hemorrhage report sensitivity of 91 to 92% when there is active bleeding, but are considerably lower when the bleeding is intermittent in nature with rates reported from 45 to 47%.64,65,66,67 In a recent prospective study of 27 patients with lower GI bleeding, CTA was able to identify the source of bleeding in 70% of patients.68

Multidetector CTA is quick, relatively noninvasive and effective at localization, especially in the patient with continued bleeding.

Localization of the Small Bowel Bleed

Negative examinations of the upper and lower GI tracts in the face of continued bleeding should prompt an evaluation of the small bowel. There are essentially three methods of evaluation aside from the aforementioned angiography: wireless capsule endoscopy, double-balloon enteroscopy, or in the appropriate setting, a radionuclide Meckel's scan.

Capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) have similar diagnostic yields in the range of 55 to 65% of patients with hematochezia.69,70,71,72 The disadvantage of capsule endoscopy is that failure to pass the capsule can occur 5% of the time and necessitates further intervention for retrieval.72 There are also several reports of lesions missed by capsule endoscopy that were subsequently identified on double-balloon enteroscopy.73,74,75,76

DBE should only be attempted by a skilled, experienced endoscopist, but if available has the added benefit of immediate therapeutic intervention. The average length of small bowel examined was 310 cm past the pylorus in one series of 216 procedures.77 Total evaluation of the small bowel is possible and in one of the largest prospective series of 2245 DBEs, there was a 23% rate of complete enteroscopy.

The uptake of technetium-pertechnetate in ectopic gastric mucosa has been used since the 1970s to identify the site of a Meckel's diverticulum, especially in the young patient with hematochezia. The scan has minimal morbidity and a specificity approaching 100% in multiple studies, though the sensitivity is much lower at 62%.78,79 In the setting of a suspected bleeding Meckel's diverticulum, this can be a valuable confirmatory test.

Therapeutic Interventions

Therapeutic Colonoscopy

Endoscopy can be used to treat moderate and even massive bleeding in the appropriate settings. Ideally, a mechanical bowel prep can be performed prior to the procedure.80

AVMs are particularly amenable to endoscopic treatment with contact cautery, argon plasma, or laser coagulation. Success rates vary with reported long-term recurrence of bleeding in the range of 10 to 39%.81,82 Many patients require multiple sessions to completely treat all the areas. There are often multiple AVMs throughout the GI tract and of those patients with AVMs and recurrent bleeding, small bowel angiodysplasia were found to be the source in 15%.83,84 The risk of complications (including perforations) in various series ranges from 2 to 7% and is related to the fact that these lesions are often found in the thinner-walled right colon.81,85,86

The mainstays of management of diverticular bleeding are epinephrine injection, thermal or electrical coagulation, and more recently, endoscopic clips. Diverticula with active bleeding can be injected with epinephrine around the mouth of the diverticulum. Electrical and thermal coagulation can be used as monotherapy or in conjunction with epinephrine injection. Early rebleeding rates range from 0 to 35% without any major procedure-related complications.35,87,88 In the past 15 years, a few small series have described the use of endoscopic clips to control diverticular hemorrhage. These studies show equivalent success (and complication rates) compared with epinephrine injection and electrical and thermal coagulation.89,90,91

Overall, endoscopic therapy is safe and effective with low recurrence rates. The choice of technique will depend on the source of the bleeding, availability of resources, and the experience of the endoscopist.

Therapeutic Angiography

Angiography, like colonoscopy, offers the potential for immediate therapeutic intervention after diagnosis. Once a suspicious area of contrast blush has been identified, treatment can be undertaken with either vasopressin infusion or selective embolization.

