Abstract

Aims:

It is common knowledge that proteus bacteria are associated with urinary tract infections and urinary stones. Far more interesting however, is the derivation of the word proteus. This study examines the origin of the word proteus, its mythological, historical and literary connections and evolution to present-day usage.

Materials and Methods:

A detailed search for primary and secondary sources was undertaken using the library and internet.

Results:

Greek mythology describes Proteus as an early sea-god, noted for being versatile and capable of assuming many different forms. In the 8th century BC, the ancient Greek poet, Homer, famous for his epic poems the Iliad and Odyssey, describes Proteus as a prophetic old sea-god, and herdsman of the seals of Poseidon, God of the Sea. Shakespeare re-introduced Proteus into English literature, in the 15th century AD, in the comedy The Two Gentleman of Verona, as one of his main characters who is inconstant with his affections. The ‘elephant man’ was afflicted by a severely disfiguring disease, described as ‘Proteus syndrome’. It is particularly difficult to distinguish from neurofibromatosis, due to its various forms in different individuals. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word ‘protean’ as to mean changeable, variable, and existing in multiple forms. Proteus bacteria directly derive their name from the Sea God, due to their rapid swarming growth and motility on agar plates. They demonstrate versatility by secreting enzymes, which allow them to evade the host's defense systems.

Conclusions:

Thus proteus, true to its name, has had a myriad of connotations over the centuries.

Keywords: Etymology, history of medicine, mythology, proteus, urinary tract infection

INTRODUCTION

Proteus bacteria are well known to be associated with urinary tract infections and stone formation. Less well known, however, is the etymology of the word proteus. This study examines the origin of the word proteus which dates back to mythological times. The word has many historical and literary connections and this article aims to describe the evolution of the nomenclature from 800 BC to its present-day usage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A search for primary and secondary sources was undertaken using the library and internet. We contacted professors of Greek and Latin mythology at the University College London (UCL), who provided valuable resources. The curator at the British Museum, London, was approached and provided images of items of archeological interest.

RESULTS

Greek mythology

Proteus was first discovered by Gustav Hauser [Figure 1], a German pathologist, in 1885.[1] Accounting for more than 90% of proteus infections, Proteus mirabilis is a highly motile Gram-negative bacterium.[2] The ability of Proteus mirabilis to differentiate from short vegetative swimmer cells to an elongated, highly flagellated swarmer form is a distinctive feature of this organism, originally noted by Hauser in 1885.[3] It has a swarming growth and adhesion factors which make it extremely sticky and motile. The success of Proteus mirabilis as a bacteria is based upon its ability to evade the host's immune system and avoid capture.

Figure 1.

Gustav Hauser (German pathologist) [Image obtained from Wikipedia – Available at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Gustav_Hauser]

