Abstract

Honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) are eusocial insects and well known for their complex division of labor and associative learning capability1, 2. The worker bees spend the first half of their life inside the dark hive, where they are nursing the larvae or building the regular hexagonal combs for food (e.g. pollen or nectar) and brood3. The antennae are extraordinary multisensory feelers and play a pivotal role in various tactile mediated tasks4, including hive building5 and pattern recognition6. Later in life, each single bee leaves the hive to forage for food. Then a bee has to learn to discriminate profitable food sources, memorize their location, and communicate it to its nest mates7. Bees use different floral signals like colors or odors7, 8, but also tactile cues from the petal surface9 to form multisensory memories of the food source. Under laboratory conditions, bees can be trained in an appetitive learning paradigm to discriminate tactile object features, such as edges or grooves with their antennae10, 11, 12, 13. This learning paradigm is closely related to the classical olfactory conditioning of the proboscis extension response (PER) in harnessed bees14. The advantage of the tactile learning paradigm in the laboratory is the possibility of combining behavioral experiments on learning with various physiological measurements, including the analysis of the antennal movement pattern.

Keywords: Neuroscience, Issue 70, Physiology, Anatomy, Entomology, Behavior, Sensilla, Bees, behavioral sciences, Sense Organs, Honey bee, Apis mellifera L., Insect antenna, Tactile sampling, conditioning, Proboscis extension response, Motion capture

Protocol

1. Preparing the Bees

Nectar or Pollen foragers are caught in the field either from a sucrose feeder or directly from the hive entrance while returning from a foraging trip. Each single bee is captured into a glass vial that is closed with a foam plug and taken immediately into the laboratory for further handling.

In the laboratory, the captured bees are briefly cooled in the refrigerator at 4 °C until they show first signs of immobility.

Each single immobilized bee is mounted in a small metal tube with adhesive tape between head and thorax and over the abdomen. Care should be taken that the proboscis and antennae are freely movable.

Paint the compound eyes and ocelli of the fixed bee with white paint (e.g. solvent-free Tipp-Ex) to occlude vision.

Add a small drop of melted wax behind the head of the bee to fix it to the tape between head and thorax to prevent head movements during recordings.

Mark each single bee with a number on the tape for better identification and place the tube with the fixed bee into a humid atmosphere to prevent dehydration.

Feed each single bee for 5 sec with droplets of a 30% sucrose solution presented with a syringe and let all bees recover for 30 min before starting with the tactile conditioning protocol.

2. Tactile Conditioning

Before conditioning, each single bee has to be tested for the proboscis extension response (PER) to a 30% sucrose stimulus applied to the antennae. Thereby the tip of the proboscis has to cross a virtual line between the opened mandibles. Discard all bees that don't respond with a PER to the sucrose stimulus.

For tactile conditioning use a brass cube (e.g. 3 x 5 mm) with a smooth or an engraved pattern, e.g., horizontal or vertical grooves forming a grating with 150 μm wave length, as the conditioned stimulus (CS). For the unconditioned stimulus (US) use a 30% sucrose solution (household sugar, diluted in water).

The brass cube (CS) is placed into a holder on a micromanipulator (e.g., Märzhäuser MM33) to ensure exact positioning during the conditioning procedure. The US is presented to the bee with a syringe filled with a 30% sucrose solution.

