Abstract

We explored factors influencing sexual and reproductive decisions related to childbearing for women living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. We conducted four focus group interviews with 35 women living with HIV/AIDS. Our results show that the sexual and reproductive healthcare needs of women were not being addressed by many health care workers. Additionally, we found that health care decisions were influenced by partners and cultural expectations of motherhood. Given the importance of motherhood, it is necessary for health care workers to address the diverse sexual needs and reproductive desires of women living with HIV/AIDS.

Our purpose in this article is to understand the sexual and reproductive (SR) needs and desires of women living with HIV and AIDS (WLHA) in South Africa. We examine the reproductive desires and cultural expectations of HIV positive women that may influence their SR decisions. Specifically, we examine: (a) contexts of vulnerability to risks for HIV/AIDS among women in South Africa; (b) factors that increase this vulnerability, and how such factors interfere with SR needs; and (c) conflicting expectations within family and health care settings. We begin by introducing some background information and providing the theoretical framework guiding the research project. We then present the findings within the context of women’s relationships and cultural expectations. Finally, we discuss the findings and implications for women living with HIV and AIDS in South Africa.

There is a disproportionate number of WLHA in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), especially in South Africa (Shisana et al., 2009; UNAIDS, 2009). In 2009, 13.4 million out of the 22.4 million people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA) in SSA were women (UNAIDS, 2009). Most (76%) were young women between the ages of 15 and 24 years, and people in this age group were three times more at risk of contracting HIV than young men (UNAIDS, 2008). In 2008, South Africa had 5.7 million PLWHA, 3.2 million of whom were women aged 15 years and over (UNAIDS, 2008). According to recent statistics, the most at risk for HIV in South Africa is women between the ages of 20 and 39 years, with HIV prevalence rates of 6.7% (ages 15-19), 21.1% (ages 20-24), 32.7% (ages 25-29), 29.1% (ages 30-34), 24.8% (ages 35-39), and 16.3% (ages 40-44) (Shisana et al., 2009).

While the research in this area has mostly focused on the economic and care-giving demands that HIV/AIDS imposes on women, pregnancy decisions, and contraceptive use after disclosure, few studies have explored the complex socio-cultural expectations associated with decisions to bear children among WLHA in Africa (Cooper, Harries, Myer, Orner, & Bracken, 2007; Nduna & Farlane, 2009; Rutenberg, Biddlecom, & Kaona, 2000; Smith & Mbakwem, 2007; Wusu & Isiugo- Abanihe, 2008). In order for health care workers (HCWs) and family members to better support the childbearing decisions of WLHA, it is not only important to understand the SR needs and desires expressed by these women, but also to provide capacity building resources for HCW to address those needs.

Cultural expectations for childbearing have been found among women worldwide, in locations as diverse as Cape Town, South Africa (Myer, Morroni, & El-Sadr, 2005), Burkina Faso (Nebié et al., 2001), Brazil (da Silveira Rossi, Fonsechi-Carvasan, Makuch, Amaral, & Bahamondes, 2005), Nigeria (Smith & Mbakwem, 2010), and the United States (Chen, Philips, Kanouse, Collins, & Miu, 2001). Several authors have documented how socio-cultural expectations are revealed in the ways in which the desire for children competes with anxiety over exposure to HIV. For example, Rutenberg et al. (2000) examined the perception of risk and presence of HIV symptoms among Zambian women. They found that when the perception of risk was high, or HIV signs and symptoms were present, men and women were against WLHA bearing children. However, Cooper et al. (2007) examined individual factors among HIV positive women that influenced reproductive decisions and found that being HIV positive did not eliminate reproductive desires due to socio-cultural expectations associated with childbearing. Likewise, in a study on the sexual behavior of PLWHA who used antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) in Nigeria, Smith and Mbakwem (2007) reported that marriage and reproduction were of utmost importance to PLWHA. Thus, it appears that ARV availability has contributed significantly to sustaining reproductive desires among many HIV positive women over the last decade, despite variations in reproductive intentions and expectations.

