Abstract

Background and Objectives

Contingency management (CM) interventions are efficacious in treating cocaine abusing methadone patients, but few studies have examined the effect of age on treatment outcomes in this population. This study evaluated the impact of age on treatment outcomes in cocaine abusing methadone patients.

Methods

Data were analyzed from 189 patients enrolled in one of three randomized studies that evaluated the efficacy of CM versus standard care (SC) treatment.

Results

Age was associated with some demographics and drug use characteristics including racial composition, education, and methadone dose. Primary drug abuse treatment outcomes did not vary across age groups, but CM had a greater benefit for engendering longer durations of abstinence in the middle/older and older age groups compared to the younger age groups. At the 6-month follow-up, submission of a cocaine positive urine sample was predicted by submission of a cocaine positive sample at intake, higher methadone doses, and assignment to SC rather than CM treatment.

Conclusions and Scientific Significance

As substance abusers are living longer, examination of the efficacy of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments specifically within older age groups may lead to a better understanding of subpopulations for whom enhanced treatments such as CM are warranted.

The number of older substance abusers is increasing rapidly, along with the number of older adults requiring treatment for substance use.1–3 Older adults presenting for cocaine treatment increased 1.5 fold between 1992 and 2008, and older substance abusers receiving opioid substitution therapy rose over 2.5 fold in this same time frame.3 Despite the growing prevalence of older substance abusers, there is a dearth of research related to aging in cocaine using methadone patients. Further investigation in this population is needed, especially in regards to evaluating age-related differences in treatment response.

Older patients seeking drug abuse treatment may have unique characteristics and treatment needs compared to their younger counterparts. In a study of almost 400 patients seeking psychosocial treatment for cocaine abuse, individuals in the oldest age group were more likely to be female and African American than patients in the youngest age group.4 In addition, older substance abusers commonly have more prominent and severe health related problems compared to their younger counterparts,4–7 and drug use may exacerbate existing medical problems8,9 and have more severe consequences in older adults.10,11 These findings have been extended to older methadone patients as well; older methadone patients evidenced significantly more medical problems and poorer health compared to population norms of the same age group as well as when compared to younger methadone patients.12–14

On the other hand, older substance abusers may exhibit certain protective factors related to substance abuse problems. Older patients are more likely to be married12,15 and tend to have fewer legal difficulties4,7,16 than their younger counterparts. Lemke and Moos5 suggested that older substance abusers reported having more close friends, better social support, and fewer friends with substance abuse problems. In addition, some studies found older compared with younger substance-abusing patients had a lower prevalence of a comorbid psychiatric disorder, fewer psychological symptoms, and less psychiatric distress.4–6,17 However, in a study of opioid maintained patients, both older and younger patients had high rates of lifetime psychiatric diagnoses compared to population norms, with no differences between the age groups.13

Given that aging is often associated with unique psychosocial issues, it is not surprising that age may impact substance abuse treatment outcomes. Although younger substance abusers are more likely to initiate treatment,18 older and middle aged adults are less likely to drop out of treatment4,15,19,20 and respond to treatment equally well, if not better than, younger adults.5,21–23 Further, due to age differences associated with substance abuse, certain treatment strategies may be more appropriate for older age groups. The Center for Substance Abuse Treatment24,25 recommends treatment approaches that address age-specific psychological, social, and health concerns for older substance abusers. Specialized treatment approaches may be warranted in older methadone maintenance patients who abuse cocaine, as cocaine use itself is related to poor methadone treatment outcomes26–28 and health problems,29,30,31 which may be exacerbated in older adult cocaine abusing methadone patients.

Substance abuse can be effectively treated via contingency management (CM) in a wide range of substance-abusing populations. CM is based on basic behavioral principles including rearranging the environment to readily detect drug abstinence, and providing tangible reinforcers upon evidence of abstinence. A recent meta-analysis finds CM to be the psychosocial intervention with the largest effect size in treating substance abuse32 and it is particularly effective in stimulant abusing methadone patients.33,34 The National Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (CTN) study of CM35 found that stimulant-abusing methadone patients assigned to CM submitted an average of 54.5% negative samples during treatment versus an average of only 38.7% negative samples for those assigned to standard care (SC).

A few studies have examined age effects in CM studies. In the CTN studies of CM, Peirce and colleagues36 found a non-significant trend toward patients over the age of 40 submitting more stimulant-negative samples than younger patients, but only among stimulant abusing patients receiving entirely psychosocial (non-methadone) treatment. Further, this study did not evaluate whether persons of different ages responded differently to CM and SC. In a study of cocaine abusing outpatients drawn entirely from psychosocial settings, CM improved treatment outcomes in all age groups, but older individuals benefited less from CM than younger persons in terms of retention and abstinence outcomes.4 These results appeared to reflect ceiling effects, as older patients in that sample remained in treatment longer, and the vast majority of urine toxicology screens tested negative. Cocaine abusing methadone patients, on the other hand, have much lower overall rates of cocaine abstinence during treatment.

