Abstract

An understanding of the organization of the pulvinar complex in prosimian primates has been somewhat elusive due to the lack of clear architectonic divisions. In the current study, we revealed features of the organization of the pulvinar complex in galagos by examining superior colliculus (SC) projections to this structure and comparing them with staining patterns of the vesicular glutamate transporter, VGLUT2. Cholera toxin subunit β (CTB), fluroruby (FR) and wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (WGA-HRP) were placed in topographically different locations within the SC. Our results showed multiple topographically organized patterns of projections from the SC to several divisions of the pulvinar complex. At least two topographically distributed projections were found within the lateral region of the pulvinar complex, and two less obvious topographical projection patterns were found within the caudomedial region, in zones that stain darkly for VGLUT2. The results, considered in relation to recent observations in tree shrews and squirrels, suggest that parts of the organizational scheme of the pulvinar complex in primates are present in rodents and other mammals.

Keywords: primate, tectum, visual system, thalamus, evolution

Introduction

The extrageniculate pathway, relaying visual information from the retina through the superior colliculus and pulvinar to visual cortex, has been found in all studied mammals (Harting et al., 1973; Diamond et al., 1976). This pathway provides an alternate route for visual information to reach extrastriate visual areas outside of the classical geniculate pathway projecting to striate cortex. Lesion studies suggest that the extrageniculate pathway is especially important for vision in some mammals such as tree shrews (Casagrande and Diamond, 1974) and squirrels (Levey, 1973; Diamond et al., 1973; Wagor, 1978). It may also be important for vision in prosimian galagos, as many visual abilities are maintained in galagos after striate cortex is removed (Marcotte and Ward, 1980, but see Atencio et al., 1975). In humans and Old World macaques, this pathway seems less important, but it may be involved in the unconscious aspects of vision termed blindsight (Poppel et al., 1973; Stoerig and Cowey, 2007; Tamietto et al., 2010).

Studying this extrageniculate pathway in galagos is of special interest because galagos, and other prosimian primates, have brains that appear to have changed the least from those of early primates (Radinsky, 1975; Preuss and Goldman-Rakic, 1991a, b; Preuss and Kaas 1993; Kaas, 2007a). As such, our understanding of the organization of the extrageniculate pathway in galagos can provide information on specializations and common features of primates, and perhaps suggest relationships to the pulvinar patterns of rodents and tree shrews, which are members of the Euarchontoglire clade with primates (Murphy et al., 2001; Kaas et al., 2002, 2005; Meredith et al., 2011).

In most species studied, dense projections from the superior colliculus terminate within the caudal aspect of the pulvinar complex. In squirrels and other rodents, tectal projections terminate diffusely within the caudal aspect of the pulvinar, while rostrally, the projections are more focused and topographic (Robson and Hall 1977; Crain and Hall, 1980; Kuljis and Fernandez, 1982; Ling et al., 1997; Takahashi et al., 1985; Baldwin et al., 2011). Tree shrews also have projections that terminate diffusely within the caudal aspect of the pulvinar and additional, more focused, projections that terminate in more rostral locations (Luppino et al., 1998; Chomsung et al., 2008). In anthropoid primates, tectal projections terminate in two caudal locations within the inferior pulvinar and additional projections to more rostral and lateral positions have been observed in New World monkeys, but it is unclear if these more rostral and lateral projections are present in Old World monkeys (Stepniewska et al., 2000). Finally, previous studies in galagos have shown dense projections from the superior colliculus to the caudal aspect of the inferior pulvinar (Glendenning et al., 1975; Wong et al, 2008), with less dense projections extending into more rostrolateral locations (Diamond et al., 1992). An understanding of the differences and consistencies in the patterns of tectal projections across different members of the Euarchotoglire clade could provide insights into how the pulvinar, and the extrageniculate pathway through the pulvinar to cortex evolved.

Considerable progress has been made in recent years in understanding the organization of the pulvinar complex in anthropoid primates, where four nuclear divisions of the inferior pulvinar have been identified (Stepniewska et al., 1997, 2000; Stepniewska, 2004; Jones, 2007). Much less is known about the divisions of the pulvinar of galagos, mainly because of the lack of architectonic markers that distinguish between divisions (Beck and Kaas, 1998; Wong et al., 2009). Therefore, it has been difficult to identify homologous pulvinar structures between galagos and other primates, and between primates and rodents (see Lyon et al, 2003 for review).

The current study had two main goals. The first was to determine the distribution pattern of the vesicular glutamate transporter, VGLUT2, within the pulvinar complex in galagos. This transporter has been shown to be a general marker of subcortical projections to the dorsal thalamus and sensory cortex (Herzog et al., 2001; Hackett et al., 2011; Balaram et al., 2011) and therefore, could indicate where tectal terminations are located within the galago pulvinar (Balaram et al., 2011). The second goal was to directly determine the extent and organization of tectal projections to the pulvinar complex in galagos. As the projections from the superior colliculus to the different parts of the pulvinar have been described as topographic (retinotopic) or diffuse, we also wanted to evaluate this aspect of the tectal projection pattern in galagos. Our results show that VGLUT2 is a robust marker for some of the superior colliculus projections to the pulvinar complex, specifically projections to caudal subdivisions that project to higher order visual areas in temporal cortex. We also found at least two additional tectal projections to more rostral and lateral positions within the pulvinar complex that are not associated with VGLUT2 dense staining. Cortical projections arising from these pulvinar divisions are to occipital visual areas involved with early stages of cortical processing. Most importantly, our results identify homologous divisions of the pulvinar complex in prosimian and anthropoid primates, and suggest how features of the primate pulvinar evolved from non-primate ancestors.

Methods

Tectopulvinar projections and histological architecture of the pulvinar were studied in 10 adult galagos (Otolemur Garnettii) (results from 7 are illustrated). All surgical procedures were conducted in accordance with an approved protocol by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and followed the guidelines published by the National Institute of Health.

Surgical procedures

The methods in the present study are similar to those described elsewhere (Wong et al., 2009; Baldwin et al., 2011 and Baldwin and Kaas, 2012). Animals were initially anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of ketamine hydrochloride (120mg/kg) and anesthesia was maintained for the rest of the surgical procedures using 0.5 to 2% isoflurane delivered through a tracheal tube. Lidocaine was placed in both ears, as well as along the midline of the scalp. An incision was then placed along the midline of the scalp and part of the left skull was exposed. A small craniotomy was made over the left parietal and occipital lobes. The dura was removed and medial portions of the parietal and occipital lobes were removed by aspiration to visualize the left superior colliculus. In 4 cases, injections of anatomical tracers were made within the left superior colliculus after cortical aspirations, while in an additional 4 cases, the medial aspect of the right hemisphere was retracted and injections were made along the medial wall of the right superior colliculus. An additional case was used for architectonic analysis only, and the final case was used for western blot analysis of the VGLUT2 antibody. Tracers were pressure injected at depths of 0.7 to 1.3mm from the surface of the superior colliculus using a Hamilton syringe fitted with a glass pipette beveled to a fine tip. The tracers used in this experiment were 0.5–1 μl of cholera toxin subunit β (CTB: Molecular Probes Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; 10% in distilled water), 0.5 to 1 μl of fluoro ruby (FR: Molecular Probes Invitrogen: 10% in phosphate buffer), and 0.1ul of wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (WGA-HRP: Sigma, St. Louis, MO; 2% in distilled water). Any tracer leakage during injections was removed with sterile saline flushes in order to prevent contamination of surrounding brain tissue. Injections lasted approximately 5 minutes to allow tracer to diffuse into the brain. Gelfoam was then placed into the aspirated region of cortex and a layer of gelfilm was placed over the brain within the region of the craniotomy. An artificial skullcap of dental cement covered the opening and was sealed to the skull. Surgical staples were used to close the incision site. Animals were then taken off anesthesia, and monitored during recovery. Once fully awake, galagos were given 0.3mg/kg of Buprenex analgesic and were returned to their home cage.

Histology

Five to seven days after surgery, animals were given a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (80mg/kg intravenously) and perfused with phosphate-buffer (PB; pH 7.4), followed by 2% paraformaldehyde in PB, and finally 2% paraformaldehyde in PB with 10% sucrose. After the brains were removed, the cortex was separated from underlying brain structures. The cortex from the intact hemisphere was flattened and used for another study (Baldwin and Kaas, 2012). The thalamus and brainstem were then placed in 30% sucrose solution for cryoprotection and stored at 4°C for 20 to 48 hours.

