Abstract

Underlying molecular genetic mechanisms of diseases can be deciphered with unbiased strategies using recently developed technologies enabling genome-wide scale investigations. These technologies have been applied in scanning for genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic changes for oral and craniofacial diseases. However, these approaches as applied to oral and craniofacial conditions are in the initial stages, and challenges remain to be overcome, including analysis of high throughput data and their interpretation. Here, we review methodology and studies using genome-wide approaches in oral and craniofacial diseases and suggest future directions.

Keywords: genome-wide, genomics, craniofacial, microarray

Introduction

Although almost a decade has passed since the completion of the human genome project, we are still far from fully understanding the role of genetics in disease. The proposed number of protein-coding genes in humans is approximately 20 000, dramatically reduced from the original estimate. There is limited knowledge about noncoding genes, such as microRNAs and less knowledge about the majority of the human genome – the intergenic regions. Thus, investigations of candidate gene regions are limited by incomplete knowledge. Advantages and disadvantages of genome-wide approaches (GWA) in oral, and craniofacial diseases are the same as in other disorders. Although briefly summarized here, details of general genome technologies and personalized dental medicine were reviewed in a previous issue (Eng et al, 2012).

Oral and craniofacial diseases share many important features with other disorders as targets for GWA. But they also have unique aspects. Because it is very difficult to access directly related tissue samples in many other diseases, peripheral blood has been suggested as a surrogate tissue. However, compared with other areas, the oral cavity is easily accessible, facilitating sample collection. Collecting samples from the oral cavity is often preferable, depending on the question and the condition. Furthermore, sampling is relatively safe, does not cause esthetic problems after tissue removal, and can be minimally invasive; buccal swabs or saliva can efficiently yield enough DNA and RNA for downstream genome-wide analyses. Another feature of the oral cavity is the presence of its resident microflora, where direct sampling can be analyzed as part of a microbiome investigation. Microbiome research sequences genomes of the microfloral organisms instead of the human genome, and these two approaches can be efficiently combined to ascertain the relationship between the host and its microbiome.

In most circumstances, the genome of an individual’s cells is the same regardless of cell type; the genome of the fibroblast is identical with the genome of the osteoblast. However, the morphology and behavior of fibroblasts is very different from osteoblasts because of difference in gene expression profile. It is estimated that more than 200 cell types exist histologically in humans and they have different gene expression profiles. One of the underlying mechanisms of this control is called ‘epigenetics,’ and is mainly based on DNA methylation and histone modification (Ballestar, 2011; Cedar and Bergman, 2011). Therefore, investigation of gene expression profiles as well as epigenetics of oral and craniofacial diseases can be carefully designed using appropriate cell types. For example, gene expression profiles from peripheral blood cells may be appropriate for leukemia research, but not ideal for salivary gland diseases. Even from the same cell population, epigenetics and gene expression profiles can be different depending on the time (or stage) of disease when the sample is collected. Investigation of DNA sequence variation may not be as critically dependent on cell types as gene expression or epigenetic changes. However, some types of diseases such as cancer are likely because of mutation-inducing change of DNA sequence in a subpopulation of cells, making DNA sequence data specific to the transformed cell type.

Tools for GWA

Two main strategies used in GWA are microarray type scanning and next generation sequencing. Microarray is the first strategy that enabled investigations on a genome-wide scale. Originally developed to compare gene expression profiles between test tissue and controls across the entire genome, application of microarray technology has been expanded with the information from the Human Genome Project allowing investigators to design probes for known transcripts, sequence variations, copy number variations, and epigenetic changes. Millions of probes detecting sequence variations or level of transcript expression can be spotted onto one array. Because the probes are designed based on commonly found sequence variation or transcripts, arrays cannot detect unknown mutations, splicing variants, or micro RNAs. Therefore, the array-type scanner is appropriate for detecting association with oral and craniofacial disease following the common variant/common disease theory.

Next generation sequencing is a newer approach to investigate oral and craniofacial diseases on a genome-wide level. The main difference between next generation sequencing and traditional sequencing is high throughput data generation based on overlapping short reads, which are randomly amplified across the entire genomic material. One run of the next generation sequencer can yield enough nucleotide readings to sequence the entire human genome accurately. Because this platform can be used to sequence targeted genomic regions or selected DNA libraries, it can replace almost all microarray techniques. Unlike a microarray type scanner, predetermined probes are not necessary in next generation sequencing, and the absolute number of transcripts can be measured. Compared with the next generation sequencing, microarray is no longer considered as unbiased, because microarray requires predesigned probes based on known bioinformatics. Therefore, next generation sequencing is appropriate for detecting association with diseases following the mutation selection theory. One of the sequencers recently introduced, the Ion Proton (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA), is claimed to be capable of sequencing the entire human genome for <$1000. This exponential decrease in sequencing costs over time will enable whole genome sequencing as a standard diagnostic procedure in the near future.

Both of these GWA tools can yield high throughput data with relatively small size arrays and small amounts of sample within a short period of laboratory time. To make this possible, complex laboratory procedures have been developed and applied. Therefore, the accuracy of genomic details has been challenged by many factors, including batch effect, inter-experimenter reliability, sensitivity of equipment, and analyzing software. The importance of validation of the genome-wide data generated by one platform with a different type of platform cannot be overemphasized. From the genome-wide data, the significant findings need to be validated with platforms targeting small number of candidates. For example, gene expression microarray findings require real time quantitative PCR validation and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array findings need individual SNP genotyping validation.

Genome-wide studies in oral diseases: DNA and RNA

To examine application of these methods, we searched articles in PubMed through February 2012 with filtration by the species as ‘human,’ the language as ‘English’ and publication date with ‘in 3 years.’ Box 1 shows the searched terms. The articles from the four search terms along with additional articles from other sources are reviewed for GWA using DNA and RNA of humans and of oral microflora.

