Abstract

Background

Significant morbidity associated with acute liver failure (ALF) is from the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) has been shown to play an integral role in the modulation of SIRS. However, little is known about the mechanistic role of TLR4 in ALF. Also, no cell type has been identified as the key mediator of the TLR4 pathway in ALF. This study examines the role of TLR4 and Kupffer cells in the development of the SIRS following acetaminophen (APAP)-induced ALF.

Materials and Methods

Five groups of mice were established: untreated wild-type, E5564-treated (a TLR4 antagonist), gadolinium chloride (GdCl3)-treated (Kupffer cell-depleted), clodronate-treated (Kupffer cell-depleted), and TLR4-mutant. Following APAP administration, 72-hour survival, biochemical and histologic liver injury, extent of lung injury and edema, and pro-inflammatory gene expression were studied. Additionally, TLR4 expression was determined in livers of wild-type and Kupffer cell-depleted mice.

Results

Following APAP administration, wild-type, TLR4-mutant, E5564-treated, and Kupffer cell-depleted mice had significant liver injury. However, wild-type mice had markedly worse survival compared to the other 4 treatment groups. TLR4-mutant, E5564-treated, and Kupffer cell-depleted mice had less lung inflammation and edema than wild-type mice. Selected pro-inflammatory gene expression (il1b, il6, tnf) in TLR4-mutant, E5564-treated, and Kupffer cell-depleted mice was significantly lower compared to wild-type mice after acute liver injury.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that survival in APAP-induced ALF potentially correlates with the level of pro-inflammatory gene expression. This study points to a link between TLR4 and Kupffer cells in the APAP model of ALF, and, more importantly, demonstrates benefits of TLR4 antagonism in ALF.

Keywords: E5564, acute liver failure, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, mice

Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is associated with a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in approximately 60% of cases (1). When patients in ALF develop SIRS, their mortality rate has been shown to significantly increase compared to patients who do not develop SIRS (1, 2). The etiology of SIRS in ALF is not well understood, but is believed to be multi-factorial. This subset of patients has demonstrated an increase in the release of inflammatory mediators and the injured liver is thought to be the cause (3–5). Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is a known mediator of SIRS in sepsis (6–8) and has been speculated as a key activator or SIRS seen in ALF. However, the relationship between ALF, TLR4, and SIRS has not been well-defined.

TLR4 is stimulated by LPS, heparan sulfate, fibrinogen, fibronectin extra domain A and hyaluronic acid (9). In ALF hyaluronic acid is found to be significantly elevated from baseline shortly after injury (10), which leads to the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (11). These same pro-inflammatory cytokines have been shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of ALF (3–5, 12, 13). In addition, the novel TLR4 antagonist E5564 has been shown to decrease the extent of liver injury and the SIRS response following the administration of LPS (14) and D-Galactosamine (15).

Kupffer cells represent the largest population of resident macrophages in the body (16, 17). Previous reports have shown that stimulation of Kupffer cells leads to the release of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines through multiple pathways including TLR4 (6, 18). As a result, these cells have been shown to be both protective and injurious through their release of cytokines in various models of liver injury (19, 20). The effect of Kupffer cells on survival in the setting of drug-induced ALF is not known. We hypothesize that SIRS associated with drug-induced ALF may in part be related to TLR4 activation on Kupffer cells.

To test our hypothesis, we used acetaminophen (APAP) to induce ALF in mice. APAP toxicity is the most common cause of ALF in the United States (21). APAP is known to induce cell injury through the depletion of reducing substrates leading to cellular necrosis (22). In this study, we identify a link between the SIRS of ALF and Kupffer cell specific TLR4 activity.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Acetaminophen (APAP) and gadolinium chloride (GdCl3) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Liposomal clodronate was purchased from ClodronateLiposomes.org (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). E5564 (a TLR4 antagonist) was provided generously by Eisai Research Institute (Andover, MA).

Animals

All animals were handled in compliance with the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at the Mayo School of Graduate Medical Education. C3H/HeJ (wild-type) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). C3H/HeN (TLR4 mutant) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). All mice were male, seven to eight weeks of age, and weighed 22–24g. ALF was induced by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of APAP (500 mg/kg). Animals were examined at two hour intervals post injection until either meeting a pre-specified mortality equivalent (no response to painful stimuli) or elective sacrifice. Clinical status was classified by response to stimulation as normal, lethargic (abnormal response to pain), or dead/mortality equivalent (no response to painful stimuli). Wild-type mice were depleted of Kupffer cells by administration of either GdCl3 (10mg/kg) intravenously 24h prior APAP or liposomal clodronate (200ul) intravenously 48h prior to APAP. These time intervals were associated with maximum depletion of Kupffer cells in prior studies (23, 24). Wild-type mice treated with E5564 received 1 mg/kg in 50ul of sterile water 1h prior to APAP and 5h after APAP. E5564 dosing was based upon previous work in LPS-exposed mice (14). The timing of E5564 was based upon pilot studies with 72-hour survival as the primary endpoint (data not shown in this study).

