Abstract

Objective. To investigate students' use and views on social networking sites and assess differences in attitudes between genders and years in the program.

Methods. All pharmacy undergraduate students were invited via e-mail to complete an electronic questionnaire consisting of 21 questions relating to social networking.

Results. Most (91.8%) of the 377 respondents reported using social networking Web sites, with 98.6% using Facebook and 33.7% using Twitter. Female students were more likely than male students to agree that they had been made sufficiently aware of the professional behavior expected of them when using social networking sites (76.6% vs 58.1% p=0.002) and to agree that students should have the same professional standards whether on placement or using social networking sites (76.3% vs 61.6%; p<0.001).

Conclusions. A high level of social networking use and potentially inappropriate attitudes towards professionalism were found among pharmacy students. Further training may be useful to ensure pharmacy students are aware of how to apply codes of conduct when using social networking sites.

Keywords: students, social networking, media, professionalism

INTRODUCTION

The use of social media has greatly increased over the past 5 years, with global user numbers for the social networking market leader, Facebook, increasing from 58 million1 in December 2007 to 955 million2 in June 2012. The growth of social media is seen by some as the personalization of the World Wide Web, allowing users to connect with one another and share information such as comments, photographs, and videos. There are numerous types of social media and networking sites, including those intended primarily for promoting social connections and interactions (eg, Facebook, www.Facebook.com); publishing short messages (tweets) (eg, Twitter, www.twitter.com); posting videos (eg, YouTube, www.youtube.com); sending instant messages (eg, Windows Live Messenger, www.microsoft.com); and developing professional networks (eg, LinkedIn, www.linkedin.com).

Although extremely popular,2 there is controversy about students’ and professionals’ use of social networking sites, particularly in relation to privacy, safety, and inappropriate behavior. Material published online may remain linked to an individual for many years. Thus, potentially inappropriate attitudes and behaviors that users share online with friends through comments, photographs, and other media also may be viewed by parents, academic staff, and current or potential employers. These possibilities highlight the importance of the sites’ privacy features, which enable content to be shared with a limited numbers of users. However, even with privacy features enabled, the user is reliant on those who can access their site’s content not sharing it with others in a public arena. The failure of users to adequately understand the risks associated with publishing content on social networking sites has led to a number of high-profile disciplinary and criminal cases, including those among healthcare professionals and students.3,4 Indeed, staff members in some universities have been reported to actively seek out online offenders.5

The ability to publish comments to a wide audience has led to flippant statements (eg, making insinuations regarding violent behavior,6 making racial slurs7) being treated with more seriousness than the user intended. While illegal and offensive behavior displayed on social networking sites has direct consequences for the individuals concerned, there are higher expectations and additional responsibilities placed on those who work as, or are training to become, health care professionals. Numerous incidents in which UK health professionals have posted inappropriate material on social networking sites have been reported in the National Health Service in England, including doctors and nurses engaging in unprofessional behavior while on duty, making comments about patients, posting photos taken while on duty, and breaching patient confidentiality.8,9 Regulators have endeavored to clarify their position with respect to posting on social networking sites in the context of the professional standards that they already have in place. In the United Kingdom, the Nursing and Midwifery Council has published guidance on how to apply the principles of their code of conduct to the use of such sites.10 The General Medical Council, the body responsible for the regulation of doctors within the United Kingdom, plans to draft specific guidance on the use of social media, while the professional body for doctors, the British Medical Association, published guidance for doctors and medical students in July 2011.11 The regulators of pharmacy in the United Kingdom, the General Pharmaceutical Council and Pharmaceutical Society of Northern Ireland (PSNI), have yet to provide any specific guidance on the use of social media, although the issue is raised in the context of professional boundaries and learning from disciplinary cases. Similarly, in the United States, the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) Code of Ethics for Pharmacists and the APhA’s Academy of Student Pharmacists/American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Pledge of Professionalism provide general principles on appropriate pharmacist and pharmacy student behavior, but do not specifically apply them to the digital realm.12,13

