Abstract

Cell fate determination is an important process in multicellular organisms. Plant epidermis is a readily-accessible, well-used model for the study of cell fate determination. Our knowledge of cell fate determination is growing steadily due to genetic and molecular analyses of root hairs, trichomes, and stomata, which are derived from the epidermal cells of roots and aerial tissues. Studies have shown that a large number of factors are involved in the establishment of these cell types, especially members of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) superfamily, which is an important family of transcription factors. In this mini-review, we focus on the role of bHLH transcription factors in cell fate determination in Arabidopsis.

Keywords: bHLH transcription factor, epidermal cell fate determination, trichome, root hair and stomata

A fundamental aspect of the development of multicellular organisms is the specification of different cell types at the appropriate time and place.1 During higher plant development, cells descended from the same zygote adopt different cell fates and experience diverse differentiation programs to form an integrated plant.2 Most of our knowledge of cell fate determination is derived from the study of Arabidopsis epidermis, which consists of a few well-characterized cell types. Root epidermis differentiates into hair and non-hair cells, while the aerial epidermis is composed of trichomes and stomata scattered at regular intervals between pavement cells.1,2 A great many transcription factors participate in epidermal cell type specification, including bHLH transcription factors.2-6

bHLH Transcription Factors in Arabidopsis

The bHLH transcription factor superfamily is composed of a large number of proteins found in almost all organisms, including fungi, plants, and animals.7 One of the largest transcription factor families in Arabidopsis, the bHLH family has 147 members.8 As genes from the same subfamily tend to have related functions, a structural analysis of this superfamily was performed; as a result, the bHLH superfamily was divided into 12 subfamilies.9

In Arabidopsis, bHLH members are involved in a broad range of growth and developmental signaling pathways, including light signaling,10-19 brassinosteroid and abscisic acid signaling,20-27 gynoecium development,28,29 abiotic stress responses,30,31 flavonoid biosynthesis,32,33 axillary meristem formation,34 flowering time control,35 trichome and root hair differentiation,36-42 and stomatal patterning.4,43-46 Together, these results indicate that the bHLH superfamily is very important in plant development.

bHLH transcription factors function in root and shoot trichoblast cell fate determination and in morphogenesis

Root hairs and trichomes are outstanding models for studying the molecular basis of cell fate determination in Arabidopsis.47 Root hairs are unbranched tubular outgrowths of the root epidermis that function to collect water and nutrients, including minerals, from the soil47 Trichomes are branched (1–3 branches in wild-type Col-0), single-celled structures on the aerial parts of plants that protect the organism from biotic stress and UV irradiation.2

In Arabidopsis, the first-reported bHLH transcription factors were GLABRA3 (GL3) and ENHANCER OF GLABRA3 (EGL3), which play partially redundant roles in root hair control.41 gl3 egl3 double mutants have hairy roots due to a failure in non-hair cell specification.37,41 mRNA and protein expression of these genes was detected in root hair and non-root hair cells, respectively, indicating that cell fate determination in root epidermis occurs in a non-cell autonomous manner.40 The molecular mechanism of cell fate determination in trichomes is similar to that in root epidermis,2,6,48 including a requirement for GL3 and EGL3.36,39,49 Indeed, gl3-1 mutants show reduced numbers of leaf trichomes and branches,39 although egl3 single mutants have no obvious trichome phenotype.37 gl3 egl3 double mutants have glabrous leaves and inflorescence stems, indicating redundant roles for these genes in trichome specification.37 TT8 is also involved in leaf margin trichome formation.50 Unlike the non-cell autonomous control of root cell development, GL3 and EGL3 appear not to be transportable in leaf tissues.51

