Abstract

One of the fundamental challenges facing the cell is to accurately copy its genetic material to daughter cells. When this process goes awry, genomic instability ensues in which genetic alterations ranging from nucleotide changes to chromosomal translocations and aneuploidy occur. Organisms have developed multiple mechanisms that can be classified into two major classes to ensure the fidelity of DNA replication. The first class includes mechanisms that prevent premature initiation of DNA replication and ensure that the genome is fully replicated once and only once during each division cycle. These include cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)-dependent mechanisms and CDK-independent mechanisms. Although CDK-dependent mechanisms are largely conserved in eukaryotes, higher eukaryotes have evolved additional mechanisms that seem to play a larger role in preventing aberrant DNA replication and genome instability. The second class ensures that cells are able to respond to various cues that continuously threaten the integrity of the genome by initiating DNA-damage-dependent “checkpoints” and coordinating DNA damage repair mechanisms. Defects in the ability to safeguard against aberrant DNA replication and to respond to DNA damage contribute to genomic instability and the development of human malignancy. In this article, we summarize our current knowledge of how genomic instability arises, with a particular emphasis on how the DNA replication process can give rise to such instability.

Cells must replicate their genomes only once during each division cycle, and must respond to cues that threaten genomic integrity. When these mechanisms go awry, genomic instability may arise and lead to cancer.

In eukaryotes, DNA replication initiates from hundreds of thousands of replication sites, termed origins of DNA replication (Leonard and Méchali 2013). Not only do cells need to initiate and terminate DNA replication at the right time during S phase, they must do so only once, at each of these replication origins, during each division cycle (Machida et al. 2005). Mechanisms that govern the initiation of DNA replication in eukaryotes are described in full detail in Bell and Kaguni (2013) and Tanaka and Araki (2013), whereas those that regulate DNA replication are described in Siddiqui et al. (2013) and Zielke et al. (2013). Rhind and Gilbert’s (2013) work is dedicated to the mechanisms that control the timing of DNA replication. Here we focus on the mechanisms that prevent aberrant DNA replication.

Perturbations in DNA replication present cells with significant challenges. On one hand, incomplete genome duplication leads to cell inviability or, if cells survive, to aneuploidy. On the other hand, failure to restrict origin firing to once per replication origin per cell cycle, leads to overreplication. Reinitiation of DNA replication from the same origins of replication before the completion of S phase, commonly referred to as rereplication, is often associated with genome instability owing to the accumulation of replication intermediates, collapsed replication forks, and chromosomal breakages. In addition, defects in cytokinesis or mitotic regulation may lead to the complete reduplication of the genome. This latter process is reminiscent of endoreduplication, a physiological process that occurs in many metazoans during normal development and is characterized by multiple, discrete, and complete rounds of S phases without intervening mitosis. Finally, reinitiation of DNA replication from specific genomic loci is thought to be responsible for gene amplifications but the mechanisms underlying gene amplification are poorly understood.

How do these various mechanisms of genomic instability relate to cancer? An increase of copy number of chromosomes or genes allows cells to overexpress certain genes or mutate the extra copies to acquire growth, survival, or metastasis advantage. Equally important is the excessive DNA damage that is associated with these problems in DNA replication. When a cell attempts to segregate an underreplicated chromosome between two daughter cells, the result is often broken chromosomes and aneuploidy. Conversely, overreplication is marked by excessive DNA damage from collapsed replication forks. The repair processes are not perfect and so any increase in DNA damage leads to increased mutagenesis, and thus activation of oncogenes or inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, fueling malignant transformation and progression.

MECHANISMS PREVENTING REREPLICATION (ANTIREREPLICATION MECHANISMS)

The mechanisms that restrict DNA replication to one round per cell division were first elucidated in yeasts, both Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. The simpler genomes, faster replication cycles, significant biochemical and genetic information, and facile experimental tools of the yeasts have significantly enriched our understanding of the network that maintains the fidelity and robustness of DNA replication. Subsequent work in more complex organisms has shown that many of the principles connecting replication regulation with genomic instability are largely conserved. Higher eukarotyes, however, have adapted additional mechanisms to safeguard against genomic instability.

Although the antirereplication mechanisms vary slightly from organism to organism, they are dependent on a common principle: the temporal and spatial uncoupling of the two steps involved in DNA replication, the licensing of origin of replication, and the initiation of DNA replication or the “firing” of replication origins (Machida et al. 2005; Zhu et al. 2005; Arias and Walter 2007; Hook et al. 2007). These mechanisms ensure that prereplication complexes (pre-RCs) are assembled immediately after the completion of mitosis until the G1/S transition is reached and are prevented from assembling again until the completion of the next mitotic cycle (Fig. 1).

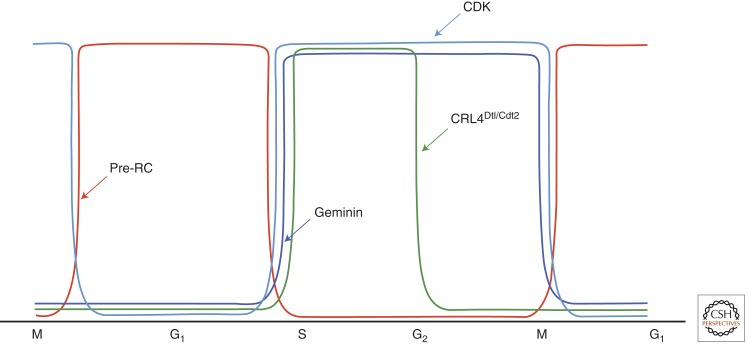

Figure 1.

Cell-cycle-dependent regulation of prereplication complex (pre-RC). Pre-RCs are established immediately following exit from mitosis and are prevented from being assembled again from the G1/S transition until exit from the next mitotic cycle. This regulation is dependent primarily on CDK, which is maintained at low levels early in G1, but peaks to high levels at the G1/S, during S, G2, and M phases. Low CDK activity during G1 results from the APCCdc20-dependent proteolysis of M-phase cyclins and the accumulation of CDK inhibitors. High CDK activity, mediated by S-, G2-, or M-type cyclin, suppresses pre-RC through inactivation of multiple pre-RC components. In higher eukaryotes, pre-RC formation in S and G2/M is further inhibited by geminin, a specific inhibitor of the replication-licensing factor Cdt1, as well as by an S-phase-specific ubiquitin ligase, CRL4Dtl/Cdt2, which promotes the proteolysis of chromatin-bound Cdt1 and Set8.

Inhibition of Pre-RC Assembly—A Universal Antirereplication Mechanism

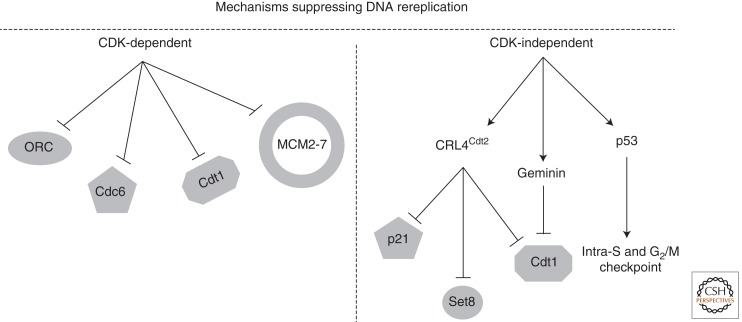

During the G1 phase of the cell cycle, transacting replication initiation factors recognize origins of replication and assemble prereplication complexes (pre-RCs) (Bell and Kaguni 2013; Tanaka and Araki 2013), which remain dormant until cells enter the S phase. Multiple mechanisms ensure that DNA is replicated once from each replication origin in a given cell cycle (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Multiple mechanisms suppress DNA rereplication. In all eukaryotic organisms, CDK activity, in S, G2, and M phases of the cell cycle, inhibits rereplication by inactivating multiple components of the prereplication complex (pre-RC) to prevent reinitatiation of DNA replication. CDK directly phosphorylates origin recognition complex (ORC) proteins, Cdc6, Cdt1, as well as various subunits of the replicative helicase MCM2-7, resulting either in their targeted proteolysis or cytoplasmic sequestration and hence their inactivation (see text for details). Higher eukaryotes evolved additional CDK-independent mechanisms to suppress DNA rereplication in the more complex genomes. These include a specialized E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, CRL4Dtl/Cdt2, which promotes the destruction of PCNA- and chromatin-bound Cdt1, Set8, and p21 during S phase of the cell cycle as well as in response to DNA damage. In addition, geminin, which is expressed in S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, binds to and inhibits Cdt1 to prevent pre-RC assembly. The tumor suppressor p53 provides an additional barrier to DNA rereplication or to cell survival after rereplication, presumably owing to inhibition of S and G2/M CDK kinase through the transcriptional up-regulation of p21, the induction of intra-S and G2/M cell-cycle arrest, and the induction of apoptosis.