Detection of Kupffer cells by Immunohistochemistry

Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded liver sections were treated with 3% H2O2 in ethanol for 5 min to inactivate endogenous peroxidase. Sections were pretreated with proteinase K (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) and endogenous mouse immunoglobulins were blocked using Rodent Block M (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA). Sections were incubated with rat anti-mouse F4/80 primary antibody (MCA497EL, AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC) for 60 min using a 1/400 dilution. Labeling of the primary antibody was carried out using Biocare Medical’s Rat on Mouse kit (RT517) and diaminobenzidine. Sections were then counterstained using Modified Schmidt’s Hematoxylin and visualized using a Zeiss Axiovert 135 microscope. Kupffer cells were counted per 40x field across 10 separate visual fields in order to quantify depletion.

Serum Liver Enzymes

Blood samples were placed in SST vacutainers BD (Franklin Lakes, NJ) and kept at room temperature for 30 min before being centrifuged at 3000×g for 10 min. The serum activities of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were determined using an automated clinical analyzer Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany).

Quantification of Liver Necrosis

Sections of fresh liver tissue were immediately fixed in formalin. After approximately 24h, the tissue was dehydrated with 100% ethanol and embedded in paraffin. The sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Tissue sections were examined under light microscopy for percentage of liver necrosis in five low-powered (10x) fields of view per tissue section from each mouse (10/group).

TLR4 reporter cell assay

HEK293 cells stably transfected with TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 (TLR4 signaling complex) and an NF-κB driven secretory alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter were obtained from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA) and cultured according to manufacturer’s instructions. HEK293 cells were also stably transfected with the same NF-κB driven SEAP reporter (pNiFty2-SEAP; InvivoGen) plasmid using the SuperFect transfection system from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Individual clones were selected and grown under Zeocin pressure to generate a complementary TLR4 negative reporter cell line. SEAP content is measured in the culture supernatant of these cells lines using the QUANTI-Blue™ detection system (InvivoGen). To measure the presence of TLR4 activators in acetaminophen-treated mice, serum was collected 12h after intraperitoneal injection of 500 mg/kg acetaminophen. 20,000 TLR4 positive or TLR4 negative cells were plated in individual wells of a 96 well sterile, tissue culture treated plate using DMEM with 10% FBS, 1x penicillin, 1x streptomycin, and 1x L-glutamine. Mouse serum was then added to a final concentration of 0.05% (run in triplicate for each reporter cell line). Cells were then incubated for 12h at 37°C and 5% CO2. 20μL of culture supernatant was then added to 200μL of QUANTI-Blue solution in a new 96 well sterile tissue-culture plate. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 2h and then SEAP content assessed by measuring A635 spectrophotometrically as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantification of Lung Edema and Inflammation

Lung edema was quantified as described previously (25). Briefly, the left lung was excised and rinsed in saline, gently blotted on a paper towel, and then weighed. The lung tissue was then placed on foil and dried at 60°C for 72h and then reweighed. The ratio wet to dry weight was quantified and used as an indicator of lung edema. The right lung was excised and prepared in the same manner as liver tissue for histology. Tissue sections were examined under light microscopy for extent of inflammation in five high-powered (40x) fields of view per tissue section from each mouse (10 mice per group). Lung inflammation was graded from 0 to 3 with a score of 0 corresponding to less than 5% inflammatory cell infiltrate per 40x field over ten fields, 1 equaling 5–30%, 2 equaling 30–50% and 3 yielding more than 50%.

Isolation of mouse hepatocytes and nonparenchymal liver cell populations

Wild type C57/Bl6 hepatocytes were isolated by collagenase perfusion as previously described (26). Briefly, isolated hepatocytes were purified by Percoll (Sigma) gradient centrifugation. The viability of isolated hepatocytes was greater than 95% by trypan blue exclusion. Hepatocytes were plated in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100,000 units/liter penicillin and 100 mg/liter streptomycin. Attached hepatocytes were lysed in TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for RNA isolation.

Nonparenchymal cells (NPCs) and Kupffer Cells (KCs) were isolated from murine livers by pronase (Roche) and collagenase (Roche) perfusion and selective adhesion. Mouse liver was perfused with buffer SC-1 for 3 min. This was followed by digestion with 0.05% pronase for 5 min and 0.028% collagenase for 10 min. Pronase and collagenase solutions were in buffer SC-2. Buffers SC-1 and SC-2 have been previously described (27). The liver was removed, cells dispersed and further digested ex vivo for 15 min with 0.05% pronase and 0.028% collagenase at 37°C with constant stirring. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 50×g for 2 min to remove hepatocytes. NPCs were pelleted from the resulting supernatant and applied to a discontinuous Percoll gradient as described by Pertoft and Smedsrod (28). Kupffer cells were collected and further enriched by selective attachment to tissue culture plastic for 30 min in the medium described above. NPC/KC isolates and further enriched KCs were lysed in TRIzol reagent for RNA isolation.

