Abstract

The allatostatin receptor (AlstR)/ligand inactivation system enables potent regulation of neuronal circuit activity. To examine how different cell types participate in memory formation, we have used this system through Cre-directed, cell-type specific expression in mouse hippocampal CA1 in vivo and examined functional effects of inactivation of excitatory vs. inhibitory neurons on memory formation. We chose to use a hippocampus-dependent behavioral task involving location-dependent object recognition (LOR). The double transgenic mice, with the AlstRs selectively expressed in excitatory pyramidal neurons or inhibitory interneurons, were cannulated, targeting dorsal hippocampus to allow the infusion of the receptor ligand (the allatostatin [AL] peptide) in a time dependent manner. Compared to control animals, AL-infused animals showed no long-term memory for object location. While inactivation of excitatory or inhibitory neurons produced opposite effects on hippocampal circuit activity in vitro, the effects in vivo were similar. Both types of inactivation experiments resulted in mice exhibiting no long-term memory for object location. Together, these results demonstrate that the Cre-directed, AlstR-based system is a powerful tool for cell-type specific manipulations in a behaving animal and suggest that activity of either excitatory neurons or inhibitory interneurons is essential for proper long-term object location memory formation.

To understand how different neuronal cell types within cortical networks contribute to a complex behavior, it is necessary to have cell-type as well as spatial and temporal control over neuronal activity. By the use of a combined genetic and ligand delivery approach in the form of the allatostatin receptor/allatostatin (AlstR/AL) system it is possible to achieve all of the above requirements (Ikrar et al. 2012). Allatostatin is an insect peptide, with no target in mammalian cells (Birgul et al. 1999), which binds to the allatostatin receptor, a G-protein-coupled receptor (Lenz et al. 2000). The AlstR system activates G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels (Dascal 1997; Coward et al. 1998; Redfern et al. 1999; Mark and Herlitze 2000), which are abundantly expressed in the mammalian brain (Karschin et al. 1996). AL treatment in AlstR expressing neurons leads to membrane potential hyperpolarization and prevention of action potentials, thus suppressing neuronal activity. In prior studies in vertebrates, the AlstR system has been used to inactivate neurons in both living slice preparations and intact brain circuits of anesthetized and awake animals (Lechner et al. 2002; Tan et al. 2006, 2008; Wehr et al. 2009; Zhou et al. 2009; Ikrar et al. 2012). As it is particularly related to the present study, this genetic system has been used to study fear memory, in which the receptors were virally expressed in a subset of lateral amygdala neurons to modulate the allocation of fear memory (Zhou et al. 2009). In this study, we used this approach in vivo, in the hippocampal region of behaving animals, to determine the functional roles of specific neuronal types in object location memory.

To achieve targeted AlstR expression with cell-type specificity, we employed a Cre-directed, double transgenic mouse approach by crossing a mouse line (R26-AlstR) carrying the AlstR gene with a floxed STOP-cassette (Ikrar et al. 2012) with the mouse lines expressing the Cre recombinase in excitatory or inhibitory neurons (i.e., Emx1-Cre or Dlx5/6-Cre, respectively). There are different cell types in cortical circuits, and each type is likely to have a unique role in the neural network related to memory behavior. For example, blocking of synaptic transmission in parvalbumin-expressing inhibitory interneurons in hippocampal CA1 affects spatial working memory, but not reference memory (Murray et al. 2011), which illustrates how cell-specific inactivation can reveal new insights into learning and memory. In the present study, we focus on the role of excitatory neurons and inhibitory interneurons within the dorsal hippocampus with respect to object–location memory formation.

Although we and others have previously demonstrated that the object location task is hippocampus dependent (Balderas et al. 2008; Winters et al. 2008; Clark and Squire 2010; Roozendaal et al. 2010; Barrett et al. 2011; Haettig et al. 2011; McQuown et al. 2011), the differential roles of different neuronal types in object location memory remain unknown. Through site-specific delivery of the AL peptide in adult mice, we have examined the effects of inactivation of excitatory neurons or inhibitory interneurons on the acquisition/consolidation of memory formation. We demonstrate that the AlstR/AL system can be used in vivo, in behaving animals, to determine the role of specific cell types in memory formation. We have found that both excitatory neurons and inhibitory interneurons are required for the acquisition/consolidation of object location memory, even though inactivation of excitatory or inhibitory neurons produced opposite effects on hippocampal circuit activity in vitro.