Vasopressin infusion has been used since the 1970s and causes arterial vasoconstriction and decreased blood flow to the area of the bleed when applied with a targeted catheter.92 Cessation of bleeding occurs in 59 to 90% of patients; however, once the vasopressin is stopped the rate of rebleeding is as high as 50%.93,94,95 This has led some to recommend vasopressin only as second-line therapy when superselective embolization is not feasible.93

Angiographic embolization historically has been eschewed due to colonic infarction rates approaching 20%.96,97 Transcatheter superselective embolization, a procedure that has been in use for several years, has a much better safety profile and is quite efficacious. Using microcatheters to target the embolization of the subsegmental peripheral arterial branches, recent studies have shown initial success rates in the range of 80 to 100% with a 14 to 29% recurrence rate.98,99,100 There were no large territory infarctions or procedure related mortality. Adverse outcomes such as mucosal ischemia (diagnosed on endoscopy) or stricture formation did occur in up to 23% of patients; however, all of these patients were asymptomatic.99,101,102 Due to its safety profile and efficacy, most authors advocate superselective embolization as first-line angiographic therapy for lower GI bleeding.93,98,100,101,102

Surgery

Emergent or urgent operative interventions are generally reserved for patients with hemodynamic instability, massive transfusion requirements, and persistent hemorrhage despite other interventional methods of cessation.103 Although most patients will not require surgical intervention, ∼18 to 25% of patients will.20,104

Specific situations such as bleeding in the setting of cancer or inflammatory bowel disease may change the typical decision-making process. Massive hemorrhage may force an emergent operation in a patient that would otherwise undergo neoadjuvant therapy for a rectal cancer. Likewise, active bleeding and hemodynamic instability may create a situation where a planned two-stage procedure for ulcerative colitis may need to be adjusted to a three-stage procedure.

The procedure of choice when continued bleeding cannot be localized despite multiple different tests begins with an exploratory laparotomy. At the time of the operation, the entire small bowel should be examined to ensure lack of a palpable lesion that may be responsible for the bleed.105 Additionally, during exploration, a colonoscopy and/or enteroscopy can be performed, and if a bleeding lesion is found, may allow for a targeted resection.106,107,108,109 If the source of bleeding is not identified despite these measures and is suspected to be colonic in origin, then a “blind” subtotal colectomy with ileostomy or ileoproctostomy should be performed. In most series, the rebleeding rate after blind subtotal colectomy is less than 4%.57,110,111,112 Historically, subtotal colectomy has been associated with mortality rates in the range of 20 to 50%.57,111,113,114 Over time, this has improved and in more recent series the reported mortality is in the range of 2 to 6%.110,115 The reason for this decrease is likely multifactorial and may be related, in part, to the overall improvement in ICU care. Additionally, as demonstrated in one study in which the mortality from subtotal colectomy dropped from 27% to 7% when performed in patients requiring less than 10 units of blood, timely operative intervention likely also plays a major role in reducing this mortality.116

The decision to perform a blind segmental resection of the left or sigmoid colon is only discussed to admonish against its use. Before the recognition of the prevalence of right-sided sources of bleeding, it was thought that the vast majority of the sources of bleeding were left-sided. In this setting, blind segmental resections have mortality rates in the range of 30 to 57% with unacceptably high rebleeding rates from 33 to 75%.112,117,118,119

When the site of bleeding has been localized (in the colon), but is unable to be managed with endoscopic or angiographic methods, most authors suggest a “targeted” segmental colectomy.45,120,121 This recommendation is based on the relatively low rebleeding rates of 4 to 14% (in targeted segmental colectomy) in conjunction with the historically high mortality rates for subtotal colectomy.57,111,112,113 More recent studies demonstrating much lower mortality rates for subtotal colectomy have prompted some to recommend subtotal colectomy as the procedure of choice, once colonic bleeding has been localized. In these studies, there were no significant differences in the number of units transfused, frequency of bowel movements postoperatively, or mortality, with a lower rebleeding rate for subtotal colectomy versus targeted segmental colectomy.110,117

The importance of preoperative anoscopy and rigid proctoscopy cannot be overemphasized as demonstrated by a series of six patients who underwent subtotal colectomy for presumed diverticular hemorrhage and were found (after continued bleeding) to have a source in the anorectum: one from bleeding hemorrhoids and one from a solitary rectal ulcer.114

