Abstract

Monocytes and macrophages respond to and govern inflammation by producing a plethora of inflammatory modulators, including cytokines, chemokines and arachidonic acid (C20:4)-derived lipid mediators. One of the most prevalent inflammatory diseases is cardiovascular disease, caused by atherosclerosis, and accelerated by diabetes. Recent research has demonstrated that monocytes/macrophages from diabetic mice and humans with type 1 diabetes show upregulation of the enzyme, acyl-CoA synthetase 1 (ACSL1), which promotes C20:4 metabolism, and that ACSL1 inhibition selectively protects these cells from the inflammatory and pro-atherosclerotic effects of diabetes, in mice. Increased understanding of the role of ACSL1 and other culprits in monocytes/macrophages in inflammation and diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis offers hope for new treatment strategies to combat diabetic vascular disease.

Keywords: Acyl-CoA synthetase, Arachidonic acid, Eicosanoids, Macrophage, Monocyte

Diabetes Accelerates Atherosclerosis

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus is rapidly increasing. It is estimated that close to 350 million people worldwide have diabetes. Most people with diabetes suffer from type 2 diabetes (T2D), whereas the autoimmune T1D is less prevalent (see Glossary). Fortunately, since the discovery of insulin, T1D is often successfully managed by insulin treatment, while T2D is managed by combinations of insulin treatment and/or oral drugs aimed to increasing insulin action or secretion from the insulin producing pancreatic beta cells. Furthermore, T2D and associated complications can be largely managed by strict adherence to a healthy diet, regular physical activity, maintenance of normal body weight, and by avoiding tobacco, actions that also play important roles in the treatment of complications in people with T1D.

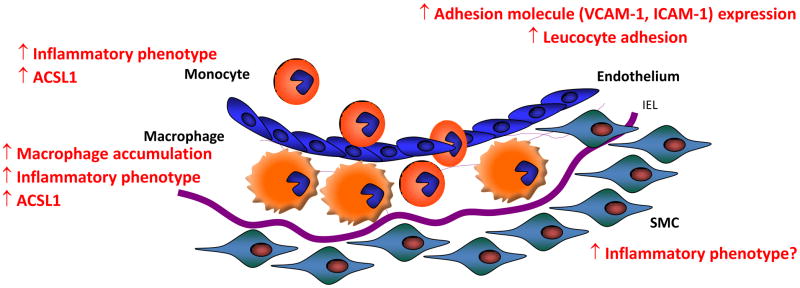

Even with the treatment strategies available today, both T1D and T2D frequently lead to complications, such as cardiovascular disease, resulting in heart attacks and strokes (Box 1). Diabetes increases the risk of cardiovascular disease by 2–4-fold by accelerating the formation and/or progression of atherosclerotic lesions [1]. The accelerated atherosclerosis is now believed to be driven, at least in part, by the altered function and properties of monocytes and macrophages, cells that display and contribute to an increased inflammatory vascular state during the development of atherosclerosis [2] (Figure 1).

Box 1. Brief overview of atherosclerosis.

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease in which lesions or plaques build up in certain locations and arteries in the body. The first step in initiation of these lesions is an increased activation of cells in the blood vessel wall, such as the endothelial cells, which line the inside (lumen) of the blood vessel. This activation might be the result of high cholesterol levels, smoking, T1D or T2D. As a result, circulating monocytes attach to, and then migrate through, the endothelium. Once within the blood vessel wall, these cells become activated macrophages, which synthesize and release a plethora of inflammatory mediators, proteases, and other proteins and lipids. As time passes, arterial SMCs also become activated and start to proliferate and move into the macrophage-rich developing lesion. In advanced lesions, cells are dying, and necrotic cores and cholesterol clefts are formed. Some unstable plaques can fissure or rupture, which may cause rapid thrombus formation and blockade of blood flow. Depending on the location of this blockade, this process can cause a heart attack or stroke.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of atherosclerotic lesion initiation in mouse models of T1D.

Atherosclerotic lesion initiation is accelerated in mouse models of T1D in the absence of diabetes-induced hyperlipidemia. The effect of diabetes in these models is due to an increased macrophage accumulation in the arterial wall. Increased adhesion molecule expression in endothelial cells, which allows monocytes to attach and invade the arterial wall, is generally thought to mediate the increased macrophage accumulation. Recent research shows that the enzyme ACSL1 is induced in monocytes and macrophages in the setting of diabetes, and mediates the effects of diabetes on the inflammatory phenotype in these cells and on macrophage accumulation in the artery wall. It is not known if SMCs take on a more inflammatory phenotype in diabetes in vivo. Furthermore, it is unknown whether ACSL1 is induced in endothelial cells and SMCs exposed to diabetes or hyperglycemia, and the role of ACSL1 in these cells. IEL; internal elastic lamina, SMS; smooth muscle cells.

Long-chain fatty acids (FAs) are also believed to exert inflammatory actions in cells, in particular in states of insulin resistance and diabetes. The enzyme ACSL1, which converts long-chain FAs into their acyl-CoA derivatives, has recently emerged as causal to the enhanced inflammation and atherosclerosis associated with diabetes, in mouse models of T1D [3].