The purpose of this study was to examine main and interactive effects of age on outcomes in cocaine abusing methadone maintenance patients receiving CM with SC or SC alone. We conducted a retrospective analysis of three randomized studies of cocaine abusing methadone patients.37–39 To facilitate interpretation of age effects, patients were divided into quartiles based on age. Baseline characteristics and primary treatment outcomes were compared across the age groups. We anticipated that the oldest age group may differ from the younger groups with respect to some demographic characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity, marital status), and the oldest age group was expected to experience more medical problems. We also hypothesized that age groups may differ with respect to responsivity to treatment. If longest duration of cocaine abstinence or proportions of drug negative urine samples submitted varies depending on age or its interaction with treatment condition, these data may suggest that interventions ought to be targeted toward particular age groups.

Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from 193 cocaine abusing methadone patients from one of three randomized studies that all shared the goal of evaluating the efficacy of CM plus SC versus SC alone.37–39 The three trials were conducted in the same community clinic, were of the same duration, and used the same assessment instruments. A high level of consistency across the trials provided the rationale for combining these studies for the purposes of the present analyses.

Inclusion criteria across all trials included age ≥ 18, past year diagnosis of cocaine abuse or dependence, stable methadone dose for at least 1 month, and English speaking. Exclusion criteria were severe dementia, uncontrolled psychiatric disorder (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), or in recovery for pathological gambling. All patients provided written informed consent, approved by University of Connecticut School of Medicine Intuitional Review Board. Of the full sample of 193, four patients were excluded from these analyses due to one or more missing data points at baseline, leaving 189 patients for analyses.

Procedures

Following informed consent, participants were administered assessments to ascertain demographic information, drug use, and treatment histories. Patients also completed drug use modules adapted from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV40 as well as the Addiction Severity Index (ASI).41 The ASI assesses psychosocial functioning across seven domains (alcohol use, drug use, medical, employment, legal, family/social relationships, and psychiatric), with scores ranging from 0 to 1. Higher scores in each domain indicate more severe problems.

Participants in all three trials were randomly assigned to a 12-week SC or 12-week CM plus SC condition. As the original studies37–39 provide detailed explanations of the treatment conditions, they are only briefly outlined.

Standard Care (SC) was similar across all studies and consisted of daily methadone doses, weekly group therapy, monthly individual counseling, and frequent sample monitoring, with patients submitting up to 36 urine samples that research assistants collected and screened for opioids and cocaine using Ontrak TesTstiks (Varian, Inc., Walnut Creek, CA). Samples were observed, whenever possible. In all trials, patients received verbal reinforcement for submission of negative samples, and in one study,39 participants also received small incentives to encourage sample submission. Participation in the studies did not affect SC.

Contingency management

Patients assigned to the CM condition received the same treatment as the SC condition and could additionally earn reinforcement for completion of target behaviors. In all studies, participants earned at least one draw from a bowl with a chance of winning a prize for each cocaine negative urine sample, and bonus draws for consecutive abstinence. Unexcused, missed, or positive specimens ended a period of abstinence and reset draws to a low level. The prize bowls contained 250 or 500 slips of paper depending on the study; half were non-winning slips which said “good job,” and half were winning slips. Most (about 43%) of the winning slips were small prizes worth about $1, about 6% were for large prizes worth around $20, and one slip was for a jumbo prize worth up to $100. Overall average maximum value of prizes ranged from $350 to $500 depending on the study.

Patients in the Petry et al.39 study also received reinforcement, on an independent schedule, for group therapy attendance. In the Petry et al.37 study, a second CM condition was included that reinforced cocaine abstinence with vouchers, rather than prizes. Participants in this condition received $3 for the first cocaine negative sample and this amount increased by $3 for each consecutive negative sample. No significant differences between those assigned to the voucher and prize CM conditions provided the rationale for combining those groups for the analyses in the present report.

