Abstract

Drosophila S2 cells and mammalian CHO-K1 cells were used to investigate the requirements for HSV-1 cell fusion. Infection assays indicated S2 cells were not permissive for HSV-1. HVEM and nectin-1 mediated cell fusion between CHO-K1 cells and S2 cells when either CHO-K1 or S2 cells were used as target cells. Interestingly, PILRα did not mediate fusion between CHO-K1 or S2 cells due to a glycosylation defect of PILRα and gB in S2 cells. Fusion activity was not detected for any receptor tested when S2 cells were used both as target cells and effector cells indicating S2 cells may lack a key cellular factor present in mammalian cells that is required for cell fusion. Thus, insect cells may provide a novel tool to study the interaction of HSV-1 glycoproteins and cellular factors required for fusion, as well as a means to identify unknown cellular factors required for HSV replication.

Keywords: HSV-1, Drosophila S2 cells, CHO-K1 cells, fusion activity

INTRODUCTION

Most people encounter herpes simplex virus (HSV) during their lifetime. HSV infection causes a variety of diseases including recurrent mucocutaneous lesions, keratitis, and, in rare cases, meningitis or encephalitis (Roizman, 1993). HSV utilizes multiple glycoproteins on the surface of the virion and multiple cell surface receptors to enter target cells (Connolly et al., 2011). The HSV entry process and virus-induced cell fusion requires four glycoproteins: B (gB), D (gD), H (gH) and L (gL). Receptors for gB, gD, and the gH/gL complex have been identified. Herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM) (Montgomery et al., 1996), nectin-1 (Cocchi et al., 1998; Geraghty et al., 1998), nectin-2 (Lopez et al., 2000; Warner et al., 1998), and modified heparan sulfate (Shukla et al., 1999; Shukla and Spear, 2001) all bind to gD. HVEM is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family (Ware, 2008). Nectin-1 and nectin-2 are cell adhesion molecules that belong to the immunoglobulin superfamily and are widely expressed by a variety of cell types, including epithelial cells and neurons (Takai et al., 2008). Modified heparan sulfate generated by particular 3-O-sulfotransferases can also serve as a gD-binding entry receptor (Shukla and Spear, 2001). Three gB receptors have been recently identified. The paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor alpha (PILRα) (Satoh et al., 2008) is expressed on cells of the immune system and even in neurons (Fournier et al., 2000; Satoh et al., 2008; Shiratori et al., 2004). PILRα promotes entry by fusion at the plasma membrane instead of by acidic endocytosis, as mediated by nectin-1 or HVEM when expressed in CHO-K1 cells (Arii et al., 2009). Myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) (Arii et al., 2010) is a cell-surface molecule that is preferentially expressed in neural tissues (Liu et al., 2002; McGee et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2002), and non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA (NMHC-IIA) (Arii et al., 2010) is expressed in a wide variety of cultured cells and in vivo (Golomb et al., 2004; Vicente-Manzanares et al., 2009).

The HSV-1 entry and fusion machinery have been extensively studied; however, many questions about HSV entry and fusion remain. For example, it is not clear whether all HSV-1 receptors have been identified and of those that have been identified, which are most important. In particular, if multiple HSV glycoprotein interactions are required for the most efficient entry, cell lines used for the screening of HSV receptors may already express HSV receptors that hinder identification of the new receptors. In addition, little is known if the receptors work synergistically or independently. Finally, different cells and tissues within humans may express different receptors complicating the determination of which are most important for infection and pathogenesis. This type of difference has become readily apparent in the study of the importance of HVEM in experimental corneal or vaginal infection of HVEM knockout mice. In these experiments, HVEM is very important for infection and pathogenesis in corneal infection, but has little importance in vaginal infection (Karaba et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2007). To develop an experimental means to address these unresolved questions, we chose to establish a novel system in Drosophila S2 cells, which are evolutionarily distant from mammalian cells used in prior experiments. S2 cells have been used for studying Listeria monocytogenes (Cheng and Portnoy, 2003), Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Luce-Fedrow et al., 2008), and Chlamydia (Elwell and Engel, 2005). Several viruses have been shown to infect S2 cells and these characteristics have been used for studying the RNAi response of West Nile virus (Chotkowski et al., 2008), regulation of viral transcription and replication of Vesicular stomatitis virus (VZV) (Blondel et al., 1988), and the discovery of host factors of dengue virus (Sessions et al., 2009). However, there are no studies using S2 cells to study HSV-1 virus entry and fusion.

In the current studies, we report that S2 cells can be used as a tool to study HSV cell fusion. We also found that an HSV gD receptor was all that was required in target cells for the efficient fusion of the S2 cells with CHO-K1 cells expressing HSV-1 glycoproteins. Interestingly, we found that PILRα and gB expressed in S2 cells did not function for HSV-1 fusion due to alterations in glycosylation of gB and PILRα.

RESULTS

S2 cells are not susceptible to HSV-1

We first tested whether HSV-1 F could replicate in S2 cells comparably to Vero cells. For these experiments, S2 and Vero cells were infected for 1 hour at 37°C then washed (upper Fig. 1A) or not washed with citric acid (lower Fig. 1A). At 24 hpi, infected cell lysates were collected and analyzed by western blot for the presence of capsid protein VP5 (Fig.1A). While VP5 expression was detected in infected Vero cells, S2 cells failed to express detectable VP5 after 24 hours. To test S2 cells for susceptibility to HSV-1 entry, we infected S2 cells or Vero cells with a dual-fluorescent HSV-1 F virus containing a red-fluorescent capsid (mRFP1-VP26) and a green-fluorescent envelope protein (GFP-gB). Conceptually, virions that fuse their envelopes with a target cell membrane will lose green fluorescence but retain the red fluorescent capsid, while virions that do not fuse with a host cell will be positive for both red capsid and green envelope fluorescence. Equal numbers of freshly-collected (unfrozen) virions were added to S2 cells or Vero cells, which were observed at 2 hpi for virion fluorescence composition. We found that 70% of virions in contact with S2 cells colocalized with a green-fluorescent envelope, contrasting to only 33% of virions in contact to Vero cells (Fig. 1, B and C). Notably, the 70% envelope-capsid colocalization in S2 cells was statistically different from the 84% envelope-capsid colocalization observed in input virions that fell onto cell-free areas of the coverslip. This was likely caused by reduced envelope fluorescence detection due to round S2 cells being present in the light path when compared to a cell-free imaging area. Monofluorescent (mRFP1-VP26 only) HSV-1 F colocalized with a nonspecific green background in S2 cells less than 5% of the time (data not shown). While capsids could easily be detected at the nuclear rim of infected Vero cells at 2 hpi, this localization was never apparent in S2 cells. S2 cells had lower binding density on average when compared to Vero cells indicating that HSV-1 virions may not bind as efficiently to S2 cells when compared to Vero cells. However, this reduced binding does not account for the differences in the proportion of HSV-1 virions fusing with the target cells as shown in Fig. 1B. Together, these experiments suggested untransfected S2 cells were neither susceptible nor permissive for HSV-1 F infection.

