Abstract

Social and environmental influences on gambling behavior are important to understand because localities can control the sanction and location of gambling opportunities. This study explores whether neighborhood disadvantage is associated with gambling among predominantly low-income, urban young adults and to explore if we can find differences in physical vs. compositional aspects of the neighborhood. Data are from a sample of 596 young adults interviewed when they were 21–22 years, who have been participating in a longitudinal study since entering first grade in nine public US Mid-Atlantic inner-city schools (88 % African Americans). Data were analyzed via factor analysis and logistic regression models. One third of the sample (n = 187) were past-year gamblers, 42 % of them gambled more than once a week, and 31 % had gambling-related problems. Those living in moderate and high disadvantaged neighborhoods were significantly more likely to be past-year gamblers than those living in low disadvantaged neighborhoods. Those living in high disadvantaged neighborhoods were ten times more likely than those living in low disadvantaged neighborhoods to have gambling problems. Factor analysis yielded a 2-factor model, an “inhabitant disadvantage factor” and a “surroundings disadvantage factor.” Nearly 60 % of the sample lived in neighborhoods with high inhabitants disadvantage (n = 375) or high surroundings disadvantage (n = 356). High inhabitants disadvantage was associated with past-year frequent gambling (odds ratios (aOR) = 2.26 (1.01, 5.02)) and gambling problems (aOR = 2.81 (1.18, 6.69)). Higher neighborhood disadvantage, particularly aspects of the neighborhood concerning the inhabitants, was associated with gambling frequency and problems among young adult gamblers from an urban, low-income setting.

Keywords: Pathological gambling, Factor analysis, Statistical, Environment

Introduction

Social and environmental influences on gambling behavior are important to understand because localities can control the sanction and location of gambling opportunities (e.g., lottery and slot machine venues are more common in disadvantaged neighborhoods as compared with more affluent neighborhoods).1–5 Individuals living in disadvantaged neighborhoods were more likely to report higher frequencies of gambling behaviors and gambling problems than those who did not live in disadvantaged neighborhoods.4,6,7 A US national telephone survey found that neighborhood disadvantage showed no effect on past year gambling, but it had a strong positive effect on frequency of gambling and problem/pathological gambling.4 Those living in the 10 % most disadvantaged neighborhoods were 12 times more likely to have gambling problems as compared with the 10 % living in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods.4 In another US national telephone survey, the mean number of days in the past year spent gambling were twice as high among participants who lived in the top fifth most disadvantaged neighborhoods as compared with those residing in neighborhoods of the lowest fifth disadvantage.5

Social disorganization theory posits that neighborhoods with few economic and social resources and a lack of community social control which deters deviant and criminal behavior and further social and economic breakdown are more disadvantaged.8–10 Welte and colleagues4 suggest that compositional aspects of disadvantaged neighborhoods, such as being the subject of racial discrimination, being exposed to neighborhood violence, living in poverty, and having low social competence, promote gambling. Among adolescents from a Great Lakes Indian Reservation marked with great poverty, 48 % reported that they often “dreamt of solving their problems by winning a lot of money” and 33 % felt gambling was a “fast and easy way to earn money.”11 On the other hand, the proximity or physical access to gambling venues might be what links neighborhood disadvantage to gambling activities and problems.4,12 In Montreal, Canada, students attending high-schools in lower socio-economic status neighborhoods (with a higher concentration of gambling venues) as compared with more affluent neighborhoods (where gambling venues are less common), are 40 % more likely to gamble.2 In Nevada, where there are three major casino markets as well as several Indian casinos, the prevalence of gambling problems was substantially higher than that of the national US estimate.13 A recent telephone survey of Maryland residents found that those who reported any gambling problem travel shorter distances to gamble compared with gamblers who reported no problems.14

An important gap in this area of research deals with inner-city youth who typically live in more disadvantaged neighborhoods and are more adversely affected by the negative consequences of activities such as alcohol and drug use and gambling.8,15 The aim of this study is to explore whether neighborhood disadvantage is associated with gambling behaviors and to explore if we can find differences in physical versus compositional aspects of the neighborhood. Furthermore, we aim to examine the potential relationship between proximity to gambling venues and gambling behaviors.

