Abstract

Background and Aims

There is a great need to search for natural compounds with superior prebiotic, antioxidant and immunostimulatory properties for use in (food) applications. Raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) show such properties. Moreover, they contribute to stress tolerance in plants, acting as putative membrane stabilizers, antioxidants and signalling agents.

Methods

A large-scale soluble carbohydrate screening was performed within the plant kingdom. An unknown compound accumulated to a high extent in early-spring red deadnettle (Lamium purpureum) but not in other RFO plants. The compound was purified and its structure was unravelled with NMR. Organs and organ parts of red deadnettle were carefully dissected and analysed for soluble sugars. Phloem sap content was analysed by a common EDTA-based method.

Key Results

Early-spring red deadnettle stems and roots accumulate high concentrations of the reducing trisaccharide manninotriose (Galα1,6Galα1,6Glc), a derivative of the non-reducing RFO stachyose (Galα1,6Galα1,6Glcα1,2βFru). Detailed soluble carbohydrate analyses on dissected stem and leaf sections, together with phloem sap analyses, strongly suggest that stachyose is the main transport compound, but extensive hydrolysis of stachyose to manninotriose seems to occur along the transport path. Based on the specificities of the observed carbohydrate dynamics, the putative physiological roles of manninotriose in red deadnettle are discussed.

Conclusions

It is demonstrated for the first time that manninotriose is a novel and important player in the RFO metabolism of red dead deadnettle. It is proposed that manninotriose represents a temporary storage carbohydrate in early-spring deadnettle, at the same time perhaps functioning as a membrane protector and/or as an antioxidant in the vicinity of membranes, as recently suggested for other RFOs and fructans. This novel finding urges further research on this peculiar carbohydrate on a broader array of RFO accumulators.

Keywords: Lamium purpureum, manninotriose, raffinose, RFO, red deadnettle, stachyose

INTRODUCTION

Sucrose (Suc; Glcα1,2βFru) is one of the most widespread disaccharides in nature (Salerno and Curatti, 2003) and is especially ubiquitous in higher plants as the first free sugar resulting from photosynthesis (Koch, 2004). In most plants it is the major transport compound to bring carbon skeletons from source (photosynthesizing leaves) to sink tissues (roots, young leaves, flowers, seeds, etc) (Etxeberria et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012). Together with Suc, the raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) raffinose (Raf; Galα1,6Glcα1,2βFru) and stachyose (Sta; Galα1,6Galα1,6Glcα1,2βFru), both α-galactosyl (Gal) extensions of Suc, are important transport compounds in the orders Lamiales, Cucurbitales, Cornales and in one family of the Celastrales (Zimmermann and Ziegler, 1975; Haritatos et al., 1996; Hoffmann-Thoma et al., 1996; Turgeon et al., 2001). Raf (Fig. 1A) is ubiquitous in plants, while Sta (Fig. 1B) and higher degree of polymerization (DP) RFOs (verbascose, ajugose, etc.) only accumulate in some plant species (Bachmann et al., 1994; Keller and Pharr, 1996). The metabolism of RFOs has been thoroughly studied in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Iftime et al., 2011, and references therein) and in Ajuga reptans, a member of the Lamiaceae (Peters and Keller, 2009) as well as in an array of different legume seeds (Blöchl et al., 2008). Besides their function as a reserve compound, RFO accumulation seems to be intimately connected to stress responses (Taji et al., 2002; Vanhaecke et al., 2008; Iftime et al., 2011; Bento dos Santos et al., 2011). In particular, much attention is paid to cold responses, stimulating RFO gene expression, enzyme activity and RFO accumulation (Peters and Keller, 2009; Korn et al., 2010; Mollo et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). Like other oligosaccharides, such as fructans (Amiard et al., 2003; Livingston et al., 2009), RFOs might stabilize membranes and/or act as antioxidants to counteract the accumulation of reactive oxygen species under stress (Nishizawa et al., 2008; Van den Ende and Valluru, 2009; Bolouri-Moghaddam et al., 2010; Stoyanova et al., 2011; Van den Ende et al., 2011a). Furthermore, galactinol (Gol) and Raf were considered as signals during biotic stress (Kim et al., 2008). Galactosides might also be involved in the establishment of symbiotic associations (Bringhurst et al., 2001). It is a matter of speculation whether Raf might also function as a signal under abiotic stress (Valluru and Van den Ende, 2011).

Fig. 1.

Structures of RFOs in L. purpureum. (A) Raffinose (Raf) is an α(1 → 6) elongation of sucrose (Suc). Raf might be subjected to β-fructosidase activity leading to the production of fructose and melibiose (Mel). Alternatively, the action of α-galactosidase leads to the formation of galactose (Gal) and Suc B. Stachyose (Sta) is an α(1 → 6) elongation of Raf. Sta might be subjected to β-fructosidase activity leading to the production of fructose and manninotriose (Min). Alternatively, the action of α-galactosidase leads to the formation of galactose (Gal) and Raf.

