Abstract

Firearms have widely supported legitimate purposes but are also frequently used in violent crimes. Owners and senior executives of federally licensed firearms dealers and pawnbrokers are a potentially valuable source of information on retail commerce in firearms, links between legal and illegal commerce, and policies designed to prevent the firearms they sell from being used in crimes. To our knowledge, there has been no prior effort to gather such information. In 2011, we conducted the Firearms Licensee Survey on a probability sample of 1,601 licensed dealers and pawnbrokers in the United States believed to sell 50 or more firearms per year. This article presents details of the design and execution of the survey and describes the characteristics of the respondents and their business establishments. The survey was conducted by mail, using methods developed by Dillman and others. Our response rate was 36.9 % (591 respondents), similar to that for other establishment surveys using similar methods. Respondents had a median age of 54; 89 % were male, 97.6 % were White, and 98.1 % were non-Hispanic. Those who held licenses under their own names had been licensed for a median of 18 years. A large majority of 96.3 % agreed that “private ownership of guns is essential for a free society”; just over half (54.9 %) believed that “it is too easy for criminals to get guns in this country.” A match between the job and a personal interest in the shooting sports was the highest-ranking reason for working as a firearms retailer; the highest-ranking concerns were that “there are too many ‘gun control’ regulations” and that “the government might confiscate my guns.” Most respondents (64.3 %) were gun dealers, with significant variation by region. Residential dealers accounted for 25.6 % of all dealers in the Midwest. Median annual sales volume was 200 firearms for both dealers and pawnbrokers. Dealers appeared more likely than pawnbrokers to specialize; they were more likely to rank in the highest or lowest quartile on sales of handguns, inexpensive handguns, and tactical rifles. Sales of inexpensive handguns and sales to women were more common among pawnbrokers. Internet sales were reported by 28.3 % of respondents and sales at gun shows by 14.3 %. A median of 1 % of sales were denied after purchasers failed background checks; firearm trace requests equaled <1 % of annual sales. Trace frequency was directly associated with the percentage of firearm sales involving handguns, inexpensive handguns, and sales to women. Frequency of denied sales was strongly and directly associated with frequency of trace requests (p < 0.0001). These results are based on self-report but are consistent with those from studies using objective data.

Keywords: Firearms, Crime, Violence, Firearms policy, Federal firearms licensees

Introduction

Firearms are a dual-use technology. Though they have legitimate employment in sport and in maintaining personal and public safety, they are also frequently used in violent crimes. An estimated 348,975 firearm-related violent crimes, including 11,015 homicides, occurred in the United States in 2010.1,2

The more than 50,000 federally licensed firearms dealers and pawnbrokers in the United States sell millions of firearms each year and are the principal means by which civilians gain access to firearms. These sales are regulated in an effort to prevent the criminal use of firearms, and extensive research has highlighted the importance of individual retailers in both preventing and facilitating such use.3–15

Because of their sustained and direct involvement, owners of or senior executives at licensed firearms dealers and pawnbrokers are likely to have uniquely valuable information on and insight into the operations of retail commerce in firearms, links between legal and illegal commerce, and policies designed to prevent the firearms they sell from being used in crimes. To our knowledge, there has been no prior effort to gather such information. Nor, to our knowledge, has there been an effort to construct an aggregate statistical profile of licensed firearms dealers and pawnbrokers in the United States.

In 2011, we conducted the Firearms Licensee Survey to collect data from a large sample of such establishments across the United States that were known to be actively engaged in selling firearms. Our target respondent population was the owners or senior executives of those establishments. The survey addressed the respondents’ demographics; their incentives for and concerns about employment as a licensed retailer; characteristics of the establishments at which they worked, such as the nature of the clientele and the number and types of firearms sold; the frequency of illegal and adverse events such as surrogate (straw) purchases and denied sales; the prevalence of and motivations for knowing participation in illegal commerce by licensed retailers; and the respondents’ positions on current or proposed policies regulating firearms commerce.

This article presents details on the design and execution of the Firearms Licensee Survey and describes the characteristics of the respondents themselves and their business establishments.

Methods

Terminology

In reporting on the Firearms Licensee Survey, we use “retailer” only to refer to an individual person.

Identifying the Study Population

A roster of all federal firearms licensees, including manufacturers, importers, and collectors, as well as gun dealers and pawnbrokers, is available online from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) and is updated monthly.16 Entries contain the name of the licensee (who may be an individual person or a corporation), the license type and number, the business name and telephone number, and both premises and mailing addresses. A separate license is required for each fixed location at which firearms transactions are conducted; some large chain-store corporations hold dozens of licenses. In such cases, the mailing address for all locations is typically that of the corporate headquarters, but the premises addresses are specific to individual retail establishments. We used the list for February 2011 to create a file with records for all 55,020 licensees who were classified as retail establishments: gun dealers and gunsmiths, who hold Type 01 licenses, and pawnbrokers, who hold Type 02 licenses.

Retail licensees may sell firearms only occasionally or not at all, and we wished to restrict the study population to those who were known to be more than occasional sellers of firearms. Licensees do not report their sales in most states; the data for a direct determination do not exist. However, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) collects data on background checks performed by its National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS checks) on firearm purchasers at the request of licensees. NICS checks are required for the great majority of firearm sales made by licensed gun dealers and pawnbrokers. Records for individual requests are retained for 90 days after the requests are made.

The number of NICS checks requested by a licensee does not equal the number of firearms that licensee sells, for several reasons. (1) In so-called Brady alternative states, purchases by holders of permits to carry concealed firearms and similar permits are exempt from the requirement.17 There were 18 such states when the study was conducted. (2) Only one NICS check is required per transaction, regardless of the number of firearms involved. (3) A small percentage of sales are denied (the nationwide average is 1.8 %18), and the sale does not proceed. (4) Background checks are also required when firearms are redeemed from pawnbrokers. Nonetheless, NICS checks may be considered a rough proxy measure for firearm transactions for both dealers and pawnbrokers.

In response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, the FBI provided a tabulation of NICS check requests, specific to individual licensees, for the 88-day period November 13, 2010, through February 9, 2011. These dates were not chosen deliberately; the data were compiled as soon as possible after the FOIA request was approved. The tabulation was provided as a 723-page PDF document. We manually reviewed the document to identify all licensees having Type 01 or Type 02 licenses and ten or more NICS checks. This number was chosen to represent, very roughly, 50 firearm sales and/or redemptions per year (approximately one per week): approximately 40 transactions [10 × (365/88)], with an allowance for transactions involving multiple firearms.

We identified 9,720 licensees having ten checks or more and prepared a sampling frame containing their records from the ATF roster. These licensees accounted for 17.7 % of all retail licensees on the roster. A random sample of licensees, stratified by license type, was drawn using PROC SURVEYSAMPLE in SAS software.19 The sample size was 1,601 subjects, chosen to provide 95 % confidence intervals of ±3 % when equal (50 %) proportions of respondents provided alternate responses to questions with binary responses, and the response rate was 60 %.20 The final sample included 16.5 % of licensees in the sampling frame.

No licensees from seven states (California, Connecticut, Hawaii, New Jersey, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Virginia) were identified in the FBI tabulation as having NICS check requests. The non-represented states are all full Point of Contact (POC) states, in which firearms licensees contact a state agency, not the FBI, for NICS checks on all firearm transactions.21 These states may include the license number of the requesting licensee when submitting the NICS check request to the FBI but are not required to and frequently do not. Because the data are incomplete, the FBI generally does not include POC state transactions in their tabulations of NICS checks by licensee (personal communication, Andrew F. Clay, December 9, 2011). Retail licensees from these states accounted for 12.6 % of all retail licensees on the ATF roster.

Questionnaire Design

Questionnaire design followed recommendations made by Dillman and colleagues.20,22 The questionnaire was designed to promote readability and was limited to 38 questions on 12 pages, with a final text box for respondents to offer additional comments. A nationally recognized expert in survey research, including research on topics related to firearms, served as a consultant throughout the development of the questionnaire.

We were concerned that there might be adverse effects on the implementation of the study should its existence be disclosed prematurely and did not pre-test the questionnaire on a sample of licensed retailers. Instead, we conducted in-depth, multi-session cognitive interviews with two independent experts who had extensive knowledge of the firearms industry and its practices, and three policy development experts reviewed a draft of the questionnaire.

Some firearm licensees are named individuals, and others are corporations. Along with questions about their demographic characteristics, subjects were asked whether they themselves were the named individual to whom the questionnaire was addressed, if such an individual existed. They were asked an open-ended question about the nature of their job at the retail establishment where they worked.

