Abstract

Background

Within a pilot trial regarding chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, the secondary aim of the main study was explored. This involved measuring the effects—as shown on two key measurement scales reflecting quality of life (QoL)—of verum versus sham acupuncture on patients with ovarian cancer during chemotherapy.

Objective

The aim of this substudy was to determine the feasibility of determining the effects of verum acupuncture versus sham acupuncture on QoL in patients with ovarian cancer during chemotherapy.

Design

This was a randomized, sham-controlled trial.

Setting

The trial was conducted at two cancer centers.

Patients

Patients with ovarian cancer (N=21) who were receiving chemotherapy—primarily intravenous carboplatin and paclitaxel—participated in this substudy.

Intervention

The participants were given either active or sham acupuncture 1 week prior to cycle 2 of chemotherapy. There were ten sessions of acupuncture, with manual and electro-stimulation over a 4-week period.

Main Outcome Measures

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality-of-Life Questionnaire-Core 30 Item (EORTC-QLQ-C30) and the Quality of Life Questionnaire–Ovarian Cancer Module-28 Item (QLQ-OV28) were administered to the patients at baseline and at the end of their acupuncture sessions.

Results

Of the original 21, 15 patients (71%) completed the study, and 93% of them completed the questionnaires. The EORTC-QLQ-C30 subscores were improved in the acupuncture arm, including the mean scores of social function (SF), pain, and insomnia (p=0.05). However, after adjusting for baseline differences, only the SF score was significantly higher in the active acupuncture arm, compared with the sham acupuncture arm (p=0.03).

Conclusions

It appears feasible to conduct a randomized sham-controlled acupuncture trial measuring QoL for patients with ovarian cancer who are undergoing chemotherapy. Acupuncture may have a role in improving QoL during chemotherapy.

Key Words: Acupuncture, Randomized Controlled Trial, Chemotherapy, Neutropenia, Ovarian Cancer, Quality of Life, EORTC

Introduction

Improving quality of life (QoL) is one of the three major therapeutic goals in cancer treatment, along with improving survival and cure rates. Several studies have shown that QoL predicts important outcomes of therapy and directly affects the survival of patients with cancer in general.1,2 In the case of patients with ovarian cancer, the global QoL scores have been shown to be a prognostic factor for both progression free-survival and overall survival in the population of patients with advanced ovarian cancer.2,3

Preliminary evidence has suggested that acupuncture is a type of medical intervention that has demonstrated an ability to improve QoL in patients with cancer.4–9 However, the impact of acupuncture in health-related QoL in the population of patients with ovarian cancer during chemotherapy has not been evaluated, especially in a randomized controlled clinical trial.

The current authors conducted a pilot, randomized, sham-controlled acupuncture trial during one cycle of myelosuppressive chemotherapy in women with gynecologic malignancies.10 The primary aim of that study was to determine if an active acupuncture protocol could reduce chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, compared with sham acupuncture (the result of that study has been reported elsewhere).10 This article is a brief report on the secondary aim of the study—to determine the feasibility of studying the effect of acupuncture on QoL in patients with ovarian cancer during chemotherapy.

Materials And Methods

Study Population and Design

The detailed study protocol for the original study has been published elsewhere.10 Briefly, women with newly diagnosed and recurrent primary ovarian cancer; primary peritoneal cancer; papillary serous cancer of the uterus; and mixed mesodermal tumors of the uterus, ovary, or fallopian tube, who were undergoing standard myelosuppressive chemotherapy (primarily intravenous [i.v.] carboplatin and paclitaxel in a 21-day cycle), were included in that original study. Exclusion criteria included use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) during the treatment; history of a symptomatic cardiac condition; and uncontrolled major psychiatric disorders, such as major depression and psychosis.

