Abstract

A considerable number of studies have focused on the relationship between prayer, health, and well-being. But the influence of some types of prayer (e.g., petitionary prayer) has received more attention than others. The purpose of this study is to examine an overlooked aspect of prayer: trust-based prayer beliefs. People with this orientation believe that God knows that best way to answer a prayer and He selects the best time to provide an answer. Three main findings emerge from data that were provided by a nationwide longitudinal survey of older people reveals. First, the results reveal that Conservative Protestants are more likely to endorse trust-based prayer beliefs. Second, the findings suggest that these prayer beliefs tend to be reinforced through prayer groups and informal support from fellow church members. Third, the data indicate that stronger trust-based prayer beliefs are associated with a greater sense of life satisfaction over time.

Keywords: prayer beliefs, life satisfaction, denominational differences

Introduction

During the past several decades researchers have made considerable headway in the study of prayer. Initially, a good deal of this research focused solely on how often prayers are offered (e.g., Levin, Taylor, and Chatters 1994). However, as this literature began to develop, it quickly became evident that prayer is a vast multidimensional phenomenon in its own right. For example, some investigators identified different types of prayer, such as ritual, conversational, petitionary, and meditative prayer (Poloma and Gallup 1991). Others focused on the social context in which prayer takes place, such as prayer groups, prayers during worship services, and prayers that are offered in private (Krause 2012). And yet other researchers assessed the role played by prayer in the process of coping with stressful life events (Pargament 1997). In addition to this, theories about how prayers may affect health began to emerge in the literature, as well (Baesler, Lindvall, and Lauricella 2011; Breslin and Lewis 2008). It is not surprising to see such great interest in prayer because research consistently demonstrates that it is the most common type of religious behavior (Stark 2008). Moreover, key religious figures have argued for over a thousand years that prayer is the very essence of religion (e.g., Evagrius, see Stewart 2008).

Even though many studies have appeared on prayer, the literature has evolved in an uneven fashion, with some dimensions of prayer (e.g., different types of prayer) receiving more attention than others. One largely overlook facet of prayer has to do with the beliefs about how prayer operates. Krause (2004) refers to these beliefs as prayer expectancies. Defined broadly, expectancies are beliefs about a future state of affairs (Olson, Roese, and Zanna 1996). Cast within the context of prayer, this means that when people pray, they often expect certain outcomes - certain responses from God. So, for example, people hold beliefs about whether prayers are answered, how quickly prayers are answered, and the ways in which prayers are answered (Krause et al. 2000). Research on expectancies reveals that if people get what they expect, they will experience a greater sense of well-being, but if expected outcomes fail to come about, then people are likely to experience psychological distress (Olson, Roese, Zanna 1996).

The purpose of the current study is to elaborate and extend research on prayer expectancies. However, before describing how this will be accomplished, it is important to delve more deeply into the nature and potential benefits of prayer expectancies.

There appears to be only one study in the literature that has examined prayer expectancies empirically. Based on insights from extensive qualitative research, Krause (2004) examined competing sets of prayer expectancies. The first had to do with how quickly prayers are answered. He reports that some people believe that prayers are answered right away. But in contrast, other individuals believe that God answers prayers when He feels it is best even though a person may not understand God’s reasons for doing so. The second set of prayer expectancies that Krause (2004) assessed involved beliefs about the way in which prayers are answered. Some individuals believe that when they pray for something, they usually get exactly what they ask for. However, other study participants found that they do not always get what they ask for, but when they take the time to think about it, they find the answer they receive is precisely what they really needed the most.

Krause (2004) maintains that both sets of prayer expectancies share a common conceptual foundation: trust in God. As theologians have discussed for some time, all people are flawed and there are significant and substantial impediments to their ability to reason clearly. For example, Cottingham (2005) recently observed that, “ … humans have a massive capacity to rationalize, deceive themselves, excuse themselves, convince themselves they are acting properly and sincerely, when their true motivations are often highly suspect” (p. 141). He goes on to argue that the only way to overcome this “impotence of reason” is with faith and trust in God. So when some people pray, they realize they are incapable of knowing what they really need and as a result, they trust in God: they trust that God will provide an answer to their prayers at the best time and they trust that only He knows the best way to answer them. Based on this reasons, Krause (2004) referred to these prayer beliefs as trust-based prayer expectancies.

Based on data from a nationwide sample of older adults (Krause et al. 2000), Krause (2004) found that older people who endorse trust-based expectancies have a stronger sense of self-worth than individuals who do not believe that prayers operate in this way. He explained these findings by arguing the probability of having prayer beliefs disconfirmed is much greater if people believe their prayers are answered right away and if they believe they typically get what they ask for. But in contrast, trust-based prayer expectancies are less likely to be invalidated because people are willing to wait for a response and they are willing to accept responses that differ from what they request initially.

The goal of the current study is to build upon the work of Krause (2004) in four potentially important ways. First, the religious landscape in America is comprised of a patchwork of many denominations that vary widely in their doctrines and beliefs. This raises the possibility that the extent to which trust-based prayer expectancies are endorsed may vary across denominations. Although there are many ways study to denominational variations in religious beliefs, the first objective in the analyses that are presented below is to see if Conservative Protestants are more likely to endorse trust-based prayer beliefs than individuals who affiliate with other denominations.1

Second, if trust-based prayer expectancies help bolster a sense of well-being, then it is important to learn more about how these prayer beliefs are maintained in the church. This issue is addressed in the analyses that follow by seeing whether these expectancies are reinforced by three different aspects of congregational life including attendance at worship services, participation in prayer groups, and informal spiritual support from fellow church members. Spiritual support refers to informal assistance that is provided by a fellow church member in order increase the religious commitment, beliefs, and behavior of the support recipient.

Third, the study by Krause (2004) focused solely on the relationship between trust-based prayer expectancies and self-esteem. However, in order to further assess the utility of this conceptual framework, it is important to see if trust-based prayer beliefs are associated with other outcomes. It is for this reason that the relationship between trust-based prayer expectancies and life satisfaction is evaluated below.