bHLH transcription factors, together with R2R3-MYB proteins, including WEREWOLF (WER, for root hair cell fate control) and GLABRA1 (GL1, for trichome differentiation), and the WD-40 factor TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 (TTG1), form a linear activation complex by using the bHLH protein as a linker; WER and TTG1 interact with bHLH members directly in vitro and in vivo, but no direct interaction has been identified between them.6,37,40,41,47,51 The active transcriptional complex R2R3-MYB-bHLH-TTG1 positively regulates the downstream homeobox-leucine zipper gene GLABRA2 (GL2) to promote non-hair cell and trichome differentiation.36,41,48,52-54 Compared with R2R3-MYB proteins, six R3-MYB factors, CAPRICE (CPC), TRIPTYCHON (TRY), TRICHOMELESS1 (TCL1), and ENHANCER OF TRIPTYCHON AND CAPRICE 1, 2, and 3 (ETC1, 2, and 3), possess only the DNA-binding domain without a recognizable activation domain.3,52,55-61 They are activated by the trimeric activation complex, transported to neighboring cells, and integrated competitively into the trimeric complex, rendering it inactive.6,47,52,55,58,62 These steps comprise the generally accepted activator-inhibitor model of root hair and trichome cell fate specification.6,47,63

AtMYC1, another bHLH transcription factor belonging to the same subfamily as GL3 and EGL3 (subfamily IIIf), was first cloned in 1996.64 Until rescently, its role in root hair and trichome control has been largely demonstrated.36,49,65Atmyc1 mutants have reduced numbers of non-hair cells and trichomes.36,49 Genetic analyses have shown partially redundant yet divergent functions between AtMYC1 and GL3/EGL3.36 GL3 and EGL3 can successfully complement the defects observed in Atmyc1; however, AtMYC1 is incapable of recovering the lesions seen in gl3 elg3 double mutants.36

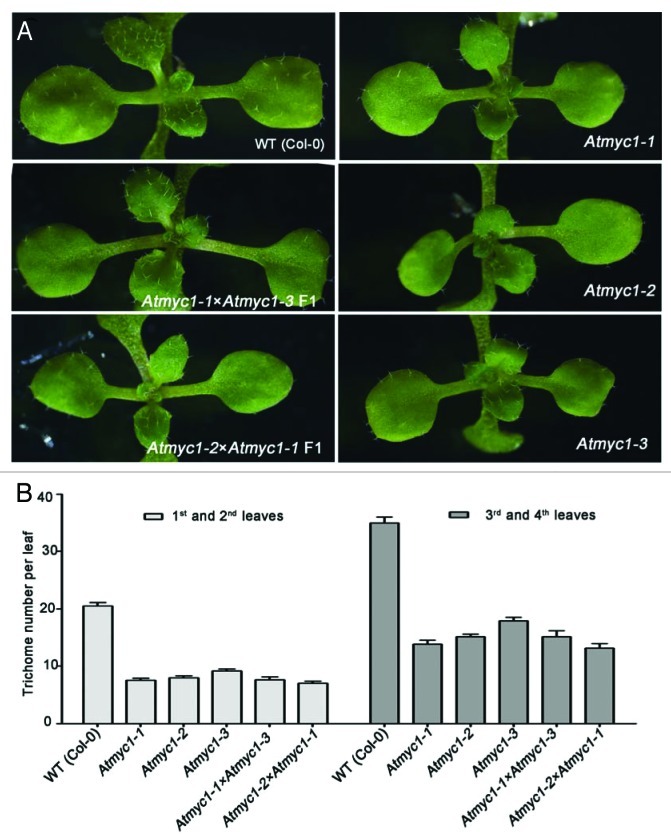

AtMYC1 functions upstream of GL2, through interactions with MYB proteins and TTG1.36,49 Unlike GL3 and EGL3, which function as homodimers or heterodimers,37,39 AtMYC1 tends to work as a monomer.36 Besides its reported protein-interacting domain, the arginine at position 173 (R173) in AtMYC1, which is conserved between AtMYC1 and GL3/EGL3, is crucial for its interaction with partner proteins and for its proper function.36 The importance of this residue was demonstrated in an analysis of Atmyc1–1, which carries a point mutation at this position (R173H). Previously, we confirmed that AtMYC1 was responsible for the phenotype of this mutant by transgenic complementation. We also performed crosses between Atmyc1–1 and Atmyc1–2, and between Atmyc1–1 and Atmyc1–3. The F1 progeny behaved like the parental lines (Fig. 1), indicating that Atmyc1–1 is a new allele of Atmyc1. AtMYC1 mRNA is expressed mainly in root hair cells,36 similar to its homologs, while AtMYC1 expression is limited to the same cell files.65 In addition, like GL3/EGL3, AtMYC1 is negatively regulated by WER and positively regulated by CPC.40,65