Indeed, several authors have documented how, in South Africa, ARVs have been embraced because they promote favorable childbearing for WLHA (Cooper et al., 2007, 2009; Myer et al., 2007; Harries et al., 2007; Maier et al., 2008; Nduna et al., 2009; Nattabi et al., 2009). However, many policy makers and healthcare providers in South Africa have expressed unfavorable opinions about childbearing by HIV positive women stemming from a lack of clear reproductive health policy guidelines and a shortage of health care providers to adequately meet the women’s reproductive needs (Harries et al., 2007). In addition, judgmental attitudes and disapproving comments from HCWs in South Africa have caused many women to remain silent about their reproductive desires (Cooper et al., 2007; Nduna & Farlane, 2009). Greeff et al. (2008) concluded that in South Africa, Malawi, Tanzania, Lesotho and Swaziland, this distrust of HCWs has prevented PLWHA from fully accessing and utilizing available health care services. The present study adds to the growing body of literature on how WLHA navigate their reproductive desires, given socio-cultural reproductive expectations that tend to conflict with attitudes in health care settings. Family members encourage women to have children while some HCWs discourage them; thus, HIV imposes additional burdens on women as they cope with anxiety over exposure. For this reason, we explore conflicting cultural expectations in both family and health care settings, and how these influence the reproductive desires of South African WLHA.

Theoretical Framework

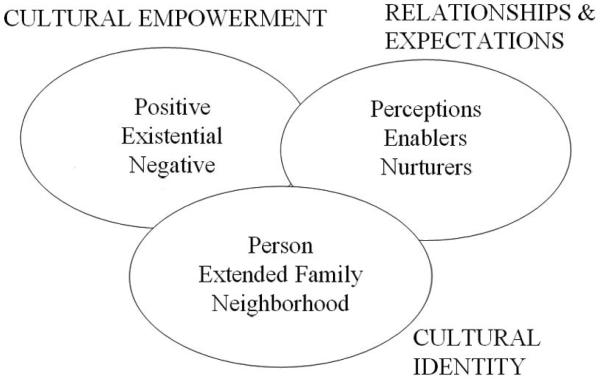

The organizing framework that guided the study was the PEN-3 cultural model, which was developed to examine the role culture plays in addressing health behaviors and decisions made by people from African countries (Airhihenbuwa, 2007; Airhihenbuwa & Webster, 2004). PEN-3 has three domains, and each domain has three dimensions (see Figure 1). The three interconnected domains are cultural empowerment, relationships and expectations, and cultural identity. In the first domain, cultural empowerment, PEN stands for Positive values that promote personal health decisions or behaviors; Existential values, unique cultural attributes that pose no threat to personal health; and Negative values, health decisions or behaviors rooted in cultural practices that may cause personal harm. In the second domain, relationships and expectations, PEN stands for perceptions held by people that may promote or hinder health behaviors and decisions; enablers that may encourage or discourage healthy behaviors and practices; and nurturers who provide support by reinforcing or discouraging behaviors. The third domain, cultural identity, is usually the point of entry for intervention, and examines how one’s identity plays a critical role in influencing decisions in the context of the person, the extended family and the neighborhood. PEN-3 has been used in related publications on this project to address the nature of overall stigma relative to culture and identity (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2009), the role of family (Iwelunmor, Airhihenbuwa, Okoror, Brown, & BeLue, 2007), the role of motherhood (Iwelunmor, Zungu, & Airhihenbuwa, 2010), and the role of food (Okoror et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

The PEN-3 Model

For the purpose of this study, the PEN-3 model was used to develop the focus group interview guide used for data collection and to guide the data analysis. This allowed us to ask questions that are relevant to the domains of the model, yet flexible enough to explore other emergent issues such as the care of children after death and reversal of care giving role, that may not fall within the PEN-3 domains.

Methods

Participants

The data for this qualitative study were collected as part of a larger, 5-year capacity building research project designed to train postgraduate students from the University of the Western Cape, University of Limpopo, and the Pennsylvania State University to conduct research on HIV and AIDS using the PEN-3 model to frame an understanding of stigma (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2009). The overall goal of the project was to examine the different contexts that contribute to HIV/AIDS stigma in the family, community and healthcare. Specifically, the data used in this paper were collected in April 2006, during the third year of the project. Purposive sampling was used to identify and recruit 35 eligible participants from four previously established HIV and AIDS women’s support groups in Limpopo. None of the women approached to participate in the study refused and there were no participants who dropped out of the study. Although some of the women knew each other, most of them met each other and the facilitator for the first time during the focus groups. Participants in each focus group were selected from four different support groups. The purpose of the study and the process involved was explained to participants in either English or Northern Sotho and informed consent was obtained from each participant both verbally and in writing. The interviews were audio recorded and the digital audio recorder and laptops containing all information were stored in the office of the project director. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Pennsylvania State University and the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa.

