Abstract

Background

We assessed the feasibility and effectiveness of reduced-dose craniospinal (CS) radiotherapy (RT) followed by tandem high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (HDCT/autoSCT) in reducing late adverse effects without jeopardizing survival among children with high-risk medulloblastoma (MB).

Methods

From October 2005 through September 2010, twenty consecutive children aged >3 years with high-risk MB (presence of metastasis and/or postoperative residual tumor >1.5 cm2) were assigned to receive 2 cycles of pre-RT chemotherapy, CSRT (23.4 or 30.6 Gy) combined with local RT to the primary site (total 54.0 Gy), and 4 cycles of post-RT chemotherapy followed by tandem HDCT/autoSCT. Carboplatin-thiotepa-etoposide and cyclophosphamide-melphalan regimens were used for the first and second HDCT, respectively.

Results

Of 20 patients with high-risk MB, 17 had metastatic disease and 3 had a postoperative residual tumor >1.5 cm2 without metastasis. The tumor relapsed/progressed in 4 patients, and 2 patients died of toxicities during the second HDCT/autoSCT. Therefore, 14 patients remained event-free at a median follow-up of 46 months (range, 23−82) from diagnosis. The probability of 5-year event-free survival was 70.0% ± 10.3% for all patients and 70.6% ± 11.1% for patients with metastases. Late adverse effects evaluated at a median of 36 months (range, 12−68) after tandem HDCT/autoSCT were acceptable.

Conclusions

In children with high-risk MB, CSRT dose might be reduced when accompanied by tandem HDCT/autoSCT without jeopardizing survival. However, longer follow-up is needed to evaluate whether the benefits of reduced-dose CSRT outweigh the long-term risks of tandem HDCT/autoSCT.

Keywords: autologous stem cell transplantation, high-dose chemotherapy, late effect, medulloblastoma, radiotherapy

Medulloblastoma (MB) is the most common malignant brain tumor in children, accounting for 20% of childhood brain tumors.1 Traditionally, patients with MB are stratified into average- and high-risk groups, according to the clinical presentation, depending on the presence of metastasis (M1−M4) or postoperative residual tumor >1.5 cm2.2 The standard treatment of MB consists of surgery; radiotherapy (RT), including craniospinal RT (CSRT); and chemotherapy.3–7 The conventional doses of RT have been around 36 Gy to the craniospinal axis combined with a boost of 18−20 Gy to the posterior fossa, for a total dose of 54−56 Gy. Children who survive MB are at risk for various late adverse effects primarily attributable to RT, particularly CSRT.8–14 Of most concern among possible late adverse effects is the negative neurocognitive sequelae. In addition, the majority of survivors experience significant growth and endocrine dysfunction because of irradiation of the pituitary gland, hypothalamic regions, and whole spine.

For patients with average-risk MB (defined by postoperative residual tumor <1.5 cm2 and no metastasis), the introduction of effective chemotherapy has greatly improved survival and helped to reduce the necessary doses of CSRT.15,16 However, the prognosis for high-risk MB (defined by metastasis and/or postoperative residual tumor >1.5 cm2) is unsatisfactory, despite standard-dose CSRT; 5-year survival is <55%.5–7

A treatment strategy using high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (HDCT/autoSCT) has shown clinical benefit in children with high-risk or recurrent solid tumors.17,18 Clinical trials using HDCT/autoSCT in infants and young children with malignant brain tumors have shown that it is possible to avoid or defer RT until 3 years of age while improving or maintaining survival rates.19–21 HDCT/autoSCT has been also used to treat high-risk or recurrent MBs. Some investigators have applied this treatment modality in relapsed/progressed cases, and some reports exist that use this strategy as a first-line treatment for newly diagnosed MBs.22–25 Recently, several studies have suggested that further dose-escalation using tandem HDCT/autoSCT might further improve outcomes in the treatment of recurrent or high-risk brain tumors.26,27 Gajjar and colleagues have reported the results of a prospective study (St. Jude Medulloblastoma [SJMB] 96 study) using tandem HDCT/autoSCT in patients with high-risk MB. In their study, patients received 36.0–39.6 Gy of CSRT followed by 4 cycles of HDCT/autoSCT, and the 5-year event-free survival (EFS) rate was 70%.26 A previous report from our institution also suggested that tandem HDCT/autoSCT was feasible and might further improve outcomes in patients with recurrent or high-risk brain tumors.27 The EFS rates have been encouraging in these studies; however, late adverse effects from dose-intense chemotherapy might potentiate late adverse effects from conventional RT. In the present study, we prospectively evaluated the feasibility and effectiveness of reduced-dose CSRT followed by tandem HDCT/autoSCT in the treatment of children with high-risk MB. Our new treatment strategy aimed to maintain patient survival while reducing the risks of late adverse effects associated with CSRT.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Children aged >3 years at the time of their initial diagnosis and found to have high-risk MB (defined by the presence of metastasis or postoperative residual tumor >1.5 cm2) were enrolled in the study from October 2005 through September 2010. A pediatric neuropathologist confirmed all cases according to the World Health Organization criteria.1 Disease extent at diagnosis was assessed using brain and spinal MRI and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology. These analyses were performed within 3 weeks and, preferably, within 2 weeks after surgery. The Samsung Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study, and all parents and guardians gave their informed consent.

