Abstract

ER stress triggers myocardial contractile dysfunction while effective therapeutic regimen is still lacking. Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2), an essential mitochondrial enzyme governing mitochondrial and cardiac function, displays distinct beneficial effect on the heart. This study was designed to evaluate the effect of ALDH2 on ER stress-induced cardiac anomalies and the underlying mechanism involved with a special focus on autophagy. WT and ALDH2 transgenic mice were subjected to the ER stress inducer thapsigargin (1 mg/kg, i.p., 48 hrs). Echocardiographic, cardiomyocyte contractile and intracellular Ca2+ properties as well as myocardial histology, autophagy and autophagy regulatory proteins were evaluated. ER stress led to compromised echocardiographic indices (elevated LVESD, reduced fractional shortening and cardiac output), cardiomyocyte contractile and intracellular Ca2+ properties and cell survival, associated with upregulated autophagy, dampened phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream signal molecules TSC2 and mTOR, the effects of which were alleviated or mitigated by ALDH2. Thapsigargin promoted ER stress proteins Gadd153 and GRP78 without altering cardiomyocyte size and interstitial fibrosis, the effects of which were unaffected by ALDH2. Treatment with thapsigargin in vitro mimicked in vivo ER stress-induced cardiomyocyte contractile anomalies including depressed peak shortening and maximal velocity of shortening/relengthening as well as prolonged relengthening duration, the effect of which was abrogated by the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine and the ALDH2 activator Alda-1. Interestingly, Alda-1-induced beneficial effect against ER stress was obliterated by autophagy inducer rapamycin, Akt inhibitor AktI and mTOR inhibitor RAD001. These data suggest a beneficial role of ALDH2 against ER stress-induced cardiac anomalies possibly through autophagy reduction.

Keywords: ER stress, ALDH2, autophagy, Akt, TSC, mTOR, cardiomyocyte mechanics

1. INTRODUCTION

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is comprised of an extensive intracellular membranous network governing intracellular Ca2+ storage, glycosylation, trafficking of membrane and secretory proteins, as well as lipid and cholesterol biosynthesis. Perturbations of these biological processes through energy deprivation, infection, expression of mutant proteins incompatible for folding, and increased protein trafficking interfere with the proper functioning of ER, leading to a condition called ER stress [1-4]. Three classes of ER stress transducers have been demonstrated including inositol-requiring protein-1 (IRE1), the protein kinase RNA (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK)-translation initiation factor eIF-2α pathway and transcription factor-6 (ATF6) [3-5]. Although ER stress serves as an unique defense machinery against external insult, excessive ER stress often facilitates an array of pathological responses in obesity, diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders, alcoholism and heart diseases through inappropriate activation of a complex signaling network namely unfolded protein response (UPR) [5-10]. Pharmacological maneuvers capable of alleviating ER stress through chemical chaperone properties such as tauroursodeoxycholic acid are proven to be beneficial in the management of insulin resistance and cardiovascular diseases [2,4,6]. However, the precise mechanism(s) behind ER stress-induced cardiovascular anomalies has not been fully elucidated, thus making it somewhat difficult to identify therapeutic targets for non-chemical chaperon intervention against ER stress-induced pathologic changes.

In an effort to better understand ER stress-induced cardiac anomalies, this study was designed to evaluate the effect of the mitochondrial enzyme mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) in ER stress-induced cardiac pathological changes. We took advantage of a unique transgenic murine model of global ALDH2 overexpression to examine the ER stress inducer thapsigargin-triggered cardiac morphological, contractile and intracellular Ca2+ anomalies. ALDH2 is a human gene located on chromosome 12. Caucasians are homozygous for ALDH2 while ~40% of Asians, East Europeans and African Americans possess one normal copy of the ALDH2 gene and one mutant copy encoding an inactive mitochondrial isozyme [11,12]. Recent evidence from our laboratory and others has depicted an essential role of ALDH2 in the regulation of cardiac homeostasis in diabetes, alcoholism, and ischemia-reperfusion injury [13-19]. Interestingly, ALDH2 deficiency was found to aggravate ER stress-induced cardiac dysfunction possibly via NADPH-mediated cell death [20] although the precise mechanism(s) of action remains to be elucidated. Further findings from our group have demonstrated an essential role of autophagy, a conserved pathway for bulk degradation of intracellular proteins and organelles, in ALDH2-offered cardioprotection [14,21]. To this end, autophagy and autophagy regulatory cell signaling cascades including Akt and its downstream molecules the tumor suppress gene tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [22] were scrutinized in murine hearts from wild type (WT) and ALDH2 transgenic mice following thapsigargin challenge.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1 ALDH2 transgenic mice and in vivo ER stress

All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wyoming (Laramie, WY). Production of ALDH2 overexpression transgenic mice using the chicken β-actin promoter was described previously [23]. Five to six month-old male FVB wild type and ALDH2 transgenic mice were maintained with a 12/12-light/dark cycle with free access to tap water. To elicit ER stress in vivo, mice were injected with thapsigargin, an inhibitor of ER-specific Ca2+-ATPase (1 mg/kg) for 48 hrs prior to assessment of myocardial function and cell signaling protein expression [24,25].

2.2 ALDH2 activity

ALDH2 activity was measured in 33 mM sodium pyrophosphate containing 0.8 mM NAD+, 15 μM propionaldehyde and 0.1 ml myocardial protein extract. Propionaldehyde, the substrate of ALDH2, was oxidized in propionic acid, while NAD+ was reduced to NADH to estimate ALDH2 activity. NADH was determined by spectrophotometric absorbance at 340 nm. ALDH2 activity was expressed as nmol NADH/min per mg protein [16].

