Conspectus

Biological nitrogen fixation — the reduction of N2 to two NH3 molecules — supports more than half the human population. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme nitrogenase, whose predominant form, discussed here, comprises an electron-delivery Fe protein and a catalytic MoFe protein. Nitrogenase has been studied extensively but the catalytic mechanism has remained unknown. At minimum, a mechanism must identify and characterize each intermediate formed during catalysis, and embed these intermediates within a kinetic framework that explains their dynamic interconversion. Nitrogenase kinetics have been described by the Lowe-Thorneley (LT) model, which provides rate constants for transformations among intermediates, denoted En, indexed by the number of electrons (and protons), n, that have been accumulated within the MoFe protein. However, until recently, research on purified nitrogenase had not resulted in characterization of any En state beyond Eo.

In this article we summarize the recent characterization of three freeze-trapped intermediate states formed during nitrogenase catalysis, and their placement within the LT kinetic scheme. First we discuss the key E4 state, which is primed for N2 binding and reduction and which we refer to as the “Janus intermediate”. This state contains the active-site iron-molybdenum cofactor ([7Fe-9S-Mo-C-homocitrate]; FeMo-co) at its resting oxidation level, its four accumulated reducing equivalents being stored as two [Fe-H-Fe] bridging hydrides. The other two trapped intermediates contain reduced forms of N2. One, intermediate I, has S = 1/2 FeMo-co. ENDOR/HYSCORE measurements indicate that I, is the final catalytic state, E8, having NH3 product bound to FeMo-co at its resting redox level. The other characterized intermediate, designated H, has integer-spin FeMo-co (Non-Kramers; S ≥ 2). ESEEM measurements indicate that H binds the [−NH2] fragment and therefore corresponds to E7. These assignments, plus consideration of previous studies, imply a pathway in which (i) N2 binds at E4 with liberation of H2, (ii) N2 is promptly reduced to N2H2, (iii) the two N’s are hydrogenated alternately to form hydrazine-bound FeMo-co, and (iv) two NH3 are liberated in two further steps of reduction. This proposal identifies nitrogenase as following a ‘Prompt-Alternating (P-A)’ reaction pathway, and unifies the catalytic pathway with the LT kinetic framework. However, it does not incorporate one of the most puzzling aspects of nitrogenase catalysis: obligatory generation of H2 upon N2 binding that apparently ‘wastes’ two reducing equivalents and thus 25% of the total energy supplied by the hydrolysis of ATP. The finding that E4 stores its four accumulated reducing equivalents as two bridging hydrides, considered in the context of the organometallic chemistries of hydrides and dihydrogen, leads us to propose an answer to this puzzle. Namely, that H2 release upon N2 binding involves reductive elimination of two hydrides to yield N2 bound to doubly reduced Fe. Coupled delivery of the two available electrons and two activating protons yields cofactor-bound diazene, in keeping with the P-A scheme. This keystone completes a draft mechanism for nitrogenase that organizes the vast body of data upon which it is formulated, and is intended to serve as a basis for future experiments.

Introduction

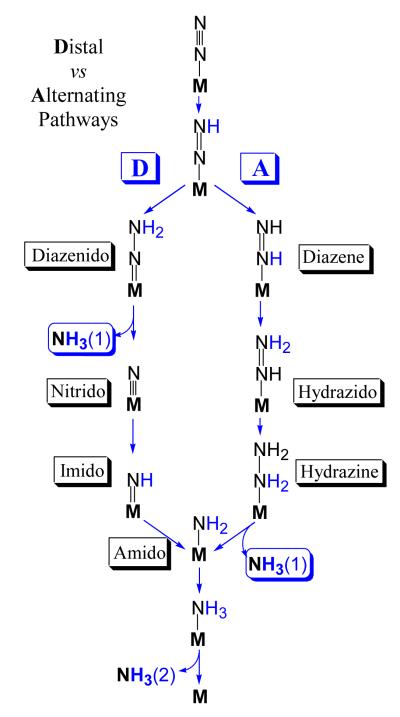

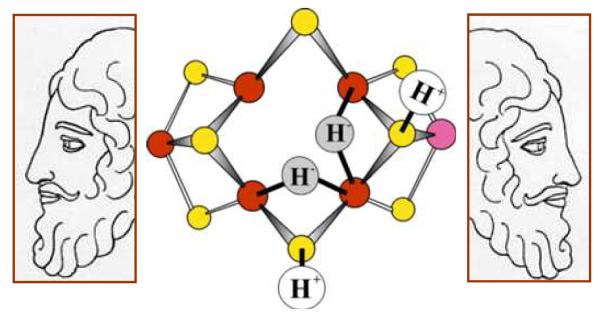

Biological nitrogen fixation — the reduction of N2 to two NH3 molecules — supports more than one-half of today’s human population.1 This process is catalyzed by the nitrogenase enzymes,2 with the best-characterized and most prevalent being the Mo-dependent enzyme discussed here.3-6 It consists of two components, the electron-delivery Fe protein and the catalytic MoFe protein. The latter contains two remarkable metal clusters, the N2 binding/reduction active site called the iron-molybdenum cofactor ([7Fe-9S-Mo-C-homocitrate]; FeMo-co, Fig 1), and the [8Fe-7S] P cluster, which is involved in electron transfer to FeMo-co.3,4

Fig 1.