Figure 1.Atmyc1–1 is a new allele of Atmyc1. A. Leaf trichomes from 12-d-old seedlings of the indicated genotype. F1 plants produced by crossing Atmyc1–1 with Atmyc1–2, and Atmyc1–1 with Atmyc1–3 are shown. Wild-type and Atmyc1 mutant control plants are also shown. B. Trichome number analysis of the first and second pair of leaves in the F1 and control plants. At least 12 plants were analyzed for each genotype. Error bars represent the standard deviation

Recently, a genome-wide transcriptome analysis followed by a detailed functional analysis demonstrated that the bHLH genes bHLH54, bHLH66, and bHLH82, which belong to subfamilies VIIIc and XI, participate in root epidermal cell development in a stage-specific manner.65 It is reasonable to assume that these bHLH factors also control trichome development.

Taken together, these results demonstrate the extensive participation of bHLH family members in different stages of root and shoot epidermis development. Consequently, bHLH transcription factors belonging to the IIIf, VIIIc, and XI subfamilies, together with a number of other transcription factors, play crucial roles in epidermis trichoblast cell fate determination in Arabidopsis.

bHLH Transcription Factors are Involved in Stomata Development

Stomata are microscopic pores found in land plants that consist of a pair of specialized, epidermis-derived guard cells.4 Stomata play critical roles in gas and water vapor exchange with the atmosphere.4 In Arabidopsis, stomata formation provides an exceptional model for studying cell fate determination.45,66 Stomata are produced through a series of asymmetric cell divisions followed by a single symmetric cell division.67 Detailed analyses have shown that stomata formation occurs in four stages: meristemoid mother cell (MMC), meristemoid, guard mother cell (GMC), and terminally-differentiated guard cells.4 Three closely related bHLH genes, SPEECHLESS (SPCH), MUTE, and FAMA, function consecutively as positive regulators of stomata formation.4,45 Indeed, loss-of-function mutants of these genes do not produce stomata.4 Spatial and temporal expression pattern analyses and mutant phenotype analysis have demonstrated that SPCH is involved in the transition from MMCs to meristemoids, while MUTE guides the transition from meristemoids to GMCs, and FAMA promotes the shift from GMCs to guard cells.43,46,68,69

The frequently discussed bHLH genes GL3 and EGL3 are also involved in stomata development in the hypocotyl; gl3 egl3 double mutants show an increased number of stomata.40 Together, these results suggest that bHLH genes make a significant contribution to the specification of stomata in Arabidopsis.

Conclusions

As one of the largest superfamilies in Arabidopsis, bHLH transcription factors participate in a broad range of growth and developmental signaling pathways.8 However, there are still many bHLH genes whose biological functions are unknown. Thus, more extensive analyses should be performed to identify the biological roles and developmental pathways bHLH transcription factors are involved in. This will enrich our understanding of the bHLH superfamily, and provide new insight into the mechanism of epidermal cell fate determination.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jessica Habashi for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) and Hebei Province key laboratory program (L.M.).