Questions about the number and types of firearms sold requested data for calendar year 2010. Subjects were asked how many firearms and handguns they sold and the percentage of their overall sales that were to law enforcement personnel, women, individuals who purchased multiple firearms within five business days, over the Internet, or at gun shows. They were asked for the percentage of their handgun sales that were of handguns “priced at more than $250” (inexpensive “Saturday night specials” have new retail prices < $200, and handguns from other manufacturers are priced above $250) and for the percentage of their rifle sales that were of “tactical rifles or modern sporting rifles, such as ARs, AKs, and SKSs.”

Questions regarding denied sales and firearm trace requests, which are infrequent events, requested annual averages over the 5 years preceding the survey—as a percentage of all firearms transactions, for denials, and as occurrences per year for trace requests.

A copy of the questionnaire is available on request.

Survey Implementation

The survey was implemented followed procedures developed by Dillman and colleagues20 and used by the author in two prior surveys of individuals.23,24 Modifications recommended by Dillman and colleagues20 for establishment surveys were incorporated. The survey was conducted by mail beginning June 16, 2011. NICS check requests are least frequent during the summer,25 and the survey was conducted during this time of relatively slow licensee business activity to improve the response rate.

The survey design required up to three mailings of the questionnaire, with a reminder postcard sent to all subjects between the first and second questionnaire mailings. Taking the mailing date of the first questionnaire as day 0, the postcard was sent on day 7, and subsequent questionnaires were sent to nonrespondents on day 21 and day 42. A cash incentive—three uncirculated $1 bills—was included in the first mailing. Respondents were also offered the opportunity to request a copy of publications arising from the survey.

Each questionnaire mailing included a cover letter explaining that the purposes of the survey were “to understand better the unique perspective of firearms licensees on important social issues and the firearms business itself” and to collect “the first nationwide information on the day-to-day business experience of firearms licensees.”

Letters were addressed to the licensee when the licensee was a named person or to the “firearms manager” when the licensee was a corporation and were hand-signed by the author (as were the postcards). The letters included telephone numbers for the study team (a dedicated telephone line for queries and comments was established) and the university’s Institutional Review Board. All mailings were sent to premises addresses so as to be received by on-site managers rather than by staff at a centralized corporate headquarters. The first two questionnaires and the postcard were sent by first class mail, using commemorative stamps selected as appropriate to the project. The third questionnaire was sent by Priority Mail.

Messages left at the project’s telephone number were transcribed daily, and a log was kept. Return calls, when needed, were made by the author. Returned questionnaires were reviewed by the author within 1–2 days to identify unanticipated problems that could be corrected during survey execution. We did not attempt to contact respondents who refused to participate or indicated that they were prohibited from doing so.

Our monitoring established that the response rate for subjects affiliated with corporations with that held licenses for multiple business locations (chain stores) was lower than that for others. We sent personalized letters to the chief executive officer or chief regulatory officer of each of the 25 corporations with more than one licensee in our study sample, requesting that they authorize their store managers to participate. The author made multiple attempts to contact each corporate officer by telephone to follow up.

We also established procedures to detect and monitor discussion of the survey on the Internet. Our primary interest was in any attempt to discourage subjects from participating or to encourage collective or strategic responding. We performed searches daily on an array of relevant keywords and phrases, beginning 1 week before the first questionnaire mailing to establish a baseline level of activity.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

We performed data entry when questionnaires were received, using dual-entry procedures and automated and manual comparisons.

We determined response and refusal rates and assessed questionnaire completeness using guidelines developed by the American Association for Public Opinion Research.26 The response rate was calculated as the percentage of subjects in the sample who returned filled-out questionnaires. Complete questionnaires provided answers to >80 % of questions, partial questionnaires to 50 %–80 %, and break-off questionnaires to <50 %.

Respondents were classified by the number of questionnaires they were likely to have received prior to responding: early, response received by us no more than 2 days after the second questionnaire mailing; intermediate, response received more than 2 days after the second questionnaire mailing and no more than 2 days after the third; late, response received more than 2 days after the third questionnaire mailing.

All licensees in the sample were categorized by general business structure: The licensee was an individual named person; the licensee was a corporation, and only one establishment owned by that corporation appeared in the sample (corporate/single site); the licensee was a corporation, and multiple establishments owned by that corporation appeared in the sample (corporate/multi-site). Establishment locations were categorized by Census region.

Respondents who were known not to be owners, managers, or other senior executives (n = 21) or whose status could not be determined (n = 27) were excluded from analyses of respondents’ personal characteristics and attitudes toward firearms and the firearms business.

Continuous variables were stratified into quartiles for most analyses, to minimize effects due to outliers and clustering of responses at numbers ending in zero. The strata were chosen to produce quartiles of approximately equal size for all respondents considered together. Responses on the percentage of handguns sold that were priced at more than $250 were recoded for analysis to the percentage priced at $250 or less. The reported average annual number of trace requests was converted to a percentage of firearm sales in 2010. Strata for the two questions addressing general attitudes about firearms and crime were collapsed from five to three.

Most analyses relied on simple descriptive measures, with the significance of differences assessed using the Pearson Chi-squared test, or the Mantel–Haenszel Chi-squared test when a test for a linear association was desired. P < 0.05 was taken as the threshold for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3 for Windows.19

The UC Davis institutional review board approved this project.

Results

Response Rate

Of 1,601 subjects in the sample, 591 returned filled-out questionnaires, for a response rate of 36.9 %. Another 105 subjects (6.6 %) returned blank questionnaires (or contacted us separately) and declined to participate or stated that they were prohibited from participating. Of these, 66 (62.9 %) also returned the $3 incentive.

Of the filled-out questionnaires, 96.3 % were complete and 3.7 % were partial. There were no break-offs. The completion rates for the individual questions considered in this article were 97.8 % or higher for those pertaining to personal characteristics and 94.1 % or higher for those pertaining to business characteristics, with two exceptions—91.7 % for the total number of firearms sold and 90.2 % for the number of handguns sold.

Determinants and Timing of Response

Response rates for gun dealers and pawnbrokers were similar—37.2 % and 36.3 %, respectively, p = 0.75. The response rate for subjects who were employed by corporate/multi-site licensees (19.7 %) was less than half that for subjects employed by corporate/single site licensees (41.1 %) or subjects employed by licensees who were named individual persons (40.5 %), p < 0.0001. Response rates did not differ significantly with subjects’ location (Northeast, 45.5 %; South, 35.0 %; Midwest, 41.3 %; West, 35.0 %; p = 0.11).

Most respondents returned questionnaires early (383, 64.8 %); there were 136 (23.0 %) intermediate and 72 (12.2 %) late respondents. Respondents affiliated with corporate/multi-site licensees returned their questionnaires later than others did (8.6 % of early respondents, 10.3 % of intermediate respondents, 16.7 % of late respondents, p = 0.01, Appendix Table 3), and there was a similar but non-significant trend for pawnbrokers (32.6 % of early respondents, 40.4 % of intermediate respondents, 43.1 % of late respondents, p = 0.10) With these exceptions, early, intermediate, and late respondents were similar.

Table 3.

Personal and establishment characteristics by business structure

| Characteristic | Licensee business structure | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal licensee | Corporate/single | Corporate/multiple | ||

| Personal characteristics | ||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 57 (49–64) | 51 (41–60) | 43 (37–48) | <0.0001 |

| Male, n (%) | 221 (93.3) | 230 (89.2) | 30 (66.7) | <0.0001 |

| White, n (%) | 230 (97.5) | 251 (98.1) | 43 (95.6) | 0.59 |

| Non-Hispanic, % | 233 (99.2) | 252 (98.1) | 42 (93.3) | 0.03 |

| Timing of response, n (%) | ||||

| Early | 175 (71.1) | 164 (61.1) | 33 (55.9) | 0.01 |

| Intermediate | 53 (21.5) | 69 (24.2) | 14 (23.7) | |

| Late | 18 (7.3) | 42 (14.7) | 12 (16.7) | |

| Establishment characteristics | ||||

| Licensee status | ||||

| Dealer (type 01) | 172 (69.9) | 159 (55.8) | 49 (83.1) | <0.0001 |

| Pawnbroker (type 02) | 74 (30.1) | 126 (44.2) | 10 (17.0) | |

| Nature of business premises, n (%) | ||||

| Residence | 59 (24.0) | 10 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 |

