Abstract

Genome-wide analysis of translational control has taken strides in recent years owing to the advent of high-throughput technologies, including DNA microarrays and deep sequencing. Global studies have unraveled a principal role, among posttranscriptional mechanisms, for mRNA translation in determining protein levels in the cell. The impact of translational control in dynamic regulation of the proteome under different conditions is increasingly appreciated. Here we review genome-wide studies that use high-throughput techniques and bioinformatics to assess the role of mRNA translation in the regulation of protein levels; we also discuss how genome-wide data on mRNA translation can be obtained, analyzed, and used to identify mechanisms of translational control.

High-throughput technologies and bioinformatics tools have revealed how translational control mechanisms substantially affect gene expression and protein levels on a global scale.

The gene expression pathway leading to protein production consists of many mechanistic layers that are subject to regulation. They are commonly grouped into transcriptional or posttranscriptional types. Some posttranscriptional mechanisms, including RNA splicing, mRNA editing, and posttranslational modification, determine the identity and activity of the protein products, whereas others control protein levels by regulating transport of mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, mRNA stability, translation, and protein stability. Determining how posttranscriptional regulation contributes to protein levels and, more precisely, how regulation of translation impacts gene expression have attracted substantial attention during the last decade.

POSTTRANSCRIPTIONAL MECHANISMS SUBSTANTIALLY AFFECT GENE EXPRESSION LEVELS AT A GENOME-WIDE SCALE

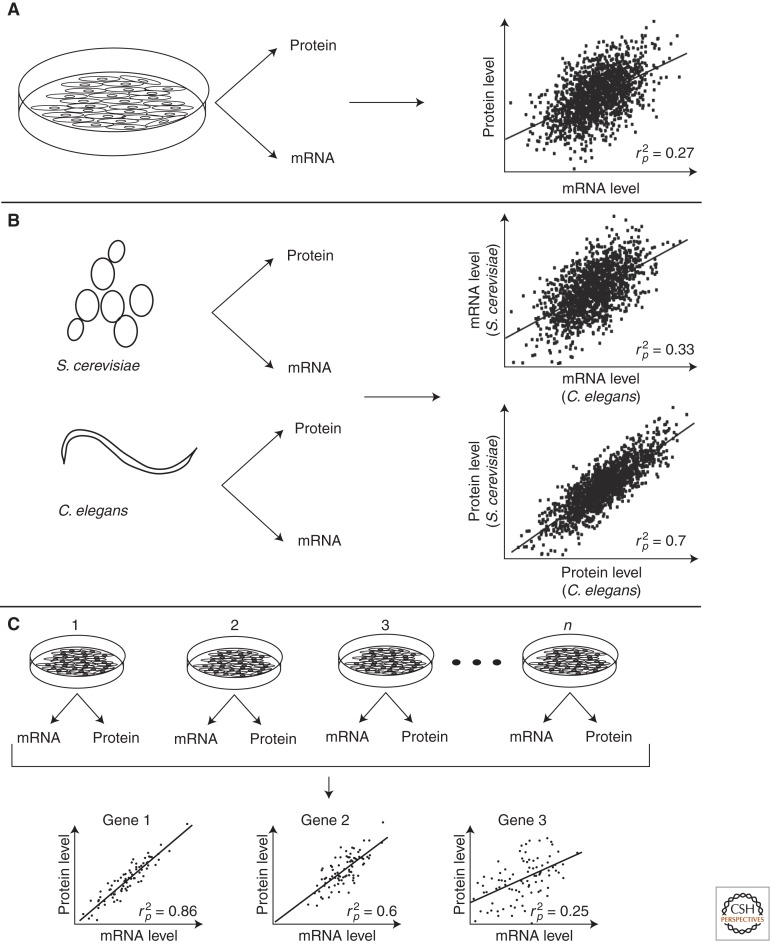

Several studies have examined the extent to which posttranscriptional mechanisms affect protein expression by comparing mRNA and protein levels, either in one cell state or across different conditions. This is typically based on Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients, denoted as rp or rs, respectively (for examples, see Fig. 1). Both range from −1 to 1, where 0 indicates no correlation and −1 and 1 indicate perfect negative and positive correlations, respectively. Whereas Pearson correlation is based on actual values, Spearman correlation uses ranks (ordered by values) and is therefore less influenced by extreme values (outliers). A squared Pearson correlation value (rp2; the coefficient of determination) describes how much of the variance of one factor is explained by that of the other factor. For example, a Pearson correlation between protein and mRNA levels of 0.6 indicates that 36% (0.62) of the protein levels can be explained by mRNA levels. Thus, a lower rs or rp2 between mRNA and protein levels indicates more posttranscriptional regulation.

Figure 1.

Approaches to examine the contribution of posttranscriptional regulation to protein expression. (A) Comparison of mRNA and protein levels from a single condition. Measured mRNA and protein levels are compared to indicate posttranscriptional regulation across genes using rp2, which describes the fraction of the observed protein levels that are explained by mRNA levels. (B) Cross-species analysis of mRNA and protein levels. mRNA and protein levels are obtained in parallel from two species, and cross-species levels are compared. Higher correlation of protein levels across species as compared with mRNA levels indicates posttranscriptional regulation that maintains conserved protein levels. (C) Parallel measurements of mRNA and protein levels across many conditions. Per gene mRNA and protein levels are compared across conditions to estimate dynamic regulation of gene expression by posttranscriptional mechanisms. As indicated by rp2, gene 3 shows more posttranscriptional regulation as compared with gene 1. Simulated numbers are shown.

Comparison of mRNA and protein levels across genes under one condition (e.g., steady-state growth) has been conducted in species ranging from bacteria to humans. These studies attempted to assess intrinsic posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression (Fig. 1A). Pioneering studies in yeast established genome-wide differences in expression levels between mRNAs and proteins, although they assessed only a fraction of all yeast genes (Futcher et al. 1999; Gygi et al. 1999). Subsequent studies based on measurements of more genes estimated rp2 from 0.14 to 0.73 (Lu et al. 2007; Schmidt et al. 2007; Ingolia et al. 2009) or rs of 0.57 and 0.58 (Ghaemmaghami et al. 2003; Beyer et al. 2004). In bacteria, rp2 between 0.20 and 0.47 has been reported (Nie et al. 2006; Lu et al. 2007; Jayapal et al. 2008). Moreover, in a recent single-cell study in Escherichia coli, mean mRNA copies and protein copies showed rp2 of 0.29 and 0.59 using deep sequencing of RNA (RNA-seq) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), respectively (Taniguchi et al. 2010). These studies indicate that posttranscriptional regulation is used in unicellular organisms, although estimates of its extent vary substantially across studies.