Box 1. Searched terms for GWA in oral diseases.

genome-wide[All Fields] AND (‘mouth diseases’[MeSH Terms] OR (‘mouth’[All Fields] AND ‘diseases’[All Fields]) OR ‘mouth diseases’[All Fields] OR (‘oral’[All Fields] AND ‘disease’[All Fields]) OR ‘oral disease’[All Fields]) resulted 89 articles,

‘epigenomics’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘epigenomics’[All Fields] OR ‘epigenetic’[All Fields]) AND (‘mouth diseases’[MeSH Terms] OR (‘mouth’[All Fields] AND ‘diseases’[All Fields]) OR ‘mouth diseases’[All Fields] OR (‘oral’[All Fields] AND ‘disease’[All Fields]) OR ‘oral disease’[All Fields]) resulted 59 articles,

microarray[All Fields] AND (‘mouth diseases’ [MeSH Terms] OR (‘mouth’[All Fields] AND ‘diseases’[All Fields]) OR ‘mouth diseases’[All Fields] OR (‘oral’[All Fields] AND ‘disease’[All Fields]) OR ‘oral disease’[All Fields]) ended up 139 articles,

((‘metagenome’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘metagenome’[All Fields] OR ‘microbiome’[All Fields]) AND (‘mouth diseases’[MeSH Terms] OR (‘mouth’[All Fields] AND ‘diseases’[All Fields]) OR ‘mouth diseases’[All Fields] OR (‘oral’[All Fields] AND ‘disease’[All Fields]) OR ‘oral disease’[All Fields])) AND (‘humans’[MeSH Terms] AND English[lang] AND ‘2009/01/29’[PDat] : ‘2012/01/28’[PDat]) resulted 47 articles.

GWA using DNA: sequence variations

For genome-wide association studies, probes are designed for millions of preselected DNA sequence variations and arrayed on a small surface. After hybridization of samples, fluorescence on the hybridized probes is scanned to generate genotype calls. To maximize the efficacy of association detection with phenotypes, selection of sequence variations is mostly limited to SNPs, although non-polymorphic sequences are also included for copy number variations.

Examples

Dental caries is one of the most common oral diseases, affecting more than 80% of the world’s population. Twin studies estimate that the genetic contribution to dental caries ranges from 35% to 67% (Conry et al, 1993; Bretz et al, 2005; Bretz and Rosa, 2011). However, external factors such as fluoride consumption, dental hygiene, and type of diet may overcome genetic contributions. Therefore, studies investigating responsible loci for dental caries have rarely been performed across the entire genome. One recently published genome-wide association study was based on 580 000 SNPs with the Illumina platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) (Shaffer et al, 2011). However, candidate loci found in this study could neither be sustained after multiple test correction nor replicated with a different cohort, suggesting that dental caries is a complex trait involving multiple genetic components of subtle effects.

While dental caries is the main cause of tooth loss in the young, periodontitis is the major cause of tooth loss in adults of 40 years and older. Even though alternative methods such as DNA pooling with microsatellite genotyping suggest candidate regions for periodontitis (Tabeta et al, 2009), the decreased cost of SNP arrays allows direct and dense mapping across the entire genome. Recently, a genome-wide association study identified a locus including a SNP in the GLT6D1 encoding gene for aggressive periodontitis that was replicated in another cohort (Schaefer et al, 2010). This SNP, rs1537415, is located in intron of GLT6D1 and its potential reduction in GATA-3 binding affinity is suggested as the underlying mechanism of aggressive periodontitis. Although this finding was replicated and supported by functional analysis, it is still not clear whether this locus is responsible for general periodontitis as well as generalizable across ethnic groups. Another region on chromosome 9 was associated with aggressive periodontitis, and candidate SNPs are in the 9p21.3 region (Schaefer et al, 2009). These associations of rs2891168, rs1333042, and rs496892 were replicated with an independent cohort (Ernst et al, 2011), although they are not based on GWA.

One of the most investigated oral and craniofacial diseases for genetic contribution is cleft lip with and without cleft palate. Because of the number of publications, we limit this review to the isolated non-syndromic cleft lip with and without cleft palate. It is strongly suggested by twin and family studies that genes play a major role in this oral and craniofacial disease (Mitchell, 2002; Grosen et al, 2010). A genome-wide linkage analysis of a Japanese family with six members across three successive generations suggested two loci of p arms of chromosome 2 as the candidate regions for cleft soft palate (Tsuda et al, 2010). As the highest prevalence in Asians and lowest prevalence in Africans persists after immigration, it is likely mediated by genetics than by environmental factors (Murray, 2002). GWA for cleft lip with and without cleft palate have found associated loci in small number of genes, while most of findings are in intergenic or introns (Yuan et al, 2011). A recent genome-wide association study identified strong association with a SNP, rs987525 in the 8q24 chromosomal region with replications (Birnbaum et al, 2009; Grant et al, 2009; Beaty et al, 2010; Blanton et al, 2010). However, this association was not replicated in East African populations, supporting locus heterogeneity of cleft lip with and without cleft palate (Weatherley-White et al, 2011). Also, this 8q24 region relatively lacks protein-coding genes, suggesting that causative genes or regulatory elements are yet to be found in 8q24 or they are in the linkage disequilibrium with this region. Others (Yuan et al, 2011) report multiple loci. While novel association with SNPs near MAFB and ABCA4 is reported (Beaty et al, 2010), it has also been suggested that gene-environment interactions may explain differences among ethnic groups. For example, multiple SNPs in TBK1 and ZNF236 only show association in the presence of maternal smoking, while SNPs in BAALC decreased risk of cleft lip with and without cleft palate in the presence of multivitamin supplementation (Beaty et al, 2011). These findings emphasize the importance of gene-environment interactions in the search for responsible genetic variations of complex and heterogeneous oral and craniofacial disorders.