2.3 Isolation of cardiomyocytes and induction of ER stress in vitro

Hearts were rapidly removed from anesthetized (ketamine 80 mg/kg and xylazine 12 mg/kg i.p.) mice and mounted onto a temperature-controlled (37°C) Langendorff system. After perfusing with a modified Tyrode’s solution (Ca2+ free) for 2 min, the heart was digested with a Ca2+-free KHB buffer containing liberase blendzyme 4 (Hoffmann-La Roche Inc., Indianapolis, IN) for 20 min. The modified Tyrode solution (pH 7.4) contained the following (in mM): NaCl 135, KCl 4.0, MgCl2 1.0, HEPES 10, NaH2PO4 0.33, glucose 10, butanedione monoxime 10, and solution was gassed with 5% CO2-95% O2. Left ventricle was cut into small pieces in a modified Tyrode’s solution. Tissue pieces were gently agitated and pellet of cells was resuspended. Extracellular Ca2+ was added incrementally back to 1.20 mMn. A yield of 50–60% viable rod-shaped cells with clear sacromere striations was achieved. Cardiomyocytes with obvious sarcolemmal blebs or spontaneous contraction were not chosen for mechanical examination [23]. To induce ER stress, murine cardiomyocytes were incubated with thapsigargin (3 μM) for 6 hrs [25] prior to assessment of mechanical and protein properties. To directly assess the role of autophagy, Akt and mTOR/TSC signaling in ER stress-induced cardiomyocyte dysfunction, cardiomyocytes were incubated with thapsigargin (3 μM) in the absence or presence of the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA, 10 mM) [26], the autophagy inducer rapamycin (5 μM) [21], the ALDH2 activator Alda-1 (20 μM) [21] or the Akt inhibitor AktI (1 μM) [27] or the mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (10 nM) [28] prior to mechanical assessment.

2.4 Echocardiographic assessment

Cardiac geometry and function were evaluated in anesthetized mice using a 2-D guided M-mode echocardiography (Sonos 5500, Phillips Medical System, Andover, MA) equipped with a 15-6 MHz linear transducer. Left ventricular (LV) wall thickness, diastolic and systolic dimensions were recorded from the M-mode images. Fractional shortening was calculated from end-diastolic diameter (EDD) and end-systolic diameter (ESD) using the equation of (EDD-ESD)/EDD x100%. Estimated echocardiographic LV mass was calculated as [(LVEDD + septal wall thickness + posterior wall thickness)3-LVEDD3]*1.055, where 1.055 (mg/mm3) represents the density of myocardium. Heart rate was calculated from 10 consecutive cardiac cycles. Cardiac output was calculated from LV end-diastolic and -systolic diameters using the equation [(LVEDD)3-(LVESD)3] × heart rate [29].

2.5 Cell shortening/relengthening

Mechanical properties of cardiomyocytes were assessed using a SoftEdge MyoCam® system (IonOptix Corporation, Milton, MA). In brief, cells were placed in a Warner chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Olympus, IX-70) and superfused (~1 ml/min at 25°C) with a buffer containing (in mM): 131 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, at pH 7.4. The cells were field stimulated with supra-threshold voltage at a frequency of 0.5 Hz (unless otherwise stated), 3 msec duration, using a pair of platinum wires placed on opposite sides of the chamber connected to a FHC stimulator (Brunswick, NE). The myocyte being studied was displayed on the computer monitor using an IonOptix MyoCam camera. An IonOptix SoftEdge software was used to capture changes in cell length during shortening and relengthening. Cell shortening and relengthening were assessed using the following indices: peak shortening (PS) - indicative of ventricular contractility, time-to-PS (TPS) - indicative of contraction duration, and time-to-90% relengthening (TR90) - represents relaxation duration, maximal velocities of shortening (+ dL/dt) and relengthening (− dL/dt) - indicatives of maximal velocities of ventricular pressure rise/fall [23].

2.6 Intracellular Ca2+ transient measurement

Myocytes were loaded with fura-2/AM (0.5 μM) for 10 min and fluorescence measurements were recorded with a dual-excitation fluorescence photomultiplier system (IonOptix). Cardiomyocytes were placed on an Olympus IX-70 inverted microscope and imaged through a Fluor × 40 oil objective. Cells were exposed to light emitted by a 75W lamp and passed through either a 360 or a 380 nm filter, while being stimulated to contract at 0.5 Hz. Fluorescence emissions were detected between 480 and 520 nm by a photomultiplier tube after first illuminating the cells at 360 nm for 0.5 sec then at 380 nm for the duration of the recording protocol (333 Hz sampling rate). The 360 nm excitation scan was repeated at the end of the protocol and qualitative changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration were inferred from the ratio of fura-2 fluorescence intensity (FFI) at two wavelengths (360/380). Fluorescence decay time was measured as an indication of the intracellular Ca2+ clearing rate. Both single and bi-exponential curve fit programs were applied to calculate the intracellular Ca2+ decay constant [23].

2.7 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Left ventricle was fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde/ 1.2% acrolein in a fixative buffer (0.1 M cacodylate, 0.1 M sucrose, pH 7.4) and 1% osmium tetroxide, followed by treatment with 1% uranyl acetate. The samples were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol concentrations before being embedded in LX112 resin (LADD Research Industries, Burlington, VT). Ultra-thin sections (~50 nm) were cut on ultramicrotome, stained with uranyl acetate, followed by lead citrate, and observed using a Hitachi H-7000 Transmission Electron Microscope equipped with a 4K × 4K cooled CCO digital camera (magnification ×20000) [30].

2.8 Histological examination

Hearts were harvested and sliced at mid-ventricular level followed by fixation with normal buffered formalin. Paraffin-embedded transverse sections were cut in 5-μm in thickness and stained with Masson trichrome. Sections were photographed with a 40× objective of an Olympus BX-51 microscope equipped with an Olympus MaguaFire SP digital camera. Five random fields from each section (3 sections per mouse) were assessed for fibrosis. To determine fibrotic area, pixel counts of blue stained fibers were quantified using Color range and Histogram commands in Photoshop. Fibrotic area was calculated by dividing the pixels of blue stained area to total pixels of non-white area [23].

2.9 MTT assay for cell viability

[3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] (MTT) assay is based on transformation of the tetrazolium salt MTT by active mitochondria to an insoluble formazan salt. Cardiomyocytes (with or without induction of ER stress) were plated in microtiter plate at a density of 3 × 105 cells/ml. MTT was added to each well with a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, and the plates were incubated for 2 hrs at 37°C. The formazan crystals in each well were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (150 μl/well). Formazan was quantified spectroscopically at 560 nm using a SpectraMax® 190 spectrophotometer [31].

2.10 Western blot analysis

Pellets of cardiomyocytes were sonicated in a lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and a protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein levels of the ER stress markers Gadd153 and GRP78, the apoptotic markers cleaved caspase-3 and caspase-12 (which is ER stress-specific), the autophagy marker Atg7, Beclin-1 and LC3B, the autophagy signaling molecules Akt, phosphorylated Akt (pAkt), TSC2, phosphorylated TSC2 (pTSC2), mTOR, phosphorylated mTOR (pmTOR) and GAPDH (loading control) were examined by immunoblotting. Membranes were probed with anti-ALDH2 (1:1,000), anti-Gadd153 (1:500), anti-GRP78 (1:1,000), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000), anti-caspase-12 (1;1,000), anti-Akt (1:1,000), anti-pAkt (Thr473, 1:1000), anti-TSC2 (1:1,000), anti-pTSC2 (Ser939, 1:1,000), anti-mTOR (1:1,000), anti-pmTOR (Ser2448, 1:1,000) and anti-GAPDH (1;2,000) antibodies. Monoclonal antibody to ALDH2 was a generous gift from Dr. Henry Weiner, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN. The anti-Gadd153 antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and all other antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled secondary antibodies. After immunoblotting, the film was scanned and detected with a Bio-Rad Calibrated Densitometer [23].