| Gun store | 66 (26.8) | 64 (22.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Pawnshop | 63 (25.6) | 109 (38.3) | 11 (18.6) | |

| Sporting goods store | 25 (10.2) | 49 (17.2) | 4 (15.3) | |

| General retail store | 19 (7.7) | 37 (13.0) | 39 (66.1) | |

| Gunsmith shop | 9 (3.4) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Gun shows, primarily or only | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Othera/unknown | 4 (1.6) | 13 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Sales, median (IQR) | 150 (90–368) | 250 (100–500) | 250 (100–365) | 0.001 |

| Sales, stratified, n (%) | 0.0002 | |||

| <100 | 59 (26.5) | 50 (18.9) | 8 (14.5) | |

| 100–199 | 63 (28.4) | 52 (19.7) | 10 (18.2) | |

| 200–499 | 56 (25.2) | 74 (28.0) | 26 (47.3) | |

| 500+ | 44 (19.8) | 88 (33.3) | 11 (20.0) | |

| Handgun sales as % of sales, median (IQR) | 50 (30.5–63.1) | 50.0 (30.0–66.7) | 0 (0–0) | <0.0001 |

| Handgun sales as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| 0–24 | 41 (19.0) | 48 (18.8) | 44 (84.6) | |

| 25–49 | 54 (25.0) | 65 (25.5) | 3 (5.8) | |

| 50–74 | 90 (41.7) | 105 (41.2) | 1 (1.9) | |

| 75+ | 312 (14.4) | 37 (14.5) | 4 (7.7) | |

| Inexpensive handgun sales as % of handgun sales, median (IQR) | 18.7 (5.0–40.0) | 22.5 (5.0–50.0) | 100 (60–100) | <0.0001 |

| Inexpensive handgun sales as % of handgun sales, n (%) | ||||

| 0–9 | 70 (30.4) | 119 (33.0) | 1 (2.0) | <0.0001 |

| 10–24 | 59 (25.7) | 83 (23.0) | 5 (10.0) | |

| 25–49 | 45 (19.6) | 50 (13.9) | 4 (8.0) | |

| 50+ | 56 (24.4) | 109 (30.2) | 40 (80.0) | |

| “Tactical or modern sporting” rifle sales as % of rifle sales, median (IQR) | 5 (2–20) | 5 (2–20) | 0 (0–1) | <0.0001 |

| “Tactical or modern sporting” rifle sales as % of rifle sales, stratified, n (%) | ||||

| 0–1 | 48 (21.2) | 61 (22.1) | 40 (75.5) | <0.0001 |

| 2–5 | 68 (30.1) | 83 (30.1) | 6 (11.3) | |

| 6–19 | 51 (22.6) | 62 (22.5) | 3 (5.7) | |

| 20+ | 59 (26.1) | 70 (25.4) | 4 (7.8) | |

| Sales to law enforcement as % of sales, median (IQR) | 5 (1–10) | 5 (1–10) | 3 (0–10) | 0.32 |

| Sales to law enforcement as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | 0.63 | |||

| <1 | 48 (20.2) | 46 (16.6) | 15 (26.3) | |

| 1–4 | 64 (26.9) | 83 (29.9) | 17 (29.8) | |

| 5–9 | 54 (22.7) | 64 (23.0) | 9 (15.8) | |

| 10+ | 72 (30.3) | 85 (30.6) | 16 (28.1) | |

| Sales to women as % of sales, median (IQR) | 10 (5–20) | 15 (5–22.5) | 15 (5–25) | 0.29 |

| Sales to women as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | ||||

| 0–5 | 77 (2.6) | 80 (28.9) | 15 (25.4) | 0.85 |

| 6–10 | 51 (21.6) | 57 (20.4) | 14 (23.7) | |

| 11–24 | 51 (21.6) | 73 (26.2) | 14 (23.7) | |

| 25+ | 57 (24.2) | 69 (24.7) | 16 (27.1) | |

| Multiple sales as % of sales, median (IQR) | 2 (1–5) | 1 (1–5) | 1 (0–3) | 0.13 |

| Multiple sales as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | 0.20 | |||

| <1 | 65 (26.4) | 67 (23.5) | 24 (40.7) | |

| 1 | 59 (23.4) | 81 (28.4) | 12 (20.3) | |

| 2–4 | 57 (23.1) | 66 (23.2) | 10 (17.0) | |

| 5+ | 65 (26.4) | 71 (24.9) | 13 (22.0) | |

| Denied sales as % of sales, median (IQR) | 1 (0.5–2) | 1 (1–5) | 5 (1–10) | <0.0001 |

| Denied sales as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | ||||

| <1 | 70 (29.4) | 54 (19.6) | 7 (13.0) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 68 (38.6) | 4 (34.2) | 9 (16.7) | |

| 2–4 | 55 (23.1) | 53 (19.2) | 6 (11.1) | |

| 5+ | 45 (18.9) | 74 (26.9) | 32 (59.3) | |

| Trace requests as % of sales, median (IQR) | 0.5 (0.0–1.7) | 0.7 (0.1–2) | 1.0 (0.3–2.6) | 0.08 |

| Trace requests as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 64 (29.1) | 58 (22.6) | 11 (20.4) | 0.38 |

| >0, ≤0.5 | 51 (23.2) | 59 (23.0) | 9 (16.7) | |

| >0.5, <2 | 52 (23.6) | 72 (28.0) | 15 (27.8) | |

| 2+ | 53 (24.1) | 68 (26.5) | 19 (35.2) | |

aOther includes five auction facilities, four shooting clubs/ranges, one firearm distributor, one police equipment store, one law office, one transmission shop, one business office

Personal Characteristics

Respondents had a median age of 54 years [interquartile range (IQR), 43–61 years]; 89 % were male; 97.6 % were White, and 98.1 % were non-Hispanic. Except for age, there was little variation between gun dealers and pawnbrokers (Table 1). The 230 respondents who held federal firearms licenses themselves as named individuals were older than others (median age 57 years, IQR 49–64 years; for others, median 49, IQR 40–59 years; p < 0.0001) (Appendix Table 3). Only 21 such respondents (9.1 %) were less than 40 years of age. The median duration of licensure for these 230 licensees was 18 years (IQR, 6–26 years). Only 19.1 % of this group had been licensed for less than 5 years; 18.3 % had been licensed for 30 years or more.

Table 1.

Personal characteristics and attitudes toward firearms

| Characteristic | Nature of retailer | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Dealer | Pawnbroker | ||

| Age, median, (IQR) | 54 (43–61) | 54 (45–62) | 50 (41–60) | 0.02 |

| Male, n (%) | 482 (89.1) | 310 (88.6) | 172 (90.1) | 0.60 |

| White, n (%) | 525 (97.6) | 337 (97.1) | 188 (98.4) | 0.34 |

| Non-Hispanic, % | 528 (98.1) | 343 (98.9) | 185 (96.9) | 0.10 |

| “Private ownership of guns is essential for a free society,” n (%) | ||||

| Agree | 518 (96.3) | 341 (97.4) | 177 (94.2) | 0.02 |

| Neutral | 11 (2.0) | 7 (2.0) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Disagree | 9 (1.7) | 2 (0.6) | 7 (3.7) | |

