Abstract

Each year a percentage of the 1.2 million men and women in the United States with a new diagnosis of colorectal cancer join the 700,000 people who have an ostomy. Education targeting the long term, chronic care of this population is lacking. This report describes the development of a Chronic Care Ostomy Self Management Program, which was informed by (1) evidence on published quality of life changes for cancer patients with ostomies, (2) educational suggestions from patients with ostomies, and (3) examination of the usual care of new ostomates to illustrate areas for continued educational emphases and areas for needed education and support. Using these materials, the Chronic Care Ostomy Self Management Program was developed by a team of multi-disciplinary researchers accompanied by experienced ostomy nurses. Testing of the program is in process. Pilot study participants reported high satisfaction with the program syllabus, ostomy nurse leaders, and ostomate peer buddies.

An estimated 1.2 milliion men and women in the United States are living with a previous diagnosis of colorectal cancer as of January, 2012.[42] Some of these survivors will end up with a temporary or permanent colostomy, and join the 700,000 plus people who have an ostomy.[2] An ostomy is a surgically created opening that allows for individuals with various medical conditions to eliminate wastes. While some ostomies in cancer patients may be intended to be temporary, circumstances require many patients to have an ostomy for months if not permanently.

The clinical need for ostomies for cancer patients is significant, but the changes in an individual’s quality of life and daily routine are extensive. Researchers have identified what people with ostomies face throughout their lives.[10, 12, 25] The impact includes physical, psychological, social and spiritual issues. Descriptive studies provide a foundation for developing and testing interventions for helping the post surgical ostomy patient adjust. The purposes of this report are to review evidence for the changes in Health-Related Quality of Life (HR-QOL) for patients with ostomies, list suggestions that patients with ostomies recommend to deal with these changes, describe usual care for new ostomates and outline a self-management program developed specifically to increase long term self-management for patients with ostomies.

Evidence for Quality of Life Changes in Patients with Ostomies

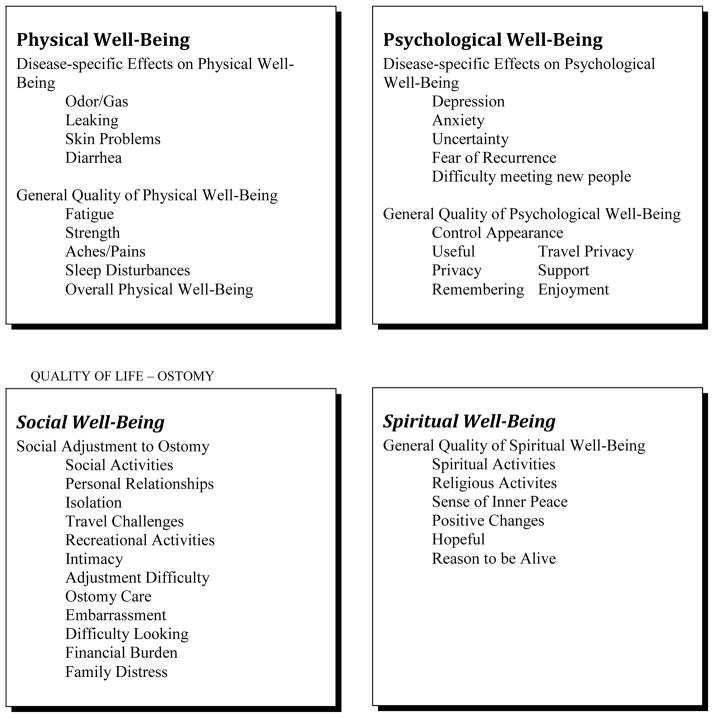

Many specific quality of life changes occur for patients with ostomies (ostomates). We used the City of Hope Quality of Life Model as a framework to describe their experiences (Figure 1). This model consists of four dimentsions: Physical Well Being and Functional Status, Psychological Well Being, Social Well Being and Spiritual Well Being. Issues were summarized from several large data sets collected from our patients with ostomies in order to create an intervention for patients.

Figure 1.