There are ethical and professional aspects to the use of social networking sites that relate directly to existing standards and codes of conduct.14,15 The PSNI’s Code of Ethics states that ethical requirements apply “both within and outside the practice of pharmacy” and include the principle of “acting with honesty, integrity and professionalism” that obliges students to “demonstrate high standards of personal and professional conduct at all times.”16 These standards, among others, are the same for pharmacists and those training to become pharmacists, and hence are important for students to be aware of, especially in the context of social media. This study aimed to investigate UK pharmacy students’ use of and views concerning social networking, including their awareness of professional issues. There has been limited research in this area conducted within pharmacy in the United Kingdom. A further aim was to investigate differences in the responses of male and female students as information for educators about how gender differences affect students’ attitudes and behaviors (in relation to use of social networking sites) is sparse.

METHODS

After reviewing the relevant literature,17-20 a self-administered questionnaire (available on request from the authors) was developed via SurveyGizmo (SurveyGizmo, Boulder, Colorado). The survey instrument consisted of 21 questions divided into the following 4 sections: use of social networking; online privacy and profile; professionalism and social networking; and demographic data (no identifiable information was requested). Most of the questions were closed, with pre-formulated answer choices. Twelve items asked students to rate attitudinal statements using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. A brief explanation of social media was provided as part of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire was internally reviewed for content validity by an expert in the field and assessed for face validity by 3 colleagues. Postgraduate pharmacy students (n=10) piloted the questionnaire and, as a result, minor changes were made to the wording of 2 questions. Completion time averaged 3 minutes. The School of Pharmacy Ethics Committee reviewed and approved the proposed research study.

The study population was all students (n=569) enrolled in the 4-year master of pharmacy (MPharm) degree program at Queen’s University Belfast. (The MPharm degree is the qualification that allows graduates to register as pharmacists in the United Kingdom.) In February 2012, all students were invited via e-mail to participate in the study (ie, a census approach was used). As clearly outlined in the e-mail invitation, students had 14 days to complete the questionnaire on SurveyGizmo.21 The e-mail contained a unique link to the questionnaire that allowed each student to complete the questionnaire only once. Two reminder e-mails which included a statement that other students had already completed the survey were sent to nonresponders. Other methods used to maximize the response rate included ensuring the questionnaire was relatively short, had a simple header, and appeared against a white background. Additionally, an incentive (respondents were entered in a drawing for 1 of 10 copies of a recommended textbook) was mentioned in the invitation.

Responses were coded and entered into SPSS for Windows, version 18 (International Business Machines (IBM), New York). As the data were non-normally distributed and ordinal in nature, nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis, and chi-square tests) were used to identify any associations between responses. Subanalyses were performed by respondents’ year in the program and gender. An a priori level of less than 0.05 (p<0.05) was set as significant. Missing data were not estimated or used in analyses.