Cancers are the result of a series of genetic mutations in somatic cells. Because of genomic instability of cancer cells, oral cancers contain large populations of cells carrying a great variety of mutations. Thus, comparison of DNA sequences between tumor cells and normal cells is not practical to find genetic variations responsible for cancer. It was reported that the cancer genome has more than 3.8 million sequence variations compared with the standard human genome based on sequencing data (Ley et al, 2008). Overlap of mutations is limited, even among the same type of tumors. Therefore, particularly in cancer genetic research, the field is moving from a specific gene focus toward GWA from several large collaborative projects (described later). It is difficult to differentiate mutations causing carcinogenesis from mutations of incidental consequence during the uncontrolled cell division and genomic instability of cancer cells. Instead of SNPs, copy number variations (Vekony et al, 2009; Kim et al, 2010) are being investigated to find association between oral cancer and genetic variations. A microarray platform providing comparative genomic hybridization revealed that chromosomal gain of 11q22.1-q22.2 and loss of 11q23-q25 are associated with poor outcomes in oral cancer patients (Ambatipudi et al, 2011). GWA for oral cancers are mostly based on epigenetic changes and gene expression profiles, which are discussed later in this review.

Chronic inflammatory systemic diseases such as lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and Behçet’s disease are complex diseases with heterogeneous manifestations, often including oral symptoms. Candidate gene association studies following genome-wide association studies of systemic lupus erythematosus found new loci, as well as replicated some previous findings (Gateva et al, 2009; He et al, 2010; Taylor et al, 2011). No genome-wide association study has yet been performed for Sjögren’s syndrome. However, a genome-wide association study of Stevens-Johnson syndrome followed by a functional analysis demonstrated significant associations with agonist-activated prostaglandin E receptor 3 genetic variations (Ueta et al, 2010). For Behçet’s disease, two genome-wide association studies revealed significant associations with multiple SNPs in loci 1p31.3 and 1q32.1 associated with IL10 and IL23R-IL 12RB2 loci (Mizuki et al, 2010; Remmers et al, 2010). A genome-wide association study using microsatellites suggested involvement of a locus of the major histocompatibility complex in 6p21.3 in Asian populations (Meguro et al, 2010). These studies demonstrate that common variations in genes of the immune system are important in risk of chronic inflammatory systemic diseases. However, each of the identified alleles account for only a small fraction of the overall genetic risk.

Genome-wide association studies of oral and craniofacial conditions characterized by painful symptoms such as trigeminal neuralgia or temporomandibular joint disorders have not yet been published. Currently, a study related to acute inflammatory pain induced by surgical removal of third molars is the only genome-wide association study of facial pain (Kim et al, 2009).

GWA using DNA: epigenetic changes

Epigenetics refers to functionally relevant modification of the genome that causes enduring and heritable changes in gene expression without a change in DNA sequence. DNA methylation is the most investigated of epigenetic changes and induces gene silencing. Bisulfite treatment on single strand DNA or using chromatin immunoprecipitation with protein containing the methyl-CpG-binding domain followed by microarray scanning or sequencing can give a genome-wide view of the DNA methylation pattern. Another major form of an epigenetic mechanism is DNA-associated histone protein modification, implying that particular combinations of histone modification control activity of the DNA contained therein. Histone acetylation is known to increase gene expression; however, this is overly simplistic, because no single histone modification is predictive for DNA activity.

Studies of epigenetic mechanisms for dental caries have rarely been performed. For the periodontal diseases, however, a few targeted epigenetic studies reveal that methylation of CpG islands in E-Cadherin and COX-2 genes occurs more frequently (Loo et al, 2010; Zhang et al, 2010b), while methylation of promoter regions of interferon gamma occurs less (Zhang et al, 2010c) in gingival tissues of chronic periodontitis patients. These findings may suggest relevance of inflammatory pathways in which the expression of cytokines is unbalanced. However, genome-wide epigenetic studies for periodontal diseases have not been published.

Even with active investigation of genetic association in non-syndromic cleft lip with and without cleft palate, direct evidence in candidate regions as well as genome-wide level of epigenetic controls is not yet reported. However, for some candidate genes related to nonsyndromic cleft lip with and without cleft palate, certain alleles show increased risk only when inherited from the father but not from mother, or vice versa (Rubini et al, 2005; Reutter et al, 2008; Sull et al, 2008, 2009; Park et al, 2009; Suazo et al, 2010). These results suggest maternal and paternal parent-of-origin effects in this disorder, which may indicate epigenetic control by imprinting. Imprinting is one of the best known heritable epigenetic changes. Certain genes are somehow imprinted based on their parental origin. Only one allele, for example, of a paternally inherited allele at certain genes is expressed while a maternally inherited allele is silenced. Therefore, only the paternally inherited allele is responsible for diseases related to those certain genes.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation using antibodies followed by microarray scanning (ChIP-chip) or sequencing across the entire genome (ChIP-seq) allows comparison of epigenetic patterns in cancer cells with the patterns in corresponding normal cells. Generally, widespread hypomethylation is a typical characteristic of most cancer cells. Superimposed on the general hypomethylation is hypermethylation of specific genes, such as tumor suppressor genes. In adenoid cystic carcinoma, genes related to developmental and apoptotic pathways show hypermethylation, suggesting down-regulation of increased risk of cancer (Bell et al, 2011). Hypermethylation in genomic regions related to the tumor suppressor genes such as MGMT, p16INK4a, DAP kinase, p14, p15 has been reported with their association with oral cancers (Kaur et al, 2010; Kordi-Tamandani et al, 2010; Diez-Perez et al, 2011). However, these studies did not use a GWA and do not predict the development of oral cancers. There is insufficient evidence to determine whether the hypermethylation can be used as a biomarker for oral cancer prediction.

Epigenetic studies with GWA in chronic inflammatory disease have rarely been performed. Hypermethylation of BP230 (Gonzalez et al, 2011) and hypomethylation of CD70 (Yin et al, 2010) have been suggested for Sjögren’s syndrome, but this is based on candidate gene approaches.