2.11 Data analysis

Data were Mean ± SEM. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was estimated by one-way analysis of variation (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Effect of ER stress and ALDH2 on biometric and echocardiographic properties

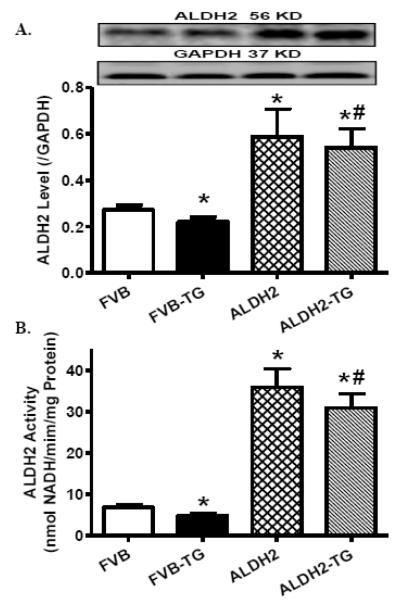

To examine the impact of ER stress and ALDH2 on myocardial contractile function, FVB and ALDH2 transgenic mice were challenged with thapsigargin (1 mg/kg, i.p.) for 48 hrs [24,25] prior to assessment of echocardiographic properties. Neither thapsigargin nor ALDH2 transgene significantly affected body and organ (heart, liver and kidney) weights as well as systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Our data depicted that thapsigargin significantly increased LVESD, suppressed fractional shortening and cardiac output without affecting heart rate, LVEDD, echocardiographically calculated and normalized LV mass (to body weight). While ALDH2 overexpression did not elicit any overt effect on echocardiographic parameters tested, it mitigated thapsigargin-induced changes in echocardiographic indices (Table 1). Last but not least, ER stress induction triggered a subtle but significant decrease in both ALDH2 expression and enzymatic activity, the effects of which were masked by ALDH2 overexpression (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Biometric and echocardiographic parameters of FVB and ALDH2 mice with ER stress

| Parameter | FVB | FVB-TG | ALDH2 | ALDH2-TG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Weight (g) | 28.1 ± 1.1 | 27.2 ± 0.8 | 27.3 ± 0.8 | 27.2 ± 0.7 |

| Heart Weight (mg) | 139 ± 3 | 138 ± 4 | 139 ± 4 | 140 ± 3 |

| Heart/Body Weight (mg/g) | 4.97 ± 0.12 | 5.13 ± 0.21 | 5.12 ± 0.16 | 5.15 ± 0.09 |

| Liver Weight (g) | 1.39 ± 0.03 | 1.39 ± 0.03 | 1.39 ± 0.03 | 1.36 ± 0.02 |

| Kidney Weight (mg) | 360 ± 15 | 353 ± 12 | 355 ± 10 | 362 ± 10 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 77.1 ± 1.4 | 76.0 ± 1.8 | 76.6 ± 1.6 | 78.8 ± 1.8 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 115.9 ± 1.9 | 115.4 ± 1.5 | 116.3 ± 1.4 | 115.2 ± 2.5 |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 506 ± 17 | 496 ± 14 | 504 ± 11 | 489 ± 12 |

| LV Wall Thickness (mm) | 1.00 ± 0.03 | 1.00 ± 0.02 | 1.01 ± 0.02 | 1.02 ± 0.02 |

| LV ESD (mm) | 1.16 ± 0.05 | 1.36 ± 0.03* | 1.15 ± 0.03 | 1.17 ± 0.04# |

| LV EDD (mm) | 2.29 ± 0.06 | 2.23 ± 0.06 | 2.28 ± 0.05 | 2.29 ± 0.06 |

| Calculated LV Mass (mg) | 47.2 ± 2.4 | 46.7 ± 1.7 | 46.8 ± 1.6 | 47.3 ± 1.8 |

| Normalized LV Mass (mg/g) | 1.71 ± 0.11 | 1.74 ± 0.08 | 1.74 ± 0.09 | 1.70 ± 0.04 |

| Factional Shortening (%) | 49.4 ± 1.7 | 38.7 ± 1.2* | 48.9 ± O.8 | 48.9 ± 0.8# |

| Cardiac Output (mm3*min) | 5238 ± 255 | 4277 ± 277* | 5162 ± 255 | 5132 ± 347# |

TG: thapsigargin; LV: left ventricular; LV ESD: LV end systolic diameter; LV EDD: LV end diastolic diameter; Mean ± SEM, n = 12 mice per group

p < 0.05 vs. FVB group

p < 0.05 vs. FVB-TG group.

Fig. 1.

Effect of thapsigargin (TG, 1 mg/kg, i.p. for 48 hrs) on ALDH2 protein expression and enzymatic activity in hearts from FVB and ALDH2 transgenic mice. A: ALDH2 expression. Insets: Representative gel blots depicting level of ALDH2 using specific antibody (GAPDH was used as the loading control); and B: ALDH2 activity. Mean ± SEM, n = 6-7 hearts per group, * p < 0.05 vs. FVB group, # p < 0.05 vs. FVB-TG group.

