Abstract

The effects of low-frequency (50, 100, 200 and 400 Hz) ‘suppressor’ tones on responses to moderate-level characteristic frequency (CF) tones were measured in chinchilla auditory nerve fibers. Two-tone interactions were evident at suppressor intensities of 70–100 dB SPL. In this range, the average response rate decreased as a function of increasing suppressor level and the instantaneous response rate was modulated periodically. At suppression threshold, the phase of suppression typically coincided with basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani, regardless of CF. At higher suppressor levels, two suppression maxima coexisted, synchronous with peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani and scala vestibuli. Modulation and rate-suppression thresholds did not vary as a function of spontaneous activity and were only minimally correlated with fiber sensitivity. Except for fibers with CF < 1 kHz, modulation and rate-suppression thresholds were lower than rate and phase-locking thresholds for the suppressor tones presented alone. In the case of high-CF fibers with low spontaneous activity, excitation thresholds could exceed suppression thresholds by more than 30 dB. The strength of modulation decreased systematically with increasing suppressor frequency. For a given suppressor frequency, modulation was strongest in high-CF fibers and weakest in low-CF fibers. The present findings strongly support the notion that low-frequency suppression in auditory nerve fibers largely reflects an underlying basilar membrane phenomenon closely related to compressive non-linearity.

Keywords: Auditory nerve, Biasing, Modulation, Rate suppression, Basilar membrane, Inner hair cells, Cochlea, Chinchilla

1. Introduction

The responses of auditory nerve fibers to a characteristic frequency (CF) tone paired with a low-frequency tone exhibit rate suppression, a reduction in the average rate of response to the CF tone (Sachs and Kiang, 1968; Abbas and Sachs, 1976), and modulation, a periodic rate reduction that is phase-locked to the low-frequency tone (Kroin et al., 1980; Sachs and Hubbard, 1981; Sellick et al., 1982a). At the base of the mammalian cochlea, counterparts of low-frequency modulation and suppression have been found in basilar membrane vibrations (e.g. Patuzzi et al., 1984b; Ruggero et al., 1992; Rhode and Cooper, 1993; Geisler and Nuttall, 1997), in agreement with the notion that these phenomena originate from a feedback relationship between the organ of Corti and the basilar membrane (e.g. Zwicker, 1979; Patuzzi et al., 1989; Geisler et al., 1990).

Although the bulk of the evidence supports a basilar membrane origin of low-frequency modulation and suppression, some aspects of these phenomena remain controversial. Firstly, whereas reduction of basilar membrane responses to CF tones has been usually associated with peak displacements toward scala tympani or scala vestibuli (Patuzzi et al., 1984b; Rhode and Cooper, 1993; Cooper, 1996; Geisler and Nuttall, 1997), one study reported that suppression coincided with peak velocity (Ruggero et al., 1992) and another found that “the phases of … suppression did not appear to be fixed with respect … to the suppressor tone” (Cooper and Rhode, 1996b). Secondly, some investigations have produced evidence that low-frequency suppression and modulation in the auditory nerve may be strongly influenced or even dominated by factors other than basilar membrane vibration (Hill et al., 1994; Hill and Hong, 1995; Cai and Geisler 1996b)). Thirdly, there are glaring discrepancies among the phases of maximal suppression reported in various studies in the auditory nerve. One study in guinea pig found that maximal suppression in high-CF neurons occurs at the phase of the suppressor that is excitatory when the suppressor is presented alone (Sellick et al., 1982a). Another study made a similar observation in high-CF neurons of cat but found that the phases of suppression did not coincide with those of single-tone excitation in the case of low-CF neurons (Sachs and Hubbard, 1981). Yet another study in cat found that single-tone excitation and maximal suppression have phases that differ by some 90 degrees in most neurons, regardless of CF (Cai and Geisler, 1996a). In guinea pig high-CF neurons, maximal suppression is synchronous with peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani (Kroin et al., 1980; Sellick et al., 1982a; Patuzzi et al., 1984a). In contrast, maximum suppression in cat auditory nerve fibers, regardless of CF, is synchronous with peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala vestibuli (Cai and Geisler, 1996a).

We describe here low-frequency suppression and modulation in the auditory nerve of the chinchilla, a species for which data are also available on auditory nerve responses to single low-frequency tones (Ruggero and Rich, 1983, 1987; Ruggero et al., 1996a) and on basilar membrane modulation and suppression at basal and apical cochlear sites (Ruggero et al., 1992; Cooper and Rhode, 1996b). The present findings, in combination with a revised interpretation of existing basilar membrane data Ruggero et al., 1992), strongly support a basilar membrane origin of modulation and suppression in the chinchilla cochlea. Certain features of modulation and suppression in the auditory nerve may indicate that the corresponding basilar membrane phenomena become less prominent as the cochlear apex is approached. Other features may originate in the inner hair cells. The initial results of this investigation have been published in abstract form (Temchin et al., 1994).

2. Methods

The experimental techniques employed here have been described elsewhere (Ruggero and Rich, 1983, 1987; Ruggero et al., 1996a). Forty-five adult chinchillas were initially anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg, injected subcutaneously) and sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg, injected intraperitoneally). Deep anesthesia was maintained with supplemental doses of pentobarbital. [At the end of the experiments, the animal was killed by decapitation while still deeply anesthetized.] Core body temperature was kept near 38°C by means of a servo-controlled electrical heating pad. Tracheotomy and tracheal intubation allowed for forced respiration, which was used only as necessitated by apnea or labored breathing. The pinna was resected and part of the bony external ear canal was chipped away. This permitted unobstructed visualization of the umbo of the tympanic membrane and the positioning close to it (within about 2 mm) of the tip of the earphone-coupling speculum. The tendon of the tensor tympani muscle was severed and the stapedius was detached from its bony anchoring. A silver ball electrode, placed on the round window, was used to record cochlear microphonics and compound action potentials (CAPs).

The auditory nerve was approached superiorly after craniotomy and aspiration of part of the lateral cerebellum. Capillary-glass microelectrodes (filled with 3 M NaCl or KC1 solutions, impedance 30–100 mΩ) were initially positioned under observation with an operation microscope and were advanced into the nerve by means of a remote-controlled hydraulic holder. The microelectrode signal was amplified and displayed on an oscilloscope. The oscilloscope was used as a discriminator, triggering standard pulses on the first rising edge of the neural spikes. The pulse times were stored in a computer for further processing.

Acoustic stimuli were generated by means of a custom-built digital waveform generator under computer control (Ruggero and Rich, 1983). Two independent channels were available. A sinusoidal waveform, stored in an 8-K, 16-bit read-only memory, was sampled at selectable rates (depending on the desired audio frequency), converted into analog electrical signals by means of two D/A converters and transduced into acoustic waveforms by two acoustically coupled Beyer DT-48 earphones. The signal amplitudes and phases were specified according to calibration tables generated in situ at the beginning of each experimental session. The calibration tables related the magnitude and phase of the acoustic signals in both channels, measured by means of a miniature microphone close to the eardrum, to the magnitude and phase of the analog electrical signals. The experimenter selected the SPL (sound pressure level re 20 μPa) and the phase (zero phase corresponding to maximum rarefaction) of stimulus sinusoids and the computer accordingly set two programmable attenuators and the starting address of the waveform-generator read-only memory. The onset and offset of the stimulus sinusoids were obtained by multiplying the sinusoid with one half of a raised-cosine period, with a 10–90% rise or decay time of 4 ms.

The spectral composition of low-frequency stimuli produced by the sound system has been described in some detail (see Table 1 in Ruggero et al., 1996a). Briefly, for low-frequency tones the magnitude of second-harmonic distortion measured in an artificial cavity was typically less than −50 dB re the fundamental at stimulus levels of 106–108 dB SPL but in live chinchillas it could reach −30 dB.

Upon isolation, each auditory nerve fiber was characterized by determining its spontaneous activity from a 10-s sample and by measuring a frequency-threshold tuning curve. [The latter applied an automated adaptive algorithm (Kiang et al., 1970; see also Liberman, 1978) and used 50-ms tone bursts presented every 100 ms. The threshold criterion was fulfilled when spike counts during the tone bursts elicited one more spike than in the following 50-ms inter-stimulus interval.] Then, the responses to low-frequency tones (50, 100, 200, or 400 Hz), presented alone or simultaneously with a probe tone, were measured as a function of the intensity of the low-frequency suppressor or the probe-tone. Only responses from fibers whose CFs were at least twice the frequency of the suppressor were included in our database. Spike times were displayed on line, modulo one period of the low-frequency suppressor tone, as a scatter plot or ‘phase-intensity matrix’ (Fig. 3A,B, Fig. 4A,B), with phase represented in the ordinate and stimulus intensity represented in the abscissa (Liberman and Kiang, 1984; Ruggero et al., 1996a). Single-tone or two-tone stimuli were presented, in 2-dB steps in random order, over a wide intensity range spanning levels from below rate threshold up to the limits imposed by the hardware (100–118 dB SPL). Intermittent presentation of short-duration tone bursts (5 repetitions, 100-ms duration, 300-ms repetition period) ensured that even the most intense stimuli did not induce temporary threshold shifts. The initial phase of the suppressor tone was kept constant across stimulus repetitions but that of the probe tone was randomized. Spike times were sampled throughout the stimulus duration. It was shown that possible onset effects that may be evident at high SPLs do not alter neural response phases (Ruggero et al., 1996a).