Similar studies performed in multicellular organisms, including Arabidopsis thaliana (Baerenfaller et al. 2008), Drosophila melanogaster, and Caenorhabditis elegans (Schrimpf et al. 2009), all indicated substantial posttranscriptional regulation (rp2 between 0.27 and 0.46 [Baerenfaller et al. 2008] and rs of ∼0.6 [Schrimpf et al. 2009]). Moreover, a recent study of a human cancer cell line reported a modest rp2 of 0.29 from more than 1000 genes (Vogel et al. 2010). Interestingly, these investigators built a model that predicts protein levels from measured mRNA levels and a variety of mRNA properties that affect posttranscriptional regulation, such as the length of the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). The rp2 between the predicted and the measured protein levels increased dramatically as compared with the initial rp2 between mRNA and protein levels (from 0.29–0.67). Because the data used to derive the model were also used to generate the predictions, creating the possibility of data overfitting (meaning that the prediction outcome is heavily influenced by the data used to construct the model), future studies will be needed to assess the generality of the model. Despite this limitation, the study suggests that mRNA sequence features systematically impact protein production through posttranscriptional control.

Cross-species comparisons provide an alternative approach for assessing the importance of posttranscriptional regulation (Fig. 1B). In such studies, mRNA and protein levels from one species are compared with their orthologs in a different species. Assuming that the measurement error is similar for mRNA and protein levels, a higher cross-species correlation between protein levels than between mRNA levels would suggest a role of posttranscriptional control in maintaining conserved protein levels. Based on this reasoning, Schrimpf et al. (2009) reported rs of 0.79 and 0.47 for protein and mRNA levels, respectively, when comparing C. elegans with D. melanogaster. A follow-up study examined all paired comparisons between seven species and found a higher cross-species correlation for protein levels in 17 out of 21 comparisons (Laurent et al. 2010). These comparisons included mRNA measurements obtained by RNA-seq, which is thought to better reflect relative mRNA levels across genes as compared with DNA microarrays (Laurent et al. 2010). Cross-species comparisons thus provide further support for the idea that posttranscriptional mechanisms substantially contribute to determination of protein levels.

A common critique of correlation-based mRNA/protein comparative studies is that the magnitude of systematic and random variations inherent in mRNA and protein analysis tools, such as DNA microarrays, RNA-seq, and mass spectrometry, is often unknown. This is of significance because more variation will lead to lower correlation, giving the appearance of a greater degree of posttranscriptional regulation. This ambiguity in the interpretation of rs or rp2 has been addressed in some studies by assessing how much variation affects the rs or rp2 values. Another caveat is that the half-lives of proteins and their cognate mRNAs often differ, which can reduce rs or rp2 if the mRNA or protein levels are obtained under non-steady-state conditions. Indeed, in mouse NIH/3T3 cells, mRNAs show a median half-life of 9 h, whereas proteins have a median half-life of 46 h (Schwanhausser et al. 2011), making protein level regulation linger over a longer time period relative to the corresponding mRNA. Caution is therefore needed when interpreting rs or rp2 values.

DYNAMIC REGULATION OF GENE EXPRESSION AT THE POSTTRANSCRIPTIONAL LEVEL

In addition to the studies discussed above, which evaluate intrinsic protein levels in the cell, progress has been made in understanding the role of posttranscriptional mechanisms in dynamic regulation of gene expression. Three approaches have been applied to determine whether the protein product levels of individual genes can change independently of their mRNA levels.

In the first approach, mRNA and protein levels are measured under two conditions, and differences between the conditions are calculated for mRNA and protein levels separately. These per gene differences in mRNA and protein levels are then compared across all genes. This approach using yeast produced rs of 0.21 or 0.45 (Griffin et al. 2002; Washburn et al. 2003). A similar study of two human cell lines reported an rp2 of 0.41 (Tian et al. 2004). Importantly, the latter study estimated the maximum obtainable rp2 to 0.81 (given the variation in measurements of mRNA and protein levels) using a simulation approach, suggesting a substantial contribution from posttranscriptional mechanisms in the dynamic regulation of gene expression (rp2 of 0.41 vs. 0.81).

The second approach involves parallel measurement of mRNA and protein levels at several time points following a treatment. This approach also allows for assessment of the extent to which differences in half-lives between mRNAs and proteins can affect the result. A study using yeast monitored the mRNA and protein levels in untreated cells and at six time points following treatment with rapamycin (Fournier et al. 2010). The investigators found that for proteins whose expression had changed, their mRNA levels at 1 h after treatment showed the maximum correlation with protein levels 6 h after treatment—thus, a delayed adjustment of protein levels to mRNA levels. Yet, the rp2 only reached a maximum of 0.36 throughout the experiment. In a similarly designed experiment of mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation with four time points, Lu et al. (2009) concluded that only about half of the proteins that changed their levels also displayed concordant mRNA level changes. A proportion of the proteins that initially did not show concordant protein and mRNA levels did, however, show concordant levels at a later time point.

The third approach minimizes the potential bias arising from differences in mRNA and protein half-lives by studying mRNA and protein levels under steady-state conditions (Fig. 1C). In a recent study, 1066 mRNA and protein levels were measured in 23 human cell lines (Gry et al. 2009). The average rs between mRNA and protein levels was 0.20 and 0.25 using cDNA microarrays or Affymetrix GeneChips, respectively. As a comparison, the average rs between mRNA levels obtained from cDNA microarrays and Affymetrix GeneChips was 0.52. This is substantially higher than that observed between protein and mRNA levels (i.e., 0.2 or 0.25 as compared with 0.52), indicating that mRNA measurement error is not likely to explain the low correlations between protein and mRNA levels. In an extensive study using the approach shown in Figure 1C, mRNA and protein levels in livers from 97 inbred mice were measured (Ghazalpour et al. 2011). Out of 396 genes, only 21% showed significant correlations between mRNA and protein levels. By replicating the experiment, the researchers stratified the genes based on their signal-to-noise ratio, thereby also assessing the impact of random variation on the reported correlations. As expected, the mean rs increased as the signal-to-noise ratio increased and reached a maximum of ∼0.4. Thus, in this extensive study in which differences in half-lives between mRNAs and proteins are likely to have a minimal impact and only genes that could be measured with high confidence were analyzed, the results still support a substantial role for posttranscriptional mechanisms in dynamic regulation of protein levels.

GENOME-WIDE ANALYSIS OF TRANSLATIONAL ACTIVITY

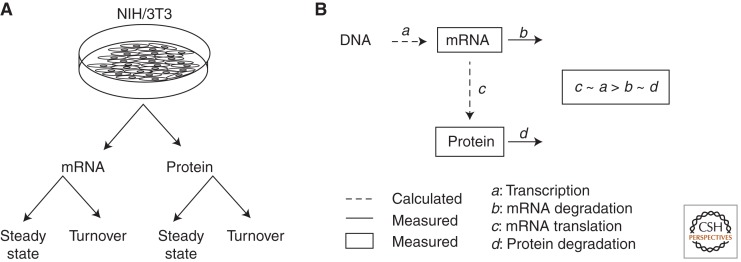

The studies described above all indicate substantial posttranscriptional controls in different systems. A detailed, in-depth examination of posttranscriptional regulation was recently conducted by Schwanhausser et al. (2011), using a multi-omics approach in NIH/3T3 cells (Fig. 2A). They assumed a model in which mRNA levels are determined by transcription and mRNA stability, whereas protein levels are determined by mRNA levels, translational activity, and protein degradation (Fig. 2B). Accordingly, per gene translational activity and transcription could be inferred from measurements of mRNA levels, mRNA stability, protein levels, and protein degradation. Notably, the investigators used independently replicated data to assess the extent to which protein levels predicted by the model compared with the measured levels from the replicates. This allowed the researchers to determine the relative contribution of different gene expression mechanisms while avoiding overfitting. Strikingly, a principal role for mRNA translation among posttranscriptional mechanisms, was identified in determining intrinsic protein levels, strongly suggesting that most of the discrepancies between mRNA and protein levels result from translational control.

