Abstract

Study Objectives:

To determine the impact of nocturia on objective measures of sleep in older individuals with insomnia.

Methods:

The sleep and toileting patterns of a group of community-dwelling older men (n = 55, aged 64.3 ± 7.52 years) and women (n = 92, aged 62.5 ± 6.73 years) with insomnia were studied for two weeks using sleep logs and one week using actigraphy. The relationships between nocturia and various sleep parameters were analyzed with ANOVA and linear regression.

Results:

More than half (54.2% ± 39.9%) of all log-reported nocturnal awakenings were associated with nocturia. A greater number of trips to the toilet was associated with worse log-reported restedness (p < 0.01) and sleep efficiency (p < 0.001), as well as increases in actigraph-derived measures of the number and length of nocturnal wake bouts (p < 0.001) and wake after sleep onset (p < 0.001). Actigraph-determined wake bouts were 11.5% ± 23.5% longer on nights on which there was a trip to the toilet and wake after sleep onset was 20.8% ± 33.0% longer during these nights.

Conclusions:

Nocturia is a common occurrence in older individuals with insomnia and is significantly associated with increased nocturnal wakefulness and decreased subjective restedness after sleep.

Commentary:

A commentary on this article appears in this issue on page 263.

Citation:

Zeitzer JM; Bliwise DL; Hernandez B; Friedman L; Yesavage JA. Nocturia compounds nocturnal wakefulness in older individuals with insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2013;9(3):259-262.

Keywords: Aging, nocturia, sleep initiation and maintenance disorders, humans, sleep, actigraphy

Insomnia, especially experienced as difficulty maintaining sleep, is quite common in older individuals, with epidemiologic studies indicating rates of 40% to 70%.1 Numerous age-related changes are thought to increase the likelihood of insomnia in senescence, including changes to the circadian timing system and sleep homeostatic mechanisms, decreased arousal threshold, increased rates of anxiety, pain, and depression, and generally poor health.1 While all of these factors might contribute to the decline of sleep continuity in older adults, the overwhelming reason given by older adults themselves is that their sleep is disturbed because they need to get up to urinate (nocturia). Between two-thirds and three-quarters of older individuals surveyed in epidemiological studies report that their sleep is disturbed because of nocturia.2–6 The majority report that nocturia is the only reason their sleep is disturbed.2–6 Further, survey studies have shown that the greater the number of nocturnal voids, the greater the self-described poor sleep, insomnia symptoms, and daytime sleepiness.7–15 For those individuals who report nocturia as bothersome there is even a stronger correlation with disturbed sleep.13,16

As noted, to date, no study of the relationship between sleep and nocturia has used objective measurements of sleep, nor have previous studies examined the relationship between sleep and nocturia prospectively, on a night-to-night basis. Such data could enable the comparison of nights with or without nocturia in the same individual. To fill this gap, we here report on the relationship between objective and subjective measures of sleep and nocturia collected prospectively from a group of healthy, community-dwelling older adults over a two-week period.

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Despite the overwhelming preponderance of older individuals who indicate that nocturia is the primary cause of their sleep disruption, there is relatively little objective data to support this assertion. There is also scant data on the interrelationship between nocturia and insomnia.

Study Impact: Our data indicate that nocturia compounds the negative impact of insomnia. Mitigation of the alerting aspects of nocturia-associated behaviors may enable an improvement in sleep.