Quantification of cytokine and TLR4 gene expression

RNA was isolated from liver tissue or lysed cells using RNeasy Plus kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcripts were created using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad, Berkley, CA) or High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) per the manufactures’ instructions. Resulting cDNA was stored at −20°C. APAP-induced alterations in liver expression of selected pro-inflammatory cytokines and TLR4 were determined using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Primers for tnf (Mm99999068), il1b (Mm00434227), il6 (Mm99999064), and tlr4 (Mm00445273) were obtained from Applied Biosystems. PCR condition: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C and 1 min of annealing/extension at 60°C. All results were normalized using Mouse GAPDH (Applied Biosystems) as a control.

Statistical methods

Results are expressed as mean values ± standard error (SEM). Survival data was compared using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Studentized Range test. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).. Significance was established at p<0.05 level.

Results

Histologic and biochemical measurements of liver injury

Mice were separated into 5 groups (wild-type, TLR4-mutant, E5564-treated, Kupffer cell depleted mice using GdCl3 or liposomal clodronate). GdCl3-treated mice displayed a 51.2 ± 10.2% reduction in Kupffer cells compared to untreated mice (p<0.05), while clodronate-treated mice showed a 98.7 ± 2.3% reduction in Kupffer cells compared to untreated mice (p<0.05) (data not shown).

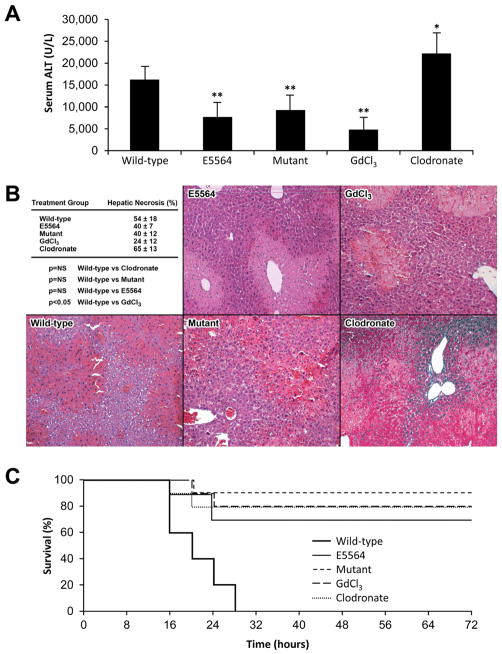

ALT levels were measured 12h after IP injection of either saline or APAP in order to determine the extent of liver injury following injection of the hepatotoxin, APAP. Each group tested consisted of 10 mice. As expected, ALT levels were not elevated from the normal range following IP injection of saline in untreated wild-type mice (29.4 ± 6.5 U/L), wild-type mice treated with GdCl3 (36.9 ± 8.5 U/L), and wild-type mice treated with clodronate (27.6 ± 12.1 U/L). However, ALT levels rose significantly in all experimental groups 12h following IP injection of APAP. Wild-type mice had higher ALT levels than TLR4-mutant mice (p <0.05), E5564-treated mice (p<0.05), and GdCl3-treated mice (p<0.05). Of note, ALT levels were highest in clodronate-treated mice (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Liver injury and survival following APAP injection (N = 10 mice per group).

(A) Wild-type, E5564-treated, mutant, GdCl3-treated, and clodronate-treated mice received APAP to induce acute liver injury. The clodronate-treated mice had the highest serum ALT (22222 ± 4700 U/L, *p<0.05). The E5564-treated (7755 ± 3254 U/L), mutant (9266 ± 3358 U/L), and GdCl3-treated mice (4784 ± 2859 U/L) had significantly lower ALT compared to wild-type mice (**p<0.05). (B) Amount of liver necrosis was similar for E5564-treated (40 ± 7%), mutant (40 ± 12%), and clodronate-treated mice (65 ± 13%) when compared to wild-type mice (54 ± 18%). GdCl3-treated mice (24 ± 12%) had significantly less liver necrosis compared to the wild-type group (p<0.05). (C) Percentage survival was determined over 72h. All untreated wild-type mice met their mortality equivalent by 28h. At 72h, 90% of mutant mice were alive, 80% of both groups of Kupffer cell-depleted mice were alive, and 70% of E5564-treated mice were alive.

The livers in each group were examined histologically for necrosis. No evidence of necrosis was observed after injection of saline (data not shown). In contrast, injection of APAP resulted in centrilobular necrosis with loss of hepatocellular architecture and vacuolization in all five groups. Hepatic necrosis was not significantly different in untreated wild-type mice compared to TLR4-mutant mice, E5564-treated mice, and liposomal clodronate-treated wild-type mice. However, GdCl3-treated wild-type mice has less hepatic necrosis following APAP compared to untreated wild-type mice (p<0.05) (Fig. 1B).

Survival of TLR4-mutant, E5564-treated, and Kupffer cell-depleted mice compared to untreated wild-type mice following APAP administration

Survival of four experimental groups (TLR4-mutant, E5564-treated, Kupffer cell depleted mice using GdCl3 or liposomal clodronate) was compared to the survival of wild-type control mice following injection of APAP. Mice in the 5 groups (10 mice per group) were all given a single IP dose of APAP. All untreated control wild-type mice met their mortality equivalent by 28h. Ninety percent of the TLR4-mutant mice were alive and appeared active and healthy by physical examination at 72h (p<0.05). Similar findings were seen at 72h in the E5564-treated mice (70% survival, p<0.05) and the Kupffer cell-depleted mice using either GdCl3 or clodronate (80% survival, p<0.05) (Fig. 1C).