Algorithm

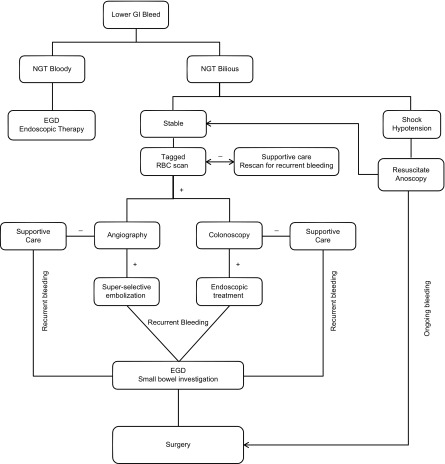

The choice of which diagnostic and/or therapeutic tests to perform on the patient presenting with hematochezia will depend primarily on the (emergent) availability of these resources. There has been only one prospective, randomized controlled trial comparing urgent colonoscopy to a “standard-care” pathway that included tagged-RBC scan followed by angiography. This trial had to be terminated early due to failure to recruit enough patients. Though it was statistically underpowered, there was no significant difference in rebleeding rate, hospital length of stay, or requirement of surgery between the two groups.38 A proposed algorithm for the workup and management of hematochezia, used at our institution is included (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Conclusion

Massive lower GI bleeding is an emergency, but should be evaluated in a methodical, step-wise manner. The age of the patient can help focus the diagnostic workup. Accurate localization of the bleeding source is critically important. The choice of diagnostic and therapeutic methods will depend on the clinical situation, bleeding rate, and availability of resources. In the rare situation of colonic bleeding that cannot be more specifically localized, subtotal colectomy is a safe choice and should be performed promptly.