Quality-of-Life Ostomy

Our program of research includes three descriptive overlapping studies on the changes in the four dimensions of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) for patients with ostomies, along with two other domains that emerged during analysis: ostomy-specific concerns and healthcare-related issues. Methods used in each are summarized. Out first study involved establishing the reliability and validity of the City of Hope–Quality of Life-Ostomy Questionnaire (COH-QOL-O).[12] A mailed survey to the California members of the United Ostomy Association resulted in a 62% response rate (N = 1513). The four dimensional (Physical, Psychological, Social and Spiritual HR_QOL model was confirmed via factor analysis and reliability of the subscales ranged from 0.77 to 0.90. The population included bowel and urinary diversions, cancer and non cancer patients. Quality of life for 599 cancer and non cancer ostomy patients[25] and 307 patients with urinary diversions were reported.[9]

A second study involved a mixed-methods, case-control survey used to evaluate quality of life in male veterans with and without intestinal stomas. Cancer and non-cancer participants were accrued from Veterans Affairs Medical Centers in Tucson, Indianapolis, and Los Angeles.[22] Mailed surveys that included the COH-QOL-O questionnaire (for cases) and a modified COH-QOL questionnaire without ostomy specific items (for controls) and the SF36V for both groups were returned by 239 cases (155 with a colostomy and 83 with an ileostomy) and 272 controls. This represented a 68% response rate across the 3 sites.[24] Focus groups (n = 15) were used to further characterize barriers and concerns of the ostomy population. Focus group participants were study respondents from the highest and lowest quartile of overall QOL scores and used to compare those who have successfully adapted to those who remained extremely challenged with stomal issues. Groups were further divided into those with colostomies and those with ileostomies. Various aspects of HR-QOL reported by this Veterans population were published.[22, 7, 35, 20, 45, 4, 38, 21, 18, 40]

A third mixed-methods study was done with near-identical methods but focused on long-term (>5 years since diagnosis) colorectal cancer survivors. They were surveyed from a community-based health maintenance organization’s enrolled population in three sites (Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Northern California, and Hawaii). The mailed survey included a modified COH-QOL-O questionnaire and the SF-36v2, with an abridged version for the non-ostomy control subjects. Response rate was 52% (679/1308).[36] Focus groups of 34 cases were selected by HR-QOL high and low quartiles and divided by gender to provide in depth content augmenting the quantitative survey results. Additional information was obtained using a comprehensive socio-demographic and medical history obtained from each site’s automated information system. To date we have published on related symptoms (e.g. sleep disturbances), and health services challenges, such as complications, comorbidities, metastatic disease[36, 33, 31, 1, 3, 23, 41, 26, 34, 14, 17], and ostomy-specific challenges.[11, 44]

Results from our three studies are summarized below within HR-QOL domains. This analysis provided the foundation for the creation of a curriculum addressing identified patient concerns.

Physical Well Being

Cancer patients with ostomies experience initial and continuing physical needs related to their ostomy. They report fatigue and sleep disturbances related to the inability to find a comfortable-sleep position without having pouch leakage.[3] Dietary changes are also reported with trial and error approaches to discover what moves too quickly through the remaining bowel, what causes gas and odor, and what does not get digested.[13]

Ostomy-Specific Concerns

The challenges of carrying out daily ostomy care involve equipment decisions and trouble shooting, cleaning, skin care, and getting used to wearing a pouch and always carrying an “emergency kit”. Other ostomy-specific concerns include peristomal irritant dermatitis, gas, odor, leaking around the pouch, and stomal complications including prolapse, necrosis, stenosis, herniation and retraction.[10, 12, 25, 7, 35, 20, 45, 40, 33]

Psychological Well Being

Psychological needs are broad and may decrease over time depending on the ability of the patient to adapt.[22, 45, 4, 33] Common psychological problems reported include depression, feelings of uselessness, loss of control, changes in appearance, fear of recurrence, inability to cope, and increased privacy needs.[10, 12, 25, 22, 21, 33, 23]

Embarrassment is common and is most often found to be caused by noise, leakage and odor from the device.[25, 35, 40] The creation of an ostomy can change the degree of control an individual has over his or her own bodily function, thus presenting difficulties for an individual to engage in social, work, and intimate relationships. Our data have shown such challenges predispose ostomy patients to feelings of anxiety, depression, and social isolation.[33]

Social Well Being

Social interaction is clearly important to cancer survivors. It is this area of quality of life that most challenges both men and women who have ostomies.[33] Relationships, both sexual and non-sexual are impacted, with patients frequently feeling that they smell, carry a stigma and are repugnant to others. While there are limited studies addressing sexuality among ostomates, our studies have shown that having a stoma undermined ostomates’ body image and significantly decreased their sexual health.[25, 45, 23, 41, 14] Results of these studies indicate that a decrease in sexual health is influenced by physical problems of gas, odor, and leakage from the ostomy, sexual dysfunction due to surgery or illness, and decreased self-esteem and poor body image related to the look of the stoma or the loss of the capacity to function or perform as prior to surgery.