Measure of endogenous TLR4 agonist

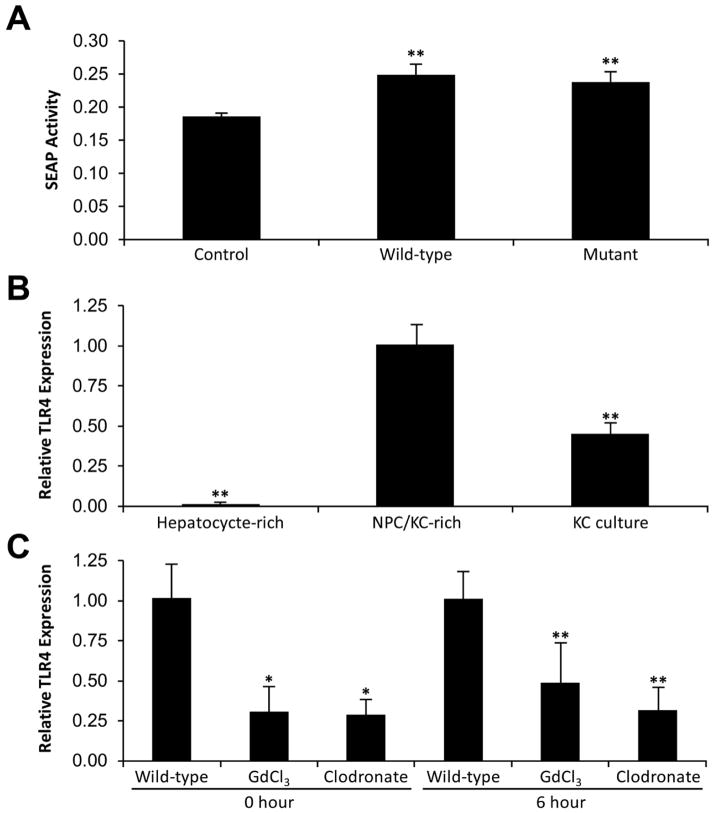

Serum was collected from both wild-type and TLR4-mutant mice 12h after injection of APAP or saline alone in order to determine how hepatocyte necrosis affects the level of TLR4 agonists present within the serum (endogenous) (10 mice per group). TLR4 agonist levels were measured indirectly in serum samples by quantitative NF-κB driven secretory alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter activity. SEAP activity was similar in wild-type mice and TLR4-mutant mice (p=NS). However, both wild-type and TLR4-mutant mice treated with APAP had higher SEAP activity than saline injected control mice (p<0.05 and p<0.05, respectively) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. TLR4 agonist activity and TLR4 expression at baseline and after APAP.

(A) In order to determine if the presence of TLR4 agonists were similar in wild-type mice and mutant mice after APAP exposure, 10 wild-type mice and 10 mutant mice were euthanized 12h after administration of APAP. Using a SEAP reporter assay, TLR4 agonist activity was indirectly determined and compared to saline control wild-type mice (N = 10 mice). Wild-type and mutant mice had significantly higher endogenous serum TLR4 activity 12h following APAP compared to wild-type mice at baseline (**p<0.05) (N = 10 mice per group). (B) Liver cells were isolated for baseline TLR4 mRNA expression. The NPC/KC-rich fraction had the highest expression of TLR4 followed by isolated KCs. TLR4 expression was significantly different between all groups (**p<0.05). (C) At baseline, wild-type liver had significantly higher relative TLR4 expression than GdCl3-treated and clodronate-treated liver (*p<0.05). At 6h after APAP, wild-type liver had higher relative TLR4 expression than GdCl3-treated and clodronate-treated liver; however, this difference was not significant**p=NS).

TLR4 expression in cell fractions of liver tissue

TLR4 expression was determined from hepatocyte-rich and NPC/KC rich fractions of wild-type liver tissue. The NPC/KC fraction expressed 500-fold more TLR4 than the hepatocyte cell fraction (p<0.05). KCs were enriched from the NPC/KC fraction. The KC-enriched culture expressed about half the level of TLR4 as the NPC/KC fraction (p<0.05) (Fig. 2B).

To determine how Kupffer cells affect TLR4 expression in liver tissue, TLR4 expression was quantified in liver tissue of wild-type mice and wild-type mice depleted of Kupffer cells by GdCl3 or clodronate before and 6h after APAP-induced ALF (10 mice per group). Relative expression of liver specific TLR4 was significantly reduced after GdCl3-treatment (p<0.05) and after clodronate-treatment (p<0.05). Furthermore, six hours after induction of ALF the relative expression of TLR4 remained lower in both Kupffer cell-depleted mice groups. However, neither group had significantly lower expression (Fig. 2C).