Figure 2.

A multi-omics approach to examine relative contributions of posttranscriptional mechanisms to protein expression. (A) Levels and turnover rates for both mRNA and proteins are obtained in parallel. (B) A simple model is used to calculate transcription and translational efficiencies using measured levels and turnover rates for both mRNA and proteins.

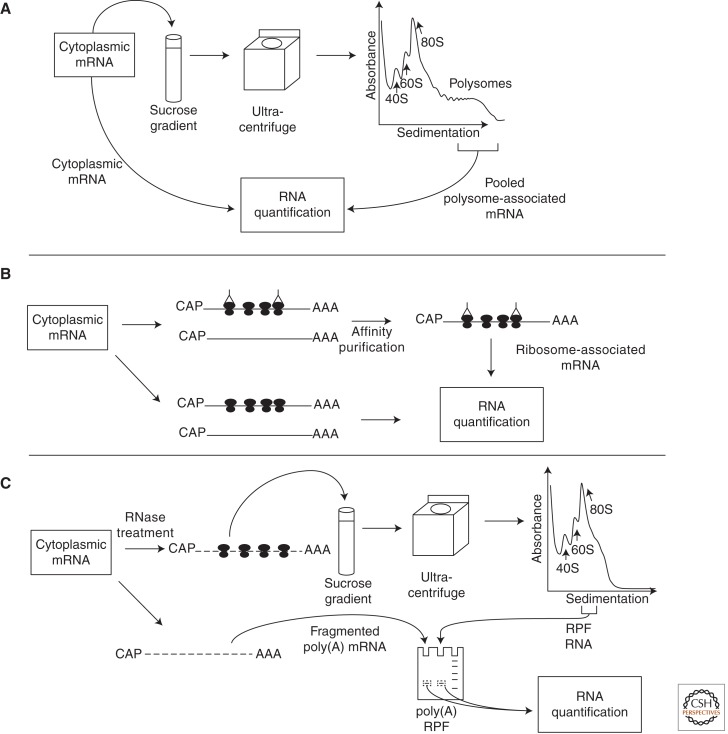

More direct evidence supporting the widespread role of translational control comes from studies of the global association between mRNAs and ribosomes. Because mRNAs that have a higher translational activity are associated with more ribosomes, the polysome microarray technique has been used to study genome-wide mRNA translation. For polysome preparation, translation elongation is inhibited by cycloheximide, the cytoplasmic lysate is isolated and applied to a sucrose gradient, and mRNAs associated with varying numbers of ribosomes are separated using ultracentrifugation according to their sedimentation velocity (Fig. 3A). Fractionated mRNAs are then extracted and subjected to DNA microarray analysis for identification and quantification. Although a large number of fractions can be obtained to examine mRNA profiles across the entire polysome range (Arava et al. 2003), most studies pool fractions because of the high cost of DNA microarrays (Johannes et al. 1999; Zong et al. 1999; Chen et al. 2002, 2011; Jechlinger et al. 2003; Preiss et al. 2003; Kitamura et al. 2004, 2008; Provenzani et al. 2006; Spence et al. 2006; Genolet et al. 2008; Parent and Beretta 2008; Ramirez-Valle et al. 2008; Ceppi et al. 2009; Dhamija et al. 2010; Rivera-Ruiz et al. 2010; Di Florio et al. 2011). Commonly, fractions with two or more associated ribosomes are pooled, limiting the analysis of regulation to a shift from less than two to two or more associated ribosomes (i.e., “on–off” regulation), whereas other shifts (e.g., from three to nine associated ribosomes, i.e., “relative” regulation) are missed. An alternative approach involves pooling mRNAs that are associated with >n ribosomes, where n is often 3 (Larsson et al. 2006, 2007; Mamane et al. 2007; Colina et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2009). This approach enables identification of differential translation involving both “on–off” and some “relative” regulation. Short mRNAs or mRNAs constantly associated with more than four ribosomes are, however, not studied. The polysome microarray technique has been applied to address a wide range of questions, including regulation of translation by the mTOR pathway (Rajasekhar et al. 2003; Tominaga et al. 2005; Larsson et al. 2006, 2007; Bilanges et al. 2007; Mamane et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2009; Furic et al. 2010), dynamic regulation of protein synthesis during cellular stress (Blais et al. 2004, 2006; Lu et al. 2006; Kumaraswamy et al. 2008; Dang Do et al. 2009; Matsuura et al. 2010), and the role of mRNA translation in development or differentiation (Iguchi et al. 2006; Grech et al. 2008; Parent and Beretta 2008; Sampath et al. 2008; Otulakowski et al. 2009) and disease (Larsson et al. 2008; Davidson et al. 2009; Treton et al. 2011).

Figure 3.

Techniques to obtain genome-wide data on mRNA translation. (A) The polysome technique. Polysome-associated mRNA is prepared in parallel with cytoplasmic mRNA and quantified using DNA microarrays or RNA-seq. (B) The affinity purification technique. mRNAs that are associated with tagged ribosomes are purified using an antibody-based affinity purification approach. Cytoplasmic mRNA is prepared in parallel, and both samples are quantified using DNA microarrays or RNA-seq. (C) The ribosome profiling technique. RPFs generated by RNase treatment are isolated from monosomes and subsequently purified by gel based on size. A randomly fragmented sample from poly(A) mRNA is prepared in parallel, and both samples are sequenced.

A second set of techniques relies on affinity purification of ribosomes, analogous to the RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP)–based techniques (Keene et al. 2006). These methods allow for identification and quantification of translating mRNAs (Fig. 3B). In one application, the ribosomal protein Rpl16 in yeast was modified by addition of a protein A tag to allow purification of mRNAs associated with ribosomes (Halbeisen et al. 2009). Similarly, a hemagglutinin (HA) tag was used to mark ribosomal protein Rpl22 in mouse (Sanz et al. 2009). Importantly, the HA tagging of Rpl22 was dependent on the activity of Cre recombinase, allowing analysis of mRNA translation in a selected cell type in vivo when combined with cell-type-specific Cre expression (Sanz et al. 2009). Another approach is based on the capture of Hsp70 chaperones associated with polysomes (Kudo et al. 2010). Theoretically, the efficiency of immunoprecipitation depends on the number of associated ribosomes, thereby reflecting translational activity. However, the precise number of ribosomes per mRNA is unknown.