Fig. 1. Infection of Vero cells and S2 cells by HSV-1.

A. VP5 was expressed in infected Vero cells but not S2 cells. Vero cells and S2 cells were infected with HSV-1 F for 1 hour at 37°C, then treated with Citric acid (PH 3.0), the cells were washed 3 times with cold PBSA, incubated in SDM (with 1% serum) or DMEV (DME with 1% serum) medium for 24 hours for western. Western blot analysis was performed using a VP5 MAb at 1:5000 dilution and a goat anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary at a 1:2000 dilution.

B. Virion de-envelopment assay. S2 cells or Vero cells grown on #1.5 coverslips were infected with equivalent numbers of fluorescent HSV-1 F virions and incubated for 2 hours before imaging. Viral particles were assayed for the presence of an envelope by observing whether GFP-gB co-localized with a red mRFP1-VP26 capsid. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for three independent experiments. ** p <0.01, *** p<0.001.

C–N. Representative micrographs of the virion deenvelopment assay. Input virions that have fallen on coverglass demonstrating colalization of the red and green markers (C–F), infected Vero cells (G–J), and infected S2 cells (K–N) are shown. Arrowheads indicate capsid locations. Gray values of all green and all red images are calibrated equivalently. Length scale bar = 10 um.

Expression of HSV-1 glycoproteins and HSV-1 receptors in S2 cells

HSV-1 gB, gD, gH and gL were cloned into pAc5.1/v5-HisA (Invitrogen) after replacing the native signal sequences with the BiP signal sequence cloned from pMT/BiP/ V5- His A (Invitrogen). The native signal sequence for gB (amino acids 1–30), gD (amino acids 1–25), gH (amino acids 1–18) and gL (amino acids 1–19) were removed. FLAG-PILRα (Fan and Longnecker, 2010), FLAG-HVEM (kindly provided by Dr. Carl F. Ware) and FLAG-nectin-1 (Spear lab, originally from Dr. Y. Takai (Osaka University Medical School, Osaka, Japan) were cloned into pAc5.1/v5-His A, each with a FLAG peptide located at the N-terminus of the relevant protein. All plasmids made for this study were sequenced at the Northwestern University Genomics core facility.

Flow cytometry was used to verify the cell surface expression of the FLAG-tagged receptors and glycoproteins in S2 cells. Since gH requires gL as a chaperone, these two proteins were co-transfected. For all of the expression constructs, expression of the proteins of interest was readily detected on the cell surface for all transfections, while control staining (grey, secondary antibody only) showed no non-specific reactivity (Fig. 2A). Expression of the relevant glycoproteins and receptors was confirmed by western blotting total cell lysates to confirm expression of each at the appropriate molecular weight (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Expression of FLAG-tagged receptors and glycoproteins in S2 cells.

A, Cell surface expression by Flow Cytometry: S2 cells were transfected in a 6-well plate with FLAG-PILRα, FLAG-HVEM, FLAG-nectin-1, gB, gD, gH and gL. The transfectants were stained with monoclonal antibody anti-FLAG-M2 (Invitrogen) for FLAG-PILRα, FLAG-HVEM and FLAG-nectin-1 (F means FLAG-tagged glycoprotein), and rabbit polyclonal antibody R74 for gB, R45 for gD, and R137 for gH/ gL. Histograms show fluorescence intensity measured (x axis) and percentage of expressed cells (y axis). The grey represents cells stained with secondary antibody only. B, Expression of receptors and glycoproteins in S2 cells by western blotting. S2 cells were transfected in a 6-well plate with FLAG-tagged PILR , FLAG-HVEM, FLAG-nectin-1 (F means FLAG-tagged glycoprotein) and empty vector (upper panel), or gB, gD, gH, gL and empty vector (lower panel). For FLAG-tagged proteins, S2 cells were lysed and were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with rabbit anti-FLAG antibody followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP. For glycoproteins, S2 cells were lysed and were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with rabbit anti-gB (R74), gD (R45), gH (R87) and gL (R137) antibody followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP. All proteins tested migrated at the expected molecular weights.

S2 cells can function as effectors or targets for HSV-induced fusion

Fusion experiments were performed by transfecting target CHO-K1 or S2 cells with a plasmid encoding luciferase under a T7 promoter and either empty vector, PILRα (pQF003), HVEM (pBEC10) nectin-1(pBG38). Alternatively, target S2 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding luciferase under a T7 promoter and either empty vector (pAC 5.1v/V5 HisA), FLAG-PILRα (pQF64), FLAG-HVEM (pQF66) and FLAG-nectin-1(pQF67). Effector CHO-K1 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding T7 RNA polymerase and gB, gD, gH and gL. Effector S2 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding T7 RNA polymerase (pQF19) and gB (pQF72), gD (pQF73), gH (pQF74) and gL (pQF75). Effector and target cells were mixed and luciferase activity was recorded as a measure of cell-cell fusion.

The luciferase relative light unit (RLU) intensity varied from experiment to experiment, and as a result, RLU was normalized as a percentage of a control for each experiment. The background RLU intensity of S2 and CHO-K1 cells not expressing a fusion receptor was usually between 200–600, while RLU intensity of CHO-K1 cells and CHO-K1 cells not expressing a fusion receptor was between 3590 to 75990, as expected based on our earlier data, indicating there is a relatively weak endogenous receptor expressed in CHO-K1 cells (Fan et al., 2009). The lower RLU between S2 and CHO-K1 cells when no known receptor expressed may indicate an absence of an endogenous receptor in S2 cells. When nectin-1 was expressed in S2 or CHO-K1 cells, the RLU between CHO-K1 cells and S2 cells was 2000 to 100,000. Nectin-1 mediated fusion between CHO-K1 cells is usually higher with a RLU around 200,000.

The background luciferase activity recorded when target cells were transfected with empty vector was subtracted from each experiment and for each fusion assay target cells expressing nectin-1 was set at 100% (Fig. 3A–C). When CHO-K1 cells were used as target cells and effectors, as expected both the gB receptor (PILRα) and the gD receptors (HVEM and nectin-1) mediated robust fusion. Fusion mediated by PILRα was significantly lower about 20% of the levels mediated by HVEM and nectin-1 agreeing with our previously reported results (Fan et al., 2012; Fan et al., 2009). Using combinations of the various receptors did not significantly increase fusion activity (data not shown). When target CHO-K1 cells were added to effector S2 cells, HVEM and nectin-1 could mediate fusion with HVEM fusion activity approximately 38% of nectin-1 (Fig. 3B). The luciferase activity mediated by PILRα was usually lower than that of vector control, so the average value for PILRα was negative. When target S2 cells were added to effector CHO-K1 cells, fusion mediated by HVEM was approximately 57% of the level of nectin-1 (Fig. 3C). PILRα did not mediate fusion when S2 cells were used either as target cells or effectors cells (Fig. 4Fig. 3B–C), which is different from the CHO-K1 and CHO-K1 fusion observed in Fig. 3A. Again, for S2 and CHO-K1 fusion, using combinations of the various receptors did not significantly increase fusion activity (data not shown). Cell fusion activity between S2 and S2 cells was not detected by a luciferase assay (Fig. 3D). For the S2-S2 cell fusion, the background luciferase activity when target cells were transfected with empty vector was not subtracted and the activity was set as 100%. Fusion of target CHO-K1 cells and effector S2 cells was used as a positive control. Luciferase activity mediated by PILRα, HVEM, or nectin-1 was even lower than that of the vector control for the S2-S2 fusion experiments (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. Cell fusion activity between S2 and CHO-K1 cells mediated by HSV-1 gD and gB receptors.