METHODS

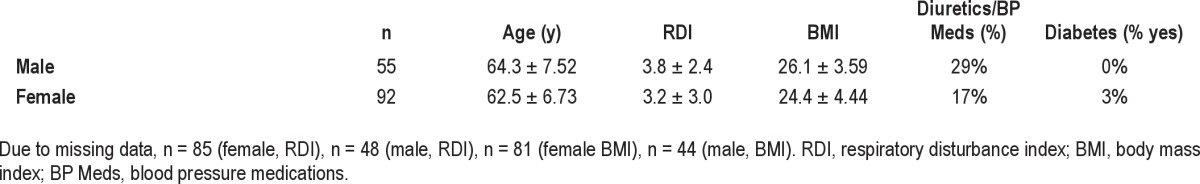

A group of community-dwelling older men (n = 55, aged 64.3 ± 7.52 years) and women (n = 92, aged 62.5 ± 6.73 years) were recruited for a research study of insomnia and aging. All subjects had a self-reported complaint of insomnia and were recruited into the study specifically on this complaint. Presence or absence of nocturia was not a consideration in recruitment. To establish a baseline sleep pattern, all subjects had 2 weeks of sleep logs, and a subset (n = 60: 44 women and 16 men) had an additional week of wrist actigraphy. Sleep logs were used to collect information concerning daily timing (i.e., bedtime, wakeup time) of sleep, subjective quality of “restedness” in the morning (Likert-like scale from 1-7 with 1: “not at all rested,” 4: “moderately rested,” and 7: “very rested”), the number of nocturnal awakenings, the time it took to fall asleep, and the number of times that subjects woke to use the bathroom. We collected 12.1 ± 3.39 days of sleep logs per subject. Not all logs were fully completed, resulting in some missing data. Of the 1,786 days of logs, 1,774 had information concerning the number of trips to the bathroom, 1,108 had information concerning morning restedness, and 1,784 had sleep timing data. Sleep efficiency [(time in bed − time awake) / time in bed] was calculated from the self-reported sleep data. Wrist actigraphy collects arm movement data by means of a wrist-worn device that contains a 3-dimensional accelerometer. From these data, sleep and, notably, the occurrence of wakefulness during sleep are inferred.17 Actigraphy data were collected with an Actiwatch-L (Minimitter, Bend OR) for 7 days in 58 subjects and 6 days in 2 subjects. Sleep was determined using the built-in algorithms in the Actiware-Sleep software (v.3.1, Mini-Mitter, Bend OR). Sleep efficiency, the number and length of nocturnal wake episodes, and the overall amount of wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO) were all calculated from actigraph data. Subjects also had one night of at-home recording of breathing parameters (EdenTrace, Mallinckrodt, Hazelwood, MO) from which the respiratory disturbance index (RDI) was calculated. Data were scored based on the Chicago Criteria18 for hypopneas and discernable apneas; RDI was calculated using self-reported sleep times. Due to technical problems, 14 of the 147 recordings were unavailable.

Data were analyzed using several different approaches. Initially, we examined all actigraphic data from individual nights for individual subjects, classifying each night by the number of logged nocturnal bathroom visits. These data were analyzed both continuously and categorically (i.e., 0/1/2/3/4 or more) using linear regression and analysis of variance (ANOVA), respectively (OriginPro8, Origin Lab, Northampton MA). Secondly, in order to examine the relationships between nocturnal bathroom trips and sleep quality on a within subject basis, we examined the data of the 19 subjects who during the one week of actigraphy data collection had ≥ 2 nights on which they went to the bathroom at least once and ≥ 2 nights on which they did not use the bathroom after going to bed. For each of these nights, we calculated percent difference from the one-week average for each sleep variable of interest. The average percent difference was calculated for toileting and non-toileting nights and pairwise comparisons made. Data throughout the manuscript are shown as mean ± SD.

Prior to the collection of any data, subjects signed a consent form approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. All procedures conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

Subjects (Table 1) reported 1.4 ± 1.2 trips to the bathroom per night (range 0-9) and 2.4 ± 1.6 nocturnal awakenings per night (range 0-15). More than half (54.2% ± 39.9%) of all nocturnal awakenings were associated with using the bathroom. As these subjects were all recruited for the presence of self-reported insomnia, they had generally poor sleep efficiency with a not unexpected difference between the subjective (sleep log) and objective (actigraphy) measures of sleep efficiency (67.8% ± 16.9% and 79.2% ± 9.74%, respectively). When limiting the analysis to sleep data collected by log and actigraph concomitantly, the subjective sleep efficiency was similarly poor (67.1% ± 16.1% by sleep log). Given their poor sleep, subjects reported being only moderately rested (3.8 ± 1.5; scale = 1-7, with 7 being the most rested). Subjects were relatively free of sleep-related breathing disruption, as the RDI was 3.44 ± 2.85 and only 2 subjects had an RDI > 10. Thus, older subjects with a primary complaint of insomnia slept poorly and getting up to use the bathroom was associated with more than half of all nocturnal awakenings.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