| “It is too easy for criminals to get guns in this country,” n (%) | ||||

| Agree | 292 (54.9) | 179 (51.7) | 113 (60.8) | 0.09 |

| Neutral | 121 (22.7) | 81 (23.4) | 40 (21.5) | |

| Disagree | 119 (22.4) | 86 (24.9) | 33 (17.7) | |

Attitudes Toward Firearms and the Firearms Business

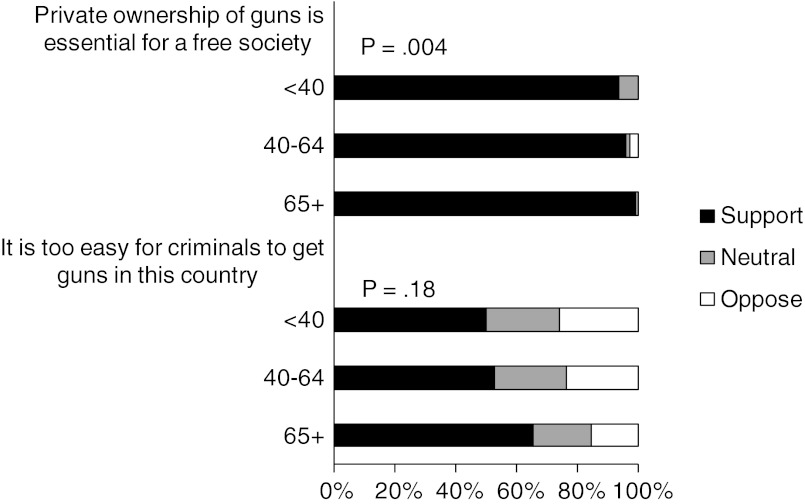

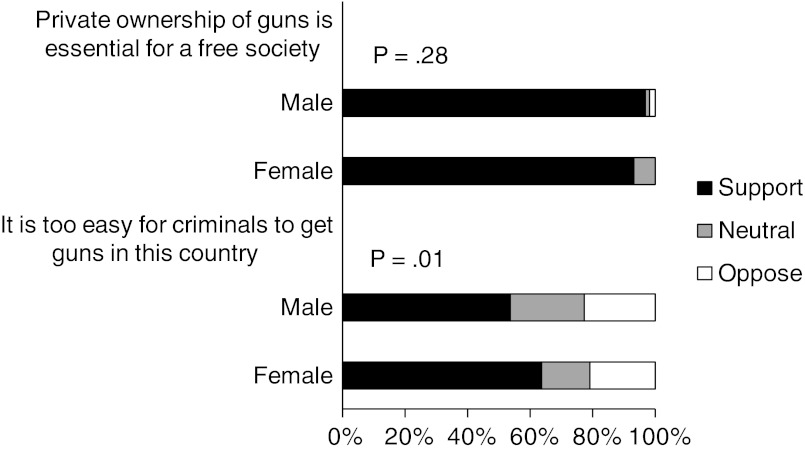

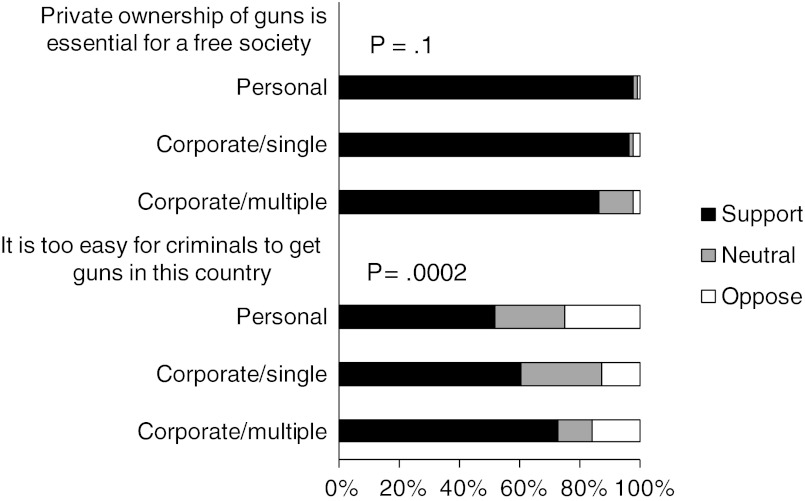

A large majority (518 respondents, 96.3 %) agreed that “private ownership of guns is essential for a free society,” and there was little variation among subgroups of respondents (Table 1, Appendix Figures 3, 4, and 5). Just over half (292 respondents, 54.9 %) believed that “it is too easy for criminals to get guns in this country.” Agreement varied little with age and sex, was somewhat less common among gun dealers than pawnbrokers, and was more common among respondents from corporate/multi-site licensees than others (Table 1, Appendix Figures 3, 4, and 5).

Figure 3.

General attitudes towards firearms by age.

Figure 4.

General attitudes towards firearms by sex.

Figure 5.

General attitudes towards firearms by licensee business structure.

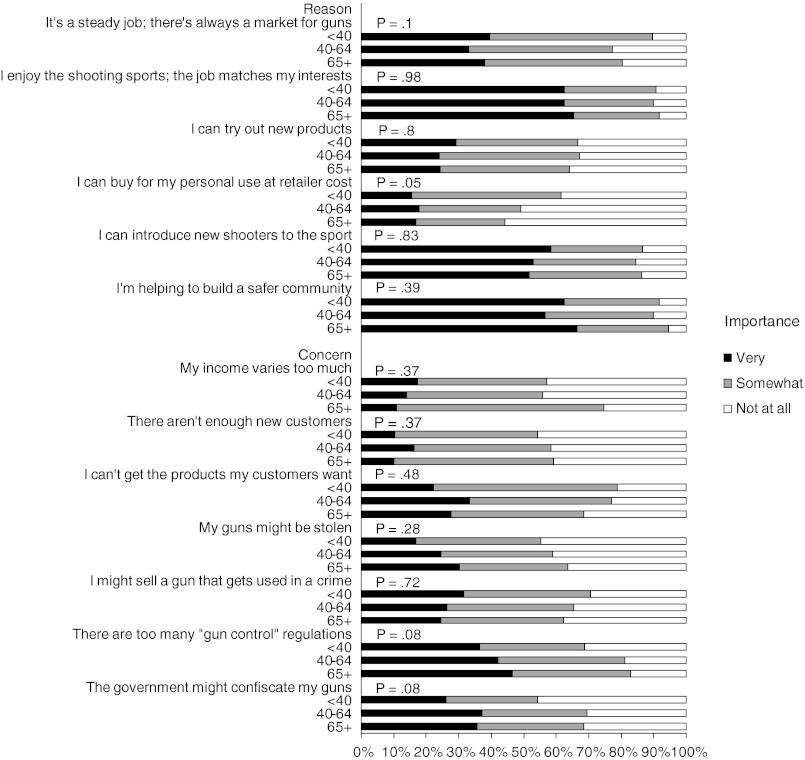

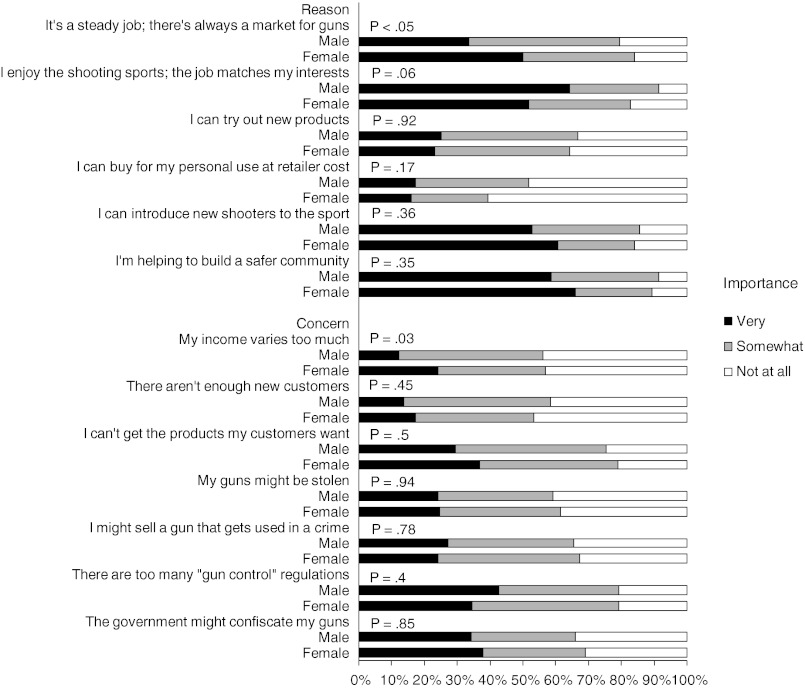

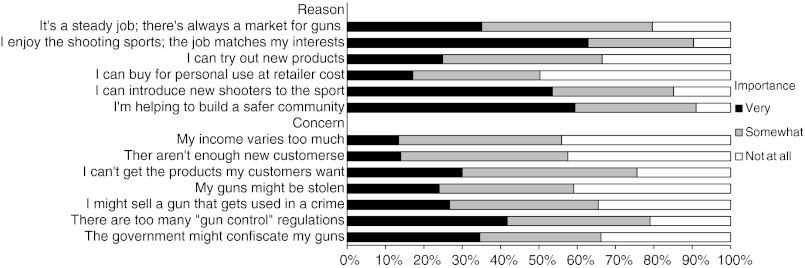

A match between the job and a personal interest in the shooting sports was most important among reasons for working as a firearms retailer (Figure 1). Respondents were more likely to cite as important such other-directed items as “introduc[ing] new shooters to the sport” and “helping to build a safer community” than personal material benefits (Figure 1). Chief concerns about the business were that “there are too many ‘gun control’ regulations” and that “the government might confiscate my guns” (Figure 1). The percentages of respondents listing confiscation as very important (34.6 %) and not at all important (33.8 %) were essentially equal.