RESULTS

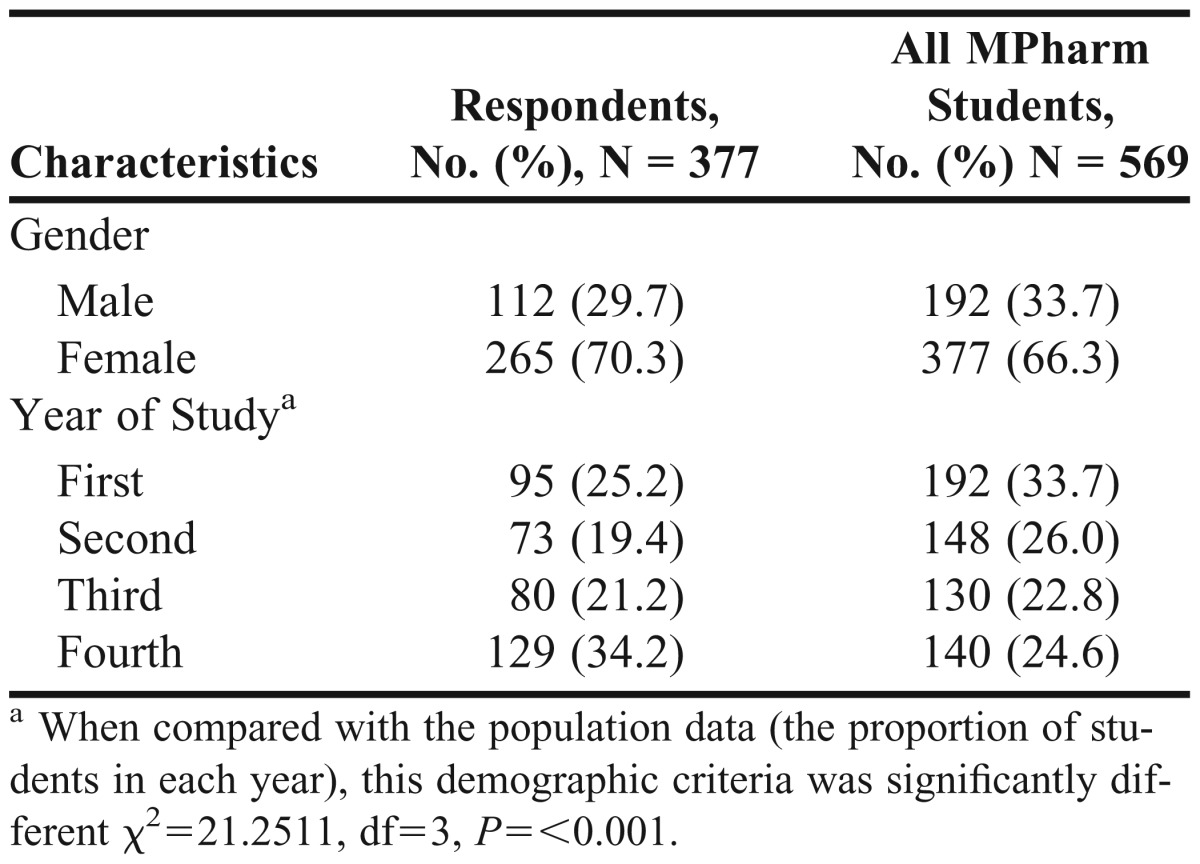

Three hundred seventy-seven of 569 students fully completed the questionnaire for a response rate of 66.2%. Demographic information about the respondents is presented in Table 1. There were less male students in the study than female students, but this was similar to the overall population of students enrolled in the pharmacy degree program (Table 1). There was a greater proportion of fourth-year students among respondents than other year groups.

Table 1.

Demographic Information of Students Enrolled in a Master of Pharmacy Degree Program

Use of Social Networking Web Sites

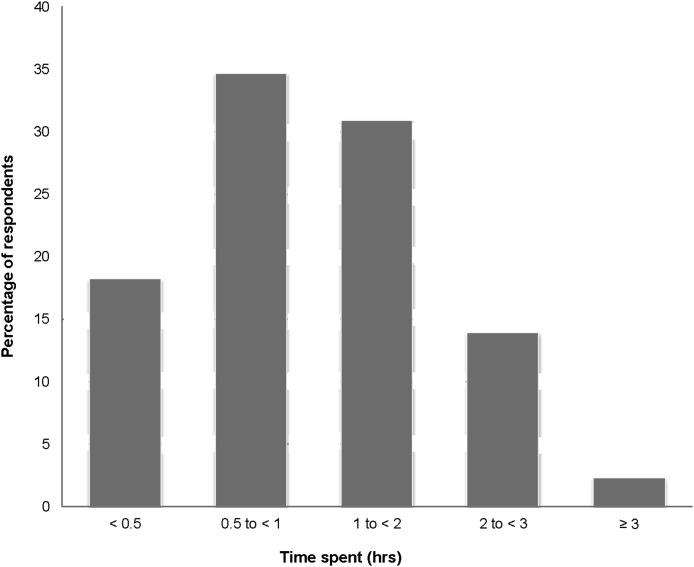

Most of the 377 respondents (91.8%) reported using social networking Web sites (this equates to 346 student users), with 98.6% using Facebook and 33.7% using Twitter. Approximately 40% used instant messaging services, such as Blackberry Messenger. The majority (98.0%) stated that their main purpose for using the sites was personal, rather than educational (1.7%) or professional (0.3%). While the main purpose of using the sites may have been related to personal use, 76.5% of students strongly agreed or agreed that they had used social networking sites to discuss academic-related problems. The amount of time spent on social networking Web sites is shown in Figure 1. Most respondents (83.8%) spent less than 2 hours per day using social networking Web sites, with a small minority (2.3%) spending over 3 hours on such sites in a typical day.