FeMo-co and key residues

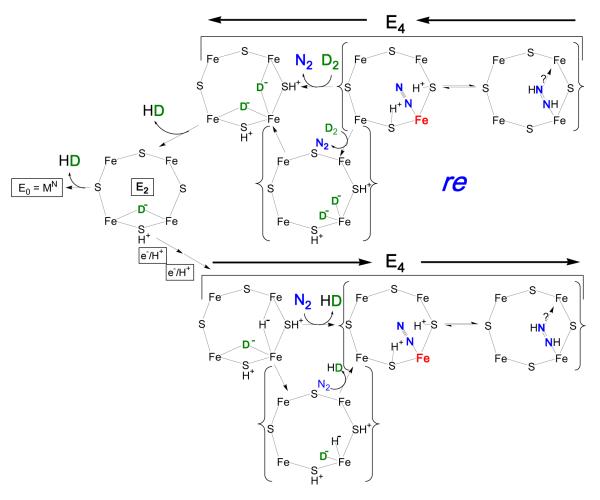

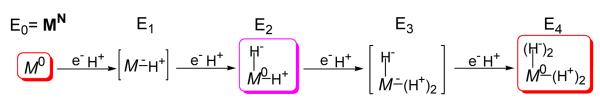

We seek to uncover the nitrogenase mechanism, which at minimum incorporates: (i) a reaction pathway that identifies each intermediate that forms, beginning with resting-state nitrogenase and endings with release of the second NH3 and return to the resting state; (ii) an understanding of the kinetics/dynamics through which these intermediate states are formed. Our efforts build on the ‘kinetic’ foundation provided by the Lowe-Thorneley (LT) kinetic model for nitrogenase function.3,7,8 The LT scheme, shown in a highly simplified form in Fig 2, is formulated in terms of states, denoted En, indexed by the number of electrons (and protons), n, that have been accumulated within the MoFe protein; it is characterized by the rate constants for transformations among those states. Single-electron transfer from Fe protein to MoFe protein is driven by the binding and hydrolysis of two MgATP within the Fe protein; the release of the Fe protein after delivery of its electron is the rate-limiting step of catalysis.7

Fig 2.

Highly simplified LT kinetic scheme, highlighting, (i) correlated electron/proton delivery in eight steps; (ii) some of the possible pathways for decay by H2 release are shown; (iii) N2 binding and H2 release at either the E3 or E4 levels, with the pathway through E3 deemphasized. LT also denote the protons added to FeMo-co (eg. E1H1); for clarity we have omitted this.

One of the most puzzling aspects of nitrogenase function embodied in the LT scheme (Fig 2) is the generation of H2 upon N2 binding. In the absence of other substrates, MoFe protein reduces protons to form H2 by a cycle of electron/proton accumulation and relaxation back towards resting state, as illustrated in Fig 2. With increasing partial pressure of N2, the reducing equivalents supplied to MoFe protein are increasingly used to produce NH3, but it was surprisingly shown that the limiting stoichiometry for ‘enzymological’ nitrogen fixation requires eight electrons/protons to reduce each N2 to two NH3,3,7 with two electrons/protons being lost through obligatory H2 evolution during the process.9 Thus, there is a fundamental ‘mismatch’ between the chemical stoichiometry of six electron and protons per N2 reduced and the ‘enzymological’ stoichiometry, in which eight electrons and protons are required. This mismatch causes the index for the LT En intermediates in Fig 2 to take the values, n = 0 (resting) ↔ 8, not 0 ↔ 6. The delivery of each electron requires the hydrolysis of two MgATP, and so the optimum enzymological stoichiometry becomes,

| (1) |

As a result, this mismatch introduces the apparent ‘waste’ of 25% of the total energy supplied by the hydrolysis of ATP.7 In the LT scheme, the chemical/enzymological mismatch is introduced by a reversible coupling between N2 binding and H2 loss, which occurs only after the MoFe protein has been activated by the accumulation of three or four electrons and protons (E3 or E4) (Fig 2).

The first forty years of study of purified nitrogenase10 did not identify any En catalytic intermediates beyond E0,11,3,12 leaving the identity of the reaction pathway unresolved.3 The way forward was provided by microbiological experiments that showed the α-70Val acts as a ‘gatekeeper’ that sterically controls the access of substrate to the Fe6 ion at the waist of FeMo-co,4 thereby also implicating Fe as the site of substrate binding, while α-195His was inferred to be involved in proton delivery (Fig 1).13 Substitution for one or both of these residues allowed us to freeze-quench trap a number of nitrogenase turnover intermediates, each of which shows an EPR signal arising from an S = ½ state of FeMo-co, rather than the S = 3/2 state of resting-state FeMo-co; this was accompanied by the trapping of an analogous state formed with the WT enzyme.4

This report begins with a summary of progress since our last Account,5 The characterization by ENDOR/ESEEM/HYSCORE of three freeze-trapped nitrogen fixation intermediates has enabled us to propose identities for all the LT En nitrogen-fixation intermediates, thereby identifying the reaction pathway and unifying it with the kinetic scheme for N2 fixation by nitrogenase. It then offers an explanation of why Nature generates H2 upon N2 binding to nitrogenase. Together, these two components lead to a draft mechanism for nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase that organizes the vast efforts, by many investigators,3,7 on which it builds, and provides a framework for future efforts.

Progress

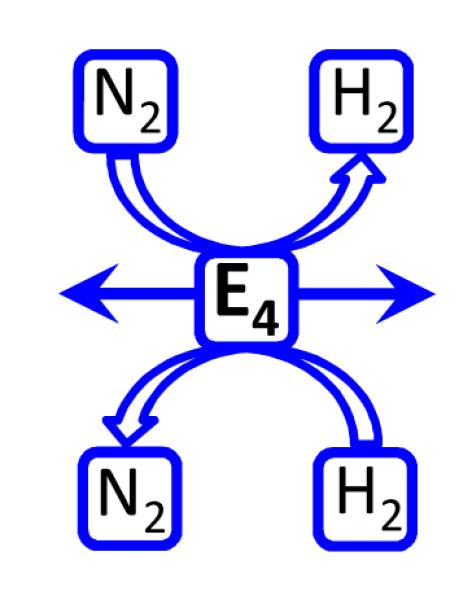

E4: the ‘Janus Intermediate’

Early in the search for intermediates,14,15 the α70Val→Ile substitution in the MoFe protein was shown to deny access of all substrates to the active site, except protons.16 Samples of this substituted MoFe protein freeze-quenched during turnover under Ar exhibited a new S = ½ EPR signal, and 1,2H ENDOR spectroscopic analysis of this trapped state,16 which also is observed at lower concentrations during turnover of WT enzyme under Ar,17 revealed the presence of two metal-bridging hydrides M-H-M’. Recent 95Mo ENDOR measurements established that M = M’ = Fe: FeMo-co in this state contains two Fe-H-Fe fragments (Fig 3).18 To complete the characterization of the metal-ion core of FeMo-co in this intermediate, we recently characterized its 57Fe atoms of the E4 FeMo-co through use of a suite of advanced ENDOR methods.19

Fig 3.