Results

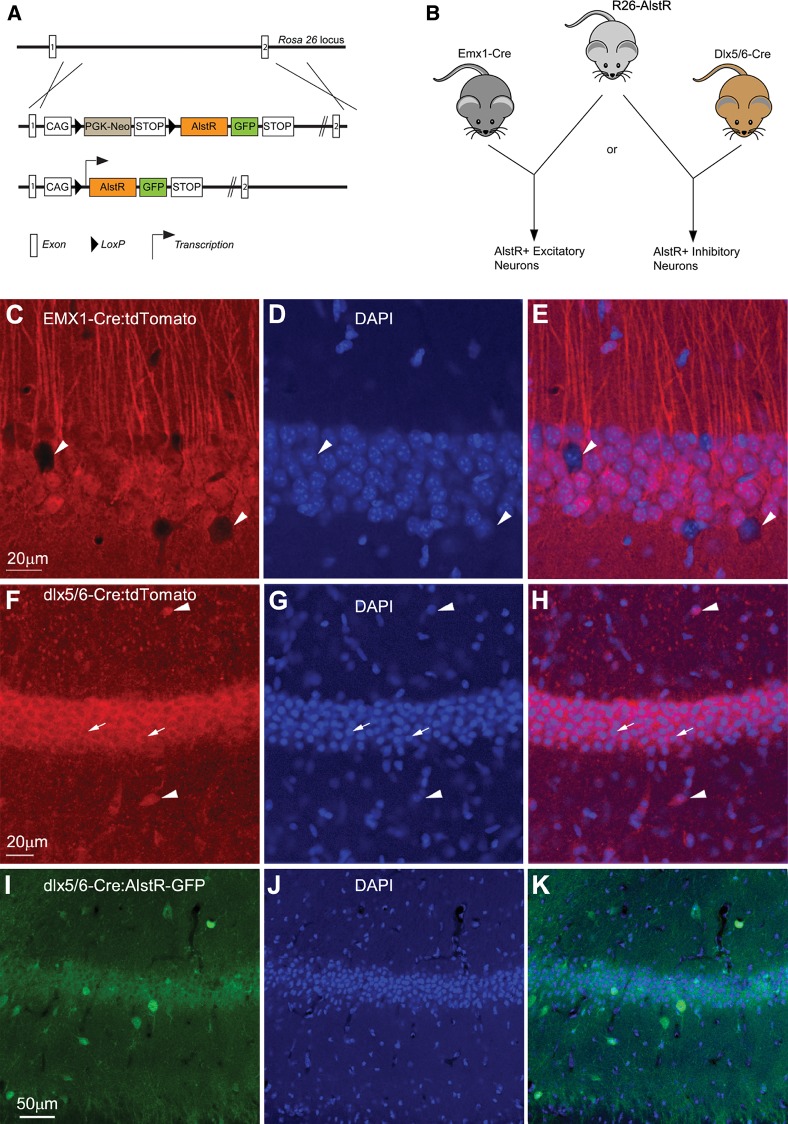

We generated Cre-directed, cell-type specific expression of AlstRs in mouse hippocampal CA1 area through a double-transgenic mouse approach by crossing the R26-AlstR mouse line conditionally expressing AlstRs following Cre recombination with the Emx1-Cre mouse line (Guo et al. 2000) or the Dlx5/6-Cre mouse line (Fig. 1A,B; Monory et al. 2006). We first confirmed the specificity and efficiency of these Cre mouse lines in achieving cell-type specific gene expression. As demonstrated in Figure 1C–H, through the use of a tdTomato Cre reporter line (Madisen et al. 2010), the Emx1-Cre mouse expresses Cre in essentially all excitatory pyramidal neurons in CA1 (Fig. 1C–E), while the Dlx5/6-Cre mouse expresses Cre specifically in inhibitory interneurons (Fig. 1F–H). Furthermore, as GFP and AlstR are coexpressed from the same transgene (Fig. 1A), direct GFP fluorescence or the GFP immunostaining reflected similar cellular distributions of AlstR in the mouse slices of Emx1-Cre:AlstR or Dlx5/6-Cre:AlstR (Fig. 1I–K; Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cre-directed double transgenic approach of targeting AlstR expression to either excitatory or inhibitory neurons. (A) Schematic map of the transgenic region in the R26-AlstR mouse line (Ikrar et al. 2012) before and after Cre mediated excision of the loxP-stop-loxP cassette. (B) Cre-directed, double-transgenic mouse strategy through crossing the R26-AlstR mouse with the Emx1-Cre mouse line (Guo et al. 2000) or the Dlx5/6-Cre mouse line (Monory et al. 2006) in order to achieve targeted AlstR expression to excitatory or inhibitory neurons, respectively. (C–E) Confirmation of the specificity and efficiency of Cre expression in hippocampal excitatory pyramidal neurons. Data images are from hippocampal CA1 of a double transgenic mouse obtained by crossing the Emx1-Cre to a Rosa-CAG-LSL-tdTomato Cre reporter line (Madisen et al. 2010). (C) Confocal microscopy of a tdTomato-expressing section with many neurons appearing to be pyramidal neurons morphologically. The white arrowheads point to the somata which may represent presumptive inhibitory hippocampal neurons. (D) Confocal microscopy of DAPI staining of the same CA1 region. (E) The overlay of C and D. (F–H) Confirmation of the specificity and efficiency of Cre expression in hippocampal inhibitory neurons. Data images are from hippocampal CA1 of a double transgenic mouse obtained by crossing the Dlx5/6-Cre to the Rosa-CAG-LSL-tdTomato Cre reporter line. (F) Confocal microscopy of a tdTomato-expressing section (some presumptive inhibitory neurons are indicated by the white arrowheads). The stratum pyramidale appears to be full of tdTomato-expressing axonal terminals from inhibitory neurons. The thin white arrows point to the hollow areas which may represent the somata of excitatory hippocampal neurons. (G) Confocal microscopy of DAPI staining of the same CA1 region. (H) The overlay of F and G. (I) Confocal microscopy of GFP immunostaining in a Dlx5/6-Cre:AlstR mouse slice. GFP and AlstR are coexpressed from the transgene (see A). (J) Confocal microscopy of DAPI staining of the same CA1 region. (K) The overlay of I and J. Note different scales for C–E, F–H, and I–K.

The AlstR-based system has been developed for selective and reversible silencing of mammalian neurons (Tan et al. 2006; Wehr et al. 2009; Ikrar et al. 2012), and can effectively regulate cortical circuit activity at single-cell and neuronal population levels. However, given that this molecular inactivation system had not been used in the hippocampus before, we first examined the effectiveness of AlstR-mediated inactivation on hippocampal CA1 network activity in slice preparations prior to extending this system to in vivo behavioral studies. We used fast VSD imaging of evoked neural activity to evaluate AlstR-mediated inhibition on CA1 circuit activity.