Fourth, the study by Krause (2004) was based on data that were collected at a single point in time. As a result, the relationship between trust-based expectancies and self-esteem was based on theoretical considerations alone. A more rigorous approach is taken in the analyses that follow by assessing the relationship between trust-based prayer expectancies and life satisfaction with data that have been gathered at more than one point in time.

A latent variable model was developed for the current study in order to address each of these goals. This model, and the theoretical foundation on which it is based, are presented in the next section.

Social Aspects of the Church, Prayer Expectancies, and Change in Life Satisfaction

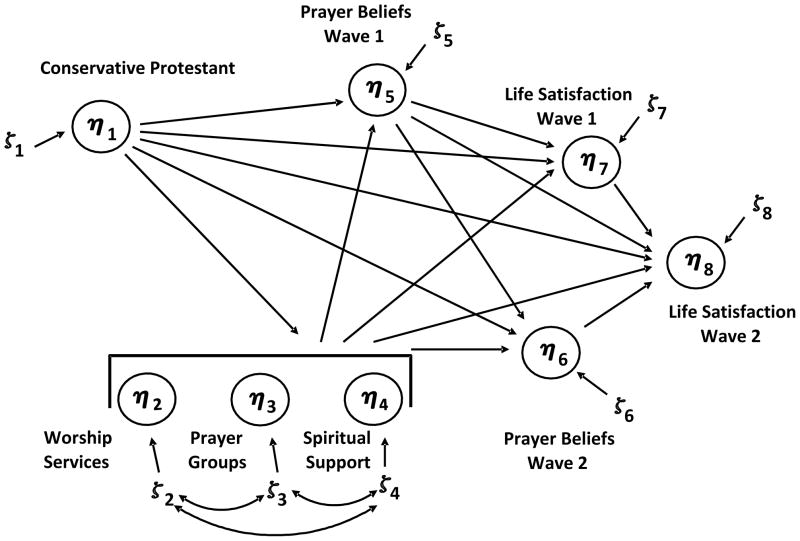

The conceptual model that is evaluated in this study is depicted in Figure 1. Two steps were taken to simplify the presentation of this conceptual scheme. First, the elements of the measurement model (i.e., the factor loadings and measurement error terms) are not depicted even though a full measurement model was estimated when this conceptual scheme was evaluated empirically. Second, the relationships among the constructs in Figure 1 were evaluated after the effects of age, sex, marital status, education, and race were controlled statistically.

Figure 1.

A Conceptual Model of Prayer Expectancies and Life Satisfaction

Even though a number of relationships are specified in Figure 1, this conceptual scheme was designed to address three main issues. The first is to see if Conservative Protestants are more likely to endorse trust-based prayer beliefs than people who affiliate with other denominations. The second is to see if these prayer beliefs are transmitted through worship services, prayer group meetings, and the informal exchange of spiritual support among fellow church members. And the third goal is to see if those who endorse trust-based prayer expectancies are more likely to experience a greater sense of life satisfaction over time. The theoretical underpinnings of these issues are provided below.

Conservative Protestants and Trust-Based Prayer Expectancies

Identifying the nature of the prayer beliefs that Conservative Protestants endorse is challenging because research on trust-based prayer expectancies is in its infancy. In fact, there do not appear to be any studies in the literature that empirically examine this issue. Some insight may be found by turning to historical literature on Conservative Protestants beliefs that deal with prayer. Focusing on these historical records is especially helpful because, as the discussion that is provided below will reveal, they deal with prominent figures in the early twentieth century, which is a time when many of the older participants in the current study were in their formative years. However, as the discussion provided below will also reveal, these historical sources provide conflicting views of the nature of the prayer beliefs that have traditionally been endorsed by Conservative Protestants.

Ostrander (1996) provides a detailed overview of the historical evolution of Conservative Protestant views on answered prayer. He begins by pointing out that George Mueller, “....set the pattern for an number of answered prayer narratives in American fundamentalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries” (p.71). Mueller ran a large orphanage and he often encountered significant difficult finding sufficient funds to keep this institution open. However, he found that every time he prayed for money, it was received. In fact, Mueller’s prayers were answered so routinely that he kept a lengthy record of how God had provided exactly what he asked for. Orstrander (1996) reports that many Conservative Protestants seized on this notion that God always provides exactly what they ask for. He relates a number of accounts of how prayer became used for even the most trivial matters, such as finding lost house keys. Orstrander (1996) goes on to maintain that these prayer beliefs eventually came to be viewed as divine proof of the spiritual mettle of Conservative Protestant prayer agents. Simply put, they knew God favored them because He always provided exactly what they asked for. So if Ostrander (1996) historical account is valid, and Conservative Protestants believe they always get exactly what they ask for, then compared to people in other denominations, Conservative Protestants should be less likely to endorse trust-based prayer beliefs.

However, the issues discussed by Orstrander (1996) do not represent the only views on prayer that may be found in the Conservative Protestant theological literature. Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield was one of the leading evangelical theologians in the early twentieth century. In his volume on the extensive writings of Warfield, Zaspel (2010) reports that Warfield firmly believed that, “… faith as trust, reliance, dependence - is the only possible approach to God” (p. 446). Zaspel (2010) goes on to report that Warfield believed that people should be completely subordinated to God in prayer and that they should surrender to Him and become utterly dependent upon Him when they pray. If Conservative Protestants define faith purely in terms of trust and if they believe they are utterly dependent upon God when they pray, then they should be more likely than people in other denominations to endorse trust-based prayer expectancies. One of the primary objectives of the current study is to see which of these competing views on prayer beliefs is more likely to be endorsed by the older Conservative Protestants in the current study.

Conservative Protestant Affiliation and the Transmission of Prayer Beliefs

A basic premise in the current study is that religious beliefs are transmitted through social processes that take place in the church. Focusing on these social factors should provide greater insight into the way in which prayer beliefs are maintained in religious institutions. Support for the notion that religious beliefs are transmitted through social processes in the church may be found in the classic work of Berger (1967), who argues that religious world views, “.... are socially constructed and social maintained. Their continuing reality, both objective.... and subjective .... depends upon specific social processes, namely those processes that ongoingly reconstruct and maintain the particular worlds in question” (p. 45). Simply put, religious beliefs are socially constructed during interaction fellow church members. An effort is made in the current study to build on Berger’s (1967) insights in a potentially important way.