Potentially eligible patients were contacted by a research assistant and by treating physicians. Written consent was obtained from each participant. Patients were told that they would have an equal chance to be assigned to either a sham acupuncture arm or an active acupuncture arm. The randomization procedure was generated by a study statistician, using a permuted block randomization with a variable block size. The assignment list was kept at a central trial office. A total of 21 patients were recruited and randomized to receive either verum acupuncture (n=11) or sham acupuncture (n=10). All study personnel, except treating acupuncturists, including treating oncologists, statistician, and the patients, were blinded to the treatment assignment. The study was approved by institutional review boards and registered with clinicaltrial.gov (ID# NCT00090389).

Acupuncture

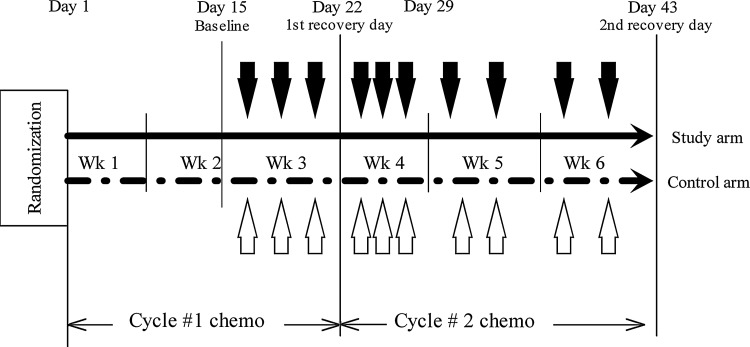

In both the verum and sham acupuncture arms, patients received 10 sessions of acupuncture treatment, 2–3 times per week, beginning 1 week prior to cycle 2 of chemotherapy and ending prior to cycle 3 of chemotherapy. Treatments were specifically chosen to begin 2 weeks into chemotherapy. At the time following diagnosis and surgery, every patient was physically and emotionally overwhelmed, thus, once a patient had treatment underway, this was a better time for patients to make informed decisions regarding participating in the trial, which were expected to translate into better recruitment and retention. Figure 1 presents the study schema.

FIG. 1.

Study schema outlining a 21-day cycle of chemotherapy and timing of acupuncture treatment. Black downward arrows, active acupuncture treatments; white upward arrows, sham acupuncture treatments; black horizontal line, verum (study) arm; dashed horizontal line, sham arm. Wk, week; chemo, chemotherapy.