Fig. 3.

Intensity dependence in the responses of a high-CF (7.8 kHz) auditory nerve fiber to a 100-Hz tone presented alone (A) or in combination with a near-CF tone (B). The near-CF tone was presented at 15 dB above threshold. The phase-intensity matrices (panels A and B) display spike times (modulo the period of the suppressor tone, 10 ms) relative to maximal rarefaction at the eardrum (ordinate) as a function of suppressor intensity (abscissa). C: Rate-intensity functions for the responses to the suppressor alone (solid line) and in combination with the near-CF probe tone (dashed line). D: Solid line: difference between the rates of responses to the single- and two-tone stimuli, plotted against suppressor intensity. Filled circles: amplitude of the first Fourier harmonic, computed from the period histograms of the difference matrix (B minus A) and normalized to the maximal driven rate (i.e. maximal rate minus spontaneous rate) for the probe presented alone. Open circles: amplitude of the second Fourier harmonic. The Fourier analysis was performed on the difference matrix in order to isolate the interaction between the suppressor and the probe. Data in panels C and D were smoothed by 3-point averaging. For the sake of population analysis (e.g. Figs. 10–15), the following parameters were calculated for each pair of rate-intensity functions, as depicted in panel C: spontaneous rate (40.3 spikes/s; lower dotted line), averaged response to probe alone (205.5 spikes/s; upper dotted line), phase-locking threshold (intensity at which vector strength [Goldberg and Brown, 1969] reached a value of 0.3: 66 dB SPL; closed square), rate threshold for the suppressor presented alone (20 spikes/s higher than spontaneous rate: 73.4 dB SPL; closed circle), threshold for rate suppression (20 spikes/s lower than the response to the probe alone: 66.3 dB SPL; open square), and the suppressor level (86.8 dB SPL) at which the two-tone rate function reaches its minimum (85 spikes/s; open circle). Triangle in B indicates the modulation threshold (68 dB SPL), determined by visual inspection. Fiber threshold at CF: 2 dB SPL, spontaneous activity: 39.9 spikes/s.

Fig. 4.

Intensity dependence in the responses of a high-CF fiber with medium spontaneous activity to a 50-Hz tone presented alone (upper panels) or in combination with a near-CF tone. The probe tone (11 kHz) was presented at 24 dB SPL (triangle in B). The two lower panels show rate-intensity functions for the single-tone (solid line) and two-tone (dashed line) stimuli. Other details, including symbols, are as described for Fig. 3. Fiber CF: 11 kHz; CF threshold: 9 dB SPL; spontaneous activity: 4.1 spikes/s.

In addition to the brief stimulation protocol required for the phase-intensity matrices, many fibers were studied using longer-duration stimuli (2 s, 10 repetitions and 3-s repetition period), which were used to construct 64-bin period histograms (Figs. 1 and 2). As for the phase-intensity matrices, suppressor and probe tones were gated simultaneously and the probe-tone phase was changed randomly after each stimulus repetition.

Fig. 1.

Period histograms for the responses of a high-CF (8.9 kHz) auditory nerve fiber to a 100-Hz suppressor tone presented alone (left column) or in combination with a near-CF probe tone. The abscissa of each histogram (64 bins) spans exactly one period of the suppressor tone (10 ms), with a scale expressed relative to maximal rarefaction at the eardrum. The ordinate indicates the instantaneous rate. The intensities of the suppressor tone are given at left. Dashed lines represent the average firing rates. Data were collected during 10 presentations of 2-s stimuli (suppressor and probe tones gated simultaneously) and smoothed by 3-point averaging. Fiber threshold at CF: 27 dB SPL, spontaneous rate: 10.6 spikes/s.

Fig. 2.

Period histograms for the responses of a low-CF (1.54-kHz) auditory nerve fiber to a 50-Hz suppressor tone presented alone (left column) or in combination with a near-CF probe tone. Fiber threshold at CF: 12 dB SPL, spontaneous rate: 90.8 spikes/s). Other details are the same as for Fig. 1.

The care and use of the animals reported in this study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwestern University.

3. Results

3.1. The main features of modulation

Fig. 1 displays period histograms for responses of a high-CF fiber (CF = 8.9 kHz) to a 100-Hz tone (the ‘suppressor’) presented alone or in combination with 9-kHz probe tones. In each histogram;, the ordinate indicates instantaneous firing rate, the abscissa (spanning one suppressor period, 10 ms) indicates phase relative to peak rarefaction at the eardrum and the dashed line indicates average rate. When the suppressor tone was presented alone (left column), the time of peak excitation coincided with maximal rarefaction for suppressor intensities of 75–95 dB SPL. When a near-CF, 40-dB SPL ‘probe’ tone was paired with a low-level suppressor tone, the average firing rate increased to about 110 spikes/s. For a suppressor intensity of 70 dB SPL, the period histogram exhibited a single trough of suppression at about −120 degrees; i.e., the phase of suppression lagged the phase of excitatory responses to the suppressor by 120 degrees. A second suppression trough appeared when the suppressor level was raised to 75 dB SPL; this suppression trough lead maximal rarefaction by 70 degrees. The two suppression troughs, which became deeper at higher suppressor intensities, were separated by two peaks of excitation and facilitation, about 160 degrees apart.

With a probe level of 40 dB SPL, the biphasic pattern of modulation grew non-monotonically, reaching a maximum magnitude for a suppressor intensity of 85 dB SPL and diminishing at higher suppressor intensities. The largest excitatory peak (coinciding with rarefaction) grew monotonically with suppressor intensity and merged smoothly into the principal response peak evoked by the suppressor tone presented alone. Thus, at the highest suppressor-tone intensities, two-tone responses increasingly resembled the responses to the suppressor tone presented alone. Increasing the intensity of the probe tone to 50 or 60 dB SPL did not alter the basic pattern of two-phase modulation evident in responses for probe levels of 40 dB SPL but did reduce its magnitude.

Fig. 2 displays histograms representing responses of a low-CF fiber (CF =1.5 kHz) to 50-Hz tones presented alone (left column) and paired with near-CF probe tones. Responses to a 30-dB SPL probe tone paired with 65–75 dB SPL suppressor tones were largely dominated by the excitatory responses to the suppressor tones so that a single suppression trough coincided with the non-excitatory phases for the 50-Hz tone. For 40-and 50-dB SPL probe tones, two suppression troughs were evident, separated by approximately 180 degrees, much as in the case of the high-CF fiber of Fig. 1. As in the case of Fig. 1, the magnitude of the modulation pattern grew non-monotonically with stimulus intensity: responses were dominated by the suppressor tone and the probe tone, respectively, at the lowest and highest probe-tone levels and the two-phase modulation pattern was evident at intermediate intensities. Modulation in the low-CF fiber of Fig. 2 differed from the pattern of the high-CF fiber of Fig. 1 in that the deepest suppression trough exhibited a phase lead (rather than a lag) relative to the excitatory peak for the suppressor tone presented alone. The phases of suppression and their relation to the timing of excitation and basilar membrane motion are analyzed in Section 3.4.

3.2. Modulation and rate suppression of responses to CF tones as a function of suppressor level

The effects of low-frequency (suppressor) tones on near-CF responses were studied in 231 auditory nerve fibers (from 37 chinchillas) using phase-intensity matrices such as depicted in Figs. 3 and 4 (Liberman and Kiang, 1984; Ruggero et al., 1996a). In a phase-intensity matrix, each dot expresses the timing of each action potential, modulo the period of the suppressor tone, as a function of the intensity of the suppressor tone. The ordinate scale indicates phase relative to peak rarefaction at the eardrum. The suppressor tones (with frequencies of 50, 100, 200, or 400 Hz) were presented alone (as in Fig. 3A) or in combination with near-CF probe tones (as in Fig. 3B). CFs ranged from 238 Hz to 20.2 kHz. As a rule, the probe level was set at 15–20 dB above CF threshold to evoke moderately strong responses, well above threshold but below saturation.

The main features of single- and two-tone responses seen in the period histograms of Figs. 1 and 2 are also evident in the phase-intensity matrices of Figs. 3 and 4, which are representative of results for fibers with high and low rates of spontaneous activity, respectively. Fig. 3A shows responses of a high-CF fiber to a 100-Hz tone. At intensities below 66 dB SPL the fiber discharged randomly at its spontaneous rate (about 40 spikes/s) but phase locking was evident at higher intensities. In the range between 66 and 90 dB SPL, spikes clustered nearly in phase with maximal rarefaction at the eardrum. An abrupt phase shift (Kiang et al., 1969; Ruggero et al., 1996a) occurred at around 90 dB SPL, so that at higher intensities the fiber responded roughly in phase opposition.