Data Collection

We conducted four focus group interviews, and a member of the research team responsible for community entry recruited the women into the study. A trained graduate student facilitated the focus group discussion while a second graduate student served as the co-facilitator and recorder of the focus groups. There were 8 or 9 women in each group. Since the goal of the original project was to examine the different contexts that contribute to HIV/AIDS stigma in the family, community and healthcare, the word stigma was not used in the interview guide so as not to predetermine the participants’ responses (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2009).

Focus group interview guide

We based the focus group interview guide (see Appendix A) on previous research with this population. Although the interview guide did not directly ask questions about the sexual experiences, reproductive desires, and the challenges WLHA face, additional probes were used during the interviews to delve more deeply into the issues related to SRH already mentioned by the participants. The fact that SRH issues emerged from participant’s responses, even though we did not directly set out to ask those questions shows that these issues are important to WLHA. In particular, probes for the positive, unique (existential) and negative factors on the role of healthcare led us to the focus on reproductive desires, and cultural expectations surrounding childbearing decisions of WLHA and how these expectations are managed in both the family and health care settings. Some of the additional probes used were: 1) What are your views on the role of the healthcare in contributing to how women living with HIV are treated? 2) Are there any restrictions placed on you in your family, and/or at the health center because you are a woman living with HIV/AIDS? 3) What are some of the challenges you face as a WLHA in obtaining (sexual and reproductive) healthcare services at the clinic?

We only used some of these additional probes when the group initiated the topic on sexual health and childbearing to prompt further detailed responses. We excluded questions pertaining to status disclosure, as they were already published elsewhere (Iwelunmor et al., 2010). In the focus group interviews, which lasted about 60 to 90 minutes, we used an open-ended, semi-structured interview guide created by a trained South African graduate student in either Northern Sotho or English. Experienced translators at the Human Science Research Council (HSRC) later translated the transcripts into English to ensure validity of the data.

Data Analysis

We collected and entered all focus group data into NVivo 2.0, a software program for organizing qualitative data (QSR, 2002). Consistent with Glaser and Strauss’ (1967) approach to open coding, we generated free nodes. We then organized these free nodes into related categories or themes guided by the PEN-3 model to generate tree nodes (axial codes). Finally, we organized emerging themes into categories within the PEN-3 model based on concepts that emerged from participant responses. The model does not require each category to be filled or that all of the three domains be used (Erwin, et al., 2010; Iwelunmor, et al., 2010; Okoror, et al., 2007). In addition, each graduate student kept a reflective log of ideas that surfaced during the coding process. To ensure reliability and validity of the data, two other graduate students reviewed the codes. It should be noted that the Cultural Empowerment, and Relationships and Expectations domain was specifically used for grouping the themes.

Results

Consistent with PEN-3, we examined the final themes within the context of the relationships and expectations domain and the cultural empowerment domain. We did a cross-tabulation of the relationships and expectations domain with the cultural empowerment domain and positioned the emerging themes in a 3×3 table. The quotes in each category indicate positive, existential, and negative experiences along with perceptions of the women’s views, enablers in the form of HCW contributions to reproductive decision making, and nurturers in the form of family member contributions to reproductive decision making. Since PEN-3 encourages the flexibility of not filling every cell of the 3×3 table, not all themes were grouped into the nine categories of the table. Some of the themes did not apply, and others were very similar.

Positive Perceptions

Positive perceptions in this paper refer mostly to the knowledge, beliefs and attitudes expressed by WLHA on how accepting their HIV status has empowered them to make healthy choices, eat well or take care of their bodies. The following comments illustrate these perceptions:

My life changed after realizing my HIV status. It is better because I know and I now live well… Since I started knowing my status I see my life changed too much because the life I was living before, maybe I wouldn’t be alive today. Now I know what to eat and how to look after my body.

In addition, attitudes like wanting to be healthy in order to live long enough to look after children or fulfill family responsibilities were positively influenced by decisions to adhere to medication. For example, one female participant who discovered she was HIV positive while pregnant said, “I normally don’t take pills, but I take them for my baby.” Similarly, another participant discussed family responsibilities as motivating factors for taking medication:

I was not able to do anything, doing the washing or cooking [for my family]. I was unable to do that. At the hospital my wish was for the healthcare workers to give me some pills to drink so that I can be able to wash for my children.

Thus, most HIV prevention and care actions were taken by these women with their children in mind. A woman’s obligations to her family, especially her children and husband provided positive reinforcement for taking proper care of her health.