Induction Chemotherapy

Table 1 lists the induction chemotherapy regimens that were initiated within 4 weeks and, preferably, within 3 weeks after surgery. A total of 6 cycles of induction chemotherapy were administered prior to tandem HDCT/autoSCT. Two cycles of pre-RT and 4 cycles of post-RT chemotherapy were given. Post-RT chemotherapy was initiated within four weeks after completion of RT, and the doses were reduced by 25% of the calculated dose. A cisplatin-etoposide-cyclophosphamide-vincristine (CECV) regimen and a carboplatin-etoposide-ifosfamide-vincristine (CEIV) regimen were used in alternation. Each chemotherapy cycle was scheduled 28 days apart, but some delays were permitted to allow the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) and platelet count to recover to 1000 neutrophils/μL and 100 000 platelets/μL, respectively. Peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) were collected during the recovery phase of the first chemotherapy cycle.

Table 1.

Induction and high-dose chemotherapy regimens

| Regimen | Drug | Dose | Schedule |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induction regimens | |||

| CECV | Cisplatin | 90 mg/m2/day | Day 0 |

| Etoposide | 75 mg/m2/day | Days 0, 1, 2 | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1,500 mg/m2/day | Days 1, 2 | |

| Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2/day | Days 0, 7 | |

| CEIV | Carboplatin | 300 mg/m2/day | Days 0, 1 |

| Etoposide | 75 mg/m2/day | Days 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 | |

| Ifosfamide | 1,500 mg/m2/day | Days 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 | |

| Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2/day | Days 0, 7 | |

| HDCT regimens | |||

| CTE | Carboplatin | 500 mg/m2/day | Days −8, −7, −6 |

| Thiotepa | 300 mg/m2/day | Days −5, −4, −3 | |

| Etoposide | 250 mg/m2/day | Days −5, −4, −3 | |

| CM | Cyclophosphamide | 1,500 mg/m2/day | Days −8, −7, −6, −5 |

| Melphalan | 60 mg/m2/day | Days −4, −3, −2 | |

Radiotherapy

During the early study period (patients who received a diagnosis from October 2005 through December 2007), the RT consisted of 23.4 Gy of CSRT, 30.6 Gy of local RT to the primary site, and 21.6 Gy of boost RT to the gross seeding nodule (if present). RT was given at 1.8 Gy/day and 5 days/week. For local RT to the primary site, the radiation target volume was not the entire posterior fossa but rather the surgical defect with 1–2-cm margins. This local RT to the primary site was performed by 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy. During the early study period, tumor relapse or progression occurred at the spinal cord in 3 of 9 patients with metastasis (M+), including 1 patient with large-cell/anaplastic MB. Therefore, in the late study period (patients who received a diagnosis after January 2008), we changed the RT regimen to 30.6 Gy of CSRT, 23.4 Gy of local RT to the primary site, and 14.4 Gy of boost RT to the gross seeding nodule (if present) in patients with leptomeningeal seeding who were aged >6 years at diagnosis or patients with large-cell/anaplastic MB.

Tandem HDCT/autoSCT

The regimens for the first and second HDCT/autoSCT were carboplatin-thiotepa-etoposide (CTE) and cyclophosphamide-melphalan (CM), respectively (Table 1). We allowed an approximately 12-week interval without treatment between the first and second HDCT/autoSCT. Roughly half of the PBSCs collected during a single round of leukapheresis were infused for marrow rescue during each HDCT/autoSCT session.

Response and Toxicity Criteria

Disease response was evaluated by brain and spinal MRI and CSF cytology after the second, fourth, and sixth chemotherapy cycles preceding HDCT/autoSCT, between the first and second HDCT/autoSCT, every 3 months for the first year after completion of HDCT/autoSCT, every 4 months for the second year after completion of HDCT/autoSCT, and every 6 months thereafter. Tumor size was estimated by MRI as the product of the greatest diameter and the longest perpendicular diameter. Disease responses were categorized as follows: progressive disease (>25% increase in tumor size or the appearance of a new area of tumor), stable disease (<25% change in tumor size), minor response (25%–50% decrease in tumor size), partial response (>50% decrease in tumor size), or complete response (complete disappearance of all previously measurable tumor). Toxicities were graded using the National Cancer Institute's Common Terminology Criteria (version 4.0).