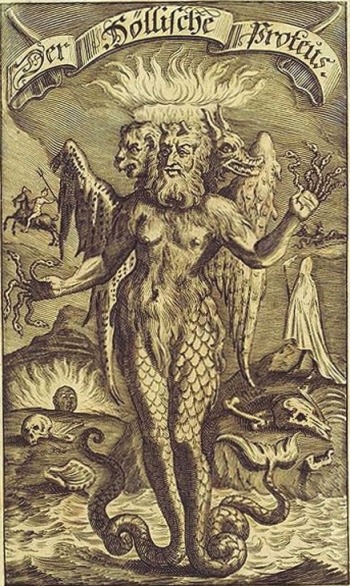

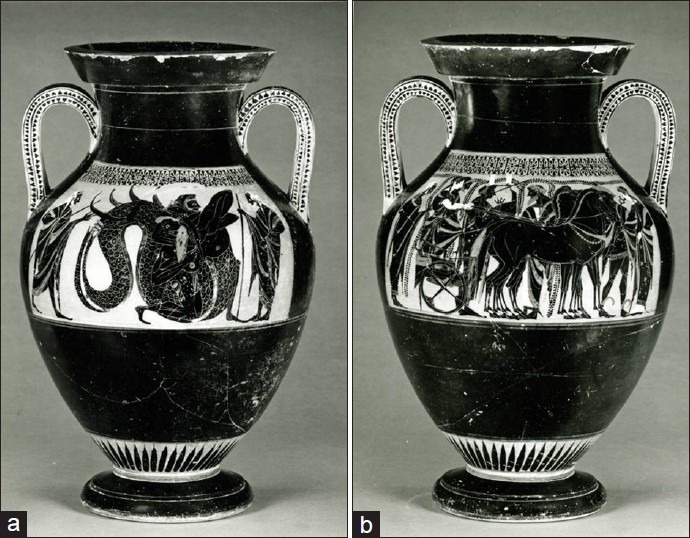

Gustav Hauser obtained his inspiration for the name Proteus from the epic tale Odyssey written by the famous Greek poet Homer in the 8thc entury BC. The story begins on the island of Pharos, which lies at the north coast of Egypt, near Alexandria, and it was here that the famous lighthouse at Pharos once stood, one of the Ancient Wonders of the World. It was on the island of Pharos that Proteus [Figures 2 and 3], the sea god, lived. Proteus had the ability to change shape and form to avoid capture by his enemy, hence the name given to the bacteria. He was recognised as Poseidon's herdsman of the seals. Figure 4 shows one of the earliest depictions of Proteus, found on an archaic black figure amphora, which was made in Athens 520 BC. (The digital images were obtained courtesy of the Curator at the British Museum, London.)

Figure 2.

Sixteenth-century woodcut of Proteus, the Sea God [Image obtained from Wikipedia – Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Proteus-Alciato.gif]

Figure 3.

Seventeenth-century German image of Proteus, the Sea God [Image obtained from Wikipedia – Available at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Hoellischer_Proteus.jpg]

Figure 4a and b.

One of the earliest depictions of Proteus, found on an archaic black figure amphora, made in Athens, 520 BC (The digital images were obtained courtesy of the Curator at the British Museum, London)

Proteus was the son of the Great Sea God, Poseidon, master of the seas. And an encounter between Menelaus and Proteus is particularly interesting. Menelaus was a Trojan warrior looking to return from Troy, however, the winds were so fierce he was unable to get his ship back out onto the seas.

He met a sea nymph, Eidothea, daughter of Proteus, who took pity upon him and he asked her “Goddess, whoever you may be, I must have offended the Gods and why have they thwarted my journey?”

Eidothea answered: “If you can ambush and capture Proteus, the ancient sea god, he will give you your answer. He will seek to foil you by taking the shape of every creature that moves on earth, and of water and of portentous fire; but you must hold him unflinchingly”. So Menelaus hid in wait on a beach where he knew Proteus would arrive to come and count his seals. Soon enough Proteus arrived and Menelaus pounced and attacked Proteus. Proteus, true to his name, changed his form from a bearded lion, to a snake, a panther, a monstrous boar and even running water, and then to a leafy tree. Menelaus held on undismayed and Proteus eventually tired, at which point Proteus spoke, “What is it that you want from me?” Menelaus replied, “What have I done to offend the Gods?” Proteus answered, “you must make choice offerings to Zeus to reach your own country soonest over the wine-dark sea”. Menelaus followed Proteus’ instructions and soon returned home.[4–6]

Literature

Moving to the 15th century AD, William Shakespeare named one of his main characters Proteus, in the play, The Two Gentleman Of Verona. The great bard chose the name Proteus because the character was of changeable affection. At the start of the play, Proteus is initially in love with Julia. His best friend, Valentine, is in love with Sylvia and later on, upon setting eyes on Sylvia, Proteus instantly falls in love with her. Julia dresses in boy's clothes and spies on Proteus and towards the end of the play, when she reveals herself, Proteus, true to his name, changes his affections once again and vows fidelity to Julia again.[7]

William Wordsworth was a major English romantic poet. In 1802, he composed the sonnet, “The world is too much with us”, in which he feels humanity has distanced itself from nature and become absorbed in materialism. He wishes that he were raised according to a different vision of the world, in which he might see images of ancient gods rising from the seas. This sight would cheer him greatly and he references “Proteus rising from the sea,” and “Triton blowing his wreathed horn”.[8]

The word “proteus” has been incorporated into present-day usage in the English language. The Oxford English Dictionary describes the word “protean” as meaning “to be able to change frequently or easily; to be adaptable or versatile”.