The synthesis of Raf occurs in two steps: (1) Gol is produced from UDPGal and myoinositol by Gol synthase (GolS); (2) the Gal moiety is transferred from Gol to Suc by the enzyme Raf synthase. Both enzymes reside in the cytosol (Schneider and Keller, 2009). In A. reptans, a member of the Lamiaceae typically accumulating RFOs (Janecek et al., 2011), the higher DP RFOs are produced in the vacuole by a galactan:galactan galactosyl transferase (Haab and Keller, 2002). Intriguingly, Caryophyllaceae such as Stellaria media do not accumulate Sta, but alternative RFOs instead (Vanhaecke et al., 2008, 2010).

Removal of the fructosyl unit of Raf (Fig. 1A) and Sta (Fig. 1B) leads to the formation of melibiose (Mel; Galα1,6Glc) and manninotriose (Min; Galα1,6Galα1,6Glc), respectively. Not much is known on the occurrence of these reducing sugars in plant tissues that also accumulate Raf and Sta. Min was reported to occur at lower levels in Alisma orientalis (Alismataceae) (Zhang et al., 2009). The Min : Sta ratio drastically increased during post-harvest processing of the roots of Rhemannia glutinosa (Phrymaceae), a typical Sta accumulator. Interestingly, this treatment greatly increased the pharmacological activities of the derived extracts, suggesting that Min could be responsible for these activities (Kubo et al., 1996). Min is also detectable in commercial soybean oligosaccharide syrups (Takano et al., 1991). Furthermore, Min derivatives have been reported to show strong antibacterial activities (Chiba et al., 2007).

The winter to summer annual red deadnettle (Lamium purpureum, Lamiaceae) is a widely distributed plant, a common weed and a host of potato virus Y on cultivated lands (Kaliciak and Syller, 2009; Mock et al., 2010). It is also known as a medicinal plant (Akkol et al., 2008; Barros et al., 2010). To the best of our knowledge, sugars have never been thoroughly investigated in this species. Here, we report that Min accumulates to a great extent in early-spring stems and roots of red deadnettle, even becoming the most prominent water-soluble carbohydrate. Our data suggest that Sta is the main transport compound in red deadnettle, as described for other species within the Lamiaceae family (Bachmann et al., 1994; Turgeon et al., 2001).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Materials for large screening of sugar compounds in the stems of RFO-accumulating plants were harvested in the Leuven area. All Lamium purpureum plants needed for the experiments were harvested in the Leuven area during the period February–July 2011. Different plant segments were carefully dissected (see Fig. 4) and the samples were used for carbohydrate analyses or for phloem-sap analysis. For purification of Min (NMR characterization) early spring-derived stems originating from at least 30 individual plants were collected and combined.

Fig. 4.

Lamium purpureum pictures representing the dissections of (A) the eight different parts of the stem (stem 0 representing the internode between the bottom leaf and the leaf above) as well as top and bottom leaves, and (B) the four different parts of the major vein dissected from the bottom leaf.

Carbohydrate quantification

To extract soluble carbohydrates, plant material (±100 mg) was ground with pestle and mortar in 1 mL of 80 % ethanol and heated to 80 °C in an open tube for 30 min. The remaining ethanol was evaporated with a vacuum concentrator (SpeedVac). Finally, milli Q-water was added corresponding to 10 volumes of the original sample and heated for 10 min at 99 °C. After cooling at room temperature, the extract was centrifuged at 16 000 g for 5 min and 200 µL of the supernatant was loaded on a column with two ion exchange resins (200 µL Dowex®–50 H+ and 200 µL Dowex®–1-acetate) and washed six times with 200 µL of milliQ-water. Finally, 25 µL of the neutralized fraction was analysed by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA; Shiomi et al., 1991) to determine the sugar content after separation on a CarboPac® PA100 anion exchange column with pulsed amperometric detection and equipped with a gold electrode (potentials: E1, + 0·05 V; E2, +0·6 V; E3, –0·8 V). The flow rate was 1 mL min−1. The column was equilibrated with 90 mm NaOH for 9 min before injection. The sugars were eluted with a Na-acetate gradient: 0–10 mm from 0 min to 6 min; 10–100 mm from 6 min to 16 min. Finally, the column was regenerated with 500 mm Na-acetate for 5 min. Quantification was performed on the peak areas (Van den Ende et al., 1996) with the external standards methods for Glc, Fru, Mel, Min, Suc, Raf and Sta.

Enzymatic degradation

Raf, Sta and Min were subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis. Wheat vacuolar invertase and green coffee bean α-galactosidase were used as described before (Vanhaecke et al., 2010).

Phloem exudation tests

Plants were held in two solutions: one with 5 mm Tris buffer pH 8·0 with 5 mm EDTA and the other without 5 mm EDTA. Care was taken, that both conditions were performed on opposite leaves from the same plant. Plant segments containing leaves were put in a Petri dish in the appropriate solution and, after thorough washing, the leaves were cut at the petiole level with a sharp razor blade and transferred to Eppendorfs containing 1 mL of either 5 mm Tris buffer 8·0 + EDTA or 5 mm Tris buffer pH 8·0 without EDTA, respectively. During this washing and transfer process, cut surfaces remained in solution. After 10 min, 2 h and 24 h, phloem exudates (200 µL) were collected and the volume was re-adjusted to 1 mL. After heating for 5 min at 90 °C, sugars were analysed with HPAEC-PAD as described above. Plant segments and sugar-exporting leaves were held under continuous light (25 µE) at 20 °C. Total leaf extracts (see Carbohydrate quantification) were prepared as controls.