When low-intensity 100-Hz tones were paired with a CF probe tone (Fig. 3B) the average firing rate increased to nearly 200 spikes/s. Modulation of CF responses became evident when suppressor intensity reached 68 dB SPL, the ‘modulation threshold’ (triangle in Fig. 3B). At higher intensities, suppression carved out two valleys from the responses to the CF tone, one of them lagging and the other one leading, by about 90 degrees, the near-threshold responses to the suppressor when presented alone. Thus, within the range of 68–86 dB SPL an excitatory ridge coincided with the phase of the responses to the suppressor when presented alone. A second excitatory ridge was approximately out-of-phase with the first one.

Rate-intensity functions (Fig. 3C) were measured for both single-tone (solid line) and two-tone (dashed line) stimulation. The difference between the two rate functions (solid line in Fig. 3D) is a measure of net rate suppression. Rate suppression had a threshold of 66 dB SPL but could not be measured at intensities higher than 86 dB SPL, at which responses were dominated by the suppressor tone. As a rule, the suppressed response rate did not drop below the rate of response to the suppressor tone presented alone. The magnitude of modulation was measured using a Fourier analysis of the period histograms of a ‘difference matrix’ (computed by subtracting matrix A from matrix B, to isolate the net two-tone interaction). The first Fourier harmonic of the difference matrix (solid circles in Fig. 3D) was generally smaller than the second harmonic (open circles), indicating that modulation was predominantly biphasic at all intensities (as in Figs. 1 and 2). Modulation was largest at an intensity midway within the dynamic ranges of rate suppression and modulation, which were nearly identical.

The modulation threshold could be much lower than the excitatory threshold, especially in high-CF fibers with low spontaneous activity. Fig. 4 shows one case in which a 50-Hz tone could modulate responses to a near-CF probe tone at 74 dB SPL (triangle in Fig. 4B) although its excitatory threshold was not reached at 106 dB SPL. At this intensity, suppression reduced the response to the two-tone stimulus to the level of spontaneous activity. As in the case of Fig. 3, modulation was largely biphasic at all intensities: the magnitudes of the second harmonics of the period histograms (open circles in Fig. 4D) were approximately 4 times as large as the magnitudes of the first harmonics (<0.1, not shown).

3.3. Modulation of CF responses at the base of the cochlea: dependence on suppressor frequency

In order to obtain summary descriptions of modulation as a function of CF and suppressor frequency, phase-intensity matrices (e.g. Figs. 3 and 4) were averaged in CF octave bands for each suppressor frequency (e.g. Fig. 5). The averages were computed for 348 pairs of matrices recorded from 220 fibers in 34 chinchillas. The near-CF probe intensity was, on average, 18 dB above CF threshold.

Fig. 5.

Averaged phase-intensity matrices for the responses of auditory nerve fibers to low-frequency tones presented alone (left column) or in combination with near-CF probe tones. The response phases have been corrected for synaptic and neural delays (so that they may be taken to reflect inner hair cell depolarization) and are expressed relative to peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani (Ruggero et al., 1986a; see also Ruggero et al., 1996a). ST and ST signify maximal displacement or velocity of the basilar membrane toward scala tympani; SV and S′V indicate displacement or velocity toward scala vestibuli. Instantaneous discharge rate is displayed according to a gray scale (see inset in upper left panel) and as iso-rate contours. Solid lines indicate rates of 100 spikes/s and higher, in steps of 100 spikes/s; dashed lines indicate rates of 80 spikes/s and lower, in steps of 20 spikes/s. The near-CF probe tones were presented at intensities that exceeded CF threshold by 15–19 dB, on average. The suppressor frequencies are indicated at upper left corners. Each pair of averaged matrices represents data from 23–53 fibers recorded in 11–17 chinchillas.

The phases of excitation and suppression may be expressed in terms of basilar membrane displacement on the basis of some reasonable assumptions. The fundamental assumption is that the responses of auditory nerve fibers to low-frequency tones reflect a summation of mechanical, neural and synaptic delays (Ruggero and Rich, 1987; Ruggero et al., 1996a). A CF-independent delay, amounting to about 1 ms, arises from travel time in axons and from the synaptic delay. Compensating auditory nerve responses for this delay therefore yields an estimate of the time of depolarization of inner hair cells. The mechanical delays consist of frequency-dependent and frequency-independent components. The frequency-dependent component is the phase-vs.-frequency characteristic at the basal extreme of the cochlea, approximated by direct measurements at a site of the chinchilla basilar membrane distant 3.5 mm from the oval window (Robles et al., 1986; Ruggero et al., 1986a). The frequency-independent but CF-dependent mechanical delays (due to the propagation of the traveling wave on the basilar membrane) are taken to equal the onset delays of responses to intense rarefaction clicks minus the asymptotic, high-CF, onset delay. Compensating the auditory nerve responses (originally expressed relative to acoustic pressure at the eardrum) for all three delay components – mechanical, neural and synaptic – yields phase estimates for the depolarization in inner hair cells relative to basilar membrane displacement. The phase estimates probably are quite accurate for high-CF fibers but they are progressively more tentative for lower CFs (Ruggero et al., 1996a).

Fig. 5 shows averaged phase-intensity matrices for the responses of many high-CF fibers (CF: 6–12 kHz) to single- and two-tone stimuli, corrected (according to the procedures outlined in the previous paragraph) so that neural excitation is expressed as depolarization of inner hair cells (darker shading) relative to basilar membrane displacement. The features of the averaged matrices, computed for suppressor frequencies of 50, 100, 200 and 400 Hz, were similar to those described in Figs. 3–5 for individual responses. Regardless of frequency, when the suppressor tone was presented alone (left column), depolarization of inner hair cells at near-threshold levels occurred roughly in phase with maximal velocity of the basilar membrane toward scala tympani but a second depolarization peak, lagging the first by 90–180 degrees, became evident at levels higher than 85–90 dB SPL (Ruggero et al., 1996a).

When a near-CF probe tone was presented simultaneously with a suppressor tone (right column), responses were dominated by the probe tone at low suppressor intensities. At higher suppressor levels, the responses exhibited modulation. Responses modulated by 50-Hz tones (upper right panel) included two ‘ridges’ of excitation (darker shading), of unequal height, at phases slightly lagging peak basilar membrane velocity toward scala vestibuli and scala tympani. The excitatory ridges flanked two suppression ‘valleys’ (white or lighter shading) which were prominent in the case of suppression by 50-Hz tones but became less distinct at higher suppressor frequencies. One of the valleys was synchronous with peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala vestibuli and the other somewhat lagged peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani. At the highest suppressor intensities (> 90–100 dB SPL), the responses to tone pairs were dominated by the suppressor tone.

To isolate the net modulation effect, the averaged matrices for responses to single, low-frequency tones (Fig. 5, left column) were subtracted from the corresponding matrices for two-tone responses (Fig. 5, right column). These ‘difference matrices’ (Fig. 6, left column) indicate explicitly the (non-linear) interaction between the probe and suppressor tones. At the lowest and highest suppressor levels, responses are dominated by the near-CF probe tones and the suppressor tones, respectively. In the intermediate range of suppressor intensity, responses exhibit one or two suppression valleys (white or lighter shading), intercalated with ridges of excitation (darker shading). The excitation ridges slightly lag maximal basilar membrane velocity toward scala vestibuli and toward scala tympani and the suppression valleys occur during peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani and scala vestibuli.

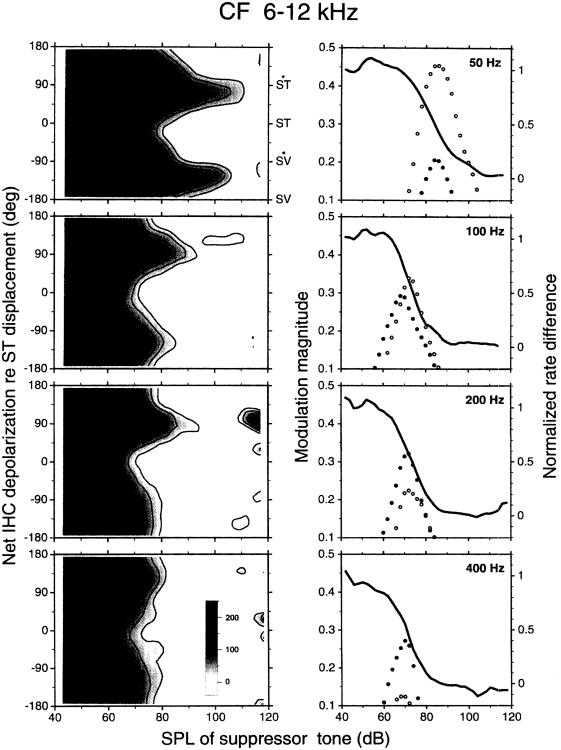

Fig. 6.

The net effect of low-frequency tones upon responses of high-CF auditory nerve fibers to near-CF tones. Each phase-intensity matrix on the left column was obtained from one pair of averaged matrices in Fig. 5 by subtracting the single-tone matrix from the corresponding two-tone matrix. The instantaneous rate difference is expressed according to a gray scale (see inset in lower left panel) and as iso-rate contours (between 20 and 100 spikes/s, in steps of 20 spikes/s). The darkest shading indicates that there was no suppression, whereas white indicates that the responses to the two-tone stimuli were identical to the response to the suppressor presented alone. The panels on the right column plot normalized rate-difference functions (solid lines) and normalized magnitudes of the first and second Fourier harmonics (closed and open circles, respectively) against suppressor intensity. The normalization procedure is described in the Fig. 3 legend.