Figure 1.

Reasons for and concerns about working in the firearms industry. Items are listed in the order in which they are presented in the questionnaire.

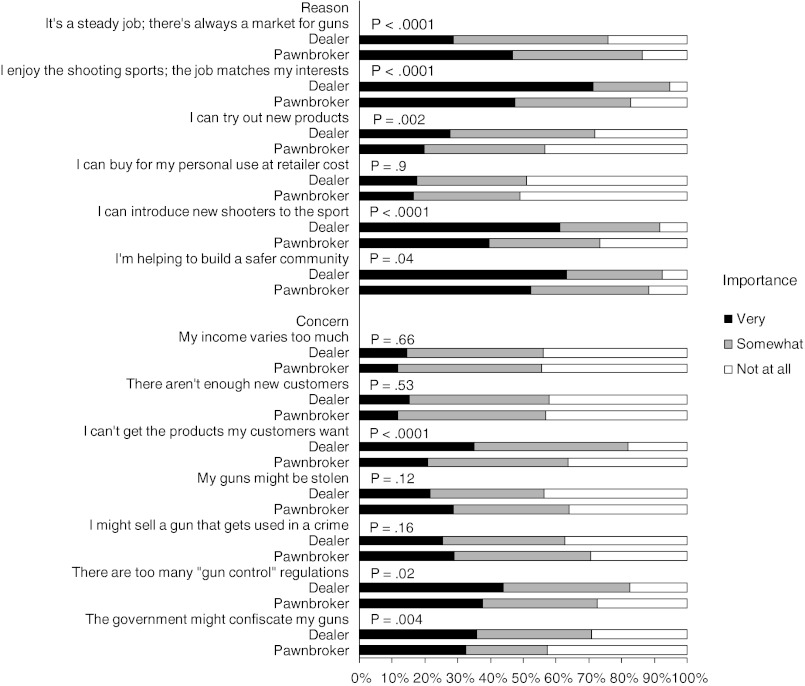

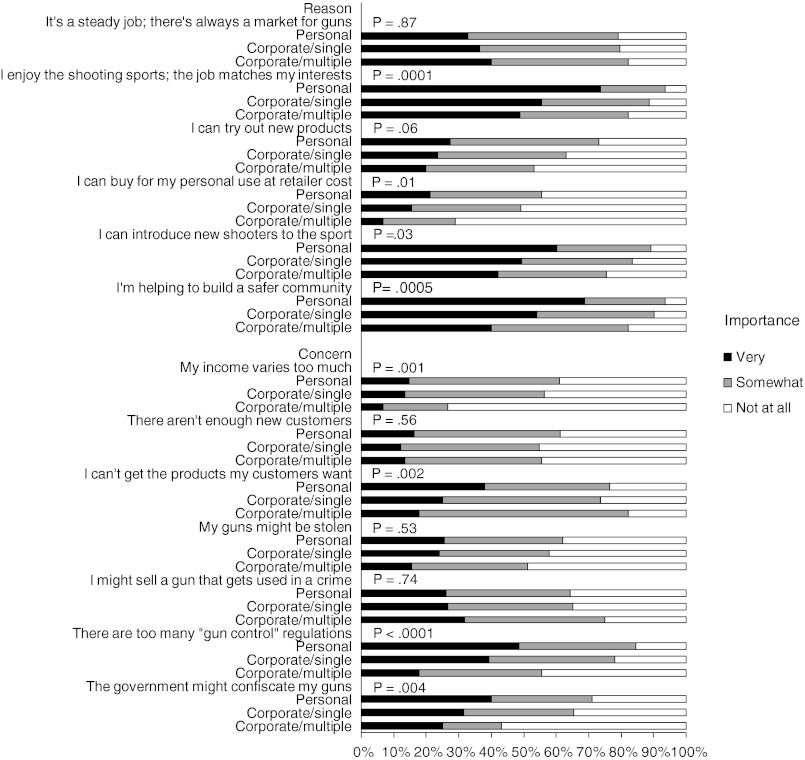

Women were more likely than men to cite a steady job as very important and less likely to cite a personal interest in the shooting sports; there was otherwise little difference associated with respondents’ age or sex (Appendix Figures 6 and 7). The rank order by importance of reasons for working in the business and concerns about it varied little between gun dealers and pawnbrokers, but dealers were more likely than pawnbrokers to rate most items as very important (Appendix Figure 8). Pawnbrokers were more likely to rate concern for confiscation as not at all important (42.6 %) than as very important (32.5 %). Respondents from corporate/multi-site licensees were less likely than others to rate most items as important (Appendix Figure 9).

Figure 6.

Reasons for and concerns about working in the firearms industry by age.

Figure 7.

Reasons for and concerns about working in the firearms industry by sex.

Figure 8.

Reasons for and concerns about working in the firearms industry by licensee type.

Figure 9.

Reasons for and concerns about working in the firearms industry by licensee business structure.

Establishment Characteristics and Firearm Sales

Results in this and the following sections include data provided by 48 respondents who were not known to be owners or senior executives.

Most respondents were gun dealers (380, 64.3 %), with significant variation by region; dealers accounted for 55.8 % of respondents in the South, 63.4 % in the West, 78.1 % in the Midwest, and 100 % in the Northeast (p < 0.0001). Dealers, but not pawnbrokers, maintained a variety of business premises (Table 2). Residential dealers accounted for 25.6 % of all dealers in the Midwest, 17.0 % in the West, 14.6 % in the South, and 6.7 % in the Northeast (p = 0.06).

Table 2.

Establishment characteristics, firearm sales, denied sales, and firearm trace requests

| Characteristic | Retail establishment type | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Dealer | Pawnbroker | ||

| Nature of business premises, n (%) | ||||

| Residence | 69 (11.7) | 69 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 |

| Gun store | 130 (22.0) | 109 (28.7) | 21 (10.0) | |

| Pawnshop | 184 (31.1) | 2 (0.5) | 182 (86.3) | |

| Sporting goods store | 83 (14.0) | 78 (20.5) | 5 (2.4) | |

| General retail store | 95 (16.1) | 92 (24.2) | 3 (1.4) | |

| Gunsmith shop | 11 (1.9) | 11 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Gun shows, primarily or only | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Internet, primarily or only | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Othera/unknown | 15 (2.5) | 15 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Sales, median (IQR) | 200 (100–500) | 200 (100–500) | 200 (100–500) | 0.43 |

| Sales, stratified, n (%) | 0.50 | |||

| <100 | 117 (21.6) | 81 (23.3) | 36 (18.6) | |

| 100–199 | 125 (23.1) | 75 (21.6) | 50 (25.8) | |

| 200–499 | 157 (29.0) | 102 (29.3) | 55 (28.4) | |

| 500+ | 143 (26.4) | 90 (25.9) | 53 (27.3) | |

| Handgun sales as % of sales, median (IQR) | 50 (22.7–63.6) | 47.3 (15.5–65.8) | 50 (33.3–62.5) | 0.04 |

| Handgun sales as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| 0–24 | 133 (25.4) | 107 (31.8) | 26 (14.0) | |

| 25–49 | 122 (23.3) | 67 (19.9) | 55 (29.6) | |

| 50–74 | 196 (37.5) | 109 (32.3) | 87 (46.8) | |

| 75+ | 72 (13.8) | 54 (16.0) | 18 (9.7) | |

| Inexpensive handgun sales as % of handgun sales, median (IQR) | 25 (5–50) | 20 (5–50) | 30 (10–50) | 0.0005 |

| Inexpensive handgun sales as % of handgun sales, n (%) | ||||

| 0–9 | 145 (26.0) | 119 (33.0) | 26 (13.3) | <0.0001 |

| 10–24 | 129 (23.2) | 83 (23.0) | 46 (23.5) | |

| 25–49 | 102 (18.3) | 50 (13.9) | 52 (26.5) | |

| 50+ | 181 (32.5) | 109 (30.2) | 72 (36.7) | |

| “Tactical or modern sporting” rifle sales as % of rifle sales, median (IQR) | 5 (1–15) | 5 (1–20) | 5 (2–10) | 0.61 |

| “Tactical or modern sporting” rifle sales as % of rifle sales, stratified, n (%) | ||||