GWA using RNA: protein-coding genes and microRNA

It is not a simple task to investigate the gene expression profile across the whole genome, although the latest technologies enable counting absolute number of transcripts with next generation sequencers. This may be in part due to the fact that, even from the same individual, gene expression profiles are different between cell types. The gene expression profile of peripheral blood cells is not as closely related to periodontitis as the profile of cells from gingival tissue. Sometimes relevant cells may not be easily accessible, such as brain cells for psychological phenotypes. Normal physiological processes such as aging can also change gene expression profiles of various types of cells.

Another challenge for gene expression profiling is splicing variants. Complicated dynamics of the human genome produce multiple variants of transcripts from one protein-coding gene, based on different splicing combinations of exons and introns. Therefore, using one probe across one protein-coding gene does not provide sufficient information of its multi-dimensional transcriptional activity. Multi-probe approach is an example of improving the detection method of multi-dimensional transcriptional activity.

It is believed that some part of the human genome is transcribed into small pieces of RNA, without further processing to protein translation. One of these noncoding RNA classes is microRNA. These range from 12 to 20 nucleotides in length and function as inhibitors of mRNA with the complementary sequence. When miRNA attaches to the complementary mRNA in making the double stranded RNA molecule, it induces degradation of mRNA. Currently about a thousand miRNA have been reported, and their database (http://www.microrna.org) is constantly updated. It is also believed that other types of non-coding RNA function as control elements for gene expression.

Gene expression profiles of relevant cell populations can be the first line of biologic data responsible for the phenotype. Gene expression profiles of buccal mucosal cells are significantly changed after environmental changes such as smoking (Kupfer et al, 2010). Current classification of cancers based on the traditional system of using clinical classifications such as ‘tumor-nodes metastasis’ could be replaced by patterns of gene expression profile in the future following further research and validation. Based on gene expression profiles, prognosis such as survival of the patient may be predicted, regardless of the treatment. It may also be possible to predict specific drug responses and modify treatment or use a non-cancer-related drug to modify gene expression profiles that will better respond to available cancer drugs to enhance treatment efficacy.

Microarray gene expression studies for dental caries are rare, probably because of the difficulty of collecting RNA from the hard tooth structure. Periapically, granulomas exhibited higher enzymatic activity for matrix metalloproteinases compared with periapical cysts and healthy periodontal ligament (de Paula-Silva et al, 2009). When experimental gingivitis was induced in humans and more than 55 000 probe sets were tested sequentially for a 3-week induction phase and 2-week resolution phase, gene expression changes peaked at the final stage of gingivitis induction and initial stage of resolution in the pathways of leukocyte transmission, cell adhesion, and antigen processing/presentation (Jonsson et al, 2011). When gene expression profiles of periodontitis tissues were compared, genes related to the stimulation of leukocyte transendothelial migration and for impairment of cell-to-cell communication showed differences from normal healthy gingival tissues (Abe et al, 2011). In tissue from drug-induced gingival overgrowth, genes related to collagen metabolism were differentially expressed compared with non-overgrowth tissue, although there were significant individual variations (Shimizu et al, 2011). MicroRNA microarray analyses followed by a real time PCR validation showed that six miRNA genes in gingival tissue were increased eightfold or greater in periodontitis gingivae (Lee et al, 2011). Similar studies in a different cohort yielded five miRNA genes up-regulated fivefold or greater, although they were different miRNA genes (Xie et al, 2011).

Genome-wide approaches have been frequently applied in oral cancer research. From precancerous lesions of oral leukoplakia, 16 genes were suggested as a biomarker gene set of oral epithelial dysplasia (Kuribayashi et al, 2009). Using in vitro cell lines, carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 was identified to contribute to cancer progression and result in poor prognosis (Shinozuka et al, 2009). Gene expression profiles from different types of oral cancers (Jung et al, 2010; Lunde et al, 2010; Rao et al, 2010; Solomon et al, 2010; Zhang et al, 2010a; Kim et al, 2011; Michael et al, 2011; Shao et al, 2011; Song et al, 2011) as well as from different phenotypes of the same cancers (e.g., invasiveness, response to treatment, or prognosis) have been investigated (Waseem et al, 2010; Yamazaki et al, 2010; Kang et al, 2011; Mougeot et al, 2011), as well as in different tissues (e.g., biopsy, peripheral blood). Multiple miRNAs have been reported in association with squamous cell carcinoma (Li et al, 2009; Yu et al, 2010; Scapoli et al, 2011) and adenoma (Zhang et al, 2009). The challenge is to find useful gene expression profiles; patterns of up-regulation or down-regulation of a limited number of genes from this data matrix, to decipher the underlying mechanism of oral cancers and for prognosis and prediction of responses to treatments. To determine the gene expression profiles and obtain a comprehensive description of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic changes in cancers, several large collaborative projects such as the Cancer Genomic Anatomy Project (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/) and the International Cancer Genome Consortium (http://www.icgc.org) are generating genome- wide data on a huge scale. In addition to the direct relationship of gene expression profiles of cancer cells, the value of saliva as a biomarker for oral cancers has been suggested because saliva contains proteins, mRNAs, DNAs, and other molecules that may be associated with oral cancers (Arellano et al, 2009).

In animal models of Sjögren syndrome, gene expression profiles identified 480 genes as being differentially expressed during the development of Sjögren syndrome (Nguyen et al, 2009). In independent patient cohorts, a prominent pattern of up-regulated genes inducible by interferons in saliva and peripheral blood samples suggest innate and adaptive systemic immune responses play a role in the pathogenesis of Sjögren syndrome (Emamian et al, 2009; Hu et al, 2010; Kimoto et al, 2011). The expression pattern of miRNA profiles of minor salivary glands from Sjögren syndrome patients could also accurately distinguish those from controls and suggest that the targets of miRNA may have a protective effect on epithelial cells (Alevizos et al, 2011). A distinctive miRNA signature in Sjögren patients was reported in glandular inflammation and dysfunction (Kapsogeorgou et al, 2011). Global gene expression array of oral lichen planus showed significant differences of genes, especially involved in signal transduction, regulation of transcription, cell adhesion, cell proliferation, immune response, inflammation apoptosis, and angiogenesis (Tao et al, 2009). Another genome-wide gene expression study found upregulation of genes activated by hypoxia such as RTP801 and vascular endothelial growth factor, suggesting that the oral mucosa of lichen planus is in a hypoxic state (Ding et al, 2010). Toll-like receptor family mediated immunity was also reported in association with oral lichen planus (Ohno et al, 2011).