Manninotriose isolation for NMR

For Min isolation, early-spring-derived stem material (50 g) from L. purpureum was first heated in 50 mL 80 % ethanol at 80 °C for 20 min. Later 50 mL milli-Q water was added and then the tissue was homogenized for 2 min in a blender. The homogenate was then boiled in a water bath for 10 min. After cooling, the extract was squeezed through cheesecloth, followed by centrifugation (5 min at 40 695 g) and mixed-bed ion exchange chromatography (50 mL Dowex®-1-acetate and 50 mL Dowex®-50 H+, both 100–200 mesh). The neutral fraction was concentrated to 15 mL with a Rotavap and applied to a Ca-Dowex column (40 cm × 5 cm) as described by Timmermans et al. (2001). Fractions were analysed by HPAEC-PAD (Vergauwen et al., 2000). The fractions containing Min were pooled and concentrated to 3 mL. Of this concentrate, 300 µL was further separated with a semi-preparative CarboPac PA100 column (22 × 250 mm) as described (Vanhaecke et al., 2006). The fractions were neutralized with HCl and were further analysed by HPAEC-PAD. The pure Min fractions were pooled and loaded onto an activated charcoal column (8 × 2·5 cm) to eliminate the NaOH. After washing with 200 mL water and 20 mL 5 % ethanol, the column was eluted with 25 % ethanol. Fractions containing Min were pooled and dried in a Rotavap to a few millilitres (10 mg) and were finally freeze dried.

NMR analysis

The Min sample (5 mg) was deuterium exchanged by lyophilising three times from 99·6 % D2O and then dissolved in 0·6 mL 99·6 % D2O. Spectra were recorded at 22 °C on a Bruker Avance II 600 equipped with a 5-mm TCI HCN Z gradient cryoprobe. The Bruker Topspin 2·1 software was used to process all spectra. The 2D pulse programs of 1H–1H COSY, HSQC, HMBC and NOESY experiments were as described before (Vanhaecke et al., 2008). As earlier, the 2D HSQC–TOCSY consisted of an HSQC building block (D1 = D2 = 1·67 ms) followed by a clean MLEV17 TOCSY transfer step during a mixing time of 60 ms prior to detection (Vanhaecke et al., 2008).

RESULTS

Variation in carbohydrate profiles among different parts of Lamium purpureum

A large-scale sugar analysis with HPAEC-PAD on >100 different plant species was undertaken to detect novel or unexpected carbohydrate compounds. Next to the unexpected discovery of levan- and graminan-type fructans in Pachysandra terminalis (Van den Ende et al., 2011b), this screening led to the detection of a very prominent peak in early-spring plants of L. purpureum, also accumulating substantial levels of Raf and, especially, Sta. Although this peak was absent in other tested RFO accumulators (Fig. 2), we speculated that it could be related to the RFO metabolism in this species. The collected peak appeared insensitive to acid invertase but sensitive to α-galactosidase (Table 1). Moreover, the same compound could be obtained after treating Sta with acid invertase (not shown). Therefore, it was concluded that the peak represented Min, a derivative of Sta lacking a terminal Fru (Fig. 1B). Final confirmation came from NMR studies (see below). It was considered that Min could arise from the partial hydrolysis of Sta to Min and Fru during the sugar-extraction procedure. As described before (Vergauwen et al., 2000; Le Roy et al., 2007), it was found that a hot ethanol-extraction method was highly effective to inhibit the activity of hydrolytic enzymes during the extraction, while a slight hydrolysis of Sta was observed when using a hot water extraction procedure (not shown). The reliability of the hot ethanol-extraction method was further confirmed by the observation that L. purpureum was the only RFO accumulator with a high Min : Sta ratio (Fig. 2). Since the increased Min levels in this species were not associated with increased fructose levels (Fig. 2), it was concluded that (a) Min accumulation is unique in L. purpureum and (b) Min is not generated during extraction.

Fig. 2.

HPAEC-PAD chromatograms of stem parts derived from Lamium purpureum, Leonurus cardiaca, Physostegia virginiana, Cornus mas, Melissa officinalis, Ajuga reptans and Lamiastrum galeobdolon as compared with a reference mixture containing 150 µm of galactinol (Gol), 150 µm of glucose (Glc), 150 µm of fructose (Fru), 150 µm of melibiose (Mel), 150 µm of manninotriose (Min), 150 µm sucrose (Suc), 150 µm of raffinose (Raf) and 150 µm of stachyose (Sta). Galactose (Gal) was not included in the reference.

Table 1.

Susceptibility of raffinose (Raf), stachyose (Sta) and manninotriose (Min) to enzymatic degradation by α-galactosidase and invertase

| α-Galactosidase | Invertase | |

|---|---|---|

| Raf | + | + |

| Sta | + | + |

| Min | + | – |

Although Min was detected in all parts of early-spring deadnettle plants (roots, stems, leaves, flowers and flower buds; Fig. 3), it accumulated to a much higher extent in stems and roots, together with Sta (Fig. 3). The concentrations of Min, Sta and Mel were much lower in flowers and flower buds, where Glc + Gal and Fru are the major sugars. Leaves contain Sta as their major sugar with high Sta : Min ratios (see below), next to some Raf which is also present in stems and (to a lower extent) in roots. Suc is present in surprisingly low concentrations in all plant parts (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

HPAEC-PAD chromatograms of different parts of L. purpureum, compared with a reference mixture containing 10 µm of mannitol (Mtl), 10 µm of glucose (Glc), 10 µm of fructose (Fru), 10 µm of melibiose (Mel), 10 µm of manninotriose (Min), 10 µm of sucrose (Suc), 10 µm of raffinose (Raf) and 10 µm of stachyose (Sta). Galactose (Gal) was not included in the reference.

