Abstract

The role of mononuclear phagocytes in the pathogenesis or control of HIV infection is unclear. Here, we monitored the dynamics and function of dendritic cells (DC) and monocytes/macrophages in rhesus macaques acutely infected with pathogenic SIVmac251 with and without antiretroviral therapy (ART). SIV infection was associated with monocyte mobilization and recruitment of plasmacytoid DC (pDC) and macrophages to lymph nodes which did not occur with ART treatment. SIVmac251 single-stranded RNA encoded several uridine-rich sequences that were potent TLR7/8 ligands in mononuclear phagocytes of naive animals, stimulating myeloid DC (mDC) and monocytes to produce TNF-α and pDC and macrophages to produce both TNF-α and IFN-α. Following SIV infection pDC and monocytes/macrophages rapidly became hyporesponsive to stimulation with SIV-encoded TLR ligands and influenza virus, a condition that was reversed by ART. The loss of pDC and macrophage function was associated with a profound but transient block in the capacity of lymph node cells to secrete IFN-α upon stimulation. In contrast to pDC and monocytes/macrophages, mDC increased TNF-α production in response to stimulation following acute infection. Moreover, SIV-infected rhesus macaques with stable infection had increased mDC responsiveness to SIV-encoded TLR ligands and influenza virus at set-point, whereas animals that progressed rapidly to AIDS had reduced mDC responsiveness. These findings indicate that SIV encodes immunostimulatory TLR ligands and that pDC, mDC and monocytes/macrophages respond to these ligands differently as a function of SIV infection. The data also suggest that increased responsiveness of mDC to stimulation following SIV infection may be beneficial to the host.

Introduction

Mononuclear phagocytes, including dendritic cells (DC), monocytes and macrophages, are innate immune cells that are activated by viral nucleic acids to produce proinflammatory cytokines and initiate antiviral and acquired immune responses (1, 2). HIV-1 single-stranded (ss)RNA encodes multiple uridine-rich sequences that activate plasmacytoid DC (pDC) through engagement of endosomal TLR7 and myeloid DC (mDC) and monocytes/macrophages through endosomal TLR8 (3-5). Similarly, influenza virus RNA stimulates plasmacytoid DC (pDC) through TLR7 (6), but activates mDC and monocytes/macrophages through the cytosolic helicase RIG-I (retinoic acid-inducible gene-I) (7, 8). The capacity of DC and monocytes/macrophages to respond to virus stimulation during HIV infection and its relationship to disease control and progression remain ill-defined. This is an important issue as chronic immune activation, which is associated with disease progression in HIV and pathogenic SIV infections, may be driven in part by sustained activation of innate immune cells (9-15).

Data on the responses of mononuclear phagocytes to virus-mediated activation after HIV and SIV infection are conflicting. Several earlier studies showed that blood pDC from HIV-infected patients exhibited an impairment of maturation and IFN-α production after ex vivo stimulation with TLR ligands (16-21). However, recent studies have indicated that pDC responsiveness to stimulation may actually increase following infection (22, 23), and pDC production of IFN-α during HIV infection has been implicated in CD4+ T cell apoptosis in vivo (24-27). mDC appear to retain the capacity to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines upon ex vivo exposure to TLR7/8 ligands after HIV and SIV infection, with hyperresponsiveness of these cells also being reported (22, 23, 28). Increased monocyte turnover has been associated with disease progression in SIV infected monkeys (29, 30) and monocyte and macrophage functions in HIV-infected patients may be impaired due to chronic exposure in type I IFN (31); however recent data suggest that monocytes may be hyperresponsive to TLR7/8 agonists in HIV-infected individuals (23).

Few reports have characterized the consequences of HIV infection on the functional responsiveness of different mononuclear phagocyte subsets to viral nucleic acids or the associated synthetic ligands in the same patients (22, 23), and no reports to our knowledge have evaluated the impact of infection on the function of DC and monocytes/macrophages in both blood and lymphoid tissues, a critical site of virus replication and immune activation. Such detailed comparative analyses may help determine if the mononuclear phagocyte subsets actually respond differently to HIV infection and whether these differences can be related to the capacity of the infected host to control or exacerbate disease. It also remains debatable whether antiretroviral therapy (ART) can reverse the quantitative and qualitative changes to DC and monocytes/macrophages caused by HIV infection, as some studies reveal a recovery of circulating DC and monocyte numbers while others argue no benefit after ART (17, 32-37). The impact of ART on the functional responses of mononuclear phagocytes to TLR-mediated stimulation in HIV infection has not been widely investigated and has been limited to chronically infected individuals (23).

To address this gap in our knowledge, we characterized the dynamics and function of mononuclear phagocytes in blood and lymph nodes following infection of rhesus macaques with the pathogenic biologic isolate SIVmac251, a model that results in AIDS-like disease very similar to HIV-1 infection of humans but with an accelerated time line (38). To analyze the response of mononuclear phagocytes to relevant stimuli, we identified uridine-rich ssRNA sequences within the infecting virus strain that were potent TLR7/8 agonists in naive monkeys, and used these oligonucleotides as well as influenza virus and other TLR agonists as stimuli in cells from infected monkeys. We reveal a distinct, early onset of dysfunction in both pDC and monocyte/macrophage populations that was diminished after early initiation of ART. In contrast, mDC became hyperresponsive to SIV-encoded TLR ligands and influenza virus during this same period. Moreover, we show that enhanced mDC responsiveness to viral stimuli is associated with long-term control of infection and is inversely correlated with virus load. These findings indicate that mononuclear phagocytes exhibit divergent virus-driven cytokine responses during pathogenic SIV infection and point to an unexpected relationship between increased mDC function and disease control.

Materials and Methods

Animals, viral infection, and ART

All animal experiments were done with appropriate institutional regulatory committee oversight and approval. In total, 32 adult Indian-origin rhesus macaques were used in the study. Ten animals were infected by i.v. inoculation with 100 TCID50 of SIVmac251 (generously supplied by Preston A. Marx, Tulane National Primate Research Center, Covington, LA) (39) and were followed for 36 days post infection. Viral RNA levels in plasma were determined by real-time PCR as described (40). Beginning at 7 d post infection, 5 monkeys in this cohort were administered ART, consisting of reverse transcriptase inhibitors 9-R-2-phosphonomethoxypropyl adenine (PMPA; 30 mg/kg by s.c. injection once daily for 14 d, reducing to 20 mg/kg thereafter) and Emtricitabine (FTC; 30 mg/kg by s.c. injection once daily; both drugs generously provided by Michael Miller, Gilead Science, Inc., Foster City, CA), and integrase inhibitor L-000870812 (10 mg/kg orally once daily; generously provided by Daria J. Hazuda, Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, NJ). Blood was collected longitudinally for isolation of plasma, PBMC and peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL), and inguinal or axillary lymph nodes were biopsied at 14 d post infection and at necropsy at day 36 post infection for processing into single cell suspensions as previously described (41). In order to assay for recent cell division, all 10 animals were administered BrdU (30 mg/kg by i.v. injection) on 3 consecutive days prior to lymph node biopsy as previously described (40). Five uninfected rhesus macaques received the same course of BrdU prior to lymph node biopsy and served as controls. PBMC from an additional 17 rhesus macaques with differential outcomes of SIVmac251 infection were studied at 10 wk post infection, corresponding to virus set-point (28). Nine of these animals had high virus loads at set-point (mean=1.9 × 107 RNA copies/ml plasma) and rapid progression to AIDS with a mean time to sacrifice of 32 weeks, while 8 animals with significantly lower set-point virus loads (mean=2.3 × 106 RNA copies/ml plasma, P<.01) remained free of disease for at least 56 weeks post infection (28). In some experiments archived blood and lymph node cells from additional SIV-naive rhesus macaques were analyzed to increase the number of naive samples. The number of animals used in each experiment is detailed in figure legends.

Flow cytometric analysis

The following Ab were used to stain PBMC, PBL and lymph node cell suspensions and were purchased from BD Biosciences unless otherwise noted: CD3-Pacific Blue (clone SP34-2), CD20-v450 (eBiosciences, 2H7), CD14-PE (MϕP9), CD123-PE-Cy7 (7G3), CD11c-APC (S-HCL-3), HLA-DR-APC-Cy7 (L243 or G46-6), CD163-PE (GHI/61). Dead cells were excluded by using Live/Dead viability kit (Invitrogen). Flow cytometric analysis was done as described (40) with some modifications. Absolute blood pDC, mDC, monocyte and CD4+ T cell determinations were performed using a quantitative flow cytometry-based assay incorporating TruCOUNT tubes (BD Biosciences) as previously described (42). After surface Ab labeling cells were fixed and permeabilized in BD Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer and incubated with Ab to TNF-α-PerCP-Cy5.5 (MAb11), IFN-α-FITC (225.C) and/or active caspase-3 (C92-605). In vivo BrdU incorporation was detected with the BrdU-FITC staining kit (BD Biosciences). Cells were run on a BD LSR-II flow cytometer system, collected with BD FACSDiva 6.0 software, and analyzed with FlowJo 8.8.7 (TreeStar).