The right column of Fig. 6 allows a direct comparison of the variation of modulation and rate suppression as a function of suppressor intensity. Rate suppression is expressed as the normalized difference between single-tone and two-tone responses: ‘1’ corresponds to the average response rate elicited by the near-CF probe tone and ‘0’ indicates that single-tone and two-tone responses yielded identical rates. Modulation depth was estimated from the difference matrices by computing, at each intensity, the magnitudes of the first and second Fourier harmonics of the period histograms (filled and open circles, respectively). The Fourier magnitudes are shown in Fig. 6 after normalization to the average rate evoked by the near-CF probe tone. Modulation magnitudes were non-monotonic functions of stimulus intensity (as in Figs. 3D and 4D), reaching their maxima at intensities roughly midway within the dynamic range of rate suppression. The peak magnitude of biphasic modulation (open circles) decreased systematically as a function of increasing suppressor frequency. For 50- and 100-Hz suppressor tones, the magnitudes of the second harmonics exceeded those of the first harmonic, whereas the opposite was the case for 200- and 400-Hz suppressors.

3.4. Modulation of CF responses as a function of cochlear location

The left-column panels of Fig. 7 present averaged phase-intensity matrices for responses to 50-Hz tones in four one-octave CF bands (0.75–1.5 kHz, 1.5–3 kHz, 3–6 kHz and 6–12 kHz). The ordinates indicate the (derived) phase of inner hair cell depolarization relative to the time of peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani (Ruggero et al., 1996a). Inner hair cells with CF<3 kHz respond to 50-Hz tones presented at low and moderate intensity with phases that somewhat lag basilar membrane peak velocity toward scala vestibuli. In contrast, inner hair cells with CF>6 kHz respond at near-threshold levels approximately in phase with peak basilar membrane velocity toward scala tympani. In the middle of the cochlea (CFs=3–6 kHz), inner hair cells may adopt either of these two phases.

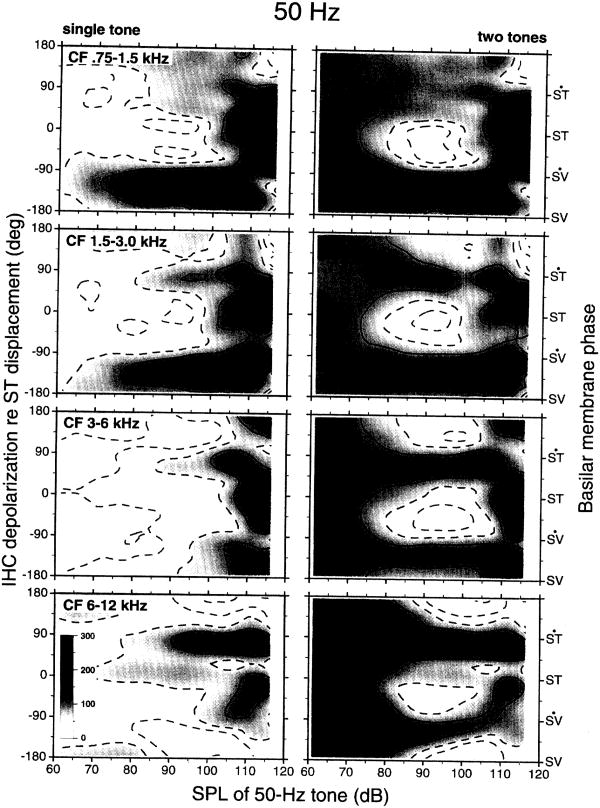

Fig. 7.

Averaged phase-intensity matrices for the responses of auditory nerve fibers to 50-Hz tones presented alone (left column) or in combination with near-CF probe tones (right column). Each pair of averaged phase-intensity matrices represents data from many fibers within a one-octave CF band (indicated at upper left corners). Each pair of averaged matrices represents data from 18–53 fibers recorded in 8–19 chinchillas. The near-CF probe tones were presented at intensities that exceeded CF threshold by 14–17 dB, on average. Other details are as for Fig. 5.

When the 50-Hz suppressor tone is paired with a near-CF probe tone, periodic modulation occurs within a range of suppressor intensities between 75–78 and 100–105 dB SPL. Two excitatory response ridges are evident in all CF ranges at phases corresponding to basilar membrane velocity toward scala tympani and toward scala vestibuli. One of these phases coincides with the excitatory phase of near-threshold responses for suppressor tones presented alone. The excitatory ridges are intercalated by suppression valleys. Irrespective of CF, the suppression valleys occur at phases corresponding to basilar membrane displacements toward scala tympani and toward scala vestibuli.

The left-column panels of Fig. 8 depict the net modulation effect of 50-Hz suppressors for five one-octave CF bands (375–750 Hz to 6–12 kHz), derived in the same way as for Fig. 6. Net-excitation ridges occurred at phases nearly coinciding with peak basilar membrane velocity toward scala vestibuli and toward scala tympani. Net-suppression valleys occurred at phases corresponding to basilar membrane displacement toward scala vestibuli and toward scala tympani. Both the dynamic range of biphasic modulation and its peak magnitude (open circles, right column) decreased systematically as function of decreasing CF. For CFs < 1.5 kHz, modulation was very weak even though rate suppression remained robust.

Fig. 8.

The net effect of 50-Hz suppressor tones upon responses of auditory nerve fibers to near-CF tones. Each pair of phase-intensity matrices represents a one-octave CF band (upper right corners). Each phase-intensity matrix on the left column was obtained from one pair of averaged matrices in Fig. 7 by subtracting the single-tone matrix from the corresponding two-tone matrix. Other details are as for Fig. 6.

Biphasic modulation could be demonstrated in nearly every fiber that was tested using 50-Hz suppressors but it was less commonly found when using higher suppressor frequencies, especially in the case of low-CF fibers (Table 1). The relative paucity of biphasic modulation among low-CF fibers and for higher-frequency suppressors is consistent with the trends seen in the average matrices (Figs. 8 and 6, respectively). Biphasic modulation could be demonstrated in a higher proportion of responses to the higher-frequency suppressors than indicated in Table 1 by using more intense probe tones (see Section 3.5).

Table 1. Distribution of biphasic modulation as a function of suppressor frequency and of fiber CF.

| CFs | Suppressor frequency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 50 Hz | 100 Hz | 200 Hz | 400 Hz | Any frequency | ||

| ≤1.5 kHz | 50 (14/28) | 24 (4/17) | 0 (0/7) | 0 (0/2) | 53 (16/30) | |

| 1.5–3 kHz | 55 (11/20) | 46 (6/13) | 0 (0/2) | 71 (15/21) | ||

| 3–6 kHz | 87 (47/54) | 63 (22/35) | 29 (5/17) | 0 (0/11) | 77 (54/70) | |

| 6–12 kHz | 92 (58/63) | 90 (44/49) | 52 (18/34) | 25 (8/32) | 91 (67/74) | |

| > 12 kHz | 88 (7/8) | 63 (5/8) | 78 (7/9) | 25 (1/4) | 84 (16/19) | |

| All CFs | 79 (137/173) | 66 (81/122) | 44 (30/69) | 18 (9/49) | 79 (168/214) | |

Each cell indicates % and the number of fibers (numerator of fraction between parentheses) exhibiting biphasic modulation.

The average phase-intensity matrices (e.g. Figs. 6 and 8) did not exhibit pronounced differences between the modulation thresholds for the two polarities of basilar membrane displacement. We further addressed this issue by inspecting period histograms recorded from 64 fibers (CFs: 238 Hz–14.5 kHz) in 11 chinchillas at intensities (sampled with 2-dB resolution) around the modulation threshold. These period histograms (e.g. Figs. 1 and 2) were based on much longer sample times than phase-intensity matrices (20 s and 0.5 s, respectively) and thus permitted more precise measurements. At the threshold of modulation, period histograms exhibited a single suppression trough in 72% of fibers and two troughs in 28%. Among histograms showing a single trough at suppression threshold, the trough coincided with peak displacement of the basilar membrane toward scala tympani and scala vestibuli in 81% and 19% of cases, respectively. A second suppression trough, roughly in phase opposition, could be detected at levels exceeding suppression threshold by 5.8 (±3.4) and 3.5 (±1.2) dB, respectively.

3.5. Modulation of CF responses as a function of probe intensity

In high-CF cochlear neurons of cat and guinea pig, maximal suppression may coincide with the excitation phase of the suppressor tone when presented alone (Sachs and Hubbard, 1981; Sellick et al., 1982a). Such coincidence was never found in chinchilla using moderate-level probe tones (Figs. 1–8). We also studied many fibers using an ad-hoc version of the phase-intensity matrix (Fig. 9), and ascertained that the phase of suppression did not depend on probe intensity. The suppressor level was kept constant and the level of the near-CF probe tone was varied (randomly, in 2-dB steps) from below the CF threshold up to at least rate saturation. Fig. 9 shows typical results for a high-CF (8.9 kHz) fiber. At low levels of the probe tone, the phase-intensity matrices exhibited a single ridge of excitation due to the suppressor tone. At higher probe levels, a second ridge of excitation appeared nearly in phase opposition with the first peak, with valleys of suppression interposed between the two ridges. As the intensity of the probe tone was raised further, the suppression valleys became narrower and shallower but their phases remained unchanged, leading or lagging by roughly 90 degrees (rather than coinciding with) the excitatory phases for the suppressor alone. As the suppressor frequency was raised from 100 Hz to 200 and 400 Hz, the threshold of biphasic modulation grew higher and modulation was evident over increasingly shorter ranges of probe-tone intensities.