Figure 1.

Typical daily use of social networking sites.

There was a significant difference between the results for use between male and female students. Of the 112 male respondents, 87.5% used social networking sites, compared with 93.6% of female respondents (p=0.049). Male students who used social networking sites were also significantly more likely to use them for educational purposes than female students (5.1% vs 0.4%, p=0.003). This correlates with responses to the question “I have used social networking Web sites to discuss academic-related problems,” where 82.7% of male respondents were in agreement, as opposed to 73.8% of female respondents. While answers to this question were not significantly different in terms of gender, they were significantly different (p<0.001) between students in different years of the program. Students in their second year had used social networking Web sites most to discuss academic-related problems, with 88.6% strongly agreeing or agreeing, compared with 81.7% of third-year students, 67.9% of fourth-year students and 73.3% of first-year students.

Online Privacy and Profile

Most respondents were aware of privacy features on social networking sites that limited the amount of information available to the public (97.9% of the 377 respondents). While 321 (92.8% of the 346 users) students used these features to limit access to their information, approximately 7% (25/346) were aware of the privacy features, but chose not to use them. Most students thought their online profile and activity on social networking sites were an accurate representation of their character, with only 9.2% strongly disagreeing or disagreeing with this statement. Over two-thirds of all respondents strongly agreed or agreed that they were concerned about other users posting information that could adversely affect how they were perceived. When asked about their own posts, 45.2% of students agreed that they had posted material they would not want a prospective employer or university administrator to view. Slightly more respondents with privacy settings activated (than those who did not) had posted material they would not want university administration or an employer to view (46.7% vs 40.0%). A minority of students (13.8%) agreed that providing privacy settings were properly configured, it was acceptable to publish whatever you liked. However, only 27% of students thought that it was fair for an employer to use information from social networking Web sites when making a decision about employing someone.

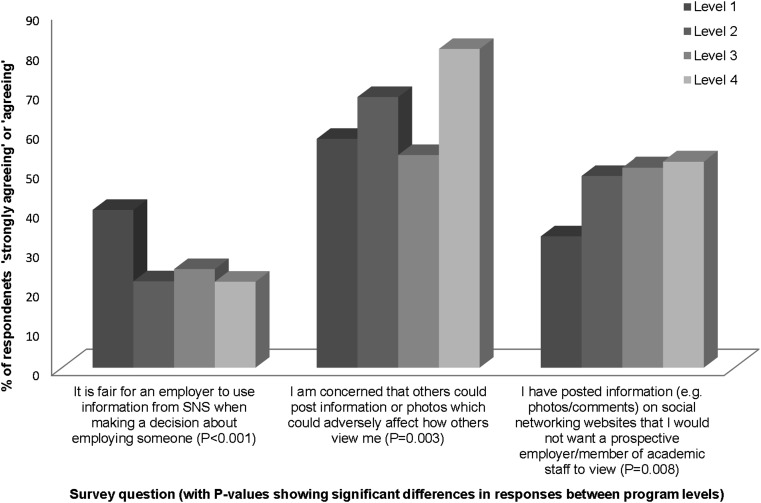

The only significant difference found in this section in relation to gender was with respect to the use of privacy settings. Male students made less use of privacy features available on social networking sites than did female students (82.7% vs 96.8%, p<0.001). However, there were several significant differences found when the responses for each year in the program were compared (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Responses (by program year) to questions regarding information posted on social networking sites.