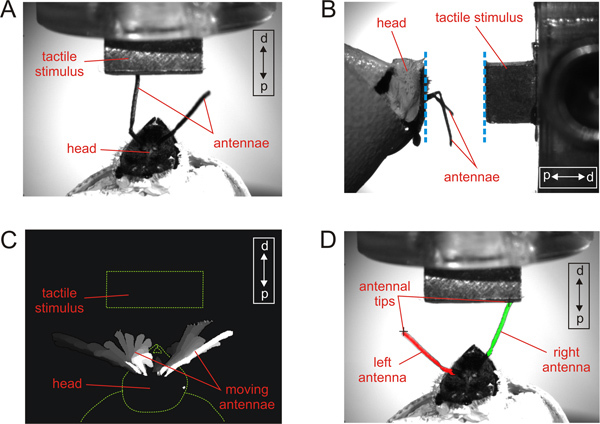

The conditioning procedure consists of five pairings of the tactile stimulus (CS) and sucrose solution (US) with an inter-trial interval (ITI) of 5 min. Place a single bee in front of the micromanipulator with the mounted tactile stimulus (CS). Position the CS slowly, such that the surface of the tactile stimulus is parallel to the head of the bee (Figure 1 A and B). The distance between the animal and the tactile object should be in the range of the antennal working radius of the tested bee, i.e. the bee should be able to scan the tactile stimulus in a comfortable position with both antennae. In the example shown in Figure 1, the distance was 3 mm. Let the bee scan the tactile stimulus (CS) for 5 sec. After the first 3 sec, present a droplet of the 30% sucrose (US) solution with a syringe under the proboscis. Use the tip of the syringe to gently raise the proboscis. Sucrose stimulation under the proboscis will elicit the unconditioned PER15. Allow the bee to lick the sucrose reward. Use a stopwatch with an alarm signal to maintain the exact time intervals during conditioning.

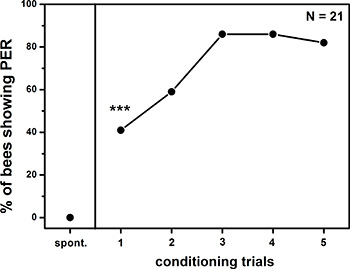

The conditioned PER is used as a measure for the learning success of a bee. After the first rewarded pairings, bees start to respond to CS presentation by extension of their proboscis, indicating that they expect the forthcoming reward. A fully extended proboscis observed anytime during the 3 sec time window of tactile stimulus presentation and before sucrose presentation is scored as a positive response. No response is counted negative. The occurrence of the PER has to be noted by the experimenter. The percentage of bees showing the PER during CS presentation is plotted for each trial.

3. Kinematic Recordings

Antennal movements of a single harnessed bee are recorded with a digital video camera with a suitable macro lens (e.g. Basler A602f-2 equipped with TechSpec VZM 200, operated at 50 fps via a fire wire connection). The camera is positioned above the animal in a top-down view (Figure 1 A). In Figure 1, the spatial resolution of the recordings is 0.02 mm/pixel.

Calibrate the camera by recording single pictures of a 10 x 10 mm checkerboard with an edge length of 1 mm from different orientations under the camera objective. The calibration can be done with the camera calibration tool box Matlab16.

Place a single fixed bee below the camera lens. Present the tactile stimulus, fixed to a micromanipulator, to the animal. Proceed in the same way as described for tactile conditioning, and record the antennal movement while the bee is scanning the object. It is important that the full antennal working range and the tactile stimulus are visible. The choices of stimulus patterns tested and trial numbers depend on the experimental design.

4. Data Analysis

The computation of the image background is done in Matlab. First, the median greyscale value over time has to be calculated for each pixel. Static objects, like the fixed head of the bee and the tactile stimulus, will constitute the image background. Moving objects, like the two antennae, will not be part of the background.

Each frame of the recorded video has to be loaded sequentially, and the difference between the current frame and the image background has to be computed. The result of this subtraction emphasizes those parts of the image that are moving from frame to frame. Ideally, the antennae of the bee are the only areas of non-zero values (Figure 1C).

For further processing, the two largest areas with non-zero pixel values are assumed to be the antennae. For both antennae a binary mask is to be generated containing for each pixel a value 1, if the pixel belongs to the antenna and value 0 otherwise. This mask serves as a basis for localizing the antennal tips later. To gain a preliminary mask for the entire image the grey-value of each pixel of the difference image is compared to a pre-defined threshold. Since we take care of noise later this threshold is chosen to be quite low. The preliminary mask then still carries two kinds of errors: Firstly, due to image noise small regions are still part of the mask. Secondly, areas that belong to the antenna might not necessarily be fully connected. The latter mostly occurs if the background has approximately the same luminescence as the antenna. To eliminate these artifacts, standard image processing morphological operation are applied, i.e. a combination of image erosion and dilatation, relying upon the standard Matlab functions imerode and imdilate respectively (see17 pp. 158-205 for further explanation). After the denoising process the antennae hypotheses are still contained within the same mask. Hence, as a next step the binary mask is clustered for disjoint areas using the standard Matlab function bwlabel (see17 pp. 40-48 for further details on the image segmentation algorithm).