| 0–1 | 149 (26.8) | 108 (30.3) | 41 (20.6) | <0.0001 |

| 2–5 | 157 (28.4) | 90 (25.2) | 67 (33.7) | |

| 6–19 | 117 (21.0) | 60 (16.8) | 57 (28.6) | |

| 20+ | 133 (23.9) | 99 (27.7) | 34 (17.1) | |

| Sales to law enforcement as % of sales, median (IQR) | 5 (1–10) | 5 (1–10) | 5 (1–10) | 0.73 |

| Sales to law enforcement as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | 0.72 | |||

| <1 | 109 (19.0) | 71 (19.1) | 38 (18.7) | |

| 1–4 | 165 (28.8) | 105 (28.3) | 60 (29.6) | |

| 5–9 | 127 (22.1) | 78 (21.0) | 49 (24.1) | |

| 10+ | 173 (30.1) | 117 (31.5) | 56 (27.6) | |

| Sales to women as % of sales, median (IQR) | 10 (5–22.5) | 10 (5–20) | 15 (6–25) | 0.007 |

| Sales to women as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | ||||

| 0–5 | 172 (29.9) | 122 (32.7) | 50 (24.8) | 0.09 |

| 6–10 | 122 (21.2) | 80 (21.5) | 42 (20.8) | |

| 11–24 | 139 (24.2) | 90 (24.1) | 49 (24.3) | |

| 25+ | 142 (24.7) | 81 (21.7) | 61 (30.2) | |

| Multiple sales as % of sales, median (IQR) | 1 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) | 1 (1–4) | 0.46 |

| Multiple sales as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | 0.74 | |||

| <1 | 157 (26.6) | 98 (25.8) | 59 (28.0) | |

| 1 | 152 (25.7) | 95 (25.0) | 57 (27.0) | |

| 2–4 | 133 (22.5) | 86 (22.6) | 47 (22.3) | |

| 5+ | 149 (25.2) | 101 (26.6) | 48 (22.8) | |

| Denied sales as % of sales, median (IQR) | 1 (1–5) | 1 (0.5–3) | 2 (1–5) | <0.0001 |

| Denied sales as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | ||||

| <1 | 131 (23.1) | 106 (28.9) | 25 (12.6) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 171 (30.1) | 117 (31.6) | 54 (27.3) | |

| 2–4 | 114 (20.1) | 68 (18.4) | 46 (23.2) | |

| 5+ | 152 (26.8) | 79 (21.4) | 73 (36.9) | |

| Trace requests as % of sales, median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.002–2) | 0.5 (0–2) | 0.75 (0.25–2.3) | 0.01 |

| Trace requests as % of sales, stratified, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 133 (25.0) | 103 (29.9) | 30 (16.0) | 0.004 |

| >0, ≤ 0.5 | 119 (22.4) | 71 (20.6) | 48 (25.7) | |

| >0.5, <2 | 139 (26.1) | 81 (23.5) | 58 (31.0) | |

| 2+ | 141 (26.5) | 90 (26.1) | 51 (27.3) | |

aOther includes five auction facilities, four shooting clubs/ranges, one firearm distributor, one police equipment store, one law office, one transmission shop, one business office

Median sales volume was 200 firearms in the year preceding the survey, with no significant difference between dealers and pawnbrokers (Table 2). Handguns accounted for approximately half of firearm sales in both groups (Table 2); dealers were more likely than pawnbrokers to report either <25 % or ≥75 % of sales to be of handguns (p < 0.0001).

Inexpensive handguns made up a larger proportion of all handgun sales for pawnbrokers than for dealers (Table 2). There was a tendency among dealers to sell few inexpensive handguns (<10 %, 33.0 % of dealers) or many (≥50 % or more, 30.2 % of dealers). Among pawnbrokers, a plurality reported that sales of inexpensive handguns accounted for ≥50 % of handgun sales. Tactical or modern sporting rifles accounted for a median of 5 % of rifle sales among both dealers and pawnbrokers. Again, as compared with pawnbrokers, dealers tended to sell few such firearms or many (p < 0.0001) (Table 2).

Most respondents (472, 82.2 %) reported sales to law enforcement officers or agencies, with little variation between dealers and pawnbrokers (Table 2), and 15 reported that law enforcement clients accounted for 50 % or more of their total firearm sales. All but five respondents reported sales to women, which were more frequent and accounted for a larger proportion of total sales among pawnbrokers than among dealers (Table 2).

Most respondents (458, 80 %) reported sales to clients who bought more than one firearm in five business days, but such sales were not common (Table 2) and were distributed similarly for dealers and pawnbrokers.

Sales on the Internet were reported by 164 respondents (28.3 %), among whom Internet sales accounted for a slightly higher percentage of all sales for dealers (median 6 %, IQR 3 %–33 %) than for pawnbrokers (median 5 %, IQR 1.5 %–10 %) (p = 0.01). Twenty-two respondents, 19 of whom were dealers, reported that ≥50 % of their firearm sales were made on the Internet.

Only 83 respondents (14.3 %) reported selling any firearms at gun shows. Among these, gun show sales accounted for a higher percentage of all sales for dealers (median 35 %, IQR 5 %–60 %) than for pawnbrokers (median 5 %, IQR 2 %–10 %) (p = 0.002). Twenty-six respondents, all but one of whom were dealers, reported that ≥50 % of their firearm sales were made at gun shows.

Corporate/multi-site licensees were more likely than others to be firearms dealers, sold fewer handguns, and sold relatively more inexpensive handguns and relatively fewer tactical or modern sporting rifles (Appendix Table 3).

Denied Sales and Firearm Traces

Sales that were denied after prospective purchasers failed NICS checks accounted for approximately 1 % of firearm sales overall (median 1 %, IQR 1 %–5 %); only 65 (11.4 %) respondents reported having no denied sales over the 5 years preceding the survey. Denials occurred more frequently among pawnbrokers than among dealers (Table 2). Respondents reported receiving firearm trace requests, again for the 5 years prior to the survey, at a frequency equaling less than 1 % of their annual firearm sales (median 0.7 %, IQR 0.002 – 2 %), and 133 (25 %) respondents received no trace requests.

Firearm traces were also more frequent among pawnbrokers than among dealers (Table 2). Trace frequency was directly associated with the percentage of firearm sales involving handguns (p = 0.007), inexpensive handguns (p = 0.003), and female purchasers (p = 0.0008) (Appendix Table 4). Both denials and traces were more common among corporate/multi-site licensees than others (Appendix Table 3).

Table 4.

Relationship between frequency of firearm trace requests and characteristics of firearm sales

| Sales type | Trace requests as a % of overall sales volume | Pa value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | >0, ≤0.5 | > 0.5, <2 | 2+ | ||