Professionalism and Social Networking

The majority of students (71.1%) strongly agreed or agreed that they had been made sufficiently aware of the professional behavior expected of them when using social networking Web sites. Approximately the same level of agreement (71.9%) was found in response to the statement: “As a pharmacy student I should have the same professional standards regardless of whether I am using social networking Web sites or on a university placement.” Almost all students (97.1%) considered it unacceptable to make comments about patients (for example, drug abusers) on social networking sites, even if patient confidentiality was not compromised. However, over two-thirds of respondents (68.5%) considered that the reputation of pharmacy students would be adversely affected if members of the public were to view their social networking activities. In addition, 40.2% of users said they would change their behavior on social networking sites when they became a licensed pharmacist.

Male students were significantly less likely than female students to agree that they had been made sufficiently aware of the professional behavior expected of them when using social networking sites (58.1% vs 76.6%, p=0.002). There was also a significant difference (p<0.001) in responses to this question among students at different years in the program, with 92.6% and 93.2% of first- and second-year students in agreement, respectively, but only 60.1% of third-year students and 49.6% of fourth-year students. A greater percentage of female respondents than male respondents (p<0.001) agreed that students should have the same professional standards whether on placement or using social networking sites (76.3% vs 61.6%). The same question elicited the highest level of agreement with first-year students (84.3%) and then declined with each year, with only 61.3% of fourth-year respondents agreeing with this statement (p<0.001). Finally, male students were less likely than female students to agree that the reputation of pharmacy students would be harmed if their social networking activities were viewed by members of the public (60.7% vs 71.7%, p=0.011).

DISCUSSION

While the majority of respondents used social networking sites, female students were more likely to do so than male students. The most popular social networking site was Facebook, which attracted 98.6% of all student users, equating to 90.4% of all respondents. These figures are similar to those reported by Cain, who found that 88% of pharmacy students at 3 US colleges of pharmacy had Facebook profiles.17 However, differences in social media use between the sexes have not been reported in other studies of students in healthcare-related programs.17,22 Almost all students (98.0%) in this study stated that they used social networking sites mainly for personal reasons, rather than educational or professional reasons. However, most (76.5%) students acknowledged/agreed that they had used social networking sites to discuss academic-related problems. Indeed, the use of social networking sites to discuss academic-related problems, such as completing assignments, appears to be growing across years in the pharmacy program, with 88.6% of second-year students having used social networking sites for this purpose, compared with 81.7% of third-year students and 67.9% of fourth-year students. This pattern indicates a change within the student body in terms of how they seek help and may indicate that more students in early levels of the program see social networking sites as an academic aid, rather than purely a social tool. First-year respondents were less likely to use social networking sites for academic-related issues, as might be expected as they had completed fewer assessments. Also, having completed only 1 semester of the program, first-year students were unlikely to be as well “connected” with their peers as students in other years. Time spent using social networking sites was greater than that reported by other studies,23,24 although those studies focused solely on Facebook rather than social networking sites in general.

The majority of respondents (92.8%) stated that they used the privacy settings available within social networking sites. This figure is similar to that found by Osman25 who found that 93% of medical students had activated their privacy settings, higher than the 78.5% found by Cain and colleagues among pharmacy students.17 Given the publicity generated by high-profile cases surrounding inappropriate posts made on Facebook and other social networking sites, current users of social networking sites may have a greater awareness of the need to limit access to their profile. Male students in our study were significantly less likely to make use of privacy settings than their female counterparts, which reflects previous findings.26 This may be because female students are more cautious in their approach to online safety or have greater insight into potential problems accompanying more open profiles on social networking sites. Of the students who did not use privacy features, 40% responded that they had posted material that they would not want a prospective employer or member of academic staff to view, compared with 46.7% of those who did use privacy settings. This suggests that there is little difference in the reported behavior of students who use privacy features and those who do not, although further research would need to be conducted to validate this conclusion.