Some gender differences have been identified. While men reported worse social well being QOL than non-ostomy surgical patients, women reported lower QOL across overall QOL, psychological well-being and social well-being when compared to males.[23]

Some patients have difficulty going back to work.[18] For instance a grade school teacher relayed the difficulties in having to go to the restroom when her ostomy was evacuating, since she could not leave her class on a whim.[14] Other social challenges we have identified include isolation, difficulty looking at the ostomy, financial challenges, travel difficulties, changes in activities, and embarrassment during social events.[7, 33, 40, 21] Travel challenges were described by many with suggestions including carrying an emergency kit with extra supplies and clothes. Another suggestion was an empty bottle that could be filled with water for cleaning and flushing the pouch when immediate access to a water supply in public bathrooms was not available.[33, 14]

Spiritual Well Being

Of all the dimensions of quality of life, the spiritual well being dimension may be the most challenging for a patient with an ostomy. The meaning of life has changed, and some patients have reported having great difficulty accepting these changes.[4] Uncertainty about the future is common, and the reasons for being alive are challenged. Religion may provide comfort for some, and be rejected by others.[4]

Results from Other Studies

Other studies provide further evidence to support the findings from our research program. Within the psychological well being domain, studies have focused on coping styles, and support groups. One study reported that coping styles among patients with temporary ostomies were more likely to be ineffective, with escape avoidance as the primary strategy used.[8] Patients with permanent ostomies were more likely to incorporate planful problem solving, a more effective coping strategy.[8] Another study concluded that a support group is likely to be most effective if it includes encouragement and reinforcement, mutual respect among members, education regarding effective coping strategies, and discussion of experiences to allow for an emotional outlet and a sense of community among ostomates.[37]

Within the social well being domain, challenges with sexual intimacy have been reported. Some studies briefly address aspects of sexual intimacy as part of a large study of variables related to living with an ostomy. Manderson’s qualitative study, however, exclusively sought to identify and describe in-depth–often in the patients’ own words - the challenges ostomates face in negotiating their sexuality around their incontinence.[32] The strength of the Manderson study is its provision of rich descriptions of the sexual difficulties faced by ostomates. Such difficulties include a decrease in the sexual activity or perceptions of one’s own “sexiness” after creation of a stoma. Other difficulties included the adjustment of the ostomate’s partner to life with a stoma. Several participants described the loss of intimate relationships or the inability to establish new ones due to bodily self-consciousness and feelings of being abnormal. Other challenges included finding a balance between enjoying a sexual act while monitoring the device for leakage. These realistic descriptors of the sexual health challenges ostomates encounter may better assist providers in communicating with patients about their potential issues. Patients with ostomies have difficulty developing and keeping relationships, and sexual activity can be challenging because of changes in appearance, the potential for visibility of fecal material, and the loss of control that comes with sexual activity.[32, 50]

The needs of patients with ostomies cross all the four dimensions of quality of life: physical, psychological, social, and spiritual. Several of our studies have addressed adjustment and coping and the need for adequate psychological and social support from family and peers as well as effective patient education preoperatively and postoperatively. [33, 38, 21, 1, 40] Creating an educational support program for patients after surgery may increase adaptation, and help the patient create a new normal much quicker than trying to learn care solely by trial and error. In response, we have created a program that involves patients with ostomies, their caregiver/family member, and provides access to an ostomy buddy–so peer to peer report can enhance adjustment.

Focus Group Results

Both Study 2 (The VA Study), and Study 3 (Health Maintenance Organization Population) included qualitative data from focus group discussions. These data were transcribed, organized into quality of life domains using directed content analysis[19] by the authors. Representative sample examples are identified in Table 1 under the topics relevant to the development of a post operative intervention to help patients with ostomies adjust.

Table 1.

Program Recommendations from Focus Group Comments

| Topic | Comment |

|---|---|

| 1. Ostomy Nurse Involvement | It took me the better part of two years until I found this head ostomy nurse at my hospital. |

| I was having some kind of a problem remembering. And I called her up and she explained everything. They were real helpful. | |

| ET nurse is important. | |

| 2. Peer Supporter | A woman called me, who was also young, in my age range. And she gave me some different tips about what to do during sex, and what things she bought to cover it up with. She told me about taking something to help with odor problem, and I tried it for a while. Chlorophyl. |

| Oh, just the whole idea of adjusting to it–was really helpful, to have somebody who’d been through it, giving me some ideas about how she adapted to it–clothing-wise. Oh, she told me she wore jackets a lot. | |

| 3. Support Group / Peer Ostomate | Well, I think, this meeting earlier on, if you get a few people together maybe even before they discharge them from the hospital, and just let ‘em see that they’re not alone and that there are other people like them. I went out of here knowing that I wasn’t the only one with a colostomy. |

| I think they’re good for a lot of people for the simple reason that you’ve got a group of people… that have a lot of hints. Not medical, maybe, but things that have worked for them, and things to try, and that sort of thing. So I think it’s an asset. | |

