Abstract

Study Objectives:

Identify polysomnographic and demographic factors associated with elevation of nocturnal end-tidal CO2 in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Methods:

Forty-four adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea were selected such that the maximal nocturnal end-tidal CO2 was below 45 mm Hg in 15 studies, between 45 and 50 mm Hg in 14, and above 50 mm Hg in 15. Measurements included mean event (i.e., apneas or hypopneas) and mean inter-event duration, ratio of mean post- to mean pre-event amplitude, and percentage of total sleep time spent at an end-tidal CO2 < 45, 45-50, and > 50 mm Hg. An integrated nocturnal CO2 was calculated as the sum of the products of average end-tidal CO2 at each time interval by percent of total sleep time spent at the corresponding time interval.

Results:

The integrated nocturnal CO2 was inversely correlated with mean post-apnea duration, with lesser contributions from mean apnea duration and age (R2 = 0.56), but did not correlate with the apnea-hypopnea index, or the body mass index. Mean post-event to mean pre-event amplitude correlated with mean post-apnea duration (r = 0.88, p < 0.001). Mean apnea duration did not correlate with mean post-apnea duration.

Conclusions:

Nocturnal capnometry reflects pathophysiologic features of sleep apnea, such as the balance of apnea and post-apnea duration, which are not captured by the apnea-hypopnea index. This study expands the indications of capnometry beyond apnea detection and quantification of hypoventilation syndromes.

Citation:

Jaimchariyatam N; Dweik RA; Kaw R; Aboussouan LS. Polysomnographic determinants of nocturnal hypercapnia in patients with sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2013;9(3):209-215.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea, hypercapnia, capnography, body mass index, obesity hypoventilation syndrome

Transcutaneous or end-tidal capnometry is commonly used in the polysomnographic evaluation of children in whom sleep disordered breathing manifests predominantly as obstructive hypoventilation.1 Alternatively, the role of capnometry in adult polysomnography has been more limited, usually for the quantitative assessment of sleep hypoventilation syndromes,2 or even less commonly, for the measurement of end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) as an adjunct signal for the detection of airflow obstruction in sleep apnea.3,4 Few studies are available to assess the use or accuracy of capnometry for those purposes,5 and it therefore has not been routinely used in adult sleep laboratories.

However, current ETCO2 sampling devices are reliable and only slightly underestimate the arterial CO2, with a gradient of 5 mm Hg in patients with minimal ventilation-perfusion mismatch.6 In obese postoperative patients with obstructive sleep apnea, the mean arterial to ETCO2 gradient was 8.3 mm Hg.7 Even in patients with diverse neuromuscular and pulmonary disorders, the ETCO2 during sleep was found to underestimate a simultaneous arterial CO2 by ≥ 10 mm Hg in only 21% of the readings.8

In that context, in patients with sleep apnea but without suspected sleep-hypoventilation syndromes, we noted elevation of nocturnal ETCO2 that were unexpected in relation to the body mass index or the apnea-hypopnea index, indices usually associated with daytime hypercapnia in the obesity hypoventilation syndrome.9 We therefore sought to determine whether the nocturnal ETCO2 could reflect physiologic characteristics of obstructive sleep apnea not addressed by the apnea-hypopnea index or body mass index, and therefore expand its indication beyond the hypoventilation syndromes. For instance, contributors to the development of an elevated daytime arterial CO2 linked to obstructive respiratory events during sleep include post-event (subsuming apneas and hypopneas) ventilation as a function of CO2 load10,11 and apnea duration in relation to post-apnea duration.12

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Although end-tidal CO2 determination is reliable and accurate, its current application in polysomnography has been limited to the evaluation of sleep disordered breathing in children, the quantitative assessment of sleep hypoventilation syndromes, or as an adjunct signal for detection of sleep apnea. The aim of our study was to investigate whether end-tidal CO2 is associated with polysomno-graphic or demographic characteristics in patients with sleep apnea.

Study Impact: Daytime and nocturnal end-tidal CO2 are significantly related to post apnea duration, and to a lesser extent to apnea duration and age, but not to the apnea-hypopnea index or the body mass index. End-tidal CO2 monitoring can therefore be expanded beyond its current applications in apnea detection and hypoventilation syndromes, to its use as a marker of the pathophysiology, severity, and ventilatory burden of sleep apnea, all features that may be inadequately captured by the apnea-hypopnea index.