ENDOR-derived description of E4 as containing two Fe-H-Fe moieties, emphasizing our view of the essential role of this key ‘Janus intermediate’, which comes at the halfway point in the LT scheme, and whose properties have implications for the first and second halves of the scheme. Janus image adapted from: Janus12.jpg checkxstarinfinity.blogspot.com/

Annealing this intermediate in the frozen state, which prevents further delivery of electrons, showed that it relaxes to the resting state by the successive loss of two H2 molecules, thus revealing that the trapped intermediate is the E4 state, which has accumulated n = 4 electrons and four protons.20 Examination of a simplified version of the LT scheme of Fig 2 reveals that E4 is a key stage in the process of nitrogen fixation. Indeed, we have come to view it as the ‘Janus’ intermediate, referring to the Roman God of transitions who is represented with two faces, one looking to the past and one looking to the future. On the one hand, looking ‘back’ from E4 to the steps by which it is formed, E4 is the culmination of one-half of the electron/proton deliveries during N2 fixation: four of the eight reducing equivalents are accumulated in E4, before N2 even becomes involved. Looking ‘forward’, towards NH3 formation, E4 is the state at which N2 hydrogenation begins, and it is involved in one of the biggest puzzles in N2 fixation, ‘why’ and ‘how’ is H2 lost upon N2 binding.

Storage of the reducing equivalents accumulated in the E4 state as bridging hydrides has major consequences. In this binding mode a hydride is less susceptible to protonation, and the tendency to lose H2 (Fig 2) is thereby diminished, favoring the accumulation of reducing equivalents. This mode also lowers the ability of the hydrides to undergo exchange with protons in the environment, a characteristic that is shown to be of central importance below. However, the bridging mode also lowers hydride reactivity towards substrate hydrogenation, relative to that of terminal hydrides.21,22 As a result, substrate hydrogenation most probably incorporates the conversion of hydrides from bridging to terminal binding modes.23 We next discuss how the structure found for E4 guides our assignment of structures for the E1-E3 states. Subsequently, we show how the E4 structure defined possible mechanisms for coupling H2 loss to N2 binding.

E1-E3 and ‘Why such a big catalytic cluster?’

Given our finding that the four accumulated electrons of E4 reside not on the metal ions but, instead, are formally assigned to two Fe-bridging hydrides, what then are the proper descriptions of E1-E3? The addition of one electron/proton to the MoFe protein results in the E1 state. When experimentally observed in Mossbauer experiments,24 it was presumed to contain the reduced metal-ion core of FeMo-co, denoted M− in Fig 4, with the proton bound to sulfur. Given the presence in E4 of two bridging hydrides/two protons, it is an obvious extension to propose that upon delivery of the second electron/proton to form E2 the metal-sulfur core of the FeMo-cofactor ‘shuttles’ both electrons onto one proton to form an Fe-H-Fe hydride, leaving the second proton bound to sulfur and the core at the resting-state, M0, redox level (also commonly referred to as, MN), Fig 4. A subsequent, analogous, two-stage process would then yield the E4 state, with its two Fe-H-Fe hydrides, two sulfur-bound protons, and the core at the resting-state, M0, redox level.

Fig 4.

Formulation of E1-E3 derived from consideration of E4. Note M denotes FeMo-co inorganic core in its entirety; the superscript (+/−) represents difference between core charge and that of core in the resting state.

Such a process of acquiring the four reducing equivalents of E4 involves only a single redox couple connecting two formal redox levels of the FeMo-co core of eight metal ions, M0 the resting state, and M− the one-electron reduced state of the core, Fig 4.19 Indeed, comparisons of the 57Fe ENDOR results for the E4 intermediate with earlier 57Fe ENDOR studies and ‘electron inventory analyses’ of nitrogenase intermediates led us to the remarkable conclusion that throughout the nitrogenase catalytic cycle the FeMo-cofactor might cycle through only two formal redox levels of the metal-ion core. On reflection, it seems obvious that only by ‘storing’ the equivalents as hydrides is it possible to accumulate so much reducing power at the constant potential of the Fe protein. We further proposed that such ‘simple’ redox behavior of a complex metal center might apply to other FeS enzymes carrying out substrate reductions.19

Considering the critical role of hydrides in storing reducing equivalents, we also suggested that the E1 and E3 states respectively might well contain one and two bridging hydrides bound to a formally oxidized metal-ion core (Fig 5).6

Fig 5.

Alternative formulation of E1-E4 under assumption that hydride formation occurs at each stage. As in Fig 4, Note: M denotes FeMo-co inorganic core and superscript (+/−) represents difference between core charge and that of core in the resting state.

If the FeMo-cofactor does not utilize more than one redox couple during catalysis, then why is it constructed from so many metal ions? As discussed below, the hydrides of E4 bind to no fewer than three Fe atoms of a 4-Fe face of FeMo-co, as shown in Fig 3. It is further possible that catalysis is modulated by the linkage of Fe ion(s) to the anionic atom C that is centrally located within the metal-sulfur core of the FeMo-cofactor.25,26 Formation of such a 4Fe face and the incorporation of C is not likely with less than a trigonal prism of six Fe ions linked by sulfides to generate these structural features. In this view, the trigonal prismatic FeMo-cofactor core of six Fe ions plus C generates the catalytically active 4Fe face. This prism is capped, and its properties are likely ‘tuned’, by two “anchor” ions — one Fe plus a Mo (or a V or Fe in the alternative nitrogenases).