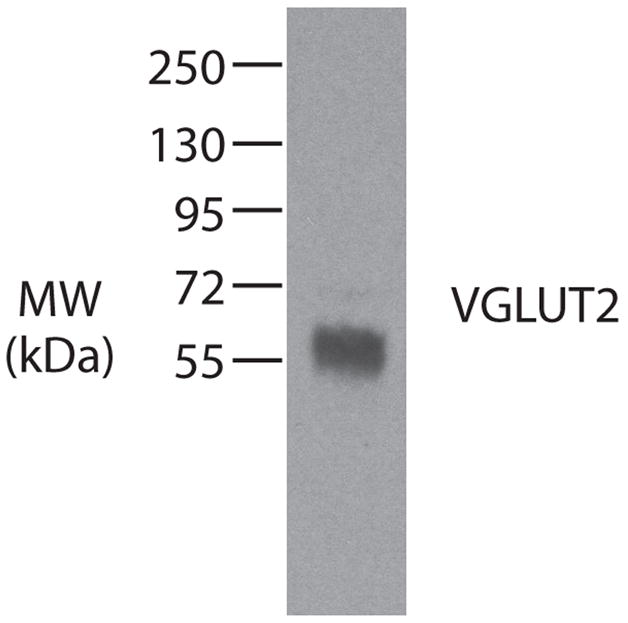

The thalamus and brainstem were cut in the coronal plane using a freezing microtome at a thickness of 40 μm. The tissue was saved in 5 series. One to three series were processed for anatomical tracers such as CTB using a histological procedures described in Baldwin et al., (2011), or WGA-HRP using procedures of Gibson et al. (1984), or were immediately mounted onto glass slides for fluorescent analysis of FR. Remaining series were processed for two to three of the following stains: cytochrome oxidase, CO (Wong-Wiley, 1979), acetylcholinesterase, AChE (Geneser-Jensen and Blackstand, 1971), vesicular glutamate transporter 2, VGLUT2 (mouse monoclonal anti-VGLUT2 from Millipore, Billerica, MA: 1:5000). For one case, two series of tissue were processed for VGLUT2 mRNA using previously described in situ hybridization techniques (Balaram et al., 2011). Table 1 lists all antibodies used. The CTB antibody was tested on galago brain tissue with no CTB injections and this control failed to label any cells or patches of axon terminals. The VGLUT antibody was tested against galago brain tissue using standard western blot techniques (Baldwin et al., 2011) and showed a single band at 56 kDa (Fig. 1), the known molecular weight of VGLUT2 (Aihara et al., 2000).

Table 1.

Antibody Characterization

| Antigen | Immunogen | Manufacturer | Dilution Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholera toxin subunit B | Purified CTB isolated from Vibrio Cholerae | List Biological Laboratories Inc. (Campbell, CA), goat polyclonal #703 | 1:5000 |

| Vesicular glutamate 2 transporter | Recombinant protein from rat VGLUT2 | Chemicon now part of Millipore, (Billerica, MA), mouse monoclonal, #MAB5504 | 1:5000 |

Figure 1.

Western blot characterization of the VGLUT2 antibody in galago striate cortex. The antibody recognizes a 56 kDa protein, which is the known molecular weight of VGLUT2.

Data analysis

The locations of CTB, FR and WGA-HRP labeled axon terminals and cell bodies were plotted using an XY plotter (Neurolucida system: MicroBright, Williston, VT). Digital images of tissue sections were taken using a DXM1200F digital camera mounted to a Nikon E800S microscope (Nikon Inc., Melville, NY). Images were adjusted for brightness and contrast using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Inc. USA), but were otherwise not altered.

Labeled terminals and cell locations were related to thalamic architecture by matching plotted sections to adjacent brain sections using common blood vessels in Adobe Illustrator. Injection sites, anterogradely labeled terminals, and retrogradely labeled cell bodies in plotted sections were referenced to CO, VGLUT2, and AChE stained sections.

The locations of injection sites within the superior colliculus were placed in reference to dorsal views of the structure, after reconstructions from serial coronal sections. This dorsal reconstruction was then aligned with a previously determined retinotopic map of the contralateral visual hemifield (Lane et al., 1973). As in other primates, the upper visual quadrant is represented medially, the lower visual quadrant, laterally, peripheral vision caudally, and central vision, rostrally within the superior colliculus of galagos.

Results

In the present study, injections of fluororuby (FR), cholera toxin subunit B (CTB), or wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (WGA-HRP) were placed at various locations within the superior colliculus and the resulting patterns of anterograde and retrograde label were examined within subcortical visual structures. An emphasis was placed on investigating the superior colliculus projections to the pulvinar complex. Additionally, architectonic borders within and between subcortical structures were evaluated using cytochrome oxidase, acetylcholinesterase, and VGLUT2 preparations. The results indicate that there are multiple projections to the pulvinar complex from the superior colliculus. At least two projections terminate within domains of the posterior pulvinar that stain strongly for VGLUT2, while two or three projections terminate in more rostrolateral divisions of the pulvinar complex that stain weakly for VGLUT2. Here we briefly describe the architectonic characteristics used to identify thalamic and brain stem nuclei, including subdivisions within the pulvinar complex, followed by descriptions of the superior colliculus connection patterns within these subcortical visual structures.

Architecture of the superior colliculus and pulvinar

Superior colliculus

Determining the laminar architecture of the superior colliculus was important for identifying the locations of tracer placements. The superior colliculus of galagos has seven main layers (Fig. 2A). The superficial layers consisting of the stratum zonale (SZ), the stratum griseum superficiale (SGS), and the stratum opticum (SO) are visual in function, while deeper layers are associated with integrating multisensory information and motor functions (See Kaas and Huerta, 1988; May 2006 for review). The SGS and the stratum griseum intermediale (SGI) can be distinguished by their dark CO staining relative to the SO, and stratum album intermediate (SAI) (Fig. 2A). In galagos, the cells that project to the pulvinar complex are found within the lower SGS (Raczkowski and Diamond, 1981). These cells in the lower SGS also show strong expression of VGLUT2 mRNA (Fig. 2B) (Balaram et al., 2011), which correlates to VGLUT2 terminal labeling seen in the pulvinar complex. All injection sites included the SGS in the present study. A previously determined retinotopic map of the superior colliculus (Lane et al., 1973) was used to estimate the retinotopic locations of our injection sites.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the superior colliculus and dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus in galagos. A. The superior colliculus can be subdivided into seven main layers based on cytochrome oxidase (CO): stratum zonale (SZ), stratum griseum superficiale (SGS), stratum opticum (SO), stratum griseum intermediate (SGI), stratum album intermediate (SAI), stratum griseum profundum (SGP), and stratum album profundum (SAP). B. Shows a cross section of the superior colliculus processed for VGLUT2 mRNA expression. Strong expression of VGLUT2 mRNA can be seen within the lower SGS. Scale bar is 1mm.

Pulvinar Complex

In galagos, the pulvinar complex, which is part of the dorsal thalamus, extends as far caudal as the medial geniculate nucleus and as far rostral as the ventral posterior nucleus. The pulvinar of primates is typically divided into four main subdivisions, the anterior pulvinar, the medial pulvinar, the lateral pulvinar, and the inferior pulvinar (Stepniewska and Kaas, 1997; Stepniewska et al., 1999; Kaas and Lyon, 2007; Jones et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2009). Identifying nuclei or subdivisions within the pulvinar complex of galagos has been difficult (Wong et al., 2009), mainly because the typical staining techniques that reveal such nuclei in anthropoid primates have not been as informative in galagos. In the present report, we defined borders between and within the medial, lateral, and inferior pulvinar, focusing on the caudal half of the pulvinar complex. While defining architectonic borders, and therefore nuclei within the pulvinar complex of galagos, remains difficult, the addition of sections processed for VGLUT2 proved to be useful.