Data Analysis

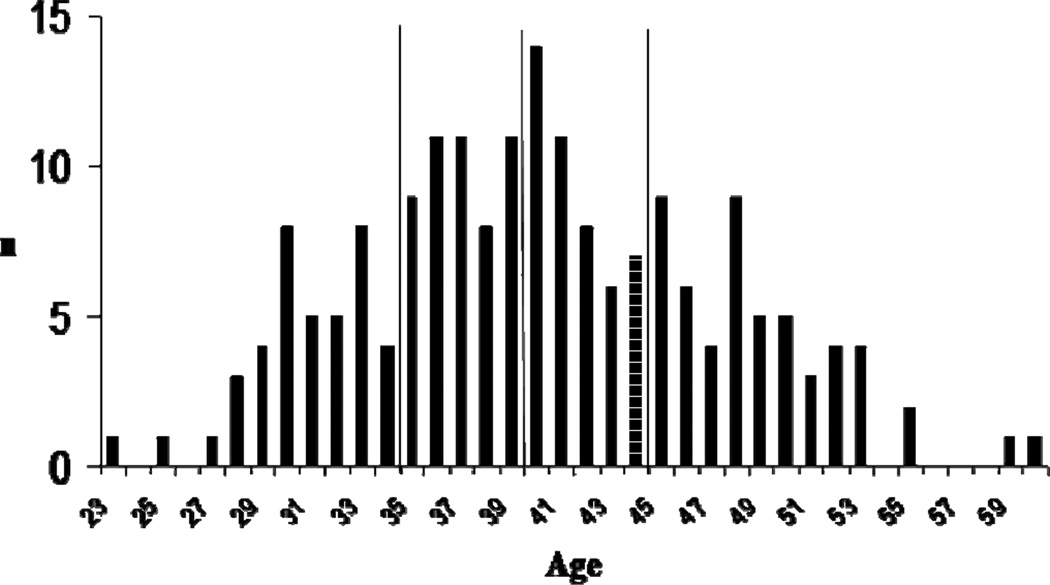

For ease of interpretation of effects of age, patients were divided into quartiles based on age at time of study initiation: ≤ 34, 35–39, 40–44 or ≥45 years. The actual age distributions of patients are shown in Figure 1. Analyses compared the four age groups with respect to baseline characteristics including demographics, drug abuse severity, and psychosocial functioning (severity of family, legal, medical problems, etc.). Chi squared tests and F tests evaluated differences between the age groups for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Although not all variables were normally distributed, these tests are robust to departures from normality when the sample size is large.42 Baseline variables that differed significantly between age groups, or are linked with treatment outcomes (e.g., study intake urine toxicology result, study), were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of patients. Vertical lines represent division of quartiles.

Multivariate analyses of covariance evaluated the effects of age group and treatment condition (SC or CM) on drug abuse outcomes, after controlling for methadone dose, education, study, race, and study intake urine toxicology result for cocaine (positive or negative). Both main effects of age and its interaction with treatment condition were examined to ascertain whether the age groups respond differentially to the treatment conditions. The two primary outcomes were available from all randomized patients: longest durations of cocaine abstinence (LDA) as determined by urinalysis testing, and proportion of cocaine negative urine samples submitted. LDA was defined as the greatest number of consecutive weeks of objectively verified abstinence from cocaine during the treatment period (range 0 – 12 weeks). Positive samples, missed samples, or unexcused absences on a testing day broke the string of abstinence in all three trials. Proportion of samples negative for cocaine was calculated with the number of samples submitted in the denominator, so that missing samples did not impact this variable. On average (SD), 21.8 (6.1) samples were provided, which did not differ by treatment condition or age group (ps > .90).

Secondary analyses examined post-treatment outcomes. All patients were compensated to participate in follow-ups 6 months after initiating the study, and the overall follow-up rate was 85.3% (n = 162) which did not differ by study, treatment condition, or age group (ps > .10). Logistic regressions evaluated predictors of cocaine use at the follow-up. Step one included study, race, study intake urine toxicology result, age category, methadone dose, and education; treatment condition was added in Step two, and the interaction between treatment condition and age category in Step three. All variables except for methadone dose and education were included as categorical variables. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented for significant predictors of outcomes.

Results

Table 1 shows characteristics across the four age categories. Ethnicity, years of education, and methadone dose differed significantly by age group. Post-hoc tests revealed that the 45 and older and 35–39 year age groups completed more education than the youngest group, the youngest group received a larger methadone dose than the 35–39 year group, and the youngest group was least likely to be African American and most likely to be Hispanic. No differences were evident for other demographics, psychosocial domains, or drug use variables.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and baseline variables

| Variable | Age (years) | Statistical test | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 34 (n= 40) |

35–39 (n= 50) |

40–44 (n= 46) |

≥ 45 (n= 53) |

|||

| Treatment group, n (%) | X2(3) = 1.51 | .68 | ||||

| Contingency Management | 25 (62.5) | 26 (52.0) | 28 (60.9) | 33 (62.3) | ||

| Standard Care | 15 (37.5) | 24 (48.0) | 18 (39.1) | 20 (37.7) | ||

| Studies, n (%) | X2(6) = 7.99 | .24 | ||||

| Petry et al.39 | 18 (45.0) | 20 (40.0) | 21 (45.7) | 18 (34.0) | ||

| Petry & Martin38 | 9 (22.5) | 14 (28.0) | 10 (21.7) | 7 (13.2) | ||

| Petry et al.37 | 13 (32.5) | 16 (32.0) | 15 (32.6) | 28 (52.8) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | X2(6) = 34.12 | .00 | ||||

| African American | 4 (10.0) | 27 (54.0) | 16 (34.8) | 29 (54.7) | ||

| Caucasian | 6 (15.0) | 7 (14.0) | 9 (19.6) | 13 (24.5) | ||

| Hispanic | 30 (75.0) | 16 (32.0) | 21 (45.7) | 11 (20.8) | ||

| Male gender, n (%) | 13 (32.5) | 20 (40.0) | 11 (23.9) | 19 (35.8) | X2(3) = 3.00 | .39 |