Fig. 9.

Suppression as a function of probe-tone intensity and suppressor-tone frequency. The suppressor tones (100, 200 or 400 Hz), presented at 76 dB SPL (i.e. just above threshold), were paired with 8.9-kHz probe tones. To facilitate comparison of the matrices for different suppressor-tone frequencies, the response phases are normalized to the excitatory phase for responses to the suppressor presented alone. The bottom right panel shows the corresponding rate-intensity functions (lines) and the normalized magnitude of the second Fourier harmonic (circles), computed from responses modulated by a 100-Hz suppressor (see Fig. 6 legend for normalization procedure). Fiber CF: 8.86 kHz; threshold: 2 dB SPL; spontaneous rate: 44.5 spikes/s.

3.6. Modulation and rate-suppression thresholds as a function of CF

To explore the relationship between modulation, rate suppression and other properties of auditory nerve fibers, we inspected 289 pairs of (single- and two-tone) phase-intensity matrices recorded from 164 fibers in 30 chinchillas. From single-tone matrices, we recorded phase-locking and rate thresholds for responses to suppressor tones presented alone. From two-tone matrices, we recorded modulation and rate-suppression thresholds, as well as the (unsuppressed) average rate at low suppressor intensities and the minimal rate. Threshold definitions are given in Fig. 3.

The thresholds of modulation and average-rate suppression were very similar (Fig. 10), differing on average by only 1.3 ± 5.2 dB (a value which, statistically, did not differ significantly from zero). Modulation thresholds averaged 70.7 dB SPL ± 7 dB (n = 438). Rate-suppression thresholds averaged 69.2 dB SPL ± 8.5 dB (n = 286).

Fig. 10.

Near coincidence between modulation and average-rate suppression thresholds in two-tone responses. Dashed line is a regression line. Data points were randomly shifted horizontally within ± 1 dB to prevent overlapping. See Fig. 3 for definitions of rate-suppression and modulation thresholds.

Modulation and rate-suppression thresholds were nearly independent of CF. In a sample of fibers with high spontaneous activity (Fig. 11), these thresholds (continuous lines), increased only slightly as a function of increasing CF. In contrast, the excitatory thresholds for the low-frequency suppressors presented alone grew substantially. Phase-locking thresholds (thin dashed line) varied from 55–60 dB SPL for CFs < 800 Hz to about 76 dB SPL for CFs > 6 kHz. Rate thresholds (thick dashed line) increased from about 63 dB SPL for CFs < 700 Hz to about 83 dB SPL for CFs > 3 kHz. For CFs higher than 2 kHz, phase-locking thresholds exceeded modulation thresholds by 6 dB, on average, but this difference decreased systematically with decreasing CF. Modulation thresholds exceeded phase-locking thresholds by 6–8 dB in fibers with CFs of about 500 Hz.

Fig. 11.

Single-tone and suppression thresholds as a function of characteristic frequency in high-spontaneous rate (> 18 spikes/s) fibers. Modulation thresholds (thin solid line) were determined by visual inspection of individual phase-intensity matrices (such as those in Fig. 3B). Average-rate thresholds for suppression and for excitation by the suppressor tone when presented alone (thick solid and dashed lines, respectively) were determined as described in the legend of Fig. 3. Mean phase-locking and modulation thresholds (±S.D.) are given for the 6–12 kHz CF range (open and filled circles and brackets). Data points were averaged in 1/3-octave bands and smoothed by 3-point averaging.

Data in Figs. 10–15 are presented without regard to suppressor frequency because modulation and rate-suppression thresholds were very similar for 100–400-Hz tones and only slightly lower than for 50-Hz tones (Fig. 6). However, the difference between the thresholds of excitation and modulation (or suppression) tended to decrease as a function of increasing suppressor frequency. In fibers with CFs > 3 kHz exhibiting high spontaneous activity, rate thresholds exceeded modulation thresholds by 13.6 dB, 14.8, 9.0 and 6.1 dB, respectively, for suppressor tones with frequency of 50, 100, 200 and 400 Hz. A linear regression line fitted to these data has a slope of −2.8 dB/octave (i.e. change of difference threshold per doubling of suppressor frequency).

Fig. 15.

A: Minimal fractional response index as a function of the amount by which single-tone rate threshold exceeds rate-suppression threshold. The dashed line is a regression line. The data symbols encode spontaneous activity (see legend). B: Rate-intensity functions of an insensitive low-spontaneous fiber to suppressor tones presented alone (solid line) or in combination with near-CF probe tones (dashed line). C: as B but for a sensitive fiber. Symbols in panel A encode spontaneous activity (see Fig. 14A). Symbols in panels B and C are as in Fig. 3C. The amount by which rate threshold exceeds rate-suppression threshold is indicated by the two-headed arrows. Horizontal dashed lines indicate the average rates to probe alone. The sensitive fiber (panel C) exhibited ‘Kiang's notch’ (Kiang et al., 1969; Ruggero et al., 1996a) at 100 dB SPL. CFs and CF thresholds were 6 kHz, 46 dB SPL (panel B) and 8.48 kHz, 34 dB SPL (panel C).

3.7. Modulation and rate suppression thresholds as a function of spontaneous activity

Modulation threshold did not vary systematically as a function of spontaneous activity (Fig. 12A). In contrast, phase-locking thresholds for low-frequency (suppressor) tones were highly correlated with spontaneous activity. In fibers characterized by high spontaneous rates (> 18 spikes/s), phase-locking threshold exceeded modulation threshold only slightly (by 2.4 dB on average; inset in Fig. 12B). This difference was much larger in fibers with lower spontaneous activity, reaching 24 dB for fibers with spontaneous rate lower than 1 spikes/s and more than 30 dB in nearly silent fibers.

Fig. 12.

Modulation threshold and phase-locking threshold as a function of spontaneous activity. A: The inset indicates the average modulation thresholds and their standard deviation for fibers with low (L: < 1 spikes/s), medium (M: 1–18 spikes/s) and high (H: > 18 spikes/s) spontaneous activity. B: Phase-locking thresholds minus modulation thresholds plotted against spontaneous activity. Phase-locking threshold is the lowest stimulus level at which responses to the suppressor presented alone exceed a vector strength (Goldberg and Brown, 1969) of 0.3. The inset indicates the phase-locking thresholds, normalized to modulation thresholds, for fibers with low, medium and high spontaneous activity. Fibers with spontaneous activity lower than 0.1 spikes/s have been plotted at 0.05 spikes/s in panels A and B. Data points in both panels were randomly shifted vertically within ±1 dB to prevent overlapping. Dashed lines are regression lines.

Fig. 13 addresses the relationship between spontaneous activity and the thresholds for suppressor-tone excitation and for rate suppression. The threshold for rate suppression did not vary systematically with spontaneous activity (Fig. 13A). In contrast, the difference between rate threshold and rate-suppression threshold decreased systematically with increasing spontaneous activity (Fig. 13B). Rate threshold exceeded rate-suppression threshold by 11.6 and 24.3 dB, respectively, in fibers characterized by high (> 18 spikes/s) and low (< 1 spikes/s) spontaneous activity.

Fig. 13.

Rate-suppression and excitatory thresholds for suppressors presented alone as a function of spontaneous rate. A: The inset indicates the average rate-suppression thresholds and their standard deviation for fibers with low (L: < 1 spikes/s), medium (M: 1–18 spikes/s) and high (H: > 18 spikes/s) spontaneous activity. B: Rate-suppression thresholds minus rate thresholds plotted against spontaneous activity. The inset indicates rate thresholds, normalized to rate-suppression thresholds, for fibers with low, medium and high spontaneous activity. Fibers with spontaneous activity lower than 0.1 spikes/s have been plotted at 0.05 spikes/s in panels A and B. Dashed lines are regression lines.

Fig. 14 presents scatter plots of modulation and rate-suppression thresholds against phase-locking and rate thresholds for the suppressor tones presented alone. Except for the fibers with the lowest thresholds (typically those with low CF), modulation and rate thresholds were largely independent of excitatory thresholds. Linear-regression lines fitted to the entire data sample had slopes of 0.2–0.27 dB/dB (indicated at upper right in each panel). Such slopes principally arose from a substantial growth of excitatory thresholds as a function of CF, coupled with a corresponding (but only minimal) growth of suppression thresholds (see Fig. 11).

Fig. 14.