GWA using non-host genomic material, microbiome

The microflora is a distinctive feature of the oral cavity. The recently launched Human Microbiome Project is characterizing the microorganisms living in and on the human body. The oral microbiome is comprised of over 600 prevalent taxa at the species level with distinct subsets predominating at each location (Costello et al, 2009; Nasidze et al, 2009; Dewhirst et al, 2010; Lemon et al, 2010; Charlson et al, 2011). The microbiome of the oral cavity changes the environment for humans as well as is changed by the environment (alcohol, smoking, and oral hygiene) (Shchipkova et al, 2010; Lima et al, 2011). Therefore, the oral microbiome is potentially related to oral health. Targeted sequencing 16S rRNA gene survey of V3-V5 regions (450 bp) or DNA microarray can identify oral microbiome profiles (Ahn et al, 2011; Nossa et al, 2011). Profiling of the normal microbiome of intraoral locations (tooth surface, gingival sulcus, surface of tongue, cheeks, palate, etc) compared with that of disease is likely to shed new light for the investigation of oral and craniofacial diseases.

With pyrosequencing and microarray, Porphyromonous catoniae and Neisseria flavescens were significantly associated with caries-free status of children (Crielaard et al, 2011). The genera of Streptococcus, Veillonella, Actinomyces, Granulicatella, Leptotrichia, and Thiomonas in plaques were significantly associated with dental caries (Ling et al, 2010). Microorganisms on the surface of prosthodontic or orthodontic appliances are other contributors, as the colonization of pathogenic bacteria can be a factor for the instability of intraoral appliances, including implants (Apel et al, 2009).

Molecular methods based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing have shown that the periodontal microbiome is far more diverse than previously thought (Wade, 2011). Patients with refractory periodontitis presented a distinct microbial profile compared with patients characterized as ‘good responders’ and healthy controls (Colombo et al, 2009). Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced miRNA can modulate host signaling responses to cause periodontal diseases (Moffatt and Lamont, 2011). The role of a product of periodontopathic bacteria, butyric acid, has been suggested as a risk factor for several systemic diseases. Butyric acid produced by P. gingivalis may promote gene expression of pathogenic microorganisms such as HIV-1 by inhibition of histone deacetylase and affect on the progress of AIDS (Imai and Ochiai, 2011).

Conclusions and future directions

As reviewed here, GWA are very powerful tools to investigate oral and craniofacial diseases at the molecular genetic level. Because their applications in clinical research have just begun, only a small number of studies based on GWA for a limited number of oral and craniofacial disease have been reported. However, those studies have yielded insights into underlying mechanisms of major oral and craniofacial diseases such as dental caries, periodontitis, cleft lip and palate, oral cancers, and autoimmune conditions showing promise for the clinical use of GWA in dentistry.

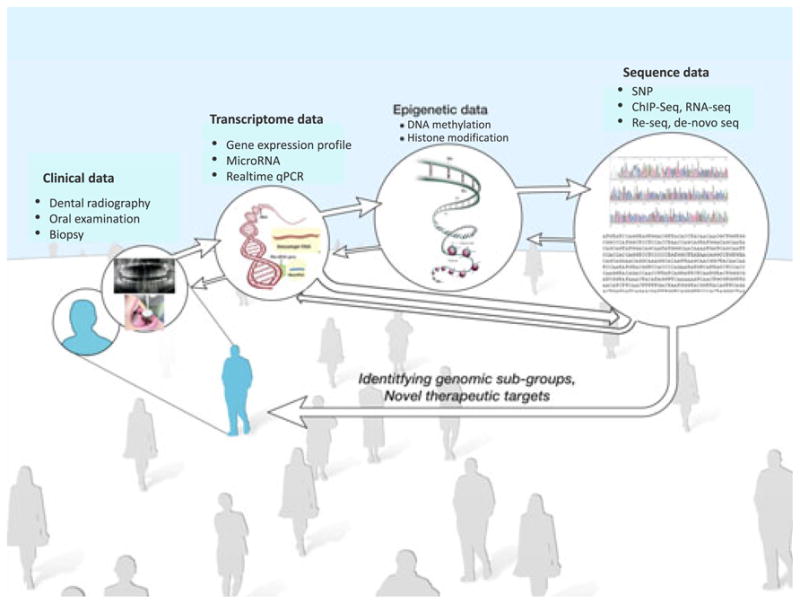

Even though we have described genetic variation, epigenetic changes, gene expression, and the oral microbiome separately, they all interact. A systemic approach combining information from DNA, RNA, and proteins, along with other factors such as the environment, is required to understand health and disease (Figure 1). Considering that high throughput data generated by GWA can easily reach millions of variables, this type of integrative analysis needs to handle millions × millions of interactions. A recent integrative genomic analysis evaluated one SNP from the interferon gamma gene along with subgingival bacterial colonization and disease status, although no association was found (Holla et al, 2011). In another study, copy number variations from SNP array were analyzed with gene expression array and found that a novel dysregulated MYC (v-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog) module as well as MYC itself plays a key role in carcinogenesis, suggesting a candidate integrative molecular signature associated with poor prognosis (Peng et al, 2011). Regardless of its promising future, integrative genomics is still very limited, especially because of the computing power to analyze high throughput data.

Figure 1.