Methods

Sample

Data for this cross-sectional analysis come from interviews conducted in 2008 and 2009. Interviews are part of a longitudinal prospective study being conducted within the context of a group randomized prevention trial that has been following the same cohort of youth since they began first grade in nine primary public schools in a US mid-Atlantic city. Details of the trial design and interventions are available elsewhere.16 Cohort recruitment occurred in Fall 1993 (n = 678; mean age = 6.2 years; 53 % male; 86 % African American and 14 % White; 62 % received free or reduced lunch). The cohort is followed up and interviewed annually and does not exclude those who dropped out of school or those incarcerated. The study sample focuses on the 596 young adults (88 % of original cohort) who took part in the assessments when they were 21–22 years of age. Chi-square tests showed no differences by sex, race, percentage receiving subsidized lunches, or intervention condition between the current sample and the original cohort (p values of >0.05).

Data were collected via a self-administered computer interview that averaged 60–90 min in length, or for those located out of the geographic region, via telephone. Time was taken initially to establish rapport with the respondents, starting with general health questions, followed by questions regarding substance use and gambling behavior. A certificate of confidentiality was obtained. Study protocols were approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board. All young adults provided signed consent.

Measures

Past-year gambling behavior was assessed using the 20-item South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS)17 when participants were ages 21 and 22 years. The SOGS assessed the frequency (e.g., not at all and less than once a week) and type of gambling behaviors (e.g., lottery and bingo) individuals engaged in during the past year which allow us to distinguish whether participants had gambled in the prior year (i.e., nongambler vs. gambler). The responses (i.e., never, less than once a month, once a month, at least once a month, and everyday) to these type of gambling behavior items were also used to classify gamblers into two groups reflecting the intensity/frequency of past-year gambling involvement: (1) infrequent gamblers gambled less than once a week and (2) frequent gamblers gambled at least weekly. Those who report any past-year gambling also completed a checklist of ten gambling problems (e.g., gambling more than intended and felt guilty about gambling) as described in the DSM-III-R.18 Using these items, young adult gamblers were classified as those with no gambling problems and those with at least one gambling problem. Past-year gamblers also answered four additional questions on opportunity to gamble adapted from the 2006 California Problem Gambling Prevalence Survey,19 which asked about the distance of their homes to the nearest gambling venues

The ten-item Neighborhood Environment Scale (NES)20 is a self-reported measure of neighborhood characteristics (e.g., having safe places to walk, often see drunk people on the street, rated as true or false for their neighborhood using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true; 4 = very true). Items were scored so that higher scores reflected increasing aversive neighborhood conditions. After calculating the mean of the sum of the ten items, Z-scores were then created and then tertiled. Scores in the first tertile were categorized as “least” disadvantage, second tertile as “moderate” disadvantage, and third tertile as “high” disadvantage. Factor analysis explored different facets of neighborhood characteristics captured by the NES items. Two facets with eigenvalues greater than 1 were identified via varimax rotation (Table 1): one factor dealt with disadvantages inflicted on the inhabitants (e.g., kids in the neighborhood get beat up or mugged) and the other factor dealt with disadvantages inflicted on one’s neighborhood (e.g., people in my neighborhood often damage or steal each other’s property). Items with factor loadings of greater than 0.4 within each factor were then summed up to create subscores for Inhabitants and Surroundings, and Z-scores were then created from these subscores. For each of the neighborhood z-scores, participants who scored in the lower 50 % were categorized as living in “low” inhabitants/surroundings disadvantage neighborhoods while those in the 50 % and above range were categorized as living in “high” inhabitants/surroundings disadvantage neighborhoods. Internal consistency was 0.83 for the Inhabitants and 0.64 for the surroundings subscales. Furthermore, the Inhabitants and Surroundings Z-scores were not found to be correlated (r = −0.0621; p = 0.12).

Table 1.

