Abstract

Background

Chronic arsenic exposure is a major global health problem. Few epidemiologic studies, however, have evaluated the association of arsenic with kidney measures. Our objective was to evaluate the cross-sectional association between inorganic arsenic exposure and albuminuria in American Indian adults from rural areas of Arizona, Oklahoma and North and South Dakota.

Study Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting & Partipants

Strong Heart Study locations in Arizona, Oklahoma, and North and South Dakota. 3,821 American Indian men and women 45 to 74 years of age with urine arsenic and albumin measures.

Predictor

Urine arsenic.

Outcomes

Urine albumin/creatinine ratio and albuminuria status.

Measurements

Arsenic exposure was estimated by measuring total urine arsenic and urine arsenic species using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICPMS) and high performance liquid chromatography-ICPMS, respectively. Urine albumin was measured by automated nephelometric immunochemistry.

Results

The prevalence of albuminuria (albumin-creatinine ratio, ≥30 mg/g) was 30%. The median value for the sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic species was 9.7 (IQR, 5.8-15.6) μg/g creatinine. The multivariable-adjusted prevalence ratios of albuminuria (albumin-creatinine ratio. ≥30 mg/g) comparing the three highest to lowest quartiles of the sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic species were 1.16 (95% CI, 1.00-1.34), 1.24 (95% CI, 1.07-1.43), and 1.55 (95% CI, 1.35-1.78), respectively (P for trend <0.001). The association between urine arsenic and albuminuria was observed across all participant subgroups evaluated and was evident for both micro and macroalbuminuria.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design cannot rule out reverse causation.

Conclusions

Increasing urine arsenic concentrations were cross-sectionally associated with increased albuminuria in a rural US population with a high burden of diabetes and obesity. Prospective epidemiologic and mechanistic evidence is needed to understand the role of arsenic as a kidney disease risk factor.

Inorganic arsenic is a widespread toxicant and carcinogen that occurs naturally in the earth’s crust. In the general population, the main sources of arsenic exposure are drinking water and food. Chronic exposure to inorganic arsenic from drinking water is a worldwide public health problem resulting from natural mineral deposits or improperly disposed arsenic chemicals in groundwater.1-3 Dietary sources of arsenic are an increasingly recognized concern for general populations as arsenic is found at relatively high concentrations in some foods including rice, flour and certain juices. 4, 5 Occupational sources of arsenic exposure have markedly decreased in developed countries in the last decades, including copper smelters, the use of arsenic pesticides and herbicides, and the use of arsenic as a wood preservative.6

In addition to playing a role in cancer,7 arsenic may be involved in the development of cardiovascular disease,8-10 diabetes,11-13 and developmental and reproductive abnormalities.14 Few epidemiologic studies, however, have evaluated the relationship between arsenic exposure and chronic kidney disease outcomes. In China, high arsenic exposure from burning contaminated coal (geometric mean 288 μg/g) was found to be associated with albumin and other proteins in urine.15 In a population in Bangladesh with a wide range of exposure to arsenic in drinking water (from <10 to >100 μg/L), arsenic exposure was reported to be positively related to the prevalence of proteinuria.8 In Southwestern Taiwan, in an area characterized by historically high arsenic levels in well water (>500 μg/L), kidney disease mortality decreased after the installation of public water supply systems and the reduction of arsenic in drinking water.8 In the US, arsenic levels in drinking water are generally low,6 although it is estimated that around 13 million inhabitants live in areas where arsenic in drinking water is above 10 μg/L, the US EPA standard for arsenic in drinking water.16 In Southeastern Michigan (mean water arsenic 11 μg/L), an ecological study found a positive association between moderate water arsenic concentrations and kidney disease mortality.17 Additional epidemiological studies are needed to evaluate the association of arsenic with chronic kidney disease outcomes at low to moderate levels of arsenic exposure, relevant for many communities around the world.

In this study, our objective was to investigate the relationship between arsenic exposure, as measured in urine, with the presence of albuminuria in the Strong Heart Study (SHS). The SHS is a population-based study funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute to evaluate cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in American Indian communities from Arizona, Oklahoma, and North and South Dakota,18, 19 where the primary source of arsenic exposure is through drinking water.19 Albuminuria, the excess of serum albumin in the urine due to increased filtration through damaged glomeruli or decreased reabsorption in the proximal tubules,20, 21 is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease in this population.22 In the SHS communities the primary source of arsenic exposure is through drinking water, and we recently confirmed long-term exposure from low to moderate arsenic levels.19 In this setting, it is essential to assess the potential for arsenic as a novel, preventable risk factor for albuminuria.

METHODS

Study population

From 1989 to 1991, men and women 45-74 years of age from 13 tribes and communities were invited to participate in the SHS 23. The goal was to recruit 1,500 participants per region. In Arizona and Oklahoma, all community members were invited to participate. In the Dakotas, a cluster sampling technique was used. The overall participation rate was 62% and a total of 4,549 participants were recruited. We used data from 3,974 SHS participants with urine arsenic measured at the baseline visit (1988-1991). We further excluded 1 participant missing data on albuminuria, 10 participants missing diabetes status, and 135 participants missing other variables of interest, leaving 3,821 participants for this analysis. The SHS protocol and consent form were approved by local institutional review boards, participating tribes and the Indian Health Service. All participants provided informed consent.