Existential Perceptions

We categorized comments on the unique opportunity women have to give life through childbirth as existential perceptions. One participant said, “Giving life to a newborn child [means] if I want to feel love then I have to do the right thing and the right thing was to look after my child and do everything for my child.” Giving life to another helped these women regain a sense of normalcy in their lives by having a reason to live and view life positively. “It [giving birth] is a good thing because… he was brought into this world by me to care for, not that he asked to be here and so I see myself in a positive way also.” These perceptions reflect the value of motherhood that is embodied in WLHA wanting to do whatever it takes to care for their children.

Negative Perceptions

We categorized responses that negatively affected decisions WLHA made about HIV prevention, such comments on the difficulties encountered in negotiating condom use, as negative perceptions. These perceptions were usually borne out of myths related to condom use. In particular one woman recounted her experience by saying:

They told us at the clinic that we must use a condom for the rest of our lives, he agreed at the clinic but when we arrived at home, he [her husband] said, “I can’t be able to use a condom, because I lose children.”

In addition, a number of women commented on how they still had to fulfill the caregiver role in their families, regardless of their health statuses. Managing the illness and shouldering different family responsibilities was a source of stress on women. One woman commented:

We come to a point where [we] feel self pity. All the responsibility is on your shoulders. For a woman, you may be sick like say you HIV positive and if your child is sick or your husband is sick then you take care of that child or your husband … It’s also a lot of strain on us they still depend on us… because you the woman, you the wife, you the mother… even though you are positive you must still be a wife. You must still be a mother, you must still work.

Positive Enablers

Positive enablers refer to resources and institutional support, such as views expressed by HCWs on HIV positive motherhood that are beneficial and pose no health risk. In some instances, women reported that HCWs were supportive of them by paying more attention to them and being sympathetic to their needs. One participant reported:

In the clinics, nurses will take it from a woman’s side like this is a woman I must help this lady or this is a mother I must help her because she also feels that way so some women [nurses] can identify with you as a woman.

Also when it comes to the delivery process, WLHA are given more attention than those who are HIV negative:

The one who is HIV positive will get more attention than the one who doesn’t know [her HIV status]; doctors will be there when you give birth to ensure that everything goes accordingly. But the one who is not HIV positive will be assisted by nursing sister to give birth, when they are through, they will sit down with her and give her a special counseling.

Access to HIV testing during antenatal care makes it possible for many women to learn of their HIV status while they are pregnant or during delivery. One woman said, “For me also I found out I was HIV positive when I gave birth to my first born.” Another woman confirmed, “If it wasn’t for him [baby], I wouldn’t have even known my status.” Similarly, another woman reported, “I became pregnant in 1997 and then I went to the hospital attending antenatal group. I took the blood test.”

Negative Enablers

Negative enablers refer to resources and institutional barriers within the health care system that are unsupportive of childbearing by HIV positive women. Many times, these are detrimental and pose a health risk to women. In some instances, this lack of support came across in conversations with HCWs, as reported by one participant: “The doctor told me that ‘Your baby is infected with HIV, you must stop bearing children’… He just said it without feeling sorry for me.” Another participant mentioned how she and other WLHA were chastised by HCWs whenever they sought contraceptive measures. She expressed her anger and frustration, saying:

I am looking at the issue of condoms, most of the time they [healthcare workers] refuse people who are living with HIV/AIDS to take them, because they think they will infect others, they forget about STI’s, and that HIV is not the only one that we try to prevent.

Lastly, our findings reveal that HCWs were communicating mixed messages by telling WLHA they “must not bear children, even though sex is natural… to increase ourselves,” yet they were not properly equipping them with the necessary contraceptive measures needed. This was alluded to by a participant who said, “The thing that I am not happy about and don’t understand is that they restrict us from using contraceptives measures… and then say we must not bear children.”

Positive Nurturers

Positive nurturers include supportive family members, especially partners, and community members, who influence decisions WLHA make regarding their reproductive intentions. Support from partners and significant others made it easier for them to make positive health decisions. In some instances, WLHA reported that their partners supported the use of condoms, after initial resistance. One woman suggested that after explaining to her partner the reason why they had to introduce condoms into their relationship, he eventually agreed:

He said he is not satisfied with a condom… I explained to him that “if you say you lose children, my life is at stake here, so if you don’t want to use a condom, we better separate.” He said, “Because you’re saying so, let’s use it.”

Another woman reported her experience after she disclosed her status to her partner:

I explained everything, and he never had a problem… He didn’t want us to use a condom; we ended up having another baby. But I was forcing him to use a condom… now he understands the issue of a condom.