Ex vivo cell stimulation with viruses and TLR agonists

Prior to staining for intracellular cytokines, cells were incubated with the following stimuli in complete media (RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 0.1 mM sodium pyruvate) for 7 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, in the presence of 1 ug/ml brefeldin A for the last 5 h, as described (40). Uridine-rich RNA oligonucleotides identified within the sequence of SIVmac251 along with the previously defined HIV-encoded TLR7/8 agonist RNA40 (5) and the corresponding adenine-substituted control oligonucleotides were synthesized and purified by desalting (Invitrogen). 10 μg of each oligonucleotide was coupled to the liposomal transfection reagent DOTAP according to the provider's protocol (Roche) prior to incubation with cells. H7N3 influenza virus (generously provided by Ted Ross, University of Pittsburgh) was used at an MOI of 5. AT-2-inactivated SIVmac239 (iSIV; generously supplied by Jeffrey D. Lifson, AIDS and Cancer Virus Program, SAIC-Frederick) was used at a capsid concentration of 200 ng/mL. The TLR7/8 agonist 3M-007 (generously provided by Mark Tomai, 3M Pharmaceuticals) was used at a final concentration of 10μM. LPS was used at a final concentration of 1μg/mL. The TLR9 stimulating CpG-274 and its corresponding control (CpG-661) were used at a final concentration of 5 μg/mL (43).

Analysis of cytokine secretion

Supernatants were collected 24 h after stimulation of PBL and lymph node cells with SIVmac251-encoded uridine-rich RNA oligonucleotide Env976 and analyzed for IFN-α using the VeriKine™ Human Interferon Alpha Multi-Subtype ELISA Kit (PBL Interferon Resource) and TNF-α using the primate TNF-α DuoSet kit (R&D Systems) as per manufacturers’ instructions.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed paired t-tests were performed to determine statistical significance regarding changes in a group observed over time and were denoted as uncapped bars on each graph. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare between treatment groups and were shown as capped bars on graphs. To determine correlations between parameters, Spearman correlation tests were performed. A P-value < 0.05 was deemed significant. All tests were performed with Graphpad Prism software.

Results

Acute SIVmac251 infection is associated with pDC and monocyte/macrophage mobilization and recruitment to lymph nodes that is attenuated with ART

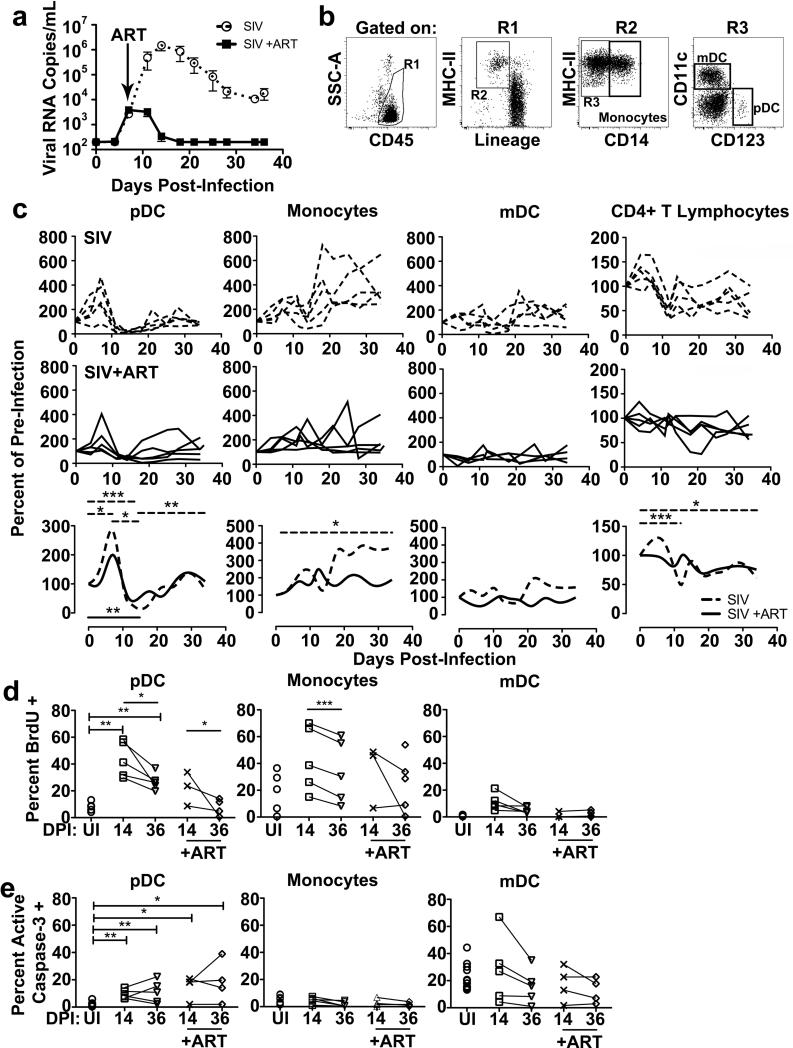

We first determined the effects of SIV infection and ART on the dynamics of mononuclear phagocytes in blood and lymph nodes of 10 acutely infected rhesus macaques that were followed longitudinally for 36 days post SIVmac251 infection. ART was initiated at 7 d post infection in 5 animals to coincide with the previously observed peak pDC response in blood (40) to determine if controlling virus replication would result in a sustained elevation of pDC numbers. As expected, plasma viral load as determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis peaked at day 14 in the 5 untreated animals but did not increase beyond day 7 and then rapidly declined to undetectable levels in the 5 ART-treated macaques (Figure 1A). We next used flow cytometry to identify different cell subsets and determine their kinetics over the 36-day course of the experiment. We used a standard analysis to identify and quantify mDC (HLA-DR+ CD3- CD14- CD20- CD123- CD11c+), pDC (HLA-DR+ CD3- CD14- CD20-CD11c- CD123+) and monocytes (HLA-DR+ CD3- CD20- CD14+/low) in blood (42, 44). Preliminary studies confirmed that CD14+/low expression encompassed all monocyte subsets including cells expressing the monocyte/macrophage-lineage restricted scavenger receptor CD163, consistent with other studies (data not shown)(44, 45). To account for the inherent variation in DC number in blood of uninfected animals (42) and to highlight the changes over time in response to SIV infection, we normalized cell counts to pre-infection levels in all animals. In untreated animals blood pDC transiently increased at day 7 and then declined at day 14, as previously described (40), prior to regaining pre-infection numbers at day 36, but this was only minimally impacted by ART (Figure 1C). While not statistically significant, the numbers of blood mDC fluctuated in untreated animals with a decline at day 14 post infection, consistent with previous reports [(28) and data not shown)], and this variability was not as apparent in ART-treated animals. Similar and more marked decreases in CD4+ T cells at day 14 post infection were seen in untreated macaques, and this loss did not occur in monkeys treated with ART. Conversely, the monocyte population underwent a continual, significant increase over time in the untreated group, which was not observed in ART treated animals (Figure 1C). We then assayed for recent division of pDC, mDC and monocytes by measuring BrdU incorporation. After SIV infection a significantly greater proportion of blood pDC were BrdU+ consistent with mobilization of recently produced cells from bone marrow, where pDC divide and leave as terminally differentiated cells (Figure 1D)(40). Blood pDC also had increased expression of active caspase-3 following SIV infection, reflecting apoptosis (Figure 1E). Mobilization of pDC was less pronounced in the presence of ART, with the percentage of BrdU+ pDC at day 36 being indistinguishable from uninfected animals (Figures 1D, E). Monocytes had a modest although statistically significant decrease in BrdU incorporation from day 14 to 36 in untreated animals, but there was no evidence of monocyte apoptosis in either group, and mDC did not have significant changes in recently divided cells or apoptotic cells as a result of infection or treatment (Figure 1D, E).

Figure 1. ART inhibits pDC and monocyte mobilization in the blood of SIV-infected rhesus macaques.

(A) Plasma viral load measured from untreated (open circles, n=5) and ART-treated (closed boxes, n=5) SIVmac251-infected macaques. ART consisted of reverse transcriptase inhibitors PMPA and FTC and integrase inhibitor L-000870812 and was begun at day 7 post infection (arrow). (B) Gating strategy to identify blood pDC (HLA-DR+ CD3- CD14- CD20- CD11c- CD123+), monocyte (HLA-DR+ CD3-CD20- CD14+/low), and mDC (HLA-DR+ CD3- CD14- CD20-CD123- CD11c+) populations by flow cytometry. (C) Absolute counts of pDC, monocytes, mDC and CD4+ T cells in blood over time for untreated (n=5, top row) and ART-treated (n=5, middle row) SIV-infected macaques showing the percent change in cell counts relative to preinfection levels for individual animals. Data are also presented as smoothed spline graphs of the average percent change in cell count for each group (bottom row). (D) Percent of blood pDC, monocytes and mDC that have incorporated BrdU in either uninfected (UI, n=5), or macaques at day 14 (untreated n=5; ART treated n=3) and day 36 post infection (untreated n=5; ART treated n=5). (E) Percent of blood pDC, monocytes and mDC that express active caspase-3 in either uninfected (n=11), or SIV-infected macaques at day 14 (untreated n=5; ART treated n=4), or day 36 post infection (untreated n=5; ART treated n=4). Uncapped bars signify differences within groups; capped bars signify differences between groups. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001. DPI=days post infection.

