Abstract

With the recent discovery of a unique class of dual-specificity phosphatases that dephosphorylate glucans, we report an in vitro assay tailored for the detection of phosphatase activity against phosphorylated glucans. We demonstrate that in contrast to a general phosphatase assay utilizing a synthetic substrate, only phosphatases that possess glucan phosphatase activity liberate phosphate from the phosphorylated glucan amylopectin using the described assay. This assay is simple and cost-effective, providing reproducible results that clearly establish the presence or absence of glucan phosphatase activity. The assay described will be a useful tool in characterizing emerging members of the glucan phosphatase family.

Keywords: Glucan, Phosphatase, Malachite green, Amylopectin, Glycogen, Starch

Glucan phosphatases are a unique class of recently discovered dual-specificity phosphatases (DSPs) present in the genomes of all mammals, some invertebrates, some protists, and all plants that remove phosphate from starch or glycogen [1–6]. DSPs are part of the larger protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) superfamily and include phosphatases with a heterogeneous array of substrates, including phosphoserine, threonine, and tyrosine residues of proteins as well as phosphatidylinositols, glycerophospholipids, mRNA, and glucans/carbohydrates [5,7–9]. As the PTPs play important roles in many cell-signaling events, the identification of physiological substrates for emerging DSPs is crucial. In vitro assays utilizing artificial substrates are useful for comparing enzyme kinetics, while biologically relevant substrates are necessary to compare activity within a phosphatase family (e.g. glucan phosphatases).

Many DSPs possess in vitro phosphatase activity towards phosphate esters of Ser, Thr, and Tyr of synthetic peptides [10–12], as well as towards synthetic small molecule substrates such as para-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP), 3-O-methylfluorescein phosphate (OMFP), fluorescein diphosphate (FDP), and 6,8-difluoro-4-methylumbellyferyl phosphate (DiFMUP) [10,12]. Hydrolysis of the aryl phosphate moiety from the small molecule pNPP converts this colorless substrate into para-nitrophenol, which reacts with a strong base to form the bright yellow phenolate ion that can be observed by reading the absorbance at 410 nm (Fig. 1A). Using a synthetic small molecule, one can determine the dephosphorylation kinetics and specificity constants/catalytic efficiencies of a phosphatase, and then compare these values to other phosphatases in the literature. This type of analysis can provide valuable insights into the substrate of the phosphatase. A prime example of this methodology was work on the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN). In vitro experiments using recombinant PTEN revealed it to be ~1000-fold less active against the phosphotyrosine analog para-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) than typical tyrosine-specific PTPs. These results prompted the search for other substrates that ultimately led to the important discovery that PTEN is a phosphoinositide lipid phosphatase [13].

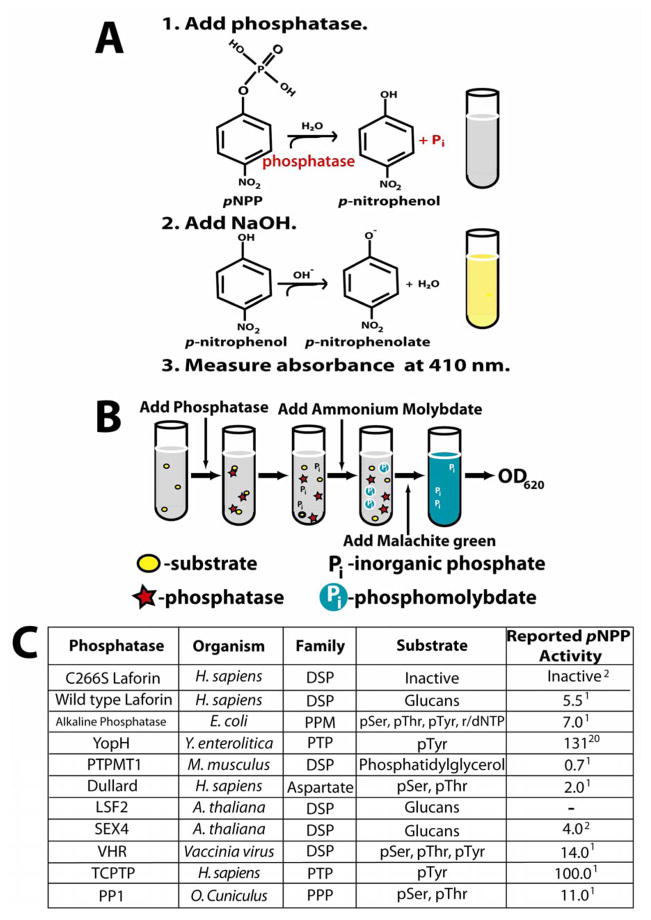

Figure 1. Experimental design of assays and phosphatases chosen for study.