This review describes new findings in the area of diabetes-exacerbated atherosclerosis and inflammation, with emphasis on the few mediators that have been identified in monocytes/macrophages in the setting of diabetes. The discussed findings in human subjects are for the most part focused on T1D rather than T2D because T2D is associated with a number of cardiovascular risk factors, such as dyslipidemia, hypertension and an inactive life style, all of which are important contributors to cardiovascular disease even before the onset of frank T2D [4–5]. The rodent models discussed are models in which destruction of the insulin producing pancreatic beta cells results in severe hyperglycemia and diabetes. Destruction of beta cells can be induced by toxins, such as streptozotocin, or by T cells attacking beta cells expressing a viral transgene. Beta cell destruction or dysfunction occurs in both T1D and T2D in humans. The autoimmune aspects of T1D are most closely mimicked by the virally induced transgenic mouse model of diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis [3, 6]. However, it is important to keep in mind that these are models of aspects of T1D, and that no animal model mimics exactly the pathophysiology of human T1D or T2D. When fed diets rich in saturated fat, these mouse models develop dyslipidemia, and thus take on certain aspects of T2D.

Production of inflammatory protein and lipid mediators in innate immune cells, in diabetes

Both T1D and T2D in humans and beta cell destruction/diabetes in rodents result in an increased inflammatory phenotype of monocytes and macrophages [3, 7–9], an effect that appears to be in part due to increased expression of toll-like receptors (TLR2 and TLR4) [9]. TLRs are pattern recognition receptors that respond to pathogens and endogenous danger molecules, resulting in inflammatory activation. Monocytes and macrophages from humans with T1D and mouse models of T1D have been shown to produce increased levels of cytokines, such as IL1-β, IL-6 and TNF-α [3, 7–8] that activate their cognate receptors thus propagating an inflammatory state. In macrophages, an increased production of inflammatory cytokines is associated with an increased production of arachidonic acid (C20:4)-derived lipid mediators. The C20:4 cascade generates a large number of eicosanoids, including prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes and other products (Box 2). Some of these lipids exert inflammatory effects whereas others are anti-inflammatory or are involved in resolution of inflammation. The role of prostanoids in inflammation has recently been reviewed elsewhere [10], and will not be reviewed here. Instead, the emerging evidence that altered C20:4 handling in monocytes and macrophages plays a role in diabetes-exacerbated inflammation and atherosclerosis will be discussed.

Box 2. Brief overview of eicosanoid production from arachidonic acid.

In humans, arachidonic acid (C20:4) is obtained through the diet or synthesized from linoleic acid (C18:2). Once taken up by cells, C20:4 becomes an important component of cellular membrane phospholipids. C20:4 is released from the membrane phospholipid pool following activation of the enzyme phospholipase A2. Free C20:4 gives rise to a number of eicosanoids with important biological functions. There are several different branches of biosynthesis of eicosanoids from C20:4. One branch involves conversion of C20:4 to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) by the action of cyclooxygenases (COX-1 and COX-2). PGH2 is a precursor of several different branches of prostaglandin and thromboxane biosynthesis. For example, prostacyclin synthase catalyzes conversion of PGH2 to PGI2 (prostacyclin), which is an eicosanoid with important vasorelaxant properties, PGESs produce PGE2 and downstream PGF2α (a vasoconstrictor), prostaglandin D synthase produces PGD2, and thromboxane synthase produces thromboxanes, which play crucial roles in blood clotting. The other branch of eicosanoid synthesis from C20:4 leads to leukotriene synthesis by the action of lipoxygenases (5-LOX and 12/15-LOX) and downstream enzymes. All these processes are under strict control by the many enzymes and enzyme isoforms involved. Thus, in normal conditions a balanced production of eicosanoids maintains physiological homeostasis. However, in certain disease states, one or a few branches of eicosanoid synthesis expands, perhaps at the cost of other branches, due to upregulation of enzymes, resulting in a skewed production of a subset of eicosanoids.

Inflammatory macrophages exhibit altered arachidonic acid handling

Macrophages produce a number of eicosanoids under basal conditions, including prostaglandins E2 (PGE2) and D2 (PGD2), thromboxane B2 (TxB2) and 6-keto prostaglandin F1α (PGF1α, an indirect measure of PGI2), with lower levels of the eicosanoid 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE) [10–11]. Activation of macrophages by inflammatory stimuli, such as TLR4 ligands, causes marked changes in absolute and relative levels of eicosanoids produced [10–12]. Lipidomics and systems biology approaches [11–12] have demonstrated that macrophages activated by the TLR4 ligand lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or by its lipid moiety lipid A, exhibit increased gene expression of the cytosolic phospholipase A2 Pla2g4a, which liberates C20:4 from phospholipids, following activation. Furthermore, C20:4-enriched phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine are increased in activated macrophages [13]. Accordingly, TLR4 activation results in increased levels of C20:4, increased cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression, and increased production of PGE2, a prostaglandin produced downstream of COX-2, mainly due to concomitantly increased expression and association with microsomal prostaglandin E synthase (PGES-1) [10]. In addition, PGE2 enhances COX-2 and PGES-1 expression [14], resulting in a positive amplification loop. A C20:4 cascade-targeted lipidomics approach was recently used to investigate metabolites involved in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. These studies identified macrophage PGES-1 as a mediator [15]. Thus, inflammatory activation of macrophages appears to result in preferential activation of the COX-2 and PGES-1 arm of the C20:4 cascade, although other prostaglandins downstream of COX-2, such as PGD2 and PGF2α are also elevated, as is the 5-lipoxygenase product 5-HETE [11–12].