| Past year income | $7,688 ($8,320) | $10,542 ($11,323) | $6,449 ($4,203) | $9,850 ($9,210) | F(3,181) = 2.18 | .09 |

| Years of education | 10.2 (2.1) | 11.1 (1.8) | 10.9 (1.6) | 11.4 (2.3) | F(3,185) = 3.19 | .03 |

| Methadone dose (mg) | 82.3 (30.9) | 66.3 (24.5) | 76.2 (27.5) | 78.7 (29.9) | F(3,185) = 2.80 | .04 |

| Past month days of use | ||||||

| Cocaine | 9.7 (11.2) | 10.5 (11.4) | 8.8 (10.4) | 10.9 (11.0) | F(3,185) = 0.37 | .77 |

| Cannabis | 3.8 (9.0) | 3.0 (8.3) | 1.1 (4.1) | 0.9 (3.1) | F(3,185) = 2.19 | .09 |

| Alcohol | 5.1 (9.4) | 2.2 (4.2) | 2.6 (5.9) | 3.0 (6.4) | F(3,185) = 1.61 | .19 |

| Opioids | 1.7 (5.2) | 1.4 (3.1) | 0.8 (1.3) | 1.4 (3.5) | F(3,185) = 0.56 | .64 |

| Study intake urine sample negative | ||||||

| For cocaine, n (%) | 17 (42.5) | 18 (36.0) | 19 (41.3) | 14 (26.4) | X2(3) = 3.41 | .33 |

| For opioids, n (%) | 31 (77.5) | 35 (70.0) | 36 (78.3) | 41 (77.4) | X2(3) = 1.20 | .75 |

| Addiction Severity Index scores | ||||||

| Medical | 0.24 (0.32) | 0.19 (0.32) | 0.33 (0.35) | 0.32 (0.37) | F(3,185) = 1.98 | .12 |

| Employment | 0.85 (0.24) | 0.81 (0.27) | 0.81 (0.24) | 0.85 (0.22) | F(3,185) = 0.51 | .67 |

| Alcohol | 0.11 (0.23) | 0.07 (0.14) | 0.06 (0.11) | 0.08 (0.16) | F(3,185) = 0.80 | .50 |

| Drug | 0.22 (0.13) | 0.20 (0.15) | 0.18 (0.13) | 0.20 (0.12) | F(3,185) = 0.62 | .60 |

| Legal | 0.08 (0.15) | 0.08 (0.18) | 0.07 (0.14) | 0.07 (0.15) | F(3,185) = 0.07 | .97 |

| Family/social | 0.11 (0.19) | 0.13 (0.20) | 0.10 (0.14) | 0.09 (0.18) | F(3,185) = 0.56 | .65 |

| Psychiatric | 0.24 (0.26) | 0.22 (0.22) | 0.24 (0.24) | 0.16 (0.20) | F(3,185) = 1.38 | .25 |

Values represent means and standard deviations unless otherwise indicated.

Significant between group difference, p < .05.