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/22404

References

- 1.Schiefelbein J, Kwak SH, Wieckowski Y, Barron C, Bruex A. The gene regulatory network for root epidermal cell-type pattern formation in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:1515–21. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balkunde R, Pesch M, Hülskamp M. Trichome patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana from genetic to molecular models. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;91:299–321. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)91010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tominaga R, Iwata M, Okada K, Wada T. Functional analysis of the epidermal-specific MYB genes CAPRICE and WEREWOLF in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2264–77. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.045732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pillitteri LJ, Torii KU. Breaking the silence: three bHLH proteins direct cell-fate decisions during stomatal development. Bioessays. 2007;29:861–70. doi: 10.1002/bies.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grebe M. The patterning of epidermal hairs in Arabidopsis--updated. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15:31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tominaga-Wada R, Ishida T, Wada T. New insights into the mechanism of development of Arabidopsis root hairs and trichomes. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2011;286:67–106. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385859-7.00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skinner MK, Rawls A, Wilson-Rawls J, Roalson EH. Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor gene family phylogenetics and nomenclature. Differentiation. 2010;80:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toledo-Ortiz G, Huq E, Quail PH. The Arabidopsis basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1749–70. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heim MA, Jakoby M, Werber M, Martin C, Weisshaar B, Bailey PC. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family in plants: a genome-wide study of protein structure and functional diversity. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:735–47. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leivar P, Tepperman JM, Cohn MM, Monte E, Al-Sady B, Erickson E, et al. Dynamic antagonism between phytochromes and PIF family basic helix-loop-helix factors induces selective reciprocal responses to light and shade in a rapidly responsive transcriptional network in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1398–419. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.095711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castelain M, Le Hir R, Bellini C. The non-DNA-binding bHLH transcription factor PRE3/bHLH135/ATBS1/TMO7 is involved in the regulation of light signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Physiol Plant. 2012;145:450–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh E, Yamaguchi S, Hu J, Yusuke J, Jung B, Paik I, et al. PIL5, a phytochrome-interacting bHLH protein, regulates gibberellin responsiveness by binding directly to the GAI and RGA promoters in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1192–208. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh E, Kim J, Park E, Kim JI, Kang C, Choi G. PIL5, a phytochrome-interacting basic helix-loop-helix protein, is a key negative regulator of seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2004;16:3045–58. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimori T, Yamashino T, Kato T, Mizuno T. Circadian-controlled basic/helix-loop-helix factor, PIL6, implicated in light-signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:1078–86. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang KY, Kim YM, Lee S, Song PS, Soh MS. Overexpression of a mutant basic helix-loop-helix protein HFR1, HFR1-deltaN105, activates a branch pathway of light signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1630–42. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.029751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamashino T, Matsushika A, Fujimori T, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, et al. A Link between circadian-controlled bHLH factors and the APRR1/TOC1 quintet in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:619–29. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huq E, Quail PH. PIF4, a phytochrome-interacting bHLH factor, functions as a negative regulator of phytochrome B signaling in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2002;21:2441–50. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.10.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soh MS, Kim YM, Han SJ, Song PS. REP1, a basic helix-loop-helix protein, is required for a branch pathway of phytochrome A signaling in arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2061–74. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halliday KJ, Hudson M, Ni M, Qin M, Quail PH. poc1: an Arabidopsis mutant perturbed in phytochrome signaling because of a T DNA insertion in the promoter of PIF3, a gene encoding a phytochrome-interacting bHLH protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5832–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang LY, Bai MY, Wu J, Zhu JY, Wang H, Zhang Z, et al. Antagonistic HLH/bHLH transcription factors mediate brassinosteroid regulation of cell elongation and plant development in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3767–80. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Zhu Y, Fujioka S, Asami T, Li J, Li J. Regulation of Arabidopsis brassinosteroid signaling by atypical basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3781–91. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuppusamy KT, Chen AY, Nemhauser JL. Steroids are required for epidermal cell fate establishment in Arabidopsis roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8073–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811633106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandler JW, Cole M, Flier A, Werr W. BIM1, a bHLH protein involved in brassinosteroid signalling, controls Arabidopsis embryonic patterning via interaction with DORNROSCHEN and DORNROSCHEN-LIKE. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;69:57–68. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9405-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H, Sun J, Xu Y, Jiang H, Wu X, Li C. The bHLH-type transcription factor AtAIB positively regulates ABA response in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;65:655–65. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J, Kim HY. Molecular characterization of a bHLH transcription factor involved in Arabidopsis abscisic acid-mediated response. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006; 1759:191-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Yadav V, Mallappa C, Gangappa SN, Bhatia S, Chattopadhyay S. A basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor in Arabidopsis, MYC2, acts as a repressor of blue light-mediated photomorphogenic growth. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1953–66. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.032060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abe H, Urao T, Ito T, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 2003;15:63–78. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajani S, Sundaresan V. The Arabidopsis myc/bHLH gene ALCATRAZ enables cell separation in fruit dehiscence. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1914–22. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heisler MG, Atkinson A, Bylstra YH, Walsh R, Smyth DR. SPATULA, a gene that controls development of carpel margin tissues in Arabidopsis, encodes a bHLH protein. Development. 2001;128:1089–98. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li F, Guo S, Zhao Y, Chen D, Chong K, Xu Y. Overexpression of a homopeptide repeat-containing bHLH protein gene (OrbHLH001) from Dongxiang Wild Rice confers freezing and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2010;29:977–86. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0883-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou J, Li F, Wang JL, Ma Y, Chong K, Xu YY. Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor from wild rice (OrbHLH2) improves tolerance to salt- and osmotic stress in Arabidopsis. J Plant Physiol. 2009;166:1296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baudry A, Caboche M, Lepiniec L. TT8 controls its own expression in a feedback regulation involving TTG1 and homologous MYB and bHLH factors, allowing a strong and cell-specific accumulation of flavonoids in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2006;46:768–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nesi N, Debeaujon I, Jond C, Pelletier G, Caboche M, Lepiniec L. The TT8 gene encodes a basic helix-loop-helix domain protein required for expression of DFR and BAN genes in Arabidopsis siliques. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1863–78. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang F, Wang Q, Schmitz G, Müller D, Theres K. The bHLH protein ROX acts in concert with RAX1 and LAS to modulate axillary meristem formation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012;71:61–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito S, Song YH, Josephson-Day AR, Miller RJ, Breton G, Olmstead RG, et al. FLOWERING BHLH transcriptional activators control expression of the photoperiodic flowering regulator CONSTANS in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3582–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118876109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao H, Wang X, Zhu D, Cui S, Li X, Cao Y, et al. A single amino acid substitution in IIIf subfamily of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor AtMYC1 leads to trichome and root hair patterning defects by abolishing its interaction with partner proteins in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:14109–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang F, Gonzalez A, Zhao M, Payne CT, Lloyd A. A network of redundant bHLH proteins functions in all TTG1-dependent pathways of Arabidopsis. Development. 2003;130:4859–69. doi: 10.1242/dev.00681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esch JJ, Chen M, Sanders M, Hillestad M, Ndkium S, Idelkope B, et al. A contradictory GLABRA3 allele helps define gene interactions controlling trichome development in Arabidopsis. Development. 2003;130:5885–94. doi: 10.1242/dev.00812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payne CT, Zhang F, Lloyd AM. GL3 encodes a bHLH protein that regulates trichome development in arabidopsis through interaction with GL1 and TTG1. Genetics. 2000;156:1349–62. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.3.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernhardt C, Zhao M, Gonzalez A, Lloyd A, Schiefelbein J. The bHLH genes GL3 and EGL3 participate in an intercellular regulatory circuit that controls cell patterning in the Arabidopsis root epidermis. Development. 2005;132:291–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.01565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernhardt C, Lee MM, Gonzalez A, Zhang F, Lloyd A, Schiefelbein J. The bHLH genes GLABRA3 (GL3) and ENHANCER OF GLABRA3 (EGL3) specify epidermal cell fate in the Arabidopsis root. Development. 2003;130:6431–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.00880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masucci JD, Schiefelbein JW. The rhd6 mutation of Arabidopsis thaliana alters root-hair initiation through an auxin- and ethylene-associated process. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1335–46. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pillitteri LJ, Bogenschutz NL, Torii KU. The bHLH protein, MUTE, controls differentiation of stomata and the hydathode pore in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:934–43. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanaoka MM, Pillitteri LJ, Fujii H, Yoshida Y, Bogenschutz NL, Takabayashi J, et al. SCREAM/ICE1 and SCREAM2 specify three cell-state transitional steps leading to arabidopsis stomatal differentiation. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1775–85. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torii KU, Kanaoka MM, Pillitteri LJ, Bogenschutz NL. Stomatal development: three steps for cell-type differentiation. Plant Signal Behav. 