Evaluation of Late Adverse Effects

Late adverse effects were evaluated at least annually after completion of HDCT/autoSCT. The diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency was based on a declining growth rate, and it was confirmed by biochemical testing. Hypothyroidism was diagnosed by elevation of thyrotropin. Adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed on the basis of the failure to increase cortisol levels after corticotropin releasing hormone administration. Cognitive function was evaluated using the Korean-Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence and Korean version of Wechsler Intelligence Scales of Children. Cardiac, renal, hepatic, auditory, ophthalmologic, and immune functions were also evaluated.

Statistics

EFS was calculated from the date of diagnosis until the date of relapse, progression, or death (whichever occurred first). Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis until death from any cause. Survival rates and standard errors were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

Patient Characteristics

During the study period, 20 consecutive patients (14 boys and 6 girls) with high-risk MB were enrolled in the study. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 2. The median age at diagnosis was 108 months (range, 46−290 months), and 16 patients were <12 years of age at diagnosis. Seventeen patients had metastatic disease (M2 in 4, M3 in 12, and M4 in 1), and the remaining 3 patients had a significant postoperative residual tumor (>1.5 cm2) without metastasis. Four patients had large-cell/anaplastic MB.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| No. | Sex/Age (m) | Pathology | Residual tumor >1.5 cm2 | M stage | CSRT (Gy) | Local RT to PF (Gy) | Boost to metastatic nodule (Gy) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M/104 | desmoplastic | No | 2 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 0 | 82 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 2 | M/139 | classic | Yes | 2 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 0 | 81 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 3 | F/208 | anaplastic | Yes | 3 | 23.4 (+21.6)a | 30.6 | 0 | 69 m, dead, Rel (S) at 10 m |

| 4 | M/58 | classic | No | 2 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 0 | 78 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 5 | M/91 | desmoplastic | No | 3 | 23.4 (+18.0)a | 30.6 | 0 | 16 m, dead, PRG (S) at 6 m |

| 6 | M/84 | anaplastic | No | 3 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 0 | 73 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 7 | F/290 | classic | No | 3 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 0 | 72 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 8 | M/46 | classic | No | 3 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 21.6 | 33 m, dead, Rel (S) at 21 m |

| 9 | F/167 | classic | No | 3 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 0 | 55 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 10 | M/86 | classic | Yes | 3 | 30.6 | 23.4 | 0 | 13 m, dead, VOD at 13 m |

| 11 | F/110 | anaplastic | Yes | 0 | 30.6 | 23.4 | 0 | 15 m, dead, Rel (P) at 11 m |

| 12 | M/132 | classic | Yes | 0 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 0 | 48 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 13 | M/116 | classic | Yes | 3 | 30.6 | 23.4 | 14.4 | 45 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 14 | M/113 | classic | No | 3 | 30.6 | 23.4 | 14.4 | 44 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 15 | M/121 | anaplastic | Yes | 3 | 30.6 | 23.4 | 14.4 | 40 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 16 | M/49 | classic | No | 3 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 0 | 35 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 17b | F/108 | classic | Yes | 4 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 21.6 | 26 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 18 | M/96 | classic | No | 3 | 30.6 | 23.4 | 0 | 15 m, dead, VOD at 15 m |

| 19 | M/148 | classic | No | 2 | 30.6 | 23.4 | 0 | 26 m+, alive, Ds free |

| 20 | F/80 | classic | Yes | 0 | 23.4 | 30.6 | 0 | 23 m+, alive, Ds free |

Abbreviations: CSRT, craniospinal radiotherapy; Ds, disease; m, month(s); P, primary site; PF, posterior fossa; PRG, progression; Rel, relapse; S, spinal cord; VOD, hepatic veno-occlusive disease.

aAdditional CSRT was given after relapse/progression.

bThis patient had a metastasis on the pelvic bone without leptomeningeal seeding and received 23.4 Gy of CSRT and 21.6 Gy of boost RT to the metastatic nodule.