We therefore selected groups of obstructive sleep apnea patients with different severity of nocturnal CO2 elevation and assessed the relative contributions of demographic factors, sleep apnea severity, respiratory event and respiratory inter-event duration, as well as post-event amplitude relative to pre-event amplitude, to an overall measure of nocturnal ETCO2.

METHODS

We reviewed polysomnograms and clinical charts of patients diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea at our center from 2008 to 2009. Inclusion criteria were age > 18 years, total sleep time ≥ 6 h with a sleep efficiency ≥ 65%,13 and an apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 5. We excluded studies where central apneas represented > 50% of the apnea-hypopnea index, studies requiring oxygen administration, titration studies, and other conditions that could confound the nocturnal CO2 or impair the accuracy of the ETCO2 as a measure of arterial CO2 (i.e., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, neuromuscular diseases, use of diuretics, alcohol or narcotics, or > 20 pack-year smoking history). To ensure an adequate representation of various ranges of CO2 values, we aimed for an equal number of patients in each of the following groups: maximal nocturnal ETCO2 < 45 mm Hg, between 45 and 50 mm Hg, and > 50 mm Hg.

All polysomnograms were recorded on Polysmith systems (Nihon Kohden, Foothill Ranch, CA), and scored using American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines.2 Capnometry data were obtained from calibrated Nonin RespSense devices (Plymouth, MN) interfaced to the Polysmith system. Those devices use a sidestream technology, with sampling obtained through oral/nasal cannulas (Salter labs, Arvin, CA). The sampling flow into the sample cell was 75 mL/min, the total system response time (including delay and rise times) was 4 sec, and the sampling rate for the capnograph tracing was 4 Hz. Apnea was defined as a drop in the peak thermal sensor excursion by ≥ 90% from baseline lasting ≥ 10 seconds. For the purpose of this study, a hypopnea was scored if the event met either the recommended or alternative definitions of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (i.e., a drop in the nasal pressure signal excursion ≥ 30% from baseline for ≥ 10 sec in association with ≥ 4% oxygen desaturation, or ≥ 50% drop with ≥ 3% desaturation or an arousal).2

The quality of the oximetry and capnographic data was assessed by review of the pulse plethysmographic signal and capnographic waveforms, with exclusion of artifacts of oximetry due to loss of the pulse signal, and exclusion of CO2 waveforms without a clearly identified plateau, including those associated with deterioration of the signal due to obstructive events.

We collected demographic and polysomnographic variables at the time of the PSG: age, sex, body mass index, Epworth Sleepiness Scale score, sleep efficiency, sleep and REM latencies, sleep stage distribution, arousal index, apnea-hypopnea index, nadir oxygen saturation, and time spent below 90% oxygen saturation (as percent of total sleep time). Capnometric data were obtained from the trend report of the Polysmith system, and included stable awake end-tidal CO2 at the beginning of the study before the onset of slow-rolling eye movements (evening awake ETCO2), after completion of the sleep study just before the final calibrations (morning awake ETCO2), and sleep ETCO2. The latter included minimum and maximum sleep ETCO2 and the following 3 time intervals: percents of total sleep time spent with ETCO2 < 45 mm Hg (T45), between 45-50 mm Hg (T45_50), and > 50 mm Hg (T50). An integrated overnight CO2 was calculated as the sum of the products of the estimated average ETCO2 at each of those 3 time intervals by the percent of total sleep time spent at each corresponding time interval: [T45*(45 + minimum ETCO2) / 2] + [T50*(50 + maximum ETCO2) / 2] + [T45_50 *47.5]. The result was divided by 100 to provide an estimate of nocturnal ETCO2 had it remained constant through the night.

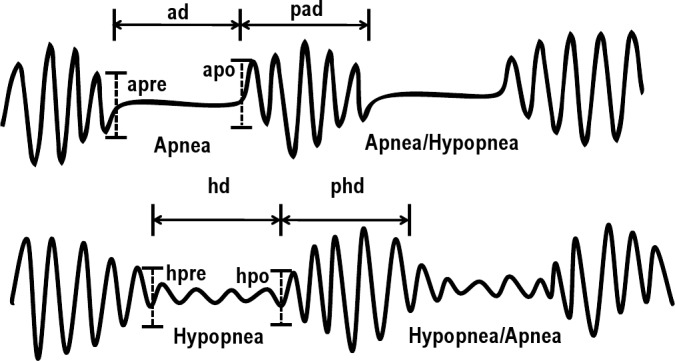

Respiratory event (subsuming apneas and hypopneas) and inter-event durations were measured in seconds. Inter-event durations were measured only if the subsequent respiratory event was within 30 sec from the termination of the preceding event. Pre-event and post-event breathing amplitudes were semi-quantitatively measured on the nasal pressure transducer signal on 60-sec epochs, as the amplitude of the last breath before the corresponding respiratory event and of the first breath after that event respectively (Figure 1). To compensate for expected variation in amplitudes as may occur with positional changes or migration of the oral/nasal cannula, the mean post-event amplitude was referenced to the mean pre-event amplitude.