Many students (66.8%) had concerns about what others could post about them, with greatest concern shown among fourth-year students and the least concern shown among first-year students. A similar pattern of responses was found in relation to students posting material that they would not want an employer or member of academic staff to view (52.2% of fourth-year students vs 33.3% of first-year students). First-year students have had less time as pharmacy students to make inappropriate posts on social networking sites and are also less focused on future employment than fourth-year students. A significantly higher percentage of first-year students than other students thought that it was fair for a prospective employer to use information obtained from applicants’ social networking sites in making employment decisions. Overall, however, students did not think it was fair for employers to use information from social networking sites when making decisions about who to employ, with only 27% approving of this practice. In comparison, in the study by Cain and colleagues, 42.6% of students thought that information on a potential employee’s Facebook site should be used when making a hiring decision.17

Results relating to students’ views on how professional requirements provided by the university and regulatory body impacted their behavior on social networking sites were mixed. While almost all students (97.1%) considered it unacceptable to make anonymous comments about patients, only 71.9% thought that the same professional standards should apply whether on a social networking sites or a clinical placement. Many students apparently make a clear distinction between their conduct as professionals and their activities as individuals on social networking sites. Indeed, there appears to be a tacit acceptance by students that their current conduct would not be fitting as a pharmacy professional, with 40.2% stating they would change their behavior on social networking sites when they registered as a pharmacist. While many students acknowledged that they had been made aware of the professional behavior expected of them on social networking sites by the university, an interesting pattern emerges when student data are further analyzed by year in the program. First- and second-year students were more likely than third- and fourth-year students to strongly agree or agree that they had been told how to conduct themselves on social networking sites. This may reflect the impact of publication of the Code of Conduct for Pharmacy Students by the General Pharmaceutical Council (the main pharmacy regulator in the United Kingdom) in September 2010.27 Subsequent to its publication, workshops were introduced into the first year of the pharmacy program to highlight portions of the code and apply it to various aspects of student life, including social networking sites.

Even though all students within each level experienced the same guidance regarding appropriate conduct on social networking sites, female students were significantly more likely than male students to strongly agree or agree that they had been made aware of the behavior expected of them when using social networking sites. Female students were also more likely than male students to think that the reputation of pharmacy students would be adversely affected if their online activities on social networking sites were viewed by the public. In addition, significantly more female than male students felt that the same professional standards should apply to them whether on social networking sites or on clinical placements. These results can be interpreted in a number of ways. They may suggest that male students are less able to see professional dangers in the use of social networking sites and take a less holistic view of professionalism than female students. Alternatively, they may point to male students being more likely to have a philosophical objection to information on social networking sites being used to make judgments about professionalism. This information should be used by faculty members to tailor professionalism training within the area of social networking in order to reach students who are either unaware of privacy issues or are laissez-faire regarding their online profile. While such training should deal with common pitfalls and have wide appeal to all students, educators should ensure that examples resonate well with male students. This information may also prove useful when drafting guidance and policies on the acceptable use of social networking sites by pharmacy students.

In terms of study limitations, the opinions were captured at one point in time and were self-reported. Second, there was an overrepresentation of fourth-year students in the sample compared with the overall student population. The response rate (66.2%) of the student population (n=569) was reasonable28; however, the possibility of bias resulting from nonresponse cannot be ignored. The sample was similar to the population in terms of gender, which enhances the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, while the research was conducted with pharmacy students, many of the findings may be relevant and transferable to other healthcare-related disciplines and settings. Similarities were noted between this work and other studies documented in the literature (as discussed throughout). However, this study also provides new information on pharmacy students in a UK context and elucidates how gender differences influence attitudes and reported behavior with social networking sites.

CONCLUSION

Social networking sites, in particular Facebook, are popular among pharmacy students. Most student users are aware of the sites’ privacy features and choose to apply them, although male students are less likely than female students to do so. There is a significant difference in the attitudes of male and female pharmacy students to professional issues associated with the use of social networking sites. In general, male students appear more likely to make a distinction between their “professional” and private lives. Training in this area would help to ensure that students understand how codes of conduct apply in the online context, both now and in their future practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all pharmacy students at Queen's University Belfast who completed the questionnaire.