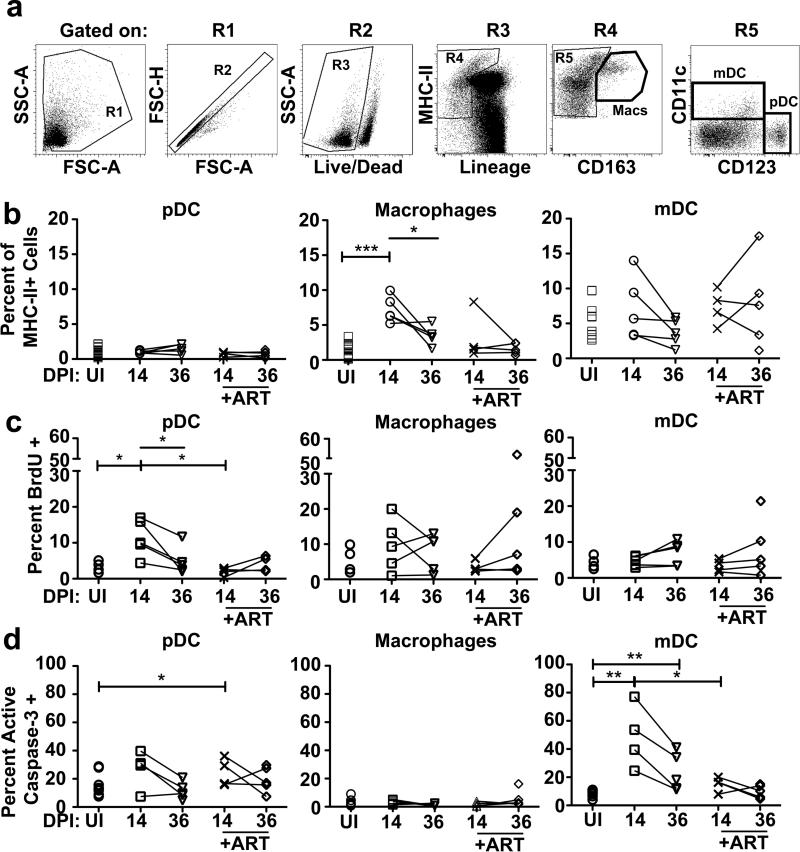

In order to explore important sites of cellular recruitment and immune activation, we next examined the effects of SIV infection on mononuclear phagocytic cells found in peripheral lymph nodes. We identified pDC (HLA-DR+ CD3- CD14- CD20- CD11c- CD123+), macrophages (HLA-DR+ CD3- CD20- CD163+), and mDC (HLA-DR+ CD3-CD14- CD20- CD123- CD11c+) (Figure 2A)(40) and quantified each as a percent of MHC class II+ cells. There was no change in the percentage of pDC in lymph nodes at day 14 and 36 post infection, regardless of ART, although pDC within lymph nodes of untreated animals at day 14 were recently recruited, based on significant increases in the proportion of BrdU+ cells. Strikingly, ART treatment inhibited this pDC influx after only 7 d of therapy, associated with a modest increase in pDC apoptosis relative to uninfected animals (Figure 2B-D). The proportion of macrophages in lymph nodes rose significantly at 14 d post infection, which was absent in ART treated samples and was not associated with any detectable change in cell division or apoptosis (Figure 2B-D). The proportion of mDC in lymph nodes did not change as a function of infection or ART. Consistent with previous reports (46), lymph node mDC did have increased apoptosis beginning at 14 d post infection, which was not observed in ART-treated animals (Figure 2B-D).

Figure 2. Mononuclear cell recruitment and turnover in lymph nodes in SIV infected rhesus macaques is limited by ART.

(A) Gating strategy to identify pDC (HLA-DR+ CD3- CD14- CD20- CD11c- CD123+), macrophage (HLA-DR+ CD3- CD20- CD163+), and mDC (HLA-DR+ CD3- CD14- CD20-CD123- CD11c+) populations in lymph nodes by flow cytometry. The Lineage– MHC class II+ gate (R4) includes MHC class IIbright cells with high autofluorescence (41). (B) pDC, macrophages, and mDC as a percent of the Lineage– MHC class II+ cells in lymph nodes in uninfected macaques (UI, n≥14) or macaques at day 14 (untreated n=5; ART treated n=4), and day 36 (untreated n=5; ART treated n=5) post infection. (C) Percent of lymph node pDC, macrophages and mDC that have incorporated BrdU in either uninfected (n=5), or SIV-infected macaques at day 14 (untreated n=5; ART treated n=4), or day 36 post infection (untreated n=5; ART treated n=5). (D) Percent of lymph node pDC, macrophages and mDC that express active caspase-3 in either uninfected (n=10), or SIV-infected macaques at day 14 (untreated n=4; ART treated n=4), or day 36 post infection (untreated n=5; ART treated n=5). Uncapped bars signify differences within groups; capped bars signify differences between groups. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001. DPI=days post infection.

SIVmac251 encodes ssRNA sequences that stimulate pro-inflammatory cytokine production by SIV-naive rhesus macaque mononuclear phagocytes

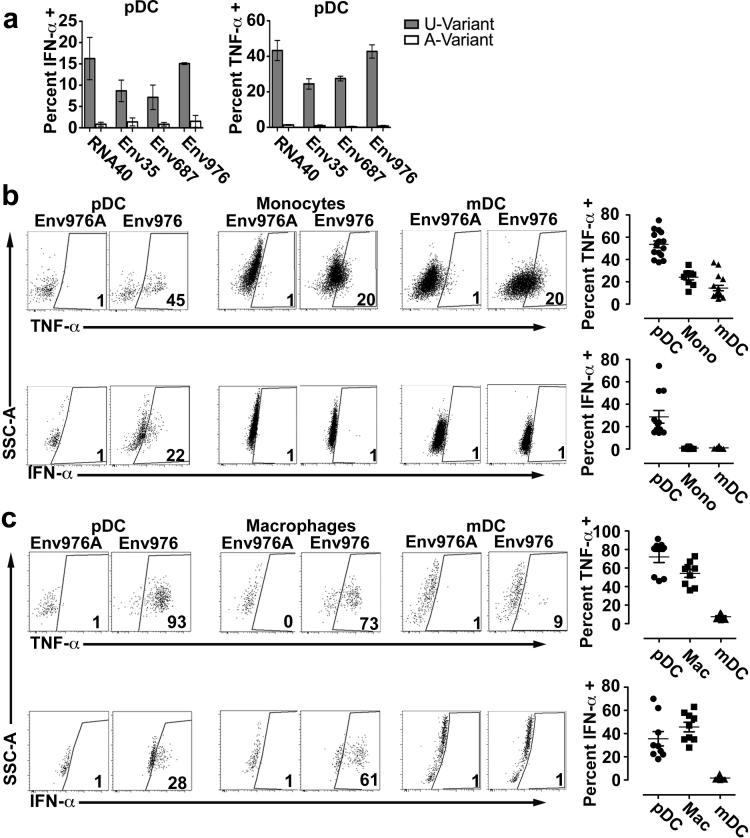

To determine the impact of SIVmac251 infection on DC and monocyte/macrophage function, we first tested the capacity of cells from uninfected animals to respond to biologically relevant TLR stimuli. To do this we investigated the potential for ssRNA from SIVmac251, the infecting virus strain, to encode uridine-rich sequences that activate cells via TLR7 and TLR8, as has been reported for HIV-1 (4, 5). We identified three 20-base long nucleotide sequences within the env coding region of SIVmac251 that contained uridine bases at a frequency of 50% or greater and were therefore likely candidates as TLR7 and TLR8 ligands. We synthesized the respective ssRNA oligonucleotides, named based on the position of the 5’ base within the corresponding viral open reading frame (Env35: 5’-UCUUGCUUUUAAGUGUCUAU; Env687: 5’-UAUUAGAUUUAGGUAUUGUG; and Env976: 5’-AUUAUGUCUGGAUUGGUUUU) along with the corresponding control oligonucleotide containing U to A substitutions (termed Env35A, Env687A and Env976A). To determine the capacity for these ssRNA oligonucleotides to stimulate mononuclear phagocytes we first analyzed the response of blood pDC. PBMC from SIV-naive macaques were incubated with RNA40, Env35, Env687 and Env976 or the respective control oligonucleotides coupled to DOTAP and then cytokine production was measured by flow cytometry using our established Ab panel to identify pDC. Blood pDC responded to RNA40, the previously defined HIV-1-derived TLR7 ligand (5), but did not respond to the U to A variant RNA41. Similarly, pDC readily produced IFN-α and TNF-α when stimulated with all three SIVmac251-derived uridine-rich oligonucleotides but not control oligonucleotides (Figure 3A). Using the same method and previously defined Ab panels, we next tested the capacity of the most potent SIVmac251-derived oligonucleotide Env976 to induce cytokine production from each mononuclear phagocytic cell subset in blood and lymph node of a group of SIV-naive animals. SIVmac251 Env976 was a potent stimulator of pDC to produce proinflammatory cytokines, especially in the lymph node, where on average 75% of pDC produced TNF-α and 35% produced IFN-α, although there was considerable range in response between animals (Figure 3B, C). Env976 exposure did not induce monocytes to produce IFN-α but did induce significant production of TNF-α. In contrast, on average 50% to 55% of macrophages isolated from SIV-naive lymph nodes produced IFN-α and TNF-α in response to stimulation with Env976 (Figure 3B, C). mDC from blood and lymph node of naive animals produced TNF-α in response to Env976 stimulation but lacked production of IFN-α (Figure 3B, C).