The number of pixels per cluster is counted and the two largest clusters are selected. The center of gravity is calculated to distinguish between the left and right antenna (Figure 1D).

The antennal tip for each antenna can be defined as the pixel in a cluster with the highest value in the proximal-to-distal direction (see Figure 1D).

Representative Results

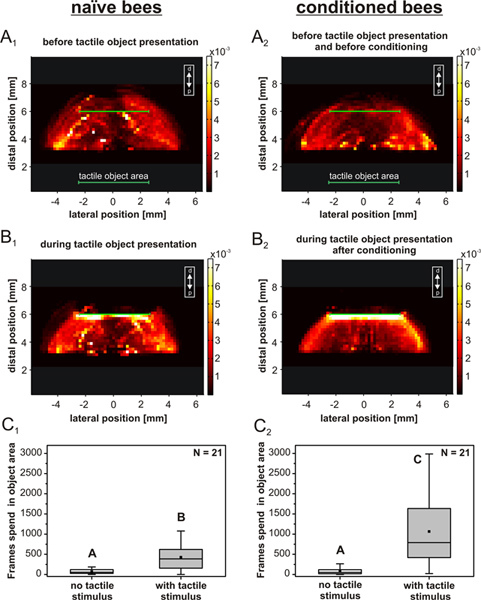

In the following experiment we studied how tactile learning affects antennal sampling behavior in honey bees. For this, we monitored the movement of the antennal tip in naïve and conditioned bees before and during presentation of a tactile stimulus.

First, the spontaneous antennal movement of a group of pollen foragers (N = 42) was recorded for 1 min. One half of the bees (N = 21) was then conditioned by pairing five times a tactile stimulus with a 30% sucrose reward. This was the conditioned group. The tactile stimulus was the 30 x 50 mm surface of a brass cube with an engraved horizontal grating ( λ= 150 μm). The other half of the bees (N = 21) was not conditioned and used as a naïve group. Figure 2 shows the mean learning curve of the conditioned group of bees. The percentage of conditioned PER after the first reward is significantly different from the spontaneous behavior (Figure 2, Fisher exact probability test, p < 0.001). The learning curve shows saturation after the 3rd reward.

Afterwards the movement of the antennal tip in both the conditioned and the naïve group was recorded again for 1 min in presence of the tactile stimulus. Figure 3 A1 - B2 shows the distribution of antennal tip locations in both groups, before and during presentation of the tactile object. Both, the naïve and the conditioned group changed their antennal movement pattern in presence of a tactile stimulus compared to the spontaneous behavior. The likelihood of the antennal tip to search and/or sample the area of the stimulus is significantly increased if the stimulus was present, showing that tactile sampling involves a marked change in the antennal movement pattern compared to spontaneous antennal movement. This is true for both groups of bees (Figure 3 C1 and C2, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 0.001 in both cases). Bees from the conditioned group spent significantly more time with their antennal tip in the area of the stimulus than the naïve bees (Figure 3 C1 and C2, Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.05; there was no significant difference between the two reference periods A in Figure 3C). Thus, tactile conditioning leads to an increase of active antennal movement near the object and tactile sampling of the object surface as previously shown in Erber (2012)18. Compared to the naïve group, the spatial distribution during stimulus presentation was much smoother after conditioning (Compare Figure 3 B1 and B2).

In summary, the results from this experiment show that honey bees can be trained very effectively to respond to a tactile stimulus, and that tactile learning is accompanied by increased active searching and sampling behavior.

Figure 1. Video recording and antennal tracking procedure. A: Top-down view of a fixed bee and the tactile stimulus. The tactile stimulus is positioned in front of the head of the fixed bee with occluded eyes. It is located within the antennal working- range. d and p indicate distal and proximal locations relative to the animal. B: Side view of the same bee and the tactile stimulus. The surface of the tactile stimulus and the head of the bee (blue dotted lines) are parallel to each other. C: Distinguishing moving pixels from static pixels in a video sequence. Subtracting each image from a background model allows identification of the moving parts, i.e., the antennae. The fixed head of the bee and the tactile stimulus (indicated here as red dotted lines) are static and not visible after the subtraction. D: Defining left and right and the antennal tip. The two largest pixel clusters after subtraction are identified as antennae. Calculation of the center of gravity allows distinguishing between the left (red) and the right (green) antenna. The antennal tip for each antenna (black cross) can be defined as the pixel in a cluster with the largest value in the distal direction.