Induction Chemotherapy

With the exception of neutropenic fever, which was experienced by all patients, induction chemotherapy was successfully administered without significant toxicity. During the 3 leukapheresis procedures per patient, the median number of CD34+ cells collected was 117.1 × 106/kg (range, 33.9−363.6). The tumor relapsed or progressed during post-RT chemotherapy in 2 patients with prior leptomeningeal seeding. The remaining 18 patients proceeded to the first HDCT/autoSCT without relapse or progression of disease, and their tumor statuses were CR in 13 patients and PR in 5 patients. The 2 patients who experienced relapse/progression during post-RT chemotherapy also proceeded to tandem HDCT/autoSCT after 2 cycles of salvage chemotherapy (topotecan + cyclophosphamide) and additional CSRT.

RT

Two of 3 M0 patients and 11 of 17 M+ patients received 23.4 Gy of CSRT. The remaining 7 patients (6 M+ patients and 1 M0 patient with large-cell/anaplastic MB) received 30.6 Gy of CSRT. One patient (patient 17 in Table 2) with a metastasis on the pelvic bone without leptomeningeal seeding also received 23.4 Gy of CSRT. In 5 patients, boost RT to a gross metastatic nodule was given.

Tandem HDCT/autoSCT

The median interval from day 0 of the first HDCT/autoSCT to the initiation of the second HDCT/autoSCT was 83 days (range, 75−90 days). One patient who had a large-cell/anaplastic tumor and had a significant postoperative residual tumor without metastasis experienced relapse after the first HDCT/autoSCT at the primary site within the local RT field but proceeded to the second HDCT/autoSCT as salvage treatment. Therefore, all 20 patients, including the 2 patients who experienced relapse/progression during post-RT chemotherapy, completed tandem HDCT/autoSCT. Table 3 shows the toxicity profile of patients receiving tandem HDCT/autoSCT. Both the neutrophil and the platelet counts recovered rapidly during the first and second HDCT/autoSCT. During the first HDCT/autoSCT, frequent grade 3/4 toxicities included fever, stomatitis, diarrhea, elevation of liver enzymes, and hypokalemia. No treatment-related mortality (TRM) occurred during the first HDCT/autoSCT. During the second HDCT/autoSCT, frequent grade 3/4 toxicities included fever, hypokalemia, and hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD). TRM from hepatic VOD occurred in 2 patients during the second HDCT/autoSCT.

Table 3.

Toxicity profile of tandem HDCT/autoSCT

| Parameters | First HDCT/autoSCT (n = 20) | Second HDCT/autoSCT (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Hematologic toxicity | ||

| CD34+ cells (×106/kg) | 43.9 (11.1−98.0)a | 41.2 (10.3−157.0) |

| Days to reach an ANC 500/μLb | 8 (8−10) | 9 (8−12) |

| Days to reach a PLT count 20 000/μLc | 17 (13−30) | 20.5 (13−119) |

| Days of BT ≥38.0oC | 5.5 (0−8) | 2 (0−7) |

| Positive blood culture (No. of patients) | 2 | 5 |

| Non-hematologic toxicity (No. of patients) | ||

| Stomatitis | 19 | 2 |

| Vomiting | 3 | 2 |

| Diarrhea | 8 | 4 |

| Elevation of liver enzyme | 12 | 2 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 0 | 1 |

| Renal insufficiency | 0 | 2 |

| Hypokalemia | 10 | 7 |

| Heperkalemia | 1 | 1 |

| Hyponatremia | 0 | 1 |

| Hypernatremia | 1 | 0 |

| Hepatic VOD | 1 | 6 |

| Myocarditis | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-related mortality | 0 | 2 |

Abbreviations: ANC, absolute neutrophil count; BT, body temperature; HDCT/autoSCT, high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation; PLT, platelet; VOD, veno-occlusive disease.

aMedian (range).

bThe first day ANC exceeded 500 neutrophils/μL for 3 consecutive days.

cThe first day PLT count exceeded 20 000 platelets/μL without transfusion for 7 days.