Figure 3. SIVmac251 ssRNA encodes uridine-rich TLR7/8 agonists that induce rhesus mononuclear phagocytes to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines.

(A) Percent of SIV-naive blood pDC producing IFN-α and TNF-α after stimulation with uridine-rich oligonucleotides from SIVmac251 env region and RNA40 from HIV-1 (gray bars) or adenine-substituted control oligonucleotides (white bars). Shown are means ± SEM for 3 animals. (B, C) IFN-α and TNF-α production by SIV-naive pDC, monocytes/macrophages and mDC in blood (B) (n≥9) and lymph node (C) (n=9) showing representative dot plots (left) and the percent of cytokine-producing cells (right). Blood and lymph node cell populations are defined as in Figure 1B and 2A, respectively. Gates are set on the response to Env976A for each cell type. Numbers represent percent of cells producing the respective cytokine.

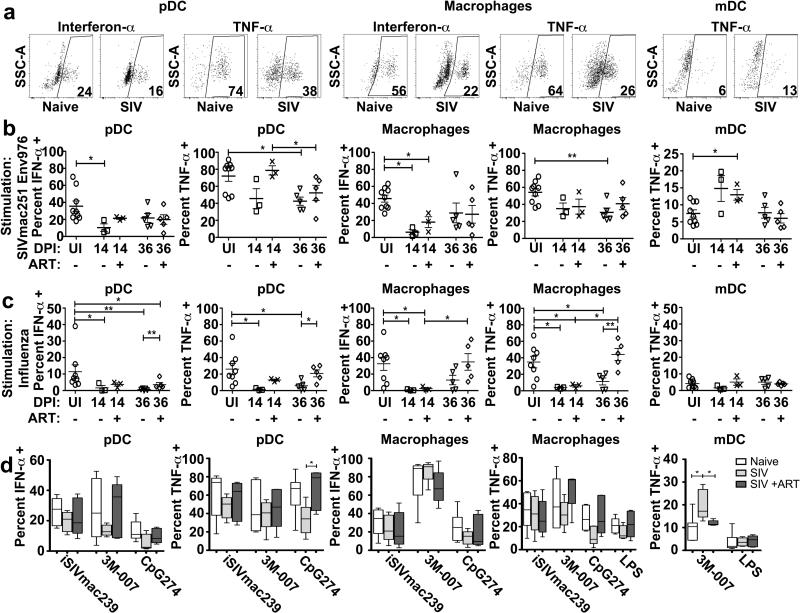

pDC and monocytes/macrophages rapidly lose responsiveness to SIV-encoded TLR ligands in acute SIV infection while mDC become hyperresponsive

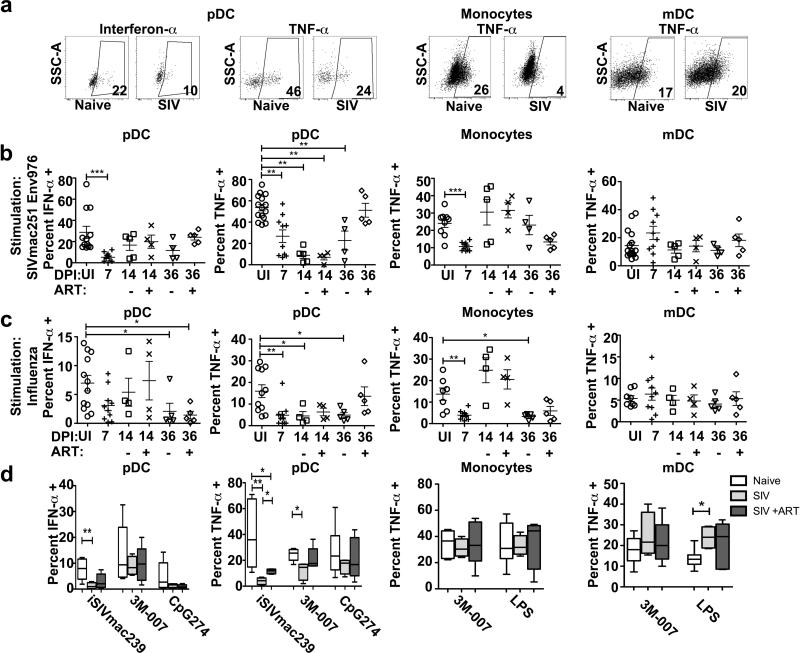

To determine the impact of acute SIVmac251 infection and ART on the function of mononuclear phagocytes, we isolated PBL at day 7 when ART was initiated and again at days 14 and 36 and stimulated unseparated cells with Env976 oligonucleotide, analyzing production of intracellular cytokines by flow cytometry (Figure 4A). In these analyses and the subsequent experiments with lymph node cells we focused on pDC and macrophage production of IFN-α and TNF-α and mDC and monocyte production of TNF-α based on the findings from SIV-naive animals. Acute SIVmac251 infection substantially suppressed pDC responses to SIV-encoded TLR ligand, reducing the proportion of blood pDC secreting IFN-α and TNF-α within 7 days of infection, an effect that continued through day 14 to day 36 post infection and was reversed by the 4-wk course of ART (Figure 4B). The suppression of functional pDC responses as a result of acute SIV infection was also noted with other stimuli, including influenza virus, iSIV and the synthetic TLR7/8 agonist 3M-007 (Figure 4C, D). Monocyte production of TNF-α in response to Env976 was transiently suppressed at day 7 post infection, while monocyte responsiveness to influenza virus was suppressed at days 7 and 36 post infection with a transient recovery at day 14 (Figure 4 B, C). SIVmac251 infection was associated with a modest but not signficant increase in the capacity of mDC to produce TNF-α in response to Env976 stimulation at day 7 post infection, with a wide variation between animals (Figure 4B). However, significant enhancement of TNF-α production by mDC was noted at day 36 post infection following stimulation with LPS, a TLR4 ligand (Figure 4D). Differences in the proportion of cells expressing the respective cytokines were generally not associated with any change in the relative amount of cytokine being made as measured by mean fluorescence intensity, with the exception of TNF-α production by Env976-stimulated blood pDC, which was reduced 3.5 fold in SIV-infected (day 7, n=9) relative to uninfected macaques (n=10, p=0.03) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Blood pDC and monocytes from acutely SIV-infected rhesus macaques become unresponsive to TLR agonists.

(A) Representative dot plots showing cytokine production from blood pDC, monocytes and mDC from SIV-naïve and SIV-infected macaques after stimulation with SIVmac251 Env976. Cell populations are defined as in Figure 1B. (B) Percent of each cell population from uninfected macaques (UI, n≥9) and macaques at day 7 (n=10), day 14 (untreated n=5; ART treated n=4) and day 36 (untreated n=4; ART treated n=5) post SIVmac251 infection after stimulation with SIVmac251 Env976. (C) Percent of each cell population from uninfected macaques (n≥7) and macaques at day 7 (n=10), day 14 (untreated n=4; ART treated n=4) and day 36 (untreated n=5; ART treated n=5) post SIVmac251 infection after stimulation with influenza virus. (D) Percent of each cell population from uninfected macaques (white bars, n≥5) and macaques at 36 days after SIVmac251 infection (untreated, light gray bars, n=5; ART treated, dark gray bars, n=5) producing the indicated cytokines after stimulation with iSIV, 3M-007, CpG274 and LPS. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001.