Dbf4-Dependent Kinase—Master Initiator of DNA Replication

Two cell-cycle-regulated kinases, the Cdc7-Dbf4 kinase (also known as Dbf4-dependent kinase [DDK]) and the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK), ensure that the assembly of pre-RC does not occur outside of G1 (Labib 2010). DDK plays an important role in the initiation of DNA replication from individual replication origins. How DDK regulates origin firing and prevents new pre-RC assembly is not entirely clear. However, its ability to promote the phosphorylation of multiple components of the preinitiation complex may account for this activity. Early studies in yeast showed that DDK interacts with, phosphorylates, and activates the minichromosome maintenance subunit 2 protein (MCM2) of the MCM2-7 replicative helicase. The activation is significantly enhanced when MCM2 is prephosphorylated by CDK, suggesting that these two kinases work in concert to initiate DNA replication from individual origins (Lei et al. 1997; Masai et al. 2000). Subsequent studies, however, suggest that the S. cerevisiae MCM4 and MCM6 are the only targets of DDK essential for the recruitment to replication origins of GINS and Cdc45, two proteins required to activate the MCM2-7 helicase (Randell et al. 2010). It remains unclear, however, how the phosphorylation of MCM2-7 affects the recruitment of GINS and Cdc45, although it has been suggested that phosphorylation of MCM2-7 by DDK may alleviate some inhibitory activity in MCM4 (Sheu and Stillman 2010).

Additionally, in vitro and in vivo studies in S. cerevisiae revealed another cooperative activity of DDK and CDK, whereby DDK drives the initial recruitment of Sld3 and Cdc45, followed by CDK-dependent recruitment of GINS and the rest of the replisome to replication origins (Heller et al. 2011).

In response to DNA damage, such as that induced by hydroxyurea, the budding yeast Dbf4 (or its homolog in fission yeast, Dfp1/Him1) is hyperphosphorylated and inactivated through a Rad53-dependent mechanism triggering intra-S-phase checkpoint (Brown and Kelly 1999; Weinreich and Stillman 1999).

The DDK function in regulating origin firing and the DNA damage response is conserved in higher eukaryotes. For example, both DDK and CDK are required for the formation of the Cdc45-Mcm2-7-GINS (CMG) complex and the activation of the replicative helicase at replication origins in Drosophila melanogaster (Ilves et al. 2010). The cooperative activation of DNA replication by DDK and CDK is also observed in Xenopus laevis, and here, DDK-mediated phosphorylation of MCM2 precedes that of CDK (Nougarede et al. 2000; Walter 2000). Additionally, and similar to yeast, the activation of the ATR pathway in X. laevis by single-stranded gaps generated in response to DNA damage impedes DDK association, thus inactivating the enzyme and resulting in the suppression of replication origins (Costanzo and Gautier 2003; Costanzo et al. 2003). In human cells, too, replication arrest with hydroxyurea is effected through checkpoint pathways that block the firing of origins of replication just before Cdc45 recruitment (Karnani and Dutta 2011). This is the very same step that is dependent on DDK and local CDK function. Thus, DDK seems to be a major target of inactivation in the cell’s response to DNA damage to suppress origin firing. Whether DDK plays additional roles in restricting origin firing during normal S phase or in preventing refiring of replication origins in the same division cycle, remains to be determined.

CDK—Master Regulator of DNA Replication Initiation

The activity of CDK, the second enzyme regulating pre-RC assembly and the initiation of DNA replication, is under the regulation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase APCCdc20, which destroys the M-phase cyclin and thus maintains low CDK activity during G1 (Fig. 1). CDK activity in various organisms is further inhibited in G1 by a number of CDK inhibitors, such as Sic1 (an inhibitor of Clb-5/6-Cdk1/Cdc28 in S. cerevisiae) and Cdkn1a/p21/cip1 and Cdkn1b/p27/kip1 (inhibitors of cyclin E/A-Cdk2 in mammalian cells). At the G1/S transition, in S, G2, and M phases, cyclins reaccumulate and CDK inhibitors are degraded via ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis, resulting in high CDK activity (Zhu et al. 2005; Arias and Walter 2007; Hook et al. 2007).

In S, G2, and M phases, CDK inhibits pre-RC by phosphorylating and inactivating multiple components of pre-RC (Fig. 2). In S. cerevisiae, high CDK activity in G2/M suppresses pre-RC assembly (Dahmann et al. 1995; Tanaka et al. 1997; Tanaka and Araki 2010). Consequently, inactivation of G2-CDK leads to rereplication, both in S. cerevisiae, and S. pombe (Correa-Bordes and Nurse 1995; Jallepalli and Kelly 1996; Noton and Diffley 2000). On the other hand, precocious activation of CDK in G1, owing to overexpression of Clb2 or deletion of Sic1, inhibits pre-RC formation, results in fewer origin firing, prolongs S phase, and induces gross chromosomal rearrangement (Detweiler and Li 1998; Lengronne and Schwob 2002).

Origin Recognition Complex Proteins

The S. cerevisiae Cdc28 phosphorylates and inactivates Orc2 and Orc6 subunits of the origin recognition complex (ORC) (Nguyen et al. 2001). After DNA replication is initiated, the S-phase cyclin Clb5 binds Orc6 through a Cy motif and inhibits the assembly of new pre-RCs (Wilmes et al. 2004). Importantly, eliminating the Orc6 Cy motif results in rereplication, demonstrating the functional significance of cyclin-CDK-dependent inactivation of ORC proteins to prevent genomic instability (Wilmes et al. 2004).

In S. pombe, Cdk1/Cdc2, in complex with the mitotic cyclin Cdc13 (Cdc2-Cdc13), binds and phosphorylates Orp2 (the Orc2 homolog in fission yeast) at replication origins as cells enter S phase and prevents pre-RC assembly (Vas et al. 2001; Wuarin et al. 2002). Because Cdc13 does not function in S phase, the disruption of Cdc2-Cdc13 binding to Orp2 leads to endoreduplication rather than rereplication (Wuarin et al. 2002). This conclusion is consistent with the finding that mutations in Cdc13, the transient inhibition of Cdc13, or the overexpression of the Cdc2-Cdc13 inhibitor Rum1 causes endoreduplication (Correa-Bordes and Nurse 1995).

Inactivation of cyclin A-CDK in Drosophila Schneider D2 (SD2) cells, unlike the case in yeast, results in a complete duplication of the genome with 8N DNA content (Mihaylov et al. 2002). In Xenopus egg extract, cyclin A-CDK promotes the release of ORC proteins (along with Cdc6 and MCM) from chromatin and prevents pre-RC assembly (Findeisen et al. 1999). Orc1 is also selectively released from chromatin in mammalian cells in the S to M phase of the cell cycle where it is polyubiquitylated via the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase before its proteolysis by the 26S proteasome (Fujita et al. 2002; Li and DePamphilis 2002; Mendez et al. 2002). Although mammalian Orc1 is also phosphorylated by cyclin A-CDK, it is unclear whether this phosphorylation targets the protein for proteolysis. However, CDK-mediated phosphorylation of mammalian Orc1 in mitosis prevents its association with chromatin and blocks pre-RC assembly (Li et al. 2004). Mammalian Orc2, on the other hand, is phosphorylated by the polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) and this has been shown to promote DNA replication and is required to maintain functional pre-RC complexes under DNA replication stress (Song et al. 2011). A more recent study shows, however, that human CDK phosphorylates Orc2 on threonine 116 and threonine 226 during S and G2 phases of the cell cycle leading to the dissociation of ORC2-5 from chromatin and replication origins, suggesting that CDK-mediated phosphorylation of Orc2 may inhibit ORC binding to newly replicated DNA (Lee et al. 2012).

Cdc6/Cdc18 and Cdc10-Dependent Transcript 1 (Cdt1)

The licensing activity of the replication initiation factor Cdc6 is also under the control of CDK. This is best illustrated in S. cerevisiae, in which Clb-Cdc28 controls Cdc6 activity through multiple mechanisms. First, Cdc28-dependent phosphorylation, and the consequent cytoplasmic sequestration of the transcriptional coactivator Swi5, inhibits Cdc6 transcription (Moll et al. 1991). Second, Clb-Cdc28 directly phosphorylates Cdc6 and promotes its proteolysis via the SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase (Drury et al. 1997, 2000; Elsasser et al. 1999). Third, the stable association of Cdc6 with Clb2-Cdc28 upon phosphorylation of its amino-terminal CDK phosphorylation sites blocks its licensing activity (Mimura et al. 2004). In fission yeast, Cdc2 similarly phosphorylates the Cdc6 ortholog Cdc18 in S phase and promotes its destruction via the E3 ubiquitin ligase SCFPop1 (Jallepalli et al. 1997; Kominami and Toda 1997). Significantly, ectopic expression of mutant Cdc18 lacking CDK phosphorylation sites results in significant rereplication. However, when Cdc18 mutant is expressed from its natural promoter, rereplication does not occur unless Cdt1 (Cdc10-dependent transcript 1) is coexpressed in these cells, suggesting that the simultaneous inactivation of Cdc18 and Cdt1 via CDK is required to suppress rereplication (Jallepalli et al. 1997; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2001). In higher eukaryotes, and as cells enter S phase, cyclin A-Cdk2 interacts with and phosphorylates Cdc6 leading to its cytoplasmic translocation and hence its inactivation (Saha et al. 1998; Jiang et al. 1999; Petersen et al. 1999; Delmolino et al. 2001).