Rate-suppression and modulation thresholds as a function of phase-locking and rate thresholds. The solid lines indicate means computed over 2-dB bands smoothed by 3-point averaging. Data points were randomly shifted horizontally within ±1 dB (A) or within a circle with 1-dB radius (C) to prevent overlapping. The slopes of linear regressions calculated for the entire sample (dashed lines) are given at top right of each panel. The symbols encode spontaneous activity (panel A. upper left).

3.8. The growth of rate suppression as a function of single-tone rate thresholds

To further explore the relation between the growth of suppression as a function of suppressor intensity, on the one hand, and suppression and rate thresholds on the other, we used the ‘fractional response index’ (Abbas and Sachs, 1976). The ‘fractional response index’ is defined as the average driven rate in response to a two-tone (suppressor plus CF tone) stimulus divided by the driven rate to the CF tone alone; i.e.

| (1) |

where Rtt is the rate for the two-tone stimulus, RCF is the rate for the CF tone and SR is the spontaneous rate. Each two-tone phase-intensity matrix was characterized by computing the minimal fractional response index (open circles in Figs. 3C and 15B, C).

The minimal fractional response index was strongly correlated with the difference between rate threshold and rate-suppression threshold (r = −0.717; Fig. 15A). [A slightly smaller correlation (r = −0.625) existed between this index and rate threshold for the suppressor presented alone.] The minimal fractional response index was relatively large for fibers in which suppression thresholds were similar to single-tone thresholds. Conversely, the index was small (zero implying complete suppression) in fibers whose single-tone thresholds exceeded suppression thresholds by 25 dB or more. The correlation between the minimal fractional response index and spontaneous rate was weak (r = 0.311; also see symbols in Fig. 15A).

Cai and Geisler (1996b) used the minimal fractional response index as a putative measure of maximal suppression magnitude for a given combination of (variable level) suppressor and (fixed) CF probe tone. We believe that such usage is only valid in the case of insensitive fibers, in which the thresholds to the suppressor alone are sufficiently high so that the entire dynamic range of suppression may be expressed (e.g. Fig. 15B). In the case of sensitive fibers, whose thresholds for excitatory responses to the suppressor alone are only slightly higher than suppression thresholds (e.g. Fig. 15C), suppression cannot be fully expressed.

The meaning of the minimal fractional response index and its relationship to single-tone thresholds can be gleaned by focusing on the simple case of fibers with near-zero spontaneous activity and similar rates of response to the CF tone alone. For such fibers, Eq. 1 yields a minimal fractional response index that depends monotonically and directly on the response rate to the two-tone stimulus (Rtt). In turn, Rtt varies inversely and monotonically with the amount by which suppressor-alone threshold exceeds rate-suppression threshold. These relations are illustrated in Fig. 15B,C, which present single-tone and two-tone rate-intensity functions for two fibers with similarly low spontaneous activity (B: <0.1 spikes/s; C: 0.2 spikes/s), similarrate-suppression thresholds (B: 78.1 dB SPL; C: 77.4 dB SPL) but substantially different rate thresholds for the suppressor presented alone (B: 108.3 dB SPL; C: 85.4 dB SPL). In the case of the insensitive fiber, suppression threshold was reached at a level much lower than excitation threshold and therefore the index fully reflected the maximal suppression strength. In the case of the more sensitive fiber, however, the growth of suppression was partly masked by the excitatory response to the suppressor tone alone and the resulting minimal fractional response index was large (0.52). In this case, the minimal index was inadequate for estimating the maximal strength of underlying suppression.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of results

Low-frequency (50–400 Hz) tones (‘suppressors’) modulate the responses of chinchilla auditory nerve fibers to near-CF probe tones, producing one or two suppression valleys during each cycle of the suppressor (Figs. 1, 2, 6 and 8).

The suppression valleys lead or lag, by approximately 90 degrees, the near-threshold excitatory phases for the suppressor tone presented alone (Figs. 1, 2, 6 and 8).

Near the threshold of suppression, maximal suppression typically occurs in phase with basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani. At slightly higher intensities, suppression valleys are synchronous with peak displacements of the basilar membrane toward scala tympani and toward scala vestibuli (Figs. 1, 2 and 5–8).

The strength of modulation decreases as a function of increasing suppressor frequency (Figs. 5, 6 and 9).

The strength of modulation decreases as a function of decreasing CF (Figs. 7 and 8).

Modulation and rate-suppression thresholds are very similar (about 70 dB SPL on average; Fig. 10), are independent of spontaneous activity (Figs. 12 and 13), and vary little with fiber CF (Fig. 11) or excitation thresholds for single suppressor tones (Fig. 14).

Phase-locking and rate thresholds for single low-frequency tones exceed substantially the threshold of modulation or rate suppression in the case of high-CF fibers (Fig. 11), especially in those with low spontaneous activity (Fig. 12B). In contrast, both modulation and rate suppression thresholds tend to exceed phase-locking thresholds in low-CF fibers (Fig. 11B).

4.2. Comparison of the present findings with those of other studies in the auditory nerve

A modulating effect of low-frequency suppressor tones on responses to near-CF probe tones can be demonstrated in most auditory nerve fibers of chinchillas (the present study and Ingvarsson, 1981), cats (Sachs and Hubbard, 1981; Cai and Geisler, 1996a,b) and gerbils (Schmiedt, 1982b), as well as in high-CF spiral ganglion neurons in guinea pig (Sellick et al., 1982a). [In their pioneering study in cat, Romahn and Boerger (1978) observed modulation in only 7% of auditory nerve fibers. This may have resulted from insensitivity of their stimulus paradigm and/or from the fact that they only recorded from neurons with CF < 3.4 kHz, in which modulation is weak and modulation thresholds are higher than for excitation by low-frequency tones (Fig. 11).] The features of modulation in the auditory nerve of the chinchilla resemble those previously described for cat and guinea pig but there are some notable discrepancies.

As a rule, modulation by low-frequency tones in chinchilla auditory nerve fibers is characterized by two suppression maxima (Table 1 and Ingvarsson, 1981). Studies in guinea pig (Sellick et al., 1982a; Patuzzi et al., 1984a) and cat (Sachs and Hubbard, 1981) also found biphasic modulation in most neurons. Another study in the cat (Cai and Geisler, 1996a) could demonstrate biphasic suppression in only one third of fibers, but this probably was a result of the frequent use of relatively high-frequency suppressor tones and a fiber sample weighted toward low CFs (recall that modulation strength weakens as a function of decreasing CF and of increasing suppressor frequency: Figs. 6 and 8; see also Table 1).

In chinchilla, suppression phases correspond strictly to phases that are non-excitatory when the suppressor tone is presented alone (Figs. 1–9 and Ingvarsson, 1981), in agreement with the prevalent finding of a study in cat (Cai and Geisler, 1996a). However, other studies of high-CF primary afferents in cat and guinea pig found that “the phase of a suppressor tone which causes instantaneous rate to increase when presented alone caused rate decrease when added to a CF tone” (Sachs and Hubbard, 1981; Sellick et al., 1982a).

In chinchilla fibers, regardless of CF, and also in high-CF ganglion cells in guinea pig (Sellick et al., 1982a; Patuzzi et al., 1984a), maximal suppression at near-threshold levels typically coincides with basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani. In contrast, maximal suppression in cat auditory nerve coincides with peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala vestibuli (Cai and Geisler, 1996a). This result is especially puzzling because it seems inconsistent with the polarity of maximal suppression at the basilar membrane of cat (Rhode and Cooper, 1993), as well as other species (see Section 4.4).

The discrepancies between the features of modulation observed in various auditory nerve studies in chinchillas, cats and guinea pigs may partly reflect genuine species differences. Since the features of modulation are remarkably similar at the basilar membrane in all three species (see Section 4.4), whatever species differences exist must reside in processes central to basilar membrane ‘macromechanics’.

4.3. Comparison of the present findings with inner hair cell data

The present findings are generally consistent with intracellular recordings from inner hair cells (Sellick and Russell, 1979; Patuzzi and Sellick, 1984; Russell and Kössl, 1992a; Cheatham and Dallos, 1992, 1995, 1997) on the assumption that excitation and suppression in auditory nerve fiber responses correspond to depolarization and hyperpolarization, respectively, of receptor potentials. In both inner hair cells and auditory nerve fibers, suppression of near-CF tones by near-threshold low-frequency tones is synchronous with basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani and two episodes of suppression are usually present for higher suppressor levels, as the basilar membrane is displaced toward either scala tympani or scala vestibuli. Modulation in high-CF inner hair cells (e.g. Fig. 6 in Russell and Kössl, 1992a) resembles especially well the present chinchilla neural data in that the hyperpolarization (or suppression) episodes are almost equally prominent for both polarities of basilar membrane displacements.

4.4. Comparison between modulation in high-CF auditory nerve fibers and basal basilar membrane sites

The biphasic modulation pattern that characterizes the suppression of chinchilla auditory nerve fiber responses to CF tones by low-frequency tones (Figs. 1– 4, 6, 8 and 9) closely resembles its counterpart in the vibrations of the basilar membrane at basal sites of the cochleae of chinchilla (Ruggero et al., 1992) and other species (guinea pig: Patuzzi et al, 1984b; Cooper, 1996; Geisler and Nuttall, 1997; cat: Rhode and Cooper, 1993). Peak modulation in neural responses occurs near the middle of the dynamic range of two-tone interaction when the intensity of either the suppressor tone (Figs. 3, 4, 6 and 8) or the probe tone (Fig. 9, bottom right panel) is varied. Appropriately, modulation at the basilar membrane reaches its maximum at moderate intensities of the suppressor or the probe and is less prominent at higher or lower intensities (Figs. 9 and 8, respectively, in Ruggero et al., 1992).