2007;2:311–3. doi: 10.4161/psb.2.4.4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacAlister CA, Ohashi-Ito K, Bergmann DC. Transcription factor control of asymmetric cell divisions that establish the stomatal lineage. Nature. 2007;445:537–40. doi: 10.1038/nature05491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishida T, Kurata T, Okada K, Wada T. A genetic regulatory network in the development of trichomes and root hairs. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:365–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schiefelbein J. Cell-fate specification in the epidermis: a common patterning mechanism in the root and shoot. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:74–8. doi: 10.1016/S136952660200002X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Symonds VV, Hatlestad G, Lloyd AM. Natural allelic variation defines a role for ATMYC1: trichome cell fate determination. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maes L, Inzé D, Goossens A. Functional specialization of the TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 network allows differential hormonal control of laminal and marginal trichome initiation in Arabidopsis rosette leaves. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1453–64. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.125385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao M, Morohashi K, Hatlestad G, Grotewold E, Lloyd A. The TTG1-bHLH-MYB complex controls trichome cell fate and patterning through direct targeting of regulatory loci. Development. 2008;135:1991–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.016873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song SK, Ryu KH, Kang YH, Song JH, Cho YH, Yoo SD, et al. Cell fate in the Arabidopsis root epidermis is determined by competition between WEREWOLF and CAPRICE. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:1196–208. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.185785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morohashi K, Zhao M, Yang M, Read B, Lloyd A, Lamb R, et al. Participation of the Arabidopsis bHLH factor GL3 in trichome initiation regulatory events. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:736–46. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.104521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masucci JD, Schiefelbein JW. Hormones act downstream of TTG and GL2 to promote root hair outgrowth during epidermis development in the Arabidopsis root. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1505–17. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.9.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simon M, Lee MM, Lin Y, Gish L, Schiefelbein J. Distinct and overlapping roles of single-repeat MYB genes in root epidermal patterning. Dev Biol. 2007;311:566–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tominaga R, Iwata M, Sano R, Inoue K, Okada K, Wada T. Arabidopsis CAPRICE-LIKE MYB 3 (CPL3) controls endoreduplication and flowering development in addition to trichome and root hair formation. Development. 2008;135:1335–45. doi: 10.1242/dev.017947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Serna L. CAPRICE positively regulates stomatal formation in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl. Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3:1077–82. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.12.6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koshino-Kimura Y, Wada T, Tachibana T, Tsugeki R, Ishiguro S, Okada K. Regulation of CAPRICE transcription by MYB proteins for root epidermis differentiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:817–26. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kirik V, Simon M, Huelskamp M, Schiefelbein J. The ENHANCER OF TRY AND CPC1 gene acts redundantly with TRIPTYCHON and CAPRICE in trichome and root hair cell patterning in Arabidopsis. Dev Biol. 2004;268:506–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wada T, Kurata T, Tominaga R, Koshino-Kimura Y, Tachibana T, Goto K, et al. Role of a positive regulator of root hair development, CAPRICE, in Arabidopsis root epidermal cell differentiation. Development. 2002;129:5409–19. doi: 10.1242/dev.00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wada T, Tachibana T, Shimura Y, Okada K. Epidermal cell differentiation in Arabidopsis determined by a Myb homolog, CPC. Science. 1997;277:1113–6. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kurata T, Ishida T, Kawabata-Awai C, Noguchi M, Hattori S, Sano R, et al. Cell-to-cell movement of the CAPRICE protein in Arabidopsis root epidermal cell differentiation. Development. 2005;132:5387–98. doi: 10.1242/dev.02139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schellmann S, Hülskamp M, Uhrig J. Epidermal pattern formation in the root and shoot of Arabidopsis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:146–8. doi: 10.1042/BST0350146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Urao T, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Mitsukawa N, Shibata D, Shinozaki K. Molecular cloning and characterization of a gene that encodes a MYC-related protein in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:571–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00019112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bruex A, Kainkaryam RM, Wieckowski Y, Kang YH, Bernhardt C, Xia Y, et al. A gene regulatory network for root epidermis cell differentiation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Serna L. bHLH proteins know when to make a stoma. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:483–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Geisler M, Nadeau J, Sack FD. Oriented asymmetric divisions that generate the stomatal spacing pattern in arabidopsis are disrupted by the too many mouths mutation. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2075–86. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ohashi-Ito K, Bergmann DC. Arabidopsis FAMA controls the final proliferation/differentiation switch during stomatal development. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2493–505. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pillitteri LJ, Sloan DB, Bogenschutz NL, Torii KU. Termination of asymmetric cell division and differentiation of stomata. Nature. 2007;445:501–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]