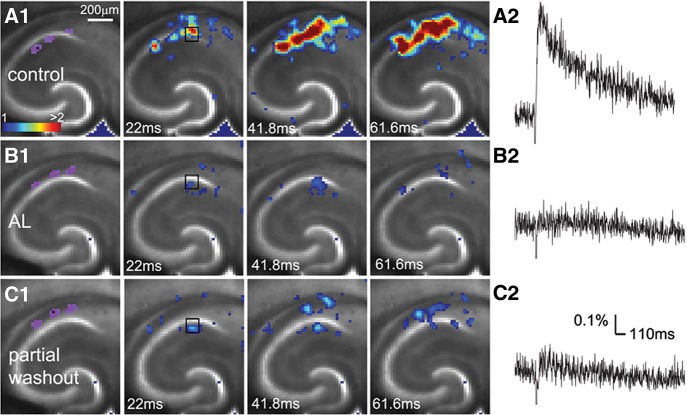

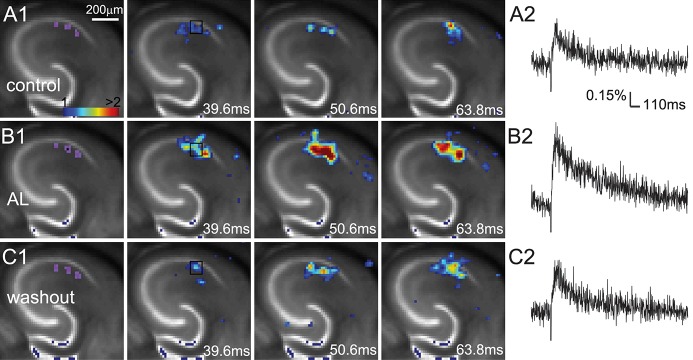

Our slice experiments demonstrate that the AlstR system enables robust regulation of hippocampal CA1 excitability in a cell-type specific manner. The VSD imaging can monitor neuronal activity in a large area simultaneously, with changes in optical signals closely correlating with membrane potential depolarization of neuronal ensembles (Xu et al. 2010; Xu 2011). During VSD imaging experiments, living hippocampal slices were stained with VSD; the CA1 region was stimulated with either electrical stimulation or laser photostimulation, and circuit activation directly visualized and measured by fast VSD imaging (Fig. 2A). AlstR-mediated inactivation of excitatory pyramidal neurons clearly suppresses excitatory population activity (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. 2), as the bath application of 1 µM AL strongly inhibited photostimulation or electrical stimulation-evoked excitatory population activity across Emx1-Cre:AlstR mouse slices in which excitatory pyramidal neurons selectively express AlstRs. On average, for the Emx1-Cre:AlstR slices, the total response amplitude during AL application was reduced to 27.9% ± 25.2% (mean ± SD, N = 6 slices pooled from both photostimulation and electrical stimulation) relative to control (P < 0.05). Control slices without AlstR expression (N = 3) were not affected with the AL application. Conversely, AlstR-mediated inactivation of inhibitory neurons enhances excitatory population activity. Photostimulation-evoked response in the presence of AL was augmented in Dlx5/6-Cre:AlstR mouse slices in which GABAergic neurons are targeted to express AlstRs (Fig. 3A,B). The response increase of VSD activation in the presence of AL, compared to control, was 325.9% ± 226.3% for the Dlx5/6-Cre:AlstR slice (N = 5; P < 0.05). Note that the AlstR-mediated effects on CA1 circuit activity could be reversed with the washout of the AL peptide (Figs. 2C, 3C; Supplemental Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

AlstR-mediated suppression of excitatory neuronal population activity in an Emx1-Cre:AlstR mouse slice. (A1) Time series data of VSD imaging of photostimulation-evoked activity in hippocampal CA1 in normal ACSF. The color scale codes VSD signal amplitude expressed as standard deviation (SD) multiples above the mean baseline. The sites of photostimulation in CA1 can be identified by the laser excitation artifact (purple) in the first frame. The data images were obtained by averaging the trials in response to three different stimulation sites. Color-coded excitatory activity is superimposed on the background slice image. (A2) The time course of VSD signal (in the percent change of pixel intensity [ΔI/I%]) from the region of interest (ROI) indicated by the small rectangle in the second image frame in A1. (B1) Time series of network activity in the same slice in the presence of the AL peptide, with excitatory response being clearly reduced compared to control. (B2) The time course of VSD signal (in ΔI/I%) from the ROI indicated by the small rectangle in the second image frame in B1. (C1) Time series of network activity in the same slice after partial washout of the AL peptide. (C2) The time course of VSD signal (in ΔI/I%) from the ROI indicated by the small rectangle in the second image frame in C1.

Figure 3.

AlstR-mediated inhibition of GABAergic inhibitory neurons increases excitatory population activity in a Dlx5/6-Cre:AlstR mouse slice. (A1–C1) Time series data of VSD imaging of photostimulation-evoked activity in hippocampal CA1 in normal ACSF, in the presence and after washout of AL, respectively. The sites of photostimulation in CA1 can be identified by the laser excitation artifact (purple) in the first frame. The data images were obtained by averaging the trials in response to three different stimulation sites. (A2–C2) The time course of VSD signal (in the percent change of pixel intensity [ΔI/I%]) from the ROI indicated by the small rectangle in the second image frame in A1–C1, respectively.

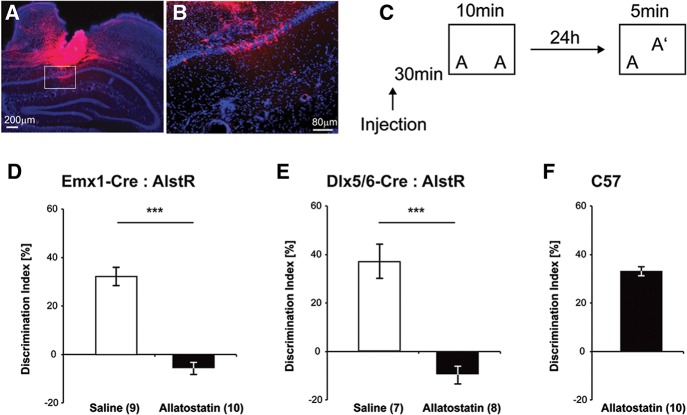

To test the neuronal inactivation of the AlstR/AL system in vivo we crossbred the R26-AlstR mouse with the Emx1-Cre mouse to express AlstR in excitatory neurons. After confirming the genotype, these mice underwent cannulation surgery targeting the dorsal hippocampus 2 wk prior to training. Figure 4, A and B, shows the specific targeting of dorsal CA1 region. We have previously shown that affecting even a focal region of CA1 is sufficient to impair long-term memory for object location (Barrett et al. 2011). In this task, two identical objects are presented during training and the mice were tested 24 h later with one object moved to a novel location (Fig. 4C). Everything was performed in a counterbalanced manner. If the location of the object is remembered, then the mouse preferentially explores the familiar object in the novel location, resulting in a higher discrimination index (as described by Roozendaal et al. 2010). Because the half-life of AL is estimated to be 1–2 h before its degradation or removal in vivo (Tan et al. 2006), pre-training delivery of AL is likely to only affect acquisition/consolidation but not retrieval of memory tested 24 h later.

Figure 4.