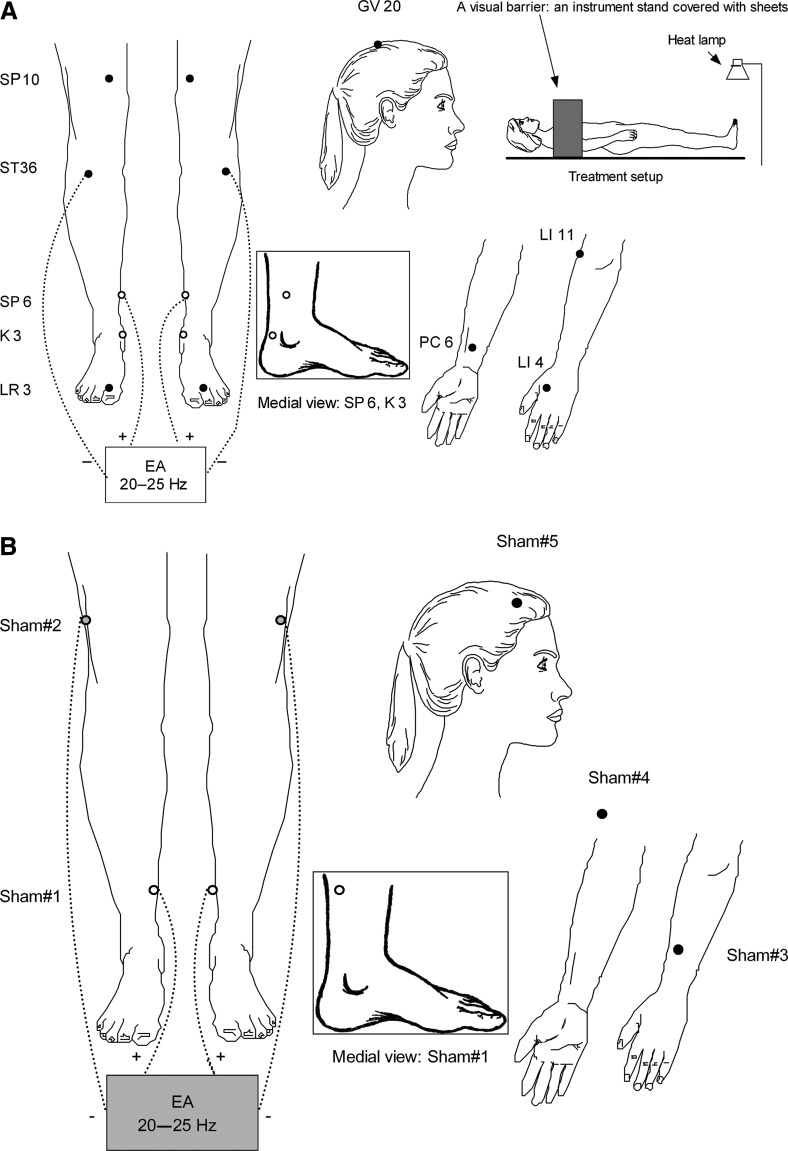

The verum arm received acupuncture treatments that needled nine acupuncture points (17 needling sites). The determination of the verum acupuncture protocol was based upon the current authors' previous systematic review of similar clinical trials from China and consensus of our acupuncture team members.11–14 Figure 2A shows the locations of verum acupoints, treatment setup, and the technical specifications of the verum arm. After needle insertions, the needling sensation of De Qi, was manually produced once on at least 2 points on each participant's legs and at 1 point on the arms. In addition, an electroacupuncture (EA) stimulator was bilaterally connected on the patient's legs, at a frequency of 20–25 Hz. Acupuncturists were instructed to increase the intensity of the stimulation slowly until patients “orally” reported having the sensation.

FIG. 2.

(A) Active acupuncture protocols, treatment setup and technical specifications: acupuncture needle size, 0.20×25 mm (Vinco,® Helio Medical Supplies, Inc.); needling depth: 10 mm; De Qi requirement, Yes; electroacupuncture (EA) model, AWQ-104L (Mayfair Medical Supplies Ltd., Hong Kong); TDP infrared heat lamp, 30 cm above the feet; and needle retaining and stimulating duration, 30 minutes. Open dots indicate location on the medial side; closed dots indicate location at the front. (B) Sham acupuncture protocols, treatment setup and technical specifications: Acupuncture needle size, 0.12×30 mm (Seirin,® Seirin Corporation, Japan); needling depths: <0.2 mm; De Qi sensation prohibited, no needle manipulations; electroacupuncture model, deactivated AWQ-104 L; TDP infrared heat lamp, 75 cm above the feet; needle retaining and stimulating duration, 30 minutes. Shadowed box indicates inactive EA. Open dots indicate location on the medial side; closed dots indicate location at the front; shadowed dots indicate location on the lateral side.

The sham acupuncture protocol used 5 nonacupuncture points (9 needling sites), with an intent to minimize potential physiological effects. All sham points were in the proximity of verum points but were off the meridians (the energetic pathways upon which Traditional Chinese Medicine [TCM] theory is based). Once the needles were minimally inserted, no hand manipulation and De Qi were allowed. An identical but deactivated EA stimulator was used. Figure 2B shows the locations of sham points and other technical specifications. During each session, a visual barrier was used to block each patient's view of needling sites (Fig. 2A). The treatment duration was 30 minutes. Patients in both arms of the study were treated by the same acupuncturists (n=5), who were licensed, and who had more than 10 years of experience in clinical practice. Efforts were made to ensure the same amount of contact time between the treating acupuncturists and patients in the two study arms. To determine the effectiveness of blinding, a validated treatment credibility scale was given to each patient to complete.15–17

QoL Questionnaires

Two QoL surveys were used: (1) the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 Item (EORTC QLQ-C30); and (2) Quality of Life Questionnaire-Ovarian Module–28 Item (QLQ-OV28).