| Handgun sales as % of sales, n (%) | 0.007 | ||||

| 0–24 | 47 (35.3) | 23 (18.8) | 28 (21.1) | 33 (24.8) | |

| 25–49 | 36 (29.8) | 27 (22.3) | 32 (26.5) | 26 (21.5) | |

| 50–74 | 30 (15.4) | 53 (27.2) | 56 (28.7) | 56 (28.7) | |

| 75+ | 17 (24.6) | 11 (15.9) | 18 (26.1) | 23 (33.3) | |

| Inexpensive handgun sales as % of handgun sales, n (%) | 0.003 | ||||

| 0–9 | 45 (33.3) | 35 (25.9) | 28 (20.7) | 27 (20.0) | |

| 10–24 | 26 (21.7) | 31 (25.8) | 34 (28.3) | 29 (24.2) | |

| 25–49 | 16 (17.0) | 23 (24.5) | 27 (28.7) | 28 (29.8) | |

| 50+ | 43 (25.2) | 28 (16.4) | 45 (26.3) | 55 (32.2) | |

| Sales to women as % of sales, n (%) | |||||

| 0–5 | 58 (37.9) | 30 (19.6) | 35 (22.9) | 30 (19.6) | 0.0008 |

| 6–10 | 25 (21.7) | 27 (23.5) | 29 (25.2) | 34 (29.6) | |

| 11–24 | 25 (19.1) | 30 (22.9) | 41 (31.3) | 35 (26.7) | |

| 25+ | 25 (19.2) | 31 (23.9) | 33 (25.4) | 41 (31.5) | |

aMantel–Haenszel Chi-squared

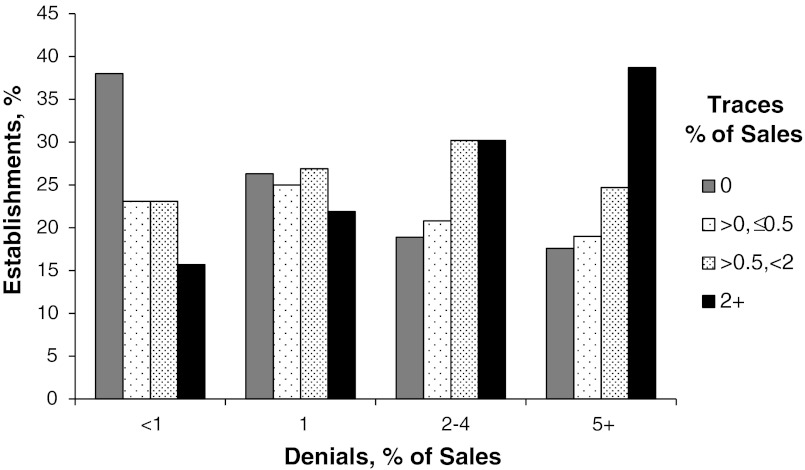

Denied sales and trace requests varied in parallel (p < 0.0001) (Figure 2). Among establishments ranking in the lowest quartile for frequency of denied sales (<1 % of sales), 38.0 % also ranked in the lowest quartile for trace requests (0 over 5 years), and only 15.7 % ranked in the highest quartile (≥2 per year). Among those ranking in the highest quartile for frequency of denied sales (≥5 % of sales), only 17.6 % ranked in the lowest quartile for trace requests, and 38.7 % ranked in the highest.

Figure 2.

Association between frequency of denied sales and sales of firearms that are subsequently traced by law enforcement (Mantel–Haenszel Chi-squared p < 0.0001).

Discussion

To our knowledge, these are the first systematic data on federally licensed firearms retailers and their retail establishments to have been provided by the retailers themselves. The respondents were demographically homogenous: older, White, non-Hispanic, and male; this was particularly true of those who were licensed themselves as individuals. Respondents agreed that firearms are “essential for a free society,” but most also believed that it is too easy for criminals to get them. They were greatly concerned about government regulation and intrusion. Differences between gun dealers and pawnbrokers on these measures were common but generally modest.

Overall, fewer than 30 % of gun dealers operated out of specialized gun stores or gunsmith shops. Pawnbrokers were much more common in the South than elsewhere. A plurality of dealers in the Midwest operated out of a residence, which was unexpected in this population selected for relatively frequent firearm sales. In a California field study of licensees with ≥50 handguns sales annually, 5 % were located at residences.12 A 1998 ATF field study found 56 % of licensees to have a residential business premises, but 31 % of subjects in that study sold no firearms.27

Dealers may be more likely than pawnbrokers to specialize; they appeared disproportionately in the highest and lowest quartiles among establishments ranked by the percentage of sales accounted for by handguns, inexpensive handguns, and tactical rifles. Pawnbrokers figured prominently in sales of inexpensive handguns and sales to women; dealers predominated in sales on the Internet and at gun shows.

The results provided by our respondents are consistent with data from independent sources where such data are available. In 2009, the most recent year for which information is available, 1.4 % of firearm purchase and permit applications were denied nationwide.18 The 1 % median for our respondents is comparable (and the average, 3.4 %, is higher). Prior studies have also yielded results largely consistent with the respondents’ estimate that trace requests occur at an annual rate roughly equal to 1 % of firearm sales.5,11,12,15,28,29 The results cannot be compared directly, however, because of differences in methods and tracing practices at study sites.

The direct relationship between frequency of denied sales and sales of firearms that are later traced, both thought to represent a clientele that is at increased risk for subsequent criminal activity, has been observed in several studies.5,11,12,15 Prior studies have also documented the associations seen here between firearm traces and licensure as a pawnbroker, sales of handguns and of inexpensive handguns, and sales to women—the last interpreted as possibly representing an increased incidence of surrogate (straw) purchases.11,12,15,27

Limitations

In framing this study, we determined to survey only federally licensed gun dealers and pawnbrokers who actually sold firearms and in more than token numbers. As a practical matter, our decision to restrict eligibility to licensees with NICS checks above a specified threshold excluded licensees from seven states because counts of NICS checks were not available for those states. Licensees from so-called partial POC states, in which licensees contact a state agency for some NICS checks and the FBI for others, are likely to be under-represented because not all of their NICS check requests are tabulated by the FBI. Licensees from Brady alternative states may be under-represented because not all of their sales require NICS checks.

Conversely, some low-volume pawnbrokers may have been misclassified as eligible, since pawnbrokers request NICS checks for pawn redemptions as well as firearm sales, and the transactions are not distinguished in the FBI’s tabulations. Misclassification would have occurred if a pawnbroker met the eligibility criterion based on NICS checks for sales and redemptions together but would not have done so for sales alone. Since pawnbrokers were more prevalent in the South than elsewhere, this would also have led to over-representation of licensees from that part of the country. For all these reasons, our results cannot be considered nationally representative.

Our overall response rate was 36.9 %. Dillman and colleagues, who developed the survey methods we used,20 achieved an average response rate of 38.8 % (author’s calculation) in five business surveys having questionnaires the same length as ours and requiring materials to be addressed generically to an owner/manager, as was necessary for 62 % of our subjects.30 A recent review of business surveys using a variety of traditional and adapted techniques found that response rates generally ranged between 28 % and 45 %.31 The questionnaire and individual question completion rates in our survey were high, including those for questions soliciting potentially sensitive business information such as numbers of firearms sold. This suggests that the internal validity of the data is high.

The differential response rate by business type is perhaps a greater limitation; corporate/multi-site licensees are underrepresented in our data. A lower response rate from large corporations is common to business surveys, in part because there may be no named individual to receive the survey materials.20,30 These subjects were also most frequent among our late respondents, validating our expenditure of additional resources to acquire them.32,33

The representativeness of results for these subjects is questionable. For example, corporate/multi-site licensees were found to sell handguns much less frequently than others but also, paradoxically, to sell disproportionate numbers of inexpensive handguns. These findings result from the fact that 57.6 % of respondents in this group are affiliated with a single large retail corporation that generally does not sell handguns; of the remainder, 40 % are pawnbrokers.

Our results may have been affected by external factors, chief among them being efforts to deter subjects from participating. Two days after the first questionnaire was mailed, Larry Keane, general counsel of the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF), posted a notice at the organization’s Web site “strongly discouraging retailers from participating in this survey.”34 He included the project’s telephone number and E-mail address and encouraged “all sportsmen, gun owners and firearms enthusiasts to contact [the investigators] to politely express their objections to this agenda-driven, anti-gun research.” NSSF also posted the questionnaire and cover letter. The text of Keane’s announcement was revised a few days later to “urg[e] extreme caution should retailers decide to participate.” Reprints of the original and modified text and links to the post appeared on other firearm industry and consumer Web sites. The National Rifle Association (NRA) issued a notice to retailers at its Web site on June 29, “recommend[ing] that you do not respond to the survey.”35 The organization also sent its notice as a personalized E-mail, apparently to the organization’s entire membership.36 After the second and third preplanned questionnaire mailings, Keane posted statements at NSSF’s Web site claiming credit for them.37,38 “[I]t appears that retailers have heeded NSSF’s caution,” the first of these read in part. “Apparently Dr. Wintemute has been forced to send out repeat invitations to America’s firearms retailers.”37 These statements were also re-posted at other Web sites.

Current events may also have played a role. The survey was conducted during months when there was much media coverage of ATF’s Operation Fast and Furious, which may have allowed organized criminal gangs in this country and Mexico to obtain more than 2,000 firearms. By coincidence, 1 week before the first questionnaire was mailed, a study by our group linking firearm ownership to risk behaviors involving alcohol was published online.39 It was the subject of national media attention and discussion at firearm-related Web sites.

The effect of these external factors appears to have been limited. Our response rate is comparable to those for similar surveys on unrelated topics, as discussed. More specifically, we can quantify the response to the NSSF/NRA communications, which encouraged presumably millions of recipients to contact us and object to the survey. During the time the survey was conducted, we received 47 E-mail messages or telephone calls related to our research, other than those from survey subjects. Twenty commented negatively on the survey, two on the firearms and alcohol study,39 and 22 on our research in general. The timing of the last group is such that it is reasonable to infer that these were in response to the NSSF/NRA communications. Another three were positive—two from persons who forwarded the NRA E-mail and one from a prospective donor.