Urine albumin and creatinine

Spot urine samples were collected in 1989-91, frozen within 1-2 hours of collection, and stored at −80°C at the Penn Medical Laboratory, MedStar Health Research Institute (Hyattsville, MD, and Washington, DC) 18. Urine albumin and creatinine were measured at the Laboratory of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch, Phoenix, Arizona, by an automated nephelometric immunochemical procedure and an automated alkaline picrate methodology, respectively.18 To account for urine dilution, urine albumin concentrations were divided by urine creatinine concentrations. In addition to albumin concentrations, we defined albuminuria as an albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) of ≥30 mg/g, as based on standard guidelines24 and in previous SHS studies.22, 23 We also defined microalbuminuria as ACR between 30 and <300 mg/g and macroalbuminuria as ACR ≥300 mg/g.24

Urine arsenic

From the same urine sample that had been used to measure urine albumin and urine creatinine, up to 1.0 mL of urine per participant was transported on dry ice to the Trace Element Laboratory of the Institute of Chemistry-Analytical Chemistry, Karl Franzens University (Graz, Austria) in 2009. Total arsenic concentrations in urine samples were measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICPMS) (Agilent 7700x ICPMS, Agilent Technologies), and arsenic species were determined with high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Agilent 1100) coupled to ICPMS (HPLC-ICPMS), which served as the arsenic selective detector. Arsenic speciation can distinguish arsenic species that are directly related to inorganic arsenic exposure (arsenite, arsenate, monomethylarsonic acid [MMA], and dimethylarsinic acid [DMA]) from those related to organic arsenicals in seafood (arsenobetaine), which are generally nontoxic.6 The analytical methods used in these analyses and the associated quality control criteria have been described in detail.25 The limit of detection for total arsenic, and for inorganic arsenic (arsenite+arsenate), MMA, DMA and arsenobetaine plus other cations was 0.1 μg/L. The percentages of participants with concentrations below the limit of detection were 0.03% for total arsenic, 5.2% for inorganic arsenic, 0.8% for MMA, 0.03% for DMA, and 2.1% for arsenobetaine plus other cations. For participants with arsenic species below the limits of detection, levels were imputed as the corresponding limit of detection divided by the square root of two. An in-house reference urine and the Japanese National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) No 18 Human urine were analyzed together with the samples. The inter-assay coefficients of variation for total arsenic, inorganic arsenic, MMA, DMA and arsenobetaine for the in-house reference urine were 4.4%, 6.0%, 6.5%, 5.9%, and 6.5%, respectively.25 Urine concentrations of arsenobetaine and other cations were very low (median, 0.69 μg/g; interquartile range, 0.41-1.57 μg/g), confirming that seafood intake was low in this population. Urine arsenic concentrations (μg/L) were divided by urine creatinine concentrations (g/L) to account for urine dilution and expressed in μg/g creatinine.

Other variables

Sociodemographic (age, gender, education) and life-style (smoking status, and alcohol status) information at baseline was collected by trained and certified interviewers using a standardized questionnaire 18. Physical exam measures (height, weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure) were performed by centrally trained nurses and medical assistants following a standardized protocol. Methods to measure blood pressure, body mass index, fasting glucose and 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), HbA1c, and plasma fibrinogen have been described.26-28 Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose level of ≥126 mg/dL, a 2-h post-load plasma glucose level of ≥200 mg/dL, an HbA1c concentration of ≥6.5%, or the use of insulin or an oral hypoglycemic agent. Plasma creatinine was measured by an alkaline-picrate rate method. As described previously,29 estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from recalibrated creatinine, age and sex using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula29a without an ethnicity factor.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in Stata IC 11.2 (Stata Corporation). In addition to total arsenic, we calculated the sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic species as an additional measure of exposure to inorganic arsenic. Urine concentrations of total arsenic, the sum of inorganic and methylated species, and albumin were right skewed and log transformed for the analyses. Quartiles were generated based on the distribution of urine arsenic concentrations in the overall study sample.

Linear models were used to estimate adjusted ratios of the geometric means of urine albumin concentrations by urine arsenic concentrations. Logistic regression models were used to estimate adjusted odds ratios for the prevalence of urine ACR ≥30 mg/g by urine arsenic concentrations. Since the prevalences of urine ACR ≥30 mg/g were high and prevalence odds ratios overestimated prevalence ratios, we used the results of logistic regression models to estimate marginally adjusted prevalences of urine ACR ≥30 mg/g by urine arsenic concentrations and then calculated prevalence ratios. 95% confidence intervals for the prevalence ratios were generated using the delta method.30 In both linear and logistic regression models, arsenic concentrations were entered as quartiles (comparing quartiles 2-4 to the lowest quartile), log-transformed (comparing an interquartile range in log-transformed arsenic levels) and as restricted quadratic splines with knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of the log-arsenic distribution (to evaluate the dose-response relationship in a flexible manner), in separate models. P-values for linear trend were obtained by including in the regression model a continuous variable with the medians corresponding to each quartile of the arsenic distribution.31

In addition to estimating crude models, we estimated both linear and logistic regression models with progressive degrees of adjustment. Initially, we adjusted for demographic and lifestyle factors including sex (male, female), age (continuous), study region (Oklahoma, Arizona, North and South Dakota), body mass index (continuous), education (years of education), smoking status (never, former, current), and alcohol status (never, former, current). Then, we further adjusted for health conditions such as diabetes (yes/no), systolic blood pressure (continuous), hypertension medication (yes/no), and eGFR (continuous). Finally, we further adjusted for concentrations of urine cadmium (log-transformed), another widespread metal that is an established nephrotoxicant. We also ran multinomial logistic models to estimate the prevalence ratio of microalbuminuria (30 to <300 mg/g) and macroalbuminuria (≥300 mg/g) to normal levels, and additional logistic regression models to compare macro vs. microalbuminuria by increasing urine arsenic levels.

The association between urine ACR of ≥30 mg/g and urine arsenic was evaluated in fully adjusted models stratified by sex (male, female), age (<50 years, 50 - 65 years, >65 years), study location (Oklahoma, Arizona, North and South Dakota), body mass index (<25 kg/m2, 25-29 kg/m2, >29 kg/m2), education (no high school, some high school, completed high school), smoking status (never, former, current), alcohol status (never, former, current), diabetes status (yes, no), hypertension medication (yes, no), eGFR category (≤60 ml/min/1.73m2, >60 ml/min/1.73m2), fibrinogen (<264 mg/dl, 264 - 324 mg/dl, and >324 mg/dl) and urine cadmium category (<0.7 μg/g, 0.7 - 1.21 μg/g, and >1.21 μg/g). To test for effect modification, interaction terms were generated as the product of urine arsenic concentration and the participant subgroups of interest. The p-value for interaction terms was determined using a bootstrapping procedure with 1000 repetitions, a more stable approach when sample sizes are small.32 We had no a priori hypotheses for effect modification by participant characteristics, except for urine cadmium, for which a synergistic interaction was supported by limited epidemiologic and experimental evidence.15, 33 We ran several sensitivity analyses. First, we repeated full models to estimate prevalence ratios using Poisson regression, with similar results (data not shown). Second, we repeated the analyses adjusting for urine creatinine separately instead of dividing urine arsenic concentrations by urine creatinine, also with similar findings (data not shown). Third, we adjusted for educational levels using 4 categorical variables (no high school, some high school, completed high school, beyond high school) instead of years of education with no differences in the associations between arsenic and albuminuria (data not shown). Fourth, we repeated the analyses for the sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic species and albuminuria excluding participants with undetectable inorganic arsenic, MMA, or DMA (n=213) with consistent findings (data not shown).