Target CHO-K1 cells were transfected with pCDNA3 (empty vector), HVEM, or nectin-1, along with a reporter plasmid expressing luciferase under control of the T7 promoter. The transfected cells were replated with effector CHO-K1 cells transfected with gB, gD, gH and gL, along with plasmids expressing T7 polymerase (A), or effector S2 cells transfected with gB (pQF72), gD (pQF73), gH (pQF74) and gL (pQF75), along with plasmids expressing T7 polymerase (B). When target S2 cells were transfected with pAc5.1/v5-His A (empty vector), FLAG- PILRα, FLAG-HVEM, or FLAG-nectin-1, along with a reporter plasmid expressing luciferase under control of the T7 promoter. The transfected cells were replated with effector CHO-K1 cells transfected with gB, gD, gH and gL, along with plasmids expressing T7 polymerase (C), or effector S2 cells transfected with gB (pQF72), gD (pQF73), gH (pQF74) and gL (pQF75), along with plasmids expressing T7 polymerase, fusion results from target CHO cells and insect effector cells mediated by nectin-1 was used as positive control (D), Cell fusion activity mediated by each receptor was presented as percentage of nectin-1 (A, B and C) or percentage of vector background (D). Fusion mediated by nectin-1 (A, B and C) was set as 100% after subtracting the data from the empty vector. Each bar shows the mean and standard deviation of at least three independent determinations. v: empty vector.

Fig. 4. Absence of the CHO-K1 endogenous receptor in S2 cells.

Target CHO-K1 cells were transfected with pCDNA3 (empty vector) along with a reporter plasmid expressing luciferase under control of the T7 promoter. The transfected cells were replated with effector CHO-K1 cells (A) or S2 cells (B) transfected with different combination of glycoproteins, along with plasmids expressing T7 polymerase Fig. 5. Target S2 cells were transfected with pAc5.1/v5-His A (empty vector) along with a reporter plasmid expressing luciferase under control of the T7 promoter. The transfected cells were replated with effector S2 cells transfected with different combination of glycoproteins, along with plasmids expressing T7 polymerase (C). Cell fusion activity mediated by endogenous receptor was presented as percentage of vector background (100%). Each bar shows the mean and standard deviation of at least three independent determinations. v: empty vector

The CHO-K1 endogenous receptor does not function in S2 and CHO-K1 cell fusion

CHO-K1 cells are resistant to the entry of many viruses like HSV, PRV, HBV and HIV because receptors for these viruses are not expressed (Xu et al., 2011) or the CHO-K1 version does not function. CHO-K1 cells are poor target cells in cell fusion assays unless transfected to express HSV gB or gD receptors. However, previous studies indicated that CHO-K1 cells express low levels of HSV entry/fusion receptors (Fan et al., 2009; Shieh et al., 1992). To test whether the CHO-K1 endogenous receptors mediate HSV fusion between CHO-K1 and S2 cells, we performed a cell fusion assay by transfecting different combinations of glycoproteins into effector cells. Target CHO-K1 or S2 cells were transfected with empty vector and a plasmid expressing firefly luciferase gene under control of the T7 promoter. The background luciferase activity recorded when target cells were transfected with empty vector was not subtracted and the activity was set as 100%. The data are presented as percentage of luciferase activity of vector control. When effector CHO-K1 cells were transfected with different combinations of glycoproteins and overlaid with CHO-K1 cells transfected with T7 luciferase, only the full set of gB, gD, gH and gL showed fusion activity higher than vector control (400% of the control) indicating the presence of a weak receptor able to trigger fusion (Fig. 4) similar to our previous results (Fan et al., 2009). However, when effector cells expressing different combinations of glycoproteins in either CHO-K1 cells or S2 cells, no combination, even the full set of gB, gD, gH and gL required for fusion, showed higher fusion activity than the vector control when overlaid with target CHO-K1 or S2 cells (Fig. 4). These results indicate that S2 cells do not express any functional fusion receptors for HSV.

The PILRα-gB interaction is blocked due to defects in glycosylation of gB and PILRα in S2 cells