A. The pNPP assay. Hydrolysis of the aryl phosphate moiety from the small molecule para-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) converts this colorless substrate into para-nitrophenol, which forms the bright yellow phenolate ion under alkaline conditions (pKa of 7.2). The presence of the soluble phenolate ion can be observed by reading the absorbance at 410 nm. When performing this colorimetric assay under saturation conditions of substrate as we have done, it is possible to calculate the rate of dephosphorylation as well as kinetic constants such as kcat and KM [10,12]. While pNPP is an artificial substrate, the small size of this molecule restricts interaction to a low number of residues, allowing resolution of active site conformation changes due to mutation [12]. Phosphatase assays involving these substrates can be performed in a continuous or discontinuous fashion. Continuous enzyme assays, allowing hydrolysis products to be quantified without disturbing the reaction, are superior to discontinuous assays in the efficiency of determining kinetic constants [10]. However, for the purpose of this work, discontinuous assay under saturated conditions was sufficient (10 times the Km) [12], providing the initial (linear) rate of the reaction for phosphatase activity comparison.

B. The malachite green assay utilizing amylopectin as a substrate. As phosphate monoesters in amylopectin are hydrolyzed, the free phosphate forms a complex with the ammonium molybdate in the malachite green reagent. At low pH, the basic malachite green dye forms a complex with phosphomolybdate and shifts to its absorption maximum. This complex is stabilized for up to 48 hours by detergents such as Tween 20 [27], allowing for easy colorimetric detection that is linear with as little as 50 to 1000 pmol of Pi following measurement of the absorbance at 620 nm [15]. While it is not possible to calculate enzyme kinetics using the heterogeneous amylopectin polymer, use of amylopectin as a substrate allows for the detection of glucan phosphatase activity. For both the malachite green and pNPP assay, dithiothreitol (DTT) was used as the reducing agent to maintain enzyme activity as malachite green is sensitive to 2-mercaptoethanol [14].

C. List of phosphatases used in the pNPP and malachite green assays. Phosphatases across families and within families were chosen to obtain a representative and diverse collection of enzymes for study. Included in the list is the family and organism of origin and the known substrates and reported specific activity against pNPP (μmol/min/mg) for each enzyme.

In addition to assays utilizing artificial substrates, there are in vitro assays that assess phosphatase activity against biologically relevant substrates [1,10,14,15]. Malachite green is a useful reagent in this regard, allowing colorimetric detection of picomolar amounts of inorganic phosphate due to the formation of a phosphomolybdate malachite green complex (Fig. 1B) [10,15,16]. In addition to the advantages of simplicity and sensitivity, malachite green assays have been utilized to detect phosphate released from an array of endogenous substrates such as proteins and lipids [10,14]. Herein, we describe a glucan phosphatase assay that utilizes malachite green in conjunction with the phosphorylated glucose polymer amylopectin. This assay effectively separates enzymes with glucan phosphatase activity from those that lack the activity.

First, we purified the following glucan phosphatases: human wild-type laforin and a catalytically inactive mutant serving as an experimental control (C266S), Arabidopsis thaliana Starch EXcess4 (SEX4), and Arabidopsis thaliana Like Sex Four2 (LSF2) as previously described [2,6]. We also purified or purchased phosphatases from a variety of different organisms and phosphatase families [17–20]. We utilized the phosphoprotein phosphatase (PPP) family member Oryctolagus cuniculus protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) [5], the human aspartate-based phosphatase family member Dullard [5,21], and the Escherichia coli metallo-dependent protein phosphatase (PPM) family member alkaline phosphatase [22] (Fig 1C). We also employed enzymes from subfamilies within the PTP superfamily: classical PTPs such as human T-cell PTP (TCPTP) [5,23] and Yersinia pestis YopH [24,25], and dual-specificity phosphatases (DSPs) such as vaccinia virus VH1-related DSP (VHR) [2] and murine PTP localized to mitochondrion 1 (PTPMT1) [26] (Fig. 1C). These phosphatases have all previously been shown to possess phosphatase activity against substrates such as pNPP, phosphorylated peptides, phosphorylated glucans, or phospholipids [1,2,6,21–24,26].