RESULTS

Median urine concentrations were 12.8 μg/g for total arsenic and 9.7 μg/g for the sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic species. The Spearman correlation coefficients were 0.90 for total arsenic and the sum of inorganic and methylated species, 0.36 for arsenobetaine and total arsenic, and 0.13 for arsenobetaine and the sum of inorganic and methylated species. The sum of inorganic and methylated species were higher in men, in Arizona and the Dakotas compared to Oklahoma, in participants with lower education, in participants with higher systolic blood pressure, in current drinkers, in diabetics, and in participants with urine ACR ≥30 mg/g (Table 1). Similar associations were found for total arsenic, except higher total arsenic concentrations in women (Table S1, provided as online supplementary material).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic species

| Total | Sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic species (μg/g creatinine) |

P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5.8 | 5.8 - 9.7 | 9.7 - 15.6 | >15.6 | |||

| No. of participants | 3821 | 960 | 963 | 945 | 953 | |

| Sex | <0.01 | |||||

| Male | 40.9 | 49.3 | 40.4 | 40.3 | 33.4 | |

| Female | 59.1 | 50.7 | 59.6 | 59.7 | 66.6 | |

| Age (y) | 56.2 (8.0) | 56.5 (8.3) | 55.9 (8.1) | 56.3 (7.9) | 56.2 (7.9) | 0.8 |

| Study Location | <0.01 | |||||

| Arizona | 34.0 | 7.3 | 25.1 | 43.6 | 60.2 | |

| Oklahoma | 33.2 | 70.3 | 38.6 | 17.3 | 6.0 | |

| South Dakota | 32.8 | 22.4 | 36.3 | 39.1 | 33.8 | |

| Education | <0.01 | |||||

| No HS | 22.2 | 9.2 | 16.3 | 28.0 | 35.4 | |

| Some HS | 25.1 | 24.1 | 23.8 | 24.7 | 27.9 | |

| Completed HS | 52.7 | 66.7 | 59.9 | 47.3 | 36.7 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.9 (6.3) | 30.7 (5.7) | 31.4 (6.3) | 30.8 (6.3) | 30.7 (6.9) | 0.3 |

| Smoking status | 0.3 | |||||

| Never | 34.0 | 36.0 | 35.3 | 32.8 | 31.8 | |

| Former | 32.6 | 31.0 | 30.8 | 32.7 | 35.9 | |

| Current | 33.4 | 33.0 | 33.9 | 34.5 | 32.3 | |

| Alcohol status | <0.01 | |||||

| Never | 41.9 | 48.2 | 43.5 | 38.8 | 36.9 | |

| Former | 16.2 | 17.7 | 16.6 | 14.3 | 16.1 | |

| Current | 41.9 | 34.1 | 39.9 | 46.9 | 47.0 | |

| Diabetes | <0.01 | |||||

| No | 50.3 | 61.5 | 53.3 | 49.5 | 36.8 | |

| Yes | 49.7 | 38.5 | 46.7 | 50.5 | 63.2 | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 127.5 (19.3) | 127.2 (17.6) | 126.4 (18.7) | 127.4 (19.8) | 128.9 (20.9) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension Medication | 0.2 | |||||

| No | 76.6 | 74.5 | 77.6 | 76.8 | 77.5 | |

| Yes | 23.4 | 25.5 | 22.4 | 23.2 | 22.5 | |

| eGFR, ml/min/ 1.73m2 | 97.1 (18.6) | 94.1 (17.9) | 96.7 (17.5) | 97.5 (19.3) | 100.0 (19.4) | <0.01 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dl | 303.2 (80.5) | 291.7 (75.4) | 296.9 (74.1) | 307.4 (81.5) | 316.9 (87.9) | <0.01 |

| Urine cadmium, μg/g | 1.23 (1.9) | 1.0 (1.6) | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.3 (2.7) | 1.5 (2.0) | <0.01 |

| Urine ACR, mg/g | 319.2 (1574.8) |

147.5 (840.1) | 203.2 (853.7) | 369.8 (1348.3) |

559.2 (2568.2) |

|

| Albuminuria status | <0.01 | |||||

| No | 70.0 | 82.2 | 75.3 | 68.7 | 53.6 | |

| Yes | 30.0 | 17.8 | 24.7 | 31.3 | 46.4 | |

| Arsenic concentration | ||||||

| Total urine | 12.7 (7.8- 20.5) |

5.6 (4.5, 6.9) | 9.7 (8.3, 11.6) |

15.1 (13.1, 17.5) |

26.7 (21.4, 36.1) |

|

| Inorganic and methylated |

9.7 (5.8, 15.6) | 4.2 (3.3, 5.0) | 7.5 (6.6, 8.6) | 12.4 (10.9, 13.8) |

21.8 (18.3, 29.0) |

|

| Urine arsenobetaine | 0.69 (0.41, 0.57) |

0.57 (0.36, 1.09) |

0.72 (0.40, 1.82) |

0.72 (0.42, 1.69) |

0.78 (0.49, 1.72) |

|

Note: Data for categorical variables are given as percentage; data for continuous variables are given as mean +/−standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Conversion factor fibrinogen in mg/dL to μmol/L, x 0.0294. HS, high school; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio.

For trend.