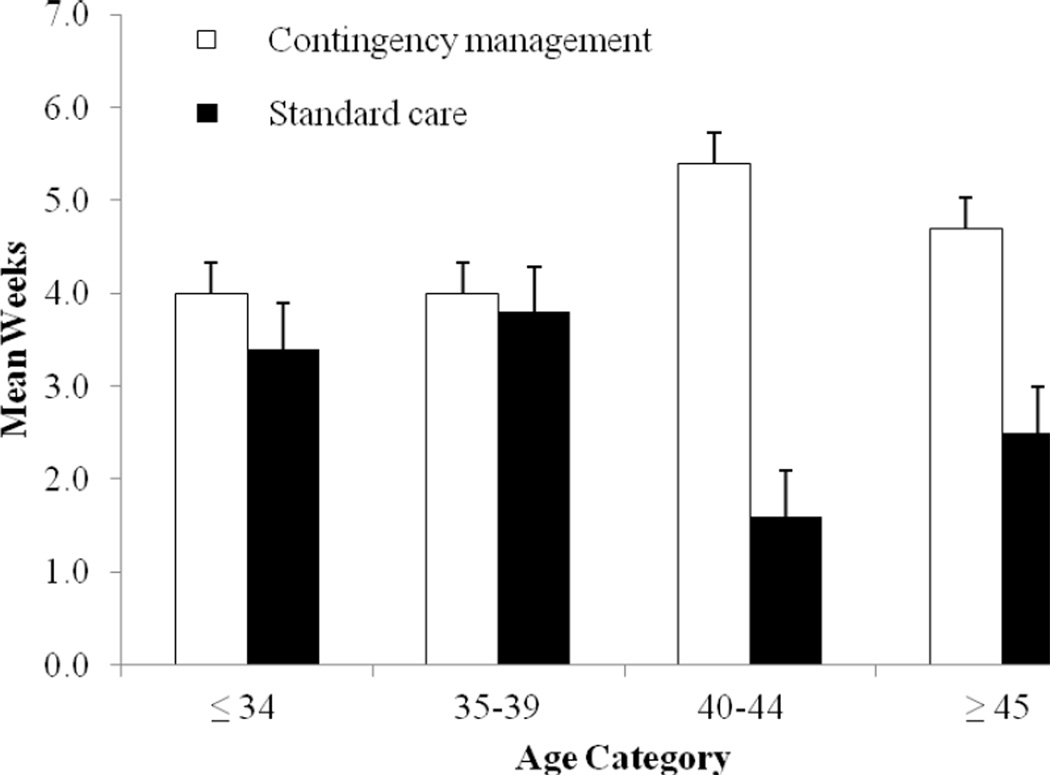

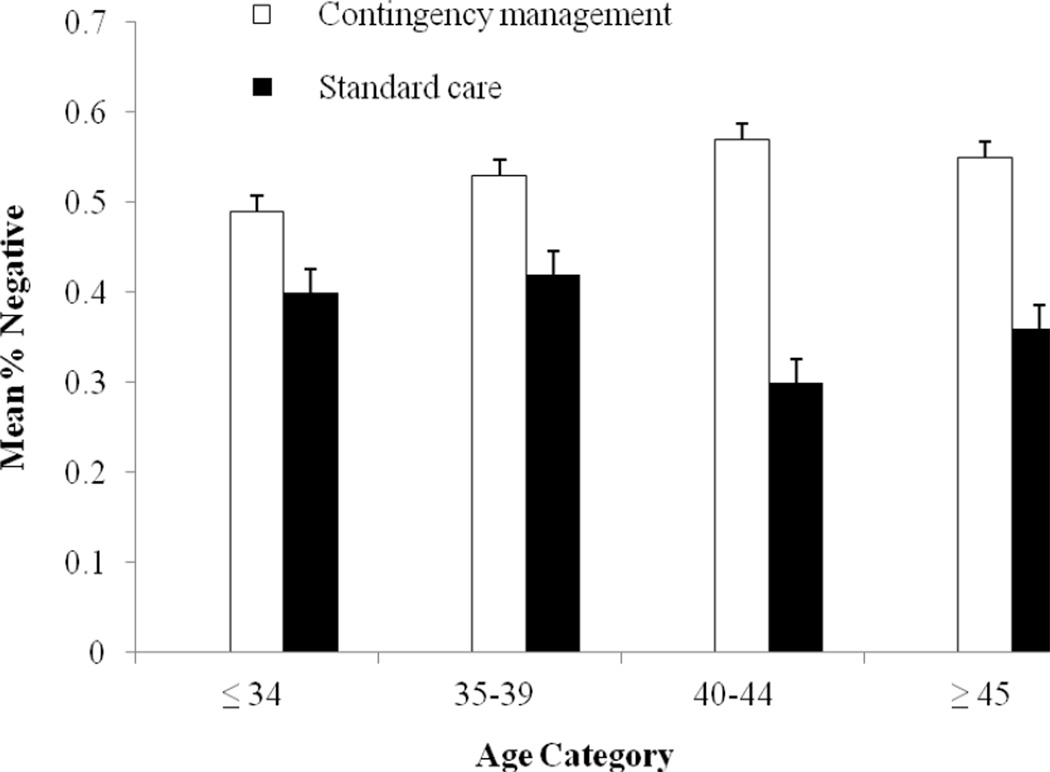

Multivariate analyses, controlling for treatment condition, study, methadone dose, race, and study intake urine toxicology result, revealed a significant age group by treatment condition interaction for LDA, F (3,175) = 2.78, p < .05 (Figure 2). The superiority of CM over SC in enhancing the duration of abstinence achieved resided largely among the older half of the sample. The interaction effect was not significant for proportion of negative samples submitted, F (3,175) = 0.83, p = .48 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Longest duration of cocaine abstinence (in weeks) by age category and treatment condition. Values represent adjusted means and standard errors. Age by treatment condition interaction effect is significant, p < .05.

Figure 3.

Proportions of negative cocaine samples submitted by age category and treatment condition. Values represent adjusted means and standard errors.

Some other variables also impacted outcomes. Study was significantly related to LDA (F (3,175) = 6.64, p < .01), and study intake urine toxicology result (F (1,175) = 100.33 and 105.65, ps < .001) and treatment condition (F (1,175) = 11.55 and 12.43, ps < .001) were associated with both LDA and proportion of negative samples submitted, respectively. The LDA in the Petry et al.37 study was higher than that in the Petry & Martin38 and Petry et al.39 studies, with means (SE) of 4.9 (0.4), 3.0 (0.6), and 3.1 (0.4), respectively. A negative study intake toxicology screen was associated with greater LDA, with means (SE) of 6.4 (0.4) versus 1.0 (0.4) for those who initiated treatment with negative and positive samples, respectively, and higher proportions of negative samples during treatment, 70.7% (3.8) versus 19.9% (3.3), respectively. Finally, randomization to a CM treatment was associated with greater LDA than randomization to SC, 4.5 (0.3) versus 2.8 (0.4) weeks, and greater proportion of negative samples during treatment, 53.5% (3.2) versus 37.1% (3.7).