Contributions of molecular genetic approaches to the study of oral and craniofacial diseases

Lack of consensus regarding study design such as population stratification, sample size, and multiple test corrections also adds confusion in the interpretation of published results. It should be also noted that many other issues such as statistical methods, intermediate phenotypes, and heritability of the phenotypes are also important, although they are not discussed in this review. GWA hold great promise for advancing our understanding of the genetic contributions to human diseases, risk factors for susceptibility and prognosis, and the development of individualized dental medicine. As described in this review, however, we are still in the early stages of the translation of genomics to clinic practice. Conversely, the rate of innovation continues to accelerate such that today’s health professional students will likely be one day diagnosing and treating oral and craniofacial disorders with knowledge and tools based on current research.

Footnotes

Author contributions

H. Kim drafted and finalized the manuscript. S. Gordon and R. Dionne drafted and edited the manuscript.

References

- Abe D, Kubota T, Morozumi T, et al. Altered gene expression in leukocyte transendothelial migration and cell communication pathways in periodontitis-affected gingival tissues. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:345–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J, Yang L, Paster BJ, et al. Oral microbiome profiles: 16S rRNA pyrosequencing and microarray assay comparison. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alevizos I, Alexander S, Turner RJ, Illei GG. MicroRNA expression profiles as biomarkers of minor salivary gland inflammation and dysfunction in Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:535–544. doi: 10.1002/art.30131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambatipudi S, Gerstung M, Gowda R, et al. Genomic profiling of advanced-stage oral cancers reveals chromosome 11q alterations as markers of poor clinical outcome. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel S, Apel C, Morea C, et al. Microflora associated with successful and failed orthodontic mini-implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:1186–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano M, Jiang J, Zhou X, et al. Current advances in identification of cancer biomarkers in saliva. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2009;1:296–303. doi: 10.2741/S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballestar E. An introduction to epigenetics. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;711:1–11. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8216-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaty TH, Murray JC, Marazita ML, et al. A genomewide association study of cleft lip with and without cleft palate identifies risk variants near MAFB and ABCA4. Nat Genet. 2010;42:525–529. doi: 10.1038/ng.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaty TH, Ruczinski I, Murray JC, et al. Evidence for gene-environment interaction in a genome wide study of nonsyndromic cleft palate. Genet Epidemiol. 2011;35:469–478. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell A, Bell D, Weber RS, El-Naggar AK. CpG island methylation profiling in human salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Cancer. 2011;117:2898–2909. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum S, Ludwig KU, Reutter H, et al. Key susceptibility locus for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on chromosome 8q24. Nat Genet. 2009;41:473–477. doi: 10.1038/ng.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton SH, Burt A, Stal S, et al. Family-based study shows heterogeneity of a susceptibility locus on chromosome 8q24 for nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:256–259. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretz WA, Rosa OP. Emerging technologies for the prevention of dental caries. Are current methods of prevention sufficient for the high risk patient? Int Dent J. 2011;61(Suppl 1):29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretz WA, Corby PM, Schork NJ, et al. Longitudinal analysis of heritability for dental caries traits. J Dent Res. 2005;84:1047–1051. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedar H, Bergman Y. Epigenetics of haematopoietic cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:478–488. doi: 10.1038/nri2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ES, Bittinger K, Haas AR, et al. Topographical continuity of bacterial populations in the healthy human respiratory tract. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:957–963. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0655OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo AP, Boches SK, Cotton SL, et al. Comparisons of subgingival microbial profiles of refractory periodontitis, severe periodontitis, and periodontal health using the human oral microbe identification microarray. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1421–1432. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conry JP, Messer LB, Boraas JC, Aeppli DP, Bouchard TJ., Jr Dental caries and treatment characteristics in human twins reared apart. Arch Oral Biol. 1993;38:937–943. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(93)90106-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EK, Lauber CL, Hamady M, et al. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science. 2009;326:1694–1697. doi: 10.1126/science.1177486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crielaard W, Zaura E, Schuller AA, et al. Exploring the oral microbiota of children at various developmental stages of their dentition in the relation to their oral health. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:22. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, et al. The human oral microbiome. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5002–5017. doi: 10.1128/JB.00542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Perez R, Campo-Trapero J, Cano-Sanchez J, et al. Methylation in oral cancer and pre-cancerous lesions (Review) Oncol Rep. 2011;25:1203–1209. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M, Xu JY, Fan Y. Altered expression of mRNA for HIF-1alpha and its target genes RTP801 and VEGF in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2010;16:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emamian ES, Leon JM, Lessard CJ, et al. Peripheral blood gene expression profiling in Sjogren’s syndrome. Genes Immun. 2009;10:285–296. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng G, Chen A, Vess T, Ginsburg GS. Genome technologies and personalized dental medicine. Oral Dis. 2012;18:223–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst FD, Uhr K, Teumer A, et al. Replication of the association of chromosomal region 9p21.3 with generalized aggressive periodontitis (gAgP) using an independent case-control cohort. BMC Med Genet. 2011;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gateva V, Sandling JK, Hom G, et al. A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1228–1233. doi: 10.1038/ng.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez S, Aguilera S, Alliende C, et al. Alterations in type I hemidesmosome components suggestive of epigenetic control in the salivary glands of patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1106–1115. doi: 10.1002/art.30212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant SF, Wang K, Zhang H, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a locus for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on 8q24. J Pediatr. 2009;155:909–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosen D, Bille C, Pedersen JK, et al. Recurrence risk for offspring of twins discordant for oral cleft: a population-based cohort study of the Danish 1936–2004 cleft twin cohort. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2468–2474. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He CF, Liu YS, Cheng YL, et al. TNIP1, SLC15A4, ETS1, RasGRP3 and IKZF1 are associated with clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus in a Chinese Han population. Lupus. 2010;19:1181–1186. doi: 10.1177/0961203310367918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holla LI, Hrdlickova B, Linhartova P, Fassmann A. Interferon-gamma +874A/T polymorphism in relation to generalized chronic periodontitis and the presence of periodontopathic bacteria. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Gao K, Pollard R, et al. Preclinical validation of salivary biomarkers for primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:1633–1638. doi: 10.1002/acr.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Ochiai K. Role of histone modification on transcriptional regulation and HIV-1 gene expression: possible mechanisms of periodontal diseases in AIDS progression. J Oral Sci. 2011;53:1–13. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.53.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson D, Ramberg P, Demmer RT, et al. Gingival tissue transcriptomes in experimental gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:599–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung DW, Che ZM, Kim J, et al. Tumor-stromal crosstalk in invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma: a pivotal role of CCL7. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:332–344. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HR, Jee YK, Kim YS, et al. Positive and negative associations of HLA class I alleles with allopurinol-induced SCARs in Koreans. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2011;21:303–307. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32834282b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapsogeorgou EK, Gourzi VC, Manoussakis MN, Moutsopoulos HM, Tzioufas AG. Cellular microRNAs (miRNAs) and Sjogren’s syndrome: candidate regulators of autoimmune response and autoantigen expression. J Autoimmun. 2011;37:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur J, Demokan S, Tripathi SC, et al. Promoter hypermethylation in Indian primary oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2367–2373. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Clark D, Dionne RA. Genetic contributions to clinical pain and analgesia: avoiding pitfalls in genetic research. J Pain. 2009;10:663–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KY, Kim J, Kim HJ, Nam W, Cha IH. A method for detecting significant genomic regions associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma using aCGH. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2010;48:459–468. doi: 10.1007/s11517-010-0595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Yoo YS, Park K, et al. Genomic aberrations in salivary duct carcinoma arising in Warthin tumor of parotid gland: DNA microarray and HER2 fluorescence in situ hybridization. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:1088–1091. doi: 10.5858/2010-0428-CRR1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimoto O, Sawada J, Shimoyama K, et al. Activation of the interferon pathway in peripheral blood of patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:310–316. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordi-Tamandani DM, Moazeni-Roodi AK, Rigi-Ladiz MA, et al. Promoter hypermethylation and expression profile of MGMT and CDH1 genes in oral cavity cancer. Arch Oral Biol. 2010;55:809–814. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer DM, White VL, Jenkins MC, Burian D. Examining smoking-induced differential gene expression changes in buccal mucosa. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:24. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuribayashi Y, Morita K, Tomioka H, et al. Gene expression analysis by oligonucleotide microarray in oral leukoplakia. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:356–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Na HS, Jeong SY, et al. Comparison of inflammatory microRNA expression in healthy and periodontitis tissues. Biocell. 2011;35:43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon KP, Klepac-Ceraj V, Schiffer HK, et al. Comparative analyses of the bacterial microbiota of the human nostril and oropharynx. MBio. 2010:1. doi: 10.112b/mBio.00129-10. Available at: http://mbio.asm.org/content/1/3/e00129-10.full.pdf+html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ley TJ, Mardis ER, Ding L, et al. DNA sequencing of a cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukaemia genome. Nature. 2008;456:66–72. doi: 10.1038/nature07485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Huang H, Sun L, et al. MiR-21 indicates poor prognosis in tongue squamous cell carcinomas as an apoptosis inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3998–4008. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima JA, Santos VR, Feres M, de Figueiredo LC, Duarte PM. Changes in the subgingival biofilm composition after coronally positioned flap. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:68–73. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572011000100014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Z, Kong J, Jia P, et al. Analysis of oral microbiota in children with dental caries by PCR-DGGE and barcoded pyrosequencing. Microb Ecol. 2010;60:677–690. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9712-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo WT, Jin L, Cheung MN, Wang M, Chow LW. Epigenetic change in E-cadherin and COX-2 to predict chronic periodontitis. J Transl Med. 2010;8:110. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunde ML, Warnakulasuriya S, Sand L, et al. Gene expression analysis by cDNA microarray in oral cancers from two Western populations. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:1083–1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meguro A, Inoko H, Ota M, et al. Genetics of Behcet disease inside and outside the MHC. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:747–754. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael D, Soi S, Cabera-Perez J, et al. Microarray analysis of sexually dimorphic gene expression in human minor salivary glands. Oral Dis. 2011;17:653–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01816.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell LE. Twin studies in oral cleft research. In: Wyszynski DF, editor. Cleft lip and palate. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. pp. 214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuki N, Meguro A, Ota M, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify IL23R-IL12RB2 and IL10 as Behcet’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:703–706. doi: 10.1038/ng.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt CE, Lamont RJ. Porphyromonas gingivalis induction of microRNA-203 expression controls suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 in gingival epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2632–2637. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00082-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougeot JL, Bahrani-Mougeot FK, Lockhart PB, Brennan MT. Microarray analyses of oral punch biopsies from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients treated with chemotherapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JC. Gene/environment causes of cleft lip and/or palate. Clin Genet. 2002;61:248–256. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasidze I, Li J, Quinque D, Tang K, Stoneking M. Global diversity in the human salivary microbiome. Genome Res. 2009;19:636–643. doi: 10.1101/gr.084616.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen CQ, Sharma A, Lee BH, et al. Differential gene expression in the salivary gland during development and onset of xerostomia in Sjogren’s syndrome-like disease of the C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R56. doi: 10.1186/ar2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nossa CW, Oberdorf WE, Yang L, et al. Design of 16S rRNA gene primers for 454 pyrosequencing of the human foregut microbiome. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;16:4135–4144. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i33.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S, Tateishi Y, Tatemoto Y, et al. Enhanced expression of Toll-like receptor 2 in lesional tissues and peripheral blood monocytes of patients with oral lichen planus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:335–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BY, Sull JW, Park JY, Jee SH, Beaty TH. Differential parental transmission of markers in BCL3 among Korean cleft case-parent trios. J Prev Med Public Health. 2009;42:1–4. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2009.42.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paula-Silva FW, D’Silva NJ, da Silva LA, Kapila YL. High matrix metalloproteinase activity is a hallmark of periapical granulomas. J Endod. 