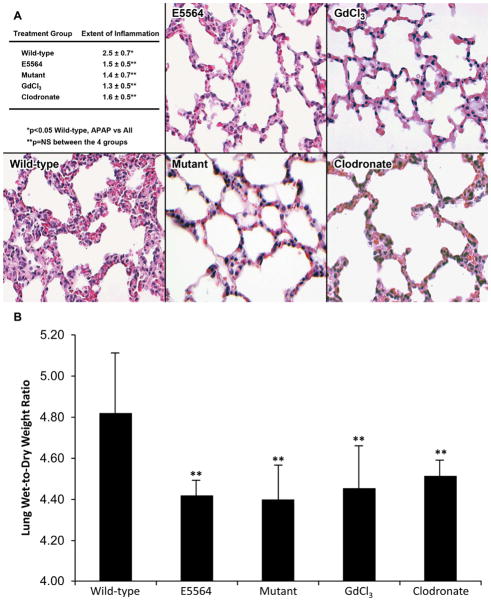

Measurement of SIRS

Wet-to-dry weight ratios were used to signify lung water content (lung edema) following administration of APAP as an indicator for systemic inflammation. Untreated wild-type mice had significantly higher lung weight ratios compared to TLR4-mutant mice (p<0.05), E5564-treated mice (p<0.05), and to Kupffer cell-depleted mice (GdCl3-treated, p<0.05; clodronate-treated, p<0.05) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Lung histology, inflammation, and edema 12h after APAP (N = 10 mice per group).

Wild-type, E5564-treated, mutant, GdCl3-treated, and clodronate-treated mice received APAP to induce acute liver injury. These mice had their lungs excised 12h after APAP to determine the effect liver injury had on lung inflammation. (A) The wild-type group (2.5 ± 0.7) had a significantly higher extent of lung inflammation when individually compared to the other 4 groups (p<0.05). The E5564 (1.5 ± 0.5), mutant (1.4 ± 0.7), and Kupffer cell-depleted groups (GdCl3 1.3 ± 0.5, Clodronate 1.6 ± 0.5) were statistically similar in the extent of lung inflammation. Extent was grade 0–3. 0=<5% of section; 1=5-<30%; 2=30-<50%; 3=50% or more. (B) Lung edema was determined by weighing lung tissue immediately after euthanization and repeating lung weights after 72h of drying. The wild-type group (4.75 ± 0.27) had a significantly higher amount of lung edema compared to the other 4 groups (E5564 4.39 ± 0.07, mutant 4.37 ± 0.15, GdCl3 4.42 ± 0.19, Clodronate 4.47 ± 0.07) after 12h of APAP (**p<0.05).

In addition to their increased weight, the lungs of wild-type mice had increased inflammation scores 12h following APAP administration when compared to TLR4-mutant mice (p<0.05), E5564-treated mice (p<0.05), GdCl3-treated mice (p<0.05), and clodronate-treated mice (p<0.05). There was no significant difference in lung inflammation between the TLR4-mutant mice, E5564-treated mice, and the Kupffer cell-depleted mice (Fig. 3B).

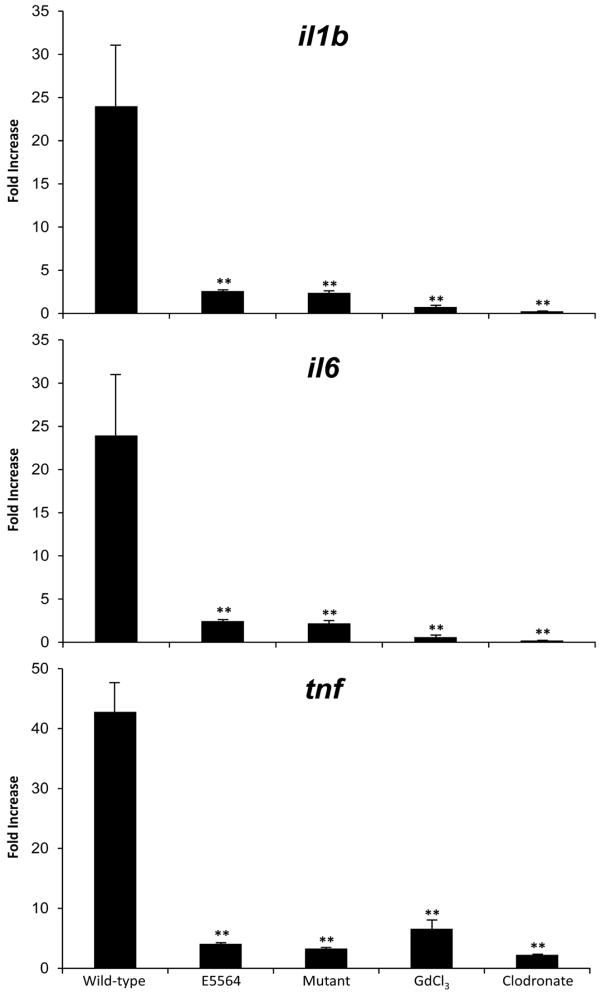

Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in liver tissue

Wild-type mice had significantly higher fold expression of all three pro-inflammatory cytokines (il1b, il6, and tnf)compared to TLR4-mutant mice (p<0.05), E5564-treated mice (p<0.05), GdCl3-treated mice (p<0.05), and clodronate-treated mice (p<0.05) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Fold change in gene expression of liver tissue after 6h of APAP (N = 10 mice per group).