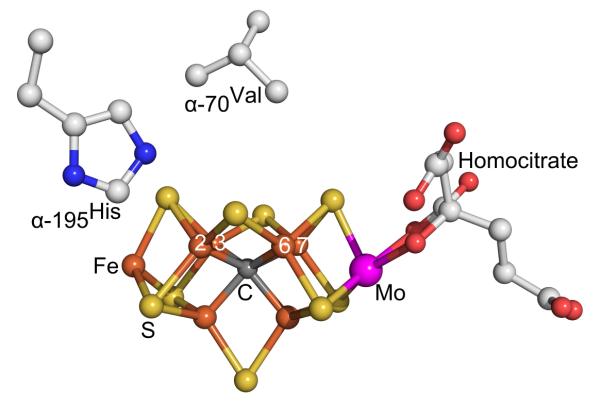

‘Dueling’ N2 reduction pathways and intermediates of N2 reduction

Researchers have long considered two competing proposals for the second half of the LT kinetic scheme, the reaction pathway for N2 reduction that begins with the Janus E4 state.3,5,27 These invoke distinctly different intermediates, Scheme 1, and computations suggest they likely involve different metal-ion sites on FeMo-co.27 In the ‘Distal’ (D) pathway, utilized by N2-fixing inorganic Mo complexes28 and suggested to apply in reaction at Mo of FeMo-co,29 a single N of N2 is hydrogenated in three steps until the first NH3 is liberated, then the remaining nitrido-N is hydrogenated three more times to yield the second NH3. In the ‘Alternating’ (A) pathway that has been suggested to apply to reaction at Fe of FeMo-co,30 the two N’s instead are hydrogenated alternately, with a hydrazine-bound state generated upon four steps of hydrogenation and the first NH3 only liberated during the fifth step (Scheme 1). Simple arguments can be made for both pathways.3-5,31

Schme 1.

As shown by Scheme 1, characterization of catalytic intermediates formed during the reduction of N2 could distinguish between the D and A pathways. However, such intermediates had long eluded capture until four intermediates associated with N2 fixation were freeze-trapped for ENDOR spectroscopic studies.4,5 These four were generated under the hypothesis that intermediates associated with different reduction stages could be trapped using N2 or semi-reduced forms of N2 or their analogs: N2; NH=NH; NH=N-CH3; H2N-NH2.3,4

Intermediate I

A combination of X/Q-band EPR and 15N, 1,2H ENDOR measurements on the intermediates formed with the three semi-reduced substrates during turnover of the α-70Val→Ala, α6195His→Gln MoFe protein subsequently showed that in fact they all correspond to a common intermediate (here denoted I) in which FeMo-co binds a substrate-derived [NxHy] moiety. 4,5 Thus, both the diazenes and hydrazine enter and ‘flow through’ the normal N2-reduction pathway (Scheme 1), and the diazene reduction must have ‘caught up’ with the ‘later’ hydrazine reaction.

1,2H and 15N 35 GHz CW and pulsed ENDOR measurements next showed that I exists in two conformers, each with metal ion(s) in FeMo-co having bound a single nitrogen from a substrate-derived [NxHy] fragment.4,5 Subsequent high-resolution 35 GHz pulsed ENDOR spectra and X-band HYSCORE measurements showed no response from a second nitrogen atom, and when I was trapped during turnover with the selectively labeled CH3-15N=NH, 13CH3-N=NH, or C2H3-N=NH, no signal was seen from the isotopic labels.31 From these results we concluded the N-N linkage had been cleaved in forming I, which thus represents a late stage of nitrogen fixation, after the first ammonia molecule already has been released31 and only a [NHx] (x = 2 or 3) fragment of substrate is bound to FeMo-co.

The Nitrogenase reaction pathway: D vs A

Given that states that could correspond to I are reached by both A and D pathways (Scheme 1), the identity of this [NHx] moiety need not in itself distinguish between pathways. However, the spectroscopic findings about I, in conjunction with a variety of additional considerations, led us to propose that nitrogenase functions via the A reaction pathway of Scheme 1 for reduction of N2.31 As one example, to explain how nitrogenase could reduce each of the substrates, N2, N2H2 and N2H4, to two NH3 molecules via a common A reaction pathway, one need only postulate that each substrate ‘joins’ the pathway at the appropriate stage of reduction, binding to FeMo-co that has been ‘activated’ by accumulation of a sufficient number of electrons (possibly with FeMo-co reorganization) and then proceeds along that pathway. Energetic considerations,27 in combination with the strong influence of α-70Val substitutions of MoFe protein without modification of FeMo-co reactivity, then implicate Fe, rather than Mo, as the site of binding and reactivity.16

As further support of this conclusion, it is most economical to suggest that both the Mo-dependent nitrogenase studied here and the V-dependent nitrogenase2 reduce N2 by the same pathway. As V-nitrogenase produces traces of N2H4 while reducing N2 to NH3,32 then according to Scheme 1 this enzyme clearly functions via the A pathway, implying the same is true for Mo-nitrogenase.

Intermediate H

When nitrogenase is freeze-quenched during turnover, the EPR signals from trapped intermediates in odd-electron FeMo-co states (Kramers states; S = 1/2, 3/2,…; En, n = even),4,5 plus the signals from residual resting-state FeMo-co never quantitate to the total FeMo-co present, indicating that EPR-silent states of FeMo-co must also exist. These silent MoFe protein states must contain FeMo-co with an even number of electrons, and thus correspond to En, n = odd (n = 2m +1, m = 0-3) intermediates in the LT scheme. Such states may contain diamagnetic FeMo-co, or FeMo-co in integer-spin (S = 1, 2, …), ‘non-Kramers (NK)’ states,24,33 but no EPR signal from an integer-spin form of FeMo-co had been detected. However, careful examination of samples that contain intermediate I, 4,5 now have revealed a broad EPR signal at low field in Q-band spectra that arises from an integer-spin system with a ground-state non-Kramers doublet.34

In earlier work we showed how to characterize a non-Kramers doublet with ESEEM spectroscopy (NK-ESEEM),35 so NK-ESEEM time-waves were collected for the NK intermediates trapped during turnover with: 14N and 15N isotopologs of N2H2 and N2H4 substrates; 95Mo-enriched α-70Val→Ala, α-195His→Gln MoFe protein; H-14N=14N-CH3, H-15N=14N-CH3, and H-14N=14N-CD3. The measurements indicate that the NK-EPR signals arises from FeMo-co in an integer-spin state, S ≥ 2, that this state corresponds to a common intermediate, H, formed with all of these substrates, and that H binds an NHx fragment formed after cleavage of the N-N bond of substrate bound to FeMo-co and loss of NH3. Quadrupole coupling parameters for the NHx fragment indicate it is not NH3, and that H binds as [-NH2].