To determine if acute SIVmac251 infection also impacted the functional responses of mononuclear phagocytes in lymph nodes, we stimulated peripheral lymph node cells isolated at 14 and 36 days post infection, with and without ART, with Env976, influenza virus and other TLR stimuli and analyzed intracellular cytokine production of the individual subsets by flow cytometry (Figure 5A). As in blood, acute SIV infection suppressed the capacity of lymph node pDC to produce proinflammatory cytokines in response to stimulation with the SIV-encoded TLR agonist Env976 as well as influenza virus, and ART treatment largely restored this responsiveness (Figure 5B, C). Lymph node pDC production of TNF-α in response to stimulation with the TLR9 agonist CpG274 was also suppressed at 36 days post infection and restored by ART treatment (Figure 5D). The impact of SIVmac251 infection on lymph node macrophages was striking, with near complete loss of the capacity of macrophages to produce IFN-α in response to Env976 and both IFN-α and TNF-α in response to influenza virus at 14 days post infection. While macrophage responses to Env976 remained suppressed even with ART the capacity of macrophages to produce IFN-α and TNF-α in response to influenza virus stimulation was completely restored with 4 weeks of ART (Figure 5B, C). In contrast, acute SIVmac251 infection resulted in increased responsiveness of lymph node mDC to stimulation with Env976 and 3M-007, but not influenza virus. Hyperresponsiveness to 3M-007 was not observed in monkeys receiving ART treatment (Figure 5A-C). Changes in the relative amount of cytokine produced by the different cell subsets in lymph nodes based on mean fluorescence intensity as a consequence of infection were not detected (data not shown and Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Acute SIVmac251 infection induces hyporesponsiveness of lymph node pDC and macrophages and hyperresponsiveness of lymph node mDC.

(A) Representative dot plots showing cytokine production from lymph node pDC, macrophages and mDC from SIV-naïve and SIV-infected macaques after stimulation with SIVmac251 Env976. Cell populations are defined as in Figure 2A. (B) Percent of each cell population from uninfected macaques (UI, n=9) and macaques at day 14 (untreated n=3; ART treated n=3) and day 36 (untreated n=5; ART treated n=5) post SIVmac251 infection producing the indicated cytokines after stimulation with SIVmac251-encoded Env976. (C) Percent of each cell population from uninfected macaques (n=8) and macaques at day 14 (untreated n=3; ART treated n=3) and day 36 (untreated n=5; ART treated n=5) post SIVmac251 infection producing the indicated cytokines after stimulation with influenza virus. (D) Percent of each cell population from uninfected macaques (white bars, n≥5) and macaques at 36 days after SIVmac251 infection (untreated, light gray bars, n=5; ART treated, dark gray bars, n=5) producing the indicated cytokines after stimulation with iSIV, 3M-007, CpG274 and LPS. * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01.

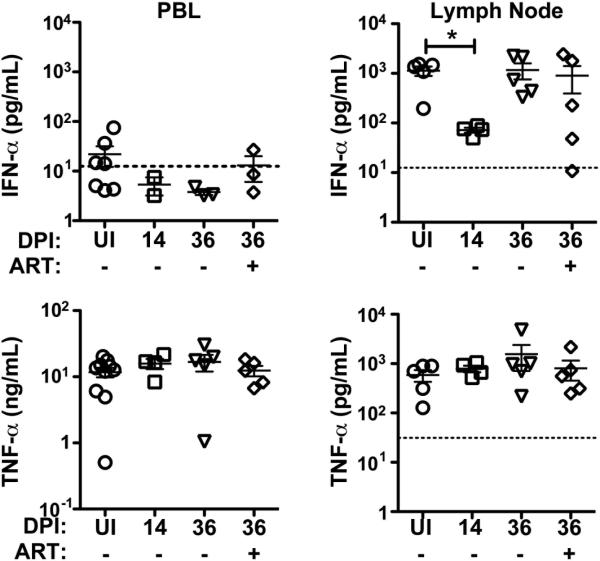

Transient suppression of IFN-α but not TNF-α secretion from unseparated lymph node cells following SIV infection

To address how these functional differences in individual mononuclear phagocyte subsets as a result of SIV infection may impact the overall response of the host, we stimulated unseparated PBL and lymph node cells with Env976 oligonucleotide and analyzed production of IFN-α and TNF-α in culture supernatants. To provide a valid comparison we analyzed both blood and lymph node prior to infection and at 14 and 36 days post infection, with and without ART at day 36. Production of IFN-α from stimulated PBL averaged only 30 pg/ml from uninfected animals before dropping below the level of detection of 12.5 pg/ml following SIV infection (Figure 6). This low level of IFN-α from whole PBL preparations likely reflects the very low frequency of IFN-α producing pDC in blood, even in the uninfected state. In contrast, IFN-α was produced at an average of more than 1,000 pg/ml from Env976-stimulated lymph node cells from uninfected animals and this dropped 12-fold in acute infection, consistent with the marked suppression of pDC and macrophage production of IFN-α seen by flow cytometry. This suppressed IFN-α secretion was transient, returning to normal levels by day 36 post infection regardless of ART (Figure 6). In uninfected animals the production of TNF-α from Env976-stimulated PBL was 10-fold greater than from lymph node cells but this secretion was not significantly altered by SIV infection (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Marked but transient suppression of IFN-α secretion from stimulated lymph node cells in acute SIV infection of rhesus macaques.

Concentration of IFN-α (top panel) and TNF-α (bottom panel) in supernatants from peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL, left column) and lymph node cells (right column) stimulated with SIVmac251 Env976 as determined by ELISA. Samples were taken from uninfected macaques (UI, n≥5) and macaques at day 14 (untreated n≥4), and day 36 (untreated n=5; ART n=5) post SIVmac251 infection. The threshold of detection for each assay is marked by dashed lines (obscured by x-axis in PBL TNF-α graph). * P < 0.05.

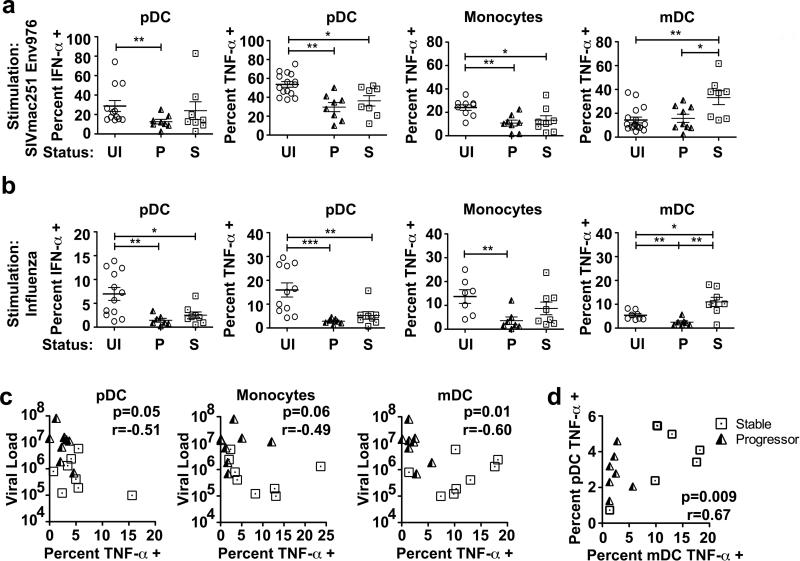

Divergent responsiveness of pDC, monocytes and mDC to virus stimulation correlates with disease outcome in SIVmac251 infected-macaques

The preceding data indicating that mononuclear phagocytes have functionally divergent responses during acute SIVmac251 infection raise the issue of whether these differences are maintained throughout infection and if so whether they correlate with disease outcome. To address this possibility, we evaluated the responses of blood mononuclear phagocytes from two groups of rhesus macaques that were previously characterized as having divergent clinical outcomes following SIVmac251 infection, with 9 animals progressing rapidly to AIDS with a mean time to sacrifice of 32 weeks and 8 animals remaining disease-free for at least 56 weeks (28). We stimulated mixed PBMC cultures from these animals taken at 10 weeks post infection, at the time of virus set-point and prior to manifestation of disease in the progressor animals, with either SIVmac251 Env976 or influenza virus and evaluated the cytokine production of individual mononuclear phagocyte subsets by flow cytometry. Blood pDC taken from monkeys from both groups at week 10 post infection had generally suppressed IFN-α and TNF-α production in response to both Env976 and influenza virus stimulation (Figure 7A, B). Similarly, blood monocytes from both stable and progressor animals had suppressed TNF-α production in response to Env976 and influenza virus stimulation (Figure 7A, B). However, blood mDC taken from stable SIV-infected animals at 10 weeks post infection were hyperresponsive to stimulation with virus-encoded Env976, with twice as many cells producing TNF-α relative to both uninfected macaques and macaques with progressive infection (Figure 7A). This effect was more striking in response to influenza virus stimulation, as mDC from the progressive and stable infection groups had significantly suppressed and enhanced TNF-α production, respectively, relative to uninfected animals. When compared to animals with progressive infection, mDC from animals with stable infection had 4-fold greater production of TNF-α at 10 weeks post infection (Figure 7B). The capacity for blood mDC taken at week 10 post SIVmac251 infection to make TNF-α in response to influenza virus exposure was strongly inversely correlated with set-point virus load, and a similar but weaker relationship was seen in the pDC and monocyte populations (Figure 7C). In addition, there was a strong positive correlation between mDC and pDC production of TNF-α in response to influenza virus stimulation in the same animals (Figure 7D). Together, these data indicate that during chronic SIVmac251 infection the capacity for mononuclear phagocytes to respond to virus-encoded TLR ligands is negatively impacted by virus load, and in the case of mDC, increases in TLR responsiveness are associated with long-term control of virus infection.