Negative Nurturers

Negative nurturers are unsupportive partners and significant others who negatively influence the decisions of WLHA once status is disclosed. Many participants reported that they experienced separations, break-ups and marital discord after disclosing HIV positive status to sexual partners or spouses. One participant recounted her experience of how her HIV positive partner was not supportive of practicing safer sex:

I told my partner immediately after knowing that I’m HIV positive… and said, “We must start using a condom…” We were fighting when it comes to the issue that we must have a protected sex. Sometimes after wearing it, with anger he will take it off and throw it away. He ended up saying that he doesn’t want to use a condom when he sleeps with me… He left me.

Apart from the emotional effect of marital discord, some women reported that it also had a detrimental effect on their physical health. Not only did they have to deal with living with HIV and AIDS, they also had to deal with the emotional heartbreak caused by separation. One woman recounted what happened after disclosing her HIV positive status and to her husband:

After coming from the hospital, I said, “I have this disease,” he didn’t accept, he refused. He married another woman… I became terribly sick, after that, I was very sick. In fact the thing that worsens my illness is that he separated with me.

Discussion

Bearing in mind the importance of childbearing in the lives of South Africans and others, we explored the factors that influence the experiences and reproductive decision making of WLHA. Our findings led us to conclude that SR decisions of WLHA are largely dependent on a number of different factors, most importantly, partners, HCWs and families. In addition, the power to make such decisions depends on the information available to these women and how independent or autonomous they are within their families and society at large. Airhihenbuwa (2007) made a distinction between autonomy and independence to frame the different agencies of a woman’s decision making ability in different cultural settings; autonomy does not mean being independent in and of itself, but “as long as one’s role and contribution in society are duly recognized and valued economically, culturally, and socially” (Airhihenbuwa, 2007, p. 92). Many women in our study did not have the independence or autonomy to go against socio-cultural childbearing expectations, even though the possibility of having an infected child was frightening.

The factors influencing the reproductive decisions of the women in our study were: (a) fulfilling cultural norms associated with childbearing, (b) pressure from partners/spouses, (c) HCW attitudes, and (d) fear that not having a child could lead to separation, divorce or extramarital affairs. Many notable African feminist scholars have argued that motherhood is central to an African woman’s identity (Amadiume, 1987; Nnaemeka, 1997; Nzegwu, 2006; Oyewumi, 1997). South Africa is no exception when it comes to the high value placed on being a mother. Many times, the roles women occupy in society as wives and mothers influence the decision to get tested for HIV, and to eventually disclose a positive status (Iwelunmor et al., 2010). This is illustrated by the fact that more women get tested than men because of the emphasis on testing during antenatal clinic visits; many women learn their HIV positive statuses either when they are pregnant or immediately after giving birth (Cooper et al., 2007; deBruyn, 2002; ICW, 2008). After being tested and diagnosed as HIV positive, the motherly role of WLHA within the family and community is still very important. Our findings reveal that the agency of a mother is vital, as she still has to shoulder the responsibility of caring for her husband and children. Being HIV positive does not absolve a woman from her responsibilities within her family and in her community. To help women fulfill these responsibilities while managing their diagnoses, Airhihenbuwa (2007) noted that many WLHA are more inclined to join support groups that affirm their roles as mothers, or as the caregivers for their families and society. For many women, these support groups help them develop coping strategies for playing the dual role of caring for family and managing personal health by sharing ideas with other women in the same situation. This was indeed seen in the interactions among WLHA in the support groups we sampled.

Second, having children is expected as a necessary part of a “successful” marriage in traditional African society. Consistent with findings from previous studies, married women reported facing more pressure to bear children from their husbands and extended family, which could place additional stress on WLHA (Cooper et al., 2007; Iwuagwu, 2009). It is not surprising that due to pressure from their families, some husbands separated from their wives after HIV positive status was disclosed. Many times, regardless of HIV positive status, disclosure status or sexual desire, WLHA give in to the pressure of having children, who then may or may not become HIV positive. WLHA who decided against having children after diagnosis did so because they feared having an infected child, or because they already had children prior to diagnosis. Similar findings by Cooper et al. (2007) and the International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS (ICW, 2008) revealed that unmarried women and women who already had children before being diagnosed with HIV said they had more autonomy in being able to withstand the pressure to bear children. On the other hand, those women without children prior to an HIV diagnosis are more likely to acquiesce to the cultural expectation of childbearing, have strong reproductive desires to bear children, and may feel more pressure to do so (Cooper et al., 2007; ICW, 2008). This finding was confirmed in our study, as several women remarked that they still had dreams of getting married, having children and having families of their own.