Although social processes in the church may shape religious world views, these processes may take place in not one but several different social settings in the church. So if the goal is to understand how religious beliefs arise, then it is important to take multiple church contexts into account. Three potentially important social contexts are examined in the current study.

The first social setting in which prayer beliefs may be reinforced is attendance at worship services. The important role that worship services play in instilling and reinforcing religious beliefs was emphasized by Stark and Finke (2000). Referring to religious beliefs and teachings as “religious explanations”, these investigators argue that, “Confidence in religious explanations increases to the extent that people participate in religious rituals” (Stark and Finke 2000, p.107).

Prayer groups are the second social context in the church that may shape religious beliefs. Evidence of this may be found in Wuthnow’s (1994) research with people who attend Bible study and prayer groups. He argues that developing a deeper faith is hard work and that participation in these groups may be especially helpful in this respect. However, one aspect of his findings are especially relevant for the current study. Wuthnow (1994) reports that over half the participants in his study reported that having their prayers answered was an important consequence of participating in Bible study and prayer groups. Since the ways in which prayers are answered is an important part of trust-based prayer expectancies, it makes sense to look to prayer groups as a potentially important mechanism for transmitting these beliefs.

The third social context in the church that may shape religious beliefs involves informal spiritual support. There are a number ways in which fellow church members may provide spiritual support. For example, they may share their own religious experiences with a coreligionist, they may show them how to apply religious beliefs in daily life, and they may help them find solutions to their problems in the Bible (Krause 2008). Simply viewing the ways in which spiritual support may be exchanged makes it easy to see why it may play a role in shaping beliefs about how prayer operates.

Focusing on worship services, prayer groups, and informal spiritual support is important because research indicates that Conservative Protestants are more likely to avail themselves of these social aspects of congregational life than people in other faith traditions. Evidence of this may be found in research by Barna (2002; 2006). Based on an array of nationwide surveys, he reports that compared to people who affiliate with other denominations, Evangelicals attend church more often, attend Bible study groups more frequently, and they are more likely to believe it is important to share their religious beliefs with others. Although Barna (2002; 2006) makes no effort to show why this is so, it may reflect denominational differences in the extent to which Bible study and prayer groups are provided by a congregation. Simply put, there may be better opportunity structures for participating in these groups in Conservative Protestant congregations.

Trust-Based Prayer Expectancies and Life Satisfaction

According to research that was presented earlier, people may experience psychological distress when expectancies are disconfirmed. Since trust-based prayer expectancies are more difficult to disconfirm, those who hold these beliefs should enjoy better mental health. However, there are at least two other ways to flesh out the theoretical underpinnings of the relationship between trust-based prayer expectancies and life satisfaction. The first has to do with trust. When people say they believe that only God knows how to best answer prayers and when they say they believe that God knows the best time to answer prayers then they in essence expressing their trust in Him. The emphasis on trust is important because an extensive body of research suggests that people who are more trusting of others tend to enjoy better physical and better mental health (e.g. Nummela et al., 2009). Although a number of mechanisms may link trust with health, some researchers argue that the beneficial effects may attributed to the fact that people who are trusting do not worry as often as individuals who are less trusting (Schneider et al., 2011). Yet another potential mechanism is identified by Sharp (2010). He argues that praying to God is a form of informal social support that helps quell negative emotions in a number of ways. For example, praying to God may make troubling situations seem less threatening. It seems reasonable to extend these insights by arguing that perceived threats are more likely to be diminished if people trust God and believe He will do what is best for them.

The second way in which trust-based prayer expectancies may promote better mental health has to do with the construct of control. When people believe that God knows the best way and the best time to answer a prayer, they are turning control of certain aspects of their lives over to Him. This is important because a growing literature suggests that people who believe that God is helping them control their lives (i.e., those with a stronger sense of God-mediated control) are more likely to enjoy better physical and better mental health (Krause, 2005; 2010).

An important feature of the model depicted in Figure 1 is associated with the fact that the relationship between trust-based prayer expectancies and life satisfaction is evaluated with data that have been gathered at more than one point in time. As Menard (1991) points out, there are a number of different ways to analyze this type of survey data. In fact, he identifies four “pure” longitudinal models (Menard 1991, p.59). The model depicted in Figure 1 is among them. In this type of conceptual scheme, change in the dependent variable is expressed in terms of change in the independent variable. The logic of this specification is straightforward: if the level of one variable (i.e., life satisfaction) depends upon the level of a second variable (i.e., prayer beliefs), then if the second variable changes, the first variable must also change. Menard (1991) goes on to point out that many researcher express their hypotheses in terms of this model but unknowingly test a different specification. The model depicted in Figure 1 is especially useful because it addresses one (but not all) of the criteria for establishing causality by assessing whether change in the independent variable is associated with change in the outcome over time (Bradley & Schaefer, 1998).

Methods

Sample

The data for this study come from the first two waves of interviews in an ongoing nationwide survey of older whites and older African Americans. The study population was defined as all household residents who were black or white, non-institutionalized, English-speaking, and at least 66 years of age. Geographically, the study population was restricted to all eligible persons residing in the coterminous United States (i.e., residents of Alaska and Hawaii were excluded). Finally, the study population was restricted to currently practicing Christians, individuals who were Christian in the past but no longer practice any religion, and people who have not affiliated with any faith tradition at any point in their lifetime. This study was designed to explore a range of issues involving religion and health. As a result, individuals who practice a faith other than Christianity were excluded because it would be too difficult to devise a comprehensive battery of religion measures that are suitable for individuals of all faiths.

The sampling frame consisted of all eligible persons contained in the beneficiary list maintained by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). A five-step process was used to draw the sample from the CMS Files (see Krause 2002a, for a detailed discussion of these steps).

The baseline survey took place in 2001. The data collection for all waves of interviews was conducted by Harris Interactive (New York). A total of 1,500 interviews were completed, face-to-face, in the homes of the study participants. Older African Americans were over-sampled so that sufficient statistical power would be available to assess race differences in religion. As a result, the Wave 1 sample consisted of 748 older whites and 752 older African Americans. The overall response rate for the baseline survey was 62%.