The prevalence of urine ACR ≥30 mg/g was 30.0% (Table 2). Compared to those with urine ACR <30 mg/g, participants with urine ACR ≥30 mg/g were more likely to live in Arizona, have lower education levels, higher body mass index (BMI), be never and former smokers, have diabetes, take anti-hypertensive medication, and have higher systolic blood pressure, lower eGFR levels and higher fibrinogen levels.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics by urine albumin concentrations

| Total | ACR (mg/g) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 30 (reference)* |

30-300 (microalbuminuria) |

>300 (macroalbuminuria) |

|||

| No. of participants | 3821 | 2674 | 719 | 428 | |

| Sex | 0.2 | ||||

| Male | 40.9 | 58.3 | 60.5 | 62.4 | |

| Female | 59.1 | 41.7 | 39.5 | 37.6 | |

| Age ( y) | 56.2 (8.0) | 55.8 (7.9) | 57.13 (8.5) | 57.5 (7.8) | <0.01 |

| Study Location | <0.01 | ||||

| Arizona | 34.0 | 24.9 | 50.3 | 62.8 | |

| Oklahoma | 33.2 | 37.6 | 25.9 | 18.0 | |

| South Dakota | 32.8 | 37.5 | 23.8 | 19.2 | |

| Education | <0.01 | ||||

| No HS | 22.2 | 18.7 | 27.8 | 34.3 | |

| Some HS | 25.1 | 23.5 | 29.5 | 28.3 | |

| Completed HS | 52.7 | 57.8 | 42.7 | 37.4 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.9 (6.3) | 30.7 (6.4) | 31.5 (6.3) | 30.8 (5.8) | 0.01 |

| Smoking status | <0.01 | ||||

| Never | 34.0 | 32.6 | 35.6 | 39.7 | |

| Former | 32.6 | 31.0 | 35.7 | 37.6 | |

| Current | 33.4 | 36.4 | 28.7 | 22.7 | |

| Alcohol status | 0.01 | ||||

| Never | 41.9 | 41.1 | 41.2 | 47.9 | |

| Former | 16.2 | 15.7 | 17.1 | 17.8 | |

| Current | 41.9 | 43.2 | 41.7 | 34.3 | |

| Diabetes | <0.01 | ||||

| No | 50.3 | 63.9 | 23.8 | 9.8 | |

| Yes | 49.7 | 36.1 | 76.2 | 90.2 | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 127.5 (19.3) | 124.0 (17.1) | 131.7 (19.6) | 142.1 (23.3) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension Medication |

<0.01 | ||||

| No | 76.6 | 81.6 | 70.0 | 56.3 | |

| Yes | 23.4 | 18.4 | 30.0 | 43.7 | |

| eGFR, ml/min/ 1.73m2 |

97.1 (18.6) | 99.2 (13.4) | 99.6 (18.2) | 79.6 (32.7) | <0.01 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dl | 303.2 (80.5) | 287.6 (69.8) | 318.3 (77.3) | 375.3 (101.1) | <0.01 |

| Urine cadmium μg/g) |

1.23 (1.9) | 1.2 (2.1) | 1.2 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.6) | 0.03 |

| Urine ACR, mg/g | 319.2 (1574.8) | 8.4 (6.7) | 100.6 (71.7) | 2628.2 (4018.6) | <0.01 |

| Arsenic concentration |

|||||

| Total urine | 12.7 (7.8, 20.5) | 11.5 (7.0, 18.2) | 16.1 (9.1, 25.1) | 17.2 (11.2, 27.7) | |

| Inorganic and methylated |

9.7 (5.8, 15.6) | 8.6 (5.3, 13.8) | 12.5 (7.2, 19.1) | 13.3 (8.4, 21.3) | |

| Urine arsenobetaine |

0.69 (0.41, 0.57) | 0.67 (0.40, 1.56) | 0.66 (0.42, 1.38) | 0.85 (0.49, 2.21) | |

Note: Data for categorical variables are given as percentages; data for continuous variables are given as mean +/-standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Conversion factor for fibrinogen in mg/dL to μmol/L, x 0.0294.

HS, high school; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio.

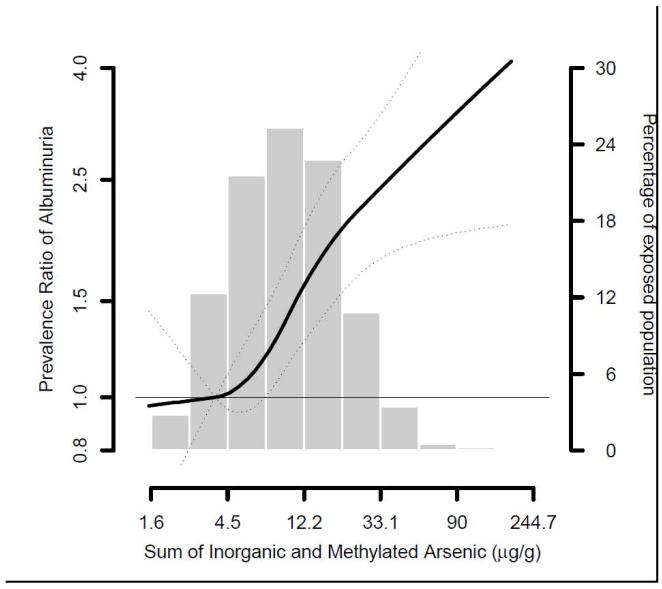

Urine arsenic was positively associated with the prevalence of urine ACR ≥30 mg/g (Table 3, Figure 1). The fully adjusted prevalence ratios for urine ACR ≥30 mg/g comparing participants in the highest to lowest arsenic quartiles were 1.42 (95% CI, 1.24-1.64) for total arsenic and 1.55 (95% CI, 1.35-1.78) for the sum of inorganic and methylated species (Table 3, model 4). The association was present for both micro and macroalbuminuria, although the association was somewhat stronger for macroalbuminuria (Table 4). Urine arsenic concentrations were also positively associated with urine albumin concentrations in regression models (Table S2). Comparing the highest to lowest quartile, urine albumin concentrations were 1.58 (95% CI, 1.33-1.88) and 1.67 (95% CI, 1.39-2.00) times higher for total arsenic and for the sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic species, respectively (Table S2, Model 4).

Table 3.