Allatostatin infusion impairs object location memory in two mouse lines with cell-type specific AlstR expression (Emx1-Cre:AlstR and Dlx5/6-Cre:AlstR). (A,B) Histological verification of the cannulation placement and infusion site. (A) The image of a DAPI-stained section from the cannulation center, superimposed with the Alexa Fluor 594 fluorescent labeling (red) in the tissue, while B shows the enlarged region (indicated by the white rectangle in A) in CA1. Note the dye diffusion in the neocortical region above CA1; however, the potential allatostatin diffusion into the cortical region would unlikely affect the mouse behavior of object location recognition, which is hippocampus dependent (see similar issues in Vecsey et al. [2007] and McQuown et al. [2011]). (C) Schematic diagram for the object location recognition task. Letters A in the boxes indicate positioning of the objects. In each experiment, the mice were fitted with bilateral hippocampal cannulae and allowed to recover from surgery. They were handled and habituated to the context prior to a 10-min training. The animals received bilateral injections of 1 µM allatostatin or saline 30 min prior to training. (D) For this experiment, the Emx1-Cre:AlstR mice expressing the AlstRs in excitatory neurons were used. During a 24-hr retention test, the mice that received allatostatin 30 min prior to training showed no preference for the moved object in contrast to the saline treated mice. (E) For this experiment, the Dlx5/6-Cre:AlstR mice expressing the AlstRs in inhibitory interneurons were used. During a 24-hr retention test, the mice that received allatostatin 30 min prior to training displayed no preference for the moved object in contrast to the saline treated mice. (F) In this experiment, wild type C57Bl/6J mice were treated with allatostatin 30 min prior to training. These mice showed equivalent preference for the moved object as the control animals (saline treated) shown in D and E, but changed their preference significantly as compared to training. (***) P < 0.001. Numbers in parentheses indicate the treatment sample size (n).

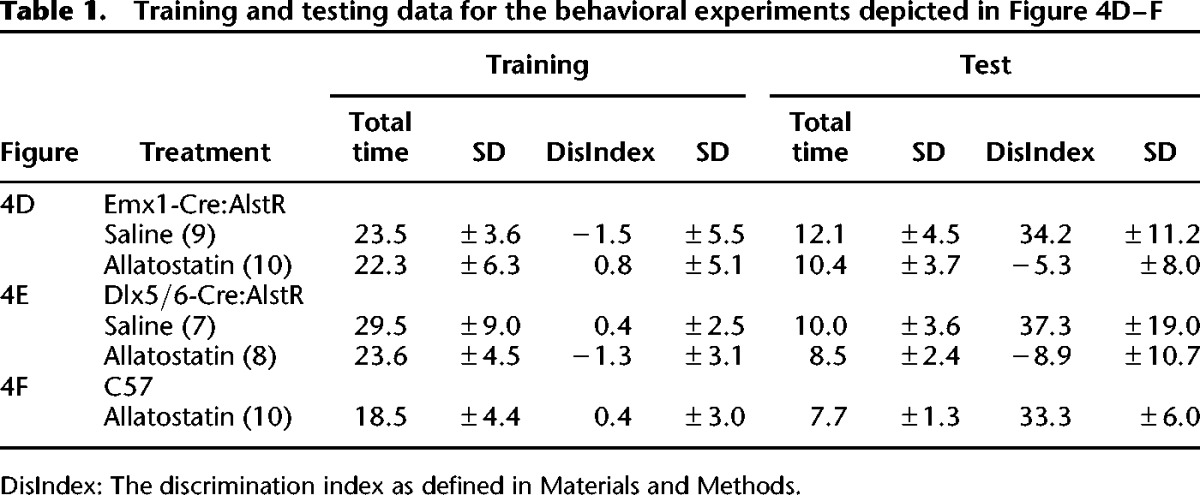

In the experiments shown in Figure 4, we used a 10-min training period that results in a robust 24-h memory (Stefanko et al. 2009). Thirty minutes prior to training, mice received a bilateral injection of 0.5 µL into the dorsal hippocampus of either saline (vehicle; n = 9) or allatostatin (1 µM dissolved in saline; n = 10). The mice were tested 24 h later. Allatostatin-treated mice exhibited no significant long-term memory as compared to vehicle-treated controls (t(17) = 7.991; P < 0.001) (Fig. 4D). There were no differences in total exploration times between groups during testing (t(17) = 0.872; P = 0.395) or training (t(17) = 0.381; P = 0.708) (for data see Table 1). These results suggest that excitatory neurons in the dorsal hippocampus are necessary for long-term object location memory formation.

Table 1.

Training and testing data for the behavioral experiments depicted in Figure 4D–F

In the next experiments, we examined the role of inhibitory interneurons in memory formation using R26-AlstR × Dlx5/6-Cre mice, which express AlstR in GABAergic inhibitory interneurons. The mice were cannulated, handled and habituated as described above. The mice received a 0.5 µL bilateral injection 30 min prior to training into the dorsal hippocampus of either saline (vehicle; n = 7) or allatostatin (1 µM; n = 8). The mice were tested 24 h later. AL-treated mice exhibited no long-term memory for object location as compared to vehicle-treated mice (Mann–Whitney U = 0.000; P < 0.001 two-tailed) (Fig. 4E). There were no differences in total exploration times between groups during testing (t(13) = 0.910; P = 0.379) or training (Mann–Whitney U = 16.000; P = 0.189) (for data see Table 1). These results suggest that inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal hippocampus are also necessary for long-term object location memory formation.

To examine whether allatostatin alone affects memory formation, we treated wild type C57Bl/6J mice (n = 10) with 0.5 µL bilateral injections of the peptide (1 µM), as in the experiments above (Fig. 4F). Comparison between object preference during training and testing shows a significant change of preference toward the moved object (t(18) = 14.704, P < 0.001), indicating that allatostatin alone does not impair long-term object location memory formation.

Discussion

In this study, we used the AlstR/AL system to specifically inactivate excitatory neurons or inhibitory interneurons in hippocampal CA1 of behaving mice to determine their functional roles in the acquisition/consolidation of object location memory. As predicted, the AL application resulted in significantly reduced photostimulation-evoked responses in slices from hippocampus of Emx1-Cre:AlstR mice. In contrast, in slices from hippocampus of Dlx5/6-Cre:AlstR mice, application of AL peptide resulted in significantly increased photostimulation-evoked responses. With regard to behavior, inactivation of either Emx1-Cre expressing excitatory neurons or Dlx5/6-Cre expressing inhibitory interneurons resulted in significantly impaired hippocampus-dependent long-term memory for object location. In fact, those animals receiving the AL peptide formed no long-term memory as compared to vehicle treated controls, and the AL peptide alone did not impair long-term memory in wild type mice not expressing AlstR.