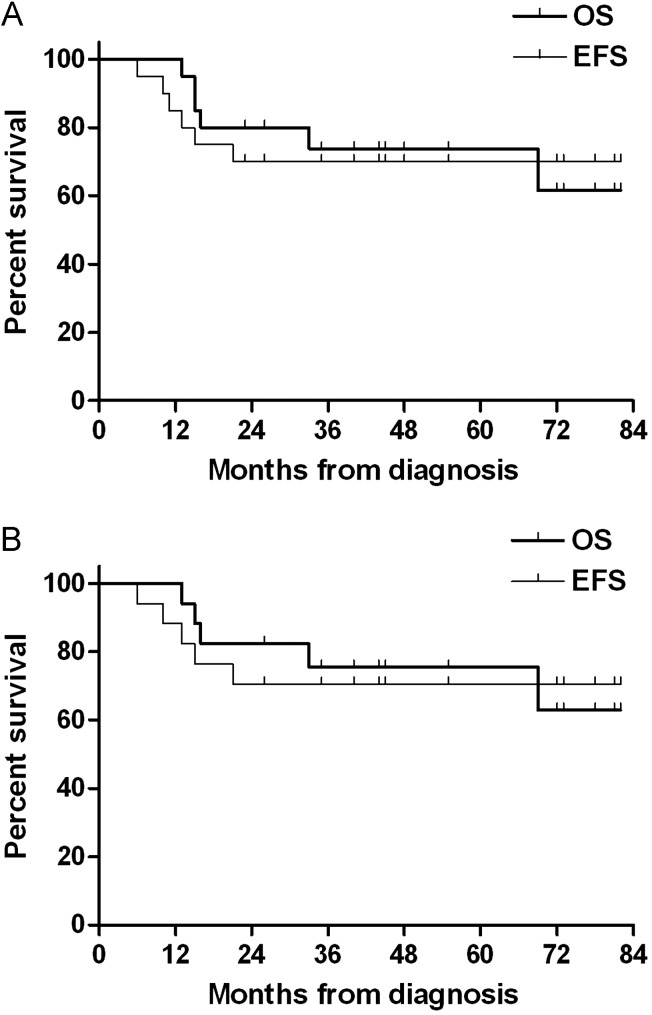

Survival

Tumor relapse or progression occurred in 4 patients (3 at the spinal cord and 1 at the primary site). All 3 relapse/progressions at the spinal cord occurred in M+ patients who received 23.4 Gy of CSRT. However, there were no relapses among the 6 M+ patients who received 30.6 Gy of CSRT. Unfortunately, 2 of the 6 M+ patients who received 30.6 Gy of CSRT experienced TRM during the second HDCT/autoSCT. All 3 patients who completed tandem HDCT/autoSCT after relapse/progression, including the 2 patients who experienced relapse/progression during post-RT chemotherapy, died of tumor progression. Overall, a total of 14 patients remained event-free at a median follow-up time of 46 months (range, 23–82 months) from diagnosis. For all patients, the probabilities of 5-year EFS and OS were 70.0% ± 10.3% and 73.9% ± 10.2%, respectively (Fig. 1A). Among the 17 patients with metastases, the probabilities of 5-year EFS and OS were 70.6% ± 11.1% and 75.5% ± 10.7%, respectively (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) rates. (A) The probabilities of 5-year EFS and OS for all patients were 70.0% ± 10.3% and 73.9% ± 10.2%, respectively. (B) The probabilities of 5-year EFS and OS for the 17 patients with metastasis were 70.6% ± 11.1% and 75.5% ± 10.7%, respectively.

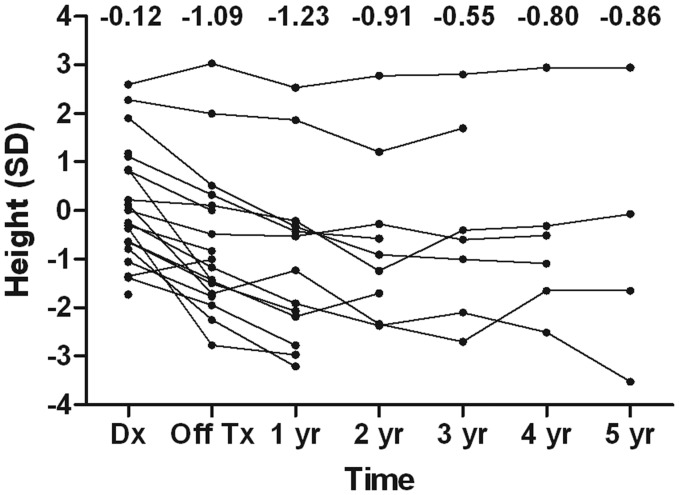

Late Adverse Effects

Thirteen patients who remained event-free for >1 year after the second HDCT/autoSCT were evaluated for the presence of various late adverse effects. Table 4 shows the late adverse effects that were observed in these patients at a median of 36 months (range, 12–68 months) after the second HDCT/autoSCT. Frequent late adverse effects included hypothyroidism, growth hormone deficiency, sex hormone deficiency, hearing loss, and renal tubulopathy. Until 1 year after tandem HDCT/autoSCT, a deceleration in vertical growth was prominent. However, this deceleration was mitigated with growth hormone replacement (Fig. 2). The median height 3 years after the second HDCT/autoSCT was -0.55 standard deviations from the mean (range, −2.7 to 2.8) for patient age. The median values for full-scale, verbal, and performance intelligence quotient (IQ) evaluated after initial surgery were 85 (range, 67–117), 94 (range, 68–120), and 82 (range, 61–109). The median IQs at a median of 34 months (range, 21–70) after RT were found to be 81 (range, 65–108), 89 (range, 67–117), and 82 (range, 67–95).