The Wave 2 survey was conducted in 2004. A total of 1,024 study participants were re-interviewed successfully, 75 refused to participate, 112 could not be located, 70 were too ill to participate, 11 had moved to a nursing home, and 208 were deceased. Not counting those who had died or moved to a nursing home, the re-interview rate for the Wave 2 survey was 80%.

Spiritual support plays a key role in the model that is depicted in Figure 1. When this study was being designed, the members of the research team felt that it did not make sense to ask study participants about spiritual support they receive in church if they either don’t attend church at all or if they only go to church rarely. Consequently, questions on spiritual support were not administered to older study participants who indicated they go to church services no more than once or twice a year (N = 342). These study participants were deleted from the analyses. In addition, some study participants were also excluded from the analyses because they reported that they either never pray or they believe their prayers are never answered. After deleting these study participants from the sample, the analyses presented below are based on the responses of 658 older study participants.

The full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) procedure was used to impute missing values (i.e., item non-response) in the data. Simulation studies suggest that the FIML procedure is preferable to listwise deletion because listwise deletion may produce biased estimates (Enders 2001). Moreover, as Graham, Olchowski, and Gilreath (2007) report, FIML is equivalent to more time consuming procedures for dealing with item nonresponse, such as multiple imputation.

Preliminary analyses reveal that the average age of the participants in this sample at the baseline survey was 73.9 years (SD = 5.8 years), approximately 35% were older men, 53.5% were married, 45.0% were white, and the average number of years of schooling was 11.7 (SD = 3.3).

Measures

Table 1 contains the measures of the core constructs that appear in Figure 1. The procedures that were used to code the measures are provided in the footnotes of this table.

Table 1.

Core Study Measures

1. Conservative Protestantsa

|

2. Church Attendanceb

|

3. Prayer Groupsb

|

4. Spiritual Supportc

|

5. Trust-Based Prayer Expectanciesd

|

| 6. Life Satisfaction |

This item is scored in the following manner (coding in parenthesis): Conservative Protestants (1); affiliates with another denomination (0).

These items are scored in the following manner: several times a week (9); every week (8); nearly every week (7); 2–3 times a month (6); about once a month (5); several times a year (4); about once or twice a year (3); less than once a year (2); never (1).

These items were scored in the following manner: very often (4); fairly often (3); once in a while (2); never (1).

These items were scored in the following manner: strongly agree (4); agree (3); disagree (2); strongly disagree (1).

This item was scored in the following manner: completely satisfied (5); very satisfied (4); somewhat satisfied (3); not very satisfied (2); not satisfied at all (1).

Conservative Protestants

A detailed series of questions were administered at the beginning of the baseline survey to identify the religious affiliation of the study participants. Once the specific denominational affiliation had been identified, the coding scheme provided by Smith (1990) was used to determine if a study participant affiliates with a Conservative Protestants denomination. No attempt was made to identify Charismatic Catholics. So it is for this reason that the term “Conservative Protestants” is used throughout this study. A list of Conservative Protestant denominations is included in the Appendix. Preliminary evidence revealed that 58.6% were Conservative Protestants.2 A binary variable was created which contrasts Conservative Protestants with older people who affiliate with all other denominations taken together.

Church Attendance

The measure of church attendance, which comes from the Wave 1 survey, reflects how often older study participants attended worship services in the past year. A high score represents more frequent attendance. The mean level of church attendance is 7.2 (SD = 1.9).

Prayer Groups

A single item, which was administered at Wave 1, asked study participants how often they participated in prayer groups during the year prior to the survey. It is important to note that respondents were asked to count only those prayer group meetings that were not part of regular worship services. A high score on this indicator denotes more frequent attendance at prayer groups. The mean is 3.3 (SD = 2.9).

Spiritual Support

Spiritual support was assessed with five indicators that were developed by Krause (2002b). These items were administered at Wave 1. In the process of answering these questions study participants were instructed not to include spiritual support they may have received at worship services, Bible study group meetings, or prayer group meetings. Phrasing the question in this manner makes it easier to distinguish between the influence of worship services, prayer groups, and informal spiritual support. A high score on this measure denotes study participants who receive spiritual support more often from fellow church members. The mean of the composite that was created by summing these indicators is 12.4 (SD = 4.0).

Trust-Based Prayer Expectancies

Identical items were used to assess trust-based prayer expectancies at the Wave 1 and Wave 2 interviews. Two indicators were administered each time. The first asks study participants if learning to wait for God to answer prayers is an important part of their faith while the second asks whether God does not always give them exactly what they ask for. A high score of these indicators reflects stronger trust-based prayer beliefs. The mean at Wave 1 is 6.7 (SD = .99) and the mean at Wave 2 is 6.9 (SD = 1.0). The correlation between the two prayer expectancy items at Wave 1 is .481 (p < .001) and the correlation between the two items at Wave 2 is .644 (p < .001).

Life Satisfaction

Identical indicators were also used to measure life satisfaction during the Wave 1 and Wave 2 interviews. Three items were administered each time. A high score denotes greater life satisfaction. The mean at Wave 1 is 10.0 (SD = 1.7) and the mean at Wave 2 is 9.9 (SD = 1.6).

Demographic Control Variables

Recall that the relationships among the constructs in Figure 1 were estimated after the effects of age, sex, marital status, education, and race were controlled statistically. Age and education are scored continuously in year while sex (1 = men; 0 = women), marital status (1 = married; 0 = otherwise), and race (1 = white; 0 = black) are coded in a binary format.

Results

The findings from this study are presented below in five sections. First, as discussed above, the FIML procedure was used to handle item non-response. However, imputation methods were not used to deal with the loss of study subjects over time (i.e., listwise deletion was used in this instance). Therefore, some preliminary analyses were conducted to see if sample attrition over time occurred in a non-random manner. The findings from these analyses are presented in the first section. Next, issues involving the estimation of the study model are provided in section two. Following this, data on the reliability of the multiple-item constructs is presented in section three. The substantive findings are reviewed in section four. Finally, some supplementary analyses that have not been discussed up to this point are provided in section five.