Prevalence of albuminuria by urine arsenic concentrations.

| Total Arsenic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <7.8 pg/g | 7.8 - 12.8 μg/g | 12.8 - 20.5 μg/g | >20.5 μg/g | p* | 75th vs 25th

percentile |

|

| Cases/Noncases | 178/782 | 252/705 | 286/666 | 431/521 | 1147/2674 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.42 (1.19- 1.68) |

1.62 (1.37, 1.90) |

2.44 (2.10, 2.83) |

<0.001 | 1.55 (1.42, 1.69) |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.20 (1.02, 1.42) |

1.21 (1.03, 1.43) |

1.67 (1.44, 1.95) |

<0.001 | 1.30 (1.19, 1.42) |

| Model 3 | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.13 (0.98, 1.30) |

1.17 (1.02, 1.34) |

1.49 (1.31, 1.70) |

<0.001 | 1.23 (1.14, 1.33) |

| Model 4 | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.11 (0.97, 1.28) |

1.14 (0.99, 1.31) |

1.44 (1.26, 1.64) |

<0.001 | 1.21 (1.12, 1.31) |

| Sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic species | ||||||

| <5.8 μg/g | 5.8 - 9.7 μg/g | 9.7 - 15.6 μg/g |

≥15.6 μg/g | P* | 75th vs 25th

percentile |

|

| Cases/Noncases | 171/789 | 238/725 | 296/649 | 442/511 | 1147/2674 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.38 (1.16, 1.65) |

1.75 (1.49, 2.07) |

2.60 (2.23, 3.03) |

<0.001 | 1.63 (1.49, 1.78) |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.23 (1.04, 1.47) |

1.35 (1.14, 1.60) |

1.84 (1.57, 2.17) |

<0.001 | 1.52 (1.39, 1.67) |

| Model 3 | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.17 (1.01, 1.36) |

1.26 (1.09, 1.46) |

1.60 (1.39, 1.84) |

<0.001 | 1.28 (1.18, 1.39) |

| Model 4 | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.16 (1.00, 1.34) |

1.24 (1.07, 1.43) |

1.55 (1.35, 1.78) |

<0.001 | 1.26 (1.16, 1.36) |

Note: Unless otherwise indicated, values are presented as prevalence ratio (95% CI). Albuminuria defined as albumin-creatinine ratio >30 mg/g. Model 1 is crude. Model 2 is adjusted for age (continuous), sex, study region, body mass index (continuous), education, smoking status, and alcohol status. Model 3 further includes diabetes status, hypertensive medication, and systolic blood pressure (continuous), eGFR (continuous) and fibrinogen (mg/dl).Model 4 further includes urine cadmium (log-transformed).

For trend across quartiles.

Figure 1.

Prevalence ratio of albuminuria by sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic species. Lines represent prevalence ratios (solid line) and 95% confidence intervals (dotted line) based on restricted quadratic spline models for log transformed arsenic with 3 knots. The reference was set at the 10th percentile of the urine arsenic biomarker distribution. Prevalence ratios were adjusted for age (continuous), sex, study region, body mass index (continuous), education, smoking status, alcohol status, diabetes status, hypertensive medication, systolic blood pressure (continuous), eGFR (continuous) and fibrinogen (mg/dl) and urine cadmium (log-transformed).

Table 4.

Ratio of prevalence of albuminuria in those with arsenic (inorganic + methylated) concentrations at the 75th vs 25th percentile

| Albuminuria | Microalbuminuria | Macroalbuminuria | Macro- vs Microalbuminuria |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases/Noncases | 1147/2674 | 719/2674 | 428/2674 | 428/719 |

| Model 1 | 1.63 (1.49-1.78) | 1.51 (1.34, 1.70) | 1.87 (1.58, 2.21) | 1.14 (1.00, 1.29) |

| Model 2 | 1.52 (1.39, 1.67) | 1.34 (1.18, 1.52) | 1.44 (1.21, 1.72) | 1.05 (0.91, 1.20 |

| Model 3 | 1.28 (1.18, 1.39) | 1.21 (1.07, 1.37) | 1.37 (1.19, 1.58) | 1.15 (1.02, 1.29) |

| Model 4 | 1.26 (1.16, 1.36) | 1.22 (1.08, 1.38) | 1.28 (1.11, 1.48) | 1.08 (0.96, 1.22) |

Note: Unless otherwise indicated, data presented as prevalence ratio (95% CI). Here, arsenic level is sum of inorganic and methylated arsensic, expressed in μg/g. Albuminuria defined as urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) of ≥30 mg/g; microalbuminuria, as ACR 30 to <300 mg/g; and macroalbuminuria, as ACR ≥300 mg/g. Model 1 is crude. Model 2 is adjusted for age (continuous), sex, study region, body mass index (continuous), education, smoking status, and alcohol status. Model 3 further includes diabetes status, hypertensive medication, and systolic blood pressure (continuous), eGFR (continuous) and fibrinogen (mg/dl) Model 4 further includes urine cadmium (log-transformed).

The positive association between arsenic and the prevalence of urine ACR ≥30 mg/g was observed across all participant subgroups evaluated, although the association was stronger in younger participants and in participants with higher education levels (Table S3). We found no evidence of effect modification for the association between arsenic and albuminuria by urine cadmium concentrations.

Finally, we evaluated the association between albuminuria and arsenic metabolism, as measured in %MMA. After adjustment for age in years, sex, study location, body mass index (kg/m2), education in years, smoking status, alcohol status, systolic blood pressure, hypertension medication (yes or no), diabetes status (yes or no), eGFR category (≤60 mL/minute/1.73m2), urine cadmium (log-transformed), fibrinogen (mg/dl) and urine arsenic (μg/g creatinine), the prevalence ratios comparing quartiles 2-4 of %MMA (10.8%-13.9%, 14.0%-17.5%, and ≥17.6 %) to the lowest quartile (<10.8%) were 0.87 (95% CI. 0.77-0.98), 0.91(95% CI, 0.01-1.02), and 0.88 (95% CI, 0.77-1.00), respectively, (p for trend = 0.11).