3.2 Effect of ER stress and ALDH2 on cardiomyocyte contractile, ultrastructural and intracellular Ca2+ properties

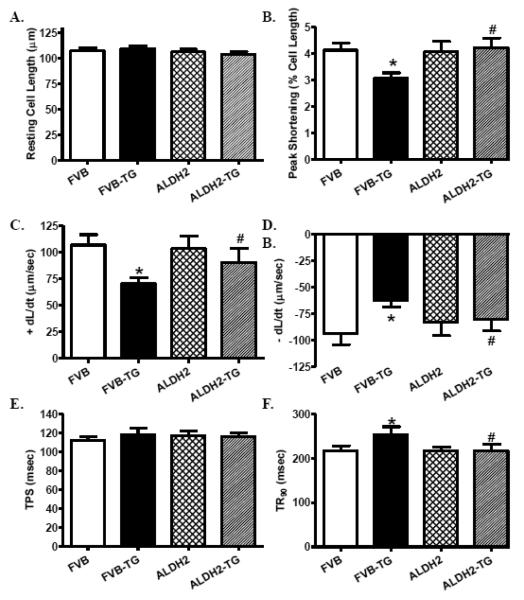

Neither thapsigargin nor ALDH2 transgene significantly affected resting cardiomyocyte cell length. ER stress induction significantly decreased peak shortening, maximal velocity of shortening and relengthening (± dL/dt) and prolonged time-to-90% relengthening (TR90) without affecting time-to-peak shortening (TPS), the effect of which was mitigated by ALDH2 transgene. ALDH2 overexpression did not elicit any overt effect on cardiomyocyte contractile properties (Fig. 2). To explore the possible underlying mechanism(s) behind ALDH2-induced beneficial effect against ER stress-induced cardiomyocyte mechanical defect, intracellular Ca2+ handling was assessed using fura-2 fluorescence technique. As shown in Fig. 3B-E, thapsigargin challenge significantly elevated baseline fura-2 fluorescence intensity (FFI), decreased rise of FFI in response to electrical stimuli (ΔFFI) and slowed intracellular Ca2+ decay rate (single and bi-exponential), the effects of which were abrogated by ALDH2. ALDH2 transgene did not affect intracellular Ca2+ properties in the absence of ER stress challenge. TEM examination revealed that ER stress triggered overt focal damage in myocardial tissue, as evidenced by disorganized myofibrils and loss of mitochondrial cristae. ALDH2 transgene effectively alleviated ER stress-induced ultrastructural changes without eliciting any notable effect by itself (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 2.

Effect of the ER stress inducer thapsigargin (TG, 1 mg/kg, i.p., 48 hrs) on cardiomyocyte contractile properties in FVB and ALDH2 transgenic mice. A: Resting cell length; B: Peak shortening (% of cell length); C: Maximal velocity of shortening (+ dL/dt); D: Maximal velocity of relengthening (− dL/dt); E: Time-to-peak shortening (TPS); and F: Time-to-90% relengthening (TR90). Mean ± SEM, n = 87 cells from 3 mice per group, * p < 0.05 vs. FVB group; # p < 0.05 vs. FVB-TG group.

Fig. 3.

Effect of thapsigargin (TG, 1 mg/kg, i.p., for 48 hrs) on myocardial ultrastructural and cardiomyocyte intracellular Ca2+ properties in FVB and ALDH2 mouse hearts. A: Transmission electron microscopic micrographs of left ventricular tissues; Normal myofilament and mitochondrial ultrastructure may be seen in FVB, ALDH2 and ALDH2-TG groups while FVB-TG group displays irregular and deformed myofibril structure. Original magnification=20,000; B: Baseline fura-2 fluorescence intensity (FFI); C: Electrically-stimulated increase in FFI (ΔFFI); D: Intracellular Ca2+ decay rate (single exponential); and E: Intracellular Ca2+ decay rate (bi-exponential). Mean ± SEM, n = 60 cells from 3 mice per group, * p < 0.05 vs. FVB group; # p < 0.05 vs. FVB-TG group.

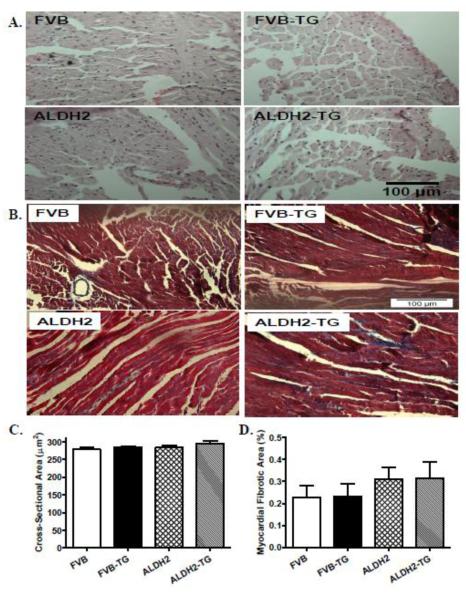

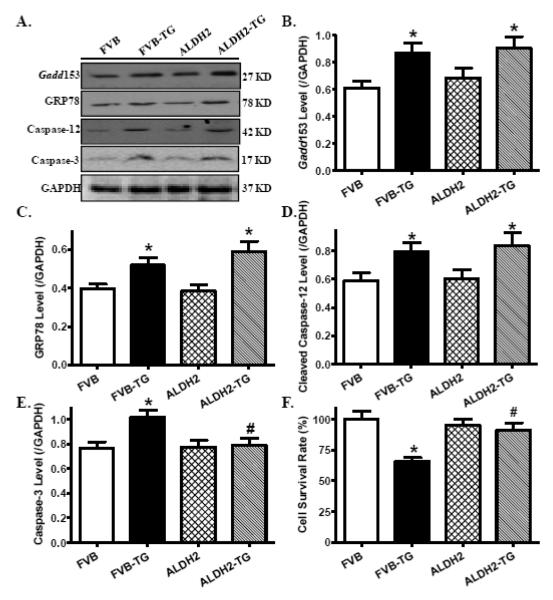

3.3 Effect of ER stress and ALDH2 on myocardial histology, ER stress and cell survival

To assess the impact of ALDH2 transgene on myocardial histology following ER stress induction, cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area and interstitial fibrosis were examined. Findings from H&E and Masson trichrome staining revealed that neither thapsigargin nor ALDH2 transgene affected cardiomyocyte transverse cross-sectional area or interstitial fibrosis (Fig. 4). To validate the ER stress model and evaluate cell survival following thapsigargin challenge, protein markers for ER stress and apoptosis as well as cell survival were evaluated using Western blot analysis and MTT assay. Our data shown in Fig. 5 revealed that thapsigargin challenge resulted in profound ER stress (as evidenced by levels of Gadd153, GRP78 and Caspase-12), apoptosis (shown in upregulated cleaved Caspase-3 levels) and cell death (MTT assay), the effect of which with the exception of ER stress protein markers was mitigated by ALDH2. ALDH2 transgene did not elicit any overt effect on ER stress, apoptosis and cell survival.

Fig. 4.