To ensure that each phosphatase we included in our work was active, we first performed phosphatase reactions with each using the small molecule pNPP (see Supplementary Material, Protocol #1). Aliquots of 5X assay buffer (100 mM sodium acetate, 50 mM Bis-Tris, 50 mM Tris) were prepared for each pH to be tested, and enzymes were diluted with 1X assay buffer containing 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) to a final enzyme concentration ranging from 50 to 1000ng/μl. Each reaction replicate (at least 3) was performed in a final volume of 50 μl, and consisted of 33 μl H2O, 10 μl 5X assay buffer at the optimal pH, 1 μl 100mM DTT, and 5 μl 0.5 M pNPP. We added 1 μl of diluted enzyme to each replicate tube, began timing the reaction, vortexed the tube, and then placed it at 37°C. We repeated this methodology every 15 seconds until enzyme was added to each replicate. After a reaction time of 10 minutes at 37°C, we added 200 μl of 0.25 N NaOH and vortexed the tubes to quench the reactions, and read the absorbance (A) of each replicate at 410 nm. We then utilized Beer’s Law (A=εlc, where the path length l = 1 cm) and the molar absorption coefficient (ε) of the phenolate ion under our reaction conditions (17,800 M−1 cm−1) to determine the concentration in moles per liter (c) of phenolate ion generated per reaction and finally the activity of each enzyme, expressed as μmol phosphate released/min/μmol protein. Although it is common to report phosphatase activity in terms of total protein, when comparing phosphatases of different molecular weights one must compare moles of protein (Fig. 2A). However, we also provide our results in terms of total protein (Supp. Fig. 1A) for comparison with previously published activity data (Fig. 1C). All of the phosphatases tested exhibited activity against pNPP (Supp. Fig. 1A) that closely reflected previously published data at the optimal pH for each enzyme (Fig. 1C).

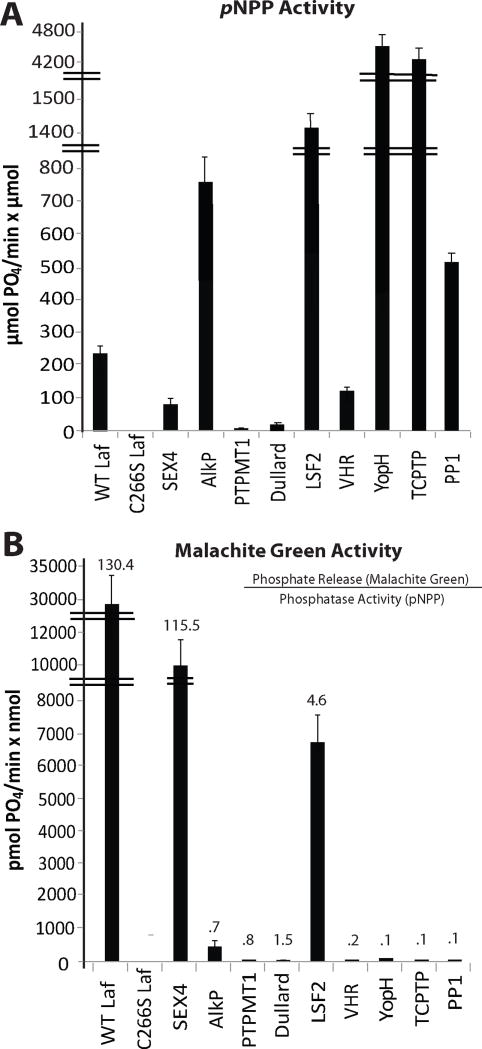

Figure 2. The pNPP and malachite green assays reveal specific glucan phosphatase activity only in glucan phosphatases.

A. pNPP activity. The activity of each phosphatase utilized in our study against the synthetic substrate pNPP in μmol phosphate released per minute per μmol protein. Each assay was independently repeated with four replicates. All enzymes present with generic phosphatase activity against pNPP. Error bars; S.E.

B. Glucan phosphatase activity. The specific activity of the same phosphatases against phosphorylated amylopectin in pmol phosphate released per minute per nmol protein. Each assay was independently repeated with four replicates. The numbers above the bars are the ratio of phosphate release (malachite green assay) to the phosphatase activity (pNPP assay) for each enzyme. Only the reported glucan phosphatases demonstrate activity against the glucan substrate amylopectin. Error bars; S.E.

Next, we employed a malachite green assay to assess specific glucan phosphatase activity of the above enzymes at optimal pH using the phosphorylated glucan amylopectin as the substrate (see Supplementary Material, Protocol #2). First, we prepared the malachite green reagent. We began with 1 volume of 4.2% ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate in 4N HCl, added 3 volumes of 0.045% malachite green carbinol hydrochloride, stirred the solution for 30 minutes, filtered the solution with grade 5 Whatman filter paper, and then sterile-filtered the reagent. Prior to performing experiments with the reagent, a standard curve should be generated (see Supplementary Material, Protocol #2). Next, we prepared the amylopectin to be used as the phosphoglucan substrate. Amylopectin is largely water insoluble, therefore it must be solubilized via heating or ethanol. We prepared a suspension of 5 mg/mL of amylopectin in H2O, heated the suspension at 70°C for 30 minutes (the suspension will go from opaque to clear; vortexing aids solubility), and stored this solution at room temperature.