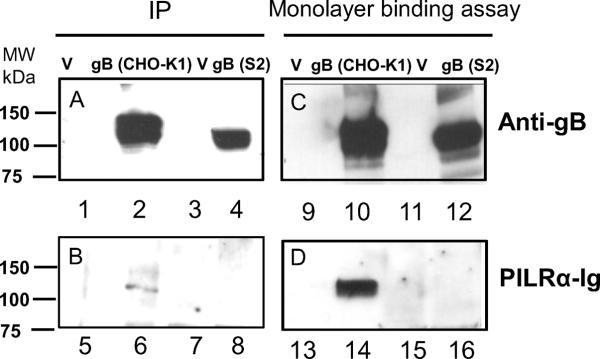

We next investigated why PILRα did not mediate fusion between S2 and CHO-K1 despite robust fusion in similar experiments with HVEM and nectin-1. We first did western blots of cell lysates from CHO-K1 cells transfected with gB (pPEP98) or PILRα (pQF22) (Fan and Longnecker, 2010), or S2 cells with gB (pQF72) or PILRα (pQF64). Interestingly, gB and PILRα from S2 transfected cells migrated more rapidly than that from CHO-K1 cells (Fig. 5A). The difference was more dramatic for PILRα (Fig. 5A compare lanes 2 and 3 with lanes 5 and 6). Next we employed neuraminidase since neuraminidase treated gB is not recognized by PILRα-Ig (Wang et al., 2009). CHO-K1 cells or S2 cells expressing gB were treated with neuraminidase and lysates from the transfected cells were probed with anti-gB or PILRα-Ig (Fig. 5B). gB was expressed in both CHO-K1 and S2 cells and neuraminidase treatment reduced the size of gB in CHO-K1 cells (Fig.4B, compare lanes 2 and 3) while neuraminidase treatment had little effect on gB when expressed in S2 cells (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 5 and 6). Neuraminidase treatment of CHO-K1 cells expressing gB abrogated the binding of PILRα-Ig to gB (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 8 and 9), however, gB was unable to bind PILRα-Ig when expressed in S2 cells with or without neuraminidase treatment (Fig. 5B, lanes 11 and 12) indicating PILRα does not bind gB when expressed in S2 cells. To verify this finding, we used CHO-K1 cells or S2 cells expressing gB that had been incubated with PILRα-Ig, washed, immunoprecipitated with anti-gB, and finally probed in western blots with anti-gB (Fig. 6A) or PILRα-Ig (Fig. 6B). PILRα-Ig immunoprecipitated with only CHO-K1 cells expressing gB but not S2 cells expressing gB (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 6 and 8), indicating PILRα-Ig did not bind to gB on S2 cells, using a monolayer binding assay which has been previously described (Fan and Longnecker, 2010). CHO-K1 cells and S2 cells expressing gB were incubated with PILRα-Ig, and the lysed proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and western blot analyses were performed by using the anti-gB (Fig. 6C) and anti-human IgG HRP (Fig. 6D), the results showed that PILRα lost binding activity to gB expressed on S2 cells (Fig. 6D, compare lanes 14 and 16). Taken together, these results indicate that altered glycosylation of gB (Fig. 5, Fig. 6) or PILRα (Fig. 5A) occurs in S2 cells resulting in the loss of binding to each other blocking fusion mediated by PILRα (Fig. 3 B–C).

Fig. 5. Mobility of gB and PILRα in S2 cells as well as Neuraminidase treatment.

A, Altered mobility of gB and PILRα in S2 cells when compared to CHO-K1 cells. S2 cells were transfected in a 6-well plate with gB (pQF72), FLAG-PILRα (pQF64), and empty vector. CHO-K1 cells were transfected in a 6-well plate with gB (pPEP98), FLAG-PILRα (pQF22) (Fan and Longnecker, 2010), and empty vector. Cells transfected with PILRα were lysed and were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with rabbit anti-FLAG antibody followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP. Cells transfected with gB were lysed and were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with rabbit anti-gB (R74) followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP. B, Neuraminidase treatment of gB blocks interaction with PILRα. CHO-K1 cells and S2 cells seeded in six-well plates were transfected with emptor vector or gB (pPEP98 or pQF72). 24 h later, cells were treated with neuraminidase (+Neu) or untreated (−Neu) for 3 h, lysed, resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-gB (R74) and PILRa-Ig, respectively followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP and anti-human IgG (H&L) (HRP).

Fig. 6. PILRα-Ig did not bind to gB in S2 cells by immunoprecipitation and monolayer binding assay.

CHO-K1 cells and S2 cells seeded in six-well plates were transfected with empty vector or gB (pPEP98 or pQF72). 24 h post transfection, cells were incubated with PILRα-Ig, lysed, and incubated with rabbit anti-gB. Immune complexe were captured with protein G, and eluted. The eluted proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-gB (R74) (A) and PILRα-Ig (B), respectively followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP and anti-human IgG (H&L) (HRP). For monolayer binding assay, after 24 h of incubation, cells expressing empty vector and gB in six-well plates were incubated with PILR-Ig supernatants and washed, and intact cells were lysed and resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-gB (R74) (C) and PILRa-Ig (D), respectively followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP and anti-human IgG (H&L) (HRP).

DISCUSSION

Herpesviruses engage multiple receptors during viral entry. To date, four receptors have been identified for gD (HVEM, nectin-1, nectin-2, and specific sites in heparan sulfate generated by certain isoforms of 3-O-sulfotransferases), and three receptors have been identified for gB (PILRα, MAG and NMHC-II). Any of these cell surface molecules can bind to HSV encoded glycoproteins and participate in viral entry. Besides an entry receptor, there are also binding receptors for the HSV. For example, gB can bind to heparin and heparan sulfate and may contribute, along with gC (Herold et al., 1991), to the binding of HSV to cell surface heparan sulfate (Shukla and Spear, 2001). HSV gB and gC can also bind to DC-SIGN, which serves as a binding receptor for the infection of dendritic cells (de Jong et al., 2008). gB can bind to cell surfaces independently of heparan sulfate and can block virus entry (Bender et al., 2005) indicating there may exist an unidentified heparan sulfate-like receptor. Finally, a gH/gL receptor (αVβ3 integrin) has been identified for HSV (Connolly et al., 2011; Parry et al., 2005). In contrast to gD and gB receptors that seem to largely function as binding and fusion receptors, the interaction of integrins with gH/gL appears to dictate the route HSV uses to enter cells. Specifically, the interaction of gH/gL and αVβ3 route HSV to an entry pathway dependent on lipid rafts, dynamin 2, and acidic endosomes (Gianni and Campadelli-Fiume, 2012; Gianni et al., 2010). Mutated Integrin motifs did not affectvirus infection indicating the role of integrin in gH/gL binding, but not in triggering fusion (Galdiero et al., 1997). Most experiments investigating HSV entry have utilized mammalian cells that may express multiple HSV entry and binding receptors, making it difficult to study the entry process, and in particular to determine the relative importance of each for HSV infection. Krummenacher et.al. tested the receptor tropism of HSV clinical isolates and found all were able to use HVEM as well as nectin-1 in cell culture (Krummenacher et al., 2004). Interestingly, in our recent studies, we found that α-herpesviruses herpes B virus and CeHV-2 use nectin-1, but not HVEM and PILRα, as fusion receptors (Fan et al., 2012).

We directly tested the entry of HSV-1 virus into Vero cells and S2 cells by infecting these cells with HSV-1 F, leading us to conclude that S2 cells are not susceptible to the HSV-1 infection (Fig. 1 A–C). To further investigate receptor usage for HSV-1, we used S2 and CHO-K1 cells for cell fusion assays. From our experiments, we conclude that HVEM and nectin-1 can function independently and mediate HSV-1 fusion independently of any additional identified receptors (Fig. 3) although we cannot specifically exclude the possibility that there is S2 factor or factors that may contribute to fusion mediated by HVEM and nectin-1. In addition, fusion mediated by the gD receptors HVEM and nectin-1 does not require the gB receptor PILRα, since PILRα did not mediate fusion between S2 and CHO-K1 cells due to a defect in glycosylation of gB and PILRα when gB or PILRα was expressed in S2 cells (Fig. 5). This is in line with previous results demonstrating that the association of HSV-1 gB with PILRα depends on O-glycosylation sites within gB (Wang et al., 2009).