Wild-type, E5564-treated, mutant, GdCl3-treated, and clodronate-treated mice received APAP to induce acute liver injury. These mice were euthanized at 6h after APAP. Their livers were excised and used for pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression analysis. Fold change in gene expression was measured for il1b, il6, and tnf from 6h liver tissue samples standardized to 0h baseline liver tissue samples. The wild-type group had significantly higher gene expression of the 3 pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to the other 4 groups (** p<0.05).

Discussion

ALF remains a significant clinical problem with an approximate incidence of 2,500 cases in the United States and much higher worldwide (21). It is estimated that approximately 60% of patients with ALF develop SIRS1. Many of these patients die of extrahepatic complications including multiple organ system failure and brain edema (herniation) (1, 2, 29, 30). In this study, we show that reduction of TLR4 activity is associated with mitigation of SIRS and improved survival in a mouse model of APAP-induced ALF. We also show that the TLR4 activity of Kupffer cells is a main contributor to the SIRS seen in ALF, and that modulation of the TLR4 pathway by depletion of Kupffer cells or direct antagonism of TLR4 receptor leads to improved survival following APAP-induced ALF despite differing levels of liver injury.

The connection between SIRS and sepsis has been a topic of study for the last 20 years. Efforts have been made to identify specific pathways key to the SIRS in sepsis. LPS activation of TLR4 has been identified as a significant pathway leading to downstream pro-inflammatory cytokine propagation in the setting of sepsis (6, 7, 9, 11, 31, 32). TLR4 has also been recognized as a potent initiator of SIRS in aseptic, “non-infectious” settings. Endogenous (non-LPS) TLR4 agonists have been identified in the setting of acute organ injury, and the presence of these molecules has been shown to correlate with SIRS-like reactions in the absence of infection (9). In our study, we show that serum from wild-type and TLR4-mutant mice have significantly higher levels of TLR4 agonist activity following liver injury when compared to the non-injured state. Our findings are supported by others who have shown that LPS-independent heat resistant protein molecules can be isolated from injured livers and these molecules have been shown to activate pro-inflammatory cytokine production by macrophages through a TLR4 specific pathway (33).

To test the importance of TLR4 in the APAP-induced mouse model of ALF we investigated two interventions. The first intervention was to the use of TLR4-mutant mice. TLR4ko mice have previously been shown to have markedly reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and improved survival compared to wild-type mice in the D-GaIN/LPS model of acute liver injury (12). The second intervention was to antagonize TLR4 with the competitive lipid A analogue inhibitor, E5564. Lipid A is a key component of LPS, and acts as a potent agonist of TLR4. E5564 has previously been reported to improve survival in rodent models of LPS administration and hepatotoxicity by decreasing systemic inflammation (14, 15). Both interventions, TLR4 mutation and TLR4 antagonism, were associated with improved survival, less lung inflammation and edema (manifestation of SIRS) and significantly lower expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Together, these findings suggest a potentially important role of TLR4 in initiating the SIRS of ALF.

Many cell populations in the liver express TLR4, including Kupffer cells, stellate cells, hepatocytes, biliary epithelial cells, and endothelial cells (6, 32). However, only stellate cells and Kupffer cells demonstrate significant expression of NF-κB and TNF after exposure to LPS (34, 35). This increased expression of NF-κB and TNF has been shown to occur, in part, through a TLR4 mediated pathway. Blocking NF-kB and TNF activity in acute liver failure has been shown to reduce mortality in animal models (36, 37). Additionally, Kupffer cells have been linked to activation of NF-kB and downstream production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by way of TLR4 (38). In this study, we show that Kupffer cells contribute to the increased expression of TLR4 in the liver in response to acute injury.

In our study, E5564-treated, TLR4-mutant, and Kupffer cell-depleted mice using GdCl3 had significantly less liver injury than Kupffer cell-depleted mice using clodronate. Yet, all four of these groups of mice had significantly improved survival compared to untreated wild-type mice. Kupffer cells are believed to be hepatoprotective in APAP-induced ALF (19, 20). Our study suggests that systemic effects secondary to Kupffer cell activation are more dominant than local effects. To elucidate the connection between Kupffer cells and TLR4 expression in APAP-induced ALF, we examined TLR4 expression in whole livers of untreated wild-type mice and wild-type mice partially depleted (GdCl3) or near-completely depleted (clodronate) of Kupffer cells. From our study, Kupffer cells express a substantial level of TLR4 that when depleted lead to a lower whole liver expression of TLR4. This modulated expression of TLR4 correlated with the attenuated pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression profile and suggests that TLR4 receptor activity is linked to the presence of Kupffer cells in the APAP-induced ALF mouse model.