VGLUT2 protein staining resulted in a robust border visible within the caudomedial aspect of the pulvinar complex (Fig. 3D, H and L). Based on comparative studies of VGLUT2 staining and superior colliculus projections, the region that stains darkly for VGLUT2 is part of the inferior pulvinar of anthropoid primates (See discussion). In the present report, we refer to this region as the posterior pulvinar because of its general location within the pulvinar complex, and also because this domain extends dorsally to the most dorsal aspect of the pulvinar complex—a region often previously attributed to the medial, or superior pulvinar in galagos (Glendenning et al., 1975; Symonds and Kaas, 1979; Diamond et al, 1992; Wong et al., 2009). The VGLUT2 staining region appears to be composed of two subdivisions (Fig. 4), and therefore we refer to these two regions as the posterior pulvinar (Pp) and the posterior central pulvinar (Ppc). At the most caudal extent, the posterior pulvinar, inferior and possibly parts of the lateral pulvinar are present (Fig. 3A–D). In VGLUT2 stained sections, the medial half of the pulvinar stained darkly for VGLUT2 protein with two patches of VGLUT2 terminals that fused together ventrally (Figs. 3D, H, and 4). Caudally, the lateral aspect of the pulvinar stained weakly for VGLUT2 (Fig. 3D). This pattern of VGLUT2 staining was sometimes matched in cytochrome oxidase stained sections with dark CO staining corresponding to the dark VGLUT2 staining (Fig. 3B). However, the pattern observed using CO and VGLUT2 was not noticeable in AChE stained sections. Progressing rostrally, the VGLUT2 darkly staining region is replaced by the medial pulvinar, which stains lightly for VGLUT2. As the medial pulvinar emerges, the posterior pulvinar exits medially (Fig. 3D, H, L, P, T). Again, this progression was also somewhat visible in ideally stained CO stained sections, but not apparent in AChE stained sections.

Figure 3.

Subdivisions of the pulvinar complex in prosimian galagos revealed in coronal sections of the pulvinar processed for CO, AChE, or VGLUT2. The line drawings on the far left column (A, E, I, M, Q) depict the borders within the pulvinar complex in coronal sections based on different staining procedures. Cytochrome oxidase (B, F, J, N, R) staining patterns reveal the medial pulvinar complex (J, N, R) because of its lighter CO staining intensity relative to surrounding subdivisions of the pulvinar complex. In ideal staining, the posterior region of the pulvinar can be demarcated from surrounding subdivisions by its darker CO staining pattern (B and F). AChE stained sections help indicate the medial pulvinar from surrounding subdivisions by the lighter AChE staining in this subdivision (K, O, S); however, there is little difference in staining patterns between the posterior, inferior, and lateral subdivisions. Dense VGLUT2 staining is present within the posterior pulvinar complex (D, H, L, P) located medially within the whole pulvinar complex. This staining pattern matches the pattern observed in CO under ideal CO staining procedures. Additionally, a protrusion in the most ventrolateral aspect of the posterior division is evident (D, H). Additionally, a region at the most lateral aspect of the lateral pulvinar stains darkly for VGLUT2 (P and T). This staining pattern is also evident within AChE stained sections (K, O, S) by slightly darker AChE staining, as well as an apparent septa between this region and the rest of the lateral pulvinar (S). Caudal sections are presented at the top of the panel, while rostral sections are presented progressively towards the bottom of the panel. Scale bar is 1mm.

Figure 4.

VGLUT2 staining in the caudal half of the pulvinar complex in galagos. Photomicrographs of VGLUT2 stained sections from the most caudal (top) to more rostral sections (bottom) through the pulvinar complex in caudal (top panel). Within the VGLUT2 staining region, to divisions are present. One large division along the medial aspect of the caudal pulvinar, the posterior pulvinar (Pp), and an additional, smaller division located ventrolaterally, the posterior central pulvinar (Ppc). Scale bar is 1mm.

The lateral pulvinar (PL) lies along the lateral aspect of the pulvinar complex. PL can be distinguished from the medial pulvinar (PM) by its darker staining in CO and AChE stained sections (Fig. 3J, K, N, O, R and S). Determining the border between PL and the inferior pulvinar (PI) was more difficult, but in ideally stained sections there was a slight contrast change in CO and AChE stained sections at the border of PL and PI (Fig. 3N). The medial pulvinar stains weakly for CO, and AChE (Fig. 3J, K, N, O, R, S) and was located mediodorsally within the rostral half of the pulvinar complex.

On the most lateral aspect of the pulvinar complex there is a thin strip of tissue that is separable from PL by what could be a thin septum (see Fig. 3R, S, O). This strip of tissue also stains more darkly for AChE (Fig. 3K, O, S) and VGLUT2 (Fig. 3P, T) and is reminiscent of the S subdivision of the pulvinar described by Gutierrez et al. (1995) in macaques, but few reports have described such a region in New World monkeys. In more rostral sections, (not shown), this strip remains thin, never widening. We did not observe tectal projections to this region.

Connections of the superior colliculus

Projections to the pulvinar complex

Projections to the pulvinar complex were studied in 8 cases after placing injections of anatomical tracers of variable sizes and locations in the superior colliculus. We identified at least four, likely topographic, projections to the pulvinar complex after superior colliculus injections. Two of these projections were to two darkly staining VGLUT2 subdivisions of the pulvinar complex located within the caudomedial aspect, while two or three were to regions of the rostrolateral pulvinar that stained weakly for VGLUT2 and are likely within inferior and lateral subdivisions. All terminal projections were to the ipsilateral pulvinar complex, and no terminals were observed within the contralateral pulvinar after superior colliculus injections.

Projections to VGLUT2 staining divisions of the pulvinar complex

The results from cases 09-34 (Fig. 5) and 10-51 (Fig. 6) are especially informative as they had both CTB and FR injections in the superior colliculus, as well as sections processed for the VGLUT2 protein. In both cases 09-34 (Fig. 5), and 10-51 (Fig. 6), two clear patches of terminal label were present within the two VGLUT2 staining domains in the caudal aspect of the pulvinar complex (Fig. 7). One larger, dense terminal field was located in the division we defined as the posterior pulvinar (Pp), and a second smaller terminal field was within what we identify as the posterior central pulvinar (Ppc). Within Pp, multiple patches of label for each injection site were present (Fig. 7B and 7A, section 173). However, it is unclear if these multiple patches are a result of fiber tracts running through this division, breaking up a single focus of superior colliculus projections within Pp, or are present because Pp has further subdivisions.

Figure 5.

Reconstruction of the terminal label within the pulvinar complex after CTB and FR injections in the superior colliculus for case 09-34. A. Reconstruction of the terminal label within the brainstem and thalamus. Small red dots represent FR terminal label, while red triangles represent retrogradely labeled cells. Blue dots represent CTB terminal label, and blue squares represent retrogradely labeled cells. Solid lines indicate the borders of nuclei within the brainstem and thalamus, while dashed lines within the pulvinar complex represent the proposed borders determined using VGLUT2, CO, and AChE staining patterns. Pp is the posterior pulvinar, PI is the inferior pulvinar, PM is the medial pulvinar, LGNd is the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus, LGNv is the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus, MGN is the medial geniculate nucleus, Lim is the limitans, Rt is the reticular nucleus. B. is a dorsal view reconstruction depicting the location of the injection sites within the superior colliculus with red representing the fluoro ruby injection site, and blue representing the CTB injection site. Lines depicting the topographic layout of the superior colliculus were superimposed onto the reconstruction from results of Lane et al. 1973. The grey regions around the main SC circle represent the medial and lateral walls of the superior colliculus flattened and unfolded to the sides. In this and following figures the plus and minus signs indicate upper and lower visual field locations along the medial/lateral extent of the superior colliculus. Photomicrographs of the CTB and FR injection sites in coronal sections of the superior colliculus are indicated in C and D respectively. E and F. are photomicrographs of the terminal label depicted in the outlined boxes of A section 158. Scale bars for A, C, and D are 1mm, E and F are 0.5mm.

Figure 6.

Reconstruction of terminal label within the pulvinar complex after a superior colliculus injection in case 10-51. A and B are photomicrographs of the fluoro ruby (FR), and cholera toxin subunit B (CTB) injection sites in coronal sections within the superior colliculus. C shows the dorsal view reconstruction of the FR and CTB injection sites throughout the flattened superior colliculus. D and E are close up photomicrographs of CTB and FR terminal label in sections 138 and 143 shown in F respectively. F is the reconstruction of terminal CTB (blue dots) and FR (red dots) terminal label within the pulvinar complex. Retrogradely labeled FR cells are also shown (red triangles). Scale bars for A, B and F are 1mm, D is 0.5mm and E is 0.25mm.

Figure 7.

Close up view of the terminal label within sections 173 and 178 from case 09-34 (A) and sections 138 and 142 of case 10-51 (B) with adjacent VGLUT2 stained sections. Two patches of label for each tracer are noticeable. One set of isolated patches of CTB and FR terminal label are within the larger medial body of the VGLUT2 staining region, which we have tentatively named posterior pulvinar (Pp). Additional patches of terminal label are present within the protrusion of VGLUT2 staining off the most ventrolateral aspect of Pp, for which we tentatively name posterior central pulvinar (Ppc). Scale bar is 1mm.