Finally, motherhood is a positive agency within which women can exercise power, control and make decisions. HIV/AIDS challenges this status so desired by many young African women (Okome, 2001). Harries and colleagues (2007) explained that after some time on intense ARV treatment, patients begin to feel better and become more hopeful and optimistic that they are not going to die anytime soon. Similar findings were echoed by Smith & Mbakwem (2007, 2010). This finding was also reflected in our study, with some women stating that they took pills (ARV) and made lifestyle changes. This restored hope motivated them to get pregnant, have children, and manage their health so they could live longer, look after their children, and continue their family responsibilities. Even though medical interventions, such as ARVs that prevent mother to child transmission, have restored the desire to have children in many women, some still fear infecting future children.

In addition, many women in our study were angry and frustrated at the negative attitudes of HCWs toward their SR health care needs. Similar to findings from Iwuagwu (2009), some WLHA reported that HCWs implied through verbal or non-verbal cues that they should not get pregnant. At the same time, they were chastised by HCWs whenever they sought contraceptives to prevent pregnancy and HIV transmission. Such negative attitudes often prevent WLHA from discussing their sexual needs and reproductive intentions with HCWs, and discourage them from obtaining necessary information and support for navigating SR goals while living with HIV. However, some women reported that HCW were supportive by showing more empathetic feelings towards them. This finding is similar to those reported by Sofolahan et al. (2011) that nurses showed more emotional empathy for WLHA they could identify with as wives, mothers and caregivers.

Limitations

Some limitations of this study are worth noting. The results of this qualitative study may not be applicable to other contexts or settings, because most of the women who participated in the focus group discussions were already on ARV treatment, and all were attending support groups for women living with HIV and AIDS. It should be noted that despite the resilience of these women in seeking appropriate medical care and support needed, they still experienced significant vulnerabilities towards childbearing as a result of their HIV status. Another limitation is that due to the sensitive nature of the topic, some of the participants may not have been comfortable talking about their sexuality, and may not have been forthcoming about all of their reproductive desires and sexual experiences. Lastly, we did not collect demographic information on marital status or current number of children; however, we were able to discern this information in most cases based on discussion contexts. Having this information for all the women would have provided more insight into understanding some of their views and placing their comments within such contexts.

Conclusion

Findings from other studies have shown a strong desire for women living with HIV to have children, especially among women who have no children and among younger women with fewer children. This sentiment is not exclusive to African women, as similar trends have been observed in Europe (Chen et al., 2001), South America (Paiva et al., 2007) and North America (Myer et al., 2005). These studies emphasize the need to integrate SR health care services into HIV/AIDS care so that informed reproductive decisions can be made by WLHA. Several conclusions can be drawn from the results of our study. The first was that a woman’s love for and her desire to protect her children and family served as a positive reinforcement for her to take better care of her health, by adhering to her medications or seeking care. The second was that the support of HCW was viewed as important towards successful childbearing. The third was that partner support, either through condom use or not abandoning the relationship, was critical to the well being of WLHA.

As a cultural identity marker, motherhood highlights that the reproductive desires, cultural expectations and experiences of women are deeply rooted within the collective – the family and the community. Given the importance placed on motherhood, and its centrality to an African woman’s identity, non-judgmental support from HCWs and family members must be given to WLHA in order for them to make informed SR decisions. With the extremely challenging conditions under which many HCWs work in South Africa and many other African countries, they need capacity enhancement training sessions to be able to provide quality care to WLHA. Sofolahan et al. (2011) concluded that because of the work overload, and ‘stigma by association’ experienced, many nurses may not be properly equipped to deal with the demands and complexities of caring for PLWHA while managing their family responsibilities. Because of the critical role HCWs play in ensuring WLHA have healthy and fulfilling lives, it is important for future studies to examine the SR health information HCWs think is necessary for WLHA. Furthermore, the information conveyed by HCWs should be compared to the SR health information WLHA report that they actually need. Finally, the attitudes of HCWs towards WLHA’s SR health should also be examined in terms of how they are disseminating the needed information. It is necessary for HCWs to take the sexual needs and reproductive desires/intentions of WLHA into account when disseminating information. In this way, WLHA will be more likely to heed the messages HCWs are providing, allowing them to better support their reproductive needs. Future interventions in the form of a capacity building project for HCW should be developed. The goal of the project should be to strengthen the care giving capacity for HCW caring for PLWHA.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health; R24 MH068180. The authors would like to thank the HIV and AIDS Stigma Project Team, Ms. Zungu for managing data collection in South Africa and Linda Malatji for collecting the data.