As the coordination and interaction between different cell types in the hippocampus is essential for proper network function and experience-dependent modifications to the network that ultimately guides behavior, it is not too surprising that both excitatory neuronal function and inhibitory interneuronal function are required for long-term memory formation. Many studies have targeted excitatory neurons in the hippocampus with regard to learning and memory, especially through the use of the CaMKIIα promoter in transgenic mice (Abel and Lattal 2001; Nakashiba et al. 2008), but more attention has been shifted to GABA-releasing inhibitory interneurons as their interactions with excitatory neurons are crucial to normal circuit activity (Klausberger et al. 2003; Bartos et al. 2007; Buzsaki et al. 2007; Royer et al. 2012). Even though disruption of GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus is often associated with neurological disorders, especially temporal lobe epilepsy (Santhakumar and Soltesz 2004; Cossart et al. 2005; Freund and Katona 2007), recent studies have revealed specific and defined functional roles of inhibitory neurons in learning and memory (Murray et al. 2011). More specifically, parvalbumin-positive CA1 interneurons have been shown to be required for spatial working, but not reference memory (Murray et al. 2011).

We have chosen to use the AlstR-based genetic method for cell-type specific manipulation for the following considerations. (1) Conventional methods such as lesions and pharmacological applications can allow manipulation of neuronal activity, but these methods typically do not have the resolution required to modulate specific cell types. (2) As demonstrated in previous studies and confirmed in this study, the AlstR system has the required merits and applicable features as a potent molecular tool for regulation of neuronal circuit excitability. AlstR-mediated inactivation persists without desensitization in the continued presence of AL (Tan et al. 2006; Ikrar et al. 2012). In comparison, optical inactivation of neurons with high temporal precision can be effectively achieved by using the halorhodopsin or Arch system (Han and Boyden 2007; Chow et al. 2010). Even though no ligand is needed, strong illumination over the course of several minutes may cause phototoxicity and neuronal damage (Diester et al. 2011), and this makes it difficult to apply optical silencing to long-lasting behavioral experiments. One existing approach similar to the use of the nonendogenous AlstR system is to use genetically engineered G-protein-coupled-receptors of mammalian neurons (Conklin et al. 2008; Alexander et al. 2009). For example, muscarinic acetylcholine receptors have been genetically modified to generate a family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that are activated solely by a pharmacologically inert drug-like compound (clozapine-N-oxide). Similar to the AlstR, the Gi-coupled designer receptor (hM4D) demonstrates its ability to induce membrane hyperpolarization and neuronal silencing in vitro and in vivo (Armbruster et al. 2007; Ferguson et al. 2011). The designer drug ligand can be administered in the periphery and cross the blood–brain barrier to access receptors in deep brain structures. However, systemic administration of the ligand would result in the loss of precise temporal control. As the AL peptide does not cross the blood–brain barrier in the current form, we used cannulation methods to directly infuse the ligand site-specifically (dorsal hippocampus) with temporal control that avoids developmental effects. Our present study, for the first time, demonstrates the applicability of the AlstR system for hippocampus-dependent memory tasks, and we believe that it can be a powerful tool for many other types of similar behavioral experiments.

Through AlstR-mediated neuronal inactivation in hippocampal CA1, we found that inactivation of either excitatory or inhibitory cell types disrupted location-dependent object recognition in the mouse, which indicates that both excitatory neurons and inhibitory interneurons are important in contributing to long-term memory formation. The in vivo behavioral finding provides new insight into the working neural circuits, particularly in consideration of our slice imaging experiments in which inactivation of excitatory or inhibitory neurons produced opposite effects on hippocampal circuit activity in vitro. Although inactivation of either cell type in hippocampal CA1 affects the population activity in CA1 to cause memory impairment, the behavioral deficits are likely due to quite different mechanisms. Inhibiting excitatory neurons in CA1 would directly affect the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in hippocampus-dependent consolidation as well as the downstream communication of information. The role of excitatory neurons in hippocampus-dependent memory has been explored in depth (McHugh et al. 1996; Tsien et al. 1996; Abel and Lattal 2001). In contrast, the role of inhibitory neurons in the CA1 area or in the hippocampus as a whole system is not well established, especially complicated by diverse types of inhibitory interneurons involved in hippocampal network activity (Klausberger and Somogyi 2008). Disrupting inhibitory interneuron activity in CA1 could potentially result in loss of local circuit inhibition to overamplify or miscoordinate the excitatory population activity of CA1 as well as the activity of the downstreaming circuits of CA1. Consistent with the known roles of GABAergic transmission and inhibitory synaptic plasticity in hippocampus-dependent memory (Cui et al. 2008; Ruediger et al. 2011), a recent study (Ran et al. 2012) showed that persistent long-term potentiation (LTP) in hippocampal interneurons can play a role in constraining pyramidal cell ensembles recruited during learning, as well as pyramidal cell LTP. Nevertheless, much more work is needed to completely understand the interplay between cell types in establishing synaptic plasticity resulting in long-term memory processes.

Finally, while we have compared the overall effects of inactivation of excitatory neurons vs. inhibitory neurons on the animal’s object location memory, diverse subtypes of inhibitory interneurons in the hippocampus likely have different functions within CA1 circuits. With the availability of many new interneuron-specific Cre driver lines (Taniguchi et al. 2011), in future we will be able to examine the role of specific inhibitory neuronal subtypes in long-term memory formation.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

In this study, we used an AlstR mouse line conditionally expressing AlstRs following Cre recombination (Ikrar et al. 2012; Fig. 1). This AlstR mouse line (R26-AlstR) was created by using the same targeting vector of transgene as for the AlstR 192 strain (Gosgnach et al. 2006), but the vector was inserted at the Rosa26 locus to drive more stable expression. To achieve Cre-directed expression of AlstRs, the R26-AlstR mouse line was crossbred with an Emx1-Cre mouse line (Guo et al. 2000; Gorski et al. 2002) or a Dlx5/6-Cre mouse line (Monory et al. 2006). Emx1 is a mouse homologue of the Drosophila homeobox gene empty spiracles and its expression is largely restricted to excitatory neurons in the developing and adult cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Guo et al. 2000; Gorski et al. 2002; Kuhlman and Huang 2008); the Emx1-Cre mouse line was created with the Cre gene placed directly downstream of the Emx1 promoter (Guo et al. 2000). Dlx is a family of homeodomain transcription factors which are related to the Drosophila distal-less (Dll) gene (Panganiban and Rubenstein 2002); in the Dlx5/6-Cre mouse, expression of Cre is directed to virtually all forebrain GABAergic neurons during embryonic development by the I56i and I56ii enhancers from the zebrafish dlx5a/dlx6a intergenic region (Monory et al. 2006). For control experiments to test the effects of AL infusion in wild type hippocampus (Fig. 4F), C57Bl/6J mice (male) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Mice were 8–12 wk of age at the time of the experiment and had free access to food and water in their home-cages. Lights were maintained on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, with all behavioral testing carried out during the light portion of the cycle. All experiments were conducted according to National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal care and use and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Irvine.