Altered C20:4 metabolism in diabetes

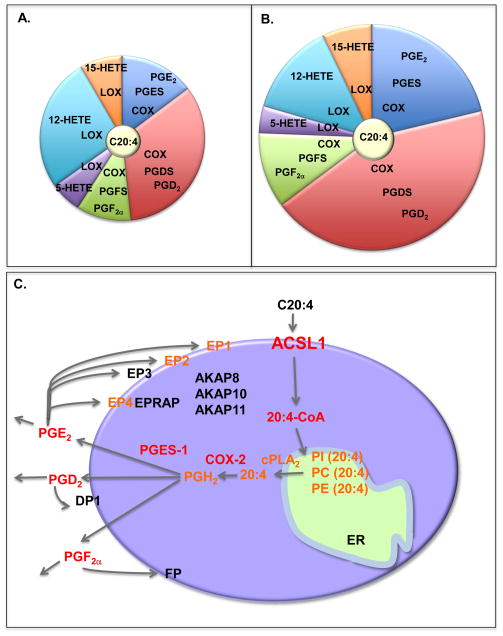

In line with the finding that monocytes and macrophages take on a more inflammatory phenotype in the setting of diabetes [7–9], monocytes and macrophages from diabetic rodents and humans often exhibit increased C20:4 metabolism; indeed, overproduction of arachidonoyl-CoA, COX-2 and PGE2 has been observed in monocytes and macrophages from rodent models of T1D and human subjects with T1D or T2D as compared to controls [3], [8], [16–17]. In one study on CD14+ monocytes from human subjects, COX-2 was found to be downregulated in subjects with juvenile onset T1D, but upregulated in subjects with adult onset T1D, latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult (LADA) or T2D, as compared to controls [8]. In the same study, all types of diabetes were associated with increased gene expression of the monocyte chemokines chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 7 (CCL7) and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) [8]. The decreased COX-2 levels in juvenile onset T1D subjects was recently suggested to be due to gene-environment interactions because a similar downregulation was observed in non-diabetic co-twins [18]. Levels of other eicosanoids, including lipoxygenase products, are also likely to be altered by diabetes [16], [19]. Some of the effect of diabetes on macrophage C20:4 handling might be due to hyperglycemia [16]. For example, classically activated mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages, activated with LPS and IFNγ for 48 h, and maintained in a normal glucose concentration, produce PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, 12-HETE, 15-HETE, 5-HETE, and much less leukotriene B4 (Figure 2A) [3]. When these cells are differentiated in a high glucose concentration (25 mM), the absolute amounts of these eicosanoids increase by about 2-fold, as do the relative amounts of primarily PGD2 and PGE2 (Figure 2B) [3]. Thus, monocytes and macrophages exposed to glucose levels found in poorly controlled diabetes mimic, at least to some extent, the response of these cells to diabetes.

Figure 2. Increased ACSL1 expression and eicosanoid production in macrophages under diabetic conditions.

A. Relative levels of some of the prostanoids produced by classically activated mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages differentiated in the presence of a normal (5.5 mM) glucose concentration and then stimulated with LPS and IFNγ for 48 h. B. When bone marrow-derived macrophages are differentiated in high concentration of glucose, such as that observed in diabetic mice (25 mM), the total amount of the prostanoids increases, as well as the relative levels of PGD2 and PGE2. C. A proposed role for ACSL1 in arachidonic acid handling in an inflammatory macrophage is shown. Arachidonic acid (C20:4) is taken up by macrophages through diffusion across the plasma membrane or by FA transport proteins. C20:4 is rapidly converted to arachidonoyl-CoA (20:4-CoA) by ACSL1 and perhaps other enzymes with acyl-CoA synthetase activity. This reaction traps C20:4 within the cell because of the bulky hydrophilic CoA moiety, and also allows it to be incorporated into phospholipids, such as phosphatidylinolsitol (PI), phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), through reacylation or through de novo synthesis. Activation of cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2) liberates C20:4 from phospholipids and makes it available for eicosanoid production. In macrophages subjected to an inflammatory environment, such as diabetes or following TLR4 activation, production of eicosanoids is skewed toward a pathway mediated by cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2). The COX-2 pathway results in enhanced production of prostaglandin PGE2, PGD2 and PGF2α, after TLR4 stimulation or in the setting of diabetes. These prostaglandins in turn act on other cells, or bind to specific receptors on the macrophage, resulting in activation of intracellular signal transduction pathways. Downstream signaling from these receptors is in turn governed by a number of modulators, such as A-kinase anchor proteins (AKAPs). Thus, induction of ACSL1 in inflammatory macrophages has the potential to enhance and fine-tune a complex network of potent modulators of the inflammatory response. Red font, mediators shown to be increased by diabetes; orange font, mediators shown to be increased by inflammatory stimuli, e.g. TLR4 activation.

What is the biological effect of increased eicosanoid production in macrophages from diabetic mice?

PGE2 is an important modulator of inflammatory processes [10]. In vivo studies of rodent disease models support the notion that an important inflammatory effect is mediated by PGES-1, although one confounding factor is that macrophages from PGES-1-deficient mice show rediversion from PGE2 to other prostanoids [10]. However, PGE2 can also exert anti-inflammatory effects in macrophages by inhibiting LPS-stimulated cytokine production [20]. Part of the complex effects of PGE2 on inflammatory endpoints in macrophages can be explained by the fact that PGE2 binds to four different G-protein-coupled receptors (EP1–4), all of which are expressed in monocytes/macrophages [10]. EP4-deficient macrophages produce reduced levels of IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2, and COX-2, 5 h after LPS stimulation, whereas EP2-deficiency has no effect [21]. PGE2-mediated inflammatory effects are further regulated by intracellular proteins that modulate pathways downstream of its receptors. PGE2 enhances LPS-stimulated IL-6 secretion from macrophages through cAMP signaling, and this effect is dependent on the protein kinase A (PKA) anchoring proteins AKAP10 and AKAP11 [22]. Conversely, PGE2 inhibits TLR4-stimulated TNF-α production by an AKAP8-dependent pathway. A protein known as EP4 receptor-associated protein (EPRAP) has also been shown to mediate acute suppressive effects of PGE2 on LPS signaling in macrophages [20].