References

- 1.Parker D R, Luo X, Jalbert J J, Assaf A R. Impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal blood loss on healthcare utilization and costs: a systematic review. J Media Econ. 2011;14(3):279–287. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.571328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whelan C T, Chen C, Kaboli P, Siddique J, Prochaska M, Meltzer D O. Upper versus lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a direct comparison of clinical presentation, outcomes, and resource utilization. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(3):141–147. doi: 10.1002/jhm.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prakash C, Zuckerman G R. Acute small bowel bleeding: a distinct entity with significantly different economic implications compared with GI bleeding from other locations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(3):330–335. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Encinosa W. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Hospitalizations for gastrointestinal bleeding in 1998 and 2006. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Brief #5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrell J J Friedman L S Gastrointestinal bleeding in the elderly Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2001302377–407., viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGuire H H Jr, Haynes B W Jr. Massive hemorrhage for diverticulosis of the colon: guidelines for therapy based on bleeding patterns observed in fifty cases. Ann Surg. 1972;175(6):847–855. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197206010-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuire H H Jr. Bleeding colonic diverticula. A reappraisal of natural history and management. Ann Surg. 1994;220(5):653–656. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199411000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potter G D, Sellin J H. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1988;17(2):341–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsagas M I, Fatouros M, Koulouras B, Giannoukas A D. Incidence, complications, and management of Meckel's diverticulum. Arch Surg. 1995;130(2):143–146. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430020033003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackey W C, Dineen P. A fifty year experience with Meckel's diverticulum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1983;156(1):56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ymaguchi M, Takeuchi S, Awazu S. Meckel's diverticulum. Investigation of 600 patients in Japanese literature. Am J Surg. 1978;136(2):247–249. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yahchouchy E K, Marano A F, Etienne J C, Fingerhut A L. Meckel's diverticulum. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192(5):658–662. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00817-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elitsur Y, Teitelbaum J E, Rewalt M, Nowicki M. Clinical and endoscopic data in juvenile polyposis syndrome in preadolescent children: a multicenter experience from the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(8):734–736. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181956e0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robert J R, Sachar D B, Greenstein A J. Severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage in Crohn's disease. Ann Surg. 1991;213(3):207–211. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199103000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robert J H, Sachar D B, Aufses A H Jr, Greenstein A J. Management of severe hemorrhage in ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg. 1990;159(6):550–555. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(06)80064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuckerman G R, Prakash C. Acute lower intestinal bleeding: part I: clinical presentation and diagnosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48(6):606–617. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinus J F, Brandt L J. Vascular ectasias and diverticulosis. Common causes of lower intestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1994;23(1):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGuire H H Jr, Haynes B W Jr. Massive hemorrhage for diverticulosis of the colon: guidelines for therapy based on bleeding patterns observed in fifty cases. Ann Surg. 1972;175(6):847–855. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197206010-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong S K, Ho Y H, Leong A P, Seow-Choen F. Clinical behavior of complicated right-sided and left-sided diverticulosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(3):344–348. doi: 10.1007/BF02050427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGuire H H Jr. Bleeding colonic diverticula. A reappraisal of natural history and management. Ann Surg. 1994;220(5):653–656. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199411000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casarella W J, Kanter I E, Seaman W B. Right-sided colonic diverticula as a cause of acute rectal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 1972;286(9):450–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197203022860902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyers M A, Alonso D R, Gray G F, Baer J W. Pathogenesis of bleeding colonic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology. 1976;71(4):577–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boley S J, Sammartano R, Adams A, DiBiase A, Kleinhaus S, Sprayregen S. On the nature and etiology of vascular ectasias of the colon. Degenerative lesions of aging. Gastroenterology. 1977;72(4 Pt 1):650–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King R M, Pluth J R, Giuliani E R. The association of unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding with calcific aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1987;44(5):514–516. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imperiale T F, Ransohoff D F. Aortic stenosis, idiopathic gastrointestinal bleeding, and angiodysplasia: is there an association? A methodologic critique of the literature. Gastroenterology. 1988;95(6):1670–1676. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olearchyk A S. Heyde's syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;103(4):823–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batur P, Stewart W J, Isaacson J H. Increased prevalence of aortic stenosis in patients with arteriovenous malformations of the gastrointestinal tract in Heyde syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(15):1821–1824. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.15.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breen E, Murray J. Pathophysiology and natural history of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Semin Colon Rectal Surg. 1997;8:128–138. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen L, Bub D S, Reed J F III, Nastasee S A. Hemorrhage following colonoscopic polypectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(12):1126–1131. doi: 10.1007/BF02052261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuckerman G R, Prakash C. Acute lower intestinal bleeding. Part II: etiology, therapy, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49(2):228–238. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laine L Shah A Randomized trial of urgent vs. elective colonoscopy in patients hospitalized with lower GI bleeding Am J Gastroenterol 2010105122636–2641., quiz 2642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen D M, Machicado G A. Diagnosis and treatment of severe hematochezia. The role of urgent colonoscopy after purge. Gastroenterology. 