We conclude that activation of TLR4 is critical to the systemic manifestations of APAP-induced ALF. The TLR4 pathway can be modulated by novel agents, such as E5564, resulting in improved survival following liver injury. Improved survival following TLR4 modulation was associated with normalized profiles of pro-inflammatory cytokine. Additionally, our data suggests that the TLR4 activity of Kupffer cells plays a major role on the SIRS of APAP-induced ALF. Together TLR4 and Kupffer cells may serve as targets for improving survival in APAP-induced ALF.

Acknowledgments

Funding provided by NIH-R01-DK56733

James Fisher and Travis Mckenzie were supported by the Clinical Investigator Training Program – Mayo Foundation

Joseph Lillegard was supported by the American Society of Transplant Surgery (ASTS)-NKF Folkert Belzer, MD research fellowship

E5564 was gifted by Eisai Research Institute. No monetary support was received from Eisai Research Institute for completion of this study.

Abbreviations

- ALF

acute liver failure

- SIRS

systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- TLR4

toll-like receptor 4

- APAP

acetaminophen

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- GdCl3

gadolinium chloride

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- SEAP

secretory alkaline phosphatase

Footnotes

Disclosures: No disclosures for any authors. No conflict of interests for any authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

James E. Fisher, Email: fisher.james@mayo.edu.

Travis J. Mckenzie, Email: tjmckenzie@partners.org.

Joseph B. Lillegard, Email: lillegard.joseph@mayo.edu.

Yue Yu, Email: yuyue@njmu.edu.cn.

Justin E Juskewitch, Email: juskewitch.justin@mayo.edu.

Geir I. Nedredal, Email: nedredal.geir@mayo.edu.

Gregory J. Brunn, Email: brunn.gregory@mayo.edu.

Eunhee S. Yi, Email: yi.joanne@mayo.edu.

Thomas C. Smyrk, Email: smyrk.thomas@mayo.edu.