Eortc-Qlq-C30

The core quality of life questionnaire, EORTC-QLQ-C30, has 30 items covering the following areas: general physical symptoms; physical functioning; fatigue/malaise; social functioning; and psychological distress. All items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from “Not at All” to “Very Much,” with the exception of the impact of health on overall QoL, which uses a visual analogue scale ranging from 1 (“Very Poor”) to 7 (“Excellent”).18–20

Qlq-Ov28

The ovarian module consists of 28 items that are categorized into 6 factors: abdominal/gastrointestinal symptoms, peripheral neuropathy, other chemotherapy side-effects specific to ovarian-cancer treatments, hormonal symptoms, body image, sexuality, and attitudes concerning the disease and its treatment.21

Administration of Questionnaires

The questionnaires were administered at two timepoints: (1) at baseline prior to the first acupuncture session; and (2) the second recovery day, which was at the end of the tenth acupuncture session, prior to cycle 3 of chemotherapy.

Statistical Analysis

The QLQ-C30 questionnaire was scored according to the manual supplied by the EORTC. A mean score change of ≥10 in the QLQ-C30 was interpreted as being a clinically meaningful moderate change.22 Changes from baseline in the scales of EORTC QLQ-C30 were compared between treatment arms. Comparisons of baseline means were performed by the Mann-Whitney-U test as well as an independent samples t-test. Given that the results between the two methods were consistent, the t-test results are presented here. No multiple comparisons were performed. The comparison of the means at the second recovery between the two groups was performed by analysis of covariance with baseline scores included as a covariate. A “last number carried forward” method was used to deal with missing data. The SAS statistical software package (version 9) was used for all analyses. All tests were nondirectional and a p-value<0.05 was considered to bestatistically significant.

Results

Feasibility of Recruitment and Subject Retention

The patient flow diagram in CONSORT [CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials] format has been published elsewhere.10 The original recruitment goal (n=50) was not met, largely because there were many competing trials. However, among 21 patients recruited for that study, randomization resulted in comparable groups, of whom 11 were in the active arm and 10 were the sham arm. Five (24%) patients withdrew during that study because of disease progression (n=4) and side-effects of chemotherapy (n=1). One patient in the sham arm was disqualified because that patient used G-CSF. These dropouts were evenly distributed in the verum arm (n=3) and the sham arm (n=3). The average number of acupuncture sessions received before those patients left the study between two arms were similar (4.7 versus 6.5). The remaining 15 patients completed all 10 sessions of acupuncture and adhered to treatment as scheduled. The overall completion rate for this pilot study was 71% (15/21). Among these patients, 14 (93%) completed the QoL questionnaires. The number of patients who guessed correctly which treatment arm they were in was similar between the verum arm and the sham arm (40% versus 30%), indicating good treatment blinding. No significant adverse events associated with acupuncture needling were observed.

In these patients, 9 (43%) were newly diagnosed and 12 (57%) had a recurrence of disease. Eleven (52%) patients received standard 21-day i.v. carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy and the rest received gemcitabine, topotecan, and Vinorelbine. Comparisons for baseline demographic and disease characteristics of patients in both arms were previously reported, and the two treatment groups were comparable in these characteristics.10 Patient characteristics and the chemotherapy agents were essentially equivalent between the two groups. Table 1 presents the relevant baseline demographics and disease characteristics.

Table 1.

Patients' Characteristics

| Characteristic | Active acupuncture (n=11) | Sham acupuncture (n=10) |

|---|---|---|

| Age±SD | 50.8±10.6 | 50±9.9 |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 1 | 8 | 7 |

| New diagnosis | 4 (19%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| Recurrent disease | 7 (33.3%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| # (%) of patients receiving specific drug treatment | ||

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel | 6 (28.6%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| Gemcitabine | 3 (14.3%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| Topotecan | 1 (4.8%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Vinorelbine | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) |

SD, standard deviation; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Treatment Effects on QoL

Overall, 20 patients completed the QLQ-C30 questionnaire at baseline. Most QLQ-C30 mean scores between the two treatment arms were very similar without clinically meaningful differences (>10 points), except in pain, insomnia, and constipation subscores, for which patients in the sham acupuncture arm had slightly worse scores. However, only constipation was statistically different between two arms (p=0.03).