Most studies of modulation at basal sites of the basilar membrane have found that low-frequency tones cause suppression when the basilar membrane is displaced toward either scala tympani or scala vestibuli (Patuzzi et al., 1984b; Cooper, 1996; Rhode and Cooper, 1993; Geisler and Nuttall, 1997). The single exception is a study from our own laboratory (Ruggero et al., 1992) that reported that, at the 3.5-mm site of the chinchilla basilar membrane, maximal suppression of responses to CF tones coincided with peaks of basilar membrane velocity, rather than displacement. In retrospect, it has become clear that this result was artifactual. For low stimulus frequencies, when basilar membrane responses are small and middle ear responses are relatively large, the vibrations of the fluid meniscus overlying the recording site contaminate the laser velocimetry recordings so that these reflect middle-ear, rather than basilar membrane, motion (Cooper and Rhode, 1992, 1996a; Cooper, 1996; Ruggero et al., 1997). Based on several lines of evidence – including comparison of responses to low-frequency tones recorded using laser velocimetry and the Mössbauer technique and the effect on laser-velocimetry recordings of covering the fluid meniscus with a glass window – we estimate that the phases of responses to low-frequency tones reported by Ruggero et al. (1992) must be corrected by about 90 degrees in the lagging direction. Applying this correction brings the phases of maximal suppression at the 3.5-mm site of the chinchilla basilar membrane into agreement with those of basal basilar membrane sites in other species and with the present findings in chinchilla auditory nerve fibers (Fig. 6).

Modulation and rate-suppression thresholds in chinchilla auditory nerve fibers are essentially invariant with respect to spontaneous activity (Figs. 12A and 13A) and vary little as a function of excitatory (rate or phase-locking) thresholds (Fig. 14). This is consistent with the uniformity of the thresholds for rate suppression by low-frequency tones in gerbil (Schmiedt, 1982a) and in cat (Fahey and Allen, 1985; Cai and Geisler 1996b)). Since spontaneous activity and excitatory thresholds are presumably determined at the synapses between afferent terminals and inner hair cells (Liberman, 1982), the uniformity of modulation and rate suppression thresholds in the face of widely varying spontaneous activity and excitatory thresholds implies that low-frequency modulation and suppression arise at a stage of cochlear processing peripheral to synaptic transmission.

A direct comparison between neural and mechanical suppression thresholds is feasible in the chinchilla for CFs (8–10 kHz) close to that of the 3.5-mm cochlear site (Ruggero et al., 1992). For such CFs, modulation thresholds in fibers exhibiting high spontaneous activity (72.6±6.2 dB SPL) are, on average, identical to suppression thresholds at the basilar membrane (72.6 dB SPL; Ruggero et al., 1992). At the basilar membrane in the hook region of the guinea pig cochlea (Cooper, 1996), low-frequency suppression has thresholds of 80–90 dB SPL, about 10 dB higher than those reported for auditory nerve fibers with appropriate CF (Robertson, 1976; Prijs, 1989).

In conclusion: the features of low-frequency modulation and suppression in high-CF cochlear neurons of chinchilla, as well as guinea pig, are strikingly similar to, and probably derive directly from, the pattern of vibration of the basilar membrane at the base of the cochlea. Deciding on whether a similar conclusion applies to modulation and suppression in high-CF fibers of cat will require an explanation of the seemingly conflicting polarity of maximal suppression at the auditory nerve (displacement toward scala vestibuli: Cai and Geisler, 1996a) and at the basilar membrane (displacement toward scala tympani: Rhode and Cooper, 1993).

As is the case for other CF-specific properties of basilar membrane at the base of the cochlea, including high sensitivity, sharp frequency tuning, compressive non-linearity and vulnerability (reviewed by Ruggero, 1992; Patuzzi, 1996; Ruggero et al., 1996b), it is likely that modulation at the basilar membrane results from a feedback relationship involving the outer hair cells (Ruggero and Rich, 1991; Murugasu and Russell, 1996). Such a feedback has been discussed in the context of modulation and rate suppression in several papers (Zwicker, 1979; Patuzzi et al., 1989; Geisler et al., 1990; Geisler, 1992; Cai and Geisler, 1996c).

4.5. Decrease of modulation strength as a function of decreasing CF

For a given suppressor frequency, the strength of modulation in the chinchilla auditory nerve decreases as a function of decreasing CF (Fig. 8), a result consistent with findings for the cat (Cai and Geisler, 1996a). This is also consistent with the fact that the rate of growth of suppression as a function of the level of (low-frequency) suppressors decreases with decreasing CF (Delgutte, 1990). The dependence of modulation and rate suppression on CF suggests that basilar membrane modulation and suppression are weaker in apical cochlear regions. Indeed, mechanical responses in those regions exhibit weak suppression and modulation (Cooper and Rhode, 1996b).

The CF dependence of modulation and suppression may also indicate that the basilar membrane input-output functions for CF tones are more linear (less compressive) at the cochlear apex than at the base. A similar conclusion may be drawn from comparisons of the slopes of auditory nerve fiber responses to CF and low-frequency tones (Cooper and Yates, 1994) and from the fact that the vulnerable tip of tuning curves becomes less distinct as the cochlear apex is approached (Sewell, 1984). Again, the neural findings seem consistent with basilar membrane recordings: mechanical input-output functions for CF tones are much less compressive at the apex of the cochlea than at the base (Rhode and Cooper, 1997).

Although the foregoing evidence suggests that basilar membrane mechanics are more linear at the apex than at the base of the cochlea, definitive conclusions will have to wait until a larger body of work confirms the initial basilar membrane measurements at the apex of the cochlea (Cooper and Rhode, 1996b; Rhode and Cooper, 1997). In particular, given the well known vulnerability of basilar membrane responses, it is important to ascertain whether the available apical data are vitiated by surgically-induced damage and thus unrepresentative of responses in normal cochleae. Such damage might account for the apparent lack of uniformity of mechanical modulation phases (Cooper and Rhode, 1996b), which contrasts with the findings of all basilar membrane studies at the cochlear base.

4.6. The difference between suppression and excitation thresholds in relation to characteristic frequency

Modulation and rate-suppression thresholds in chinchilla are only weakly dependent on CF (Fig. 11). In contrast, both rate and phase-locking thresholds for low-frequency (suppressor) tones presented alone increase as a function of increasing CF (Fig. 11; see also Fig. 14 of Ruggero and Rich, 1987 and Fig. 8 of Ruggero et al., 1996a). This difference may be related to the increasing separation between the frequency of the suppressor tone and CF. Such frequency dependence suggests that a (high-pass) frequency filter is interposed between the site of origin of modulation and suppression and the site where auditory nerve excitation thresholds are determined (see Section 4.8).

The present investigation, as well as others (Costalupes et al., 1987; Cai and Geisler, 1996a,b), show that rate suppression by low-frequency tones is essentially universal, regardless of fiber CF. In contrast, some studies have concluded that such suppression is uncommon in low-CF fibers (Harris, 1979; Fahey and Allen, 1985; Prijs, 1989). One likely reason for the paucity of ‘low-side’ rate suppression observed in these studies is that excitatory thresholds predominantly exceed suppression threshold in fibers with CF > 2 kHz, whereas the reverse is often true for low-CF fibers (Fig. 11). Thus, a search for suppression using only non-excitatory low-frequency tones is inadequate.

4.7. Decrease of modulation strength as a function of increasing suppressor frequency

In the auditory nerves of chinchilla (Fig. 6 and Table 1), as well as cat (Cai and Geisler, 1996a), the strength of modulation decreases as a function of increasing suppressor-tone frequency. This frequency dependence probably does not arise in basilar membrane responses. At the basilar membranes of chinchilla and cat, substantial modulation has been measured for suppressor frequencies of 500 and 1000 Hz, respectively (see Figs. 7–9 of Ruggero et al., 1992, and Fig. 9 of Rhode and Cooper, 1993). Most conclusively, modulation has been observed for suppressor frequencies as high as 7 kHz at the hook region of the guinea pig cochlea (Cooper, 1996).

Increasing suppressor frequency is accompanied both by a decrease in modulation strength and by a reduction in the magnitude of phase locking to the suppressor tone. However, the decrease in the magnitude of phase locking cannot account for the change in modulation strength. This is made evident by comparing net suppression responses (Fig. 6, left column) with the phase-intensity matrices for single tones with frequency twice that of the suppressor tone (Fig. 5, left column). The frequency dependence of modulation may be a counterpart of a similar phenomenon observed in the phase locking to the envelope of sinusoidally amplitude modulated CF tones in high-CF auditory nerve fibers (Joris and Yin, 1992). This is reasonable, since at the input to the inner hair cell the effect of the suppressor tone must appear as an amplitude modulation of the probe tone. The processes that ‘low-pass filter’ the modulation envelope probably reside in the inner hair cell (and/or its synapses) but must be at least partly independent from those that limit the frequency range of phase locking in responses to single tones (Palmer and Russell, 1986; Kidd and Weiss, 1990).