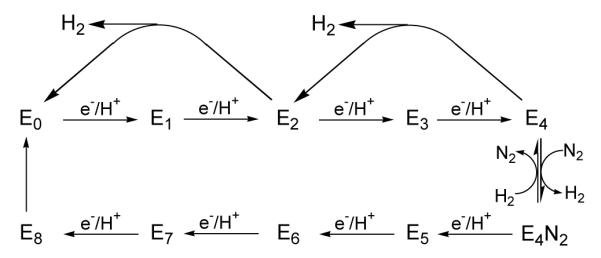

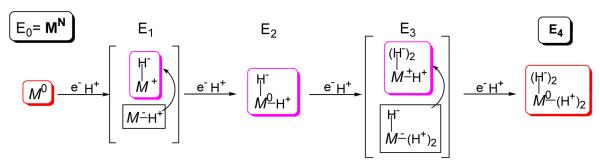

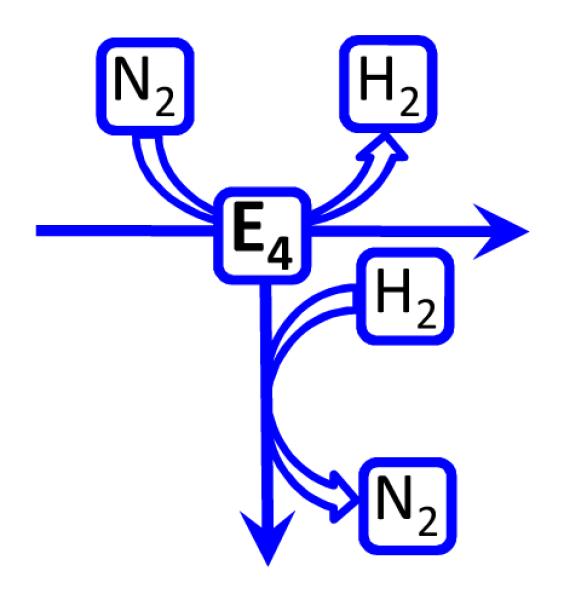

Assignment of the nitrogenase reaction pathway and unification with the LT kinetic scheme

The H and I intermediates provide‘anchor-points’ that allow assignment of the complete set of En intermediates that follow E4, 5 ≤ n ≤ 8. The loss of two reducing equivalents and two protons as H2 (eq 1) upon N2 binding to the FeMo-co of E4, leaves FeMo-co activated by two reducing equivalents and two protons. We argued that the enzyme could only be following a ‘Prompt’ (P)-Alternating pathway: when N2 binds to FeMo-co it is ‘nailed down’ by prompt hydrogenation, Fig 6, with N2 binding, H2 loss, and reduction to diazene all occurring at the E4 kinetic stage of the LT scheme.31 The identification of H with its En stage is achieved as follows. (i) As the same intermediate H is formed during turnover with the two diazenes and with hydrazine, the diazenes must have catalytically ‘caught up’ to hydrazine, and H must occur at or after the appearance of a hydrazine-bound intermediate. (ii) As noted above, H contains FeMo-co in an integer-spin (NK) state, and thus corresponds to an En state with n = odd. As H is a common intermediate that contains a bound fragment of substrate, it must, therefore, correspond to E5 or E7. But H cannot be E5 on the P pathway, for it comes before hydrazine appears (Fig 6). (iii) Thus, H corresponds to the [NH2]−-bound intermediate formed by N-N bond cleavage at the E7 stage.

Fig 6.

Integration of LT kinetic scheme with Alternating (A) pathways for N2 reduction. again denotes FeMo-co core, and substrate-derived species are drawn to indicate stoichiometry only, not mode of substrate binding. Bold arrow indicates transfer to substrate of hydride remaining after N2 binding in E4; P represents ‘Prompt’ transfer. En states, n = even, are Kramers states; n = odd are non-Kramers. MN denotes resting-state FeMo-co. Adapted from ref 29

By parallel arguments, the only possible assignment for the S = ½ state I, which we showed earlier to occur after N-N bond cleavage,31 is as E8: I must correspond to the final state in the catalytic process (Fig 6), in which the NH3 product is bound to FeMo-co at its resting redox state, prior to release and regeneration of the resting-state form of the cofactor. The trapping of a product-bound intermediate I is analogous to the trapping of a bio-organometallic intermediate during turnover of the α-70Val→Ala MoFe protein with the alkyne, propargyl alcohol; this intermediate was shown to be the allyl alcohol alkene product of reduction 36. With assignments, of E4, E7, and E8, then filling in the LT ‘boxes’ for E5, E6, is straightforward, Scheme 1, thus unifying the reaction pathway for N2 reduction with the LT scheme.

The obligatory evolution of H2 in nitrogen fixation

Although the En assignments of Fig 4 (or Fig 5) plus those of Fig 6, give proposed structures to all En states of the LT kinetic scheme (Fig 2), they have been developed through independent analyses of the two four-electron halves of the eight-electron catalytic cycle (eq 1) as linked by the E4 Janus intermediate, Fig 3: (i) the 4-electron/proton activation of FeMo-co to generate E4; (ii) the reduction of bound N2 by two of those electrons plus an additional four electrons. However, the analysis so far is silent about the mechanism that connects these two halves: the obligatory production of an H2 molecule upon N2 binding (eq 1).9 Why nitrogenase should ‘waste’ fully 25% of the ATP required for nitrogen fixation through H2 generation (eq 1) has remained a mystery, and indeed is not even accepted uniformly.3738