Figure 1. Schema illustrating event and inter-event duration, as well as pre-and post-event amplitude (with upward deflection of flow during inspiration).

Inter-event durations were included only if the subsequent respiratory event was within 30 sec from the termination of the preceding event. ad: apnea duration, pad: post apnea duration, hd: hypopnea duration, phd: post-hypopnea duration, apre and apo: pre- and post-apnea amplitude respectively, hpre and hpo: pre- and post-hypopnea amplitude, respectively. For each patient the mean of all event and inter-event durations across the polysomnography was derived and expressed in the text or tables as AD, PAD, HD, and PHD. Similarly, the mean of all pre-event amplitude and the mean of all post-event amplitudes was derived and expressed in the text as Apre, Apo, Hpre, and Hpo.

The onset and offset of apneas and hypopneas were respectively placed at the nadir of the last normal breath and at the start of the first subsequent normal breath approximating the baseline (Figure 1).2 If the baseline amplitude could not be easily determined, the respiratory events were also terminated as per the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines when there was a clear and sustained increase in post-event breathing amplitude, or re-saturation of ≥ 2%.2

For each patient we derived: mean apnea and mean hypopnea duration (AD and HD respectively), mean post-apnea and mean post-hypopnea duration (PAD and PHD), mean post-apnea and mean post-hypopnea amplitude (Apo and Hpo) expressed relative to the mean pre-apnea and mean pre-hypopnea amplitude (Apre and Hpre).

Sample size was estimated at 30 subjects based on a minimum meaningful correlation coefficient of 0.50, a power of 0.9, and α of 0.05.14 Groups were compared using a χ2 for categorical variables, and analysis of variance for continuous variables. The correlation between integrated overnight CO2 and demographic and polysomnographic variables was determined by the Pearson correlation coefficient. Comparison of correlations within a single sample was done using the Williams T2 statistic.15 Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to estimate the influence of covariates on the overnight CO2. Collinearity was measured by means of tolerance and the Variance Inflation Factor. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS, version 11.5. The study was approved by our institutional review board.

RESULTS

Forty-four consecutive studies meeting the inclusion criteria were selected such that maximal ETCO2 during sleep was < 45 mm Hg in 15 studies, between 45 and 50 mm Hg in 14 studies, and > 50 mm Hg in 15 studies. The mean age of the patients was 51 years (standard deviation 14, range 18-92), mean apnea-hypopnea index was 28 events/h (standard deviation 21, range 5.1-105), and the mean body mass index was 34 kg/m2 (standard deviation 9, range 20-57). There were 24 females and 19 males. None had a diagnosis of obesity-hypoventilation. There were no significant differences between genders in the body mass index, apnea-hypopnea index, mean apnea duration, mean post-apnea duration, and mean post-event to mean pre-event ventilation, though women tended to be older than men (54 vs. 47 years, respectively, p = 0.06), and to have a smaller neck circumference (38.7 vs. 41.4 cm, respectively, p = 0.07).