Table 4.

Late adverse effects three years after tandem HDCT/autoSCT

| Grade 1−2 | Grade 3−4 | Total No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine (n = 13) | |||

| Hypothyroidism | 7 | 0 | 7 (53.8%) |

| Growth hormone deficiency | 8 | 0 | 8 (61.5%) |

| Glucocorticoid deficiency | 2 | 0 | 2 (15.4%) |

| Sex hormone deficiency (n = 8)a | 4 | 0 | 4 (50.0%) |

| Hearing loss (n = 13) | 7 | 2 | 9 (69.2%) |

| Cataract (n = 13) | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Chronic lung disease (n = 13) | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Renal (n = 13) | |||

| Glomerulopathy | 1 | 0 | 1 (7.7%) |

| Tubulopathy | 4 | 0 | 4 (30.8%) |

| Second malignancy (n = 13) | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Cardiac (n = 13) | 0 | 0 | 0 (0%) |

aEight patients had reached pubertal age at the time of evaluation.

Fig. 2.

Individual patient height curves. Deceleration of vertical growth was prominent until 1 year after completion of HDCT/autoSCT. However, it was mitigated after 1 year of follow-up because of the initiation of growth hormone replacement. The median height 3 years after completion of HDCT/autoSCT was −0.55 standard deviations (SDs) from the mean (range, −2.7 to 2.8 SDs) for the patient's age.

Discussion

Late adverse effects of RT, particularly CSRT, have been one of the most significant problems in the treatment of MB.8–16 In young children with malignant brain tumors, these unacceptable late adverse effects have led a number of institutions and national groups to attempt to delay or avoid RT by using HDCT/autoSCT. These groups have reported that, in young children with malignant brain tumors, the use of HDCT/autoSCT can delay or eliminate the need for RT with maintenance of patient survival.19–21,27 For older children with average-risk MB, reports have shown that survival is maintained when the dose of CSRT is reduced to 23.4 Gy and CSRT is followed by effective adjuvant chemotherapy.15,16 These findings suggest that the dose of CSRT can be reduced when coupled with intensification of chemotherapy. In the present study in children with high-risk MB, we used tandem HDCT/autoSCT to reduce the dose of CSRT, with the goals of maintaining survival and reducing late adverse effects associated with CSRT. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has attempted to reduce the dose of CSRT in children with high-risk MB with use of tandem HDCT/autoSCT. Our results suggest that children with high-risk MB can be treated with dose-intense chemotherapy and a decreased dose of CSRT, with maintenance or slight improvement in survival.

When analyzing specific subgroups, the EFS for M+ patients in our study is generally encouraging. Tumor relapse or progression occurred in only 3 of 17 M+ patients. However, these 3 relapse/progressions occurred at the spinal cord in patients who received 23.4 Gy of CSRT during the early study period. Thereafter, we increased the dose of CSRT to 30.6 Gy in patients >6 years of age with leptomeningeal seeding. As a result, none of the 6 patients with metastasis who received 30.6 Gy of CSRT experienced relapse/progression. However, 2 of them died of treatment-related toxicity, although it is not clear whether increased CSRT dose was related to treatment-related toxicity. Taken together, the relapse/progression events and toxicity-related deaths make it difficult to decide which CSRT dose (23.4 Gy or 30.6 Gy) produces a better outcome.

In the SJMB-96 study, patients with high-risk MB received 36.0−39.6 Gy of CSRT followed by 4 cycles of HDCT/autoSCT with cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and vincristine. Each HDCT/autoSCT cycle was separated by a 4-week treatment-free interval.26 The study reported a 5-year EFS of 70% for all patients, and there was no TRM. In the present study, patients with high-risk MB received lower doses of CSRT (23.4 or 30.6 Gy) than in the SJMB-96 study. Conversely, the intensity of pre-RT chemotherapy, post-RT chemotherapy, and HDCT was generally higher in our study than in the SJMB 96 study. When comparing results, the EFS was similar between the 2 studies. These findings suggest that, in patients with high-risk MB, dose-intense chemotherapy may decrease the necessary dose of CSRT without jeopardizing survival.