The CTB injection sites for cases 09-34 (Fig. 5) and 10-51 (Fig. 6) were almost identical in location, and included portions of both upper and lower visual quadrants. The FR injection sites in these two cases were similar in that they were more rostrally located within the superior colliculus than the CTB injection sites and therefore were within more central vision representations of the superior colliculus. The FR label within Ppc for both cases was located ventral to the CTB label, suggesting that central vision is represented ventrally within Ppc. Additionally, both the CTB and FR zones of label progressed laterally from more caudal to rostral locations within Ppc suggesting bands of isoeccentricity that run through Ppc in a rostrolateral trajectory. Finally, the pattern of label from the more rostral injections of FR was more pronounced in rostral Ppc than label from the more caudally placed injections of CTB. Thus, in case 09-34, the CTB label was quite dense caudally, but less dense rostrally (Fig. 5 sections 178-163), and in case 10-51, CTB terminations were in the most caudal section of Ppc (Fig. 6 section 133), but FR terminal label in Ppc did not emerge until the subsequent section (Fig. 6 section 138). This suggests that central vision is represented rostrally within Ppc, and peripheral vision is represented caudally.

The retinotopic organization within the larger Pp was less clear. Yet, the patches of terminal label within Pp for different injection sites in the superior colliculus did not overlap much, suggesting that a topographic organization is present. The terminal label, for most cases, was present throughout the full rostrocaudal extent of Pp, therefore, making it difficult to determine the presence of a rostral/caudal topographic pattern (Figs. 5–9). Possibly, the caudal superior colliculus projects to ventromedial Pp, while the rostral aspect projects more to dorsolateral Pp.

Figure 9.

The distribution of terminal label within the pulvinar complex after an injection in the caudolateral aspect of the superior colliculus of a galago, case 11-41. A is a photomicrograph of the FR injection site within the superior colliculus. The location is within the caudal and lateral aspect of the superior colliculus representing the peripheral upper field. B is a reconstruction of terminal label within the pulvinar complex. C is an estimate of the location of the injection site in the dorsal view of the superior colliculus. D and E are photomicrographs of terminal label within sections 123 and 133 of B respectively. Scale bars for A and B are 1mm, Scale bars for A and B are 1mm, C and D are 0.25mm.

Projections to non- or weakly-VGLUT2 staining divisions of the pulvinar complex

Determining borders between other subdivisions of the pulvinar complex was difficult. Therefore, we describe patches of labeled terminals outside of the VGLUT2 region based on their relative locations within the pulvinar. There were usually up to two patches of terminations in the most lateral portions of the pulvinar, one dorsal and one ventral (Figs. 5, and 6, but not Figs. 8 and 9), and one additional patch located more medially (Figs. 5–9). The more medial patch may be within the inferior pulvinar, and the more lateral patches are likely within the lateral pulvinar.

Figure 8.

Terminal label within the pulvinar complex after WGA-HRP injection into the superior colliculus of galago case 11-61. A Dark field photomicrographs of WGA-HRP label within the pulvinar complex with borders determined using cytochrome oxidase staining shown in white. The extent of the tracer spread is depicted in the dorsal view reconstruction of the superior colliculus B. Scale bar for A is 1mm.

The most lateral tectal termination zone within the pulvinar is retinotopically organized. Injections within the representation of the upper visual quadrant in the superior colliculus labeled terminals lateral to those produced by injections within the lower visual quadrant representation (Fig. 5 and compare with Fig. 8). In case 09-34 (Fig. 5) the FR injection was located at the upper field representation and produced labeled terminals along the lateral aspect of the lateral pulvinar, while cases 10-51 (Fig. 6) and 11-61 (Fig. 8) with FR and WGA-HRP injection sites, respectively, were located toward the lower visual field representation and produced terminal label more medially.

Two patches of labeled axons within the lateral terminal zone of the pulvinar were not present for all cases. For instance in case 09-34, the FR label does form two patches, one ventrally and one dorsally (See Fig. 5 sections 163, 158, 148 for example); however the CTB terminal label formed only one continuous band of label (Fig. 5 sections 158, 148). The continuous band could reflect the large injection site, which covered almost the full rostral to caudal extent of the superior colliculus. Two patches, one ventral and one dorsal, were also present in case 10-51 (Fig. 6), but two terminal patches were less apparent in case 11-61 (Fig. 8) or 11-41 (Fig. 9). The difference between these cases is that the injection sites for cases with two clear patches were located rostrally within the superior colliculus, while the other cases had injection sites located caudally within the superior colliculus. This difference suggests that peripheral visual field representations may merge within the caudal aspect of the pulvinar. Finally, in case 10-51 (Fig. 6), CTB label was only present within the caudal pulvinar divisions that stain darkly for VGLUT2. No CTB terminal label was noticeable in the more rostral and lateral zones. As the superior colliculus injection in this case was the most superficial compared to all other cases where terminal label is observed, the results suggest that projections to the rostral lateral pulvinar may originate from deeper sublayers in the superior colliculus than those that project to the posterior pulvinar. The terminal patch within the medial aspect of the pulvinar (outside of the posterior pulvinar subdivisions) was often much smaller than patches observed more laterally (Figs. 5–9).

In none of the cases was terminal label observed within the medial pulvinar, as defined by CO and AChE staining. This observation is consistent with previous reports in galagos (Glendenning et al., 1975), as well as other primates (Stepniewska et al., 1999; Stepniewska et al., 2000).

In summary, topographic projections from the superior colliculus terminate within two caudal divisions of the pulvinar that stain darkly for VGLUT2 protein. One patch of labeled terminals was located medially within a region we define as Pp (or PIp of other primates), and the second patch was located ventrolaterally within a region we define as Ppc (possibly PIcm of other primates). At least two additional terminal patches of label were located in more rostrolateral locations to those observed within the VGLUT2 stained regions. Projections to the most lateral zone were retinotopically organized.

Other Connections

Our injections also revealed superior colliculus connections with the dorsal and ventral lateral geniculate nuclei, pretectum, parabigeminal nuclei, limitans, suprageniculate nucleus, and the substantia nigra. Projections from the superior colliculus to the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus were topographically organized, with more rostral superior colliculus injections resulting in terminal label located caudally within the dorsal lateral geniculate, while caudal injections resulted in terminal label more rostrally. Terminations were found both within K layers of the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus, as well as to intralaminar zones between MI and ME, and MI and PI. These results are similar to those of previous reports (Harting et al., 1986; Lachica and Casagrande, 1993). Bi-directional connections were also observed between the superior colliculus and the ipsilateral parabigeminal nucleus, as described previously (Diamond et al., 1992). The contralateral parabigeminal nucleus also sends projections to the superior colliculus, consistent with results described in squirrels (Holcombe and Hall, 1981; Baldwin et al., 2011), and anthropoid primates (Harting et al., 1980; Baizer and Whitney, 1991). Projection patterns to and from the parabigeminal nucleus were topographically organized, with more rostral superior colliculus injections terminating in more rostral locations of the parabigeminal nucleus compared to caudal injections as reported for other species (Sherk, 1979; Rodán et al., 1983; Baizer and Whitney, 1991). Connections were also observed between the superior colliculus and the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus, the nucleus limitans, pretectum, and substantia nigra, as previously reported in galagos (Glendenning 1975; Huerta et al., 1991; Diamond, 1992).

Discussion

In the present study, we compared connection patterns of the superior colliculus with architectural characteristics of the pulvinar complex of prosimian galagos. We determined that two, topographically organized projections from the superior colliculus terminate in two subdivisions of the pulvinar that express large amounts of the vesicular glutamate transporter VGLUT2. One such projection is to a larger medial division, which we tentatively name the posterior pulvinar (Pp), and the second projection is to a smaller division located more ventrolaterally, which we tentatively name the central posterior pulvinar (Ppc). Alternatively, perhaps with more evidence, these nuclei could be named after their proposed homologues in the inferior pulvinar of anthropoid primates; PIp for Pp and PIcm for Ppc.

The association between superior colliculus projections and VGLUT2 staining suggests that the use of VGLUT2 for synaptic transmission defines two pulvinar locations for superior colliculus terminations in galagos that can be similarly identified in other mammals. This possibility is supported by the expression of VGLUT2 mRNA in cells of the lower SGS in the colliculus (Balaram et al, 2011 and see Fig. 2), which are known to project to the inferior pulvinar in primates (Raczkowski and Diamond, 1981). Additionally, at least two likely topographically distributed projections terminate within more rostrolateral aspects of the pulvinar complex. These projections are to regions of the pulvinar that stain weakly for VGLUT2 protein, and are likely to be divisions within the inferior and (or) lateral pulvinar. Thus, projections from the superior colliculus to the pulvinar complex that do not depend on VGLUT2 for synaptic transmission also exist in galagos.