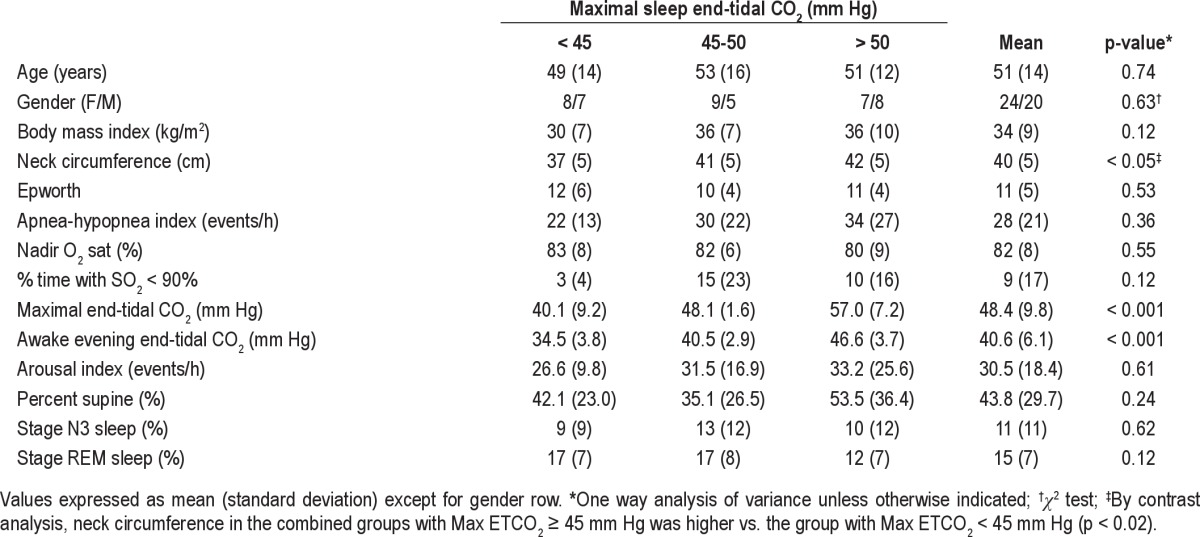

Demographic, polysomnographic, and laboratory data categorized by level of maximal ETCO2 reached during the sleep study are shown in Table 1. Neck circumference was higher in the combined groups with maximal ETCO2 ≥ 45 mm Hg compared to the group with maximal ETCO2 < 45 mm Hg (Table 1). Sleep efficiency, percentages of time spent at different sleep stages, percent of time in the supine position, arousal indices, and sleep and REM latency were not significantly different between the 3 groups.

Table 1.

Demographic, laboratory, and polysomnographic variables at baseline

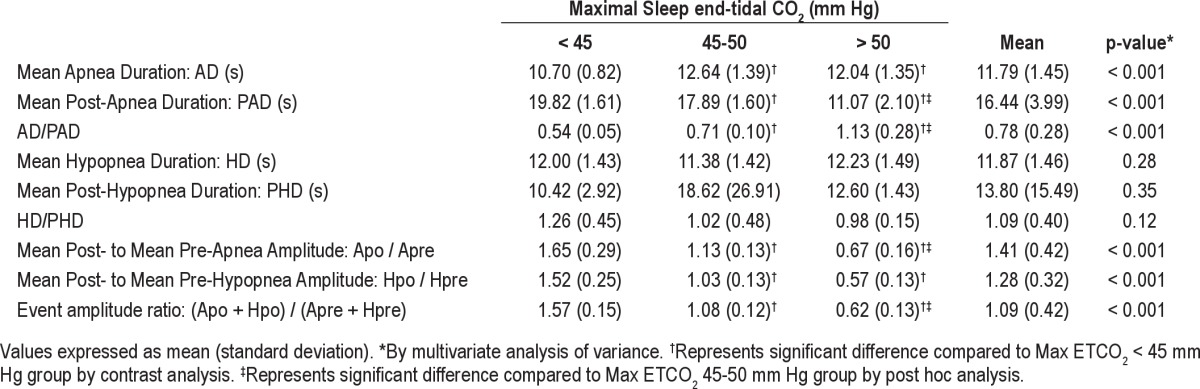

Groups with progressively higher maximal ETCO2 had progressively shorter mean post-apnea duration, increased AD/PAD, and a smaller mean post-event to mean pre-event amplitude ratio (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of possible variables predictive of end-tidal CO2 during sleep

There was a trend towards a positive correlation between the integrated overnight CO2 and age (r = 0.29, p = 0.06), as well as body mass index (r = 0.29, p = 0.06), and no significant correlation with apnea-hypopnea index, neck circumference, Epworth Sleepiness Scale score, sleep efficiency, sleep stages, percent time in the supine position, and percent time with oxygen saturation < 90%.

The REM latency correlated negatively with mean post-apnea duration (r = -0.41, p = 0.006), whereas REM time as percent of total sleep time correlated positively with the mean post-apnea duration (r = 0.34, p = 0.03).