| Most of those meetings for people, that have the ostomy are like a support meeting. Like they talk to each other and say, “Oh, yeah. How did you do this time? And have you been able to find a boyfriend? Or are you embarrassed to get undressed?” Especially with young people. | |

| If somebody’s going to have a colostomy put on, have a group session like this. I think it would definitely help a lot of people, especially if they’re young and single. | |

| 4. Becoming a Peer Supporter | I think it’s something that we all can give back to the community and to the people who have had colostomies. |

| I would say to them, “If you have any questions, or if I can be of any service to you, please give me a call.” I’d give them my number and my name and tell them, “Anytime you need me, call me.” | |

| People like us could volunteer to coach the person and tell them what to expect and things like that. | |

| I’d show them mine, and show what it is and how you do it. That’s what I would do if I had even a friend that would ask me, I would tell them. | |

| Spousal Support | My husband was very supportive. |

| I think my wife is the one that got me through the whole thing. I would have never ever made it. |

In summary, our results demonstrate that adjustment continues to be a challenge for many patients, while others adapt more successfully over time.[14] Contact with an ostomy nurse is consistently reported as most helpful in solving a variety of problems.[33, 38] Having someone who has an ostomy be available to counsel, talk with, and be a friend to a person with a new ostomy was also reported as very helpful, especially if the same gender is taken into consideration.[10, 23, 14] Such contacts increase the ability of the new ostomate to try different kinds of equipment, pick up hints of doing daily care from other patients and nurses, and talk through ways to establish and maintain relationships.

Usual Care for Ostomates

Approaches to teaching ostomates should begin preoperatively, and continue postoperatively in the hospital setting. The attending physician, nursing staff, and when available, an ostomy nurse are involved with this teaching. If possible, an ostomy nurse sees the patient preoperatively to identify the placement of the ostomy on the abdomen, and begins talking to the patient about diet, equipment, and beginning skin care. During recovery from surgery, post operative teaching should continue. With current pressures to reduce length of hospitalizations, the time available to spend teaching the patient has been reduced, and many patients say they only get cursory instructions, were given equipment and then are surprised when they began self care at home. One patient in our VA survey reported how at discharge he was anxious, sweating so much he couldn’t get the pouch to stick on his body. Patients may receive some information from medical supply companies during hospitalization about nutrition, with counseling and recommendations concerning food issues, but this information is inconsistent.

Written resources are available and patients may receive these before discharge, or seek them out on their own when home. Printed information is available from a number of reliable sources; the United Ostomy Association has published a number of booklets on equipment, self care, pregnancy, etc.[46] Often, this information is generated by equipment companies. Information on local support groups is also identified.[47] Other websites include one by the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing Society.[43] Inspirational books are available for patients to find and use, such as Barbara Barrie’s book titled “Second Act: Life After Colostomy and Other Adventures”.[6] Unfortunately, most information especially on the internet, is anecdotal without rigorous analysis.

Following discharge patients are not typically given specific appointments to a wound care/ostomy clinic. They may receive ostomy care or advice in the context of other scheduled clinic appointments and then only as an “as needed” basis. Support groups, organized by ostomy nurses, and supported by the United Ostomy Association and ostomy equipment companies are held regularly in some communities. Content varies depending on the group and the organization. The content is neither systematic, nor based on self-efficacy and skill enhancement. No formal arrangements are made to provide education to caregivers or partners of the patient with an ostomy. However, Piwonka and Merino reported that adjustment by a patient with an ostomy is influenced by not only the ability to do self-management, but receiving psychological and social support from family and others.[39]

In summary, an evidence-based program intervention is needed to systematically assist patients with ostomies to adjust to the many changes that occur across the dimensions of quality of life. The intervention needs to cover more than the ostomy-specific aspects of equipment use, placement, and skin care. Content should also cover psychological concerns, and social issues, in helping the patient with an ostomy resume an active, healthy lifestyle, without constant fears surrounding the ostomy. In analysis of our qualitative survey and focus group data, we found many barriers, coping and adjustment strategies and recommendations for new ostomates. Major themes identified as greatest challenges included 1) Dealing with the ostomy and pouching system, 2) Discomfort, co-morbidities and complications, 3) Health care barriers, quality and service, 4) Negative psychosocial impacts, 5) Emotional support and education, and 6) Coping philosophies and adaptations.[33] Also identified were bowel control issues related to diet and physical activity, and concerns about sexuality.[13] The intervention we created was based on these findings and a comprehensive review of the literature. The final content was reviewed by three expert nurses in ostomy care, a surgeon, and a research nurse and agreement of one hundred per cent was reached on content and format.