Quantification of soluble carbohydrates in different stem segments of Lamium purpureum

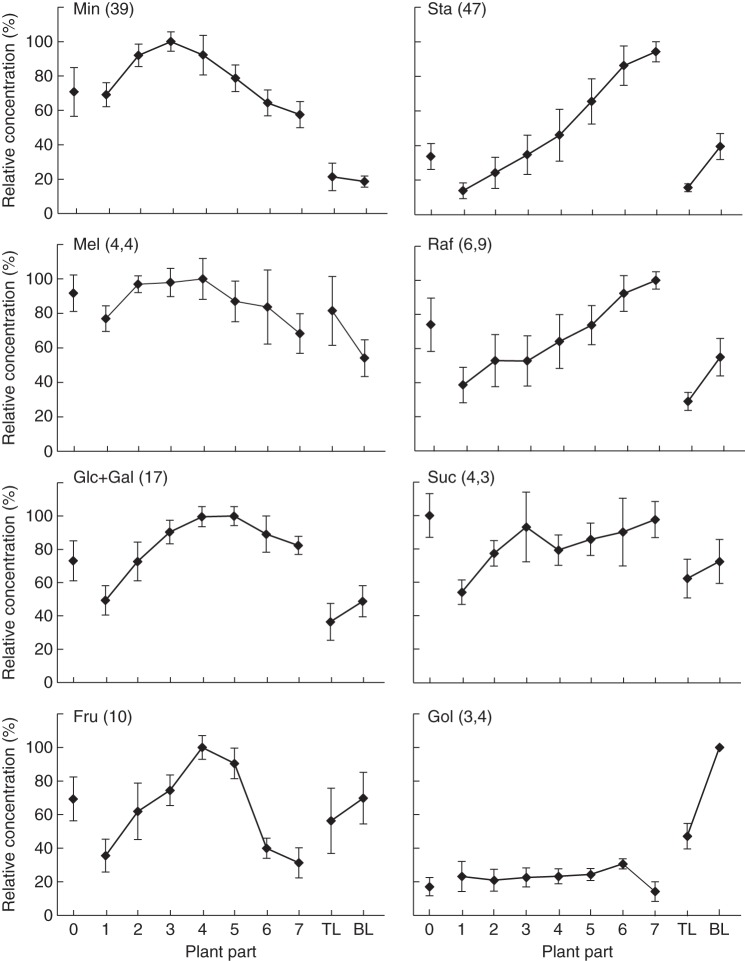

In further analyses, besides the top and bottom leaves, stems were divided into eight segments (stems 0–7) as presented in Fig. 4A. The concentrations of both Min and Mel were higher in the middle part of the stem, decreasing again to the bottom of the stem (Fig. 5). A partially opposite profile was observed for Sta with increasing concentrations in the bottom part of the stem, suggesting that Min may be considered as a breakdown product of Sta. Mel and Raf present similar profiles as Min and Sta, respectively, but less pronounced (Fig. 5). Similar to Min and Mel, Fru is also present in higher concentrations in the middle part of the stem. Glc + Gal levels are higher in the middle and lower stem parts. Suc profiles were rather variable (Fig. 5). The same analyses were performed on top and bottom leaves. Gol was low and constant in the stem segments but clearly present in both leaves (Fig. 5). The Raf, Sta and Gol concentrations were higher in the bottom leaf than in the top leaf, while the differences were insignificant for the other sugars (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Carbohydrate gradients in different parts of L. purpureum stems and in top leaves (TL) and bottom leaves (BL) as illustrated in Fig. 4A. Relative values are presented and the maximal concentration of each sugar is indicated in μg f. wt−1. Min, Manninotrios; Sta, stachyose; Mel, melibiose; Raf, raffinose; Glc/Gal, glucose/galactose; Suc, sucrose; Fru, fructose; Gol, galactinol. Standard errors are presented for n = 5.

Quantification of soluble carbohydrates in different leaf segments of Lamium purpureum

A further analysis of the inter-vein area and carefully dissected vein parts collected on 10 May (veins 1–4; Fig. 4B) showed clearly higher Suc concentrations towards the distal part of the leaf (vein 1 at the leaf tip, Fig. 6), with strongly increasing Min and Raf towards the proximal part of the leaf (vein 4, the petiole). Importantly, Min and Mel could not be detected in the inter-vein area consisting of mesophyll and small veins, while Sta, Raf and Fru were found in small quantities and Suc and Gol were the main carbohydrates (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

HPAEC-PAD chromatograms of the different vein parts 1–4 (as defined in Fig. 4B) and inter-vein area as compared with a reference mixture containing 10 µm of galactinol (Gol), 10 µm of mannitol (Mtl), 10 µm of glucose (Glc), 10 µm of fructose (Fru), 10 µm of melibiose (Mel), 10 µm of manninotriose (Min), 10 µm of sucrose (Suc), 10 µm of raffinose (Raf) and 10 µm of stachyose (Sta). Galactose (Gal) was not included in the reference.