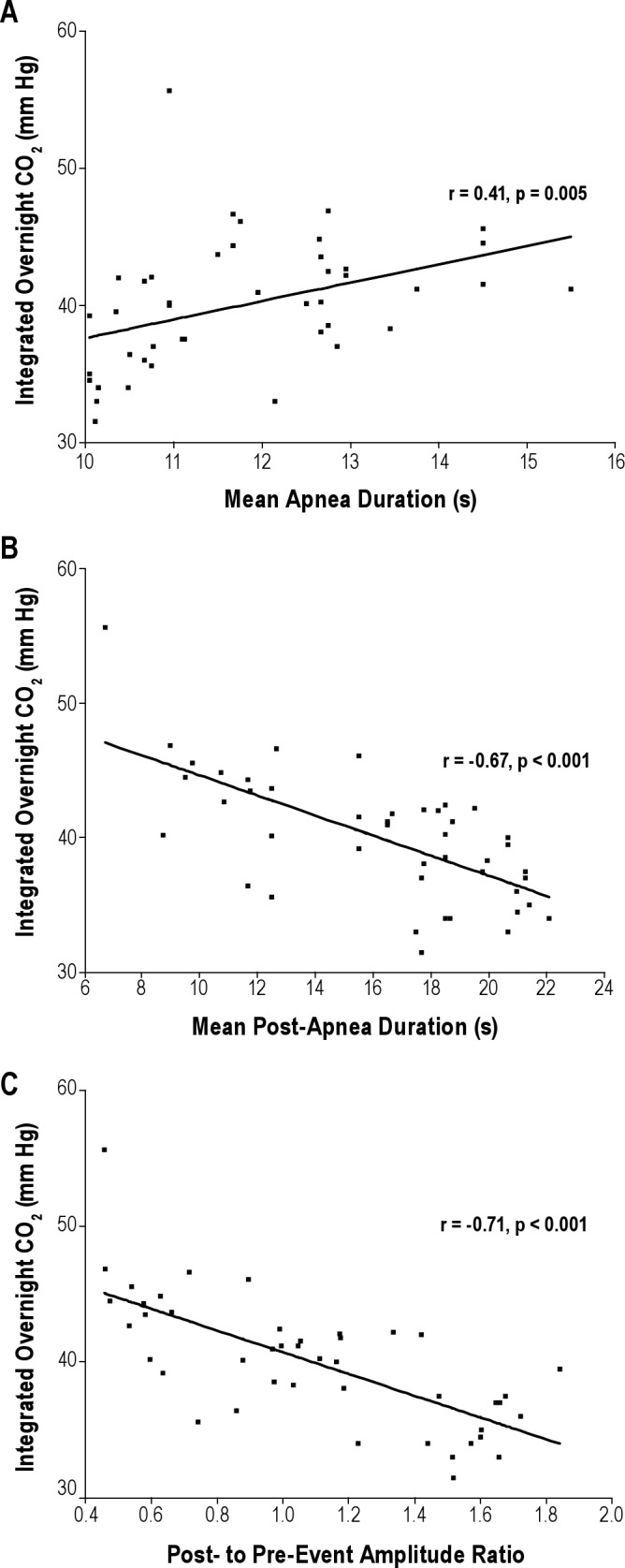

The integrated overnight CO2 correlated with mean apnea duration (r = 0.41, p = 0.005) (Figure 2A), and mean-post apnea duration (r = -0.67, p < 0.001) (Figure 2B). The correlation of the integrated overnight CO2 with mean hypopnea duration or mean post-hypopnea duration was very poor and nonsignificant (r = -0.10, p = 0.53 and r = 0.11, p = 0.50, respectively). There was no difference between apnea and hypopneas as far as the correlation between the integrated overnight CO2 and the post-event relative to pre-event amplitude, with comparable correlation coefficients (p = 0.30), slopes, and intercepts. Therefore a mean post-event to mean pre-event (combining apneas and hypopneas) amplitude ratio was calculated, with which the integrated overnight CO2 was also correlated (r = -0.71, p < 0.001) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Scatter plots of the integrated overnight CO2 against mean apnea duration (A), mean post-apnea duration (B), and mean post-to mean pre-event amplitude ratio (C), with regression line, correlation coefficient, and significance.

Each point represents one patient.

The evening and morning awake ETCO2 were nearly identical and closely correlated (40.7 ± 6.2 vs. 40.5 ± 5.8 mm Hg, respectively; r = 0.81, p < 0.001). The evening awake ETCO2 correlated positively with mean apnea duration (r = 0.42, p = 0.004), inversely with mean post-apnea duration (r = -0.81, p < 0.001), and inversely with mean post- to mean pre-event amplitude ratio (r = -0.80, p < 0.001).