Overall, 54.9% of patients (89 of 162) submitted a sample positive for cocaine at the month 6 follow-up. Within age categories, the percentages (and n’s) submitting cocaine-positive samples were 47.1% (16 of 34), 58.1% (25 of 43), 55.0% (22 of 40), and 57.8% (26 of 45), for the youngest to oldest categories, respectively. Step one of the logistic regression predicting cocaine use at the follow-up was significant, χ2(10) = 44.16, p < .001, correctly classifying 72.8% of the cases. Study, methadone dose, and initial toxicology result were significantly associated with submission of a positive sample at the follow-up. Patients in the Petry et al.37 study were significantly less likely than those in the Petry et al.39 study to submit a positive sample, OR = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.12 – 0.71, Beta (SE) = −1.22 (0.45), Wald = 7.38, p < .01. A higher methadone dose was associated with a greater likelihood of a positive cocaine sample at month 6, OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.00 – 1.03, Beta (SE) = 0.02 (0.01), Wald = 5.20, p = .02, and submission of a negative cocaine sample at study intake was related to a reduced probability of submission of a cocaine positive sample at month 6, OR = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.80 – 0.37, Beta (SE) = −1.76 (.39), Wald = 20.30, p < .001. Age was not related to cocaine use at month 6, p = .72.

Inclusion of treatment condition in Step two was significant, χ2(1) = 4.03, p = .04, and improved the model, χ2(11) = 48.19, p = .001, with 74.7% of cases correctly classified. Results from this model are shown in Table 2. Again, study, methadone dose, and initial urine toxicology result were associated with submission of a cocaine positive sample at month 6. After controlling for these variables, randomization to the CM condition was associated with a 55% reduced chance of submission of a cocaine positive sample at the post-treatment follow-up.

Table 2.

Predictors of cocaine use at 6-month follow-up evaluation

| Variable | β (SE) | Wald Z | p | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study* | ||||

| Petry et al.37 | −1.04 (.46) | 5.20 | <.05 | 0.35 (0.14, 0.86) |

| Petry & Martin38 | −.52 (.51) | 1.05 | .31 | 0.59 (0.22, 1.61) |

| Race† | ||||

| Caucasian | −.31 (.57) | 0.29 | .59 | 0.74 (0.24, 2.26) |

| African American | .24 (.49) | 0.25 | .62 | 1.27 (0.49, 3.31) |

| Education | −.05 (.11) | 0.19 | .66 | 0.96 (0.78, 1.17) |

| Methadone dose | .02 (.01) | 4.61 | <.05 | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) |

| Cocaine negative sample at study intake | −1.80 (.40) | 20.25 | <.001 | 0.17 (0.08, 0.36) |

| Age‡ | ||||

| <35 | −.47 (.61) | 0.59 | .44 | 0.63 (0.19, 2.06) |

| 35–40 | .07 (.53) | 0.02 | .90 | 1.07 (0.38, 3.00) |

| 41–44 | .12 (.54) | 0.05 | .82 | 1.13 (0.39, 3.27) |

| Contingency management treatment condition§ | −.81 (.41) | 3.91 | <.05 | 0.45 (0.20, 0.99) |

Petry et al.39 is the reference category.

Hispanic race is the reference category.

Age ≥ 45 years is the reference category.

Standard care is the reference category.

Inclusion of Step three, with the age group by treatment condition interaction term, was not significant, p > .94. Therefore, this step was excluded from the model. Results were similar when age was included as a continuous, rather than categorical, variable (data not shown).

Discussion

One aim of this study was to examine age related differences in characteristics of cocaine abusing methadone patients. Some differences emerged with respect to racial composition and education, and the youngest cohort received higher methadone doses. In contrast to existing research,4–7,12,43 older and younger substance abusers did not differ with respect to severity of medical or psychosocial problems. These discrepancies across studies may relate to the use of different instruments to assess problems and evaluation in different patient populations.

Primary treatment outcomes did not vary across age groups, but a significant age by treatment condition interaction was found with respect to longest consecutive period of abstinence achieved. On this outcome, the effects of CM were pronounced in the middle/older and older age groups. In cocaine abusing outpatients who are not opioid dependent, the oldest adults improved the least with CM, likely because of a ceiling effect.4 In that population, the oldest cohort had the best outcomes with SC, and there was little room for further improvement. Compared to abusers receiving only psychosocial treatments, cocaine abusing methadone patients have more severe polydrug-dependence, and they submit more positive samples during treatment.c.f.,35,44 Hence, all age groups receiving SC in this study had ample room to improve with the addition of CM. The effect of CM was most pronounced in the age groups with the shortest durations of abstinence during standard methadone treatment. Although all age groups submitted relatively low proportions of cocaine negative samples during treatment, the age by treatment interaction effect was not significant for this variable.