A new technique named ribosome profiling has recently been developed (Ingolia et al. 2009), which is designed to identify open reading frames (ORFs) and quantitatively examine ribosome association with mRNAs. The technique involves two steps: isolation of mRNA fragments that are protected by ribosomes (ribosome-protected fragments [RPF]) from RNase treatment, and identification and quantification of the fragments by RNA-seq (Ingolia et al. 2009). For simplicity, this method is called RPF-seq here. Because RNA fragments are size-selected to obtain those corresponding to the expected footprint of the ribosome (Fig. 3C), RPF data reveal the locations of ribosomes on mRNA. As such, detailed quantitative examination of all steps of mRNA translation, including initiation, elongation, and termination, becomes possible. RPF-seq was first used to examine translational control in budding yeast under rich and starvation conditions (Ingolia et al. 2009). More recent studies using RPF-seq have assessed translation in several systems, including mouse embryonic stem cells (Ingolia et al. 2011), meiosis in yeast (Brar et al. 2012), and microRNA-mediated suppression of gene expression (Bazzini et al. 2012).

ANALYSIS OF mRNA TRANSLATION DATA

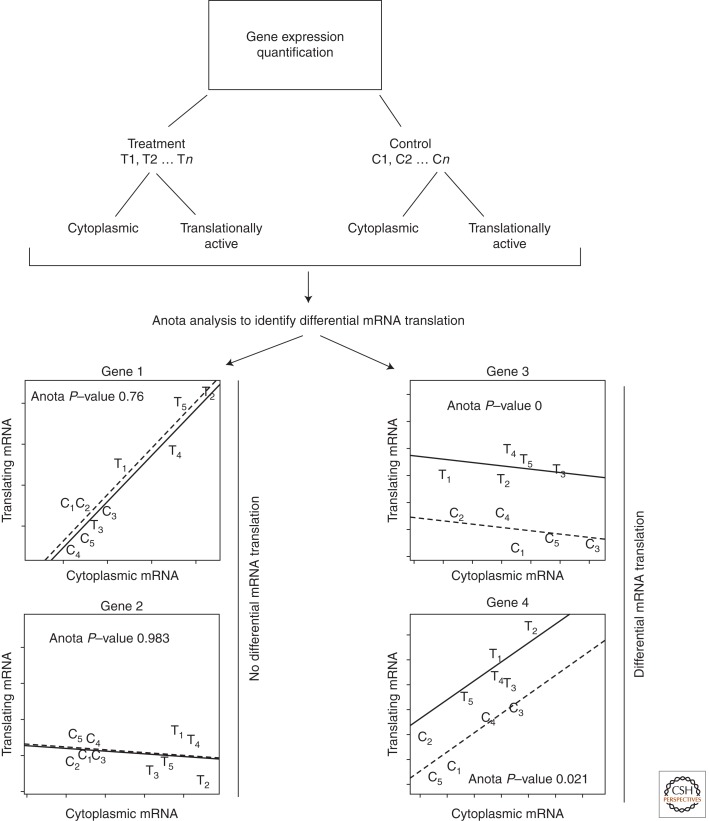

A major advantage in studying translating mRNA (the “translatome”) over steady-state mRNA (the “transcriptome”) is the ability to obtain measurements that more closely correspond to protein levels (Ingolia et al. 2009), owing to fewer intermediate regulatory steps. Accurate assessment of translational control, however, requires adjustment for the influence of other steps in the gene expression pathway, including transcription, mRNA stability, and mRNA transport (Larsson et al. 2010). Because individual mRNAs can be regulated substantially at the level of mRNA transport (Rousseau et al. 1996), only comparison to cytoplasmic mRNA levels will allow for the precise analysis of differential translation, whereas comparison to whole-cell mRNA will lead to joint analysis of mRNA transport and translation. A common approach to examine translational control is to calculate translational efficiency scores—log2 [(translating mRNA)/(cytoplasmic mRNA)]—and compare these between conditions to identify differential translation. Because of a mathematical necessity, translational efficiency scores may correlate with the cytoplasmic mRNA abundance instead of solely describing mRNA translation (Larsson et al. 2010). This phenomenon is called spurious correlation (Pearson 1896), which leads to increased false-positive and false-negative rates when examining differential translation (Larsson et al. 2010). Indeed, an assessment of 20 studies using the polysome microarray technique or RPF-seq showed that spurious correlations are common (Larsson et al. 2010). This shortcoming of using translational efficiency scores prompted development of a method based on analysis of partial variance (APV, implemented in the program Anota) (Larsson et al. 2010), which eliminates spurious correlations. In APV, a linear regression model (between translating and cytoplasmic mRNA data) is applied. Fold-change for mRNA translation and associated P-values are calculated based on differences in intercepts and residual errors (Fig. 4). In addition, the method includes a range of quality criteria to judge whether the input data set violates model assumptions (Larsson et al. 2011). Notably, this method has been successfully applied to identify differential mRNA translation using both polysome microarray and RPF-seq data (Larsson et al. 2010).

Figure 4.

Genome-wide identification of differential mRNA translation by Anota. Replicated data from translating and cytoplasmic mRNAs is used as input in Anota. Anota performs linear regression using translating and cytoplasmic mRNAs for all conditions. Treatment condition (solid line); control condition (dotted line). The intercepts of the lines on the y-axis are compared to derive an mRNA translation fold-change and are related to the residual error of the regression to identify differential translation. Genes 3 and 4 are differentially translated, but genes 1 and 2 are not. Simulated numbers are shown.

TECHNIQUES TO REVEAL CIS AND TRANS REGULATORS OF POSTTRANSCRIPTIONAL CONTROL

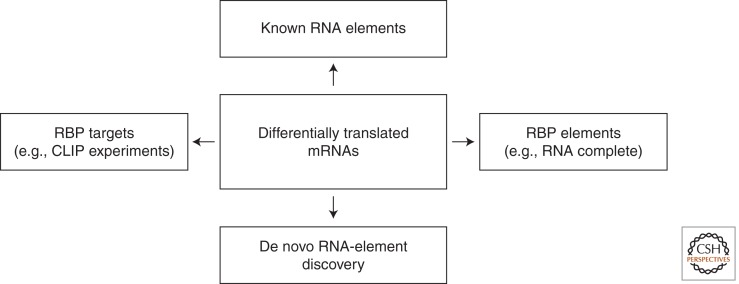

Posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression, including translation, is believed to involve sets of targeted mRNAs resembling the polycistronic operons present in bacteria (Spirin 1969; Keene and Tenenbaum 2002; Keene 2007). The theory posits that subsets of mRNAs can be regulated at the posttranscriptional level in a combinatorial fashion. Such selective regulation commonly involves RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) or microRNAs that associate with RNA elements within the target mRNA (Bartel 2004; Richter and Sonenberg 2005). RBP-associated mRNA elements are often defined by combinations of structure and sequence properties and usually reside in the mRNA UTR. Once associated with their target mRNA, the RBPs interact with translation initiation factors and sometimes other RBPs and/or microRNAs to positively or negatively regulate translation. Thus, active RNA elements and RBPs need to be identified to mechanistically reveal how differential translation takes place (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Approaches to examine mechanisms for differential mRNA translation.