In addition, PGE2 appears to restrain certain aspects of macrophage differentiation through the EP2 receptor [23]. These results bear similarity to those of Hertz et al. [24] in which human CD14+ monocytes were differentiated in the presence of the cyclic AMP-elevating agent forskolin, or PGE2. Cyclic AMP elevation prevented expression of some, but not all, differentiation markers. Array studies revealed that several chemokines and other inflammatory molecules were increased by cAMP elevation, including many CCL and CXCL cytokines [24].

Together, these findings highlight the temporal aspects of PGE2 signaling in macrophages, and raise the possibility that different pools of cAMP modulate inflammatory signaling in distinct ways, in response to PGE2 and diabetes. The effects of diabetes, elevated glucose levels and inflammatory activation on selected prostaglandin pathways in macrophages are illustrated in figure 2C. Strikingly, almost every step in C20:4 processing leading to prostaglandin production through a pathway mediated by COX-2, has been found to be increased by diabetes, elevated glucose levels or other inflammatory stimuli.

Recent research has demonstrated that ACSL1 is behind the altered C20:4 handling in monocytes and macrophages in mouse models of T1D, leading to increased inflammatory properties of these cells and diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis. Thus, the increased eicosanoid production is likely to exacerbate the inflammatory phenotype of monocytes and macrophages in diabetes, although further studies are needed to elucidate the role of the different eicosanoids, their receptors and downstream signaling under diabetic conditions.

ACSL1 mediates the inflammatory effects of diabetes in monocytes and macrophages in mouse models of T1D

ACSL1 belongs to a gene family of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases, which acts on long-chain FAs and esterifies them into their acyl-CoA derivatives [25]. The FA substrate specificity of ACSL1 is broad, and deletion of this enzyme results in reduced levels of all common 16 and 18 carbon acyl-CoAs, in heart [26] and liver [27]. In these tissues and in the adipose tissue, ACSL1 mediates FA utilization for beta-oxidation and incorporation of FAs into lipid pools, such as phospholipids [26–28]. Recently, the role of ACSL1 was analyzed in myeloid cells, by using targeted deletion of ACSL1 in these cells [3]. Initial observations revealed that ACSL1 expression is increased in monocytes and macrophages from two mouse models of T1D, and in monocytes from human subjects with T1D, compared to non-diabetic controls [3]. ACSL1 expression is also stimulated by LPS and IFNγ in human and mouse macrophages, demonstrating that ACSL1 is induced in classically activated inflammatory macrophages.

Surprisingly, ACSL1-deficient macrophages did not show impaired beta-oxidation, contrary to findings in liver, adipose tissue and heart, and ACSL1-deficient macrophages from mice fed a low fat diet did not exhibit impaired neutral lipid accumulation. Instead, ACSL1-deficiency in macrophages resulted in a rather selective reduction in arachidonoyl-CoA levels [3]. Furthermore, ACSL1- deficiency completely prevented an increased PGE2 production in macrophages from T1D mouse models, without affecting levels in macrophages from non-diabetic mice. The protective effect of ACSL1-deficiency on PGE2 release from macrophages was correlated with a similar protection from diabetes-induced production of IL-1β, IL-6 and CCL2. Interestingly, ACSL1-deficiency had no significant effect in macrophages or monocytes from non-diabetic mice, suggesting that ACSL1 specifically mediates the inflammatory effects seen in monocytes/macrophages, in T1D [3].

The effects of ACSL1-deficiency on cytokine production are most likely mediated by reduced synthesis of arachidonoyl-CoA and concomitant reduction in the availability of C20:4 for eicosanoid production, although other mechanisms might also be involved. For example, a COX-2 inhibitor was able to mimic the effects of ACSL1-deficiency in macrophages from diabetic mice, but had no effect on cells lacking ACSL1 [3]. One possibility is that the main effect of ACSL1 is to facilitate C20:4 uptake and trapping in the cell. The reduced arachidonoyl-CoA levels might, over time, deplete the membrane phospholipid pool of C20:4 available as a substrate for PLA2. It is unlikely that ACSL1 acts on the pool of free C20:4 generated following PLA2 activation, because this would presumably result in increased eicosanoid production in ACSL1-deficient cells, rather than reduced production. Another possibility is that ACSL1 acts primarily on linoleic acid (C18:2) converting it into linoleoyl-CoA that can be used for C20:4 production within the macrophage. ACSL1 is able to use exogenous C18:2 in macrophages [29]. The exact mechanism of ACSL1-mediated inflammatory effects needs to be further evaluated.

The effect of myeloid ACSL1-deficiency appears to be specific to monocytes and macrophages exposed to the environment of diabetes in mouse models of T1D, most likely because C20:4 handling and COX-2-mediated eicosanoid production is ramped up by diabetes in these models. It would be interesting to evaluate the effect of ACSL1-deficiency in other inflammatory states associated with increased prostanoid production, such as the mouse model of multiple sclerosis [15].