DISCUSSION

Exposure to inorganic arsenic, as measured in urine, was positively associated with increased urine albumin concentrations and with urine ACR ≥30 mg/g in men and women from rural communities in Arizona, Oklahoma and North and South Dakotas. The associations persisted after adjustment for demographic and kidney disease risk factors and were observed for both micro and macroalbuminuria. The associations were also observed in all population-subgroups evaluated, although they were stronger in some subgroups, including younger participants and more educated participants. These findings should be interpreted with caution, as we had no a priori hypotheses regarding these subgroups. Finally, we found no evidence of effect modification in albuminuria by urine cadmium concentrations, despite limited epidemiologic and experimental evidence suggesting potential synergy between arsenic and cadmium.15, 33

Previous studies of arsenic and kidney measures have generally been conducted in populations with arsenic exposure levels higher than those in the Strong Heart Study. In a population-based study conducted in Guizhou, China, 122 individuals exposed to arsenic from burning coal (urine arsenic geometric mean 288.4 μg/g) had higher urine albumin, β2-microglobulin (β2MG), and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) concentrations compared to 123 unexposed participants (urine arsenic geometric mean 56.2 μg/g).15 Arsenic and cadmium exposure were associated with increased excretion of albumin, β2MG, and NAG after controlling for possible confounders.33 Moreover, there was a synergistic effect between arsenic and cadmium co-exposures on urine albumin and NAG concentrations.15 In Zhejiang, China, moderate arsenic exposure (mean urine arsenic 35 μg/g creatinine) was associated with urine albumin concentrations but not with several tubular markers, including NAG, β-2 microglobulin and retinol binding protein.34, 35 Like our study, however, they found no effect modification by cadmium levels.34, 35 In a large population-based study from Araihazar, Bangladesh (N=10,160), both arsenic measured in drinking water (lowest quintile, ≤7 μg/L; highest quintile, 180-864 μg/L; mean, 99 μg/L) and urine arsenic concentrations (lowest quintile, <36 μg/L; highest quintile, ≥115 μg/L) were positively associated with the prevalence and incidence of proteinuria measured qualitatively.8 The adjusted odds ratios comparing the highest to the lowest quintile were 1.65 for drinking water arsenic and 1.65 for urine arsenic. In Bangladesh, the study population was characterized by low body mass index and low prevalence of diabetes,8 while in our study both obesity and diabetes were very common.23, 36

Few experimental studies have specifically evaluated the renal effects of arsenic exposure in animal models. In dogs, short-term administration of sodium arsenate (0.73 mg/kg) results in vacuolation of the renal tubular epithelium, while higher doses (14.66 mg/kg) result in moderate glomerular sclerosis and severe tubular necrosis.37 In mice, arsenic exposure via drinking water (22.5 mg/L) increases urine NAG but not urine albumin concentrations.38 In that model, mice given both arsenic in drinking water and cadmium in food exhibit increases in urine protein and NAG excretion that are markedly higher compared to mice given cadmium or arsenic alone.38 The mechanisms underlying arsenic-induced nephrotoxicity are likely to be complex. Mechanistic evidence suggests that arsenic increases inflammation, as measured by increased interleukin 6 and interleukin 8 expression.39 and reactive oxygen species pathways.40, 41 These mechanisms could play a role in arsenic related kidney damage.42 Widespread vascular endothelial dysfunction or chronic low-grade inflammation may also be underlying mechanisms for albuminuria.43 Arsenic has been associated with vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1),44, 45 a biomarker of endothelial dysfunction that is also a surrogate of increased cardiovascular risk.46, 47 In our study, adjustment for fibrinogen, a non-specific inflammatory marker, did not modify the association between arsenic and albuminuria. Arsenic could also contribute to kidney damage and albuminuria through diabetes effects. Arsenic has been associated with diabetes in some12, 13 but not all48 epidemiological studies. Substantial mechanistic evidence also supports a role for arsenic in the development of diabetes.49-51 Epidemiologic52, 53 and experimental53, 54 evidence, moreover, indicates that arsenic could induce more severe nephrotoxic effects in the presence of diabetes.

Strengths of this study include high quality and standardized protocols for recruitment, interviews, physical examinations, collection and storage of biological samples, and laboratory procedures to determine urine albumin and arsenic concentrations. The use of urine arsenic to reflect arsenic exposure is an additional strength, as urine arsenic integrates all sources of exposure and it has been selected as the biomarker of choice for epidemiologic studies.55 While the half-life of arsenic is relatively short, urine arsenic concentrations were relatively constant over a 10-year period,19 indicating that exposure through drinking water and diet remained unchanged and supporting the use of a single biomarker to reflect long-term arsenic exposure in this population.

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional study and reverse causation may be an issue. Experimental evidence suggests that arsenic binds to proteins.56-61 Two arsenic binding sites have been found on bovine serum albumin, 56, 62 and arsenite has been found to bind serum albumin in vitro under physiological conditions.63 The binding of arsenic and albumin in serum could result in higher albumin in urine with increasing arsenic exposure or in higher arsenic in urine in individuals with albuminuria. Evidence from Bangladesh, however, showed that proteinuria was associated with arsenic in drinking water and not just with urine arsenic and that urine arsenic was associated with incident proteinuria,8 suggesting that reverse causation was unlikely to explain the associations. Second, we used spot urine samples, which must be adjusted for urine dilution. In our study we used urine creatinine to correct for urine dilution. While specific gravity has been used as an alternative in some populations, it is not suitable in our study population with a high prevalence of diabetic glucosuria and albuminuria.64, 65 Third, water samples were not collected or measured for arsenic content, although previous studies have found similar associations with proteinuria for arsenic in urine and in drinking water.8 Fourth, we cannot discard the possibility of residual confounding by socioeconomic factors or environmental factors, although the associations persisted after adjustment for education and urine cadmium concentrations. Finally, our study was conducted in a population with a high burden of albuminuria, obesity and diabetes, and it is uncertain if our findings can be generalized to populations with a different disease profile.