Other observed connections of the superior colliculus included those with the koniocellular and interlaminar layers of the lateral geniculate nucleius, the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus, nucleus limitans, parabigeminal nucleus, pretectum, and substantia nigra.

Previous reports on Galago pulvinar organization

Our present findings provide new insights on how the pulvinar complex is organized in mammals and how the complex pattern of pulvinar nuclei in anthropoid primates evolved. Histological staining procedures within the pulvinar complex of galagos have proven to be less robust and therefore less helpful in delineating subdivisions (Beck and Kaas, 1998; Wong et al., 2009) than they have been for anthropoid primates (Cusick et al., 1993; Gutierrez et al., 1995; Stepniewska and Kaas, 1997; Adams et al., 2000; Jones, 2007), making the assignment of homologues between prosimians and anthropoids difficult (Beck and Kaas, 1998; Wong et al., 2009).

Previous studies on the organization of the pulvinar complex in galagos used both anatomical markers, such as Nissl substance, cytochrome oxidase, and myelin, as well as differences in cortical and tectal connections to demarcate pulvinar subdivisions (Glendenning et al., 1975; Raczkowski and Diamond, 1980, 1981; Symonds and Kaas, 1978; Wall et al., 1982; Wong et al., 2009). Among the first studies, Glendenning et al, (1975) subdivided the pulvinar complex into inferior and superior divisions with the border between such divisions marked by the brachium of the superior colliculus. Glendenning observed that the caudal aspect of the pulvinar complex receives projections from the superior colliculus, mainly within their defined inferior pulvinar division, and few or no projections were found within the superior pulvinar division except after very large injections into the superior colliculus (see Fig. 11 section 84 of Glendenning et al., 1975 for example). Later Raczkowski and Diamond (1981) showed that injections into the superior pulvinar retrogradely labeled cells within the superficial layers of the superior colliculus (Figs. 11, and 13 of Raczkowski and Diamond, 1981). Finally, further evidence provided by Diamond et al. (1992), showed that the superior colliculus projects most densely to the caudal half the pulvinar complex, but also more rostrally, even into the classically defined superior pulvinar division above the brachium of the superior colliculus (See Fig. 5 of Diamond et al., 1992). In our current study, we also found terminal label above the brachium of the superior colliculus.

Other studies in galagos suggested that the superior pulvinar can be divided into a medial pulvinar (PM) and a lateral pulvinar (PL) based on differences in cortical connections with visual structures, such that PM does not share many connections with visual cortical areas while PL does (Symonds and Kaas, 1979; Wall et al., 1982; Wong and Kaas, 2008). We found that the superior colliculus projects only within the lateral half of the classically defined superior pulvinar, and this termination zone is likely PL. However, this terminal zone could also be within a subdivision of the inferior pulvinar that traverses the brachium of the superior colliculus. This lateral terminal zone appears to be topographically organized, similar to descriptions of the lateral pulvinar (superior pulvinar) of Symonds and Kaas (1978), with upper visual field represented laterally and the lower visual field represented medially. The terminal label zone from any given injection site in the superior colliculus reveals a band of isoecentricity that shifts slightly through the rostrocaudal extent of the pulvinar complex, similar to descriptions by Symonds and Kaas (1978). In many reports (Symonds and Kaas, 1978; Wall et al., 1982), the peripheral visual field was suggested to be represented ventrally and dorsally, while the central visual field was suggested to be represented centrally within the lateral aspect of the pulvinar. While it was difficult for us to confirm this type of topography in our present study, our results were largely consistent with this interpretation. For example, in case 09-34 (Fig. 5), an injection site (CTB) extending more caudally within the superior colliculus resulted in terminal label that was located more centrally within the lateral pulvinar than the terminal label from a more rostral superior colliculus injection (FR).

As in previous reports in galagos (Glendenning et al., 1975; Diamond et al., 1992; Wong et al., 2009), we did not find terminal label within the rostral part of the medial pulvinar. However, caudally, portions of our Pp cross the brachium dorsally into the territory of the classically defined superior pulvinar, a region more recently defined as the medial pulvinar (Wong et al., 2009). We did see terminal label in this more dorsomedial location, but only co-localized within our darkly staining VGLUT2 region of the caudal pulvinar within Pp. Rather than being part of the medial pulvinar, comparisons with anthropoid primates indicate that Pp is part of the inferior pulvinar (PIp).

The inferior pulvinar of galagos, as described by Glendenning et al. (1975), has been subsequently divided into three domains based on cortical and tectal connections. A large central inferior pulvinar (IPc) located laterally, a medial inferior pulvinar (IPm) located medially, and a posterior pulvinar (IPp) located at the most posterior end of the pulvinar complex. Both IPc and IPm have connections with striate and extrastriate cortical areas (Symonds and Kaas, 1978; Wall et al., 1982; Wong et al., 2009), while IPp receives projections from the superior colliculus but has few connections with striate cortex (Glendenning et al., 1975; Symonds and Kaas, 1978; Diamond et al., 1992; Wong et al., 2009). We confirm that there are dense projections to the caudal portion of the pulvinar as described by Glendenning et al., 1975, Diamond et al., 1992, and Wong et al., 2009, but, for the first time we are able to anatomically define the caudal tectal termination zone using VGLUT2 staining procedures. We also propose that this zone includes two separate subdivisions, which we call the posterior pulvinar (Pp) and the posterior central pulvinar (Ppc). Additionally, we found that Pp is not confined to the classically defined region of the inferior pulvinar, which lies below the brachium of the superior colliculus, but extends both above and below the brachium (See Fig. 5 sections 163 and 158, Fig. 6 section 143). In anthropoid primates, the results of recent studies indicate that several subdivisions of the inferior pulvinar also extend above the brachium of the superior colliculus (e.g. Stepniewska and Kaas, 1997).

PIm of galagos, as described by Symonds and Kaas (1978), and Wong et al., 2009, is located medially within the classically defined inferior pulvinar. In all cases in the present study, a patch of terminal label was located medially, but outside of the VGLUT2 densely staining posterior pulvinar. Likely this projection is to PIm as described previously in galagos. This division of the inferior pulvinar of galagos could correspond to PIm of anthropoid primates.

In summary, the pulvinar complex of galagos has more subdivisions than previously reported. Although the classically defined inferior pulvinar of galagos has been located below the brachium of the superior colliculus, the present study provides evidence that the inferior pulvinar does traverse above the brachium, with Pp extending more dorsally than subdivisions of the inferior pulvinar in anthropoid primates. This more dorsal location suggests a rotational shift in the location of subdivisions of the inferior pulvinar occurred in anthropoid primates from the pulvinar complex of galagos and other mammals (see below), making homologous nuclei more difficult to identify.

Comparisons with other Euarchontoglires species

The Euarchontoglires clade of placental mammals includes a number of species whose pulvinar organization has been well studied, including New and Old World monkeys, rodents, and tree shrews. Part of our goal in the current study was to compare the organization of the pulvinar complex in galagos and other members of the Euarchotoglire clade in order to reveal common features and specializations. Here we first describe the pulvinar organization in galagos and other primates, and then focus on the pulvinar organization in squirrels and tree shrews, non-primate members of the Euarchontoglires clade.

Pulvinar organization in primates

Pulvinar organization in primates is largely understood from the results of experimental studies in New and Old World monkeys (Fig. 10D). Early studies divided the inferior pulvinar (PI) into three nuclei, a posterior nucleus, PIp, and a “central” inferior nucleus, PIc with inputs from the superior colliculus (Mathers, 1971; Lin and Kaas, 1979), and a medial inferior nucleus, PIm, with few, if any, inputs from the superior colliculus (Lin and Kaas, 1979, 1980). On the basis of marked architectonic differences, especially for brain sections processed for AChE, PIc has been subsequently divided into a smaller medial nucleus, PIcm, and a larger lateral nucleus, PIcl (Stepniewska et al., 1997). The lateral pulvinar, PL, extends ventrally along the lateral border of PIcl (See Fig. 10D). Both PIcl and PL project topographically to V1 and V2 (Adams et al, 2000; Kennedy and Bullier, 1985), while PIp, PIm, and PIcm all project to temporal cortex in the MT complex, MT, MST, MTc, and FST (See Kaas and Lyon, 2007 for review). PIcl and PL appear to contain the two large retinotopically organized representations of the contralateral visual hemifield that have been previously described (Allman and Kaas, 1972; Gattas et al, 1978; Bender, 1981; Ungerleider et al., 1983; Shipp, 2001). There may be other, less precise retinotopic representations in PIcm, PIm, and PIp, but this is not well established. The medial pulvinar, PM, is distinguished by projections to a number of non-visual as well as visual cortical regions (see Stepniewska, 2004; Jones, 2007 for review).