The NSSF/NRA communications required some time to be widely disseminated and read. Their effect, if any, on our response rate would therefore be expected to grow over time, and this would have been reflected in an unusually rapid attenuation of our response rate. This did not occur. Our time distribution for responses—64.8 % early, 23.0 % intermediate, 12.2 % late—is strikingly close to that seen in a similarly conducted survey40 of Medicare beneficiaries—66 % early, 22 % intermediate, 12 % late (author’s calculations)—and is not atypical for such surveys generally.20

It is certainly possible that the NSSF/NRA efforts increased response bias in our data, subjects having more moderate views being perhaps less affected by efforts to prevent them from participating. But there may also be a bias toward less moderate responses in the data, for separate reasons. The response rate from corporate/multi-site licensees was half that for other subjects, and licensees in this group who did respond were more likely than others to agree that “it is too easy for criminals to get guns in this country” and less likely (although the results were not statistically significant) to agree that “private ownership of guns is essential for a free society.” Since it is a common occurrence,20,30 the lower response rate from corporate/multi-site licensees may well have occurred unrelated to the NRA/NSSF communications.

Acknowledgments

We are especially grateful to the retailers who participated in the survey, many of whom provided additional helpful comments. Barbara Claire, Vanessa McHenry, and Mona Wright provided expert technical assistance throughout the project. Dr. Tom Smith served as a consultant for the development of the survey questionnaire and gave extensive input. Jeri Bonavia, Kristen Rand, and Josh Sugarmann provided helpful reviews of a draft questionnaire.

Project support

This project was supported in part by a grant from The California Wellness Foundation. Initial planning was also supported in part by a grant from the Joyce Foundation.

Appendix: Supplemental Tables and Figures

Footnotes

Submitted to the Journal of Urban Health on May 22, 2012.

References

- 1.Truman JL, Rand MR. Criminal victimization, 2009. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010. NCJ 231327.

- 2.Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: preliminary data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;60(4):1–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Following the gun: enforcing federal laws against firearms traffickers. Washington, DC: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braga AA, Cook PJ, Kennedy DM, Moore MH. The illegal supply of firearms. In: Tonry M, editor. Crime and justice: a review of research. Vol 29. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London; 2002. pp. 319–352. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierce GL, Braga AA, Hyatt RRJ, Koper CS. Characteristics and dynamics of illegal firearms markets: implications for a supply-side enforcement strategy. Justice Q. 2004;21(2):391–422. doi: 10.1080/07418820400095851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koper CS. Federal legislation and gun markets: how much have recent reforms of the federal firearms licensing system reduced criminal gun suppliers? Criminol Public Pol. 2002;1(2):151–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2002.tb00082.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorenson SB, Vittes K. Buying a handgun for someone else: firearm dealer willingness to sell. Inj Prev. 2003;9(2):147–150. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webster D, Vernick J, Bulzacchelli M. Effects of a gun dealer's change in sales practices on the supply of guns to criminals. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):778–787. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9073-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webster D, Bulzacchelli M, Zeoli A, Vernick J. Effects of undercover police stings of gun dealers on the supply of new guns to criminals. Inj Prev. 2006;12(4):225–230. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.012120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webster DW, Vernick JS, Bulzacchelli MT, Vittes KA. Temporal association between federal gun laws and the diversion of guns to criminals in Milwaukee. J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):87–97. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9639-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wintemute GJ, Cook P, Wright MA. Risk factors among handgun retailers for frequent and disproportionate sales of guns used in violent and firearm related crimes. Inj Prev. 2005;11(6):357–363. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.009969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wintemute GJ. Disproportionate sales of crime guns among licensed handgun retailers in the United States: a case-control study. Inj Prev. 2009;15(5):291–299. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.017301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wintemute GJ. Firearm retailers' willingness to participate in an illegal gun purchase. J Urban Health. 2010;87(5):865–878. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9489-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wintemute GJ. Inside gun shows: what goes on when everybody thinks nobody's watching. Sacramento: Violence Prevention Research Program; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright MA, Wintemute GJ, Webster DW. Factors affecting a recently-purchased handgun's risk for use in crime under circumstances that suggest gun trafficking. J Urban Health. 2010;87(3):352–364. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9437-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco Firearms and Explosives. Downloadable lists of Federal Firearms Licensees (FFLs). Available at: http://www.atf.gov/about/foia/ffl-list.html. Accessed March 18, 2011.

- 17.Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco Firearms and Explosives. Permanent Brady permit chart. Available at: http://www.atf.gov/firearms/brady-law/permit-chart.html. Accessed December 10, 2009.

- 18.Bowling M, Frandsen RJ, Lauver GA, Boutilier AD, Adams DB. Background checks for firearms transfers, 2009 - statistical tables. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statitics, 2010. NCJ 231679.

- 19.SAS for Windows [computer program]. Version 9.1.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2003.

- 20.Dillman D, Smith J. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. 3. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bureau of Justice Statistics. Survey of state procedures related to firearm sales, midyear 2004. St. Louis, Missouri: Bureau of Justice Statistics, August, 2005. NCJ 209288.

- 22.Dillman DA, Gertseva A, Mahon-Haft T. Achieving usability in establishment surveys through the application of visual design principles. J Off Stat. 2005;21(2):183–214. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wintemute GJ, Wright MA. Swimming pool owners' opinions of strategies for prevention of drowning. Pediatrics. 1990;85(1):63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romero MP, Wintemute GJ, Vernick JS. Characteristics of a gun exchange program, and an assessment of potential benefits. Inj Prev. 1998;4(3):206–210. doi: 10.1136/ip.4.3.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Federal Bureau of Investigation. Total NICS background checks. Current version available at: http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/nics/reports/04032012_1998_2012_monthly_yearly_totals.pdf. Accessed November, 2010.

- 26.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 7th edition. 2011.

- 27.Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. ATF snapshot 1999. Available at: http://www.atf.gov/publications/general/snapshots/atf-snapshot-1999.html. Accessed November 10, 2010.

- 28.Koper CS. Purchase of multiple firearms as a risk factor for criminal gun use: implications for gun policy and enforcement. Criminol Public Pol. 2005;4(4):749–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2005.00354.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Commerce in firearms in the United States. Washington, DC: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paxson MC, Dillman DA, Tarnai J, et al. Improving response to business mail surveys. In: Cox BG, Binder DA, Chinnappa BN, et al., editors. Business survey methods. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1995. pp. 303–315. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kriauciunas A, Parmigiani A, Rivera-Santos M. Leaving our comfort zone: integrating established practices with unique adaptations to conduct survey-based strategy research in nontraditional contexts. Strateg Manage J. 2011;32(9):994–1010. doi: 10.1002/smj.921. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson TP, Wislar JS. Response rates and nonresponse errors in surveys. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1805–1806. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voigt LF, Koepsell TD, Daling JR. Characteristics of telephone survey respondents according to willingness to participate. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(1):66–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keane L. Firearm industry warns retailers of anti-gun survey. National Shooting Sports Foundation, 2011. Available at: http://www.nssfblog.com/firearms-industry-warns-retailers-of-anti-gun-survey/. Accessed June 18, 2011.

- 35.National Rifle Association. Warning—anti-gun survey of firearms dealers under way! National Rifle Association, 2011. Available at: http://www.nraila.org/legislation/federal-legislation/2011/6/warning-anti-gun-survey-of-firearms.aspx. Accessed June 30, 2011.

- 36.National Rifle Association Institute for Legislative Action. Warning—anti-gun survey of firearms dealers under way! [E-mail communication]. Personal communication to Wintemute GJ, June 29, 2011.

- 37.Keane L. Retailers heeding industry's caution of anti-gun survey. National Shooting Sports Foundation, 2011. Available at: http://www.nssfblog.com/retailers-heeding-industry’s-caution-of-anti-gun-survey/. Accessed July 13, 2011.

- 38.Keane L. Anti-gun survey continues to make the rounds; retailers heed industry's caution. National Shooting Sports Foundation, 2011. Available at: http://www.nssfblog.com/anti-gun-survey-continues-to-make-the-rounds-retailers-heed-industry%E2%80%99s-caution/. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- 39.Wintemute GJ. Association between firearm ownership, firearm-related risk and risk reduction behaviours and alcohol-related risk behaviours. Inj Prev. 2011;17(6):422–427. doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.031443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hassol A, Harrison H, Rodriguez B, Jarmon R, Frakt A. Survey completion rates and resource use at each step of a Dillman-style multi-modal survey. Presented at the American Association of Public Opinion Research annual meeting, May 15-18, 2003, Nashville, TN, USA. Available at http://www.abtassociates.com/presentations/AAPOR-2.html. Accessed May 9, 2012.