1988;95(6):1569–1574. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozdil B, Akkiz H, Sandikci M, Kece C, Cosar A. Massive lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage secondary to rectal hemorrhoids in elderly patients receiving anticoagulant therapy: case series. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(9):2693–2694. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peter P, Deyhle P, Brändli H. et al. [Endoscopic diagnosis of acute perianal hemorrhage] Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1976;106(26):880–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green B T, Rockey D C, Portwood G. et al. Urgent colonoscopy for evaluation and management of acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2395–2402. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caos A, Benner K G, Manier J. et al. Colonoscopy after Golytely preparation in acute rectal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8(1):46–49. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198602000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossini F P, Ferrari A, Spandre M. et al. Emergency colonoscopy. World J Surg. 1989;13(2):190–192. doi: 10.1007/BF01658398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green B T, Rockey D C, Portwood G. et al. Urgent colonoscopy for evaluation and management of acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2395–2402. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen D M, Machicado G A. Diagnosis and treatment of severe hematochezia. The role of urgent colonoscopy after purge. Gastroenterology. 1988;95(6):1569–1574. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jensen D M, Machicado G A, Jutabha R, Kovacs T O. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(2):78–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laine L. Multipolar electrocoagulation in the treatment of active upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage. A prospective controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(26):1613–1617. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706253162601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cook D J, Guyatt G H, Salena B J, Laine L A. Endoscopic therapy for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102(1):139–148. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laine L Shah A Randomized trial of urgent vs. elective colonoscopy in patients hospitalized with lower GI bleeding Am J Gastroenterol 2010105122636–2641., quiz 2642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strate L L. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):643–664. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoedema R E, Luchtefeld M A. The management of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(11):2010–2024. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howarth D M. The role of nuclear medicine in the detection of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Semin Nucl Med. 2006;36(2):133–146. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Currie G M, Towers P A, Wheat J M. Improved detection and localization of lower gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage by subtraction scintigraphy: phantom analysis. J Nucl Med Technol. 2006;34(3):160–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alavi A, Dann R W, Baum S, Biery D N. Scintigraphic detection of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Radiology. 1977;124(3):753–756. doi: 10.1148/124.3.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hunter J M, Pezim M E. Limited value of technetium 99m-labeled red cell scintigraphy in localization of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Surg. 1990;159(5):504–506. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nicholson M L, Neoptolemos J P, Sharp J F, Watkin E M, Fossard D P. Localization of lower gastrointestinal bleeding using in vivo technetium-99m-labelled red blood cell scintigraphy. Br J Surg. 1989;76(4):358–361. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Voeller G R, Bunch G, Britt L G. Use of technetium-labeled red blood cell scintigraphy in the detection and management of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Surgery. 1991;110(4):799–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gunderman R, Leef J, Ong K, Reba R, Metz C. Scintigraphic screening prior to visceral arteriography in acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(6):1081–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nusbaum M, Baum S. Radiographic demonstration of unknown sites of gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Forum. 1963;14:374–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feldkamp T, Baumgart D, Elsner M. et al. Nephrotoxicity of iso-osmolar versus low-osmolar contrast media is equal in low risk patients. Clin Nephrol. 2006;66(5):322–330. doi: 10.5414/cnp66322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heinrich M C, Häberle L, Müller V, Bautz W, Uder M. Nephrotoxicity of iso-osmolar iodixanol compared with nonionic low-osmolar contrast media: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiology. 2009;250(1):68–86. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2501080833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zuckerman D A, Bocchini T P, Birnbaum E H. Massive hemorrhage in the lower gastrointestinal tract in adults: diagnostic imaging and intervention. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161(4):703–711. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.4.8372742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leitman I M, Paull D E, Shires G T III. Evaluation and management of massive lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Ann Surg. 1989;209(2):175–180. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198902000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nath R L, Sequeira J C, Weitzman A F, Birkett D H, Williams L F Jr. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Diagnostic approach and management conclusions. Am J Surg. 1981;141(4):478–481. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(81)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koval G, Benner K G, Rösch J, Kozak B E. Aggressive angiographic diagnosis in acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32(3):248–253. doi: 10.1007/BF01297049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rösch J, Kozak B E, Keller F S, Dotter C T. Interventional angiography in the diagnosis of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Eur J Radiol. 1986;6(2):136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim C Y, Suhocki P V, Miller M J Jr, Khan M, Janus G, Smith T P. Provocative mesenteric angiography for lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: results from a single-institution study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(4):477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ryan J M, Key S M, Dumbleton S A, Smith T P. Nonlocalized lower gastrointestinal bleeding: provocative bleeding studies with intraarterial tPA, heparin, and tolazoline. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(11):1273–1277. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bloomfeld R S, Smith T P, Schneider A M, Rockey D C. Provocative angiography in patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage of obscure origin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(10):2807–2812. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jaeckle T, Stuber G, Hoffmann M HK, Jeltsch M, Schmitz B L, Aschoff A J. Detection and localization of acute upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding with arterial phase multi-detector row helical CT. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(7):1406–1413. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0907-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jain T P, Gulati M S, Makharia G K, Bandhu S, Garg P K. CT enteroclysis in the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: initial results. Clin Radiol. 2007;62(7):660–667. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoon W, Jeong Y Y, Shin S S. et al. Acute massive gastrointestinal bleeding: detection and localization with arterial phase multi-detector row helical CT. Radiology. 2006;239(1):160–167. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2383050175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huprich J E, Fletcher J G, Alexander J A, Fidler J L, Burton S S, McCullough C H. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: evaluation with 64-section multiphase CT enterography—initial experience. Radiology. 2008;246(2):562–571. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462061920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Al-Saeed O, Kombar O, Morsy M, Sheikh M. Sixty-four multi-detector computerised tomography in the detection of lower gastrointestinal bleeding: A prospective study. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2011;55(3):252–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2011.02261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ell C, Remke S, May A, Helou L, Henrich R, Mayer G. The first prospective controlled trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002;34(9):685–689. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cuyle P J, Schoofs N, Bossuyt P. et al. Single-centre experience on use of videocapsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding in 120 consecutive patients. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74(3):400–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lewis B S, Swain P. Capsule endoscopy in the evaluation of patients with suspected small intestinal bleeding: results of a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(3):349–353. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arakawa D, Ohmiya N, Nakamura M. et al. Outcome after enteroscopy for patients with obscure GI bleeding: diagnostic comparison between double-balloon endoscopy and videocapsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(4):866–874. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hadithi M, Heine G DN, Jacobs M AJM, Bodegraven A A van, Mulder C J. A prospective study comparing video capsule endoscopy with double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(1):52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ohmiya N, Yano T, Yamamoto H. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of obscure GI bleeding at double balloon endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(3, Suppl):S72–S77. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fujimori S, Seo T, Gudis K. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding using combined capsule endoscopy and double balloon endoscopy: 1-year follow-up study. Endoscopy. 2007;39(12):1053–1058. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-967014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kamalaporn P, Cho S, Basset N. et al. Double-balloon enteroscopy following capsule endoscopy in the management of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: outcome of a combined approach. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(5):491–495. doi: 10.1155/2008/942731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pata C, Akyüz Ü, Erzın Y, Mercan A. Double-balloon enteroscopy: the diagnosis and management of small bowel diseases. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21(4):353–359. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2010.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sfakianakis G N, Haase G M. Abdominal scintigraphy for ectopic gastric mucosa: a retrospective analysis of 143 studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;138(1):7–12. doi: 10.2214/ajr.138.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lin S, Suhocki P V, Ludwig K A, Shetzline M A. Gastrointestinal bleeding in adult patients with Meckel's diverticulum: the role of technetium 99m pertechnetate scan. South Med J. 2002;95(11):1338–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Green B T, Rockey D C. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding—management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Olmos J A, Marcolongo M, Pogorelsky V, Herrera L, Tobal F, Dávolos J R. Long-term outcome of argon plasma ablation therapy for bleeding in 100 consecutive patients with colonic angiodysplasia. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(10):1507–1516. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0684-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Naveau S, Aubert A, Poynard T, Chaput J C. Long-term results of treatment of vascular malformations of the gastrointestinal tract by neodymium YAG laser photocoagulation. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35(7):821–826. doi: 10.1007/BF01536794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chak A, Koehler M K, Sundaram S N, Cooper G S, Canto M I, Sivak M V Jr. Diagnostic and therapeutic impact of push enteroscopy: analysis of factors associated with positive findings. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47(1):18–22. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Askin M P, Lewis B S. Push enteroscopic cauterization: long-term follow-up of 83 patients with bleeding small intestinal angiodysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43(6):580–583. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rutgeerts P, Gompel F Van, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Broeckaert L, Coremans G. Long term results of treatment of vascular malformations of the gastrointestinal tract by neodymium Yag laser photocoagulation. Gut. 1985;26(6):586–593. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.6.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jensen D M, Machicado G A. Colonoscopy for diagnosis and treatment of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Routine outcomes and cost analysis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7(3):477–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bloomfeld R S Shetzline M Rockey D Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage N Engl J Med 2000342211608–1609., author reply 1610–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jensen D M, Machicado G A, Jutabha R, Kovacs T O. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(2):78–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hokama A, Uehara T, Nakayoshi T. et al. Utility of endoscopic hemoclipping for colonic diverticular bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(3):543–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ohyama T, Sakurai Y, Ito M, Daito K, Sezai S, Sato Y. Analysis of urgent colonoscopy for lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Digestion. 2000;61(3):189–192. doi: 10.1159/000007756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Simpson P W, Nguyen M H, Lim J K, Soetikno R M. Use of endoclips in the treatment of massive colonic diverticular bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(3):433–437. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02711-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Baum S, Nusbaum M. The control of gastrointestinal hemorrhage by selective mesenteric arterial infusion of vasopressin. Radiology. 1971;98(3):497–505. doi: 10.1148/98.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Darcy M. Treatment of lower gastrointestinal bleeding: vasopressin infusion versus embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14(5):535–543. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000064862.65229.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rösch J, Dotter C T, Brown M J. Selective arterial embolization. A new method for control of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Radiology. 1972;102(2):303–306. doi: 10.1148/102.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Browder W, Cerise E J, Litwin M S. Impact of emergency angiography in massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Surg. 1986;204(5):530–536. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198611000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Uflacker R. Transcatheter embolization for treatment of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Acta Radiol. 1987;28(4):425–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rosenkrantz H, Bookstein J J, Rosen R J, Goff W B II, Healy J F. Postembolic colonic infarction. Radiology. 1982;142(1):47–51. doi: 10.1148/radiology.142.1.6975953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Peck D J, McLoughlin R F, Hughson M N, Rankin R N. Percutaneous embolotherapy of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1998;9(5):747–751. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(98)70386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kuo W T, Lee D E, Saad W EA, Patel N, Sahler L G, Waldman D L. Superselective microcoil embolization for the treatment of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14(12):1503–1509. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000099780.23569.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ledermann H P, Schoch E, Jost R, Decurtins M, Zollikofer C L. Superselective coil embolization in acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage: personal experience in 10 patients and review of the literature. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1998;9(5):753–760. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(98)70387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nicholson A A, Ettles D F, Hartley J E. et al. Transcatheter coil embolotherapy: a safe and effective option for major colonic haemorrhage. Gut. 1998;43(1):79–84. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ahmed T M, Cowley J B, Robinson G. et al. Long term follow-up of transcatheter coil embolotherapy for major colonic haemorrhage. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(10):1013–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schuetz A, Jauch K W. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding: therapeutic strategies, surgical techniques and results. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2001;386(1):17–25. doi: 10.1007/s004230000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bokhari M, Vernava A M, Ure T, Longo W E. Diverticular hemorrhage in the elderly—is it well tolerated? Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(2):191–195. doi: 10.1007/BF02068074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Billingham R P. The conundrum of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77(1):241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70542-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cussons P D, Berry A R. Comparison of the value of emergency mesenteric angiography and intraoperative colonoscopy with antegrade colonic irrigation in massive rectal haemorrhage. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1989;34(2):91–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Campbell W B, Rhodes M, Kettlewell M G. Colonoscopy following intraoperative lavage in the management of severe colonic bleeding. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1985;67(5):290–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Flickinger E G, Stanforth A C, Sinar D R, MacDonald K G, Lannin D R, Gibson J H. Intraoperative video panendoscopy for diagnosing sites of chronic intestinal bleeding. Am J Surg. 1989;157(1):137–144. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Desa L A, Ohri S K, Hutton K A, Lee H, Spencer J. Role of intraoperative enteroscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding of small bowel origin. Br J Surg. 1991;78(2):192–195. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Farner R, Lichliter W, Kuhn J, Fisher T. Total colectomy versus limited colonic resection for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Surg. 1999;178(6):587–591. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Britt L G, Warren L, Moore O F III. Selective management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am Surg. 1983;49(3):121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Parkes B M, Obeid F N, Sorensen V J, Horst H M, Fath J J. The management of massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am Surg. 1993;59(10):676–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Colacchio T A, Forde K A, Patsos T J, Nunez D. Impact of modern diagnostic methods on the management of active rectal bleeding. Ten year experience. Am J Surg. 1982;143(5):607–610. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gianfrancisco J A, Abcarian H. Pitfalls in the treatment of massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding with “blind” subtotal colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25(5):441–445. doi: 10.1007/BF02553650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Baker R Senagore A Abdominal colectomy offers safe management for massive lower GI bleed Am Surg 1994608578–581., discussion 582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bender J S Wiencek R G Bouwman D L Morbidity and mortality following total abdominal colectomy for massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding Am Surg 1991578536–540., discussion 540–541 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Baker R Senagore A Abdominal colectomy offers safe management for massive lower GI bleed Am Surg 1994608578–581., discussion 582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Eaton A C. Emergency surgery for acute colonic haemorrhage—a retrospective study. Br J Surg. 1981;68(2):109–112. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800680214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Drapanas T, Pennington D G, Kappelman M, Lindsey E S. Emergency subtotal colectomy: preferred approach to management of massively bleeding diverticular disease. Ann Surg. 1973;177(5):519–526. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197305000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Farrell J J, Friedman L S. Review article: the management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(11):1281–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lee J, Costantini T W, Coimbra R. Acute lower GI bleeding for the acute care surgeon: current diagnosis and management. Scand J Surg. 2009;98(3):135–142. doi: 10.1177/145749690909800302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Billingham R P. The conundrum of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77(1):241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70542-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]