Known RNA elements are often examined as the first step to explain differential translation. These are collected in general databases such as the UTRdb (Grillo et al. 2010), RBPDB (Cook et al. 2011), and CLIPZ (Khorshid et al. 2011) or element-specific databases such as the ARED (Halees et al. 2008) and IRESite (Mokrejs et al. 2010). Information regarding miRNA target sites can be obtained from many databases such as TargetScan (Lewis et al. 2005). Sometimes searching such databases leads to identification of active RNA elements as exemplified by identification of 5′-terminal oligopyrimidine tract (TOP) elements as targets of mTOR signaling (Bilanges et al. 2007; Mamane et al. 2007). More often, however, known RNA elements are not sufficient to explain observed mRNA translation patterns. This makes de novo discovery of regulatory RNA elements necessary.

Bioinformatic methods to uncover novel cis elements are based on the assumption that differentially translated mRNAs share common RNA elements (Larsson and Bitterman 2010). mRNA sequences, often in UTRs, are thus used as input to identify sequences or structures overrepresented in the regulated mRNAs, as compared with background ones (Larsson et al. 2006; Foat and Stormo 2009; Chen et al. 2011). A set of three algorithms detected ∼50% of known RNA elements when UTRs with specific RNA elements were mixed with randomly selected, unrelated UTR sequences (Fan et al. 2009), highlighting the potential of this approach. There are, nonetheless, several limitations. First, the precise length of each UTR is often unknown, and the active RNA elements may therefore be located outside of the studied sequences. In addition, alternative cleavage and polyadenylation, which regulates 3′-UTR length, is widespread and dynamically regulated under different conditions and across tissue types (Tian et al. 2005; Sandberg et al. 2008). Examining UTRs that are not expressed in the studied cell type can lead to false identification of RNA elements. Moreover, there is a possibility that some regulation involves several players, including RBPs, microRNAs, and RNA elements, with linear or nonlinear interactions. Such a complex situation likely makes identification of any single mechanism more difficult (Fan et al. 2009).

Several high-throughput techniques have been developed to study RNA–RBP interactions. In vitro methods include RNAcompete, whereby a library of RNAs is synthesized and used in pull-down experiments with RBPs followed by detection using DNA microarrays (Ray et al. 2009), and SELEX-seq, whereby random RNA aptamers are selected based on interaction with a specific RBP and are deep-sequenced (Dittmar et al. 2012). Although these methods do not directly address which mRNAs are targeted by the RBP under investigation, they elucidate binding specificities.

In vivo methods generally involve immunoprecipitation of RBPs from cells and identification of coimmunoprecipitated RNAs (Darnell and Richter 2012). Indeed, identification of RNA elements by ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation (RIP) followed by microarray (RIP-chip) has been successful for a number of RBPs (Gerber et al. 2004; Hogan et al. 2008). RBPs can also be UV-cross-linked to their binding RNAs in vivo, allowing purification of the RBP:RNA complex under denaturing conditions, for example, SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis). Deep sequencing of RNA isolated by cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP) has been used to study RBPs (Licatalosi et al. 2008; Darnell et al. 2011) and microRNAs (Chi et al. 2009). The photoactivatable-ribonucleoside-enhanced cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (PAR-CLIP) technique, which also has been used to study microRNAs and RBPs (Hafner et al. 2010; Hoell et al. 2011; Lebedeva et al. 2011; Mukherjee et al. 2011), is similar to HITS-CLIP but allows cross-linking at a longer wavelength. Both HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP allow precise detection of the binding site because cross-linking sites lead to mutations and deletions in sequencing reads (Hafner et al. 2010; Zhang and Darnell 2011). A comparison between HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP indicated that experimental conditions, such as the extent of RNase digestion, need to be optimized to minimize the sequence bias of the identified RNA fragments (Kishore et al. 2011). Another CLIP-based approach, iCLIP, identifies sequencing reads that terminate at the cross-linked sites (Wang et al. 2010; Konig et al. 2011; Tollervey et al. 2011). One potential caveat of all of these approaches is that binding of an RBP to mRNA may depend on other RBPs. Moreover, separating transient interactions with limited effect on regulation from stable interactions that substantially affect regulation is a challenge (Mukherjee et al. 2011). Nevertheless, systematic studies of many RBPs will likely soon be available and could be very useful to mechanistically dissect genome-wide patterns of differential mRNA translation.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Decades of research based on single genes have established that mRNA translation can profoundly control protein levels and thereby directly determine biological outcomes (Costa-Mattioli et al. 2009; Sonenberg and Hinnebusch 2009; Jackson et al. 2010; Silvera et al. 2010; Spriggs et al. 2010; Blagden and Willis 2011). Over the last few years, genome-wide analyses have shown that posttranscriptional regulation, translational control in particular, plays significant roles in determining protein levels in the cell. With the rapid development of current methodologies, especially deep-sequencing-based methods, we can expect many major discoveries to come from genome-wide studies. Integrating data on mRNA translation with information regarding RBP–mRNA interactions is an emerging area of research. In addition, given the widespread occurrence of mRNA isoforms in higher species, resulting from alternative initiation, splicing, and polyadenylation (Wang et al. 2008), sorting out the translational efficiency for each mRNA isoform will shed important light on the compendium of protein isoforms and reveal the connection between translational control and mRNA processing. On the other hand, to harness the power of genomics fully, we will need to better adopt high-throughput techniques and use rigorous data analysis approaches. It is exciting that a genome-wide landscape of translational control is now in sight.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

O.L. is supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Foundation, the Cancer Society in Stockholm, the Jeansson Foundation, and the Åke Wiberg Foundation. B.T. is supported by grants from the NIH. We thank Dr. Robert Nadon (McGill University) for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Editors: John W.B. Hershey, Nahum Sonenberg, and Michael B. Mathews