One interesting and somewhat unexpected result from our current studies is the absence of fusion when S2 cells are used as effectors and CHO-K1 cells are used as targets when no known fusion receptors were expressed (Fig. 4). We would have expected that fusion would occur using the CHO-K1 endogenous receptor, similar to when CHO-K1 cells are used as both effectors and targets. The absence of fusion may be due to the absence of an additional unknown factor that is important for fusion and may work in cis or trans, since fusion is readily observed when a gD receptor is expressed in either S2 or CHO-K1 cells and used as effectors of the opposite cell type. In addition, the absence of fusion may also be a result of host cell specific modification of HSV-1 glycoproteins such as glycosylation that reduces the functionality of the glycoprotein resulting in fusion that is not detected in our current assay because the levels are lower than those observed when a similar experiment is done with CHO-K1 cells. Future studies should focus on understanding this observation to determine if a novel receptor or modification exists that might be an important determinant for fusion. Based on the results when CHO-K1 cells are used as effectors and S2 cells as targets, we conclude that S2 cells do not express any functional receptors for HSV-1 fusion. This is compatible with our search of the Drosophila melanogaster genome for homologous proteins. As might be expected, the level of identity for NMHC-IIA was the greatest of any of the HSV entry receptors. Within a region of 1920 amino acids, there was an identity of approximately 50%. For the other gB and gD receptors, the level of identity varied from no significant matches for PILRα to limited regions in which identity of between 20%–30% was observed, but unlikely is functionally significant. This is not surprising since the gB receptor MAG and the gD receptors Nectin-1 and HVEM perform specialized functions in the more evolutionary complex mammalian systems when compare to Drosophila melanogaster. Even though we excluded the possibility of studying roles of gB or the gB receptor PILRα between S2 cells and CHO cells fusion because of a glycosylation defect, the use of S2 cells for study of HSV membrane fusion may by an ideal tool to the study the interaction of gD with cellular receptors and may provide a means to identify novel HSV entry receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1 - ATCC) cells, African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells and Drosophila Schneider 2 (S2) Cells (Invitrogen) were used in this study. The CHO-K1 cell line and its derivatives were grown in Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Vero cells were grown and maintained in DMEM/F-12 phenol red free media supplemented with 10% FBS. The Drosophila S2 cells were grown in Schneider's Drosophila Medium (SDM) (Invitrogen) containing 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 25°C. Fluorescent HSV-1 viruses GS2822 (HSV-1 F + mRFP1-VP26) and GS2843 (HSV-1 F + mRFP1-VP26 + GFP-gB), both gifts of Gregory Smith, were isolated and passaged as described previously (Antinone et al., 2010).

Plasmids

Plasmids expressing HSV-1(KOS) gB (pPEP98), gD (pPEP99), gH (pPEP100) and gL (pPEP101) were previously described (Pertel et al., 2001) as were plasmids expressing human nectin-1, pBG38 (Geraghty et al., 1998), HVEM, pBEC10 (Montgomery et al., 1996) and PILRα (pQF003) (Fan et al., 2009). New plasmids generated for this study are shown in Table 1. The insect expression vector, pAc5.1/v5-His A, was obtained from Invitrogen.

Table 1.

Plasmids generated for this study

| Construct | Protein | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| pQF19 | T7 polymerase | T7 RNA polymerase was cut with SmaI and MscI and a fragment containing T7 RNA polymerase was ligated into EcoRV sites of pAC 5.1v/V5 HisA (Invitrogen). |

| pQF64 | FLAG-PILRα | pQF22 (PILRα) was cut with XmnI and XbaI and a fragment containing Flag-PILRα was ligated into EcoRV and XbaI sites of pAC 5.1v/V5 HisA. |

| pQF66 | FLAG-HVEM | FLAG-HVEM was cut with EcoRI and BamHI and a fragment containing FLAG-HVEM was ligated into EcoRI and BamHI sites of pAC 5.1v/V5 HisA |

| pQF67 | FLAG-nectin-1 | FLAG-nectin-1 was cut with XhoI and a fragment containing nectin-1 was ligated into XhoI sites of pAC 5.1v/V5 HisA. |

| pQF72 | HSV-1 gB | The PCR product of the HSV-1 gB ORF(without amino acid 1–30) from pPEP98 was cloned into pAC 5.1v/V5 HisA after adding the BiP signal sequence to gB. |

| pQF73 | HSV1-gD | The PCR product of the HSV-1 gB ORF(without amino acid 1–25) from pPEP99 was cloned into pAC 5.1v/V5 HisA after adding the BiP signal sequence to gD. |

| pQF74 | HSV1-gH | The PCR product of the HSV-1 gB ORF(without amino acid 1–18) from pPEP100 was cloned into pAC 5.1v/V5 HisA after adding the BiP signal sequence to gH. |

| pQF75 | HSV1-gL | The PCR product of the HSV-1 gB ORF(without amino acid 1–19) from pPEP101 was cloned into pAC 5.1v/V5 HisA after adding the BiP signal sequence to gL. |

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was used to test the cell surface expression of genes encoding glycoproteins or receptors cloned into pAc5.1/v5-His A (Invitrogen), an insect vector designed for S2 cells. S2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates 1 day before and were sub-confluent when transfected (80–90%). 1 h prior to transfection, the overnight medium was aspirated and 2 mL of serum-free SDM was added to each well. 1500 ng of empty vector (pAc5.1/v5-His A), or plasmid expressing gB (pQF72), gD (pQF73), gH (pQF74)/gL (pQF75), PILRα (pQF64), HVEM (pQF66), nectin-1 (pQF67) was diluted in 100 μl serum-free SDM, vortexed briefly and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Simultaneously, 8 μl Cellfectin II (Invitrogen) was diluted in 100 μl serum-free SDM, vortexed briefly and incubated at room temperature for about 20 min. The diluted DNA was then combined with the diluted Cellfectin II and mixed gently and incubated for 10 minutes before adding the DNA-lipid mixture drop wise onto the cells. The transfection medium was aspirated and replaced with SDM 4 h later and incubated overnight prior to FACS. Cells in each well (about 1 million) were stained with specific antibodies, rabbit polyclonal antibody R74 for gB, R45 for gD, R137 for gH/gL (both R45 and R137 were kindly provided by Dr. Gary H. Cohen and Dr. Roselyn J. Eisenberg) and the monoclonal antibody anti-FLAG-M2 (Invitrogen) for FLAG-tagged PILRα, HVEM and nectin-1. The data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Control staining was performed with secondary antibodies only.

Western blots

Western blots were performed to monitor expression of HSV-1 glycoproteins and relevant receptors in S2 whole cell lysates. S2 cells seeded in 6-well plates were transfected as described above. The cells were detached 24 h after transfection using a pipette, washed with PBS, and lysed with 200 μl of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO3, 1% Nonidet P-40) containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 4–20% gels after boiling for 5 min under reducing conditions. Western blot analyses were performed using the rabbit polyclonal antibody R74 for gB at 1:10000, R45 for gD at 1:10000, R87 for gH, R137 gL at 1:10000, and the rabbit anti-FLAG (Sigma, F7425) at a 1:1000 dilution for proteins of the FLAG-tagged receptors for 1 h at room temperature. Anti-rabbit secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and ECL™ Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare) were used.