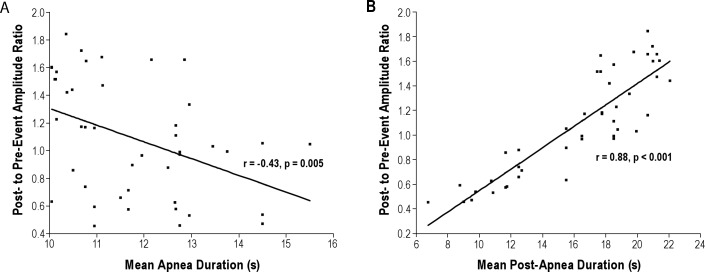

Cross-correlation analysis indicated that collinearity was a concern, as the mean post-event to mean pre-event amplitude ratio was correlated with mean apnea duration (r = -0.43, p = 0.005), and particularly with mean post-apnea duration (r = 0.88, p < 0.001) (Figure 3). However, mean post-apnea duration was not correlated with mean apnea duration (r = -0.25, p = 0.10).

Figure 3. Scatter plots of the mean post-event amplitude to mean pre-event amplitude ratio against mean apnea duration (A), and mean post-apnea duration (B), with regression line, correlation coefficient, and significance.

Each point represents one patient.

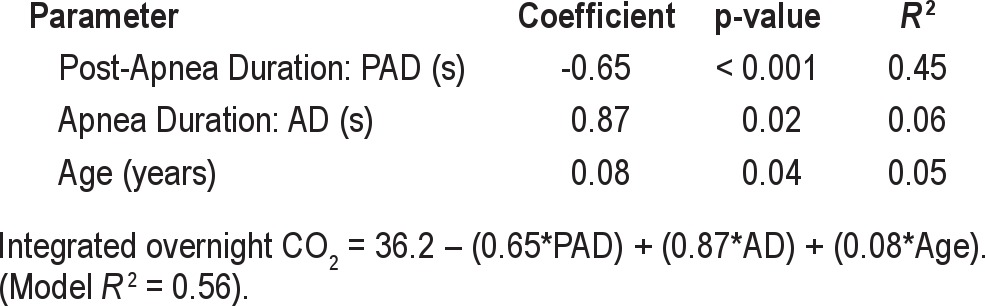

In a multivariable regression model, mean post-apnea duration, mean apnea duration, and age were each independently correlated with the integrated overnight CO2: mean post-apnea duration contributing the most to the variance in integrated overnight CO2 (45%), with mean apnea duration and age contributing an additional 6% and 5%, respectively, such that the total model explained 56% of the variance in integrated overnight CO2 (Table 3). The body mass index and apnea-hypopnea index were not significantly correlated with the integrated overnight CO2 in the multivariable model (p = 0.17 and 0.47, respectively).

Table 3.

Multiple regression of post-apnea duration, apnea duration, and age as predictors of the integrated overnight CO2

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that, in patients with obstructive apnea: (1) A shorter post-apnea duration is a greater contributor to an elevated integrated overnight CO2 than apnea duration, with older age as an additional lesser contributor; (2) Post-hypopnea amplitude is equally as important as the post-apnea amplitude with post-event relative to pre-event (combining apneas and hypopneas) amplitude contributing to the integrated overnight CO2, but also correlating strongly with apnea duration and post-apnea duration; (3) Post-apnea duration is not correlated with apnea duration; (4) The apnea-hypopnea index, body mass index, hypopnea duration, and post-hypopnea duration are not important contributors to the overnight CO2; and (5) The baseline awake end-tidal CO2 also correlated positively with mean apnea duration, and inversely with mean post-apnea duration and post-event amplitude relative to pre-event amplitude.

In our study, the post-event to pre-event amplitude ratio was tightly correlated with post-apnea duration (Figure 3B), suggesting that a common pathophysiologic mechanism, possibly airway collapsibility, underlies those two measures, and may explain our finding of an association between longer post-apnea duration and a more favorable REM architecture (with both a shorter REM latency and increased REM sleep). For instance, stable breathing correlated with passive collapsibility of the airway in patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnea.16 Consequently, multi-collinearity was seen between post-apnea duration and post-event to pre-event amplitude. Although ventilatory measures such as breath amplitude may be as important as post-apnea duration, the individual contribution of each of those two variables to the overnight integrated CO2 is difficult to discern in the context of collinearity. We therefore included only the apnea and post-apnea durations in the final model shown in Table 3, because durations were more sharply defined, less subject to variability in measurements (compared to amplitudes), limited to apneas (and therefore independent of the various hypopnea definitions), and independent of correction measures (such as square root modification of the nasal pressure amplitude signal17,18) to compensate for the nonlinear nasal pressure to flow relationship.