Sample Attrition Analysis

As the discussion of the sampling procedures reveals, some older people who were interviewed at Wave 1 did not participate in the Wave 2 survey. The loss of subjects over time may bias study findings if it occurs in a non-random manner. Although it is difficult to conclusively determine the extent of this problem, some preliminary insight may be obtained by seeing if select data from the Wave 1 survey is associated with study participation status at Wave 2. The following procedure was used to address this issue. First, a nominal-level variable containing three categories was created to represent older adults who participated in both the Wave 1 and Wave 2 surveys, older people who were alive but did not participate at Wave 2, and older individuals who died during the course of the follow-up period. Then, using multinomial logistic regression, this categorical outcome was regressed on the following Wave 1 measures: age, sex, education, marital status, race, church attendance, attendance in Bible study groups, attendance in prayer groups, spiritual support, and the Wave 1 measure of life satisfaction. The category representing older people who remained in the study served as the reference group. Evidence of potential bias would be found if any statistically significant findings emerge from this analysis.

The results (not shown here) reveal that the loss of study participants over time did not occur in a random manner. However, the pattern of non-random attrition was not substantial. More specifically, the data suggest that compared to people who remained in the study, those who died tended to be older (b = .074; p < .001; odds ratio = 1.077). But none of the other Wave 1 variables were significantly associated with the follow-up status outcome.

The findings further indicate that compared to those who remained in the study, respondents who dropped out of the study but were presumed to be alive were less likely to be married (b = −.599; p < .05; odds ratio = .549) and they did not attend church as often (b = −.165; p < .05; odds ratio = .848). But once again, significant findings did not emerge with respect to the other Wave 1 study measures.

Clearly, even though the loss of subjects over time did not occur in an entirely random manner, the evidence is not substantial. Moreover, two additional points should be kept in mind when these findings are being taken into consideration. First, the data suggest that sample attrition was influenced by age, marital status, and church attendance. However, as Graham (2009) points out, because age, marital status, and church attendance are included in the study model, any potential bias that is associated with these constructs is likely to be minimal. Second, researchers are beginning to question the assumption that non-response necessarily creates non-response bias (Groves, 2006; Holbrook, Krosnick, & Pfent, 2008). However, until this issue has been resolved conclusively, the potential influence of nonrandom subject attrition should be kept in mind as the substantive findings from this study are examined.

Model Estimation Issues

The model depicted in Figure 1 was evaluated with the maximum likelihood estimator in Version 8.80 of the LISREL statistical software program (du Toit and du Toit 2001). Use of this estimator is based on the assumption that the observed indicators have a multivariate normal distribution. Preliminary tests (not shown here) revealed that this assumption had been violated in the current study. Although there are a number of ways to deal with departures from multivariate normality, the straightforward approach that is discussed by du Toit and du Toit (2001) was followed here. These investigators report that this problem can be handled by converting the raw scores of the observed indicators to normal scores prior to estimating the model (du Toit and du Toit 2001, p.143). Based on these insights, the analyses presented below are based on observed indicators that have been normalized.

Trust-based prayer expectancies and life satisfaction were assessed at two points in time. Consequently, two issues involving the measurement of these constructs must be addressed so that the model with the best fit to the data can be identified. The first has to do with seeing whether the measurement error terms for identical indicators of prayer expectancies and life satisfaction are correlated over time. Preliminary tests (not shown here) reveal that the measurement error terms are significantly correlated over time (a table containing the results of these findings is available from the author). The second issue has to do with assessing factorial invariance over time (Bollen 1989). Tests for factorial invariance involve determining whether the elements in the measurement model (i.e., the factor loadings and measurement error terms) are invariant (i.e., do not change) over time. Preliminary tests (not shown here) indicate that the factor loadings are invariant over time while the measurement error terms are not invariant over time. Although it would have been better to find that all of the elements in the measurement model are invariant, Reise, Widaman, and Pugh (1993) argue that achieving even partial invariance is acceptable, and that meaningful interpretations can be made when examining the relationship between constructs like prayer expectancies and life satisfaction over time.

Because the FIML procedure was used to deal with item nonresponse, the LISREL software program provides only two goodness-of-fit measures. The fist is the full information maximum likelihood chi-square (314.194 with 159 df, p < .001). Unfortunately, this statistic is not very informative because chi-square values tend to be highly significant when a sample is large, as it is in the current study. However, the second goodness-of-fit measure is more useful - the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The RMSEA value for the model in Figure 1 is .038. As Kelloway (1998) reports, values below .05 indicate a very good fit of the model to the data.

Reliability Estimates for the Multiple Item Study Measures

Table 2 contains the factor loadings and measurement error terms that were derived from estimating the study model. These coefficients are important because they provide information about the reliability of the multiple item study measures. However, researchers have yet to reach a consensus on the cut point for determining factor loadings that are acceptable. For example, Kline (2005) suggests that items with standardized factor loadings in excess of .600 tend to have good reliability while Shevlin and Miles (1998) report that factor loadings of .500 are of “medium” magnitude. As the data in Table 2 indicate, the standardized factor loadings range from .536 to .884, suggesting that the reliability of the multiple-item constructs is acceptable.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings and Measurement Error Terms for Multiple Item Measures (N = 658)

| Construct | Factor Loadinga | Measurement Errorb |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Spiritual Support | ||

| A. Share religious experiences | .638 | .592 |

| B. Find solutions in Bible | .735 | .460 |

| C. Examples set by others | .822 | .324 |

| D. Lead better religious life | .862 | .257 |

| E. Help you know God | .870 | .243 |

| 2. Trust-Based Prayer Expectancies - Wave 1 | ||

| A. Wait for God’s answer | .751 | .437 |

| B. Only He knows what is best | .626 | .608 |

| 3. Trust-Based Prayer Expectancies - Wave 2 | ||

| A. Wait for God’s answer | .880 | .226 |

| B. Only He knows what is best | .735d | .465 |

| 4. Life Satisfaction - Wave 1 | ||

| A. These are the best years | .543 | .705 |

| B. As I look back | .687 | .528 |

| C. How satisfied are you | .700 | .510 |

| 5. Life Satisfaction - Wave 2 | ||

| A. These are the best years | .536 | .712 |

| B. As I look back | .643d | .586 |

| C. How satisfied are you | .685 | .531 |

The factor loadings are from the completely standardized solution. The first-listed item for each latent construct was fixed to 1.0 in the unstandardized solution.