Seventeen patients completed the EORTC Ovarian Module (QLQ-OV28) at baseline. All ovarian module subscores between the two treatment arms were similar, except for the hormonal item, for which the sham acupuncture arm had a slightly worse score. However, no statistically significance between the two arms was found in any subscore.

EORTC-QLQ-C30 subscores were available from 14 patients at the second recovery day. Noncompletion of the second assessment resulted mainly from withdrawal from the study. In the unadjusted analyses, four QoL subscores were ≥10 points different from the sham arm in the direction of improvement in the verum arm: social function (81.0 versus 52.4, p=0.05); pain (11.9 versus 31.0, p=0.05); insomnia (14.3 versus 9.5, p=0.05) and constipation (19.0 versus 33.3, p=0.05). Meanwhile, the score for nausea and vomiting exceeded 10 points in the direction of deterioration in the verum acupuncture arm: (14.3 versus 2.4, p=0.08). However, after adjusting for baseline score differences, only the social function subscore was significantly higher in the verum acupuncture arm, compared with the sham acupuncture arm (p=0.03). Table 2 presents EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-OV28 subscores between the verum and sham acupuncture groups at baseline and on the second recovery day.

Table 2.

Selected EORTC-QLQ-C30 and QLQ-OV28 Subcale Scores in Active and Sham Acupuncture Groups at Baseline and on 2nd Recovery Day

|

Mean QoL subscores (SD) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Active acupuncture group |

Sham acupuncture group |

|

||||||

| |

Baseline |

2nd Recovery |

Baseline |

2nd Recovery |

|

||||

| Scales& subscales | n | n | n | n | p-Value | ||||

| QLQ-C30 | |||||||||

| Global QoL | 9 | 63.9 (20.4) | 7 | 69.0 (22.4) | 10 | 62.5 (19.3) | 7 | 63.1 (17.3) | 0.94 |

| PF | 10 | 76.7 (21.1) | 7 | 82.9 (14.3) | 9 | 71.1 (18.3) | 7 | 78.1 (12.6) | 0.55 |

| RF | 10 | 63.3 (40.7) | 7 | 76.2 (30.2) | 10 | 65.0 (30.9) | 7 | 73.8 (28.6) | 0.97 |

| EF | 10 | 75.8 (16.9) | 7 | 78.6 (18.5) | 9 | 64.8 (25.6) | 7 | 77.4 (10.4) | 0.36 |

| CF | 10 | 76.7 (23.8) | 7 | 78.6 (15.9) | 10 | 71.7 (22.3) | 6 | 83.3 (21.1) | 0.24 |

| SF | 10 | 65.0 (34.7) | 7 | 81.0 (20.3) | 10 | 60.0 (22.5) | 7 | 52.4 (27.9) | 0.03* |

| Fatigue | 10 | 38.9 (18.3) | 7 | 34.9 (18.6) | 10 | 40.0 (24.1) | 7 | 36.5 (8.4) | 0.89 |

| N/V | 10 | 13.3 (18.9) | 7 | 14.3 (15.0) | 10 | 18.3 (18.3) | 7 | 2.4 (6.3) | 0.06 |

| Pain | 10 | 21.7 (22.3) | 7 | 11.9 (8.1) | 10 | 33.3 (26.1) | 7 | 31.0 (20.3) | 0.11 |

| Dyspnea | 10 | 20.0 (23.3) | 7 | 14.3 (17.8) | 10 | 13.3 (17.2) | 7 | 9.5 (16.3) | 0.61 |

| Insomnia | 10 | 26.7 (30.6) | 7 | 14.3 (17.8) | 10 | 50.0 (32.4) | 7 | 38.1 (23.0) | 0.70 |