In conclusion, at the low to moderate levels of arsenic exposure present in rural communities in the US with a high burden of diabetes and obesity, increasing urine arsenic concentrations were cross-sectionally associated with increased albuminuria. While we cannot discard reverse causation, kidney effects may add to the potential carcinogenic,7, 66 cardiometabolic,9, 49, 67 and developmental14 health effects related to low-moderate exposure to inorganic arsenic from drinking water and food. Prospective epidemiologic studies and mechanistic experimental research needs to be conducted to understand the role of arsenic as a kidney disease risk factor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Support: Supported by grants from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (HL090863 and SHS grants HL41642, HL41652, HL41654 and HL65521) and from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P30ES03819). Ms Zheng was supported by a T32 training grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES103650).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_______) is available at www.ajkd.org

Reference List

- 1.Hughes MF, Beck BD, Chen Y, Lewis AS, Thomas DJ. Arsenic exposure and toxicology: a historical perspective. Toxicol Sci. 2011;123(2):305–332. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordstrom DK. Public health. Worldwide occurrences of arsenic in ground water. Science. 2002;296(5576):2143–2145. doi: 10.1126/science.1072375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AH, Steinmaus CM. Arsenic in drinking water. BMJ. 2011;342:d2248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson BP, Taylor VF, Karagas MR, Punshon T, Cottingham KL. Arsenic, organic foods, and brown rice syrup. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(5):623–626. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert-Diamond D, Cottingham KL, Gruber JF, et al. Rice consumption contributes to arsenic exposure in US women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(51):20656–20660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109127108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fowler BA, Chou SJ, Jones RL, Chen C, Arsenic . In: Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals. Third Edition Nordberg GF, Fowler BA, Nordberg M, Freiberg LT, et al., editors. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2007. pp. 367–443. [Google Scholar]