Figure 10.

Organization schemes of the pulvinar complex with superior colliculus (SC) inputs and VGLUT2 staining patterns for various members of the Euarchontoglires clade. A. Gray squirrels, based on descriptions from Baldwin et al., 2011. C is the caudal pulvinar, RLm is the rostral lateral medial pulvinar, RLl is the rostral lateral lateral pulvinar, RM is the rostral medial pulivnar and LGNd is the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. B. Tree shrews based on descriptions of Luppino et al., 1988, Lyon et al., 2003a, and Chomsung et al., 2008. Pd is the dorsal pulvinar, Pc is the central pulvinar, and Pv is the ventral pulvinar. C. Proposed organization of the pulvinar complex in galagos. D. Anthropoid primates based on descriptions in Stepniewska et al., 1999, and Stepniewska et al., 2000. PM is the medial pulvinar, PL is the lateral pulvinar, PIp is the posterior inferior pulivnar, PIm is the medial inferior pulvinar, PIcm is the central medial inferior pulvinar, PIcl is the central lateral inferior pulvinar. VGLUT2 staining for D is based on unpublished data.

Our current interpretation of the relationship of the pulvinar subdivisions in galagos to those proposed in monkeys is that the large VGLUT2 positive region, Pp, in galagos is homologous to PIp of monkeys. Both regions occupy the most medial portion of the inferior pulvinar, while extending above the brachium of the superior colliculus into the traditional territory of the medial pulvinar (Stepniewska et al., 1997). Both regions receive dense inputs from the superior colliculus, and project to temporal visual cortex largely around MT (Kaas and Lyon, 2002; Wong et al, 2009). A major difference is that Pp extends into a more caudodorsal position in galagos, displacing PM laterally. The smaller Ppc region in galagos is similar to PIcm of monkeys in having superior colliculus inputs, and having a more lateral location within the medial aspect of the inferior pulvinar than Pp/PIp with a possible ‘fusion zone’ linking Pp/PIp and Ppc/PIcm (Stepniewska et al., 1999). Ppc may be a displaced part of Pp, or the homolog of PIcm of monkeys. If so, PIm of monkeys may occupy the small space, seen in some brain sections, between Pp and Ppc in galagos, or in tissue rostral to Ppc, or be poorly differentiated or absent. Much of the Pp-Ppc regions project to the MT complex and other temporal visual areas in galagos (Glendenning et al., 1975; Raczkowski and Diamond, 1980; Wong et al., 2009). More lateral parts of the pulvinar complex in galagos (PI and PL) that project topographically to V1 (Symonds and Kaas, 1978; Wong et al., 2009), forming two adjoining topographic maps, likely corresponding to PL and PIcl of monkeys. Previous reports on New World monkeys have shown projections from the superior colliculus to PIcl and even PL (Stepniewska et al., 1999; 2000). However, in Old World monkeys only minor projections from the superior colliculus to PIcl and the most lateral aspect of PL have been reported (Stepniewska et al., 2000; Lyon et al., 2010). Therefore, projections from the superior colliculus to PIcl and PL divisions of the pulvinar could have been present within early primates, but are reduced in Old World monkeys.

A smaller dorsomedial region, PM, in galagos resembles PM of monkeys, but corresponding connections have not been reported.

Pulvinar organization in other mammals and homologies with primates

Our present view of pulvinar organization in galagos, given the differences in the arrangement of the inferior pulvinar nuclei from those in monkeys, invites further comparisons with non-primate mammals. Such a comparison is complicated by the early view that the pulvinar is a structure found only in primates, and the resulting tendency of subsequent investigators to refer to all or much of the pulvinar in non-primates as the lateral posterior nucleus or nuclei (see Kaas, 2007 and Jones, 2007 for review). More recently, it has become apparent that all mammals have a part of the visual thalamus with inputs from the superior colliculus and connections with visual cortex that can be reasonably called the pulvinar, but subdivisions homologous to those of the pulvinar in primates have been difficult to identify (Jones et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2009; Manger et al., 2010; Baldwin et al., 2011). Here we consider the subdivisions of the pulvinar in two highly visual mammals of the Euarchontoglires clade, tree shrews and gray squirrels. Tree shrews (Scandentia) are of special interest as they are the closest living relatives of primates that have been studied (Kaas, 2002; Kaas, 2005). Squirrels and other rodents are also of great interest, as rodents constitute one of the major branches of the Euarchontoglires radiation (Murphy et al., 2001; Meredith et al., 2011).

In both squirrels and tree shrews, a caudal part of the pulvinar, known as the caudal pulvinar (C) in squirrels (Fig. 10A) and the dorsal pulvinar (Pd) in tree shrews (Fig. 10B), gets diffuse inputs from the superior colliculus and project to temporal visual cortex (Robson and Hall, 1977; Lyon et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2008; Chomsung et al., 2010). Both C and Pd stain darkly for AChE and for VGLUT2 (Lyon et al., 2003; Chomsung et al., 2008; Baldwin et al., 2011), and its dorsomedial position at the caudal pole of the pulvinar is in a location more similar to Pp in galagos than PIp in monkeys. We propose that the C nucleus in squirrels, Pd in tree shrews, Pp in galagos, and PIp in monkeys are homologous, but somewhat differently displaced, especially by the enlarged medial and lateral divisions of the pulvinar in monkeys and other anthropoid primates. Other mammals have a darkly staining AChE zone with superior colliculus inputs and projections to temporal visual cortex, as has been well studied in cats (Graybiel and Berson, 1980; Abramson and Chalupa, 1988; Berson and Graybiel, 1991; Hutsler and Chalupa, 1991). A homologous pulvinar nucleus may exist in all mammals, and even in reptiles and birds (see Fredes et al., 2012 for review).

A significant difference between the pulvinar complex of galagos and that of many non-primates is that, in diurnal rodents (Robson and Hall, 1977; Kuljis and Fernandez, 1982; Baldwin et al., 2010; Fredes et al., 2012), other diurnal mammals (Luppino et al., 1988), and even birds (Karten et al., 1997; Marin et al., 2003), the caudal nucleus receives inputs from both the ipsilateral and contralateral superior colliculus, while only the ipsilateral superior colliculus projections to the pulvinar were observed in galagos. This difference could reflect a specialization of the superior colliculus in primates where each colliculus represents only the contralateral visual hemifield from both eyes (Lane et al., 1973; Kaas and Preuss, 1993; May, 2006), while the complete retina of the contralateral eye is represented in the superior colliculus of non-primate mammals (Lane et al., 1971; Kaas, 2002; Kaas et al., 1974; May, 2006). However, some reports in macaque monkeys have described bilateral projections to the inferior pulvinar (Benevento and Rezak, 1976; Trojanowski and Jacobson, 1975). Additionally, reports on nocturnal rodents (Donnelly et al., 1983; Cadusseau and Roger, 1985; Masterson et al., 2009), and rabbits (Graham and Berman, 1981) have reported a lack of contralateral tectal projections to the pulvinar complex. Therefore more studies are needed to further document those mammals with bilateral projections to the pulvinar and those with only ipsilateral projections. It will also be useful to determine if the contralateral projections to the pulvinar in non-primates arise from the rostral part of the superior colliculus, where the ipsilateral hemifield is represented.

We also suggest that Ppc in galagos is homologous with PIcm of monkeys. Alternatively, Ppc and Pp of galagos correspond with PIp of monkeys. Likewise, the caudal nucleus of squirrels and the dorsal pulvinar of tree shrews may correspond only to Pp of galagos, or both Pp and Pc. Other homologies are less certain. The larger retinotopically organized nuclei that project to V1 and V2, RM and RL in squirrels and Pc and Pv in tree shrews, are likely homologous with PIcl and PL of primates with RL of squirrels and Pc in tree shrews most likely corresponding to PIcl. Thus, as many as four subdivisions of the visual pulvinar may have emerged in early stages of mammalian evolution.