| AL | 10 | 20.0 (23.3) | 7 | 19.0 (26.2) | 10 | 26.7 (34.4) | 7 | 14.3 (17.8) | 0.52 |

| Constipation | 10 | 20.0 (23.3) | 7 | 19.0 (26.2) | 10 | 53.3 (39.1) | 7 | 33.3 (47.1) | 0.33 |

| Diarrhea | 10 | 6.7 (14.1) | 7 | 19.0 (26.2) | 10 | 6.7 (14.1) | 7 | 19.0 (26.2) | 0.97 |

| FF | 10 | 20.0 (35.8) | 7 | 28.6 (40.5) | 10 | 16.7 (23.6) | 7 | 28.6 (30.0) | 0.71 |

| QLQ-OV28 | |||||||||

| Ab/GI | 9 | 26.5 (14.1) | 6 | 33.3 (13.1) | 8 | 31.9 (19.9) | 7 | 27.8 (22.7) | 0.21 |

| PN | 8 | 12. 5 (17.3) | 7 | 38.1 (35.6) | 8 | 16.7 (25.2) | 8 | 4.2 (11.8) | 0.05* |

| Hormonal | 9 | 11. 1 (22.0) | 7 | 14.3 (15.0) | 8 | 22.9 (35.6) | 8 | 29.2 (35.4) | 0.36 |

| Body image | 9 | 24.1(20.6) | 7 | 16.7 (23.6) | 7 | 28.6 (35.6) | 8 | 20.8 (19.4) | 0.97 |

| AD/T | 9 | 51. 9 (29.9) | 7 | 41.3 (21.0) | 8 | 52.8 (21.2) | 8 | 52.8 (23.6) | 0.55 |

| Chemo SE | 8 | 13.3 (10.1) | 7 | 15.2 (11.4) | 8 | 24.2 (13.8) | 8 | 24.2 (13.3) | 0.40 |

| Others | 4 | 33.3 (11.8) | 2 | 50.0 (23.6) | 2 | 29.2 (17.7) | 5 | 35.0 (26.0) | — |

p-Value: difference at 2nd recovery between 2 groups using analysis of covariance to adjust for baseline difference.

p-Value≤0.05.

EORTC-QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 Item; QLQ-OV28, Quality-of-Life Questionnaire-Ovarian Cancer Module-28 Item; QoL, quality of life; PF, physical function; RF, role function; EF, emotional function; CF, cognitive function; SF, social function; N/V, nausea/vomiting; AL, appetite loss; FF, financial difficulty; Ab/GI, abdominal/gastrointestinal; PN, peripheral neuropathy, AD/T, attitude regarding disease and treatment; Chemo SE, chemotherapy side-effects.

EORTC Ovarian Module (QLQ-OV28) scores were available from 15 patients by the second recovery day. Compared with the sham acupuncture arm, patients in the verum acupuncture arm had favorable subscores in hormonal (14.3 versus 29.2, p=0.32) and attitudes toward disease and treatment (41.3 versus 52.8, p=0.34) subscores, while worsening in peripheral neuropathy (38.1 versus 4.2, p=0.02). However, after adjusting for baseline differences, only the score of peripheral neuropathy was still significantly higher in the verum acupuncture arm, compared with the sham acupuncture arm (p=0.05).

Discussion

It appears feasible to recruit patients with ovarian cancer into a sham-controlled acupuncture trial during a chemotherapy phase. Although the original recruitment target was not achieved, the majority of patients who enrolled into the study completed required acupuncture sessions and EORTC QoL questionnaires. Patients who dropped out of the study did so mainly because of disease progression or side-effects of chemotherapy. The acupuncture protocols were well-tolerated by study patients with no significant adverse effects.

Ovarian cancer is one of most aggressive diseases in women. After being diagnosed with ovarian cancer, patients often face enormous emotional and physical distress. It was a challenge to recruit patients into an acupuncture study during this peroid. Therefore, the starting time of acupuncture was intentionally postponed so that patients would have enough time to adjust and adapt to the impact of chemotherapy before choosing to participate in the acupuncture study. The recruitment challenge was also unique, because many potentially life-saving clinical trials were simultaneously available to the same patient population during the same time period, and many potentially eligible patients chose to participate in those other trials.