Slice imaging experiments

Before extending the AlstR system to the in vivo behavioral work, we examined the effectiveness of AlstR-mediated inactivation on hippocampal CA1 network activity in slice preparations. To prepare living brain slices, the double transgenic mouse pups (postnatal days 16–21) or control pups (AlstR or Cre mouse pups) were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (>100 mg/kg, i.p.) and rapidly decapitated, and their brains removed. For fast voltage-sensitive dye (VSD) imaging experiments, hippocampal slices were cut in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) (85 mM NaCl, 75 mM sucrose, 2.5 mM KCl, 25 mM glucose, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, and 24 mM NaHCO3) with a broad-spectrum excitatory amino acid antagonist kynurenic acid (0.3 mM). After the initial incubation at 32°C, slices were transferred for dye staining at room temperature for 1 h in the ACSF and 0.02 mg/mL of the absorption voltage-sensitive dye NK3630 (Nippon Kankoh-Shikiso Kenkyusho Co. Ltd.) and then maintained in the recording ACSF without kynurenic acid before use. Throughout the cutting, incubation, staining, and recording, the solutions were continuously supplied with 95% O2–5% CO2.

Our overall imaging system was described previously (Xu et al. 2010; Xu 2011). The solution was fed into the slice recording chamber through a pressure-driven flow system with pressurized 95% O2–5% CO2 with a perfusion flow rate of about 2 mL/min. Either electrical stimulation or photostimulation via glutamate uncaging was used to evoke excitatory activity in the slices. Electrical stimulation (500 μA, 1 msec) via a bipolar stimulating electrode (FHC) was delivered to a CA1 portion of the slice. For photostimulation experiments, stock solution of MNI-caged-l-glutamate (Tocris Bioscience) was added to 20 mL of ACSF for a concentration of 0.2 mM caged glutamate. Caged glutamate was present in the bath solution, and only turned active through focal UV photolysis. The slice image was acquired by a high resolution digital CCD camera, which in turn was used for guiding and registering photostimulation sites. A laser unit (DPSS Lasers) was used to generate a 355-nm UV laser for glutamate uncaging. Short pulses of laser flashes (1 msec, 20 mW) were controlled by using an electro-optical modulator and a mechanical shutter. The laser beam formed uncaging spots, each approximating a Gaussian profile with a width of ∼100 µm laterally at the focal plane. To examine AlstR-mediated inactivation, the ligand AL was added into the recording solution. Although nanomolar concentrations of AL could inactivate isolated cultured AlstR-expressing neurons (Lechner et al. 2002), 1 µM AL was used for facilitating the ligand penetration deep into the slices and increasing temporal speeds of the ligand infusion. The AL application for 15 min was used to produce full AlstR effects, while the washout of 20 min was used to remove the added AL from the recording solution.

During VSD imaging experiments, 705-nm light transilluminated brain slices and voltage-dependent changes in the light absorbance of the dye were captured by the MiCAM02 fast imaging system (SciMedia USA Ltd.). The illumination was supplied by optically filtering white light produced by an Olympus tungsten–halogen lamp up to 100 watts of power. Optical recording of VSD signals was performed under the 2× or 4× objective with a sampling rate of 2.2 msec per frame (frame resolution 88 [w] × 60 [h] pixels). Under the 4× objective, the field of view covered the area of 1.28 × 1.07 mm2 with a spatial resolution of 14.6 × 17.9 µm2/pixel. For the imaging of evoked excitatory activity with and without the AL application, VSD imaging acquisition was triggered and synchronized with electrical stimulation or laser photostimulation at specified cortical sites. For each trial, the VSD imaging duration was 2000 frames including 500 baseline frames with an intertrial interval of 12 sec.

VSD signals were originally measured by the percent change in pixel light intensity [ΔI/I%; the percent change in the intensity (ΔI) at each pixel relative to the initial intensity (I)]. In addition, the mean and standard deviation of the baseline activity of each pixel across the 50 frames preceding photostimulation were calculated, and VSD signal amplitudes were then expressed as standard deviation (SD) multiples above the mean baseline signal for display and quantification. The activated pixel was empirically defined as the pixel with amplitude ≥1 SD above the baseline mean of the corresponding pixel’s amplitude (equivalent to the detectable signal level in the original VSD maps of ΔI/I%). VSD images were smoothed by convolution with a Gaussian spatial filter (kernel size: 5 pixels; standard deviation [σ]: 1 pixel) and a Gaussian temporal filter (kernel size: three frames; δ: one frame). To examine AlstR-mediated effects on photostimulation-evoked VSD responses, the total response amplitudes across the 10 frames around the peak VSD activation (e.g., at 55 msec after photostimulation) were measured for comparison across control, AL application, and washout. Images were displayed and analyzed using custom-made MATLAB programs.

Object recognition

The object location task used is described in Roozendaal et al. (2010) and McQuown et al. (2011). Prior to training, mice were handled 2 min per day for 5 d and habituated to the experimental apparatus for 5 min per day for 4 d in the absence of objects. The experimental apparatus was a white rectangular open field, in which during the training phase two 100 mL beakers were presented to the animals for 10 min (Stefanko et al. 2009) (for object placement see the schematic in Fig. 4C). After 24 h, retention was tested for 5 min, during which a moved and an unmoved object were presented. Training and testing trials were videotaped and analyzed by individuals, blind to the treatment condition of subjects. Videos were analyzed and total exploration time as well as the discrimination index ([time spent exploring novel location – time spent exploring familiar location]/total time exploring both objects) calculated as described in Stefanko et al. (2009) and McQuown et al. (2011).