Program Overview

Our approach involved developing a program to help the ostomy patient adjust to the changes that have occurred and learn the best ways to carry out self-management. Several factors influenced the content of the program. First, it had to address the many needs of the ostomy patient, covering all aspects of quality of life. Second, it had to involve a partner or caregiver, if there is one. Third, it had to include access to an experienced ostomate. Fourth, it had to be delivered by an experienced ostomy nurse.

The design of the program began with the selection of the overarching theoretical framework. The framework selected was the Institute of Medicine’s Chronic Care Model (CCM) which is transforming what is currently a reactive health care system into one that keeps its patients as healthy as possible through planning, proven strategies, management and patient activation.[48–49, 51] The CCM can be applied to a variety of chronic illnesses, health care settings, and target populations. The result is healthier patients, more satisfied providers, and cost savings throughout the system. The CCM identifies six essential elements that encourage high-quality chronic disease management. Our program addresses the first four elements. The fifth and sixth elements are for systemwide implementation and sustainability. The first 4 elements and the intervention components responsive to each are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chronic Care Model’s Essential Elements and Ostomy Intervention Elements

| Essential Elements | Ostomy Intervention Component |

|---|---|

| 1. The Community -- Resources and Policies | Identify local culturally competent resources and compile a location-specific resource compendium for patients and their families |

| 2. The Health System -- Organization of Care | Keeping patients as healthy as possible through planning, proven strategies. and culturally competent care management |

| 3. Culturally Competent Self-Management Support | Offer self-efficacy enhancing, evidence-based self-care information and peer support-5 session program using Kate Lorig’s chronic disease self-management program |

| 4. Delivery System Design | Organize group classes (see above) in lieu of unstructured, reactive care; train and utilize volunteer peer educators in culturally competent care |

| 5. Decision Support | Peri-surgical pathways and standing orders* |

| 6. Clinical Information Systems | Integrate clinical care pathways, standing orders and referral into information system. Assure primary care clinician is trained in special needs of ostomates. Provide electronic communications connections between providers and patients.* |

Components not feasible in this pilot study, but which will be added in follow-up trial

The self-management component of the intervention is based on the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program established by Kate Lorig at Stanford University.[29, 27–28, 30] Self-management education complements traditional patient education in supporting patients to live the best possible quality of life with their chronic condition. Whereas traditional patient education offers information and technical skills, self-management education enhances self-efficacy, teaches problem-solving skills, and cognitive restructuring. A central concept in self-management is self efficacy, which is defined as confidence to carry out a behavior necessary to reach a desired goal.[5] Self-efficacy is enhanced when patients succeed in solving patient-identified problems.

The program is taught using a problem-oriented approach. Classes are highly participative, where mutual support and success build the participants’ confidence in their ability to manage their health and maintain active and fulfilling lives. A key principle is setting attainable goals that assure progress and provide rewards. In this model, trained program facilitators who help with self-management include both peers and health professionals. In addition we have incorporated Patient Activation[15–16] which is actually taking action to maintain and improve one’s health and staying the course even when under stress.

Program Highlights

The Chronic Care Ostomy Self Management Program was developed to ensure major HRQOL issues are addressed over a reasonable time frame so as not to be too intensive to patients and caretakers. It includes three two-hour patient sessions, one family caregiver session, and one optional session where patients and caretakers could come together to address remaining concerns. The sessions are held over a twelve week period. All sessions are facilitated by an experienced ostomy nurse and trained Peer Ostomates. We are currently using a one-group design to test the program within a single site (Tucson Arizona), using participants from the greater Tucson area, and involving local certified ostomy nurses as group facilitators.

Program Participants

Patients are recruited in the peri-operative periods (pre-operatively if possible), and post-operatively with an unlimited time since surgery. A network of Peer-Ostomates (with both females and males) who have had their stomas at least two years are employed in the program. The Peer-Ostomates are screened and have completed an orientation session. They are recommended by surgeons or ostomy care nurses, and are not under any current psychiatric care. Peer Ostomates are assigned to participating ostomates by gender. Two experienced part-time ostomy care nurse-facilitators lead the group sessions. Their training included an understanding of their role with the group, review of the curriculum and post session debriefings to identify problems, barriers, and find solutions. Their focus involves training patients to become problems solvers, rather than simply giving them a health professional’s solution.

Program Curriculum

Content for each of the sessions is standardized to ensure consistency across groups. Specific content for each session is identified in Table 2. Teaching methods used for all sessions include adult teaching principles. Interaction is expected with hands on laboratory sessions, and rehearsing embarrassing communication challenges that may occur in social settings, public restaurants, church, etc. Group discussion is used to explore what to say, how to say it, and what to do when communicating with others. Patients are expected to come ready to discuss barriers, coping strategies, adjustment timing, equipment problems, eating problems, and sexuality.