S2 permissivity assay

For detecting VP5 in S2 cells, Vero cells and S2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates separately 1 day before infection. The Vero cells and S2 cells were infected with HSV-1 F at MOI 0, 1 and 10, respectively, incubated for 1 hour at 37°C, treated or untreated with citric acid (PH 3.0) for 1 min, washed 3 times with cold PBSA, incubated in SDM (with 1% serum) or DMEV (DME with 1% serum) medium for 24 hours and then lysed for western blotting as described above. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 4–20% gels after boiling for 5 min under reducing conditions. Western blot analysis was performed using VP5 MAb (EastCoast Bio) at 1:5,000 dilution and the goat anti-mouse (Santa Cruz) at a 1:2000 dilution.

S2 susceptibility assay

Input virus was purified on the day of the experiment to reduce damage to fluorophore fluorescence caused by freezing. These fluorescent HSV-1 viruses were purified from Vero cells infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 plaque forming units per ml (pfu/ml). During infection, Vero cells were incubated in phenol red-free F12/DMEM media supplemented with 2% bovine growth serum. At 48 hpi, supernatants from four 10 cm culture dishes were collected and cleared of cell debris by centrifugation at 3000 g for 10 minutes. Virions were pelleted out of the cleared supernatant through a 10% Nycodenz cushion (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY) at 38500 g for one hour. The resulting viral pellet was initially resuspended in 100 μl of PBS and further diluted in phenol-red free media for infection of S2 and Vero cells.

S2 cells or Vero cells grown on #1.5 coverslips cells were infected with virions purified as described above with equal volumes of purified virus. Infected cells were incubated for 2 hours before imaging. Images were acquired with an inverted wide-field Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U microscope using automated fluorescence filter wheels (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA), a 60X 1.4 numerical aperture oil objective (Nikon), and a CoolSnap HQ2 camera (Photometrics). The Metamorph software package was used for image acquisition and processing (Molecular Devices, Downington, PA). Sequential transmitted light, green, and red images were acquired at 100 ms, 4 s, and 1 s, respectively. Micrographs of infected S2 or Vero cells were observed for red particles (capsids) that were consistent with single point-sources of fluorescence, and more than 10 pixels away from another fluorescence point-source. The “linescan” tool was used to observe histograms of pixel intensities through red and green images of virons. If there was a green fluorescent local maxima (>500 gray levels above background) within a five pixel diameter of a red fluorescent local maxima, the particle was counted as enveloped. Three independent experiments were performed and quantified.

Cell fusion assay

Either CHO-K1 cells or S2 cells were used as effector or target cells. When CHO-K1 cells were used as effector cells and S2 cells as target cells, CHO-K1 cells and S2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates separately 1 day before transfection. The effector CHO-K1 cells were transfected with 400 ng each of plasmids expressing T7 RNA polymerase, gB, gD, gH and gL; and 5 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The target S2 cells overnight medium was replaced by 2 mL of serum free SDM, transfected with 400 ng of a plasmid carrying the firefly luciferase gene under control of the T7 promoter, 2.4 μg of empty vector (pAc5.1/v5-His A) or 800 ng of each plasmid expressing either human PILRα (pQF64), HVEM (pQF66), nectin-1 (pQF67), and 8 μL of cellfectin II (Invitrogen). When CHO-K1 cells were used as target and S2 cells as effector, the target CHO-K1 cells were transfected with 400 ng of a plasmid carrying the firefly luciferase gene under control of the T7 promoter, 2.4 μg of empty vector (pCDNA3) or 800 ng of each plasmid expressing either human PILRα (pQF003), HVEM (pBEC10), nectin-1 (pBG38), and 5 μL of Lipofectamine 2000. The effector S2 cells were transfected with 400 ng each of plasmids expressing T7 RNA polymerase (pQF19), gB (pQF72), gD (pQF73), gH (pQF74), and gL (pQF75); and 8 μl of cellfectin II. Four h after transfection, the transfection medium in S2 cells were aspirated and 2 mL of SDM was added to each well. Six h after transfection, the CHO-K1 cells were detached with versene (0.2 g EDTA/liter in PBS), and suspended in 1.5 ml of F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. S2 cells in 2 ml SDM were suspended with a pipette. The cells were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and were replated in 6-well plates with F12 medium and SDM ration as 1:2. When S2 cells were used as target cells, the mixed S2 and CHO-K1 cells were incubated at 37°C for 42 h. When CHO-K1 cells were used as target cells, the mixed CHO-K1 and S2 cells were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. For S2 and S2 cells fusion, the target S2 cells and effector S2 cells were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and replated in to 6-well plates, and the cells were incubated at 25 °C for 48 h. For S2-CHO-K1 cell fusion and S2-S2 cell fusion, the medium was aspirated and the cells were lysed with 350 μl lysis buffer (Promega). The lysed cells (100 μl) were added 100 μl of luciferase substrate. The fusion between CHO-K1 cells was done as described previously (Fan et al., 2009). Luciferase activity was quantitated by a luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) using a Wallac-Victor luminometer (Perkin Elmer).

Endogenous receptor cell fusion assay

Target CHO cells were transfected with 1.5 μg of pCDNA3 (empty vector) along with 400 ng of a plasmid carrying the firefly luciferase gene under control of the T7 promoter. Target S2 cells were transfected with only 1.5 μg of pAc5.1/v5-HisA (empty vector) along with a reporter plasmid expressing luciferase under control of the T7 promoter. The transfected target cells were replated with effector CHO cells or S2 cells transfected with 400 ng of each the plasmid expressing T7 RNA polymerase, gB and gD (or pQF72 and pQF73), gD and gH (or pQF73 and pQF74), gH and gL (or pQF74 and pQF75), gB, gD and gH (or pQF72, pQF73 and pQF74), or gB, gD, gH and gL (or pQF72, pQF73, pQF74, and pQF75), along with 400 ng of plasmid expressing T7 polymerase (empty vectors were added to make the total transfection DNA of each treatment to 2.0 μg, if less than this amount), and 5 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 or 8 μl of Cellfectin II. Fusion was done as described in Cell fusion assay in this Materials and Methods.