Additional Perspectives on Protein Synthesis and Translational Control available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Arava Y, Wang Y, Storey JD, Liu CL, Brown PO, Herschlag D 2003. Genome-wide analysis of mRNA translation profiles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 3889–3894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baerenfaller K, Grossmann J, Grobei MA, Hull R, Hirsch-Hoffmann M, Yalovsky S, Zimmermann P, Grossniklaus U, Gruissem W, Baginsky S 2008. Genome-scale proteomics reveals Arabidopsis thaliana gene models and proteome dynamics. Science 320: 938–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP 2004. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzini AA, Lee MT, Giraldez AJ 2012. Ribosome profiling shows that miR-430 reduces translation before causing mRNA decay in zebrafish. Science 336: 233–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer A, Hollunder J, Nasheuer HP, Wilhelm T 2004. Post-transcriptional expression regulation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae on a genomic scale. Mol Cell Proteomics 3: 1083–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilanges B, Argonza-Barrett R, Kolesnichenko M, Skinner C, Nair M, Chen M, Stokoe D 2007. Tuberous sclerosis complex proteins 1 and 2 control serum-dependent translation in a TOP-dependent and -independent manner. Mol Cell Biol 27: 5746–5764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagden SP, Willis AE 2011. The biological and therapeutic relevance of mRNA translation in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8: 280–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais JD, Filipenko V, Bi M, Harding HP, Ron D, Koumenis C, Wouters BG, Bell JC 2004. Activating transcription factor 4 is translationally regulated by hypoxic stress. Mol Cell Biol 24: 7469–7482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais JD, Addison CL, Edge R, Falls T, Zhao H, Wary K, Koumenis C, Harding HP, Ron D, Holcik M, et al. 2006. Perk-dependent translational regulation promotes tumor cell adaptation and angiogenesis in response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell Biol 26: 9517–9532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brar GA, Yassour M, Friedman N, Regev A, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS 2012. High-resolution view of the yeast meiotic program revealed by ribosome profiling. Science 335: 552–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceppi M, Clavarino G, Gatti E, Schmidt EK, de Gassart A, Blankenship D, Ogola G, Banchereau J, Chaussabel D, Pierre P 2009. Ribosomal protein mRNAs are translationally-regulated during human dendritic cells activation by LPS. Immunome Res 5: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Gharib TG, Huang CC, Taylor JM, Misek DE, Kardia SL, Giordano TJ, Iannettoni MD, Orringer MB, Hanash SM, et al. 2002. Discordant protein and mRNA expression in lung adenocarcinomas. Mol Cell Proteomics 1: 304–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Melton C, Suh N, Oh JS, Horner K, Xie F, Sette C, Blelloch R, Conti M 2011. Genome-wide analysis of translation reveals a critical role for deleted in azoospermia-like (Dazl) at the oocyte-to-zygote transition. Genes Dev 25: 755–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB 2009. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA–mRNA interaction maps. Nature 460: 479–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colina R, Costa-Mattioli M, Dowling RJ, Jaramillo M, Tai LH, Breitbach CJ, Martineau Y, Larsson O, Rong L, Svitkin YV, et al. 2008. Translational control of the innate immune response through IRF-7. Nature 452: 323–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook KB, Kazan H, Zuberi K, Morris Q, Hughes TR 2011. RBPDB: A database of RNA-binding specificities. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D301–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N 2009. Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron 61: 10–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang Do AN, Kimball SR, Cavener DR, Jefferson LS 2009. eIF2α kinases GCN2 and PERK modulate transcription and translation of distinct sets of mRNAs in mouse liver. Physiol Genomics 38: 328–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Darnell JC, Richter JD 2012. Cytoplasmic RNA binding proteins and the control of complex brain function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a012344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C, Hung KY, Mele A, Fraser CE, Stone EF, Chen C, Fak JJ, Chi SW, et al. 2011. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell 146: 247–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LA, Wang N, Ivanov I, Goldsby J, Lupton JR, Chapkin RS 2009. Identification of actively translated mRNA transcripts in a rat model of early-stage colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2: 984–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhamija S, Doerrie A, Winzen R, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Taghipour A, Kuehne N, Kracht M, Holtmann H 2010. IL-1-induced post-transcriptional mechanisms target overlapping translational silencing and destabilizing elements in IκBζ mRNA. J Biol Chem 285: 29165–29178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Florio A, Adesso L, Pedrotti S, Capurso G, Pilozzi E, Corbo V, Scarpa A, Geremia R, Delle Fave G, Sette C 2011. Src kinase activity coordinates cell adhesion and spreading with activation of mammalian target of rapamycin in pancreatic endocrine tumour cells. Endocr Relat Cancer 18: 541–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar KA, Jiang P, Park JW, Amirikian K, Wan J, Shen S, Xing Y, Carstens RP 2012. Genome-wide determination of a broad ESRP-regulated posttranscriptional network by high-throughput sequencing. Mol Cell Biol 32: 1468–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan D, Bitterman PB, Larsson O 2009. Regulatory element identification in subsets of transcripts: Comparison and integration of current computational methods. RNA 15: 1469–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foat BC, Stormo GD 2009. Discovering structural cis-regulatory elements by modeling the behaviors of mRNAs. Mol Syst Biol 5: 268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier ML, Paulson A, Pavelka N, Mosley AL, Gaudenz K, Bradford WD, Glynn E, Li H, Sardiu ME, Fleharty B, et al. 2010. Delayed correlation of mRNA and protein expression in rapamycin-treated cells and a role for Ggc1 in cellular sensitivity to rapamycin. Mol Cell Proteomics 9: 271–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furic L, Rong L, Larsson O, Koumakpayi IH, Yoshida K, Brueschke A, Petroulakis E, Robichaud N, Pollak M, Gaboury LA, et al. 2010. eIF4E phosphorylation promotes tumorigenesis and is associated with prostate cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 14134–14139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futcher B, Latter GI, Monardo P, McLaughlin CS, Garrels JI 1999. A sampling of the yeast proteome. Mol Cell Biol 19: 7357–7368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genolet R, Araud T, Maillard L, Jaquier-Gubler P, Curran J 2008. An approach to analyse the specific impact of rapamycin on mRNA–ribosome association. BMC Med Genomics 1: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber AP, Herschlag D, Brown PO 2004. Extensive association of functionally and cytotopically related mRNAs with Puf family RNA-binding proteins in yeast. PLoS Biol 2: e79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O’Shea EK, Weissman JS 2003. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature 425: 737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazalpour A, Bennett B, Petyuk VA, Orozco L, Hagopian R, Mungrue IN, Farber CR, Sinsheimer J, Kang HM, Furlotte N, et al. 2011. Comparative analysis of proteome and transcriptome variation in mouse. PLoS Genet 7: e1001393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grech G, Blazquez-Domingo M, Kolbus A, Bakker WJ, Mullner EW, Beug H, von Lindern M 2008. Igbp1 is part of a positive feedback loop in stem cell factor–dependent, selective mRNA translation initiation inhibiting erythroid differentiation. Blood 112: 2750–2760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin TJ, Gygi SP, Ideker T, Rist B, Eng J, Hood L, Aebersold R 2002. Complementary profiling of gene expression at the transcriptome and proteome levels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Proteomics 1: 323–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo G, Turi A, Licciulli F, Mignone F, Liuni S, Banfi S, Gennarino VA, Horner DS, Pavesi G, Picardi E, et al. 2010. UTRdb and UTRsite (RELEASE 2010): A collection of sequences and regulatory motifs of the untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 38: D75–D80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gry M, Rimini R, Stromberg S, Asplund A, Ponten F, Uhlen M, Nilsson P 2009. Correlations between RNA and protein expression profiles in 23 human cell lines. BMC Genomics 10: 365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gygi SP, Rochon Y, Franza BR, Aebersold R 1999. Correlation between protein and mRNA abundance in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 19: 1720–1730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M Jr, Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, et al. 2010. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 141: 129–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbeisen RE, Scherrer T, Gerber AP 2009. Affinity purification of ribosomes to access the translatome. Methods 48: 306–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halees AS, El-Badrawi R, Khabar KS 2008. ARED organism: Expansion of ARED reveals AU-rich element cluster variations between human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res 36: D137–D140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoell JI, Larsson E, Runge S, Nusbaum JD, Duggimpudi S, Farazi TA, Hafner M, Borkhardt A, Sander C, Tuschl T 2011. RNA targets of wild-type and mutant FET family proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 1428–1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DJ, Riordan DP, Gerber AP, Herschlag D, Brown PO 2008. Diverse RNA-binding proteins interact with functionally related sets of RNAs, suggesting an extensive regulatory system. PLoS Biol 6: e255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi N, Tobias JW, Hecht NB 2006. Expression profiling reveals meiotic male germ cell mRNAs that are translationally up- and down-regulated. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 7712–7717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JR, Weissman JS 2009. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science 324: 218–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS 2011. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell 147: 789–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV 2010. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 113–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayapal KP, Philp RJ, Kok YJ, Yap MG, Sherman DH, Griffin TJ, Hu WS 2008. Uncovering genes with divergent mRNA–protein dynamics in Streptomyces coelicolor. PLoS ONE 3: e2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jechlinger M, Grunert S, Tamir IH, Janda E, Ludemann S, Waerner T, Seither P, Weith A, Beug H, Kraut N 2003. Expression profiling of epithelial plasticity in tumor progression. Oncogene 22: 7155–7169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes G, Carter MS, Eisen MB, Brown PO, Sarnow P 1999. Identification of eukaryotic mRNAs that are translated at reduced cap binding complex eIF4F concentrations using a cDNA microarray. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 13118–13123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene JD 2007. RNA regulons: Coordination of post-transcriptional events. Nat Rev Genet 8: 533–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene JD, Tenenbaum SA 2002. Eukaryotic mRNPs may represent posttranscriptional operons. Mol Cell 9: 1161–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene JD, Komisarow JM, Friedersdorf MB 2006. RIP-Chip: The isolation and identification of mRNAs, microRNAs and protein components of ribonucleoprotein complexes from cell extracts. Nat Protoc 1: 302–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorshid M, Rodak C, Zavolan M 2011. CLIPZ: A database and analysis environment for experimentally determined binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D245–D252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YY, Von Weymarn L, Larsson O, Fan D, Underwood JM, Peterson MS, Hecht SS, Polunovsky VA, Bitterman PB 2009. Eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein family of proteins: Sentinels at a translational control checkpoint in lung tumor defense. Cancer Res 69: 8455–8462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore S, Jaskiewicz L, Burger L, Hausser J, Khorshid M, Zavolan M 2011. A quantitative analysis of CLIP methods for identifying binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nat Methods 8: 559–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura H, Nakagawa T, Takayama M, Kimura Y, Hijikata A, Ohara O 2004. Post-transcriptional effects of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate on transcriptome of U937 cells. FEBS Lett 578: 180–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura H, Ito M, Yuasa T, Kikuguchi C, Hijikata A, Takayama M, Kimura Y, Yokoyama R, Kaji T, Ohara O 2008. Genome-wide identification and characterization of transcripts translationally regulated by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in macrophage-like J774.1 cells. Physiol Genomics 33: 121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig J, Zarnack K, Rot G, Curk T, Kayikci M, Zupan B, Turner DJ, Luscombe NM, Ule J 2011. iCLIP reveals the function of hnRNP particles in splicing at individual nucleotide resolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 909–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo K, Xi Y, Wang Y, Song B, Chu E, Ju J, Russo JJ 2010. Translational control analysis by translationally active RNA capture/microarray analysis (TrIP–Chip). Nucleic Acids Res 38: e104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaraswamy S, Chinnaiyan P, Shankavaram UT, Lu X, Camphausen K, Tofilon PJ 2008. Radiation-induced gene translation profiles reveal tumor type and cancer-specific components. Cancer Res 68: 3819–3826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson O, Bitterman P 2010. Genome-wide analysis of translational control. In mTOR pathway and mTOR inhibitors in cancer therapy (cancer drug discovery and development) (ed. Polunovsky V, Houghton P), pp. 217–236 Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- Larsson O, Perlman DM, Fan D, Reilly CS, Peterson M, Dahlgren C, Liang Z, Li S, Polunovsky VA, Wahlestedt C, et al. 2006. Apoptosis resistance downstream of eIF4E: Posttranscriptional activation of an anti-apoptotic transcript carrying a consensus hairpin structure. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 4375–4386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson O, Li S, Issaenko OA, Avdulov S, Peterson M, Smith K, Bitterman PB, Polunovsky VA 2007. Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E induced progression of primary human mammary epithelial cells along the cancer pathway is associated with targeted translational deregulation of oncogenic drivers and inhibitors. Cancer Res 67: 6814–6824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson O, Diebold D, Fan D, Peterson M, Nho RS, Bitterman PB, Henke CA 2008. Fibrotic myofibroblasts manifest genome-wide derangements of translational control. PLoS ONE 3: e3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson O, Sonenberg N, Nadon R 2010. Identification of differential translation in genome wide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 21487–21492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson O, Sonenberg N, Nadon R 2011. Anota: Analysis of differential translation in genome-wide studies. Bioinformatics 27: 1440–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent JM, Vogel C, Kwon T, Craig SA, Boutz DR, Huse HK, Nozue K, Walia H, Whiteley M, Ronald PC, et al. 2010. Protein abundances are more conserved than mRNA abundances across diverse taxa. Proteomics 10: 4209–4212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedeva S, Jens M, Theil K, Schwanhausser B, Selbach M, Landthaler M, Rajewsky N 2011. Transcriptome-wide analysis of regulatory interactions of the RNA-binding protein HuR. Mol Cell 43: 340–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP 2005. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120: 15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licatalosi DD, Mele A, Fak JJ, Ule J, Kayikci M, Chi SW, Clark TA, Schweitzer AC, Blume JE, Wang X, et al. 2008. HITS-CLIP yields genome-wide insights into brain alternative RNA processing. Nature 456: 464–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, de la Pena L, Barker C, Camphausen K, Tofilon PJ 2006. Radiation-induced changes in gene expression involve recruitment of existing messenger RNAs to and away from polysomes. Cancer Res 66: 1052–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, Vogel C, Wang R, Yao X, Marcotte EM 2007. Absolute protein expression profiling estimates the relative contributions of transcriptional and translational regulation. Nat Biotechnol 25: 117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Markowetz F, Unwin RD, Leek JT, Airoldi EM, MacArthur BD, Lachmann A, Rozov R, Ma’ayan A, Boyer LA, et al. 2009. Systems-level dynamic analyses of fate change in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature 462: 358–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, Martineau Y, Sato TA, Larsson O, Rajasekhar VK, Sonenberg N 2007. Epigenetic activation of a subset of mRNAs by eIF4E explains its effects on cell proliferation. PLoS ONE 2: e242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura H, Ishibashi Y, Shinmyo A, Kanaya S, Kato K 2010. Genome-wide analyses of early translational responses to elevated temperature and high salinity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 448–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokrejs M, Masek T, Vopalensky V, Hlubucek P, Delbos P, Pospisek M 2010. IRESite—A tool for the examination of viral and cellular internal ribosome entry sites. Nucleic Acids Res 38: D131–D136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee N, Corcoran DL, Nusbaum JD, Reid DW, Georgiev S, Hafner M, Ascano M Jr, Tuschl T, Ohler U, Keene JD 2011. Integrative regulatory mapping indicates that the RNA-binding protein HuR couples pre-mRNA processing and mRNA stability. Mol Cell 43: 327–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie L, Wu G, Zhang W 2006. Correlation of mRNA expression and protein abundance affected by multiple sequence features related to translational efficiency in Desulfovibrio vulgaris: A quantitative analysis. Genetics 174: 2229–2243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otulakowski G, Duan W, O’Brodovich H 2009. Global and gene-specific translational regulation in rat lung development. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 40: 555–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent R, Beretta L 2008. Translational control plays a prominent role in the hepatocytic differentiation of HepaRG liver progenitor cells. Genome Biol 9: R19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson K 1896. On a form of spurious correlation which may arise when indices are used in the measurement of organs. Proc R Soc Lond 60: 489–498 [Google Scholar]