Factor analysis using Neighborhood Environment Scale20 items

| Variable | Factor 1 (inhabitants) | Factor 2 (surroundings) | Uniqueness |

|---|---|---|---|

| I feel safe walking around my neighborhood by myself during the day | 0.63 | −0.13 | 0.59 |

| Every few weeks, kids in the neighborhood get beat up or mugged | 0.81 | −0.08 | 0.33 |

| Every few weeks, adults in the neighborhood get beat up or mugged | 0.80 | −0.14 | 0.33 |

| I have seen people using or selling drugs in my neighborhood | 0.68 | −0.21 | 0.49 |

| During the day, I often see drunk people on the street | 0.74 | −0.14 | 0.44 |

| In my neighborhood, those with the most money are drug dealers | 0.62 | −0.22 | 0.57 |

| Plenty of safe places to walk or spend time outdoors in neighborhood | −0.34 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| Most adults in my neighborhood respect the law | −0.39 | 0.51 | 0.59 |

| People in my neighborhood often damage or steal each other’s property | −0.07 | 0.71 | 0.49 |

| I feel safe walking around my neighborhood by myself at night | −0.10 | 0.70 | 0.49 |

Perceived racism was collected via seven items drawn from the Racism and Life Experiences Scales,21 which assessed how often youth have experienced racism or negative events associated with his/her race. Items were scored on a six-point Likert Scale (1 = never, 2 = less than once a year, 3 = few times a year, 4 = about once a month, 5 = a few times a month, and 6 = once a week or more). A summary score was created by taking the mean of the sum of the seven items, with higher scores indicating higher perceived racism. Due to the high percentage of missing perceived racism data in the 2008 and 2009 assessments (8.9 % of the overall sample and 8.0 % among past-year gamblers), perceived racism summary scores were imputed using the last available data dating back to the 2000 assessment wave (age 14 years). As a result, 0.9 % of the overall sample had missing perceived racism while no past-year gamblers were missing such score. Perceived racism scores from the 2000–2009 waves were found to be significantly positively correlated. Furthermore, the imputed and nonimputed scores did not differ in either the overall sample or among past-year gamblers. Z-scores were next created from the imputed perceived racism scores, and participants who scored in the lower 50 % were categorized as “low” perceived racism while those in the 50 % and above range were categorized as “high” perceived racism.

Household characteristics (e.g., being raised by a single caregiver) were assessed by parental report when the youth was entering first grade. Other demographics of the sample (e.g., age, race, and subsidized lunch status) were obtained from school records. Subsidized/free lunch eligibility has been found to correlate highly with family income and other traditional measures of socioeconomic status.22

Analysis

Chi-square statistics were conducted to uncover differences in the demographic and neighborhood characteristics between gamblers and nongamblers, frequent gamblers and infrequent gamblers, and gamblers with and without a gambling problem. Logistic regression models estimated odds ratios (aOR) and 95 % confidence intervals in the presence of other covariates: sex, race, first-grade single-head of household, first-grade subsidized lunch status, first grade intervention status, perceived racism, and neighborhood disadvantage. To accommodate the initial sample design (clustering of students within schools), a variant of the Huber–White sandwich estimator of variance to obtain robust standard errors and variance estimates was used.23

Results

Bivariate Associations

Approximately one third of the sample (n = 188) were past-year gamblers (Table 2). Among past-year gamblers, 43 % gambled more than once a week and 31 % had a gambling-related problem. Males were not only more likely to gamble in the past year (37.2 vs. 25.4 %; p = 0.002), but they also were more likely to gamble more frequently (48.7 vs. 32.9 %; p = 0.03) and have gambling-related problems 37.4 vs. 21.9 %; p = 0.04) than females.

Table 2.

Frequency distributions for demographic and neighborhood disadvantage (tertiles) by gambling status (N = 596)

| Overall | Past-year gamblersa | Frequent gamblersb | Gamblers with problemsc | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (col %) | n (row %) | aOR | 95 % CI | p | n (row %) | aOR | 95 % CI | p | n (row %) | aOR | 95 % CI | p | |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | |||||||||||||

| Least | 222 (37.3) | 51 (23.0) | 1.00 | 19 (37.3) | 1.00 | 5 (9.8) | 1.00 | ||||||

| Moderate | 180 (30.2) | 59 (32.8) | 1.66 | 1.02, 2.70 | 0.04 | 21 (35.6) | 0.86 | 0.37, 1.99 | 0.73 | 16 (27.1) | 3.78 | 0.92, 15.46 | 0.06 |

| High | 193 (32.4) | 78 (41.4) | 2.25 | 1.45, 3.48 | <0.001 | 40 (51.3) | 1.76 | 0.83, 3.73 | 0.14 | 38 (48.7) | 9.59 | 2.62, 35.16 | 0.001 |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | |||||||||||