Neither age nor its interaction with treatment condition were associated with cocaine abstinence 3 months after study treatments ended. Some variables were related to post-treatment abstinence, including study, methadone dose, initial cocaine toxicology result, and randomization to CM. The Petry et al.39 study recruited patients with severe cocaine dependence, and patients in that study had the lowest probability of a negative sample at follow-up. Higher methadone doses are provided to patients with greater opioid dependence, and therefore, it is not surprising that higher methadone doses are associated with poorer drug use outcomes. Study intake toxicology results reflect severity of cocaine problems and were a strong predictor of longer term outcomes in this and other studies.26,45,46 Also consistent with existing literature,e.g.,47 prior receipt of CM was related to better post-treatment outcomes, with a 55% increased probability of submitting a cocaine negative sample at follow-up. Age did not impact this relationship.

In sum, this study found that cocaine abusing methadone patients 40 years and older evidenced a greater response to CM treatment than their younger counterparts in terms of longest duration of cocaine abstinence achieved, but age and its interaction with treatment condition had no effect on other outcomes during or after treatment. Proportions of negative samples may be a less sensitive outcome than durations of continuous abstinence in CM trials because CM interventions are designed to reinforce long durations of abstinence. Age by treatment condition effects may have emerged only on the most sensitive index.

The results of this study should be interpreted within the context of some limitations. First, these patients were drawn from a single methadone clinic in the Northeast, and these data may not generalize to stimulant-abusing methadone patients in other areas of the country. The average age in the oldest group was 49 years old, and few individuals were over 60. The narrow range of ages in this sample may have masked differences that may be present in samples with greater age variability, and results may not generalize to older subgroups. Evaluation of treatment outcomes among cocaine abusing methadone patients with greater representation of patients over 60 years is needed.