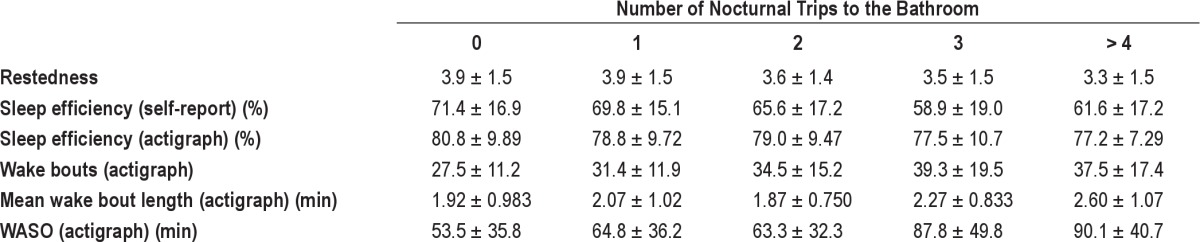

Data for individual nights, subdivided by the number of trips to the bathroom at night, are presented in Table 2. The number of trips to the bathroom at night was negatively associated with subjective measures of restedness (r = -0.13, linear regression; F4,1093 = 4.27, p < 0.01 ANOVA) and sleep efficiency (r = -0.22, linear regression; F4,1768 = 24.5, p < 0.001 ANOVA). The number of trips to the bathroom at night was positively associated with objective, actigraph-derived measures of sleep disruption, including the number of nocturnal wake bouts (r = 0.23, linear regression; F6,409 = 5.03, p < 0.001 ANOVA), the mean length of the nocturnal wake bouts (r = 0.13, linear regression; F6,409 = 3.48, p < 0.01 ANOVA), and the overall WASO (r = 0.24, linear regression; F6,409 = 5.66, p < 0.001 ANOVA). The relationship between objective (actigraph-derived) sleep efficiency and the number of trips to the bathroom at night was mixed, with a weak linear relationship (r = -0.099, p < 0.05, linear regression), but no categorical relationship (F4,411 = 1.24, p = 0.29 ANOVA). Splitting the data into nights with or without a trip to the bathroom did reveal a difference in objective sleep efficiency (p < 0.05, 2-tailed t-test), with lower sleep efficiency occurring on nights with a trip to the bathroom. Since common factors (e.g., age, sex, RDI, body mass index, diabetes, use of diuretics; see Table 1) might be related to the number of trips to the bathroom, we examined each of the linear relationships detailed above using multiple regression. In an initial regression analysis, we found that age (p < 0.001), RDI (p < 0.001), body mass index (p < 0.01), and use of diuretics (p < 0.05), but not sex (p = 0.12), were related to the number of trips to the bathroom at night. These factors were, therefore, included in the multiple regression models. After adjusting for these factors, subjective (restedness, sleep efficiency) and objective (number of wake bouts, mean length of wake bouts, WASO, sleep efficiency) measures were all still significantly related to the number of trips to the bathroom at night. In toto, it appears that going to the bathroom at night is associated with signifi-cant subjective and objective disruption of nocturnal sleep.

Table 2.

Sleep parameters and their association with using the toilet at night

In the subset of subjects with ≥ 2 nights of bathroom use and ≥ 2 nights of no bathroom use, pairwise comparisons of the length of wake bouts indicated that bouts were 11.5% ± 23.5% longer on nights on which there was a trip to the bathroom (p < 0.05, paired t-test). Similarly, WASO was 20.8% ± 33.0% longer on nights on which there was a trip to the bathroom (p < 0.05, paired t-test). There were no differences in total sleep time (p = 0.18), the length of sleep bouts (p = 0.52), or the number of sleep (p = 0.12) or wake (p = 0.15) bouts. Thus, nocturia appears to be associated with the length of individual nocturnal wake episodes without affecting the overall amount or structure of sleep as imputed through actigraphy.

DISCUSSION

Our data indicate that toileting at night is a common occurrence in older individuals with insomnia, significantly associated with the amount of wakefulness occurring during the night and decreasing subjective restedness after sleep. Previous epidemiological work relying on self-reported sleep has described the negative relationship between subjective sleep quality and nocturia, as well as the common occurrence of nocturia in older individuals. More recently, data from the Sleep Heart Health Study have indicated that more general characteristics of nocturia summarized over a one-month interval were related to poorer quality sleep on a single night of polysomnography.19 Our work extends this research as it provides the first objective measurement of sleep disruption and its association with nocturia on nights in which both were documented simultaneously. Nocturia appears to worsen the already poor sleep of individuals with insomnia, perhaps by providing a stimulus for waking which is then often accompanied with turning on the lights (further decreasing sleepiness)20 and an opportunity for a lengthy awakening.21 The ultimate question remains whether the urge or need for urination causes the awakening, or after awakening due to another cause, an individual then feels the urge or need to urinate. This is more than an esoteric question since the answer could help guide therapeutic intervention, as is evinced by current experimental protocols.22