| Perceived racism | |||||||||||||

| Low | 316 (53.0) | 78 (24.7) | 1.00 | 29 (37.2) | 1.00 | 22 (28.2) | 1.00 | ||||||

| High | 275 (46.1) | 110 (40.0) | 2.22 | 1.42, 3.48 | 0.001 | 51 (46.4) | 1.57 | 0.82, 3.00 | 0.18 | 37 (33.6) | 1.62 | 0.83, 3.17 | 0.16 |

| Missing | 5 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Female | 287 (48.2) | 73 (25.4) | 1.00 | 24 (32.9) | 1.00 | 16 (21.9) | 1.00 | ||||||

| Male | 309 (51.9) | 115 (37.2) | 1.66 | 1.15, 2.41 | 0.01 | 56 (48.7) | 2.03 | 0.98, 3.48 | 0.06 | 43 (37.4) | 1.90 | 0.87, 4.14 | 0.11 |

| Race | |||||||||||||

| African American | 522 (87.6) | 159 (30.5) | 1.00 | 68 (42.8) | 1.00 | 50 (31.5) | 1.00 | ||||||

| Non-African American | 74 (12.4) | 29 (39.2) | 2.13 | 1.29, 3.54 | 0.003 | 12 (41.4) | 1.25 | 0.49, 3.19 | 0.64 | 9 (31.0) | 1.29 | 0.58, 2.88 | 0.53 |

| Household compositiond | |||||||||||||

| Two-Parent | 225 (37.8) | 69 (30.7) | 1.00 | 28 (40.6) | 1.00 | 23 (33.3) | 1.00 | ||||||

| Single-Parent | 293 (49.2) | 98 (33.5) | 1.27 | 0.88, 1.84 | 0.20 | 42 (42.9) | 1.03 | 0.51, 2.05 | 0.94 | 31 (31.6) | 0.78 | 0.34, 1.77 | 0.56 |

| Missing | 78 (13.1) | 21 (11.2) | 0.90 | 0.47, 1.72 | 0.74 | 10 (47.6) | 1.49 | 0.56, 3.94 | 0.43 | 5 (23.8) | 0.57 | 0.15, 2.26 | 0.43 |

| Subsidized lunchd | |||||||||||||

| No | 182 (30.6) | 59 (32.4) | 1.00 | 22 (37.3) | 1.00 | 15 (25.4) | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes (free or reduce) | 409 (68.6) | 126 (30.8) | 0.92 | 0.74,1.32 | 0.65 | 57 (45.2) | 1.30 | 0.69,2.46 | 0.42 | 43 (34.1) | 1.26 | 0.48,3.31 | 0.64 |

| Missing | 5 (0.8) | 3 (1.6) | 1.50 | 0.41,5.50 | 0.54 | 1 (33.3) | 0.49 | 0.05,5.13 | 0.55 | 1 (33.3) | 0.46 | 0.04,5.36 | 0.53 |

| Intervention statusd | |||||||||||||

| Control | 197 (33.1) | 57 (28.9) | 1.00 | 21 (36.8) | 1.00 | 20 (35.1) | 1.00 | ||||||

| Intervention | 399 (66.9) | 131 (32.8) | 1.13 | 0.84,1.53 | 0.43 | 59 (45.0) | 1.45 | 0.76,2.79 | 0.26 | 39 (29.8) | 0.78 | 0.42,1.44 | 0.42 |

All models adjusted for perceived racism, sex, race, household, subsidized lunch, intervention, and neighborhood disadvantage

aReference group = nongamblers

bReference group = infrequent past-year gamblers

cReference group = past-year gamblers with no gambling problems

dAssessed in first grade (mean age = 6.2)

Among residents of the Least disadvantage neighborhoods, 23.0 % (n = 51) were past-year gamblers, compared with 32.8 % (n = 59) of moderate disadvantage neighborhood residents, and 41.4 % (n = 78) of high disadvantage neighborhood residents (p = 0.002). Frequent gambling among past-year gamblers did not appear to be associated with level of neighborhood disadvantage. Gambling problems among past-year gamblers, on the other hand, were highest in high disadvantage neighborhoods (48.7 %), followed by moderate (27.1 %), then least (9.8 %) disadvantage neighborhoods (p < 0.001).

While past-year gamblers were significantly more likely to report high than low perceived racism (40.0 vs. 24.7 %; p < 0.001), perceived racism was not found to be associated with frequent gambling or gambling problems among past-year gamblers.