Cannulation and drug delivery

Cannulae (Plastics One Inc.) were placed for the dorsal hippocampus (AP −1.7 mm; ML ±1.2 mm; DV −1.5 mm) as described in Haettig et al. (2011). The injection cannulae used extended an additional 0.5 mm below the guide cannulae to a total depth of 2.0 mm. Bilateral injections in the dorsal hippocampus were performed 30 min prior to training (0.5 µL/side at 15 µL/h). Saline was used as vehicle and allatostatin was dissolved in saline to a concentration of 1 µM. We did not observe any signs of seizure or abnormal behavior in the infused mice, including the Dlx5/6-Cre:AlstR mice. Cannula placement was histologically verified after behavioral experiments. For some animals (N = 7), the AL infusion sites were also confirmed by the dye injection with 0.5 µL of 0.5 mM Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated biocytin (Fig. 4A,B) prior to sacrificing the animal. Following transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, the brains were sectioned (50-μm thickness) and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich). The infusion sites were directly visualized by detection of the Alexa Fluor 594 fluorescent labeling in the tissue.

Data analysis

Statistical tests were performed using SigmaStat 3.5 or MATLAB. The data were checked for normality distribution and equal variance. If the criteria where met, a t-test was performed to compare two groups; when the criteria were not met, a Mann–Whitney U-test was used. Alpha levels of P ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants DA023700 and NS078434 to X.X. and MH081004 to M.A.W. We thank Taruna Ikrar and Yulin Shi for their assistance with slice imaging experiments, and Shikha Seth for her assistance with surgical procedures.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