Sta and Raf are the main transport sugars in Lamium purpureum

A thorough analysis of leaf exudates and total leaf extracts in the presence and absence of EDTA showed a clear mobility for Raf and Sta, since these sugars are present at relatively higher concentrations in leaf exudates with EDTA compared with total leaf extracts with and without EDTA (Fig. 7). As a control for non-phloem-associated sugar leakage, leaf exudates from opposite leaves without EDTA showed only trace amounts of sugars, suggesting that Suc, Glc + Gal and Fru might have a very limited phloem mobility as well. On the contrary, the reducing oligosaccharides Min and Mel show the lowest mobility in leaf veins (Fig. 7). Leaf EDTA treatment led to increasing Mel, Min, Gal + Glu and Suc concentrations at the expense of Raf and Sta (Fig. 7), suggesting that EDTA might stimulate some of the endogenous RFO breakdown activities.

Fig. 7.

HPAEC-PAD chromatograms of leaves treated with and without EDTA and their respective exudates, as compared with a reference mixture containing 30 µm of galactinol (Gol), 30 µm of mannitol (Mtl), 30 µm of glucose (Glc), 30 µm of fructose (Fru), 30 µm of melibiose (Mel), 30 µm of manninotriose (Min), 30 µm of sucrose (Suc), 30 µm of raffinose (Raf) and 30 µm of stachyose (Sta). Galactose (Gal) was not included in the reference. Tris, Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane.

NMR characterization of Min

Min was purified from early-spring stems of red deadnettle and its structure was fully confirmed by NMR spectroscopy (Supplementary Data Figs S1 and S2). Starting from the characteristic anomeric centres, assignment in the six-membered rings of both Gals and Glc was achieved using two-dimensional (2-D) techniques (chemical shifts reported in Supplementary Data Tables S1 and S2). The linkages between monosaccharides were determined from cross peaks that arise in the HMBC spectrum due to long-range coupling (3JCH) over the glycosidic bonds. The chair conformation of the six-membered rings was derived from three bond coupling constants listed in Table S3 and confirmed with the observed contacts in the NOESY spectrum. The 3JHH in the sugar between H-1 and H-2 and chemical shifts of C-1 and H-1 are consistent with an α-anomeric configuration of both Gals. In the aqueous condition of our NMR sample, glucose existed for about 30 % in its α-anomeric configuration and 70 % in its β-anomeric configuration based on the 3JHH in the sugar between H-1 and H-2 and chemical shifts of C-1 and H-1 (Supplementary Data Tables S1–S3).

DISCUSSION

There is a great need to search for natural compounds with superior prebiotic, antioxidant and immunostimulatory properties for use in food applications (Van den Ende et al., 2011a). On the one hand, raffinose and galacto-oligosaccharides from non-plant origin are known as health stimulating compounds (Shoaf et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2010), although excess levels in RFO-containing seeds cause intestinal discomfort (Tahir et al., 2012). On the other hand, RFOs are emerging as crucial molecules during stress responses in plants, possibly because of their membrane-stabilizing, antioxidant and, perhaps, signalling functions (Hincha et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2008; Nishizawa et al., 2008; Valluru and Van den Ende, 2011). Taken together, these are strong arguments to focus efforts on novel RFO compounds in plants (Vanhaecke et al., 2010).

While screening a large array of plant species, a closer inspection among the RFO accumulators (Fig. 2) revealed that early-spring red deadnettle stems contained an extra peak next to Raf and Sta. Purification and NMR analysis (Supplementary Data Figs S1 and S2 and Tables S1–S3) identified this compound as Min, a trisaccharide resembling Sta but lacking Fru (Fig. 1B). As a typical member of the Lamiaceae, it was within our expectations that red deadnettle RFO metabolism would resemble the one observed in common bugle (A. reptans), another well-studied representative within the family. Common bugle is known to contain two RFO pools in its leaves: a storage pool associated with leaf mesophyll and a transport pool associated with the phloem-loading sites (Bachmann et al., 1994; Bachmann and Keller, 1995) where Raf and especially Sta are produced and loaded in the phloem, according to the polymer trapping model. These two pools rely on different GolS forms (Sprenger and Keller, 2000). Careful dissection of the leaf inter-vein area, containing both mesophyll and minor veins, revealed the presence of Raf, Sta and Suc (Fig. 6), confirming RFO synthesis from Suc at the phloem-loading sites. The RFOs in this area seem not to be subject to hydrolysis by putative β-fructosidase activity, since no Mel and Min were detected in this tissue. On the contrary, our dissections on the main vein showed increasing levels of Mel and Min towards the proximal part, while Suc levels showed the opposite trend (Fig. 6), next to the expected presence of Raf and Sta as transport compounds (Fig. 7). These observations argue for a continuous leakage of Sta (as well as Raf and some Suc) along the major vein (van Bel et al., 2011) and subsequent processing of Sta to Min, Raf to Mel and Suc to Hex by putative β-fructosidase(s) operating in the neighbouring cell layer(s) of the main vein. According to recent findings (Zhang et al., 2012), retrieval into the phloem of the reducing sugars produced in these reactions (such as Mel, Min and Hex) seems very unlikely. Indeed, phloem sap typically harbours non-reducing sugars (Zhang et al., 2012). Moreover, it was experimentally confirmed that Mel cannot be loaded in phloem vessels (Trip et al., 1965). It seems reasonable to assume that the same holds for Min. Our experiments (Fig. 7) demonstrated that Sta is the major transport compound, as observed in other RFO accumulators (Bachmann et al., 1994; Keller and Pharr, 1996). Raf and Sta are not synthesized in sink tissues of Coleus blumei, another member of the Lamiaceae (Madore, 1990). Accordingly, only low levels of Gol could be detected in red deadnettle stems (Fig. 5), indicating that sink RFOs were imported through the phloem.