With the exception of neutropenic fever in all patients, there were no notable toxicities during induction chemotherapy or RT. Toxicities during the first HDCT/autoSCT were manageable, although severe mucositis-related toxicities were difficult on patients. The frequency and severity of mucositis-related toxicity was much lower during the second HDCT/autoSCT. However, hepatic VOD developed in 6 patients during the second HDCT/autoSCT, and 2 patients died of hepatic VOD. Recently, Rosenfeld et al. reported their experience with tandem HDCT/autoSCT in children with brain tumors.28 They used almost the same tandem HDCT regimen as ours. Two (10.5%) of 19 patients in the first HDCT/autoSCT and 4 (36.4%) of 11 patients in the second HDCT/autoSCT died of transplant-related toxicities. The authors concluded that the CTE/CM regimen was not feasible because of these toxicities. Compared with the Rosenfeld study, the TRM rate in our study was relatively low, but several important differences between the studies must be noted. First, the interval between the first and second HDCT/autoSCT was longer in our study than in Rosenfeld's. Although in the Rosenfeld study, the second HDCT/autoSCT was set to begin by day 50, presuming that the ANC was >1000 neutrophils/μL and all significant toxicities had resolved, we allowed an approximately 12-week interval between the first and second cycle of HDCT/autoSCT as a precautionary measure. We previously reported that a shorter interval between the first and second HDCT/autoSCT in patients with high-risk neuroblastoma may be associated with higher TRM during the second HDCT/autoSCT.29 A second difference between our study and Rosenfeld's was that, although 75% of their patients entered the study with tumor relapse, all patients in our study began with newly diagnosed MB. In heavily pretreated patients, TRM from HDCT/autoSCT may be higher than in patients with newly diagnosed disease. A final difference between our study and Rosenfeld's was the period in which they were performed. Many patients in the study by Rosenfeld et al. received tandem HDCT/autoSCT during the late 1990's and early 2000's, and the patients in our study received tandem HDCT/autoSCT during the late 2000's. Advances in supportive care may have influenced TRM in our study. Taken together, the EFS, OS, and TRM rates in the present study suggest that, in children with high-risk MB, HDCT/autoSCT is an acceptable treatment modality if the interval between the first and second cycles of HDCT/autoSCT is as long as the one that we used.

Neuroendocrine dysfunction developed in more than half of the patients evaluated in the present study. Short stature was also common, but it was less prominent after the initiation of growth hormone replacement >1 year after completion of HDCT. Sensory neural hearing loss and nephropathy were also frequent late adverse effects, although all nephropathies were grade 1 abnormalities that did not require medication. Most patients demonstrated acceptable levels of cognitive function comparable to patients who received 23.4–25.0 Gy of CSRT in previous studies.13,14 The verbal IQ of our patients was encouraging because this will play a key role in their adjustment to daily life. Despite the limited follow-up duration, our findings suggest that, in patients with high-risk MB, the current treatment strategy may decrease late adverse effects associated with RT, particularly CSRT. However, dose-intense chemotherapy can also result in significant late adverse effects. In addition, the follow-up duration in the present study is too short to estimate the actual risk of a second neoplasm, which remains a matter of some concern. Therefore, there is a need for longer follow-up because it is difficult to assess whether our strategy will ultimately reduce overall late adverse effects that are a result of not only RT but also dose-intense chemotherapy.

Risk stratification in the present study is based on clinical parameters (age, the presence of metastasis, or significant postoperative residual tumor). Recent efforts at stratifying MB on the basis of their molecular features have subdivided MB into 4 distinct molecular subgroups characterized by disparate transcriptional signatures, mutational spectra, copy number profiles, and clinical features.30 Molecular stratification of MB with use of a gene expression–based approach will improve current risk stratification. In the next phase of clinical trial development, the selection of patients to innovative approach will be based also on these data, thus potentially avoiding intensive treatment regimen to some of those patients presently considered as high-risk.

In summary, the present study suggests that, in children with high-risk MB, the dose of CSRT might be reduced without jeopardizing survival by using tandem HDCT/autoSCT. However, longer follow-up is needed to evaluate whether the benefits from CSRT dose reduction outweigh the long-term risks of tandem HDCT/autoSCT. In addition, a prospective study with a larger cohort of patients is needed to confirm the results of the present study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant 0520300).

Conflict of interest statement. No conflicts of interest were declared.