However, once the airway has collapsed and an apnea or hypopnea begun, the duration of the obstructive events may depend on factors other than collapsibility such as the arousal threshold. For instance, since arousals terminate an obstructive event, apnea duration has been considered a surrogate of the arousal threshold.19 These proposals, with separate determinants of apnea duration and post-apnea duration, are consistent with the absence of an inverse correlation between those two variables in our study as well as other studies.12

The integrated overnight CO2, did not correlate with hypopnea and post-hypopnea durations, perhaps reflecting the shape of the relationship between CO2 and ventilation (the metabolic hyperbola), such that the reduced ventilation during hypopneas, was either sufficient to prevent an increase in arterial CO2, or decreased our ability to detect such an effect within the technical constraints of our study. In that regard, the most important constraint is our removal of data associated with deterioration of the capnographic waveforms during obstructive events. This may have resulted in an underestimation of the true overall nocturnal CO2, and perhaps explain why apnea duration was not as strong a predictor of nocturnal CO2 as post-apnea duration in our study (an alternative explanation may be the constraint of the conventional 10-second threshold to the apnea definition). Note that loss of the capnographic signal during obstruction, which is considered an artifact in our study, has been used diagnostically to detect apneas,3 such that the lowered overnight end-tidal CO2, was shown to be associated with the apnea-hypopnea index severity.4 We confirm the results of other studies showing a relationship between a longer apneas or shorter post-apnea duration with a higher awake arterial CO2,12,20 and between an impaired post-event ventilatory response and a higher awake arterial CO2.10,11 Our study extends those results and demonstrates that, in individuals with obstructive sleep apnea, gradations of the awake CO2 even within the normal range, reflect events occurring during sleep, with elevation of nocturnal carbon dioxide as a possible intermediary step associated with shorter post-apnea duration, with lesser contributions from longer apnea duration, and increased age.

In contrast, we found that the apnea-hypopnea index was not a significant predictor of the integrated overnight CO2, and that the body mass index trended towards a poor correlation with the integrated overnight CO2, though both are important determinants of daytime hypercapnia in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea.9 A potential explanation for those findings is that, beyond causing variations of awake CO2 within the normal range, inciting events to nocturnal hypercapnia (such as lower post-event ventilation, longer apnea duration, shorter post-apnea duration) require other factors (such as the apnea-hypopnea index or body mass index) for the transition to daytime hypercapnia. For instance, obese patients, and especially those with the metabolic syndrome, have a higher resting metabolic rate compared to non-obese patients21,22 but also have a decrease in metabolic rate during sleep in direct proportion to the body mass index.21 The resting to sleep differential in the metabolic rate based on body mass index, may explain the stronger contribution of the body mass index to the development of daytime as opposed to nocturnal hypercapnia.

Our findings do not establish whether an impairment of ventilation (as determined by apnea and post-apnea duration, or post-ventilation relative to pre-ventilation) determines ETCO2, or whether elevation in the ETCO2 impairs ventilation. However, progressive hypercapnia above a certain threshold improves upper airway stability in a linear fashion.23–25 This pharyngeal chemosensitivity parallels the control gain of central and peripheral chemoreceptors, with the net effect that increased CO2 protects and increases ventilation. Our findings are therefore more consistent with a ventilatory impairment in the balance between the accumulation of CO2 (longer apnea duration) and perhaps more importantly the unloading of CO2 (longer post-apnea duration) leading to nocturnal then daytime elevation of CO2.

Our study expands the indications of capnometry during polysomnography beyond its current contexts of apnea detection and quantification of the hypoventilation syndromes5 to its use as a reflection of the pathophysiology, severity, or ventila-tory burden of sleep apnea, which may not be fully captured by the apnea-hypopnea index. These findings may have both diagnostic and prognostic clinical implications, as exhaled CO2 may be a physiologic marker of disease severity that is independent of the apnea-hypopnea index, reflects the balance between event and inter-event duration, and may be an intermediary stage towards the development of daytime hypercapnia in some individuals. Advances in methods of exhaled breath analysis may broaden the role of exhaled CO2 as a diagnostic tool and therapeutic target in patients with sleep apnea.26