Measurement error terms are from the completely standardized solution. All factor loadings and measurement error terms are significant at the .001 level

Item content is paraphrased for the purpose of identification. See Table 1 for the complete text of each indicator.

The Wave 2 factor loadings were constrained to equal the Wave 1 factor loadings in the unstandardized solution.

Although the factor loadings and measurement error terms that are associated with the observed indicators provide useful information about the reliability of each item, it would also be helpful to know something about the reliability for the multiple item scales as a whole. Fortunately, it is possible to compute these reliability estimates with a formula provided by DeShon (1998). This procedure is based on the factor loadings and measurement error terms in Table 2. Applying the formula described by DeShon (1988) to these data yields the following reliability estimates for the multiple item constructs in Figure 1: spiritual support (.895), life satisfaction (Wave 1 = .681), and life satisfaction (Wave 2 = .655).

Substantive Study Findings

The substantive findings that were derived from estimating the model in Figure 1 are provided in Table 3. Consistent with the theoretical rationale that was provided earlier, the results reveal that compared to older people who affiliate with other faith traditions, Conservative Protestants report that they attend church more often (Beta = .096; p < .05), attend prayer group meetings more frequently (Beta = .177; p < .001), and they receive more informal spiritual support from their fellow church members (Beta = .274; p < .001).

Table 3.

Prayer Beliefs and Life Satisfaction (N = 658)

| Dependent Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative Protestants | Church Attendance | Prayer Groups | Spiritual Support | Prayer Beliefs Wave 1 | Prayer Beliefs Wave 2 | Life Satisfaction Wave 1 | Life Satisfaction Wave 2 | |

| Independent Variables | ||||||||

| Age | −.113a ** (−.010)b | .049 (.016) | −.030 (−.015) | −.130** (−.014) | .011 (.001) | .006 (.001) | .019 (.002) | −.085 (−.006) |

| Sex | .010 (.011) | −.068 (−.270) | −.072 (−.442) | .013 (.017) | −.076 (−.069) | −.090* (−.096) | .034 (.033) | .021 (.019) |

| Marital Status | −.051 (−.051) | .077 (.292) | −.003 (−.016) | −.017 (−.021) | .038 (.033) | .019 (.019) | .082 (.078) | .001 (.001) |

| Education | −.100** (−.015) | .063 (.036) | .030 (.026) | −.015 (−.003) | −.104* (−.013) | −.005 (−.001) | .053 (.007) | .095 (.012) |

| Race | −.393*** (−.389) | .070 (.266) | −.047 (−.273) | −.039 (−.048) | −.096 (−.084) | −.009 (−.010) | −.059 (−.056) | −.111* (−.096) |

| Conservative Protestants | .096* (.369) | .177*** (1.046) | .274*** (.342) | .086 (.075) | .073 (.076) | −.043 (−.041) | −.114* (−.100) | |

| Church Attendance | .083 (.019) | −.011 (−.003) | .173*** (.043) | −.037 (−.008) | ||||

| Prayer Groups | .175*** (.026) | .030 (.006) | −.006 (−.001) | −.016 (−.002) | ||||

| Spiritual Support | .270*** (.190) | .142** (.117) | .150* (.115) | .107 (.075) | ||||

| Prayer Beliefs - Wave 1 | .317*** (.372) | .207*** (.225) | −.074 (−.074) | |||||

| Prayer Beliefs - Wave 2 | .263** (.223) | |||||||

| Life Satisfaction - Wave 1 | .305*** (.279) | |||||||

| Multiple R2 | .216 | .021 | .047 | .113 | .252 | .206 | .151 | .211 |

Standardized regression coefficient

Metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

= p < .05;

= p < .01;

= p < .001

The data also indicate that older adults who attend prayer group meetings more often tend to have stronger trust-based prayer beliefs (Beta = .175; p < .001). Moreover, the results reveal that older people who get more informal spiritual support also tend to have stronger trust-based prayer expectancies (Beta = .270; p < .001). An additional test (not shown in Table 3) was conducted to see if the magnitude of the relationship between spiritual support and prayer expectancies is greater than the magnitude of the relationship between attendance at prayer group meetings and trust-based prayer expectancies. The findings suggest that the effect of spiritual support is significantly larger (p < .001). In contrast to the findings involving prayer groups and spiritual support, the data further reveal that more frequent attendance at worship services is not significantly associated with stronger prayer expectancies (Beta = .083; n.s.).

The results in Table 3 also indicate that stronger trust-based prayer expectancies at Wave 1 are associated with greater life satisfaction at Wave 1 (Beta = .207; p < .01). However, the more demanding test of this relationship is found by turning to the results involving the Wave 2 measures of these constructs. These data indicate that an increase (i.e., change) in trust-based prayer expectancies is associated with an increase (i.e., change) life satisfaction (Beta = .263; p < .001) over time.

Although the findings that have been presented up to this point are consistent with the theoretical rationale that was provided earlier, the results do not appear to support the notion that Conservative Protestants are either more or less likely to endorse trust-based prayer expectancies than individuals who affiliate with other faith traditions. More specifically, the data in Table 3 indicate that the relationship between Conservative Protestants affiliation and trust-based prayer beliefs at Wave 1 (Beta = .086; n.s.) and Wave 2 (Beta = .073; n.s.) are not statistically significant.

Fortunately, it is possible to clarify this issue by turning to the indirect and total effects that operate through the study model. An example will help clarify these terms. As shown in Figure 1, Conservative Protestants are hypothesized to get more spiritual support from their fellow church members, and older people who get more spiritual support from their coreligionists are in turn more likely to endorse trust-based prayer expectancies. Put in a more technical way, this example specifies that Conservative Protestants affiliation affects prayer expectancies indirectly through spiritual support. When the direct and indirect effects are summed, the resulting total effects provide a better vantage point for assessing the relationship between fundamentalism and prayer expectancies.