Origins of the tectopulvinar pathway within the superior colliculus

Recently, Fredes et al., (2012) have revealed differences in the laminar origin of the tectal projections to the pulvinar in squirrels. Cells that project to the caudal pulvinar originate in the lower SGS, while projections to the rostral divisions of the pulvinar originate to in the upper SO of the superior colliculus. In our current study, we did not isolate injections within the SGS or the SO. However, recent insitu experiments conducted of Balaram et al. (2011) indicate that cells within the lower SGS of galagos express VGLUT2 mRNA, while cells within the SO do not. Thus, it is likely that the projections to the caudal divisions of the pulvinar originate from the SGS cells that express VGLUT2 mRNA. We are uncertain as to where the superior colliculus projections to more rostral locations in the pulvinar originate, but such projections could likely be from the upper SO, as the case with the more superficial injection in the superior colliculus (10-51: Fig. 6) showed dense projections to the caudal pulvinar but not to more rostral and lateral subdivisions. In addition, these rostral projections do not coincide with strong VGLUT2 staining, and cells within the SO of the superior colliculus do not express VGLUT2 mRNA. Previous reports in galagos have shown that only cells within the lower SGS (Raczkowski and Diamond, 1981) and cells bordering the SGS and SO (Diamond et al., 1992) project to the pulvinar complex. However, since only a percentage of cells in the lower SGS express VGLUT2 mRNA, projections to the rostral divisions of the pulvinar could also originate from cells within the lower SGS that do not utilize VGLUT2.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute, RO1 EY-02686 (J.H.K), and CORE grants P30 EY-008126.

We thank Omar Gharbawie, Peiyan Wong, Nicole Young, and Mary Feurtado for surgical assistance, Laura Trice for tissue processing, and Iwona Stepniewska for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest

Role of Authors

MKLB was involved in experimental design, collecting and analyzing the data, and writing the manuscript. PB was involved in collecting and analyzing the data, and writing the manuscript. JHK was involved in designing the experiment, analyzing data, and writing the manuscript.