Strengths of this study include the use of a large sample. Primary outcomes were available on 100% of patients, and a high rate of follow-up was achieved. Objective measures of cocaine use were used, as well as random assignment to treatment conditions. Patients received different CM interventions across the studies included in these analyses, and the use of multiple CM protocols supports generalization of the effects. Although CM was effective overall, CM appeared most beneficial to relatively older patients who responded least well to usual care procedures. As the American population continues to age and substance abusers are living longer, further examination of treatment modalities, such as CM, that may improve outcomes of older substance abusers is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research and preparation of this report was provided by National Institutes of Health grants P30-DA023918, T35AG026757, R01-DA13444, R01-DA016855, R01-DA14618, R01-DA022739, R01-DA021567, R01-DA018883, R01-DA027615, R01-DA024667, R01-MH60417-Suppl, P50-DA09241, P60-AA03510, and General Clinical Research Center Grant M01-RR06192 (Dr. Petry).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Gfroerer J, Penne M, Pemberton M, Folsom R. Substance abuse treatment need among older adults in 2020: The impact of the aging baby-boom cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han B, Gfroerer JC, Colliver JD, Penne MA. Substance use disorder among older adults in the United States in 2020. Addiction. 2009;104:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2008 National Household survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD: National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information (NCADI); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss LW, Petry NM. Interaction effects of age and contingency management treatments in cocaine-dependent outpatients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;19:173–181. doi: 10.1037/a0023031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemke S, Moos RH. Prognosis of older patients in mixed-age alcoholism treatment programs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22:33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemke S, Moos RH. Treatment and outcomes of older patients with alcohol use disorders in community residential programs. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:219–226. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satre DD, Mertens JR, Areán PA, Weisner C. Five-year alcohol and drug treatment outcomes of older adults versus middle-aged and younger adults in a managed care program. Addiction. 2004;99:1286–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkisian CA, Liu H, Gutierrez PR, Seeley DG, Cummings SR, Mangione CM. Modifiable risk factors predict functional decline among older women: a prospectively validated clinical prediction tool. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Am Geriatr. 2000;48:170–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warner EA, Greene GS, Buchsbaum MS, Cooper DS, Robinson BE. Diabetic ketoacidosis associated with cocaine use. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1799–1802. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frishman WH, Del Vecchio A, Sanal S, Ismail A. Cardiovascular manifestations of substance abuse part 1: cocaine. Heart Disease. 2003a;5:187–201. doi: 10.1097/01.hdx.0000074519.43281.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frishman WH, Del Vecchio A, Sanal S, Ismail A. Cardiovascular manifestations of substance abuse: part 2: alcohol, amphetamines, heroin, cannabis, and caffeine. Heart Disease. 2003b;5:253–271. doi: 10.1097/01.hdx.0000080713.09303.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firoz S, Carlson G. Characteristics and treatment outcome of older methadone-maintenance patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:539–541. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.5.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lofwall MR, Brooner RK, Bigelow GE, Kindbom K, Strain EC. Characteristics of older opioids maintenance patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen D, Smith ML, Reynolds CF. The prevalence of mental and physical health disorders among older methadone patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:488–497. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31816ff35a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satre DD, Mertens J, Arean PA, Weisner C. Contrasting outcomes of older versus middle-aged and younger adult chemical dependency patients in a managed care program. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:520–530. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colliver JD, Compton WM, Gfroerer JC, Condon T. Projecting drug use among aging baby boomers in 2020. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oslin DW, Slaymaker VJ, Blow FC, Owen PL, Colleran C. Treatment outcomes for alcohol dependence among middle-aged and older adults. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1431–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegal HA, Falck RS, Wang J, Carlson RG. Predictors of drug abuse treatment entry among crack-cocaine smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:159–166. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maglione M, Chao B, Anglin MD. Correlates of outpatient drug treatment drop-out among methamphetamine users. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:221–228. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKellar J, Kelly J, Harris A, Moos R. Pretreatment and during treatment risk factors for dropout among patients with substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2006;31:450–460. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neufeld K, King V, Peirce J, Kolodner K, Brooner R, Kidorf M. A comparison of 1-year substance abuse treatment outcomes in community syringe exchange participants versus other referrals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oslin DW, Pettinati H, Volpicelli JR. Alcoholism treatment adherence: older age predicts better adherence and drinking outcomes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:740–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saxon AJ, Wells EA, Fleming C, Jackson TR, Calsyn DA. Pre-treatment characteristics, program philosophy, and level of ancillary services as predictors of methadone maintenance treatment outcome. Addiction. 1996;91:1197–1209. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.918119711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance Abuse among Older Adults; Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 26. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance Abuse Relapse Prevention for Older Adults: A Group Treatment Approach. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preston LK, Silverman K, Higgins ST, et al. Cocaine use early in treatment predicts outcome in a behavioral treatment program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:691–696. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sofuoglu M, Gonzalez G, Poling J, Kosten TR. Prediction of treatment outcome by baseline urine cocaine results and self-reported cocaine use for cocaine and opioid dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:713–727. doi: 10.1081/ada-120026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williamson A, Darke S, Ross J, Teesson M. The effect of persistence of cocaine use on 12-month outcomes for the treatment of heroin dependence. Drug Alc Depend. 2006;81:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brody S, Slovis C, Wrenn K. Cocaine-related medical problems: consecutive series of 233 patients. Am J Med. 1990;88:325–331. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90484-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCord J, Jneid H, Hollander JE, et al. Management of cocaine associated chest pain and myocardial infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2008;117:1897–1907. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Treadwell SD, Robinson TG. Cocaine use and stroke. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:389–394. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.055970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A Meta-Analytic Review of Psychosocial Interventions for Substance Use Disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffith JD, Rowan-Szal GA, Roark RR, Simpson DD. Contingency management in outpatient methadone treatment: a meta-analysis. Drug Alc Depend. 2000;58:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierce JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Kellog S, Satterfield M, et al. Effects of lower-cost incentives on stimulant abstinence in methadone maintenance treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2006;63:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peirce JM, Petry NM, Roll JM, Kolodner K, Krasnansky J, Stabile PQ, et al. Correlates of stimulant treatment outcome across treatment modalities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:48–53. doi: 10.1080/00952990802455444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petry NM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Sierra S. Randomized trial of contingent prizes v vouchers in cocaine-using methadone patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:983–991. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petry NM, Martin B. Low-cost contingency management for treating cocaine and opioid-abusing methadone patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:398–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petry NM, Martin B, Simcic F. Prize reinforcement contingency management for cocaine dependence: Integration with group therapy in a methadone clinic. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:354–359. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola JS, Griffin JE. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lumley T, Diehr P, Emerson S, Chen L. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2002;23:151–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prigerson HG, Desai RA, Rosenheck RA. Older adult patients with both psychiatric and substance abuse disorders: Prevalence and health service use. Psychiat Quart. 2001;72:1–18. doi: 10.1023/a:1004821118214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petry NM, Peirce JM, Stitzer ML, et al. Effect of prize-based incentives on outcomes in stimulant abusers in outpatient psychosocial treatment programs. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2005b;62:1148–1156. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tzilos GK, Rhodes GL, Ledgerwood DM, Greenwald MK. Predicting cocaine group treatment outcome in cocaine-abusing methadone-maintained patients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;17:320–325. doi: 10.1037/a0016835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sullivan LE, Moore BA, O’Connor PG, et al. The association between cocaine use and treatment outcomes in patients receiving office-based buprenorphine/naloxone for the treatment of opioid dependence. Am J Addict. 2010;19:53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Higgins ST, Badger GJ, Budney AJ. Initial abstinence and success in achieving longer-term cocaine abstinence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8:377–386. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]