Naval

Famous naval ships have been named after the ancient sea god, such as USS Proteus (AS-19), which was launched in 1942 and served in the United States Navy and HMS Proteus, which was launched in 1929 and served in the Royal Navy.[9]

Proteus is also the name given to a new generation of Wave Adaptive Modular Vessels (WAM-V™) based on patented technology developed by Marine Advanced Research, Inc. This flexible catamaran is unlike conventional boats which force the water to conform to their hull, instead Proteus WAM-V adjusts to the surface of the water.[10]

Medical

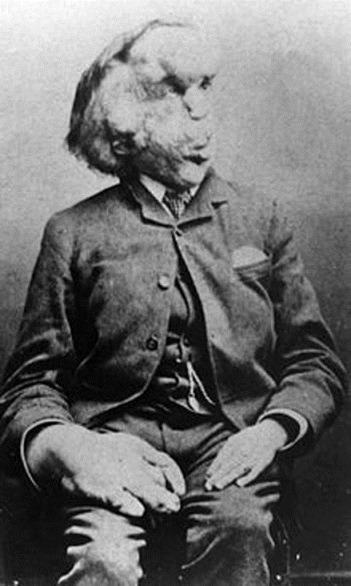

Joseph Carey Merrick was born on 5th August 1862. He was also known as ‘The Elephant Man’ [Figure 5]. He spent his early years in Leicester, but unable to get work due to his disfiguring deformities, he became a travelling exhibit, where people would pay to see him. His condition has been a source of curiosity for medical professionals and it was initially thought he had von Recklinghausen's disease. In 1986, Michael Cohen described his condition as ‘Proteus Syndrome’.[11]

Figure 5.

Joseph Carey Merrick, also known as ‘The Elephant Man’ [Image obtained from Wikipedia – Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_ Merrick]

The term Proteus syndrome was coined by Wiedemann et al., in 1983[12] to identify a disorder with protean manifestations including partial gigantism of the hands or feet, asymmetry of the arms and legs, skin overgrowth, atypical bone development and variable tumours over half the body. The syndrome was again named after the Greek sea god Proteus.

Symbolism and other associations

Protea, one of the oldest families of flowers on earth, dating back 300 million years, was also named after Proteus, son of Poseidon. In the same manner in which Proteus, the sea god, could change his shape, the protea flower presents itself in an astounding variety of shapes, sizes, hues and textures to make up more than 1,400 varieties. With its mythological associations with change and transformation, it is fitting that in the language of flowers, protea symbolizes diversity and courage.[13]

Proteus is the name given to an award-winning theatre company, which believes the audience is as important as the artist in creating a truly dynamic theatre experience. The website title reads, ‘Proteus, the changing shape of theatre’, and the company has a 30-year history of creating quality work, which collaborates with artists, often from different disciplines (e.g. photography, film, dance, music), in producing unique performance pieces. Their work has been shown in empty shop units, projected onto buildings, and played over sound systems in the streets.[14]

Proteus, also known as Neptune VIII, is the second largest Neptunian moon, and Neptune's largest inner satellite. Discovered by Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1989, it is more than 400 km in diameter, has an irregular shape with several concave facets and its largest crater measuring more than 200 km in diameter.[15]

Proteus was the name given to a Marvel Comics character, also known as Mutant X and featuring in the X-men comics. Aptly named, Proteus was a mutant possessing the ability to manipulate and alter reality, allowing him to transmute matter and bend the laws of physics according to his imagination. His character could turn a building into liquid or transform energy into matter.[16]