CDK may also suppress rereplication by inactivating Cdt1. Cdt1 is phosphorylated by CDK in late G1 and at the G1/S transition and this results either in its exclusion from the nucleus, as is the case in budding yeast (Tanaka and Diffley 2002), or its destruction by the proteasome upon its ubiquitylation via the cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase 1 with the substrate-specific adaptor Skp2 (CRL1Skp2; also known as SCFSkp2) or via the cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases 4A/B with the substrate-specific adaptor Dtl/Cdt2 (CRL4Dtl/Cdt2) as seen in fission yeast and metazoans (Nishitani et al. 2001; Li et al. 2003; Hu et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2004; Thomer et al. 2004; Arias and Walter 2006; Hu and Xiong 2006; Jin et al. 2006; Nishitani et al. 2006; Senga et al. 2006; Kim and Kipreos 2007; Guarino et al. 2011). Consistent with a significant role for CDK-mediated inactivation of Cdt1, mutations in the CDK phosphorylation sites in Drosophila Cdt1 (Dup) is sufficient to induce rereplication (Thomer et al. 2004).

Minichromosome Maintenance Proteins (MCM2-7)

The MCM2-7 replicative helicase is another target of inactivation by CDK. In S. cereviseae, Cdc28 phosphorylates various components of the MCM2-7 complex during G2 and M and promotes its cytoplasmic translocation (Labib et al. 1999; Pasion and Forsburg 1999; Nguyen et al. 2000). However, in S. pombe and higher eukaryotes, the phosphorylation of MCM2-7 by CDK does not induce its cytoplasmic translocation but instead inhibits its chromatin binding (Kimura et al. 1994; Todorov et al. 1995; Coue et al. 1996; Pereverzeva et al. 2000; Lei and Tye 2001). An elegant study in yeast, however, showed that rereplication was not observed unless the inhibitory effect of CDK on ORC, CDC6, and MCM were simultaneously annulled (Nguyen et al. 2001). Annulling only one of the pathways resulted in weak rereplication, unlike that which was observed on the simultaneous inactivation of Cdc6 and Cdt1 described above. These findings show that inactivation of MCM by CDK is only one of several mechanisms that guard against rereplication.

Although inactivating MCM proteins by CDK is well established in yeast, there is little evidence in support for extensive direct regulation in mammalian cells. In vivo studies showed that cyclin B-Cdk1/Cdc2 phosphorylates MCM2 and MCM4 in human HeLa cells, and that inactivation of Cdc2 in the temperature-sensitive mutant murine FT210 cells resulted in sever impairment, both of G2-associated MCM2/4 hyperphosphorylation and the release of the MCMs from chromatin (Fujita et al. 1998). On the other hand, in vitro studies showed that cyclin A-Cdk2 can phosphorylate multiple serine and threonine residues in the amino terminus of mouse MCM4 leading to inhibition of the Mcm4,6,7 subcomplex helicase activity (Ishimi et al. 2000; Ishimi and Komamura-Kohno 2001).

In addition to these pre-RC components, CDK also promotes DNA replication via phosphorylating additional proteins important for replication initiation. For example, Cdc28 phosphorylates Sld2 and Sld3 in S phase, an activity that is required for DNA replication in S. cereviseae (Tanaka et al. 2007; Zegerman and Diffley 2007). Phosphorylation of Sld2 and Sld3 by Cdc28 is essential for the formation of the Sld2/Sld3/Dpb11 complex and the recruitment of the GINS complex to replication origins (Labib 2010). Furthermore, in vitro studies show that Cdc28, via phosphorylating Sld2, also stimulates the formation of an unstable DNA-independent complex between Sld2, Dpb11, DNA polymerase epsilon (Pol ε), and GINS (also known as the preloading complex [pre-LC]), which is required for replication initiation (Muramatsu et al. 2010). Whether CDK-mediated phosphorylation of these proteins prevents rereplication remains unclear.

CRL4dtl/Cdt2, GEMININ, AND P53—CDK-INDEPENDENT SUPPRESSORS OF REREPLICATION AND GENOME INSTABILITY

Recent studies uncovered additional and CDK-independent mechanisms to prevent rereplication (Fig. 2). In mammalian cells, inactivation of the CDK-dependent proteolysis of Cdt1 via SCFSkp2 does not lead to rereplication, presumably because Cdt1 is still degraded via the CRL4Dtl/Cdt2 pathway (Takeda et al. 2005). CRL4Dtl/Cdt2 promotes the degradation of chromatin-bound Cdt1, both in S phase and after DNA damage, in a reaction that is dependent on its ability to bind PCNA through a specialized PCNA-interacting peptide (PIP-box) located in the amino terminus of Cdt1 (Arias and Walter 2006; Hu and Xiong 2006; Jin et al. 2006; Nishitani et al. 2006; Senga et al. 2006; Kim and Kipreos 2007; Guarino et al. 2011). Interestingly, inactivation of the CRL4Dtl/Cdt2-dependent degradation of Cdt1 leads to rereplication in human cells and in zebrafish (Jin et al. 2006; Sansam et al. 2006). This important finding shows that (a) chromatin-bound Cdt1 is resistant to CDK-mediated phosphorylation and/or SCFSkp2-mediated ubiquitylation and degradation, (b) Cdt1-PCNA interaction is not required for Cdt1 to promote DNA replication, and (c) chromatin- and PCNA-bound Cdt1 may be refractory to inhibition by geminin (see below).

CRL4Dtl/Cdt2 may prevent rereplication via additional mechanisms. For example, CRL4Dtl/Cdt2 promotes the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of the histone H4 lysine 20 (H4K20) monomethyl transferase SETD8/Pr-Set7/Set8 at the G1/S and during S phase, and that inactivation of this pathway results in significant rereplication (Abbas et al. 2010; Tardat et al. 2010). CRL4Dtl/Cdt2-insensitive but catalytically active mutant of Set8 is sufficient to nucleate DNA rereplication when tethered to specific genomic loci perhaps by preventing the assembly of pre-RC on chromatin (Tardat et al. 2010). Whether Set8 promotes rereplication through H4K20 methylation or through a yet-to-be-determined mechanism remains unclear. Also unclear is the relative contribution of Set8 and Cdt1 in promoting rereplication on CRL4Dtl/Cdt2 inactivation.

Higher eukaryotes have evolved an additional mechanism to repress Cdt1 through its inactivation by geminin. Geminin was initially discovered in a screen for proteins degraded by the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) in mitosis and was found to inhibit DNA replication (McGarry and Kirschner 1998). Subsequent studies showed that geminin inhibits DNA replication through its ability to associate with and inhibit Cdt1 (Wohlschlegel et al. 2000; Tada et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2004; Saxena et al. 2004). Importantly, geminin depletion by small interfering RNA (siRNA) results in Cdt1-dependent rereplication, both in human and Drosophila cells (McGarry 2002; Mihaylov et al. 2002; Ballabeni et al. 2004; Melixetian et al. 2004; Zhu et al. 2004).

In human tumor-derived cells deficient of the tumor suppressor protein Tp53/p53, the mere overexpression of Cdt1 results in modest rereplication, which is significantly enhanced by the coexpression of Cdc6 (Vaziri et al. 2003). This Cdt1+Cdc6-induced rereplication, however, was not observed in tumor cells with wild-type p53 or in primary untransformed cells. Inactivation of p53 renders cells susceptible to Cdt1+Cdc6-induced rereplication, demonstrating a critical function for p53 as a suppressor of rereplication (Vaziri et al. 2003). p53 was not actively suppressing rereplication but was modulating the cell’s response to rereplication such that extensive rereplication is not seen.

Cdt1+Cdc6-induced rereplication, or rereplication induced by the depletion of geminin results in the activation of ATM and ATR and their downstream effectors and checkpoint kinases Chk2 and Chk1, respectively, which phosphorylate and activate p53 (Vaziri et al. 2003; Zhu et al. 2004; Lin and Dutta 2007). The activation of p53 leads to activation of p21 and a senescent response or leads to activation of proapoptotic genes and apoptosis (Vaziri et al. 2003; Zhu et al. 2004; Lin and Dutta 2007; Lin et al. 2010). Thus, the presence of p53 made the cells die in the presence of small amounts of rereplication so that it was difficult to detect cells with >G2 DNA content.

Intriguingly, there are additional checkpoint pathways activated by rereplication upon CRL4Dtl/Cdt2 inactivation or geminin depletion. In these instances, the ATR-Chk1-Cdc25C pathway is more active, leading to a G2 block in which cells cannot enter mitosis but can still rereplicate their DNA. The difference between G2 block with rereplication versus p53 activation and apoptosis may be dictated by the nature of rereplication or the accumulated replication intermediates induced under the various conditions, and consequently, the type of DNA damage generated (Vaziri et al. 2003; Zhu et al. 2004; Lin and Dutta 2007).

Geminin depletion allows rereplication in some human-derived cancer cells (e.g., HCT116 colon cancer cells), but not others (e.g., HeLa cervical cancer cells). The difference can be explained by the greater efficiency of the CDK-dependent pathway inhibiting rereplication in the HeLa cells. In such cells, the simultaneous inactivation of geminin and cyclin A-Cdk2, as, for example, by the depletion of Emi1 and premature activation of the APC, is sufficient to induce rereplication (Machida and Dutta 2007). Thus, although there are multiple pathways to inhibit rereplication, the relative importance of the different pathways appears to vary between cancer cell lines.