References

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packer RJ, Rood BR, MacDonald TJ. Medulloblastoma: present concepts of stratification into risk groups. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2003;39:60–67. doi: 10.1159/000071316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massimino M, Giangaspero F, Garrè ML, et al. Childhood medulloblastoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;79:65–83. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varan A. Risk-adapted chemotherapy in childhood medulloblastoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011;11:771–780. doi: 10.1586/era.10.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeltzer PM, Boyett JM, Finlay JL, et al. Metastasis stage, adjuvant treatment, and residual tumor are prognostic factors for medulloblastoma in children: conclusions from the Children's Cancer Group 921 randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:832–845. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor RE, Bailey CC, Robinson KJ, et al. Outcome for patients with metastatic (M2–3) medulloblastoma treated with SIOP/UKCCSG PNET-3 chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:727–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kortmann RD, Kühl J, Timmermann B, et al. Postoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy before radiotherapy as compared to immediate radiotherapy followed by maintenance chemotherapy in the treatment of medulloblastoma in childhood: results of the German prospective randomized trial HIT ‘91. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:269–279. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diller L, Chow EJ, Gurney JG, et al. Chronic disease in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort: a review of published findings. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2339–2355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurney JG, Ness KK, Stovall M, et al. Final height and body mass index among adult survivors of childhood brain cancer: childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4731–4739. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Packer RJ, Gurney JG, Punyko JA, et al. Long-term neurologic and neurosensory sequelae in adult survivors of a childhood brain tumor: childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3255–3261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurney JG, Kadan-Lottick NS, Packer RJ, et al. Endocrine and cardiovascular late effects among adult survivors of childhood brain tumors: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2003;97:663–673. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulhern RK, Merchant TE, Gajjar A, et al. Late neurocognitive sequelae in survivors of brain tumours in childhood. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:399–408. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulhern RK, Kepner JL, Thomas PR, et al. Neuropsychologic functioning of survivors of childhood medulloblastoma randomized to receive conventional or reduced-dose craniospinal irradiation: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1723–1728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grill J, Renaux VK, Bulteau C, et al. Long-term intellectual outcome in children with posterior fossa tumors according to radiation doses and volumes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Packer RJ, Goldwein J, Nicholson HS, et al. Treatment of children with medulloblastomas with reduced-dose craniospinal radiation therapy and adjuvant chemotherapy: A Children's Cancer Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2127–2136. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Packer RJ, Gajjar A, Vezina G, et al. Phase III study of craniospinal radiation therapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed average-risk medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4202–4208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthay KK, Reynolds CP, Seeger RC, et al. Long-term results for children with high-risk neuroblastoma treated on a randomized trial of myeloablative therapy followed by 13-cis-retinoic acid: a children's oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1007–1013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marachelian A, Butturini A, Finlay J. Myeloablative chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell rescue for childhood central nervous system tumors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:167–172. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason WP, Grovas A, Halpern S, et al. Intensive chemotherapy and bone marrow rescue for young children with newly diagnosed malignant brain tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:210–221. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chi SN, Gardner SL, Levy AS, et al. Feasibility and response to induction chemotherapy intensified with high-dose methotrexate for young children with newly diagnosed high-risk disseminated medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4881–4887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fangusaro J, Finlay J, Sposto R, et al. Intensive chemotherapy followed by consolidative myeloablative chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic cell rescue (AuHCR) in young children with newly diagnosed supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumors (sPNETs): report of the Head Start I and II experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:312–318. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridola V, Grill J, Doz F, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue followed by posterior fossa irradiation for local medulloblastoma recurrence or progression after conventional chemotherapy. Cancer. 2007;110:156–163. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valteau-Couanet D, Fillipini B, Benhamou E, et al. High-dose busulfan and thiotepa followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in previously irradiated medulloblastoma patients: high toxicity and lack of efficacy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:939–945. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pérez-Martínez A, Lassaletta A, González-Vicent M, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue for children with high risk and recurrent medulloblastoma and supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumors. J Neurooncol. 2005;71:33–38. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-4527-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aihara Y, Tsuruta T, Kawamata T, et al. Double high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for primary disseminated medulloblastoma: a report of 3 cases. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:e70–74. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181c46b92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gajjar A, Chintagumpala M, Ashley D, et al. Risk-adapted craniospinal radiotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell rescue in children with newly diagnosed medulloblastoma (St Jude Medulloblastoma-96): long-term results from a prospective, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:813–820. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70867-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sung KW, Yoo KH, Cho EJ, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell rescue in children with newly diagnosed high-risk or relapsed medulloblastoma or supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:408–415. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenfeld A, Kletzel M, Duerst R, et al. A phase II prospective study of sequential myeloablative chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell rescue for the treatment of selected high risk and recurrent central nervous system tumors. J Neurooncol. 2010;97:247–255. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sung KW, Lee SH, Yoo KH, et al. Tandem high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell rescue in patients over 1 year of age with stage 4 neuroblastoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:37–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Pfister SM, et al. The clinical implications of medulloblastoma subgroups. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:340–351. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]