Effect of the ER stress inducer thapsigargin (TG, 1 mg/kg, i.p., for 48 hrs) on myocardial histological changes in WT and ALDH2 transgenic mice. A: Representative H&E micrographs depicting cross-sections of left ventricles (x 200) in FVB and ALDH2 transgenic mice; B: Representative Masson Trichrome micrographs showing longitudinal sections of left ventricles (x 400) in FVB and ALDH2 transgenic mice; C: Quantitative analysis of cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area from 46-49 fields per group; and D: Quantitative analysis of fibrotic area (Masson trichrome stained area in light blue color normalized to total myocardial area) from ~ 18 sections from 3 mice per group; Mean ± SEM, * p < 0.05 vs. FVB group, # p < 0.05 vs. FVB-TG group.

Fig. 5.

Effect of thapsigargin (TG, 1 mg/kg, i.p. for 48 hrs) on ER stress and cell death in FVB and ALDH2 transgenic mice. A: Representative gel blots depicting levels of the ER stress and apoptotic proteins Gadd153, GRP78, Caspase-12 and Caspase-3 using specific antibodies (GAPDH was used as the loading control); B: Gadd153; C: GRP78; D: Cleaved Caspase-12; E: Cleaved Caspase-3; and F: Cell survival using MTT assay; Mean ± SEM, n = 8-15 hearts (4 for MTT assay) per group, * p < 0.05 vs. FVB group, # p < 0.05 vs. FVB-TG group.

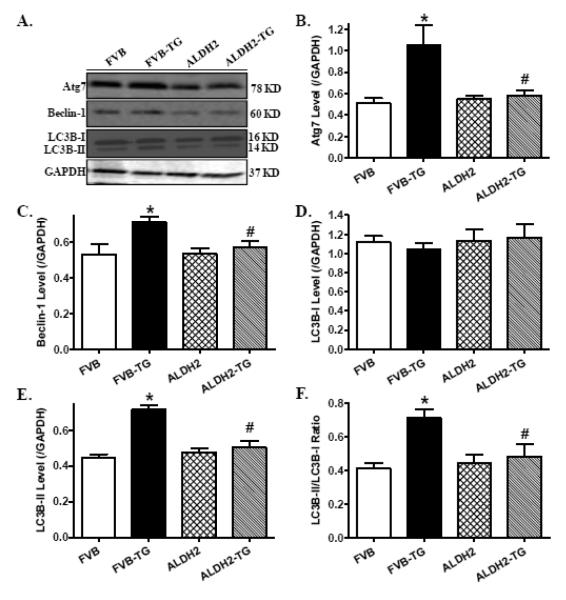

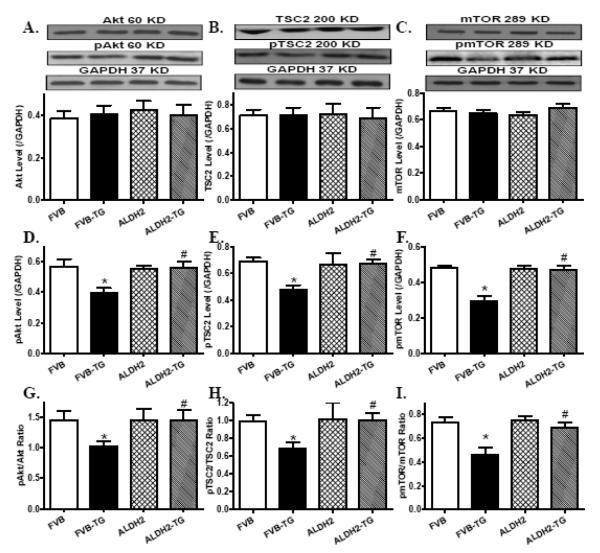

3.4 Effect of ER stress and ALDH2 on autophagy and autophagy signaling molecules

Western blot analysis revealed that ER stress induction with thapsigargin facilitated autophagy as evidenced by levels of Atg7, Beclin-1 and LC3BI to LC3BII conversion. Although ALDH2 transgene did not elicit any notable effect on autophagy protein markers, it ablated thapsigargin-induced autophagic responses (Fig. 6). Further examination of autophagy signaling molecules revealed that thapsigargin challenge suppressed phosphorylation of Akt, TSC2 and mTOR (absolute or normalized values), the effect of which was mitigated by ALDH2 transgene. Neither thapsigargin nor ALDH2 transgene affected total protein expression of Akt and its downstream signaling molecules TSC2 and mTOR (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Effect of thapsigargin (TG, 1 mg/kg, i.p. for 48 hrs) on autophagy in FVB and ALDH2 transgenic mice. A: Representative gel blots depicting levels of the autophagy markers Atg7, Beclin-1 and LC3B-I/II using specific antibodies (GAPDH was used as the loading control); B: Atg7; C: Beclin-1; D: LC3B-I; E: LC3B-II; and F: LC3B-II-to-LC3B-I ratio; Mean ± SEM, n = 6-7 hearts per group, * p < 0.05 vs. FVB group, # p < 0.05 vs. FVB-TG group.

Fig. 7.

Effect of thapsigargin (TG, 1 mg/kg, i.p. for 48 hrs) on Akt, TSC2 and mTOR signaling cascades in myocardium from FVB and ALDH2 transgenic mice. A: Akt; B: TSC2; C: mTOR; D: Phosphorylated Akt (pAkt); E: Phosphorylated TSC2 (pTSC2); F: Phosphorylated mTOR (pmTOR); G: pAkt-to-Akt ratio; H: pTSC2-to-TSC2 ratio; and I: pmTOR-to-mTOR ratio. Insets: Representative gel blots depicting levels of total and phosphorylated Akt, TSC2 and mTOR using specific antibodies (GAPDH was used as the loading control). Mean ± SEM, n = 6-7 hearts per group, * p < 0.05 vs. FVB group, # p < 0.05 vs. FVB-TG group.

3.5 Effect of activation of ALDH2 and autophagy as well as inhibition of autophagy, Akt and mTOR on ER stress-induced cardiomyocyte dysfunction

Given that the above observations are not necessarily casual with respect to the role of autophagy in ER stress-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction, murine cardiomyocytes from WT mice were challenged with thapsigargin (3 μM) for 6 hrs in the absence or presence of the autophagy inhibitor 3-MA (10 mM) [26], the autophagy inducer rapamycin (5 μM) [21], the ALDH2 activator Alda-1 (20 μM) [21], the Akt inhibitor AktI (1 μM) [27] or the mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (10 nM) [28] prior to mechanical assessment. While these pharmacological inhibitors or activators failed to elicit any notable effect on cardiomyocyte mechanical properties, 3-MA and Alda-1 effectively abrogated thapsigargin-induced cardiomyocyte contractile anomalies including reduced peak shortening amplitude and ± dL/dt as well as prolonged TR90. More intriguingly, rapamycin, AktI and RAD001 independently cancelled off Alda-1-induced beneficial effects against ER stress. Neither the resting cell length nor TPS was significantly affected by thapsigargin or the pharmacological regulators (Fig. 8). Neither thapsigargin nor the pharmacological inhibitors overtly affected ALDH2 expression. Nonetheless, thapsigargin incubation suppressed ALDH2 enzymatic activity. The ALDH2 activator Alda-1 significantly increased ALDH2 activity, the effect of which was partially dampened by thapsigargin regardless of the presence of AktI, rapamycin or RAD001 (Supplemental Fig. 1). These findings strongly favor a role of autophagy in ER stress-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction, and more importantly, a role of Akt-mTOR-mediated autophagy regulatory machinery in Alda-1-elicited protection against ER stress-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction.