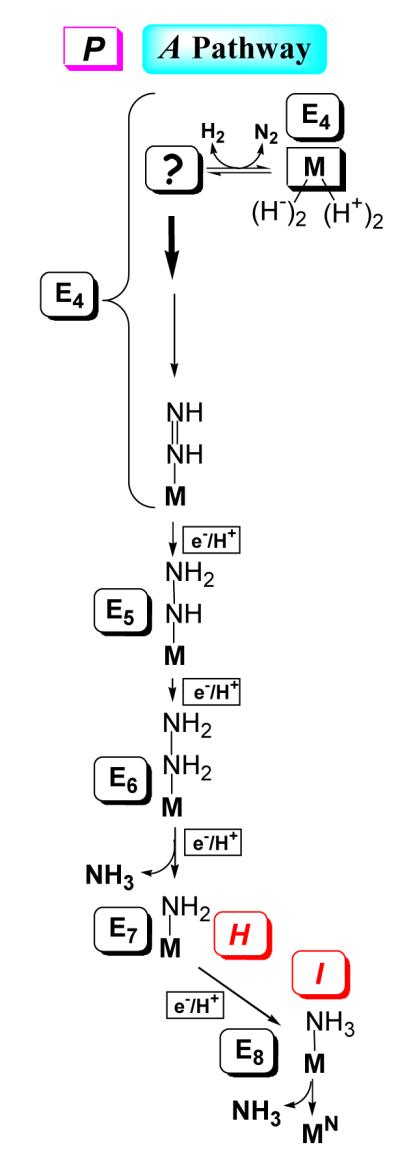

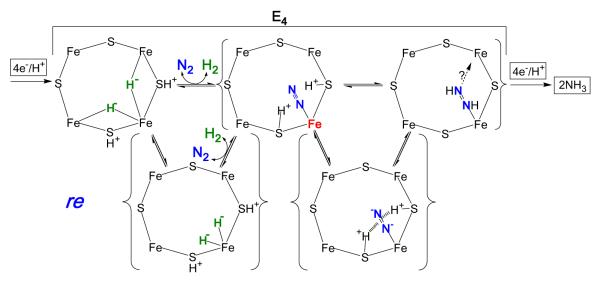

Consideration of the finding that E4 stores its four reducing equivalents as two bridging hydrides (Fig 3) within the context of the well-known organometallic chemistries of hydrides21,39 and dihydrogen,40 leads us to propose a ‘reductive elimination (re)’ mechanism,22 Fig 7, by which this state binds and activates N2 with release of H2, along with the prompt formation of FeMo-co-bound diazene (N2H2) featured in the P-A reaction pathway, Fig 6.41

Fig 7.

Visualization of re mechanism for H2 release upon N2 (blue) binding to E4. Shown, the Fe-2,3,6,7 face of resting FeMo-co; the structure of FeMo-co may vary in different stages of catalysis. The Fe shown binding N2 is presumed to be Fe6, as indicated by studies of α-70Val variants; when bold, red, formally Fe(0) (see text). The two bridging hydrides of E4 (green) are positioned as suggested by re mechanism of H2 release upon N2 binding. Alternative binding modes for N2-derived species can be envisaged.

The re mechanism for N2 binding and diazene formation

The re mechanism for H2 loss upon N2 binding begins with transient terminalization of both E4 hydrides, Fig 7, followed by reductive elimination of H2 as N2 binds, steps with strong precedence.21,39,40 Of key importance, the departing H2 carries away only two of the four reducing equivalents stored in E4, while the Fe that binds N2 becomes highly activated through formal reduction by two equivalents, for example from formal redox states of Fe(II) to Fe(0). Such a highly reduced Fe is poised to deliver the two activating electrons to N2, whose π acidity could be further enhanced by electrostatic interactions with the two sulfur-bound protons; coupled delivery of the two activating protons would yield cofactor-bound diazene. The diminished electron donation to Fe by protonated sulfides (possibly even with breakage of Fe-S bond(s)) would not only facilitate reductive elimination, but also would act to localize the added electrons on the Fe involved, instead of delocalizing the charge over the rest of the cofactor. This mechanism provides a compelling rationale for obligatory H2 formation during N2 reduction: the transient formation of a state in which an electrostatically activated N2 is bound to a highly activated, doubly-reduced site, thereby generating a state optimally activated to carry out the initial hydrogenations of N2, the most difficult process in N2 fixation.

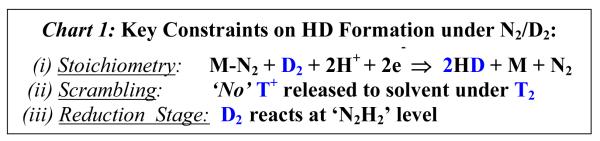

Strong support for the re mechanisms is obtained from tests against the numerous constraints provided by the interplay of N2 and H2 binding, the three principal ones being listed in Chart 1. The first test of a mechanism is that it accommodate the finding that when nitrogenase turns over in the presence of both N2 and D2, then two HD are formed through D2 cleavage and solvent-proton reduction, with the stoichiometry summarized as constraint (i) of Chart 1.3,42 Such HD formation only occurs in the presence of N2, and not during reduction of H+ or any other substrate.

Chart 1.

Key Constraints on HD Formation under N2/D2

The second key constraint was revealed by Burgess and coworkers thirty years ago; the absence of exchange into solvent of D+/T+ derived from D2/T2 gas, Chart 1, (ii).43 When nitrogenase turns over under a mixture of N2 and T2, HT is formed with stoichiometry corresponding to Chart 1, (i), but during this process only a negligible amount of T+ is released to solvent (~ 2%). A later study of α-195His- and α-191Gln-substituted MoFe proteins provided persuasive evidence that HD formation under N2/D2 requires that the enzyme be at least at the E4 redox level, with a FeMo-co-bound N-N species at the reduction level of N2H2 or beyond, corresponding to the third constraint, Chart 1, (iii).44 Constraint (iii), plus the stoichiometry of HD formation according to (i) implies a process described as,

| (2) |

and thus that N2H2 formation is reversible, as shown in Fig 7.

In the reverse of the re mechanism, shown in Fig 8, D2 binding and N2 release would generate E4 in which both atoms of D2 exist as deuteride bridges. One possible fate of this state would be relaxation to E2 with loss of HD, then to E0 with loss of the second HD, thus satisfying the stoichiometry of eq 2. If the reaction were carried out under T2, essentially no T+ would be lost to solvent because the bridging deuterides are deactivated for exchange with the protein environment and solvent, thus satisfying the ‘T+ exchange’ constraint, Chart 1.

Fig 8.