Further analysis (not shown in Table 3) indicate that the indirect effects of Conservative Protestants religious affiliation on life satisfaction at Wave 1 that operate through the study model are statistically significant (Beta = .113; < .001). When these indirect effects are added to the direct effect that is shown in Table 3 (Beta = .086), the resulting total effect (Beta = .199; p < .001) suggests that compared to older people who affiliate with other faith traditions, Conservative Protestants are more likely to endorse trust-based prayer expectancies. The same is true with respect to the total effect of Conservative Protestants affiliation on trust-based prayer beliefs at Wave 2. More specifically, the data suggest that compared to individuals from other faith traditions, Conservative Protestants are more likely to experience an increase in trust-based prayer expectancies over time (Total effect = .180; p < .001; not shown in Table 3).

Supplementary Analysis

The findings that have emerged up to this point suggest that the genesis of trust-based prayer beliefs may be traced, in part, to religious affiliation (i.e., Conservative Protestant beliefs) and key elements of congregational life (i.e., attending prayer group meetings and receiving spiritual support). However, the data further indicate that religious affiliation and these elements of congregational life are influenced by a more proximal factor: race. Krause (2004) reports that compared to older whites, older African Americans tend to have stronger trust-based prayer expectancies. However, he did not show how this relationship may arise. Turning to the results in the current study provides significant insight into this issue.

The data in Table 3 create the impression that there are no race differences in trust-based prayer expectancies at Wave 1 (Beta = −.096; n.s.). However, when the indirect effects of race that operate through the model are taken into account (Beta = −.091; p < .001; not shown in Table 3), the resulting total effect (Beta = −.187; p < .001; not shown in Table 3) reveals that the prayer expectancies of older whites are not as strong as those of older blacks.

A similar pattern of findings emerge when the relationship between race and change in prayer expectancies is examined. The data in Table 3 suggest that race is not associated with prayer expectancies at Wave 2 (Beta = −.009; n.s.). But when the indirect effects that operate through the model are taken into account (Beta = −.113; p < .001; not shown in Table 3), the resulting total effect (Beta = −.122; p < .001; not shown in Table 3) suggests that compared to older blacks, the trust-based prayer expectancies of older whites tend to decline over time.

Although a number of factors in the study model explain why older blacks have stronger trust-based prayer expectancies than older whites, one appears to be especially important. As the data in Table 3 reveal, older blacks are much more likely to affiliate with a Conservative Protestant denomination than older whites (Beta = −.393; p < .001).

Conclusions

Three major findings emerge from this study. First, the findings reveal that there is significant variation in the extent to which older people endorse trust-based prayer expectancies. More specifically, those who subscribe to these prayer beliefs are more likely to affiliate with Conservative Protestant congregations and they are more likely to be black.

Second, the data suggest that prayer expectancies tend to be maintained and reinforced through social aspects of congregational life. Attendance at prayer group meetings and informal spiritual support both play an important role in this respect, but of the two, informal spiritual support appears to be more influential. This makes sense for the following reason. People have a significant amount of freedom in choosing the individuals with whom they exchange spiritual support. But in contrast, they have relatively less control over the individuals they interact with in prayer groups. As a result, relationships with informal social network members are likely to be closer and therefore carry greater weight in shaping views about religious life.

Third, the results reveal that older people who have strong trust-based prayer beliefs are likely to report that they are more satisfied with their lives. Greater confidence may be placed in these findings because the relationship between these variables was viewed with data that were gathered at more than one point in time.

Although the findings from the current study may have contributed to the literature, a considerable amount of research on prayer beliefs remains to be done. For example, research reveals that people often turn to prayer when they encounter stressful life events (Pargament 1997). Perhaps the expectancies they have regarding the outcomes of their prayers may buffer or offset the deleterious effects of stress on their health and sense of well-being. Another issue that should be examined involves assessing potential age differences in the extent to which trust-based prayer beliefs are endorsed. A number of researchers maintain that people become more religious as they grow older (see Krause 2008, for a review of this research). It would be important to know if this growing sense of religiousness is manifest in a greater sense of trust in God as well as greater trust in the answers He gives to prayers. Yet another issue to examine in the future involves the degree of fit between prayer beliefs that are endorsed by a study participant and the official doctrine regarding prayer beliefs in the place where they worship. If there is a discrepancy between the two, then it is unlikely that spiritual support from fellow church members would exert a positive effect on prayer expectancies. Moreover, a discrepancy of this nature might diminish feelings of life satisfaction.

In the process of exploring these issues it is important to address the limitations in the current study. Two shortcomings should be addressed here. First, even though the data for the current study were gathered at more than one point in time, it is still not possible to conclusively assert that trust-based prayer beliefs “cause” greater life satisfaction. This issue can only be addressed with studies that employ true experimental designs. Second, because people who do not go to church often were excluded from our analyses, it should be emphasized that our study deals only with religiously engaged Christians. Therefore, we cannot tell whether the findings generalize to the prayer lives of people who either do not attend church or who go only once or twice a year.

In the process of addressing this as well as other shortcomings, there is a wider message in this study that will hopefully not be lost. Researchers have studied religious beliefs for decades. But a good deal of this research has been concerned with religious beliefs that are rather general in nature, such as belief in God or belief in heaven and hell (see Hill and Hood 1999 for a review of these measures). Unfortunately, this way of studying religious beliefs has not proven to be very useful in research on religion and health. One way out of this difficulty may involve focusing on much more specific beliefs that are exercised in a more limited behavioral context, such as trust-based prayer expectancies. As the findings from the current study suggest, pursuing this strategy may provide greater insight and promote a deeper appreciation for the complex ways in which religious beliefs may influence health and well-being.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG014749) and the John Templeton Foundation.

Neal Krause is the Marshall H. Becker Collegiate Professor in the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health. His research focuses primarily on the relationship between social relationships in the church and health among older people. He has conducted nationwide surveys on this issue among older whites, older blacks, and older Mexican Americans.