Fig. 8.

Role of autophagy, Akt and TSC signaling in thapsigargin (TG)-induced inhibition of cardiomyocyte shortening. Isolated murine cardiomyocytes from FVB mice were incubated with TG (3 μM) for 5-6 hrs in the absence or presence of the autophagy inhibitor 3-methlyadenine (3-MA, 10 mM) or the ALDH2 activator alda-1 (20 μM) prior to assessment of mechanical properties. A cohort of TG-incubated cardiomyocytes were treated with alda-1 in the presence of the autophagy inducer rapamycin (5 μM), the Akt inhibitor AktI (1 μM) or the TSC inhibitor RAD001 (10 nM). A: Resting cell length; B: Peak shortening (% of resting cell length); C: Maximal velocity of shortening (+ dL/dt); D: Maximal velocity of relengthening (− dL/dt); E: Time-to-peak shortening (TPS); and F: Time-to-90% relengthening (TR90). Mean ± SEM, n = 54 – 56 cells per group, *p < 0.05 vs. control group; #p < 0.05 vs. TG group.

4. DISCUSSION

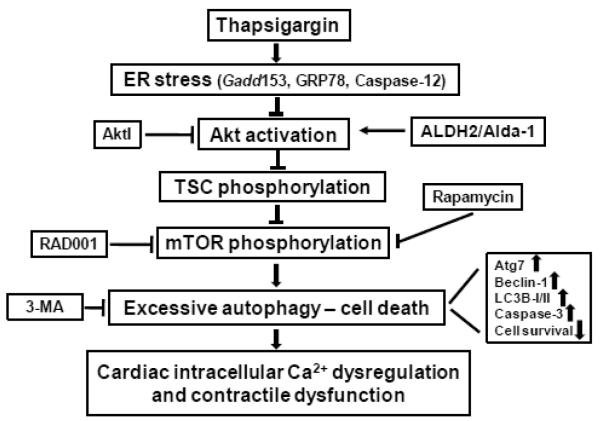

The salient findings of our study revealed that thapsigargin triggered ER stress, decreased ALDH2 enzymatic activity, impaired morphology, echocardiographic, cardiomyocyte contractile, intracellular Ca2+ properties and promoted cell death along with enhanced autophagy induction. Intriguingly, the mitochondrial enzyme ALDH2 effectively rescued against ER stress-induced cardiac ultrastructural, contractile and intracellular Ca2+ anomalies, apoptosis and autophagy induction in conjunction with restored phosphorylation of Akt and the Akt downstream signaling molecules TSC2 and mTOR. Our findings further revealed that the ALDH2 activator Alda-1-offered cardioprotection against ER stress may be negated by autophagy induction or inhibition of Akt and mTOR, suggesting a casual role of the Akt-TSC-mTOR-regulated autophagy in thapsigargin- and ALDH2-induced myocardial responses. Given that ALDH2 transgene did not affect thapsigargin-induced ER stress status (as evidenced by the ER stress protein markers Gadd153, GRP78 and Caspase-12), our data favor a role of autophagy (as opposed to ER stress regulation) in ALDH2-offered myocardial benefit against ER stress-induced cardiac pathologies as elaborated in our proposed scheme (Fig. 9). The involvement of Akt in ALDH2-mediated cardioprotection in ER stress was further substantiated by the finding that inhibition of Akt or its downstream signaling molecule mTOR nullified Alda-1-induced beneficial effect against thapsigargin. Take together, these data have prompted for a role of autophagy possibly through Akt/TSC/mTOR-dependent regulation in ALDH2-offered cardioprotection against ER stress.

Fig. 9.

Schematic diagram depicting possible mechanism(s) involved in ER stress- and ALDH2-induced changes in cardiac contractile function. ER stress triggers cardiac contractile dysfunction through suppression of Akt/TSC/mTOR signaling to upregulate autophagy. ALDH2 or the ALDH2 activator Alda-1 preserves activation of Akt/TSC/mTOR signaling cascade to suppress autophagy, en route to cardioprotection. Arrows denote stimulation whereas the lines with a “T” ending represent inhibition. ER: endoplasmic reticulum; TSC: tuber sclerosis complex; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; ALDH2: mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. AktI: Akt inhibitor; RAD001: mTOR inhibitor; 3-MA: 3-methyladenine which inhibits autophagy.