IS REREPLICATION A MAJOR DRIVER OF CANCER?

The increase in gene copy number that results from rereplication could sow the seeds of gene amplification, a major driving force in cancer. Indeed, careful perturbation of the pathways that prevent rereplication in S. cerevisiae, such that the rereplication is minimal and does not lead to cell death, can lead to gene amplification (Green et al. 2010). Therefore, theoretically it is possible that minor islands of rereplication lead to the gene amplification seen in human cancers. In practice, however, this has been difficult to show experimentally, mostly because all experimental approaches to induce rereplication in human cells inevitably produces extensive DNA damage and leads to cell death. In addition, mutations in the genes that prevent rereplication, aside from TP53/p53, have not yet been identified in cancers, although it is possible that transient epigenetic suppression of these genes is just sufficient to induce the local islands of rereplication that result in islands of stalled replication forks and DNA breaks, which lead to gene amplification, translocations, deletions, and other forms of cancer-promoting genome instability.

INDUCERS OF REREPLICATION: NOVEL CLASS OF ANTICANCER AGENTS

In contrast to the possibility that rereplication leads to cancer formation, the cytotoxicity that results from the induction of rereplication in human-derived cancer cells has surprisingly yielded a novel anticancer activity. Rereplication is invariably associated with spontaneous DNA damage and the activation of ATM/ATR-dependent intra-S-phase and G2/M checkpoints. Bypassing rereplication-induced checkpoints leads to significant apoptosis or senescence (Melixetian et al. 2004; Zhu et al. 2004; Zhu and Dutta 2006; Machida and Dutta 2007). These findings suggest that inducing rereplication may be an effective strategy to inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells. This idea proved to be correct with the accidental discovery that a newly described drug, MLN4924, induces significant rereplication as well as apoptosis in a large number of human-derived cancer cell types and inhibited the growth of human tumor xenografts in mice (Soucy et al. 2009). MLN4924 was developed as a potent and specific inhibitor of the NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE), an essential enzyme that controls the NEDD8 conjugation, which controls the activity of the cullin-RING subclass of E3 ubiquitin ligases including CRL4 and CRL1 ubiquitin ligases (Soucy et al. 2009). Rereplication and apoptosis induced in these cells correlated with the stabilization of Cdt1 and the induction of p21 owing to the inhibition of CRL4Dtl/Cdt2 and CRL1Skp2 ligases, and is accompanied by the induction of p21-dependent senescence (Lin et al. 2010; Jia et al. 2011). Interestingly, rereplication seems to selectively induce apoptosis in human cancer cells, but not in primary human-derived noncancer cells or cells immortalized by the SV40 large tumor antigen (Zhu and Depamphilis 2009). A recent study, using an image-based high-throughput screening for agents that induce rereplication, showed that two additional small bioactive agents are capable of inducing rereplication only in cancer cells, although the target of these molecules is yet to be determined (Zhu et al. 2011). These findings show that additional mechanisms exist in normal cells that safeguard against rereplication and that cancer cells may be selectively susceptible to the cytotoxic effects of rereplication-inducing agents.

DNA DAMAGE AND DNA REPLICATION

In addition to the mechanisms that operate during normal DNA replication, multiple mechanisms ensure that the genome is protected against various forms of DNA damage. Genomes are constantly experiencing DNA damage induced by normal metabolic by-products and by exogenous sources such as UV, ionizing radiation (IR), and chemical agents. DNA lesions act as roadblocks to DNA replication forks generating a precarious situation for the cell. If the fork is unable to bypass the lesion and restart replication, the cell must rely on an incoming replication fork from the opposite side to finish replication of the replicon. This may be particularly tricky in genomic regions with a paucity of replication origins that have a propensity for fork stalling or for forks that replicate at the end of S phase (Durkin and Glover 2007; Letessier et al. 2011). Such fork stalling lesions include bulky adducts from UV or chemical-induced damage, interstrand cross-links (ICLs), and intercalating drugs that distort the double helix. In addition, replication forks can stall owing to depletion of nucleotide pools, unusual DNA structures, and head-on collisions with transcription machinery (Branzei and Foiani 2010). Dissociation of the replication machinery at a stalled fork results in collapse and the generation of a one-ended double-strand break (DSB). Replication-induced DSBs can also result when a replication fork encounters a covalently linked topoisomerase (Topo I or II) that is generated by topoisomerase inhibitors that prevent religation of Topo-cleaved DNA (Liu et al. 2000; Deweese and Osheroff 2009).

Cellular Responses to DNA Damage

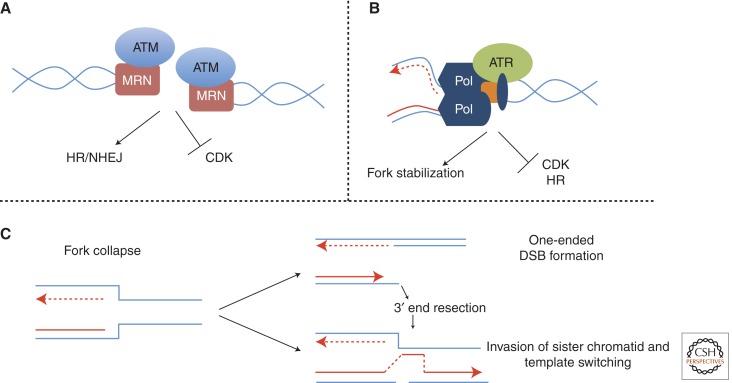

DSBs are highly detrimental to the cell and if left unrepaired, result in chromosomal rearrangements, deletions, and chromosomal loss. Thus, the cell has developed two parallel DNA damage response (DDR) pathways to respond to DSBs or stalled replication pathways mediated by the checkpoint kinases ATM or ATR, respectively (Fig. 3). Although ATM and ATR participate in parallel pathways that respond to different types of DNA damage, there is significant cross talk between the two pathways and the kinases converge on similar targets. For example, processing of DSBs produces single-stranded DNA that can activate ATR, whereas prolonged replication stress will result in DSB formation that subsequently activates ATM. Defects in the DDR result in unrepaired damage, which along with inaccurate DNA repair can lead to chromosomal alterations, a common cause of genomic instability and carcinogenesis.

Figure 3.

Model depicting cellular response to double-strand breaks (DSBs) and stalled replication forks. (A) Response to DSB: Mre11, Rad50, and Nbs1 complex (MRN) recognize DSBs and recruit ATM to the site where ATM signaling mediates repair by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR) while also inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity. (B) Response to stalled replication forks: Stalling of the replication machinery recruits ATR whose activity is required to prevent dissociation of the DNA polymerase complex. In addition, precocious HR is prevented and CDK activity at late firing replication origins is inhibited. (C) Dissociation of the replication machinery results in a collapsed fork. This may lead to a one-ended DSB, which can invade a sister chromatid to initiate replication restart.

Activation of the checkpoint in response to DSBs begins with binding of Mrell, Rad50, and Nbs1, the MRN complex, to the ends of the DSB where it recruits and subsequently activates the ATM kinase. ATM phosphorylates the histone variant H2AX initiating a signaling cascade involving phosphorylation and ubiquitylation to recruit a number of DDR and repair proteins to the site of the break. ATM also phosphorylates and activates the checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2), which induces a G2/M delay by sequestering Cdc25C in the cytoplasm, thus inhibiting M-phase CDK. ATM and Chk2 may also phosphorylate and activate p53 to induce prolonged cell-cycle arrest in G1 or cell death by apoptosis in response to excessive DNA damage that overwhelms the repair pathways.

DNA damage during S phase results in replication fork stalling. This activates an ATR-dependent checkpoint to coordinate DNA repair and maintain DNA replication (Paulsen and Cimprich 2007; Nam and Cortez 2011). Uncoupling of the replicative helicase from DNA synthesis generates tracks of single-stranded DNA coated with RPA protein, which recruits ATR via its binding partner ATRIP. Rad17- and Rfc-mediated loading of the 911 complex (Rad9-Hus1-Rad1 trimeric clamp), together with TopBP1, activates ATR, which is required to recruit repair proteins and stabilize the replication fork to allow replication to restart once the block has been resolved. Maintaining the replication machinery at the fork prevents generation of DSBs. Additional clusters of replication origins in the vicinity of the stalled fork fire in order to complete replication. Late-replicating origins, however, are inhibited by ATR and its substrate and checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1) (Debatisse et al. 2006; Ge and Blow 2010; Karnani and Dutta 2011). Chk1 (and Chk2) phosphorylates Cdc25A on multiple serine residues resulting in its proteolytic degradation via the SCFbeta-TRCP pathway (Falck et al. 2001; Zhao et al. 2002; Busino et al. 2003; Hassepass et al. 2003). Chk1 additionally phosphorylates Cdc25A on serine 178 and threonine 507, thereby facilitating its binding to 14-3-3 and inhibiting its binding to cyclin B-Cdk1 (Chen et al. 2003). Cdc25A degradation/inhibition in response to DNA damage inactivates CDK2 and enforces intra-S-phase cell-cycle arrest critical for the repair of DNA damage before the resumption of DNA synthesis. Defective Chk1/Chk2-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of Cdc25A leads to radio-resistant DNA synthesis and genome instability.