Before beginning the malachite green assay, we first added 0.01% (v/v) Tween 20 from a 10% stock to an aliquot of malachite green reagent. Tween 20 stabilizes the formation of the malachite green phosphomolybdate complex and prevents sedimentation of the complex for up to 48 hours [27]. We then prepared 5X assay buffer (100 mM sodium acetate, 50 mM Bis-Tris, 50 mM Tris) for each pH to be tested and diluted enzymes with 1X assay buffer with 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) added to a final enzyme concentration ranging from 50 to 1000ng/μl. Each reaction (at least 3 replicates) was then performed in a final volume of 20 μl consisting of 4 μl H2O, 4 μl 5X assay buffer at the optimal enzyme pH, 2 μl 100 mM of DTT, and 9 μl of 5 mg/mL amylopectin. We added 1 μl of diluted enzyme to each reaction tube, began timing the reaction, vortexed and then placed the tube at 37°C. This methodology was repeated every 15 seconds until enzyme was added to each replicate. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes before 20 μl 0.1M N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) was added to terminate all PTP reactions. NEM is a thiol-modifying reagent that irreversibly inhibits PTPs without affecting malachite green phosphomolybdate color formation [14]. For non-PTPs, addition of malachite green reagent was used to terminate the reaction [15]. Following NEM addition to the PTP reaction tubes, 80 μl of the malachite green reagent containing Tween20 was then added. After malachite green reagent was added to every reaction tube, the tubes were vortexed and placed at room temperature. All reactions were incubated for 40 minutes before measuring the absorbance at 620 nm [27] and calculating the pmoles of phosphate released/min/nmol protein using the standard curve.

Using the above methodology, we found that only wild-type laforin, SEX4, and LSF2 exhibited glucan phosphatase activity, while all other phosphatases that we tested possessed very little to no activity (Fig. 2B and Supp. Fig. 1B). To assess the relative activity of the phosphatases tested towards amylopectin, we compared phosphate liberation from amylopectin to pNPP activity and found that only the glucan phosphatases were effective at dephosphorylating amylopectin, with laforin being the most efficient (Fig. 2B and Supp. Fig. 1B, numbers above bars). Thus, only the glucan phosphatases possess the ability to release phosphate from amylopectin. The phosphatase assay described in this work is a simple method to characterize additional emerging members of the unique and growing family of glucan phosphatases, as has been done with the recently characterized glucan phosphatase LSF2.

Supplementary Material

A. pNPP activity. The activity of each phosphatase utilized in our study against the synthetic substrate pNPP in μmol phosphate released per minute per mg protein.

B. Glucan phosphatase activity. The specific activity of the same phosphatases against phosphorylated amylopectin in pmol phosphate released per minute per μg protein.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R00NS061803, P20RR020171, and R01NS070899 and University of Kentucky College of Medicine startup funds to M.S.G. This publication was also supported by grant number TL1 RR033172 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), funded by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (NIH) and supported by the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR and NIH. We thank members from the Gentry lab and Dixon lab at UCSD, including Dr. Ji Zhang, who supplied several enzymes used in this work in addition to providing helpful information in regards to their use.