With respect to QoL measurements, patients self-reported social functioning has been suggested and recently confirmed as being a key independent prognostic factor for survival.1 The social function variable is concerned with how the disease burden has limited a patient's social functioning. One study found that an improved social functioning score was independently associated with a decreased likelihood of colorectal cancer surgical complications.23 For ovarian cancer, most patients have debulking surgery prior to starting chemotherapy, which is very similar to what happens to patients who have colorectal cancer. In the current study, the increased 28.6 points in social functioning score (p=0.03) in the verum acupuncture arm at the second recovery timepoint may reflect a faster recovery from surgical complications, compared with what occurred in the sham acupuncture arm.

The impact of QoL on outcome may vary depending on the extent of the disease, the specific type of cancer, age of a patient, and the patient's gender.24 In the ovarian-cancer population, a study found that patients with a better baseline global QoL scores on the QLQ-C30 had improved outcomes, both in progression-free survival and overall survival.2 In the current study, the reported mean baseline EORTC global QoL scores of this population (63.9 in the verum arm and 62.5 in the sham are) were similar to baseline scores reported in another trial (64.3).25 After acupuncture treatment, the verum acupuncture group had a 6-point greater improvement in global QoL score, compared to the sham acupuncture group score (69.0 versus 63.1, p=0.94, adjusted), which was only 1.1 point lower than that was found in a general noncancer population in the same gender and age brackets (69.0 versus 70.1),24 suggesting a nearly “norm value” in the verum arm.

Patient-reported changes in subscores on the EORTC ovarian module (QLQ-OV28) may not only reflect symptoms of patients with ovarian cancer but may also be influenced by characteristics of the treatment itself. On the second recovery day, the peripheral neuropathy score in the verum arm was 33.9 points more than that in the sham group (p=0.05, adjusted). In the ovarian cancer module, QLQ-OV28, patients were asked about symptoms experienced during the previous week. Two questions were related to peripheral neuropathy: “Have you had tingling hands or feet?” and “Have you had numbness in your fingers or toes?” In an ordinary chemotherapy trial, changes in those two questions would indicate peripheral neuropathy symptoms caused by chemotherapy agents. However, in the current study, the elevated “peripheral neuropathy” score in the verum acupuncture group most likely reflected the EA stimulation sensation experienced by the study patients, rather than actual neurological damage. According to the study protocol, the frequency of electrostimulation was set at 20 Hz, which produces an unmistakable “tingling” sensation in the legs of patients, and the patients were asked to “orally” confirm that they experienced this sensation during the treatment. Moreover, the study patients filled out the questionnaire within 30 minutes of completion of their last acupuncture treatment, when the acupuncture stimulation they experienced was still vivid and fresh. None of these patients complained of higher-than-usual neuropathic symptoms in a later follow-up period. Therefore, what patients reported in the questionnaire may be a result of a confounding phenomenon between sensations elicited by the electrostimulation and the timing of administrating the questionnaire. However, given that a subsequent retest was not performed, the possibility of any actual neurological damage caused by electrostimulation cannot be completely ruled out.

Conclusions

The current study suggests that it is feasible to conduct a sham-controlled trial evaluating the impact of acupuncture on QoL during chemotherapy in patients with ovarian cancer. The acupuncture protocol used in the trial is a safe and valid intervention that could be tested further for its potential effectiveness for improving QoL in future trials. Because of the small sample size and the pilot nature of the original study, no firm conclusions can be drawn from data presented here. Nevertheless, the preliminary findings of the study suggest that acupuncture may have a positive role in improving social function in a group of patients with ovarian cancer who are undergoing chemotherapy. Reports of sensations from EA stimulation on the legs may be confounded with neuropathy items in QLQ-OV28. In future trials, increasing sample size, changing the timing of questionnaire administration (i.e., wait for several hours or 24 hours later), and long-term follow up are required to verify these findings.