- Preiss T, Baron-Benhamou J, Ansorge W, Hentze MW 2003. Homodirectional changes in transcriptome composition and mRNA translation induced by rapamycin and heat shock. Nat Struct Biol 10: 1039–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzani A, Fronza R, Loreni F, Pascale A, Amadio M, Quattrone A 2006. Global alterations in mRNA polysomal recruitment in a cell model of colorectal cancer progression to metastasis. Carcinogenesis 27: 1323–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhar VK, Viale A, Socci ND, Wiedmann M, Hu X, Holland EC 2003. Oncogenic Ras and Akt signaling contribute to glioblastoma formation by differential recruitment of existing mRNAs to polysomes. Mol Cell 12: 889–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valle F, Braunstein S, Zavadil J, Formenti SC, Schneider RJ 2008. eIF4GI links nutrient sensing by mTOR to cell proliferation and inhibition of autophagy. J Cell Biol 181: 293–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray D, Kazan H, Chan ET, Castillo LP, Chaudhry S, Talukder S, Blencowe BJ, Morris Q, Hughes TR 2009. Rapid and systematic analysis of the RNA recognition specificities of RNA-binding proteins. Nat Biotechnol 27: 667–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JD, Sonenberg N 2005. Regulation of cap-dependent translation by eIF4E inhibitory proteins. Nature 433: 477–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Ruiz ME, Rodriguez-Quinones JF, Akamine P, Rodriguez-Medina JR 2010. Post-transcriptional regulation in the myo1Δ mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genomics 11: 690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau D, Kaspar R, Rosenwald I, Gehrke L, Sonenberg N 1996. Translation initiation of ornithine decarboxylase and nucleocytoplasmic transport of cyclin D1 mRNA are increased in cells overexpressing eukaryotic initiation factor 4E. Proc Natl Acad Sci 93: 1065–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath P, Pritchard DK, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Schwartz SM, Morris DR, Murry CE 2008. A hierarchical network controls protein translation during murine embryonic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 2: 448–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg R, Neilson JR, Sarma A, Sharp PA, Burge CB 2008. Proliferating cells express mRNAs with shortened 3′ untranslated regions and fewer microRNA target sites. Science 320: 1643–1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz E, Yang L, Su T, Morris DR, McKnight GS, Amieux PS 2009. Cell-type-specific isolation of ribosome-associated mRNA from complex tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 13939–13944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MW, Houseman A, Ivanov AR, Wolf DA 2007. Comparative proteomic and transcriptomic profiling of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Syst Biol 3: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimpf SP, Weiss M, Reiter L, Ahrens CH, Jovanovic M, Malmstrom J, Brunner E, Mohanty S, Lercher MJ, Hunziker PE, et al. 2009. Comparative functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster proteomes. PLoS Biol 7: e1000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanhausser B, Busse D, Li N, Dittmar G, Schuchhardt J, Wolf J, Chen W, Selbach M 2011. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473: 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvera D, Formenti SC, Schneider RJ 2010. Translational control in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 10: 254–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG 2009. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: Mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 136: 731–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence J, Duggan BM, Eckhardt C, McClelland M, Mercola D 2006. Messenger RNAs under differential translational control in Ki-ras-transformed cells. Mol Cancer Res 4: 47–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirin AS 1969. The second Sir Hans Krebs Lecture. Informosomes. Eur J Biochem 10: 20–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs KA, Bushell M, Willis AE 2010. Translational regulation of gene expression during conditions of cell stress. Mol Cell 40: 228–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi Y, Choi PJ, Li GW, Chen H, Babu M, Hearn J, Emili A, Xie XS 2010. Quantifying E. coli proteome and transcriptome with single-molecule sensitivity in single cells. Science 329: 533–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q, Stepaniants SB, Mao M, Weng L, Feetham MC, Doyle MJ, Yi EC, Dai H, Thorsson V, Eng J, et al. 2004. Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Proteomics 3: 960–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B, Hu J, Zhang H, Lutz CS 2005. A large-scale analysis of mRNA polyadenylation of human and mouse genes. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 201–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollervey JR, Curk T, Rogelj B, Briese M, Cereda M, Kayikci M, Konig J, Hortobagyi T, Nishimura AL, Zupunski V, et al. 2011. Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nat Neurosci 14: 452–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga Y, Tamguney T, Kolesnichenko M, Bilanges B, Stokoe D 2005. Translational deregulation in PDK-1−/− embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol 25: 8465–8475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treton X, Pedruzzi E, Cazals-Hatem D, Grodet A, Panis Y, Groyer A, Moreau R, Bouhnik Y, Daniel F, Ogier-Denis E 2011. Altered endoplasmic reticulum stress affects translation in inactive colon tissue from patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 141: 1024–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C, Abreu Rde S, Ko D, Le SY, Shapiro BA, Burns SC, Sandhu D, Boutz DR, Marcotte EM, Penalva LO 2010. Sequence signatures and mRNA concentration can explain two-thirds of protein abundance variation in a human cell line. Mol Syst Biol 6: 400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB 2008. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456: 470–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Kayikci M, Briese M, Zarnack K, Luscombe NM, Rot G, Zupan B, Curk T, Ule J 2010. iCLIP predicts the dual splicing effects of TIA–RNA interactions. PLoS Biol 8: e1000530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn MP, Koller A, Oshiro G, Ulaszek RR, Plouffe D, Deciu C, Winzeler E, Yates JR III 2003. Protein pathway and complex clustering of correlated mRNA and protein expression analyses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 3107–3112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Darnell RB 2011. Mapping in vivo protein–RNA interactions at single-nucleotide resolution from HITS-CLIP data. Nat Biotechnol 29: 607–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong Q, Schummer M, Hood L, Morris DR 1999. Messenger RNA translation state: The second dimension of high-throughput expression screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 10632–10636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]