Multivariate Associations

Results of multiple logistic regression models of the three gambling outcomes and level of neighborhood disadvantage, perceived racism, sex, race, household structure, subsidized lunch status, and intervention status are shown in Table 2. After adjustment for the other covariates, males remained more likely than females to be past-year gamblers (aOR = 1.66 (1.15, 2.41)), became marginally more likely to be frequent gamblers (aOR = 2.03 (0.98, 3.48)) than females, and there was no gender differences in past-year gambling problems.

Adjusted models showed that compared with least disadvantage neighborhoods residents, the odds of past-year gambling were increased among moderate (aOR = 1.66 (1.02, 2.70)) and high (aOR = 2.25 (1.45, 3.48)) disadvantage residents, while the odds of gambling problems among past-year gamblers increased approximately tenfold (aOR = 9.59 (2.62, 35.16)) among those living in high disadvantage neighborhoods as compared with those living in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods. Similarly, high perceived racism increased the odds of past-year gambling by more than twofold (aOR = 2.22 (1.42, 3.48)) upon adjustment of neighborhood disadvantage and demographic characteristics.

Factor Analysis of the Neighborhood Environment Scale

Table 3 shows the results using the inhabitants and surroundings neighborhood factors that were created by factor analysis (see “Methods”). Approximately two thirds of the sample (n = 375) lived in neighborhoods with high inhabitants disadvantage and 59.7 % (n = 356) in neighborhoods with high surroundings disadvantage. Significantly more residents of neighborhoods with high inhabitant disadvantage were past-year gamblers (p = 0.05), frequent gamblers (p = 0.02) and gamblers with any gambling problems (p = 0.03) than residents of neighborhoods with Low Inhabitant disadvantage. No association was found between any of the gambling characteristics and neighborhoods with high surroundings disadvantage. Adjusted for perceived racism, demographic characteristics, and neighborhood Surroundings disadvantage, residents of high inhabitants disadvantage neighborhoods had increased odds of past-year frequent gambling (aOR = 2.26 (1.01, 5.02)), and gambling problems (aOR = 2.81 (1.18, 6.69)) as compared with those living in neighborhoods with low inhabitants disadvantage.

Table 3.

Frequency distributions for demographic and neighborhood disadvantage characteristics by gambling status (N = 596)

| Overall | Past-year gamblersa | Frequent gamblersb | Gamblers with problemsc | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (col %) | n (row %) | aOR | 95 % CI | p | n (row %) | aOR | 95 % CI | p | n (row %) | aOR | 95 % CI | p | |

| Neighborhood inhabitants | |||||||||||||

| Low disadvantage | 221 (37.1) | 59 (26.7) | 1.00 | 18 (30.5) | 1.00 | 11 (18.6) | 1.00 | ||||||

| High disadvantage | 375 (62.9) | 129 (34.4) | 1.31 | 0.87, 1.99 | 0.20 | 62 (48.1) | 2.26 | 1.01, 5.02 | 0.05 | 48 (37.2) | 2.81 | 1.18, 6.69 | 0.02 |

| Neighborhood surroundings | |||||||||||||

| Low disadvantage | 240 (40.3) | 82 (34.2) | 1.00 | 35 (42.7) | 1.00 | 26 (31.7) | 1.00 | ||||||

| High disadvantage | 356 (59.7) | 106 (29.8) | 0.75 | 0.53, 1.08 | 0.12 | 45 (42.5) | 0.98 | 0.47, 2.04 | 0.96 | 33 (31.1) | 1.09 | 0.55, 2.14 | 0.81 |

All models adjusted for perceived racism, sex, race, household, subsidized lunch, intervention, and neighborhood factors