Figure 1. Video recording and antennal tracking procedure. A: Top-down view of a fixed bee and the tactile stimulus. The tactile stimulus is positioned in front of the head of the fixed bee with occluded eyes. It is located within the antennal working- range. d and p indicate distal and proximal locations relative to the animal. B: Side view of the same bee and the tactile stimulus. The surface of the tactile stimulus and the head of the bee (blue dotted lines) are parallel to each other. C: Distinguishing moving pixels from static pixels in a video sequence. Subtracting each image from a background model allows identification of the moving parts, i.e., the antennae. The fixed head of the bee and the tactile stimulus (indicated here as red dotted lines) are static and not visible after the subtraction. D: Defining left and right and the antennal tip. The two largest pixel clusters after subtraction are identified as antennae. Calculation of the center of gravity allows distinguishing between the left (red) and the right (green) antenna. The antennal tip for each antenna (black cross) can be defined as the pixel in a cluster with the largest value in the distal direction.

Figure 2. Learning curve of tactile PER conditioning. Pollen foragers were trained using five pairings of the CS (tactile stimulus) and US (sucrose solution) with an inter-trial interval of 5 min. The percentage of positive responses of 21 animals is plotted for the spontaneous behavior (spont) and during presentation of the CS after each conditioning trial. The percentage of PER observed after the first and all following rewards is significantly different from the spontaneous behavior (Fisher exact probability test, p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Learning curve of tactile PER conditioning. Pollen foragers were trained using five pairings of the CS (tactile stimulus) and US (sucrose solution) with an inter-trial interval of 5 min. The percentage of positive responses of 21 animals is plotted for the spontaneous behavior (spont) and during presentation of the CS after each conditioning trial. The percentage of PER observed after the first and all following rewards is significantly different from the spontaneous behavior (Fisher exact probability test, p < 0.001).

Figure 3. Normalized average distributions of the antennal tip location during a period of 1 min. The antennal tip distribution of each bee was normalized to the total number of data points per animal. The panels show results from naïve (left, N = 21) and conditioned bees (right, N = 21) before (A) and during stimulus presentation (B). A1 and A2: Spontaneous antennal movement before stimulus presentation. The abscissa shows the lateral position of the antennal tip relative to the center of the head (compare with Figure 1C and D). The ordinate shows the distal position of the antennal tip. The color scale indicates the percentage of time that the antennal tip spent at any given location. The recording period of 1 min was equivalent to 3,000 video frames. B1 and B2: Same as in A1,2, but during stimulus presentation. C1 and C2: Average number of frames in which the antennal tip was located inside the object area, i.e., ± 3 bins distal or proximal relative to the stimulus surface. C1: naïve group; C2: conditioned group. The box-whisker plots show the median, mean, quartiles, and 5-95% percentile ranges of number of frames per minute. In both groups of bees, there is a significant difference between 'no stimulus' (A) and 'with stimulus' (B, C; Wilcoxon signed-rank test, C1: P = 5.39*10-4; C2: P = 5.96*10-5). The average number of frames during tactile stimulus presentation is significantly larger in conditioned bees than in naïve bees (Mann-Whitney U test, C1 - C2: P = 0.007). Click here to view larger figure.