REFERENCES

- 1. Timeline. Facebook Newsroom. http://newsroom.fb.com/content/default.aspx?NewsAreaId=20. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 2. Key Facts. Facebook Newsroom. http://newsroom.fb.com/content/default.aspx?NewsAreaId=22. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 3. Teenage girls disciplined after posting offensive comments about teachers online. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews/8790309/Teenage-girls-disciplined-after-posting-offensive-comments-about-teachers-online.html. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 4.Read B. (2006). Think before you share. Chron High Educ. 2006;52(20):A. http://eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/recordDetail?accno=EJ756851. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 5.Gosden E. Students' trial by Facebook. http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2007/jul/17/digitalmedia.highereducation. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 6. BBC News England. Robin Hood Airport tweet bomb joke man wins case. July 27, 2012. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-19009344. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 7.Stone A. Swansea University bans Fabrice Muamba tweet student Liam Stacey. May 22, 2012. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/swansea-university-bans-fabrice-muamba-tweet-student-liam-stacey-7778520.html. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 8. The Telegraph. Doctors suspended after playing Facebook Lying Down Game. September 9, 2009. www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/facebook/6161853/Doctors-suspended-after-playing-Facebook-Lying-Down-Game.html. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 9.Laja S. Trusts reveal staff abuse of social media. The Guardian. November 9, 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/healthcare-network/2011/nov/09/trusts-reveal-staff-abuse-of-social-media-facebook. Accessed August 6, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nursing and Midwifery Council. Regulation in practice: social networking sites. http://www.nmc-uk.org/Nurses-and-midwives/Advice-by-topic/A/Advice/Social-networking-sites. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 11. British Medical Association. Using social media: practical and ethical guidance for doctors and medical students. 2009. http://bma.org.uk/-/media/Files/PDFs/Practical%20advice%20at%20work/Ethics/socialmediaguidance.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 12. American Pharmacist’s Association. APhA code of ethics for pharmacists. http://www.pharmacist.com/code-ethics. Accessed September 17, 2012.

- 13. American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy/American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans Task Force on Professionalism. AACP pledge of professionalism. http://www.aacp.org/resources/studentaffairspersonnel/studentaffairspolicies/Documents/pledgeprofessionalism.pdf. Accessed September 17, 2012.

- 14.Cain J, Romanelli F. E-professionalism: a new paradigm for a digital age. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2009;1(2):66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutter PM, Duncan G. Pharmacy professionalism and the digital age. Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19(6):431–434. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2011.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The Pharmaceutical Society of Northern Ireland. Code of ethics. June 2009. http://www.psni.org.uk/documents/312/Code+of+Ethics+for+Pharmacists+in+Northern+Ireland.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 17.Cain J, Scott DR, Akers P. Pharmacy students' Facebook activity and opinions regarding accountability and e-professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(6) doi: 10.5688/aj7306104. Article 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chretien KC, Greysen SR, Chretien JP, Kind T. Online posting of unprofessional content by medical students. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1309–1315. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cain J. Online social networking issues within academia and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1) doi: 10.5688/aj720110. Article 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonald J, Sohn S, Ellis P. Privacy, professionalism and Facebook: a dilemma for young doctors. Med Educ. 2010;44(8):805–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;10(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000008.pub4. MR000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giordano C. Health professions students' use of social media. J Allied Health. 2011;40(2):78–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross C, Orr ES, Sisic M, Arseneault JM, Simmering MG, Orr RR. Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Comput Human Behav. 2009;25(2):578–586. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joinson A. Looking at, looking up or keeping up with people?: motives and use of facebook. Proceedings of the 26th annual SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems: pp 1027–1036. http://people.bath.ac.uk/aj266/pubs_pdf/1149-joinson.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 25.Osman A, Wardle A, Caesar R. Online professionalism and Facebook: falling through the generation gap. Med Teach. 2012;34(8):549–556. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.668624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis K, Kaufman J, Christakis N. The taste for privacy: an analysis of college student privacy settings in an online social network. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2008;14(1):79–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27. General Pharmaceutical Council. Code of conduct for pharmacy students. 2010. http://www.pharmacyregulation.org/education/pharmacist/student-code-conduct. Accessed August 6, 2012.

- 28.Babbie E. 11th ed. California: Thomson Wadsworth; 2007. The Practice of Social Research. [Google Scholar]