Reversal of re mechanism upon D2 binding. Details as in Fig 7

As one alternative fate of the doubly deuterated E4 formed by D2 replacement of N2, it could rebind an N2, which would merely release the D2 that had started the reverse process, creating a cycle invisible to detection. As a second alternative, the mono-deutero E2 state could acquire two additional electrons/protons to achieve the mono-deutero E4 state. As shown in Fig 8 if this state then bound N2 it would release the second HD, again without solvent exchange. Thus, the re mechanism for N2 binding and H2 release not only has the compelling chemical rationale discussed above, but also satisfies the three critical HD constraints for the various alternatives that arise when it is run in reverse, Chart 1.

But what if the exogenous D2 binds to and reacts with N2-bound FeMo-co not by the reverse of the enzymatic reaction pathway (Scheme 2), but by a ‘branch pathway’ (Scheme 3) that leads back towards the resting state by a sequence of steps different from that which generated the N2-bound state? As discussed in SI, such a branch to the re mechanism also would satisfy the HD constraints.

Schme 2.

Schme 3.

Finally, other constraints on the nitrogenase mechanism have been generated, most especially those associated with D2 binding and HD formation (See SI),3,42 and our analysis indicates that the reverse-re pathway for HD formation satisfies these, as well.

In summary, the re mechanism, Fig 7, satisfies both the stoichiometric constraint of HD formation (Chart 1, (i)) and the ‘T+’ constraint against exchange of gas-derived hydrons with solvent (Chart 1, (ii)). The re mechanism further involves D2 binding to a state at the ‘diazene level’ of reduction, as required by the constraint of eq 2 and Chart 1, (iii). Finally, to the best of our knowledge, all other constraints on the mechanism, most of which are not directly tied to D2 binding, are satisfied, as well.

This mechanism answers the long-standing and oft-repeated question, “Why does Nature ‘waste’ four ATP/two reducing equivalents through an obligatory loss of H2 when N2 binds?” The answer: reductive elimination of H2 upon binding of N2 to FeMo-co of the E4 state generates a state in which highly reduced FeMo-co binds N2, which likely is activated for reduction through electrostatic interactions with the remaining two sulfur-bound protons. Transfer of the two reducing equivalents generated by the reductive elimination, combined with transfer of the two activating protons, then forms diazene, Fig 7, in keeping with the P-A scheme of Fig 6. It appears that only through this activation is the enzyme able to hydrogenate N2.

Conclusions

The trapping and characterization of three of the eight electron-reduction stages involved in nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase (eq 1), including the ‘Janus intermediate’, E4, and the nitrogenous intermediate states H and I, have identified the ‘Prompt-Alternating (P-A)’ pathway of Fig 6 as most likely operative for nitrogenase and led to the first unification of the nitrogenase reaction pathway and the LT kinetic scheme. This unification is completed, thereby generating a first-draft mechanism for biological nitrogen fixation, with the proposed re mechanism for H2 release upon N2 reduction by nitrogenase, Fig 7, described in this Account for the first time. This mechanism will serve as a basis for future experiments to test, refine, correct as needed, and extend it.

Supplementary Material

Acknlowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH (HL 13531, BMH; GM59087, LS and DRD) and NSF (MCB 0723330, BMH). We gratefully acknowledge many illuminating discussions with friends and colleagues, most especially Profs. Richard H. Holm, Pat Holland, and Jonas Peters.

Biographical Information

Dennis R. Dean received a B.A. from Wabash College and a Ph.D. from Purdue University. He is currently a University Distinguished Professor at Virginia Tech where he also serves as the Director of the Fralin Life Science Institute and the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute.

Brian M. Hoffman was an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, received his Ph.D. from Caltech, and spent a postdoctoral year at MIT. From there he went to Northwestern University, where he is the Charles E. and Emma H. Morrison Professor in the Departments of Chemistry and of Molecular Biosciences.

Dmitriy Lukoyanov received a M.S. degree and a Ph.D. from Kazan State University. He is a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern University.

Lance C. Seefeldt received a B.S. degree from the University of Redlands and a Ph.D. from the University of California at Riverside. He was a postdoctoral fellow in the Center for Metalloenzyme Studies at the University of Georgia and is now professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Utah State University, where he recently received the D. Wynne Thorne Researcher of the Year Award.

Citations

- (1).Smil V. Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Eady RR. Structure-function relationships of alternative nitrogenases. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:3013–3030. doi: 10.1021/cr950057h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Burgess BK, Lowe DJ. Mechanism of molybdenum nitrogenase. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2983–3011. doi: 10.1021/cr950055x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM, Dean DR. Mechanism of Mo-dependent nitrogenase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:701–722. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070907.103812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hoffman BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Climbing nitrogenase: Towards the mechanism of enzymatic nitrogen fixation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:609–619. doi: 10.1021/ar8002128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM, Dean DR. Electron transfer in nitrogenase catalysis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012;16:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Thorneley RNF, Lowe DJ. Kinetics and mechanism of the nitrogenase enzyme system. In: Spiro TG, editor. Molybdenum Enzymes. Vol. 7. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1985. pp. 89–116. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wilson PE, Nyborg AC, Watt GD. Duplication and extension of the Thorneley and Lowe kinetic model for Klebsiella pneumoniae nitrogenase catalysis using a MATHEMATICA software platform. Biophys. Chem. 2001;91:281–304. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(01)00182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Simpson FB, Burris RH. Nitrogen Pressure of 50 Atmospheres Does Not Prevent Evolution of Hydrogen by Nitrogenase. Science. 1984;224:1095–1097. doi: 10.1126/science.6585956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Mortenson LE, Morris JA, Jeng D-Y. Purification, metal composition, and properties of molybdoferredoxin and azoferredoxin, two of the components of the nitrogen-fixing system of Clostridium pasteurianum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1967;141:516–22. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(67)90180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Intermediates that accumulate during CO inhibition had been trapped early on.