References

- Abramson BP, Chalupa LM. Multiple pathways from the superior colliculus to the extrageniculate visual thalamus of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1988;271:397–418. doi: 10.1002/cne.902710308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MM, Patrick RH, Gattass R, Webster MJ, Ungerleider LG. Visual cortical projections and chemoarchitecture of macaque monkey pulvinar. J Comp Neurol. 2000;419:377–393. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000410)419:3<377::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman JM, Kaas JH, Lane RH, Miezin FM. A representation of the visual field in the inferior nucleus of the pulvinar in the owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus) Brain Res. 1972;40:291–302. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atencio FW, Diamond IT, Ward JP. Behavioral study of the visual cortex of galago senegalensis. J Comp Neurol. 1975;89:1109–35. doi: 10.1037/h0077180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaram P, Takahata T, Kaas JH. VGLUT2 mRNA and protein expression in the visual thalamus and midbrain of prosimian galagos (Otolemur garnetti) Eye and Brain. 2011;3:5–15. doi: 10.2147/EB.S16998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin MKL, Wong PY, Reed JL, Kaas JH. Superior colliculus connections within visual thalamus in gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis): Evidence for four subdivisions within the pulvinar complex. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:1071–1094. doi: 10.1002/cne.22552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin MKL, Kaskan PM, Zhang B, Chino YM, Kaas JH. Cortical and subcortical connections of V1 and V2 in early postnatal macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:544–569. doi: 10.1002/cne.22732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin MKL, Kaas JH. Cortical projections to the superior colliculus in prosimian galagos (Otolemur garnetti) J Comp Neurol E Pub Dec. 2012;15:2011. doi: 10.1002/cne.23025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baizer JS, Whitney JF. Bilateral projections from the parabigeminal nucleus to the superior colliculus in monkey. Exp Brain Res. 1991;86:467–470. doi: 10.1007/BF00230521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck PD, Kaas JH. Thalamic connections of the dorsal medial area in primates. J Comp Neurol. 1998;396:381–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender DB. Retinotopic organization of macaque pulvinar. J Neurophysiol. 1981;46:682–93. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.46.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benevento LA, Rezak M. The cortical projections of the inferior pulvinar and adjacent lateral pulvinar in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta): an autoradiographic study. Brain Res. 1976;108:1–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson DM, Graybiel AM. Tectorecipient zone of cat lateral posterior nucleus: evidence that collicular afferents contain acetylcholinesterase. Exp Brain Res. 1991;84:478–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00230959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande VA, Diamond IT. Ablation study of the superior colliculus in the tree shrew (Tupaia glis) J Comp Neurol. 1974;156:207–37. doi: 10.1002/cne.901560206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsung RD, Petry HM, Bickford ME. Ultrastructural examination of diffuse and specific tectopulvinar projections in the tree shrew. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:24–46. doi: 10.1002/cne.21763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsung RD, Wei H, Day-Brown JD, Petry HM, Bickford ME. Synaptic organization of connections between temporal cortex and pulvinar nucleus of the tree shrew. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:997–1011. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain BJ, Hall WC. The normal organization of the lateral posterior nucleus of the golden hamster. J Comp Neurol. 1980;193:351–370. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick CG, Scripter JL, Darensbourg JG, Weber JT. Chemoarchitectonic subdivisions of the pulvinar in monkeys and their connections with the middle temporal and rostral dorsolateral visual areas, MT and DLr. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:1–30. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond IT. The evolution of the tecto-pulvinar systems in mammals: Structural and behavioral studies in the visual system. Symp Zool Soc Lond. 1973;33:205–233. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond IT. Organization of visual cortex: comparative anatomical and behavioral studies. Fed Proc. 1976;35:60–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond IT, Fitzpatrick D, Conley M. A projection from the parabigeminal nucleus to the pulvinar nucleus in galago. J Comp Neurol. 1992;316:375–382. doi: 10.1002/cne.903160308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredes F, Vega-Zuniga T, Karten H, Mpodozis J. Bilateral and ipsilateral ascending tecto-pulvinar pathways in mammals: A study in squirrel (Spermophilus beecheyi) J Comp Neurol. doi: 10.1002/cne.23014. In press. E. Pub. Nov 25th 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattass R, Oswaldo-Cruz E, Sousa AP. Visuotopic organization of the cebus pulvinar: a double representation the contralateral hemifield. Brain Res. 1978;152:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geneser-Jensen FA, Blackstad TW. Distribution of acetylcholinesterase in the hippocampal region of the guinea pig. I. Entorhinal area, parasubiculum, and presubiculum. Z Zelforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1971;114:460–481. doi: 10.1007/BF00325634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharbawie OA, Stepniewska I, Burish MJ, Kaas JH. Thalamocortical connections of functional zones in posterior parietal cortex and frontal cortex motor regions in New World monkeys. Cereb Cortex. 2010;10:2391–410. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendenning KK, Hall JA, Diamond IT, Hall WC. The pulvinar nucleus of Galago senegalensis. J Comp Neurol. 1975;161:419–458. doi: 10.1002/cne.901610309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM, Berson DM. Histochemical identifications and afferent connections of subdivisions in the lateralis posterior-pulvinar complex and related thalamic nuclei in the cat. Neuroscience. 1980;5:1175–1238. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez C, Yaun A, Cusick CG. Neurochemical subdivisions of the inferior pulvinar in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1995;363:545–562. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett TA, Takahata T, Balaram P. VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 mRNA expression in the primate auditory pathway. Hear Res. 2011;274:129–41. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting JK, Glendenning KK, Diamond IT, Hall WC. Evolution of the primate visual system: Anterograde degeneration studies of the tecto-pulvinar system. Am J Phys Anthrop. 1973;38:383–392. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330380237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting JK, Casagrande VA, Weber JT. The projections of the primate superior colliculus upon the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus: autoradiographic demonstration of interlaminar distribution of tectogeniculate axons. Brain Res. 1978;150:593–599. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90822-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting JK, Huerta M, Frankfurter AJ, Strominger NL, Royce GJ. Ascending pathways from the monkey superior colliculus. An autoradiographic analysis. J Comp Neurol. 1980;192:853–882. doi: 10.1002/cne.901920414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting JK, Hashikawa T, van Lieshout D. Laminar distribution of tectal, parabigeminal and pretectal inputs to the primate dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus: connectional studies in Galago crassicudatus. Brain Res. 1986;366:358–363. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Gras C, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Bedet C, Gasnier B, Giros B, Mestikawy SE. The existence of a second vesicular glutamate transporter specifies subpopulations of glutamatergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcombe V, Hall WC. Course and laminar origin of the tectoparabigeminal pathway. Brain Res. 1981;211:405–411. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta MF, Van Lieshout DP, Hartin JK. Nigrotectal projections in the primate Galago crassicaudatus. Brain Res. 1991;87:389–401. doi: 10.1007/BF00231856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutsler JJ, Chalupa LM. Substance P immunoreactivity identifies a projection from the cat’s superior colliculus to the principal tectorecipient zone of the lateral posterior nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1991;312:379–390. doi: 10.1002/cne.903120306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. The thalamus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. Convergences in the modular and areal organization of the forebrain of mammals: implications for the reconstruction of forebrain evolution. Brain Behav Evol. 2002;59B:262–272. doi: 10.1159/000063563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. The evolution of the visual system in primates. In: Chaplupa LM, Werner JS, editors. The Visual Neurosciencees. Vol. 2. MIT Press; 2004. pp. 1563–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. From mice to men: the evolution of the large, complex human brain. J Biosci. 2005;30:155–165. doi: 10.1007/BF02703695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. The evolution of sensory and motor systems in primates. In: Kaas, editor. The Evolution of the Nervous system. Elsevier Inc; London: 2007a. pp. 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. The evolution of dorsal thalamus in mammals. In: Kaas JH, editor. Evolutionary neuroscience. New York: Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Harting JK, Guillery RW. Representation of the complete retina in the contralateral superior colliculus of some mammals. Brain Res. 1974;65:343–346. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Huerta MF. The subcortical system of primates. In: Steklis HD, editor. Comparative primate biology. New York: Wiley:Liss; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Preuss TM. Archontan affinities as reflected in the visual system. In: Szalay, et al., editors. Mammal Phylogeny; Placentals. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Collins CE. Variability in sizes of brain parts. Behav Brain Sci. 2001;24:288–290. [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Lyon DC. Pulvinar contributions to the dorsal and ventral streams of visual processing in primates. Brain Res Rev. 2007;55:285, 96. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karten HJ, Cox K, Mpodozis J. Two distinct populations of tectal neurons have unique connections within the retinotectorotundal pathway of the pigeon (Columba livia) J Comp Neurol. 1997;387:449–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy H, Bullier J. A double-labeling investigation of the afferent connectivity to cortical areas V1 and V2 of the macaque monkey. J Neurosci. 1985;5:2815–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-10-02815.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuljis RO, Fernandez V. On the orgnization of the retino-tecto-thalamo-telencephalic pathways in the Chilean rodent; the Octodon degus. Brain Res. 1982;234:189–204. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90861-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachica EA, Casagrande VA. The morphology of collicular and retinal ending on small relay (W-like) cells of the primate lateral geniculate nucleus. Vis Neurosci. 1993;10:403–418. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800004648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane RH, Allman JM, Kaas JH. Representation of the visual field in the superior colliculus of gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinesis) and tree shrew (Tupaia glis) Brain Res. 1971;26:277–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane RH, Allman JM, Kaas JH, Miezin FM. The visuotopic organization of the superior colliculus of the owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus) and the bush baby (Galago senegalensis) Brain Res. 1973;60:335–49. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey NH, Harris J, Jane JA. Effects of visual cortical ablation on pattern discrimination in the ground squirrel (Citellus tridecemlineatus) Exp Neurol. 1973;39:270–276. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(73)90229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CS, Kaas JH. The inferior pulvinar complex in owl monkeys: architectonic subdivisions and patterns of input from the superior colliculus and subdivisions of visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1979;187:655–678. doi: 10.1002/cne.901870403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CS, Kaas JH. Projections from the medial nucleus of the interior pulvinar complex to the middle temporal area of visual cortex. Neurosci. 1980;5:2219–2228. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling C, Schneider GE, Northmore D, Jhaveri S. Afferents from the colliculus, cortex, and retina have distinct terminal morphologies in the lateral posterior thalamic nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:467–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppino G, Matelli M, Carey RG, Fitzpatrick D, Diamond IT. New view of the organization of the pulvinar nucleus in Tupaia as revealed by tectopulvinar and pulvinar-cortical projections. J Comp Neurol. 1988;273:67–86. doi: 10.1002/cne.902730107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon DC, Jain N, Kaas JH. The visual pulvinar in tree shrews II. Projections of four nuclei to areas of visual cortex. 2003;467:607–627. doi: 10.1002/cne.10940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon DC, Nassi JJ, Callaway EM. A disynaptic relay from superior colliculus to dorsal stream visual cortex in macaque monkey. Neuron. 2010;65:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte RR, Ward JP. Preoperative overtraining protects against form learning deficits after lateral occipital lesions in galago senegalensis. J Comp Neurol. 1980;84:305–12. doi: 10.1037/h0077671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manger PR, Restrepo CE, Innocenti GM. The superior colliculus of the ferret: cortical afferents and efferent connections to dorsal thalamus. Brain Res. 1353:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers LH. Tectal projections to the posterior thalamus of the squirrel monkey. Brain Res. 1971;35:295–298. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PJ. The mammalian superior colliculus: laminar structure and connections. Prog Brain Res. 2006;151:321–378. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)51011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith RW, Janĕcka JE, Gatesy J, Ryder OA, Fisher CA, Teeling EC, Goodbla A, Elzirik E, Simão TL, Stadler T, Rabosky DL, Honeycutt RL, Flynn JJ, Ingram CM, Steiner C, Williams TL, Robinson TJ, Burk-Herrick A, Westerman M, Ayoub NA, Springer MS, Murphy WJ. Impacts of the cretaceous terrestrial revolution and KPg extinction on mammal diversification. Science. 2011;334:521–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1211028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MD, Howerth EW, MacLachlan NJ, Stalknect DE. Resolution of the early placental mammal radiation using Bayesian phylogenetics. Science. 2001;294:2348–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1067179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons TP, Kaas JH. Connections of area 2 of somatosensory cortex with the anterior pulvinar and subdivisions of the ventroposterior complex in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1985;240:16–36. doi: 10.1002/cne.902400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppel E, Held R, Frost D. Leter: residual visual function after brain wounds involving the central visual pathway in man. Nature. 1973;243:295–296. doi: 10.1038/243295a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raczkoweski D, Diamond IT. Cortical projections of the pulvinar nucleus in galago. J Comp Neurol. 1980;193:1–40. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raczkoweski D, Diamond IT. Projections from the superior colliculus and neocortex to the pulvinar nucleus in galago. J Comp Neurol. 1981;200:231–54. doi: 10.1002/cne.902000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radinsky L. Primate brain evolution. Am Sci. 1975;36:656–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson JA, Hall WC. The organization of the pulvinar in the grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). I. Cytoarchitecture and connections. J Comp Neurol. 1977;173:355–388. doi: 10.1002/cne.901730210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodán M, Reinsoso-Suárez F, Tortelly A. Parabigeminal projections to the superior colliculus in the cat. Brain Res. 1983;280:1–3. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherk H. Connections and visual-field mapping in cat’s tectoparabigeminal circuit. J Neurophysiol. 1979;42:1656–1668. doi: 10.1152/jn.1979.42.6.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipp S. Corticopulvinar connections of area V5, V4, and V3 in the macaque monkey: a dual model of retinal and cortical topographies. J Comp Neurol. 2001;439:469–90. doi: 10.1002/cne.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepniewska I. The pulvinar complex. In: Kaas JH, Collins CE, editors. The primate visual system. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2004. pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Stepniewska I, Kaas JH. Architectonic subdivisions of the inferior pulvinar in New World and Old World monkeys. Vis Neurosci. 1997;14:1043–60. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800011767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepniewska I, Qi HX, Kaas JH. Do superior colliculus projection zones in the inferior pulvinar project to MT in primates? Eur J Neurosci. 1999;2:469–480. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepniewska I, Qi HX, Kaas JH. Projections of the superior colliculus to subdivisions of the inferior pulvinar in New World and Old World monkeys. Vis Neurosci. 2000;17:529–49. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800174048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoerig P, Cowey A. Blindsight. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R822–R824. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symonds LL, Kaas JH. Connections of striate cortex in the prosimian, Galago senegalensis. J Comp Neurol. 1978;181:477–512. doi: 10.1002/cne.901810304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symonds LL, Rosenquist AC, Edwards SB, Palmer LA. Projections of the pulvinar-lateralis posterior complex to visual cortical areas in the cat. Neursci. 1981;6:1995–2020. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(81)90039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. The organization of the lateral thalamus of the hooded rat. J Comp Neurol. 1985;281:281–309. doi: 10.1002/cne.902310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamietto M, Cauda F, Corazzini LL, Savazzi S, Marzi CA, Goebel R, Weiskrantz L, de Gelder B. Collicular vision guides nonconscious behavior. J Comp Neurosci. 2010;22:888–920. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider LG, Galkin TW, Mishkin M. Visuotopic organization of projections from striate cortex to inferior and lateral pulvinar in rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1983;217:137–57. doi: 10.1002/cne.902170203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagor E. Pattern vision in the grey squirrel after visual cortex ablation. Behav Biol. 1978;22:1–22. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(78)91959-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]