Appendix. List of Conservative Protestant Denominations

African Methodist Episcopal

African Methodist Episcopal Zion

American Baptist Association

Apostolic

Assembly of God

Bethany Open Bible

Bible Fellowship Church

Calvary Chapel

Calvary Reform

Christ Holy Sanctified

Christ Memorial

Christian Reformed

Christian and Missionary Alliance

Church of Christ

Church of God

Church of God in Christ

Church of Holiness

Emanuel Evangelical Brotherhood

Evangelical

Evangelical Lutheran

Faith Bible

Holiness

Jehovah’s Witnesses

Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod

Mennonite

Mormon - Church of the Latter Day Saints

National Baptist Convention

National Baptist Convention USA

Nazarene

Other Baptist Churches

Other Methodist Churches

Other Presbyterian

Pentecostal

Salvation Army

Seventh Day Adventist

Southern Baptist Convention

Truth Gospel Holiness Church

Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod

Footnotes

Researchers have encountered significant difficulty differentiating between Conservative Christians, fundamentalists, evangelicals, and Pentecostals. Evidence of this may be found, for example, in the work of Woodberry and Smith (1998). These investigators argue that, “… distinguishing between Conservative Christians, evangelicals, charismatics, and Pentecostals is complex … They are better understood as loosely connected networks of ministerial, parachurch organizations, schools, seminaries …” (Woodberry and Smith 1998, p. 33). In fact, merely trying to identify the defining characteristics of Pentecostalism is fraught with difficulty, as Hunt, Hamilton, and Walter (1997) found. These investigators reluctantly concluded that, “… the movement is evolving so rapidly that it is not entirely clear whether these distinguishing hallmarks still hold” (Hunt et al. 1997, p. 2). Clearly, the current study is not the place to resolve these longstanding issues in the field. As a result, the term “Conservative Protestant” is used in the discussion that follows.

The proportion of Conservative Protestants in the current study might initially appear to be much higher than their numbers in the general population. However, it is important to recall that approximately half the participants in the current study are African American, and as the data provided later in this study will reveal, they are much more likely than whites to affiliate with Conservative Protestant congregations.

Contributor Information

Neal Krause, University of Michigan.

R. David Hayward, University of Michigan.

References

- Baesler EJ, Lindvall T, Lauricella S. Assessing predictions of Relational Prayer Theory: Media and interpersonal inputs, private and public prayer processes, and spiritual health. Southern Communication Journal. 2011;76:191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Barna G. The state of the church 2002. Ventura, CA: Issachar Resources; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barna G. The state of the church 2006. Ventura, CA: Issachar Resources; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Berger PL. The sacred canopy: Elements of a sociological theory. New York: Doubleday; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley WJ, Schaefer KC. The uses and misuses of data and models: The mathematization of the human sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Breslin MJ, Lewis CA. Theoretical models of the nature of prayer and health: A review. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2008;11:9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cottingham J. The spiritual dimension: Religion, philosophy, and human value. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DeShon RP. A cautionary note on measurement error correlations in structural equation models. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:412–423. [Google Scholar]

- du Toit M, du Toit S. Interactive LISREL: User’s guide. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review o Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical considerations of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70:646–675. [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Hood RW. Measures of religiosity. Birmingham, AL: Religious Education Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook AL, Krosnick JA, Pfent A. The causes and consequences of response rates in surveys by the news media and government contractor research firms. In: Lepkowski JM, Tucker C, Brick M, Leeuw E, Lilli J, Lavrakas PJ, Link MW, Sangster RL, editors. Advances in telephone survey methodology. New York: Wiley; 2008. pp. 499–528. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S, Hamilton M, Walter T. Charismatic Christianity: Sociological perspectives. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002a;57B:S332–S347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. A comprehensive strategy for developing closed-ended survey items for use in studies of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002b;57B:S263–S274. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.s263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Assessing the relationship among prayer expectancies, race, and self-esteem in late life. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2004;65:35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. God-mediated control and psychological well-being in late life. Research on Aging. 2005;27:136–164. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. God-mediated control and change in self-rated health. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2010;20:267–287. doi: 10.1080/10508619.2010.507695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Assessing the prayer lives of older whites, older blacks, and older Mexican Americans: A descriptive analysis. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2012;22:60–78. doi: 10.1080/10508619.2012.635060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Chatters LM, Meltzer T, Moran DL. Using focus groups to explore the nature of prayer in late life. Journal of Aging Studies. 2000a;14:191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Race and gender differences in religiosity among older adults: Findings from four national surveys. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1994;49:S137–S145. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard S. Sage University Paper series in Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, series no 76. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. Longitudinal research. [Google Scholar]

- Nummela O, Sulander T, Rahkonen O, Uutela A. The effect of trust and change in trust on self-rated health: A longitudinal study among aging people. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2009;49:339–342. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JM, Roese NJ, Zanna MP. Expectancies. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford; 1996. pp. 211–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrander R. Proving the living God: Answered prayer as a modern Conservative Christiansapologetic. Fides et Historia. 1996;28:69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religious coping: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Poloma MM, Gallup GH. Varieties of prayer: A survey report. Philadelphia: Trinity Press International; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Widaman KF, Pugh RH. Confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: Two approaches for exploring measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:552–566. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider IK, Konjin EA, Righetti F, Rusbult CE. A healthy dose of trust: The relationship between interpersonal trust and health. Personal Relationships. 2011;18:668–676. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp S. How does prayer help manage emotions? Social Psychology Quarterly. 2010;73:417–437. [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin M, Miles JN. Effects of sample size, model specification, and factor loadings on the GFI in confirmatory factor analysis. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;25:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW. Classifying Protestant denominations. Review of Religious Research. 1990;31:225–245. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R. What Americans really believe. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Finke R. Acts of faith: Explaining the human side of religion. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C. Prayer among the Benedictines. In: Hammerling R, editor. The history of prayer: The first to the fifteenth century. Boston: Brill; 2008. pp. 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry RD, Smith CS. Fundamentalism et al, Conservative Protestants in America. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998;24:25–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow R. Sharing the journey: Support groups and America’s new quest for community. New York: Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zaspel FG. B B Warfield, A systematic inquiry. Wheaton, IL: Crossway; 2010. [Google Scholar]