- (12).Cameron LM, Hales BJ. Investigation of CO binding and release from Mo-nitrogenase during catalytic turnover. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9449–9456. doi: 10.1021/bi972667c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Dilworth MJ, Fisher K, Kim CH, Newton WE. Effects on substrate reduction of substitution of histidine-195 by glutamine in the alpha-subunit of the MoFe protein of Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17495–17505. doi: 10.1021/bi9812017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Dos Santos PC, Igarashi RY, Lee H-I, Hoffman BM, Seefeldt LC, Dean DR. Substrate Interactions with the Nitrogenase Active Site. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:208–214. doi: 10.1021/ar040050z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Dos Santos PC, Mayer SM, Barney BM, Seefeldt LC, Dean DR. Alkyne substrate interaction within the nitrogenase MoFe protein. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007;101:1642–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Igarashi RY, Laryukhin M, Santos PCD, Lee H-I, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Trapping H-Bound to the Nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor Active Site During H2 Evolution: Characterization by ENDOR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6231–6241. doi: 10.1021/ja043596p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Unpublished observation.

- (18).Lukoyanov D, Yang Z-Y, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Is Mo involved in hydride binding by the four-electron reduced (E4) intermediate of the nitrogenase MoFe protein? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2526–2527. doi: 10.1021/ja910613m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Doan PE, Telser J, Barney BM, Igarashi RY, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. 57Fe ENDOR Spectroscopy and ‘Electron Inventory’ Analysis of the Nitrogenase E4 Intermediate Suggest the Metal-Ion Core of FeMo-cofactor Cycles Through Only One Redox Couple. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:17329–17340. doi: 10.1021/ja205304t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lukoyanov D, Barney BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Connecting nitrogenase intermediates with the kinetic scheme for N2 reduction by a relaxation protocol and identification of the N2 binding state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:1451–1455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610975104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Peruzzini M, Poli R, editors. Recent Advances in Hydride Chemistry. Elsevier Science B.V.; Amsterdam, Netherlands: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Crabtree RH. The organometallic chemistry of the transition metals. 5th ed Wiley; Hoboken, N.J.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Oro LA, Sola E. Mechanistic Aspects of Dihydrogen Activation and Catalysis by Dinuclear Complexes. In: Peruzzini M, Poli R, editors. Recent Advances in Hydride Chemistry. Elsevier Science B.V.; Amsterdam, Netherlands: 2001. pp. 299–328. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Yoo SJ, Angove HC, Papaefthymiou V, Burgess BK, Muenck E. Moessbauer study of the MoFe protein of nitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii using selective 57Fe enrichment of the M-centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4926–4936. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lancaster KM, Roemelt M, Ettenhuber P, Hu Y, Ribbe MW, Neese F, Bergmann U, DeBeer S. X-ray Emission Spectroscopy Evidences a Central Carbon in the Nitrogenase Iron-Molybdenum Cofactor. Science. 2011;334:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1206445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Spatzal T, Aksoyoglu M, Zhang LM, Andrade SLA, Schleicher E, Weber S, Rees DC, Einsle O. Evidence for Interstitial Carbon in Nitrogenase FeMo Cofactor. Science. 2011;334:940–940. doi: 10.1126/science.1214025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Neese F. The Yandulov/Schrock cycle and the nitrogenase reaction: Pathways of nitrogen fixation studied by density functional theory. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:196–199. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Schrock RR. Catalytic Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia at a Single Molybdenum Center. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:955–962. doi: 10.1021/ar0501121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kastner J, Blochl PE. Ammonia production at the FeMo cofactor of nitrogenase: results from density functional theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2998–3006. doi: 10.1021/ja068618h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hinnemann B, Norskov JK. Catalysis by Enzymes: The Biological Ammonia Synthesis. Top. Catal. 2006;37:55–70. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lukoyanov D, Dikanov SA, Yang Z-Y, Barney BM, Samoilova RI, Narasimhulu KV, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. ENDOR/HYSCORE studies of the common intermediate trapped during nitrogenase reduction of N2H2, CH3N2H, and N2H4 support an alternating reaction pathway for N2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11655–11664. doi: 10.1021/ja2036018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Dilworth MJ, Eady RR. Hydrazine is a product of dinitrogen reduction by the vanadium-nitrogenase from Azotobacter chroococcum. Biochem. J. 1991;277:465–468. doi: 10.1042/bj2770465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Münck E, Ksurerus K, Hendrich MP. Combining Mössbauer spectroscopy with integer spin electron paramagnetic resonance. Methods Enzymol. Part C. 1993;227:463–479. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)27019-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Lukoyanov D, Yang Z-Y, Barney BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Unification of Reaction Pathway and Kinetic Scheme for N2 Reduction Catalyzed by Nitrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:5583–5587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202197109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hoffman BM. ENDOR and ESEEM of a non-Kramers doublet in an integer-spin system. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:11657–11665. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Lee H-I, Igarashi RY, Laryukhin M, Doan PE, Dos Santos PC, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. An organometallic intermediate during alkyne reduction by nitrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9563–9569. doi: 10.1021/ja048714n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).As summarized by Peters and Mehn, many of the attempts to understand nitrogen fixation theoretically treat a six-electron stoichiometry, and thus implicitly reject this central mechanistic feature of the LT scheme.

- (38).Peters JC, Mehn MP. Bio-organometallic Approaches to Nitrogen Fixation Chemistry. In: Tolman WB, editor. Activation of small molecules : organometallic and bioinorganic perspectives. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2006. pp. 81–116. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ballmann J, Munha RF, Fryzuk MD. The hydride route to the preparation of dinitrogen complexes. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.) 2010;46:1013–1025. doi: 10.1039/b922853e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kubas GJ. Fundamentals of H2 Binding and Reactivity on Transition Metals Underlying Hydrogenase Function and H2 Production and Storage. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4152–4205. doi: 10.1021/cr050197j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).An alternative ‘hydride protonation (hp) mechanism is considered in SI, where it is also shown that hp does not satisfy known experimental constraints.

- (42).Li J, Burris RH. Influence of pN2 and pD2 on HD formation by various nitrogenases. Biochemistry. 1983;22:4472–80. doi: 10.1021/bi00288a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Burgess BK, Wherland S, Newton WE, Stiefel EI. Nitrogenase reactivity: insight into the nitrogen-fixing process through hydrogen-inhibition and HD-forming reactions. Biochemistry. 1981;20:5140–6. doi: 10.1021/bi00521a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Fisher K, Dilworth MJ, Newton WE. Differential effects on N2 binding and reduction, HD formation, and azide reduction with α-195His- and α-191Gln-substituted MoFe proteins of Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15570–15577. doi: 10.1021/bi0017834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.