Myeloid ACSL1 is a mediator of diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis

The studies highlighted above demonstrate that diabetes-exacerbated inflammation is associated with increased cytokine and chemokine production in monocytes/macrophages, and that loss of ACSL1 results in a specific reduction in diabetes-associated inflammation. Monocytes and macrophages play crucial roles in all stages of atherosclerosis [2], and the early stages of diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis are due to an increased accumulation of macrophages within the arterial wall [30]. Few studies have investigated the mechanism behind the accelerated atherosclerotic lesion formation observed in diabetes, in mouse models that do not have the confounding factor of diabetes-induced dyslipidemia. The most frequently used mouse models of atherosclerosis are the low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient (Ldlr−/−) and the apolipoprotein E-deficient (Apoe−/−) mice, because these mice exhibit lipoprotein profiles that are more similar to those of humans than those of wildtype mice, and are therefore susceptible to atherosclerosis [31–33]. Diabetes can be induced in these models by using beta-cell toxins, such as streptozotocin or alloxan. More recently, an Ldlr−/− mouse model has been developed that expresses a viral transgene under control of the insulin promoter. This mouse develops diabetes characterized by T cell-mediated destruction of the pancreatic beta cells following injection of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [6]. Other models of diabetes have also been used to study diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis, including the leptin-deficient ob/ob mouse [34], and the Akita mouse, which carries a single copy of a dominant mutation in the Ins2 gene [35]. However, in these models and in fat-fed Ldlr−/− or Apoe−/− mice, the increased atherosclerosis appears to be due primarily to dyslipidemia, and the effect of diabetes is masked [6] [34]. Recently, an Apoe−/− mouse model with reduced expression of the insulin receptor and insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) has been developed [36]. This model shows increased atherosclerosis and impaired insulin signaling in the absence of lipid abnormalities or hyperglycemia, as compared to Apoe−/− mice, and is therefore a promising model of some aspects of atherosclerosis associated with T2D.

The role of myeloid ACSL1-deficiency in diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis was investigated by transplanting bone marrow from mice with myeloid ACSL1-deficiency or wild type (wt) littermates, into the virally-induced Ldlr−/− model of diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis [3] [6]. These studies demonstrated that myeloid ACSL1-deficiency protects the mice from diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis but does not affect lesion formation in non-diabetic mice, similar to the protective effects of ACSL1-deficiency observed on the inflammatory phenotype of monocytes and macrophages, in this mouse model of T1D [3]. The protective effect of myeloid ACSL1-deficiency in diabetic mice was a result of reduced macrophages accumulation in the arterial wall. ACSL1 is the first target shown to specifically mediate diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis in mice.

Are the protective effects of myeloid ACSL1-deficiency due to a reduced eicosanoid production in monocytes and macrophages under diabetic conditions? The in vitro studies discussed above certainly suggest that this is a plausible mechanism. The effect of deletion of other enzymes or proteins involved in myeloid cell eicosanoid production has not yet been evaluated in mouse models of T1D, but several studies have been done in non-diabetic mice [10]. For example, deletion of COX-2 or the PGE2 receptor EP4 in myeloid cells resulted in protection against atherosclerosis [reviewed in 10, PGE2, PGF2α and TxB2 were found to promote atherosclerosis, whereas PGI2 exerted anti-atherosclerotic effects [reviewed in 10]. One set of studies has addressed the role of thromboxane in promoting atherosclerosis in diabetic hyperlipidemic Apoe−/− mice. Pharmacological inhibition of thromboxane receptors, using the TxA2 antagonist S18886, attenuated diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis without affecting plasma cholesterol or glucose [37]. This study supports a role for production of pro-atherosclerotic prostanoids in the setting of diabetes.

Pro-atherogenic proteins not directly involved in C20:4 metabolism might act by inhibiting eicosanoid production in monocytes and macrophages, indirectly. For example, studies in mice deficient in fatty acid binding protein (FABP) 4 provided one of the first examples of how intracellular handling of FA can modulate inflammatory changes in macrophages [38]. FABPs are intracellular lipid chaperones. Similar to ACSL1, FABP4 is induced following TLR2 and TLR4 stimulation in macrophages, suggesting a role for this protein in modulating inflammatory processes [39]. Deficiency in either FABP4 or FABP5 results in macrophages with reduced production of PGE2, TNF-α, IL-6 and CCL2, after LPS stimulation [40], likely due to increased PPARγ activity [41], and deletion of FABP4 or FABP5 in bone marrow cells reduces atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− and Apoe−/− mice [42]. Interestingly, FABP4 can be detected in human atherosclerotic lesions and correlates with intra-plaque hemorrhage and lipid core size, both of which are characteristics of vulnerable plaques thought to lead to clinical symptoms [43]. In another study, expression of FABP4 in lesions from patients undergoing endarterectomy, a surgical procedure to remove plaque material from an artery, correlated with plaque instability in carotid atherosclerosis [44]. Furthermore, serum FABP4 levels have been correlated with cardiovascular events [45–46].