Proteus Mirabilis

This brings us back full circle to Proteus mirabilis, which has a ‘swarming growth’ and it is this quality that is fairly unique to the bacterial genus proteus. It forms highly elongated rods with thousands of flagella that translocate across the surface of agar plates. There are other genera which can swarm but species like Proteus mirabilis form concentric circles instead of dendritic patterns on agar plates. There are various mechanisms by which Proteus mirabilis can also evade the host defenses and some of these mechanisms may also be seen in other bacteria too. The first is production of an IgA-degrading protease which cleaves the host's IgA antibody. It also has unique flagellin genes, which can recombine and form novel flagella capable of tricking the host's defenses. Through the expression of the MR/P fimbriae, which undergo a process called phase variation, this then generates heterogeneity, which increases virulence.[17,18] Other mechanisms include secreting endotoxins and urease. Urease encourages struvite stone formation, which can allow the bacteria to reside within the stone, protected from antibiotic attack.[19]

Almost 125 years on from its first discovery by Hauser, the full genome sequence of Proteus mirabilis was completed on 28 March 2008 by Melanie Pearson identifying more than 3,658 coding sequences with seven rRNA loci.[19] The genome's total length was 4.063 Mb. The paper was titled, “Complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis, a master of both adherence and motility.”

CONCLUSION

By studying the etymology of the word “proteus”, the bacteria we treat on a day-to-day basis may be seen in a different light. Ranging from its colourful historical references and literary connections, we have shown that the derivation of this word and its present-day usage is deeply entrenched in and stems from it true mythological origin.

Acknowledgments

Laura Swift – Greek and Latin – Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at University College, London.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pearson MM, Sebaihia M, Churcher C, Quail MA, Seshasayee AS, Luscombe NM, et al. Complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis, a master of both adherence and motility. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4027–37. doi: 10.1128/JB.01981-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mobley HL, Belas R. Swarming and pathogenicity of Proteus mirabilis in the urinary tract. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:280–4. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88945-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rather PN. Swarmer cell differentiation in Proteus mirabilis. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1065–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guinard F. New York: Prometheus Press; 1959. in Larousse Encylcopedia of Mythology; p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Homer. The Odyssey. Chapter IV: Lines 365-570. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helenica, 2010 (Homer: The Odyssey Book 4: Translation by Ian Johnston) [Last accessed on 2011 June 27]. Available from: http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/Texts/Odyssey/Odyssey04.html .

- 7.Shakespeare W. The Two Gentleman of Verona. In: Warren R, editor. Oxford: OUP Oxford Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wordsworth W. Vol. 5. New York: Cosimo Inc Publishers; 2008. The Complete Poetical Works of William Wordsworth, in Ten Volumes; p. 36. 1806-15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Naval Ships. 2011. [Last accessed on 2011 June 27]. Available from: http://www.worldnavalships.com .

- 10.WAM-V Marine Advanced Research, Inc. [Last accessed on 2011 June 27]. Available from: http://wam-v.com .

- 11.Tibbles JA, Cohen MM., Jr The Proteus syndrome: The Elephant Man diagnosed. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:683–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6548.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiedemann HR, Burgio GR, Aldenhoff P, Kunze J, Kaufmann HJ, Schirg E. The Proteus Syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 1983;140:5–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00661895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The meaning and symbolism of Protea. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.teleflora.com/about-flowers/protea.asp .

- 14.The Proteus Theatre Company Ltd. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.proteustheatre.com .

- 15.Proteus – the moon. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug 20]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proteus_(moon)

- 16.Proteus – comics. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug 20]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proteus_(comics)

- 17.Belas R. Proteus mirabilis Swarmer Cell Differentiation and Urinary Tract Infection. In: Warren JW, editor. Urinary Tract Infections: Molecular Pathogenesis and Clinical Management. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 271–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansen AM, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Mobley HL. Visualization of Proteus mirabilis morphotypes in the urinary tract: The elongated swarmer cell is rarely observed in ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3607–13. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3607-3613.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearson MM, Sebaihia M, Churcher C, Quail MA, Seshasayee AS, Luscombe NM, et al. Complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis, a master of both adherence and motility. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4027–37. doi: 10.1128/JB.01981-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]