Both ATR and Chk1 are essential genes required during normal S phase, presumably because they are necessary to deal with endogenous replication stress such as troublesome secondary structures in the DNA or encounters with convergent transcription. This is evident from the ATR-mediated phosphorylation of H2AX at replication factories in unperturbed cells.

DSB Repair

Repair of DSBs is facilitated by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). During NHEJ, Ku proteins bind to and protect the ends of the DSB and recruit the DNA-PK catalytic subunit to form the heterotrimeric DNA-PK holoenzyme. DNA-PK activity is required to process nonligatable ends before ligation by LigIV-Xrcc4 complex. In addition to the possibility of joining two unrelated DSB ends, this process involves the addition or removal of nucleotides at DSB ends and thus NHEJ is considered error prone. In contrast, HR uses sequence homology of a sister chromatid to regenerate the broken chromosome. During HR, the MRN complex recognizes the DSB leading to resection of the 5′ ends and generation of 3′ overhanging single-stranded DNA coated with RPA protein. RPA is exchanged for Rad51, which mediates strand invasion of the 3′ overhang into the undamaged sister chromatid searching for sequence homology. On establishment of sequence homology, the opposite strand of the sister chromatid is displaced and DNA polymerase extends the invading end using the sister chromatid as a template. A Holliday junction is formed and depending on how it is resolved, HR results either in crossover events (common during meiosis) in which chromosomal information is exchanged or noncrossover events (preferred during repair of DSBs). In the event the DSB occurs within a repetitive element, HR could occur between different chromosomes or within the same chromosome resulting in translocations, duplications, or deletions of genomic sequences.

Both NHEJ and HR compete with each other and it is still poorly understood what dictates which pathway is used. Cdk2 activity and S-phase-specific DNA repair pathways appear to promote HR. NHEJ operates primarily during G1 phase (although it is active throughout the cell cycle) and defects in NHEJ result in sensitivity to DSB-inducing agents. HR on the other hand is used during S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when a sister chromatid is readily available and defective HR results in increased genomic instability and cancer predisposition (Kee and D’Andrea 2010).

Rescuing Stalled Replication Forks

Decoupling of the replicative helicase when polymerases stall generates tracks of single-stranded DNA that can promote undesired recombination events. Evidence suggests that ATR inhibits recombination at stabilized replication forks. However, once a fork has collapsed, HR is required to restart replication. Several models of replication restart for stalled or collapsed replication forks have been proposed, which include fork remodeling, template switching, and break-induced replication (Fig. 3). Fork remodeling requires nonreplicative helicases, such as Blm and Wrn, which have Holliday junction migration as well as DNA-annealing activities (Petermann and Helleday 2010). Template switching is invoked when the replication fork encounters slowed replication owing to difficult secondary structures or stalling induced by a DNA lesion. A Holliday junction can form in which one strand has invaded and replicated on the undamaged sister chromatid before switching back to the original template. On encountering a single-strand break, melting of the DNA strands during replication results in a DSB with only one end, which invokes break-induced replication. This may also arise by endonucleolytic cleavage of a lesion by Mus81-Eme1 at a collapsed fork. To repair the break, the 5′ end is resected, allowing invasion of the 3′ end into a sister chromatid, and restart of replication. Cycles of this break-induced replication ensue with dissociation of the replicating strand and reinvasion until a proper replication fork has been reestablished or the replicon has been completely replicated. Template switching and break-induced replication are relatively error-free as strand invasion is based on significant homology. However, repetitive sequences and microhomology between neighboring replisomes introduce opportunities for replication errors resulting in chromosomal duplications, insertions/deletions, and inversions.

ICLs pose a more complicated problem and invoke multiple repair mechanisms coordinated by the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway (Kee and D’Andrea 2010). FA is a genetic disorder resulting in hypersensitivity to ICL-causing agents, genomic instability, and cancer. FA is caused by mutation in 13 different genes referred to as FANC genes. The FA pathway is dependent on the monoubiquitylation of FANCD2 and FANCI by the FA core complex. Recruitment and activation of the FA core complex at stalled forks requires ATR and the upstream FANCM protein, which recognizes damaged DNA during S phase. Monoubiquitylation of FANCD2-FANCI retains the heterodimer on chromatin where it coordinately regulates multiple repair processes via interactions with downstream proteins such as the endonuclease Fan1, Brca1, FAND1/Brca2, FANCJ/Bach1, and FANCN. Repair of ICLs is initiated by endonucleases (Xpf-Ercc1, Mus81-Eme1, or Fan1) “unhooking” the lesion from the Crick strand to generate a single-strand break on this strand that is soon converted to a DSB by replication. Translesion DNA synthesis (TLS) across the lesion on the Watson strand produces a double-stranded Watson chromatid on which nucleotide excision repair (NER) acts to repair the unhooked adduct. Finally, the DSB on the Crick chromatid can initiate HR by invading the repaired Watson chromatid to repair the DSB. In addition, FANCM recruits the Blm helicase and together they stabilize and remodel the replication fork to prevent deleterious recombination events. Although the FA pathway is most critical for repair of ICLs, the pathway is also activated in response to UV and replication-associated DSBs, as well as in response to rereplication (Zhu and Dutta 2006).

A number of genetic disorders characterized by genomic instability and cancer predisposition arise from mutations in DDR and HR proteins. These include FA, and ataxia telangiectasia, a genetic neurodegenerative disease that results from mutations in the ATM gene and is associated with extreme sensitivity to IR and predisposition to cancer. Mutation in Mre11 gives rise to similar disorders. Mutations in BLM, WRN, RECQ4, and RecQ family helicases involved in HR give rise to Bloom’s syndrome, Werner’s syndrome, and Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, respectively. Defects in Wrn and Recq4 result in decreased HR. Defects in Blm, in contrast, result in increased sister chromatid exchange and patients with Bloom’s syndrome have an increased risk of loss of heterozygosity at tumor suppressor loci.

Point Mutations and Microsatellite Instability

The major replicative polymerases Pol δ and Pol ε that synthesize lagging and leading strands, respectively, have high fidelity rates (one error per 104–105 nucleotides) owing to their proofreading 3′ exonuclease activity (McCulloch and Kunkel 2008). Thus, with 6 billion base pairs in human diploid cells 100,000–1,000,000 mutations may be introduced during every division cycle owing to mistakes that escape proofreading. An additional increase in error rate occurs from mutations of DNA polymerases and alterations in dNTP levels. The mismatch repair (MMR) pathway is crucial for suppressing spontaneous mutations from errors in proofreading by recognizing mismatched nucleotides as well as insertions and deletions that arise from replication slippage. MMR proteins (MutS and MutL homologs) remove mismatched nucleotides via endonuclease and helicase activities allowing for reparative DNA synthesis. Defects in MMR result in a 100- to 1000-fold increase in replication errors including point mutations and expansion or contraction of simple repetitive sequences (microsatellites) that are prone to replication slippage (Arana and Kunkel 2010).

DNA damage owing to oxidation, alkylation, and hydrolysis of nucleotide bases, results in altered base-pairing leading to transversion mutations. An approximate 20,000 such insults to the mammalian genome occur per day (Preston et al. 2010). Most of these lesions are repaired by base excision repair (BER), a process in which DNA glycosylases recognize and remove the damaged base generating an apurinic or apyrimidinic (AP) site. AP endonuclease cleaves the AP site generating a single-strand break that is repaired by DNA synthesis (typically by Pol β) followed by DNA ligation. Typically, bulky DNA adducts, such as UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and 6–4 photoproducts, cause distortions to the double helix that are recognized and repaired by the NER pathway. Similar to BER, a NER pathway uses endonuclease and helicase activities to excise a small segment of DNA containing the lesion followed by DNA synthesis using the undamaged strand as a template. NER globally surveys the genome as well as being coupled to transcription of active genes.

In the event that unrepaired DNA damage, such as a UV-induced lesions or AP sites, is encountered by a replication fork, replication stalls and TLS is activated to allow replication across the lesion. This pathway involves recruitment of the ubiquitin ligase Rad18 to the stalled fork where it monoubiquitylates PCNA. This allows loading of specialized TLS polymerases, such as Pol η, Pol ξ, and Rev1/Rev3 that are able to bypass the lesion (Kannouche et al. 2004; Watanabe et al. 2004). Intriguingly, CRL4Dtl/Cdt2 can also monoubiquitylate PCNA on the same residue that is modified by Rad18 (Terai et al. 2010), suggesting that there is some redundancy in the E3 ligase that initiates TLS. TLS polymerases lack proofreading ability and their fidelity rates differ greatly. Thus, TLS can be highly error prone depending on the type of lesion and the polymerase used (Hoffmann and Cazaux 2010). Deubiquitylation of PCNA by Usp1 or conversion of monoubiquitylation to polyubiquitylation prevents polymerase switching and repair of the lesion must rely on other mechanisms (Huang et al. 2006; Motegi et al. 2006; Unk et al. 2006).