Other macrophage enzymes involved in diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis

Although ACSL1 is the only myeloid enzyme to date that has been shown to mediate the effects of diabetes on atherosclerosis, other enzymes were shown to play causative roles in diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis in mice, partly by affecting macrophages. The enzyme glutathione peroxidase-1 (Gpx1), a member of the glutathione peroxidase family that functions in the detoxification of hydrogen peroxide, was found to be atheroprotective as its deletion enhanced diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis [47]. Interestingly, whole-body Gpx1- deficiency had no effect on atherosclerotic lesions in chow-fed non-diabetic Apoe−/− mice, but significantly exacerbated atherosclerosis in streptozotocin- diabetic mice, through increased lesion content of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and macrophages, although the relative contribution of macrophage Gxp1 was not tested, in this study [47]. Fat-fed Apoe−/− mice with Gpx1-deficiency show the same enhanced atherosclerosis as the diabetic mice, demonstrating that the effect is not specific to diabetes [48], contrary to the effect of ACSL1-deficiency. In another study, human aldose reductase was expressed in Ldlr+/− mice to achieve enzyme levels similar to those found in humans [49]. In this study, aldose reductase overexpression specifically enhanced diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis, without effecting atherosclerosis in non-diabetic mice [49]. The enzyme reduces aldehyde molecules to the corresponding alcohol, e.g. glucose to sorbitol [49]. Peritoneal macrophages from these mice were found to have more inflammatory properties, as they expressed higher levels of Nos2 and Il6 mRNA and showed greater uptake of modified lipoproteins [50]. In addition to its effects in macrophages, the pro-atherosclerotic phenotype observed in diabetic mice overexpressing aldose reductase might be due in part to its effects in endothelial cells [51]. Further studies are needed to elucidate the monocyte/macrophage contribution of aldose reductase and Gxp1 in diabetes- accelerated atherosclerosis, and whether these pathways interact with the ACSL1 pathway.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Collectively, recent research provides strong evidence that induction of ACSL1 in monocytes and macrophages promotes diabetes-induced inflammatory changes in these cells, as well as diabetes-accelerated formation of atherosclerotic lesions in a mouse model of T1D. It will be important to further evaluate the ACSL1 pathway in humans with different forms of diabetes. Furthermore, the finding that ACSL1 levels correlate with arachidonoyl-CoA levels and PGE2 production by macrophages, add further strength to the notion that C20:4 handling is altered in diabetes, and suggest that diabetic vascular disease might have, at least in part, an etiology that is different from vascular disease in the absence of diabetes.

These findings have generated new sets of interesting questions. For example, what factors within the diabetic environment are responsible for induction of ACSL1 in myeloid cells? Why is the regulation of ACSL1 different in myeloid cells, as compared to for example liver or adipose tissue, in which Acsl1 is a PPARα and PPARγ target gene, respectively [52–53], and why does ACSL1 prefer C20:4 as a substrate in macrophages [3] whereas it has a much broader substrate preference in other tissues [26–27]? Another important question is whether ACSL1 is upregulated in other vascular cells involved in atherosclerosis, and what role(s) it might play in these cells (Figure 1). It is not known if ACSL1 plays a role in mediating the increased adhesion molecule expression in endothelial cells, nor is the role of ACSL1 in smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in diabetes understood. In vitro studies have shown that overexpression of ACSL1 in human SMCs results in increased levels of C20:4-CoA, but also other acyl-CoA species [54]. Without doubt, the most important question is whether ACSL1 and other factors identified in mouse models play equally important roles in diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis in humans. Interestingly, ACSL1 gene polymorphisms were recently found in patients with ventricular fibrillation, and SNPs in ACSL1 and ACSL3 were associated with survival in these patients [55], suggesting a possible role for ACSL1 in cardiovascular disease in humans.

Could ACSL1 be a promising drug target in the treatment of diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis? Previous studies suggest that proteins involved in FA handling can be good drug target candidates, and this strategy can be successful in inhibiting atherosclerosis, at least in mouse models [56]. Based on mouse targeted ACSL1 knockout studies, systemic inhibition of ACSL1 would likely lead to cardiac hypertrophy without immediate cardiac dysfunction [26], a slight increase in fat mass, and cold intolerance [28], due to the role of ACSL1 in beta-oxidation in heart and adipose tissue. In mice with tamoxifen inducible ACSL1-deficiency in multiple tissues, a slight increase in body weight due to increased fat mass, and a slight reduction in glucose levels attributed to an increased glucose utilization by the heart, were observed 10 weeks after tamoxifen injection [26]. Thus, long-term systemic ACSL1 inhibition would likely cause side-effects unrelated to inhibition of inflammatory effects in monocytes/macrophages and diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis. Another possibility would be to expand the search for drug targets in the ACSL1-mediated activation pathway in myeloid cells upstream of ACSL1 induction or downstream of ACSL1 action. Selective inhibition of ACSL1 in myeloid cells might be yet another approach, and such strategies are now in development. For example, nanoparticle-encapsulated, fluorescently tagged siRNA has been shown to rapidly redistributed from the blood pool to the spleen and bone marrow, and this approach has shown that treatment of mice with clinically feasible doses of siRNA substantially reduced regional recruitment of inflammatory monocytes and attenuated atherosclerosis and other manifestations of inflammatory disease [57]. Orally delivered siRNA targeting phagocytic cells could be efficient in reducing ACSL1 in these cells. Issues such as the feasibility and cost of using nanoparticles for long-term treatment of cardiovascular disease, and the possibility of antibody development against nanoparticles would have to be addressed before such treatments could become a reality in humans. Furthermore, a general inhibition of the ability of myeloid cells to respond to inflammatory insult is likely to result in unwanted effect. Thus, targeting a pathway that is specifically activated in myeloid cells in diabetes is particularly attractive.

Outstanding Questions.

Does diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis have an etiology that differs in part from atherosclerosis in the non-diabetic setting, and are there differences between atherosclerosis associated with different forms of diabetes?

Why is ACSL1 induced by different stimuli in monocytes/macrophages, as compared to typical insulin target tissues, and why is its function and FA preference different compared to these tissues, e.g. adipose tissue and liver?