Acknowledgments

This project described was supported by Grant Number 1U19AT002022-01 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Efficace F. Innominato PF. Bjarnason G, et al. Validation of patient's self-reported social functioning as an independent prognostic factor for survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: results of an international study by the Chronotherapy Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(12):2020–2026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carey MS. Bacon M. Tu D. Butler L. Bezjak A. Stuart GC. The prognostic effects of performance status and quality of life scores on progression-free survival and overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108(1):100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakusta CM. Atkinson MJ. Robinson JW. Nation J. Taenzer PA. Campo MG. Quality of life in ovarian cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81(3):490–495. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker EM. Rodriguez AI. Kohn B, et al. Acupuncture versus Venlafaxine for the management of vasomotor symptoms in patients with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;28(4):634–640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia MK. Chiang JS. Cohen L, et al. Acupuncture for radiation-induced xerostomia in patients with cancer: a pilot study. Head Neck. 2009;31(10):1360–1368. doi: 10.1002/hed.21110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho JH. Chung WK. Kang W. Choi SM. Cho CK. Son CG. Manual acupuncture improved quality of life in cancer patients with radiation-induced xerostomia. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(5):523–526. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng G. Vickers A. Yeung S, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of acupuncture for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5584–5590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crew KD. Capodice JL. Greenlee H, et al. Pilot study of acupuncture for the treatment of joint symptoms related to adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1(4):283–291. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong RK. Jones GW. Sagar SM. Babjak AF. Whelan T. A Phase I-II study in the use of acupuncture-like transcutaneous nerve stimulation in the treatment of radiation-induced xerostomia in head-and-neck cancer patients treated with radical radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(2):472–480. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu W. Matulonis UA. Doherty-Gilman A, et al. Acupuncture for chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in patients with gynecologic malignancies: a pilot randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(7):745–753. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang XM. Chen HL. Ma YM. Shao MY. Effect of acupuncture and moxibustion on leukopenia in chemotherapy. Henan Trad Chinese Med. 1991;11(5):32–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du XD. Gou Y. Chen F, et al. Compare different timing acupuncture on mitigating hematopoietic impairment caused by chemotherapy. Chinese Acupunct Moxibustion. 1994;14(3):113–115. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li ZP. Acupuncture treatment on leukopenia in 65 middle-advanced stage cancer patients after radiochemotherapy. Jiangxi Med J. 1995;30(6):355–356. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu W. Hu D. Dean-Clower E, et al. Acupuncture for chemotherapy-induced leukopenia: Exploratory meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2007;5(1):1–10. doi: 10.2310/7200.2006.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borkovec TD. Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;3(4):257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macklin EA. Wayne PM. Kalish LA, et al. Stop Hypertension with the Acupuncture Research Program (SHARP): results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Hypertension. 2006;48(5):838–845. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000241090.28070.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wayne PM. Krebs DE. Macklin EA, et al. Acupuncture for upper-extremity rehabilitation in chronic stroke: a randomized sham-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(12):2248–2255. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.07.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aaronson NK. Ahmedzai S. Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aaronson NK. Bullinger M. Ahmedzai S. A modular approach to quality-of-life assessment in cancer clinical trials. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1988;111:231–249. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-83419-6_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hjermstad MJ. Fossa SD. Bjordal K. Kaasa S. Test/retest study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire. J Clin Oncol. May. 1995;13(5):1249–1254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.5.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cull A. Howat S. Greimel E, et al. Development of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer questionnaire module to assess the quality of life of ovarian cancer patients in clinical trials: a progress report. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osoba D. Rodrigues G. Myles J. Zee B. Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anthony T. Hynan LS. Rosen D, et al. The association of pretreatment health-related quality of life with surgical complications for patients undergoing open surgical resection for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2003;238(5):690–696. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094304.17672.6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarz R. Hinz A. Reference data for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30 in the general German population. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(11):1345–1351. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matulonis UA. Krag KJ. Krasner CN, et al. Phase II prospective study of paclitaxel and carboplatin in older patients with newly diagnosed Mullerian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(2):394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]