Our study is not without its limitations. We were unable to capture which of the awakenings were associated with the trips to the bathroom. Further, although actigraphy is useful in determining overall amounts of wakefulness during a sleep episode, it is not as accurate as polysomnography in determining the precise length of specific awakenings. Future research studies should use polysomnography and objective urination monitoring to better delineate the effects of nocturia on sleep.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Zeitzer is a PI for a study funded by Vanda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Bliwise has consulted for Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research is supported by grant R01 AG 12914 (NIA), by the Medical Research Service of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, and by the Department of Veterans Affairs Sierra-Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC).

References

- 1.Van Someren EJW. Circadian rhythms and sleep in human aging. Chronobiol Intl. 2000;17:233–43. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bing MH, Moller LA, Jennum P, et al. Prevalence and bother of nocturia, and causes of sleep interruption in a Danish population of men and women aged 60-80 years. BJU Int. 2006;98:599–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Middelkoop HA, Smilde-van den Doel DA, Neven AK, et al. Subjective sleep characteristics of 1,485 males and females aged 50-93: effects of sex and age, and factors related to self-evaluated quality of sleep. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51:M108–M115. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.3.m108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maggi S, Langlois JA, Minicuci N, et al. Sleep complaints in community-dwelling older persons: prevalence, associated factors, and reported causes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:161–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohayon MM. Nocturnal awakenings and comorbid disorders in the American general population. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gentili A, Weiner DK, Kuchibhatil M, et al. Factors that disturb sleep in nursing home residents. Aging (Milano) 1997;9:207–13. doi: 10.1007/BF03340151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asplund R, Åberg H. Health of the elderly with regard to sleep and nocturnal micturition. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1992;10:98–104. doi: 10.3109/02813439209014044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asplund R, Åberg H. Nocturnal micturition, sleep and well-being in women of ages 40-64 years. Maturitas. 1996;24:73–81. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)01021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asplund R. Nocturia in relation to sleep, somatic diseases and medical treatment in the elderly. BJU Int. 2002;90:533–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rembratt A, Norgaard JP, Andersson KE. Nocturia and associated morbidity in a community-dwelling elderly population. BJU Int. 2003;92:726–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bliwise DL, Foley DJ, Vitiello MV, et al. Nocturia and disturbed sleep in the elderly. Sleep Med. 2009;10:540–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gopal M, Sammel MD, Pien G, et al. Investigating the associations between nocturia and sleep disorders in perimenopausal women. J Urol. 2008;180:2063–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimura K, Oka Y, Kamoto T, et al. Differences and associations between nocturnal voiding/nocturia and sleep disorders. BJU Int. 2010;106:232–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coyne KS, Zhou Z, Bhattacharyya SK, et al. The prevalence of nocturia and its effect on health-related quality of life and sleep in a community sample in the USA. BJU Int. 2003;92:948–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2003.04527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai T, Gardener N, Abraham L, et al. Impact of surgical treatment on nocturia in men with benign prostatic obstruction. BJU Int. 2006;98:799–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaughan CP, Eisenstein R, Bliwise DL, et al. Self-rated sleep characteristics and bother from nocturia. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:369–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, et al. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003;26:342–92. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep. 1999;22:667–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parthasarathy S, Fitzgerald M, Goodwin JL, et al. Nocturia, sleep-disordered breathing, and cardiovascular morbidity in a community-based cohort. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cajochen C, Zeitzer JM, Czeisler CA, et al. Dose-response relationship for light intensity and ocular and electroencephalographic correlates of alertness in humans. Beh Brain Res. 2000;115:75–83. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klerman EB, Davis JB, Duffy JF, et al. Older people awaken more frequently but fall back asleep at the same rate as younger people. Sleep. 2004;27:793–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaughan CP, Endeshaw Y, Nagamia Z, et al. A multicomponent behavioural and drug intervention for nocturia in elderly men: rationale and pilot results. BJU Int. 2009;104:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]