Mutations that affect MMR, BER, and NER pathways also result in genomic instability and are associated with human cancer. For example, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (also known as Lynch syndrome) arises from defects in MMR genes, such as Msh2, and is characterized by microsatellite instability. Similarly, biallelic inactivating germline mutations in the BER gene MutYh, an adenine DNA glycosylase, predispose to recessively inherited adenomatous polyposis (MUTYH-associated polyposis [MAP]) and colon cancer. Defects in repairing UV-induced lesions result in extreme sensitivity to sunlight and development of skin cancer. This occurs in xeroderma pigmentosum patients who have mutations in the NER pathway or the TLS polymerase Pol η. Mutations in these DNA repair pathways have also been documented in sporadic cancers (Negrini et al. 2010), as has the overexpression of error-prone polymerases (Hoffmann and Cazaux 2010).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The last 20 years have witnessed significant advances in our understanding of the molecular events that are triggered by threats to the genome integrity. Key players have been identified and genetic and biochemical characterization of these genes and their encoded protein products now identify them as true “guardians of the genome.” Dysregulation of these genes leads to unstable genomes. Excessive genomic instability usually leads to cell death, a factor in the utility of MLN4924 as an anticancer agent. However, because of the many redundant pathways for preventing overreplication or for repair, it is rare for mutations (or epigenetic silencing) affecting single pathways to create so much genomic instability as to cause cell death. Instead, inactivation of these single pathways simply increases the mutation burden without provoking cell death. The resulting heterogeneity in the genes of daughter cells allows the appearance of cells with growth or survival advantages, the driving force for cancer development. The same heterogeneity lies behind the resistance of cancers to many types of therapy. Thus, a major objective of our field should be to exploit known anomalies of repair and replication control in cancers to determine which redundant repair pathways should be therapeutically inhibited to produce “synthetic lethality” in the cancer cells. This will convert the mutation-generating machinery in the cancer into an Achilles heel by pushing the malignant cells selectively into extensive genomic instability and cell death.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We apologize to authors whose primary work was not cited owing to space restrictions. Work in the authors’ laboratory is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (RO1CA60499 and GM084465). T.A. is supported by an NCI grant (RCA140774B). M.A.K. is supported by an NRSA from the NIH (5F32GM087843-03).