Each session ends with an assignment to be carried out between sessions and discussed at the next session. For example, for Session 1, patients are asked to keep a nutrition log by day and time, and monitor output from the ostomy as well. This content assists the ostomate in becoming familiar with the relationship that occurs between input of food or drink and ostomy output.

Program Evaluation

The program is being evaluated using information from patients, caregivers, peer supporters, as well as the nurses who oversee the implementation. Practical issues such as time of day, location, frequency of sessions are evaluated. We include comments on the marketing strategies, the ways by which participants learn about the program and how they are recruited. In addition, evaluation includes both the content of the sessions, as well as the teaching methods being used. Both deletions and additions to the content are addressed. To date, we have had positive responses from patients, caregivers and the peer supporters.

Conclusions

In this paper, we show several systematic steps used to develop a chronic care ostomy self-management program. First, our own studies and additional published literature were reviewed to identify the evidence for quality of life issues in patients who underwent ostomy surgery. Second, specific recommendations from ostomy patients were reviewed to further describe a recommended structure and components for an ostomy education program. Third, usual care for new ostomates was described to illustrate areas for continued emphasis and areas of additional education and support needs. The final step was to take these materials and develop an ostomy program anchored in the chronic disease model. Our team of experts, including ostomy nurses, identified, reviewed and finalized the program materials.

The Chronic Care Ostomy Self Management Program involves ostomates, their caregivers/partners, and Peer Ostomates. The program is facilitated by experienced ostomy nurses, and involves a six week program, using adult teaching principles, and includes extensive evaluation measures for the ostomates and the facilitators.

Currently the program is being evaluated in clinical practice. Evaluation results will be forthcoming. As patients with ostomies represent a growing number of cancer survivors, this innovative ostomy program has the potential to increase patients’ ability to self-manage their own care thus improving their health-related quality of life.

Table 3.

Training Session Description

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Covers self-care and immediate concerns of ostomates, Content addresses definitions and associated disease states, as well as daily care, nutritional needs, and impact on feelings. Skin care and clothing changes are discussed. Teaching methods are interactive with hands on practice with equipment, pouches, and belts. Importantly, the Peer-Ostomate will be introduced to each new ostomate and the peer will discuss his role, a bit of his history, and his availability throughout the course of the training sessions. There should be a male and female Peer-Ostomate at this session. |

| 2 | Addresses social well-being and deals with the problems of social/interpersonal relationships, public appearances, being prepared for emergencies, intimacy and sexuality, and communication skills. Focus will be within the cultural framework of the individual participant and their family. The participant’s home and social environments will also be included in discussions. Fatigue is discussed as a model of long term effects of cancer and other chronic diseases. |

| 3 | Spouse/significant other or friend will attend a separate session akin to Session 2, covering the same topics specifically tailored to support and adjustment of caregivers as well as additional content as needed from the other sessions in order to provide needed information to ensure the patient’s significant other or caregiver also has achieved a comfort level with ostomy care. We recognize that some patients will not have a designated person to participate in Session 3. We feel it is important not to exclude these patients from the program. |

| 4 | A healthy lifestyle is promoted, including nutritional management, physical activity recommendation and overcoming barriers, psychological health, and improving attitudes. Patients are encouraged to set new priorities, evaluate friends, and work on changing negative attitudes. Tips for traveling are included. |

| 5 | Booster Intervention that addresses a review of daily care, psychological impact, and nutrition/exercise problems. The group demands and needs drive the content for this session. The designated non-patient participant from Session 3 will also be invited to this session to help ensure a complete, well-rounded understanding of issues and comfort with ostomy care and anticipated future dilemmas. |

Acknowledgments

HSRD IIR 02-221 Veteran Affairs Health and Science Merit Review Grant

R21 CA133337, R01 CA 106912, National Cancer Institute

Arizona Cancer Center Support Grant CA 023074, National Cancer Institute

References Used in Text

- 1.Altschuler A, Ramirez M, Grant M, Wendel C, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton L, Krouse RS. The influence of husbands’ or male partners’ support on women’s psychosocial adjustment to having an ostomy resulting from colorectal cancer. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36(3):299–305. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3181a1a1dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.America, United Ostomy Associations of. 2012. [Accessed 8/10/12.];New Patient Guide Colostomy. http://www.ostomy.org/ostomy_info/pubs/UOAA_NPG_Colostomy_2012.pdf.