Appendix A: Focus Group Interview Guide The Experiences of Women Living with HIV and AIDS

- What are your views about HIV/AIDS?

- What do you think influenced you to hold these views?

- Are your views shared by others in the family and community?

- What are some positive things in your community that are supportive of PLWHA?

- What are some negative things in your community that are against PLWHA?

-

How would you say PLWHA are treated in the family?

PROBE: How are you treated at home, in your community or at the hospital?

Are you as a woman LWHA treated differently than others?

How about male LWHA? Are they treated differently?

What are your views about the role of the healthcare in contributing to how WLHA are treated? PROBE: Please share examples of how they may be supportive or not supportive?

- *How long did it take before you disclosed your status?

- Who was the first person you spoke to?

- Why did you choose this person?

- How did this person react? PROBE: How did their reaction make you feel?

- How did your husband/partner and other members of your family and community react to your status?

- Is there a difference in the way the community deals with people who are HIV positive?

- Are there any restrictions placed on you as a WLHA in your family, community or hospital? PROBE: Is there anything you are restricted from doing in the family, community or hospital? PROBE: What challenges do you mostly face in the family, community, or at the hospital in moving on with your life such as in obtaining reproductive healthcare? (This probe was only used after WLHA had spoken about their SRH).

- Do you think it is different for a man? How?

- How has your life changed after being informed of your status?

- At home, in the family, and within the community.

- Do you think it is different for a man?

- Have you had any counseling? With whom and how were you able to access counseling?

- What kind of assistance or advice do you get from a support group? PROBE: What kind of advice do healthcare workers give you? (This probe was only used after WLHA had spoken about also getting advice about their SRH from HCW).

Is there anything else you might want to add regarding HIV and AIDS?

* Denotes questions pertaining to status disclosure that were omitted from this paper.

References

- Airhihenbuwa C. Healing our differences – The crisis of global health and the politics of identity. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; Lanham, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa C, Okoror T, Shefer T, Brown D, Iwelunmor J, Smith E, Shisana O. Stigma, culture, and HIV and AIDS in the Western Cape, South Africa: An application of the PEN-3 cultural model for community-based research. Journal of Black Psychology. 2009;35(4):407–432. doi: 10.1177/0095798408329941. doi: 10.1177/0095798408329941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO, Webster DJ. Culture and African contexts of HIV/AIDS prevention, care and support. SAHARA Journal. 2004;1(1):4–13. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2004.9724822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadiume I. Male daughters, female husbands: Gender and sex in an African society. Zed Books; London, UK: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Philips KA, Kanouse DE, Collins RL, Miu A. Fertility desires and intentions of HIV-positive men and women. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33(4):144–152. 165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D, Harries J, Myer L, Orner P, Bracken H. “Life is still going on”: Reproductive intentions among HIV-positive women and men in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(2):274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.019. doi: DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D, Moodley J, Zweigenthal V, Bekker L, Shah I, Myer L. Fertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Rown, South Africa: Implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care services. AIDS Behavior. 2009;13:S38–S46. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9550-1. doi: DOI: 10.1007/S10461-009-9550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira Rossi A, Fonsechi-Carvasan GA, Makuch MY, Amaral E, Bahamondes L. Factors associated with reproductive options in HIV-infected women. Contraception. 2005;71(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.07.001. doi: DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deBruyn M. Living with HIV: Challenges in reproductive health care in South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2002;8(1):92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Trevino M, Saad-Harfouche FG, Rodriguez EM, Gage E, Jandorf L. Contextualizing diversity and culture within cancer control interventions for Latinas: Changing interventions, not cultures. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(4):693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing Co; Chicago, IL: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Greeff M, Phetlhu R, Makoae LN, Dlamini PS, Holzemer WL, Naidoo JR, Chirwa ML. Disclosure of HIV status: Experiences and perceptions of persons living with HIV/AIDS and nurses involved in their care in Africa. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(3):311–324. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311118. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries J, Cooper D, Myer L, Bracken H, Zweigenthal V, Orner P. Policy maker and health care provider perspectives on reproductive decision-making amongst HIV-infected individuals in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):282. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICW HIV positive women, pregnancy and motherhood. International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS (ICW) Retrieved from. 2008 http://www.icw.org/files/briefingpaper-%20motherhood%2009-08.pdf website.