- 7.IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 2004 02 Oct 15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Parvez F, Liu M, et al. Association between arsenic exposure from drinking water and proteinuria: results from the Health Effects of Arsenic Longitudinal Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(3):828–835. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medrano MA, Boix R, Pastor-Barriuso R, et al. Arsenic in public water supplies and cardiovascular mortality in Spain. Environ Res. 2010;110(5):448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan Y, Marshall G, Ferreccio C, et al. Acute myocardial infarction mortality in comparison with lung and bladder cancer mortality in arsenic-exposed region II of Chile from 1950 to 2000. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(12):1381–1391. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coronado-Gonzalez JA, Del Razo LM, Garcia-Vargas G, Sanmiguel-Salazar F, Escobedo-de la PJ. Inorganic arsenic exposure and type 2 diabetes mellitus in Mexico. Environ Res. 2007;104(3):383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navas-Acien A, Silbergeld EK, Streeter RA, Clark JM, Burke TA, Guallar E. Arsenic exposure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of the experimental and epidemiological evidence. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(5):641–648. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navas-Acien A, Silbergeld EK, Pastor-Barriuso R, Guallar E. Arsenic exposure and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in US adults. JAMA. 2008;300(7):814–822. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.7.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sohel N, Vahter M, Ali M, et al. Spatial patterns of fetal loss and infant death in an arsenic-affected area in Bangladesh. Int J Health Geogr. 2010;9:53. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-9-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordberg GF, Jin T, Hong F, Zhang A, Buchet JP, Bernard A. Biomarkers of cadmium and arsenic interactions. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;206(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Environmental Protection Agency National primary drinking water regulations; arsenic and clarifications to compliance and new source contaminants monitoring; final rule. Fed Regist. 2001;66(14):6976–7066. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meliker JR, Wahl RL, Cameron LL, Nriagu JO. Arsenic in drinking water and cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and kidney disease in Michigan: a standardized mortality ratio analysis. Environ Health. 2007;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz R, et al. The Strong Heart Study. A study of cardiovascular disease in American Indians: design and methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(6):1141–1155. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navas-Acien A, Umans JG, Howard BV, et al. Urine arsenic concentrations and species excretion patterns in American Indian communities over a 10-year period: the Strong Heart Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(9):1428–1433. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClellan WM, Warnock DG, Judd S, et al. Albuminuria and Racial Disparities in the Risk for ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010101085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Seaghdha CM, Hwang SJ, Upadhyay A, Meigs JB, Fox CS. Predictors of incident albuminuria in the Framingham Offspring cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(5):852–860. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Lee ET, Best LG, et al. Association of albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in diabetes: the Strong Heart Study. British Journal of Diabetes & Vascular Disease. 2005;5:334–340. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee ET, Howard BV, Wang W, et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease in a population with high prevalence of diabetes and albuminuria: the Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 2006;113(25):2897–2905. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.593178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheer J, Findenig S, Goessler W, et al. Arsenic species and selected metals in human urine: validation of HPLC/ICPMS and ICPMS procedures for a long-term population-based epidemiological study. Anal Methods. 2012;4:406–413. doi: 10.1039/C2AY05638K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fretts AM, Howard BV, McKnight B, et al. Associations of processed meat and unprocessed red meat intake with incident diabetes: the Strong Heart Family Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(3):752–758. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.029942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmieri V, Celentano A, Roman MJ, et al. Fibrinogen and preclinical echocardiographic target organ damage: the strong heart study. Hypertension. 2001;38(5):1068–1074. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.095335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geffken DF, Keating FG, Kennedy MH, Cornell ES, Bovill EG, Tracy RP. The measurement of fibrinogen in population-based research. Studies on instrumentation and methodology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1994;118(11):1106–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shara NM, Wang H, Mete M, et al. Estimated GFR and Incident Cardiovascular Disease Events in American Indians: The Strong Heart Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(5):795–803. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. Anew equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Localio AR, Margolis DJ, Berlin JA. Relative risks and confidence intervals were easily computed indirectly from multivariable logistic regression. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(9):874–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. 2nd ed Wiley-Interscience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Efron B. Bootstrap Methods: Another Look at the Jackknife. Annals of Statistics. 1979;7(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong F, Jin T, Zhang A. Risk assessment on renal dysfunction caused by co-exposure to arsenic and cadmium using benchmark dose calculation in a Chinese population. Biometals. 2004;17(5):573–580. doi: 10.1023/b:biom.0000045741.22924.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buchet JP, Heilier JF, Bernard A, et al. Urinary protein excretion in humans exposed to arsenic and cadmium. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2003;76(2):111–120. doi: 10.1007/s00420-002-0402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nordberg GF. Biomarkers of exposure, effects and susceptibility in humans and their application in studies of interactions among metals in China. Toxicol Lett. 2010;192(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.06.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeh F, Dixon AE, Marion S, et al. Obesity in adults is associated with reduced lung function in metabolic syndrome and diabetes: the Strong Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(10):2306–2313. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsukamoto H, Parker HR, Gribble DH, Mariassy A, Peoples SA. Nephrotoxicity of sodium arsenate in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1983;44(12):2324–2330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J, Liu Y, Habeebu SM, Waalkes MP, Klaassen CD. Chronic combined exposure to cadmium and arsenic exacerbates nephrotoxicity, particularly in metallothionein-I/II null mice. Toxicology. 2000;147(3):157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Escudero-Lourdes C, Medeiros MK, Cardenas-Gonzalez MC, Wnek SM, Gandolfi JA. Low level exposure to monomethyl arsonous acid-induced the over-production of inflammation-related cytokines and the activation of cell signals associated with tumor progression in a urothelial cell model. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;244(2):162–173. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barchowsky A, Klei LR, Dudek EJ, Swartz HM, James PE. Stimulation of reactive oxygen, but not reactive nitrogen species, in vascular endothelial cells exposed to low levels of arsenite. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27(11-12):1405–1412. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barchowsky A, Dudek EJ, Treadwell MD, Wetterhahn KE. Arsenic induces oxidant stress and NF-kappa B activation in cultured aortic endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;21(6):783–790. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malyszko J, Malyszko JS, Pawlak K, Mysliwiec M. Visfatin and apelin, new adipocytokines, and their relation to endothelial function in patients with chronic renal failure. Adv Med Sci. 2008;53(1):32–36. doi: 10.2478/v10039-008-0024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ned RM, Yesupriya A, Imperatore G, et al. Inflammation gene variants and susceptibility to albuminuria in the U.S. population: analysis in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 1991-1994. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y, Santella RM, Kibriya MG, et al. Association between arsenic exposure from drinking water and plasma levels of soluble cell adhesion molecules. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(10):1415–1420. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.States JC, Srivastava S, Chen Y, Barchowsky A. Arsenic and cardiovascular disease. Toxicol Sci. 2009;107(2):312–323. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shai I, Pischon T, Hu FB, Ascherio A, Rifai N, Rimm EB. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecules, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecules, and risk of coronary heart disease. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(11):2099–2106. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wijnstok NJ, Twisk JW, Young IS, et al. Inflammation markers are associated with cardiovascular diseases risk in adolescents: the Young Hearts project 2000. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(4):346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Y, Ahsan H, Slavkovich V, et al. No association between arsenic exposure from drinking water and diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(9):1299–1305. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Navas-Acien A, Sharrett AR, Silbergeld EK, et al. Arsenic exposure and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(11):1037–1049. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paul DS, Walton FS, Saunders RJ, Styblo M. Characterization of the impaired glucose homeostasis produced in C57BL/6 mice by chronic exposure to arsenic and high-fat diet. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(8):1104–1109. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xue P, Hou Y, Zhang Q, et al. Prolonged inorganic arsenite exposure suppresses insulin-stimulated AKT S473 phosphorylation and glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes: involvement of the adaptive antioxidant response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;407(2):360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiou JM, Wang SL, Chen CJ, Deng CR, Lin W, Tai TY. Arsenic ingestion and increased microvascular disease risk: observations from the south-western arseniasis-endemic area in Taiwan. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(4):936–943. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang JP, Wang SL, Lin Q, Zhang L, Huang D, Ng JC. Association of arsenic and kidney dysfunction in people with diabetes and validation of its effects in rats. Environ Int. 2009;35(3):507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel HV, Kalia K. Sub-chronic arsenic exposure aggravates nephrotoxicity in experimental diabetic rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 2010;48(7):762–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Research Council . Arsenic in Drinking Water. National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aposhian HV, Aposhian MM. Arsenic toxicology: five questions. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19(1):1–15. doi: 10.1021/tx050106d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bertolero F, Marafante E, Rade JE, Pietra R, Sabbioni E. Biotransformation and intracellular binding of arsenic in tissues of rabbits after intraperitoneal administration of 74As labelled arsenite. Toxicology. 1981;20(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(81)90103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bogdan GM, Sampayo-Reyes A, Aposhian HV. Arsenic binding proteins of mammalian systems: I. Isolation of three arsenite-binding proteins of rabbit liver. Toxicology. 1994;93(2-3):175–193. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Menzel DB, Hamadeh HK, Lee E, et al. Arsenic binding proteins from human lymphoblastoid cells. Toxicol Lett. 1999;105(2):89–101. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(98)00380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pizarro I, Gomez M, Camara C, Palacios MA, Roman-Silva DA. Evaluation of arsenic species-protein binding in cardiovascular tissues by bidimensional chromatography with ICP-MS detection. J Anal At Spectrom. 2004;19(2) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan H, Wang N, Weinfeld M, Cullen WR, Le XC. Identification of Arsenic-Binding Proteins in Human Cells by Affinity Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81(10):4144–4152. doi: 10.1021/ac900352k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uddin SJ, Shilpi JA, Murshid GMM, Rahman AA, Sarder MM, Alam MA. Determination of the Binding Sites of Arsenic on Bovine Serum Albumin Using Warfarin (Site-I Specific Probe) and Diazepam (Site-II Specific Probe) Journal of Biological Sciences. 2004;4(5):609–612. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang H, Ding J, Chang P, Chen Z, Sun G. Determination of the Interaction of Arsenic and Human Serum Albumin by Online Microdialysis Coupled to LC with Hydride Generation Atomic Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Chromatographia. 2010;71(11):1075–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chadha V, Garg U, Alon US. Measurement of urinary concentration: a critical appraisal of methodologies. Pediatr Nephrol. 2001;16(4):374–382. doi: 10.1007/s004670000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Voinescu GC, Shoemaker M, Moore H, Khanna R, Nolph KD. The relationship between urine osmolality and specific gravity. Am J Med Sci. 2002;323(1):39–42. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Y, Parvez F, Gamble M, et al. Arsenic exposure at low-to-moderate levels and skin lesions, arsenic metabolism, neurological functions, and biomarkers for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases: review of recent findings from the Health Effects of Arsenic Longitudinal Study (HEALS) in Bangladesh. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;239(2):184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen Y, Graziano JH, Parvez F, et al. Arsenic exposure from drinking water and mortality from cardiovascular disease in Bangladesh: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d2431. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.