PILRα and gB interaction, neuraminidase treatment, immunoprecipitation, and monolayer binding assay

Neuraminidase treatment was done as previously described (Teuton and Brandt, 2007; Wang et al., 2009) to test the interaction of PILRα with gB. CHO-K1 cells and S2 cells were seeded in six-well plates and transfected with 1.5 μg of emptor vector (pCAGGS or pAC5.1/v5-HisA) or gB (pPEP98 or pQF72), 24 h later transfection, 0.04 U (4 μl) of neuraminidase Arthrobacter ureafaciens (1 U/ml, Roche) were added to the medium and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Western blot analyses were performed on cell lysates by using the rabbit polyclonal anti-gB (R74) at a 1:10,000 dilution and PILRα-Ig at 70 ng/ml respectively, anti-rabbit secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and anti-human IgG (H&L) (HRP) (ab6759; Abcam) at a 1:2,000 dilution and ECL™ Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare) were used. Immunoprecipitation and monolayer binding assay (Fan and Longnecker, 2010) was also used to investigate the interaction of PILRα (pQF003) with gB expressed in CHO-K1 and S2 cells. CHO-K1 cells seeded in six-well plates were transfected with 1.5 μg of empty vector (pCAGGS) or a plasmid expressing gB (pPEP98). S2 cells seeded in six-well plates were transfected with 1.5 μg of empty vector (pAC5.1/v5-HisA) or a plasmid expressing gB (pQF72). For immunoprecipitations, after 24 h of incubation, the cells were washed once with cold PBS, detached with versene, washed twice with cold PBS and then incubated with PILRα-Ig (70 ng/ml) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were washed 4 times with cold PBS and lysed with 200 μl of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO3, 1% Nonidet P-40) containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), then incubated with R74 for 1 h at 4°C, washed, pulled down with protein G (Thermo Scientific), washed with cold lysis buffer four times, and the proteins eluted. The eluted proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 4 to 20% gels after boiling for 5 min under non-reducing conditions. Western blot analyses were performed by using the rabbit polyclonal anti-gB (R74) at a 1:10,000 dilution and PILRα-Ig at 70 ng/ml respectively, anti-rabbit secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and anti-human IgG (H&L) (HRP) (ab6759; Abcam) at a 1:2,000 dilution and ECL™ Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare) were used. For monolayer binding assay, after 24 h of transfection, the cells were washed twice with cold PBS, incubated with normalized PILR-Ig at about 70 ng/ml for 1 h at 4°C, washed with cold PBS four times, and lysed with 200 ul of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO3, 1% Nonidet P-40) containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 4 to 20% gels after boiling for 5 min under non-reducing conditions. Western blot analyses were performed by using the rabbit polyclonal anti-gB (R74) at a 1:10,000 dilution and anti-human IgG (H&L) (HRP) (ab6759; Abcam) at a 1:2,000 dilution. Anti-rabbit secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and anti-human IgG (H&L) (HRP) (ab6759; Abcam) at a 1:2,000 dilution and ECL™ Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare) were used.

Highlights of S2 paper

We found that Drosophila S2 cells were not permissive for HSV-1.

HSV-1 gD receptors (HVEM and nectin-1) mediated cell fusion between CHO-K1 cells and S2 cells.

HSV-1 gB receptor PILRα did not mediate fusion between CHO-K1 or S2 cells.

S2 cells may lack a key cellular factor present in mammalian cells that is required for cell fusion.