- 3.Baldwin CM, Grant M, Wendel C, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton LJ, McMullen C, Krouse RS. Gender differences in sleep disruption and fatigue on quality of life among persons with ostomies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(4):335–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin CM, Grant M, Wendel C, Rawl S, Schmidt CM, Ko C, Krouse RS. Influence of intestinal stoma on spiritual quality of life of U.S. veterans. J Holist Nurs. 2008;26(3):185–194. doi: 10.1177/0898010108315185. discussion 195–186; quiz 197–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:119–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrie Barbara. Second Act: Life After Colostomy and Other Adventures. 1st Aufl: Scribner; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coons SJ, Chongpison Y, Wendel CS, Grant M, Krouse RS. Overall quality of life and difficulty paying for ostomy supplies in the Veterans Affairs ostomy health-related quality of life study: an exploratory analysis. Med Care. 2007;45(9):891–895. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318074ce9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Gouveia Santos, Conceição Vera Lúcia, Chaves Eliane Corrêa, Kimura Miako. Quality of Life and Coping of Persons With Temporary and Permanent Stomas. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 2006;33(5):503–509. doi: 10.1097/00152192-200609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gemmill R, Sun V, Ferrell B, Krouse RS, Grant M. Going with the flow: quality-of-life outcomes of cancer survivors with urinary diversion. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37(1):65–72. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3181c68e8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant M. Quality of Life Issues in Colorectal Cancer. Developments in Supportive Cancer Care. 1999;3(1):4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant M, McMullen CK, Altschuler A, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton LJ, Wendel CS, Baldwin CM, Krouse RS. Irrigation Practices in Long-Term Survivors of Colorectal Cancer (CRC) with Colostomies. Clin J Oncol Nurs. doi: 10.1188/12.CJON.514-519. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant M, Ferrell B, Dean G, Uman G, Chu D, Krouse R. Revision and psychometric testing of the City of Hope Quality of Life-Ostomy Questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(8):1445–1457. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000040784.65830.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant M, krouse R, McMullen C, Hornbrook M, Baldwin CM, Herrinton L, Ramirez M, Altschuler A, Mohler MJ. Dietary adjustments reported by colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors with permanent ostomies. Journal of Cancer Education Supplement. 2007;22(4):33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant M, McMullen CK, Altschuler A, Mohler MJ, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton LJ, Wendel CS, Baldwin CM, Krouse RS. Gender differences in quality of life among long-term colorectal cancer survivors with ostomies. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(5):587–596. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.587-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornbrook MC, Wendel CS, Coons SJ, Grant M, Herrinton LJ, Mohler MJ, Baldwin CM, et al. Complications among colorectal cancer survivors: SF-6D preference-weighted quality of life scores. Med Care. 2011;49(3):321–326. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820194c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horner DJ, Wendel CS, Skeps R, Rawl SM, Grant M, Schmidt CM, Ko CY, Krouse RS. Positive correlation of employment and psychological well-being for veterans with major abdominal surgery. Am J Surg. 2010;200(5):585–590. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh Hsiu-Fang, Shannon Sarah E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain S, McGory ML, Ko CY, Sverdlik A, Tomlinson JS, Wendel CS, Coons SJ, et al. Comorbidities play a larger role in predicting health-related quality of life compared to having an ostomy. Am J Surg. 2007;194(6):774–779. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.08.020. discussion 779. S0002-9610(07)00710-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krouse RS, Grant M, Rawl SM, Mohler MJ, Baldwin CM, Coons SJ, McCorkle R, Schmidt CM, Ko CY. Coping and acceptance: the greatest challenge for veterans with intestinal stomas. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(3):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krouse RS, Grant M, Wendel CS, Mohler MJ, Rawl SM, Baldwin CM, Coons SJ, McCorkle R, Ko CY, Schmidt CM. A mixed-methods evaluation of health-related quality of life for male veterans with and without intestinal stomas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(12):2054–2066. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krouse RS, Herrinton LJ, Grant M, Wendel CS, Green SB, Mohler MJ, Baldwin CM, et al. Health-related quality of life among long-term rectal cancer survivors with an ostomy: manifestations by sex. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4664–4670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krouse RS, Mohler MJ, Wendel CS, Grant M, Baldwin CM, Rawl SM, McCorkle R, et al. The VA Ostomy Health-Related Quality of Life Study: objectives, methods, and patient sample. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(4):781–791. doi: 10.1185/030079906X96380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krouse Robert, Grant Marcia, Ferrell Betty, Dean Grace, Nelson Rebecca, Chu David. Quality of Life Outcomes in 599 Cancer and Non-Cancer Patients with Colostomies. Journal of Surgical Research. 2007;138(1):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L, Herrinton LJ, Hornbrook MC, Wendel CS, Grant M, Krouse RS. Early and late complications among long-term colorectal cancer survivors with ostomy or anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(2):200–212. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181bdc408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorig K, Laurin J, Holman HR. Arthritis self-management: a study of the effectiveness of patient education for the elderly. Gerontologist. 1984;24(5):455–457. doi: 10.1093/geront/24.5.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorig K, Mazonson PD, Holman HR. Evidence suggesting that health education for self-management in patients with chronic arthritis has sustained health benefits while reducing health care costs. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(4):439–446. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorig K, Holman H. Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scales measure self-efficacy. Arthritis care and research : the official journal of the Arthritis Health Professions Association. 1998;11(3):155–157. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundy JJ, Coons SJ, Wendel C, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton L, Grant M, Krouse RS. Exploring household income as a predictor of psychological well-being among long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(2):157–161. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9432-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manderson Lenore. Boundary breaches: the body, sex and sexuality after stoma surgery. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(2):405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMullen CK, Hornbrook MC, Grant M, Baldwin CM, Wendel CS, Mohler MJ, Altschuler A, Ramirez M, Krouse RS. The greatest challenges reported by long-term colorectal cancer survivors with stomas. J Support Oncol. 2008;6(4):175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMullen Carmit K, Hornbrook Mark C, Herrinton Lisa J, Altschuler Andrea, Grant Marcia, Wendel Christopher, Coons Stephen Joel, et al. Improving Survivorship Care for Long-Term Colorectal Cancer Survivors: Key Findings of a 5-Year Study. Clin Med Res. 2010;8(1):32–33. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell Kimberly A, Rawl Susan M, Max Schmidt C, Grant Marcia, Ko Clifford Y, Baldwin Carol M, Wendel Christopher, Krouse Robert S. Demographic, Clinical, and Quality of Life Variables Related to Embarrassment in Veterans Living With an Intestinal Stoma. Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 2007 Sep-Oct;34(5):524–532. doi: 10.1097/01.WON.0000290732.15947.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohler MJ, Coons SJ, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton LJ, Wendel CS, Grant M, Krouse RS. The health-related quality of life in long-term colorectal cancer survivors study: objectives, methods and patient sample. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(7):2059–2070. doi: 10.1185/03007990802118360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mowdy Stephanie. The Role of the WOC Nurse in an Ostomy Support Group. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 1998;25(1):51–54. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5754(98)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pittman J, Rawl SM, Schmidt CM, Grant M, Ko CY, Wendel C, Krouse RS. Demographic and clinical factors related to ostomy complications and quality of life in veterans with an ostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2008;35(5):493–503. doi: 10.1097/01.WON.0000335961.68113.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piwonka MA, Merino JM. A multidimensional modeling of predictors influencing the adjustment to a colostomy. Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 1999;26(6):298–305. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5754(99)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popek S, Grant M, Gemmill R, Wendel CS, Mohler MJ, Rawl SM, Baldwin CM, Ko CY, Schmidt CM, Krouse RS. Overcoming challenges: life with an ostomy. Am J Surg. 2010;200(5):640–645. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramirez M, McMullen C, Grant M, Altschuler A, Hornbrook MC, Krouse RS. Figuring out sex in a reconfigured body: experiences of female colorectal cancer survivors with ostomies. Women Health. 2009;49(8):608–624. doi: 10.1080/03630240903496093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Society, American Cancer. Cancer Facts and Figures 2012. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Society, Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses. [Accessed April 22, 2012.];Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society - Welcome. http://www.wocn.org.