Figure 3. Normalized average distributions of the antennal tip location during a period of 1 min. The antennal tip distribution of each bee was normalized to the total number of data points per animal. The panels show results from naïve (left, N = 21) and conditioned bees (right, N = 21) before (A) and during stimulus presentation (B). A1 and A2: Spontaneous antennal movement before stimulus presentation. The abscissa shows the lateral position of the antennal tip relative to the center of the head (compare with Figure 1C and D). The ordinate shows the distal position of the antennal tip. The color scale indicates the percentage of time that the antennal tip spent at any given location. The recording period of 1 min was equivalent to 3,000 video frames. B1 and B2: Same as in A1,2, but during stimulus presentation. C1 and C2: Average number of frames in which the antennal tip was located inside the object area, i.e., ± 3 bins distal or proximal relative to the stimulus surface. C1: naïve group; C2: conditioned group. The box-whisker plots show the median, mean, quartiles, and 5-95% percentile ranges of number of frames per minute. In both groups of bees, there is a significant difference between 'no stimulus' (A) and 'with stimulus' (B, C; Wilcoxon signed-rank test, C1: P = 5.39*10-4; C2: P = 5.96*10-5). The average number of frames during tactile stimulus presentation is significantly larger in conditioned bees than in naïve bees (Mann-Whitney U test, C1 - C2: P = 0.007). Click here to view larger figure.

Discussion

Preparation of bees: Collecting and fixing the bees should be done quickly, in order to keep the stress level of the animal low. Stress has an effect on the PER-responsiveness and, therefore, could have an indirect effect on the learning performance in bees19, 20. The stress level can be decreased by placing the glass vials with the bees directly on ice immediately after collection to immobilize them quickly. It has to be taken into account that bees need more time to recover the longer the anesthesia period is before.

Vision has a negative effect on tactile learning in bees18. Therefore it is important to occlude vision by painting the eyes of the animal. In order to increase the visual contrast of the video recordings, it is recommended to use white paint (e.g., Tipp-Ex). Care should be taken not to get the antennae in contact with the paint.

Learning performance: Former studies in the laboratory and field showed that sucrose sensitivity in honey bee foragers affect their associative learning ability21, 22. High sucrose sensitivity is positively correlated with better tactile acquisition and discrimination performances. Pollen foragers of a honey bee colony are on average more responsive to sucrose than nectar foragers in most weeks of a foraging season23. They can be easily identified by the pollen loads on their hind legs and caught at the hive entrance. Nectar foragers with high sucrose sensitivity can be caught at the end of a foraging season, between September and October. They can be selected on artificial feeders filled with low-concentrated sugar water placed approximately 20 m away from the hive23.

The learning performance and memory formation depends strongly on the satiation status of a bee during conditioning25. A longer starvation period before conditioning, e.g. overnight, can improve the associative learning behavior and increase the motivation level of an animal.

Tactile conditioning: The PER is used as the unconditioned response in an appetitive learning protocol14. Therefore, it is crucial that all tested bees are showing a fully extended PER to the unconditioned stimulus (sugar stimulus) before conditioning. Bees that do not respond to the sugar stimulus should be discarded as well as bees that respond with a PER during antennal contact with the tactile stimulus before conditioning. Otherwise, the extremely low or extremely high responsiveness of these animals will confound the learning curve.

The tactile stimulus used in this protocol (brass cube with horizontal gratings) was randomly chosen. Honey bees can be also conditioned on different tactile stimuli with various shapes and textures (see10).

The tactile stimulus must be cleaned after each conditioning trial and after contact with the tongue of an animal by immersing it in 70% ethanol and drying it with a cellulose cloth.

To compare acquisition in different groups of bees (e.g. Pollen- versus Nectar foragers), an acquisition score can be calculated21. This score is the total number of conditioned responses to the CS and it has a range between 0 (no conditioned PER) and 5 (conditioned PER after each conditioning trial).

Video analysis: Different video analyses methods were used in the past to quantify changes in the antennal movement behavior in honey bees26, 27. Our method has the advantage of analyzing the antennal movements without requiring reflective markers on the antennae and benefits from the variety of image processing tools in Matlab. As an example, one can also analyze the timing of antennal contacts towards an object, determine the speed of antennal movement, calculate the angular positions of the antennae in reference to the body axes or discriminate between left and right antennal movement.

A PER that occurs during recording of antennal response to the object in conditioned bees could interfere later with the automatic detection of the antennae. In this case it is necessary to edit the movie, e.g. in VirtualDub, and to mask the object that interferes with the detection process, e.g. by covering the section where the proboscis appears with a grey layer of the same shape.

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest declared.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joachim Erber for introducing us to the tactile learning paradigm in honey bees. This work was supported by the Cluster of Excellence 277 CITEC, funded in the framework of the German Excellence Initiative.