Compromised myocardial contractile function such as compromised cardiac contractility and prolonged diastolic duration are commonly seen in cardiac pathological conditions with ER stress [8-10,25,32-34]. Data from this study revealed that ER stress induction with thapsigargin directly results in diminished echocardiographic (enlarged LVESD, reduced fractional shortening and cardiac output), cardiomyocyte contractile function (reduced peak shortening and maximal velocity of shortening/relengthening, prolonged relengthening duration), consistent with previous findings using a similar murine model of ER stress [25]. Furthermore, our results noted elevated resting intracellular Ca2+ levels, decreased intracellular Ca2+ rise in response to electrical-stimulus and delayed intracellular Ca2+ clearance in thapsigargin-treated mice, indicating a role of intracellular Ca2+ mishandling in ER stress-triggered cardiac contractile dysfunction. TEM examination revealed focal myocardial ultrastructural damage following ER stress in the absence of overt histological aberration (cardiomyocyte size and interstitial fibrosis), probably as a result of relatively short duration of ER stress challenge. These ER stress-induced morphological and functional aberrations in murine hearts seen in our present study are consistent with the previous findings in cardiac pathological conditions where ER stress is abundant [7-10,34-36]. These findings have helped to consolidate a role of ER stress in compromised cardiac morphology and function under pathological conditions including cardiac hypertrophy, hypertension, ischemia-reperfusion injury, alcoholism and sepsis [5,35,36]. Our data also depicted apoptosis and reduced cell survival in thapsigargin-treated mice, suggesting a role of apoptosis in ER stress-induced cardiac morphological, contractile and intracellular Ca2+ anomalies, consistent with the previous notion for a role of apoptosis in ER stress-induced cellular damage [25]. Furthermore, our data displayed overt autophagy induction (Atg7, Beclin-1 and LC3BII) in murine hearts associated with dampened phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream signaling molecules TSC2 and mTOR following ER stress challenge. These data, in conjunction with the fact that autophagy inhibition reversed thapsigargin-induced cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction, favor a role of autophagy induction in ER stress-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction. ER stress is known to promote autophagy under pathological conditions such as diabetes and ischemia-reperfusion [37]. UPR under ER stress is capable of upregulating the expression of autophagy genes, activation of Atg1 kinase and Atg-dependent autophagy. The ER stress transducer IRE1, but unlikely PERK-eIF-2α and ATF6, has been demonstrated to link UPR to autophagy [37]. Although the pro-survival effect of autophagy may initially help to the removal of unfolded proteins in ER stress, excessive autophagy following ER stress may be maladaptive and detrimental. Inhibition of mTOR serves as a major gate keeper for autophagy induction. In particular, the tumor suppresser TSC2 mediates Akt phosphorylation-mediated mTOR phosphorylation (activation) and subsequently suppression of autophagy [22]. Our data demonstrated lessened phosphorylation of Akt-TSC2, en route to dampened mTOR phosphorylation (activation) and then excess autophagy following thapsigargin challenge, indicating a role of Akt-mTOR-mediated autophagy induction in ER stress-induced cardiac anomalies. This is in line with a recent report where ER stress induction may promote autophagy in mouse embryonic fibroblasts through negative regulation of the Akt-TSC-mTOR signaling cascade [38].

Perhaps the most intriguing finding from our current study is that ALDH2 mitigated ER stress-induced cardiac morphological, contractile and intracellular Ca2+ defects, apoptosis and autophagy induction. This observation, in conjunction with the improved phosphorylation of Akt, TSC2 and mTOR in ALDH2 transgenic mice under ER stress, favors a role of Akt activation and subsequently phosphorylation TSC2 and mTOR in suppression of autophagy and preservation of cardiac morphology, contractile function, intracellular Ca2+ handling and cell survival against ER stress. Our data revealed that ALDH2 transgene was capable of restoring ER stress-ameliorated Akt activation while Akt inhibition or autophagy induction using rapamycin negated ALDH2-offered cardioprotection against ER stress. These data favor a likely role of Akt activation and autophagy inhibition in ALDH2-offered beneficial effect against ER stress. The observation that TSC-mTOR inhibitor RAD001 nullified while autophagy inhibition mimicked Alda-1/ALDH2-induced beneficial effect further consolidates a role of mTOR-governed autophagy regulation in ALDH2-offered cardioprotection (as depicted in Fig. 9). In order to better discern the offsetting effect of pharmacological inhibitors on Alda-1-induced responses, least effective concentrations without overt mechanical effects themselves were chosen for AktI and RAD001. Our in vitro result revealed that thapsigargin partially dampened Alda-1-induced rise in ALDH2 activity, consistent with the downregulated ALDH2 level following in vivo thapsigargin challenge. The lack of change in ALDH2 protein expression in cell culture may be related to the relatively short ER stress exposure. Our data revealed that ALDH2 transgene itself did not affect cardiomyocyte morphology, mechanical and intracellular Ca2+ properties as well as cell survival and autophagy, suggesting that this mitochondrial enzyme may not be innately harmful for myocardial morphology and function. Last but not least, ALDH2 failed to alter the ER stress status following thapsigargin challenge, indicating that the beneficial role of ALDH2 against thapsigargin challenge does not occur through direct neutralizing effect of ER stress. Our data revealed that ALDH2 transgene ameliorated ER stress-induced intracellular Ca2+ defects, which may be a result of either ER stress induction or autophagy initiation. Give that ALDH2 failed to mitigate ER stress (evidenced by Gadd153, GRP78 and Caspase-12), the mitochondrial enzyme-offered beneficial effect on intracellular Ca2+ handling may likely be mediated through inhibition of autophagy rather than ER stress.

ER stress serves as a major mediator in a variety of cardiovascular diseases [1,5,35,36]. On the other hand, ALDH2 genetic polymorphism influences the prevalence, pathogenesis and clinical outcome of a number of heart diseases and treatment procedures [12,15-17,19,39,40]. Finding from our current study suggests that ALDH2 preserves the heart against ER stress possibly through alleviating Akt-TSC2-mTOR-regulated autophagy induction. Although our data may shed some light towards the interplay among ER stress, autophagy and ALDH2 genetic polymorphism in cardiac pathophysiology, the precise mechanism(s) of action behind ALDH2- and ER stress-mediated cardiac responses warrants further research. In particular, understanding of the signaling pathways controlling autophagy and the cellular fate in response to ER stress should hopefully open new possibilities for the management of numerous diseases related to ER stress.

Supplementary Material

Research highlights.

We examine the effect of ALDH2 in ER stress-induced cardiomyopathy;

ALDH2 overexpression alleviates ER stress-induced cardiac mechanical defect;

ALDH2 inhibits autophagy and restores phosphorylation of Akt and mTOR;

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH/NCRR P20 RR016474 and P20 GM103432 (JR).