- 44.Sun V, Grant M, McMullen CK, Altschuler A, Jane Mohler M, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton LJ, Baldwin CM, Krouse RS. Surviving Colorectal Cancer: Long-Term, Persistent Ostomy-Specific Concerns and Adaptations. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3182750143. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Symms MR, Rawl SM, Grant M, Wendel CS, Coons SJ, Hickey S, Baldwin CM, Krouse RS. Sexual health and quality of life among male veterans with intestinal ostomies. Clin Nurse Spec. 2008;22(1):30–40. doi: 10.1097/01.NUR.0000304181.36568.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.United Ostomy Associations of America, Inc. [Accessed April 22, 2012.];Ostomy Information and Care Guides. http://www.ostomy.org/ostomy_info/

- 47.United Ostomy Associations of America, Inc. [Accessed April 22, 2012.];UOAA Affiliated Support Groups. http://www.ostomy.org/supportgroups1.shtml.

- 48.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner EH, Bennett SM, Austin BT, Greene SM, Schaefer JK, Vonkorff M. Finding common ground: patient-centeredness and evidence-based chronic illness care. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(Suppl 1):S7–15. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.s-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wells RJ. Sexuality: an unknown word for patients with a stoma? Recent results in cancer research Fortschritte der Krebsforschung Progres dans les recherches sur le cancer. 1991;121:115–120. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-84138-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanez-Cadena D, Sarria-Santamera A, Garcia-Lizana F. Can we improve management and control of chronic diseases? Aten Primaria. 2006;37(4):221–230. doi: 10.1157/13085953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]