aReference group = nongamblers

bReference group = infrequent past-year gamblers

cReference group = past-year gamblers with no gambling problems

Gambling Access

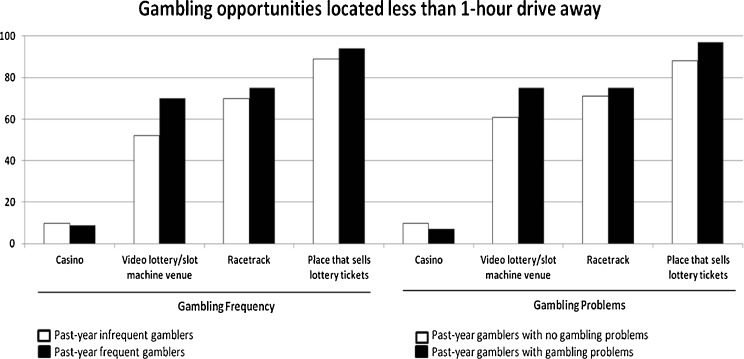

As distance from one’s home to various gambling opportunities (i.e., casinos, video lottery/slot machine venues, racetrack, and places that sell lottery tickets) were collected from past-year gamblers only, the relationships between gambling proximity with gambling frequency and gambling problems were next assessed among the respondents that gambled in the past-year. Nine percent of the past-year gamblers lived within a 1-h drive from the nearest casino (Figure 1), 65.5 % from the nearest video lottery/slot machine venues, 72.1 % from the nearest racetrack, and 90.9 % from the nearest place that sells lottery tickets. While the differences were not statistically significant, the results showed a general trend for frequent gamblers and gamblers with any gambling problems to be more likely to live closer to video lottery/slot machine venues, racetrack, and places that sells lottery tickets than infrequent gamblers and gamblers with no gambling problems, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Gambling opportunities located less than 1-h drive away.

Discussion

Higher neighborhood disadvantage, particularly aspects of the neighborhood concerning the inhabitants (e.g., kids in the neighborhood get beat up or mugged), was associated with gambling frequency and problems among young adult gamblers from an urban, low-income setting. More residents of moderate and high disadvantaged neighborhoods had gambled in the past year as compared with residents of low disadvantaged neighborhoods. Our findings are consistent with findings from studies conducted among adult samples.3,4 Also consistent with other studies, gambling problems among past-year gamblers were more prevalent in high and moderate disadvantaged neighborhoods as compared with low disadvantaged neighborhoods.4–6 However, to date, there has been no description of the spatial distribution of gambling venues (e.g., lottery outlets) in Baltimore city; thus, it is uncertain whether this relationship is due to higher accessibility to gambling venues, or simply due to the fact that environmental influences present in disadvantaged neighborhoods promote gambling,4 or whether gambling activities are more common in these more disadvantaged neighborhoods due to a combination of these environmental influences as well as accessibility/proximity to gambling venues. Moreover, a small proportion of the young adults in our sample have moved away from the greater Baltimore area.

Interestingly, when we further investigated the compositional aspects of the neighborhoods through factor analysis we found that residents of neighborhoods with high inhabitant disadvantage were more likely to be frequent gamblers and have gambling problems than residents of neighborhoods with low inhabitant disadvantage. On the other hand, there were no significant differences in past-year gambling, frequent gambling and gambling problems in regards to living in a neighborhood with high surroundings disadvantage versus living in a neighborhood with low surroundings disadvantage. This suggests that characteristics pertaining specifically to the neighborhood’s inhabitants (e.g., personality factors, engagement in deviant behaviors, being exposed to neighbors who engage in deviant behaviors) might be more important in specifying who will develop gambling problems than merely the fact of living in a more physically deprived neighborhood. Indeed, Brook and colleagues24 have shown that growing up in a neighborhood in which one is constantly exposed to neighborhood violence and illegal drug use can lead to engagement in unhealthy behaviors in adulthood. Areas in which violence and illegal drug use are more pervasive can lead to higher levels of neighborhood stress and disorganization. Thus, there is the possibility that those living in neighborhoods with high inhabitant disadvantage might be gambling more frequently and developing gambling problems in response to the neighborhood stress they are constantly exposed to. In addition, similar to what happens with alcohol use,8 youth that perceive their neighborhoods to be disorganized might engage more frequently in gambling activities.

In general, frequent gamblers (versus infrequent) and gamblers with any gambling problems (versus those with no problems) were more likely to live closer to video lottery/slot machine venues, racetrack, and places that sells lottery tickets. These findings are consistent with prior studies that show that greater accessibility to gambling venues leads to higher levels of frequent gambling and gambling problems.2,4,12,14 Maryland residents have recently approved the expansion of legalized gambling in the state, thus, in future years, more Baltimore residents will be living close to venues in which video lottery/slot machines will be available.