- Iwelunmor J, Airhihenbuwa C, Okoror T, Brown D, BeLue R. Family systems and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2007;27(4):321–335. doi: 10.2190/IQ.27.4.d. doi: 10.2190/IQ.27.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwelunmor J, Zungu N, Airhihenbuwa CO. Rethinking HIV/AIDS disclosure among women within the context of motherhood in South Africa. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(8):1393–1399. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168989. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.168989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwuagwu S. Nigeria. Ph.D. doctoral dissertation. Southern Illinois University Carbondale; Carbondale, IL: 2009. Sexual and reproductive decisions and experiences of women living with HIV/AIDS in Abuja. [Google Scholar]

- Maier M, Andia I, Emenyonu N, Guzman D, Kaida A, Pepper L, Bangsber D. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased fertility desire, but not pregnancy or live borth among HIV+ women in an early HIV treatment program in rural Uganda. AIDS Behavior. 2009;13:S28–S37. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9371-7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9371-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Morroni C, El-Sadr WM. Reproductive decisions in HIV-infected individuals. Lancet. 2005;366(9487):698–700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67155-3. doi: S0140-6736(05)67155-3 [pii]10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Morroni C, Rebe K. Prevalence and determinants of fertility intentions of HIV-infected men and women receiving anriretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2007;21(4):278–285. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0108. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattabi B, Li J, Thompson S, Orach C, Earnest J. A systematic review of factors influencing fertility desires and intentions among people living with HIV/AIDS: Implications for policy and service delivery. AIDS Behavior. 2009;13:949–968. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9537-y. doi: 10.1007/s10461-00909537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nduna M, Farlane L. Women living with HIV in South Africa and their concerns about fertility. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(0):62–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9545-y. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9545-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebié Y, Meda N, Leroy V, Mandelbrot L, Yaro S, Sombié I, Dabis F. Sexual and reproductive life of women informed of their HIV seropositivity: A prospective cohort study in Burkina Faso. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;28(4):367–372. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200112010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nnaemeka O. The politics of (m)othering: Womanhood, identity, and resistance in African literature. Routledge; New York, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nzegwu N. Family matters: Feminist concepts in African philosophy of culture. State University of New York Press; Albany, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Okome M. African women and power: Reflections on the perils of unwarranted cosmopolitanism. JENdA. 2001;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- Okoror T, Airhihenbuwa C, Zungu N, Makofani D, Brown D, Iwelunmor J. “My mother told me I must not cook anymore”-Food, culture, and the context of HIV- and AIDS-related stigma in three communities in South Africa. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2007;28(3):201–213. doi: 10.2190/IQ.28.3.c. doi: 10.2190/IQ.28.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyewumi O. The invention of women: Making an African sense of western gender discourses. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis, MN: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva V, Santos N, França-Junior I, Filipe E, Ayres JR, Segurado A. Desire to have children: Gender and reproductive rights of men and women living with HIV: A challenge to health care in Brazil. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21(4):268–277. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0129. doi: doi:10.1089/apc.2006.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR . NVivo 2.0: Using NVivo in qualitative research (computer software & manual) Melbourne, Australia: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rutenberg N, Biddlecom AE, Kaona FAD. Reproductive decision-making in the context of HIV and AIDS: A qualitative study in Ndola, Zambia. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;26(3):124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S,J, Pillay-van-Wyk V, SABSSM III Implementation Team . South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey, 2008: A turning tide among teenagers? Human Sciences Research Council Press; Cape Town, South Africa: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Mbakwem BC. Life projects and therapeutic itineraries: Marriage, fertility, and antiretroviral therapy in Nigeria. AIDS. 2007;21:S37–S41. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000298101.56614.af. 10.1097/1001.aids.0000298101.0000256614.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Mbakwem BC. Antiretroviral therapy and reproductive life projects: Mitigating the stigma of AIDS in Nigeria. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(2):345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.006. doi: DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofolahan YA, Airhihenbuwa CO, Makofane DM, Mashaba E. “I have Lost Sexual Interest…”-Challenges of Balancing Personal and Professional Lives among Nurses Caring for People Living with HIV and AIDS in Limpopo, South Africa. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2011;31(2):155–169. doi: 10.2190/IQ.31.2.d. doi: 10.2190/IQ.31.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS: Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2008 Retrieved from http://data.unaids.org/pub/GlobalReport/2008/jc1511_gr08_executivesummary_en.pdf.

- UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS: AIDS epidemic update. 2009 Retrieved from http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/jc1700_epi_update_2009_en.pdf. [PubMed]

- Wusu O, Isiugo-Abanihe U. Understanding sexual negotiation between marital partners: A study of Ogu families in Southwestern Nigeria. African Population Studies. 2008;23(2):155–171. [Google Scholar]