Footnotes

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT None of the authors declare any conflict of interest associated with this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Kitakaze M, Tsukamoto O. What is the role of ER stress in the heart? Introduction and series overview. Circ. Res. 2010;107:15–18. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozcan U, Yilmaz E, Ozcan L, Furuhashi M, Vaillancourt E, Smith RO, Gorgun CZ, Hotamisligil GS. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science. 2006;313:1137–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1128294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deniaud A, Sharaf El DO, Maillier E, Poncet D, Kroemer G, Lemaire C, Brenner C. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces calcium-dependent permeability transition, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27:285–299. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glembotski CC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart. Circ. Res. 2007;101:975–984. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ni M, Lee AS. ER chaperones in mammalian development and human diseases. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3641–3651. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miki T, Miura T, Hotta H, Tanno M, Yano T, Sato T, Terashima Y, Takada A, Ishikawa S, Shimamoto K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic hearts abolishes erythropoietin-induced myocardial protection by impairment of phospho-glycogen synthase kinase-3beta-mediated suppression of mitochondrial permeability transition. Diabetes. 2009;58:2863–2872. doi: 10.2337/db09-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li SY, Gilbert SA, Li Q, Ren J. Aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) ameliorates chronic alcohol ingestion-induced myocardial insulin resistance and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okada K, Minamino T, Kitakaze M. [Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in hypertrophic and failing hearts] Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2005;126:385–389. doi: 10.1254/fpj.126.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okada K, Minamino T, Tsukamoto Y, Liao Y, Tsukamoto O, Takashima S, Hirata A, Fujita M, Nagamachi Y, Nakatani T, Yutani C, Ozawa K, Ogawa S, Tomoike H, Hori M, Kitakaze M. Prolonged endoplasmic reticulum stress in hypertrophic and failing heart after aortic constriction: possible contribution of endoplasmic reticulum stress to cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circulation. 2004;110:705–712. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137836.95625.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koppaka V, Thompson DC, Chen Y, Ellermann M, Nicolaou KC, Juvonen RO, Petersen D, Deitrich RA, Hurley TD, Vasiliou V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitors: a comprehensive review of the pharmacology, mechanism of action, substrate specificity, and clinical application. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012;64:520–539. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng GS, Yin SJ. Effect of the allelic variants of aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH2*2 and alcohol dehydrogenase ADH1B*2 on blood acetaldehyde concentrations. Hum. Genomics. 2009;3:121–127. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-3-2-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma H, Li J, Gao F, Ren J. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 ameliorates acute cardiac toxicity of ethanol: role of protein phosphatase and forkhead transcription factor. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54:2187–2196. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma H, Guo R, Yu L, Zhang Y, Ren J. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) rescues myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury: role of autophagy paradox and toxic aldehyde. Eur. Heart J. 2011;32:1025–1038. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Ren J. ALDH2 in alcoholic heart diseases: molecular mechanism and clinical implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;132:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Babcock SA, Hu N, Maris JR, Wang H, Ren J. Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) protects against streptozotocin-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy: role of GSK3beta and mitochondrial function. BMC. Med. 2012;10:40. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Budas GR, Disatnik MH, Mochly-Rosen D. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 in cardiac protection: a new therapeutic target? Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2009;19:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen CH, Budas GR, Churchill EN, Disatnik MH, Hurley TD, Mochly-Rosen D. Activation of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 reduces ischemic damage to the heart. Science. 2008;321:1493–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1158554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen CH, Sun L, Mochly-Rosen D. Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase and cardiac diseases. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010;88:51–57. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao J, Sun A, Xie Y, Isse T, Kawamoto T, Zou Y, Ge J. Aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 deficiency aggravates cardiac dysfunction elicited by endoplasmic reticulum stress induction. Mol. Med. 2012;18:785–793. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ge W, Guo R, Ren J. AMP-dependent kinase and autophagic flux are involved in aldehyde dehydrogenase-2-induced protection against cardiac toxicity of ethanol. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;51:1736–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doser TA, Turdi S, Thomas DP, Epstein PN, Li SY, Ren J. Transgenic overexpression of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 rescues chronic alcohol intake-induced myocardial hypertrophy and contractile dysfunction. Circulation. 2009;119:1941–1949. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.823799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Hiramatsu N, Kasai A, Du S, Takeda M, Hayakawa K, Okamura M, Yao J, Kitamura M. Rapid, transient induction of ER stress in the liver and kidney after acute exposure to heavy metal: evidence from transgenic sensor mice. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2055–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Ren J. Thapsigargin triggers cardiac contractile dysfunction via NADPH oxidase-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction: Role of Akt dephosphorylation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;51:2172–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 26.Guo R, Ren J. Deficiency in AMPK attenuates ethanol-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction through inhibition of autophagosome formation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012;94:480–491. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green CJ, Goransson O, Kular GS, Leslie NR, Gray A, Alessi DR, Sakamoto K, Hundal HS. Use of Akt inhibitor and a drug-resistant mutant validates a critical role for protein kinase B/Akt in the insulin-dependent regulation of glucose and system A amino acid uptake. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:27653–27667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Q, Simpson SE, Scialla TJ, Bagg A, Carroll M. Survival of acute myeloid leukemia cells requires PI3 kinase activation. Blood. 2003;102:972–980. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Hu N, Hua Y, Richmond KL, Dong F, Ren J. Cardiac overexpression of metallothionein rescues cold exposure-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction through attenuation of cardiac fibrosis despite cardiomyocyte mechanical anomalies. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;53:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turdi S, Han X, Huff AF, Roe ND, Hu N, Gao F, Ren J. Cardiac-specific overexpression of catalase attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction: role of autophagy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;53:1327–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.07.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Li Q, Yang X, Sreejayan N, Ren J. Insulin-like growth factor I deficiency prolongs survival and antagonizes paraquat-induced cardiomyocyte dysfunction: role of oxidative stress. Rejuvenation. Res. 2007;10:501–512. doi: 10.1089/rej.2007.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu HY, Okada K, Liao Y, Tsukamoto O, Isomura T, Asai M, Sawada T, Okuda K, Asano Y, Sanada S, Asanuma H, Asakura M, Takashima S, Komuro I, Kitakaze M, Minamino T. Ablation of C/EBP homologous protein attenuates endoplasmic reticulum-mediated apoptosis and cardiac dysfunction induced by pressure overload. Circulation. 2010;122:361–369. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.917914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo R, Ma H, Gao F, Zhong L, Ren J. Metallothionein alleviates oxidative stress-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and myocardial dysfunction. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrovski G, Das S, Juhasz B, Kertesz A, Tosaki A, Das DK. Cardioprotection by endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced autophagy. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2011;14:2191–2200. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doroudgar S, Glembotski CC. New concepts of endoplasmic reticulum function in the heart: Programmed to conserve. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasty AH, Harrison DG. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and hypertension - a new paradigm? J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:3859–3861. doi: 10.1172/JCI65173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoyer-Hansen M, Jaattela M. Connecting endoplasmic reticulum stress to autophagy by unfolded protein response and calcium. Cell Death. Differ. 2007;14:1576–1582. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qin L, Wang Z, Tao L, Wang Y. ER stress negatively regulates AKT/TSC/mTOR pathway to enhance autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:239–247. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.11062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H, Gong DX, Zhang YJ, Li SJ, Hu S. Effect of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 genotype on cardioprotection in patients with congenital heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:1606–1614. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu F, Chen Y, Lv R, Zhang H, Tian H, Bian Y, Feng J, Sun Y, Li R, Wang R, Zhang Y. ALDH2 genetic polymorphism and the risk of type II diabetes mellitus in CAD patients. Hypertens. Res. 2010;33:49–55. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.