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Nancy Foldvary-Schaefer for her thoughtful review of the manuscript, and Nengah Hariadi and Jie Zeng for technical support. Work for this study was performed at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH. Raed A. Dweik is supported by the following grants: HL081064, HL107147, HL095181, and RR026231 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and BRCP 08-049 Third Frontier Program grant from the Ohio Department of Development (ODOD).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AD

mean apnea duration

- Apo

mean post-apnea amplitude

- Apre

mean pre-apnea amplitude

- ETCO2

end-tidal CO2

- HD

mean hypopnea duration

- Hpo

mean post-hypopnea amplitude

- Hpre

mean pre-hypopnea amplitude

- PAD

mean post-apnea duration

- PHD

mean post-hypopnea duration

References

- 1.Beck SE, Marcus CL. Pediatric Polysomnography. Sleep Med Clin. 2009;4:393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL, Quan SF. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magnan A, Philip-Joet F, Rey M, Reynaud M, Porri F, Arnaud A. End-tidal CO2 analysis in sleep apnea syndrome. Conditions for use. Chest. 1993;103:129–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weihu C, Jingying Y, Demin H, Yuhuan Z, Jiangyong W. End-tidal carbon dioxide concentration monitoring in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Am J Otolaryngol. 2011;32:190–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redline S, Budhiraja R, Kapur V, et al. The scoring of respiratory events in sleep: reliability and validity. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:169–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stock MC. Capnography for adults. Crit Care Clin. 1995;11:219–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasuya Y, Akca O, Sessler DI, Ozaki M, Komatsu R. Accuracy of postoperative end-tidal Pco2 measurements with mainstream and sidestream capnography in non-obese patients and in obese patients with and without obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:609–15. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b060b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders MH, Kern NB, Costantino JP, et al. Accuracy of end-tidal and transcutaneous PCO2 monitoring during sleep. Chest. 1994;106:472–83. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.2.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaw R, Hernandez AV, Walker E, Aboussouan L, Mokhlesi B. Determinants of hypercapnia in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea. A systematic review and metaanalysis of cohort studies. Chest. 2009;136:787–96. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger KI, Ayappa I, Chatr-Amontri B, et al. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome as a spectrum of respiratory disturbances during sleep. Chest. 2001;120:1231–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger KI, Ayappa I, Sorkin IB, Norman RG, Rapoport DM, Goldring RM. Poste-vent ventilation as a function of CO2 load during respiratory events in obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:917–24. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01082.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayappa I, Berger KI, Norman RG, Oppenheimer BW, Rapoport DM, Goldring RM. Hypercapnia and ventilatory periodicity in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1112–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-212OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hulley SB. Designing clinical research. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiger JH. Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychol Bull. 1980;87:245–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Younes M. Contributions of upper airway mechanics and control mechanisms to severity of obstructive apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:645–58. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200302-201OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montserrat JM, Farre R, Ballester E, Felez MA, Pasto M, Navajas D. Evaluation of nasal prongs for estimating nasal flow. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:211–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurnheer R, Xie X, Bloch KE. Accuracy of nasal cannula pressure recordings for assessment of ventilation during sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1914–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2102104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zirlik S, Schahin SP, Premm W, Hahn EG, Fuchs FS. Lung volumes and mean apnea duration in obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;168:303–5. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger KI, Ayappa I, Sorkin IB, Norman RG, Rapoport DM, Goldring RM. CO2 homeostasis during periodic breathing in obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:257–64. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang K, Sun M, Werner P, et al. Sleeping metabolic rate in relation to body mass index and body composition. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:376–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarantino G, Marra M, Contaldo F, Pasanisi F. Basal metabolic rate in morbidly obese patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Invest Med. 2008;31:E24–9. doi: 10.25011/cim.v31i1.3138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliven A, Odeh M, Gavriely N. Effect of hypercapnia on upper airway resistance and collapsibility in anesthetized dogs. Respir Physiol. 1989;75:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(89)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz AR, Thut DC, Brower RG, et al. Modulation of maximal inspiratory airflow by neuromuscular activity: effect of CO2. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:1597–605. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seelagy MM, Schwartz AR, Russ DB, King ED, Wise RA, Smith PL. Reflex modulation of airflow dynamics through the upper airway. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:2692–700. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.6.2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dweik RA, Amann A. Exhaled breath analysis: the new frontier in medical testing. J Breath Res. 2008;2:1–3. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/2/3/030301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]