Scott L. Nyberg, Email: nyberg.scott@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Rolando N, Wade J, Davalos M, Wendon J, Philpott-Howard J, Williams R. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2000;32:734–739. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.17687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaquero J, Polson J, Chung C, Helenowski I, Schiodt FV, Reisch J, Lee WM, Blei AT. Infection and the progression of hepatic encephalopathy in acute liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:755–764. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekiyama KD, Yoshiba M, Thomson AW. Circulating proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1 beta, TNF-alpha, and IL-6) and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) in fulminant hepatic failure and acute hepatitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;98:71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boermeester MA, Houdijk AP, Meyer S, Cuesta MA, Appelmelk BJ, Wesdorp RI, Hack CE, Van Leeuwen PA. Liver failure induces a systemic inflammatory response. Prevention by recombinant N-terminal bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1428–1440. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galun E, Axelrod JH. The role of cytokines in liver failure and regeneration: potential new molecular therapies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1592:345–358. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su GL, Klein RD, Aminlari A, Zhang HY, Steinstraesser L, Alarcon WH, Remick DG, Wang SC. Kupffer cell activation by lipopolysaccharide in rats: role for lipopolysaccharide binding protein and toll-like receptor 4. Hepatology. 2000;31:932–936. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhai Y, Shen XD, O’Connell R, Gao F, Lassman C, Busuttil RW, Cheng G, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Cutting edge: TLR4 activation mediates liver ischemia/reperfusion inflammatory response via IFN regulatory factor 3-dependent MyD88-independent pathway. J Immunol. 2004;173:7115–7119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiller S, Elson G, Ferstl R, Dreher S, Mueller T, Freudenberg M, Daubeuf B, Wagner H, Kirschning CJ. TLR4-induced IFN-gamma production increases TLR2 sensitivity and drives Gram-negative sepsis in mice. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1747–1754. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson GB, Brunn GJ, Platt JL. Cutting edge: an endogenous pathway to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)-like reactions through Toll-like receptor 4. J Immunol. 2004;172:20–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dechene A, Sowa JP, Gieseler RK, Jochum C, Bechmann LP, El Fouly A, Schlattjan M, Saner F, Baba HA, Paul A, Dries V, Odenthal M, Gerken G, Friedman SL, Canbay A. Acute liver failure is associated with elevated liver stiffness and hepatic stellate cell activation. Hepatology. 2010;52:1008–1016. doi: 10.1002/hep.23754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erridge C, Bennett-Guerrero E, Poxton IR. Structure and function of lipopolysaccharides. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:837–851. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben Ari Z, Avlas O, Pappo O, Zilbermints V, Cheporko Y, Bachmetov L, Zemel R, Shainberg A, Sharon E, Grief F, Hochhauser E. Reduced hepatic injury in Toll-like receptor 4-deficient mice following D-galactosamine/lipopolysaccharide-induced fulminant hepatic failure. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;29:41–50. doi: 10.1159/000337585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leifeld L, Dumoulin FL, Purr I, Janberg K, Trautwein C, Wolff M, Manns MP, Sauerbruch T, Spengler U. Early up-regulation of chemokine expression in fulminant hepatic failure. J Pathol. 2003;199:335–344. doi: 10.1002/path.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullarkey M, Rose JR, Bristol J, Kawata T, Kimura A, Kobayashi S, Przetak M, Chow J, Gusovsky F, Christ WJ, Rossignol DP. Inhibition of endotoxin response by e5564, a novel Toll-like receptor 4-directed endotoxin antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1093–1102. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.044487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitazawa T, Tsujimoto T, Kawaratani H, Fukui H. Salvage effect of E5564, Toll-like receptor 4 antagonist on d-galactosamine and lipopolysaccharide-induced acute liver failure in rats. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1009–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Correll PH, Morrison AC, Lutz MA. Receptor tyrosine kinases and the regulation of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:731–737. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Racanelli V, Rehermann B. The liver as an immunological organ. Hepatology. 2006;43:S54–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.21060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J, Meng Z, Jiang M, Zhang E, Trippler M, Broering R, Bucchi A, Krux F, Dittmer U, Yang D, Roggendorf M, Gerken G, Lu M, Schlaak JF. Toll-like receptor-induced innate immune responses in non-parenchymal liver cells are cell type-specific. Immunology. 2010;129:363–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ju C, Reilly TP, Bourdi M, Radonovich MF, Brady JN, George JW, Pohl LR. Protective role of Kupffer cells in acetaminophen-induced hepatic injury in mice. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:1504–1513. doi: 10.1021/tx0255976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campion SN, Johnson R, Aleksunes LM, Goedken MJ, van Rooijen N, Scheffer GL, Cherrington NJ, Manautou JE. Hepatic Mrp4 induction following acetaminophen exposure is dependent on Kupffer cell function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G294–304. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00541.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee WM, Squires RH, Jr, Nyberg SL, Doo E, Hoofnagle JH. Acute liver failure: Summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2008;47:1401–1415. doi: 10.1002/hep.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR, Potter WZ, Davis DC, Gillette JR, Brodie BB. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. II. Role of covalent binding in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973;187:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rai RM, Yang SQ, McClain C, Karp CL, Klein AS, Diehl AM. Kupffer cell depletion by gadolinium chloride enhances liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in rats. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:G909–918. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.270.6.G909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asaduzzaman M, Zhang S, Lavasani S, Wang Y, Thorlacius H. LFA-1 and MAC-1 mediate pulmonary recruitment of neutrophils and tissue damage in abdominal sepsis. Shock. 2008;30:254–259. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318162c567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malhi H, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Gores GJ. Free fatty acids induce JNK-dependent hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12093–12101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamaki N, Hatano E, Taura K, Tada M, Kodama Y, Nitta T, Iwaisako K, Seo S, Nakajima A, Ikai I, Uemoto S. CHOP deficiency attenuates cholestasis-induced liver fibrosis by reduction of hepatocyte injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G498–505. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00482.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smedsrod B, Pertoft H, Eggertsen G, Sundstrom C. Functional and morphological characterization of cultures of Kupffer cells and liver endothelial cells prepared by means of density separation in Percoll, and selective substrate adherence. Cell Tissue Res. 1985;241:639–649. doi: 10.1007/BF00214586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, Reisch JS, Schiodt FV, Ostapowicz G, Shakil AO, Lee WM. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2005;42:1364–1372. doi: 10.1002/hep.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiodt FV, Larson A, Davern TJ, Han SH, McCashland TM, Shakil AO, Hay JE, Hynan L, Crippin JS, Blei AT, Samuel G, Reisch J, Lee WM. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947–954. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, Schwabe RF. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seki E, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptors and adaptor molecules in liver disease: update. Hepatology. 2008;48:322–335. doi: 10.1002/hep.22306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhai Y, Qiao B, Shen XD, Gao F, Busuttil RW, Cheng G, Platt JL, Volk HD, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Evidence for the pivotal role of endogenous toll-like receptor 4 ligands in liver ischemia and reperfusion injury. Transplantation. 2008;85:1016–1022. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181684248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paik YH, Schwabe RF, Bataller R, Russo MP, Jobin C, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2003;37:1043–1055. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogushi I, Iimuro Y, Seki E, Son G, Hirano T, Hada T, Tsutsui H, Nakanishi K, Morishita R, Kaneda Y, Fujimoto J. Nuclear factor kappa B decoy oligodeoxynucleotides prevent endotoxin-induced fatal liver failure in a murine model. Hepatology. 2003;38:335–344. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffmann F, Sass G, Zillies J, Zahler S, Tiegs G, Hartkorn A, Fuchs S, Wagner J, Winter G, Coester C, Gerbes AL, Vollmar AM. A novel technique for selective NF-kappaB inhibition in Kupffer cells: contrary effects in fulminant hepatitis and ischaemia-reperfusion. Gut. 2009;58:1670–1678. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.165647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong L, Zuo L, Xia S, Gao S, Zhang C, Chen J, Zhang J. Reduction of liver tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression by targeting delivery of antisense oligonucleotides into Kupffer cells protects rats from fulminant hepatitis. J Gene Med. 2009;11:229–239. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li JD, Peng Y, Peng XY, Li QL, Li Q. Suppression of nuclear factor-kappaB activity in Kupffer cells protects rat liver graft from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:1582–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]