Compared with source leaves, the concentrations of Min are much more extended in some sink tissues (such as roots and stems), suggesting that these tissues also harbour β-fructosidase forms to remove Fru from Raf and Sta but lack α-galactosidases for further processing of Min and Mel into Gal and Glc. This way of thinking fits well with the observation that Min, Mel and Fru show similar patterns along the different parts of the stems, while Raf and Sta show rather opposite patterns (Figs 4 and 5). It can be assumed that young sink leaves and flowers (top of the plant in Fig. 4A) are much stronger sinks compared with lateral stems branching from the main stem with more limited growth (bottom of the plant in Fig. 4B). In this view, it was not surprising to find the lowest levels of RFOs in flowers (Fig. 3) and in the upper parts of the stems (Fig. 5). Indeed, strong growth requires more Hex formation and utilization through respiration. Apparently Raf and Sta were more preserved in the lower parts of the stem as compared with the middle parts (Fig. 5) again suggesting a differential degradation (see above). Overall, Min might represent a temporal storage in early-spring deadnettle stems (e.g. comparable with fructans in cereal stems; Van den Ende et al., 2003; Livingston et al., 2009). At the same time it might act as an antioxidant in the vicinity of membranes as it is the case for other RFOs (Nishizawa et al., 2008; Knaupp et al., 2011) and for other (oligo)saccharides such as fructans (Van den Ende and Valluru, 2009; Bolouri-Moghaddam et al., 2010; Stoyanova et al., 2011). Alternatively, RFOs were proposed as membrane protectors contributing to cold tolerance (Iftime et al., 2011). However, introducing the ability to synthesize Sta in arabidopsis leaves did not lead to an increased cold tolerance (Iftime et al., 2011). It was suggested that the cytosolic Sta is not at the correct location (presumably the chloroplast) to provide protection. Intriguingly, recent evidence was generated for the presence of a Raf transporter in the chloroplastic envelope (Schneider and Keller, 2009). Import of Raf in the chloroplasts could help to protect the photosynthetic apparatus (Knaupp et al., 2011). It can be speculated that arabidopsis lacks a Sta transporter in the chloroplastic envelope (Iftime et al., 2011).

Future work will attempt to extend the studies on L. purpureum to the enzymes involved in RFO degradation in the different parts dissected. However, this will be challenging because of the limited amount of material available for enzyme activity measurements and the very low levels of proteins present, as became apparent during preliminary investigations. Furthermore, these novel findings urge further research on Min within a broader array of RFO accumulators.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by funds from ‘FWO Vlaanderen’.

LITERATURE CITED

- Akkol EK, Yalcin FN, Kaya D, Calis I, Yesilada E, Ersoz T. In vivo anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive actions of some Lamium species. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;118:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiard V, Morvan-Bertrand A, Billard JP, Huault C, Keller F, Prud'homme MP. Fructans, but not the sucrosyl-galactosides, raffinose and loliose, are affected by drought stress in perennial ryegrass. Plant Physiology. 2003;132:2218–2229. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.022335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann M, Keller F. Metabolism of the raffinose family oligosaccharides in leaves of Ajuga reptans L.: intercellular and intracellular compartmentation. Plant Physiology. 1995;109:991–998. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.3.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann M, Matile P, Keller F. Metabolism of the raffinose family oligosaccharides in leaves of Ajuga reptans L. cold acclimation, translocation and sink to source transition: discovery of chain elongation enzyme. Plant Physiology. 1994;105:1335–1345. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.4.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros L, Heleno SA, Carvalho AM, Ferreira I. Lamiaceae often used in Portuguese folk medicine as a source of powerful antioxidants: vitamins and phenolics. LWT – Food Science and Technology. 2010;43:544–550. [Google Scholar]