Abbreviations used

- DSP

dual-specificity phosphatase

- DiFMUP

6,8-difluoro-4-methylumbellyferyl phosphate

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- FDP

fluorescein diphosphate

- LSF2

Like SEX4 2

- OMFP

3-O-methylfluorescein phosphate

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- pNPP

para-nitrophenylphosphate

- PP1

protein phosphatase 1

- PPM

metallo-dependent protein phosphatase

- PPP

prosphoprotein phosphatase

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatase

- PTPMT1

protein tyrosine phosphatase localized to mitochondrion 1

- SEX4

Starch Excess 4

- TCPTP

T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase

- VHR

VH1-related dual-specificity phosphatase

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Worby CA, Gentry MS, Dixon JE. Laforin: A dual specificity phosphatase that dephosphorylates complex carbohydrates. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30412–30418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606117200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gentry MS, Dowen RH, 3rd, Worby CA, Mattoo S, Ecker JR, Dixon JE. The phosphatase laforin crosses evolutionary boundaries and links carbohydrate metabolism to neuronal disease. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:477–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gentry MS, Pace RM. Conservation of the glucan phosphatase laforin is linked to rates of molecular evolution and the glycogen metabolism of the organism. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tagliabracci VS, Turnbull J, Wang W, Girard JM, Zhao X, Skurat AV, Delgado-Escueta AV, Minassian BA, Depaoli-Roach AA, Roach PJ. Laforin is a glycogen phosphatase, deficiency of which leads to elevated phosphorylation of glycogen in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19262–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707952104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moorhead GB, De Wever V, Templeton G, Kerk D. Evolution of protein phosphatases in plants and animals. Biochem J. 2009;417:401–9. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santelia D, Kotting O, Seung D, Schubert M, Thalmann M, Bischof S, Meekins DA, Lutz A, Patron N, Gentry MS, Allain FH, Zeeman SC. The phosphoglucan phosphatase like sex Four2 dephosphorylates starch at the C3-position in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23:4096–111. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.092155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alonso A, Sasin J, Bottini N, Friedberg I, Friedberg I, Osterman A, Godzik A, Hunter T, Dixon J, Mustelin T. Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases in the Human Genome. Cell. 2004;117:699. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson KI, Brummer T, O’Brien PM, Daly RJ. Dual-specificity phosphatases: critical regulators with diverse cellular targets. Biochem J. 2009;418:475–89. doi: 10.1042/bj20082234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonks NK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: from genes, to function, to disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:833–46. doi: 10.1038/nrm2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCain DF, Zhang ZY. Assays for protein-tyrosine phosphatases. Methods Enzymol. 2002;345:507–18. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)45042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonso A, Rojas A, Godzik A, Mustelin T. The dual-specific protein tyrosine phosphatase family. Springer; Berlin: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montalibet J, Skorey KI, Kennedy BP. Protein tyrosine phosphatase: enzymatic assays. Methods. 2005;35:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maehama T, Dixon JE. The Tumor Suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, Dephosphorylates the Lipid Second Messenger, Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-Trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maehama T, Taylor GS, Slama JT, Dixon JE. A Sensitive Assay for Phosphoinositide Phosphatases. Analytical Biochemistry. 2000;279:248–250. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harder KW, Owen P, Wong LK, Aebersold R, Clark-Lewis I, Jirik FR. Characterization and kinetic analysis of the intracellular domain of human protein tyrosine phosphatase beta (HPTP beta) using synthetic phosphopeptides. Biochem J. 1994;298(Pt 2):395–401. doi: 10.1042/bj2980395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanzetta PA, Alvarez LJ, Reinach PS, Candia OA. An improved assay for nanomole amounts of inorganic phosphate. Anal Biochem. 1979;100:95–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bollen M, Peti W, Ragusa MJ, Beullens M. The extended PP1 toolkit: designed to create specificity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy J, Cyert MS. Cracking the phosphatase code: docking interactions determine substrate specificity. Sci Signal. 2009;2:re9. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2100re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Y. Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell. 2009;139:468–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Virshup DM, Shenolikar S. From promiscuity to precision: protein phosphatases get a makeover. Mol Cell. 2009;33:537–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y, Gentry MS, Harris TE, Wiley SE, Lawrence JC, Jr, Dixon JE. A conserved phosphatase cascade that regulates nuclear membrane biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6596–601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702099104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman JE. Structure and mechanism of alkaline phosphatase. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1992;21:441–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asante-Appiah E, Ball K, Bateman K, Skorey K, Friesen R, Desponts C, Payette P, Bayly C, Zamboni R, Scapin G, Ramachandran C, Kennedy BP. The YRD motif is a major determinant of substrate and inhibitor specificity in T-cell protein-tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26036–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan KL, Dixon JE. Bacterial and viral protein tyrosine phosphatases. Semin Cell Biol. 1993;4:389–96. doi: 10.1006/scel.1993.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang ZY, Clemens JC, Schubert HL, Stuckey JA, Fischer MW, Hume DM, Saper MA, Dixon JE. Expression, purification, and physicochemical characterization of a recombinant Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23759–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao J, Engel JL, Zhang J, Chen MJ, Manning G, Dixon JE. Structural and functional analysis of PTPMT1, a phosphatase required for cardiolipin synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11860–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109290108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itaya K, Ui M. A new micromethod for the colorimetric determination of inorganic phosphate. Clin Chim Acta. 1966;14:361–6. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(66)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. pNPP activity. The activity of each phosphatase utilized in our study against the synthetic substrate pNPP in μmol phosphate released per minute per mg protein.

B. Glucan phosphatase activity. The specific activity of the same phosphatases against phosphorylated amylopectin in pmol phosphate released per minute per μg protein.