Figure 7. Divergent functional responses of blood mononuclear phagocytes from SIVmac251-infected rhesus macaques are associated with disease control and progression.

(A) Percent of blood pDC, monocytes and mDC from uninfected macaques (UI, n≥9), and macaques at 10 wk post SIVmac251 infection that progressed rapidly to AIDS (P, n≥8) or had long-term stable infection (S, n=8), producing the indicated cytokines in response to SIVmac251-encoded Env976. (B) Percent of blood pDC, monocytes and mDC from uninfected macaques (n≥7), and macaques at 10 wk post SIVmac251 infection that progressed rapidly to AIDS (P, n=7) or had long-term stable infection (S, n=8), producing the indicated cytokines in response to influenza virus stimulation. Cell populations are defined as in Figure 1B. * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01. (C) Correlation between the percent of pDC, monocytes and mDC producing TNF-α in response to influenza virus stimulation and the viral load at set-point for animals with stable (squares) and progressive (triangles) SIVmac251 infection. (D) Correlation between the percent of mDC and pDC that produce TNF-α in response to influenza virus stimulation at wk 10 post SIVmac251 infection.

Discussion

In this study we assessed the impact of pathogenic SIVmac251 infection in rhesus macaques on the dynamics and function of mononuclear phagocytes in blood and lymphoid tissues. Our findings confirm that the kinetics of the pDC response to acute SIV infection is highly dynamic (40, 47-49). The marked increase in the proportion of pDC in both blood and lymph node incorporating BrdU in acute infection reflects mobilization into blood and recruitment to tissues, as pDC division and hence BrdU incorporation is limited to the bone marrow (40). It would appear that in acute infection pDC mobilization into blood cannot keep pace with pDC loss through apoptosis and tissue recruitment, as the percentage of circulating pDC at day 14 plummeted to <10% of preinfection levels, particularly in the absence of ART. The mechanism of pDC apoptosis may be related to the rapid increase in IFN-α production in blood occurring at around day 11 (11) as IFN-α itself drives pDC apoptosis and regulates pDC numbers in vivo (50). Our findings indicate that monocytes also are mobilized into blood and recruited into lymph node early in SIV infection, as has been shown for rhesus macaques with established SIV infection (29), and reveal that this monocyte response is prevented by ART.

To appropriately define the functional responses of DC and monocytes/macrophages during SIV infection we first identified uridine-rich ssRNA sequences encoded by the infecting virus that were capable of eliciting proinflammatory responses in cells isolated from uninfected animals. Similar to HIV-1 (4, 5), we defined at least 3 regions of the SIVmac251 genome with high uridine content, all within the env coding region, that were potent activators of mononuclear phagocytes. A surprising finding with these SIV-encoded TLR ligands was that SIV-naive lymph node macrophages were in fact more potent producers of IFN-α than pDC, a result that also extended to stimulation with influenza virus and 3M-007.

The rapid decrease in the functional responses of blood pDC from SIV-infected rhesus macaques following virus stimulation are consistent with other reports in SIVmac251-infected cynomolgus macaques and in humans with untreated primary HIV infection (48, 51). We also find that pDC and macrophages from lymph nodes in acute infection have markedly reduced production of IFN-α and TNF-α following stimulation with SIV-encoded TLR ligand and influenza virus, despite having a robust cytokine response when stimulated in the naive state. This is consistent with findings in the literature, as while large amounts of IFN-α are produced by resident pDC in lymph nodes at around 14 days post SIVmac251 infection (10), this production appears to be transient, declining within days of the peak response, as it does in blood (11, 13). The suppression in pDC and macrophage responsiveness was reflected in a 12-fold reduction in IFN-α secretion from stimulated lymph node cells, but this functional blockade in IFN-α secretion was reversible. These findings suggest that factors other than pDC and macrophage dysfunction may contribute to the post-acute decline in IFN-α. Interestingly, TNF-α secretion from stimulated unseparated lymph node cells was not significantly impacted by SIV infection. This likely reflects the complexity of unseparated lymph node cells, as the decrease in TNF-α production from pDC and macrophages would be balanced by the increased functional capacity of mDC.

Our data conflict with two recent studies showing that blood pDC (22) and monocytes (23) from individuals with primary HIV infection are in fact hyperresponsive in their production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines following stimulation with synthetic TLR7/8 agonists and to a lesser extent iHIV. The choice of stimulus used to define mononuclear phagocyte function during infection may account for part of this discrepancy. Indeed, in our current study both blood and lymph node pDC and monocyte/macrophages responses to the synthetic TLR7/8 ligand 3M-007 were largely normal in monkeys with acute SIV infection, whereas responses to SIVmac251 ssRNA uridine-rich sequences and influenza virus were uniformly suppressed. It is possible that synthetic TLR agonists are so effective at activating cells that they obscure potential defects in mononuclear phagocyte function as a consequence of HIV/SIV infection.

In contrast to pDC and monocytes/macrophages, we observed that lymph node mDC from macaques with acute SIVmac251 infection had increased production of TNF-α in response to stimulation with SIVmac251 ssRNA-encoded uridine-rich sequences, consistent with previous reports in both SIV-infected monkeys and HIV-infected humans (22, 23, 28). Blood mDC were more responsive to LPS stimulation after SIV infection, suggesting that these cells could produce TNF-α in vivo in response to high plasma levels of LPS that are thought to result from microbial translocation from the gut (52). The increased responsiveness of blood mDC to TLR7/8 agonists during chronic HIV infection has given rise to the hypothesis that mDC hyperfunctionality may contribute to ongoing T cell immune activation and AIDS (22, 23). However, our data in SIVmac251-infected macaques indicate that increased mDC function may be a positive characteristic, as mDC hyperresponsiveness at virus set-point in animals with long-term control of infection discriminated them from monkeys that subsequently developed disease. It is interesting to note that accumulation of semimature mDC in lymph nodes has been noted in individuals with chronic HIV infection, including asymptomatic individuals, and these cells have an increased capacity to stimulate regulatory T cells in vitro (53, 54). In addition, tissue mDC from chronically SIV-infected rhesus macaques have an increased capacity to induce regulatory T cells in vitro than mDC from naive animals (55). Whether the immunostimulatory capacity of mDC is enhanced in SIV or HIV infection and how this might relate to control of disease remains to be explored.

Initiation of ART at 1-wk post SIVmac251 infection had marked effects on both the dynamics and function of mononuclear phagocytes and is consistent with a rapid reversal of the inflammatory response, particularly in lymphoid tissues (56, 57). The findings highlight the role of inflammation in mobilization of mononuclear phagocytes into blood and their recruitment and death within lymphoid tissues (10, 13, 28, 40, 48, 49). The suppressed cytokine responses of pDC and monocytes/macrophages in blood and lymph node as a result of SIV infection were also largely reversed with ART. It is conceivable that direct infection of pDC and monocytes/macrophages in vivo impacts their functional responses and that reduction of infection restores function. In the case of pDC we believe this is unlikely, as only around 4% of pDC harbor virus infection at peak virus load (40). The potential for macrophages to be infected and thus impacted by viral RNA increases with progressive infection and CD4+ T cell decline (58, 59), although whether sufficient macrophages contain viral RNA in acute infection to impact their function is not known.

Resolution of inflammatory responses after the acute phase is one major factor that distinguishes nonpathogenic SIV infection of African nonhuman primate hosts such as the sooty mangabey and African green monkey from pathogenic SIV infection of Asian macaques (60). The persistent immune activation in SIV-infected macaques is associated with sustained high level expression of IFN-stimulated genes in lymphoid tissues (9, 11, 12), and together with data in the human has implicated IFN-α-producing cells such as pDC in the pathogenesis of immune activation (15, 61). Our data reveal that rhesus macaques with chronic SIV infection have significant impairment in the capacity of pDC to produce proinflammatory cytokines in response to virus stimulation, which is not consistent with a pathologic role for pDC in SIV infection. Moreover, the precise role of IFN-α in driving immune activation in HIV and pathogenic SIV infection remains unclear. Exogenous IFN-α given to chronically SIV-infected sooty mangabeys increases IFN-stimulated gene expression but does not increase chronic immune activation. Rather, exogenous IFN-α has predominantly an antiviral function driving down virus load (62), as has been shown in HIV-infected humans (63, 64). It is therefore possible that high level expression of IFN-stimulated genes in pathogenic SIV infection may be a marker of immune activation rather than an essential component of the process.

We were not able to isolate and analyze mucosal pDC in our study, but recent studies indicate that pDC are recruited to gut mucosa in SIV-infected macaques (14, 65), as in other viral infections that target mucosal tissues (66-68). pDC in the gut mucosa of SIV-infected macaques are capable of producing proinflammatory cytokines when stimulated with iSIV, although to a significantly lesser extent than pDC from mesenteric lymph node (14). Production of IFN-α by mucosal pDC following TLR7/8 stimulation is also suppressed following SIV infection (65). The potential contribution of pDC recruited into the mucosa to inflammation and immune activation during SIV infection is likely to be complex and deserves further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the contributions of the members of the Barratt-Boyes laboratory and the Center for Vaccine Research at the University of Pittsburgh. We are grateful for the generous reagent contributions as mentioned in the Materials and Methods.