ACKNOWLEGDEMENTS

We appreciate the generous gifts from Gary H. Cohen and Roselyn J. Eisenberg for R45 and R137 antibodies, from Dr. Carl F. Ware for the plasmid of FLAG-HVEM, from Gregory A. Smith for fluorescent viruses vGS2843 and vGS2822, and from Dr. Y. Takai for plasmid of FLAG-nectin-1. We thank N. Susmarski for timely and excellent technical assistance and members of the Longnecker Laboratory for their help in these studies. Traditional sequencing services were performed at the Northwestern University Genomics Core Facility. RL is the Dan and Bertha Spear Research Professor in Microbiology – Immunology. This work was supported by NIH grants CA021776 and AI067048 to RL. KPB was supported by the training program in Immunology and Molecular Pathogenesis from the National Institutes of Health (T32AI07476).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Antinone SE, Zaichick SV, Smith GA. Resolving the assembly state of herpes simplex virus during axon transport by live-cell imaging. J Virol. 2010;84:13019–13030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01296-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arii J, Goto H, Suenaga T, Oyama M, Kozuka-Hata H, Imai T, Minowa A, Akashi H, Arase H, Kawaoka Y, Kawaguchi Y. Non-muscle myosin IIA is a functional entry receptor for herpes simplex virus-1. Nature. 2010;467:859–862. doi: 10.1038/nature09420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arii J, Uema M, Morimoto T, Sagara H, Akashi H, Ono E, Arase H, Kawaguchi Y. Entry of herpes simplex virus 1 and other alphaherpesviruses via the paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor alpha. J Virol. 2009;83:4520–4527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02601-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender FC, Whitbeck JC, Lou H, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. Herpes Simplex Virus Glycoprotein B Binds to Cell Surfaces Independently of Heparan Sulfate and Blocks Virus Entry. J. Virol. 2005;79:11588–11597. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11588-11597.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondel D, Petitjean AM, Dezelee S, Wyers F. Vesicular stomatitis virus in Drosophila melanogaster cells: regulation of viral transcription and replication. J Virol. 1988;62:277–284. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.277-284.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng LW, Portnoy DA. Drosophila S2 cells: an alternative infection model for Listeria monocytogenes. Cellular microbiology. 2003;5:875–885. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chotkowski HL, Ciota AT, Jia Y, Puig-Basagoiti F, Kramer LD, Shi PY, Glaser RL. West Nile virus infection of Drosophila melanogaster induces a protective RNAi response. Virology. 2008;377:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocchi F, Menotti L, Mirandola P, Lopez M, Campadelli-Fiume G. The ectodomain of a novel member of the immunoglobulin subfamily related to the poliovirus receptor has the attributes of a bona fide receptor for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in human cells. J. Virol. 1998;72:9992–10002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9992-10002.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SA, Jackson JO, Jardetzky TS, Longnecker R. Fusing structure and function: a structural view of the herpesvirus entry machinery. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2011;9:369–381. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong MA, de Witte L, Bolmstedt A, van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TB. Dendritic cells mediate herpes simplex virus infection and transmission through the C-type lectin DC-SIGN. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:2398–2409. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/003129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwell C, Engel JN. Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells: a model system to study Chlamydia interaction with host cells. Cellular microbiology. 2005;7:725–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q, Amen M, Harden M, Severini A, Griffiths A, Longnecker R. Herpes B virus utilizes human nectin-1 but not HVEM nor PILRalpha for cell-cell fusion and virus entry. J Virol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00041-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q, Lin E, Satoh T, Arase H, Spear PG. Differential effects on cell fusion activity of mutations in herpes simplex virus 1 glycoprotein B (gB) dependent on whether a gD receptor or a gB receptor is overexpressed. J Virol. 2009;83:7384–7390. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00087-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q, Longnecker R. The Ig-like v-type domain of paired Ig-like type 2 receptor alpha is critical for herpes simplex virus type 1-mediated membrane fusion. J Virol. 2010;84:8664–8672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01039-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier N, Chalus L, Durand I, Garcia E, Pin JJ, Churakova T, Patel S, Zlot C, Gorman D, Zurawski S, Abrams J, Bates EE, Garrone P. FDF03, a novel inhibitory receptor of the immunoglobulin superfamily, is expressed by human dendritic and myeloid cells. J. Immunol. 2000;165:1197–1209. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdiero M, Whiteley A, Bruun B, Bell S, Minson T, Browne H. Site-directed and linker insertion mutagenesis of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H. J.Virol. 1997;71:2163–2170. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2163-2170.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty RJ, Krummenacher C, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Spear PG. Entry of alphaherpesviruses mediated by poliovirus receptor-related protein 1 and poliovirus receptor. Science. 1998;280:1618–1620. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni T, Campadelli-Fiume G. alphaVbeta3-integrin relocalizes nectin1 and routes herpes simplex virus to lipid rafts. J. Virol. 2012;86:2850–2855. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06689-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni T, Gatta V, Campadelli-Fiume G. {alpha}V{beta}3-integrin routes herpes simplex virus to an entry pathway dependent on cholesterol-rich lipid rafts and dynamin2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:22260–22265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014923108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golomb E, Ma X, Jana SS, Preston YA, Kawamoto S, Shoham NG, Goldin E, Conti MA, Sellers JR, Adelstein RS. Identification and characterization of nonmuscle myosin II-C, a new member of the myosin II family. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2800–2808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold BC, WuDunn D, Soltys N, Spear PG. Glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus type 1 plays a principal role in the adsorption of virus to cells and in infectivity. J.Virol. 1991;65:1090–1098. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1090-1098.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaba AH, Kopp SJ, Longnecker R. Herpesvirus entry mediator and nectin-1 mediate herpes simplex virus 1 infection of the murine cornea. J. Virol. 2011;85:10041–10047. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05445-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krummenacher C, Baribaud F, Ponce de Leon M, Baribaud I, Whitbeck JC, Xu R, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. Comparative usage of herpes virus entry mediator A and nectin-1 by laboratory strains and clinical isolates of herpes simplex virus. Virology. 2004;322:286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu BP, Fournier A, GrandPre T, Strittmatter SM. Myelin-associated glycoprotein as a functional ligand for the Nogo-66 receptor. Science. 2002;297:1190–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.1073031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez M, Cocchi F, Menotti L, Avitabile E, Dubreuil P, Campadelli-Fiume G. Nectin2D (PRR2D or HveB) and nectin2G are low-efficiency mediators for entry of herpes simplex virus mutants carrying the Leu25Pro substitution in glycoprotein D. J. Virol. 2000;74:1267–1274. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1267-1274.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce-Fedrow A, Von Ohlen T, Boyle D, Ganta RR, Chapes SK. Use of Drosophila S2 cells as a model for studying Ehrlichia chaffeensis infections. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2008;74:1886–1891. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02467-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee AW, Yang Y, Fischer QS, Daw NW, Strittmatter SM. Experience-driven plasticity of visual cortex limited by myelin and Nogo receptor. Science. 2005;309:2222–2226. doi: 10.1126/science.1114362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RI, Warner MS, Lum BJ, Spear PG. Herpes simplex virus-1 entry into cells mediated by a novel member of the TNF/NGF receptor family. Cell. 1996;87:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81363-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry C, Bell S, Minson T, Browne H. Herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H binds to {alpha}v{beta}3 integrins. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:7–10. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertel P, Fridberg A, Parish ML, Spear PG. Cell fusion induced by herpes simplex virus glycoproteins gB, gD, and gH-gL requires a gD receptor but not necessarily heparan sulfate. Virology. 2001;279:313–324. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roizman B. The family herpesviridae: A brief introduction. In: Roizman B, Whitley RJ, Lopez C, editors. The Human Herpesviruses. Raven Press; New York: 1993. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T, Arii J, Suenaga T, Wang J, Kogure A, Uehori J, Arase N, Shiratori I, Tanaka S, Kawaguchi Y, Spear PG, Lanier LL, Arase H. PILRalpha is a herpes simplex virus-1 entry coreceptor that associates with glycoprotein B. Cell. 2008;132:935–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions OM, Barrows NJ, Souza-Neto JA, Robinson TJ, Hershey CL, Rodgers MA, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G, Yang PL, Pearson JL, Garcia-Blanco MA. Discovery of insect and human dengue virus host factors. Nature. 2009;458:1047–1050. doi: 10.1038/nature07967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh M-T, WuDunn D, Montgomery RI, Esko JD, Spear PG. Cell surface receptors for herpes simplex virus are heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J.Cell Biol. 1992;116:1273–1281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.5.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiratori I, Ogasawara K, Saito T, Lanier LL, Arase H. Activation of natural killer cells and dendritic cells upon recognition of a novel CD99-like ligand by paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor. J Exp Med. 2004;199:525–533. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla D, Liu J, Blaiklock P, Shworak NW, Bai X, Esko JD, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Rosenberg RD, Spear PG. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell. 1999;99:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla D, Spear PG. Herpesviruses and heparan sulfate: an intimate relationship in aid of viral entry. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:503–510. doi: 10.1172/JCI13799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai Y, Miyoshi J, Ikeda W, Ogita H. Nectins and nectin-like moleecules: Roles in contact inhibition of cell movement and proliferation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:603–615. doi: 10.1038/nrm2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JM, Lin E, Susmarski N, Yoon M, Zago A, Ware CF, Pfeffer K, Miyoshi J, Takai Y, Spear PG. Alternative entry receptors for herpes simplex virus and their roles in disease. Cell Host & Microbe. 2007;2:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuton JR, Brandt CR. Sialic acid on herpes simplex virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins is required for efficient infection of cells. J. Virol. 2007;81:3731–3739. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02250-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Manzanares M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Horwitz AR. Non-muscle myosin II takes centre stage in cell adhesion and migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:778–790. doi: 10.1038/nrm2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Fan Q, Satoh T, Arii J, Lanier LL, Spear PG, Kawaguchi Y, Arase H. Binding of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B (gB) to paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor alpha depends on specific sialylated O-linked glycans on gB. J Virol. 2009;83:13042–13045. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00792-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KC, Koprivica V, Kim JA, Sivasankaran R, Guo Y, Neve RL, He Z. Oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein is a Nogo receptor ligand that inhibits neurite outgrowth. Nature. 2002;417:941–944. doi: 10.1038/nature00867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware CF. Targeting lymphocyte activation through the lymphotoxin and LIGHT pathways. Immunol. Rev. 2008;223:186–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner MS, Geraghty RJ, Martinez WM, Montgomery RI, Whitbeck JC, Xu R, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Spear PG. A cell surface protein with herpesvirus entry activity (HveB) confers susceptibility to infection by mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2 and pseudorabies virus. Virology. 1998;246:179–189. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Nagarajan H, Lewis NE, Pan S, Cai Z, Liu X, Chen W, Xie M, Wang W, Hammond S, Andersen MR, Neff N, Passarelli B, Koh W, Fan HC, Wang J, Gui Y, Lee KH, Betenbaugh MJ, Quake SR, Famili I, Palsson BO. The genomic sequence of the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cell line. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:735–741. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]