- van Bel AJE, Furch ACU, Hafke JB, Knoblauch M, Patrick JW. Questions on phloem biology. 2. Mass flow, molecular hopping, distribution patterns and macromolecular signalling. Plant Science. 2011;181:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bento dos Santos T, Budzinski IGF, Marur CJ, Petkowicz CLO, Pereira LFP, Vieira LGE. Expression of three galactinol synthase isoforms in Coffea arabica L. and accumulation of raffinose and stachyose in response to abiotic stresses. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2011;49:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blöchl A, Peterbauer T, Hofmann J, Richter A. Enzymatic breakdown of raffinose oligosaccharides in pea seeds. Planta. 2008;228:99–110. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0722-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolouri-Moghaddam MR, Le Roy K, Xiang L, Rolland F, Van den Ende W. Sugar signalling and antioxidant network connections in plant cells. FEBS Journal. 2010;277:2022–2037. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringhurst RM, Cardon ZG, Gage DJ. Galactosides in the rhizosphere: utilization by Sinorhizobium meliloti and development of a biosensor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2001;98:4540–4545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071375898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T, Takii T, Nishimura K, et al. Synthesis of new sugar derivatives from Stachys sieboldi Miq and antibacterial evaluation against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium, and Staphylococcus aureus. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2007;17:2487–2491. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etxeberria E, Pozueta-Romero J, Gonzalez P. In and out of the plant storage vacuole. Plant Science. 2012;190:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haab CI, Keller F. Purification and characterization of the raffinose oligosaccharide chain elongation enzyme, galactan: galactan galactosyltransferase (GGT), from Ajuga reptans leaves. Physiologia Plantarum. 2002;114:361–371. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1140305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haritatos E, Keller F, Turgeon R. Raffinose oligosaccharide concentrations measured in individual cells and tissue types in Cucumis melo L. leaves: implications for phloem loading. Planta. 1996;198:614–622. doi: 10.1007/BF00262649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hincha DK, Zuther E, Heyer AG. The preservation of liposomes by raffinose family oligosaccharides during drying is mediated by effects on fusion and lipid phase transitions. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta – Biomembranes. 2003;1612:172–177. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann-Thoma G, van Bel AJE, Ehlers K. Ultrastructure of minor-vein phloem and assimilate transport in summer and winter leaves of the symplasmically loading evergreens Ajuga reptans L., Aucuba japonica Thunb., and Hedera helix L. Planta. 1996;212:231–242. doi: 10.1007/s004250000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iftime D, Hannah MA, Peterbauer T, Heyer AG. Stachyose in the cytosol does not influence freezing tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis expressing stachyose synthase from adzuki bean. Plant Science. 2011;180:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janecek S, Lanta V, Klimesova J, Dolezal J. Effect of abandonment and plant classification on carbohydrate reserves of meadow plants. Plant Biology. 2011;13:243–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2010.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaliciak A, Syller J. New hosts of Potato virus Y (PVY) among common wild plants in Europe. European Journal of Plant Pathology. 2009;124:707–713. [Google Scholar]

- Keller F, Pharr DM. Photoassimilate distribution in plants and crops: source–sink relationships. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1996. Metabolism of carbohydrates in sinks and sources: galactosyl-sucrose oligosaccharides In: Zamski E, Schaffer AA; pp. 157–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Cho SM, Kang EY, et al. Galactinol is a signaling component of the induced systemic resistance caused by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6 root colonization. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 2008;21:1643–1653. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-12-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaupp M, Mishra KB, Nedbal L, Heyer AG. Evidence for a role of raffinose in stabilizing photosystem II during freeze–thaw cycles. Planta. 2011;234:477–486. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch K. Sucrose metabolism: regulatory mechanisms and pivotal roles in sugar sensing and plant development. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2004;7:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn M, Gartner T, Erban A, Kopka J, Selbig J, Hincha DK. Predicting Arabidopsis freezing tolerance and heterosis in freezing tolerance from metabolite composition. Molecular Plant. 2010;3:224–235. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M, Asano T, Matsuda H, Yutani S, Honda S. Studies on Rehmanniae radix. 3 The relation between changes of constituents and improvable effects on hemorheology with the processing of roots of Rehmannia glutinosa. Yakugaku Zasshi – Journal of the Pharmaceutical Society of Japan. 1996;116:158–168. doi: 10.1248/yakushi1947.116.2_158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roy K, Vergauwen R, Cammaer V, et al. Fructan 1-exohydrolase is associated with flower opening in Campanula rapunculoides. Functional Plant Biology. 2007;34:972–983. doi: 10.1071/FP07125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DD, Chao WM, Turgeon R. Transport of sucrose, not hexose, in the phloem. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2012;63:4315–4320. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston DP, Hincha DK, Heyer AG. Fructan and its relationship to abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2009;66:2007–2023. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0002-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madore MA. Carbohydrate metabolism in photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic tissues of variegated leaves of Coleus blumei Benth. Plant Physiology. 1990;93:617–622. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.2.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock VA, Creech JE, Ferris VR, Hallett SG, Johnson WG. Influence of winter annual weed removal timings on soybean cyst nematode population density and plant biomass. Weed Science. 2010;58:381–386. [Google Scholar]