Footnotes

Editors: Stephen D. Bell, Marcel Méchali, and Melvin L. DePamphilis

Additional Perspectives on DNA Replication available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Abbas T, Shibata E, Park J, Jha S, Karnani N, Dutta A 2010. CRL4(Cdt2) regulates cell proliferation and histone gene expression by targeting PR-Set7/Set8 for degradation. Mol Cell 40: 9–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arana ME, Kunkel TA 2010. Mutator phenotypes due to DNA replication infidelity. Semin Cancer Biol 20: 304–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias EE, Walter JC 2006. PCNA functions as a molecular platform to trigger Cdt1 destruction and prevent re-replication. Nat Cell Biol 8: 84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias EE, Walter JC 2007. Strength in numbers: Preventing rereplication via multiple mechanisms in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev 21: 497–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballabeni A, Melixetian M, Zamponi R, Masiero L, Marinoni F, Helin K 2004. Human geminin promotes pre-RC formation and DNA replication by stabilizing CDT1 in mitosis. EMBO J 23: 3122–3132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bell SP, Kaguni JM 2013. Helicase loading at chromosomal origins of replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a010124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D, Foiani M 2010. Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 208–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Kelly TJ 1999. Cell cycle regulation of Dfp1, an activator of the Hsk1 protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 8443–8448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busino L, Donzelli M, Chiesa M, Guardavaccaro D, Ganoth D, Dorrello NV, Hershko A, Pagano M, Draetta GF 2003. Degradation of Cdc25A by β-TrCP during S phase and in response to DNA damage. Nature 426: 87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MS, Ryan CE, Piwnica-Worms H 2003. Chk1 kinase negatively regulates mitotic function of Cdc25A phosphatase through 14–3-3 binding. Mol Cell Biol 23: 7488–7497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Bordes J, Nurse P 1995. p25rum1 orders S phase and mitosis by acting as an inhibitor of the p34cdc2 mitotic kinase. Cell 83: 1001–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo V, Gautier J 2003. Single-strand DNA gaps trigger an ATR- and Cdc7-dependent checkpoint. Cell Cycle 2: 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo V, Shechter D, Lupardus PJ, Cimprich KA, Gottesman M, Gautier J 2003. An ATR- and Cdc7-dependent DNA damage checkpoint that inhibits initiation of DNA replication. Mol Cell 11: 203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coue M, Kearsey SE, Mechali M 1996. Chromotin binding, nuclear localization and phosphorylation of Xenopus cdc21 are cell-cycle dependent and associated with the control of initiation of DNA replication. EMBO J 15: 1085–1097 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmann C, Diffley JF, Nasmyth KA 1995. S-phase-promoting cyclin-dependent kinases prevent re-replication by inhibiting the transition of replication origins to a pre-replicative state. Curr Biol 5: 1257–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debatisse M, El Achkar E, Dutrillaux B 2006. Common fragile sites nested at the interfaces of early and late-replicating chromosome bands: Cis acting components of the G2/M checkpoint? Cell Cycle 5: 578–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmolino LM, Saha P, Dutta A 2001. Multiple mechanisms regulate subcellular localization of human CDC6. J Biol Chem 276: 26947–26954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detweiler CS, Li JJ 1998. Ectopic induction of Clb2 in early G1 phase is sufficient to block prereplicative complex formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 2384–2389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deweese JE, Osheroff N 2009. The DNA cleavage reaction of topoisomerase II: Wolf in sheep’s clothing. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 738–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury LS, Perkins G, Diffley JF 1997. The Cdc4/34/53 pathway targets Cdc6p for proteolysis in budding yeast. EMBO J 16: 5966–5976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury LS, Perkins G, Diffley JF 2000. The cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc28p regulates distinct modes of Cdc6p proteolysis during the budding yeast cell cycle. Curr Biol 10: 231–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin SG, Glover TW 2007. Chromosome fragile sites. Annu Rev Genet 41: 169–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsasser S, Chi Y, Yang P, Campbell JL 1999. Phosphorylation controls timing of Cdc6p destruction: A biochemical analysis. Mol Biol Cell 10: 3263–3277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falck J, Mailand N, Syljuasen RG, Bartek J, Lukas J 2001. The ATM-Chk2-Cdc25A checkpoint pathway guards against radioresistant DNA synthesis. Nature 410: 842–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findeisen M, El-Denary M, Kapitza T, Graf R, Strausfeld U 1999. Cyclin A-dependent kinase activity affects chromatin binding of ORC, Cdc6, and MCM in egg extracts of Xenopus laevis. Eur J Biochem 264: 415–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Yamada C, Tsurumi T, Hanaoka F, Matsuzawa K, Inagaki M 1998. Cell cycle- and chromatin binding state-dependent phosphorylation of human MCM heterohexameric complexes. A role for cdc2 kinase. J Biol Chem 273: 17095–17101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Ishimi Y, Nakamura H, Kiyono T, Tsurumi T 2002. Nuclear organization of DNA replication initiation proteins in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 277: 10354–10361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge XQ, Blow JJ 2010. Chk1 inhibits replication factory activation but allows dormant origin firing in existing factories. J Cell Biol 191: 1285–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan V, Simancek P, Houchens C, Snaith HA, Frattini MG, Sazer S, Kelly TJ 2001. Redundant control of rereplication in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 13114–13119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BM, Finn KJ, Li JJ 2010. Loss of DNA replication control is a potent inducer of gene amplification. Science 329: 943–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarino E, Shepherd ME, Salguero I, Hua H, Deegan RS, Kearsey SE 2011. Cdt1 proteolysis is promoted by dual PIP degrons and is modulated by PCNA ubiquitylation. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 5978–5990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassepass I, Voit R, Hoffmann I 2003. Phosphorylation at serine 75 is required for UV-mediated degradation of human Cdc25A phosphatase at the S-phase checkpoint. J Biol Chem 278: 29824–29829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller RC, Kang S, Lam WM, Chen S, Chan CS, Bell SP 2011. Eukaryotic origin-dependent DNA replication in vitro reveals sequential action of DDK and S-CDK kinases. Cell 146: 80–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JS, Cazaux C 2010. Aberrant expression of alternative DNA polymerases: A source of mutator phenotype as well as replicative stress in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 20: 312–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook SS, Lin JJ, Dutta A 2007. Mechanisms to control rereplication and implications for cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19: 663–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Xiong Y 2006. An evolutionarily conserved function of proliferating cell nuclear antigen for Cdt1 degradation by the Cul4-Ddb1 ubiquitin ligase in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem 281: 3753–3756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, McCall CM, Ohta T, Xiong Y 2004. Targeted ubiquitination of CDT1 by the DDB1-CUL4A-ROC1 ligase in response to DNA damage. Nat Cell Biol 6: 1003–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TT, Nijman SM, Mirchandani KD, Galardy PJ, Cohn MA, Haas W, Gygi SP, Ploegh HL, Bernards R, D’Andrea AD 2006. Regulation of monoubiquitinated PCNA by DUB autocleavage. Nat Cell Biol 8: 339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilves I, Petojevic T, Pesavento JJ, Botchan MR 2010. Activation of the MCM2–7 helicase by association with Cdc45 and GINS proteins. Mol Cell 37: 247–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimi Y, Komamura-Kohno Y 2001. Phosphorylation of Mcm4 at specific sites by cyclin-dependent kinase leads to loss of Mcm4,6,7 helicase activity. J Biol Chem 276: 34428–34433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimi Y, Komamura-Kohno Y, You Z, Omori A, Kitagawa M 2000. Inhibition of Mcm4,6,7 helicase activity by phosphorylation with cyclin A/Cdk2. J Biol Chem 275: 16235–16241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallepalli PV, Kelly TJ 1996. Rum1 and Cdc18 link inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase to the initiation of DNA replication in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Dev 10: 541–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallepalli PV, Brown GW, Muzi-Falconi M, Tien D, Kelly TJ 1997. Regulation of the replication initiator protein p65cdc18 by CDK phosphorylation. Genes Dev 11: 2767–2779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Li H, Sun Y 2011. Induction of p21-dependent senescence by an NAE inhibitor, MLN4924, as a mechanism of growth suppression. Neoplasia 13: 561–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Wells NJ, Hunter T 1999. Multistep regulation of DNA replication by Cdk phosphorylation of HsCdc6. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 6193–6198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Arias EE, Chen J, Harper JW, Walter JC 2006. A family of diverse Cul4-Ddb1-interacting proteins includes Cdt2, which is required for S phase destruction of the replication factor Cdt1. Mol Cell 23: 709–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannouche PL, Wing J, Lehmann AR 2004. Interaction of human DNA polymerase η with monoubiquitinated PCNA: A possible mechanism for the polymerase switch in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell 14: 491–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnani N, Dutta A 2011. The effect of the intra-S-phase checkpoint on origins of replication in human cells. Genes Dev 25: 621–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee Y, D’Andrea AD 2010. Expanded roles of the Fanconi anemia pathway in preserving genomic stability. Genes Dev 24: 1680–1694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Kipreos ET 2007. The Caenorhabditis elegans replication licensing factor CDT-1 is targeted for degradation by the CUL-4/DDB-1 complex. Mol Cell Biol 27: 1394–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Nozaki N, Sugimoto K 1994. DNA polymerase α associated protein P1, a murine homolog of yeast MCM3, changes its intranuclear distribution during the DNA synthetic period. EMBO J 13: 4311–4320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kominami K, Toda T 1997. Fission yeast WD-repeat protein pop1 regulates genome ploidy through ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor Rum1 and the S-phase initiator Cdc18. Genes Dev 11: 1548–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labib K 2010. How do Cdc7 and cyclin-dependent kinases trigger the initiation of chromosome replication in eukaryotic cells? Genes Dev 24: 1208–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labib K, Diffley JF, Kearsey SE 1999. G1-phase and B-type cyclins exclude the DNA-replication factor Mcm4 from the nucleus. Nat Cell Biol 1: 415–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Hong B, Choi JM, Kim Y, Watanabe S, Ishimi Y, Enomoto T, Tada S, Cho Y 2004. Structural basis for inhibition of the replication licensing factor Cdt1 by geminin. Nature 430: 913–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KY, Bang SW, Yoon SW, Lee SH, Yoon JB, Hwang DS 2012. Phosphorylation of ORC2 protein dissociates origin recognition complex from chromatin and replication origins. J Biol Chem 287: 11891–11898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei M, Tye BK 2001. Initiating DNA synthesis: From recruiting to activating the MCM complex. J Cell Sci 114: 1447–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei M, Kawasaki Y, Young MR, Kihara M, Sugino A, Tye BK 1997. Mcm2 is a target of regulation by Cdc7-Dbf4 during the initiation of DNA synthesis. Genes Dev 11: 3365–3374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengronne A, Schwob E 2002. The yeast CDK inhibitor Sic1 prevents genomic instability by promoting replication origin licensing in late G(1). Mol Cell 9: 1067–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Leonard AC, Méchali M 2013. DNA replication origins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a010116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letessier A, Millot GA, Koundrioukoff S, Lachages AM, Vogt N, Hansen RS, Malfoy B, Brison O, Debatisse M 2011. Cell-type-specific replication initiation programs set fragility of the FRA3B fragile site. Nature 470: 120–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CJ, DePamphilis ML 2002. Mammalian Orc1 protein is selectively released from chromatin and ubiquitinated during the S-to-M transition in the cell division cycle. Mol Cell Biol 22: 105–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhao Q, Liao R, Sun P, Wu X 2003. The SCF(Skp2) ubiquitin ligase complex interacts with the human replication licensing factor Cdt1 and regulates Cdt1 degradation. J Biol Chem 278: 30854–30858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CJ, Vassilev A, DePamphilis ML 2004. Role for Cdk1 (Cdc2)/cyclin A in preventing the mammalian origin recognition complex’s largest subunit (Orc1) from binding to chromatin during mitosis. Mol Cell Biol 24: 5875–5886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JJ, Dutta A 2007. ATR pathway is the primary pathway for activating G2/M checkpoint induction after re-replication. J Biol Chem 282: 30357–30362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JJ, Milhollen MA, Smith PG, Narayanan U, Dutta A 2010. NEDD8-targeting drug MLN4924 elicits DNA rereplication by stabilizing Cdt1 in S phase, triggering checkpoint activation, apoptosis, and senescence in cancer cells. Cancer Res 