2009;35:1234–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng CH, Liao CT, Peng SC, et al. A novel molecular signature identified by systems genetics approach predicts prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SK, Pavicevic Z, Du Z, et al. Pro-inflammatory genes as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32512–32521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remmers EF, Cosan F, Kirino Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the MHC class I, IL10, and IL23R-IL12RB2 regions associated with Behcet’s disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:698–702. doi: 10.1038/ng.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reutter H, Birnbaum S, Mende M, et al. TGFB3 displays parent-of-origin effects among central Europeans with nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. J Hum Genet. 2008;53:656–661. doi: 10.1007/s10038-008-0296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubini M, Brusati R, Garattini G, et al. Cystathionine beta-synthase c.844ins68 gene variant and non-syndromic cleft lip and palate. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;136A:368–372. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scapoli L, Palmieri A, Lo Muzio L, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of oral carcinoma identifies new markers of tumor progression. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;23:1229–1234. doi: 10.1177/039463201002300427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer AS, Richter GM, Groessner-Schreiber B, et al. Identification of a shared genetic susceptibility locus for coronary heart disease and periodontitis. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer AS, Richter GM, Nothnagel M, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies GLT6D1 as a susceptibility locus for periodontitis. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:553–562. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer JR, Wang X, Feingold E, et al. Genome-wide association scan for childhood caries implicates novel genes. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1457–1462. doi: 10.1177/0022034511422910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao C, Sun W, Tan M, et al. Integrated, genome-wide screening for hypomethylated oncogenes in salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4320–4330. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchipkova AY, Nagaraja HN, Kumar PS. Subgingival microbial profiles of smokers with periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1247–1253. doi: 10.1177/0022034510377203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Kubota T, Nakasone N, et al. Microarray and quantitative RT-PCR analyses in calcium-channel blockers induced gingival overgrowth tissues of periodontitis patients. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozuka K, Uzawa K, Fushimi K, et al. Downregulation of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 in oral squamous cell carcinoma: correlation with tumor progression and poor prognosis. Oncology. 2009;76:387–397. doi: 10.1159/000215580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon MC, Carnelio S, Gudattu V. Molecular analysis of oral squamous cell carcinoma: a tissue microarray study. Indian J Cancer. 2010;47:166–172. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.63013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M, Xiao C, Wang T, et al. Study of the differentially expressed genes in pleomorphic adenoma using cDNA microarrays. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011;17:765–769. doi: 10.1007/s12253-011-9384-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suazo J, Santos JL, Jara L, Blanco R. Parent-of-origin effects for MSX1 in a Chilean population with nonsyndromic cleft lip/palate. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2011–2016. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sull JW, Liang KY, Hetmanski JB, et al. Differential parental transmission of markers in RUNX2 among cleft case-parent trios from four populations. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32:505–512. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sull JW, Liang KY, Hetmanski JB, et al. Maternal transmission effects of the PAX genes among cleft case-parent trios from four populations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:831–839. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabeta K, Shimada Y, Tai H, et al. Assessment of chromosome 19 for genetic association in severe chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2009;80:663–671. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao XA, Li CY, Xia J, et al. Differential gene expression profiles of whole lesions from patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:427–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KE, Chung SA, Graham RR, et al. Risk alleles for systemic lupus erythematosus in a large case-control collection and associations with clinical subphenotypes. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Yamada T, Mikoya T, et al. A type of familial cleft of the soft palate maps to 2p24.2-p24.1 or 2p21-p12. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:124–126. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueta M, Sotozono C, Nakano M, et al. Association between prostaglandin E receptor 3 polymorphisms and Stevens-Johnson syndrome identified by means of a genome-wide association study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1218–1225. e1210. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vekony H, Leemans CR, Ylstra B, et al. Salivary gland carcinosarcoma: oligonucleotide array CGH reveals similar genomic profiles in epithelial and mesenchymal components. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade WG. Has the use of molecular methods for the characterization of the human oral microbiome changed our understanding of the role of bacteria in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease? J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl 11):7–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waseem A, Ali M, Odell EW, Fortune F, Teh MT. Downstream targets of FOXM1: CEP55 and HELLS are cancer progression markers of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherley-White RC, Ben S, Jin Y, et al. Analysis of genomewide association signals for nonsyndromic cleft lip/palate in a Kenya African Cohort. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:2422–2425. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie YF, Shu R, Jiang SY, Liu DL, Zhang XL. Comparison of microRNA profiles of human periodontal diseased and healthy gingival tissues. Int J Oral Sci. 2011;3:125–134. doi: 10.4248/IJOS11046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki M, Fujii S, Murata Y, Hayashi R, Ochiai A. High expression level of geminin predicts a poor clinical outcome in salivary gland carcinomas. Histopathology. 2010;56:883–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Zhao M, Wu X, et al. Hypomethylation and overexpression of CD70 (TNFSF7) in CD4+ T cells of patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. J Dermatol Sci. 2010;59:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu ZW, Zhong LP, Ji T, et al. MicroRNAs contribute to the chemoresistance of cisplatin in tongue squamous cell carcinoma lines. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q, Blanton SH, Hecht JT. Genetic causes of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;70:107–113. doi: 10.1159/000322486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Cairns M, Rose B, et al. Alterations in miRNA processing and expression in pleomorphic adenomas of the salivary gland. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2855–2863. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Pan HY, Zhong LP, et al. Fos-related activator-1 is overexpressed in oral squamous cell carcinoma and associated with tumor lymph node metastasis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010a;39:470–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Barros SP, Niculescu MD, et al. Alteration of PTGS2 promoter methylation in chronic periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2010b;89:133–137. doi: 10.1177/0022034509356512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Crivello A, Offenbacher S, et al. Interferon-gamma promoter hypomethylation and increased expression in chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2010c;37:953–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]