Is ACSL1 upregulated in other vascular cells by diabetes, and if so, what role does such an upregulation play in these cells?

What is the importance of ACSL1 and other myeloid cell mediators identified in mouse models of diabetes in diabetes-exacerbated cardiovascular disease in humans?

Acknowledgments

We apologize that we were unable to cite many important contributions. This study was supported in part by NIH grants HL062887, HL092969, and HL097365 to KEB and the Diabetes Research Center at the University of Washington (P30 DK017047).

Glossary

- Acyl-CoA synthetases

Enzymes that catalyze the conversion of FFAs into their activated acyl-CoA derivatives, which are in turn used in the cell for beta-oxidation, synthesis or re-acylation of many different cellular lipids, and other cellular processes. There are five long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase genes (Acsl1, Acsl3, Acsl4, Acsl5 and Acsl6), which give rise to multiple splice variants. Typically, a given cell type expresses several ACSL isoforms, which are believed to have non-redundant functions. Other enzymes, in addition to the five ACSLs also have acyl-CoA synthetase activity

- Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease that affects certain blood vessels in the body (see Box 1). It can lead to heart attack and stroke

- Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is a disease characterized by elevated blood glucose levels due to insufficient production of the hormone insulin or to a reduced ability of insulin to mediate its blood glucose-lowering effects. The most common types of diabetes are T1D, T2D and gestational diabetes, but other less common forms of diabetes exist. T1D is an autoimmune disease, usually manifested in children and young adults, which causes in destruction of pancreatic beta cells, the cells that make insulin. Treatment with insulin is therefore necessary. In adults, T1D accounts for about 5 percent of all diagnosed cases of diabetes. T2D accounts for about 90 to 95 percent of all diagnosed cases of diabetes, and affects primarily adults, although the number of children affected is increasing. T2D often begins as insulin resistance (an inability of insulin to mediate its effects), and eventually results in reduced insulin production. This form of diabetes is associated with obesity, a family history of diabetes, physical inactivity, and race/ethnicity. Gestational diabetes is a form of diabetes diagnosed during pregnancy

- Eicosanoids

Bioactive lipids made by oxidation of twenty-carbon fatty acids, such as arachidonic acid (from the Greek eicosa, meaning “twenty”)

- Long-chain fatty acids

Carboxylic acids with long hydrocarbon chains, usually an even number of carbons. FAs are often described by their common name (for example, palmitic acid) and/or by the number of carbons and double bonds (for example C16:0). Common long-chain saturated FAs include palmitic acid (C16:0) and stearic acid (C18:0), common unsaturated FAs include oleic acid (C18:1), linoleic acid (C18:2) and arachidonic acid (C20:4). More specific nomenclature systems are used as well. FAs are used as a source of energy and as building blocks of many cellular lipids