References

- Page RE, Scheiner R, Erber J, Amdam GV. The development and evolution of division of labor and foraging specialization in a social insect (Apis mellifera L.) Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2006;74:253–286. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)74008-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel R, Müller U. Learning and memory in honeybees: From behavior to neural substrates. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1996;19:379–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.002115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley TD. The wisdom of the hive. Cambridge Mass, London: Harvard University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Staudacher E, Gebhardt MJ, Dürr V. Antennal movements and mechanoreception: neurobiology of active tactile sensors. Adv. Insect Physiol. 2005;32:49–205. [Google Scholar]

- Martin H, Lindauer M. Sinnesphysiologische Leistungen beim Wabenbau der Honigbiene. Z. Vergl. Physiol. 1966;53:372–404. [Google Scholar]

- Kevan PG. Texture sensitivity in the life of honeybees. In: Menzel R, Mercer A, editors. Neurobiology and behavior of honeybees. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag; 1987. pp. 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- von Frisch K. Tanzsprache und Orientierung der Bienen. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Waser NM. Flower constancy: definition, cause, and ceasurement. Am. Nat. 1986;127:593–603. [Google Scholar]

- Kevan PG, Lane MA. Flower petal microtexture is a tactile cue for bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:4750–4752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber J, Kierzek S, Sander E, Grandy K. Tactile learning in the honeybee. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 1998;183:737–744. [Google Scholar]

- Kisch J, Erber J. Operant conditioning of antennal movements in the honey bee. Behav. Brain. Res. 1999;99:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner R, Erber J, Page RE. Tactile learning and the individual evaluation of the reward in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) J. Comp. Physiol. A. 1999;185:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s003590050360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber J, Scheiner R. Honeybee learning. In: Adelman G, Smith B, editors. Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bitterman ME, Menzel R, Fietz A, Schäfer S. Classical conditioning of proboscis extension in honeybees (Apis mellifera) J. Comp. Psychol. 1983;97:107–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacher M, Gauthier M. Involvement of NO-synthase and nicotinic receptors in learning in the honey bee. Physiol. Behav. 2008;95:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camera Calibration Toolbox for Matlab [Internet] 2004. [Oct. 2011]. Available from: http://www.vision.caltech.edu/bouguetj/calib_doc.

- Haralick RM, Shapiro LG. Computer and Robot Vision. I. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Erber J. Tactile antennal learning in the honey bee. In: Galizia CG, et al., editors. Honeybee Neurobiology and Behavior. Springer Verlag; 2012. pp. 439–455. [Google Scholar]

- Pankiw T, Page RE. Effect of pheromones, hormones, and handling on sucrose response thresholds of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) J. Comp. Physiol. A. 2003;189:675–684. doi: 10.1007/s00359-003-0442-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JW, Woodring J. Effects of stress, age, season and source colony on levels of octopamine, dopamine and serotonine in the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) brain. J. Insect. Physiol. 1992;38:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner R, Kuritz-Kaiser A, Menzel R, Erber J. Sensory responsiveness and the effects of equal subjective rewards on tactile learning and memory of honeybees. Learn. Mem. 2005;12:626–635. doi: 10.1101/lm.98105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujagic S, Sarkander J, Erber B, Erber J. Sucrose acceptance and different forms of associative learning of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) in the field and laboratory. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2010;4:46. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2010.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner R, Barnert M, Erber J. Variation in water and sucrose responsiveness during the foraging season affects proboscis extension learning in honey bees. Apidologie. 2003;34:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mujagic S, Erber J. Sucrose acceptance, discrimination and proboscis responses of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) in the field and the laboratory. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 2009;195:325–339. doi: 10.1007/s00359-008-0409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich A, Thomas U, Müller U. Learning at different satiation levels reveals parallel functions for the cAMP-protein kinase A cascade in formation of long-term memory. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4460–4468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0669-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber J, Pribbenow B, Grandy K, Kierzek S. Tactile motor learning in the antennal system of the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) J. Comp. Physiol. A. 1997;181:355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Lambin M, Déglise P, Gauthier M. Antennal movements as indicators of odor detection by worker honeybees. Apidologie. 2005;36:119–126. [Google Scholar]