4.8. Is there a synaptic suppression mechanism that is especially prominent in fibers with low spontaneous activity?

At the basilar membrane, suppression by low-frequency tones may require suppressor intensities such that the displacement response to the two-tone stimulus is larger than the displacement response to the CF probe tone alone (Ruggero et al., 1992; Cooper, 1996; Geisler and Nuttall, 1997). Cai and Geisler (1996b) contrasted this aspect of basilar membrane suppression with low-frequency suppression in auditory nerve fibers, whose responses to two-tone stimuli may be substantially smaller than the response to the CF tone presented alone (e.g. Fig. 4; see also Fahey and Allen, 1985, and Cai and Geisler, 1996b). Cai and Geisler (1996b) also argued that the strength of neural suppression varies as a function of fiber spontaneous activity and concluded that there must exist a suppressive mechanism at the inner hair cell synapses with primary afferents, and that this mechanism is strongest in affer-ents with low spontaneous activity. We disagree with these conclusions.

The argument of Cai and Geisler (1996b) in favor of a synaptic suppressive mechanism is based on the assumption that, for any given auditory nerve fiber, excitatory thresholds correspond to a constant basilar membrane displacement, regardless of stimulus frequency. In fact, however, there is evidence that a ‘second filter’ is interposed between basilar membrane displacement, on the one hand, and inner hair cell depolarization or neural excitation, on the other. Such a high-pass filter is evident in the AC receptor potentials of inner hair cells, which at low frequencies (< 500 Hz or so) are proportional to, and in phase with, basilar membrane velocity (Sellick and Russell, 1980; Nuttall et al., 1981; Dallos and Santos-Sacchi, 1983; Russell and Sellick, 1983). We suggest that some form of high-pass filtering extends to relatively high frequencies, perhaps CF, thus permitting suppression to be induced by non-excitatory low-frequency tones (Ruggero et al., 1992, p. 1096; Cooper, 1996, pp. 3095–3096; Cheatham and Dallos, 1997, p. 208). The present data are consistent with the existence of a high-pass filter, inasmuch as: (1) the difference between the thresholds of excitation and modulation tends to grow with decreasing suppressor frequency (at a rate of 2.8 dB/octave; see Section 3.6); and (2) responses to paired tones exhibit excitation ridges in phase with basilar membrane velocity and suppression troughs in phase with basilar membrane displacement (Figs. 5–8).

There are other data favoring this viewpoint. (1) At the 8–10 kHz site of the chinchilla cochlea, neural thresholds follow a course intermediate between basilar membrane isovelocity and isodisplacement over a range of frequencies spanning more than two decades (Fig. 3 of Ruggero et al, 1986b, and Fig. 22 of Ruggero et al., 1990). (2) At the 17-kHz site of the guinea pig cochlea, inner hair cell tuning curves display tip-to-tail ratios that exceed by 10–15 dB those of either isovelocity or isodisplacement basilar membrane tuning curves (Sellick et al., 1983). (3) At the same site, auditory nerve thresholds correspond to a constant basilar membrane velocity (Sellick et al., 1982b). [However, the same data have also been interpreted as favoring a closer match between neural thresholds and a constant basilar membrane displacement (Neely and Kim, 1983).] (4) In the first study of suppression in inner hair cells, Sellick and Russell (1979) found that the levels of isosuppression contours are much lower than those of isoresponse contours for single tones (by at least 20 dB for frequencies well below CF). (5) At the 18-kHz site of the guinea pig cochlea, the inner hair cell tip-to-tail ratios exceed those of the outer hair cell (or of basilar membrane displacement) by more than 20 dB (Russell and Kössl, 1992b; Russell et al., 1995; however, see also Cody and Russell, 1987).

When coupled with synaptic insensitivity, a hypothetical high-pass filter interposed between basilar membrane vibration and the receptor potentials of inner hair cells may well account fully for modulation and suppression by non-excitatory tones. In addition, it is possible that inner hair cells also possess an adaptation mechanism that produces additional suppression of the DC response to high-frequency probe tones (Zeddies and Siegel, 1996).

Cai and Geisler (1996b) argued that their hypothesized synaptic suppression mechanism is especially strong in fibers with low spontaneous activity because, they claimed, those fibers exhibit the greatest suppression strength, as in the extreme case of complete suppression (Figs. 4 and 15B). We dispute their argument on two grounds. Firstly, as discussed above, complete suppression merely requires a high-pass filter interposed between basilar membrane vibration and the generation of inner hair cell receptor potentials. When such filtering is coupled with sufficient fiber insensitivity, complete suppression results (Fig. 15B). Thus, although there is a need to explain why spontaneous activity is negatively correlated with sensitivity (in cat: Liberman, 1978; in chinchilla: Ruggero, 1978; Salvi et al., 1982; Temchin et al., 1997; in gerbil: Schmiedt, 1989; Ohlemiller and Echteler, 1990), it is redundant to endow the synapses of fibers exhibiting low-spontaneous activity with a mechanism distinct from that which produces their insensitivity. Secondly, in our opinion Cai and Geisler (1996b) failed to demonstrate that there is a negative correlation between suppression strength and fiber spontaneous activity. This is because they (incorrectly) used the ‘minimal fractional response index’ is an indicator of suppression strength. In fact, as we show in Section 3.8, the ‘minimal fractional response index’ is a measure of the amount by which excitatory threshold exceeds suppression threshold1.

4.9. Conclusions

In auditory nerve fibers of chinchilla, low-frequency tones cause rate suppression and periodic modulation of responses to CF tones. Irrespective of CF or other fiber properties, maximal suppression is usually synchronous with peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala tympani at near-threshold levels and also, at higher intensities, with peak basilar membrane displacement toward scala vestibuli. This pattern of modulation closely resembles that seen at a high-CF site of the chinchilla basilar membrane. This resemblance, as well as the independence of modulation and rate-suppression thresholds on spontaneous activity and their similarity to modulation thresholds at the basilar membrane, support a basilar membrane origin of low-frequency modulation and suppression. Modulation strength diminishes with decreases in CF, suggesting that basilar membrane modulation becomes weaker as the cochlear apex is approached. Modulation strength also weakens as a function of increasing suppressor frequency, probably reflecting inner hair cell and/or synaptic processes.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Mary Ann Cheatham, C. Daniel Geisler and Anna Schroder for their comments on previous versions of the manuscript. We were supported by Grants 5-P01-DC-00110-22 and 2-R01-DC-00419-10 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

Footnotes

Cai and Geisler (1996b) devised and applied a putative measure of the strength of modulation, the ‘relative response index’. This was computed by dividing the peak amplitude of the period histogram for the response to the two-tone stimulus by the peak amplitude of the period histogram for the response to the probe tone alone “at the suppressor intensity for which the two-tone rate was minimum” (Cai and Geisler, 1996b). We believe that, much as in the case of the ‘fractional response index’, the ‘relative response index’ does not measure modulation strength but rather the amount by which phase-locking threshold exceeds modulation threshold. Specifically, the data of Figs. 3, 4, 6 and 8 show that, at the lowest intensities at which the normalized rate difference reaches zero (corresponding to the minima of the two-tone rate-intensity functions; compare panels C and D of Fig. 3), there is no modulation and the two-tone responses are dominated by the suppressor tone. In other words, the ‘relative response index’ measures excitatory thresholds (relative to suppression threshold), rather than modulation strength.

References

- Abbas PJ, Sachs MB. Two-tone suppression in auditory nerve fibers: extension of a stimulus-response relationship. J Acoust Soc Am. 1976;59:112–122. doi: 10.1121/1.380841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Geisler CD. Suppression in auditory nerve fibers of cats using low-side suppressors. I. Temporal aspects. Hear Res. 1996a;96:94–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Geisler CD. Suppression in auditory nerve fibers of cats using low-side suppressors. II. Effects of spontaneous rates. Hear Res. 1996b;96:113–125. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Geisler CD. Suppression in auditory nerve fibers of cats using low-side suppressors. III. Model results. Hear Res. 1996c;96:126–140. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham MA, Dallos P. Two-tone suppression in inner hair cell responses: correlates of rate suppression in the auditory nerve. Hear Res. 1992;60:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90052-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham MA, Dallos P. Origins of rate versus synchrony suppression: an evaluation based on two-tone interactions observed in mammalian IHCs. In: Manley GA, Klump GM, Köppl C, Fasti H, Oeckinghaus H, editors. Advances in Hearing Research. World Scientific; Singapore: 1995. pp. 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham MA, Dallos P. Low-frequency modulation of IHC and OC responses in the guinea pig cochlea. Hear Res. 1997;108:191–212. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody AR, Russell IJ. The responses of hair cells in the basal turn of the guinea-pig cochlea to tones. J Physiol (Lond) 1987;383:551–569. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper NP. Two-tone suppression in cochlear mechanics. J Acoust Soc Am. 1996;99:3087–3098. doi: 10.1121/1.414795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]