References

- Abel T, Lattal KM 2001. Molecular mechanisms of memory acquisition, consolidation and retrieval. Curr Opin Neurobiol 11: 180–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GM, Rogan SC, Abbas AI, Armbruster BN, Pei Y, Allen JA, Nonneman RJ, Hartmann J, Moy SS, Nicolelis MA, et al. 2009. Remote control of neuronal activity in transgenic mice expressing evolved G protein-coupled receptors. Neuron 63: 27–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL 2007. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 5163–5168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderas I, Rodriguez-Ortiz CJ, Salgado-Tonda P, Chavez-Hurtado J, McGaugh JL, Bermudez-Rattoni F 2008. The consolidation of object and context recognition memory involve different regions of the temporal lobe. Learn Mem 15: 618–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett RM, Malvaez M, Kramar E, Matheos DP, Arrizon A, Cabrera SM, Lynch G, Greene RW, Wood MA 2011. Hippocampal focal knockout of CBP affects specific histone modifications, long-term potentiation, and long-term memory. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 1545–1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Vida I, Jonas P 2007. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgul N, Weise C, Kreienkamp HJ, Richter D 1999. Reverse physiology in Drosophila: Identification of a novel allatostatin-like neuropeptide and its cognate receptor structurally related to the mammalian somatostatin/galanin/opioid receptor family. EMBO J 18: 5892–5900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G, Kaila K, Raichle M 2007. Inhibition and brain work. Neuron 56: 771–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow BY, Han X, Dobry AS, Qian X, Chuong AS, Li M, Henninger MA, Belfort GM, Lin Y, Monahan PE, et al. 2010. High-performance genetically targetable optical neural silencing by light-driven proton pumps. Nature 463: 98–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RE, Squire LR 2010. An animal model of recognition memory and medial temporal lobe amnesia: History and current issues. Neuropsychologia 48: 2234–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin BR, Hsiao EC, Claeysen S, Dumuis A, Srinivasan S, Forsayeth JR, Guettier JM, Chang WC, Pei Y, McCarthy KD, et al. 2008. Engineering GPCR signaling pathways with RASSLs. Nat Methods 5: 673–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossart R, Bernard C, Ben-Ari Y 2005. Multiple facets of GABAergic neurons and synapses: Multiple fates of GABA signalling in epilepsies. Trends Neurosci 28: 108–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward P, Wada HG, Falk MS, Chan SD, Meng F, Akil H, Conklin BR 1998. Controlling signaling with a specifically designed Gi-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 352–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Costa RM, Murphy GG, Elgersma Y, Zhu Y, Gutmann DH, Parada LF, Mody I, Silva AJ 2008. Neurofibromin regulation of ERK signaling modulates GABA release and learning. Cell 135: 549–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascal N 1997. Signalling via the G protein-activated K+ channels. Cell Signal 9: 551–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diester I, Kaufman MT, Mogri M, Pashaie R, Goo W, Yizhar O, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K, Shenoy KV 2011. An optogenetic toolbox designed for primates. Nat Neurosci 14: 387–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Eskenazi D, Ishikawa M, Wanat MJ, Phillips PE, Dong Y, Roth BL, Neumaier JF 2011. Transient neuronal inhibition reveals opposing roles of indirect and direct pathways in sensitization. Nat Neurosci 14: 22–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Katona I 2007. Perisomatic inhibition. Neuron 56: 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JA, Talley T, Qiu M, Puelles L, Rubenstein JL, Jones KR 2002. Cortical excitatory neurons and glia, but not GABAergic neurons, are produced in the Emx1-expressing lineage. J Neurosci 22: 6309–6314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosgnach S, Lanuza GM, Butt SJ, Saueressig H, Zhang Y, Velasquez T, Riethmacher D, Callaway EM, Kiehn O, Goulding M 2006. V1 spinal neurons regulate the speed of vertebrate locomotor outputs. Nature 440: 215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Hong S, Jin XL, Chen RS, Avasthi PP, Tu YT, Ivanco TL, Li Y 2000. Specificity and efficiency of Cre-mediated recombination in Emx1-Cre knock-in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 273: 661–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haettig J, Stefanko DP, Multani ML, Figueroa DX, McQuown SC, Wood MA 2011. HDAC inhibition modulates hippocampus-dependent long-term memory for object location in a CBP-dependent manner. Learn Mem 18: 71–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Boyden ES 2007. Multiple-color optical activation, silencing, and desynchronization of neural activity, with single-spike temporal resolution. PLoS One 2: e299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikrar T, Shi Y, Velasquez T, Goulding M, Xu X 2012. Cell-type specific regulation of cortical excitability through the allatostatin receptor system. Front Neural Circuits 6: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karschin C, DiBmann E, Stuehmer W, Karschin A 1996. IRK(l-3) and GIRK(l-4) inwardly rectifying K+ channel mRNAs are differentially expressed in the adult rat brain. J Neurosci 16: 3559–3570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Somogyi P 2008. Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: The unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science 321: 53–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Magill PJ, Marton LF, Roberts JD, Cobden PM, Buzsaki G, Somogyi P 2003. Brain-state- and cell-type-specific firing of hippocampal interneurons in vivo. Nature 421: 844–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman SJ, Huang ZJ 2008. High-resolution labeling and functional manipulation of specific neuron types in mouse brain by Cre-activated viral gene expression. PLoS One 3: e2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner HA, Lein ES, Callaway EM 2002. A genetic method for selective and quickly reversible silencing of mammalian neurons. J Neurosci 22: 5287–5290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz C, Williamson M, Grimmelikhuijzen CJ 2000. Molecular cloning and genomic organization of a second probable allatostatin receptor from Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 273: 571–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, et al. 2010. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci 13: 133–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark MD, Herlitze S 2000. G-protein mediated gating of inward-rectifier K+ channels. Eur J Biochem 267: 5830–5836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh TJ, Blum KI, Tsien JZ, Tonegawa S, Wilson MA 1996. Impaired hippocampal representation of space in CA1-specific NMDAR1 knockout mice. Cell 87: 1339–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuown SC, Barrett RM, Matheos DP, Post RJ, Rogge GA, Alenghat T, Mullican SE, Jones S, Rusche JR, Lazar MA, et al. 2011. HDAC3 is a critical negative regulator of long-term memory formation. J Neurosci 31: 764–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monory K, Massa F, Egertova M, Eder M, Blaudzun H, Westenbroek R, Kelsch W, Jacob W, Marsch R, Ekker M, et al. 2006. The endocannabinoid system controls key epileptogenic circuits in the hippocampus. Neuron 51: 455–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AJ, Sauer J-F, Riedel G, McClure C, Ansel L, Cheyne L, Bartos M, Wisden W, Wulff P 2011. Parvalbumin-positive CA1 interneurons are required for spatial working but not for reference memory. Nat Neurosci 14: 297–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashiba T, Young JZ, McHugh TJ, Buhl DL, Tonegawa S 2008. Transgenic inhibition of synaptic transmission reveals role of CA3 output in hippocampal learning. Science 319: 1260–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panganiban G, Rubenstein JL 2002. Developmental functions of the distal-less/Dlx homeobox genes. Development 129: 4371–4386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran I, Laplante I, Lacaille JC 2012. CREB-dependent transcriptional control and quantal changes in persistent long-term potentiation in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci 32: 6335–6350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern CH, Coward P, Degtyarev MY, Lee EK, Kwa AT, Hennighausen L, Bujard H, Fishman GI, Conklin BR 1999. Conditional expression and signaling of a specifically designed Gi-coupled receptor in transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol 17: 165–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, Hernandez A, Cabrera SM, Hagewoud R, Malvaez M, Stefanko DP, Haettig J, Wood MA 2010. Membrane-associated glucocorticoid activity is necessary for modulation of long-term memory via chromatin modification. J Neurosci 30: 5037–5046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer S, Zemelman BV, Losonczy A, Kim J, Chance F, Magee JC, Buzsaki G 2012. Control of timing, rate and bursts of hippocampal place cells by dendritic and somatic inhibition. Nat Neurosci 15: 769–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruediger S, Vittori C, Bednarek E, Genoud C, Strata P, Sacchetti B, Caroni P 2011. Learning-related feedforward inhibitory connectivity growth required for memory precision. Nature 473: 514–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhakumar V, Soltesz I 2004. Plasticity of interneuronal species diversity and parameter variance in neurological diseases. Trends Neurosci 27: 504–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanko DP, Barrett RM, Ly AR, Reolon GK, Wood MA 2009. Modulation of long-term memory for object recognition via HDAC inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 9447–9452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EM, Yamaguchi Y, Horwitz GD, Gosgnach S, Lein ES, Goulding M, Albright TD, Callaway EM 2006. Selective and quickly reversible inactivation of mammalian neurons in vivo using the Drosophila allatostatin receptor. Neuron 51: 157–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W, Janczewski WA, Yang P, Shao XM, Callaway EM, Feldman JL 2008. Silencing preBotzinger complex somatostatin-expressing neurons induces persistent apnea in awake rat. Nat Neurosci 11: 538–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi H, He M, Wu P, Kim S, Paik R, Sugino K, Kvitsani D, Fu Y, Lu J, Lin Y, et al. 2011. A resource of Cre driver lines for genetic targeting of GABAergic neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron 71: 995–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien JZ, Huerta PT, Tonegawa S 1996. The essential role of hippocampal CA1 NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in spatial memory. Cell 87: 1327–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsey CG, Hawk JD, Lattal KM, Stein JM, Fabian SA, Attner MA, Cabrera SM, McDonough CB, Brindle PK, Abel T, et al. 2007. Histone deacetylase inhibitors enhance memory and synaptic plasticity via CREB:CBP-dependent transcriptional activation. J Neurosci 27: 6128–6140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr M, Hostick U, Kyweriga M, Tan A, Weible AP, Wu H, Wu W, Callaway EM, Kentros C 2009. Transgenic silencing of neurons in the mammalian brain by expression of the allatostatin receptor (AlstR). J Neurophysiol 102: 2554–2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters BD, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ 2008. Object recognition memory: Neurobiological mechanisms of encoding, consolidation and retrieval. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32: 1055–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X 2011. High precision and fast functional mapping of brain circuitry through laser scanning photostimulation and fast dye imaging. In Laser scanning, theory and applications (ed. Wang C-C), pp. 113–132 InTech, Rijeka, Croatia [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Olivas ND, Levi R, Ikrar T, Nenadic Z 2010. High precision and fast functional mapping of cortical circuitry through a combination of voltage sensitive dye imaging and laser scanning photostimulation. J Neurophysiol 103: 2301–2312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Won J, Karlsson MG, Zhou M, Rogerson T, Balaji J, Neve R, Poirazi P, Silva AJ 2009. CREB regulates excitability and the allocation of memory to subsets of neurons in the amygdala. Nat Neurosci 12: 1438–1443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]