It is necessary to note strengths and potential limitations of this study. This sample was largely comprised of African-American students from urban neighborhoods selected to be representative of all students starting first grade in the public school system in 1993. Thus, cohort effects are minimal and there is very little variation in age since they all began primary school in the same calendar year. These findings add to the knowledge about neighborhood influence on gambling behaviors among minority youth as very few other study samples include large numbers of minority youth. However, the characteristics of the sample hamper generalization to other students growing up in other metropolitan areas with different racial and cultural compositions. Another limitation of this study is due to the secondary nature of the topic within the larger cohort prospective study from which the data were drawn. There might have been some level of social mobility during the years this study was conducted (e.g., youth living in less disadvantaged neighborhoods moving to high disadvantaged neighborhoods and vice versa), which were not captured in these analyses.

Nevertheless, this study highlights the importance of considering neighborhood environment factors when examining gambling behaviors in young adulthood. Future studies should consider probing further into the compositional aspects of neighborhood environment and also examine how neighborhood environment interacts with home environment in regards to gambling behavior as youth are growing up. Moreover, since localities can control the sanction and location of gambling opportunities (e.g., establish where new slot machine venues will be implemented), the government should try to minimize the harmful effects of problem gambling among already deprived communities when planning the location of new gambling outlets.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a research grant from the National Institute of Child and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (NICHD-NIH, RO1HD060072—P.I. Dr. Martins). The Intervention Trial is funded by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant RO1 DA11796 (P.I. Dr. Ialongo). We thank Scott Hubbard for data management.

References

- 1.Gilliland JA, Ross NA. Opportunities for video lottery terminal gambling in Montréal: an environmental analysis. Can J Public Health. 2005;96:55–59. doi: 10.1007/BF03404019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson DH, Gilliland J, Ross NA, et al. Video lottery terminal access and gambling among high school students in Montréal. Can J Public Health. 2006;97:202–206. doi: 10.1007/BF03405585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss MJ. The clustering of America. New York: Harper & Row; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welte JW, Wieczorek WF, Barnes GM, et al. The relationship of ecological and geographic factors to gambling behavior and pathology. J Gambl Stud. 2004;20:405–423. doi: 10.1007/s10899-004-4582-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National gambling impact study commission final report. Washington, DC: National Gambling Impact Study Commission; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes GM, Welte JW, Tidwell MCO, et al. Gambling on the lottery: sociodemographic correlates across the lifespan. J Gambl Stud. 2011;27:575–586. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9228-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welte J, Wieczorek W, Barnes G, et al. Multiple risk factors for frequent and problem gambling: individual, social and ecological. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;36:1548–1568. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00071.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner AB, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Neighborhood variation in adolescent alcohol use: examination of socioecological and social disorganization theories. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:651–659. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. Am J Sociol. 1989;94:774–802. doi: 10.1086/229068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw C, McKay H. Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peacock RB, Day PA, Peacock TD. Adolescent gambling on a Great Lakes Indian Reservation. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 1999;2:5–17. doi: 10.1300/J137v02n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearce J, Mason K, Hiscock R, et al. A national study of neighbourhood access to gambling opportunities and individual gambling behaviour. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:862–868. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.068114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volberg RA. Gambling and problem gambling in Nevada. Carson City: Department of Human Resources; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shinogle J, Norris DF, Park D, et al. Gambling prevalence in Maryland: a baseline analysis. Baltimore: Maryland Institute for Policy Analysis and Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Children and youth in neighborhood contexts. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12:27–31. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ialongo N, Poduska J, Werthamer L, et al. The distal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on conduct problems and disorder in early adolescence. J Emot Behav Disord. 2001;9:146–161. doi: 10.1177/106342660100900301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): a new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, revised third edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volberg RA, Nysse-Carris KL, Gerstein DR. 2006 California problem gambling prevalence survey. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliot DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ensminger ME, Forrest CB, Riley AW, et al. The validity of measures of socioeconomic status of adolescents. J Adolesc Res. 2000;15:392–419. doi: 10.1177/0743558400153005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers WH. Regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Tech Bull. 1993;13:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brook DW, Brook JS, Rubenstone E, et al. Developmental associations between externalizing behaviors, peer delinquency, drug use, perceived neighborhood crime, and violent behavior in urban communities. Aggress Behav. 2011;37:349–361. doi: 10.1002/ab.20397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]