This research was supported by grants T32CA082084 from the National Cancer Institute and R01AI071777 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Reagents provided by the AIDS and Cancer Virus Program, SAIC-Frederick, were supported by contract HHSN261200800001E from the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pichlmair A, Reis e Sousa C. Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity. 2007;27:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beignon AS, McKenna K, Skoberne M, Manches O, DaSilva I, Kavanagh DG, Larsson M, Gorelick RJ, Lifson JD, Bhardwaj N. Endocytosis of HIV-1 activates plasmacytoid dendritic cells via Toll-like receptor-viral RNA interactions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3265–3275. doi: 10.1172/JCI26032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meier A, Alter G, Frahm N, Sidhu H, Li B, Bagchi A, Teigen N, Streeck H, Stellbrink HJ, Hellman J, van Lunzen J, Altfeld M. MyD88-dependent immune activation mediated by human immunodeficiency virus type 1-encoded Toll-like receptor ligands. J Virol. 2007;81:8180–8191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00421-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampenberger F, Kirschning C, Akira S, Lipford G, Wagner H, Bauer S. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato H, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Uematsu S, Matsui K, Tsujimura T, Takeda K, Fujita T, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Cell type-specific involvement of RIG-I in antiviral response. Immunity. 2005;23:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlee M, Roth A, Hornung V, Hagmann CA, Wimmenauer V, Barchet W, Coch C, Janke M, Mihailovic A, Wardle G, Juranek S, Kato H, Kawai T, Poeck H, Fitzgerald KA, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Tuschl T, Latz E, Ludwig J, Hartmann G. Recognition of 5' triphosphate by RIG-I helicase requires short blunt double-stranded RNA as contained in panhandle of negative-strand virus. Immunity. 2009;31:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosinger SE, Li Q, Gordon SN, Klatt NR, Duan L, Xu L, Francella N, Sidahmed A, Smith AJ, Cramer EM, Zeng M, Masopust D, Carlis JV, Ran L, Vanderford TH, Paiardini M, Isett RB, Baldwin DA, Else JG, Staprans SI, Silvestri G, Haase AT, Kelvin DJ. Global genomic analysis reveals rapid control of a robust innate response in SIV-infected sooty mangabeys. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3556–3572. doi: 10.1172/JCI40115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris LD, Tabb B, Sodora DL, Paiardini M, Klatt NR, Douek DC, Silvestri G, Muller-Trutwin M, Vasile-Pandrea I, Apetrei C, Hirsch V, Lifson J, Brenchley JM, Estes JD. Downregulation of robust acute type I interferon responses distinguishes nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of natural hosts from pathogenic SIV infection of rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2010;84:7886–7891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02612-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacquelin B, Mayau V, Targat B, Liovat AS, Kunkel D, Petitjean G, Dillies MA, Roques P, Butor C, Silvestri G, Giavedoni LD, Lebon P, Barre-Sinoussi F, Benecke A, Muller-Trutwin MC. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of African green monkeys induces a strong but rapidly controlled type I IFN response. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3544–3555. doi: 10.1172/JCI40093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lederer S, Favre D, Walters KA, Proll S, Kanwar B, Kasakow Z, Baskin CR, Palermo R, McCune JM, Katze MG. Transcriptional profiling in pathogenic and non-pathogenic SIV infections reveals significant distinctions in kinetics and tissue compartmentalization. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000296. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campillo-Gimenez L, Laforge M, Fay M, Brussel A, Cumont MC, Monceaux V, Diop O, Levy Y, Hurtrel B, Zaunders J, Corbeil J, Elbim C, Estaquier J. Non pathogenesis of SIV infection is associated with reduced inflammation and recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to lymph nodes, not to lack of an interferon type I response, during the acute phase. J Virol. 2010;84:1838–1846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01496-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwa S, Kannanganat S, Nigam P, Siddiqui M, Shetty RD, Armstrong W, Ansari A, Bosinger SE, Silvestri G, Amara RR. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are recruited to the colorectum and contribute to immune activation during pathogenic SIV infection in rhesus macaques. Blood. 2011;118:2763–2773. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boasso A, Shearer GM. Chronic innate immune activation as a cause of HIV-1 immunopathogenesis. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinson JA, Roman-Gonzalez A, Tenorio AR, Montoya CJ, Gichinga CN, Rugeles MT, Tomai M, Krieg AM, Ghanekar S, Baum LL, Landay AL. Dendritic cells from HIV-1 infected individuals are less responsive to toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands. Cell Immunol. 2007;250:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chehimi J, Campbell DE, Azzoni L, Bacheller D, Papasavvas E, Jerandi G, Mounzer K, Kostman J, Trinchieri G, Montaner LJ. Persistent decreases in blood plasmacytoid dendritic cell number and function despite effective highly active antiretroviral therapy and increased blood myeloid dendritic cells in HIV-infected individuals. J Immunol. 2002;168:4796–4801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donaghy H, Gazzard B, Gotch F, Patterson S. Dysfunction and infection of freshly isolated blood myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in patients infected with HIV-1. Blood. 2003;101:4505–4511. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anthony DD, Yonkers NL, Post AB, Asaad R, Heinzel FP, Lederman MM, Lehmann PV, Valdez H. Selective impairments in dendritic cell-associated function distinguish hepatitis C virus and HIV infection. J Immunol. 2004;172:4907–4916. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamga I, Kahi S, Develioglu L, Lichtner M, Maranon C, Deveau C, Meyer L, Goujard C, Lebon P, Sinet M, Hosmalin A. Type I interferon production is profoundly and transiently impaired in primary HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:303–310. doi: 10.1086/430931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siegal FP, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Holland BK, Shodell M. Interferon-alpha generation and immune reconstitution during antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS. 2001;15:1603–1612. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabado RL, O'Brien M, Subedi A, Qin L, Hu N, Taylor E, Dibben O, Stacey A, Fellay J, Shianna KV, Siegal F, Shodell M, Shah K, Larsson M, Lifson J, Nadas A, Marmor M, Hutt R, Margolis D, Garmon D, Markowitz M, Valentine F, Borrow P, Bhardwaj N. Evidence of dysregulation of dendritic cells in primary HIV infection. Blood. 2010;116:3839–3852. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-273763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang JJ, Lacas A, Lindsay RJ, Doyle EH, Axten KL, Pereyra F, Rosenberg ES, Walker BD, Allen TM, Altfeld M. Differential regulation of toll-like receptor pathways in acute and chronic HIV-1 infection. Aids. 2012;26:533–541. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834f3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herbeuval JP, Grivel JC, Boasso A, Hardy AW, Chougnet C, Dolan MJ, Yagita H, Lifson JD, Shearer GM. CD4+ T-cell death induced by infectious and noninfectious HIV-1: role of type 1 interferon-dependent, TRAIL/DR5-mediated apoptosis. Blood. 2005;106:3524–3531. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herbeuval JP, Hardy AW, Boasso A, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Dy M, Shearer GM. Regulation of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand on primary CD4+ T cells by HIV-1: role of type I IFN-producing plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13974–13979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505251102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herbeuval JP, Nilsson J, Boasso A, Hardy AW, Kruhlak MJ, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Dy M, Andersson J, Shearer GM. Differential expression of IFN-alpha and TRAIL/DR5 in lymphoid tissue of progressor versus nonprogressor HIV-1-infected patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7000–7005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600363103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sedaghat AR, German J, Teslovich TM, Cofrancesco J, Jr., Jie CC, Talbot CC, Jr., Siliciano RF. Chronic CD4+ T-cell activation and depletion in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: type I interferon-mediated disruption of T-cell dynamics. J Virol. 2008;82:1870–1883. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02228-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wijewardana V, Soloff AC, Liu X, Brown KN, Barratt-Boyes SM. Early myeloid dendritic cell dysregulation is predictive of disease progression in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001235. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasegawa A, Liu H, Ling B, Borda JT, Alvarez X, Sugimoto C, Vinet-Oliphant H, Kim WK, Williams KC, Ribeiro RM, Lackner AA, Veazey RS, Kuroda MJ. The level of monocyte turnover predicts disease progression in the macaque model of AIDS. Blood. 2009;114:2917–2925. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burdo TH, Soulas C, Orzechowski K, Button J, Krishnan A, Sugimoto C, Alvarez X, Kuroda MJ, Williams KC. Increased monocyte turnover from bone marrow correlates with severity of SIV encephalitis and CD163 levels in plasma. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000842. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilton JC, Johnson AJ, Luskin MR, Manion MM, Yang J, Adelsberger JW, Lempicki RA, Hallahan CW, McLaughlin M, Mican JM, Metcalf JA, Iyasere C, Connors M. Diminished production of monocyte proinflammatory cytokines during human immunodeficiency virus viremia is mediated by type I interferons. J Virol. 2006;80:11486–11497. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00324-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almeida M, Cordero M, Almeida J, Orfao A. Persistent abnormalities in peripheral blood dendritic cells and monocytes from HIV-1-positive patients after 1 year of antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:405–415. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000209896.82255.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azzoni L, Chehimi J, Zhou L, Foulkes AS, June R, Maino VC, Landay A, Rinaldo C, Jacobson LP, Montaner LJ. Early and delayed benefits of HIV-1 suppression: timeline of recovery of innate immunity effector cells. AIDS. 2007;21:293–305. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328012b85f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barron MA, Blyveis N, Palmer BE, MaWhinney S, Wilson CC. Influence of plasma viremia on defects in number and immunophenotype of blood dendritic cell subsets in human immunodeficiency virus 1-infected individuals. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:26–37. doi: 10.1086/345957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finke JS, Shodell M, Shah K, Siegal FP, Steinman RM. Dendritic cell numbers in the blood of HIV-1 infected patients before and after changes in antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Immunol. 2004;24:647–652. doi: 10.1007/s10875-004-6250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fontaine J, Coutlee F, Tremblay C, Routy JP, Poudrier J, Roger M. HIV infection affects blood myeloid dendritic cells after successful therapy and despite nonprogressing clinical disease. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1007–1018. doi: 10.1086/597278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gompels M, Patterson S, Roberts MS, Macatonia SE, Pinching AJ, Knight SC. Increase in dendritic cell numbers, their function and the proportion uninfected during AZT therapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:347–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shedlock DJ, Silvestri G, Weiner DB. Monkeying around with HIV vaccines: using rhesus macaques to define ‘gatekeepers’ for clinical trials. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:717–728. doi: 10.1038/nri2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith SM, Mefford M, Sodora D, Klase Z, Singh M, Alexander N, Hess D, Marx PA. Topical estrogen protects against SIV vaginal transmission without evidence of systemic effect. Aids. 2004;18:1637–1643. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131393.76221.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown KN, Wijewardana V, Liu X, Barratt-Boyes SM. Rapid influx and death of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in lymph nodes mediate depletion in acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000413. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown KN, Trichel A, Barratt-Boyes SM. Parallel loss of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells from blood and lymphoid tissue in simian AIDS. J Immunol. 2007;178:6958–6967. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown KN, Barratt-Boyes SM. Surface phenotype and rapid quantification of blood dendritic cell subsets in the rhesus macaque. J Med Primatol. 2009;38:272–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2009.00353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teleshova N, Kenney J, Jones J, Marshall J, Van Nest G, Dufour J, Bohm R, Lifson JD, Gettie A, Pope M. CpG-C immunostimulatory oligodeoxyribonucleotide activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in rhesus macaques to augment the activation of IFN-gamma-secreting simian immunodeficiency virus-specific T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:1647–1657. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim WK, Sun Y, Do H, Autissier P, Halpern EF, Piatak M, Jr., Lifson JD, Burdo TH, McGrath MS, Williams K. Monocyte heterogeneity underlying phenotypic changes in monocytes according to SIV disease stage. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:557–567. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0209082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tippett E, Cheng WJ, Westhorpe C, Cameron PU, Brew BJ, Lewin SR, Jaworowski A, Crowe SM. Differential expression of CD163 on monocyte subsets in healthy and HIV-1 infected individuals. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dillon SM, Friedlander LJ, Rogers LM, Meditz AL, Folkvord JM, Connick E, McCarter MD, Wilson CC. Blood myeloid dendritic cells from HIV-1-infected individuals display a proapoptotic profile characterized by decreased Bcl-2 levels and by caspase-3+ frequencies that are associated with levels of plasma viremia and T cell activation in an exploratory study. J Virol. 2011;85:397–409. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01118-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malleret B, Karlsson I, Maneglier B, Brochard P, Delache B, Andrieu T, Muller-Trutwin M, Beaumont T, McCune JM, Banchereau J, Le Grand R, Vaslin B. Effect of SIVmac infection on plasmacytoid and CD1c+ myeloid dendritic cells in cynomolgus macaques. Immunology. 2008;124:223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02758.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malleret B, Maneglier B, Karlsson I, Lebon P, Nascimbeni M, Perie L, Brochard P, Delache B, Calvo J, Andrieu T, Spreux-Varoquaux O, Hosmalin A, Le Grand R, Vaslin B. Primary infection with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasmacytoid dendritic cell homing to lymph nodes, type I interferon, and immune suppression. Blood. 2008;112:4598–4608. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mandl JN, Barry AP, Vanderford TH, Kozyr N, Chavan R, Klucking S, Barrat FJ, Coffman RL, Staprans SI, Feinberg MB. Divergent TLR7 and TLR9 signaling and type I interferon production distinguish pathogenic and nonpathogenic AIDS virus infections. Nat Med. 2008;14:1077–1087. doi: 10.1038/nm.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swiecki M, Wang Y, Vermi W, Gilfillan S, Schreiber RD, Colonna M. Type I interferon negatively controls plasmacytoid dendritic cell numbers in vivo. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2367–2374. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang J, Yang Y, Al-Mozaini M, Burke PS, Beamon J, Carrington MF, Seiss K, Rychert J, Rosenberg ES, Lichterfeld M, Yu XG. Dendritic cell dysfunction during primary HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1557–1562. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman M, Deeks SG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nature Medicine. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dillon SM, Robertson KB, Pan SC, Mawhinney S, Meditz AL, Folkvord JM, Connick E, McCarter MD, Wilson CC. Plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells with a partial activation phenotype accumulate in lymphoid tissue during asymptomatic chronic HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48:1–12. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181664b60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krathwohl MD, Schacker TW, Anderson JL. Abnormal presence of semimature dendritic cells that induce regulatory T cells in HIV-infected subjects. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:494–504. doi: 10.1086/499597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Presicce P, Shaw JM, Miller CJ, Shacklett BL, Chougnet CA. Myeloid dendritic cells isolated from tissues of SIV-infected Rhesus macaques promote the induction of regulatory T cells. Aids. 2011;26:263–273. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834ed8df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Q, Schacker T, Carlis J, Beilman G, Nguyen P, Haase AT. Functional genomic analysis of the response of HIV-1-infected lymphatic tissue to antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:572–582. doi: 10.1086/381396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Behbahani H, Landay A, Patterson BK, Jones P, Pottage J, Agnoli M, Andersson J, Spetz AL. Normalization of immune activation in lymphoid tissue following highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25:150–156. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200010010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown CR, Czapiga M, Kabat J, Dang Q, Ourmanov I, Nishimura Y, Martin MA, Hirsch VM. Unique pathology in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rapid progressor macaques is consistent with a pathogenesis distinct from that of classical AIDS. J Virol. 2007;81:5594–5606. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00202-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Igarashi T, Brown CR, Endo Y, Buckler-White A, Plishka R, Bischofberger N, Hirsch V, Martin MA. Macrophage are the principal reservoir and sustain high virus loads in rhesus macaques after the depletion of CD4+ T cells by a highly pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus/HIV type 1 chimera (SHIV): Implications for HIV-1 infections of humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:658–663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021551798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chahroudi A, Bosinger SE, Vanderford TH, Paiardini M, Silvestri G. Natural SIV hosts: showing AIDS the door. Science. 2012;335:1188–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.1217550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herbeuval JP, Shearer GM. HIV-1 immunopathogenesis: how good interferon turns bad. Clin Immunol. 2007;123:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vanderford TH, Slichter C, Rogers KA, Lawson BO, Obaede R, Else J, Villinger F, Bosinger SE, Silvestri G. Treatment of SIV-infected sooty mangabeys with a type-I IFN agonist results in decreased virus replication without inducing hyper immune activation. Blood. 2012 doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-411496. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-1102-411496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tavel JA, Huang CY, Shen J, Metcalf JA, Dewar R, Shah A, Vasudevachari MB, Follmann DA, Herpin B, Davey RT, Polis MA, Kovacs J, Masur H, Lane HC. Interferon-alpha produces significant decreases in HIV load. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2010;30:461–464. doi: 10.1089/jir.2009.0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haas DW, Lavelle J, Nadler JP, Greenberg SB, Frame P, Mustafa N, St Clair M, McKinnis R, Dix L, Elkins M, Rooney J. A randomized trial of interferon alpha therapy for HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16:183–190. doi: 10.1089/088922200309278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reeves RK, Evans TI, Gillis J, Wong FE, Kang G, Li Q, Johnson RP. SIV Infection Induces Accumulation of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in the Gut Mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1462–1468. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lund JM, Linehan MM, Iijima N, Iwasaki A. Cutting Edge: Plasmacytoid dendritic cells provide innate immune protection against mucosal viral infection in situ. J Immunol. 2006;177:7510–7514. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smit JJ, Rudd BD, Lukacs NW. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells inhibit pulmonary immunopathology and promote clearance of respiratory syncytial virus. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1153–1159. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gill MA, Palucka AK, Barton T, Ghaffar F, Jafri H, Banchereau J, Ramilo O. Mobilization of plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells to mucosal sites in children with respiratory syncytial virus and other viral respiratory infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1105–1115. doi: 10.1086/428589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]