70: 10310–10320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LF, Desai SD, Li TK, Mao Y, Sun M, Sim SP 2000. Mechanism of action of camptothecin. Ann NY Acad Sci 922: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu E, Li X, Yan F, Zhao Q, Wu X 2004. Cyclin-dependent kinases phosphorylate human Cdt1 and induce its degradation. J Biol Chem 279: 17283–17288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida YJ, Dutta A 2007. The APC/C inhibitor, Emi1, is essential for prevention of rereplication. Genes Dev 21: 184–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida YJ, Hamlin JL, Dutta A 2005. Right place, right time, and only once: Replication initiation in metazoans. Cell 123: 13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masai H, Matsui E, You Z, Ishimi Y, Tamai K, Arai K 2000. Human Cdc7-related kinase complex. In vitro phosphorylation of MCM by concerted actions of Cdks and Cdc7 and that of a criticial threonine residue of Cdc7 bY Cdks. J Biol Chem 275: 29042–29052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch SD, Kunkel TA 2008. The fidelity of DNA synthesis by eukaryotic replicative and translesion synthesis polymerases. Cell Res 18: 148–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry TJ 2002. Geminin deficiency causes a Chk1-dependent G2 arrest in Xenopus. Mol Biol Cell 13: 3662–3671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry TJ, Kirschner MW 1998. Geminin, an inhibitor of DNA replication, is degraded during mitosis. Cell 93: 1043–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melixetian M, Ballabeni A, Masiero L, Gasparini P, Zamponi R, Bartek J, Lukas J, Helin K 2004. Loss of Geminin induces rereplication in the presence of functional p53 J Cell Biol 165: 473–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez J, Zou-Yang XH, Kim SY, Hidaka M, Tansey WP, Stillman B 2002. Human origin recognition complex large subunit is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis after initiation of DNA replication. Mol Cell 9: 481–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylov IS, Kondo T, Jones L, Ryzhikov S, Tanaka J, Zheng J, Higa LA, Minamino N, Cooley L, Zhang H 2002. Control of DNA replication and chromosome ploidy by geminin and cyclin A. Mol Cell Biol 22: 1868–1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura S, Seki T, Tanaka S, Diffley JF 2004. Phosphorylation-dependent binding of mitotic cyclins to Cdc6 contributes to DNA replication control. Nature 431: 1118–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll T, Tebb G, Surana U, Robitsch H, Nasmyth K 1991. The role of phosphorylation and the CDC28 protein kinase in cell cycle-regulated nuclear import of the S. cerevisiae transcription factor SWI5. Cell 66: 743–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motegi A, Sood R, Moinova H, Markowitz SD, Liu PP, Myung K 2006. Human SHPRH suppresses genomic instability through proliferating cell nuclear antigen polyubiquitination. J Cell Biol 175: 703–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu S, Hirai K, Tak YS, Kamimura Y, Araki H 2010. CDK-dependent complex formation between replication proteins Dpb11, Sld2, Pol ε, and GINS in budding yeast. Genes Dev 24: 602–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam EA, Cortez D 2011. ATR signalling: More than meeting at the fork. Biochem J 436: 527–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrini S, Gorgoulis VG, Halazonetis TD 2010. Genomic instability—An evolving hallmark of cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 220–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VQ, Co C, Irie K, Li JJ 2000. Clb/Cdc28 kinases promote nuclear export of the replication initiator proteins Mcm2–7. Curr Biol 10: 195–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VQ, Co C, Li JJ 2001. Cyclin-dependent kinases prevent DNA re-replication through multiple mechanisms. Nature 411: 1068–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitani H, Taraviras S, Lygerou Z, Nishimoto T 2001. The human licensing factor for DNA replication Cdt1 accumulates in G1 and is destabilized after initiation of S-phase. J Biol Chem 276: 44905–44911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitani H, Sugimoto N, Roukos V, Nakanishi Y, Saijo M, Obuse C, Tsurimoto T, Nakayama KI, Nakayama K, Fujita M, et al. 2006. Two E3 ubiquitin ligases, SCF-Skp2 and DDB1-Cul4, target human Cdt1 for proteolysis. EMBO J 25: 1126–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noton E, Diffley JF 2000. CDK inactivation is the only essential function of the APC/C and the mitotic exit network proteins for origin resetting during mitosis. Mol Cell 5: 85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nougarede R, Della Seta F, Zarzov P, Schwob E 2000. Hierarchy of S-phase-promoting factors: Yeast Dbf4-Cdc7 kinase requires prior S-phase cyclin-dependent kinase activation. Mol Cell Biol 20: 3795–3806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasion SG, Forsburg SL 1999. Nuclear localization of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Mcm2/Cdc19p requires MCM complex assembly. Mol Biol Cell 10: 4043–4057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen RD, Cimprich KA 2007. The ATR pathway: Fine-tuning the fork. DNA Repair (Amst) 6: 953–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereverzeva I, Whitmire E, Khan B, Coue M 2000. Distinct phosphoisoforms of the Xenopus Mcm4 protein regulate the function of the Mcm complex. Mol Cell Biol 20: 3667–3676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petermann E, Helleday T 2010. Pathways of mammalian replication fork restart. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 683–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen BO, Lukas J, Sorensen CS, Bartek J, Helin K 1999. Phosphorylation of mammalian CDC6 by cyclin A/CDK2 regulates its subcellular localization. EMBO J 18: 396–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston BD, Albertson TM, Herr AJ 2010. DNA replication fidelity and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 20: 281–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randell JC, Fan A, Chan C, Francis LI, Heller RC, Galani K, Bell SP 2010. Mec1 is one of multiple kinases that prime the Mcm2–7 helicase for phosphorylation by Cdc7. Mol Cell 40: 353–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rhind N, Gilbert DM 2013. DNA replication timing. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a010132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha P, Chen J, Thome KC, Lawlis SJ, Hou ZH, Hendricks M, Parvin JD, Dutta A 1998. Human CDC6/Cdc18 associates with Orc1 and cyclin-cdk and is selectively eliminated from the nucleus at the onset of S phase. Mol Cell Biol 18: 2758–2767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansam CL, Shepard JL, Lai K, Ianari A, Danielian PS, Amsterdam A, Hopkins N, Lees JA 2006. DTL/CDT2 is essential for both CDT1 regulation and the early G2/M checkpoint. Genes Dev 20: 3117–3129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Yuan P, Dhar SK, Senga T, Takeda D, Robinson H, Kornbluth S, Swaminathan K, Dutta A 2004. A dimerized coiled-coil domain and an adjoining part of geminin interact with two sites on Cdt1 for replication inhibition. Mol Cell 15: 245–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senga T, Sivaprasad U, Zhu W, Park JH, Arias EE, Walter JC, Dutta A 2006. PCNA is a cofactor for Cdt1 degradation by CUL4/DDB1-mediated N-terminal ubiquitination. J Biol Chem 281: 6246–6252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu YJ, Stillman B 2010. The Dbf4-Cdc7 kinase promotes S phase by alleviating an inhibitory activity in Mcm4. Nature 463: 113–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Siddiqui K, On KF, Diffley JFX 2013. Regulating DNA replication in eukarya. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a012930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Liu XS, Davis K, Liu X 2011. Plk1 phosphorylation of Orc2 promotes DNA replication under conditions of stress. Mol Cell Biol 31: 4844–4856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy TA, Smith PG, Milhollen MA, Berger AJ, Gavin JM, Adhikari S, Brownell JE, Burke KE, Cardin DP, Critchley S, et al. 2009. An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature 458: 732–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada S, Li A, Maiorano D, Mechali M, Blow JJ 2001. Repression of origin assembly in metaphase depends on inhibition of RLF-B/Cdt1 by geminin. Nat Cell Biol 3: 107–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda DY, Parvin JD, Dutta A 2005. Degradation of Cdt1 during S phase is Skp2-independent and is required for efficient progression of mammalian cells through S phase. J Biol Chem 280: 23416–23423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Araki H 2010. Regulation of the initiation step of DNA replication by cyclin-dependent kinases. Chromosoma 119: 565–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Tanaka S, Araki H 2013. Helicase activation and establishment of replication forks at chromosomal origins of replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a010371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Diffley JF 2002. Interdependent nuclear accumulation of budding yeast Cdt1 and Mcm2–7 during G1 phase. Nat Cell Biol 4: 198–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Knapp D, Nasmyth K 1997. Loading of an Mcm protein onto DNA replication origins is regulated by Cdc6p and CDKs. Cell 90: 649–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Umemori T, Hirai K, Muramatsu S, Kamimura Y, Araki H 2007. CDK-dependent phosphorylation of Sld2 and Sld3 initiates DNA replication in budding yeast. Nature 445: 328–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardat M, Brustel J, Kirsh O, Lefevbre C, Callanan M, Sardet C, Julien E 2010. The histone H4 Lys 20 methyltransferase PR-Set7 regulates replication origins in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol 12: 1086–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terai K, Abbas T, Jazaeri AA, Dutta A 2010. CRL4(Cdt2) E3 ubiquitin ligase monoubiquitinates PCNA to promote translesion DNA synthesis. Mol Cell 37: 143–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomer M, May NR, Aggarwal BD, Kwok G, Calvi BR 2004. Drosophila double-parked is sufficient to induce re-replication during development and is regulated by cyclin E/CDK2. Development 131: 4807–4818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov IT, Attaran A, Kearsey SE 1995. BM28, a human member of the MCM2–3-5 family, is displaced from chromatin during DNA replication. J Cell Biol 129: 1433–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unk I, Hajdu I, Fatyol K, Szakal B, Blastyak A, Bermudez V, Hurwitz J, Prakash L, Prakash S, Haracska L 2006. Human SHPRH is a ubiquitin ligase for Mms2-Ubc13-dependent polyubiquitylation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 18107–18112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vas A, Mok W, Leatherwood J 2001. Control of DNA rereplication via Cdc2 phosphorylation sites in the origin recognition complex. Mol Cell Biol 21: 5767–5777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri C, Saxena S, Jeon Y, Lee C, Murata K, Machida Y, Wagle N, Hwang DS, Dutta A 2003. A p53-dependent checkpoint pathway prevents rereplication. Mol Cell 11: 997–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter JC 2000. Evidence for sequential action of cdc7 and cdk2 protein kinases during initiation of DNA replication in Xenopus egg extracts. J Biol Chem 275: 39773–39778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Tateishi S, Kawasuji M, Tsurimoto T, Inoue H, Yamaizumi M 2004. Rad18 guides polη to replication stalling sites through physical interaction and PCNA monoubiquitination. EMBO J 23: 3886–3896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich M, Stillman B 1999. Cdc7p-Dbf4p kinase binds to chromatin during S phase and is regulated by both the APC and the RAD53 checkpoint pathway. EMBO J 18: 5334–5346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmes GM, Archambault V, Austin RJ, Jacobson MD, Bell SP, Cross FR 2004. Interaction of the S-phase cyclin Clb5 with an “RXL” docking sequence in the initiator protein Orc6 provides an origin-localized replication control switch. Genes Dev 18: 981–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlschlegel JA, Dwyer BT, Dhar SK, Cvetic C, Walter JC, Dutta A 2000. Inhibition of eukaryotic DNA replication by geminin binding to Cdt1. Science 290: 2309–2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuarin J, Buck V, Nurse P, Millar JB 2002. Stable association of mitotic cyclin B/Cdc2 to replication origins prevents endoreduplication. Cell 111: 419–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegerman P, Diffley JF 2007. Phosphorylation of Sld2 and Sld3 by cyclin-dependent kinases promotes DNA replication in budding yeast. Nature 445: 281–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Watkins JL, Piwnica-Worms H 2002. Disruption of the checkpoint kinase 1/cell division cycle 25A pathway abrogates ionizing radiation-induced S and G2 checkpoints. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 14795–14800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Depamphilis ML 2009. Selective killing of cancer cells by suppression of geminin activity. Cancer Res 69: 4870–4877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Dutta A 2006. An ATR- and BRCA1-mediated Fanconi anemia pathway is required for activating the G2/M checkpoint and DNA damage repair upon rereplication. Mol Cell Biol 26: 4601–4611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Chen Y, Dutta A 2004. Rereplication by depletion of geminin is seen regardless of p53 status and activates a G2/M checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol 24: 7140–7150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Abbas T, Dutta A 2005. DNA replication and genomic instability. Adv Exp Med Biol 570: 249–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Lee CY, Johnson RL, Wichterman J, Huang R, DePamphilis ML 2011. An image-based, high-throughput screening assay for molecules that induce excess DNA replication in human cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res 9: 294–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Zielke N, Edgar BA, DePamphilis ML 2013. Endoreplication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5: a012948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]