- Mollo L, Martins MCM, Oliveira VF, Nievola CC, Figueiredo-Ribeiro RdCL. Effects of low temperature on growth and non-structural carbohydrates of the imperial bromeliad Alcantarea imperialis cultured in vitro. Plant Cell Tissue and Organ Culture. 2011;107:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa A, Yabuta Y, Shigeoka S. Galactinol and raffinose constitute a novel function to protect plants from oxidative damage. Plant Physiology. 2008;147:1251–1263. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.122465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters S, Keller F. Frost tolerance in excised leaves of the common bugle (Ajuga reptans L.) correlates positively with the concentrations of raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) Plant, Cell & Environment. 2009;32:1099–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno GL, Curatti L. Origin of sucrose metabolism in higher plants: when, how and why? Trends in Plant Science. 2003;8:63–69. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Keller F. Raffinose in chloroplasts is synthesized in the cytosol and transported across the chloroplast envelope. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2009;50:2174–2182. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi N, Onodera S, Chatterton NJ, Harrison PA. Separation of fructooligosaccharide isomers by anion-exchange chromatography. Agricultural Biology and Chemistry. 1991;55:1427–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Shoaf K, Mulvey GL, Armstrong GD, Hutkins RW. Prebiotic galactooligosaccharides reduce adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to tissue culture cells. Infection and Immunity. 2006;74:6920–6928. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01030-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger N, Keller F. Allocation of raffinose family oligosaccharides to transport and storage pools in Ajuga reptans: the roles of two distinct galactinol synthases. The Plant Journal. 2000;21:249–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanova S, Geuns J, Hideg E, Van den Ende W. The food additives inulin and stevioside counteract oxidative stress. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 2011;62:207–214. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2010.523416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir M, Baga M, Vandenberg A, Chibbar RN. An assessment of raffinose family oligosaccharides and sucrose concentration in genus Lens. Crop Science. 2012;52:1713–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Taji T, Ohsumi C, Iuchi S, et al. Important roles of drought- and cold-inducible genes for galactinol synthase in stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 2002;29:417–426. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7412.2001.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano Y, Furihata K, Yamazaki S, Okubo A, Toda S. Identification and composition of low-molecular-weight carbohydrates in commercial soybean oligosaccharide syrup. Journal of the Japanese Society for Food Science and Technology – Nippon Shokuhin Kagaku Kogaku Kaishi. 1991;38:681–683. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans JW, Slaghek TM, Iizuka M, Van den Ende W, De Roover J, Van Laere A. Isolation and structural analysis of new fructans produced by chicory. Journal of Carbohydrate Chemistry. 2001;20:375–395. [Google Scholar]

- Trip P, Nelson CD, Krotkov G. Selective and preferential translocation of C14-labeled sugars in white ash and lilac. Plant Physiology. 1965;40:740. doi: 10.1104/pp.40.4.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon R, Medville R, Nixon KC. The evolution of minor vein phloem and phloem loading. American Journal of Botany. 2001;88:1331–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valluru R, Van den Ende W. Myo-inositol and beyond: emerging networks under stress. Plant Science. 2011;181:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Valluru R. Sucrose, sucrosyl oligosaccharides, and oxidative stress: scavenging and salvaging? Journal of Experimental Botany. 2009;60:9–18. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Mintiens A, Speleers H, Onuoha A, Van Laere A. The metabolism of fructans in roots of Cichorium intybus L. during growth, storage and forcing. New Phytologist. 1996;132:555–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1996.tb01874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Clerens S, Vergauwen R, et al. Fructan 1-exohydrolases. beta-(2,1)-trimmers during graminan biosynthesis in stems of wheat? Purification, characterization, mass mapping, and cloning of two fructan 1-exohydrolase isoforms. Plant Physiology. 2003;131:621–631. doi: 10.1104/pp.015305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Peshev D, De Gara L. Disease prevention by natural antioxidants and prebiotics acting as ROS scavengers in the gastrointestinal tract. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2011a;22:689–697. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Ende W, Coopman M, Clerens S, et al. Unexpected presence of graminan- and levan-type fructans in the evergreen frost-hardy eudicot Pachysandra terminalis (Buxaceae): purification, cloning, and functional analysis of a 6-SST/6-SFT enzyme. Plant Physiology. 2011b;155:603–614. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.162222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaecke M, Van den Ende W, Van Laere A, Herdewijn P, Lescrinier E. Complete NMR characterization of lychnose from Stellaria media (L.) Vill. Carbohydrate Research. 2006;341:2744–2750. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaecke M, Van den Ende W, Lescrinier E, Dyubankova N. Isolation and characterization of a pentasaccharide from Stellaria media. Journal of Natural Products. 2008;71:1833–1836. doi: 10.1021/np800274k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaecke M, Dyubankova N, Lescrinier E, Van den Ende W. Metabolism of galactosyl-oligosaccharides in Stellaria media: discovery of stellariose synthase, a novel type of galactosyltransferase. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1095–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergauwen R, Van den Ende W, Van Laere A. The role of fructan in flowering of Campanula rapunculoides. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2000;51:1261–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XB, Zhao Y, He NW, Croft KD. Isolation, characterization, and immunological effects of alpha-galacto-oligosaccharides from a new source, the herb Lycopus lucidus Turcz. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58:8253–8258. doi: 10.1021/jf101217f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CK, Yu XY, Ayre BG, Turgeon R. The origin and composition of cucurbit ‘phloem’ exudate. Plant Physiology. 2012;158:1873–1882. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.194431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LL, Zhao MG, Tian QY, Zhang WH. Comparative studies on tolerance of Medicago truncatula and Medicago falcata to freezing. Planta. 2011;234:445–457. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Wang D, Zhao Y, Gao H, Hu YH, Hu JF. Fructose-derived carbohydrates from Alisma orientalis. Natural Product Research. 2009;23:1013–1020. doi: 10.1080/14786410802391120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann MH, Ziegler H. List of sugars and sugar alcohols in sieve-tube exudates. In: Zimmermann MH, Milburn JA, editors. Transport in plants. 1. Phloem transport. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Springer; 1975. pp. 480–503. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology, New Series. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.