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bornfeldt KE, Tabas I. Insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2011;14:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2011;145:341–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanter JE, et al. Diabetes promotes an inflammatory macrophage phenotype and atherosclerosis through acyl-CoA synthetase 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E715–E724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111600109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy SM. Pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:635–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu FB, et al. Elevated risk of cardiovascular disease prior to clinical diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1129–1134. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renard CB, et al. Diabetes and diabetes-associated lipid abnormalities have distinct effects on initiation and progression of atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:659–668. doi: 10.1172/JCI17867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradshaw EM, et al. Monocytes from patients with type 1 diabetes spontaneously secrete proinflammatory cytokines inducing Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:4432–4439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padmos RC, et al. Distinct monocyte gene-expression profiles in autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:2768–2773. doi: 10.2337/db08-0496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jialal I, Kaur H. The role of toll-like receptors in diabetes-induced inflammation: Implications for vascular complications. Curr Diab Rep. 2012 Feb 8; doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0258-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricciotti E, FitzGerald GA. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:986–1000. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabido E, et al. Targeted proteomics of the eicosanoid biosynthetic pathway completes an integrated genomics-proteomics-metabolomics picture of cellular metabolism. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012 Feb 23; doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.014746. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buczynski MW, et al. Thematic Review Series: Proteomics. An integrated omics analysis of eicosanoid biology. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1015–1038. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900004-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balgoma D, et al. Markers of monocyte activation revealed by lipidomic profiling of arachidonic acid-containing phospholipids. J Immunol. 2010;184:3857–3865. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Díaz-Muñoz MD, et al. Involvement of PGE2 and the cAMP signalling pathway in the up-regulation of COX-2 and mPGES-1 expression in LPS-activated macrophages. Biochem J. 2012;443:451–461. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kihara Y, et al. Targeted lipidomics reveals mPGES-1-PGE2 as a therapeutic target for multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21807–21812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906891106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Natarajan R, Nadler JL. Lipid inflammatory mediators in diabetic vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1542–1548. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000133606.69732.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo CJ. Upregulation of cyclooxygenase-II gene and PGE2 production of peritoneal macrophages in diabetic rats. J Surg Res. 2005;125:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beyan H, et al. Monocyte gene-expression profiles associated with childhood-onset type 1 diabetes and disease risk: a study of identical twins. Diabetes. 2010;59:1751–1755. doi: 10.2337/db09-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou YJ, et al. Expanding expression of the 5-lipoxygenase/leukotriene B4 pathway in atherosclerotic lesions of diabetic patients promotes plaque instability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minami M, et al. Prostaglandin E receptor type 4-associated protein interacts directly with NF-kappaB1 and attenuates macrophage activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9692–9703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709663200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babaev VR, et al. Macrophage EP4 deficiency increases apoptosis and suppresses early atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2008;8:492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SH, et al. Distinct protein kinase A anchoring proteins direct prostaglandin E2 modulation of Toll-like receptor signaling in alveolar macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8875–8883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.187815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaslona Z, et al. Prostaglandin E2 restrains macrophage maturation via E prostanoid receptor 2/protein kinase A signaling. Blood. 2012;119:2358–2367. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-374207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hertz AL, et al. Elevated cyclic AMP and PDE4 inhibition induce chemokine expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21978–21983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911684106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellis JM, et al. Acyl-coenzyme A synthetases in metabolic control. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:212–217. doi: 10.1097/mol.0b013e32833884bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellis JM, et al. Mouse cardiac acyl coenzyme a synthetase 1 deficiency impairs fatty acid oxidation and induces cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1252–1262. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01085-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li LO, et al. Liver-specific loss of long chain acyl-CoA synthetase-1 decreases triacylglycerol synthesis and beta-oxidation and alters phospholipid fatty acid composition. J Biol Chem 2009. 2009;284:27816–27826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis JM, et al. Adipose acyl-CoA synthetase-1 directs fatty acids toward beta-oxidation and is required for cold thermogenesis. Cell Metab. 2010;12:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanter JE, et al. Acyl-CoA synthetase 1 is required for oleate and linoleate mediated inhibition of cholesterol efflux through ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 in macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanter JE, et al. Do glucose and lipids exert independent effects on atherosclerotic lesion initiation or progression to advanced plaques? Circ Res. 2007;100:769–781. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259589.34348.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang SH, et al. Spontaneous hypercholesterolemia and arterial lesions in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. Science. 1992;258:468–471. doi: 10.1126/science.1411543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plump AS, et al. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell. 1992;71:343–353. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90362-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishibashi S, et al. Massive xanthomatosis and atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed low density lipoprotein receptor-negative mice. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1885–1893. doi: 10.1172/JCI117179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hasty AH, et al. Severe hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and atherosclerosis in mice lacking both leptin and the low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37402–37408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou C, et al. Hyperglycemic Ins2AkitaLdlr−/− mice show severely elevated lipid levels and increased atherosclerosis: a model of type 1 diabetic macrovascular disease. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:1483–1493. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M014092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galkina EV, et al. Accelerated atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice heterozygous for the insulin receptor and the insulin receptor substrate-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:247–256. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.240358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Félétou M, et al. TP receptors and oxidative stress hand in hand from endothelial dysfunction to atherosclerosis. Adv Pharmacol. 2010;60:85–106. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385061-4.00004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makowski, et al. Lack of macrophage fatty-acid-binding protein aP2 protects mice deficient in apolipoprotein E against atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2001;7:699–705. doi: 10.1038/89076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kazemi MR, et al. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein expression and lipid accumulation are increased during activation of murine macrophages by toll-like receptor agonists. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1220–1224. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000159163.52632.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makowski L, et al. The fatty acid-binding protein, aP2, coordinates macrophage cholesterol trafficking and inflammatory activity. Macrophage expression of aP2 impacts peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and IkappaB kinase activities. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12888–12895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413788200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furuhashi M, Hotamisligil GS. Fatty acid-binding proteins: role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:489–503. doi: 10.1038/nrd2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babaev VR, et al. Macrophage Mal1 deficiency suppresses atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-null mice by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ-regulated genes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1283–1290. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.225839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peeters W, et al. Adipocyte fatty acid binding protein in atherosclerotic plaques is associated with local vulnerability and is predictive for the occurrence of adverse cardiovascular events. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1758–1768. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agardh HE, et al. Expression of fatty acid-binding protein 4/aP2 is correlated with plaque instability in carotid atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 2011;269:200–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furuhashi M, et al. Serum fatty acid-binding protein 4 is a predictor of cardiovascular events in end-stage renal disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furuhashi M, et al. Lipid chaperones and metabolic inflammation. Int J Inflam. 2011;2011:642612. doi: 10.4061/2011/642612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis P, et al. Lack of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase-1 accelerates atherosclerosis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2007;115:2178–2187. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torzewski M, et al. Deficiency of glutathione peroxidase-1 accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:850–857. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000258809.47285.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramasamy R, Goldberg IJ. Aldose reductase and cardiovascular diseases, creating human-like diabetic complications in an experimental model. Circ Res. 2010;106:1449–1458. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vikramadithyan RK, et al. Human aldose reductase expression accelerates diabetic atherosclerosis in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2434–2443. doi: 10.1172/JCI24819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vedantham S, et al. Human aldose reductase expression accelerates atherosclerosis in diabetic apolipoprotein E−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1805–1813. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schoonjans K, et al. Acyl-CoA synthetase mRNA expression is controlled by fibric-acid derivatives, feeding and liver proliferation. Eur J Biochem. 1993;216:615–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin G, et al. Coordinate regulation of the expression of the fatty acid transport protein and acyl-CoA synthetase genes by PPARalpha and PPARgamma activators. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28210–28217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Golej DL, et al. Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4 modulates prostaglandin E2 release from human arterial smooth muscle cells. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:782–793. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M013292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson CO, et al. Common variation in fatty acid genes and resuscitation from sudden cardiac arrest. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012 Jun 1; doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961912. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Furuhashi M, et al. Treatment of diabetes and atherosclerosis by inhibiting fatty-acid-binding protein aP2. Nature. 2007;447:959–965. doi: 10.1038/nature05844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leuschner F, et al. Therapeutic siRNA silencing in inflammatory monocytes in mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]